Archive for the 'Readers’ Favorite Entries' Category

Take my film, please

Kristin here–

As I mentioned in our main entry about Ebertfest, Nina Paley’s animated feature, Sita Sings the Blues, was one of the highlights of the festival. Afterward I had the privilege of moderating the onstage discussion with the director and University of Illinois film professor Richard Leskovsky, who has a special interest in animation.

Sita has not had a regular theatrical release, though Nina has made it available to theaters, festivals, and everyone with access to a high-speed internet link-up. She gives it for free to anyone who wants it, believing that people who see it will pass the word along and that as the film becomes more well-known, it will become more valuable as well. Income should flow in. Nina is confident, some might say cocky about this. The thing is, she may be right. Sita is a terrific film, and I can well imagine a ground-swell of interest gradually building. Indeed, it’s happening already. Here I am, blogging about it, and others are as well. Non-bloggers are emailing their friends. Festivals have booked it up to the end of this year and beyond.

Roger Ebert found Sita early on, and his program notes were also his online review, which begins:

I got a DVD in the mail, an animated film titled “Sita Sings the Blues.” It was a version of the epic Indian tale of Ramayana set to the 1920’s jazz vocals of Annette Hanshaw. Uh, huh. I carefully filed it with other movies I will watch when they introduce the 8-day week. Then I was told I must see it.

I began. I was enchanted. I was swept away. I was smiling from one end of the film to the other. It is astonishingly original. It brings together four entirely separate elements and combines them into a great whimsical chord.

The four elements are: a sketchily animated account of the breakup of Nina’s marriage; the tale of Rama and Sita from the Indian epic, the Ramayana; musical numbers that all borrow recordings of Ms Hanshaw; and three shadow-puppet narrators who try, not always successfully, to recall the details of the Ramayana and its background history. As Roger says, somehow all this achieves complete unity.

The timing of the Ebertfest screening was fortuitous. Within the next few weeks, the DVD release is due. Of course, you can already watch it online and/or burn your own DVD. But for those who can’t or don’t want to, you can buy the DVD package, complete with what is described on the film’s website as a predownloaded copy of the film.

As Roger’s review says, Nina is a hometown girl. She started out doing comic strips and then made some  animated shorts before progressing to Sita, her first feature. Her father taught at the University of Illinois. Her mother was an administrator there. Both have supported her in the making and distribution of Sita, and both were present throughout the festival.

animated shorts before progressing to Sita, her first feature. Her father taught at the University of Illinois. Her mother was an administrator there. Both have supported her in the making and distribution of Sita, and both were present throughout the festival.

Here’s a transcript of our conversation (that’s Nina at the far left, Richard, and me). Applause, laughter, and a fast-talking film director at times defeated my efforts to catch every word of my recording, so some details have been lost.

KT: I know you want to talk about how you’ve been getting the film out to the public, but I’d like to start off by talking about the film itself, which is fascinating. I think we can start with the computer animation. A lot of people think that you were pushing a lot of buttons and somehow the computer was generating the images. But obviously you were generating them yourself by painting and collage and so forth. Could you just start with the process of what you did before you put this material into the computer and then what you did afterwards?

NP: Well, there are a whole bunch of different styles and techniques used in the film. The style of the musical numbers, actually I drew that in Flash using a lot of really simple tools, so the perfect circles have a smoothness that you don’t get by hand. By the way, I want to mention that what you saw was not 35mm. You saw HD-cam, and there are actually 35mm prints of this, and seeing it here was very strange. It was unusually solid, rock solid, a little bit troublingly solid, although that is the ideal that film technology has been striving for. But 35mm prints have all these scratches and splices, and grain and a kind of warmth that moves around, which is almost like a kind of very desirable filter that really warms up the film. So watching it in 35mm is different. I was noticing how computery it looked on the HD projection at this particular size, because I was looking for imperfections that simply weren’t there.

But anyway, yeah, I did some paintings on parchment paper. To me, some things were simple, because I only had me working on the animation, and I used as many computer shortcuts as I possibly could. Most of the technique was what’s called “cut-outs,” so I made pieces of things, moved them around, and the computer does what’s called “tweening.” [i.e., in-betweening, filling in the frames between key points] There’s a little bit of full animation in there. It would take a long time to say everything that I did.

KT: Yeah, but every bit of that visual material was something that you put into the computer in some fashion, so that-

NP: The computer didn’t draw it, that’s for sure. I drew it, whether I started with paper or drawing on a little [digital] graphics tablet or eventually I got what’s called a Cintiq, which is a monitor you can draw on. You can draw straight into a program through the monitor, and so what’s on the monitor-it tricks you into thinking you’re actually drawing on the screen, but it went through both my hand and the computer.

KT: Is this the kind of thing you teach? Do your students learn how to do this kind of animation?

NP: No. I’d love to teach this. A lot of the students are just not [inaudible]. So right now I’m teaching visual storytelling, which is a much more basic class, and I taught something called “classic film and video” for a while at Parsons [School of Design]. I actually really like to teach artists. I’m teaching people who already know what they want to say and already have a voice and just need a little bit of technical-it’s slightly faster if they ask me rather than reading a manual. I learned by reading manuals.

RL: It struck me that you’re a woman artist making an animated feature, and actually one of the very first animated features, done ten years before Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, was Lotte Reiniger’s The Adventures of Prince Ahmed, which also deals with Eastern myths. You actually did a little bit of the cut-out animation there, too, with the shadow-puppets. That brings a nice circularity-

NP: Well, hopefully this isn’t the last one!

KT: Was that the silent film that you referred to in your film?

NP: I still haven’t seen that film. First of all, everything has influenced me, because everything influences everything else. Culture [inaudible] language, so there’s a language of cell phones, a language of animation that comes from every piece of animation that’s been shared ever. So even if I haven’t been directly influenced by something, I haven’t seen the actual film, I will have been indirectly influenced by it simply keeping my eyes open.

RL: All the Annette Hanshaw songs are accompanied with the Flash animation, but it looked like there was a couple of different styles of Indian art represented there, from different periods. Tell us a little bit about what the choice was.

NP: The Ramayana is thousands of years old, and it also covers an enormous chunk of geography. It’s very popular not just in India but also in Cambodia, Thailand, Polynesia, Indonesia, this huge swath of South and Southeast Asia-parts of China. So there’s just this enormous range of art styles that have come up around it, and the styles I used in the film were influenced by just a tiny, tiny sample of that. Obviously shadow puppets. The designs were derived from puppets from Indonesia, Korea, Thailand, Malaysia, and also India. There’s a whole slew of paintings. There’s lots of Ramayana paintings that were actually commissioned by Muslim [inaudible] who had money. There were collages of these traditional arts. Everything went into the hopper, all going into my head Everything goes in there, grinds up, and comes out.

KT: Traditionally in animation the entire soundtrack is done first, which is not the way it’s done in regular live-action filmmaking, but of course it’s virtually impossible to synchronize cartoons if you have someone doing the voices after the animation is done. So could you tell us a little about the soundtrack and how much of it you had ready by the time you started the visuals?

NP: Well, I should say, the whole production, it’s not like I had everything ready when I started the visuals. The way you’re supposed to make a film, first you’re supposed to write a treatment, and then you’re supposed to write a script, and then you’re supposed to, if it’s animation, have everything designed and do breakdowns and storyboards and this and that, and then at the very end you animate it.

I didn’t have to do that, because it was just me working and it was with a computer. So I came up with things as I was going along. The whole structure of the story was there, because the Ramayana is this very well-established story that’s been told billions of times. I knew that story. I also had the songs, so the first thing that I synchronized and edited was the songs. As I was working on those, I was figuring out how the rest of the film was going to come together. The [inaudible] part of the film was the three narrators, who were just friends of mine who I convinced to go into a recording studio, and I asked some questions about the Ramayana. They were all very busy and went, “Oh, I should have read more before.” The conversation that they had was actually quite typical, because I had so many conversations with so many Indians, who-it was just uncanny, they really captured the twenty-first century zeitgeist of Ramayana, I guess.

RL: That intermission was a bit daring.

NP: I should mention that the 35mm print, depending on where you see it, it has surround sound and the HD only has stereo. If you see it on 35mm, depending on what speaker you’re near, you’ll hear different complete conversations coming out of each. Some of those conversations are extremely funny. I recommend the left rear speaker. There will be Will Franken, who’s a distribution executive, talking about unsellable the film is. And there are people on the front right speaking Hindi. I think they’re saying, “I thought this was a children’s film.”

So, yes, intermission. Old American musicals had intermissions. I was watching some of them while I was working on the film, and sure enough, two-thirds of the way through, intermission comes up. Bollywood films still have intermissions-a three- or four-hour-long Bollywood film has a little gap. So it was a tribute to both old American musical films and all Bollywood films. When I showed the film in Livingston, New Jersey to an audience of primarily Indian-Americans, during intermission they just left for 15 minutes. And they missed my favorite part of the film, which is the part that comes a minute after the intermission.

Nina’s favorite part, shortly after the intermission

KT: I can second that statement about the 35mm, because I was lucky enough to see this film three weeks ago in 35mm at the Wisconsin Film Festival, and it’s a different experience. I’ve enjoyed both of them, but I think there are definite advantages to 35.

It’s actually much easier for most people to see this film on a computer screen or television, because you chose a very unusual way to disseminate the film to the public. Can you talk a little about that?

NP: Why, yes, I can! You can see this film for free online if you go to sitasingstheblues.com and follow a variety of links and get the film. You can get everything from a streaming version from New York Public Television to a 200 gigabyte file from which you can make your own 35mm print if you have $30,000 to download it. Briefly, every file I have for the film is either online now or it’s going to go online. It’s a completely decentralized distribution model. People have compared it to Radiohead’s [inaudible] English model [for their “In Rainbows” album, 2007], but that’s different, because that relied on a single, central location where you got the audio, and it was tracked. It was simply what you decided to pay.

Mine is totally decentralized. I shouldn’t even call it “mine” anymore. It’s yours. This film belongs to you and everybody else in the world. The audience, you and the rest of the world is actually the distributor of the film. So I’m not maintaining a server or host or anything like that. Everyone else is. We put it on archive.org, a fabulous website, and encourage people to BitTorrent it and share it. That’s what’s happening, and we hope people do it more. There’s also broadcast versions, which you can download. If anyone here is from a television station, you can broadcast this for free.

Which begs the question, why is Nina Paley giving her work away for free? Doesn’t she want to get money? The answer is yes, I want to get money, and I believe that I will get money. I think I am getting money from this, because the more people share the film, the more valuable the film becomes. I have told people after screenings that they can get the film for free online, but I have some DVDs which I sell for twenty bucks, and here for twenty-five bucks-the Virginia is still remodeling, so this is for the Virginia.

I should also mention regarding DVDs that we, my mom-Oh, I should mention my mom! Sorry, I[inaudible] my parents, of course, who gave me the gift of life and all that, but my mom, who gave Sita Sings the Blues the gift of being its festival-relations manager, which is a huge, huge job. For those who don’t know, my mom was the main administrator of the math department of the University of Illinois and is a spreadsheet master and business-communications master and stuff like that and has been just essential to the film having such a successful festival life. So, thank you, mom! [Applause]

Anyway, I have made thousands of festival screeners so that festivals will have something to preview, and we’re down to the last 35, or at least we were this morning, and we handed them to the people in the Virginia, and that’s it for DVDs until a few weeks from now I’ll have the new purchasable DVD edition available.

RL: Will there be special features?

NP: Because the film is free, people can subtitle it freely, and the new one will have some subtitles. There’s gonna be more subtitles online. It’s been translated into French and Hebrew and Spanish and Italian and pirate. [applause and laugher covers a stretch of speech] The thing is, the film is now half-way. It will just continue growing, so whatever the DVD is, it’s just snatched off the stuff we have as of this week. So it’ll be the film, it’ll be a bonus feature called Fetch, a film I made, it’ll be some subtitles, I think there’ll be a couple different audio options.

It’ll be a very nice package, because basically what I’m selling is packaging for the film. If you have a computer, you’ve got your own packaging. You just download it. But many people just the same want an actual printed package. There’ll be two editions. There’s the artist’s edition, a limited edition of 4,999 DVDs, because for every five thousand DVDs I sell, I have to pay the licensers more money. You may think that’s too bad, and it’s OK if the other DVD distributors pay the licensers more money, but I [inaudible] paid $5,000 in order to decriminalize the film, so that I wouldn’t go to jail.

Jean Paley from the audience: Fifty thousand!

NP: Fifty thousand, yeah. Fifty thousand dollars is enough.

KT: Which is for the song rights.

NP: Yes. Those old songs. I cannot thank Roger enough for writing about this film. Also, after he wrote about it on his blog, my colleague, a professor of copyright law here, said, “Does he know about the copyright issue of the songs?” The film uses old songs that were written and performed in the late 1920s. Had they been from 1923, they would be in public domain now. When they were written, they were supposed to be in public domain in the 1980s, but there have been these continuous, retroactive copyright extensions, so they may never enter the public domain.

NP: Yes. Those old songs. I cannot thank Roger enough for writing about this film. Also, after he wrote about it on his blog, my colleague, a professor of copyright law here, said, “Does he know about the copyright issue of the songs?” The film uses old songs that were written and performed in the late 1920s. Had they been from 1923, they would be in public domain now. When they were written, they were supposed to be in public domain in the 1980s, but there have been these continuous, retroactive copyright extensions, so they may never enter the public domain.

We were so relieved that Roger agreed that what copyright law has become is really not serving culture or people. These copyright extensions have really gotten way out of control. [applause] They [inaudible] me so much that I actually question copyright fundamentally, but even those who don’t agree, I think, that retroactively assigning copyrights is not actually acting as an incentive for dead artists to create more art.

Whereas these songs. It’s a scandal, these beautiful songs! Many people have never heard of them until seeing my film. That’s just a crime. She was a huge seller in the twenties. Huge! Why is it that we can’t hear her music? It’s because all the rights are controlled by corporations, and anybody who dares to share Annette Hanshaw’s music is risking a lawsuit or jail. As I did. As I decided I was willing to do. I didn’t realize I was doing civil disobedience at the time. I didn’t realize how severe the possible punishments were for doing this kind of thing, but even had I know I would have done it anyway. I have no regrets. Now, I’m turning into a full-time free-culture activist. [applause]

Some of you may know my dad is a retired math professor here. But I grew up in this science and engineering culture. In all these books about copyright, people always talk about scientists and how scientists share information. How it’s really important, this really strong ethic of sharing information. Scientists seek to discover some really great information to share it with the community, and that actually benefits the contributing scientist.

As an artist, it’s actually exactly the same. My status vastly increases as I share this film. But I think it’s quite possible that the way I was growing up here formed me that way, to see it this way. A lot of artists don’t see it this way. People see it as property. I just wanted to share what I’ve been thinking about a lot. [applause]

RL: Has your film prompted an Annette Hanshaw revival?

NP: Not an official one. I should mention that the only reason that these songs exist in a form in which we can hear them at all is because of the efforts of underground record collectors, because the corporations that have the official rights to control this music hadn’t done it. They actually scrapped the masters. There’s no surviving masters of Annette Hanshaw’s recordings, because they were so very valuable that in the forties they were sent for scrap metal. And yet somehow it would be theft if somebody in America released her recordings today.

But yeah, there’s this wonderful network of record collectors who just preserved her stuff on lacquer, and that’s how I originally heard her songs. I was staying in the home of a record collector, and he actually had Annette Hanshaw on 78s. And this is the tip of the iceberg. There’s so much amazing culture that we’ve forgotten all about and can’t get at. There’s this wealth of films that’s just sitting there, that nobody can restore, because if you restore a film you don’t have the rights to, you can get sued for showing it! And it’s very expensive to restore films, so the result is, nobody wants to touch it. Everyone is scared, and our cinematic history is disintegrating. It doesn’t last. Records actually last longer than film.

KT: We should point out that you have a very informative website, ninapaley.com.

NP: Yeah, it’s now blog.ninapaley.com, and there’s also sitasingstheblues.com, and I’m also artist-in-residence at QuestionCopyright.org.

KT: Most of the ways to get the film out to people that you’ve talked about would be DVDs or downloaded copies, but your film is still being shown in a lot of festivals, well into the future.

NP: Yeah, festivals and also cinemas. Hurray for independent cinemas! I support them, and they support me. [applause] There’s some great cinemas programming it. It’s going to be in Chicago at the Gene Siskel Film Center, very soon. And it’s going to be in Vancouver. It’s going to be in some other cities. And there’s no real time limit. There’s no advertising for this film, no paid advertising. The audience is also the public-relations department, so it’s gone completely by word of mouth, word of web, word of blog. There’s absolutely no end time. It can be screened anytime. There are some prints circulating right now, and hopefully any cinema that has a little off time and wants to give it a shot, can program it.

KT: Your mother was telling me that the film will be probably in two hundred festivals.

NP: Not two hundred. I think it’s been in a hundred.

KT: Well, there’s a long list on your website that goes into 2010, I think, so [to audience] you want to tell your friends who live in those various cities, see it on the big screen!

[Note: the list of screenings and festivals on the film’s website numbered exactly 200 as of May 4.]

NP: When I decided to give it away free online, what finally made me realize this was viable was when I realized that this didn’t mean it wouldn’t be seen on the big screen, that the internet is not a replacement for a theater. It’s a complement. Many people will see it online and go, “Wow, I wish I could see this on the big screen!” And so they can, and some people like to see it more than once. Another thing is, you see it online, and that increases the demand for the DVDs. So it’s the opposite of what the record and movie industries say. Actually, the more shared something is, the more demand there is for it. [applause]

RL: Are you doing this for your short films, too?

NP: I would like it for the short films. It’s simply a matter of time. I want to do it with my comic strips. I’m still seeking a volunteer, although someone contacted me from the U[niversity] of I[llinois], I think from the library, whom I need to call. Maybe everything will be scanned and uploaded right here from Urbana, which would be awesome. But yeah, I want to go back. Just as Congress is retroactively extending copyrights, I’m retroactively de-copyrighting all of my stuff and sharing it, because that will make it more valuable. Imagine some original comic strip that everybody knows. That’s much more valuable to people than a comic strip that no one’s ever seen. Andy Warhol, for example. Some Warhol print just fetched some huge price at auction. There was a photo of it up in the newspaper. We all know what Andy Warhol’s prints look like, even though most of us have never seen them in the flesh. We all know that they’re worth a lot, ‘cause they’re famous. They’re famous because people reproduce images of them.

[People do indeed. Here’s another of Nina’s:]

Love isn’t all you need

Pat and Mike.

DB still in HK:

Last week the Hong Kong International Film Festival hosted Gerry Peary’s For the Love of Movies: The Story of American Film Criticism. It’s a lively and thoughtful survey, interspersing interviews with contemporary critics with a chronological account that runs from Frank E. Woods to Harry Knowles. It goes into particular depth on the controversies around Pauline Kael and Andrew Sarris, but it even spares some kind words for Bosley Crowther.

Some valuable points are made concisely. Peary indicates that the alternative weeklies of the 1970s and 1980s were seedbeds for critics who moved into more mainstream venues like Entertainment Weekly. I also liked the emphasis on fanzines, which too often get forgotten as precedents for internet writing. In all, For the Love of Movies offers a concise, entertaining account of mass-market movie criticism, and I think a lot of universities would want to use it in film and journalism courses.

I should declare a personal connection here. I’ve known Gerry since 1973, when I came to teach at the University of Wisconsin—Madison. Like me, he was finishing a dissertation: he was writing a history of the gangster films made before Little Caesar. We spent good lunches together at the Fish Store. Gerry was one of the moving spirits of Madison movie culture—running a film society, writing and editing for the student paper, working with John Davis, Susan Dalton, Tim Onosko, and Tom Flinn on The Velvet Light Trap. I knew I’d come to the right place when somebody would drop by my office to talk about last night’s screening of Underworld or Steamboat ‘Round the Bend.

I should declare a personal connection here. I’ve known Gerry since 1973, when I came to teach at the University of Wisconsin—Madison. Like me, he was finishing a dissertation: he was writing a history of the gangster films made before Little Caesar. We spent good lunches together at the Fish Store. Gerry was one of the moving spirits of Madison movie culture—running a film society, writing and editing for the student paper, working with John Davis, Susan Dalton, Tim Onosko, and Tom Flinn on The Velvet Light Trap. I knew I’d come to the right place when somebody would drop by my office to talk about last night’s screening of Underworld or Steamboat ‘Round the Bend.

Like many of our generation, Gerry became a mixture of critic and academic. He taught at several colleges, wrote for The Boston Phoenix, and published books, notably Women and the Cinema: A Critical Anthology (1977) and The Modern American Novel and the Movies (1977). Most recently he’s edited collections of interviews with Tarantino and John Ford. He has moved smoothly into online publishing with a packed and wide-ranging website.

Gerry’s documentary comes along at a parlous time, of course. Most of the footage was taken before the wave of downsizings that lopped reviewers off newspaper staffs, but already tremors were registered in some interviewees’ remarks. Apart from this topical interest, the film set me thinking: Is love of movies enough to make someone a good critic? It’s a necessary condition, surely, but is it sufficient?

Gerry’s film includes the inevitable question: What movie imbued each critic with a passion for cinema? I have to say that I have never found this an interesting question, or at least any more interesting when asked of a professional critic than of an ordinary cinephile. Watching Gerry’s documentary made me think that everybody has such formative experiences, and nearly everybody loves movies. But what sets a critic apart?

Elsewhere, I’ve argued that a piece of critical writing ideally should offer ideas, information, and opinion—served up in decent, preferably absorbing prose. This is a counsel of perfection, but I think the formula ideas + information + opinion + good or great writing isn’t a bad one.

You really can’t write about the arts without having some opinion at the center of your work. Too often, though, a critic’s opinions come down simply to evaluations. Evaluation is important, but it has several facets, as I’ve tried to suggest here. And other sorts of opinions can also drive an argument. You can have an opinion about the film’s place in history, or its contribution to a trend, or its most original moments. Opinions like these allow you to build an argument, drawing on evidence or examples in or around the movie in question. Several of our blog entries on this site are opinion-driven, but not necessarily evaluations of the movies.

Most people think that film criticism is largely a matter of stating evaluations of a film, based either in criteria or personal taste, and putting those evaluations into user-friendly prose. If that’s all a critic does, why not find bloggers who can do the same, and maybe better and surely cheaper than print-based critics? We all judge the movies we see, and the world teems with arresting writers, so with the Internet why do we need professional critics? We all love movies, and many of us want to show our love by writing about them.

In other words, the problem may be that film criticism, in both print and the net, is currently short on information and ideas. Not many writers bother to put films into historical context, to analyze particular sequences, to supply production information that would be relevant to appreciating the movies. Above all, not many have genuine ideas—not statements of judgments, but notions about how movies work, how they achieve artistic value, how they speak to larger concerns. The One Big Idea that most critics have is that movies reflect their times. This, I’ve suggested at painful length, is no idea at all.

Once upon a time, critics were driven by ideas. The earliest critics, like Frank Woods and Rudolf Arnheim, were struggling to define the particular strengths of this new art form. Later writers like André Bazin and the Cahiers crew tried to answer tough idea-based questions. What is distinctive about sound cinema? How can films creatively adapt novels and plays? What are the dominant “rules” of filmmaking ? (And how might they be broken?) What constitutes a cinematic modernism worthy of that in other arts? You could argue that without Bazin and his younger protégés, we literally couldn’t see the artistry in the elegant staging of a film like George Cukor’s Pat and Mike. Manny Farber, celebrated for his bebop writing style, also floated wider ideas about how the Hollywood industry’s demand for a flow of product could yield unpredictable, febrile results.

One of the reasons that Sarris and Kael mattered, as Gerry’s documentary points out, was that they represented alternative ideas of cinema. Sarris wanted to show, in the vein of Cahiers, that film was an expressive medium comparable in richness and scope to the other arts. One way to do that (not the only way) was to show that artists had mastered said medium. Kael, perhaps anticipating trends in Cultural Studies, argued that cinema’s importance lay in being opposed to high art and part of a raucous, occasionally vulgar popular culture. This dispute isn’t only a matter of taste or jockeying for power: It is genuinely about something bigger than the individual movie.

During the Q & A, it emerged that at the same period critics’ ideas had an impact on filmmaking. Sarris’s promotion of the director as prime creator, with a bardic voice and a personal vision, was quickly taken up by Hollywood. Now every film is “a film by….” or “ a … film”: auteur theory shows up in the credits. Similarly, the concept of film noir was constructed by French critics and imported to the US by Paul Schrader. Suddenly, unheralded films like The Big Combo popped up on the radar. Today viewers routinely talk about film noir, and filmmakers produce “neo-noirs.” It seems to me as well that Hollywood became somewhat more sensitive to representation of women after Molly Haskell (here, alongside Sarris) had brought feminist ideas to bear on the American studio tradition, avoiding simple celebration or denunciation. Film criticism had a robust impact on the industry when it trafficked in ideas.

During the Q & A, it emerged that at the same period critics’ ideas had an impact on filmmaking. Sarris’s promotion of the director as prime creator, with a bardic voice and a personal vision, was quickly taken up by Hollywood. Now every film is “a film by….” or “ a … film”: auteur theory shows up in the credits. Similarly, the concept of film noir was constructed by French critics and imported to the US by Paul Schrader. Suddenly, unheralded films like The Big Combo popped up on the radar. Today viewers routinely talk about film noir, and filmmakers produce “neo-noirs.” It seems to me as well that Hollywood became somewhat more sensitive to representation of women after Molly Haskell (here, alongside Sarris) had brought feminist ideas to bear on the American studio tradition, avoiding simple celebration or denunciation. Film criticism had a robust impact on the industry when it trafficked in ideas.

You can argue that these are old examples. What new ideas are forthcoming from mainstream film criticism? In the Q & A Gerry, like the rest of us, couldn’t come up with many. On reflection, I wonder if the rise of academic film studies forced ideas to migrate to the specialized journals and the Routledge monograph. These ideas also had a different ambit—sometimes not particularly focused on cinema, or on aesthetics, or on creative problem-solving.

Of course ideas don’t move on their own. A more concrete way to put this is that bright, conceptually oriented young people who in an earlier era would have become journalistic critics became professors instead. The division of labor, it seems, was to aim Film Studies at an increasingly esoteric elite, and let film reviewers address the masses. It’s an unhappy state of affairs that we still confront: recondite interpretations in the university, snap evaluations in the newspapers. You can also argue that print reviewers, by becoming less idea-driven, paved the way for DIY criticism on the net.

What about information, the other ingredient I mentioned? If we think of film criticism as a part of arts journalism, we have to admit that most of it can’t compare to the educational depth offered by the best criticism of music, dance, or the visual arts. You can learn more from Richard Taruskin on a Rimsky performance or Robert Hughes on a Goya show than you can learn about cinema from almost any critic I can think of. These writers bring a lifetime of study to their work, and they can invoke relevant comparisons, sharp examples, and quick analytical probes that illuminate the work at hand. Even academically trained film reviewers don’t take the occasion to teach.

Most of the print criticism I’ve seen today is remarkably uninformative about the range and depth of the art form, its traditions and capacities. Perhaps editors think that film isn’t worthy of in-depth writing, or perhaps their readers would resist. As if to recall the battles that Woods, Arnheim and others were fighting, cinema is still not taken seriously as an art form by the general public or even, I regret to say, by most academics.

Yet other aspects of information could be relevant. Close analysis offers us information about how the parts work together, how details cohere and motifs get transformed. For an example of how analysis can be brought into a newspaper’s columns, see Manohla Dargis on one scene in Zodiac.

I’d also be inclined to see description—close, detailed, loving or devastating—as providing information. It’s no small thing to capture the sensuous surface of an artwork, as Susan Sontag put it. Good critics seek to evoke the tone or tempo of a film, its atmosphere and center of gravity. We tend to think that this is a matter of literary style, but it’s quite possible that sheer style is overrated. (Yes, I’m thinking of Agee.) Thanks to our old friends adjective and metaphor, even a less-than-great writer can inform us of what a film looks and sounds like.

I’d also be inclined to see description—close, detailed, loving or devastating—as providing information. It’s no small thing to capture the sensuous surface of an artwork, as Susan Sontag put it. Good critics seek to evoke the tone or tempo of a film, its atmosphere and center of gravity. We tend to think that this is a matter of literary style, but it’s quite possible that sheer style is overrated. (Yes, I’m thinking of Agee.) Thanks to our old friends adjective and metaphor, even a less-than-great writer can inform us of what a film looks and sounds like.

In any event, I’m coming to the view that the greatest criticism combines all the elements I’ve mentioned. As so often in life, love isn’t always enough.

Gerry’s documentary doesn’t distinguish between critics and reviewers, but we probably should. Reviewers typically give us opinions and a smattering of information (plot situations, or production background culled from presskits), wrapped up in a writing style that aims for quick consumption. Today anybody with a web connection can be a reviewer.

Exemplary critics try for more: analysis and interpretation, ideas and information, lucidity and nuance. Such critics are as rare now as they have ever been. Far from being threatened by the Internet, however, they have more opportunities to nourish film culture than ever before.

The Big Combo.

PS 4 April (HK time): Thanks to Justin Mory for correcting a name error in the original post!

Niceties: how classical filmmaking can be at once simple and precise

DB here:

A film academic once complained that I was too preoccupied with “formalistic niceties.” So here I go again. But read no further if you haven’t seen Christopher Nolan’s The Prestige.

Dueling magicians: The film’s premise might be considered high-concept. In turn-of-the-century London, two young conjurers launch their careers with different attitudes toward their craft. Robert Angier favors audacious showmanship, while Alfred Borden is committed to finding a trick that will baffle the experts. Their rivalry is ignited when Alfred accidentally kills Angier’s wife during a dangerous underwater stunt. Their struggle peaks around each one’s supreme trick: transporting himself from one point to another instantaneously.

The item that attracts my attention today is established in the film’s opening sequence. As the voice of Cutter (Michael Caine) explains a magic trick’s three acts, we see a climactic confrontation between the competitors. Hoping to discover Robert’s secret, Alfred watches the Real Transported Man performance from the audience.

As Cutter’s narration mentions “a man,” the camera picks out Alfred in the crowd. Cut to Robert onstage, a shift that establishes the two as our protagonists.

What interests me is the view of the bearded Alfred: a medium-shot framing him nearly in profile facing right. This framing will be repeated, but varied, when Alfred’s voice-over diary entry introduces both him and Robert as apprentices, working as audience shills for another magician:

We were two young men at the start of a great career—two young men devoted to an illusion, who never intended to hurt anyone.

The new shot parallels the introduction of Alfred in the first scene, but varies it. Again we see Alfred in the audience, but now without a beard, and the camera tracks rightward to show Robert in another row.

In this sequence, our protagonists are connected by a camera movement rather than the cut employed in the opening. The two men’s reactions—Robert grinning (his wife is onstage), Alfred more pensive—add to the characterizations that we will see played out.

This simple camera motif gets varied further in the course of the film. The disastrous immersion illusion that drowns Robert’s wife is initiated by another tracking shot of the two men in the audience, a variation of the earlier shot.

The new combination starts with Robert and ends on Alfred. At this point, not only are the two men linked but they replace one another. If you want to push your luck, you could say that this variant quietly affirms the film’s overall dynamic of substitution (doubles, twins, clones).

Earlier, a contrasting way of showing the men in an audience is given us when they attend a performance of the wizard Chung Ling Soo. Cutter provides a dialogue hook, warning Robert that “the blokes at the ends of row three and four” can see him kissing his wife’s leg.

Cut to our protagonists, sitting at the end of a row watching the Chinese magician.

A nicety: Now the men are sitting side by side and facing left rather than right. Just through camera placement and character position, we know we’re in a different performance, one in which our apprentices play no role.

As they study the trick, Nolan gives us another characterizing shot: Robert is amazed, but Alfred grins: He’s worked out Chung’s secret.

What would have happened if Nolan had framed the men sitting apart and/or facing to the right? For an instant we might have thought we were back in the act they shill for. Simple but reiterated differences assure immediate comprehension: medium shot/ long shot, looking rightward/ looking leftward, men in different rows/ men in the same row. Just as the repeated framings of their own act clarify the situation, so do these little polarities. Call it redundancy, if you like, but it’s also precision and economy.

With Julia’s death, the men become enemies. But each will still slip into the audience of the other’s performances. From now on, the magician is always on the right, the onlooker on the left. Nolan and company could have handled their rivalry in camera setups that exactly mimic the early ones. Instead, a new pattern of parallels comes into play, building on the earlier ones but different enough to heighten the symmetries.

The new pattern is set up by restricting our range of knowledge. First, we are attached to Alfred when he performs his bullet catch in a barroom theatre. Robert, seeking vengeance for Julia’s drowning, steps up to spoil the trick, but we don’t know he’s there until Alfred does, and then it’s too late.

Similarly, we’re restricted to Robert’s range of knowledge when he tries to execute his disappearing dove trick. Only when Alfred is about to trigger the collapsing cage—killing the dove and wounding a lady from the audience—does Robert realize that his adversary has struck back.

Another nicety: The two shots of each man in similar disguises, seen in 3/4 view, reset the stylistic parameters. But the image of the bearded Alfred is given extra punch through a tilt up from his missing fingers–the result of the parallel, bullet-catch scene before.

The whole pattern shifts yet again when Robert sneaks in to watch Alfred’s Transported Man illusion. We get a shot of him (in a beard again) that fuses two of the cues from the earlier scenes: He’s in the audience, as in the early sequences, but he’s shown from an angle congruent with that of the earlier beard shots.

And perhaps we can take the shot of Robert at home, telling of his amazement at Alfred’s illusion, as an echo of the initial prototype: A magician staring intently rightward at a dazzling trick played out offscreen, but now in memory.

Robert returns from Colorado with the Tesla-designed “Real Transported Man,” and Alfred’s visit to watch the stunt reworks the givens of this pattern yet again. Alfred is seated, minimally disguised, in the standard audience spot looking right, but he is not in profile and the camera position is much closer than before. The answering shot of Robert onstage recalls the gesture we saw at the film’s outset and anticipates what we will see when that opening scene is replayed, with the wicked Alfred climbing onstage.

At the close of the trick, yet one more variant: Robert appears in the rear balcony and the crowd all turns to watch him off left.

After a glance back, Alfred turns away, looking right–the first time any character has flinched from the performance. His puzzlement is mixed with anger (at last a trick he can’t see through), a less charitable response than we saw in Robert’s stunned fireside recollection of Alfred’s Transported Man.

The things held constant, such as camera placement and position in the locale, set off the differences in characters’ disguises and reactions, while this shot carries faint echoes of our very first view of Alfred during Cutter’s voice-over monologue. That view, and its answering shot of Robert in the spotlight, will recur when Robert’s pseudo-death is replayed.

Nolan’s audacious film is built out of more marked parallels than these, but I wanted merely to highlight the ups and downs of one small pattern. Many films work varied repetitions like these into their shot-by-shot texture. Back in the 1930s, Eisenstein saw this possibility clearly, as I try to show in my book on his work. In the 1960s and 1970s, Raymond Bellour called our attention to such patterns in films by Hitchcock, Hawks, and Minnelli. His collection of essays The Analysis of Film includes pioneering studies of how fine-grained such things can become.

I wouldn’t go as far as Bellour does in seeing varied repetition as the motor force of classical filmmaking, but it surely plays an important role. What he takes as a manifestation of pure textual difference I’m inclined to psychologize: these differences help the audience understand, usually without awareness, the ongoing narrative dynamic and have the extra payoff of creating tacit narrative parallels. But from either perspective, object-centered or response-centered, studying such microforms is enlightening. It’s a way to understand films as wholes, dynamic constructions that shift their shapes across the time of their unfolding. Moreover, by examining things this closely, we can try to understand not only how this or that film works, but how this or that film relies on principles distinctive of a filmmaking tradition. Consider this another plug for poetics.

I’d add that such principles neatly fuse two pressures: toward narrative coherence and comprehension on the one hand, and toward production efficiency on the other. It’s cheaper and easier to repeat camera setups if you can. Artistic economy and financial economy can work together, nicely.

Speaking of repetitions….

Slumdogged by the past

DB here:

In graduate school a professor of mine claimed that one benefit of studying film history was that “you’re never surprised by anything that comes along.”

This isn’t something to tell young people. They want to be surprised, preferably every few hours. So I rejected the professor’s comment, and I still think it’s not a solid rationale for studying film history. But I can’t deny that doing historical research does give you a twinge of déjà vu.

For instance, the film industry’s current efforts to sell Imax and 3-D irresistibly remind me of what happened in the early 1950s, when Hollywood went over to widescreen (Cinerama, CinemaScope, and the like), stereophonic sound, and for a little while 3-D. Then the need was to yank people away from their TV sets and barbecue pits. Now people need to be wooed from videogames and the Net. But the logic is the same: Offer people something they can’t get at home. It’s 1953 once more.

So historians can’t resist the “Here we go again” reflex. But they shouldn’t turn that into a languid “I’ve seen it all before.” Because we can genuinely be surprised. Occasionally, there are really innovative movies that, no matter how much they owe to tradition, constitute milestones. In my view, Kiarostami’s Through the Olive Trees, Hou’s City of Sadness, Wong’s Chungking Express, Tarr’s Satantango, and Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction are among the 1990s examples of strong and original works.

More often, the films we see draw on film history in milder ways than these milestones. But this doesn’t mean that these movies lack significance or impact. We can be agreeably surprised by the ways in which a filmmaker energizes long-standing cinematic traditions by blending them unexpectedly, tweaking them in fresh ways, setting them loose on new material. And the more you know of those traditions and conventions, the more you can appreciate how they’re modified. Admiring genius shouldn’t keep us from savoring ingenuity.

Which brings me to Slumdog Millionaire. I happen to like the film reasonably well. Part of my enjoyment is based on seeing how forms and formulas drawn from across film history have an enduring appeal. Many people whose judgments I respect hate the movie, and they would probably call what follows an ode to clichés. But I mean this set of notes in the same spirit as my comments on The Dark Knight (which I don’t admire). Even if you disagree with my predilections, you may find something intriguing in Slumdog’s ties to tradition. These ties also suggest why the movie is so ingratiating to so many.

Warning: What follows contains plot spoilers, revelatory images, and atrocious puns.

Slumdog and pony show

Adaptation is still king. Almost as soon as movies started telling stories, they were borrowing from other media. Many of this year’s Oscar candidates are based on plays, novels, and graphic novels. Slumdog is a redo of Vikas Swarup’s 2005 novel Q & A. The book provides the basic situation of a poor youth implausibly triumphing on a version of Who Wants to be a Millionaire? The novel also lays down the film’s overall architecture: in the present, the hero narrates his past, tying each flashback to a round of the game and a relevant question. In the novel, the video replays are described, but of course they’re shown in the film.

There are many disparities between novel and movie, but for now I simply note two. First, Swarup’s book has several minor threads of action, but the film concentrates on Jamal’s love of Latika. (The screenwriter Simon Beaufoy has melded two female characters into one.) Correspondingly, the book introduces a romance plot comparatively late, whereas the film initiates Jamal’s love of Latika in their childhoods. Such choices give the film a simpler through-line. Second, whereas Q & A skips back and forth through Jamal’s life, keying story events to the quiz questions, the film’s flashbacks follow the chronology strictly. This is a good example of how screenwriters are inclined to adjust the plasticity of literary time to the fact that, at least in theatrical screenings, audiences can’t stop and go back to check story order. Clarity of chronology is the default in classical film storytelling.

Then there’s the double plotline. The streamlining of Swarup’s novel points up one convention of Hollywood narrative cinema. The assortment of characters and the twists in the original novel are squeezed down to the two sorts of plotlines we find in most studio films: a line of action involving heterosexual romance and a second line of action, sometimes another romance but just as often involving work. The common work/ family tension of contemporary film plotting is to some extent built into the Hollywood system.

Beaufoy has sharpened the plot by giving Jamal a basic goal: to unite with Latika. The quiz episodes form a means to that end: the boy goes on the show because he knows she watches it. If told in chronological order, the quiz-show stretches would have come late in the film and become a fairly monotonous pendant to the romance plot. One of the many effects of the flashback arrangement is to give the subsidiary goal more prominence, creating a parallel track for the entire film to move along and arousing anomalous suspense. (We know the outcome, but how do we get there?)

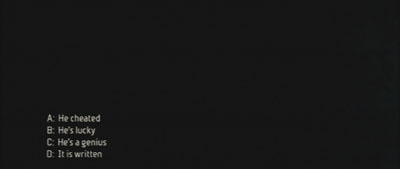

Q & A. Swarup’s novel begins: “I have been arrested. For winning a quiz show.”

We have to ask: What could make such a thing happen? Soon the police and the show’s producers are wondering something more specific. How could Ram, an ignorant waiter, have gotten the answers right without cheating?

Noël Carroll proposes that narratives engage us by positing questions, either explicitly or implicitly. Stories in popular media, he suggests, induce the reader to ask rather clear-cut ones, and these will get reframed, deferred, toyed with, and in the short or long run answered.

Slumdog accepts this convention, presenting a cascade of questions to link its scenes and enhance our engagement. Will Jamel and Salim get Bachchan’s autograph? Will they survive the anti-Muslim riot? Will they escape the fate of the other captive beggar children? And so on.

More originally, the film cleverly melds the question-based appeal of narrative with the protocols of the game show, so that we are confronted with a multiple-choicer at the very start. (As in narrative itself, the truth comes at the end.) The principal question will be answered in the denouement, in a comparably impersonal register.

Flashbacks are also a long-standing storytelling device, as I was saying here last week. A canonical situation is the police interrogation that frames the past events, as in Mildred Pierce, The Usual Suspects, and Bertolucci’s The Grim Reaper. This narrating frame is comfortable and easy to assimilate, and it guides us in following the time shifts.

But 1960s cinema gave flashbacks a new force. From Hiroshima mon amour (1958) onward, brief and enigmatic flashbacks, interrupting the ongoing present-tense action, became common ways to engage the audience. Such is the case with the glimpse of Latika at the station that pops up during the questioning of Jamal, rendered as almost an eyeline match.

At this point we don’t know who she is, but the image creates curiosity that the story will eventually satisfy. Flashbacks can also remind us of things we’ve seen before, as when Jamal recalls, obsessively, the night he and Salim left Latika behind to Maman’s band. Boyle and company call on these time-honored devices in the assurance that wewill pick up on them immediately, as audiences have for decades.

Flashforwards are trickier, and rarer. The 1960s also saw some experimentation with images from future events interrupting the story’s present action. Unless you posit a character who can see the future, as in Don’t Look Now, flashforwards are usually felt as externally imposed, the traces of a filmmaker teasing us with images that we can’t really assimilate at this point. (See They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?) Such flashforwards pop up during the initial police torture of Jamal.

Encountering the bathtub shot so early in the film, we might take it as a flashback, but actually it anticipates a striking image at the climax, after Jamal has been released and returned to the show. I’d argue that the shot functions thematically, as a vivid announcement of the motif of dirty money that runs through the movie and is associated with not only the gangster world but also the corrupt game show.

Slumdog days

Empathy. One of the most powerful ways to get the audience emotionally involved is to show your protagonist treated unfairly. This happens in spades at the start of Slumdog. A serious-faced boy is subjected to awful torture, then he’s intimidated by unfeeling men in authority. He’s mocked as a chaiwallah by the unctuous host of the show, and laughed at by the audience. Once Jamal’s backstory starts, we see him as a kid (again running up against the law) and suffering a variety of miseries.

To keep Jamal from seeming a passive victim, he is given pluck and purpose. As a boy he resists the teacher, boldly jumps into human manure, shoves through a crowd to get an autograph, and eventually becomes a brazen freelance guide to the Taj Mahal. This is the sort of tenacious, resourceful kid who could get on TV and find Salim in teeming Mumbai. The slumdog is dogged.

Our sympathies spread and divide. Latika is also introduced being treated unfairly. An orphan after the riot, she squats in the rain until Jamal makes her the “Third Musketeer.” By contrast, Salim is introduced as a hard case—making money off access to a toilet, selling Jamal’s Bachchan autograph, resisting bringing Latika into their shelter, and eventually becoming Maman’s “dog” and Latika’s rapist. The double plotline gives us a hero bent on finding and rescuing his beloved; the under-plot gives us a shadier figure who finds redemption by risking his life a final time to help his friends. Jamal emerges ebullient from a sea of shit, but Salim dies drowned in the money he identified with power.

Our three main characters share a childhood, and what happens to them then prefigures what they will do as grownups. This is a long-standing device of classical cinema, stretching back to the silent era. Public Enemy and Angels with Dirty Faces give us the good brother and the bad brother. Wuthering Heights, Kings Row, and It’s a Wonderful Life present romances budding in childhood. These are plenty of less famous examples. Here, for instance, is a synopsis of Sentimental Tommy (1921), a film that may no longer exist.

The people of Thrums ostracize Grizel, a child of 12, and her mother, known as The Painted Lady, until newcomer Tommy Sandys, a highly imaginative boy, comes to the girl’s rescue and they become inseparable friends. Six years later Tommy returns from London, where he has achieved success as an author, and finds that Grizel still loves him. In a sentimental gesture he proposes, but she, realizing that he does not love her, rejects him. In London, Tommy is lionized by Lady Pippinworth, and he follows her to Switzerland. Having lost her mother and believing that Tommy needs her, Grizel comes to him but is overcome by grief to see his love for Lady Pippinworth. Remorseful, Tommy returns home, and after his careful nursing Grizel regains her sanity.

The device isn’t unknown in Indian cinema either; Parinda (1989) motivates the character relationships through actions set in childhood. Somehow, we are drawn to seeing one’s lifetime commitments etched early and fulfilled in adulthood.

This story pattern carries within it one of the great thematic oppositions of the cinema, the tension between destiny and accident. In Slumdog, The Three Musketeers may be introduced casually, but it will somehow provide a template for later events. Lovers are destined to meet, even if by chance, and when chance separates them, they are destined to reunite . . . if only by chance. A plot showing children together assures us that somehow they will re-meet, and their childhood traits and desires will inform what they do as adults. It is written.

This theme reaffirms the psychological consistency prized by classic film dramaturgy as well. Characters are introduced doing something, as we say, “characteristic,” and this first impression becomes all the more ingrained by the sense that things had to be this way. What you choose—say, to pursue the love of your childhood—manifests your character. But then, your character was already defined with special purity in that childhood.

Just another movie conceit? The existence of Classmates.com seems to suggest otherwise.

Chance needs an alibi, however. Hollywood films are filled with coincidences, and the rules of the game suggest that they need some minimal motivation. Not so much at the beginning, perhaps, because in a sense every plot is launched by a coincidence. But surely, our plausibilists ask, how could it happen that an uneducated slumdog would have just the right experiences to win the quiz? A lucky guy!

As Swarup realized, the flashback structure helps the audience by putting past experience and present quiz question in proximity for easy pickup. Yet as Beaufoy indicates in one of the most informative screenwriting interviews I know, the device also softens the impression of an outlandishly lucky contestant. At the start we already know that Jamal has won, so the question for us is not “How did he cheat?” but rather “What life experience does the question tap?” Each of the links is buried in a welter of other details, any one of which could tie into the correct answer. Moreover, sometimes the question asked precedes the relevant flashback, and sometimes it follows the flashback, further camouflaging the neat meshing of past and present.

It’s a diabolical contrivance. If you question Jamal’s luck, you ally with the overbearing authorities who suspect cheating. (You just think the film cheated.) Who wants to side with them? By the end the inevitability granted by the flashback obliges us to accept the inspector’s conclusion: “It is bizarrely plausible.”

The film has an even more devious out. Jamal can reason on his own, arriving at the Cambridge Circus answer. More important, his street smarts have made him such a good judge of character that he realizes that the MC is misleading him about the right answer to the penultimate question. So his winning isn’t entirely coincidence. Life experience has let him suss out the interpersonal dynamics behind the apparently objective game. As for the final answer—a lucky guess? Fate?—it’s a good example of how things can be written (in this case by Alexandre Dumas).

Slumdoggy style

The whole edifice is built on a cinematic technique about a hundred years old: parallel editing. Up to the climax, we alternate between three time frames. The police interrogation takes place in the present, the game show in the recent past (shifting from the video replay to the scenes themselves), and Jamal’s life in the more distant past. Any one of these time streams may be punctuated, as we’ve seen, by brief flashbacks. So the problem is how to manage the transitions between scenes in any one time frame and the transitions among time frames.

Needless to say, our old friend the hook—in dialogue, in imagery—is pressed into service often. A sound bridge may link two periods, with the quiz question echoing over a scene in the past. “How did you manage to get on the show?” Cut to Jamal serving tea in the call center. In a particularly smooth segue, the boys are thrown off the train as kids and roll to the ground as teenagers. There are negative hooks too. At the end of a quarrel with Salim, Jamal walks off saying, “I will never forgive you.” The next scene opens with the two of them sitting on the edge of an uncompleted high-rise building, having come to an uneasy truce.

In the climax, the three time frames all come into sync, creating a single ongoing present. Jamal will return to the show. The double-barreled questions are reformulated. Now we have genuine suspense: Will he win the top prize? Will Latika find him? To pose these engagingly, directors Danny Boyle and Loveleen Tandan create an old-fashioned chase to the rescue.

Each major character gets a line of action, all unwinding simultaneously: Salim prepares to sacrifice himself to the gangster Khan, she flees through traffic, and Jamal enters the contest’s final round. A fourth line of action is added, that of the public intensely following Jamal’s quest for a million. He has become the emblem of the slumdog who makes good.

The rescue doesn’t come off; Latika misses Jamal’s phone plea for a lifeline, and he is on his own. Fortunately, he trusts in luck because “Maybe it’s written, no?” The lovers reunite instead at the train station, where Jamal had pledged to wait for Latika every day at 5:00. Fitting, then, that in the epilogue a crowd shows up, standing in for all of Mumbai, singing and dancing to “Jai Ho” (“Victory”). All the remaining lines of action—Jamal, Latika, and the multitudes—assemble and then disperse in a classic ending: lovers turning from the camera and walking into their future, leaving us behind.

Then there’s the film’s slick technique. The whole thing is presented in a rapid-fire array, with nearly sixty scenes and about 2700 shots bombarding us in less than two hours. Critics both friendly and hostile have commented on the film’s headlong pacing and flamboyant pictorial design. If some of Slumdog’s storytelling strategies reach back to the earliest cinema, its look and feel seems tied to the 1990s and 2000s. We get harsh cuts, distended wide-angle compositions, hurtling camerawork, canted angles, dazzling montage sequences, faces split by the screen edge, zones of colored light, slow motion, fast motion, stepped motion, reverse motion (though seldom no motion). The pounding style, tinged with a certain cheekiness, is already there in most of Danny Boyle’s previous work. Like Baz Luhrmann, he seems to think that we need to see even the simplest action from every conceivable angle.

Yet the stylistic flamboyance isn’t unique to him. He is recombining items on the menu of contemporary cinema, as seen in films as various as Déjà Vu and City of God. (That menu in turn isn’t absolutely new either, but I’ve launched that case in The Way Hollywood Tells It.) More surprisingly, we find strong congruences between this movie’s style and trends in Indian cinema as well.

Over the last twenty years Indian cinema has cultivated its own fairly flashy action cinema, usually in crime films. Boyle has spoken of being influenced by two Ram Gopal Varma films, Satya (1998) and Company (2002). Company‘s thrusting wide angles, overhead shots, and pugilistic jump cuts would be right at home in Slumdog.

It seems, then, that Slumdog’s glazed, frenetic surface testifies to the globalization of one option for modern popular cinema. The film’s style seems to me a personalized variant of what has for better or worse become an international style.

Slumdogma

Boot Polish.

I’d like to mention many other ways in which the movie engages viewers, such as running (an index of popular cinema; does anybody run in Antonioni?). But I’ve said enough to suggest that the film is anchored in film history in ways that are likely to promote its appeal to a broad audience. The idea of looking for appeals that cross cultures rather than divide them isn’t popular with film academics right now, but a new generation of scholars is daring to say that there are universals of representation and response. It is these that allow movies to arouse similar emotions across times and places.

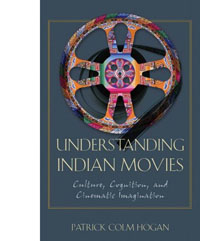

Patrick Hogan has made such a case in his fine new book Understanding Indian Movies: Culture, Cognition, and Cinematic Imagination. There he shows that much of what seems exotic in Indian cinema constitutes a local specification of factors that have a broad reach—certain plot schemes, themes, and visual and auditory techniques. Hogan, an expert in Indian history and culture, is ideally placed to balance universal appeals with matters of local knowledge that require explication for outsiders.

For my part, I’d just mention that a great deal of what seems striking in Slumdog has already been broached in Indian cinema. Take the matter of police brutality. The torture scene at the start might seem a piece of exhibitionism, with an outsider (Boyle? Beaufoy?) twisting local culture to western ideas of uncivilized behavior. But look again at the gangster films I’ve mentioned: they contain brutal scenes of police torture, like this from Company.

Like Hong Kong cinema and American cinema, Indian filmmaking seems to take a jaundiced view of how faithful peace officers are to due process.

More basically, consider the representation of the Mumbai slums. Doubtless the title slants the case from the first; Beaufoy claims to have invented the word “slumdog,” though Ram is called a dog at one point in the novel. The insult, and the portrayal of Mumbai, has made some critics find the film sensationalistic and patronizing. Most frequently quoted is megastar Amitabh Bachchan’s blog entry.

If SM projects India as [a] Third World dirty underbelly developing nation and causes pain and disgust among nationalists and patriots, let it be known that a murky underbelly exists and thrives even in the most developed nations.

Soon Bachchan explained that he was neutrally summarizing the comments of correspondents, not expressing his own view. In the original, he seems to have been suggesting that the poverty shown in Slumdog is not unique to India, and that a film portraying poverty in another country might not be given so much recognition.

It’s an interesting point, although many films from other nations portray urban poverty. More generally, Indian criticisms of the image of poverty in Slumdog remind me of reactions to Italian Neorealism from authorities concerned about Italy’s image abroad. The government undersecretary Giulio Andreotti claimed that films by Rossellini, De Sica, and others were “washing Italy’s dirty linen in public.” Andreotti wrote that De Sica’s Umberto D had rendered “wretched service to his fatherland, which is also the fatherland of . . . progressive social legislation.” Liberal American films of the Cold War period were sometimes castigated by members of Congress for playing into the hands of Soviet propagandists. It seems that there will always be people who consider films portraying social injustice to be too negative and failing to see the bright side of things, a side that can always be found if you look hard enough.

Moreover, Neorealists made a discovery that has resonated throughout festival cinema: feature kids. Along with sex, a child-centered plot is a central convention of non-Hollywood filmmaking, from Shoeshine and Germany Year Zero through Los Olvidados and The 400 Blows up to Salaam Bombay, numerous Iranian films, and Ramchandi Pakistani. Yes, Slumdog simplifies social problems by portraying the underclass through children’s misadventures, but this narrative device is a well-tried way to secure audience understanding. We have all been children.

There is another way to consider the poverty problem. The representation of slum life, either sentimentally or scathingly, can be found in classic Indian films of the 1950s. One of my favorites of Raj Kapoor’s work, Boot Polish (1954), tells a Dickensian tale of a brother and sister living in the slums before being rescued by a rich couple. (Interestingly, the key issue is whether to beg or do humble work.) Another example is Bimal Roy’s Do Bigha Zamin (Two Acres of Land, 1953). Later, shantytown life was more harshly presented in Chakra (1981), shot on location.

And of course poverty in the countryside has not been overlooked by Indian filmmakers.

Slumdog may have become a flashpoint because more recent Indian cinema has avoided this subject. In an email to me Patrick Hogan (who hasn’t yet seem Slumdog) writes:

There was a strong progressive political orientation in Hindi cinema in the 1940s and 1950s. This declined in the 1960s until it appeared again with some works of parallel cinema. Thus there was a greater concern with the poor in the 1950s–hence the movies by Kapoor and Roy that you mention. There are some powerful works of parallel cinema that treat slum life, but they had relatively limited circulation. On the other hand, that does not mean that urban poverty disappeared entirely from mainstream cinema. At least some sense of social concern seemed to be retained in mainstream Indian culture, thus mainstream cinema, until the late 1980s.

However, at that time Nehruvian socialism was more or less entirely abandoned and replaced with neo-liberalism. In keeping with this, ideologies changed. Perhaps because the consumers of movies became the new middle classes in India and the Diaspora, there was a striking shift in what classes appeared in Hindi cinema and how classes were depicted. As many people have noted, films of the neoliberal period present images of fabulously wealthy Indians and generally focus on Indians whose standard of living is probably in the top few percentage points. . . . I don’t believe this is simply a celebration of wealth and pandering to the self-image of the nouveau riche–though it is that. I believe it is also a celebration of neoliberal policies. Neoliberal policies have been very good for some people. But they have been very bad for others. . . .

However, at that time Nehruvian socialism was more or less entirely abandoned and replaced with neo-liberalism. In keeping with this, ideologies changed. Perhaps because the consumers of movies became the new middle classes in India and the Diaspora, there was a striking shift in what classes appeared in Hindi cinema and how classes were depicted. As many people have noted, films of the neoliberal period present images of fabulously wealthy Indians and generally focus on Indians whose standard of living is probably in the top few percentage points. . . . I don’t believe this is simply a celebration of wealth and pandering to the self-image of the nouveau riche–though it is that. I believe it is also a celebration of neoliberal policies. Neoliberal policies have been very good for some people. But they have been very bad for others. . . .

In this neoliberal cinema (sometimes misleadingly referred to as “globalized”), even relatively poor Indians are commonly represented as pretty comfortable. The difference in attitude is neatly represented by two films by Mani Ratnam—Nayakan (1987) and Guru (2007). The former is a representation of the difficulties of the poor in Indian society. The film already suffers from a loss of the socialist perspective of the 1950s films. Basically, it celebrates an “up from nothing” gangster for Robin Hood-like behavior. (This is an oversimplification, but gives you the idea.)

Guru, by contrast, celebrates a corrupt industrialist who liberates all of India by, in effect, following neoliberal policies against the laws of the government. Neither film offers a particularly admirable social vision. But the former shows the urban poor struggling against debilitating conditions. The latter simply shows a sea of happy capitalists and indicates that lingering socialistic views are preventing India from becoming the wealthiest nation in the world. Part of the propaganda for neoliberalism is pretending that poor people don’t exist any longer–or, if they do, they are just a few who haven’t yet received the benefits.

Paradoxically, then, perhaps local complaints against Slumdog arise because the film took up a subject that hasn’t recently appeared on screens very prominently. The same point seems to be made by Indian commentators and by Indian filmmakers who deplore the fact that none of their number had the courage to make such a movie. The subject demands more probing, but perhaps the outsider Boyle has helped revive interest in an important strain of the native tradition!

Finally, the issue of glamorizing the exotic. Some critics call the film “poverty porn,” but I don’t understand the label. It implies that pornography of any sort is vulgar and distressing, but which of these critics would say that it is? Most such critics consider themselves worldly enough not to bat an eye at naughty pictures. Some even like Russ Meyer.

So is the issue that the film, like pornography, prettifies and thereby falsifies its subject? Several Indian films, like Boot Polish, have portrayed poverty in a sunnier light than Slumdog, yet I’ve not heard the term applied to them. Perhaps, then, the argument is that pornography exploits eroticism for money, and Slumdog exploits Indian culture. Of course every commercial film could be said to exploit some subject for profit, which would make Hollywood a vast porn shop. (Some people think it is, but not typically the critics who apply the porn term to Slumdog.) In any case, once any commercial cinema falls under the rubric of porn, then the concept loses all specificity, if it had any to begin with.

The Slumdog project is an effort at crossover, and like all crossovers it can be criticized from either side. And it invites accusations of imperialism. A British director and writer use British and American money to make a film about Mumbai life. The film evokes popular Indian cinema in circumscribed ways. It gets a degree of worldwide theatrical circulation that few mainstream Indian films find. This last circumstance is unfair, I agree; I’ve long lamented that significant work from other nations is often ignored in mainstream US culture (and it’s one reason I do the sort of research I do). But I also believe that creators from one culture can do good work in portraying another one. No one protests that that Milos Forman and Roman Polanski, from Communist societies, made One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest and Chinatown. No one sees anything intrinsically objectionable in the Pang brothers or Kitano Takeshi coming to America to make films. Most of us would have been happy had Kurosawa had a chance to make Runaway Train here. Conversely, Clint Eastwood receives praise for Letters from Iwo Jima.

Just as there is no single and correct “Indian” or “American” or “French” point of view on anything, we shouldn’t deny the possibility that outsiders can present a useful perspective on a culture. This doesn’t make Slumdog automatically a good film. It simply suggests that we shouldn’t dismiss it based on easy labels or the passports of its creators.

Moreover, it isn’t as if Boyle and Tandan have somehow contaminated a pristine tradition. Indian popular films have long been hybrids, borrowing from European and American cinema on many levels. Their mixture of local and international elements has helped the films travel overseas and become objects of adoration to many westerners.

I believe we should examine films for their political presuppositions. But those presuppositions require reflection, not quick labels. If I were to sketch an ideological interpretation of Slumdog, I’d return to the issue of how money is represented in an economy that traffics in maimed children, virgins, and robotic employees. Money is filthy, associated with blood, death, and commercial corruption. The beggar barracks, the brothel, the call center, and the quiz show lie along a continuum. So to stay pure and childlike one must act without concern for cash. The slumdog millionaire doesn’t want the treasure, only the princess, and we never see him collect his ten million rupees. (An American movie loves to see the loser write a check.) To invoke Neorealism again, we seem to have something like Miracle in Milan–realism of local color alongside a plot that is frankly magical.

Perhaps this quality supports the creators’ claims that the film is a fairy tale. As with all fairy tales, and nearly all movies I know, dig deep enough and you’ll find an ideological evasion. Still, that evasion can be more or less artful and engrossing.

So it seems to me enlightening and pleasurable to see every film as suspended in a web, with fibers connecting it to different traditions, many levels and patches of film history. Acknowledging this shows that most traditions aren’t easily exhausted, and that fresh filmmaking tactics can make them live again. Thinking historically need not numb us to surprises.