Archive for the 'Readers’ Favorite Entries' Category

Grandmaster flashback

DB here:

Elsewhere I’ve sung the glories of Turner Classic Movies. Would that the other basic-cable staple, the Fox Movie Channel, were as committed to classic cinema. It’s curious that a studio with a magnificent DVD publishing program (the Ford boxed set, the Murnau/ Borzage one) is so lackluster in its broadcast offerings. Fox was one of the greatest and most distinctive studios, and its vaults harbor many treasures, including glossy program pictures that would still be of interest to historians and fans. Where, for instance, is Caravan (1934), by the émigré director Erik Charell who made The Congress Dances (1931)? Caravan‘s elaborate long takes would be eye candy for Ophuls-besotted cinephiles.

Occasionally, though, the Fox schedulers bring out an unexpected treat, such as the sci-fi musical comedy Just Imagine (1930). Last month, the main attraction for me was The Power and the Glory (1933), directed by William K. Howard from a script by Preston Sturges.

This was an elusive rarity in my salad days. As a teenager I read that it prefigured Citizen Kane, presenting the life of a tycoon in a series of daring flashbacks. I think I first saw it in the late 1960s at a William K. Everson screening at the New School for Social Research. I caught up with it again in 1979, at the Thalia in New York City, on a double bill with The Great McGinty (1940). In my files, along with my scrawls on ring-binder paper, is James Harvey’s brisk program note, which includes lines like this: “One of Sturges’ achievements was to make movies about ordinary people that never ever make us think of the word ‘ordinary.’” I was finally able to look closely at The Power and the Glory while doing research for The Classical Hollywood Cinema (1985). The UCLA archive kindly let me see a 16mm print on a flatbed viewer.

So after a lapse of twenty-eight years I revisited P & G on the Fox channel last month. It does indeed prefigure Kane, but I now realize that for all its innovations it belongs to a rich tradition of flashback movies, and it can be correlated with a shorter-term cycle of them. Rewatching it also teased me to think about flashbacks in general, and to research them a little. You see, I am very fond of what contemporary practitioners like to call broken timelines.

A trick, an old story

On our subject for today, the indispensible book, which ought to be brought back into print or archived online, is Maureen Turim’s Flashbacks in Film: Memory and History (Routledge, 1989). We may think of the flashback as a modern technique, but Turim shows that flashbacks have been a mainstay of filmic storytelling since the 1910s.

On our subject for today, the indispensible book, which ought to be brought back into print or archived online, is Maureen Turim’s Flashbacks in Film: Memory and History (Routledge, 1989). We may think of the flashback as a modern technique, but Turim shows that flashbacks have been a mainstay of filmic storytelling since the 1910s.

Although the term flashback can be found as early as 1916, for some years it had multiple meanings. Some 1920s writers used it to refer to any interruption of one strand of action by another. At a horse race, after a shot of the horses, the film might “flash back” to the crowd watching. (See “Jargon of the Studio,” New York Times for 21 October 1923, X5.) In this sense, the term took on the same meaning as then-current terms like “cut-back” and “switch-back.” There was also the connotation of speed, as “flash” was commonly used to denote any short shot.

But around 1920 we also find the term being used in our modern sense. You can find it in popular fiction; one short story has its female protagonist remembering something “in a confused flashback.” F. Scott Fitzgerald writes in The Beautiful and Damned of 1922:

Anthony had a start of memory, so vivid that before his closed eyes there formed a picture, distinct as a flashback on a screen.

At about the same time writers on theatre start to adopt the term and credit it to film. A historian of drama writes in 1921 of a play that rearranges story order:

The movies had not yet invented the flashback, whereby a thing past may be repeated as a story or a dream in the present.

Within film circles, there were signs of an exasperation with the device. One 1921 writer calls the flashback a “murderous assault on the imagination.” Turim quotes a New York Times review of His Children’s Children (1923):

For once a flash-back, as it is made in this photoplay, is interesting. It was put on to show how the older Kayne came to say his prayers.

In the same year, a critic discusses Elmer Rice’s On Trial, an influential 1911 stage play. Rice employs

a dramatic technique which up to its time was probably unique, though since then the ever recurrent “flash back” of the movies has made the trick an old story.

During the 1930s, although some critics and filmmakers employed older terms like “switch back” and “retrospect,” flashback seems to have become the standard label. It denoted any shot or scene that breaks into present-time action to show us something that happened in the past. It probably speaks to the intuitive and informal nature of filmmaking that writers and directors didn’t feel a need to name a technique that they were using confidently for two decades.

The early flashback films pretty much set the pattern for what would come later. Turim shows that all the sorts we find today have their precedents in the 1910s and 1920s. Adapting her typology a little bit, we can distinguish between character-based flashbacks and “external” ones.

A character-based flashback may be presented as purely subjective, a person’s private memory, as in Letter to Three Wives or The Pawnbroker or Across the Universe. There’s also the flashback that represents one character’s recounting of past events to another character, a sort of visual illustration of what is told. This flashback is often based on testimony in a trial or investigation (Mortal Thoughts, The Usual Suspects), but it may simply involve a conversation, as in Leave Her to Heaven, Titanic, or Slumdog Millionaire. It can also be triggered by a letter or diary, as happens with the doubly-embedded journals in The Prestige.

An alternative is to break with character altogether and present a purely objective or “external” flashback. Here an impersonal narrating authority simply takes us back in time, without justifying the new scene as character memory or as illustration of dialogue. The external flashback is uncommon in classic studio cinema (although see A Man to Remember, 1938) but was common in the 1900s and 1910s and has returned in contemporary cinema. Typically the film begins at a point of crisis before a title appears signaling the shift to an earlier period. Recent examples are Michael Clayton (“Three days earlier”), Iron Man (“36 Hours Before”), and Vantage Point (“23 Minutes Earlier”).

In current movies, flashbacks can fall between these two possibilities. Are the flashbacks in The Good Shepherd the hero’s recollections (cued by him staring blankly into space) or more objective and external, simply juxtaposing his numb, colorless life with the past disintegration of his family? The point would be relevant if we are trying to assess how much self-knowledge he gains across the present-time action of the film.

Rationales for the flashback

What purposes does a flashback fulfill? Why would any storyteller want to arrange events out of chronological order? Structurally, the answers come down to our old friends causality and parallelism.

Most obviously, a flashback can explain why one character acts as she or he does. Classic instances would be Hitchcock’s trauma films like Spellbound and Marnie. A flashback can also provide information about events that were suppressed or obscured; this is the usual function of the climactic flashback in a detective story, filling in the gaps in our knowledge of a crime.

By juxtaposing two incidents or characters, flashbacks can enhance parallels as well. The flashbacks in The Godfather Part II are positioned to highlight the contrasts between Michael Corleone’s plotting and his father’s rise to power in the community. Citizen Kane’s flashbacks are famous for juxtaposing events in the hero’s life to bring out ironies or dramatic contrasts.

Of course, flashbacks need not explain or clarify things; they can make things more complicated too. We tend to think of the “lying flashback” as a modern invention (a certain Hitchcock film has become the prototype), but Turim shows that The Goose Woman (1925) and Footloose Widows (1926) did the same thing, although not with the same surprise effect. Kristin points out to me that an even earlier example is The Confession (1920), in which a witness at a trial supplies two different versions of a killing we have already (sort of) seen.

At the limit, flashbacks can block our ability to understand characters and plot actions. This is perhaps best illustrated by Last Year at Marienbad, but the dynamic is already there in Jean Epstein’s La Glace à trois faces (“The Three-Sided Mirror,” 1927).

I argue in Poetics of Cinema that, at bottom, flashbacks are tactics fulfilling a broader strategy: breaking up the story’s chronological order. You can begin the film at a climactic moment; once the viewers are hooked, they will wait for you to move back to set things up. You can create mystery about an event that the plot has skipped over, then answer the question through a flashback. You can establish parallels between past and present that might not emerge so clearly if the events were presented in 1-2-3 order. Consequently, you can justify the switch in time by setting up characters as recalling the past, or as recounting it to others.

Having a character remember or recount the past might seem to make the flashback more “realistic,” but flashbacks usually violate plausibility. Even “subjective” flashbacks usually present objective (and reliable) information. More oddly, both memory-flashbacks and telling-flashbacks usually show things that the character didn’t, and couldn’t, witness.

I don’t suggest that recollections and recountings are merely alibis for time-juggling. They bring other appeals into the storytelling mix, such as allegiance with characters, pretexts for point-of-view experimentation, and so on. Still, the basic purpose of nonchronological plotting, I think, is to pattern information across the film’s unfolding so as to shape our state of knowledge and our emotional response in particular ways. Scene by scene and moment by moment, flashbacks play a role in pricking our curiosity about what came before, promoting suspense about what will happen next, and enhancing surprise at any moment.

A trend becomes a tradition

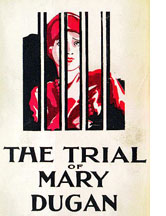

When The Power and the Glory was released in August 1933, it was part of a cycle of flashback films. The Trial of Mary Dugan (1929), The Trial of Vivienne Ware (1932), and other courtroom films rendered testimony in flashbacks. A film might also wedge a brief or extended flashback into an ongoing plot. The most influential instance was probably Smilin’ Through (1931), which is notable for using a crane shot through a garden to link present and past.

When The Power and the Glory was released in August 1933, it was part of a cycle of flashback films. The Trial of Mary Dugan (1929), The Trial of Vivienne Ware (1932), and other courtroom films rendered testimony in flashbacks. A film might also wedge a brief or extended flashback into an ongoing plot. The most influential instance was probably Smilin’ Through (1931), which is notable for using a crane shot through a garden to link present and past.

Also well-established was the extended insert model. Here we start with a critical situation that triggers a flashback (either subjective or external), and this occupies most of the movie. Digging around, I found these instances, but I haven’t seen all of them; some don’t apparently survive.

- Behind the Door (1919): An old sea salt recalls life in World War I and, back in the present, punishes the man responsible for his wife’s death. A ripoff of Victor Sjöström’s Terje Vigen (1917)?

- An Old Sweetheart of Mine (1923): A husband goes through a trunk in an attic and finds a memento that reminds him of childhood sweetheart. The pair grow up and marry, facing tribulations. At the end, back in the present, she comes to the attic with their kids.

- His Master’s Voice (1925): Rex the dog is welcomed home from the war. An extended flashback shows his heroic service for the cause, and back in the present he is rewarded with a parade.

- Silence (1926): A condemned man explains the events that led up to the crime. Back in the present, on his way to be executed, he is saved.

- Forever After (1926): On a World War I battlefield, a soldier recalls what brought him there.

- The Woman on Trial (1927): A defendant recalls her past.

- The Last Command (1928): One of the most famous flashback films of the period. An old movie extra recalls his life in service of the tsar.

- Mammy (1930): A bum reflects on the circumstances leading him to a life on the road.

- Such is Life (1931): A ghoulish item. A fiendish scientist confronts a young man with the corpse of the woman he loves. A flashback to their romance ensues.

- The Sin of Madelon Claudet (1931; often cablecast on TCM): A young wife bored with her husband is told the story of a neighbor woman who couldn’t settle down.

- Two Seconds (1932): A man about to be executed remembers, in the two seconds before death, what led him here. A more mainstream reworking of a premise of Paul Fejos’s experimental Last Moment (1928), which is evidently lost.

An interesting variant of this format is Beyond Victory, a 1931 RKO release. The plot presents four soldiers on the battlefield, each one recalling his courtship of the woman he loves back home. The principle of assembling flashbacks from several characters was at this point prised free of the courtroom setting, and multiple-viewpoint flashbacks became important for investigation plots like Affairs of a Gentleman (1934), Through Different Eyes (1942), The Grand Central Murder (1942), and of course Citizen Kane, itself a sort of mystery tale.

Why this burst of flashback movies? It’s a good question for research. One place to look would be literary culture. The technique of flashback goes back to Homer, and it recurs throughout the history of both oral and written narrative. Literary modernism, however, made writers highly conscious of the possibility of scrambling the order of events. From middlebrow items like The Bridge of San Luis Rey (1927) to high-cultural works by Dos Passos and Faulkner, elaborate flashbacks became organizing principles for entire novels. It’s likely that Sturges, a Manhattanite of wide literary culture, was keenly aware of this trend.

It’s just as likely that he noticed similar developments in another medium. By 1931, when Katharine Seymour and J. T. W. Martin published How to Write for Radio (New York: Longmans, Green), they could devote considerable discussion to frame stories and flashbacks in radio drama (pp. 115-137). Especially interesting for Sturges’ film, radio programs were letting the voice of the announcer or the storyteller drift in and out of the action that was taking place in the past.

For whatever reasons, the technique became more common. The year 1933 saw several flashback films besides The Power and the Glory. In the didactic exploitation item Suspicious Mothers, a woman recounts her wayward path to redemption. Mr. Broadway offers an extensive embedded story using footage from another film (a common practice in the earliest days). Terror Aboard begins with the discovery of corpses on a foundering yacht, followed by an extensive flashback tracing what led up the calamity. A borderline case is the what-if movie Turn Back the Clock (1933). Ever-annoying Lee Tracy plays a small businessman run down by a car. Under anesthesia, he reimagines his life as it might have been had he married the girl he once courted. Call it a rough draft for the “hypothetical flashbacks” that Resnais was to exploit in his great La Guerre est finie.

The point of this cascade of titles is that in writing The Power and the Glory, Sturges was working with a set of conventions already in wide circulation. His inventiveness stands out in two respects: the handling of voice-over and the ordering of the flashbacks.

Now I’m about to divulge details of The Power and the Glory.

Narratage, anyone?

The film begins with what became a commonplace opening gesture of film, fiction, and nonfiction biography: the death of the protagonist. We are at the funeral of Thomas Garner, railroad tycoon. His best friend and assistant Henry slips out of the service. After visiting the company office, Henry returns home. Sitting in the parlor with him, his wife castigates Garner as a wicked man. “It’s a good thing he killed himself.” So we have the classic setup of retrospective suspense: We know the outcome but become curious about what led up to it.

Henry’s defense of Garner launches a series of flashbacks. As a boyhood friend, Henry can take us to three stages of the great man’s life: adolescence, young manhood, and late middle age. Scenes from these time periods are linked by returns to the narrating situation, when Henry’s wife will break in with further criticisms of Garner.

Sturges boasted in a letter to his father: “I have invented an entirely new method of telling stories,” explaining that it combines silent film, sound film, and “the storytelling economy and the richness of characterization of a novel.” At the time, the Paramount publicists trumpeted that the film employed a new storytelling technique labeled narratage, a wedding of “narrating” and “montage.” One publicity item called it “the greatest advance in film entertainment since talking pictures were introduced.” Hyperbole aside, what did Sturges have in mind?

There is evidence that some screenwriters were rethinking their craft after the arrival of sound filming. Exhibit A is Tamar Lane’s book, The New Technique of Screen Writing (McGraw-Hill, 1936). Lane suggests that the talking picture’s promise will be fulfilled best by a “composite” construction blending various media. From the stage comes dialogue technique and sharp compression of action building to a strong climax. From the novel comes a sense of spaciousness, the proliferation of characters, a wider time frame, and multiple lines of action. Cinema contributes its own unique qualities as well, such as the control of tempo and a “pictorial charm” (p. 28) unattainable on the stage or page.

Vague as Lane’s proposal is, it suggests a way to think about the development of Hollywood screenwriting at the time. Many critics and theorists believed that the solution to the problem of talkies was to minimize speech; this is still a common conception of how creative directors dealt with sound. But Lane acknowledged that most films would probably rely on dialogue. The task was to find engaging ways to present it. Several films had already explored some possibilities, the most notorious probably being Strange Interlude (1932). In this MGM prestige product, the soliloquys spoken by characters in O’Neill’s play are rendered as subjective voice-over. The result, unfortunately, creates a broken tempo and overstressed acting. A conversation will halt, and through changes of facial expression the performer signals that what we’re now hearing is purely mental.

The Power and the Glory responds to the challenge of making talk interesting in a more innovative way. For one thing, there is the sheer pervasiveness of the voice-over narration. We’re so used to seeing films in which the voice-over commentary weaves in and out of a scene’s dialogue that we forget that this was once a rarity. Most flashback films in the early sound era had used the voice-over to lead into a past scene, but in The Power and the Glory, Henry describes what we see as we see it.

Most daringly, in one scene Henry’s voice-over substitutes for the dialogue entirely. Young Tom and Sally are striding up a mountainside, and he’s summoning up the nerve to propose marriage. What we hear, however, is Henry at once commenting on the action and speaking the lines spoken by the couple, whose voices are never heard.

This scene, often commented upon by critics then and now, seems have exemplified what Sturges late in life recalled “narratage” to be. Describing that technique in his autobiography, he wrote: “The narrator’s, or author’s, voice spoke the dialogue while the actors only moved their lips” (p. 272).

So one of Sturges’ innovations was to use the voice-over not only to link scenes but to comment on the action as it played out. In her pioneering book Invisible Storytellers: Voice-Over Narration in American Fiction Film (Univesity of California Press, 1988), Sarah Kozloff has argued that the pervasiveness of Henry’s narration has no real precedent in Hollywood, and few successors until 1939 (pp. 31-33). (There’s one successor in Sacha Guitry’s Roman d’un tricheur.) The novelty of the device may have led Sturges and Howard toward redundancies that we find a little labored today. The transitions into the past from the frame story are given rather emphatically, with Henry’s voice-over aided by camera movements that drift away from the couple. (Compare the crisp shifts in Midnight Mary, below.) Henry’s comments during the action are sometimes accentuated by diagonal veils that drift briefly over the shot, as if assuring us that this speech isn’t coming from the scene we see.

The “montage” bit of “narratage” also invokes the idea of a series of sequences guided by the voice-over narrator. The concept might also have encompassed the most famous innovation of The Power and the Glory: Sturges’ decision to make Henry’s flashbacks non-chronological.

Even today, most flashback films adhere to 1-2-3 order in presenting their embedded, past-tense action. But Sturges noticed that in real life people often recount events out of order, backing and filling or free-associating. So he organized The Power and the Glory as a series of blocks. Each block contains several scenes from either boyhood, youth, or middle age. Within each block, the scenes proceed chronologically, but the narration skips around among the blocks.

For example, a block of boyhood scenes gives way to a set showing Garner, now in middle age, ordering around his board of directors. The next cluster of flashbacks returns to Garner’s youth and his courtship of his first wife, Sally. Then we are carried back to his middle age, with scenes showing Garner alienated from Sally and his son Tommy but also attracted to the young woman Eve. And from there we return to Garner’s early married life with Eve.

To keep things straight, Sturges respects chronology along another dimension. Not only do the scenes within each block follow normal order, but the plotlines developing across the three phases of Garner’s life are given 1-2-3 treatment. In one block of flashbacks, we see Tom and Sally courting. When we return to that stage of their lives in another block, they are happily married. The next time we see Garner as a young man, he is improving himself by attending college. The later romance with Eve develops in a similar step-by-step fashion across the blocks devoted to middle age.

A major effect of the shuffling of periods is ironic contrast. Maureen Turim points out that seeing different phases of Garner’s life side by side points up changes and disparities. In his youth, Tom watches the birth of his son with awe; in the next scene, we are reminded what a wastrel young Tommy turned out to be.

The juxtaposition of time frames also nuances character development. As Sally ages, she turns into something of a nag, quarreling with her husband and pampering Tommy. But in the next sequence we see her young, ambitiously pushing Tom to succeed and willing to undergo sacrifice by taking up his job as a railroad track-walker. The next scenes show Tom in class and in a bar while Sally walks the desolate tracks in a blizzard. She has given up a lot for her husband. In the next scene, set in middle age, Garner confesses his love to Eve but says he could never leave Sally, and the juxtaposition with Sally’s solitary track-walking suggests that he recognizes her sacrifice. And in the following scene, when Sally comes to Garner’s office, she admits that she has become disagreeable and asks if they couldn’t take a trip to reignite their love. The juxtaposition of scenes has turned a caricatural shrew into a woman who is a more complex mixture of devotion, disenchantment, and self-awareness.

Other characters aren’t given this degree of shading—Tommy is pretty much a wastrel, Eve a vamp—but another married couple deepens the central parallel. Meek Henry is dominated by his wife, but by the end she is chastened by what she learns of Garner’s real motives. Critic Andy Horton, in his helpful introduction to Sturges’ published screenplay, indicates that this couple adds a note of contentment to what is otherwise a pretty sordid melodrama of adultery and quasi-incest.

The innovative flashbacks and voice-overs are an important part of the film’s appeal, but director William K. Howard supplied some craftsmanship of his own. Particularly striking are some silhouette effects, low angles, and deep-focus compositions that underscore the parallels between Sally’s suicide and Garner’s impending death.

The original screenplay suggests that Sturges intended to push his innovations further. About halfway through, he starts to break down the time-blocks. In the script, Sally visits Garner while he’s working on a bridge. The next scene shows their son Tommy already grown and spoiled, being taken back into his father’s good graces. Then the script returns to the bridge, where Sally tells Tom she’s pregnant. The interruption of the bridge scene reminds us of how badly their child turned out.

The script jumps back to the birth of the baby. In the film the birth scene plays out in its entirety, but in the screenplay Sturges cuts it off by the scene (retained in the film) showing Garner’s marriage to Eve. The final moments of the birth scene, when Garner prays (“Thou art the power and the glory”), become in the script the very end of the film. Coming after Tom’s death at the hand of his son, this epilogue is a bitter pill, rendered all the harder to take by providing no return to Henry and his wife.

The greater fragmentation of the second part of the script, along with Garner’s death as a sort of murder-suicide and the failure to return to the narrating frame, is striking. It’s as if Sturges felt he could take more chances, counting on his viewers’ familiarity with current flashback conventions and on his film’s firmly established time-shuttling method. But if, as sources report, Sturges’ script was initially filmed exactly as written, then it seems likely that the film’s June 1933 preview provoked the changes we find in the finished product. “The first half of the picture,” he remarked in a letter, “went magnificently, but the storytelling method was a little too wild for the average audience to grasp and the latter half of the picture went wrong in several spots. We have been busy correcting this and the arguments and conferences have been endless.”

Even the compromised film proved difficult for audiences. Tamar Lane, proponent of the “composite” form suitable for the sound cinema, felt that the “retrospects” in The Power and the Glory were too numerous and protracted. Nonetheless, he praised it for its “radical and original cinema handling” (p.34). That handling rested upon tradition—a tradition that in turn encouraged innovations. Once flashbacks had become solid conventions, Sturges could risk pushing them in fresh directions.

Mary remembers

Finally, two more flashy flashback movies from 1933. Some spoilers.

Midnight Mary (MGM, William Wellman) works a twist on the courtroom template. The defendant Mary Martin is introduced jauntily reading a magazine while the prosecutor demands that the jury find her guilty of murder. This also sets up a nice little motif of shots highlighting Loretta Young’s lustrous eyes. The motif pays off with a soft-focus shot of her in jail just before the climax.

As the opening scene ends, Mary is led to a clerk’s office to wait for the verdict. There’s an automatic dose of suspense (Will she be found guilty?) but there’s also considerable curiosity: Whom has she killed? How was she caught?

These questions won’t be answered for some time. Lounging in the clerk’s office, Mary runs her eye runs across the annual reports filling his shelves. The flashbacks, which comprise most of the film, are introduced as close-ups of the volumes’ spines—1919, 1923, 1926, 1927, and so on up to the present. They serve as neatly motivated equivalents of those clichéd calendar pages that ripple through montage sequences of the 1930s.

The flashbacks are motivated as subjective; Mary doesn’t recount her life to the clerk but simply reviews it in her mind. Unlike the flashbacks in The Power and the Glory, they are chronological and without gaps. Nothing is skipped over to be revealed later. As usual, though, once Mary’s recollections have triggered the rearrangement of story order, the flashbacks are filmed as any ordinary scenes would be, including bits of action that she isn’t present to witness. The film is a good example of using the extended-flashback convention chiefly to delay the resolution of the climactic action. Told in chronological order, Mary’s tale of woe would have had much less suspense.

Transitions between present and past are areas open to innovation, and early sound filmmakers took advantage of them. In Midnight Mary, the long flashback closes with gangsters pounding on the door of Mary’s boudoir; this sound continues across the dissolve to the present, with Mary roused from her reverie by a knock on the clerk’s office door. Earlier, one transition into the past begins with Mary blowing cigarette smoke toward the bound volumes on the shelf.

Dissolve to a close-up of one book as smoke wafts over it, and then to a shot of Mary’s gangster boyfriend blowing cigarette smoke out before he sets up a robbery..

At one point the narration supplies a surprise by abruptly shifting into the present. Once Mary has become a prostitute, she is slumped over a barroom table in sorrow, while her pal Bunny consoles her. In a tight shot, Bunny (Una Merkel, always welcome), leans over and says: “Oh, what’s the diff, Mary? A girl’s gotta live, ain’t she?”

Cut directly to the present, with Mary murmuring: “Not necessarily, Bunny. The jury’s still out on that.”

Mary’s reply casts Bunny’s question about needing to live in a new light, since Mary is facing execution, and the use of the stereotyped phrase, “The jury’s still out,” now with a double meaning, reminds us of the present-tense crisis. It is a more crisp and concise link than the transitions we get in The Power and the Glory. But then, Wellman has no need for continuous voice-over, which gives the Sturges/ Howard film its more measured pace.

Filmmakers were concerned with finding storytelling techniques appropriate to the sound film, and these unpredictable links between sequences became characteristic of the new medium. Similar links had appeared in silent films, but they gained smoothness and extra dimensions of meaning when the images were blended with dialogue or music. For more on transitional hooks, go here.

Nora and narratage

The hooks between scenes are perhaps the least outrageous stretches of The Sin of Nora Moran, a Majestic release that, thanks to a gorgeous restoration and a DVD release, has rightly earned a reputation as the nuttiest B-film of the 1930s.

It is a flashback frenzy, boxes within boxes. A District Attorney tells the governor’s wife to burn the apparently incriminating love letters she’s found. In explaining why, the D. A. introduces a flashback (or is it a cutaway?) to Nora in prison. We then move into Nora’s mind and see her hard life, the low point occurring when she’s raped by a lion tamer.

Now we start shuttling between the D. A. telling us about Nora and Nora remembering, or dreaming up, traumatic events. At some points, characters in her flashbacks tell her that what she’s experiencing is not real. In one hazy sequence, her circus pal Sadie materializes in her cell to remind Nora that she killed a man. (Actually, she didn’t.) At other moments Nora’s flashbacks include moments in which she says that if she does something differently, it will change—it being the outcome of the story. At this point another character will point out that they can’t change the outcome because it has already happened . . . of course, since this is a flashback.

By the end, after the governor has had his own flashback to the end of his affair with Nora and after she appears as a floating head, things have gotten out of hand. The rules, if there are any, keep changing. And the whole farrago is propelled by furious montage sequences built out of footage scavenged from other films.

Publicity and critical response around The Sin of Nora Moran implied that the movie followed the “narratage” method. There was surely some influence. Scenes contain fairly continuous voice-over commentary, and director Phil Goldstone occasionally drops in the diagonal veil used in The Power and the Glory. But on the whole this delirious Poverty Row item falls outside the strict contours of Sturges’ experiment. Nora Moran blurs the line separating flashbacks and fantasy scenes, and it illustrates how easily we can lose track of what time zone we’re in. Watching it, I had a flashback of my own—to Joseph Cornell’s Rose Hobart, another compilation revealing that Hollywood conventions are only a few steps from phantasmagorias.

Unwittingly, Nora Moran’s peculiarities point forward to the flashback’s golden age, the 1940s and early 1950s. Then we got contradictory flashbacks, flashbacks within flashbacks within flashbacks, flashbacks from the point of view of a corpse (Sunset Boulevard) or an Oscar statuette (Susan Slept Here). Filmmakers knew they had found a good thing, and they weren’t going to let it go.

The original screenplay of The Power and the Glory is included in Andrew Horton, ed., Three More Screenplays by Preston Sturges (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998). Sturges’ reflections from the late 1950s are to be found in Preston Sturges by Preston Sturges: His Life in His Words, ed. Sandy Sturges (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1990). The quotations from Sturges’ letters and from publicity about “narratage” can be found in Diane Jacobs, Christmas in July: The Life and Art of Preston Sturges (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992), 123-129 and James Curtis, Between Flops: A Biography of Preston Sturges (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1982), 87.

My citatations of literary uses of the term come from Elliott Field, “A Philistine in Arcady,” The Black Cat 24, 10 (July 1919), 33; Fitzgerald’s The Beautiful and Damned (1922), available here, 433; Samuel A. Eliot, Jr., ed., Little Theater Classics vol. 3 (Boston: Little, Brown, 1921), 120; The Outlook (11 May 1921), 49, available here; review of His Children’s Children, quoted in Turim p. 29; commentary on On Trial, in The New York Times (25 March, 1923), X2.

For more on the history of flashback construction, apart from Maureen Turim’s Flashbacks in Film, see Barry Salt’s Film Style and Technology: History and Analysis, 2nd ed. (London: Starword, 1992), especially 101-102, 139-141. There are discussions of the technique throughout David Bordwell, Janet Staiger, and Kristin Thompson, The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1985), especially 42-44.

P.S. 15 November 2015: 1940s flashback technique is surveyed in my Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling.

Bugs: The secret history

DB here:

One of the many penalties of watching movies on TV is the prevalence of bugs.

This is the nickname adopted by media makers for those little channel logos and watermarks that hop onto your screen. Sometimes these translucent signatures surface at intervals, to minimally satisfy FCC channel identification demands. Others let you know the movie you’re watching, or will be later.

But just as often the bugs just squat in a corner forever, teasing your eye away from the movie. Bugs are to the 2000s what editing and time-compressing were to earlier eras. “Movies, uncut,” boasts the IFC bug. But not unspoiled.

Bugs are bad enough when they are hovering in a black vacuum, made forlorn by letterboxing.

But they really jump into competition when they take up part of the image. How can you watch what actors are doing when there’s something faintly readable floating up from below?

I find it impossible not to look at a bug occasionally. In dark shots, sometimes it’s the most visible thing on the screen. Even in bright shots I stare at it. Maybe I’m hoping that it will be different this time. Yet when it changes, as it does on the Lifetime channel, I watch it more attentively, which only makes me more annoyed.

It’s like the mesmeric spell of Time Code, ticking away the movie’s life, and yours.

I’m not the first to complain. An eloquent manifesto, originally called Squash the Bugs, dates back to 2000, when the infestation was starting. Several other souls participated in the movement.

We know why bugs are swarming all over TV. Somebody better dressed than you or me is worried that we will be recording A Christmas Story or Smokey and the Bandit or Stranger in My Bed. We might even try to sell copies, or post a clip online. In principle, the bug is a badge of ownership, warning that we could be prosecuted. In practice, nobody expects to sue every user, so bugs help spread the brand. It’s like putting a designer logo on a shirt, making you a walking ad. Who wouldn’t want their bug, microscopic as it is, all over YouTube (which of course tacks on its own bug)?

But like everything else that we take for granted, bugs aren’t new. In their earlier form, they’re rather likable.

Silent but deadly

Movie bugs go back to the first years of cinema, when producers were no less worried about media piracy than they are today. Between 1895 and 1915, films circulated very freely around the world, and enterprising crooks happily duped originals and passed them off as their own productions. To block this, filmmakers tried to find ways to keep their trademarks on the film.

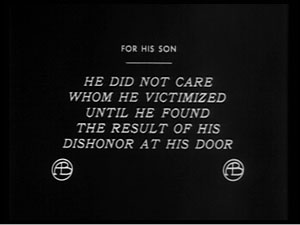

The obvious step was to put the trademark in the intertitles, and many companies did. Here is one for For His Son, a 1912 Griffith film from American Biograph. (What did the protagonist do for his son? He created a soft drink called Dopocoke, which turns the college boy into a hopeless addict.) Note the handsome AB insignia.

But of course a pirate could simply replace such original titles with ones of his own. The next logical step was to incorporate the trademark into the images, which couldn’t be replaced. Without the technology to create near-invisible superimpositions, the filmmakers took the obvious course.

They put the company logo into the set.

The AB circle typically appeared as a wall decoration. Biograph characters loved to furnish their surroundings to highlight this motif, preferring to put it at eye level and frame center. The logo could be found in unexpected places, like movie theatres (Those Awful Hats, 1908), and it could brighten the dreariest hovel (What Shall We Do with Our Old?, 1911).

The plaque’s popularity stretched back to Civil War days (In the Border States, 1910), and even in medieval times a king might mount the stylish AB on a brick wall (The Sealed Room, 1909).

Not to be outdone, Biograph’s competitor, the Vitagraph company, had a beautiful soaring eagle logo, which conveniently furnished a striking V graphic.

Judging from the evidence of this 1908 film, however, Vitagraph had a sideline in manufacturing safes.

The practice of building the trademark into the mise-en-scene seems to have begun in France. Georges Méliès, whose fantasy films were popular around the world, took measures to counter piracy early. You can see his Star-Film logo on the building stone in the left corner of this frame from La Danseuse microscopique (1902). Shift it to the right corner and we’d have a modern-day bug.

At the very top of this entry is a frame from Le Voyage de Gulliver à Lilliput et chez les géants (1902). There Méliès attached the Star-Film seal to the barrel sitting just left of center.

At the very top of this entry is a frame from Le Voyage de Gulliver à Lilliput et chez les géants (1902). There Méliès attached the Star-Film seal to the barrel sitting just left of center.

But Méliès didn’t always shove his imprimatur to the edge of the frame. In Le Tonnerre de Jupiter (1903) it sits just below the eagle that Zeus bestrides.

In the earlier Diable au convent (1899), Méliès exercised another option, simply signing his image as if it were a painting. To a large extent, it was.

Léon Gaumont had two marques, each enclosed in a chrysanthemum ring. The most famous one is a majestic Gaumont, but an alternative, ELGE (that is, LG), haunts Alice Guy’s Billet de banque (1907). First, in a café, the logo is attached to a table, and later it’s a decorative baseboard in a police station.

In Guy’s Le Frotteur (1907), Gaumont simiply stuck its logo to a chair leg.

Then there’s the Pathé Frères rooster.

Easy enough to embed that, you’d think. Just have a rooster stroll through a shot now and then—not only barnyard scenes, but ones set in a courtroom or a factory. Still, roosters are pretty accessible to any film pirate, so Pathé went the more ordinary route of weaving its logo into the set.

An insistent example comes in The Physician of the Castle (1907), possibly the source for Griffith’s The Lonely Villa (1908) and Lois Weber/ Phillips Smalley’s Suspense (1913). The plot is sort of a 1907 Panic Room. The logo is initially a plaque in the parlor of the castle, visible just behind the kneeling doctor.

An identical plaque is perched in nearly the same spot on the wall of the doctor’s own parlor, as we can tell when his family is besieged by the invading tramps.

The tramps pass through another room, where the trademark stands proudly on another wall, on screen right.

And when the wife tries to phone the husband for help, we get an insert that shows the Pathé cock nearly perched on her shoulder.

Why do I find the old bugs charming and the new ones annoying? I suppose it’s partly because the old ones were hand-crafted, not the result of keyboard twiddling. They are tangible. They are part of the scene’s space. Hard to see on DVD, the embedded marques are striking in 35mm projection, and spotting them is part of the pleasure of early film. Moreover, the filmmakers intended them to be there, or at least they accepted the need for them. But what director today is happy when the Sundance bug creeps into her compositions?

The old bugs seem to have gone extinct around 1912, but they will cling to their films. They bear witness to filmmaking of a specific time, and they anticipate problems that persist today. In tackling the threat of piracy, the old bugs seem at once naïve and intelligent. I see them as a rational solution to a hard problem, narrative consistency be damned. Today’s bugs, floating on top of the story world, seem more like corporate tattoos or graffiti. They don’t exist within the action, so you could argue that they are less disruptive. But they become a different sort of distraction, hovering halfway between the story world and the space of viewing. Bugs are spectres haunting the film.

On rare occasions, a modern add-on can be appropriate. In a Méliès film on the recent Flicker Alley set, L’Oracle de Delphes (1903), some TV agency has clapped its own digital bug into the lower right corner. It really is about beetle-size, and it dares to be a single eye looking back at you. That icon adds a touch of peculiarity not out of keeping with the Méliès aesthetic.

You can argue that this smirch on the image is a minor sacrilege. But I suspect that the Master of Montreuil would have grinned in approval.

For more on bugs, aka DOGS (Digital Onscreen Graphics), see Wikipedia. Thanks to Jason Mittell for helping me name these pests. And all hail Turner Classic Movies for keeping its bugs to a minimum.

The Sunbeam (Griffith, American Biograph, 1912).

PS 19 January 2009: “Subliminal” bugs: I had hoped to include a frame illustrating the anti-piracy stamp used on current 35mm releases, but couldn’t find one quickly. This mark consists of a tight pattern of dots resembling a character in Braille. The stamp would presumably be copied if someone shot off the screen or ran the film through a telecine. How effective these bugs are at tracing pirate copies I can’t say, but you can detect them, especially in bright scenes; I usually notice one every third reel or so, just left of the center of the frame. I’ll keep looking for a frame and try to add one to this entry.

John Powers alerted me to the fact that even Michael Snow’s Région Centrale got the bug treatment when it was telecast on Italy’s RAI 3 TV. Thanks to John for this scary example.

P.P.S. 24 January 2009: On the Internets, ask and ye shall receive. Olli Sulopuisto wrote to link me to the Wikipedia entry explaining the domino dots, known as CAPs. The entry includes an illustration. Olli also contributed to Jim Emerson‘s scanners blog, which contains good commentary on CAPs from Jim and his readers.

P.P.P.S. 29 May 2013: Can anti-piracy bugs be integrated into the movie or TV show? Yes!

Gradation of emphasis, starring Glenn Ford

DB here:

Charles Barr’s 1963 essay “CinemaScope: Before and After” has become a classic of English-language film criticism. (1) It proffers a lot of intriguing ideas about widescreen film, but one idea that Barr floated has more general relevance. I’ve found it a useful critical tool, and maybe you will too.

Grading on a curve

Barr called the idea gradation of emphasis. Here’s what he says:

The advantage of Scope [the 2.35:1 ratio] over even the wide screen of Hatari! [shot in 1.85:1] is that it enables complex scenes to be covered even more naturally: detail can be integrated, and therefore perceived, in a still more realistic way. If I had to sum up its implications I would say that it gives a greater range for gradation of emphasis. . . The 1:1.33 screen is too much of an abstraction, compared with the way we normally see things, to admit easily the detail which can only be really effective if it is perceived qua casual detail.

The locus classicus exemplifying this idea comes in River of No Return (1954). When Kay is lifted off the raft, she loses her grip on her wickerwork bag and it’s carried off by the current. (See the frame surmounting this entry.) Kay and her boyfriend Harry are rescued by the farmer Matt. As all three talk in the foreground, the camera catches the bundle drifting off to the right.

Even when the men turn to walk to the cabin, Preminger gives us a chance to see the bundle still drifting downstream, centered in the frame.

The point of this shot, Barr and V. F. Perkins argued, is thematic. As Kay moves from the mining camp to the wilderness, she will lose more and more of her dance-hall trappings and be ready to accept a new life with Matt and Mark. The last shot of the film shows her final traces of her old life cast away.

Cutting in to Kay’s floating bag would have been heavy-handed; if you stress a secondary element too much, it becomes primary. Barr reminds us that any film shot can include the most important information, as well as information of lesser significance. A film can achieve subtle effects by incorporating details in ways that make them subordinate as details and yet noticeable to the viewer. Or at least the alert viewer.

In Poetics of Cinema, I wrote an essay on staging options in early CinemaScope, and Barr’s idea helped me illuminate some of the strategies I discuss. (For earlier comments on Barr on Scope and River of No Return, see my article elsewhere on this site.) Today I want to consider how the notion of gradation of emphasis has a more general usefulness.

Barr contrasts the open, fluid possibilities of CinemaScope with two other stylistic approaches, both found in the squarer 1.33 format. The first approach is the editing-driven one he finds in silent film. This tends to make each shot into a single “word,” and meaning arises only when shots are assembled. Barr associates this approach with Griffith and Eisenstein. The second approach, only alluded to, is that of depth staging and deep-focus shooting, typically associated with sound cinema of the late 1930s and into the 1950s.

Both of these approaches, montage and single-take depth, lack the subtle simplicity of Scope’s gradation of emphasis.

There are innumerable applications of this [technique] (the whole question of significant imagery is affected by it): one quite common one is the scene where two people talk, and a third watches, or just appears in the background unobtrusively—he might be a person who is relevant to the others in some way, or who is affected by what they say, and it is useful for us to be “reminded” of his presence. The simple cutaway shot coarsens the effect by being too obvious a directorial aside (Look who’s watching) and on the smaller [1.33] screen it’s difficult to play off foreground and background within the frame: the detail tends to look too obviously planted. The frame is so closed-in that any detail which is placed there must be deliberate—at some level we both feel this and know it intellectually.

To see Barr’s point, consider a shot like this one from Framed (1947).

The shot, rather typical of 1940s depth staging, displays an almost fussy precision about fitting foreground and background together. That bartender, for instance, stands squeezed into just the right spot. (2) Barr claims that we sense a certain contrivance when primary and secondary centers of interest are jammed into the 1.33 frame like this.

We don’t sense the same contrivance in the widescreen format, he suggests. Barr assumes, I think, that the sheer breadth of any Scope frame will include areas of little consequence, whereas that’s comparatively rare in a 1.33 composition. This is an intriguing hunch, but uninformative patches of the frame may not be intrinsic to the Scope technology. Perhaps the fairly neutral and inexpressive uses of Scope that dominate the early 1950s, the sense of empty and insignificant acreage stretching out on all sides, make us expect that little of importance will be found there. Accordingly, directors can create a sense of discovery when we spot a significant detail in this stretch of real estate.

Anyhow, Barr indicates that if static deep-space staging made the frame too constrained, 1930s and 1940s directors who combined depth with camera movement created more spacious and fluid framings. He suggests that Mizoguchi, Renoir, and others anticipated the possibilities of Scope.

Greater flexibility was achieved long before Scope by certain directors using depth of focus and the moving camera (one of whose main advantages, as Dai Vaughan pointed out in Definition 1, is that it allows points to be made literally “in passing”). Scope as always does not create a new method, it encourages, and refines, an old one (pp. 18-19).

Barr believes that Scope positively encouraged gradation of emphasis, and that widescreen directors of the 1950s and 1960s have made the most fruitful use of the strategy. But he allows directors of all periods utilized gradation of emphasis, even in the standard 1.33 format. This is, I believe, a powerful idea.

Before Scope: Making the grade

Barr’s discussion of silent cinema, relying on notions of editing associated with Griffith and Soviet directors like Eisenstein, is done with a broad brush, but it’s typical of the period in which he was writing. We didn’t know much about silent filmmaking until archivists started to exhume important work in the 1970s. It’s no exaggeration to say that we haven’t really begun to understand the first twenty-five years of cinema until fairly recently.

In a way, the staging-driven tradition of the 1910s, which I’ve often mentioned on this site (here and here and here), exemplifies some things that Barr would approve of. Directors of that period made extraordinary use of the frame and compositional patterning. They staged action laterally, in depth, or both. They let shots ripen slowly or burst with new information. This approach to using the full frame (with only occasionally cut-in elements) has come to be called the tableau style, emphasizing its similarity to composition of a painting—although we shouldn’t forget that these films are moving paintings, and the compositions are constantly changing. The result is that emphasis tends to be modulated and distributed among several points of interest.

Central to this strategy, I think, was camera distance. American directors tended to set the camera moderately close, cutting figures off at the knees or hips, and by taking up more frame space, the foreground actors tended to limit the area available for depth arrangement or for significant detail.

This shot from Thanhouser’s The Cry of the Children (1912) is a rough 1910s equivalent of the crammed shot from Framed above. (See also the tightly composed shots from DeMille’s Kindling (1915) here.)

The European directors, by contrast, tended to let the scene play out in more distant shots, creating spacious framings of a sort that would be reinstituted in early CinemaScope. Consider this shot from Holger-Madsen’s Towards the Light (Mod Lyset, 1919) and another from Island in the Sun (1957).

Both, it seems to me, have the type of open composition and the foreground/ background interplay that Barr praises in his article.

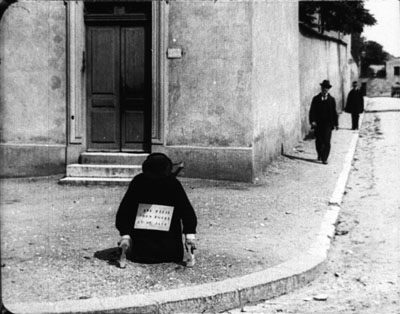

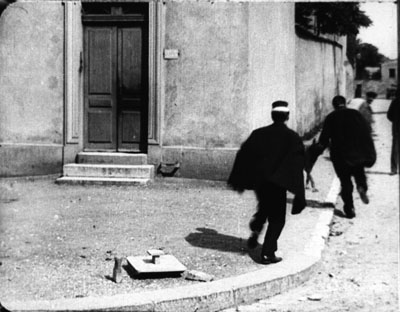

We can go back further. The Lumière brothers’ cameramen made fiction films as well as documentaries, and we occasionally find moments that suggest early efforts at gradation of emphasis. In Le Faux cul-de-jatte (1897), an apparent amputee is begging in the foreground while in the distance a man is walking down the street.

A cop crosses the street from off right and follows the pedestrian.

As the foreground fills up, the man we’ve seen in the distance gives the beggar some money.

As he goes out left, the cop is still approaching, and a vagrant dog appears.

The cop comes to the beggar, partially blocking the dog, who takes care of other business. (Not everything in this movie is staged.)

The cop checks the beggar’s papers and finds them to be suspect. The fake amputee jumps up and races off in the distance, with the cop pursuing.

As with many staged Lumière shorts, several figures converge in the foreground in order to create a culminating piece of action. Here the distant man and the cop, both secondary centers of interest, serve as a kind of timer, assuring us that something will happen when they meet at the beggar.

These are just some quick examples. We should continue to study the ways in which, with minimal use of editing, early filmmakers found ingenious ways to create gradation of emphasis. (2)

Some uses of grading

Barr, like most critics writing for the British journal Movie, was sensitive to the ways in which technique has implications for character psychology and broader thematic meanings. Kay’s bundle is one point along a series of changes in her character and her situation. But gradation of emphasis can serve more straightforward narrative purposes as well.

Consider our old friends, surprise and suspense. In the original 3:10 to Yuma (1957) Dan Evans is confronting the ruthless outlaw Ben Wade.

We get a string of reverse shots.

Then in one shot of Wade, without warning, a shadowy figure emerges out of focus in the left background.

Now we realize that Evans has been diverting Wade from the fact that the sheriff’s posse is surrounding him. Now we wait for Wade to discover it; how will he react?

While we’re on Glenn Ford, another nice example occurs in Framed. Mike Lambert has been romancing a woman named Paula, but we know that she and her lover Steve are plotting to fake Steve’s death and substitute Mike’s body.

She brings Mike to Steve’s elegant country house, having presented Steve as someone she knows only slightly. When Mike goes into the bathroom to wash up, we notice something important behind him.

With Mike at the sink, we have plenty of time to recognize Paula’s robe. Director Richard Wallace prolongs the suspense by giving us a new shot of Mike in the mirror, with the robe no longer visible.

But when Mike turns to leave, a pan following him brings him face to face with what we saw, accentuated by a track forward.

We get Mike’s reaction shot, followed by a cut to Steve and Paula downstairs, suspecting nothing. “So far, so good,” says Steve, looking upward at the bathroom.

The rest of the scene will play out with Mike aware that they’re deceiving him. As often happens with suspense, we know more than any one character: We know the couple’s scheme and Mike doesn’t, but they don’t (yet) know that Mike is now on his guard.

This isn’t as subtle a case as River of No Return, but I suspect that it’s more typical of the way Hollywood filmmakers use gradation of emphasis. Paula’s bathrobe is a good example of what I called in The Classical Hollywood Cinema the strategy of priming: planting a subsidiary element in the frame that will take on a major role, even if initially its presence isn’t registered strongly. My example in CHC was a coat rack in the Dean Martin/ Jerry Lewis comedy The Caddy (1953). In effect, the distant pedestrian in the Lumière film is an early example of priming.

Howard Hawks adopts the Lumière technique in order to sustain a flow of dialogue in Twentieth Century (1934). Here the foreground conversation is accompanied by a procession of people emerging in the distance and stepping up to take part.

The shot concludes, as does the shot of Faux cul-de-jattes, with a retreat from the camera.

The priming of secondary elements here, the summoning of the train attendant and the conductor, obeys Alexander Mackendrick’s dictum that the director ought to construct each shot so as to prepare for what will come next.

As Barr indicates, the idea of gradation shades insensibly off into general matters of cinematic expression. In The Devil Thumbs a Ride (1947), the bank robber has hitched a ride with an unassuming civilian, and they stop for gas. When the attendant shows a picture of his little girl, the robber gratuitously insults her. (“With those ears she’ll probably fly before she can walk.”)

Later, the station attendant hears a radio broadcast describing the fugitive. First he has his head cocked as he listens attentively, but then his gaze drifts to the picture of his little girl.

The attendant is the center of dramatic interest, but when he looks at the picture, so do we (primed by the view of it earlier). Instantly we understand that the attendant’s resolve to call the police springs partly from an urge to get even with the man who insulted his daughter. A minor instance, surely, but it illustrates Barr’s point that the notion of gradation of emphasis leads us to consider “the whole question of significant imagery.”

The more the merrier

Barr seems to favor a plain style; he prefers Preminger’s quiet framings to the rococo imagery of Aldrich’s Vera Cruz (1954). Presumably the famous shot above from Wyler’s Best Years of Our Lives (1946) would be too obviously composed for Barr’s taste.

But there is merit in considering how a secondary center of interest can vie for supremacy. André Bazin declared Wyler’s shot a bold stroke exactly because its self-conscious precision created a tension between what was primary and what was subordinate. (3) The action in the foreground is of dramatic interest because Homer has learned to play the piano, and this represents a phase of his coming to terms with his wartime disability. Yet the most consequential action is taking place in the distant phone booth, where Fred breaks up with Al’s daughter Peggy. The gradation of emphasis is inverted, and we wait in suspense to find out what happens. Bazin taught us to recognize that what appears to be primary may actually be creatively distracting us from the scene’s principal action. (4)

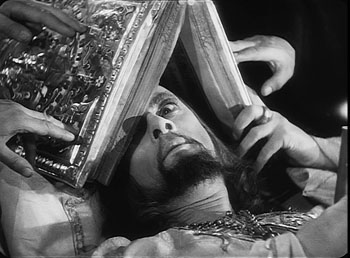

A director can also turn a primary center of interest into something secondary, but powerful. In one sequence of Eisenstein’s Ivan the Terrible I (1944), the apparently dying tsar is being prayed over by churchmen. Ever suspicious, he peers out from under the book, using only one eye.

As the scene develops, Prince Kurbsky meets Ivan’s wife and tries to seduce her. In the background an icon’s eye glares out, as if Ivan is watching them.

The single eye, which is a motif we find in other Eisenstein films, becomes a significant one throughout both parts of Ivan. More generally, this device manifests Eisenstein’s conception of polyphonic montage, which explored how the filmmaker can control all the various aspects of his images and make them weave throughout the film—promoting one at one moment, demoting it at another. (5)

Barr’s essay assumes that Eisenstein’s montage stripped each image down to a single meaning. In fact, though, Eisenstein wanted to multiply the sensuous and intellectual implications of each shot by weaving objects, gestures, body parts, musical motifs, and the like into an ongoing stylistic fabric. Each shot’s gradation of emphasis can suggest thematic parallels, deepen the drama, or heighten emotional expression, just as a complex score enhances an operatic scene.

Tati as well likes to create an interplay between primary and subsidiary centers of interest. Or rather, he sometimes abolishes our sense of what is primary and what isn’t. The crowded compositions of Play Time (1967) often bury their gags in a welter of inessential details. During the lengthy scene in the Royal Garden restaurant, a minor running gag involves the dyspeptic manager. He has just mixed some headache medicine with mineral water, but the action is easily lost within the tumultuous image. Even the soundtrack cues us only slightly, with a bit of fizz among the music and crowd noise.

As the manager lowers the glass, Hulot thinks it’s pink champagne being offered to him.

Rolling the stuff in his mouth, Hulot realizes his mistake as he earns a stare from the manager.

There is so much competing sound and activity in the shot that some viewers simply don’t notice this bit at all. In Play Time, gradation of emphasis is often flattened out, leaving us to rummage around the composition for the gag.

Some final notes

Barr was not particularly interested in the mechanics of how we come to notice something in the shot, be it primary or secondary in value. In On the History of Film Style, I suggested that many aspects of technique work to call attention to any element in the field. The filmmaker can put a something in motion, turn it to face us, light it more brightly, make it a vivid color, center it in the frame, have it advance to the foreground, have other characters look at it, and so on. These tactics can work together in a complex choreography. In Figures Traced in Light, I argued that they depend on the fact that we scan the frame actively; the techniques guide our visual exploration. (6)

You can see this guidance at work in most of the examples I’ve mentioned. In River of No Return, we are coaxed into noticing Kay’s bundle because we’re cued by movement (the bundle falls and drifts off), performance (she shouts, “My Things!” and stretches out her arm), music (we hear a chord as the bundle splashes), and framing (Preminger’s camera pans slightly as the trunk drifts away). The critic can refine our sense of the effects that a film arouses, but it’s one task of a poetics of cinema, as I conceive it, to examine the principles and processes that filmmakers activate in achieving those effects.

Finally, we might ask: To what extent do we find gradation of emphasis in current filmmaking? Today’s American cinema relies heavily on editing, using a style I’ve called intensified continuity. Each shot tends to mean just one thing, and once we get it we’re rushed on to the next. The unforced openness of the wide frame that Barr celebrated has been largely banned, in favor of tight singles—even in the 2.40 anamorphic format. It seems that most filmmakers are no longer concerned with gradation of emphasis within their shots.

To find this strategy surviving at its richest, I think we have to look overseas. If you want names: Angelopoulos, Tarr, Kore-eda, Jia, Hou. (7)

(1) It was published in Film Quarterly, vol. 16, no. 4 (Summer, 1963), 4-24. Unfortunately, it’s not available free online, nor is a complete version available in anthologies, so far as I know. If you have access to online journal databases, you can find it. Otherwise, off to the library w’ye!

(2) In the Poetics of Cinema piece (pp. 303-307), I argue that some early uses of Scope tried to approximate such tightly organized composition, despite technological barriers to focusing several planes of action.

(3) See André Bazin, “William Wyler, or the Jansenist of Directing,” in Bazin at Work: Major Essays and Reviews from the Forties and Fifties, ed. Bert Cardullo, trans. Cardullo and Alain Piette (New York: Routledge, 1997), 14-16.

(4) Actually the phone booth is primed for our notice by earlier shots in Butch’s tavern. See On the History of Film Style, 225-228.

(5) For more on Eisenstein’s idea of polyphonic montage, see my Cinema of Eisenstein (New York: Routledge, 2005) and Kristin’s Eisenstein’s Ivan the Terrible: A Neoformalist Analysis (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1981).

(6) For some empirical evidence of this guided scanning, see the work of Tim Smith at his website and in this entry on this site.

(7) I discuss some of these alternatives in On the History of Film Style and the last chapter of Figures Traced in Light.

Eternity and a Day.

PS 15 Nov. Two more items. First, if the ideas floated here intrigue you, you might want to take a look at an earlier entry on this site, called “Sleeves.”

Second, I had planned to include one more example, but forgot it. In Lumet’s Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead, Andy Hanson’s life is unraveling. We follow him back to his apartment, and as he enters on the extreme left, his wife Gina is visible sitting on the extreme right, her back to us.

Gina forms a secondary center of attention, but the key to the upcoming action is revealed in a third point of interest: the black suitcase pressed against the right frame edge. The shot tells us, more obliquely than one showing her leaving the bedroom with the case, that she is planning to leave him. Lumet’s image, reminiscent of the framing of the trunk in River of No Return, shows that gradation of emphasis isn’t completely dead in American cinema. The orange scrap of yarn, knotted to the handle for baggage identification, is a nice touch of realism as well as a welcome color accent that further draws the suitcase to our notice.

Categorical coherence: A closer look at character subjectivity

Subjective

[NOTE: There are some spoilers here, though I’ve tried to avoid giving away the ends of the films I mention. Teachers who show clips in class would probably want to do the same. Some of the films mentioned here would be good choices to show in their entirety to classes when they study Chapter 3 of Film Art.]

Kristin here—

We have had occasion to mention the Filmies list-serve of the Department of Communication Arts’ Film Studies area here at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Current and past students and faculty, sometimes known as the “Badger squad,” share news, links, and requests for information. Once in a while a topic is raised for discussion. These exchanges are usually fascinating, and when we have felt that they might be of interest to a general audience, we have used them as the basis for blog entries. (See here and here.)

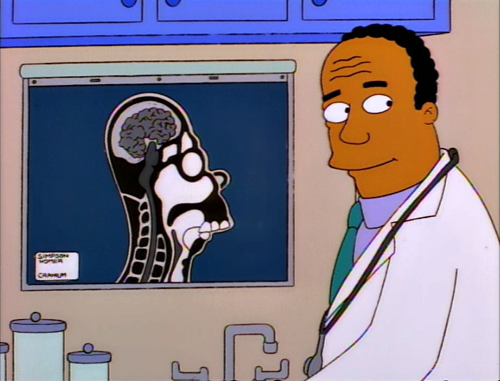

Another occasion arose recently, one which relates to the teaching of Film Art: An Introduction. Matthew Bernstein, of Emory University, queried the group about suggestions for teaching a section of the third chapters, “Narrative as a Formal System.” He found that the section, “Depth of Story Information,” gives some students trouble. They can’t grasp the distinction we make between perceptual and mental subjectivity.

Our definitions of the terms go like this. Perceptual subjectivity is when we get “access to what characters see and hear.” Examples are point-of-view shots and soft noises suggesting that the source is distant from the character’s ear. In contrast, “We might hear an internal voice reporting the character’s thoughts, or we might see the character’s inner images, representing memory, fantasy, dreams, or hallucinations. This can be termed mental subjectivity.”

We then go on to give a few examples. The Big Sleep has little perceptual subjectivity, while The Birth of a Nation contains numerous POV shots. We see the heroine’s memories in Hiroshima mon amour and the hero’s fantasies in 8 ½. Filmmakers can use such devices in complex ways, as when in Sansho the Bailiff, the mother’s memory ends not by returning to her in the present, but to her son, apparently thinking of the same things at the same time.

Yeah, but what about …?

Filmmakers don’t always use these categories in straightforward ways. They may oscillate between perceptual and mental representations and events. Films may present narrative events that make the distinction between characters’ perceptions and their mental events ambiguous. That’s why in introducing the concepts, we stress that “Just as there is a spectrum between restricted and unrestricted narration, there is a continuum between objectivity and subjectivity.

Easy to say, but not necessarily so easy to grasp for a student who’s trying to understand these categories. They need to start with simple examples to familiarize themselves with the basic distinction before going on to what the likes of Resnais, Fellini, and Mizoguchi can throw at them. But some students immediately proffering exceptions. As Charlie Keil, of the University of Toronto, put it in his post on the subject, “I hardly need add that students, even the least analytically astute, border on the brilliant when it comes to suggesting examples that provide challenges to categorical coherence.”

Looking over the one and a half pages of the textbook that we devoted to depth of narration, you might find it fairly straightforward. Once you start looking for ways to teach the concepts without bogging down in too many nuances and subcategories, though, the passage does seem challenging. What follows is a suggestion about how someone might go about explaining and utilizing examples. It also points up some ways we might revise this passage of the book for its next edition.

What it’s not

One obstacle that Matthew has found is that students are used to thinking of “subjective” as meaning something like “biased,” as in “here’s my subjective opinion on that.” It might be useful to point out that this is only one meaning of the word. The dictionary definition that comes closest to the way we use it in Film Art is this: “relating to properties or specific conditions of the mind as distinguished from general or universal experience.” For film, we specify that “subjective” means either sharing the characters’ eyes and ears (properties) or getting right inside his or her mind (conditions).

Another misconception comes when students assume that the facial expressions, vocal tones, and gestures used by actors are subjective because they convey the characters’ feelings. Again, best to scotch that notion up front. Those techniques are projected outward from the character, and we observe them. Cinematic subjectivity goes inward.

One step at a time

Another distinction to stress early on is the basic one we make between film technique and function. There are a myriad of film techniques that could be used in either objective or subjective ways. To take a simple example, a low camera angle might indicate the POV of a character lying down and looking up at something; that’s perceptual subjectivity. A low angle of a skyscraper in an establishing shot might simply be the objective narration’s way of showing where a new scene will occur.

In contrast, indicating perceptual and mental subjectivity are two specific kinds of functions. Filmmakers can call upon whatever cinematic techniques they choose, and historically the more imaginative ones have shown immense creativity in trying to convey what characters see and think.

Some films depend heavily upon subjectivity, but objective narration is more common. There are many films that give us little access to characters’ perceptual and mental activities. Apart from The Big Sleep, there are films like Anatomy of a Murder, or virtually anything by Preminger. Most films use subjectivity sparingly. So let’s assume the students can tell that objective narration is the default.

With that out of the way, we can go back to basics. Both perceptual and mental subjectivity depend on being “with” the character in a strong way, as opposed to observing him or her as we would see another person in real life.

Perceptual subjectivity is fairly simple. The camera is in the character’s place, showing what he or she sees. The microphone acts as the character’s ears. Other characters present in the scene could step into the same vantage point and observe the same things.

So the test could run like this: As a viewer, when we see something in a film, is it really present within the scene? Could someone else in the same position see and hear the same things? Or is it a purely mental event, something no one else could see and hear, even if they stood beside the character or stepped into the place where that character had been standing?

If I were teaching the concept of narrational subjectivity as Film Art defines it, I would stress the notion of a continuum. After starting with very clear examples of both perceptual and mental subjectivity, I would progress to more ambiguous, mixed, or tricky instances.

Contributing to this discussion on the Filmies list, Chris Sieving, of the University of Georgia, says he shows a  clip from Lady in the Lake, the film noir where the camera always shows the POV of the detective protagonist. As Chris says, “It seems to effectively get across what perceptual subjectivity means (and how awkward it is in large doses), as well as what is meant by a (highly) restricted range of narration (as is the case with most whodunits).” As Chris also says, Lady in the Lake is a sort of limit case, a film that depends as much on perceptual subjectivity as it’s possible to do. (That’s “our” hand taking the paper in the shot at the right.) One could show several minutes from any section of the film and make the point thoroughly.

clip from Lady in the Lake, the film noir where the camera always shows the POV of the detective protagonist. As Chris says, “It seems to effectively get across what perceptual subjectivity means (and how awkward it is in large doses), as well as what is meant by a (highly) restricted range of narration (as is the case with most whodunits).” As Chris also says, Lady in the Lake is a sort of limit case, a film that depends as much on perceptual subjectivity as it’s possible to do. (That’s “our” hand taking the paper in the shot at the right.) One could show several minutes from any section of the film and make the point thoroughly.

There are other films that contain a lot of POV shots but intersperse them with objective ones. Rear Window is an obvious case. When Jefferies is alone, we see the courtyard events from his POV, a fact which is stressed by his use of binoculars and his long camera lenses to spy on his neighbors. This is clearly perceptual rather than mental. We never doubt that what we see through the hero’s eyes is real; we don’t believe that he’s making things up to entertain himself or because his mind is unbalanced. For one thing, there are two other characters who visit at intervals and see the same things that he does. We and they might question whether Jefferies’ interpretation of what he sees is correct, but we assume that the story’s real events have been conveyed to us through his eyes and ears. Only if we saw something like his fantasy of how he imagines his neighbor might have killed his wife would we move into the mental realm.

These two films foreground their use of POV. Usually, though POV shots are slipped into the flow of the action smoothly. Scenes of characters looking at small objects or reading letters often cut to a POV shot to help us get a look at an important plot element. At intervals during Back to the Future, Marty looks at a picture of himself and his siblings, gradually fading away to indicate that the three of them might never be born if he doesn’t succeed in bringing their parents together. It’s a simple way of reminding us what’s at stake and that Marty’s time to solve the problem is running out.

The Silence of the Lambs uses many POV shots and provides an excellent case of narration switching frequently and seamlessly between objective and subjective. Most of the POV views are seen through Clarice’s eyes, but sometimes through those of other characters. The first view of Lecter is a handheld tracking shot clearly established as what she sees as she walks along the corridor in front of the row of cells.

The scenes of Clarice conversing with Lecter develop from conventional over-the-shoulder shot/ reverse shot to POV shot/ reverse shot as both characters stare directly into the lens. (In Film Art, we use this device as an example of how style can shape the narrative progression of a scene [p. 307, 8th edition]). Other characters have POV shots as well, most noticeably, when Buffalo Bill twice dons night-vision goggles and we briefly see the world as he does.