Archive for the 'Readers’ Favorite Entries' Category

Has 3D already failed? The sequel, part 2: RealDsgusted

Kristin here–

For part 1, see here.

Darn those quickie conversions!

In past years, 3D proselytizer Jeffrey Katzenberg, head of Dreamworks Animation, has complained about the slow progress of the conversation of theaters to digital and 3D projection. By September, 2010, faced with a growing backlash against the technology, he was more concerned about the conversion of films shot in 2D to 3D. The 3D Hollywood in Hi Def site reported:

Jeffrey Katzenberg opened the 3D Entertainment Summit with his usual provocative verbal flare [sic], defending 3D successes against the recent growing tide of critics claiming it is already dying — “It seems there are some in Hollywood who are determined to seize defeat from the jaws of victory. Six of the top 10 movies this year are 3D; I guess we have to have 10 of 10.” — and lambasting filmmakers and studios who convert movies to 3D after they are produced in 2D, calling them “downright ugly” and claiming they are endangering the technology that is single-handedly responsible for the industry’s growth in the past year.

On the whole the media were hardly sympathetic, perhaps because Katzenberg has been largely responsible for making 3D–including those 3D-ized films–so profitable. Patrick Goldstein of the Los Angeles Times called his speech a “desperation plea” and gleefully linked to several anti-3D articles, including some of the ones I’ve linked to in this and last week’s entries.

What Katzenberg didn’t point out was that some of the six films in the top ten were the same retrofitted ones that he was attacking: Clash of the Titans and The Last Airbender. Alice in Wonderland was shot in 2D, but planned with the knowledge that it would be converted to 3D. (Gulliver’s Travels had not yet demonstrated that retrofitted 3D doesn’t always make for big domestic BO.)

Yet about a month later, in an interview with the New York Times, the other most influential figure in the push toward 3D, James Cameron, was discussing converting a film released in 1997 and not planned with 3D in mind: Titanic. (He plans to release it for the 100th anniversary of the ship’s 1912 sinking.) For Cameron, conversion is a problem when it is done hastily and carelessly. Of the retrofitting of Clash of the Titans he remarked, “It was just being applied like a layer, purely for profit motive.”

One problem with converting a 2D film to 3D comes from the fact that the process is far from an exact science (or art). Cameron commented on his search for a company to handle Titanic:

These conversions are so painstaking to complete correctly, Mr. Cameron said, because “there’s no magic-wand software solution for this.”

He added: “It really boils down to a human, in the loop, sitting and watching a screen, saying, ‘O.K., this guy is closer than that guy, this table is in front of that chair.’ ”

For his 3-D “Titanic” rerelease, Mr. Cameron said he had approached seven companies about working on the film, testing each by asking it to convert about a minute of movie footage before he chose the best two or three efforts.

“All seven of the vendors came back with a different idea of where they thought things were, spatially,” he said. “So it’s very subjective.”

He also points out that studios will inevitably search their vaults for films to convert.

How does 3D conversion work? An invaluable issue of Screen International, “European 3D Special 2010,” explains in terms reasonably comprehensible to the lay person:

While each company goes about it slightly differently, the requirements are broadly the same: the creation of a second identical version (to obtain a second eye view) and the isolation of foreground from background elements by rotoscoping, adding depth and then painting or animating in the gaps. “When you move an image in this way to create two views, the biggest problem is filling in and cleaning up the area left behind,” says Vision3 post-production supervisor Angus Cameron. (From “Conversion: 2D to 3D,” p. 9)

(This issue, by the way, shows that studios doing conversion are popping up in Europe as well as in the U.S.)

As Cameron’s statements and this description suggest, the process is a painstaking, lengthy one. Many in the industry praised Warner Bros.’ decision not to release Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows Part l in a 3D conversion. The studio cited insufficient time before the release date as its reason. Cameron remarked, “You can’t do conversion as part of a postproduction process on a big movie, because no one is willing to insert the two or three or four months necessary to do it well.” (Of course, some foes of 3D may have suspected that the real reason for Deathly Hallows I being released only in 2D may have been that WB saw the declining share of the box office going to 3D and decided it just wasn’t worth it.)

Graham Clark, the head of stereography for the Stereo D company, claims that the conversion process can be done well as long as enough time is allotted for it:

“The main thing is this is an artistic process,” he said of conversion. “Composing things in 3D space is every bit as artistic as composing things in 2D space.” […]

“Because there are so many factors that go into deciding how to compose a shot, you need interaction with the producer, director, cinematographer—so you are not, at the eleventh hour changing things,” he said. “Also, visual effects studios are used to handing off [VFX elements] at the eleventh hour. Conversion is new in the film pipeline, and people aren’t used to having to hand stuff off earlier.”

Clark points out some of the ways that conversion could be used to enhance a film. If a 3D camera can’t be fitted into a certain space, a shot can be done in 2D and converted. If after a scene is shot the filmmakers want to shift the spatial relations of elements within it, they can do so—eventually, at any rate, since the techniques for doing that are still being developed. As Clark points out, films shot in 3D usually have some shots that are converted. Even Avatar included some. (See Carolyn Giardina’s “The art of the 3D conversion,” The Hollywood Reporter, October 29, 2010, pp. 6, 87. The same article, retitled “Expert: The Biggest Challenge in 3D Conversion,” is available here for subscribers.)

Given that most effects-heavy films these days face a major crunch to make their release dates and have to employ multiple effects houses to do the job, a quality 3D conversion can only add to the headache. Not to mention more work for the conscientious director and cinematographer who have to sit in on the decision-making to prevent the quality of their work from being diminished.

All in all, it looks as though 3D will not die out completely. But will there come a time when every screen in the world’s major markets will have the capacity to show 3D films? That was Katzenberg and Cameron’s original ideal, or so they said. Others had the same vision. Katzenberg has committed Dreamworks Animation to making only 3D films. Does he plan eventually to eliminate 2D prints altogether? Cameron claimed he would do that with Avatar, but he had to give in on that one.

Maybe Katzenberg and Cameron would object that they didn’t mean that literally every screen would be 3D. Yet advocates for 3D often compare it to sound or color or widescreen, all processes which did fully penetrate theatrical exhibition. In major markets sound took about three years (though places like Japan and Russia still made a few silent films into the mid-1930s). Widescreen took about six years. The most apt comparison is perhaps color, which didn’t become really viable until the mid-1930s; it remained somewhat rare into the 1940s and didn’t really become dominant until the late 1960s. But in our era of fast-moving technology, perhaps three decades from now 3D, at least in its current form, requiring glasses, will be a dead technology.

In my first entry on 3D, I mentioned that not very many producers or directors have been proselytizing for the process nearly as much as Katzenberg and Cameron have. Lucas is converting the Star Wars series, but he doesn’t promote the process with the fervor he once devoted to digital cinematography and projection and Dolby sound. Spielberg’s first 3D film, The Adventures of Tintin: The Secret of the Unicorn, is coming out in December, but he’s not making the round of the trade fairs singing the praises of the process. The same is true of Scorsese and his 3D debut, Hugo Cabret, also coming in December.

Peter Jackson and Guillermo del Toro had originally stated that The Hobbit would be 2D, so as to keep a unified look alongside the Lord of the Rings trilogy. But when Warner Bros. finally greenlit the film in October of last year, the press release included the news that the two parts will be shot in 3D. Peter Jackson is a big booster of the Red brand digital cameras (used on The Lovely Bones and District 9), and he enthused briefly in the Red press release about using the new Epic 3D model for The Hobbit. His Weta Digital facility did most of the effects for Avatar. Still, he’s not out on the stump, urging theaters to convert and warning filmmakers not to retrofit their films, and many fans wonder whether Warner Bros. left him any choice in the matter of using 3D. (Vague statements have been made about the trilogy being released in 3D eventually, but there’s no firm news about that.)

Of course, assuming 3D is here to stay, there will always be bad conversions because there are bad instances of anything. There are shoddy-looking 2D movies and always have been. Still, the studios didn’t charge extra for them. There are and will be movies originally shot in 3D that are bad. People will have to pay extra for them, too, at least in the near future. Somehow, paying that premium 3D price seems to make people more indignant about bad movies than paying the regular price does. Studios are not likely to heed Katzenberg’s plea that they not crank out cheap 3D-izations. If such sloppy jobs as Clash of the Titans continue to come out and sour people on paying premiums, the studios may have to lower those premiums until they just cover the extra costs of production and of the glasses. If 3D ceases to generate any significant extra profit, will the studios bother with it?

Or will they take the more sensible approach that I mentioned at the beginning of the first part of this entry, settling for multiplexes converting two or three screens for 3D capacity and showing either special-event films like Avatar or cheap genre films like Piranha 3D? Part of that approach would include continuing to make 2D prints of films. There are quite a few viewers who would prefer that option.

At least one studio chief agrees. Last summer Home Media Magazine‘s article on Toy Story 3 reported: “Disney CEO Bob Iger, in a recent financial call, cautioned flooding the market in 3D releases, opting instead that earmarked titles in the format should be done strategically, and not as an afterthought.”

Before moving on to vociferous 3D opponents, I’ll mention a couple of intriguing, possibly significant things that I’ve noticed that may indicate a short life (or possibly a marginalized long life) for 3D.

First, on January 10, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences announced its scientific and technical awards. (Those are the ones that are given out at a separate ceremony and are given a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it acknowledgment during the Oscar ceremony.) These awards are often given for developments that occurred years earlier. On the other hand, major innovations tend to get honored fairly soon. The two technical awards given for special-effects programs for The Lord of the Rings were given in 2004, the same year that The Return of the King swept the Oscars.

This year’s awards include none relating to 3D. (For Variety subscribers, the complete list is here; so far they don’t seem to be listed on the Academy’s website.) Instead, they relate to such inventions as a new winch for flying heavy props like cars, a new suspended-camera mount, systems for queuing special effects for rendering, a method for facial-expression capture, and an innovative way of using bounce lighting in computer animation. Maybe it’s not significant, but it may give a clue as to the professional motion-picture technicians’ view of 3D.

Second, this past summer David and I were able to attend a trade demonstration at a local theater. The Technicolor firm had innovated a 3D add-on lens for 35mm projectors. Technicolor had seven Hollywood studios signed on, agreeing to provide analog 3D prints formatted in the system. (13 of the 19 films released in 3D in 2010, beginning with How to Train Your Dragon, were available on 35mm 3D prints.) The main appeal of the system was that distributors don’t buy it; they rent it by the year. The special silver screen needed for the technology would cost around $4000 to $6000 to install (and could be used for some digital 3D systems, including RealD), and the lens would be rented at $2000 per 3D film exhibited, with a maximum of $12,000 per year. In contrast, a digital 3D conversion costs at least $75,000 per house.

Some small-town exhibitors from the surrounding area were obviously intrigued. They couldn’t afford to convert to digital/3D, but this offered a cheaper option. Nobody mentioned it during the demo, but the other obvious implication seemed to be, if you just rent your equipment, you won’t lose out if the 3D craze fizzles out. The firm anticipated having over 500 systems installed in the U.S. by the end of 2010. (For a case of a theater in Decatur, Illinois that canceled its deal with Technicolor, see here; the management failed to understand that one has to charge higher admission for 3D tickets because the print rental fees and 3D system cost more, and the projectionist keeps referring to the 3D lens as a “camera.” On the whole, one can’t feel that in this case the Technicolor system itself was to blame. The 25 equipped screens out of the 150 in the Bow Tie Cinemas chain in California presumably have fared better.)

[Added later the same day: Skip Huston, who run Huston’s Avon Theater 3 in Decatur, tells me that the reporter was the one who called the lens a “camera.” (Knowing what it is to be misquoted by a reporter, I can well believe it.) The owners tried to avoid raising ticket prices for their customers, but that just doesn’t work with 3D. Mr. Huston’s theater is a mom-and-pop establishment competing with two Carmike multiplexes. Those wishing to avoid 3D have the option of 100% 2D at the Avon.]

Naysayers galore

The more I see of the process, the more I think of it as a way to charge extra for a dim picture.

Roger’s remark sums up the two beefs people have with 3D. Not surprisingly, when 3D was a novelty and only major films had it, people were willing to pay extra. Now that any multiplex will be likely to have one or two screens devoted to 3D movies at any given time, the premium has begun to seem onerous. And yes, the glasses do cut out a noticeable part of the light coming from the screen.

According to a report by PricewaterhouseCoopers (quoted in The Hollywood Reporter), “a $5 premium per ticket is too much to expect audiences to pay for 3D. That survey indicated that 77% of Americans will not pay a premium of more than $4.” In terms of the industry’s attitude, the report adds, “Many people are over-excited by it. The danger is that industry players risk killing a golden goose by overselling and, in some cases,  overpricing the 3D experience—and by providing too much mediocre content that doesn’t do justice to the technology.”

overpricing the 3D experience—and by providing too much mediocre content that doesn’t do justice to the technology.”

Putting aside the high price, there are those who actively dislike the process. Others admit that there are a few films that justify the use of 3D but that most films using the process released so far have been attempts on the parts of the studio to jack up the ticket prices. If these people are entertainment journalists, they use the forum of their reviews or columns to air their complaints. If they are ticket-buying audience members, they search out the 2D screens or stay home. Some of them blog about their complaints, others write letters to the editor, and others carp about 3D around the water cooler.

Roger Ebert probably has the highest profile of the anti-3D naysayers, as least among the general public. In an article in Newsweek (May 10), he laid out his objections:

3-D is a waste of a perfectly good dimension. Hollywood’s current crazy stampede toward it is suicidal. It adds nothing essential to the moviegoing experience. For some, it is an annoying distraction. For others, it creates nausea and headaches. It is driven largely to sell expensive projection equipment and add a $5 to $7.50 surcharge on already expensive movie tickets. Its image is noticeably darker than standard 2-D. It is unsuitable for grown-up films of any seriousness. It limits the freedom of directors to make films as they choose. For moviegoers in the PG-13 and R ranges, it only rarely provides an experience worth paying a premium for.

Roger goes through each of these reasons in more detail. He writes with conviction, and the studios would be wrong to think that he stands alone. I wonder how many other websites have linked to the online version of the essay. I see it quoted and linked a lot, even eight months after it appeared.

Movie City News critic David Poland, also far from being a fan of 3-D, recently posted an entry called “Will 2011 Be A 3D Car Wreck?” He assesses many of the roughly 30 3D films announced for this year. As he points out, similar films will be competing with each other during the key release seasons, as with Scorsese’s Hugo Cabret, the third in the “Chipmunks” franchise, and Spielberg’s Tintin movie, which are coming out within a short period. He concludes:

But the problem remains… 3D is a tool, not an answer. The problem that I expect next December, for instance, will be a parade of high quality films of a similar tone all piled up in on month. Same with the load of animation in November. And whichever films pay the price – and some films will – it won’t be 3D’s fault, but rather, overloading the marketplace. The franchises are franchises and the product that isn’t franchise will need to be sold smartly and heavily… just as in a world without any 3D at all.

This is an interesting variant on the view of 3D as a symptom of the film industry’s problems. Often popular commentaries link 3D mainly to the loss of audiences to TV, video games, and other new media sources of entertainment. But Poland sees the problem as more related to the increasing dependence on franchises and big event films. When other methods of luring patrons into theaters fails (Johnny Depp and Angelina Jolie together for the first time!), 3D remains a lure–except when it doesn’t, as with Gulliver’s Travels.

These days Entertainment Weekly seems to be mounting a campaign against 3D. Lisa Schwarzbaum makes no bones about her increasing disenchantment with the format. About a quarter of the prose in her December 15 review of The Chronicles of Narnia:Voyage of the Dawn Treader (C rating) is devoted to it:

And that includes the option of watching The Voyage of the Dawn Treader in undistinguished, unnecessary 3-D. I’m more and more frustrated these days by movies that sell the 3-D movie experience as a kind of turbo-charged event, yet the greatest extra we see through plastic movie-theater goggles is the ”dimensionality” of a sword or a boot or the imaginary fur on a CGI  mouse. I’m confounded by the fact that, aside from the Pevensie siblings and their nicely obnoxious cousin, absolutely everything and everyone aboard the Dawn Treader looks one-dimensional, no matter how closely I peer through special specs.

mouse. I’m confounded by the fact that, aside from the Pevensie siblings and their nicely obnoxious cousin, absolutely everything and everyone aboard the Dawn Treader looks one-dimensional, no matter how closely I peer through special specs.

It’s not just that one film, either. Schwarzbaum called Tangled (B rating) “Disney’s new (yet not quite novel), musical (yet not quite memorable), 3-D (yet so what) animated retelling of the Grimm brothers’ Rapunzel.” Of The Green Hornet (C-), she remarked, “In a last-minute tweak, the production has also been meaninglessly 3-d-ified–never mind that there’s nothing whatsoever 3-D-ish going on. Maybe those clumsy 3-D glasses are meant to let moviegoers mimic the superhero mask-wearing experience? At any rate, they let moviegoers pay more for a ticket.”

OK, she’s one critic. But note EW‘s back-page “Bullseye,” which shows what one or more people on the staff think of as recent hits and misses in the sphere of popular culture. For the week of November 11, , there was an arrow fairly close to the center with the caption: “Good news for 2012: Batman gets a title (The Dark Knight Rises). Better news for 2012: He won’t be rising in 3-D.” For the year-end Bullseye from the undated last issue of 2010, an arrow on the outer rim had a distinctly unsympathetic caption (see above). The January 21 issue places an arrow near the outer ring, labeled “All that talk of making The Great Gatsby in 3-D.”

Lest anyone think that EW has some hidden agenda in knocking 3D, we should note that the magazine belongs to Time Warner, whose Warner Bros. studio is deeply invested in the success of the format.

There’s also a great deal of anecdotal material about how parents are tired of paying multiple 3D surcharges when taking a whole family—and tired of finding that the kids won’t wear the glasses through the whole show. Dorothy Pomerantz is one parent with a soapbox from which to state her case, in the form of her “The Biz Blog” for Forbes. On July 13 she wrote:

We went to an 11 a.m. showing (for matinee prices) of Despicable Me and it cost us $41 for a family of four. If we had decided to see the film in 3-D, it would have cost us $55 for tickets alone. In my mind, that’s too much money.

For one thing, my kids are scared of the 3-D effects and wiggle so much in their seats it’s hard to tell if they’re seeing the image clearly at all (and my daughter has a very hard time wearing the glasses over her normal glasses for 90 minutes at a time). I find the glasses sit very uncomfortably on my face and that the movie image is often dim. For some reason my husband doesn’t see the 3-D well and ends up with a horrible headache.

People seem to think that children’s animation is ideal for 3D—but if a lot of young children don’t like the glasses or can’t keep them on, maybe that’s not true. (The image above right is not a warning against such problems but a promotional item for watching 3D Blu-ray on PlayStation 3. Apparently children will be seen and be heard.)

Apart from journalists, ticket-buyers are complaining. Back to EW, where the January 14 edition’s letters page (p. 10) had this from Courtney Holcomb of Grand Prairie, Texas:

I’ve read many articles discussing the trend that Avatar started … yet most of them miss a simple point. The film was available in both 3-D and standard formats. The customer had to decide “Do I want to see it in 3-D or not?” More recent 3-D movies have changed the question to “Is it worth it to see the movie in 3-D?” Many of the ones on the “Bad!” end of your “Ranking 3-D Movies” chart might have done better if the standard version had been available as well.

Actually the chart (see left) was by quality, not income, but Ms Holcomb’s point could apply to box-office hits and disasters alike. People who had no access to 2D versions of any film on the list might have decided to go. A friend of mine told me he didn’t see The Voyage of the Dawn Treader, despite wanting to, because it was only showing in 3D.

On the same letters page, Stephen Wohlleb of Sayville, New York, wrote:

While studio execs scurry to push out any film they can in 3-D, they must keep in mind that 3-D should be used to enhance the story, not replace it. The “other Avatar,” The Last Airbender, was so poorly received because story still comes first; 3-D does not a film make.

I have not ventured too far into the depths of chat rooms and comments on the internet for the purpose of writing this blog, but of course, there one can find vociferous pro and con statements on 3D.

I have a friend with vision problems and frequent headaches, and she actually finds the 3D glasses improve her viewing of films. That doesn’t seem to be common, though. Mostly the headaches and the kids-having-trouble-with-glasses complaints seem to be shared by many.

Industry commentators don’t seem to mention the novelty effect of 3D much any more. Surely they never really thought that audiences will be dazzled forever. I think we reached the ho-hum point some time last year. I’ve mentioned that people began to resent the $3+ price hikes and to pick and choose more carefully among 3D releases, wanting the movie to be good enough to warrant paying more. But others perhaps decided 3D in general wasn’t worth it and that they would rather see a film the old fashioned way, seeing a flat image undimmed by glasses.

For me it was Toy Story 3. In 2009, David and I saw Up in 3D and enjoyed it. But we enjoyed it because it was another great Pixar film. As I said in my 2009 entry, I have remembered the film in 2D. We went to Toy Story 3 in 2D and enjoyed it. I have yet to see a film in both 3D and 2D to make a comparison, but my suspicion is that I would usually prefer the 2D version. I suppose the basic problem is that if the 3D is used for flashy depth effects with things flying out at the audience, it becomes too distracting and obtrusive. But if it’s used simply to make, say, jungle plants look closer to the viewer than Carl and Russell, then it’s unobtrusive—and hence not very interesting. Given that we have other mental tools besides binocular vision for grasping the spatial relations in an image, the jungle plants look closer in 2D as well.

A final thought on disaffected audiences. Currently there is a sector of the moviegoing public that loves 3D, will pay extra to see almost anything in 3D, and hopes the process expands. That part of the public is probably as big as it’s going to get. (Yes, new kids will grow up, but others will mature out of their adolescent obsessions with such things.) In the U.S. at any rate, right now there aren’t a lot of people suddenly discovering the joys of this wonderful new format. (It’s really just getting going in the major Asian markets.) But the proportion of the getting fed up by the process’ drawbacks—its higher cost, the growing numbers of mediocre and bad films in 3D, the glasses—is probably growing.

Just in time for inclusion in this entry, Roger has posted a new article, “Why 3D doesn’t work and never will. Case closed.” It includes a letter from Walter Murch, who is about as well-respected an expert on film technology as you could find. The letter explains how 3D systems work in ways that are contrary to the ways that our eyes and brains actually function. He deals with strobing, the convergence/focus issue (“So 3D films require us to focus at one distance and converge at another.” That’s where people’s headaches come from in watching 3D movies.) Murch concludes: “So: dark, small, stroby, headache inducing, alienating. And expensive. The question is: how long will it take people to realize and get fed up?”

Perhaps not very long. I was expecting that in the wake of last week’s post I would receive indignant email and get flamed on message boards. So far I have seen no indignation. One thread on imdb that linked to the entry led to about ten comments, all expressing dislike of or indifference to 3D. Of course, that entry was on the “advantages of 3D” (such as they are) for the industry. Maybe this one will rouse more ire.

A 3D film even a naysayer can love

There’s one 3D film that even 3D disparagers eagerly want to see: Werner Herzog’s Cave of Forgotten Dreams. It’s the one where Herzog got exclusive access to film in the Chauvet cave, which contains one of the largest and oldest sets of prehistoric paintings. I would love to see the cave, but it isn’t open to the public. So naturally I would love to see Herzog’s film. (He’s not exactly a bad filmmaker, either, whatever the topic). It seems the perfect use for 3D: showing people exciting places they will never get to see on their own. I could imagine a similar film being made in the tomb of Sety I in the Valley of the Kings, a very deep tomb full of paintings considered among the best that survive from ancient Egypt. It will almost certainly never be open to the public either.

IFC acquired the film at the Toronto International Film Festival in September. They don’t seem to be trying to publicize it very much. No announcement on their site of when it’s going to be released, and the Google link to the official trailer comes up with a “Page not found.” I had to go to The Documentary Blog to find out that the release date is March 25, but the author had no information about how many theaters would get it in 3D. I should think IFC would make more of a big deal about this film as a real “event” movie. Maybe they will, closer to the release date. With operas and sporting events playing in multiplexes, I would think that there’s a considerable audience for 3D films that bring special events to a far-flung audience. Every kid whose imagine was kindled by learning about prehistoric cave paintings in school, every art lover, plus every cinephile, would attend Cave of Forgotten Dreams if it came to a theater near them.

Has 3D Already Failed? The sequel, part one: RealDlighted

Kristin here–

On August 28, 2009, I posted an entry called “Has 3-D Already Failed?” As I wrote then, my title was deliberately provocative. It depended on which of two yardsticks you measured success by:

1. If you’re Jeffrey Katzenberg and want every theater in the world now showing 35mm films to convert to digital 3-D, then the answer is probably yes. That goal is unlikely to be met within the next few decades, by which time the equipment now being installed will almost certainly have been replaced by something else.

2. It also seems possible that the powers that be will decide that 3-D has reached a saturation point, or nearly so. 3-D films are now a regular but very minority product in Hollywood. They justify their existence by bringing in more at the box-office than do 2-D versions of the same films. Maybe the films that wouldn’t really benefit from 3-D, like Julie & Julia, will continue to be made in 2-D. 3-D is an add-on to a digital projector, so theaters can remove it to show 2-D films. Or a multiplex might reserve two or three of its theaters for 3-D and use the rest for traditional screenings.

If the second, more modest goal is the one many Hollywood studios are aiming at, then no, 3-D hasn’t failed. But as for 3-D being the one technology that will “save” the movies from competition from games, iTunes, and TV, I remain skeptical.

So, nearly 17 months later, where do we stand? There has been a considerable increase in the number of screens with 3D projection systems, from 4,400 in May 2010 to 8,770 in early December. That’s out of roughly 38,000. This growth presumably came in response to the huge success of Avatar and Alice in Wonderland. Anne Thompson’s “Year-End Box Office Wrap 2010” quotes Don Harris, Paramount’s executive vice-president of distribution: “There are more screens, so a theater can now handle anywhere from two to three 3-D films at one time.” By year’s end, there were roughly 13,000 3D-equipped screens outside the North American market. The number of 3D films per year has grown from 2 in 2008 to 11 in 2009 to 22 in 2010 to an announced 30+ for this year.

Thompson also points out two other important strengths of 3D films: they sell a lot of tickets abroad, often earning three times as much as in the North American market, and they have led to theatrical income is “again the leading film revenue stream.” Of course, that’s partly due to the drop in DVD sales.

Yet for some the bloom seems to be off the rose. Low-budget exploitation films in 3D, films shot in 2D and converted for 3D release, filmgoer impatience with ticket surcharges and clunky glasses, and a general decline in the novelty value of 3D have all combined to leave its future still in doubt.

Before going more deeply into those problems, though, let’s look at the box-office successes, or apparent successes, of 3D films in 2010.

3D props up the box office

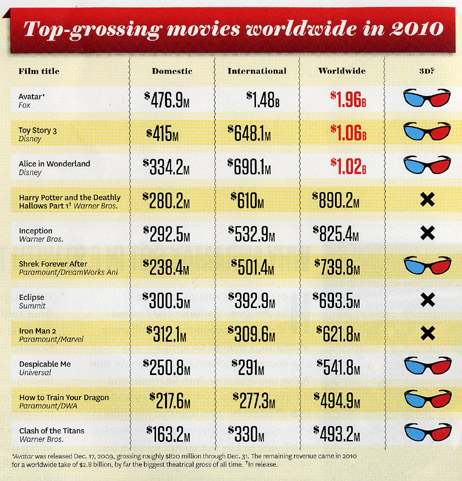

This week’s print version of The Hollywood Reporter heralds 2010 as “The year that was saved by 3D.” (For subscribers, the article is online, though it lacks the charts.) As Pamela McClintock, author of this excellent article, points out, “Of the top 20 films at the domestic box office, 11 were 3D titles (out of a total of 22 major 3D releases). Why the fat grosses? On average, a 3D title can expect to make 30 percent more because of the 30 percent upcharge for a 3D ticket.” (The accompanying chart, below, covers only the top 11 titles.)

(I will step in here and point out something that never seems to get mentioned in coverage of 3D, which is that part of that fee goes to pay for the glasses.)

Moreover, overseas markets, which have been making up an increasing portion of most big films’ worldwide grosses, are adding 3D screens like crazy. “The U.K., China, Russia, Japan, France, Germany, China and Russia in particular have seen a surge in digital-theater installations.” Given that the U.S. is still making more 3D films than most of these countries, Hollywood is getting a generous slice of that box-office income. Some films thought to be disappointments in the States did well worldwide, such as Clash of the Titans, with $493.2 million, and The Last Airbender, with $318.9 million.

Of course, there have been underperformers: Cats and Dogs: the Revenge of Kitty Galore, The Voyage of the Dawn Treader, and Gulliver’s Travels, most notably. McClintock points out, “It’s almost certain that Deathly Hallows would have jumped the $1 billion mark worldwide had it been released in 3D, but Warners didn’t want to tarnish the franchise.” As it is, Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows Part 1 has grossed $937,257,461 worldwide and is still in distribution.

Another thing that McClintock points out that most commentators ignore is that making a film in 3D adds to its budget, on average about $20 million for a two-hour feature. The alternative practice of shooting a film in 2D and then converting it to 3D is common. That costs about $100,000 or more a minute, or about $12 million for a two-hour film. (James Cameron, who ought to know, says a quality job would be $15 million or more.) For a movie that grosses in the hundreds of millions, that’s pretty small, but it’s not insignificant for a more modest film.

Let’s think about that for a moment. Jeffrey Katzenberg and James Cameron may still expect that all films will someday be made in 3D. But, to take one example I’ve seen people use in recent months, do we really think The Kids Are All Right would be enhanced by 3D? Even if some people do, the film cost only around $4 million to make and grossed a little under $30 million worldwide. Would $20 million spent on 3D cause it to gross over $50 million to make up the difference?*

Or does it?

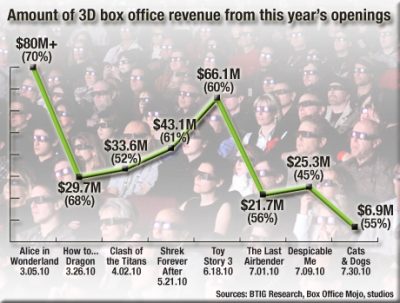

Despite the fact that 3D brought in higher grosses for the more successful films in that format last year, some experts are pointing to a decline in revenues over the year. In July of last year, Daniel Frankel published a widely cited chart called “The Rise & Fall of 3D” on The Wrap showing that since the release of Avatar the previous December, the proportion of the opening weekend box-office for major films coming from 3D screenings had declined:

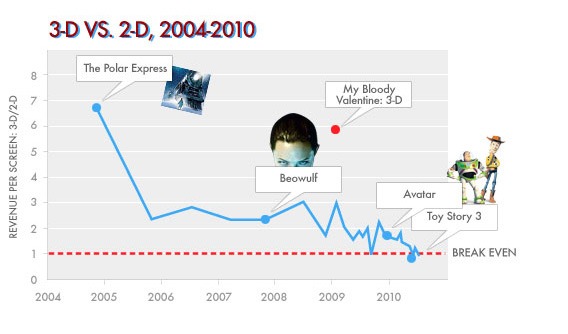

Then in August Slate posted a more detailed study by Daniel Engber bluntly entitled “Is 3-D Dead in the Water?” Engber took issue with Frankel’s chart saying that it did not reflect problems with a shortage of 3D screens available during the release of these films. But Engber didn’t disagree that 3D’s share of a film’s income has been falling. Quite the contrary, he thought it the decline was even greater. Taking a different approach that basically compares per-screen averages for 3D and 2D screening of the same film, he came up with a new chart:

The chart below—created with enormous help from Slate designer Holly Allen—shows the ratio of 3-D revenue to 2-D revenue, on a per-screen basis, for almost every major three-dimensional release going back to the beginning of the current revival.

Here’s the simplest way to interpret this graph: 3-D has been getting less and less profitable, relative to 2-D, over the past five years. It’s an ominous, downward trend that started long before Avatar and Alice in Wonderland and continued after. (The red dotted line represents a break-even point, where screenings in 3-D and 2-D theaters make exactly the same amount of money.)

(I can’t go into the details here, but Engber presents additional charts and information; it’s a must-read for anyone interested in 3D, pro or con.)

Last year the big complaint from Katzenberg and other 3D purveyors was that there weren’t enough theaters to screen all the films that were coming out in that format. Katzenberg is still not satisfied with the rate at which theaters are converting screens to 3D, but maybe exhibitors have realized that there is not as much future in it as they had been led to believe. Given that most multiplexes have two, three, or even four screens capable of showing 3D films, the rate of conversion is likely to slow, if it hasn’t already.

Toy Story 3‘s release seems to have marked the point where some industry analysts began to notice the downward trend in 3D revenues in comparison to 2D. Its opening offers an insight into whether the drop is real or just an apparent effect of too many 3D films vying for too few screens, as is so often claimed. Media financial analyst Richard Greenfield pointed out that the film’s percentage of revenue from 3D screens was 1% less than with Shrek Forever After (released May 21). Toy Story 3 had made 60% of its opening weekend box office on 3D screens, while Shrek Forever After (released May 21) had made 61% and Alice in Wonderland (March 5) had made 70%.

1% may not sound like a lot, but Toy Story 3 was released on the largest number of 3D screens of any film to that date. In that case, it could not be claimed that the drop resulted from too many 3D films jostling for screens. On the contrary, one would expect a rise.

Not only that, but Engber points out that the 2D versions of Toy Story 3 actually outperformed the 3D ones:

Then we come to the weekend of June 18, 2010, when Toy Story 3 opened in more than 4,000 theaters around the country. It was a huge weekend for the Pixar film—one of the biggest of all time, in fact, with more than $110 million in total revenue, and $66 million from 3-D. Yet a close look at the numbers shows something else: On average, Toy Story 3 pulled in $27,000 for every theater showing the movie in 3-D, and $28,000 for every one that showed it flat. In other words, the net effect of showing Woody, Buzz, and friends in full stereo depth was negative 5 percent. The format was losing money.

One could posit, of course, that the 2D screenings simply benefited from the overflow from sold-out 3D screenings. People who wanted to see the film in 3D had to settle. But that still doesn’t explain the drop in comparison to earlier films given the fact that Toy Story 3 opened on the largest number of 3D screens. At least two tickets to the film in 2D were sold to people who had the option of going to a 3D screening: David and me.

Engber goes on to consider some explanations for the decline, some of the same basic ones I’ll discuss here. He concludes that the situation is dire for 3D: “For mainstream movies that can be viewed in either format, the added benefit of screening in three dimensions is trending toward zero.”

Is 3D TV competing with theatrical or hurting it?

There seems to be an assumption that pop culture is headed toward a time when new media in general are delivered in 3D. The assumption is that 3D television will help boost sales of movies on DVD and Blu-ray. Maybe, but the sales of 3D TVs have been reported as lower than expected. According to a revealing article in Variety, Samsung projected that it would sell 3 million units in 2010 and sold less than 2 million: “According to several electronics makers, the biz will be concerned if the negativity continues six months from now.” Screen Digest’s year-end summary of 3D TV’s prospects (“After one year of 3D in the home,” December 2010 issue) points out that not only do 3D sets cost half again as much as 2D ones, but they are also mostly 44” or over, larger than most people can afford even in 2D sets.

That’s not the only cost holding back sales of sets. According to Variety: “The main reasons for holding out have been the pricey pairs of active-shutter glasses (sold for around $150 or more) that can be cumbersome to wear, easy to break and require batteries that run out. At the same time, there hasn’t been much 3D content to watch on the new sets.”

Sets with these active-shutter glasses come with one pair included. The things are bulky and require batteries. New 3D TV models are in the pipeline, some that work with lighter polarized glasses costing more like $20, with  four pairs included. As Bob Mayson president of consumer electronics for RealD (a major 3D theatrical supplier) told Variety, “You won’t have a Super Bowl party with active eyewear. With passive eyewear [i.e, those polarized glasses] you can buy a bag of glasses from Costco and be in business.”

four pairs included. As Bob Mayson president of consumer electronics for RealD (a major 3D theatrical supplier) told Variety, “You won’t have a Super Bowl party with active eyewear. With passive eyewear [i.e, those polarized glasses] you can buy a bag of glasses from Costco and be in business.”

Maybe guys who sit around drinking beer and watching the Super Bowl will get used to seeing each other wearing plastic glasses. Still, I have long been of the opinion that until 3D technology reaches a point where the glasses are unnecessary, the format can’t be universally viable. Toshiba and Sony have prototypes of such sets at technology fairs, but they reportedly won’t reach consumers for three to five years. I’m curious to know what the 3D effect will look like if you’re not sitting at exactly the right spot in front of the screen. From what I’ve read, you have to be positioned not only in front but also close. An excellent article in Wired summing up the obstacles to watching 3D on TV says the depth effect is limited to about four feet. In fact, there already are monitors for 3D without glasses (mainly available in Japan); they’re used mainly to display ads in stores. But in October Toshiba showed off two models intended for the home (left). The monitors are 12″ and 20″ and the optimum viewing distance is 90 cm for the larger monitor; that’s about three feet. They can project 3D to nine points in the room, but it sounds downright impossible for that many people to perch at precise points, all about a yard from the screen. Bigger versions will no doubt follow.

More content is coming for 3D TV, but again according to Variety, many content-providers are

focused on high-profile fare like sports and concerts, because as long as 3D TV requires glasses, it will only be used for event programming, not casual viewing. It may be tough to broadcast the Super Bowl in full 3D, outside of relying on a conversion, however, given that too many seats in the stadium would have to be removed for the 3D cameras. Networks could use robotic and remote-controlled 3D cameras but those are still too new of technologies to rely on yet.

Screen Digest ‘s year-end summary of 3D TV focuses on other obstacles, primarily the lack of content:

As recently as early September 2010 two thirds of the 21 3D BD [Blu-ray Disc] titles confirmed for US release in 2010 were tired to exclusive bundling deals with 3D hardware, leaving only seven available for purchase in store. By November, the total 3D BD slate had increased to 37 titles, 25 of which had been confirmed for retail sale by the year end. Furthermore, many of the biggest titles (including Avatar, the Shrek franchise, Monsters v Aliens, Ice Age 3) were still tied into exclusive bundles. By comparison, at the end of Blu-ray’s first year of availability (2006) 135 titles had been released on the format in the U.S.

I’m sure the brand partnerships between the TV makers and the studios have saved a lot in advertising, but it’s hard to imagine investing in a new technology when every time you want a popular film title, you have to buy a TV set to go with it. No doubt the availability of films to buy will increase, but the introductory approach seems a strange way to go about fostering interest in 3D movies on TV.

The Screen Digest article makes another interesting point. Initially, “3D in the home was conceived first and foremost as an attempt to mirror the revenues proven in the cinema—a 20 per cent premium over 2D features.” But much 3D TV content is also surprisingly like 2D TV content: “Ten percent of the cinema features have been dance or music, with a further four per cent including live sports and opera. This suggests an appetite for content that has traditionally been better suited to live television transmission than physical or cinematic tradition.” That further suggests that in the long run, people may be keener on 3D TV than on theatrical films in 3D—just the opposite of the studios’ hopes as they went in for 3D.

Beyond film and TV content, there is also the likelihood that 3D video-game playing through the large monitor will take up some of the time spent in front of the appliance. There’s also the fact that streaming or downloading 3D films requires far more bandwidth than 2D movies, though methods of compression are being developed.

The Screen Digest author predicts that by the end of 2014, 25% of American homes will have 3D TV. The question remains: What will people be watching?

Next week: Part two: RealDsgusted

*No doubt some cost-cutting is possible. Still, Tsui Hark’s Flying Swords of Dragon Inn (announced for a 2011 release), shot with the relatively inexpensive Red 3D digital camera, is budgeted at approximately $35 million. The difference between that and his usual cost per film could easily include $15-20 million for 3D. See Filmsmash for information and numerous photos derived from Chinese sites; the latter include images of the camera and of shooting in front of a green screen.

By Sam Spratt at Gizmodo

Bond vs. Chan: Jackie shows how it’s done

DB here:

During the 1990s several critics began to notice that filmmakers were doing something odd with action scenes.

Directors were consciously, even joyously, sacrificing clarity. When two characters were punching it out, the framing didn’t make it easy to know who was hitting whom, and how. Changes in angle and shot scale were sometimes so abrupt that you had little time to adjust. The cutting pace was so quick that you couldn’t entirely register the movement in shot A before shot B replaced it. Sometimes the spatial layout of the fight was confusing as well: too many close views, too few master shots. Later, the return of handheld shooting made many action scenes even more illegible, blurring and smearing them to the point that sound (as in the Bourne films) had to specify that a body has hit a window or a hand has busted a bottle. Now we have Sylvester Stallone’s The Expendables, which might be a new summit in overbusy, incoherent, inconsequential action.

I wrote about this trend back in the 1990s, and I’ve returned to it on occasion since. Other writers, notably Todd McCarthy of Variety, noticed it too. He referred to the full-throttle editing and “frequently incoherent staging” on display in Armageddon (1998): “Bay’s visual presentation is so frantic and chaotic that one often can’t tell which ship or characters are being shown, or where things are in relation to one another.”

A decade later comes Peter DeBruge’s review of the “muddled execution” of The Expendables: Staging simultaneous fights “might’ve worked had the editors assembled all that footage in such a way that we could tell where characters are in relation to one another or what’s going on.”

The Michael Bay approach has become the principal way in which action scenes are shot. It isn’t absence of craft that leads to these aimless bouts. The filmmakers actively want the action to be hard, even impossible, to follow. Sometimes I think that this blurred bustle is there to secure a PG-13 rating; if you could really see the mayhem, we might be moving toward an R. But filmmakers don’t say that they’re self-censoring. They seem to think that making the action illegible is creative because it promotes realism.

Stallone explains why he scrambled up the fight scenes in The Expendables.

I don’t think many action scenes are shown from the character’s point of view. They are more from the director’s point of view. On Rambo, I thought the most economical and original way to shoot [the action] would be through Rambo’s eyes—if he were directing, what would his style be? But The Expendables is an ensemble picture, so it’s somewhat of a blend. I thought, ‘This is not supposed to hang in the Louvre.’ I wanted it to be disjointed and rough, not choreographed. If you really were filming a big battle with five cameras, [their footage] would not all flow together, so we set up the [cameras] to film the action we’d scripted and told the operators they were on their own. We said, ‘Do the best you can, and we’ll use the interesting shots from the characters’ perspectives.’”

Camera operator Vern Nobles describes shooting the action as “multi-camera craziness.”

You might point out that if somebody were really filming a big fight with five cameras, at least a couple of camera operators would be shot or punched silly. And presumably a few times we’d actually see other cameras.

Realism, as usual, is simply a fig leaf for doing what you want. Virtually any technique can be justified as realistic according to some conception of what’s important in the scene. If you shoot the action cogently, with all the moves evident, that’s realistic because it shows you what’s “really” happening. If you shoot it awkwardly, that presentation is “realistically” reflecting what a participant perceives or feels. If you shoot it as “chaos” (another description that Nobles applies to the Expendables action scenes)—well, action feels chaotic when you’re in it, right?

Forget the realist alibi. What do you want your sequence to do to the viewer? Do you want it to pass along an impression of bustle and flurry? Or do you want to make the viewer wince, recoil, even mildly reenact the movements of the players? Then follow the Hong Kong tradition. Yuen Woo-ping once told me that his goal was to make the viewer “feel the blow.” To convey the effort and strain, the impact and pain: that’s something worth doing.

It’s something that the blur-o-vision tussles lack, but even fights that are more carefully filmed are strangely unmoving. In Tomorrow Never Dies (1997), there’s a fistfight on a catwalk above a rotary press line. The presentation is more or less spatially unified, but it lacks drive because of certain creative choices. For instance, when Bond punches a security guard, the man simply drops out of the frame.

Where does he go? He doesn’t fall off the catwalk but seems to grab the railing, so maybe he’ll return for another go-round. But he doesn’t. As Bond falls back, another guard sneaks up on him. The framing and screen direction suggest that he’s approaching Bond from the front.

Actually, he’s sneaking up from the rear.

When Bond turns, we don’t see his punch.

In fact, we don’t see much of anything. Although the attacker is erect in one shot, he seems to be kneeling in the next, when Bond kicks him, somewhere below the frameline.

The attacker is standing again in the next shot, and he’s flung backward by the force of Bond’s unseen kick.

When the man returns, he tries to tackle Bond. At least, I think he does. The maneuver takes place, again, underneath the frameline.

At last we get a wider shot, but this serves mainly to align the fight with the conveyor belt below the men; guess who will fall?

More fighting, with punches and grappling blocked by the men’s bodies, culminates in Bond’s adversary falling into the print run.

Even here, however, we don’t really see what happens to the victim. He plunges through the river of newsprint and the machine starts belching.

Overall, we get a mild impression of what happened in the fight, but the action unfolds vaguely and is hardly stirring. Is this how you earn a PG-13?

The Hong Kong way

Righting Wrongs (1986).

While revising Planet Hong Kong for its web edition, I’ve been revisiting classic Hong Kong action scenes. In 1997-98, when the book was written, I had to rely on laserdiscs, but since then I’ve been able to look at more 35mm prints. (DVDs usually don’t help answer the sort of questions I’m asking, for reasons reviewed here.) Now I have a chance to put some thoughts about these movies online, in this blog and in the upcoming digital update of the book. As a start, here’s a recipe drawn from the best of Hong Kong fury.

First, go for clarity in every way. Not murky earth-toned sets but brightly colored and sharply lit ones; even an alley can dazzle. Put the camera on a tripod; pan if you must, but save your dolly moves for simple emphasis. No handheld.

Second, aim for precision. Stallone’s comments imply that a cameraman captures a preexisting fight, snatching an “interesting” shot here or there. But that’s not the case. Movie action is choreographed and the framing is calibrated to that. The gestures should be legible, favoring crisp and staccato movement, while the image’s composition aims to convey the action cleanly. It’s a pity that the haphazard framing of Stallone and his cameramen have ruined the choreography of Cory Yuen Kwai, Jet Li’s action designer (and a fine director in his own right).

Third, establish a rhythm. This involves not only building the fight. It also involves synchronizing the pace of characters’ movements with that of the cutting. On the whole, the old rule applies: More distant shots should be held longer than closer ones. This doesn’t mean you can’t use fast cutting, only that your fast cutting can be more finely judged when you take shot scale, composition, and speed of movement into account.

Rhythm means sensing a pulse, and for that you need slight pauses. So don’t cut away to something else before a punch or kick is completed. Let the arc of movement, itself perhaps stretched over several shots, come to a point of rest, if only for a couple of frames.

Fourth—and here is where realism is most explicitly abandoned—amplify the expressive qualities of the action. If movement is zigzag or springy or oscillating, stress that. Give emotional qualities not only to facial expressions but also to postures and combat moves. American heroes just grimace while their bodies remain inexpressive, lumpish. The hard guys in The Expendables might as well be made of granite. But in contrast your fighters needn’t wave their arms wildly. Just concentrate energy and emotion in the action. If the hero attacks, let him become as focused as a javelin. If your heroine falls, don’t let her just drop out of frame: Let her land with a thwack, preferably on the spine or neck, and let her body’s recoil send a spasm through the spectator too.

Hong Kong cinema supports Sergei Eisenstein’s belief that expressive human action is “infectious.” He thought that if physical action onscreen is imbued with vivid force it can arouse sympathetic echoes in the spectator’s own body. After a great action scene, such as in many Chang Cheh and Lau Kar-leung films of the 1970s, or in Yuen Kwai’s Righting Wrongs, when a tough guy gets a spittoon in the face, the viewer feels trembling and tired, but in a good way.

Glass story

Jackie Chan has become such a beaming, easygoing star that we forget that he was an excellent director of brutal fight scenes. He proved adept at filling anamorphic compositions with dynamic movement, as well as plucking out items of a set and sweeping them into the action. (See the parlor fight in Young Master, 1980, or the shenanigans in the rope factory in Miracles/ Mr. Canton and Lady Rose, 1989). In Police Story (1985), Jackie is trying to rescue Salina and save all the computer records in her briefcase. Koo’s gang is determined to stop him. The fight moves through different areas of a shopping mall.

In each of these locales, Jackie plays a suite of variations on what you can do with escalators, staircases, and, most memorably, glass. I can’t do justice to all the skirmishes, but consider some instances of how he stages and cuts the action for an impact that American movies seldom achieve.

The variations get steadily more elaborate. Early in the sequence, Jackie flings one thug, achingly, across the bottom handrails of an escalator.

The shot could hardly be more legible. You see everything. Next, Jackie is grabbed from the rear.

Naturally he has to flip his attacker down to the floor below, rendered in two dynamic shots from directly below and above.

Interestingly, the shots are so clearly composed (even with the fancy mirror effect in the second) that they can be very brief: 26 frames and 16 frames. Down at the bottom, the unfortunate fellow smashes through a display and lands straight on his spine. Unlike the security guards in Tomorrow Never Dies, this thug gets a little commiseration as he rolls over groaning. As in any fight sequences, disposable thugs may come back into action, but at least we’ll clearly see the fates of those who are put permanently out of commission.

After this burst of action Jackie provides a pause as he abruptly looks up in search of Salina.

What else can you do with escalators? How about tossing the next thug down the slim gap between two of them?

In a nice touch, we hear a long squeak as he slides down the trough.

Tomorrow Never Dies sets up its conveyor-belt climax straightforwardly, but Jackie’s choreography is more surprising. Audacious and imaginative as the stunts are, however, they are framed and cut in a way that makes the action clear and precise. Through cinematic choices Chan builds up an infectious arousal. This stuff hurts.

After a set-to in a hallway, Jackie pursues the gang into an area filled with display cases. He takes on the men ferociously, and sets them smashing through the vitrines in another string of variations. Jackie slams down a mirror on one thug, swings another into a display, and sends one spinning through a window. Each shot, of course, is of diagrammatic simplicity, all the better to amplify the expressive dimension and key up the viewer. You can’t watch shots of men hurled into layers of glass without feeling a few palpitations.

Nearly every shot is bound tightly to the next. What will occupy shot B is launched on the fringes of shot A, sometimes for only a few frames. The string of matches on action creates a fluid continuity quite different from the choppiness we often find in American sequences.

A good instance occurs after Jackie has been pinned under a toppled shelf. In a medium close-up, the gang leader orders his thug into action; behind him the plaid-coated thug moves left.

In long shot, with Jackie at a disadvantage, the thug continues his movement in the background as he grabs a heavy statuette.

In a medium-shot, Mr. Plaid Jacket lifts the statue, but as he moves aside he reveals Salina rushing toward him in the background. Look quick: She appears in the fifteenth frame, and is gone within another fifteen.

We can only glimpse Salina passing behind the thug, but the next shot shows her clearly: running, baseball bat in hand, toward him. The trajectory could not be clearer, and she swings the bat directly through the vitrine.

The force of the action is multiplied by the simplest cut possible: an axial enlargement, with the action slightly repeated and slowed. The first shot of Salina’s swing lasts seventeen frames, the second exactly twice as long. The arithmetic of the cutting extends the action’s beat.

Bursts of glass form the dominant, painful motif of this part of the sequence. (Jackie’s crew suggested he call the film Glass Story.) The shifting dynamic of the fight is rendered through close encounters of the splintery kind. But these are differentiated. Long shots portray the torments of the gang, but Jackie’s first encounter with glass is treated in one simple close shot, just a second long, that usually makes audiences flinch.

Jackie is attacked by the gang leader and he shoves Salina out of the way.

The leader springs forward to whack Jackie with the briefcase.

Cut to the opposite angle, a tight shot of Jackie.

The briefcase continues to be swung, and Jackie’s head smashes the windowpane.

Jackie bounces off the glass and grimaces in agony.

The proximity of the glass shards to his eyes probably triggers some primal revulsion in us, but this is only part of the image’s force. The whole shot lasts only 28 frames. I think that part of its percussive impact comes from the fact that at the start we don’t have time to register that the pane is there. (There are only seven frames before Jackie hits.) When the glass bursts, it’s as startling as if the screen surface has cracked as well, and this amplifies the painful impact of the blow.

For a time Jackie is at the gang’s mercy. But he makes a comeback, and eventually in a kind of summary of his other maneuvers he will bash the leader, body and head, through two glass cases. This phase of the scene concludes with Jackie running Mr. Plaid through a series of cases at the point of a motorcycle. Both crescendos are filmed in clear, smoothly-cut shots—and long shots at that.

We may wince for the fate of these gangsters, but we shuddered when we saw Jackie’s face knocked through a window. Soon Jackie will be flipping the leader down an escalator, a sort of envoi to the scene’s first phase, and he will be sliding down a three-story light pole to catch up with boss Koo himself.

To use Stallone’s comparison, I’d happily hang this splendid sequence in the Louvre.

But what sort of MPAA rating would it receive today? The painful physicality on display is given a staccato force through the framing and cutting. And don’t call it cartoonish. It’s Bond who’s cartoonish, with his unflappable ease and perfectly functioning gadgets and defiance of the laws of gravity and those fights he wins without suffering a scratch. Jackie shows us the sweat. He and his victims fall with painful awkwardness, he gets gashed and bruised, and he’s all too vulnerable to physics (or at least Hong Kong physics). Bond wins through debonair resourcefulness and a lot of luck. Jackie wins by refusing to lose.

He refuses to lose the audience too. In Police Story Jackie’s manic urge to make the scene maximally gripping is itself a little scary. Nonetheless, when a director isn’t afraid of tapping the real power of movies, a fight scene can give us an adrenalin transfusion. Who needs 3-D? Maybe only weak directors.

For other discussions of Hong Kong action scenes, see my “Aesthetics in Action: Kung-Fu, Gunplay, and Cinematic Expression” and “Richness through Imperfection: King Hu and the Glimpse” in Poetics of Cinema. There are some other examples in my online essay on Shaw Brothers. My most ambitious efforts in this direction are in Planet Hong Kong, where I take up the issue of rhythm in more detail than I can here. Alas, many contemporary Hong Kong action scenes have learned bad habits from Hollywood. I’ll talk about the decline of crisp fight staging in the new edition of PHK, due online in early December.

Todd McCarthy’s 1998 review of Armageddon is here. Peter DeBruge’s review of The Expendables is here. Both may lurk behind a paywall. The coverage of The Expendables I mention is Michael Goldman, “War Horses,” American Cinematographer 91, 9 (November 2010), 52-56. The pilot online issue is here.

The Dragon Dynasty version of Police Story includes Bey Logan’s conversation with Brett Ratner. During the commentary, Ratner notes that Jackie holds his shots longer than would an American director, who would be likely to cut on every punch. Incidentally, I’ve found many DD releases of Hong Kong films to be superior in quality to other DVD versions, and Logan’s commentaries are information-packed. His book Hong Kong Action Cinema remains a fine piece of work.

The images from Tomorrow Never Dies are taken from DVD, with all the drawbacks of that format for close analysis. But I don’t think my conclusions would vary if I worked from 35mm. The Police Story frames are analog frame enlargements from a 35mm print and allow accurate frame-by-frame analysis. Even then, Jackie’s pacing is so fast that blurring is inevitable. Thanks to Heather Heckman for her assistance in turning my slides into digital files.

PS 17 September 2010: I forgot to mention that Matt Zoller Seitz has provided two of the most discerning (and hilarious) critiques of the Michael Bay High Rococo Action Style, here and here.

Young Master.

Revisiting INCEPTION

Inception.

Heading cross-country from Chicago in Dad’s old Honda Prelude, we’re no further than Wisconsin on the first day when Jonah turns from the passenger seat and tells me he’s working on something.

Christopher Nolan, on the origins of Memento

We were driving my dad’s old car from Chicago to Los Angeles. It must have been the second day of driving–we were past Minnesota.

Jonathan Nolan, on the origins of Memento

It’s rare when a filmmaker confirms hypotheses put forward by critics. But that seems to have happened to us.

An enormous amount had been written about Inception, both on the internet and in print, before we wrote our blog entry last week. For the most part, we avoided reading about the film, fearing spoilers and statements about the film that might influence our own initial take on it. Since then, we’ve read Jeff Goldsmith’s in-depth interview with Christopher Nolan published in Creative Screenwriting (not yet available online). There Nolan broaches several ideas about his approach to the film, and some of those square with our analysis. Today we highlight a few of those remarks and tease out their implications. We end with comments from some readers.

Exposition rules

Kristin here:

My contribution to last week’s entry concerned the film’s dependence on nearly continuous exposition, which I thought of as a major formal device across the film. In the Creative Screenwriter interview, Nolan says that exposition was a particular concern of his in making the film.

Ten years ago he envisioned the film as a heist caper:

“One of the fascinating things about the heist movie, and one of the reasons I took this as the model, is that the type of exposition that in most films is problematic, boring, tricky, hard to get through—in a heist movie becomes the meat of it,” Nolan says. “It’s part of the entertainment simply because the process of a heist movie and that sort of procedure, the way they put things together, becomes the reason you’re watching the story.”

Usually in a heist film we get a big dose of exposition as the team’s leader explains the plans for the crime to his colleagues. Then we watch the plan unfold, with exposition added well into the film as needed. In Inception, however, the heist explanation becomes nearly continuous. Goldsmith comments, “Nolan smartly flipped this conceit on its head and instead of keeping the audience at a distance, he decided to take them along for the entire ride. The subtle re-configuration allows for the audience and the characters to sweat together whenever any hiccups arise in the well-thought-out plan.” In fact, the “well-thought-plan” unfolds only as we watch the film.

Nolan also comments on this idea of the audience being active, saying that he wanted to involve viewers alongside the characters:

“Exposition is such a massive demand,” he admits.” It’s something you have to just try and imbue in the relationships of the characters. You never want to find yourself in a scene where characters are passively receiving information in some way, because you don’t want the audience passively receiving information. You want them engaged with that dramatization.”

The implication here is that the audience becomes involved in the plot not through learning about the characters’ backgrounds and traits, as most spectators seem to expect in standard Hollywood films—even blockbusters. Instead, our relationships with the characters (apart from Cobb) come through learning new information along with them and being attached so closely to them while they work through the mechanics of the plot.

The result, at least for many viewers, seems to be a feeling of dissatisfaction at not being able to get close to the characters in a more conventional, detailed way. The advantage, if one wishes to consider it as such, is that we are forced into a struggle to understand the workings of the plot.

Yet we are not entirely with the characters in their achievement of the mission, because we move back and forth among the levels of the dream, as none of them does. Thus we may be attached to the characters in the parceling-out of exposition, but we know much more than they do at any given moment once the second dream (the hotel) begins. The result comes through further experimentation on Nolan’s part, this time with intercutting.

Prestigious patterning

The Prestige.

DB here:

In our earlier entry I argued that Inception uses the dream subject matter to set up a heist plot and to motivate a pattern of embedded narratives. Normally, embedded stories are presented as sealed off from one another, like concentric circles. One interest of the film, I thought, lies in the freedom with which Nolan crosscut among these nested tales.

After further reading and re-viewing, I’m forced to ask: Which is the real center of his interest–embedded stories or crosscutting? And this question leads me to think about his development as a filmic storyteller.

In college Nolan studied literature (a good model for aspiring filmmakers, who too often focus only on movies). To this training he attributes his interest in form. “I wrote Memento very much as a puzzle box. I was fascinated by the idea of structure.”

For Nolan, I think, form has centrally to do with the sorts of juxtapositions you can create by crosscutting. You could say he treats crosscutting the way Ophuls treats tracking shots or Dreyer treats stark decor: an initial commitment to a creative choice, which in turn shapes the handling of story, staging, performance and other factors.

Moreover, his fondness for crosscutting favors actions taking place in different time frames. Traditionally, a crosscut sequence switches between lines of action taking place at the same time. While Smith walks his dog, we see Jones stalking Smith’s wife. The Dark Knight has many sequences that crosscut simultaneous lines of action. When crosscutting isn’t presenting simultaneous actions, it’s often alternating between present and past. An influential example is Hiroshima mon amour, in which the female protagonist’s memories of occupied France are juxtaposed with her visit to Hiroshima in the present. Here, as often happens, the switch to an earlier time is motivated as a character-based flashback, an expression of the persistence of her memories.

Nolan’s interest in crosscutting various time frames doesn’t quite square with tradition. He was much influenced by Graham Swift’s 1983 novel Waterland, as he has pointed out over the years. Here is what he says in the CS interview.

“It opened my eyes to something I found absolutely shocking at the time,” Nolan says. “It’s structured with a set of parallel timelines and effortlessly tells a story using history—a contemporary story and various timelines that were close together in time (recent past and less recent past), and it actually cross cuts these timelines with such ease that, by the end, he’s literally sort of leaving sentences unfinished and you’re filling in the gaps.”

What initially intrigued Nolan, it seems to me, is the idea of taking a story that could be told in straightforward chronology and breaking it into two or three discrete phases. He then cuts among scenes within the phases, without motivating the shifts as character-centered flashbacks.

The story of his first feature, Following, could have been told in 1-2-3 order. Instead, within a framing situation of an interrogation, the plot breaks the protagonist’s tale into three phases, all quite close in time, and then cuts among them. Within each phase, the action is chronological (so far as I can see), but the three “eras” are intercut. Nolan is careful to keep us oriented as to which time zone we’re in through things like the protagonist’s appearance (sloppy, well-groomed, bruised) and a burst of black frames that signals a shift to a different zone. Eventually all three phases get linked up, so, for example, the last thing we see of phase one leads smoothly to what we saw as the first imagery of phase two.

The same concern to break up a linear story is at work in Memento. Again, different phases of the same tale are intercut. But now a forward-moving module is accompanied by one moving backward. Again, these are kept distinct through time markers (color footage vs. black-and-white), and the reverse-chronology one is filled with tokens and echoes that remind us that what we’ve already seen actually took place after what we’re seeing now.

The Prestige expands crosscutting in another direction. Christopher Priest’s original novel is based on the discovered-manuscript convention. Adam Worthy, a publisher, begins reading a book by Alfred Borden, Secret Methods of Magic. What follows are several other memoirs, treating events at different points in history, with some going back as far as 1866. These texts are not intercut or even nested. They stand as solid blocks, presenting overlapping time schemes and varying points of view on the central rivalry between the two conjurers Borden and Robert Angier.

For the film of The Prestige Nolan and his screenwriter-brother Jonathan again create a basically linear chronology. Once more it is fractured into discrete phases. There is a present (Cutter showing a bird trick to the little girl Jess), the recent past (Alfred arrested for killing Robert and awaiting trial), a more distant past (Robert visiting Nicolai Tesla in Colorado), and thanks to Alfred’s journal, the most remote days when the two became competitors and Alfred created the Transported Man illusion.

But The Prestige treats its time zones somewhat as if they were embedded stories. I think that this is partly because we have two protagonists and a split point-of-view pattern. The biggest cue, however, is the way that the Nolans absorb the discovered-manuscript convention into the film. In a classic embedded structure, a character recalls or recounts a string of events with its own integrity, and sometimes the frame story involves a character reading a letter or memoir. In the film, this situation is provided by journals kept by the rival magicians. Now Nolan can cut freely among nested stories. At one point we have Alfred, jailed for murder, reading Robert’s journal, in which Robert tells about reading Alfred’s journal in Colorado. Alfred’s version of events is embedded in Robert’s version, which is in turn embedded in the moment of Alfred’s reading in prison.

Moreover, instead of Following‘s rather mechanical demarcation of phases (black frames signal a shift between phases), the narration of The Prestige is quite fluid, joining distant periods through smooth hooks of imagery and sound. Sometimes the sound comes from one period but the shots are in a distant one. We’re introduced to this strategy in the very opening: Cutter’s voice-over is in the present, but the image is two layers into the past.

So it seems to me that in The Prestige Nolan’s interest in crosscutting different timelines became more audacious, working with not only linear events but embedded stories. The interest in nested stories emerges much more explicitly in Inception, as I suggested in the earlier post. But what I didn’t see then was that using dreams to motivate embedded plotlines changes the time game.

A dream within a dream can’t be said to be taking place earlier than the surrounding dream, the way a flashback or discovered manuscript necessarily presents past events. The dream realms can’t be ironed out into a chronological structure as the phased plotlines of Following, Memento, and The Prestige can. In fact we find our old friend simultaneity at work among all the phases (dreaming while dreaming while, etc.). And Nolan’s film invokes the convention of the climactic deadline (actually, four of them). So in a perverse way, Inception‘s formal gambit is more traditional than the time-scrambling of the earlier films. But because we seldom see embedded stories intercut, the result is also pretty daring–something akin to that abstract filmic time that Griffith creates by intercutting four historical epochs in Intolerance.

From this perspective, Inception marks a step forward in Nolan’s exploration of telling a story by crosscutting different time frames. You can even measure the changes quantitatively. Following contains four timelines and intercuts (for the most part) three. Memento intercuts two timelines, but one moves backward. Like Following, The Prestige contains four timelines and intercuts three, but it opens the way toward intercutting embedded stories. The climax of Inception intercuts four embedded timelines, all of them framed by a fifth, the plane trip in the present. For reasons I mentioned in the previous post, it’s possible that Nolan has hit a recursive limit. Any more timelines and most viewers will get lost. What can he do next?

Letters, we get letters (and links)

DB again: