Archive for the 'Readers’ Favorite Entries' Category

Molly wanted more

The Crime of M. Lange.

DB here:

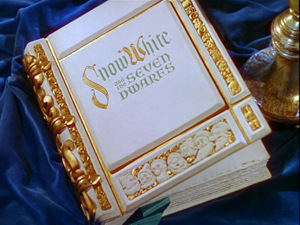

I was watching Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs some years ago with a friend’s three-year-old daughter. Molly hadn’t seen the movie before, and she watched it in a fascinated silence. At the end, Snow White and the prince leave the dwarfs and ride off into the distance.

At this point Molly cried, “More!”

This surprised me. How could she know, on her first pass, that the story was ending?

In and out

It has no name that I’m aware of, but it’s one of the most common conventions of movie storytelling. At the end of the film, the story world closes itself off from us. The characters turn away, perhaps walking into the distance. We may get a distant long shot of the scene. In some cases the camera accentuates this withdrawal by craning or tracking away from the action.

At the end of The Wild One, the biker hero smiles at the woman he’s met and goes out into the street. After exchanging a glance with the ineffectual sheriff, he swings his motorcycle around, his back to us. Cut to an extreme long shot as he rides off.

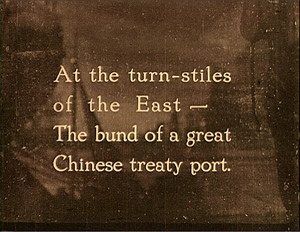

Once you notice this sort of ending, you’re likely to think about beginnings. Sure enough, we find some symmetry. A movie often visually brings us into the story world. Most common is an inward progression, moving from a large view to the central space of action. As far back as 1919, Griffith started Broken Blossoms with an overall view of the harbor and an explanatory title.

Then we have a gradual entry into the Chinese neighborhood, moving steadily from long shots to closer views. The young ladies we encounter aren’t major characters in the plot, but we’re still slowly drawn into the story world.

At the film’s end, Griffith’s cutting will manage a parallel withdrawal, from the lovers to the temple and back to the waterfront view.

In fact, Snow White starts with a comparable, if somewhat smoother shift inward, from the exterior of the Queen’s castle then, via camera movement and dissolves, to the Queen at her mirror.

This last shot reminds us that alternatively, a film can start with the characters coming forward, as if to meet us. This is the way The Wild One begins.

Any sort of combination is possible. The Silence of the Lambs starts with Clarice Starling climbing up a hill toward us and pausing long enough for us to register her as a protagonist.

She then turns and runs off into the forest. If this were an ending, we might see her go off further and further into the distance. But this is an opening, so we follow her with a tracking shot forward, letting her lead us into the story action. Soon we’re back to the frontality and intimacy of an opening passage, like the shot of the Queen.

At the end, Jonathan Demme gives us a pair of “farewell” shots. The first occurs when Clarice, who’s been talking to Dr. Lecter on the phone, hears the line go dead. We pull away from her.

The second farewell shot takes place on Lecter’s end in a Caribbean island. It shows him rising to follow Chilson and walking away from us, to be swallowed up into the crowd.

The Silence of the Lambs takes leave of its protagonists in two alternative ways: If the camera doesn’t move away from our characters, it seems, then the characters move away from the camera. They may even seal themselves off, as when a flight attendant pinches shut the curtain at the end of The Hunt for Red October.

So when we speak of films’ “openings” or “closings,” it seems that we are often talking about a world that initially invites us in but will finally expell us, however slowly and politely.

See it here!

Researchers play Jeopardy! Their answers always take the form of a question. Most film critics work in the declarative mode (“The performances are gripping”), but ideally the academic film researcher works in the interrogative mode. What is this pattern of beginnings and endings doing in movies? How does it work? How did it become common? And how do we learn it?

Take the first question, about the purposes and functions of the device. At one level its neat symmetry mimics the sort of frame that we find in other sorts of narrative, particularly oral storytelling. Fictional stories need to be set off from the surrounding flow of discourse. When we hear “Once upon a time,” we all know a fairy tale is starting. There are equivalents in other oral traditions, as in “Here is a tale . . . .” (Yoruba) and “See it here!” (Hause).

Likewise, oral storytelling traditions use formulaic final lines. In our fairy tales, it’s often “And they lived happily ever after.” Native American folk tales may finish with the storyteller simply saying, “The end” or “Tied up.” African oral epics sometimes use the formula “That is what I know” or “Let us leave the words right here.”

In fact, I cheated a little with my examples from Snow White. The film actually is bracketed by a literal opening and closing.

In film, however, the symmetrical structure is only part of the answer. While a film can copy the literary idea of opening and closing a written text, the medium as a whole offers something more. Thanks to the visual nature of movies, the widening or closing-off of the story world can mimic the act of our entering or backing out of a tangible situation. That’s what we see in Snow White and my other examples. In a sense we greet the characters, and after spending some time with them we bid them farewell. The sense of entering and leaving their world is harder to capture so concretely in literature or theatre.

So we need a more specific account of the convention. Surely you’ve thought about the most obvious candidate. The entry/ leave-taking pattern mimics our activities as perceiving, socially inclined people. For creatures like us, to encounter a new situation or setting simply involves approaching it or letting it approach us, then becoming part of it and fixing our attention on its details. At a party, we amble closer to a knot of people we want to talk with, or someone comes up to us. Sooner or later that encounter ends or trails off, and we withdraw or turn away or watch when others depart. More poignantly, the extreme long-shot option can recall moments when a car or bus or train carried us away from our loved ones. In any case, thanks to moving images the salient features of this very common experience can be made tangible for viewers.

This convention, we might say, is just natural. Molly, who had already logged three years of social experience, could plausibly make the analogy with ease. She recognized that her encounter with the world of Snow White was coming to an end–the characters were leaving her–and could express her regret.

This common-sense answer is, I think, basically right. But it needs to be fortified against some objections.

For one thing, not all films use this convention. Lots of films start with close-ups of particular items in an environment, plunging us into details without a gradual entry (below, Back to the Future; Muriel; ou le temps d’un retour).

And lots of films don’t end with marks of withdrawal or closure. They end on close views, often of the characters or a significant object (below, Le Silence de la mer; Sorry, Wrong Number).

If this pattern were biased by our natural proclivities, wouldn’t it be more common than it is? And if it comes so naturally, why wasn’t it present at the start of cinema, as soon as people started telling stories? Most of the storytelling techniques we now consider very user-friendly, like cutting and camera movement, emerged after many years of moviemaking. It’s akin to a problem in the history of painting: Why did painters need centuries to learn to imitate the way things look?

Moreover, the naturalness can look pretty unnatural. Nobody lies down in the middle of the road to let a horde of bikers sweep by, as in the beginning of The Wild One. The high angle at the end of the movie doesn’t imitate anybody’s likely point of view; it mimics, if anything, a godlike perspective we almost never get. Similarly, the cuts and dissolves that link the views in Broken Blossoms and Snow White don’t have any parallel in our real experience. Tied to our bodies, we can only move toward or away from situations in real time, step by step. The time-compression and freedom of position we get on film are far from natural. In sum, the concrete ways in which this immersion/ withdrawal pattern shows up in actual movies suggest that the films aren’t imitating the literal vantage points we might assume in the real world. There is a lot of contrivance going on.

Real life, amped up

So the convention has some roots in our perceptual and social experience, but filmmakers have streamlined and sharpened it for our uptake. Another example of this process, which I discuss here, involves actors’ eye behavior. Film actors start with normal patterns of looking and blinking, but they modify them in order to signal emotional states and to concentrate our attention on the drama. Similarly, the schema of entering/ leaving a milieu derives from our common experience, but it can be simplified and stylized through cinematic techniques that have no correspondence in our normal experience. All that matters is that the result preserves the core of that schema.

As filmmakers simplify our perceptual and social experiences, they amplify them as well. Movie characters stare at each other more intently than we do in normal life. The actors are stripping off everyday noise (blinks, averted looks) in order to create cleaner, exaggerated signals of mutual attention to the dramatic situation. Likewise, a steep high angle like that ending The Wild One or the pointedly closed curtains of The Hunt for Red October exaggerates the sense of departure and conclusion, giving the action a weight it wouldn’t have in ordinary life.

Why don’t all films use the entry/ retreat convention? I think we should consider such conventions to be tools. They arise in particular filmmaking traditions, perhaps through trial and error, and get refined for different purposes. Some filmmakers might never use them, or knowingly refuse them to create different reactions, or play games with them (as Resnais does at the start of Muriel). But when filmmakers want certain effects, these tools are ready to hand. If you want to ease your audience into the story world, a slow entry pattern works very well. It’s so familiar that the viewer can overlook its contrivance and concentrate on the story information.

So Jeopardy!-style, we have new questions. Has the opening/ closing device spread because it is a very accessible, spontaneously understood convention? Or is it because filmmakers in other cultures have mechanically copied Hollywood? Perhaps it’s like a tool that originates in particular cultural circumstances but which can be useful all over the world. The Phillips-head screw was devised for the US automotive industry but is now a universal gadget. Over time, such tools become more widespread, perhaps dominant. But a tool can always be refused if the task changes.

There’s still a mystery, though. Assuming that viewers understand these image-clusters as signaling beginnings and endings, how did that understanding come about? How, and when, do people learn the conventions? If they are quickly learned, is that because they play into inclinations of our minds?

My best guess for now is this. We tend to think that all artistic conventions are equally hard to learn, but that’s probably not the case. The conventions of Cubist painting demand more effort and knowledge than the conventions of perspective drawing, and that’s probably not just because we’ve seen more perspective pictures across our lives. Likewise, mastering the conventions of Structural Film demands more time and trouble than mastering those of popular genre filmmaking. It seems likely that some conventions rise to dominance because they fit most viewers’ prior inclinations rather well. For example, we are creatures who interact socially in face-to-face manner. Shot/ reverse-shot editing is unfaithful to our ordinary experience in many ways; cuts provide instant changes of viewpoint we can’t achieve in real time and space. But shot/ reverse-shot cutting preserves the familiar social pattern of turn-taking and conversational flow, so it’s comparatively easy to learn.

Still, I don’t have a full answer. My questions bring us back to Molly. If she had seen Snow White before, we might say that she remembered that the film ended at this point. But she hadn’t seen the film before. So does her demand for more indicate that she generalized from her experience of other films? Did she have already a degree of “narrative competence,” allowing her to recognize certain types of cues? Is her competence full or spotty? (Maybe she gets endings, but not characters’ intentions, or goal orientation.) And how did she acquire that competence? Quickly or slowly?

Maybe some researchers have already explored how children master narrative framing of this sort. (I’d welcome correspondence on the matter.) My hunch is that Molly grasped the cinematic convention, perhaps on limited exposure, because she recognized the core perceptual and social experiences it preserves. Leveraging this insight, perhaps, was some understanding of narrative architecture generally. More basically, it may be that as social animals we’re tuned by evolution to detect fairly quickly some constant features of interactions with our peers.

In any case, I’m betting that Molly wasn’t simply mastering a convention cut off from everyday life, like algebraic equations. To learn anything, you already need to know a lot. Cinematic storytelling isn’t, as some semiologists once thought, a highly arbitrary sign system. It piggybacks on our experience of the world–our knowledge, certainly, but also our most routine ways of sensing and thinking. Not least, understanding movies taps skills associated with our social intelligence. More on this in a future entry, I hope.

This is only an anecdote, but I hope it provokes readers to think about the broader issues I raise. I floated these ideas in my closing address for the convention of the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image, on 5 June 2010. I thank the members of the audience for their contributions to that discussion. Incidentally, this year’s meeting is coming up, in Budapest this June. For more on SCSMI and the sort of issues broached in this entry, go to this category on this site.

My basic argument for a “moderate constructivism” in understanding film conventions is developed in the 1996 essay “Convention, Construction, and Cinematic Vision,” reprinted in Poetics of Cinema (2008), 57-82. I discuss the entry/ withdrawal pattern as a holistic strategy in a later essay in that collection, “Three Dimensions of Film Narrative”, 94-95. An earlier, more fancily titled piece puts the pattern in the context of a different argument: “Neo-Structuralist Narratology and the Functions of Filmic Storytelling” in Marie-Laure Ryan, ed., Narrative across Media: The Languages of Storytelling (2004), 209.

It’s worth mentioning that, like Snow White, the images at the start and conclusion of Le Silence de la mer are enframed by a book–in this case, shots of the original book by Vercors. This iconography is of course common when a film wants to emphasize the literary origins, though in some films, like Dreyer’s, the device of the film as a replay of an already-written text plays a more complicated narrative role. I talk about that in my book The Films of Carl Theodor Dreyer (1981).

The research on children’s understanding of stories is vast and detailed. Alison Gopnik briskly summarizes the evidence that even very young children have surprising narrative competence in The Philosophical Baby (2009), chapters 1 and 2. The pioneering source here, at least for an amateur like me, was Katherine Nelson, ed., Narratives from the Crib (1989).

The Bad Lieutenant: Port of Call New Orleans. As in many films, the final shot addresses the viewer in a comparatively overt way.

Endurance: Survival lessons from Lumet

I don’t believe in waiting for the masterpiece. Masterful subject matter comes up only rarely. The point is, there’s something to advance your technique in every movie you do.

DB here:

Across half a century he outpaced his contemporaries. He was the last survivor of the vaunted 1950s generation of East-Coast TV-trained directors, men who went over to theatrical films just as the studio system was in decline. John Frankenheimer, Martin Ritt, Richard Lester, and Franklin J. Schaffner won big projects early on, but they also faded faster. As they were moving out of the game in the 1970s and 1980s, Lumet was getting his second wind. He ground movies out–good, so-so, or wretched–like a contract director of the studio days. Sometimes he had a strong stretch, as in the early 1980s, and sometimes not. He started in his early thirties with Jean Vigo’s cameraman Boris Kaufman, shooting crystalline black and white. At the end he was making a feature in high-definition video.

When Lumet died on 9 April, journalists were generous in their praise. But most of the eulogies seemed to me constraining. They overlooked his complicated role in postwar American film, and they neglected to supply the sort of historical context that make even his negligible films of interest. Concentrating on his official masterpieces (Dog Day Afternoon, Network), the obituaries cast him as a hard-nosed urban realist. That’s part of the story, but if we want a fuller picture of this long-distance runner, we need to trace his path in more detail. That in turn can teach us something about shifting generational opportunities in American cinema.

We can start by noting what the recent accolades seem to have forgotten: at the start of his career Lumet faced brutal hostility from the critical intelligentsia that ruled his home town.

Danger man

The Pawnbroker.

Reading 1960s film criticism, you might think that Sidney Lumet was the biggest threat to film art since the Hays Code. Young cinephiles today may be unaware of the vituperation that New York’s highbrow critics showered on him at the start of his career.

John Simon: “What is Lumet good at? Intentions, underlining, and casting.”

Manny Farber: “Giganticism is, of course, the main Lumet contribution [to The Group]. . . . Miss [Shirley] Knight, in a concentrated post-coitus scene atop [Hal] Holbrook’s chest, has a head the size of a watermelon.”

Andrew Sarris: “The Pawnbroker is a pretentious parable that manages to shrivel into drivel.”

Most tireless was Pauline Kael, who throughout the decades picked off nearly every Lumet movie with the casual contempt of Annie Oakley shooting skeet. From the backhanded compliment (“The Pawnbroker is a terrible movie and yet I’m glad I saw it”) to the eviscerating dismissal (Deathtrap is “an ugly play and what appears to be a vile vision of life”), Kael did not relent. She found Lumet’s staging “slovenly,” his color schemes inept; in Serpico “scene after ragged scene cried out for retakes.”

The hunt was in full cry in Kael’s 1968 essay, “The Making of The Group,” one of those behind-the-scenes journalistic forays that always end in tears for the production. Every such think-piece mysteriously assures the film’s commercial failure, while guaranteeing that posterity will remember each participant as a knave or a fool. Yet for sheer bloodthirstiness, Kael’s reportage easily surpasses that of her predecessor Lillian Ross in Picture.

Kael is out to show that the conditions of acquiring, producing, and marketing films have become almost utterly corrupt. No artist can survive the system. So she starts by establishing Lumet as merely a journeyman, shooting the script as a straightforward job of work.

But then things get rough. He is, for one thing, a poor craftsman.

He cannot use crowds or details to convey the illusion of life. His backgrounds are always just an empty space; he doesn’t even know how to make the principals stand out of a crowd . . . . Lumet is prodigal with bad ideas . . . . He will take the easiest way to get a powerful effect; in some conventional, terribly obvious way he will be “daring” . . . The emphasis on immediate results may explain the almost total absence of nuance, subtlety, and even rhythmic and structural development in his work. . . . I was torn between detesting his fundamental tastelessness and opportunism and recognizing that at some level it all works. . . . Because Lumet can believe in coarse effects he can bring them off.

He is also a severely deficient human specimen.

[He was] the driving little guy who talked himself into jobs . . . He seems to have no intellectual curiosity of a more generalized or objective nature . . . For Lumet, a woman shouldn’t have any problems a real man can’t take care of . . . . He’ll go on faking it, I think, using the abilities he has to cover up what he doesn’t know.

Kael has her generous moments, praising Long Day’s Journey into Night (1962), chiefly because of the performers, and in later years she would admire scenes in Dog Day Afternoon (1975). But usually her admiration boomerangs into a complaint (Lumet yields a fast pace, but that makes him slapdash). On the whole she and her Manhattan peers, who seldom agreed on anything, conceived Lumet as dangerous.

Why? Partly because they mostly set themselves against the middlebrow culture of the newspapers and newsweeklies. Many of Lumet’s early films were admired by staid critics. Praise from these quarters was anathema to the sophisticates. Somebody had to tell the Times’ Bosley Crowther that The Pawnbroker (1965) was not “a powerful and stinging exposition of the need for man to continue his commitment to society.”

Another strike against Lumet was his pedigree. He was said to have brought TV technique, simultaneously bland and aggressive, to theatrical cinema. Early live TV drama, confined by the home screen’s 21-inch format and weak resolution and hamstrung by punishing shooting schedules, pushed directors to rely on flatly staged mid-range shots, goosed up with close-ups, fast cutting, and meaningless camera movements.

Kael suggests that Frankenheimer, a common foil to Lumet at the period, managed in films like The Manchurian Candidate (1962) to convert the TV look into “a new kind of movie style,” though she never explains what that consists of. By contrast, Lumet simply followed the line of least resistance, emptying out his shots and “hammering some simple points home.”

There’s nothing on the screen for your eye to linger on, no distance, no action in the background, no sense of life or landscape mingling with the foreground action. It’s all there in the foreground, put there for you to grasp at once.

The TV style threatened to suffocate the glories of cinema: the full view, a more leisurely unfolding of action, a sense of life flickering on the edges of the plot. For Kael the TV-trained Lumet exemplifies the loss of the great tradition of artistic moviemaking personified in Jean Renoir.

Lumet was dangerous in another way. He seemed part of a trend toward heavy-handed showoffishness. Partly the trend was seen in the sweaty strain of Method acting, typified in Kazan’s work. Manny Farber proposed that the Method was at the center of the “New York film,” a fake realist package predicated on psychodrama, arty compositions, and liberal pieties. 12 Angry Men was “counterfeit moviemaking,” filled with “schmaltzy anger and soft-center ‘liberalism.’” Hard-sell cinema, Farber called it. Dwight Macdonald saw the same bludgeoning in The Fugitive Kind.

Lumet’s direction is meaninglessly over-intense; lights and shadow play over the close-up faces underlining lines that are themselves in bold capitals; every situation is given end-of-the-world treatment.

The new tendency toward self-conscious artifice didn’t just have New York roots. The French New Wave’s somewhat disjunctive cutting, unexpected camera movements, freeze-frames, and other flagrant techniques made audiences and filmmakers aware of film style to a new degree. Tony Richardson, John Schlesinger, and other directors scavenged these devices to give their films an up-to-date panache. Once more a critic needed to invent a new label for Lumet: Macdonald claimed that he was an exponent of the Bad Good Movie, “the movie that is directed up to the hilt, avant-garde wise,” in the vein of Mickey One, The Servant, The Trial, and the work of Godard. The Pawnbroker’s fragmentary flashbacks led Sarris to call it Harlem mon amour.

Harsh as they are, these comments do have a point. The early films shout and scream a lot, both dramatically and pictorially. Lumet admitted his love of melodrama, conceiving it not simply as overplaying but rather as conflict at the highest pitch of arousal: extreme personalities in extreme situations. So a silence is usually prelude to an outburst, and a bellow or a slap is never far off. The jury deliberations in 12 Angry Men (1957) become a group therapy session (or an Actors Studio class?) in which bigots must confess their traumas.

Stage Struck (1958) and The Group (1966) are pictorially innocuous, perhaps partly because they were shot in color, but The Fugitive Kind (1960) is a banquet of elaborate lighting effects whipped up by Kaufman. Macdonald wasn’t fair in his dismissal; the film is dominated by medium and long shots, with close-ups held in reserve for big moments, and the line readings don’t seem to me as overbearing as he suggests. Still, there is a sense of pressure, with very precise reframings and sets densely packed (mirrors, curtains, staircase railings) in a way that accords well with Williams’ overripe dialogue. There is an upside-down shot, and at some moments, as Macdonald notes, the illumination lifts or drops in magical ways—a surprise gift, Lumet claims, from Kaufman.

As a pluralist, Lumet would stage some scenes in full shots and long takes, sometimes at a surprising distance from the camera. But it was hard not to notice the other extreme. His most famous black-and-white films mixed in tight close-ups, oppressive sets, wide-angle distortions, and chiaroscuro. 12 Angry Men is relatively subdued in this regard, building toward more looming images at the climax, with some powerfully jammed ensemble frames.

Fail-Safe (1964) surrenders itself to flamboyant shot design once we get into the war room and then into the President’s sealed chamber. Contra Kael, as in 12 Angry Men, many of these shots have busy backgrounds, albeit not of the Renoirian sort.

The Pawnbroker (1965) is Lumet’s most famous orgy of strident technique, with Sol Nazerman nearly as caged at his counter window as he was in the camps. Even more overwrought is The Hill (1965) in which short lenses pump officers’ raging faces into gargoyle shapes, with pores and welts and gobs of sweat thrust under our noses.

In sum, this is not the director eulogized in Entertainment Weekly: “He never tried to dazzle audiences with flash and style.”

What critics didn’t note, however, was that the more outré look cultivated by Lumet, Frankenheimer, Ritt, and company fitted fairly snugly into 1950s Hollywood black-and-white dramatic style. The blaring deep-focus and violent close-ups exploited by the TV-born directors were already visible in the work of Mann (The Tall Target, 1951, below), Aldrich (Attack! 1956, below), Fuller, and many other directors.

During the 1950s what we might call roughly the “post-Welles” look was well-established for serious subjects and genre pictures alike. The Hill pushes things a bit, as Frankenheimer did in Seconds (1966), but the cramped, low-angle style on display in Lumet’s early work is part of a tradition that goes back years (and which had its echoes in many overseas directors, such as Bergman and Fellini). The wilder reaches of that style, it now seems clear, belonged to Fuller and company, not to mention the Kubrick of Strangelove and the Welles of Touch of Evil. Like Richardson, Schlesinger, and others, the TV émigrés may have gotten their wrists slapped for trying to map onto prestigious social-message movies the visual pyrotechnics already acceptable for program pictures.

Not incidentally, some directors had already found the wide-angle deep-focus look useful in their TV productions. Below are frames from Requiem for a Heavyweight (directed by Ralph Nelson, Playhouse 90, 1956); The Defender (directed by Robert Mulligan, Westinghouse Studio One, 1957); and Lumet’s own omnibus program Three Plays by Tennessee Williams (Kraft Television Theatre, 1958).

You can argue that their move to cinema actually smoothed out the directors’ style. The less square frame and bigger scale of the theatre screen made films like Frankenheimer’s debut The Young Stranger (1957) more spacious and relaxed than what could be seen on the box. 12 Angry Men was a polished effort, starting with an elaborately staged six-minute crane shot assembling the cast in the jury room, and using the width of the screen to enclose several faces. Looking back, we can see that Lumet offered something quite close to then-current Hollywood norms, and it looked less crude than what would be found on live TV of the period.

Still, The Pawnbroker and other films can be credited (or blamed) with helping spread the in-your-face style that would come to dominate American cinema of the next fifty years: disjunctive editing, slow motion, the arcing tracking shot (The Group), handheld shooting for moments of violence or anguish, glum color schemes (preflashing for The Deadly Affair), the teasing flashbacks that will be gradually filled in. Lumet’s early films are anthologies of most of today’s tics and tricks.

Yet by the time of his death, the director who was once feared as the vanguard of something new and awful had come to embody something old and trustworthy. Somehow the unambitious journeyman and pretentious copycat became a “classicist.”

How did that happen?

A prince of the city

Before the Devil Know You’re Dead.

Instead of indicating that he was joining or extending a tradition, Lumet reacted to the hailstorm of criticisms with surprising equanimity, at least in the interviews he gave so abundantly throughout his career. He was modest, acknowledging that many of his films turned out to be feeble, and he declared himself a learner. He tried different projects, he said, to improve himself. He wanted to learn to manage color, to work in different genres (e.g., the dark comedy Bye Bye Braverman, 1968), eventually to fall in love with digital video capture. To some extent Lumet changed because he really wanted to learn more and explore various sides of moviemaking.

Lumet always claimed that he didn’t apply a personal style to his projects; he tried to find the best way to handle the script. He thereby confessed himself to be what auteur critics of the 1960s were calling a “metteur-en-scène,” the director who judiciously enhances the material rather than transforming it to suit his personality. This was probably a good survival strategy in the new churn of the 1970s.

The mid-1970s was the Great Barrier Reef of American cinema. Virtually no members of Hollywood’s accumulated older generations, from Hitchcock and Hawks through the 1940s debutantes (Wilder, Dmytryk, Fuller, Siegel) and the 1950s tough guys (Aldrich, Brooks) to the TV émigrés, made it through to 1980. Many careers just petered out. The future belonged to the youngsters, the so-called Movie Brats. In this unfriendly milieu, Lumet fared better than most. He tried a semifarcical heist film (The Anderson Tapes, 1971) that mocked the rise of the surveillance society, with everybody wiretapping and taping and videoing everybody else. He mounted a classic mystery (Murder on the Orient Express, 1974), a musical (The Wiz, 1978), and a free-love romance (Lovin’ Molly, 1974). Of the items I’ve seen from these years, the most daring is The Offence (1972). This study of a sadistic British police inspector’s vendetta against a child molester offers a sort of seedy expressionism. In another gesture toward psychodrama, long conversations with the perpetrator reveal that the copper is a bit of a perv himself.

Lumet’s most successful rebranding took place in a sidelong return to the Pawnbroker milieu: low-end, location-shot, crime-tinged social commentary using New York theatre talent. Filming in color and casting off the baroque precision of the earlier work, he made his compositions more casual and his shot changes less precise. His cutting pace picked up: six seconds on average for Serpico (1973), five for Dog Day Afternoon (1975), both courtesy of the high priestess of the quick cut, Dede Allen. The driving tempo of these movies gave them an urgency that critics could tie to the ticking-clock plots, the atmosphere of urban pressure, and of course the extroverted acting of Al Pacino.

With the two crime films, and the satiric Chayefsky talkfest Network, Lumet remade his image. He was a New York filmmaker, offering raucous, hard-nosed, semi-cynical takes on corruption in the police, the justice system, politics, and the media. His protagonists tended to be Jews, Italians, and Irish, all working stiffs or bare-knuckle power brokers; and the enemy, again and again, turned out to be the Ivy elite. A tailor-suited WASP, male or female, was likely to sell you out. Only ethnic minorities knew the real score. The line could come from almost any mid-career Lumet film: “I know the law. The law doesn’t know the streets.”

The crowning achievement in this vein, for critics if not for audiences, was Prince of the City, a sprawling study of a cop’s patient years of taping and informing on his corrupt colleagues. More slowly paced than the earlier urban dramas, the film also marked Lumet’s move toward something else again. The style was drier and more sober, almost passive, emphasizing static and somewhat distant setups; the cutting slowed down to nearly nine seconds on average. As mid-period Lumet had blotted out the early years, now something more calm, even comparatively austere, came into view.

Whatever the project, however, by the later 1980s he was offering his own alternative to the fast-cut, whirlicam style that was bewitching young filmmakers. While directors in all genres were building scenes out of endless choker close-ups and cutting every four or five seconds, Lumet applied the brakes, lingering on two-shots, letting whole scenes play out in full frame, moving his actors around and ordaining a cutting pace close to ten seconds on average. The first eight minutes of The Verdict (1982) consist almost entirely of long shots and extreme long shots. The protracted takes and antic bodily contortions of Deathtrap might have come from a French boulevard farce; the first tight single of Christopher Reeves is delayed for half an hour. In an age in which critics decried the choppy confusion of tentpole action, the plainness on display in movies like Running on Empty (1988) and Night Falls on Manhattan (1997) looked anachronistic. Right to the end, Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead (2007) could spare a lengthy and distant shot to register a high-end drug boutique and shooting gallery. We had come from the Hysterical Lumet by way of the Gritty Lumet to the Restrained Lumet.

Acting in the frame

Yet he did not milk the urban crime vein dry. He continued to try a wide range of projects, even probing the Red Scare in Daniel (1983). The rationale was chiefly performance. Lumet was an “actor’s director.” He demanded at least two weeks of rehearsals, which included not only table readings but eventually full blocking of scenes, including fights and chases. Derived from his TV and theatre days, the method suited his belief that actors needed a firm structure in order to invent their characters. Interestingly, this actors-first rationale can be adjusted to any phase of the rough stylistic development I’ve plotted. The high-pressure facial shots of the early films can highlight the minutiae of the performances. But so can mid-shots that let actors build in bits of business.

Manny Farber praised the moment when Fonda in 12 Angry Men dries his fingers at length, one by one. It shows, Farber says, “the jury’s one sensitive, thoughtful figure to be unusually prissy” and provides a “mild debunking of the hero.” But it’s not the unintegrated detail Farber claims; Fonda’s coldness is set up early in the film, when he stands remotely from his peers and shows no interest in them as men. And Fonda was always a master of finger-work, which Lumet could exploit in fastidious framings. In Fail-Safe as the President tries to halt the bombers rushing toward the USSR, Fonda projects the man’s minutely controlled apprehensions by pausing to rub his fingertips together, off in the corner of the shot.

This micro-gesture suddenly leaps, as Eisenstein might say, into a new quality: a worried facial expression.

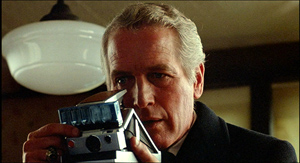

More explicit is the characterizing moment in The Verdict when Frank Galvin (Paul Newman) starts his day with a sugar donut and a full glass of whiskey. The setup is concise: He has crossed off the wakes he’s visited, and his palsied hand can’t pick up the glass without spilling some.

So Frank checks to see if anyone is looking before, like a dog, he bends his head to slurp off a little.

It’s a simple but powerful image of degradation, far removed from the trembling mouth and bulging brows of Steiger in The Pawnbroker.

Lumet cared as much for camera technique as for acting maneuvers. His book Making Movies provides a virtual manual of movie style as draftboard engineering. His gearhead side was probably another legacy of the buccaneering days of live TV and the New-Wave inspired awareness of artifice. He took inordinate pride in his “lens plots” and lighting arcs, charting purely technical changes that would weave their way through the film. (In this he was ahead of his time; now most filmmakers develop these technique arcs, or at least they say they do.) Despite this almost mechanical conception of technique, though, late Lumet rediscovered a bare-bones simplicity of performance and framing that was willing to risk looking flat. In Daniel, he lets the angry young man whose sister has wasted away into madness confront the poster agitating for their dead parents. No tracking in, no circumnambulating camera, no heightened cuts or nudging score. And no need to see Daniel’s face. Susan merely lifts her head.

It’s as if the visual rodomontade of the Movie Brats drove Lumet toward a new sobriety. When Galvin is preparing to try the case of the girl left in a coma through medical malpractice, he visits the hospital and takes Polaroids of her inert body. The slowly developing images not only give us the fullest view of the girl we’ve had so far. They also come to suggest his dawning realization that this is more than just a chance for big money.

Galvin starts to grasp that letting the hospital settle out of court will allow the officials to write off their mistake. There is a human cost to simply getting the check. If he does it, he will now be a better-paid ambulance chaser. Yet he doesn’t stand valiant for truth; the drunk is scared, drained of dignity, and he clutches his portfolio as a sad, ineffectual shield.

Offered the money, Frank takes out the photos and weighs them against the check. Then with a sigh of exhaustion, contemplating the fool’s crusade he’s launching, he returns the check and drops the pictures into his bag.

Very simple visual storytelling; it might have come from a 1930s movie. But this stark presentation of moral decision, given as a straightforward framing of a man’s body, achieves a measure of artistic nobility in a year that gave us Porky’s and Rocky III.

Telling it all, holding some back

Prince of the City.

It’s good to remember such moments of pictorial storytelling because Lumet’s films, especially the early ones, tend to be gabfests. If Eugene O’Neill, Tennessee Williams, and Paddy Chayefsky, along with the Method acting tradition, are your coordinates, you will be drawn to chatterboxes and blowhards. Lumet loved the spoken word, which was after all the mainstay of live TV (“illustrated radio,” it was sometimes called). It’s not clear that he ever shook the habit. His characters usually step onstage leaking exposition, announcing their pasts, their personalities, their plans, and their deepest feelings. This has the advantage of making plot premises clear, but it reduces the figures’ mystery and their ability to surprise us, or to complicate our feelings about them.

Sometimes Lumet did let story construction do heavier lifting. It happens in The Pawnbroker, because the nearly catatonic Nazerman speaks so little that the fusillade of flashbacks provides his backstory. More daringly, the large-scale back-and-fill of The Offence, peppered with small memories but also looping around the central incident in the interrogation room, seeks to reveal Sergeant Johnson’s affinities with the suspected child murderer. We need to remember Lumet’s early fondness for time-shifting plots before we declare Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead an old guy’s effort to catch up with Pulp Fiction.

Even without benefit of broken timelines, Lumet could occasionally hold back information to reshape our first impressions. Take the central revelation of Dog Day Afternoon, when cuddly Al Pacino reveals that his “wife” is not the woman he’s married to (a nice plot feint here) but the man whom he loves. This apparently sensationalistic twist comes early enough to modulate into pathos when Pacino’s character dictates his two wills.

Prince of the City realigns our sympathies in a more intricate way. At the start, Danny is presented as a tormented soul. We’re led to think that he turns snitch because of things we see: the invitation to go undercover, his brother’s and father’s angry concern that his pals are crooked, and above all the shameful efforts he makes to get drugs for his informant. Once he turns, however, he can’t limit the investigation, and at nearly the end his treachery has broken the most important ties in his life.

But “nearly the end” is the operative term, because Prince of the City boldly appends a ten-minute epilogue showing Danny being investigated himself. The Danny we saw at the film’s beginning may have been steeped in corruption; the drug bust we saw included, behind the scenes, a major ripoff of money; he has lied more than we realized; and it seems likely that he cheated on his wife with the prostitutes whom he supplied with drugs.

A modern filmmaker, or Lumet in his bodacious early mode, might have spiced these flat testimony scenes with lurid flashbacks. But sticking simply to Danny’s feeble, evasive stonewalling raises questions of his own vulnerability. Having watched him break down over years and having heroicized his suffering to a considerable degree, we have to judge him anew. Is he simply too weary to fight the charges, or has he been caught out? The ending might seem to allow for cynicism, but we can’t cast off our respect for what Danny has risked.

Further, Lumet intercuts the court scenes with government meetings about whether to prosecute Danny. In the manner of a Shavian problem play, this tactic obliges our sympathies to be clear-eyed. If The Verdict lays all its cards on the table and invites straightforward sympathy for Galvin, Prince of the City, by hiding major aspects of Danny’s character and circumstance, leads us to a more nuanced experience. The narrational dynamic of the film invites us to rethink our protagonist’s actions and decide whether to grant him mercy.

In the vanguard of a new style in the 1960s, Lumet remade himself as part of the 70s renaissance. That freed him to cover nearly every bet on the board, and some paid off. As hotshot younger directors sped past him into tentpole territory, he put the independent sector to use–financing through presales, working with stars on the way down and on the way up, releasing the films through boutique distributors, trying many options with a stubborn pragmatism. He handled failure, ignoral, and disdain better than probably any of us could. “Though his films are invariably flawed,” wrote Sarris in 1968, “the very variety of the challenges constitutes a sort of entertainment.” This zigzag career trajectory provides a unique, even heartening EKG of success and survival in the modern American film industry.

At the same time, he helped make audiences and critics more conscious of film technique, in ways both salutary and damaging. He was part of my film school: The very first movie I saw in a theatre during my freshman year of college was The Pawnbroker, and I revisited it several times. Here was a modern instance of “pure cinema,” worth comparing with A Hard Day’s Night and 8 1/2. (Yes, I hadn’t seen much.) Prince of the City has drawn me since I first saw it in a moldy two-screener in Florida and thought: “Can Hollywood have made a Brechtian film?” I leave for another time the tale of watching Prince in a nearly empty screening sponsored by Nick Cave.

You can probably tell that Lumet is not my favorite filmmaker. Several of his movies I earnestly hope never to see again, and even the ones I admire contain moments I would wish otherwise. But he has given me unique pleasures and prodded me to ask some questions that intrigue me. More broadly, I can’t understand the failures and accomplishments of modern American film without taking into account this marathon man.

For this entry, I haven’t managed to see or re-see as much of the Lumet output as I’d hoped, but the twenty-three films I revisited include his most famous titles (except for The Wiz, which might better be called infamous). My comments here supplement those I make about Lumet and his generation in The Way Hollywood Tells It, 145-147.

I’ve drawn my critics’ quotations from anthologies of their writings. The one I should probably signal explicitly is Pauline Kael’s “The Making of The Group,” in Kiss Kiss Bang Bang (Little, Brown, 1968). The piece is dated 1966, but I can’t prove that it was actually published then. I find it endlessly interesting, not least because it may help us trace some origins of critical clichés. I’m thinking not only of the art/ business dyad but also the appeal to Renoir as the prototype of the spontaneous film creator. Ironically, for at least some projects we have evidence that Renoir rehearsed his actors quite a bit and retook scenes until he was satisfied. Double irony: Somewhat before Kael was celebrating the careless grace of Renoirian spontaneity, he had in Testament of Dr. Cordelier (1959) turned to a multicamera technique for his own television project. Renoir and Lumet intersect in unexpected ways!

On live TV shooting methods, a succinct overview can be found in Erik Barnouw, Tube of Plenty (Oxford, 1975), 160-166, and of course Gilbert Seldes’ Writing for Television (Doubleday, 1952), which I’ve praised elsewhere on this site. Seldes scatters some intriguing comments on live TV drama through his The Public Arts (Simon and Schuster, 1956). Just as important, Criterion continues to serve film studies by releasing precious documents from early television. Watch the items included in The Golden Age of Television and the three Lumet/ Williams playlets folded into Criterion’s Fugitive Kind box to see what these directors were up against, and with what relief they must have greeted the wider choices available on film.

The indispensable sources on Lumet are the fine collection Sidney Lumet Interviews, ed. Joanna E. Rapf. It’s here that Gavin Smith can be found sketching a case for Lumet as continuing classic Hollywood while also pressing into “80’s modernism” (132). And of course everyone must read Lumet’s own Making Movies. On editing The Pawnbroker, see Ralph Rosenblum and Robert Karen, When the Shooting Stops… The Cutting Begins: A Film Editor’s Story (Penguin, 1975), 145-166. Glenn Kenny has an excellent 2007 interview with Lumet on digital techniques in the DGA Quarterly.

Credits: Stage Struck; Night Falls on Manhattan.

Watching you watch THERE WILL BE BLOOD

DB here:

Today’s entry is our first guest blog. It follows naturally from the last entry on how our eyes scan and sample images. Tim Smith is a psychological researcher particularly interested in how movie viewers watch. You can follow his work on his blog Continuity Boy and his research site.

I asked Tim to develop some of his ideas for our readers, and he obliged by providing an experiment that takes off from my analysis of staging in one scene of There Will Be Blood, posted here back in 2008. The result is almost unprecedented in film studies, I think: an effort to test a critic’s analysis against measurable effects of a movie. What follows may well change the way you think about visual storytelling.

Tim’s colorful findings also suggest how research into art can benefit from merging humanistic and social-scientific inquiry. Kristin and I thank Tim for his willingness to share his work.

Tim Smith writes:

David’s previous post provided a nice introduction to eye tracking and its possible significance for understanding film viewing. Now it is my job to show you what we can do with it.

Continuity errors: How they escape us

Knowing where a viewer is looking is critical to beginning to understand how a viewer experiences a film. Only the visual information at the centre of attention can be perceived in detail and encoded in memory. Peripheral information is processed in much less detail and mostly contributes to our perception of space, movement and general categorisation and layout of a scene.

The incredibly reductive nature of visual attention explains why large changes can occur in a visual scene without our noticing. Clear examples of this are the glaring continuity errors found in some films. Lighting that changes throughout a scene, cigarettes that never burn down, and drinks that instantly refill plague films and television but we rarely notice them except on repeated or more deliberate viewing. In my PhD thesis I created a taxonomy of continuity errors in feature films and related them to various failings during pre-production, filming, and post-production.

Our inability to detect continuity errors was elegantly demonstrated in a study by Dan Levin and Dan Simons. In their study continuity errors were purposefully introduced into a film sequence of two women conversing across a dinner table. If you haven’t seen it before, watch the video here before continuing, and see how many continuity errors you can spot.

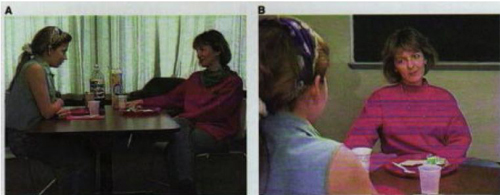

Two frames from the clip used by Levin and Simons (1997). Continuity errors were deliberately inserted across cuts (e.g., the disappearing scarf), and viewers were asked after watching the video whether they noticed any.

The short clip contained nine continuity errors, such as a scarf that changed colour, then disappeared, plates that changed colour and hands that changed position. During the first viewing, viewers were told to pay close attention but were not informed about the continuity errors. When asked afterwards if they noticed anything change, only one participant reported seeing anything and that was a vague sense that the posture of the actors changed. Even during a second viewing in which they were instructed to detect changes, viewers only detected an average of 2 out of the 9 changes and tended to notice changes closest to the actors’ faces such as the scarf.

Although Levin and Simons did not record viewer eye movements, my own experiments investigating gaze behaviour during film viewing indicate that our eyes will mostly be focussed on faces and spend virtually no time on peripheral details. If you as a viewer don’t fixate a peripheral object such as the plate, you are unable to represent the colour of the plate in memory and can, therefore not detect the change in colour when you later refixate it.

Tracking gaze

To see how reductive and tightly focused our gaze is whilst watching a film, consider Paul Thomas Anderson’s There Will Be Blood (TWBB; 2007). In an earlier post, David used a scene from this film as an example of how staging can be used to direct viewer attention without the need for editing.

The scene depicts Paul Sunday describing the location of his family farm on a map to Daniel Plainview, his partner Fletcher Hamilton, and his son H.W. The entire scene is treated in a long, static shot (with a slight movement in at the beginning). Most modern film and television productions would use rapid editing and close-up shots to shift attention between the map and the characters within this scene. This frenetic style of filmmaking–which David termed intensified continuity in his book The Way Hollywood Tells It (2006)–breaks a scene down into a succession of many viewpoints, rapidly and forcefully presented to the viewer.

Intensified continuity is in stark contrast to the long-take style used in this scene from TWBB. The long-take style, which was common in the 1910s and recurred at intervals after that period, relies more on staging and compositional techniques to guide viewer attention within a prolonged shot. For example, lighting, colour, and focal depth can guide viewer attention within the frame, prioritising certain parts of the scene over others. However, even without such compositional techniques, the director can still influence viewer attention by co-opting natural biases in our attention: our sensitivity to faces, hands, and movement.

In order to see these biases in action during TWBB we need to record viewer eye movements. In a small pilot study, I recorded the eye movements of 11 adults using an Eyelink 1000 (SR Research) eyetracker. This eyetracker uses an infrared camera to accurately track the viewer’s pupil every millisecond. The movements of the pupil are then analysed to identify fixations, when the eyes are relatively still and visual processing happens; saccadic eye movements (saccades), when the eyes quickly move between locations and visual processing shuts down; smooth pursuit movements, when we process a moving object; and blinks.

Eye movements on their own can be interesting for drawing inferences about cognitive processing, but when thinking about film viewing, where a viewer looks is of most interest. As David demonstrated in his last post, analysing where a viewer looks whilst viewing a static scene, such as Repin’s painting An Unexpected Visitor, is relatively simple. The gaze of a viewer can be plotted on to the static image and the time spent looking at each region, such as a characters face or an object in the scene can be measured.

However, when the scene is moving, it is much more difficult to relate the gaze of a viewer on the screen to objects in the scene. To overcome this difficulty, my colleagues and I developed new visualisation techniques and analysis tools. These efforts were part of a large project investigating eye movement behaviour during film and TV viewing (Dynamic Images and Eye Movements, what we call the DIEM project). These techniques allow us to capture the dynamics of gaze during film viewing and display it in all its fascinating, frenetic glory.

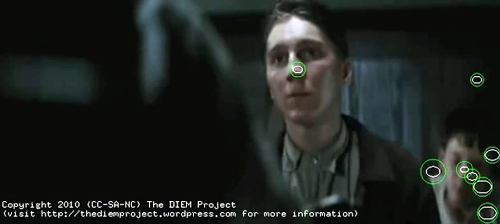

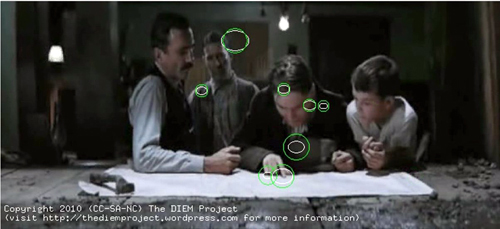

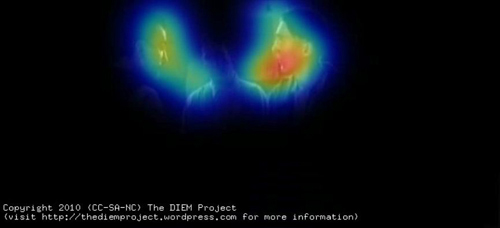

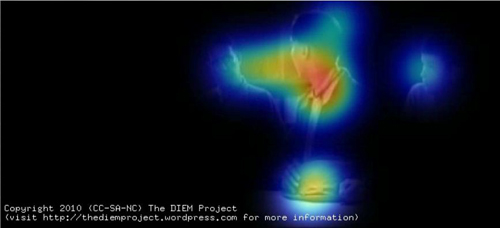

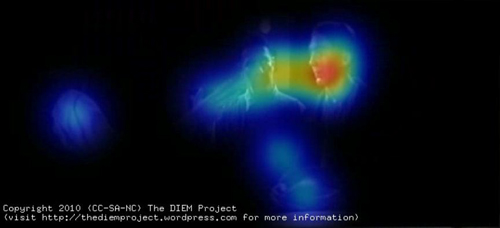

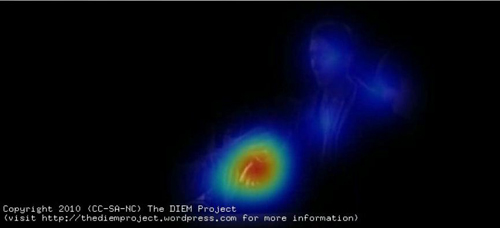

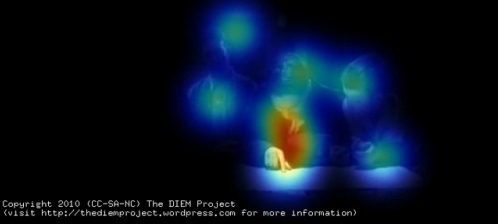

To begin, the gaze location of each viewer is placed as a point on the corresponding frame of the movie. The point is represented as a circle with the size of the circle denoting how long the eyes have remained in the same location, i.e. fixated that location. We then add the gaze location of all viewers on to the same frame. Although the viewers watched the clip at different times, plotting all viewers together allows us to look for similarities and differences between where people look and when they look there. This figure shows the gaze location of 8 viewers at one moment in the scene. (The remaining 3 viewers are blinking at this moment.)

A snapshot of gaze locations of 8 viewers whilst watching the “map” sequence from There Will Be Blood (2007). Each green circle represents the gaze location of one participant, with the size of the circle indicating how long the eyes have been in fixation (bigger equals longer).

You have a roving eye

Plotting static gaze points onto a single frame of the movie allows us to see what viewers were looking at in a particular frame, but we don’t get a true sense of how we watch movies until we animate the gaze on top of the movie as it plays back. Here is a video of the entire sequence from TWBB with superimposed gaze of 11 viewers.

You can also see it here. The main table-top map sequence we are interested begins at 3 minutes, 37 seconds.

The most striking feature of the gaze behaviour when it is animated in this way is the very fast pace at which we shift our eyes around the screen. On average, each fixation is about 300 milliseconds in duration. (A millisecond is a thousandth of a second.) Amazingly, that means that each fixation of the fovea lasts only about 1/3 of a second. These fixations are separated by even briefer saccadic eye movements, taking between 15 and 30 milliseconds!

Looking at these patterns, our gaze may appear unusually busy and erratic, but we’re moving our eyes like this every moment of our waking lives. We are not aware of the frenetic pace of our attention because we are effectively blind every time we saccade between locations. This process is known as saccadic suppression. Our visual system automatically stitches together the information encoded during each fixation to effortlessly create the perception of a constant, stable scene.

In other experiments with static scenes, my colleagues and I have shown that even if the overall scene is hidden 150milliseconds into every fixation, we are still able to move our eyes around and find a desired object. Our visual system is built to deal with such disruptions and perceive a coherent world from fragments of information encoded during each fixation.

The second most striking observation you may have about the video is how coordinated the gaze of multiple viewers is. Most of the time, all viewers are looking in a similar place. This is a phenomenon I have termed Attentional Synchrony. If several viewers examine a static scene like the Repin painting discussed in David’s last post, they will look in similar places, but not at the same time. Yet as soon as the image moves, we get a high degree of attentional synchrony. Something about the dynamics of a moving scene leads to all viewers looking at the same place, at the same time.

The main factors influencing gaze can be divided into bottom-up involuntary control by the visual scene and top-down voluntary control by the viewer’s intentions, desires, and prior experience. As part of the DIEM project we were able to identify the influence of bottom-up factors on gaze during film viewing using computer vision techniques. These techniques allowed us to dissect a sequence of film into its visual constituents such as colour, brightness, edges, and motion. We found that moments of attentional synchrony can be predicted by points of motion within an otherwise static scene (i.e. motion contrast).

You can see this for yourself when you watch the gaze video. Viewers’ gazes are attracted by the sudden appearance of objects, moving hands, heads, and bodies. The greater the motion contrast between the point of motion and the static background, the more likely viewers will look at it. If there is only one point of motion at a particular moment, then all viewers will look at the motion, creating attentional synchrony.

This is a powerful technique for guiding attention through a film. But it’s of course not unique to film. Noticing points of motion is a natural bias which we have evolved by living in the real world. If we were not sensitive to peripheral motion, then the tiger in the bushes might have killed our ancestors before they had chance to pass their genes down to us.

But points of motion do not exist in film without an object executing the movement. This brings us to David’s earlier analysis of the staging of this sequence from TWBB. This might be a good time to go back and read David’s analysis before we begin testing his hypotheses with eyetracking. Is David right in predicting that, even in the absence of other compositional techniques such as lighting, camera movement, and editing, viewer attention during this sequence is tightly controlled by staging?

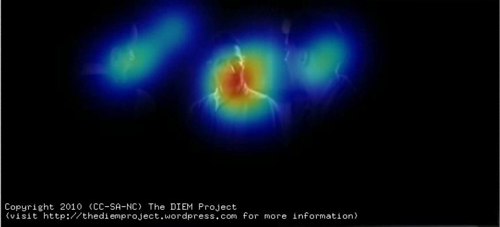

All together now

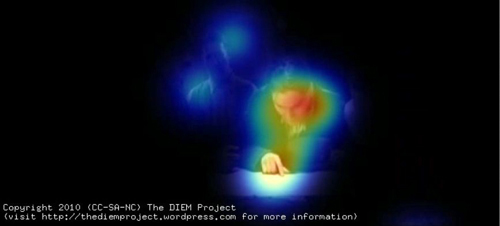

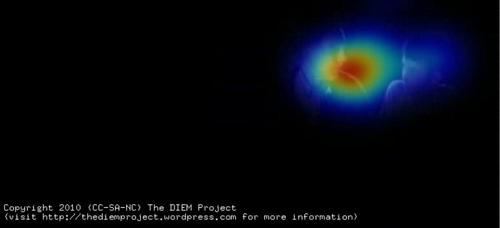

To help us test David’s hypotheses I am going to perform a little visualisation trick. Making sense of where people are looking by observing a swarm of gaze points can often be very tricky. To simplify things we can create a “peekthrough” heatmap. A virtual spotlight is cast around each gaze point. This spotlight casts a cold, blue light on the area around the gaze point. If the gazes of multiple viewers are in the same location their spotlights combine and create a hotter/redder heatmap. Areas of the frame that are unattended remain black. By then removing the gaze points but leaving the heatmap we get a “peekthrough” to the movie which allows us to clearly see which parts of the frame are at the centre of attention, which are ignored and how coordinated viewer gaze is.

Here is the resulting peekthrough video; also available here. The map sequence begins at 3:38.

Here is the image of gaze location I showed above, now matched to the same frame of the peekthrough video.

The gaze data from multiple viewers is used to create a “peekthrough” heatmap in which each gaze location shines a virtual spotlight on the film frame. Any part of the frame not attended is black, and the more viewers look in the same location, the hotter the color.

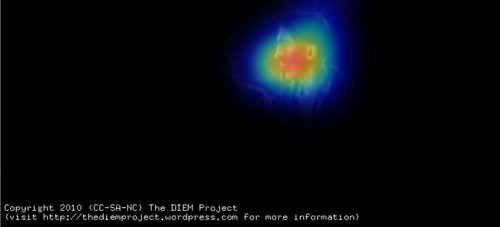

David’s first hypothesis about the map sequence is that the faces and hands of the actors command our attention. This is immediately apparent from the peekthrough video. Most gaze is focused on faces, shifting between them as the conversation switches from one character to another.

The map receives a few brief fixations at the beginning of the scene but the viewers quickly realise that it is devoid of information and spend the remainder of the scene looking at faces. The only time the map is fixated is when one of the characters gestures towards it (as above).

We can see the effect of turn-taking in the conversation on viewer attention by analyzing a few exchanges. The sequence begins with Paul pointing at the map and describing the location of his family farm to Daniel. Most viewers’ gazes are focused on Paul’s face as he talks, with some glances to other faces and the rest of the scene. When Paul points to the map, our gaze is channeled between his face and what he is gazing/pointing at.

Such gaze prompting and gesturing are powerful social cues for attention, directing attention along a person’s sightline to the target of their gaze or gesture. Gaze cues form the basis of a lot of editing conventions such as the match an action, shot/reverse-shot dialogue pairings, and point-of-view shots. However, in this scene gaze cuing is used in its more natural form to cue viewer attention within a single shot rather than across cuts.

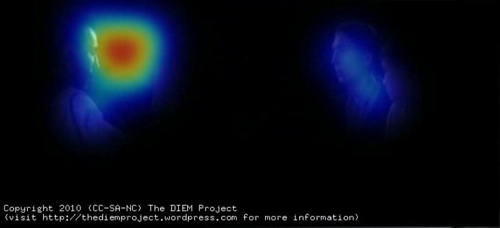

As Paul finishes giving directions, Daniel asks him a question which immediately results in all viewers shifting the gaze to Daniel’s face. Gaze then alternates between Daniel and Paul as the conversation passes between them. The viewers are both watching the speaker to see what he is saying and also monitoring the listener’s responses in the form of facial expressions and body movement.

Daniel turns his back to the camera, creating a conflict between where the viewer wants to look (Daniel’s face) and what they can see (the back of his head). As David rightly predicted, by removing the current target of our attention the probability that we attend to other parts of the scene is increased, such as H. W., who up until this point has not played a role in the interaction. Viewers begin glancing towards HW and then quickly shift their gaze to him when he asks Paul how many sisters he has.

Gaze returns to Paul as he responds.

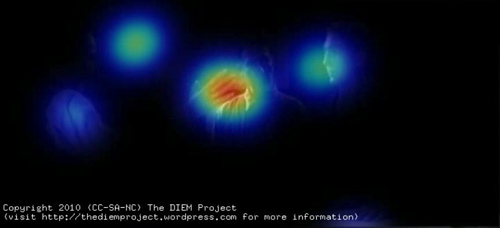

Gaze shifts from Paul to Daniel as he asks a short question, and then moves to Fletcher as he joins the conversation.

The quick exchanges of dialogue ensure that viewers only have enough time to shift their gaze to the speaker and then shift to the respondent. When gaze dwells longer on a speaker, such as during the exchange between Fletcher and Paul, there is an increase in glances away from the speaker to other parts of the scene such as the other silent faces or objects.

An object that receives more fixations as the scene develops is Paul’s hat, which he nervously fiddles with. At one point, when responding to Fletcher’s question about what they grow on the farm, Paul glances down at his hat. This triggers a large shift of viewer gaze, which slides down to the hat. Likewise, a subtle turn of the head creates a highly significant cue for viewers, steering them towards what Paul is looking at while also conveying his uneasiness.

The most subtle gesture of the scene comes soon after as Fletcher asks about water at the farm. Paul states that the water is generally salty and as he speaks Fletcher shifts his eyes slightly in the direction of Daniel. This subtle movement is enough to cue three of the viewers to shift their gaze to Daniel, registering their silent exchange.

This small piece of information seems critical to Daniel and Fletcher’s decision to follow up Paul’s lead, but its significance can be registered by viewers only if they happened to be fixating Fletcher at the time he glanced at Daniel. The majority of viewers are looking at Paul as he speaks and they miss the gesture. For these viewers, the significance of the statement may be lost, or they may have to deduce the significance either from their own understanding of oil prospecting or other information exchanged during the scene.

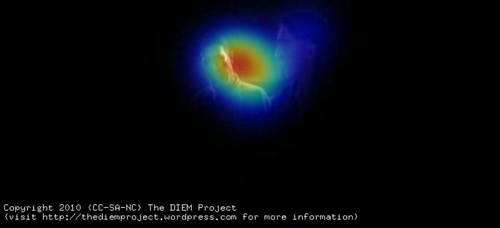

The final and most significant gesture of the scene is Daniel’s threatening raised hand. As Paul goes to leave, Daniel stalls him by raising his hand centre frame in a confusing gesture hovering midway between a menacing attack and a friendly handshake. In David’s earlier post he predicted that the hand would “command our attention.” Viewer gaze data confirm this prediction. Daniel draws all gazes to him as he abruptly states “Listen….Paul,” and lifts his hand.

Gaze then shifts quickly; the raised hand becomes a stopping off point on the way to Paul’s face. . .

. . . finally following Daniel’s hand down as he grasps Paul’s in a handshake.

We like to watch

The rapid sequence of actions clearly guide our attention around the scene: Daniel – Hand -Paul – Hand. David’s analysis of how the staging in this scene tightly controls viewer attention was spot-on and can be confirmed by eyetracking. At any one moment in the scene there is a principal action signified either by dialogue or motion. By minimising background distractions and staging the scene in a clear sequential manner using basic principles of visual attention, P. T. Anderson has created a scene which commands viewer attention as precisely as a rapidly edited sequence of close-up shots.

The benefit of using a single long shot is the illusion of volition. Viewers think they are free to look where they want but, due to the subtle influence of the director and actors, where they want to look is also where the director wants them to look. A single static long shot also creates a sense of space, clear relationship between the characters, and a calm, slow pace which is critical for the rest of the film. The same scene edited into close-ups would have left the viewer with a completely different interpretation of the scene.

I hope I’ve shown how some questions about film form, style, practice, and spectatorship can be informed by borrowing theory and methods from cognitive psychology. The techniques I have utilised in recording viewer gaze and relating it to the visual content of a film are the same methods I would use if I was conducting an experiment on a seemingly unrelated topic such as visual search. (See this paper for an example.)

The key difference is that the present analysis is exploratory and simply describes the viewing behaviour during an existing clip. What we cannot conclude from such a study is which aspects of the scene are critical for the gaze behaviour we observe. For instance, how important is the dialogue for guiding attention? To investigate the contribution of individual factors such as dialogue we need to manipulate the film and test how gaze behaviour changes when we add or remove a factor. This type of empirical manipulation is critical to furthering our understanding of film cognition and employing all of the tools cognitive psychology has to offer.

But I expect an objection. Isn’t this sort of empirical inquiry too reductive to capture the complexities of film viewing? In some respects, yes. This is what we do. Reducing complex processes down to simple, manageable, and controllable chunks is the main principle of empirical psychology. Understanding a psychological process begins with formalizing what it and its constituent parts are, and then systematically manipulating and testing their effect. If we are to understand something as complex as how we experience film we must apply the same techniques.

As in all empirical psychology the danger is always that we lose sight of the forest whilst measuring the trees. This is why the partnership between film theorists and empiricists like myself is critical. The decades of film theory, analysis, practice and intuition provide the framework and “Big Picture” to which we empiricists contribute. By sharing forces and combining perspectives, we can aid each other’s understanding of the film experience without losing sight of the majesty that drew us to cinema in the first place.

On the importance of foveal detail for memory encoding, see J. M. Findlay, Eye scanning and visual search, in The Interface of Language, Vision, and Action: Eye movements and the visual world, ed. J.M. Henderson and F. Ferreira (New York: Psychology Press, 2004), pp. 134-159. Levin and Simons’ continuity-error experiment is explained in D. T. Levin and D. J. Simons, “Failure to detect changes to attended objects in motion pictures,” Psychonomic Bulletin and Review4 (1997), pp. 501-506.

A note about our equipment and experimental procedure. We presented the film on a 21 inch CRT monitor at a distance of 90cm and a resolution of 720×328, 25fps. Eye movements were recorded using an Eyelink 1000 eyetracker and a chinrest to keep the viewer’s head still. This eye tracker consists of a bank of infrared LEDs used to illuminate the participant’s face and a high-speed infrared camera filming the face. The infrared light reflects of the face but not the pupil, creating a dark spot that the eyetracker follows. The eyetracker also detects the infrared reflecting off the outside of the eye (the cornea) which appears as a “glint”. By analysing how the glint and the centre of the pupil move as the viewer looks around the screen the eyetracker is able to calculate where the viewer is looking every millisecond.

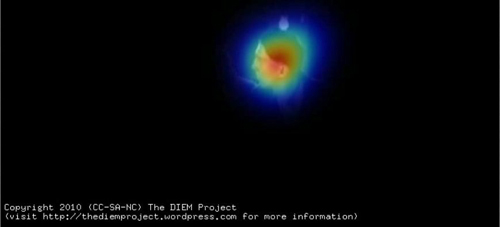

As for the heatmaps, the greater the number of viewers, the more consistent the heatmaps. The present pilot study used gaze from only 11 viewers, which introduces a lot of noise into the visualisations. Compare the scattered nature of the gaze in the TWBB video to a similar scene visualised with the gaze of 48 viewers. We would probably see the same degree of coordination in the TWBB clip if we had used more viewers.

For a comprehensive discussion of attentional synchrony and its cause, see Mital, P.K., Smith, T. J., Hill, R. and Henderson, J. M., “Clustering of gaze during dynamic scene viewing is predicted by motion,” Cognitive Computation (in press). Social cues for attention, like shared looks, are discussed in Langton, S. R. H., Watt, R. J., & Bruce, V., “Do the eyes have it? Cues to the direction of social attention,” Trends in Cognitive Sciences 4, 2, pp. 50-59. For more on our inability to detect small discontinuities, see Smith, T. J. and Henderson, J. M., “Edit Blindness: The relationship between attention and global change blindness in dynamic scenes,” Journal of Eye Movement Research (2008) 2 (2), 6, pp. 1-17.

For further information on the Dynamic Images and Eye Movement project (DIEM) please visit http://thediemproject.wordpress.com/. This research was funded by the Leverhulme Trust (Grant Ref F/00-158/BZ) and the ESRC (RES 062-23-1092). To view more visualisations from the project visit this site. The DIEM project partners are myself, Prof. John M Henderson, Parag Mital, and Dr. Robin Hill. Gaze data and visualisation tools (CARPE: Computational and Algorithmic Representation and Processing of Eye-Movements) can also be downloaded from the website. When using or referring to any of the work from DIEM, please reference the Cognitive Computation paper cited above.

Wonderful work in this area has already been conducted by Dan Levin (Vanderbilt), Gery d’Ydewalle (Leuven), Stephan Schwan (KMRC, Tübingen), and the grandfather of the recent revival in empirical cognitive film theory, Julian Hochberg. I am indebted to their pioneering work and excited about taking this research area forward.

Finally, I would like to thank David and Kristin for inviting me to describe some of my work on their wonderful blog. I have been an avid follower of their work for years and David has been a great supporter of my research.

DB PS 26 February: The response to Tim’s blog has been astonishing and gratifying. Tens of thousands of visitors have read his essay here, and his videos have been viewed over 700,000 times on sites across the Web. I’m very happy that so many non-psychologists–scholars, critics, and filmmakers–have found something of value here. The extended discussion on Jim Emerson’s scanners site, in which I participated a little, is especially worth reading. For more comments and replies from Tim and his team, go to Tim’s Continuity Boy blogpage and the DIEM team’s Vimeo page. At Continuity Boy, Tim will post more videos based on his group’s experimental efforts.

DB PS 18 October: Tim has posted a new, equally interesting experiment on tracking non-visible (!) movement on his blogsite.

THE SOCIAL NETWORK: Faces behind Facebook

DB here:

What do John Ford, Andy Warhol, and David Fincher have in common? Eyeball these remarks.

Ford, asked what the audience should watch for in a movie: “Look at the eyes.”

Warhol: “The great stars are the ones who are doing something you can watch every second, even if it’s just a movement inside their eye.”

Fincher, on the big club scene in The Social Network: “What’s cinematic are the performances . . . . What their eyes are doing as they’re trying to grasp what the other person is telling them.”

It isn’t just cinema that makes eyes important. Eyes are felt to be significant in literature, from the highest to the lowest. In just a couple of pages of a pulp adventure story you can read these sentences:

“Then it certainly does look very mysterious,” he said, but his blue eyes were quiet and searching.

Chief Inspector Teal suddenly opened his baby-blue eyes and they were not bored or comatose or stupid, but unexpectedly clear and penetrating.

What do quiet eyes look like, actually? Or searching ones: perhaps they’re moving a bit? Bored or comatose eyes might be droopy, so let’s count the eyelids as part of the eye. But what could make eyes, by themselves, penetrating? Nonetheless, we think we understand what such sentences mean.

Watching eyes is tremendously important in our social lives. We need to monitor other people’s glances to see if they are looking at us. We need to track what else they might be looking at. We need to watch for signals sent by the eyes, particularly attitudes toward the situation we’re in. For example, we seldom look directly into each others’ eyes, as characters in movies do constantly; in real life, “mutual gaze” is intermittent and brief. But if two people stare intently at each other, we’re likely to assume keen attraction or rising aggression.

In an essay from Poetics of Cinema available on this site, I talk about mutual gaze in cinema and how it can be exploited for dramatic purposes. The same essay takes up the issue of blinking; we blink frequently, but film characters seldom do, and the actors usually make the blinks emotionally expressive (of fear, uncertainty, weakness, etc.).

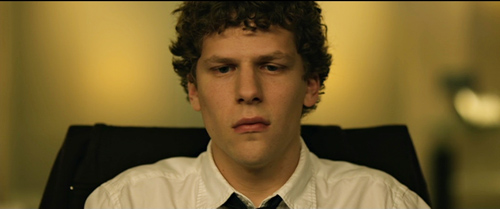

The problem is that eyes, by themselves, tell us very little about what the person behind them is thinking or feeling. We can show this with a little experiment.

Do the eyes have it?

What do these eyes tell us?

Certainly they give us information–about the direction the person is looking, about a certain state of alertness. The lids aren’t lifted to suggest surprise or fear, but I think you’d agree that no specific emotion seems to emerge from the eyes alone.

So what happens if we add eyebrows? (I’ve tipped the one above to conceal the brows; now you get to see the face’s proper angle.)

Now there’s a degree of surprise. The brows are lifted somewhat. But still the emotion seems fairly unspecific: not particularly sad or angry or distressed; probably not joyous either. Then what?

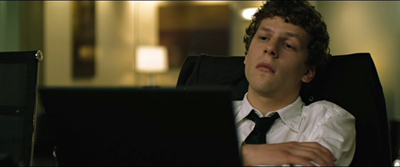

I’d call this dazed, slightly perplexed surprise. The sloping brows suggest the man is trying to figure out what’s happened; but the mouth is a slight gape. You can almost imagine the lips murmuring: “Ohhh,” or “Wow,” and not in appreciation or pleasure. If you wanted to show someone being blindsided, this is a pretty precise way to do it.

Of course context helps us a lot. Eduardo Savarin has just been gulled by his partner Mark Zuckerberg and by the interloper Sean Parker. His stock in the company that he co-founded is now worthless. So the situation informs our reading of Eduardo’s expression, and this permits the actor to underplay. Actor Andrew Garfield doesn’t give us bug-eyed surprise or frowning bafflement; he relies on our understanding of what he must be feeling (what we would feel) in order to refine and nuance his expression. When an actor underacts, we’re often expected to fill in the emotions we could plausibly imagine him to be feeling, on the basis of the story at this point. In isolation, the expression might be vague or ambiguous; the narrative situation helps sharpen it.

Back to the main question: How informative are the eyes alone? Try this one.