Archive for the 'Screenwriting' Category

ARRIVAL: When is Now?

Arrival (2016).

DB here:

A lot of today’s movie storytelling is nonlinear. Filmmakers rely on flashbacks, replays, and voice-overs in order to shape our experience, sometimes in fairly daring ways. In Hollywood these strategies got consolidated in the 1940s. Or so I argue in my Reinventing Hollywood, now in copy-editing (or as the University of Chicago Press calls it, copy editing).

The question today is the same as back then: How do ambitious filmmakers handle these conventions? I think the ambitious writer or director faces at least three tasks.

How do I innovate—that is, how do I treat time shifts in a fresh way?

How do I motivate the shifts—that is, justify the scrambling of chronology?

How do I make the new version clear enough for audiences to follow?

Novelty, motivation, and clarity seem to me essential considerations for a filmmaker who wants to play with time and the viewpoint shifts that often come with it.

I’m not alone in thinking that Arrival succeeds in creating its particular engagement with the audience by tackling my three tasks. Director Denis Villeneuve and screenwriter Eric Heisserer innovate in handling time, and they in turn carefully motivate the device and find ways to make it clear to the audience. Today I want to consider how this all works. I have to assume you’ve seen the film, so of course there are spoilers.

Back to what future?

Cinema didn’t invent broken timelines; they’ve been used in literature for centuries. The Odyssey has blocks of flashbacks. Literature benefits from the fact that language has simple and direct ways to signal jumps in time.

For example, the writer working in English can make flashbacks clear though time tags and verb tense. Take this passage from John Le Carré’s novel Our Kind of Traitor. We’re told that on Sunday morning an anxious Perry Makepiece is climbing into a chauffeur-driven Mercedes. Then:

Last night, returning to the Deux Anges from their supper party, Perry had caught Madame Mère’s boot-button eyes peering at him from her den behind the reception desk.

“Last night” tells us we’re in an earlier period, and that information is reinforced by the past perfect tense of “had caught.” Page layout helps too: the entire flashback to the previous night is blocked out within extra spaces separated by a centered ★.

After recounting what happened when Perry returned to his hotel last night, Le Carré returns to the present time, the narrative Now, with a turn to the simple past tense:

The Mercedes stank of foul tobacco smoke.

Apart from the change of tense, the Mercedes mention reminds us of Perry’s morning trip. In addition, the shift back to the present opens a new section marked by ★.

On my three dimensions: There’s nothing innovative about this instance, though Le Carré will try some unusual things elsewhere in the book. The flashback is motivated by Perry’s remembering last night, and it’s made clear to the reader through repetition of several cues.

But what do we do with this passage?

I remember the scenario of your origin you’ll suggest when you’re twelve.

The tenses are out of whack, thanks to that “you’ll.” Then there’s the very meaning of the word “remember.” (Replacing the phrase with “I imagine.”) How can you remember something that has yet to happen? This isn’t just a casual slip. The speaker goes on to report an entire conversation that uses the future tense: “you’ll say bitterly,” “I’ll say,” “That will be in the house on Belmont Street,” and so on.

This passage comes near the start of Ted Chiang’s “Story of Your Life,” the source of Arrival. The story is what literary scholars call an apostrophe, a discourse addressed to an absent person. Louise Banks explains how her daughter came into existence. The story begins with Louise’s husband asking one evening, “”Do you want to make a baby?” It’s this point in time that’s marked as the present (and is rendered in present tense), but the bulk of the story shuttles between the past and the future. From the benchmark moment we get, in other words, flashbacks alternating with flashforwards.

On my three-dimensional scale, Chiang gets credit for innovation. Stories told in the future tense are pretty rare, especially when the events are presented as memories. And he makes the narrational premise clear. After a few pages, it’s established that Louise purports to know things yet to happen. The tenses cooperate: Present for the baby-making moment, past tense for the past events, future for the future ones.

We’re used to characters who know their past, but how can one know her future? For the story-maker that reduces to: How to motivate Louise’s knowing the future?

The answer is aliens. In the past, Louise met her husband when floating seven-legged creatures came to earth. As a linguist, she was assigned to learn the Heptapods’ language. Gradually she discovered that they had a mentality that refused causality and sequence in favor of a holistic view of time. Their language, to put it crudely, gave them access to past, present, and future.

By learning their language Louise absorbed, to some extent, their world-view. (Yes, the untenable Sapir-Whorf hypothesis is invoked.) Her precognition allows her to know, moments before she and her husband conceive the girl, what her daughter will do from her childhood right up to her early death. Louise also knows that she and her husband will divorce and find new partners. For us, these episodes are rendered as flashforwards from the Now, even though for Louise they are, paradoxically, memories (of things yet to happen).

Chiang’s story explores the emotional effects of knowing the future and deciding not to try to change it. For all I know, this may be another innovation in the realm of speculative fiction. Most time-travelers seek to alter the past or the future, but Louise is aware of the paradoxes of time travel. If you know the future, you can freely decide to alter it by choosing differently at crucial junctures. Marry somebody else, and you’ll change what happens afterward, so you didn’t really know the future. But Louise comes to believe that free will is a part of linear, causal thinking, the sort that the Heptapods have given up.

The existence of free will meant that we couldn’t know the future. And we knew free will still existed because we had direct experience of it. Volition was an intrinsic part of consciousness.

Or was it? What if the experience of knowing the future changed a person? What if it evoked a sense of urgency, a sense of obligation to act precisely as she knew she would?

The Heptapods know that they will need help from Earth in 3000 years, and they presumably know that they’ll get it, but to fulfill that future they need to ask. The story’s analogy is to the daughter’s wanting to re-hear a story she knows by heart. As a story reader replays a known tale, the aliens perform the incidents that make things inevitable.

So Louise accepts her role in playing out whatever future is predetermined. For this reason she can address her (future) daughter with foreknowledge of the pains and delights that are coming, accepting them as part of a seamless whole.

Image + sound + time

Lacking a tense system like language, cinema has devised other time signals. In the classic flashback we get a combination of them. We’re presented with a speaking or remembering character, a track-in to her, perhaps some music, a hint in the dialogue that we’re going into the past, a dissolve, perhaps a voice-over indication, and then a scene obviously situated in an earlier period. Filmmakers have discovered ways of altering some cues (cuts replace dissolves, tight close-ups replace track-ins) and deleting others (music and voice-over seem fairly optional now). Other cues are added for clarity, such as a different color palette for scenes in the past, or perhaps slow-motion imagery, or sound from the past that leaks in over imagery in the present.

Of course films use written and spoken language too, and so they can deploy tenses and time tags. Sometimes that can help us understand the time status of the scenes we’re seeing.

Voice-over is very helpful here. Take another Le Carré example, this time from Fred Schepisi and Tom Stoppard’s adaptation of The Russia House. Play the clip below and you’ll see what I mean.

Katya’s delivery of the covert manuscript, given on the image track, seems at first to be in the present. But the voice-over office conversation, only gradually shown through intercutting, is later than the Moscow incidents we see. So the present, the opening Now, is established on the soundtrack, while the image is in the past. As in fiction, the twin cues of verbal tense (“she visited”) and a time tag (“a week ago”) confirm the status of the Bookfair scene. The innovation comes when Stoppard and Schepisi don’t frame the Moscow scene by offering us the present-time office conversation before we see Katya–in effect, establishing the Now before showing us the Then. It’s an economical tactic of exposition, an elliptical revision of the phone conversations about the police investigations in M.

A voice-over can be in same time period as the images, of course, if it’s an inner monologue, a report on what a character is thinking at the moment. But voice-over commentary is often positioned as in the present with the images assumed to be in the past.

The voice-over present can be specified, usually through a lead-in scene showing the speaker recounting or recalling things at a particular time. Or the voice can be in a vague present, a zone we take as simply “after the events of the story.” It’s this no-man’s-land Now that leads us astray in Laura and other tricky films from the 1940s onward. Uncertainty about who’s speaking from when can be a source of interest in its own right. In Road Warrior, the revelation of the source of the opening voice-over provides the final surprise of the film.

So Heisserer and Villeneuve had an opportunity to follow Chiang in using the future tense in the voice-over for Arrival. It would surely have been an innovative move for a film. But they don’t do it. Why?

From premise to twist

Flashbacks are temperamental little buggers. Hard to know when and how to use them.

Eric Heisserer, 150 Screenwriting Challenges

Heisserer was a keen fan of Chiang’s story and spent years trying to get backing for a film version. He recounts various difficulties in online interviews (here and here, for example), but I want to focus on a couple of other problems he faced.

In a general way, the film respects the thrust of the story. At the close, you realize that Louise has gained the ability to anticipate the future, thanks to learning Heptapod. But on a fine-grained basis, the film doesn’t spell out her ability as frankly or as early as the story does.

The first image, a view out onto the patio and the lake, shows no people, just a table with a wine bottle and a couple of glasses. Louise’s voice-over does address someone absent: “I used to think this was the beginning of your story.” But the point in time and the person addressed are far less specific than in the literary version. Then we get a quick burst of images of a baby, then a little girl playing with Louise, and soon a young woman lying dead in a hospital bed. This cascade of impressions ends with a shot of Louise walking mournfully down a hospital corridor, followed by a fade-out. Fade up on her striding into a campus building and attending her lecture. Over this we hear her voice-over.

But now I’m not so sure I believe in beginnings and endings. There are things that define your story beyond your life. Like the day they arrived.

And then we’re confronted by the Heptapods, as broadcast on worldwide TV, and Louise’s getting the assignment to talk with them.

The first shot, of the patio, is enigmatic, but fairly soon we get the sense that Louise is addressing her dead daughter. We seem to have a classic prologue. (Compare the opening death of Starlord’s mother in Guardians of the Galaxy.) Across three minutes, we see a mother loving and losing her daughter. Our default assumption is that after the daughter’s death, she has become solitary and emotionally numb. She doesn’t interact with people on her way to her classroom, and when she goes home alone she watches TV reports with a kind of blank anxiety.

The film sets up a schema: The grieving mother needs to get out of herself, and the assignment to communicate with the aliens would seem to do that. Eventually she finds love with the physicist Ian Donnelly as well. This redemption schema is probably reinforced for some viewers by memories of Gravity (2013), another movie about a withdrawn mother who channels her sorrow into heroic action.

As the alien encounters unfold, the film’s narration starts to sprinkle in more images of the lost daughter at different ages. But the images show up rather late. At about 48 minutes, there’s a brief, out-of-focus image of a baby; at about 51:00, a glimpse of the little girl wading. Not until about halfway through the film (57:00) is there a fairly sustained scene between mother and child, when the girl shows Louise a picture of her imaginary TV show. That’s when we learn that the father isn’t with them any more. Later shots of the daughter are salted through the scenes of the increasingly tense confrontation with the Heptapods.

Just as we’re encouraged to take the daughter’s birth, childhood, and death as a prologue that precedes the alien investigation, we’re inclined to take these interruptive shots of the girl as flashbacks. Louise seems to be remembering her daughter.

At about 82 minutes something happens that challenges our basic assumption. In another household scene, the daughter asks about the “science-y” term for a win/win situation, and Louise is stumped. The narration shifts us back to the tent at the site, Ian mentions the term “non-zero-sum game.” Then we’re whisked back to the scene with the daughter, and Louise repeats that.

I felt a bump there. If the scene with Ian’s use of the term comes after the death of the daughter, during the alien encounter, how can Louise “remember” it to relay it to the daughter? For many viewers (probably not all), this opens the possibility that the “prologue” tracing the daughter’s childhood takes place after the alien adventure, not before. The reinforcement for this, visible to me only on second viewing, is that the earlier glimpses of the girl’s growing up are always triggered by scenes showing Louise learning the Heptapod’s language.

The filmic narration creates a sort of duck/rabbit Gestalt switch. Things we thought were past are future, things we thought were present are past. If the patio shot is the benchmark Now, the growth and death of the girl are the future and the Heptapods’ visit becomes a sustained flashback.

Now we see why Louise’s introductory voice-over lacks the future-tense sentences that are so startling in the novella. Including those would have been too strong a hint about the status of the mother-daughter shots. Instead, the opening voice-over uses only the past tense (“I used to think”) and the present (“But now I’m not so sure”). Another moment in the voice-over tilts us toward thinking of the image bursts later as flashbacks: we hear Louise murmur over the dead girl. “Come back to me.” Her yearning to reconnect to her daughter inclines us even more to consider the visions of the girl later as flashbacks.

Redundancy is your friend

Okay, pretty innovative—and an interesting departure from Chiang’s story. Instead of telling us at the outset that Louise has precognition, the film holds that as a surprise, and makes us think that her anticipations are actually memories. And we have motivation: as in the story, it’s the alien encounter that endows Louise with precognition. But what about my third consideration, clarity?

I said that not everybody will probably catch the echo of Ian’s “non-zero-sum game.” The last half-hour of the film devotes itself partly to reiterating the news that Louise can discern the future.

Her impulsive visit to the Heptapods late in the film explains why they dropped by. They know they’ll need humans’ help in the future, so they come to make that future happen. At the ninety-minute mark, one speaks, and we get a big old subtitle: “Louise sees future.” If you doubt the Heptapod’s insight, another flashforward soon shows Louise explaining to her daughter why her dad left. Louise “made a mistake” by telling him about a rare disease—presumably the one that would kill their daughter. We’re left to understand that after she told him that she knew their child was fated to die young, he couldn’t take it. The delayed exposition, judiciously repeated, lets the pieces fall into place. We may even start to surmise that Ian is to be that husband, earlier identified as a scientist.

Like the aliens’ sentences, the film is circular. Heisserer told Vox:

When I completed the first draft and the bookends of the first three pages and the final three pages, it felt like I was drawing a narrative circle and I just closed the loop. That felt right.

The narration buckles the film shut by returning to the view of the patio, which is intercut with Louise and Ian embracing. Ian proposes that tonight they make a baby. The fact that Heisserer’s script displaces to the very end what was the opening of Chiang’s story is a fair index of the transformation he has wrought. What was a premise of the novella becomes a reveal in the film.

But the motivation is the same. Flashforwards aren’t exactly parallel to flashbacks, as far as viewer psychology is concerned. Flashbacks are assumed to be veridical unless there’s reason to doubt them (as in trial and investigation films, where people give differing versions of events). The default is that flashbacks really happened, unless there are contrary indications.

Flashforwards, on the other hand, can be of two types. They might proceed from the film’s external narration. In Easy Rider, Petulia, and They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? we get glimpses of future events that no character can know. In such cases, the images are usually enigmatic enough that we can’t be sure about the import of what we’re seeing. Flaming motorcycles, the protagonist tossing a bouquet into the water, a brief cutaway to a man in a police wagon (below, from They Shoot Horses): these are teases, not fully informative scenes, and they interrupt the main present-time action.

Alternatively, more identifiable flashforwards are usually motivated as a character’s precognition. They aren’t necessarily reliable. Flashbacks normally represent “actual” pasts, but flashforwards coming from mediums, psychics, or possessed children are only possible futures. Indeed, one task in such films is to prevent the apparent future from coming to pass, as in Minority Report and It Happened Tomorrow. The past is closed, but in subjective flashforwards, the future is usually open.

How, then, do we motivate trustworthy flashforwards? Here. by having infallible aliens certify them. Like “Story of Your Life,” Arrival assures us that Louise’s premonitions are accurate. It’s just that Chiang’s story proposes that early on and then shows how she achieved them. The film is trickier. It misleads us into thinking she has memories of the past when she is actually learning to see the future. She learns more quickly than we do, though eventually we catch up with her.

We’ve also learned that flashforwards can masquerade as flashbacks—if they’re deployed carefully enough.

Adding the ride

Explaining, very clearly, that Louise is knowing her future is only one task of the last stretch of the film. Another task is preventing a military attack on the aliens.

In Chiang’s story, the creatures simply leave. But Heisserer has explained that he felt the plot needed more conflict, so he added the prospect of brass hats eager to confront the visitors. The Heptapods, Louise suggests, have landed at various places around the world to induce nations to forget their differences in a common purpose. The Americans are suspicious, and General Shang of China breaks away from the alliance and takes steps to attack the ship near Shanghai.

Of the civil turmoil and military threat that fill out the plot, Heisserer noted in the same Vox interview:

The story doesn’t really have any conflict of that nature. It doesn’t need to. It’s a lovely literary conceit in its own right and works without that drama.

However, our early attempts a building this narrative without that conflict added felt very flat, and felt like there were no stakes. There was no ride. The more we played with it, the more Denis and I both realized that if aliens did land on earth and the public didn’t get immediate answers as to what their purpose was, the more everybody would freak out.

In building this climax, the film varies crucially from Chiang’s premise. Now Louise seems to alter the future. She apparently summons the will to induce General Shang, at a future celebration of the successful mission, to give her his private cellphone number and tell her his wife’s dying words. Back in the past, Louise uses this new knowledge to induce the General to hold his fire. All this is presented in a classical ticking-clock drama of suspense and pursuit.

The device is a bit awkward; instead of visiting an actual future, Louise seems present at one where the General, against all plausibility, tells her things she supposedly already knows. And how she induces him to spill all this is unclear, at least to me. The climax also breaks with the original story’s idea that Louise doesn’t exercise free will but accepts her role in the course of time.

More often than one might expect, classically constructed films break some of their self-imposed rules in the rush to a climax. Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956) is one of my favorite examples, in which the climax violates the story’s method of pod-cloning. Sometimes an exciting denouement or a shocking twist tends to make us forget not only plausibility but also the premises that have operated over the previous ninety minutes.

An unsympathetic critic could object to the injection of a chase, a deadline, and a last-minute salvation of the mission, as well as the one-world moral of the movie. But to enjoy Hollywood, as with enjoying friends and other aspects of life, you have to accept, and even come to enjoy, the flaws too. The center of the film remains our transmutation of sympathy for a grieving mother into sympathy for a woman who knows she will be grieving for a child yet unborn, and yet embraces her destiny. The formal strategies serve to vividly convey this reversal of feeling, in the process ennobling a character reconciled to the transient joys of life.

Kenneth Burke once characterized literary form as “the psychology of the audience.” Filmmakers, like all artists, have recognized this from almost the beginning, but it may seem that today’s creative community is more self-conscious than ever before. If “form is the new content,” as I’ve suggested before, it’s a welcome development. Filmmakers are exploring lots of possibilities for engaging our minds and emotions, while still striving to keep their stories understandable to a large audience. Arrival could not have been made in my sacred 1940s, but its deft innovations build upon a foundation that was laid then.

Thanks to conversations with Jeff Smith and Kristin about Arrival. Thanks also to Merijoy Endrizzi-Ray and Jacob Rust at Madison’s Sundance Theater.

Jeff Goldsmith has an enlightening interview with Eric Hisserer at Screencraft. Ted Chiang’s novella is in the collection Stories of Your Life and Others. Burke’s discussion is in the essay, “Psychology and Form.”

The first quarter of Le Carré’s Our Kind of Traitor consists of an “intercut” sequence between past events and present interrogation that, in its free use of tenses, time tags, and other devices, seems to aim at a literary equivalent of the Russia House film opening. A pity that the recent film of Our Kind of Traitor didn’t try for a cinematic equivalent.

For more on modern treatments of narration and plot structure, try here. For further discussions of 1940s treatments of time-juggling, here are some blog entries.

P.S. 3 December 2016: The original entry didn’t use Minority Report or It Happened Tomorrow as examples of averting the future. They’re corrections to my original mention of Don’t Look Now, which was not an accurate example. David Cairns wrote to remind me of that, and to point out that the glimpse of the future we get in that film is in an interesting way akin to what we get in Arrival, and I hadn’t noticed that. For those who haven’t seen Don’t Look Now, I won’t add to an already spoiler-heavy entry. I’ll simply thank David, whose exemplary blogsite Shadowplay (currently hosting a blogathon under the rubric of The Late Show) is a must for every film lover. His new film, The Northleach Horror, is nearing completion; details here.

Arrival (2016).

Rethinking the character arc: A guest post by Rory Kelly

The Apartment (1960).

DB here:

Rory Kelly, whom I met some years ago at a conference of the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image, has been a pioneer in linking the practices of film production to larger issues of narrative, performance, and artistic form. What follows is a version of a superb paper he gave at the Society’s annual meeting in Ithaca in June. Since Kristin and I are always eager to know how practitioners think of their craft, we jumped at the chance to pass along his thoughts in one of our guest blog entries.

Rory comes fully prepared to the task. Currently an Assistant Professor in the Production/Directing Program at UCLA, he has been a bright light in filmmaking for many years. His first feature, Sleep with Me (1994) premiered as an Official Selection at Cannes and was released by MGM/UA. His second feature, Some Girl (1998), garnered him the DGA-sponsored Best Director Award at the Los Angeles Film Festival, and his 2006 short, The Women, premiered at the Long Island Film Festival. He was also co-executive producer of mtvU’s Sucks Less with Kevin Smith. Rory has been a Film Independent Screenwriting Fellow and is currently working on several research projects, including studies of discourse analysis and emotional expression in film. At the same time, thanks to a 2016-2017 Heillman Fellowship, he is preparing a feature documentary about racism in America, To Someday Understand.

Here’s Rory on a perennial problem of the screenwriter: the character arc.

Since the 1960s, the character arc has become all but obligatory in Hollywood movies. Genres like sci-fi and horror, once largely unconcerned with character change, now often include it. Compare, for example, the 1953 version of War of the Worlds with Steven Spielberg’s 2005 remake. In the latter the alien invaders are not only defeated, but in the process Tom Cruise’s character, Ray Ferrier, becomes a better father.

Why has character change become so prominent? In The Way Hollywood Tells It (2006), David offered some suggestions. The psychological probing in plays by Arthur Miller, Paddy Chayefsky, and Tennessee Williams became popular models of serious drama. Teachers and writers were persuaded by Lajos Egri’s book, The Art of Dramatic Writing (1946), in which the author advises that characters should grow over the course of a play. There was also the impact of self-actualization movements of the 1960s and 1970s that held out the promise of personal growth and transformation.

It’s also likely that star power has had considerable influence. When trying to raise financing for a low-budget indie script a few years back, my collaborator and I were advised by three different seasoned producers to give our protagonist a more pronounced arc or we would never be able to attract a name actress to the role. Whether they were right or not, I do not know, but their shared assumption about attracting talent is telling.

Given how common the character arc has become, we need to better understand how it is typically handled. I think we can identify and analyze six narrative strategies that create a particular character type: the protagonist who is flawed but is capable of positive psychological change. My primary example will be The Apartment (1960).

I’ll also consider aspects of character change in Casablanca (1942), Jaws (1975), and About a Boy (2002). This list will allow me to consider the character arc over six decades, from the studio era to contemporary Hollywood, and across several genres. Limited as it is, this set of films suggests that certain techniques of character change recur again and again. In tracing them, I’ll occasionally make reference to the four-part plot pattern Kristin has set out in Storytelling in the New Hollywood (1999) and several entries on this site: the Setup, the Complicating Action, the Development, and the Climax.

A six-step program

Casablanca (1942).

First, a filmmaker seeking to construct a character arc will almost inevitably begin by establishing that his or her protagonist is of (1) Two Minds. I mean by this that the character has competing impulses. Think of Rick in Casablanca. On the one hand he is inclined towards communal action; on the other hand he sticks his neck out for no one. This latter behavior is solidified during the Setup portion when he assists in Ugarte’s arrest.

It can be termed Rick’s (2) Negative Behavior Pattern. It is a pattern because it is a type of behavior Rick enacts again and again, as when he repeatedly refuses to give the letters of transit to Victor and Ilsa. The film even turns Rick’s selfishness into a motif.

Still, Rick retains an impulse towards virtuous behavior, his (3) Positive Behavior Pattern. During the Setup, for example, he does not allow a notorious Nazi to gamble in his café. Later he helps a destitute young couple earn passage to America by allowing them to win at roulette.

The film as well makes a motif of Rick’s virtuous side.

The ongoing interaction of these two behavior patterns allows the filmmakers to maintain audience sympathy for Rick, to motivate his final change of heart—if Rick were not of two minds, his final transformation would come out of nowhere—and to delay that change of heart long enough to create expectations and suspense.

What often postpones a protagonist’s change of heart is a (4) False Belief. In many films a misunderstanding is introduced that motivates the protagonist’s negative behavior pattern. Because of this the character need only discover the truth in order to be reborn. Think again of Rick. It is because he falsely believes that Ilsa once jilted him, leaving him alone in the rain at a train station in Paris, that he has become a sullen saloonkeeper who sticks his neck out for no one.

But once Rick learns the truth—that Ilsa left him because she discovered her husband was alive—Rick forgives her. He then devises a scheme to help her and Victor escape, and he makes plans to join the Resistance. The truth, in short, sets Rick free and quickly and efficiently allows for his change of heart.

Another way to look at Rick’s transformation is that his false belief about Ilsa has made him essentially a nihilist who believes that there is nothing worth living for. When Victor says, “If we stop fighting our enemies, the world will die,” Rick replies, “What of it? Then it’ll be out of its misery.” Seen from this angle, when Ilsa finally convinces Rick of the truth, we are meant to infer that his change of heart is the result of a realization that love and loyalty still exist in the world.

The final two strategies I want to discuss concern the story world. In the case of flawed protagonists the rules and values of the fictional world may be established as conflicted in a way that matches the protagonist’s competing impulses. On the one hand there is what I term the (5) Normal World. This constitutes the dominant rules and values in play as the movie begins. Against this there is what I term the (6) Possible World. This constitutes what the normal world should be.

Think once more of Casablanca. That city is established as a place where a great many people have abandoned their better impulses and are out only for themselves. The primary representative of this worldview is the charming but corrupt Captain Renault. However, the story world also includes Victor and other members of the Resistance, and they are believers in a new world; one based upon a common cause. So the story world is, like Rick, flawed but of two minds.

Rick occupies a psychological space between Renault and Victor. In the end, by siding with Victor, Rick not only abandons his negative behavior pattern, he also begins the process of overturning the rules of the normal world. The change is suggested by Renault’s becoming, as it were, Rick’s first convert. They leave together to join up with a mysterious free French garrison at Brazzaville.

Rick’s character arc is not an isolated device but a central organizing principle of the plot. The same process is at work in The Apartment.

The Apartment: A normal world?

The Apartment tells the story of an ordinary accountant, C. C. Baxter, played by Jack Lemmon. In a calculated attempt to gain a promotion, Baxter allows his bosses to use his apartment for their extramarital affairs. Baxter is also smitten with an “elevator girl,” Fran Kubelik, played by Shirley MacLaine. But unbeknownst to Baxter, at least during the first half of the film, Fran is having an affair with the big boss, Mr. Sheldrake, played by Fred McMurray. Sheldrake is only stringing Fran along, though, and because of his treatment of her she eventually attempts suicide. Baxter finds her just in time and with the help of his neighbor, Dr. Dreyfuss, saves Fran’s life.

Baxter becomes Fran’s caregiver, but also Mr. Sheldrake’s protector, ensuring that news of Fran’s suicide attempt does not leak out. In the end, however, Baxter learns the error of his ways and finally follows the advice he is given by Dr. Dreyfuss.

When Baxter does become a mensch, he succeeds in winning Fran’s heart.

The six-step strategy displayed in Casablanca is launched in the opening few minutes of The Apartment.

We learn a great deal from this opening sequence. We learn that Baxter has a problem with his apartment and we learn that Mr. Kirkeby, the boss using his apartment, doesn’t respect him. The boss’s disdain helps garner sympathy for Baxter. Yes, Baxter is ill-advisedly allowing his bosses to use his apartment, but his bosses take advantage of the situation and mistreat him.

So why does Baxter let his bosses push him around? He wants a promotion, but why must he be so obsequious to get it? Is he unworthy? No. As we see right away, he is a hard worker.

In the opening voiceover we learn that Baxter is smart, or at least good with numbers, that he is enthusiastic about his work as an accountant, and that he respects and is impressed with the company he works for. He is a diligent company man, both capable and earnest. So why is he such a pushover?

To answer that question we need to look at the normal world. The film almost immediately introduces us to Consolidated Life, the insurance company Baxter works for. It is a beehive, an impersonal and monotonous corporate colony. And Baxter is depicted as an anonymous drone: he works on the 19th floor, Section W, at desk #861.

Baxter is not just a cog in a machine; he also behaves like a machine when we see his head bob up and down in unison with his calculator. If at the end of the film Baxter becomes a mensch, a human being, then at the beginning of the film he is an automaton. He does what he is told. That is part of being a company man.

Fran, who functions as co-protagonist, works inside a machine. Her gray uniform blends into her surroundings.

Fran and Baxter are insignificant, powerless and anonymous people lost among the 8,042,783 New Yorkers. In The Apartment status, power, money and the freedom to do what you want, other people be damned, are the highest values people can aspire to. And those without status, power and money are nobodies. That is how the normal world works in The Apartment.

The only way to escape anonymity and insignificance is to climb the ladder of corporate and/or social success, and presumably become one of the exploiters. This is exactly what Baxter and Fran try to do. Baxter, after all, wants to be a big boss like the men he lets use his apartment. His gamesmanship eventually allows him to jump the promotion line. His co-worker has been at Consolidated Life twice as long as Baxter, but because he does not play the game, he is not promoted.

Fran wants a promotion too: from mistress to wife of a very powerful man. She becomes to some degree complicit with Sheldrake in disregarding the needs of his wife.

Both Baxter and Fran, then, are willing to climb over other people to get what they want. Still, they aren’t vicious. In most ways, Fran is a kind and encouraging person. When Baxter comes up for his first promotion she tells him, “It couldn’t happen to a nicer guy.” And Fran actually loves Sheldrake. Fran is not Sylvia, a woman we meet in the opening sequence, who seems mostly interested in having a good time.

Just as Fran is not like Sylvia, Baxter is not like his bosses. For one thing, he apologizes to his neighbors for all the noise his bosses make during their trysts. He even tries to correct the situation. And unlike Sheldrake and Kirkeby, Baxter does not want to simply seduce Fran.

Baxter is naïve, a romantic, a rank sentimentalist. And his chances for success in this world, like Fran’s, are limited.

In sum, Baxter and Fran are of two minds. They exhibit both a positive behavior pattern and a negative behavior pattern. This is very important. Because they both basically have good intentions—or aren’t cynical enough for the world they inhabit—they can grow as characters.

But given their good intentions, why do Fran and Baxter have negative behavior patterns? The answer is that each harbors a false belief (related to the normal world) that motivates their negative behavior pattern. Fran’s false belief is that Sheldrake loves her. And because of this she continually trusts him. Here she is going off in a cab to sleep with him, even though we know that Sheldrake hardly cares about her.

In parallel fashion, Baxter believes that corporate success will bring him happiness, but in the end it doesn’t. He gets his big fat promotion with his own office, and he’s miserable.

Still, as long as Baxter harbors the illusion that climbing the corporate ladder will make him happy, he is willing to kiss up to his bosses and allow them to push him around as a way to get ahead. That is Baxter’s negative behavior pattern: he is a toady.

The Apartment: Delay and the darkest moment

Sustaining a character’s positive and negative behavior patterns often becomes of central importance in a film’s second half, when what Kristin calls the Development is launched. In some films the protagonist actually has enough information by this point to reconsider the false belief, but that doesn’t happen. The protagonist clings to error.

The midpoint of The Apartment is the moment roughly an hour into the film when Baxter discovers Fran comatose in his bed. As Kristin points out, a midpoint typically recasts character goals, and Baxter gains a new purpose: saving Fran.

Baxter is worried that Fran will try again to kill herself, so a lot of the Development focuses on his attempts to keep her safe. But Baxter is also protecting Sheldrake during this section of the film. He induces the doctor not to report Fran’s suicide attempt to the police, and he hides Fran in his apartment until she’s better. Baxter’s competing motives, in other words, remain in play. Helping to save Fran’s life, and learning that there is a terrible cost to Sheldrake’s callous behavior should be enough to motivate Baxter to turn against Sheldrake. But he remains on the job.

We see something similar happen about twenty minutes into the Development, when Baxter phones Sheldrake to tell him about the suicide attempt. Sheldrake won’t even come to visit Fran. Baxter is confused and disappointed by this response, but he nonetheless promises his continued support.

This is a common strategy during a Development section. The flawed protagonist is one or more times brought to the brink of character change, but he or she pulls back, clinging to the negative behavior pattern. We see exactly this withdrawal in Casablanca. At the midpoint in that film Ilsa visits Rick and tries to tell him about her relationship with Victor. Rick has an opportunity here to accept the truth, which would set him free, but he rejects it. He clings to his false belief that Ilsa betrayed him and Paris.

Rick is given a second chance roughly halfway through the development when he allows the young couple to win at roulette. Rick’s employee, Karl, is watching from the sidelines, and he is thrilled. He believes that Rick is turning over a new leaf, and so do we. But immediately following this event Victor directly asks Rick for the letters of transit, and Rick bitterly says no.

These are of course delaying tactics, and ones we should expect. Kristin points out that the Development section usually contains numerous delays that create rising tension and suspense, while forestalling resolution.

In The Apartment‘s Development section, certainly Fran’s change of heart is delayed. Despite being driven to attempt suicide by Sheldrake’s treatment of her, she nonetheless announces the next day that she’s still in love with him. She even reaffirms her false belief.

Fran’s near-death experience should be enough to convince her that she needs to end her relationship with Sheldrake, but she too clings to her false belief and negative behavior pattern. Still, in spite of all this, it would be a mistake to say that no progress is being made. Baxter after all is horrified by what Fran has done to herself and Fran is beginning to entertain doubts. She says that “maybe” Sheldrake loves her. And all of this culminates in a moment of self-knowledge:

They are, in short, changing. Also, the possibility of a romantic relationship is finally introduced when Baxter and Fran prepare to sit down to a candlelit dinner together.

With these new story premises in place, the stage is set for Baxter and Fran’s final changes of heart in the climax. But not before a few more delaying tactics are deployed.

First, Fran’s brother-in-law Karl arrives and breaks up Fran and Baxter’s dinner plans. Then Baxter visits Sheldrake to tell him that he is in love with Fran and intends to marry her. But Sheldrake beats him to the punch. His wife has found out about his philandering and kicked him out of the house. Now Sheldrake plans to marry Fran. But to thank Baxter for taking care of business, Sheldrake gives him his big promotion.

As we’ve seen, corporate success is no longer what Baxter wants. In current screenwriter parlance, this is his darkest moment. It’s immediately followed by this exchange:

Fran is clearly ambivalent about her impending marriage to Sheldrake, and Baxter is clearly acting out, trying to hurt Fran. Also, Fran is deeply disturbed to see the cynical side of Baxter out in full force. And this brings me finally to the possible world. As we also saw in Casablanca, the story world in The Apartment is divided, and again the question is who will the protagonist become. Will Baxter grow up to be Dr. Dreyfuss, who represents a communal worldview, or will he grow up to be Mr. Sheldrake, who represents a selfish worldview?

Now it seems that Baxter has become Sheldrake–except we don’t, or aren’t supposed to, believe him. The real point of the exchange between Baxter and Fran is that Baxter no longer holds his false belief. He is using it now only as a defense mechanism, as a cudgel to punish the woman he sees as having betrayed him. He is, in short, pretending. And since he is no longer committed to his false belief he can change.

As has become typical in Hollywood films, the protagonist’s darkest moment leads to enlightenment. In the very next scene Sheldrake asks Baxter for the key to his apartment so that he can bring Fran there for New Year’s Eve, and Baxter says no. When Sheldrake threatens to fire him, Baxter angrily throws a key onto Sheldrake’s desk, and the quiet confrontation ensues.

Baxter thought that the way the stand out was to play along, but in the end he discovers that the way to stand out is to stand alone and cease to be a collaborator. Also, Baxter’s transformation, like Rick’s in Casablanca, inspires a conversion in another character, Fran, and in this way it suggests an overturning of the rules of the normal world. As we’ve already seen, Fran is ambivalent about her new relationship with Sheldrake. And when Sheldrake at a New Year’s Eve party tells Fran that Baxter quit and wouldn’t give him the key, she smiles mysteriously as if finally seeing the light.

She realizes it is Baxter who loves her and not Sheldrake. So she abandons her false belief and the negative behavior pattern it engenders. She leaves Sheldrake and rushes to meet Baxter. And that’s the end of the story.

Two men of two minds

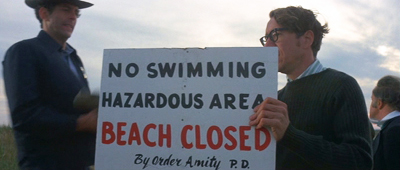

Finally, how enduring are these character-arc patterns? Consider, briefly, Jaws and About a Boy.

Chief Brody is a former New York City police office who has become sheriff of a small island community, Amity. Why did he leave the city? Because, as he explains, crime in New York is out of control and he couldn’t do anything to change that. So he has come to Amity, a world in which, he thinks, one person can make a difference.

Yet for this cop, living in Amity is a cop-out. There hasn’t been a murder there for thirty years. It is a town where one person doesn’t have to make a difference. Yet when the shark arrives, Brody discovers that Amity is the same as New York City. He wants to close the beaches, but the city officials won’t let him. He crumbles under their pressure. Brody is as powerless to make a difference in Amity as he was in New York.

That is how the normal world works in Jaws, and Brody, like Baxter, initially conforms to it. At the beginning of his story he’s defeatist. He always backs down in the face of conflict. He is not confident. Later, on Quint’s boat he wants to turn back. He’s always feeling overwhelmed, a state expressed in his fear of drowning. So Brody goes along to get along.

Accepting his powerlessness is Brody’s negative behavior pattern. But like Baxter and Rick, he can’t help caring. He works to close the beaches, if only for a day, and after a young boy gets killed, he accepts the blame.

Brody exhibits the typical split between positive and negative behavior. Yet because he’s of two minds, he can change. In a crucial turning point, he vows to join Quint and Hooper in hunting the shark. At the climax, he doesn’t back down. He is fearless and he does make a difference. He helps save the town, and in the process he gets over his fear of drowning.

About a Boy, a British-American-French coproduction, released domestically by Universal Pictures, suggests that the techniques I’ve been considering have some cross-border appeal. A 38-year old man-boy, Will Freeman, played by Hugh Grant, lives in luxurious isolation off the royalties from a popular Christmas song his father composed decades before.

Neatly reversing John Donne’s dictum, Will asserts in the opening moments that “all men are islands.” In accordance with this philosophy he has built for himself “a little island paradise,” a swanky apartment filled with cool consumer goods like a chrome-plated espresso maker, a sleek TV, and a vast CD collection. But then Will meets and ultimately befriends Marcus (Nicholas Hoult), a 12-year old misfit with a suicidal mother, who lives his own willed exile because of not being accepted at school.

The story deals with how Will and Marcus and Marcus’s mother Fiona (Toni Collette) become integrated into the world.

Will and Marcus are co-protagonists, but Will’s character arc is more pronounced. Will’s false belief, of course, is that he can make it alone. The problem, though, is that solitude leaves his life devoid of meaning. He has no job and he sleeps with many women but doesn’t date any of them, at least not for very long. As he several times states, “I don’t do anything,” or more to the point, “I do nothing.” Will, however, sees this lack of meaning as a positive: “Me? I didn’t mean anything, about anything, to anyone, and I knew that that guaranteed me a long, depression-free life.”

Will’s false belief is not simply that he thinks he can make it on his own; he believes he can avoid misery by avoiding commitments. This is most apparent when Marcus’s mother attempts suicide.

While Will helps out by driving Marcus to the hospital, the sequence ends with a grim bit of voiceover as we see Will drive off alone into the night.

The thing is, a person’s life is like a TV show. I was the star of the Will show, and the Will show wasn’t an ensemble drama. Guests came and went, but I was the regular. It came down to me and me alone. If Marcus’s mom couldn’t manage her own show, if her ratings were falling, it was sad, but that was her problem.

Will, however, is of two minds, a state the film expresses in a number ways. First, despite being a committed loner, he very early in the plot begins dating a single mother. As we see him gleefully playing with this woman’s young son, he says in voiceover: “And for the next few weeks I was suddenly Will the good guy.”

When Will decides to break up with this woman, in part because she made him late to an IMAX movie, he adds, “I was going to have to end it, but having been Will the good guy I did not relish going back to my usual role of Will the unreliable, emotionally stunted asshole.” He is, apparently, self-aware, and his use of the word “role” seems intentional, suggesting as it does that Will the Asshole is a persona he adopts to avoid complications. We also learn that in the past Will volunteered at a soup kitchen, though he admits he never made it there to help out. And we discover that for a time he worked the phones at Amnesty International, but seems to have mostly used this as an opportunity to pick up women on his call lists.

The point the filmmakers are comically making is that Will has good impulses, but is unable to sustain them in the long term. He has both a positive behavior pattern and a negative behavior pattern, the latter very clearly motivated by his false belief.

The normal world is established as one in which people are abandoned. The film is full of single moms, including Marcus’s mother, and Will tries to abandon everyone he meets. In the opening scene he throws away the phone number of a woman he has slept with, even as she is leaving an inviting message on his answering machine.

Most significantly, Fiona almost abandons Marcus when she attempts suicide. In the wake of this, Marcus is worried that his mother will try again, and that she may succeed when he’s not there. He gets an idea: “Suddenly I realized that two weren’t enough. You needed backup.” With this realization Marcus defines the possible world for us. It is one that is comprised of teamwork and mutual support. In search of this new world, Marcus attempts to fix up Will with his mother. His goal is to get Will to marry her so that they can both look after her.

The dreamed-of marriage never occurs, but Marcus and Will slowly become friends, spending most afternoons together watching TV and sometimes talking. Will helps Marcus become more cool, which allows him to begin making friends at school.

Because of his growing friendship with Marcus, Will comes to realize that misery stems from loneliness, not commitment. He abandons his false belief and the negative behavior pattern it motivates. Not only does he fall in love, but for Marcus’s sake he also offers his friendship and emotional support to Fiona to help prevent her from attempting suicide again. In this way he demonstrates that he has learned the necessity of real, meaningful relationships. The film ends with all the main characters together in Will’s apartment–once his desert island paradise–sharing Christmas lunch. There is even a hint that Fiona too will find love. This ending marks a clear overturning of the rules of the normal world.

Two Minds, Positive and Negative Behaviors, False Belief, Normal vs. Possible Worlds: Maybe all character arcs don’t follow these principles. We’ll have to test them against many more movies. At least, though, they seem to offer widespread, enduring strategies for constructing character change.

In every case I’ve considered, the protagonist discovers his or her “true” self, the good or well-adjusted person that has been lurking within all along. Which suggests that radical, 180-degreee character change is rare–most likely because it is difficult to motivate. Arguably, though, Breaking Bad pulled off a version of it. And speaking of Walter White, it remains to be studied how character change is typically handled in long-form television, which is becoming an ever more significant mode of Hollywood storytelling.

For more on principles of Hollywood plotting, see the entry “Open Secrets of Classical Storytelling,” “Understanding Film Narrative: The Trailer,” and “Time Goes by Turns.” Some ideas about character change are set out in “Three Dimensions of Film Narrative.” There’s a bit on The Apartment as a 1960 film here.

About a Boy (2002).

Living in the spotlight and the shadows: Jeff Smith on TRUMBO

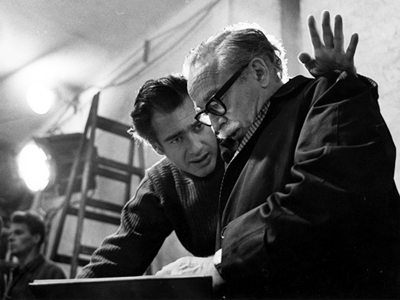

Bryan Cranston as Dalton Trumbo; John Frankenheimer and Dalton Trumbo.

DB here:

Who better to comment on the historical implications of Jay Roach’s Trumbo than our friend and collaborator on Film Art, Jeff Smith? He’s not only an expert on film sound, as he showed in his guest post on Brave, but he has written a book on the Hollywood blacklist. Jeff offers these observations on the film.

Last week, I was delighted to see that Bryan Cranston received an Oscar nomination as the star of Trumbo. Throughout the month of November, I was “johnny-on-the-spot” for local media interested in covering the new biopic about Dalton Trumbo. The story had a local angle. In 1962, Trumbo donated a large collection of scripts, notes, contracts, photos, and business correspondence to the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research. Since then, scholars interested in the Hollywood blacklist have been making pilgrimages to Madison to probe Trumbo’s collection as well as the papers of five other members of the Hollywood Ten (Albert Maltz, Ring Lardner Jr., Herbert Biberman, Samuel Ornitz, and Alvah Bessie.)

I had done a lot of work with the collection, so I could do interviews with WMTV, WISC, The Wisconsin State Journal, and University Publications. Unfortunately I had not yet seen Trumbo, the Jay Roach film based upon Bruce Cook’s 1977 biography. I could talk about Trumbo’s life and career and the buzz I’d heard about the movie, but until it played Madison, I had to stay mum about the movie itself.

After a couple of weeks in distribution in limited release, Trumbo went wide just before Thanksgiving. Now that I’ve seen it, I am delighted to report that Trumbo merits every bit of the hype that surrounded it. To my mind, it is the best fictional film about the blacklist that Hollywood has yet produced.

Buoyed by a standout performance by Cranston, Trumbo is fast-paced and funny, and rather nimbly summarizes many of the political and industrial issues that led to the institution of the blacklist in 1947. It also showcases the effect that “unemployable” writers working on the black market had in undermining the rhetoric of the blacklist throughout the Cold War period. It became hard to say with a straight face that you were protecting American screens from the taint of Red propaganda when films secretly written by Communists were winning awards and topping the box office.

I was struck by some of the choices made by Roach and screenwriter John McNamara in bringing Trumbo’s story to the big screen. Although Trumbo’s career has been well documented by film scholars, Roach and McNamara faced the same challenges in adapting Cook’s biography that any filmmaker does in transforming a literary property into a classical narrative structure. How do you make Trumbo an active, goal-oriented protagonist despite the fact that he was the victim of historical circumstance? How do you deal with the welter of historical actors and subplots that populate Cook’s biography? How do you boil down a complex historical situation into a clear, transmissible narrative?

Witnesses, friendly and otherwise

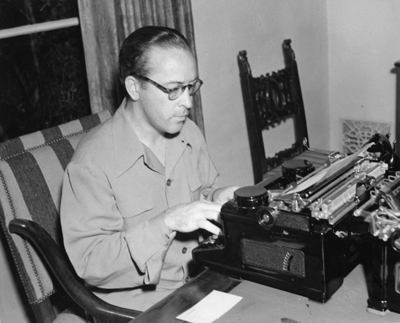

Dalton Trumbo at work.

Like many contemporary Hollywood biopics, Trumbo doesn’t try to convey the full sweep of its subject’s quite colorful life. It omits reference to young Dalton’s Christian Scientist upbringing, his early toils in the Davis Perfection Bakery, or even the publication of his first story in 1933. Indeed, the film also makes only offhand references to Trumbo’s early achievements as a novelist and screenwriter. These are briefly acknowledged near the film’s start through a series of shots in Trumbo’s office at the Lazy-T Ranch that reveal his award for Johnny Got His Gun and his Oscar nomination for Kitty Foyle.

Instead the film focuses on the period of Trumbo’s career during which the screenwriter became one of Hollywood’s sacrificial lambs at the altar of HUAC’s anti-Communism. When the film begins in the mid-forties, Trumbo was the most highly paid screenwriter in Hollywood, earning $75,000 per script. In today’s currency, that amounts to about $800,000 per picture, a remarkable sum for someone under studio contract.

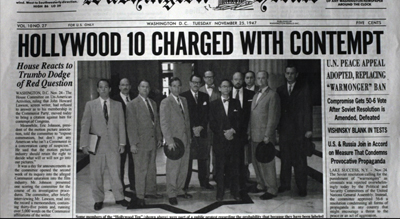

Just a few years later, Trumbo would appear as an “unfriendly witness” during hearings conducted by the House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC) in October of 1947. As a result, he’d eventually be convicted of Contempt of Congress charges and sent to federal prison in Ashland, Kentucky.

Although HUAC was concerned about the potential subversion of American screen content, it was not, in fact, illegal to be a member of the Communist Party. It was, however, a criminal offense to advocate for the overthrow of the American government according to the provisions of the Alien Registration Act (aka the Smith Act) passed in 1940.

About six months after HUAC concluded their hearings on Hollywood, a dozen Communist Party leaders were indicted for Smith Act violations. Defendants insisted that political change in America could be accomplished through democratic process and constitutional principle. But prosecutors claimed these statements couldn’t be trusted since Communists employed “Aesopian language” and therefore did not really mean what they said. The attack proved successful and effectively criminalized membership in the Communist Party as a result. Since any individual’s denial of revolutionary rhetoric would be viewed with suspicion, you were likely seen as guilty of the Smith Act if you simply owned a copy of Marx and Engels’ The Communist Manifesto.

Even before the Foley Square trials, as they came to be known, many of the Communist Party’s rank and file, including the Hollywood Ten, also feared that they would be prosecuted on similar grounds if they admitted their membership. This proved to be one factor that favored the Ten’s failed “first amendment” defense. True, they risked getting cited for Contempt of Congress. But that had the prospect of looking more dignified than simply being hauled off in cuffs on Smith Act charges.

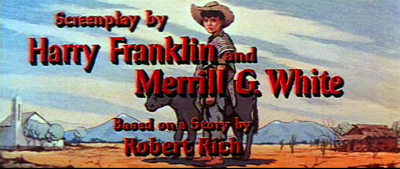

When he returned from prison, Trumbo encountered an industry that wanted him, but not his name on the credits. Producers recognized his talent, and he continued to write through the circuitous network of fronts and pseudonyms. Trumbo would win two Oscars for his work as a black market screenwriter: one for the Gregory Peck/Audrey Hepburn classic, Roman Holiday (below) and another for a Disneyesque “boy and bull” story, The Brave One.

By the end of 1960, Trumbo’s name would once again grace movie screens as the credited screenwriter on Kirk Douglas’ Spartacus and on Otto Preminger’s Exodus. This moment essentially ended what remained of the Hollywood blacklist. In moving from the limelight to the shadows and back again, Trumbo’s life had the kind of plot arc that Hollywood loves. It’s a story of redemption in which the hero overcomes overwhelming odds to regain the professional respect and recognition he’d been denied.

Although all of this suggests that Trumbo is a pretty conventional biopic, it’s quite unconventional in its treatment of the blacklist. As the late Jeanne Hall noted years ago, Hollywood’s representation of this dark chapter of its past was surprisingly evasive, getting on the right side of history but for all the wrong reasons.

Bad Faith in Appleton

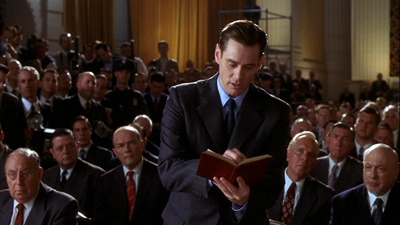

The Majestic (1999).

In titles like The Way We Were, The Front, and Guilty by Suspicion, filmmakers pulled a “bait and switch.” They substituted obvious cases of injustice for the much messier questions posed about HUAC’s abrogation of basic civil rights protections. The Hollywood Ten tried to defend themselves on First Amendment grounds, questioning whether HUAC itself had the right to invade their privacy or to limit their freedom of assembly. But in most of these earlier films about the blacklist, HUAC’s inquiry eventually entangles someone who was never a member of the Communist Party. In The Way We Were, the WASP-y Hubbell comes under suspicion for his relationship with the Jewish radical, Katie. In The Front, Howard comes under suspicion after selling black market scripts by Communist writers under his own name. Both of these instances present obvious cases of individuals wrongfully accused. They recruit our sympathies for characters that suffer as a result of HUAC’s tactics, but gloss over more fundamental questions about whether someone should be denied employment on the basis of their political beliefs.

No film, however, displays the equivocation evident in previous representations of the blacklist as vividly as Frank Darabont’s The Majestic. The protagonist, Peter Appleton, is a Hollywood screenwriter who has just been named by the committee. Distraught, he takes a drive out of Hollywood, but has an accident en route. Suffering from amnesia, Appleton finds himself in the small town of Lawson, California where is mistaken for Luke Trimble, a soldier killed in action some nine years earlier. Appleton becomes immersed in the Lawson community, helping his “father,” Harry, restore the small town theater that gives the film its title. Prompted by a combat film shown in the Majestic, Appleton regains his memory, and confides the truth of his situation to his new girlfriend. After his car is discovered, federal agents give Appleton a summons to testify about his Communist affiliations.

During the climax, Appleton appears before HUAC with the aim of clearing himself. Congressman Elvin Clyde confronts Appleton with evidence that he attended a meeting of the “Bread Instead of Bullets” club. Appleton pleads innocence, saying he only went because he was a “horny, young man” seeking to impress his date, Lucille Angstrom. Just as he is about to deliver his prepared statement purging himself of Communist associations, Appleton changes his mind. Instead he gives an impassioned speech that cites his First Amendment rights and denounces the investigation as a betrayal of America’s real ideals. Appleton saunters out of the hearing to the loud applause of onlookers. Yet Appleton’s lawyer later tells him that Angstrom is currently a CBS producer on Studio One, and his reference to her as a member of the Communist front organization is viewed as cooperation with the Committee.

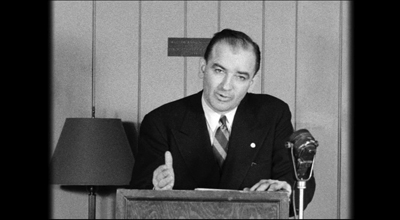

In The Majestic’s civic fantasy, the committee hearing revives the “wrongly accused” trope seen in earlier blacklist films. Worse, it shows its hero successfully using the First Amendment legal defense that had spectacularly failed when the Hollywood Ten used it during the 1947 hearings. Moreover, because Appleton is a political naïf, his inadvertent naming of names redounds to his benefit. Given the film’s hopelessly confused politics, perhaps there is unintentional irony in the fact that Appleton is also the name of the Wisconsin hometown of Senator Joseph McCarthy (below), the man synonymous with the Cold War’s anti-Communist campaign.

Trumbo, in contrast, doesn’t pull any punches. The film condemns HUAC’s activities not because it was prone to wild, unproven accusations like those of McCarthy, but rather because the very nature and essence of its inquiry was itself an abuse of power. The movie does nothing to deny Trumbo’s guilt. Indeed, the real-life Trumbo freely admitted it. In the 1976 documentary Hollywood on Trial, Trumbo described his reaction to his trial thusly: “As far as I was concerned, it was a completely just verdict. I had contempt for that Congress and have had contempt for several since.”

Yet, while not excusing Trumbo’s actions, the film dramatizes the debilitating effects of being blacklisted, both in his professional and personal life. The burden of Trumbo’s black market work put a strain on his marriage and his family, all of whom were enlisted to perform services he himself could not do publicly.

The blacklist: More than Red-baiting

Besides providing a more accurate picture of Red-baiting and its effects, Trumbo also proves remarkable in making passing reference to some of the important secondary causes that eventually led to the blacklist. An early scene, for example, shows Trumbo (above) on a picket line during the vituperative Congress of Studio Union strikes that took place in 1945. Film historian Jon Lewis argues that one reason for the studio’s cooperation with HUAC’s investigation was that it served their interests in their long-term relationship with Hollywood’s craft guilds. Once Communists within the film industry’s labor unions became targets of government scrutiny, only the more moderate factions remained. Whether or not HUAC’s investigation was a direct cause, Hollywood did not experience another strike until more than four decades later.

Trumbo refers to another cause of the blacklist: anti-Semitism. Although it was something of a stereotype, Communists were popularly associated with European Jews. In fact, when Warner Bros. released I Was a Communist for the FBI in 1951, several moviegoers wrote studio head Jack Warner complaining that the film repeated the lie that all Jews were Communists. Said one Julius Newman of Roxbury, Massachusetts: “I demand that this dangerous, rotten, and libelous bit of propaganda be withdrawn immediately before some Jewish mother somewhere, gets her son’s skull cracked for Mother’s Day.”

The perception that anti-Semitism was an underlying cause of the blacklist was aided by the fact that three of the Committee were members of the Ku Klux Klan at the time of the 1947 hearings, including the Chair, J. Parnell Thomas. Moreover, in a speech before the House of Representatives, another HUAC member, Mississippi Democrat John Rankin, attacked members of the Committee for the First Amendment, who had lobbied on behalf of the Hollywood Ten. Rankin claimed that certain performers were suspect because their Anglicized names hid their actual Jewish origins:

One of the names is June Havoc. We found that her real name is June Hovick… Another one is Eddie Cantor, whose real name is Edward Iskowitz. There is one who calls himself Edward Robinson. His real name is Emanuel Goldenberg. There is another here who calls himself Melvyn Douglas, whose real name is Melvyn Hesselberg.

Screenwriter John McNamara wrote a similar speech for Trumbo, but placed it in the mouth of gossip columnist Hedda Hopper. When MGM boss Louis B. Mayer reminds Hopper that the legal situation was complicated by the fact that several of the Hollywood Ten had contracts, she responds:

Then how about I make crystal clear to my thirty-five million readers who runs Hollywood and won’t fire these traitors? How about I name names, real names? Like yours, Lazar Meir; or Jack Warner, Jacob Varner; Sam Goldwyn, Schmuel Gelbfisz.

The presence of Hedda Hopper in Trumbo hints at a third underlying cause of the blacklist: the role of the trade press and gossip columnists, who prosecuted and enforced it. Hopper was not alone in this endeavor. Publishers like Billy Wilkerson of The Hollywood Reporter and columnists like Walter Winchell and Ed Sullivan “cheered” HUAC’s efforts from the sidelines. They also helped the enforcement of the blacklist once it was instituted, calling public attention to the surreptitious presence of banned writers on the black market.

All of these elements in Trumbo’s script make it a richer, more sophisticated depiction of the Hollywood blacklist than that offered by its predecessors. They also remind us that its operations were about more than just politics. Once the blacklist was established, studio bosses gained the upper hand in their dealings with labor, gossipmongers used rumor and accusation to fill column inches and sell papers, and anti-Semites exploited the common association of Communism and Jewish intellectuals to thwart activism among progressives, including those in the Civil Rights movement.

In sum, Trumbo offers a more nuanced sense of the various factors at play at the time of the blacklist than virtually all of its cinematic predecessors. This makes it all the more surprising then that the film nonetheless rewrites history in other ways. In an effort to both streamline and personalize its protagonist’s story, Trumbo invents new characters, revises the order of historical events, and shorts the achievements of other black market screenwriters who also contributed to the blacklist’s ultimate demise.

The eleventh member of the Hollywood ten

Although most film audiences expect that movies will generally portray historical events with some degree of accuracy, Hollywood cinema rewrites history all the time. Despite the fact that this is common practice, some films that take such liberties are hurt by negative publicity, especially around awards time. Recall the controversy surrounding Selma’s depiction of President Lyndon Johnson as an opponent of Martin Luther King’s famous march rather than as a “behind the scenes” ally. Some believe that the loud complaints coming from the LBJ camp cost director Ava DuVernay an Oscar nod.

Trumbo is no exception to this principle, even though it has been unusually forthright about the changes made to the historical record. My spidey senses were alerted to this during the movie when they introduced Louis CK’s character as “Arlen Hird.” I’d never heard of Arlen Hird.

Both in interviews and in an article in the New York Times, screenwriter John McNamara has acknowledged that Hird is a composite character, whose traits and experiences are based on five other members of the Hollywood Ten. Louis CK, for example, physically resembles the real-life Alvah Bessie, who, like the character, was a member of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade in the Spanish civil war.

Moreover, when Hird is in prison, he hears a radio broadcast of Edward G. Robinson’s “friendly” testimony. Robinson calls him “the top fellow who they say is the, uh, commissar out there,” a swipe that blacklist historians would immediately associate with John Howard Lawson. And sadly, like Samuel Ornitz, Hird dies after battling cancer, having never seen the blacklist come to its ignoble end.

As Nicolas Rapold observes in the Times, Hird is meant to stand in for other Communist screenwriters whose attitudes were more doctrinaire than Trumbo’s. Yet I believe the real purpose of using a composite character is to simplify the historical record to make it more digestible for the viewer. Rather than tracing out Trumbo’s relation to all of the eighteen other “unfriendly witnesses” subpoenaed by HUAC, McNamara opts to consolidate them into a single character. Such a decision makes some intuitive sense, since viewers would be hard pressed to keep tabs on a parade of many characters. By creating Hird as a composite, Trumbo’s interactions with him gain vividness and salience.

Still, McNamara’s narrative technique is merely one approach among a larger menu of options, each of which has its own strengths and weaknesses. He could have treated the Hollywood Ten as a group protagonist, who all share the same goal in legally challenging HUAC’s authority. Such a gambit, though, would have displaced Trumbo from the center of the story early on. That decision would have weakened the causal motivation behind his later emergence as a black market crusader.

Alternatively, McNamara could have dramatized Trumbo’s individual interactions with Bessie, Lawson, and Ornitz, et.al., using a superimposed title to identify each one. The gain in accuracy, though, would likely mean a loss of dramatic clarity and a mildly more self-conscious style of narration. More important perhaps, it also would make for a less emotionally engaging story. The film shows Hird confiding in Trumbo at the Lazy-T ranch, participating in the Ten’s legal strategy, serving his prison term, and undergoing surgery for lung cancer. The accumulation of these details provide for a more fully fleshed out character. There’s also the opportunity to feel empathy for Hird’s children at his funeral, an effect that couldn’t have been as focused if Hird’s problems were scattered among separate individuals.

None of this is meant to suggest that McNamara absolutely made the right choice in deciding to treat so many members of the Ten as a composite. Rather, it is simply the recognition that such a technique is the result of a deliberate choice and further that one creative decision can lead to a cascade of others. Had McNamara stayed doggedly faithful to the historical record, Trumbo would have been a different film, but perhaps not a better one.

Perhaps we should recognize that screenwriters often must adapt historical narratives in the same way that they adapt literature. And the same sorts of questions about fidelity will bedevil us as when films change details of our favorite novels and stories. Rather than being dogmatic in expecting that historical films stick close to the facts, maybe we simply should ask whether the film is faithful to the spirit of the historical record, especially when its creators are so open and honest about the changes they made. Such a stance would at least recognize the difficulties faced by screenwriters in balancing the weight of classical narrative conventions against the strict measure of historical accuracy. If, as many screenwriters argue, films differ from literature in their emphasis on conflict and action, then the decision in Selma to treat LBJ as an obstacle to Martin Luther King’s goal makes a certain dramatic sense. Here again, one can debate the merits of that creative choice. But at least we do so with a fuller understanding of why such choices are made in the first place.

Get me rewrite!

Besides creating composite characters, McNamara rewrites history in other ways. Perhaps the most obvious is when he creates a scene in prison between Trumbo and HUAC chair, J. Parnell Thomas, which never actually happened. True, Thomas was convicted on corruption charges and was sent to federal prison. But he served his term in Danbury, Connecticut rather than Ashland, Kentucky where Trumbo was incarcerated.

In this case, the real-life story proves more entertaining than what appears in the film. While at Danbury, Thomas encountered two other members of the Hollywood Ten – Lester Cole and Ring Lardner, Jr. — serving their time on Contempt of Congress charges. Upon seeing Thomas working in the prison yard, Cole made a wisecrack that led the former HUAC chair to respond, “I see that you are still spouting radical nonsense.” Cole’s sharp retort: “And I see you are still shoveling chicken shit.”

In other cases, McNamara revises the chronology of events. In the film, Trumbo first meets with the King Brothers, Frank and Hymie, just after he is released from prison. In reality, Trumbo started working for the King Brothers just weeks after his HUAC testimony. Almost immediately after being suspended by MGM, Trumbo did black market work on the screenplay for the King Brothers’ cult classic, Gun Crazy, using fellow writer Millard Kaufman as a front. With Kaufman serving as intermediary, the Kings likely did not know of Trumbo’s involvement. But the brothers began working directly with Trumbo shortly thereafter. In fact, Frank King personally visited the Lazy-T ranch just prior to the Trumbo’s departure for prison, offering to pay him $8,000 to write the script for Carnival Story.

Trumbo coyly acknowledges the screenwriter’s contribution to Gun Crazy by featuring posters of the film in several shots. But by revising the historical circumstances of Trumbo’s first involvement with the Kings, the film more or less denies him actual credit attribution, ironically engaging in the same sort of opportunism displayed by the producers who surreptitiously hired him.

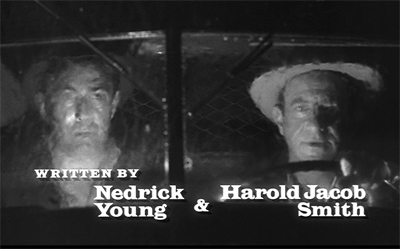

McNamara’s most significant changes to blacklist history, though, involve omissions. Trumbo’s Oscar victory for The Brave One is well documented and the episode – both in the film and in real-life – neatly captures his role as industry gadfly. But the same year that the mysterious “Robert Rich” won the Academy Award for Best Original Story, Michael Wilson also was nominated for a project for which he was publicly denied screen credit.

Wilson had completed a first draft of Friendly Persuasion for director Frank Capra in 1946, but no film was made from the script until producer/director William Wyler took over the project in 1955. When it came time to determine the screenwriter credit, Wyler suggested that it go to Robert Wyler and Jessamyn West for their extensive revisions, including many rewrites completed on set during shooting. When Wilson became aware of this, he immediately protested Wyler’s decision and forced arbitration by the Screen Writers Guild. The Guild ruled in Wilson’s favor, but also reminded the film’s distributor, Allied Artists, that they could legally deny credit to any screenwriter who had failed to clear himself before HUAC. When Friendly Persuasion was released in 1956, its only writing credits read “From the Book by Jessamyn West.”