Archive for the 'Readers’ Favorite Entries' Category

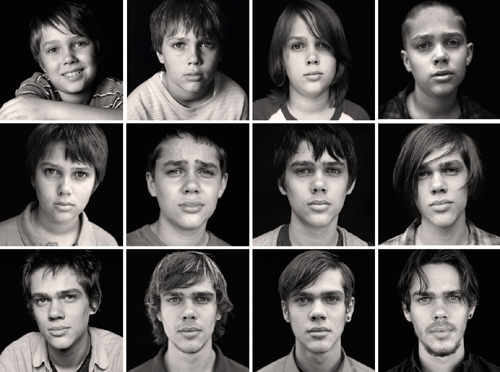

Harry Potter and the Twelve-Year Boyhood

Kristin here–

Note: As far as I’m concerned, Boyhood and the “Harry Potter” films have been out long enough that there is no need for spoiler alerts. It would certainly help in understanding this entry if the reader had some knowledge of the Potterverse.

Apparently audiences who saw Boyhood in its premiere screening at Sundance in January, 2014, went in not knowing that the film had been shot at intervals across over twelve years. Once the reviews appeared, it became known that Richard Linklater had done so, recording the actors, most notably Mason, the boy at the center of the film, actually growing older over the course of nearly three hours. The result was an outpouring of enthusiasm from critics and art-film afficionados alike. Less so, perhaps, from more mainstream viewers who went to see Boyhood once the Oscar buzz heated up. (On Rotten Tomatoes, it is rated 98% favorable by critics and 83% by fans.) From its July release up to the recent Oscars ceremony, it was considered one of the front-runners.

The film’s Oscar campaign took a rather puzzling turn toward the end. The film, which was considered unique in its intimate portrayal of one boy growing up in an unstable family situation, was suddenly “Everyone’s Story,” as if it was so universal that we all could see ourselves in it. The double-page spread from the February 20 Hollywood Reporter (which shows photos from each year of shooting) is too large to reproduce here, but here’s the upper section of the right-hand page:

Virtually nothing in Boyhood‘s story reminded me of anything in my life from six to 18, though, yes, I did graduate from high school and go off to college. Maybe men who as children faced their parents’ divorces, physical abuse, frequent moves to new homes, and so on, would relate to the film and enjoy it more than I did. Or maybe less. I don’t think that seeing this as a universal portrayal of the human condition is very realistic, though that was an idea touted by many critics as well.

I was entertained until the last hour or so, when I realized that Mason was going to remaining fairly passive and sullen to the end. His sister Sam and mother Olivia seemed to be more interesting characters, since they had goals, held strong opinions (right or wrong), made mistakes, accomplished things, and so on.

As an actor, Ellar Coltrane spends much of his time listening to what other actors say to him. His reactions are limited in range and usually involve a fairly neutral expression. In fact, I began to think that his performance is the perfect illustration of Kuleshov’s most famous, though lost, experiment: the one where supposedly the same footage of actor Ivan Mosjoukine looking offscreen was cut together with shots of things like bread, a dead woman, a child playing–things that would logically invoke widely varying emotions. Audiences supposedly praised Mozhoukin’s performance, saying he expressed hunger, sorrow, and happiness admirably. Accounts of what was shown in the shots Mosjoukine was “looking at” vary, and it’s possible the experiment was planned but never made. Whatever was the case, however, the principle seems plausible. What we find in a shot, including a shot of a face, depends on what shots precede and follow it.

I think something of the sort happened in Boyhood. Some expert professional actors, plus Lorelei Linklater as Sam, enacted scenes with Coltrane. Spectators may have imagined how a child would react to the events of the scene and read those appropriate emotions in his frequently impassive face. Otherwise it seems odd that people watching a fairly good art film offering a close, realistic study of a family over a period of twelve years, would consider Boyhood such a moving and historically momentous film.

Putting aside the “Everyone’s Story” appeal, Linklater’s film offers the unique case of a feature film shot across the actual twelve years covered by its story, allowing the actors, most dramatically the young ones, to age before our eyes. That’s impressive in itself, with the producer/director/writer Linklater managing to sustain the momentum of the financing and the actors’ cooperation across the full twelve years. I don’t wish to take anything away from that accomplishment, just to put it in perspective a little.

Wait, did I miss something?

As David has pointed out, films that are innovative, even experimental in some ways often compensate by drawing more heavily upon conventions from other areas. Although the jumps from year to year are somewhat disorienting, Linklater helps us out. He draws upon the old device of having the haircuts of the characters differ each time, even emphasizing this way of marking the passage of time by showing Mason getting an unwanted buzz-cut onscreen. He also characterizes Mason in fairly standard shorthand ways. At the opening he seemingly contemplates death by staring at a dead bird that he is burying. His characterization as slightly rebellious is pretty conventional: looking at semi-clad models in a catalog, allowing himself to be goaded into spray-painting graffiti, flirting with a waitress when he should be clearing tables while working at a local restaurant. Apart from the innovative device of the actor growing across a single film, he’s not a particularly original character.

I think, however, that Linklater does something much more interesting with Boyhood, and it has to do with the narrative structure rather than the aging of the actors. The film tells a deliberately sketchy story. Each one-year segment is obviously part of the characters’ lives, but there is little attempt to bridge the gap between them to create a conventional narrative flow. There are no dialogue hooks to create smooth transitions, no overt continuing goals, just Mason’s implicit desire to make sense of life and Olivia’s to find a happy path forward for her family.

Most obviously, events that would ordinarily be explained or motivated are simply ignored. The cuts from one segment to another are sometimes jarring, sometimes subtle enough that we don’t immediately realize that we’re jumped forward another year. As reviewer Kurt Brokaw points out, there are “no turning calendar pages, no inter-titles signaling the passage of time.”

What happens to Olivia’s third husband? (I’m assuming here that Mason Sr. was her first husband.) We see him before the marriage at a party, and he seems a decent enough sort. In a later segment he is married to Olivia. We see little of him, apart from one evening when his sits on the porch drinking beer and berating Mason for coming home late. Will he turn into another drunken abuser, like the second husband? Instead, he just disappears. Possibly in real life the actor playing him dropped out, in which case it would have been easy enough to mention his death or departure–at least something that would motivate his being gone. We don’t, however, get such an explanation.

Similarly, we are concerned when Olivia flees the home of the second, truly abusive husband, taking Sam and Mason but leaving their two step-siblings behind. Sam is upset and begs to take them along, but Olivia is concerned only to escape with her own children. Do the two kids left behind bear the brunt of their father’s wrath? Do they continue to be abused by him or do they somehow break free? These are important questions, especially after the extended and tension-filled scene in which the drunken man threatens Olivia and all four children. In a conventional narrative they would most likely be answered in some fashion.

Another plot point that I wondered about was the sudden introduction of religion into the narrative when Mason Sr., who has shown no signs of religious inclinations, remarries into a profoundly Christian family. Does Mason Sr. become a believer himself, or does he just avoid strife by attending church with her and her parents?

These and other questions occurred to me and were left unanswered. This is clearly not sloppy storytelling but a systematic strategy. Linklater forces us at each leap forward to struggle a bit to figure out where in these characters’ lives we are now–where they’re living, who is still part of their story and who has departed.

Indeed, I’ve never seen a film that compresses time in such a way as vividly to suggest how many people come and go in our lives, some to reappear, some not. I recently was contacted by a first cousin once removed whom I lost track of when my family moved from the Midwest in 1963. Retired, he was sitting in on a film class that assigned Film Art and decided to find out if one of the authors might be his cousin. Turned out he was living in Milwaukee and I in Madison for decades without knowing it. These things happen, and they do seem as abrupt and surprising as in Linklater’s film. That I can identify with.

I don’t think I’ve ever encountered a narrative film made within or at least on the fringes of the American production system with such frequent gaps and where so many links in the chain of cause and effects are missing. That, in my opinion, is the true innovation of Boyhood, but it’s not something the publicists can sell to the public and the Academy voters.

Right before your eyes

When I heard about the most famous aspect of Boyhood, I immediately thought, “I’ve seen that happen in the ‘Harry Potter’ films.” I was far from the first to think that. An early–perhaps the first–link between the Boy and the Boy Who Lived came as part of the publicity campaign for the film. From July 4 to 10, 2014, the IFC Center in New York ran all eight Potter films in a row as part of a series “honoring the release of Richard Linklater’s Boyhood.” IFC, of course, financed the film and released it in the US on July 11, 2014. Brilliant! as Harry would say.

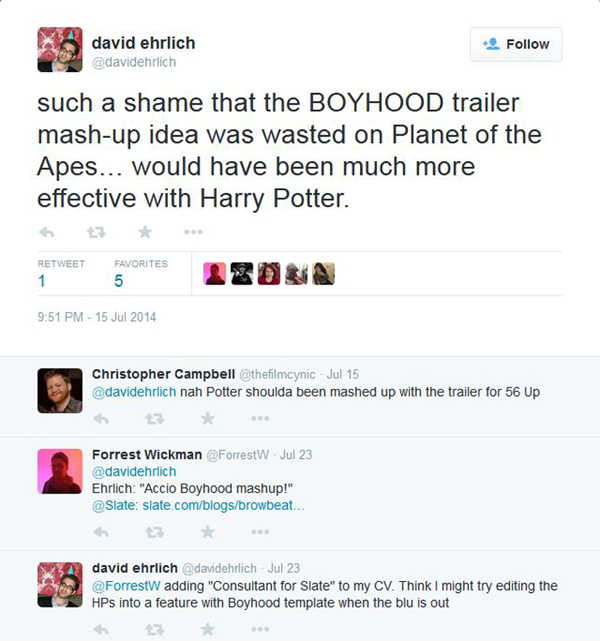

The professional and amateur fans on the internet then took over. On July 15 David Ehrlich (a freelance critic and among other things, Time Out NY‘s associate film editor) suggested a Boyhood/Potter mashup.

You cannot suggest such a mashup on the internet and not have someone take up the challenge. On July 23, Chris Wade posted Potterhood on Slate‘s culture blog, Browbeat, linked in the second comment above. (“Acciao” is a charm for summoning something.) Hence Ehrlich’s last comment in the thread above. A second mashup, also entitled Potterhood, appeared on IGN on February 6, 2015. Hard on its heels was the Honest Trailer – Boyhood, by Screen Junkies, posted on YouTube on February 10, which makes passing reference to Harry Potter. A sequence of five consecutive titles and shots:

The “Harry Potter” series (or, strictly speaking, serial) is only the most recent and well-known example. There have been other “growing-up” series and even a growing-up-and-growing-old series, which Christopher Campbell refers to in the first comment on Ehrlich’s tweet.

Justin Chang pointed out one precedent: “If the ‘Before’ movies are essentially Linklater’s riff on Rohmer, each one an endearingly loquacious two-hander played out against an idyllic Old World setting, then ‘Boyhood’ is unmistakably his tribute to Truffaut, who directed perhaps the greatest movie ever made about restless youth, ‘The 400 Blows.’ Similarly, the French master’s extended collaboration with actor Jean-Pierre Léaud as Antoine Doinel feels like an early template for what Linklater and Coltrane have pulled off here.”

There are wheels within wheels here. The Doinel series was mentioned to Daniel Radcliffe during an interview, and he responded, “The only one I’ve seen is The 400 Blows. Funny enough, I was asked to see that by Alfonso Cuarón, when he directed the third Harry Potter film. As a reference for Harry and his angst.”

Truffaut’s Doinel series went for a full twenty years, though not with yearly installments: The 400 Blows (1959), Antoine and Colette (1962, a short included in the anthology film Love at Twenty), Stolen Kisses (1968), Bed & Board (1970), and Love on the Run (1979). Unlike the “Harry Potter” series, these films were not planned ahead of time as a group. Truffaut would occasionally pop them in between his other films. They came out after some of his best films–Stolen Kisses after The Bride Wore Black, Bed & Board after The Wild Child, and Love on the Run after The Green Room. At the time we thought of them as Truffaut taking a break after a more difficult project. None of them lived up to the original, but we certainly did watch Jean-Pierre Léaud grow up.

Other critics have mentioned what has come to be called the “Up” series, which began as a television program, Seven Up! (1964) directed by Paul Almond. It consisted of interviews with 14 seven-year-olds. Michael Apted has continued the series with another film every seven years beginning with 7 Plus Seven (1970) and continuing, with the most recent being 56 Up (2012). One participant dropped out permanently, three skipped some episodes, but 56 Up interviewed 13 of the original 14, a remarkable achievement in showing the aging processes across 48 years and still going. Some people have found watching the series a profound experience. Roger Ebert wrote two four-star reviews of it, one in 1998 and another in January, 2013, a few months before his death. He called it “an inspired, even noble, use of the film medium.” But this series is documentary and perhaps not entirely a fair comparison. It is worth noting, though, that Jonathan Sehring, whose IFC had previously produced Waking Life, said that when Linklater pitched Boyhood to him, “The only thing I could draw as a parallel was Seven Up!”

I also wonder if back in the 1930s and 1940s some viewers found it moving as well as amusing to watch Mickey Rooney grow up in the Andy Hardy series, from A Family Affair (1937) to Love Laughs at Andy Hardy (1946), plus a revival, Andy Hardy Comes Home (1958), for a total of twenty films. This series was not intended as such at the beginning, but once the popularity of the character was apparent, MGM’s B unit cranked out two or three films a year and clearly planned to keep going indefinitely. These films had self-contained stories, but the subject matter was age-appropriate as Rooney, who was 17 at the time the first film was released, grew older.

Again, all this is not to denigrate Linklater’s film. It’s just a case of this blog seeking again to point out that almost nothing comes out of the blue with no historical precedents or conventions informing it. Certainly none of these series tried the sort of broken chain of causality that Linklater devised.

The Potter connection

Of all the series mentioned above, “Harry Potter” is most pertinent to Boyhood. Their production periods overlapped considerably, and their directors faced similar major challenges. This despite the disparity in their finances. “Harry Potter” had a huge budget supplied by Warner Bros., ranging from the lowest at $100 million for Chamber of Secrets to the highest at $250 million for Half-Blood Prince. (These are the budgets as publicly acknowledged, taken from Box-Office Mojo, which has no figures for the last two films.) Boyhood had a lean budget of $200 thousand for each of the twelve years and totaling about $4 million with postproduction and other expenses added in. Still, as we shall see, the challenges really had nothing to do with the budgets.

I didn’t see Boyhood until the day after the Oscar ceremony, when it was still playing in our local second-run house. I was surprised to discover that it includes references to “Harry Potter,” though to the books, not the films. These are among the several pop-culture and historical references (the Obama-Biden lawn-sign scene, various popular songs) that cue us as to which year of the twelve we have reached.

Early on Olivia reads a passage from Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets to Mason and Sam. We don’t see the cover of the book, but it’s a passage that clearly identifies which entry in the series it is. Chamber of Secrets came out in the USA on June 2, 1999. (Incredible as it now seems, the American releases of the first two books were roughly a year behind the British ones and didn’t reach a simultaneous release date until Goblet of Fire in 2000.) The kids are obviously fans, since later they wear costumes to attend the book-store release of Half-Blood Prince, which dates the scene precisely as July 16, 2005. I don’t think the use of Rowling’s series is a random choice. The first six books cover six years in the educations of Harry and his friends at Hogwarts, with the seventh and final one following their attempts to thwart the villainous Voldemort. All begin in the summer, often specifically including Harry’s July birthday. The first six end as the school year concludes, and at the climax of the seventh, Harry, Hermione, and Ron return to Hogwarts for Voldemort’s defeat.

Both Linklater’s feature and the “Harry Potter” film serial face the challenge of retaining the child actors across a lengthy period of shooting. Moreover, neither Linklater nor the “Harry Potter” filmmaking team started with a complete script. The script for Boyhood was written year by year, with input from the actors. The early “Harry Potter” films were made before Rowling had completed her books, and she seldom shared information about what would happen in the upcoming ones.

The boyhood of the Boy Who Lived

Much has been made of the fact that Linklater managed to keep Coltrane committed to the project to the end. Had he decided not to go on playing Mason, the project would presumably have ended. No one connected with the film has ever suggested that the film could have been finished. There was no option of forcing him to commit at the beginning to the full twelve years of shooting, since California law forbids film contracts lasting longer than seven calendar years. (The “De Havilland” law from the 1940s was based on a lawsuit by Olivia de Havilland that changed the Hollywood contract system forever, a story quite interesting in itself.) Given that constraint, however, the production signed Coltrane for the initial seven years and then gave him a second contract for five years. Legally there was one point at which he could have bailed, but presumably the filmmakers would not have forced him to stay with the project if he had badly wanted to stop.

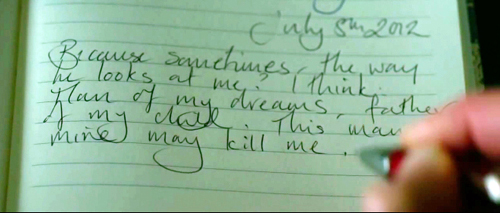

Lorelei Linklater, the director’s daughter, played the supporting but important character of Sam. While Coltrane never wanted to quit, she at one point did, and Harry Potter was involved. The director revealed this last month in an interview in The Telegraph:

Ironically, it wasn’t Coltrane who rebelled against this extraordinary commitment, but Linklater’s own daughter Lorelei. Three years into shooting Boyhood, when she was coming up to 12, she asked her father, ‘Can my character die?’ ‘She wanted out,’ Linklater says now. ‘But that was just one year.’

He learnt the true story behind Lorelei’s rebellion only last month when they were in England, and visited the Harry Potter sets at the Warner Bros studio tour. In one scene in Boyhood, Mason and Sam dress up as their favourite Potter characters and go along to a midnight sale of the latest Harry book. ‘I had Lorelei dress as Professor McGonagall, though I think she wanted to be Hermione,’ Linklater recalls. ‘Those stories were so real in her life. She thought she was going to get a letter from Hogwarts saying she could go there. She thought she might date Harry Potter. Not Daniel Radcliffe, Harry. So I think us filming that scene felt to her that we were belittling that, invading her space. She couldn’t admit it then. But she can now.’ He shrugs, ‘It was a daughter-dad thing,’ he says. ‘Not actress and director.’

Given Linklater’s daughter’s intense involvement in the Harry Potter universe, one wonders if the idea for Boyhood was, at least unwittingly, inspired by Rowling’s creation. By the time the deal for support and casting of Boyhood was settled in 2002, four of the books and the first film had come out. Not that it’s important to my points here, but it’s intriguing. If true, then certainly Linklater took his own project in a completely different direction.

Obviously Linklater persuaded Lorelei to continue, which is all to the good of the film. Mason has a lot of troubles, and having his sister die probably would seem too great a bid for sympathy by the filmmakers.

On the other hand, the “Harry Potter” producers faced the real possibility of having to replace some of the child actors, given that a highly expensive and popular series could hardly shut down because, say, Daniel Radcliffe or Emma Watson decided to leave or came to look too old for his or her role. Certainly there are so many students at Hogwarts that the minor parts could have been recast without difficulty. At minimum, though, it was important to keep the central and the important supporting roles constant: Harry, Hermione, Ron, Fred and George, Ginny, Neville, Luna, and Draco. Obviously keeping the actors in the adult roles constant was desirable as well, though the one replacement that proved necessary didn’t scuttle the series.

Warner Bros., though prescient about approaching Rowling for the rights early on, had little evidence that the first book would be as successful in the US as it had been in the UK. In 2011, Rowling wrote an informative article about her relationship with the series’ main screenwriter, Steve Kloves, who penned all the scripts except for that of Order of the Phoenix. She describes her first meeting with him, just before going into lunch with a big studio executive. (This would have to have been in the period from late summer of 1997 to early autumn, 1998.) She mentions being wary about being introduced to Kloves.

He was going to butcher my baby. He was an established screenwriter, which was just plain intimidating. He was also American, and we were meeting shortly after a review of the first Potter book in (I think) the New Yorker, which had stated that it was unlikely the British idiom would translate to an American audience. You have to remember that my first Warner Bros. meeting did not take place against a backdrop of massive American success for the novels. Although the books were already very popular in the U.K., it was still early days in the U.S., and I therefore had no real means of backing up my opinion that American fans of the book would rather not have Hagrid “translated” for the big screen, for instance.

Odd though it seems now, the “Harry Potter” actors were initially contracted only for the first film. By number three, Prisoner of Azkaban, there was already talk of a change of the young central actors. Radcliffe remarked in an interview, when asked if he thought at the start that he would do all seven movies, “I was never sure I was going to do any of the films, other than signing on for the first and second. After that, it was always going to be: We’ll take it one film at a time.” This suggests that the contracts were made film by film throughout, and that Linklater had a better chance of retaining his main actors than the “Harry Potter” producers did.

There was in fact considerable talk during the production of the “Harry Potter” series that one or more of the child actors would be departing. (The quotations with dates in brackets below are from the imdb news pages for Daniel Radcliffe , which is a handy chronology of information concerning the film series, often excerpted from sites behind paywalls.)

[5 Sep 2002] Harry Potter star Daniel Radcliffe has resigned himself to growing out of the child wizard movie role–literally. The 13-year-old actor has finished filming the second installment of the adaptation of J. R. Rowling’s massively successful seven strong children’s book series, but his voice has already broken and he’s just had a growth spurt. He says, ‘In a couple of years, I might have changed so much that I look wrong for the part–even though Harry grows with the books.”

[22 Oct 2002] Another company of young actors is expected to take over the principal roles in the Harry Potter film franchise beginning in 2004 for the fourth movie, Chris Columbus, the director of the first two Potter movies, predicted Tuesday. Noting that the current stars, Danial Radcliffe, Emma Watson, and Rupert Grint will all be teenagers next year, Columbus told Reuters. “If I were a betting man, I’d say they’ll probably stop after three.”

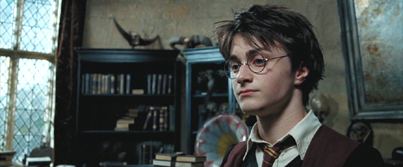

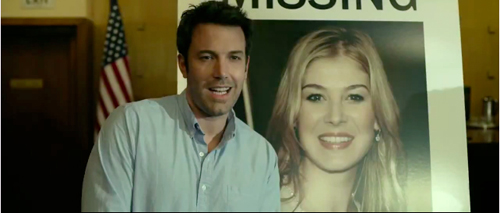

Indeed, the delays with the third film had allowed the cast to grow more than between the first and second, and the difference is quite obvious in Prisoner of Azkaban (above).

The producers perhaps realized by this point that, although the first two films had been released one year apart (Nov 2001 and Nov 2002), the pace could not be maintained. Indeed, the final film was released in July of 2011. This meant that although seven years of plot duration had passed for Harry and his friends, it took ten years for the films to come out. In most cases there was a one-and-a-half to two-year gap between releases, which came in November or June/July.

The following year there was renewed speculation, this time that the main children would be replaced for the fifth film:

[18 June 2003] Although analysts have suggested that the three young stars of the Harry Potter movies are quickly outgrowing their characters, the Reuter News Agency on Tuesday, citing an industry source familiar with the matter, reported that they will likely return for the fourth Potter film, Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire, due to be released in November 2005. By that time, Daniel Radcliffe, who portrays Harry Potter, will be 16 years old. Reuters quoted Seth Siegel, founder of The Beanstalk licensing and marketing consultancy group, as warning that if the stars are not replaced by younger actors, “licensing will fade away.” Wendi Green, an agent for child actors with Abrams Artists Agency, told the wire service, “If [they] are too old, kids can’t relate to it.”

Tom Felton, who played the young villain Draco Malfoy throughout the series, said in a 2011 interview that “We all feared that after the fourth film that they were going to get rid of us and start again with new kids. So yes, we’re very proud to have made it through.”

The rumors about the departure of Radcliffe or others continued fairly late into the series:

[4 March 2007] British actor Daniel Radcliffe’s representative has confirmed that he has signed on to start in the final two films in the Harry Potter series. […] The hit franchise, which continues with the fifth installment, Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix, later this year, has grossed $3.5 billion globally at the box office. Rowling recently announced that the seventh and final book in the series, Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, will be published on July 21, but no film start date has been officially set.

Before the release of the final film, Kloves revealed that the departure of the main actors would have caused further upheaval in the series: “Emma was always the one who, we thought might leave, and I always said that if one of the kids left I would leave. And I would have because I only wanted to write for those three. I’m actually kind of amazed they all ended up doing it. It was the most important thing that happened to the movies.” Kloves’ continued participation obviously was crucial not just for keeping the series consistent in tone, but because he also had established a rapport with Rowling that gave her confidence that her books were being respected.

The filmmakers successfully retained all the significant child cast members, as well as many of the unnamed background figures, who are hard for even devotees of the books to identify. Only one moderately significant child actor was lost: Jamie Waylett, who played Vincent Crabbe, one of Draco’s two thuggish sidekicks/accomplices, dropped out before the final film. He had no choice, since the departure resulted from the first of several brushes Waylett would have with the law. This happened in April 2009, and he was in jail when the parts of Deathly Hallows began shooting simultaneously. Luckily Crabbe, although quite recognizable and prominent in a few scenes, is a fairly minor character (the chubby fellow seen below with Draco in the final scene of Philosopher’s Stone). Another Slytherin student, Blaise Zambini, introduced briefly in the the previous film, Half-Blood Prince, took over his function as the second of Draco’s two muscle-men. In all the commotion of the last film—and the fact that relatively little of the action takes place at Hogwarts–the substitution probably went unnoticed by most viewers.

This almost total stability among the child actors was fortunate, given how well the parts had been cast. The adult roles were equally well cast, with the exception of Richard Harris, who was already visibly feeble as Dumbledore in the first two films and could not realistically have been expected to make it through the series. His death led to Michael Gambon replacing him from the third film on, which seems to have had no adverse effect on the popularity of the films.

Thus the large cast of children for the “Harry Potter” series, with their short-term contracts, created a balancing act at least as great as that of keeping the two main child actors of Boyhood committed to the project until the end.

The end is not in sight

The first film, Philosopher’s Stone (aka Sorcerer’s Stone in the US), premiered in November, 2001. By that point, four of the seven books had been published, the most recent having been Goblet of Fire in July, 2000. The three remaining books, all very long, were still to come.

They were all, however, plotted. Anyone who has read the novels knows that they are maniacally intricate in their storytelling, with dozens of characters and hundreds of premises about Rowling’s invented world. People or things may be introduced early and return much later, only then being revealed as important. Gellert Grindelwald, for example, is mentioned on the back of the Dumbledore collectible card that comes enclosed with the chocolate frog that Harry buys in the first book. He is said to have been a Dark Wizard defeated by Dumbledore in 1945. That seems to be a mere bit of trivia until in the final book Grindelwald is revealed to have been a sort of predecessor Dark Lord to Voldemort, to have been a friend of Dumbledore’s in the headmaster’s unexpectedly shady youth, and a key figure in the fate of the Elder Wand, one of the three Hallows of the title.

Even knowing nothing about Rowling’s writing process, it’s obvious that she had to have worked the whole thing out in advance and in considerable detail. This was indeed the case: “Rowling conceived the idea for the series on a 1990 train ride. From the very beginning, she designed the books as a seven-book series. Rowling spent 5 years planning the plots and refining the characters before she ever started writing. She even wrote complete biographies of her characters prior to writing. Rowling is a careful and meticulous author, one who wrote no fewer than 15 drafts of the first chapter of Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone.”

So when Rowling met Kloves at the meeting described above, she already knew much about how the series would proceed and end. Once the scripting process began, Rowling made herself available for consultation by Kloves via email and occasionally attended script meetings. What she did not do was tell Kloves what would happen in the upcoming books:

Steve would ask me questions, sometimes about the background of the characters, sometimes on whether something he’d had one of them say or do was consistent with what had happened to them or what would happen. He very rarely took a wrong turn; in fact, I’m struggling to remember any occasion when he did. He had a phenomenal instinct about what each character was about; he always plays that down, but he made some very accurate guesses about what was coming.

Actually, I’ve just remembered the only time he did get something wrong, and it was a funny one. We were at a script read-through for Half-Blood Prince at Leavesden, so for once we were side-by-side in the same room. I hadn’t read the very latest draft, so I was hearing it for the first time. When Dumbledore started reminiscing about a beautiful girl he’d known in his youth, I scribbled “Dumbledore’s gay” on my script and shoved it sideways to Steve. And we both sat there smirking for a bit.

I don’t think he ever pushed to know what was coming next. Odd, really, when I look back; except that I’ve got a feeling that as a fellow writer, he understood that I needed some space. There came a point where my bins were being searched by journalists; keeping tight-lipped was a way of giving myself creative freedom. I didn’t want to be tied down by expectations I’d raised; I wanted to be at liberty to change my mind. But I did tell Steve a few things. I used to share what I was doing as I was doing it. I remember emailing him while writing Goblet of Fire and telling him that I had backstory on Hagrid that I wanted to put in, but I was wondering whether it wasn’t too much, given how big the novel was likely to be. He emailed back saying, “You can’t tell me too much about Hagrid. Put it in.” So I did.

(On the later public revelation of Dumbledore’s being gay, see here.)

In making Boyhood, Linklater knew how many years he would work, but he was writing the script himself when he went along. He adjusted the story to suit the changes in his main actor. In real life, Coltrane became interested in photography, so Linklater made it part of his character. There was no set plot, just a timeline. And despite how much Coltrane’s looks changed as he grew, he never could be inappropriate to the role, for he defined and determined that role.

The same was not true for the Potter cast. No one could predict what they would look like in ten years and whether it would fit what happened to their characters in an unknown plot that had already been extensively planned out.

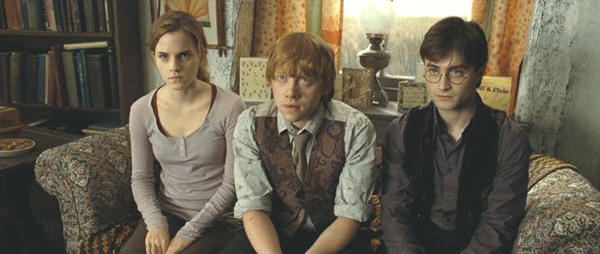

Yet on the whole, the filmmakers were consistently lucky. The changes worked. While all three of the main characters started out very cute (see top, Philosopher’s Stone), as they grew, Grint, as Ron, lost that cuteness. His rather plain looks fit well with his increasing jealousy of Harry, which is especially important in Goblet of Fire (below left) and Deathly Hallows Part I. Radcliffe kept much the same basic look as he matured, with cute becoming cutely handsome (below right in Prisoner of Azkaban). Watson blossomed into a beautiful young woman, as suddenly revealed to the other characters in the ball scene of Goblet of Fire (above).

The same turned out to be true of the supporting characters. Felton as Draco began in The Philosopher’s Stone as a spoiled brat (at left below wearing one of the black pointed wizard hats that were true to the book but wisely discarded for the rest of the film series). He effectively became a tormented, would-be killer who slowly develops a conscience (below right, in Half-Blood Prince).

Bonnie Wright plays Ginny Weasley, who begins as a shy girl so impressed by Harry that she can’t utter a word in his presence (their first meeting in Chamber of Secrets, below left). Four years of real time later, in Goblet of Fire, she barely looks any older (below right), and the filmmakers might have worried that she would not mature enough by the end of the series to appear plausibly old enough for Harry to fall in love with and marry:

On the other hand, this works quite well with the book’s action, where Ginny, being a year behind the others–a third-year rather than a fourth-year–could not go to the ball at all unless she had a fourth-year as a date, and she accepts Neville after Hermione turns him down. In the book, Ginny somewhat regrets her choice, in that clumsy Neville keeps stepping on her feet as they dance. In the film, the fact that Ginny looks so young here makes it difficult to imagine that she and Neville should be taken seriously as a potential couple.

Again luck was with the filmmakers, and Wright was a young woman in time for the romance depicted in the book to develop (below in Deathly Hallows Part I).

Undoubtedly, though, the filmmakers’ most impressive stroke of unforeseeable casting luck was with Matthew Lewis as Neville Longbottom. Neville first appears early in Philosopher’s Stone, where he is quickly established as the class dork. On the train to Hogwarts he has lost his pet toad, and once in school he turns out to be clumsy, forgetful, totally lacking in confidence, and bad in classes, all of which make him seem doomed to remain a conventional comic figure. The young Lewis, with his chubby cheeks, buck teeth, and timidly wary expression (below, in Philosopher’s Stone) embodied the role perfectly.

Rowling carefully motivates the gradual emergence of confidence in Neville. In the scene just above, from the climactic scene, Dumbledore is handing out extra points, upon which winning the Class Cup for the year depends. Predictably, Harry, Hermione, and Ron get 50 each for their heroic actions in foiling Voldemort in his attempt to return to bodily form. But Neville, who had failed to talk them out of their dangerous endeavor, gets ten points for the bravery displayed by his effort–the ten needed to put Griffindor into first place. He’s stunned by this (above), but in the second book (and film) it seems not to have bolstered his confidence much. In the third book, Prisoner of Azkaban, Neville manages under Lupin’s guidance to defeat the shape-shifting boggart–his first classroom success (in the film, below left, where Lewis is already almost unrecognizable compared to his earlier self). In the next book, Goblet of Fire, we begin to get hints at Neville’s tragic past: his parents, heroic figures in the earlier struggles against Voldemort, were tortured into insanity, and he has been raised by a demanding grandmother who has little patience with his shortcomings. (This past is sketched much more briefly in the film series.)

Later he discovers that he has an aptitude for herbology (something made explicit in the book but not in the film series, though there Neville does show up one year carrying a rare plant rather than his toad). In Goblet of Fire he takes Ginny to the ball (above). In Order of the Phoenix, once the dire Dolores Umbridge starts taking over Hogwarts with her Orwellian rules and her plans to replace Dumbledore, Harry agrees to teach the other students how to defend themselves against the Dark Arts. After a rocky start, Neville (who has become considerably taller than Harry) slowly and with grim determination manages to learn the important spells that “Dumbledore’s Army,” as they call themselves, will need in the struggles to come (below right).

Ultimately Neville becomes one of the heroes of the final battle against Voldemort. During the last two books/three films, Dumbledore and Harry, and after Dumbledore’s death, Harry, Ron, and Hermione, have been seeking and destroying horcruxes (six mysterious objects into which Voldemort has hidden parts of his soul in an attempt to achieve immortality). Five have been destroyed by the main trio, but it is Neville, standing before the shattered courtyard of Hogwarts, who defies Voldemort and destroys the sixth horcrux. This makes it possible for Harry to kill Voldemort.

Lewis turned into a handsome young man, thoroughly appropriate for the new determined and heroic Neville. (Lewis’ unexpected change has been much commented upon on the internet, of course. See here, here, and here. There is considerable gushing involved.) The most optimistic casting director could not have had a clue as to how the eleven-year-old Lewis would transform to fit the end of his character’s arc, especially given that that arc was completely unpredictable to all but Rowling.

(It’s a pleasure to know that in the book he becomes the professor of herbology at Hogwarts, though there’s no mention of this in the film.)

Here I think we see the film’s greatest advantage over the book, and perhaps it took Boyhood to make us fully realize it. Rowling, though not much of a stylist, creates a vast and complex plot, and in the books we get to experience all of it. She is adept at portraying a wide range of intriguing and entertaining characters, and the dialogue she gives them flows easily and suits them. Much of this had to be cut or compressed for the films, long though they are.

Any literary adaptation into film allows us to see settings, characters, and actions that the book cannot portray visually. In the case of the “Harry Potter” series, the design of the Quidditch stadium brought that sport to life and special effects made non-human characters like Dobby and Kreacher seem real. But ultimately the actors and their changes over time added something even more important that the characters as written could never have. Kloves recalls an early meeting: “I remember sitting in an office 10/11 years ago with Lorenzo de Bonaventurea [producer of, among others, the Transformers series], David Heyman [producer of the “Harry Potter” series] and Chris Columbus [director of the first two “Harry Potter” films] and we were having this 15 minute conversation about special effects. I said, ‘You guys, the special effects you’re gonna have is those kids. Cast those three kids right and it’ll never end but if you miss, forget it. It’ll never work.”

Unfortunately the growth of the characters over seven years is somewhat undercut by the “19 years later” epilogue of The Deathly Hallows. In the novel, it’s tolerable, since we simply imagine them as older. Still, I would have preferred to do without it, even if it meant not learning about Neville’s professorship and Harry’s son being named Albus Severus Potter, both satisfying final touches. But in the film, the actors, after we’ve watched them actually grow for the seven years of attending Hogwarts and for the ten years of the production, simply cannot suddenly leap into their later 30s. Some of the actors look vaguely plausible in their old-age makeup (Radcliffe somewhat, Watson not in the slightest), but it’s jarring to see them trying to play considerably older. The epilogue should definitely have been dropped from the film, though I realize that Rowling is inexplicably attached to it.

March 21, 2015: Thanks to Antti Alanen, who informs me that there was a Finnish six-film series, Suomisen perhe (“The Family Suominen”), made from 1941 to 1959. One of the family members, Olli, was played by Lasse Pöysti, who went from age 13 to 32 in the course of the series and became a major Finnish actor. Antti says that critics of the period compared Suomisen perhe to the Andy Hardy series.

December 30, 2016: A screen test involving Racliffe initially and then all three of the child actors, is available on YouTube. All three are visibly younger than in the first film, but one can see why they were cast.

BIRDMAN: Following Riggan’s orders

DB here:

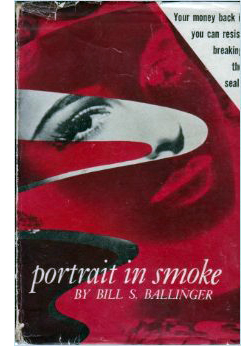

In a Broadway bar, the New York Times drama critic has just told Riggan Thomson that her review will destroy his play. Riggan snatches up her review of another production, reads it quickly, and declares it packed with meaningless “labels.”

There’s nothing in here about technique. There’s nothing in here about structure. Nothing here about intention.

Happy to oblige, Mr. Thomson. Spoilers ahead.

Structure: Icarus rises

Birdman’s plot covers six days at a critical period in Riggan’s life. He’s an over-the-hill movie star identified with playing the crime-fighting superhero Birdman. Now he’s directing and starring in a play he has based on Raymond Carver’s short story “What We Talk about When We Talk about Love.” The film’s plot starts on the day before the first preview, when during a rehearsal Riggan hires the arrogant but talented actor Mike Shiner. Three nights of more or less bungled preview performances follow. The climax comes on opening night. In the play’s suicide scene, the despondent Riggan shoots off his nose. The Times critic publishes a rave review and Riggan, recovering in the hospital, finds that he has a Broadway triumph. His response to that, however, is rather ambivalent.

The film feels a little odd—“quirky” is the official term—but its blend of comedy and drama is constructed along familiar lines. The major characters have goals. Riggan wants to prove he can do something valuable, while paying homage to Raymond Carver, who encouraged him when he was starting out on the stage. Riggan is also disturbed by his failures as a father and husband; mounting this play about love would seem to be an act of penance. The protagonist’s search for authentic success and psychological stability might remind you of 8 ½ and All That Jazz, which also endow their protagonists with flamboyant fantasy lives.

The other characters state their goals in that confessional mode typical of melodrama. (Extra motivation: in the world of the theatre people are always ready to overshare.) Mike wants to express himself artistically and to make Riggan’s play conform to his standards of honest realism. Lesley, the female lead and Mike’s girlfriend, wants to make her Broadway debut a success. Jake, Riggan’s producer, is trying to pull the whole thing off. Riggan’s scowling daughter Sam is looking for a settled life after a stint in rehab, while Riggan’s girlfriend and second lead Laura wants to have a child. As the plot develops, in true Hollywood fashion, the major characters achieve their goals.

Structurally, the plot falls into the four parts that Kristin has found to be common in Hollywood features.

The Setup lays out the premises for the action—identifying characters, explaining their motives, and articulating their goals. It’s packed with exposition, ranging from the old standby in which a character announces what the other character knows (“You’re my attorney. You’re my producer. You’re my best friend”) to the meeting with the press in which Riggan’s past as a movie star and his hope for this production are redundantly laid out. The thirty-minute setup ends with the first botched preview and Riggan’s moment with his ex-wife Sylvia. He explains that the production means everything to his self-respect.

The Complicating Action, a counter-setup which redirects character goals, centers mostly on the effects that Mike has on the show. Since he drunkenly improvised during the first preview, Riggan realizes they have to come to some understanding. Mike’s onstage antics in the second preview threaten Lesley’s hopes for a breakout career. They break up, and Mike and Sam begin flirting. Mike also steals the spotlight in a newspaper feature about the production, even swiping Riggan’s story about Carver’s encouragement. More deeply, Mike’s rants against Hollywood make Riggan feel even more fearful that his play will be a disaster and he’ll be a laughingstock. All of these anxieties come to focus in an extended inner dialogue between Riggan and Birdman, who insists that he will fail and will have nothing left. Riggan is ready to cancel the show, but Jake pushes him forward.

About an hour in, near the midpoint, we get the Development. This typically consists of a holding pattern. The plot doesn’t advance much. Riggan’s conflict with Mike deepens and his worries about the show mount. Lesley thanks him for giving her a chance, he reprimands himself again for being a bad dad to Sam, and Sam and Mike become a couple. A comic interlude, probably the film’s most widely-known scene, adds to Riggan’s debasement. He’s locked out of the theatre and, wearing just his underpants, races around the block through a Times Square crowd.

Reentering the theatre, he plays the crucial motel scene by lurching down the aisle and onto the stage, where he enacts the suicide. It’s also during the Development that Riggan meets Tabitha, the Times critic, and learns that, sight unseen, she plans to roast his play. The next morning his fantasies take over and, urged by Birdman, he enjoys a swooping and soaring flight around the theatre district.

The fourth part, the Climax, begins with the intermission during the premiere. The audience drifts onto the sidewalk, praising the first act. Backstage Riggan tries to calm his nerves. After confessing to Sylvia that he once tried suicide, he takes the pistol on stage and prepares for the motel scene. On stage, as if succumbing to Birdman’s rhetoric, Riggan confesses, “I don’t exist.” He blasts off his nose. After a brief montage, the epilogue shows us the result. Recovering in the hospital, Riggan has a successful play, a sympathetic ex-wife, and a daughter reconciled to loving him. Even Birdman, sitting on the toilet, is for once silent.

But the very last moments are equivocal and for once you won’t get the spoiler from me. Suffice it to say the tag is ambiguous in magical-realist fashion.

The plot helps us trace character change along classical lines. Key locales mark phases of the action. Sam and Mike meet on the rooftop twice, Riggan visits the bar twice, and Riggan’s ex Sylvia comes to his dressing room once in the Setup and once in the Climax. Whenever we return to the stage we see a version of either the apartment quarrel or the motel suicide. (We do glimpse, also twice, a hallucinatory scene of dancing reindeer, associated with Laura.) The main arenas are the stage and Riggan’s dressing room, which is the site of eight major scenes. The corridors snaking around the theatre serve as transitional spaces. As the film goes on, González Iñárritu tells us, the corridors get narrower and dingier. The fairly rigid time-structure of the plot finds a counterpart in a to-and-fro spatial pattern that measures Riggan’s jagged decline.

I’ve barely mentioned one of the crucial factors in the film’s narration. From the start Riggan hears the voice of Birdman admonishing him to return to superhero movies and give up this arty stuff. At certain points, it seems that Riggan gains some telekinetic powers, enabling him to smash flower pots, furniture, and light bulbs with the wave of a hand. These moments can be construed as subjective, in the sense that he “actually” destroyed them in a normal rage but felt that he was disposing of them through a superhero’s powers.

These powers are suggested at the start with an image of him levitating during meditation. They come to a kind of climax when he launches himself, a trench-coated Birdman, into the air, in a flight that serves as a counterweight to the humiliation of his naked canter through Times Square. Again, the film’s narration suggests that it’s all in his mind: after he lands and returns to the theatre, a cab driver pursues him demanding his fare.

The nagging voice of Birdman supports another kind of structure, a thematic one pitting East Coast and West Coast values. The material is traditional, being given sharp expression in The Band Wagon. The opposition goes back at least to Twentieth Century (1934, a Hollywood satire on Broadway pretensions) and Merton of the Movies (1922, a Broadway satire on Hollywood vulgarity). Of course the two artforms feed off one another. Twentieth Century started as a play, and Merton was made into a movie. The Producers began as a movie mocking Broadway, it became a hit Broadway musical, and the musical was made into another movie.

Birdman revisits these well-worn themes. Mike and Tabitha excoriate Riggan for his trashy films; only the theatre is real art. By contrast, Birdman’s croaking whispers remind Riggan that millions of ordinary folk like his blockbuster movies, while the theatre is for phonies. Mike’s narcissism and pretentiousness, the absurdity of his notion of realism, and the snobbishness of Tabitha all support Birdman’s point. As is common in such movies, the Eastern elite is shown as a pushover for superficial seriousness and ham acting. At the same time, Riggan sincerely wants to pay homage to the emotional core of Carver’s story; he may just not realize how bad the idea is.

The eternal Hollywood/Broadway opposition is sharpened in the light of new entertainment trends. Birdman tells Riggan that old superheroes—presumably those of the vintage of Michael Keaton in Batman (1989)—have it all over “posers” like Downey and the new generation. This motif refers, I think, to the modern trend toward troubled superheroes, set up in Burton’s Batman and carried to neurotic extremes in later comic-book sagas. But of course Riggan personifies the troubled superhero himself.

The sense of Riggan being old-school is reinforced by another familiar thematic duality, that of the young versus their elders. Riggan’s conflict with his daughter recycles the motif of a father so obsessed with work and seduced by false values that he ignores his daughter. (What is it with our filmmakers and this father/daughter thing? Is it just a way to pair older men with cute younger women in a safe way?) Sam berates him for being invisible in today’s world.

You hate bloggers, you mock Twitter, you don’t even have a Facebook page. You’re the one who doesn’t exist. . . . You’re not important. Get used to it.

The modern definition of entertainment includes the Internet, a realm that Riggan enters only by accident during his skivvy promenade. Sam’s denunciation reiterates Birdman’s insistence that Riggan doesn’t exist, except that she makes it worse: even if he returned to the Birdman role, no one would care.

The presentation of superheroics in Riggan’s fantasy mocks summer tentpoles, and would appear to express director Alejandro González Iñárritu’s distaste for action extravaganzas. But the movie is pretty hard on the theatre world too. It’s unfair for Mike and Tabitha to castigate Riggan now that playing a superhero has become artistically legitimate. The only performers Riggan can imagine replacing his wounded cast member are accomplished actors (Harrelson, Fassbender, Renner) who also star in franchise entertainments. The new entertainment economy shows that Riggan was a pioneer; now everybody wears a cape. But these stars routinely do serious films, even Broadway drama, along with tentpole movies. Why can’t Riggan cross over too?

The disruption that arrives when popular entertainment invades the sacred space of the theatre finds a hallucinatory expression during the climactic montage. Now street drummers and superheroes crowd the stage of the St. James. What price Tabitha’s Art of the Theatre with Spidey drawing big crowds?

At the end, Riggan earns his accolades as an actor, but what he’s been after, hinted at in the references to Icarus and the liberation of his flight over the city, is validation of his worth. Once he realizes he is indeed loved (by ex-wife, daughter, best friend), he’s happy to pay the price of his nose. He gains a new superhero cowl, a gauze-bandage mask, and a surgical version of Birdman’s beak. And now that flight is no longer fleeing, he can consider all his options.

Technique; or, Intensified continuity without cutting

This plot could easily have been presented in a manner typical of today’s moviemaking, both indie and mainstream. That is, there might have been hundreds or probably thousands of shots. But Birdman, we’re told by people who should know better, consists of a single shot.

Any viewer can see that’s not true. Depending on how you count the opening quotation from Raymond Carver (is it part of the credits, or a separate shot?), there are sixteen discernible shots in the movie. Apart from the titles, the opening gives us three quick images—a seaside landscape with jellyfish, two shots of a plunging comet—and the final portion of the film provides a montage of nature scenes, interiors, and stage performers.

Admittedly, these shots account for little of the running time. The bulk of Birdman consists of what appears as a continuous shot running a little over 101 minutes. In production, several shots were merged seamlessly into the one that we perceive. The hospital epilogue consists of another long take, that lasting about eight minutes, and it too may have been assembled from separate takes.

Filmmakers confront a lot of options for handling long takes. The boldest, probably, is the static framing that doesn’t use camera movement. This option is employed in early cinema (viz. the Lumiêre films), in the tableau tradition I’ve gabbled about fairly often, and by some very rigorous directors like Hou Hsiao-hsien, Andy Warhol, and Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet. But most films using long takes rely upon camera movement.

In Birdman, unsurprisingly, the camera movements are typical of Hollywood’s modern intensified continuity style. For example, we often get the push-in on a character close-up.

We get orthodox Steadicam movements trailing a character from behind or backing up as he or she strides toward us. This yields the familiar walk-and-talk.

And we get the standard treatment of people around a table, with the camera circling it to pick up each one’s reaction at a critical point.

To a great extent, then, Birdman’s long-take style stitches together schemas that are well-established in contemporary Hollywood. Another current device is the occasional depth shot yielded by wide angle lenses. This technique was well-established in Hollywood in the 1940s, and today’s filmmakers rely on the same sort of tools that classic cinematographers used: strong lighting and wide-angle lenses.

The wide-angle lenses used on Birdman, only 14mm and 18mm, don’t always create wire-sharp focus in depth, but they provide enough visibility to create depth effects. Sometimes the rear plane is made sharper through racking focus.

More pervasively, in many long-take films, the camera movements replicate the patterns we find in an edited scene. Editing gives the camera a kind of ubiquity: it can go anywhere. Tethered to unfolding time, the long take sacrifices the ability to change views instantly. Yet in such films the action is staged and framed so that nothing important escapes our notice. The action gets spelled out as precisely as it would if the scene were edited.

People have wondered a lot about the hidden edits that blend Birdman‘s long takes, but more important, I think, are the ways that the style adheres to standard editing patterns within its long takes. For example, the over-the-shoulder angles of shot/reverse-shot are mimicked by a camera arcing to favor first one character, then another.

We can get shot/ reverse-shot effects via mirrors.

A pan can also approximate a point-of-view shot, as when Tabitha sees Riggan at the other end of the bar.

Throughout, the ensemble staging motivates shifts that would normally be covered by cuts. Mike and Riggan are seen from behind the bar, but when customers spot Riggan and ask Mike to take a picture, the camera sidles around the bar.

As Mike and Riggan turn back to the bar we are effectively 180-degrees opposite to the first setup.

With cutting, a similar shift would have been motivated by changing the axis of action through shifts in staging.

Long-take shooting can’t mimic editing perfectly. An unbroken shot doesn’t yield the instantaneous change of angle supplied by a cut. But the scene can’t be allowed to go dead while the camera operator shifts to a new spot. So the interval between one sustained angle and another has to be filled up by dialogue and physical action. One way to motivate the change of camera position is through the actors’ changing positions. In the bar scene, the fan’s photo op motivates the camera move.

Alternatively, the actor’s gestures can provide some wedged-in bits. When Riggan and his wife have an intimate talk at his dressing table, he executes some business with a beer bottle that justifies shifting the angle to favor him.

Once we’re on him, he turns serious and the dialogue and facial expression motivate a push-in.

In normal shooting and cutting, the technique is fitted to the unfolding action. With a commitment to the long take, the director must fit the action to the technique. This is why, I think, González Iñárritu and his DP Emmanuel Lubezki spent months blocking the action on a sound stage and hiring stand-ins to move around the sets they’d built. Long before the actors came on the set, the filmmakers had mapped out many wedged-in bits of action they’d execute.

Giving up cutting forces other storytelling decisions. A narrative film typically distributes knowledge among its characters, and so the long-take camera must carve a path through the story world that either restricts or expands what we know. The mobile long take sticking with one character tends to restrict our knowledge. The long take that shifts among characters gives us a wider range of information. And whenever one character leaves another, there’s a forced choice: Which one does the narration follow? This is a choice in any storytelling medium, but in the long-take film the options are narrower: the issue is which one the camera will follow.

Birdman stays mostly with Riggan, but in the Complicating Action and Development sections, the narration needs to give us information on the doings of Mike, Lesley, and Sam. So, in another act of fitting and filling, the choreography must make those characters adjacent to some other action. The mazelike playing space of the film, in the bowels of the theatre, facilitates these comings and goings, so that we can drop one character and pick up another. When Lesley and Laura kiss, Mike interrupts them and Lesley hurls a hair dryer at him. He ducks out.

We could stay with Lesley and Laura, or follow Mike. We follow Mike so that we can shift to the new scene, with him visiting Riggan to complain about the pistol and then joining Sam on the roof. Nothing more of consequence will happen between Lesley and Laura; following Mike will lead us to the next story bit. The camera sees all that matters.

The long take’s muffled mimicry of orthodox editing pays some dividends. Arcs and short pans work when characters are close together, but if an encounter is played out in medium shot and one character pulls away, the camera is forced to pick a target. Whom will it follow? This effort becomes quite expressive when Mike is punching up Riggan’s table scene. Just as Mike takes over the rewriting of the lines, he hijacks the camera.

Things start with the usual circling shot.

As Mike’s pitch builds, he breaks from the neutral two-shot and circles Riggan. The camera favors him as he walks off, returns to the table and exhorts Riggan to turn up the tension. (“Fuck me!”)

Now that the two are in proximity, we can see Riggan, infected by Mike’s energy, deliver a more spirited line reading.

The scene ends with a segue to the next passage of walk-and-talk, as Sam comes onto the stage in depth.

In such scenes, the obstinate commitment to the long take itself motivates a dramatic effect. Later, Sam’s tirade about Riggan’s irrelevance gains force because the camera swings to her and stays fastened there.

In a cutting-based scene, there would have been the temptation to show Riggan’s reaction while Sam is unloading on him. True, we could get the same delayed revelation of his response by letting her tirade play out before cutting to him. But given our tacit adherence to the long take, and given the initial framing, we can’t see both of them. The refusal of editing itself justifies holding on her and suppressing his response. In the same way, showing her somewhat chastened pause and then following her walking past him motivates finally revealing his reaction.

A bonus: This scene’s concealment of the reverse angle—what is Sam seeing?—anticipates the film’s final image.

What about the long take’s effect on time? The plot’s tension relies upon the pressure of time. A great many actions are jammed into a short, continuous span. This is a common effect in films built around both a deadline and a confined space. Birdman‘s long take, with its rapid tracking movements and hurly-burly entrances and exits, enhances the pressure. But we need to note how much this result relies on another sort of “hidden editing.”

We often hear that the long take ties us to “real time.” And clock duration, with one minute onscreen equaling one in the story, is indeed a convenient, normative default. Yet suitably cued, a long take can halt duration in the present to give us flashbacks, as we’ve seen at least since Caravan (1934). Films by Angelopoulos, Jancsó, and others have shown that the long take can compress or expand story duration, and even replay events. The remarkable Iranian single-shot feature Fish and Cat of 2013 is full of ribbon-candy time wrinkles.

Once more, Birdman plays it straight. Like a normal movie, it uses sound bridges and night-to-day transitions to skip over stretches of story time. The film is a clear-cut example of the difference between story time (the years of Riggan’s career and the others’ lives), plot time (six days), and screen time (about 110 minutes). The central long take creates ellipses akin to traditional scenic links, and it does so in ways that are easy to grasp as we’re watching.

Intention: The expected virtues of ignorance

The crucial creative decision behind the film was the choice to shoot the extended take. González Iñárritu asserts that he didn’t model the technique on Rope but rather on the long takes of Max Ophuls. He also acknowledges that he was enraptured by Aleksandr Sokurov’s Russian Ark, a feature film that was indeed shot in one long take (thanks to video, but without CGI blending).

The status of the long take has changed across the history of film. In the first twenty years or so, it was more or less taken for granted as the most basic way to shoot a scene. Longer takes became rarer in most national cinemas during the 1920s, with editing becoming the preferred technique for building up action. Even complicated camera movements were consigned to comparatively brief shots.

The long take in today’s sense emerges most vividly in the early sound period, when directors began to use it creatively. During the 1930s, some long takes would be static or relatively so, in films like John Stahl’s Magnificent Obsession (1936) or musicals, especially those featuring Fred Astaire. Other long takes would make extensive use of camera movement. A great many early talkies begin with a fancy traveling shot before moving to more orthdox, editing-driven scenes. And the musicals of Busby Berkeley flaunted outrageous crane shots. In Japan, the USSR, France, Germany, and many countries, the sound cinema brought a renaissance of long takes, propelled by camera movement.

For the most part, this technical choice was felt to serve the story. You sustained the shot because the rhythm of performance benefited, or because you wanted to explore a space through a camera movement. In Dreyer’s Vampyr (1932), the tracking shots are designed to create uncertainties about where characters are when they go offscreen.

Behind the scenes, though, the filmmakers felt a certain pride in making a solid tracking or crane shot. A lengthy camera movement was a challenge because the cameras were big and bulky, they had to roll smoothly on tracks or other supports, lighting had to be controlled carefully, and equipment noise might be picked up.

Despite the difficulties, in the 1940s, some American directors seemed to have welcomed longer takes. The new interest probably owed something to new technology, such as the crab dolly’s ability to edge the camera through narrow spaces and turn in many directions. With complex camera movements easier, the takes could become longer. At a time when most films averaged eight to ten seconds per shot,Otto Preminger could make Daisy Kenyon (17 seconds), Centennial Summer (18 seconds), Laura (average 21 seconds), and Fallen Angel (33 seconds). There were as well Billy Wilder with Double Indemnity (14 seconds) and A Foreign Affair (16 seconds), Anthony Mann with Strange Impersonation (17 seconds) , and John Farrow with The Big Clock (20 seconds). This isn’t to mention the big long-take films of the period from The Lady in the Lake to Rope and Under Capricorn. The opening of Ride the Pink Horse contains a remarkable long-take tracking shot, and one shot in Welles’ Macbeth consumes a full camera reel.

It seems that for some directors sustaining the take was itself the main concern. The more complex the locale—a crowded room, a busy street, an overgrown landscape—the more that the sustained camera movement would be considered, at least by those in the know, as a difficult technical accomplishment.

The result was virtuosity, but with an alibi. Long takes are flashy. But…they can save money. (All those script pages covered fast, no need for editing.) They can be justified as realism. (The action can build over “real time.” Besides, don’t we see reality in a “continuous shot,” not cuts?) They can be motivated as subjective. (By staying with a character over a stretch of time, we become identified with him or her.) Regardless of these reasons, or excuses, there’s an undeniable bragadoccio associated with the protracted camera movement. Your peers in the industry will recognize what you’ve done, and cinephiles will applaud your bravado.

The Movie Brats seized on the virtuoso camera movement and long take as a mark of prowess. A new competition sprang up between Scorsese and DePalma, encompassing Raging Bull, Bonfire at the Vanities, Goodfellas, and Snake Eyes. Even a straight-to-video heist movie like Running Time (1997), choosing to hide its cuts in the Rope manner, has a bit of playground swagger. (Bruce Campbell is in it too.) No wonder that Christine Vachon remarks that shooting a whole scene in one is a “macho” choice.

It’s in this context that we can appraise González Iñárritu’s declared intentions. He was clearly drawn to the virtuosic side of the very long take, and his DP Emmanuel Lubezki had made the complex camera movement his signature with Children of Men and Gravity. After Snake Eyes showed that CGI could stitch together several long takes into a seamless whole, many directors saw that digital filmmaking could extend the shot beyond anything in analog cinematography. A new level of virtuosity was called for, not only the logistics of choreography but the skills of hiding the cuts. Do it right, you might even get tossed an Oscar or two.

The filmmakers justify Birdman‘s technique on familiar grounds. There’s realism:

We are trapped in continuous time. It’s only going in one direction. . . .This continuous shot [yields] an experience closer to what our real lives are like. (González Iñárritu)

There’s subjectivity.

I thought [the continuous take] would serve the dramatic tension and put the audience in this guy’s shoes in a radical way. (Lubezki)

To really not only understand and observe, but to feel, we have to be inside him. [The one shot] was the only way to do that. (González Iñárritu)

Is it showoffish? No, it serves the story.

All the choices we made were serving the purpose and dramatic tension of the characters, not about “Look how impressive we can be.” All the shots were meant to serve the narrative of the film. (González Iñárritu)

But there’s still virtuosity—art conceived as a triumph over self-imposed obstacles.

It was risky! Every scene—good or bad—I had to leave in. It was an endless strand of spaghetti that could choke me! Every note had to be perfect. (González Iñárritu)

I’ve never cared much for González Iñárritu’s films; they always seem too close to their influences. (My remarks on Babel are here.) Still, Birdman seems to me a fascinating example of how traditions can be revisited, or at least repackaged. I can also appreciate the skill with which the whole affair has been brought off. But I also wish that critics and mainstream filmmakers would be more accurate and comprehensive when talking about film form and style. Birdman isn’t a single-shot movie, and to insist on that point isn’t just pedantry. Part of the critic’s job is to look at what’s there, and a full account of the movie (which mine isn’t) would need to reckon in the other shots the film presents.

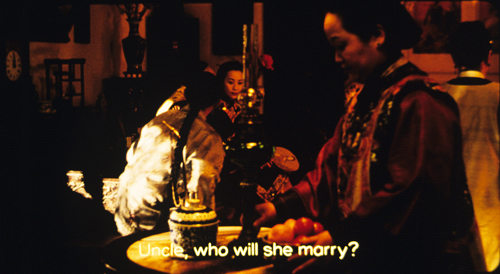

Critics should acknowledge that the long take has other expressive possibilities, some of them impossible to reduce to the patterns of continuity editing. To go back to Hou Hsiao-hsien, Flowers of Shanghai consists of thirty-five shots, nearly all made with a gently shifting camera. But Hou’s mobile long takes retain the intricacy of his static shots in earlier films. The camera may circle the action, but at each moment it’s not only following one character’s movement but drawing into view other movements, greater and lesser, nearer and farther off–the whole thing building up gestures and dialogue and facial reactions, as if by brush strokes, into a rich sense of characters coexisting in a story world and a social system. The result is a gradation of emphasis, to use Charles Barr’s neat phrase, that enriches our sense of the drama.

And sometimes the camera will not see all. Hou accepts the limits of the long take by making some action visible, some action partly visible, and some action unseen, even within the frame. Characters and props slide in to block the main action, sometimes shifting “against the grain” of the camera’s movement. The film’s visual flow doesn’t replicate the schemas of traditional scene analysis; often we must strain to see a gesture or reaction.

Hou’s isn’t the only way to use long takes, but it’s one that deserves more attention. Granted, he and other explorers in this vein will never win an Oscar. But our critics, too often dutifully repeating PR talking points, should signal that the enjoyable virtuosity of Birdman is only one way to employ the rich resources of cinema.

I’ll save for another time a reply to Riggan’s question to Tabitha: “What has to happen in a person’s life for them to become a critic anyway?”

My background information on Birdman‘s technique comes mostly from Jean Oppenheimer’s article, “Backstage Drama,” American Cinematographer 95, 12 (December 2014), 54-67. So does the quote from Lubezki above. A shooting script for the film is here. Information about the concealed digital cuts is in Bill Desowitz’s Indiewire piece.

Kristin’s model of four-part plot structure is discussed in several entries and in my essay “Anatomy of the Action Picture” and the book chapter “Three Dimensions of Film Narrative.”

The idea that a camera movement can recapitulate the pattern of analytical editing was floated by André Bazin and developed in detail by John Belton, “Under Capricorn: Montage Entranced by Mise-en-scène,” in his Cinema Stylists (Scarecrow, 1983), 39-58.

For more on the long take, see our entry “Stretching the shot.” The Christine Vachon quotation is linked there, as is De Palma’s sense of competing with Scorsese. The first essay in my Poetics of Cinema discusses trends in long-take shooting and camera movement in the 1940s. See as well Herb A. Lightman, “The Fluid Camera,” American Cinematographer 27, 3 (March 1946), 82, 102-103, and “‘Fluid’ Camera Gives Dramatic Emphasis to Cinematography,” American Cinematographer 34, 2 (February 1953), 63, 76-77. On Dreyer’s camera movements in Vampyr, see my book The Films of Carl Theodor Dreyer. I discuss Angelopoulos, Hou, and long-take staging generally in Figures Traced in Light: On Cinematic Staging. On this site, I discuss Hou’s staging practices here and here. And for discussions of intensified continuity style, see The Way Hollywood Tells It.

Two frames from Flowers of Shanghai (1998) are below, showing the camera’s slight movement around the central lantern and Pearl’s face, as well as the shift in the young man’s posture as he waits for an answer to his question. He’s in the process of clearing a bit of space for us to glimpse the older man, Hong, who’s sitting between him and Pearl.

P.S. 24 Feb 2015: Thanks to Paul Mollica for a name correction!

Say hello to GOODBYE TO LANGUAGE

DB here:

Godard is making trouble again. Adieu au langage–known now as Goodbye to Language– is doing better in the US than any of his films have done in the last thirty-some years. It has a per-screen average of $13,500, which is about twice that attained by Ouija in its opening last weekend.

But that average represents only two screens, and it’s going to be hard to expand because Goodbye to Language is in 3D. Many art houses would love to play it, but they lacked the money to upgrade to 3D during the big digital conversion of recent years. Even high-powered venues in New York, Los Angeles, and Chicago don’t have 3D installed. Here in Madison we’re showing it as a benefit for our Cinematheque. But the film’s prospects may be brightening.

Re-seeing it (twice) at the Vancouver International Film Festival back in September, I was struck by a few more ideas about it. Kristin and I avoid listicles, but after writing an expansive entry on the film, all I’ve got at this point is some scattered observations. Two ragtag comments are semi-spoilers, and I’ll warn you beforehand.

The Power of post As far as I can tell, Godard hasn’t used the converging-lens method to create 3D during shooting. Instead of “toeing-in” his cameras, he set them so that the lenses are strictly parallel. He and his DP Fabrice Aragno apparently relied on software to generate the startling 3D we see onscreen.

This reminds me that postproduction has long been a central aspect of Godard’s creative process. Of course he creates marvelous shots while filming, but ever since Breathless (À bout de souffle, 1960), when he yanked out frames from the middle of his shots, he has always made post-shooting work more than simply trimming and polishing. His interruptive aesthetic is made possible by editing that wedges in intertitles (sometimes the same one several times). He breaks off beautiful shots and drops in bursts of music that snap off just before they cadence.

In both sound and image, the post-production process for Godard is a kind of transformation, an openly admitted re-writing of what came from the camera. He slaps graffiti on his own film. In Narration in the Fiction Film, I argued that our sense of a Godard film being “told” or narrated by the director proceeds partly from his ability to create the impression of a sort of Cineaste-Emperor, a sovereign master who is governing what we see and hear at any given moment. The collage principle suggests someone behind the scenes pasting these fragments together. Not only his commentary (once whispered, now croaked) but every shot-change and bit of music and noise, every intertitle and look to the camera all bear witness to Godard as God. Before he cut a strip of film; now he twiddles a knob or guides a slider. In all cases, we still feel his playful, exasperating hand.