Archive for the 'Readers’ Favorite Entries' Category

David Koepp: Making the world movie-sized

Stir of Echoes (1999).

DB here:

For a long time, Hollywood movies have fed off other Hollywood movies. We’ve had sequels and remakes since the 1910s. Studios of the Golden Era relied on “swipes” or “switches,” in which an earlier film was ripped off without acknowledgment. Vincent Sherman talks about pulling the switch at Warners with Crime School (1938), which fused Mayor of Hell (1933) and San Quentin (1937). Films referred to other films too, sometimes quite obliquely (as seen in this recent entry).

People who knock Hollywood will say that this constant borrowing shows a bankruptcy of imagination. True, there can be mindless mimicry. But any artistic tradition houses copycats. A viable tradition provides a varied number of points of departure for ambitious future work. Nothing comes from nothing; influences, borrowings, even refusals–all depend on awareness of what went before. The tradition sparks to life when filmmakers push us to see new possibilities in it.

From this angle, the references littering the 1960s-70s Movie Brats’ pictures aren’t just showing off their film-school knowledge. Often the citations simply acknowledge the power of a tradition. When Bonnie, Clyde, and C. W. Moss hide out in a movie theatre during the “We’re in the Money” sequence from Gold Diggers of 1933, the scene offers an ironic sideswipe at their bungled bank job, and a recollection of Warner Bros. gangster classics. When a shot in Paper Moon shows a marquee announcing Steamboat Round the Bend, it evokes a parallel with Ford’s story about an older man and a girl. Even those who despised the tradition, like Altman, were obliged to invoke it, as in the parodic reappearances of the main musical theme throughout The Long Goodbye.

But tradition is additive. As the New Hollywood wing of the Brats—Lucas, Spielberg, De Palma, Carpenter, and others—revived the genres of classic studio filmmaking, they created modern classics. The Godfather, Jaws, Star Wars, Carrie, Raiders of the Lost Ark, and others weren’t only updated versions of the gangster films, horror movies, thrillers, science-fiction sagas, and adventure tales that Hollywood had turned out for years. They formed a new canon for younger filmmakers. Accordingly, the next wave of the 1980s and 1990s referenced the studio tradition, but it also played off the New Hollywood. For “New New Hollywood” directors like Robert Zemeckis and James Cameron, their tradition included the breakthroughs of filmmakers only a few years older than themselves.

So today’s young filmmaker working in Hollywood faces a task. How to sustain and refresh this multifaceted tradition? One filmmaker who writes screenplays and occasionally directs them has found some lively solutions.

From the ’40s to the ’10s

The Trigger Effect (1996).

David Koepp was fourteen when he saw Star Wars and eighteen when he saw Raiders. By the time he was twenty-nine he was writing the screenplay for Jurassic Park. Later he would provide Spielberg with War of the Worlds (2005) and Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull (2008). Across the same period he worked with De Palma (Carlito’s Way, 1993; Mission: Impossible, 1996; Snake Eyes, 1998), and Ron Howard (The Paper, 1994), as well as younger directors like Zemeckis (Death Becomes Her, 1992), Raimi (Spider-Man, 2002), and Fincher (Panic Room, 2002). The young man from Pewaukee, Wisconsin who grew up with the New Hollywood became central to the New New Hollywood, and what has come after.

He spent two years at UW–Madison, mostly working in the Theatre Department but also hopping among the many campus film societies. He spent two years after that at UCLA, enraptured by archival prints screened in legendary Melnitz Hall. The result was a wide-ranging taste for powerful narrative cinema. He came to admire 1970s and 1980s classics like Annie Hall, The Shining, and Tootsie. As a director, Koepp resembles Polanski in his efficient classical technique; his favorite movie is Rosemary’s Baby, and one inspiration for Apartment Zero (1988) and Secret Window was The Tenant. You can imagine Koepp directing a project like Frantic or The Ghost Writer.

Old Hollywood is no less important to Koepp. Among his favorites are Double Indemnity, Mildred Pierce, and Sorry, Wrong Number. In conversation he tosses off dozens of film references, from specifically recalled shots and scenes to one-liners pulled from classics, like the “But with a little sex” refrain from Sullivan’s Travels.

It’s not mere geek quotation-spotting, either. The classical influence shows up in the very architecture of his work. He creates ghost movies both comic and dramatic, gangster pictures, psychological thrillers, and spy sagas. The Paper revives the machine-gun gabfests of His Girl Friday, while Premium Rush gives us a sunny update of the noir plot centered on a man pursued through the city by both cops and crooks.

One of the greatest compliments I ever got (well, it seemed like a compliment to me, anyway) was when Mr. Spielberg told me I’d missed my era as a screenwriter–that I would have had a ball in the 40s.

Like his contemporary Soderbergh, Koepp sustains the American tradition of tight, crisp storytelling. He also thinks a lot about his craft, and he explains his ideas vividly. His interviews and commentary tracks offer us a vein of practical wisdom that repays mining. It was with that in mind that I visited him in his Manhattan office to dig a little deeper.

Humanizing the Gizmo

Today, the challenge is the tentpole, the big movie full of special effects. A tentpole picture needs what Koepp calls its Gizmo, its overriding premise, “the outlandish thing that makes the big movie possible.” The Gizmo in in Jurassic Park is preserved DNA; the Gizmo in Back to the Future is the flux capacitor. “The more outlandish the Gizmo, the harder it is to write everybody around it.” The problem is to counterbalance scale with intimacy. “You need to offset what’s ‘up there’ [Koepp raises his arm] with things that are ‘down here’ [he lowers it].” This involves, for one thing, humanizing the characters. A good example, I think, is what he did with Jurassic Park.

Crichton’s original novel has a lot going for it: two powerful premises (reviving dinosaurs and building a theme park around them), intriguing scientific speculation, and a solid adventure framework. But the characterizations are pallid, the scientific monologues clunky, and the succession of chases and narrow escapes too protracted.

The film is more tightly focused. In the novel, Dr. Grant is an older widower and has no romantic relation to Ellie; here they’re a couple. In the original, Grant enjoys children; in the film, he dislikes them. Accordingly, Koepp and Spielberg supply the traditional second plotline of classic Hollywood cinema. Alongside the dinosaur plot there’s an arc of personal growth, as Grant becomes a warmer father-figure and he and Ellie become short-term surrogate parents for Tim and Alexa.

Similarly, Crichton’s hard-nosed Hammond turns into a benevolent grandfather; in the film, his defensive attitude toward the park’s project collapses when his children are in danger. Even Ian Malcolm, mordantly played by Jeff Goldblum (stroking some of the most unpredictable line-readings in modern cinema), can be seen as the wiseacre uncle rather than the smug egomaniac of the novel.

Crichton’s tale of scientific overreach becomes a family adventure. Koepp’s consistent interest in the crises facing a family meshes nicely with the same aspect of Spielberg’s work, and it gives the film an appeal for a broad audience. In the original, Tim is a boy wonder, well-informed about dinosaurs and skilled at the computer. Koepp’s screenplay shares out these areas of expertise, making Lex the hacker and letting her save the day by rebooting the park’s defense system. There’s a model of courage and intelligence for everybody who sees the movie.

While giving Crichton’s novel a narrative drive centered on the surrogate family, Koepp also creates a more compressed plot. For one thing, he slices out the chunks of scientific explanation that riddle the novel. The main solution came, Koepp says, when Spielberg pointed out that modern theme parks have video presentations to orient the visitors. Koepp and Spielberg created a short narrated by “Mr. DNA,” in an echo of the middle-school educational short “Hemo the Magnificent.” The result provides an entertaining bit of exposition that condenses many scenes in the book. Why Mr. DNA has a southern accent, however, Koepp can’t recall.

Compression like this allows Koepp to lay the film out in a well-tuned structure. Most of his work fits the four-part model discussed by Kristin and me so often (as here). In Storytelling in the New Hollywood, she shows how Jurassic displays the familiar pattern of goals formulated (part one), recast (part two), blocked (part three), and resolved (part four). When I visited Koepp, he was laying out 4 x 6 cards for his screenplay for Brilliance, seen above. He remarked that the array fell into four parts, with a midpoint and an accelerating climax.

For a smaller-scale example of compression, consider a classic convention of heist movies: the planning session. In Mission: Impossible, Ethan Hunt reviews his plan for accessing the computer files at CIA headquarters. As he starts, the reactions of the two men he’s recruiting foreshadow what they’ll do during the break-in: the sinister calculation of Krieger (Jean Reno), in particular, is emphasized by De Palma’s direction. Ethan’s explanation of the security devices shifts to voice-over and we leave the train compartment to follow an ineffectual bureaucrat making his way into the secured room. (The room and the gadgets were wholly made up for the film; the Langley originals were far more drab and low-tech.)

Everything that will matter later, including the heat-sensitive floor and the drop of moisture that can set off the alarms, is laid out visually with Ethan’s explanation serving as exposition. Like the Mr. DNA short, this set-piece, extravagant in the De Palma mode, serves to specify how things in this story will work. Here, however, the task involves what Koepp calls “baiting the suspense hook. “ Each detail is a security obstacle that Hunt’s team will have to overcome.

The world is too big

Panic Room.

The overriding problem, Koepp says, is that the world is too big for a movie. There are too many story lines a plot might pursue; there are too many ways to structure a scene; there are too many places you might put the camera. You need to filter out nearly everything that might work in order to arrive at what’s necessary.

At the level of the whole film, Koepp prefers to lay down constraints. He likes “bottles,” plots that depend on severely limited time or space or both. The Paper ’s action takes 24 hours; Premium Rush’s action covers three. Stir of Echoes confines its action almost completely to a neighborhood, while Secret Window mostly takes place in a cabin and the area around it. Even those plots based on journeys, like The Trigger Effect and War of the Worlds, develop under the pressure of time.

Panic Room is the most extreme instance of Koepp’s urge for concentration. He wanted to have everything unfold in the house during a single night and show nothing that happened outside. (He even thought about eliminating nearly all dialogue, but gave that up as implausible: surely the home invaders would at least whisper.) As it worked out, the action in the house is bracketed by an opening scene and closing scene, both taking place outdoors, but now he thinks that these throw the confinement of the main section into even sharper relief. The result is a tour de force of interiority—not even flashbacks break us out of the immense gloom of the place—and in the tradition of chamber cinema it gives a vivid sense of the overall layout of the premises.

Panic Room, like Premium Rush, relies on crosscutting to shift us among the characters and compare points of view on the action. But another way to solve the world-is-too-big problem is to restrict us to what only one characters sees, hears, and knows. This is what Polanski does in Rosemary’s Baby, which derives so much of its rising tension from showing only what Rosemary experiences, never the plotting against her. Koepp followed the same strategy in War of the Worlds. Most Armageddon films offer a global panorama and a panoply of characters whose lives are intercut. But Koepp and Spielberg decided to show no destroyed monuments or worldwide panics, not even via TV broadcasts. Instead, we adhere again to the fate of one family, and we’re as much in the dark as Ray Ferrier and his kids are. Even when Ray’s teenage son runs off to join the military assault, we learn his fate only when Ray does.

Less stringent but no less significant is the way the comedy Ghost Town follows misanthropic dentist Bertram Pincus (Ricky Gervais). After a prologue showing the death of the exploitative exec played by Greg Kinnear, we stay pretty much with Pincus, who discovers that he can see all the ghosts haunting New York. Limiting us to what he knows enhances the mystery of why these spirits are hanging around and plaguing him.

Yet sticking to a character’s range of knowledge can create new problems. In Stir of Echoes, Koepp’s decision to stay with the experience of Tom Witzky (Kevin Bacon) meant that the film would give up one of the big attractions of any hypnosis scene—seeing, from the outside, how the patient behaves in the trance. Koepp was happy to avoid this cliché and followed Richard Matheson’s original novel by presenting what the trance felt like from Tom’s viewpoint.

The premise of Secret Window, laid down in Stephen King’s original story, obliged Koepp to stay closely tied to Mort Rainey’s range of knowledge. In his director’s commentary, Koepp points out that this constraint sacrifices some suspense, as during the scene when Mort (Johnny Depp) thinks someone else is sneaking around his cabin. We can know only what he sees, as when he glimpses a slightly moving shoulder in the bathroom mirror.

Having nothing to cut away to, Koepp says, didn’t allow him to build maximum tension. Still, the film does shift away from Mort occasionally, using a little crosscutting during phone conversations and at the climax. During the big revelation, Koepp switches viewpoint as Mort’s wife arrives at the cabin; but this seems necessary to make sure the audience realizes that the denouement is objective and not in Mort’s head.

Once you’ve organized your plot around a restrictive viewpoint, breaking it can be risky. About halfway through Snake Eyes, Koepp’s screenplay shifts our attachment from the slimeball cop Rick Santoro (Nicolas Cage) to his friend Kevin (Gary Sinese). We see Kevin covering up the assassination. In the manner of Vertigo, we’re let in on a scheme that the protagonist isn’t aware of. This runs the risk of dissipating the mystery that pulls the viewer through the plot. Sealing the deal, Snake Eyes then gives us a flashback to the assassination attempt. Not only does this sequence confirm Kevin’s complicity, it turns an earlier flashback, recounted by Kevin to Rick, into a lie. Although lying flashbacks have appeared in other films, Koepp recalls that the preview audience rejected this twist. The lying flashback stayed in the film because the plot’s second half depended on the early revelation of Kevin’s betrayal.

Because the world is too big, you need to ask how to narrow down options for each scene as well as the whole plot. Fiction writers speak of asking, “Whose scene is it?” and advise you to maintain attachment to that character throughout the scene. The same question comes up with cinema.

Say the husband is already in the kitchen when the wife comes in. If you follow the wife from the car, down the corridor, and into the kitchen, we’re with her; we’ll discover that hubby is there when she does. If instead we start by showing hubby taking a Dr. Pepper out of the refrigerator and turning as the wife comes in, it’s his scene. Note that this doesn’t involve any great degree of subjectivity; no POV shot or mental access is required. It’s just that our entry point into the scene comes via our attachment to one character rather than another.

Here’s a moment of such a directorial choice in Stir of Echoes. Maggie comes home to find her husband Tom, driven by demands from their domestic ghost, digging up the back yard. Koepp could have gotten a really nice depth composition by showing us a wide-angle shot of Tom and his son tearing up the yard, with Maggie emerging through the doorway in the background. That way, we would have known about the mess before she did.

Instead, Koepp reveals that Tom’s mind has gone off the rails by showing Maggie coming out onto the back porch and staring. We hear digging sounds. “Oh…kay…” she sighs.

She walks slowly across the yard, passing their son and eventually confronting Tom, who’s so absorbed he doesn’t hear her speak to him.

Once you’ve made a choice, though, other decisions follow. So Maggie provides our pathway into the scene, but how do we present that? Koepp asks on his commentary track:

What do you think? Is it better to do what I did here, which is pull back across the yard and slowly reveal the mess he’s made, or should I have cut to her point of view of the big messy yard right in the doorway? I went for lingering tension rather than the sudden cut to what she sees. You might have done it differently.

Sticking with a central character throughout a scene can have practical benefits too. Koepp points out that his choice for the Stir of Echoes shot was affected by the need to finish as the afternoon light was waning. Similarly, in the forthcoming Jack Ryan, Koepp includes an action scene showing an assault on a helicopter carrying the hero. Koepp’s script keeps us inside the chopper as a door is blown off and Ryan is pinned under it. Rather than including long shots of the attack, it was easier and less costly to composite in partial CGI effects as bits of action glimpsed in the background, all seen from within the chopper.

Saving it, scaling it, buttoning it

Ghost Town.

Because the world is too big, you can put the camera anywhere. Why here rather than there?

Standard practice is to handle the scene with coverage: You film one master shot playing through the entire scene, then you take singles, two-shots, over-the-shoulders, and so on. Actors may speak their lines a dozen times for different camera setups, and the editor always has some shot to cut to. Alternatively, the director may speed up coverage by shooting with many cameras at once. Some of the dialogues in Gladiator were filmed by as many as seven cameras. “I was thinking,” said the cinematographer, “somebody has to be getting something good.”

Koepp opposes both mechanical and shotgun coverage. Whenever he can, he seizes on a chance to handle several pages of dialogue in a single take (a “one-er”). “There’s a great feeling when you find the master and can let it run.” Sustained shots work especially well in comedy because they allow the actors to get into a smooth verbal rhythm. The hilariously cramped three-shot in Ghost Town (shown above) could play out in a one-er because Koepp and Kamps meticulously prepared its rapid-fire dialogue exchange.

When cutting is necessary, Koepp favors building scenes through subtle gradations of scale, saving certain framings for key moments. He walked me through a striking example, a five-minute scene in Panic Room.

Meg Altman and her daughter Sarah have been besieged by home invaders. Meg has managed to flee from their sealed safety room, but Sarah is trapped there and is slipping into a diabetic coma while the two attackers hold her captive. Now two policemen, summoned by Meg’s husband, come calling. The criminals are watching what’s happening on the CC monitor. Meg must drive the cops away without arousing suspicion, or the invaders will let Sarah die.

Koepp’s scene weaves two strands of suspense, the peril of the girl and Meg’s tactics of dealing with the cops. One cop is ready to leave her alone, but another is solicitous. Meg offers various excuses for why her husband called them—she was drunk, she wanted sex—but the concerned cop persists. The scene develops through good old shot/ reverse-shot analytical editing, with variations in scale serving to emphasize certain lines and facial reactions.

At the climax, the concerned officer says that if there’s anything she wants to tell them but cannot say explicitly, she could blink her eyes as a signal. When he asks this, Fincher cuts in to the tightest shot yet on him. The next shot of Meg reveals her decision. She refuses to blink.

Fincher saved his big shot of the cop for the scene’s high point. The cop’s line of dialogue motivates the next shot, one that keeps the audience in suspense about how Meg will respond. What I love about this shot is that everybody in the theatre is watching the same thing: her eyes. Will she blink?

Building up a scene, then, involves holding something back and saving it for when it will be more powerful. An extreme case occurs in Rosemary’s Baby. I asked Koepp about a scene that had long puzzled me. Rosemary and Guy have joined their slightly dotty older neighbors, the Castevets, for drinks and dinner. Having poured them all some sherry, Castavet settles into a chair far from the sofa area, where the other three are seated.

Mr. Castevet continues to talk with them from this chair, still framed in a strikingly distant shot.

Koepp agreed that virtually no director today would film the old man from so far back. Can’t you just see the tight close-up that would hint at something sinister in his demeanor?

We found the justification in the next scene, the dinner. This is filmed with one of those arcing tracks so common today when people gather at a table, but here it has a purpose. The shot’s opening gives us another instance of the Castevets’ social backwardness, as Rosemary saws away at her steak. (You’d think people in league with Satan could afford a better cut of meat.)

Mr. Castevet proceeds to denounce organized religion and to flatter Guy’s stage performance in Luther. As the camera moves on, the fulcrum of the image becomes the old man, now seen head-on from a nearer position.

“He was saving it,” said Koepp. “He was making us wait to see this guy more closely—and even here, he’s postponing a big close-up.”

Yet having given with one hand, Polanski takes away with the other. Next Rosemary is doing the dishes with Mrs. Castevet while the men share cigarettes in the parlor. Because we’re restricted to Rosemary’s range of knowledge, we see what she sees: nothing but wisps of smoke in the doorway.

We’ll later realize that this offscreen conversation between Roman and Guy seals the deal over Rosemary’s first-born.

Empty doorways form a motif in the film (the major instance has been much commented on), and they too point up Polanski’s stinginess—or rather, his economy. He doles his effects out piece by piece, and the result is a mix of mystery and tension that will pay off gradually. Koepp likewise exploits the sustained empty frame, most notably at the end of Ghost Town.

Building up scenes in this way encourages the director to give each shot a coherence and a point. Koepp recalls De Palma’s advice: “For every shot, ask: What value does it yield?” Spielberg comes to the set with clear ideas about the shots he wants, and when scouting or rehearsing he’s trying to assure that the set design, the lighting, and the blocking will let him make them. As Koepp puts it, Spielberg is saying: “This is my shot. If I can’t do X, I don’t have a shot.”

Compared to the swirling choppiness on display in much modern cinema–say, at the moment, Leterrier’s Now You See Me–Koepp’s style is sober and concentrated. For him, the director should strive to turn a shot into a cinematic statement that develops from beginning to end. The slow track rightward in Stir of Echoes has its own little arc, following Maggie leaving the porch, moving past their son, concluding on Tom as she speaks to him and he suddenly turns to her (at the cut).

Accordingly a shot can end with a little bump, a “button” that’s the logical culmination of the action. Something as simple as Rosemary turning her head to look sidewise is a soft bump, impelling the POV shot of the doorway. Something more forceful comes in Stir of Echoes, when the people at the party chatter about hypnosis and the camera slowly coasts in on Tom, gradually eliminating everybody else until in close-up he says cockily, “Do me.”

Shooting all the conversational snippets among various characters would have required lots of coverage, and it was cleaner to keep them offscreen as the camera drew in on Tom. With the suspense raised by the track-in (a move suggested by De Palma), Koepp could treat Tom’s line as a dramatic turning point and the payoff for the shot.

In a comic register, the button can yield a character-based gag. Bertram Pincus is warming to the Egyptologist Gwen; he’s even bought a new shirt to impress her. They discuss how his knowledge of abcessed teeth can help her research into the death of a Pharaoh. A series of gags involves Pincus’ discomfiture around the mummy, with Gwen making him touch and smell it. The two-shot, Koepp says, is still the heart of dialogue cinema, especially in comedy.

Bertram offers Gwen a “sugar-free treat” and shyly turns away. The gesture reveals that he’s forgotten to take the price tag off his shirt.

This buttons up the shot with an image that reveals the characters’ attitudes. Pincus’s error undercuts his self-important explanation of the pharoah’s oral hygiene. Yet it’s a little endearing; he was in such a hurry to make a good impression he forgot to pull the tag. At the same, having Gwen see the tag shows her sudden awareness that Bertram’s offensiveness masks his social awkwardness. As Koepp puts it: “He bought a new shirt for their meeting, she realizes it, and she finds it sweet.” She’s starting to like him, as is suggested when she turns and matches his posture.

Koepp gives the whole scene its button by cutting back to a long shot as Pincus murmurs, “Surprisingly delightful.” Is he referring to his candy, or his growing enjoyment of Gwen’s company? Both, probably: He’s becoming more human.

Like the Movie Brats and the New New Hollywood filmmakers, Koepp is inspired by other films. And as with them, his usage isn’t derivative in a narrow sense. He treats a genre convention, a situation, an earlier Gizmo, or a fondly-remembered shot as a prod to come up with something new. Borrowing from other films isn’t unoriginal; in mainstream filmmaking, originality usually means revising tradition in fresh, personal ways.

There’s a lot more to be learned about screenwriting and directing from the work of David Koepp. He told me much I can’t squeeze in here, about the Manhattan logistics of shooting Premium Rush and about the newsroom ethnography behind The Paper, written with his brother Stephen. What I can say is this: He really should write a book about his craft. I expect that it would be as good-natured as his lopsided grin and quick wit. It would illuminate for us the range of the creative choices available in the New Hollywood, the New New Hollywood, and the Newest Hollywood.

Thanks to David for giving me so much of his time. We initially came into contact when he wrote to me after my blog post on Premium Rush, which now contains a P.S. extracted from his email. We had never met, and I’m glad we finally caught up with each other.

I’ve supplemented my conversation with David with ideas drawn from his DVD commentaries for Stir of Echoes, Secret Window, and Ghost Town. Soderbergh provides intriguing observations on the commentary track for Apartment Zero. I’ve also found useful comments in these published interviews: “David Koepp: Sincerity,” in Patrick McGilligan, ed., Backstory 5: Interviews with Screenwriters of the 1990s (University of California Press, 2010), 71-89; Joshua Klein “Writer’s Block, [1999],” at The Onion A.V. Club; Steve Biodrowski, “Stir of Echoes: David Koepp Interviewed [2000]” at Mania; Josh Horowitz, “The Inner View–David Koepp [2004]” at A Site Called Fred; “Interview: David Koepp (War of the Worlds)[2005]” at Chud.com; Ian Freer, “David Koepp on War of the Worlds [2006],” at Empire Online; “Peter N. Chumo III, “Watch the Skies: David Koepp on War of the Worlds,” Creative Screenwriting 12, 3 (May/June 2005), 50-55; E. A. Puck, “So What Do You Do, David Koepp? [2007]” at Mediabistro; Nell Alk, “David Koepp, John Kamps Talk Premium Rush, Joseph Gordon-Levitt’s Fearlessness and Pedestrian ‘Scum’ [2012]” at Movieline; and Fred Topel, “Bike-O-Vision: David Koepp on Premium Rush and Jack Ryan [2012]” at Crave Online.

Vincent Sherman discusses screenplay switching in People Will Talk, ed. John Kobal (Knopf, 1986), 549-550. My quotation from Gladiator‘s DP comes from The Way Hollywood Tells It, p. 159. For more on David Fincher’s way with characters’ eyes, see this entry on The Social Network.

Pandora’s digital box: End times

35mm projection booth at Market Square Cinema, Madison, Wisconsin; 10 May 2013.

DB here:

When exactly did film end? According to the mass-market press, here are some terminal dates.

July 2011: Technicolor closes its Los Angeles laboratory.

October 2011: Panavision, Aaton, and Arri all announce that they will stop manufacturing film cameras.

November 2011: Twentieth Century Fox sends out a letter asserting that it will cease supplying theatres with 35mm prints “within the next year or two.”

January 2012: Eastman Kodak files for bankruptcy protection.

March 2013: Fuji stops selling negative and positive film stock for 35mm photography.

Each of these events looked like turning points, but now they seem merely phases within a gradual shift. After all, the digital conversion of cinema has been in the works for about fifteen years. The key events–the formation of a studio consortium to set standards, the cooperation of technical agencies and professional associations, the lobbying for 3D by top-money directors–didn’t get as much coverage. Because so many maneuvers took place behind the scenes and unfolded slowly, digital cinema seemed very distant to me. To understand the whole process, I had to do some research. Only in hindsight did the quiet buildups and sudden jolts form a pattern.

On the production end, it seems likely that filmmakers will continue to migrate to digital formats at a moderate pace. Proponents of 35mm are fond of pointing out that six of 2012’s Oscar-nominated pictures were shot wholly or partly on film. (To which you might well respond, Who cares about Oscar nominations? I would agree with you.) Yet even 35mm adherent Wally Pfister, DP for Christopher Nolan, admits that within ten years he will probably be shooting digital.

What about the other wings of the film industry, distribution and exhibition? Put aside distribution for a moment. Digital exhibition was the central focus of the blog series that became my e-book Pandora’s Digital Box. There I try to trace the historical process that led up to the big changes of 2009-early 2012.

Today, a year after Pandora’s publication, everybody knows that 35mm exhibition of recent releases is almost completely finished. But let’s explore things in a little more detail, including poking at some nuts and bolts. As we go, I’ll link to the original blog entries.

Top of the world!

35mm print of Warm Bodies about to be shipped out from Market Square Cinemas, Madison, Wisconsin; 10 May 2013.

The overall situation couldn’t be plainer. At the end of 2012, reports David Hancock of IHS Screen Digest, there were nearly 130,000 screens in the world. Of these, over two-thirds were digital, and a little over half of those were 3D-capable.

Northern European countries have committed heavily to the new format. The Netherlands, Denmark, and Norway are fully digital, while the UK is at 93% saturation and France is at 92%. Both national and EU funds have helped fund the switchover. Hancock reports that in Asia, Japanese screens are 88% digital, and South Korean ones are 100%. China is the growth engine. Rising living standards and swelling attendance have triggered a building frenzy. Over 85%, or 21,407 screens are already digital, and on average, each day adds at least eight new screens.

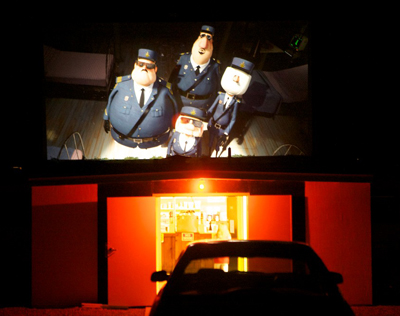

In the US and Canada, there were at end 2012 still over 6400 commercial analog screens, or about 15% of the nearly 43,000 total. My home town, Madison, Wisconsin, has a surprising number of these anachronisms. One multiplex retains at least two first-run 35mm screens. Five second-run screens at our Market Square multiplex have no digital equipment. That venue ran excellent 2D prints of Life of Pi (held over for seven weeks) and The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey. It’s currently screening many recent releases, including the incessantly and mysteriously popular Argo. In addition, our campus has several active 35mm venues (Cinematheque, Chazen Museum, Marquee). Our department shows a fair amount of 35mm for our courses as well; the last screening I dropped in on was The Quiet Man in the very nice UCLA restoration.

Unquestionably, however, 35mm is doomed as a commercial format. Formerly, a tentpole release might have required 3000-5000 film prints; now a few hundred are shipped. Our Market Square house sometimes gets prints bearing single-digit ID numbers. Jack Foley of Focus Features estimates that only about 5 % of the copies of a wide US release will be in 35mm. A narrower release might go somewhat higher, since art houses have been slower to transition to digital. Focus Features’ The Place Beyond the Pines was released on 1442 screens, only 105 (7%) of which employed 35mm.

In light of the rapid takeup of digital projection, Foley expects that most studios will stop supplying 35mm copies by the end of this year. David Hancock has suggested that by the end of 2015, there won’t be any new theatrical releases on 35mm.

Correspondingly, projectionists are vanishing. In Madison, Hal Theisen, my guide to digital operation in Chapter 4 of Pandora, has been dismissed. The films in that theatre are now set up by an assistant manager. Hal was the last full-time projectionist in town.

The wholesale conversion was initiated by the studios under the aegis of their Digital Cinema Initiatives corporation (DCI). The plan was helped along, after some negotiation, by the National Association of Theatre Owners. Smaller theatre chains and independent owners had to go along or risk closing down eventually. The Majors pursued the changeover aggressively, combining a stick—go digital or die!—with several carrots: lower shipping costs, higher ticket prices for 3D shows, no need for expensive unionized projectionists, and the prospect of “alternative content.”

The conversion to DCI standards was costly, running up to $100,000 per screen. Many exhibitors took advantage of the Virtual Print Fee, a subsidy from the distributors that paid into a third-party account every time the venue booked a film from the Majors. There were strings attached to the VPF. The deals are still protected by nondisclosure agreements, but terms have included demands that exhibitors remove all 35mm machines from the venue, show a certain number of the Majors’ films, equip some houses for 3D, and/or sign up for Network Operations Centers that would monitor the shows.

The biggest North American chains are Regal, AMC, and Cinemark. They control about 16,500 screens and own fifty-three of the sixty top-grossing US venues. The Big Three benefited considerably from the conversion. By forming the consortium Digital Cinema Solutions, they were able to negotiate Wall Street financing for their chains’ digital upgrade. They also formed National Cinemedia, a company that supplied FirstLook, a preshow assembly of promos for TV shows and music. Under the new name of NCM Network, the parent company now links 19,000 screens for advertising purposes. NCM also supplies alternative content to over 700 screens under the Fathom brand: sports, musical acts, the Metropolitan Opera, London’s National Theatre, and other items that try to perk up multiplex business in the middle of the week.

The digital conversion has coincided with—some would say, led to—a greater consolidation of US theatre chains. Last year the Texas-based Rave circuit was dissolved, and 483 of its screens, all digital, were picked up by Cinemark. More recently, the Regal chain gained over 500 screens by acquiring Hollywood Theatres. The biggest move took place in May 2012 when the AMC circuit was bought for $2.6 billion by Dalian Wanda Group, a Chinese real estate firm. Combined with Wanda’s 750 mainland screens, this acquisition created what may be the biggest cinema chain in the world. Wanda has declared its intent to invest half a billion dollars in upgrading AMC houses.

Meanwhile, vertical integration is emerging. In 2011, Regal and AMC founded Open Road Films, a distribution company. It has handled such high-profile titles as The Grey, Killer Elite, End of Watch, Side Effects, and The Host. Cinedigm, which began life as a third-party aggregator to handle VPFs, has moved into distribution too, billing itself as a company merging theatrical and home release strategies tailored to each project.

It has become evident that the digital revolution in exhibition permits American studio cinema a new level of conquest and control. Distribution, we’ve long known, is the seat of power in nearly all types of cinema. Whatever the virtues of YouTube, Vimeo, and other personal-movie exhibition platforms, film’s long-standing public dimension, the gathering of people who surrender their attention to a shared experience in real time, is still largely governed by what Hollywood studios put into their pipeline.

On the margins and off-center

View of Madagascar from the Sky-Vu Drive-In, 2012. Photo by Duke Goetz.

While the Big Three grew stronger, what became of smaller fry? John Fithian of NATO suggested that any cinema with fewer than ten screens could probably not afford the changeover, and David Hancock suggested that up to 2000 screens might be lost. Recent speculation is that drive-ins will be especially hard hit. Pandora’s Digital Box, as blog and then book, surveyed those most at risk: the small local cinemas and the art houses.

I fretted about the loss of small-town theatres, not least because I grew up with them. Data on such local venues are hard to get, so for the blog and the book I went reportorial and visited two Midwestern towns. The blogs related to them are here and here.

The long-lived Goetz theatres in Monroe, Wisconsin, consist of a downtown triplex and the Sky-Vu drive-in. They’re run by Robert “Duke” Goetz, whose grandfather built the movie house back in 1931. Duke is a confirmed techie and showman. He designs and cuts ads and music videos to fill out his show, and he personally converted all his screens to 7.1 sound. So it’s no surprise that he’s a fan of digital cinema. But back in December his digital upgrade took place during the worst box-office weekend since 2008–a bad omen, if you believe in omens.

Seventeen months later, Duke reports more cheerful news. Everything has gone according to plan and budget. The company that installed the equipment, Bright Star Systems of Minneapolis, has proven reliable and excellent in answering questions. Duke especially likes the fact that digital projection allows him to “play musical chairs with the click of a mouse.”

I can move movies from screen to screen in short order or download from the Theatre Management System to any and all theatres at one time, so when the weather is damn cold, for Monday -Thursday screening I’ll play the shorter movies in the biggest house. . . . I am now able to start the movies from the box office with software that accesses the TMS, so it’s just like being at the projector. It saves my guys time and keeps them where the action is.

Duke programs his offerings to suit the tastes of the town, and for the most part, he can get the films he wants. Attendance at the three-screener has increased, partly, he thinks, because of digital. Even marginal product gets a bit more attention when people find the image appealing. Duke says that Skyfall played so long and robustly partly because it was a strong movie, but also because the presentation was compelling. Thanks to his subwoofer, viewers could feel onscreen shotgun blasts in their backsides. Immersion goes only so far, however. Duke remains leery of 3D: “People are tired of paying the extra charge, and with the economy in my area I’ll still wait.”

Contrary to trends elsewhere, the Sky-Vu has benefited strongly from digital display. Duke’s was the first North American drive-in to sign up for the NEC digital system. People comment on how the bright, sharp image has improved their experience. The drive-in had “a tremendous summer,” with the first Saturday night of Brave, coupled with Avengers, proving to be the best night of the year. Measured by both box office returns and number of admissions, that show did better than Transformers the summer before. Last fall, when the Sky-Vu was the only area drive-in still open, some patrons traveled 2 1/2 hours from Illinois. The only problem with digital under the stars was that Duke couldn’t get a satisfactory VPF deal for an outdoor cinema because he doesn’t run it year-round.

While Duke runs the Goetz theatres as a family business, the JEM Theatre in Harmony, Minnesota is more of a sideline for its owner-operator Michelle Haugerud. A single screen running only at 7:30 on weekend nights, the JEM plays a unifying role in the life of the town. But it’s a small market. Harmony consists of only 1020 people (many of them Amish), and the median household income is about $30,000. Michelle had to finance the conversion through donations and bank assistance. The task was complicated by the unexpected death of her husband Paul, who ran the JEM with her.

Michelle reports that the digital conversion hasn’t increased business. Box office was about the same in 2012 as in 2011, and so far this year ticket sales have been down. It has been a slow winter and spring throughout the industry, and people are hoping the summer blockbusters will lift revenues. But the JEM faces particular problems that the Goetz doesn’t.

Michelle wants to show films in first run, as Duke does. But the distributors typically demand that she play a new movie for three weeks. That’s not feasible in her small town, so Michelle winds up missing out on films she knows would draw well. In addition, she’d be willing to screen two shows a day, the first a kid movie and the second an adult picture, but the companies don’t allow this double-billing. Moreover, she thinks that the shrinking windows–the speed with which films come out on Pay Per View, VOD, and DVD–are eroding her audience. “Many people are willing to wait for these releases since they now realize they will be out shortly after they hit the theatres anyway.”

Michelle and her family run the JEM as much for the community as for themselves. She is hoping for better times.

Converting to digital has made showing movies easier, and I have had no issues with the new equipment. However, it has not helped with ticket sales at all. I am holding on and committed to this year, but if I get to the point where it is costing me personally to stay open, I don’t think I will continue. I love having the movie theatre and would love to keep it going. I do feel if I had a say on what movies I showed and when, I would do so much better.

Kickstarting the arthouse

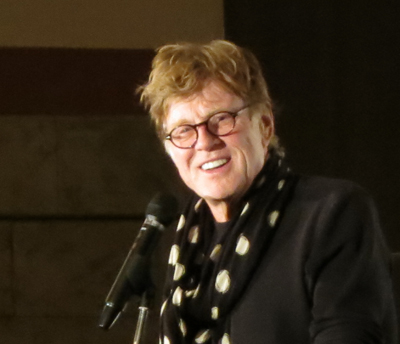

Robert Redford addresses the Art House Convergence, January 2013.

Several managers and programmers of arthouse cinemas around the country have formed an informal association, the Art House Convergence. It meets once a year just before the Sundance Film Festival, which many members attend. When I visited the conference in 2012, the digital transition was the central topic. It aroused curiosity, bewilderment, frustration, and some annoyance. This year, things were different.

Participants were calmly reconciled to the inevitable, and some looked forward to it. On one of the few panels that took up the subject, moderator Jan Klingelhofer of Pacific Film Resources began by asking: “How many of you are still on the fence about digital?” Just one hand was raised.

On the panel, technology experts from major companies showed how new projection systems could be installed even in offbeat venues. The New Parkway in Oakland was once a garage, and the Mary D. Fisher Theatre in Sedona is a converted bank. Panelists also gave information on choices of technology, from lamps and servers to the best screen materials for 3D. The teeth-gnashing is over, and now art-house leaders are focusing on practicalities: the best strategies suited for their business models.

A private, for-profit art house faces many of the problems faced by Duke Goetz and Michelle Haugerud, except that the art-house is screening films of narrower appeal. Because the audience is smaller and more select, many art houses have become not-for-profit entities created by community cultural organizations. They are dependent on donations, private or public patronage, and miscellaneous income from many activities, not only screenings but filmmaking classes, special events, and other activities. A good example of the diversity of outreach an arthouse can have is the Bryn Mawr Film Institute, whose director, the estimable Juliet Goodfriend, also coordinates the annual AHC survey. So the coordinators of the not-for-profit theatre must persuade boards of directors and generous patrons that the digital upgrade is necessary.

Small venues, whether private or not-for-profit, can’t benefit much from economies of scale. A multiplex can amortize its costs across many screens, but a big proportion of art houses boasts only one or two. Add to this the fact that multiplexes are encroaching on the art-house turf with crossover films like Moonrise Kingdom and upscale entertainment like opera and plays from Fathom. Even museums are starting to install digital equipment and play arts-related programming.

The chief task, of course, is paying for the upgrade. Last year’s AHC session was often about the money. Small local cinemas like the Goetz could benefit from VPF deals, but for many art houses such deals weren’t a good option. These houses don’t run enough films from the Majors to repay the subsidy. While they’re often eager to take something from Fox Searchlight, Focus Features, and the Weinstein company, they book a lot from IFC, Magnolia, and other independent distributors.

A common solution was to launch fundraising campaigns from the community, much as Michelle did in Harmony. One of the biggest initiatives was that conducted by the boundlessly energetic John Toner and Chris Collier of Renew Theaters in Pennsylvania. Without going for a VPF, they raised $367,000 to pay for converting three screens (one in 3D). John and Chris are vigorous advocates for the new format, and their “This Is Digital Cinema” series treats restorations of classics like Gilda and The Ten Commandments as showcases for the DCP. At AHC 2013, John and Chris provided an entertaining PowerPoint presentation on how they managed the switchover; for a prose version, you can read John’s account here.

Likewise, the Tampa Theatre raised $89,000 from its community. But what if your community can’t sustain such a big campaign? I hadn’t predicted in Pandora how powerful Kickstarter would be in the film domain, and the results are initially encouraging. Donations to the Cable Car Cinema and Cafe of Providence surpassed the goal by six thousand dollars, and the theatre is already preparing for the new equipment. The final 35mm program will be, what else?, The Last Picture Show, complete with pulled-pork sandwiches. The Crescent Theatre of Mobile won nine thousand more than it asked for, and Martin McCaffrey, venerable moving spirit of Montgomery’s Capri Theatre, followed suit and came out ahead by about the same amount.

Currently the Kickstarter site lists dozens of conversion projects, and many have met their goals–with Boston’s Brattle and LA’s Cinefamily hitting over a hundred thousand dollars. The pitches are pretty creative (“The Cinefamily is a non-profit movie theater with awesome programming, but crappy everything else”) and so are the giveaways (the Skyline drive-in of Everett, Washington offers a vintage speaker box that’s “clean and suitable for presentation”).

So maybe predictions were too pessimistic. Will we lose so many theatres to the switchover? Maybe not. But raising money for the initial conversion isn’t the whole story.

Technology: Running in place to keep up?

In the shift to digital projection, some would say the pivotal moment came with the success of Avatar and other 2009 3D releases (Monsters vs. Aliens, Ice Age: Dawn of the Dinosaurs, and Up). In 2009 there were about 7400 digital screens; a year later there were nearly 15,000. Then the acceleration began. Ten thousand screens converted in 2011 and eight thousand more the following year.

But I see 2005 as another major marker. In 2004, there were only 80 digital screens in the US. By the end of 2005, there were over 1500. The early adopters were pushed by the emergence of 3D, heavily touted by several major directors at NATO’s annual convention and the strong 3D releases of The Polar Express (2004) and Chicken Little (2005). So there were two bursts of digital adoption, both driven by 3D.

With 3D as a Trojan horse, digital entered exhibition. The format eventually settled on was the Digital Cinema Package, an ensemble of files gathered on a hard drive. The movie, with subtitles and alternate soundtracks, is wrapped in a thick swath of security files. The studios, petrified of piracy, had delayed the completion of digital cinema for some years until an ironclad system was protecting the movie. The DCP can be opened only with a customized key, delivered to the theatre separately from the hard drive. Typically the key is sent on a flash drive, so that the staff member need not retype the tediously long string of alphanumeric characters that make it up. Copying that key into the theatre’s server, its theatre management system, or the projector’s media block allows the film to be played on a certified projector.

A digital projector suitable for multiplex use relies on one of two available technologies. Sony’s proprietary system works only on its own projectors. Texas Instruments’ Digital Light Processing (DLP) technology was licensed to three manufacturers: Christie, Barco, and NEC. By fall 2010, all four companies had produced high-level, and quite expensive, machines capable of producing 4K displays. The rush to convert led to thousands of units being bought over a few months. This was great for business in the short term, but how could the manufacturers count on selling the product in the years and decades ahead? Michael Karagosian sketches the problem: “The big challenge today for technology companies is the massive downturn in sales that is destined to take place the last half of this decade as the digital installation boom ends.”

One way to expand the market was offered by cheaper machines. In fall of 2012, all the manufacturers introduced DCI-compliant projectors suitable for screens around thirty feet wide. The machines were still quite expensive, but they were marginally more affordable for the smaller or independent exhibitors who had been reluctant to convert or who had missed the deadlines for VPF financing. To maintain a quality difference from high-end machines, the cheaper versions typically lacked some features. They might be capable of only 2K, or they might not permit a wide range of frame rates, or they offered less brilliant illumination.

Another answer to a saturated market was continuous research and development. No sooner had exhibitors installed the “Series 2” projectors introduced in late 2009-early 2010 than speculation began about enhancements. How soon, for instance, might we expect 6K or even 8K resolution? Two other innovations were responding to problems with the dimness of digital 3D images.

One possibility was laser projection, which would be expected to brighten the image considerably. Laser projectors may start appearing in Imax cinemas later this year, but for most venues the current costs are prohibitive, running about half a million dollars per installation.

3D light levels could also be boosted by shooting and showing at higher frame rates than the standard 24. Peter Jackson famously experimented with 48-frame production on The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey, and some theatres screened it that way. Response was mostly skeptical, with critics complaining of the hypersharp, “soap-opera” effect onscreen. The frame-rate issue has mostly quieted down, but it did trigger academic studies of the perceptual psychology involved in frame rates. In addition, James Cameron has insisted that his sequels to Avatar will be shot at an even higher frame rate. Most projectors require new software in order to increase frame rates.

Alongside developments in the projection market have come new devices for sound. As Jeff Smith pointed out in an earlier entry, innovative sound systems have been enabled by the switchover to digital presentation. 35mm film stock constrained the amount of physical space on the film strip that auditory information could occupy. Now that sound is a matter of digital files, sound designers can add many tracks for greater immersive effects—so-called “3D audio” platforms. Barco’s Auro 11.1 system and Dolby Atmos position several more speakers around the auditorium, including ones high above the audience. Costs of installation for these systems run from $40,000 to $90,000.

Still, projector and sound-system manufacturers can assume that business will continue because of the pressures for change inherent in digital technology. Experienced equipment installers suggest that a digital projector’s life is between five and ten years. Already the Series 1 projectors introduced in 2005 are becoming obsolete. Chapin Cutler, of Boston Light & Sound, notes:

A digital projector is a computer that puts out light. How many computers will you go through in the next ten years?

How many Series 1 projectors are still in use and supported by the manufacturers? Try buying parts for them. I know of one that was purchased four years ago that has been pushed into a corner. It has sat there for about two months so far, with no end in sight. (Thank heavens they still have their 35 mm gear!) It is broken and the manufacturer cannot supply parts; their customer service department doesn’t know about the machines, as they have only had to deal with the newer models; and the parts are not listed in their own internal parts book. Yes, four years old.

When replacement parts are available, they can be exceptionally pricey. A projector’s light engine, central to the image display, can run $22,000. And if an exhibitor buys a brand-new projector some years from now, the studios aren’t likely to launch a new round of VPF financing.

So even if a theatre can afford the expense of conversion today, upgrades and maintenance will demand big commitments of money in the years ahead. John Vanco, Senior VP and manager of New York City’s IFC Center, has put it well:

Many, many small, independent theatres, which are vital to the survival of non-studio films, will end up being fatally hobbled by the transition. They may be able to raise funds to cover the initial conversion, but what will crush many of them in the long term is the ongoing capital resources that will be necessary to continue to have DCI-compliant equipment in the next ten and twenty years. . . .

In the same way the current inexorable pattern of planned obsolescence forces consumers to continually repurchase computers, phones, etc., cinemas too are going to find that they have to spend much more for cinema equipment over the next twenty years than they did, say, from 1980 to 2000. . . . So these technological progressions will make it harder for those small theatres to survive.

Dylan Skolnick of Huntington, New York’s Cinema Arts Centre adds to Vanco’s point. “We have great supporters, but I can’t go back to them every five-to-ten years with a ‘Digital Upgrade or Die’ campaign.”

The problem is acute for small and art-house venues, but it isn’t minor for the Big Three either. Unless film attendance jumps spectacularly (it has been more or less flat for several years), exhibitors may need to raise ticket prices and the costs of concessions. This strategy may work in urban areas but won’t be popular elsewhere. Moreover, part of the boom in box-office revenues during recent years has been due to the upcharge for 3D features. But in the US, 3D revenues are currently leveling off at about $1.8 billion, a drop from the format’s 2010 peak of $2.14 billion. In 2012, 3D’s market share slipped as well. It isn’t clear that people would flock to 3D if the images were brighter. And if 3D television takes off, stereoscopic cinema will seem less compelling as a novelty.

Some observers hold out hope for glasses-free 3D technology in theatres, a change that would probably boost business. But the difficulties of creating 3D of this sort for multiplex venues are immense. The glasses-free platforms proposed by Dolby are aimed at small displays, like TVs, smartphones, and tablets. Of course, if 3D without glasses were devised for big screens, it would almost certainly demand yet another projector redesign.

No more silver bricks

When it comes to distribution, digital isn’t there yet. The UPS and Fed Ex corps still bring movies to multiplexes the old-fashioned way. The little briefcases are a lot lighter than hulking metal shipping cases, but we’re still dealing with physical artifacts.

At least for the moment. Festival submissions are already being placed in Cloud-based lockers like Withoutabox in an effort to replace DVD screeners. Online delivery is already being used for many of those operas, ballets, and other forms of “alternative content” flowing onto screens from various suppliers. A Norwegian distributor sent a 100 gigabyte local film, fully encrypted, to forty cinemas in the spring of 2012. This and experiments in other countries employ fiber-based networks, but the Digital Cinema Distribution Coalition, a joint venture among Hollywood studios and the Big Three exhibition chains, is exploring satellite systems.

So much for the impassive silver bricks in their cute pink beds on the cover of Pandora’s Digital Box. They may become as quaint as film reels and changeover cue-marks. For a time, the hard drives may survive as backup systems that will reassure exhibitors, but eventually no physical site may serve as the movie’s home. An exhibitor will download the film to the server, apply a decryption key sensitive to time, venue, and machine, and the movie will be, as they say, “ingested.”

In the Pandora book, I included chapters on other exhibition domains I haven’t revisited here. Take archives. More and more studios refuse to rent prints, will not prepare DCPs of most classic titles, and won’t let theatres screen Blu-ray discs commercially. So repertory cinemas turn to archives, seeking to rent 35mm copies that may be irreplaceable. In addition, archivists, laboring under tight budget constraints, are racing to preserve and restore their material on film, which remains the most stable support medium. At the same time, archives are expected to get involved in preparing high-quality digital versions of popular classics. Henceforth most restorations that you see will be circulated on 2K or 4K, as Metropolis, La Grande Illusion, and Les Enfants du Paradis have been in recent years.

Film festivals, as Mike King, one of our Wisconsin Film Festival programmers observes, are now file festivals. Cameron Bailey reported that of the 362 titles screened at TIFF last year, only fifty-one were on film. Last month, our annual event ran twenty-one new films on film; most were 16mm experimental items. The remaining 132 were on DCP, HDCam, Quicktime files, or DVD/Blu-ray. On the plus side, independent filmmakers are learning to encode their films in the DCI-compliant format, often without layers of security, so at least in this respect technology may not be a severe barrier to entry.

As for me, I’m still in the midst of churn. I watch movies on film, on DCP, on DVD and Blu-ray and VOD, even on laserdisc, and sometimes on my iPad. But my research will miss 16mm and 35mm. Some of the questions I like to ask can be answered only by handling film. Last weekend I sat down at a Steenbeck flatbed and counted frames in passages of Notorious and King Hu’s Dragon Inn. This sort of scrutiny is virtually impossible on DVDs and Blu-rays, which don’t preserve original film frames.

What I’ve lost as a specialist is offset by many gains. Since the arrival of Betamax and VHS, nontheatrical cinema has expanded to limits we couldn’t have imagined in the 1970s. Thanks to consumer digital formats, more people have more access to more movies of all sorts than at any point in history. Although some aspects of film-originated movies are hard to recover on digital playback, we can study cinema craft to an extent that wasn’t possible before. Digitization has allowed sophisticated visual and sonic analysis to bloom on websites around the world. See, among many examples, Jim Emerson’s Scanners and A. D. Jameson’s work on Big Other.

With the rise of nontheatrical consumption, though, what’s most at risk is theatrical cinema: film viewing as a public forum. Exhibition outside film festivals is already starting to narrow to recent releases and a few approved classics. We will be able to watch The Suspended Step of the Stork and Leviathan on our home screens for a long time to come, but very seldom on the scale that benefits them most.

As ever, the problem of technology isn’t only a matter of hardware. Technology develops within institutions. Hollywood has standardized a new technology favoring its goals. The institutions of minority film culture–festivals, art houses, archives, local cinemas, schools–need to be robust and resourceful to maintain all the types of cinema we have known, and the types we might yet discover.

Since Pandora was published, a very comprehensive guide to the mechanics of digital projection has appeared: Torkell Saætervadet’s FIAF Digital Projection Guide, and it’s a must. One rich treatise I didn’t cite in Pandora is Hans Keining’s 2008 report 4K+ Systems: Theory Basics for Motion Picture Imaging. Michael Karagosian’s website is an excellent general source on digital exhibition in the late 2000s.

Screen Daily provides a good overview of the new technology on display at CinemaCon 2013. For general background on industry trends after the changeover, see the Variety article “Filmmakers Lament Extinction of Film Prints.” As for archives, Nicola Mazzanti edited a very useful European Commission study, Challenges of the Digital Era for Film Heritage Institutions (Berlin/ UK, 2012). May Haduong surveys current problems of print access and film archives in “Out of Print: The Changing Landscape of Print Accessibility for Repertory Programming,” The Moving Image (Fall 2012), 148-161. The piece requires online library access, but a summary is here.

Much of the industry information in this entry came from proprietary reports published in IHS Screen Digest. Thanks to David Hancock for his assistance with other data, and to Patrick Corcoran of NATO for updated information on theatre conversion. Thanks as well to Chapin Cutler, Duke Goetz, Michelle Haugerud, and Dylan Skolnick for permission to quote them. I’m also grateful to Jack Foley of Focus Features and Joshua Hittesdorf of Market Square Cinemas. Finally, I want to thank Russ Collins and his colleagues at the Art House Convergence for mounting another splendid event and for inviting me back last January. I continue to learn from the discussions on the AHC listserv, and I’m particularly grateful to John Toner for his reports on independent cinemas’ funding efforts.

Other entries on this site offer material on the digital transition. There’s “It’s good to be the King of the World,” on James Cameron’s push for 3D TV; “ADD = Analog, digital, dreaming,” about the powers of photochemical cinema on display at the Toronto International Film Festival 2012; “Digital projection, there and here,” some notes on the situation in Western Europe; and “Side by side: Quick catchups,” includes notes on sources for studying digital cinema. In “16, still super,” veteran programmers talk about how they continue to rely on this format; in the process they convey their commitment to providing unusual fare.

P. S. 15 May 2013: Rebecca Hall of the extraordinary Northwest Chicago Film Society has posted a continually updated list of theatres that are dedicated to showing films in 16mm and 35mm.

P.P.S. 12 June: David Hancock has just presented a very full report entitled “Digital Cinema Worldwide: 35mm phased out in many countries, though some lag behind.” It is published in the June IHS Screen Digest. One of my remarks above has been corrected in light of some information in the report: I claimed that Belgium has fully converted, but David’s figures indicate 96.5% conversion.

David predicts that by end 2013, 90 % of world screens will be digital. Even India is making the move, as circuits relying on DVD or other low-resolution sources are converting to DCI-compatible equipment. Those regions slowest to convert include Italy, Greece, and Spain (not surprisingly, given recent austerity policies), as well as areas of South America and the Pacific (e.g., Thailand, the Philippines). Thanks to David and his team at IHS Screen Digest for their comprehensive coverage of this process.

Dragon Inn (King Hu, 1967). 35mm frame enlargement, taken on Fujichrome 64.

Scoping things out: A new video lecture

A Star Is Born (1954).

DB here:

Cripes! It’s video-lecture fever!

Well, maybe that’s an exaggeration. Still, we do have something new for you.

A video analysis of constructive editing showed up last fall, and a rather long one called “How Motion Pictures Became the Movies” was posted earlier this year. Now comes one on the aesthetics of early CinemaScope in the US.

It’s a new version of a talk now retired from the lecture circuit and snugly cached on the web. I’m hoping both viewers and filmmakers will be interested in this, particularly in its analyses of staging and composition. The piece makes a more general argument about how new technologies offer both advantages and constraints.

“CinemaScope: The Modern Miracle You See without Glasses!” runs about fifty minutes. It’s our first one in HD, so it looks pretty nice on many displays. It could be shown in classes, and I’d be happy if teachers wanted to use it. As with our earlier entries, it’s also available on Vimeo here, where you can leave feedback if you want.

I’m also providing the chapter on Scope from Poetics of Cinema. Think of the lecture as the DVD and the chapter as the accompanying booklet. You can go to the essay if you want to dig deeper into the subject, see other examples of what I’m talking about, or learn the sources for my arguments.

By the way, if you’re interested in the art and craft of widescreen cinema, I’ve posted a web essay on Hong Kong anamorphic here.

As usual, I’m very grateful to my creative tech wranglers Erik Gunneson, who produced the video, and Peter Sengstock. Thanks as well to our web tsarina Meg Hamel.

I’ll have to suspend production of these video lectures for a while, but Kristin and I are hoping to float another novelty soon, perhaps in the next couple of months.

Thanks for everyone who has supported our work through Tweeting, Facebooking, linking, or just telling their friends.

Wild River (1960). From 35mm frame.

All play and no work? ROOM 237

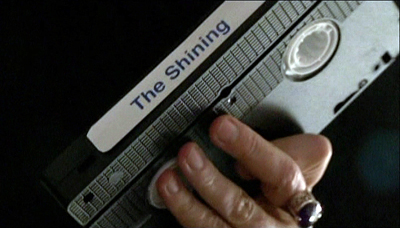

Room 237 (2012).

DB here:

Rodney Ascher’s Room 237 gathers the thoughts of five people concerning the deeper, or wider, or just awesomer meanings evoked by Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining. Those thoughts will strike many viewers as fairly far out there. Me, not so much.

Over the top

Room 237 adroitly blends several documentary genres. It recalls Cinemania and Ringers in its investigation of fan cultures. But instead of focusing on the personalities and lifestyles of the fans, Ascher concentrates on their readings of the movie. We never see the commentators. In this respect, it evokes the newly emerged genre of video essays as practiced by Kevin B. Lee and Matt Zoller Seitz. Yet it doesn’t offer itself as an earnest contribution to the critical conversation because Ascher freely intercuts stills and shots from other films, often to ironic effect.

In all, his film has the quizzical, gonzo flavor of an Errol Morris movie, minus the talking heads. But Morris is as interested in people as he is in their ideas. Ascher is interested in the ideas, and the way they swarm over and burrow into a film we thought we knew.

So he performs the sort of surgery more appropriate to the Zapruder footage. In the boldest test of cinematic Fair Use I’ve ever seen, a great many clips from the Warner Bros. release are run, slowed, halted, backed up, blown up, and overwritten as support for the interviewees’ claims. Ascher never tries to counter their arguments; at times he supplements them with extra evidence.

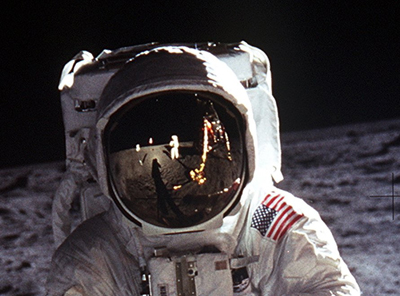

The results seem, to many, at best far-fetched and at worst (or best, from an entertainment standpoint), wacko. One of Ascher’s interviewees believes that The Shining is a denunciation of the genocidal destruction of Native Americans. Another takes the film as an exploration of the Theseus myth. Another believes that the film makes references to the Holocaust. Another finds a welter of subliminal imagery pointing to “a dark sexual fantasy.” Another sees the film as Kubrick’s apologia for staging the faked footage of the Apollo 11 moon landing.

Are these interpretations silly? Having spent forty-some years teaching film in a university, I found much of them pretty familiar. Some of the specifics were startling, but I’ve encountered interpretations in student papers, scholarly journals, and conference panels that had a lot of similarities.

If you think that this just proves that all film interpretation is ridiculous, you can stop reading now.

Because most film enthusiasts think that at least some movies need interpreting. We assume that like artists in other media, some writers and directors are using their medium to transmit or suggest meanings. And if a movie doesn’t express its makers’ ideas, perhaps it can still bear the traces of ideas out there in the culture. This “reflectionist” idea, tremendously popular among both journalists and academics, allows us to interpret even escapist fare.

Our interpretive itch has been around for a long time. Centuries of commentary have accrued around the Bible, the Torah, the Koran, and other texts deemed sacred. Secular texts, from Homeric epics to last month’s bestseller, have been scoured for hidden meanings too. The search hasn’t just been confined to literature, of course. An entire school of art history, called iconology, has devoted itself to deciphering objects, compositions, and other features of paintings. Even musical pieces without verbal texts have been “read.”

If at least some movies need interpreting, The Shining would seem to be a prime candidate. The film creates many questions about the reality of what we see and hear, and it seems to point toward regions larger than its central tale of terror. The director was one of the most ambitious filmmakers of the twentieth century, a film artist who could use a genre-based project like the famously puzzling 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) to convey ideas about the place of human history in the cosmos. Why couldn’t he do the same thing with a Stephen King horror novel?

What’s wrong, then, with the five critics’ readings? Why do many viewers find them strained and forced, even loopy? One of the many virtues of Room 237 is that it forces us to ask: What do we do when we interpret movies? What makes one film interpretation plausible and another not? Who gets to say? What historical factors lead ordinary viewers to launch this sort of scrutiny?

All in the family

We all grant that movies have conventions. In an action picture, the bad guys have extraordinarily bad aim, except when it comes to winging the hero or plugging his best friend. Similarly, film criticism relies on a batch of conventions about what things to look for and how they should be talked about. No quickie film review, for instance, is complete without discussing acting.

Interpretation, a central activity of film criticism, has its conventions as well, and the Room 237 interviewees make some moves that are common to interpretation in academe and elsewhere. For one thing, they assume that The Shining is more than a standard-issue horror movie. Most cinephile and academic critics would agree that we have to go beyond this movie’s literal level.

Some of the Room 237ers’ conclusions echo critically respectable interpretations already out there. One idea held by other critics is that the film is to some degree a parody or critique of horror conventions. Another is the conviction that the film says something about the repression of the Native American population. The Overlook Hotel is built on tribal burial grounds, a history that hints an earlier, oppressed America returning to avenge a great wrong.

Other Room 237 interpretations don’t show up in the mainstream critical literature, but they aren’t unknown in wider traditions of interpretation. Take numerology. Some interpreters of Biblical scripture find multiples of seven to be of divine significance, and so does the Holocaust advocate in Ascher’s film. According to him, the novel Lolita, which Kubrick adapted, makes 42 a symbol of fate. In The Shining, it becomes a symbol of “danger and malevolence and disaster.” Why? Multiply 2 x 3 x7 and you get 42. Danny wears a jersey with the number 42, there are at one point 42 vehicles in the hotel parking lot, and 1942 is the year in which Hitler launched the Final Solution.

Similarly, anagrams aren’t unknown in some interpretive traditions. Scholars have claimed to find in Shakespeare’s plays encoded references to the real author (Marlowe or Francis Bacon or the Earl of Oxford). Ferdinand de Saussure, one of the founders of modern linguistics, whiled away his later years with detecting anagrams in Latin poetry. Joining up with this method, the interviewee who sees The Shining as an apology for faking the Apollo landing rearranges the letters on the room key to spell out MOON ROOM. And the moon, says the critic, is 237,000 miles from our earth.

I grant you that such cabalistic maneuvers aren’t common in film criticism. But plenty of others on display in Room 237 use the same reasoning routines that we find in consensus critical writing.

What do I mean by reasoning routines? When we interpret a movie, we’re making inferences based on discrete cues we detect in the film. What cues we pick out and what inferences we draw vary a lot, but the process of inference making tends to follow certain conventions.

Consider the claim that Kubrick is warning that we shouldn’t expect a conventional horror film. A more mainstream critic would point to the flamboyant performance of Jack Nicholson, at once grotesque, comic, and ominous. This would seem to be a strong ensemble of cues asking us not to take the film straight, and perhaps implying that it’s a send-up, in a grim register, of its genre. But none of our 237ers mention this cue as a basis for their interpretation.

Instead, they scan the setting for disparities. The hotel’s architectural features sometimes differ from one shot to another. A chair is present in one reverse shot of Jack, but in the next reverse shot, it’s gone. The hotel geography can’t be plotted consistently. Moreover, one of Wendy’s visions during her desperate flight through the corridors at the climax invokes the clichés of ordinary shockers: dust, cobwebs, and skeletons—all the paraphernalia that the film has studiously avoided up to this point. These anomalies encourage the interpreter to see the film as parodying typical horror movies. The 237 critics are picking out cues less obvious, they would say, than Nicholson’s over-the-top acting.

Making meaning, or making up meanings?

Ascher’s interviewees don’t always go for minute cues. They focus as well on many items that conventionally invite symbolic interpretation. Mirrors signal any sort of reversal, such as Danny’s backward steps through the maze or the film’s symmetrical beginning and ending. Something open—a door, a character’s eyes—suggests knowledge and acceptance; something closed, like elevator doors, suggests repression. If a character enters a space, that space can be taken as a projection of the character’s mental state, as when Danny nears his parents’ bedroom and gets into “his parents’ headspace,” as one 237 critic puts it. Another commentator suggests that Jack’s job interview at the beginning of the film might be entirely his hallucination, a question raised by academic critics as well. Such speculations on the border between the subjective and objective are commonplace in discussions of horror, fantasy, and that in-between register known as the fantastic.

Puns are another time-tested inferential move. You can find a cue in the mise-en-scene and then “read” it with a verbal analogy. Snow White’s Dopey on Danny’s door suggests that the boy doesn’t yet realize what’s going on; but when the dwarf disappears, Danny is no longer “dopey”. A crushed Volkswagen stands for Kubrick’s telling King that his artistic “vehicle” has obliterated the novelist’s original “vehicle.” Abstract patterns in carpeting become Rorschach tests: Are those shapes mazes? Phalluses? Wombs? NASA launching pads? Mainstream critics might not fasten on these particular cues, but many wouldn’t resist the urge to find puns. After all, even Freud interpreted a dream in which his patient got kissed in a car as exhibiting “auto-eroticism.”