Archive for the 'Screenwriting' Category

Caught in the acts

Kiss Kiss Bang Bang (2005).

DB here:

If you’re interested in how films tell stories, I think that you’re interested in several dimensions of narrative. Those include the story world (characters, settings, action), narration (how story information is parceled out as the film unrolls), and plot structure (the arrangement of parts).

Plot structure matters because a movie’s parts, like parts of a song or a symphony, help shape our experience. Just as a “curtain line” makes us return after intermission, a cliff-hanging climax to a TV episode makes us tune in next week–or click to continue, if we’re binge-watching. Accordingly, storytellers reflect on how to chop up and lay out sections of their plots. Novelists fret over chapter divisions, TV writers massage their scripts to allow for commercial breaks, and playwrights map action into acts.

The idea of act-structure has passed into commercial screenwriting as well. Just when that happened is hard to say, but certainly by the 1980s scriptwriters consciously broke their screenplays into big chunks. That trend was largely the result of Syd Field’s 1979 book Screenplay: The Foundations of Screenwriting, although some of his points had been anticipated in Constance Nash and Virginia Oakley’s Screenwriter’s Handbook (1974). From these books came the idea that a feature film script had a three-act structure, measured by time segments (30 minutes/ 60 minutes/ 30 minutes). The prototype was a 120-minute film, with each script page running about one minute of screen time. Field fleshed the model out by noting that “plot points” at the ends of acts one and two turned the conflicts in a new direction. Although other writers argued for other templates, and Field’s model was refined (what’s the “inciting incident” in Act One?), versions of the three-act model still rule the international film industry.

Field presented his anatomy as an analysis of hit films like Chinatown and Close Encounters of the Third Kind. He suggested it as a template for a successful plot. As Field’s book gained prominence, his guidelines gave production companies an heuristic for triaging submissions. Now a story analyst could simply check pages 25-35 and 55-65 for turning points, and “incorrect” scripts could be discarded immediately. (But see P.S. below.) Through a feedback cycle, the Field model became a guide to both screenwriters and industry decision-makers. Inevitably, the whole thing got mocked. The day-by-day structure of Shane Black’s Kiss Kiss Bang Bang parodies Field’s scheme, and it closes with a self-conscious epilogue. “So,” says the narrator, “that’s pretty much that….”

To what extent, though, was the three-act structure employed in earlier eras? Field’s original edition drew its examples from current hits, but he implied that classics would display the same underlying architecture. Kristin, in Storytelling in the New Hollywood, claimed that four parts were more common than three, and she supported her analysis with examples from films from the silent era and the classic studio years.

But film analysis depends on your perspective. In any movie you can find patterns different from the ones I find, and each of us can make persuasive cases. It would be valuable to know whether American screenwriters in the studio system consciously worked with an act-based model. If they did, what assumptions did they make about the length and organization of each act?

Some poor sucker of a screenwriter

Steven Price’s new book, A History of the Screenplay, surveys the practices of screenplay composition in America and Europe. It traces the early years of outlines and scenarios through the continuity script of the silent years, the sound screenplay, and postwar European models, up to the New Hollywood and contemporary standards. It’s a fascinating study and sure to set a benchmark in our understanding of the conventions of screenwriting. For the 1930s and 1940s in America, Steven shows that filmmakers used two formats, either the “master-scene” one or a format involving more explicit instructions about camerawork, lighting, and other aspects. But he finds little direct evidence that screenwriters of the studio era consciously applied a three-act structure.

Steven Price’s new book, A History of the Screenplay, surveys the practices of screenplay composition in America and Europe. It traces the early years of outlines and scenarios through the continuity script of the silent years, the sound screenplay, and postwar European models, up to the New Hollywood and contemporary standards. It’s a fascinating study and sure to set a benchmark in our understanding of the conventions of screenwriting. For the 1930s and 1940s in America, Steven shows that filmmakers used two formats, either the “master-scene” one or a format involving more explicit instructions about camerawork, lighting, and other aspects. But he finds little direct evidence that screenwriters of the studio era consciously applied a three-act structure.

For some time, I’ve held the same view. I couldn’t find any script draft broken into acts. Some veteran screenwriters admitted using a three-act model in plotting, but their testimony came long after the era. So, for instance, Philip Dunne says he used a three-act organization for his 1940s screenplays, but he makes the claim in an interview published in 1986. Billy Wilder says he “wrote [Charles Boyer] out of the third act” of Hold Back the Dawn (1941), but the remark comes in an interview given decades later. There’s always the possibility that older writers, newly aware of the Fieldian template, were projecting it backward onto their work—assuring us that they conform to contemporary standards, or even asserting precedence.

Similarly, we can’t rely too much on secondary sources. True, screenplay manuals, from at least 1913 onward, have recommended a three-part structure, purportedy corresponding to Aristotle’s idea that a plot must have a beginning, a middle, and an end. But this rests on a misunderstanding. As I’ve mentioned before, Aristotle isn’t talking of acts; ancient Greek plays didn’t have act divisions. And almost none of the manuals use the term “acts” to describe the parts.

Richard Brooks’ novel The Producer (1951), about a weak-willed executive trying to do the right thing, offers some hints along similar lines. He mentions that a screenplay should run to 120 pages, confirming the canonical length that Field proposes. Likewise, Brooks obliquely appeals to Aristotle.

Some poor sucker of a screenwriter has to create a beginning, a middle and an end, and all the dialogue.

Perhaps there’s an intentional irony in the fact that Brooks’ Hollywood exposé is itself broken into three parts, labeled “The Beginning,” “The Middle,” and “The End.”

Unlike many authors of manuals, Brooks was an established screenwriter, and we might expect his novel to refer to acts. It doesn’t. But Lewis Herman, a minor scribe with three screen credits (including Anthony Mann’s Strange Impersonation), does. His 1952 manual declares that a feature-length film is built upon “a three-act theme outline.” The context suggests that the Hollywood studios demand this as a step toward developing a full screenplay. Herman usefully illustrates the outline with a hypothetical example.

Still, manuals or novels aren’t ironclad sources for studio practice. Better would be contemporaneous evidence from memos, story conferences, and similar unpublished documents. Claus Tieber has done extensive research into such sources and has found no discussions of three-act structure. I’ve found a few, but they’re fairly sketchy.

Overseeing Casablanca, Hal Wallis told Michael Curtiz, “The Epsteins have agreed to deliver the film’s ‘second act’ the following day.” Darryl F. Zanuck mentioned the “last act” in correspondence about Viva Zapata! and On the Waterfront. Supposedly John F. Seitz asked Preston Sturges about the flashback structure of The Great Moment: “Why did you end the picture on the second act?” As I noted in an earlier entry, David Selznick’s papers record a story conference on Portrait of Jennie in which Jed Harris remarks: “The second act–he must get the picture back because that’s all he’ll ever have of her.” He adds that at this point the film “is about 1/3 gone.” This suggests that some practitioners thought of the parts as roughly equal in length. (Kristin’s model proposes that this was the case.)

It may be, of course, that three-act structure of some sort was so ingrained in studio writers’ habits that they didn’t have to discuss it explicitly. Field was addressing aspiring screenwriters who wanted inside knowledge, but as intuitive craft workers, the old contract writers wouldn’t be likely to spell out rigid rules about length and dramatic patterning.

Since corresponding with Steven for his book, I’ve found that one screenwriter explicitly invoked three-act structure in his working notes. And I’m embarrassed not to have noticed it earlier.

Coupling, recoupling, and Joe Breen

F. Scott Fitzgerald and Sheilah Graham.

NICOLAS: Marriage has its phases–its acts–like anything else. This is another act, that’s all.

F. Scott Fitzgerald, screenplay for Infidelity.

F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Hollywood career was mostly a fiasco. Thanks to temperament, a mentally disturbed wife, bouts of breakdown and alcoholism, and an implacable industry, he worked his way down the hierarchy to unemployment. From July 1937 to his death in 1940, he earned screen credit for just one film, Three Comrades (1938). He also started, but didn’t finish, the best Hollywood novel I know, The Love of the Last Tycoon (aka The Last Tycoon). I think it spells out some features of the Hollywood aesthetic with special vividness.

In early 1938 Fitzgerald began a screenplay for MGM producer Hunt Stromberg (right). Given a title, Infidelity, Fitzgerald came up with a script centered on a dead marriage. What has turned happy young lovers into a polite, numb couple? An extended flashback shows that two years earlier the husband Nicolas re-met his former secretary while his wife Althea was abroad taking care of her sick mother. The secretary, Iris, spent one night at Nicolas’ luxurious home, and it’s implied that they had sex. At breakfast, Althea returned home unexpectedly and found Iris at breakfast. After this, Althea remained married to Nicolas, but simply lived with him in detached ennui.

In early 1938 Fitzgerald began a screenplay for MGM producer Hunt Stromberg (right). Given a title, Infidelity, Fitzgerald came up with a script centered on a dead marriage. What has turned happy young lovers into a polite, numb couple? An extended flashback shows that two years earlier the husband Nicolas re-met his former secretary while his wife Althea was abroad taking care of her sick mother. The secretary, Iris, spent one night at Nicolas’ luxurious home, and it’s implied that they had sex. At breakfast, Althea returned home unexpectedly and found Iris at breakfast. After this, Althea remained married to Nicolas, but simply lived with him in detached ennui.

Back in the present, to ramp up his mood, Nicolas decides to hold a party in the country estate he had more or less abandoned. At the same time, Althea rekindles her friendship with a former suitor, Alex. She can’t arouse herself to passion, though, and Alex leaves her. As she drives more or less hysterically to the estate where the party is in full swing, Nicolas is wandering through his mansion among the shrouded furniture.

At this point, because of objections from the Production Code office, Stromberg halted Fitzgerald’s work on the screenplay. Aaron Latham’s biography tells us that Fitzgerald had planned to present a reconciliation, in which a photographic trick presents Althea seeing herself as Iris and thus forgives Nicolas. But this ending would suggest that the husband’s sin went unpunished. Fitzgerald suggested an alternative, but this too was rejected by Joseph Breen. He tried to redraft the script later in 1938, but the project dissolved.

Fitzgerald had systematically studied Hollywood releases, even filing plot synopses on index cards. Accordingly, the Infidelity screenplay we have shows an awareness of 1930s storytelling conventions: montage sequences, wordless scenes, and revealing visual detail. We learn that Nicolas’ ardor is cooling when we notice that he has stopped opening Althea’s letters. Fitzgerald’s acquaintance with current trends led him to a thumbnail characterization of Althea’s friend Alex:

He is the type played by Ralph Bellamy in The Awful Truth–handsome, attractive, worthy, thoroughly admirable, but somehow too heavy in manner to grip the sympathy of an audience if playing opposite a man of charm.

Occasionally, voice-over dialogue in the present is matched with images in the past, in the manner of Sturges’ “narratage” in The Power and the Glory. (See our entry here.) And the large-scale flashback structure, leaving a key action in the present suspended for nearly an hour, anticipates a mode of construction that would be common in the 1940s.

Despite its up-to-date air, the plot of Infidelity creaks a bit. It relies on a great many coincidences and introduces rather late a major menace, a sinister surgeon who seems slated to play the disruptive role of George Wilson in Gatsby. But what’s of special interest to us is a schedule of work that Fitzgerald sent to Stromberg during the planning stages.

Fitzgerald groups his scenes into clusters, and alongside each one he notes a date on which he expects to complete it. Since each scene usually runs only a couple of pages, the groupings present a feasible day-by-day timetable. These clusters of scenes are gathered into eight “sequences,” labeled with Roman numerals. In the 1930s, a “sequence” meant, according to screenwriter Frances Marion, “a series of scenes in which the action is continuous without any break in time.” Each of Infidelity‘s sequences presents a unified phase of the action and is more or less continuous in time, although there are some ellipses as well.

Here’s the news: Fitzgerald’s timetable assembles the sequences into acts. Sequences I through IV are labeled “FIRST ACT 45 pages.” Sequences V through VIII are labeled “SECOND ACT 50 pages.” Sequence VIII is continued to form “THIRD ACT 25 pages.”

The first act establishes the loveless marriage and launches the flashback. While Althea is away, Nicolas re-encounters Iris. Meanwhile, as Althea and her mother are on their way home, they conveniently run into her old beau Alex. Their departure for the United States ends this setup. In the screenplay Fitzgerald has typed: “The First Act may be said to end here.”

The second act develops the conflict to a point of crisis. Althea returns a week early to find Iris at breakfast with Nicolas. She resigns herself to a loveless union. Back in the present, he plans the party and at the instigation of Althea’s mother Alex starts to woo her. But he abandons Althea, and by chance she’s found by Dr. Borden, whom she starts kissing. In the notes for Sequence VIII, Fitzgerald cryptically ends the act on an alternation between the couples:

CUT TO husband and back to old beau [Alex]

[Alethea] with beau [Alex]

Crisis with beau and switch [to the surgeon, Dr. Borden?]

CUT TO husband

After presenting this alternation in scenes, the manuscript concludes:

Full shot of a bedroom, large and luxurious like everything else in this house. Soft lighting, everything covered with cloth or canvas.

Nicolas Gilbert is standing in the middle of the floor.

Close shot of Nicolas.

This is presumably the end of the passage labeled “CUT TO husband.” In the Stromberg schedule, this last portion marks the end of Act Two. Act Three isn’t in the canonical version of the screenplay.

A couple of final points about the structure. Although the screenplay is estimated at 120 pages, its proportions don’t conform to the Field paradigm. At 25 pages or minutes, the third act is short. This is a characteristic of both modern and older Hollywood climax sections. But Act One was projected to be very long at 45 pages, and Act Two approximates it at 50. Fitzgerald’s layout is perhaps more characteristic of a stage play, which can afford a longish exposition and equivalent second act. In the script version we have, both acts run equivalent page lengths.

Fitzgerald may have expected some trimming and compression at later stages. In The Producer, Brooks’ protagonist notes that a 120-page script would usually be cut down to 90 minutes because exhibitors wanted films at about that length. It’s true that few films of the studio era run to two hours.

Set aside brute measurements. What, in Infidelity, makes an act a coherent unit? Not a specific span of time. Act One breaks off partway through the flashback, and Act Two ends before the evening party does. The first act ends when we know a crisis is coming: Althea is returning home early and hasn’t told Nicolas, whom we’ve seen flirting with Iris. Act Two ends at another high point. Nicolas confronts the emptiness of his life without his wife, and nearby Althea is heedlessly making love to a stranger with dubious designs. We could easily imagine the script as a stage play, with a curtain ringing down on each of these teasing situations.

In sum, we have one clear-cut case of a studio screenwriter laying out his plot in three acts. We can’t generalize from a single instance, of course, and we would need many more pieces of evidence to consider this a widespread writing strategy. Perhaps Fitzgerald isn’t typical. Did his relative inexperience as a screenwriter make him rely on a theatrical template that others could do without? Did he employ it more as a rhetorical device to convince Stromberg that the plot was firmly constructed? Still, taken with the reminiscences of Dunne, Wilder, et al. and the sketchy mentions we have in production records, the Infidelity project suggests that some conception(s) of three-act structure were operative in the studio period.

Needless to say, we’ll need even more evidence before we can begin to consider whether the filmmakers’ craft practice matches the structural patterns that today’s analysts disclose in the films. The search continues!

The Fitzgerald outline is reproduced on pp. 161-162 of Aaron Latham, Crazy Sundays: F. Scott Fitzgerald in Hollywood (Viking, 1971). This book is not only a stimulating account of the novelist’s Hollywood years but also a helpful view of the movie colony’s culture. My discussion relies upon the version of Infidelity published in Esquire 80, 6 (December 1973), 193-200, 290-304. It is available in a digitized version here. The original manuscripts are in the University of South Carolina library.

Philip Dunne’s remarks about three-act structure are in Pat McGilligan, Backstory (University of California Press, 1988), 158. Billy Wilder’s remarks come in George Stevens, ed., Conversations with the Great Moviemakers of Hollywood’s Golden Age (Knopf, 2006), 316. (In the same interview Wilder claims that Some Like It Hot has four acts.) Richard Brooks’ The Producer (Simon & Schuster, 1951) is worth reading for its almost documentary survey of the process of production at the period. Lewis Herman’s Practical Manual of Screen Playwriting for Theater and Television Films (World, 1952) is an unusually detailed guidebook.

On Wallis’ memo about Casablanca‘s second act, see Marshall Deutelbaum, “The Visual Design Program of Casablanca,” Post Script 9, 3 (Summer 1980), 38. For Zanuck’s comments see Memo from Darryl F. Zanuck: The Golden Years at Twentieth Century-Fox, ed. Rudy Behlmer (Grove, 1993), 173, 226. Seitz’s remark to Sturges about The Great Moment is quoted in James Curtis, Between Flops: A Biography of Preston Sturges (Harcourt, Brace, 1982), 172. There’s more discussion in our blog entry on The Great Moment.

I take Frances Marion’s definition of “sequence” as a bundle of scenes from her How to Write and Sell Film Stories (Covici-Friede, 1937), 373. Tamar Lane offers a comparable definition in his New Technique of Screen Writing (McGraw-Hill, 1936), 123. Interestingly, Lane adds that some scenarists think of each sequence as moving toward a high point, like an act in a play; but this seems only a rough analogy, and the comparison entails that a script would have several more “acts” than three. Steven Price suggests that the “sequence” as an extended script segment emerged in the silent period and hung on in some sound screenplays; see A History of the Screenplay, especially 63, 115-116, and 153-157. At the same time, “sequence” could refer to a single brief segment, as in “action sequence” or “montage sequence.”

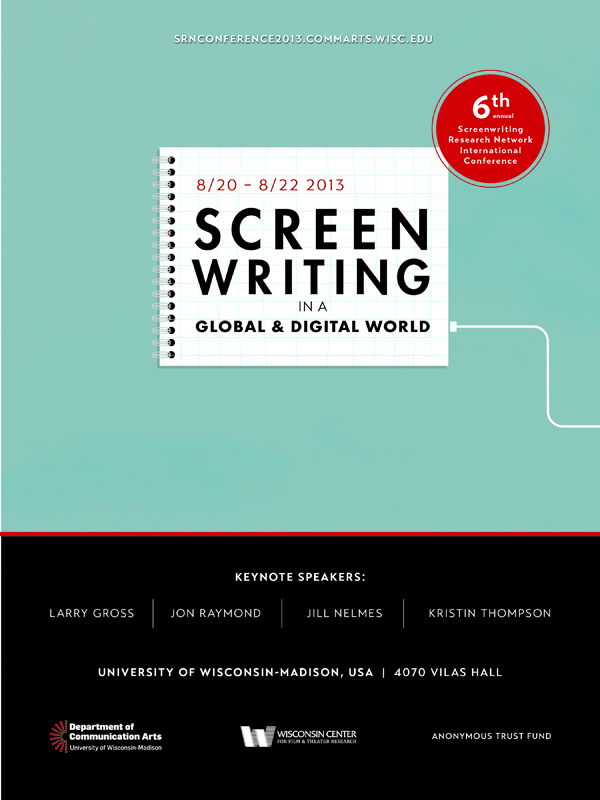

Thanks to Steven Price and Claus Tieber for correspondence about act structure. Claus has a relevant case study of Grand Hotel, “‘A Story Is Not a Story But a Conference’: Story Conferences and the Classical Studio System,” in Journal of Screenwriting vol. 5, no. 2 (2014): 225-237. More generally, I’m grateful to researchers at the Screenwriting Research Network for what I’ve learned from their conferences in Brussels in 2011 and in Madison in 2013.

Other entries on this site have considered act structure. Kristin explains her model, based on goal formulation and injections of new information. She expands on this as it affects character subjectivity and point of view. I illustrate her model with reference to what is supposedly the most wayward and narratively fragmented modern genre, the action picture. I offer some general reflections on how the four-part structure informs not only current films but best-selling novels. For a more general discussion of the dimensions of film narrative, you can download this chapter from my Poetics of Cinema. Also, too: there’s the precept that form follows format. Finally, I consider modern trends in screenplay construction, including act structure, in The Way Hollywood Tells It.

After a while you see the triplicate scheme everywhere. In Case History of a Movie (1950), p. 30, Dore Schary says that Charles Schnee turned in the script of The Next Voice You Hear in thirds. Acts? I’ll have to get back to you.

P.S. 19 May 2014: In reply to this post, Greg Beal comments that my discussion of rejecting screenplays based on Field’s plot points is inaccurate.

My claim was, I now think, an overstatement. I should not have suggested that the absence of canonical plot points would be sufficient to doom a screenplay. Naturally, I realize that the analyst would still be obliged to write fuller coverage. I meant simply that the Field template could set up expectations that the script wasn’t written to standard. Other factors would surely be taken into account in a final decision. The larger point, that three-act structure along Field’s lines shapes analysts’ judgment, remains to be determined.

My most concrete evidence for the saliency of the three-act, plot-point model in this production context comes from two manuals by story analysts. T. L. Katahin’s Reading for a Living: How to Be a Professional Story Analyst for Film and Television (Blue Arrow, 1990) recommends that analysts look for three acts, including a ten-page initial setup followed by a development and two further acts that forward the protagonist’s goals. But Katahin doesn’t propose exact page counts for further twists.

More specific is Jennifer Lerch’s 500 Ways to Beat the Hollywood Script Reader: Writing the Screenplay the Reader Will Recommend (Simon and Schuster, 1999). In following the three-act layout, she suggests that Act One, the setup, be consummated between pages 20 and 30 (ideally consisting of two scenes 10-15 pages each). Act 2, as per Field, is said to run long, up to pages 80-90, and typically consists of four to eight sequences (each 10-15 pages or so). This act is said to lead to a point of no return, the pivot-point for Act 3.

Lerch, who was a professional story analyst for the William Morris Agency for eight years, claims, “Your script’s setup can literally make or break your project in the Hollywood Reader’s eyes, particularly at some companies that instruct readers to stop at page thirty of a script if it looks substandard. You may have a great second act and climactic sequence, but Hollywood will never see it unless you give it a savvy setup” (91). Passages like this one led me to think that the Field template weighs quite strongly in analysts’ judgment. But I’ve never supervised story analysts, so I welcome Greg’s expert comment on the matter.

P.P.S. 20 May 2014: More information on Fitzgerald’s Infidelity screenplay and its act breaks. In a letter to Hunt Stromberg dated 22 February 1938, Fitzgerald wrote:

The first problem was whether, with a story which is over half told before we get up to the point at which we began, we had a solid dramatic form–in other words whether it would divide naturally into three increasingly interesting “acts” etc. The answer is yes. . . .

This point, the decision to sail, also marks the end of the “first act.” The “second act” will take us through the seduction, the discovery, the two year time lapse, and the return of the old sweetheart–will take us, in fact, up to the moment when Joan [later, Althea] having weathered all this, is unpredictably jolted off her balance by a stranger. This is our high point–when matters seem utterly insoluble.

Our third act is Joan’s recoil from a situation that is menacing, both materially and morally, and her reaction toward reconciliation with her husband.

Evidently the timetable reprinted in Crazy Sundays was prepared after this letter was sent. This letter is printed in F. Scott Fitzgerald: A Life in Letters, ed. Matthew J. Bruccoli (Scribners, 1994), 348-349.

P.P.P.S. 30 May 2014: I always enjoy getting correspondence from readers, and I must catch up by noting some other responses I’ve received. David Cairns, whose wonderful blog Shadowplay is always worth checking on (his latest post is on Hannibal, the TV show), writes with this comment:

Hold Back the Dawn (1941).

Somewhere it’s always GROUNDHOG DAY

Phil earns his groundhog halo.

Kristin here–

Back in 1999, my book Storytelling in the New Hollywood (Harvard University Press) was about to be published. It was an attempt to suggest that, contrary to the talk of “post-classical” or “post-Hollywood” norms having taken over American filmmaking, the most important classical principles that had been at work since the 1910s were still going strong.

I outlined those principles in the opening chapter, discussing character goals, deadlines, dialogue hooks, unity, and the like. I also argued that, based on my analysis of many films from the 1910s to the 1990s, the vast majority of features followed a structure involving four large-scale parts, or acts–not three, as the popular Syd Field model would have it.

To do that, I analyzed the techniques of ten films usually considered to be models of unified, sophisticated narrative structure: Tootsie, Back to the Future, The Silence of the Lambs, Groundhog Day, Desperately Seeking Susan, Amadeus, The Hunt for Red October, Parenthood, Alien, and Hannah and Her Sisters.

The book was not intended to be a screenplay manual as such, though I know it has been used in some classes and by some aspiring screenwriters.

Ordinarily the press would have asked me to name some prominent film scholars who could be asked to write blurbs for the cover. It occurred to me, though, that it might be better in this case to take each chapter and send it to its director and to its main screenwriter and ask them for blurbs instead.

That turned out to work pretty well. Several didn’t answer, and other answered too late to be included. I ended up with three blurbs of which I am very proud, from Ted Tally for The Silence of the Lambs, Susan Seidelman for Desperately Seeking Susan, and from Harold Ramis for Groundhog Day.

Ramis’ recent death prompted me to dig out that old file. He had written back to my editor not with a sentence or two to use as a blurb, but with a page-and-a-half letter on the subject; it included a blurb down toward the bottom. It’s a letter that reflects how kind and smart Ramis was, and how much he had thought about writing and narrative–even though the process of writing screenplays was probably largely an intuitive one. It shows that he knew something about academic film studies, even if he had some “quibbles” with them. I certainly never meant to suggest that everything I pointed out in the films I analyzed was intended by the director and/or screenwriter. I would say that everything I pointed out was a result of their skill and experience. Even when something happens by accident during filming, someone has to decide whether or not to keep it in.

Rather than just sticking the letter back in the file, I thought I would share it with you. Having a little more of Ramis available can’t be a bad thing.

Dear Lindsay,

Thanks for sending the chapters of Kristin Thompson’s book Storytelling in the New Hollywood and please convey my thanks to Ms. Thompson for including Groundhog Day among the “modern classics.” My only quibble with scholarly film analysis is the occasional tendency to read more significance into certain details than was actually intended, or to think that certain accidents of production, on-set discoveries, or improvisational dialogues were planned and scripted. I realize, from a Deconstructionist point of view, it hardly matters what I think anyway, so let me set aside my minor quibbles and congratulate Ms. Thompson on her new book. If you would, please pass this letter along to her.

I am not a student of screenwriting so I’m afraid I can’t comment intelligently on Ms. Thompson’s theoretical model. Certainly, the fact that most movies are about two hours long will determine to a large extent the length of the set-up, the placement of the crisis, the climax, and the denouement, but rather than look at films in terms of “acts,” I prefer to think in terms of “actions,” as if the narrative line were a string of pearls, dramatically linked, each taking the audience forward to the next point. If any particular action doesn’t advance the plot or contain some new information, it doesn’t belong in the narrative. As a writer I generally proceed more intuitively than structurally. As Ms. Thompson suggests, I suspect that most of us have simply absorbed the classical film structure during our formative years as members of the audience.

When I was hired to write my first Hollywood screenplay, Animal House, the producer handed my collaborators and I paperback copies of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, and said, “This is what a good screenplay looks like. Just do that.” More than twenty years later, my only useful conclusion about structure is that nothing will work if you don’t have interesting characters and a good story to tell. One can argue for or against the three-action structure, but, whether or not there are consistent rules about the :well-made” screenplay, it’s already true that there are more well-constructed, formulaic screenplays than there are good ones. Also, one must always keep in mind that Hollywood films are almost invariably rewritten by additional (though not always credits) writers. One writer may be thought of as strong on structure, good for a solid first draft, another may be known for his dialogue, others for punching up action or comedy. Also , the Hollywood writer is always responding to script notes from studio executives, story departments, his producers, the director, and from his principal actors. In this convoluted and often tortured process, it’s sometimes impossible to attribute the final screenplay to the calculated intentions of one writer or team, and it’s often left up to a panel of Writers Guild arbiters to determine screen credit.

I didn’t intend to write such an inflated letter but there’s a lot to say on the subject and I have a considerable amount of experience.

If it’s useful to you, you may quote me as saying that Ms. Thompson’s insightful analysis of Groundhog Day and of the screenwriting process in general should be fascinating to both writers and audience alike. More thoughtful writing and more discerning audiences can’t help but lead to better movies, and this informative and provocative book is a step in that direction.

Best of luck on the publication of Storytelling in the New Hollywood and please feel free to contact me if you need any further comments.

Sincerely,

Harold Ramis

Harold Ramis as Allan “Crazy Legs” Hirschman (SCTV, “Indecent Exposure,” 1982).

Screenplaying

Design by Christina King.

DB and Kristin here:

Two years ago DB reported on the gathering in Brussels of the Screenwriting Research Network (here and here). This year, thanks to our colleagues J. J. Murphy and Kelley Conway, our department hosted the conference. Again, it was chock-a-block with stimulating papers. We also introduced our visitors to the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research, which houses thousands of screenplays. It wasn’t all work, either. Participants were spotted lingering at our lakeside terrace or making their way through the cafes and saloons lining State Street. We believe it’s fair to say that a hell of a time was had by all.

Since there were simultaneous sessions, nobody could attend everything, and we can’t run through all the papers we heard. (So do consult the program for more information.) Herewith, some highlights that set us thinking.

In the key of keynote

Larry Gross and Jon Raymond.

The four keynoters encapsulated the conference’s very wide range. In a workshop keynote Jill Nelmes, Editor of the Journal of Screenwriting, offered a historical survey of screenwriting research in all media, with special emphasis on television. The Big Hollywood Movie was covered by Kristin, whose paper, “Extended How?” examined the ways in which directors’ cuts and extended editions handle the multi-part structure she posits as a foundation of contemporary Hollywood. We won’t say more here, since she may turn it into a blog for this site.

Larry Gross had already started off the conference with a bang by taking us to Japan. Larry has written 48 HRS, Streets of Fire, Geronimo, True Crime, and other mainstream studio pictures, as well as television episodes, TV mini-series, and independent films like Prozac Nation and We Don’t Live Here Anymore. He also writes outstanding film criticism for Sight and Sound, Film Comment, and other journals, and he teaches screenwriting at New York University. Scott Macauley’s informative March interview with Larry is at Filmmaker Magazine.

Larry’s keynote, “The Watergate Theory of Screenwriting,” tackled the question of how filmmakers decide to share story information with the audience. What do the characters know and when do they know it? What does the audience know, and when? Storytelling, Larry suggested, develops out of the interplay of these two sets of questions. He added, perhaps hoping to provoke purists who consider film to be sheer self-expression: “Thinking about the audience is not always reactionary.”

Larry’s keynote, “The Watergate Theory of Screenwriting,” tackled the question of how filmmakers decide to share story information with the audience. What do the characters know and when do they know it? What does the audience know, and when? Storytelling, Larry suggested, develops out of the interplay of these two sets of questions. He added, perhaps hoping to provoke purists who consider film to be sheer self-expression: “Thinking about the audience is not always reactionary.”

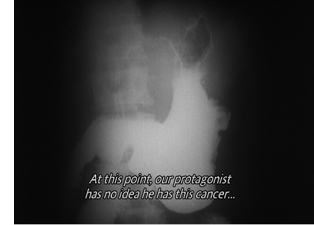

He illustrated his ideas with an in-depth examination of Kurosawa’s Ikiru. He had long thought the film “an official liberal-humanist classic,” until a course with Annette Michelson at NYU showed him that there was a lot to ponder there. Specifically, Kurosawa starts by telling the audience the end of the story: Watanabe will die of cancer. But he doesn’t know that, and neither do all the people he encounters. The strategy denies us a lot of suspense, so to hold our interest Kurosawa must engross us by delineating his relations with his colleagues, with the mothers petitioning for the neighborhood sump to be drained, and with the stray people he meets casually on his night out.

Larry showed how carefully Kurosawa played off the characters’ indifference, misunderstanding, and lack of awareness. In particular, the neighborhood wives display to Watanabe what Maurice Blanchot called “the ignorance and spontaneity of true affection.” Ikiru’s refusal to explain what it means typifies a kind of cinema that asks the audience to share the burden of understanding. “Ikiru understands how a screenplay can be composed with the audience.”

Jon Raymond’s keynote carried things to independent US film. Jon has become famous for a novel (The Half-Life) and short stories (Livability), as well as for his screenplays for Kelly Reichardt’s features. The most recent, the forthcoming Night Moves, is currently in competition at Venice. The teaser title of Jon’s address, “Screenwriting as Earth Art,” turned out to be a reference to the fact that most of his stories take place in the vicinity of his home. He has found satisfaction by composing on familiar ground.

In younger days Jon tried painting and filmmaking; a Public Access feature based on the comic strip Crock turned out to be “a movie best experienced in fast forward.” But he found that writing offered the most creative satisfaction. At the same time, while assisting Todd Haynes on Far from Heaven, he met Kelly Reichardt, who was looking for a property to adapt on a small budget. The result was Old Joy, “a New Age western,” in which two men display the violence latent in the new passive-aggressive masculinity flourishing on the Coast. Jon believes that Reichardt’s handling created a cinematic parallel to the dense intricacy of a short story.

In later collaborations, Jon mapped his patch of Portland in other ways. Seeing the annual migration of workers to Alaskan canneries, and hearing the train whistles wafting through his neighborhood, he created the story that became Reichardt’s Wendy and Lucy (above). Reichardt began adapting the story to film before he had finished writing it. Similarly, Jon merged the booming housing market of the 2000s and the history of the Oregon Trail into a project that paralleled today’s gentrification with nineteenth-century colonization. Reichardt turned his screenplay into Meek’s Cutoff, a “desert poem” that completed what some have called their Oregon Trilogy. For Jon, the trilogy constitutes an alternative regional history, one that traces the process of “sowing the land with failure, betrayal, and humiliation.”

Plots and no plots

The Adventures of André and Wally B (1984).

More than most areas of filmmaking, screenwriting reminds us of the institutional framework surrounding most creative work cinema. Scholars studying the screenplay are naturally often pursuing the endless revisions, refusals, and rethinks that a film goes through in the preparation phase. It’s easy to see this as a one-versus-one struggle, but in many cases the process takes place within a social environment possessing its own roles and rules.

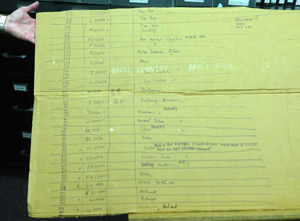

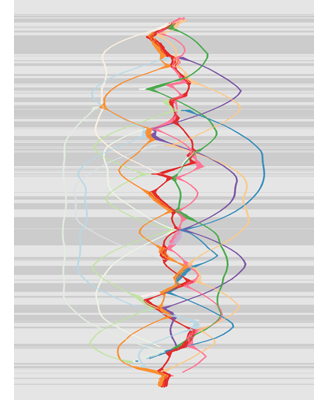

Ian MacDonald offered an excellent example in his study of the work processes behind the UK television soap opera Emmerdale. He proposed that we replace model of industrial film production as an auto factory with that of a carpet factory. Instead of the TV episode being seen as a discrete unit, like a car, it should be conceived as an ongoing fabric woven of many threads. In Emmerdale and other series, the unit of production isn’t the episode but rather the story line. Each episode is sliced out of a much bigger stretch of ongoing patterns. Ian illustrated this with the writers’ planning chart that was mounted on the wall.

The vertical column represents scenes, marked off as episodes. The characters are color-coded cards connected by solid liness that weave their way through the scenes. These waves are the melodies; the scenes are the bar-lines. In each episode, two or three characters are given prominence, while the subordinate ones contribute their harmonies. Ian’s discussion reminded me of how Hong Kong filmmakers did much the same thing in the 1980s: plotting films reel by reel and color-coding certain elements—gags, fights, and chases—to make sure that each reel had its share of attractions. This is the sort of insight into structure that institutional research can yield: Structure is these people’s business.

Other Hollywood studios envy Pixar for to its appealing, carefully structured stories. Richard Neupert showed how that tradition goes back to the earliest years at Pixar. Even in demo films which were made to show off technological innovations, the makers tried to reveal how computer animation, even in its early, simple form, could create engaging tales. At a period when computer animation could only render smooth, simple shapes, the Pixar team found appropriate subject matter, with highly stylized characters in The Adventures of André and Wally B and Luxo, Jr.

Remarkably, these tiny films have balanced “acts.” Each is 80 seconds long and has a key action at exactly 40 seconds in: the entrance of Wally B and the moment when the little Luxo lamp jumps on a ball. Similarly, Red’s Dream‘s parts run 50-100-50 seconds. This care in timing continued with the features: Toy Story’s midpoint comes when Woody finally shifts strategies, realizing he has to work with Buzz. And what about Pixar’s perceived slump in recent years? someone asked during the question session. Neupert pointed out that Pixar’s founders have aged, and there may no longer be quite the sense of excitement and discovery pushing the team to surpass others and themselves.

Sometimes institutional traditions come into conflict. Petr Szczepanik’s talk traced in meticulous detail how screenplay development in Czechoslovakia was altered in the years from 1930 to the 1950s. Czech filmmakers developed their own system of moving from theme and story germ to final screenplay. But with the Communist takeover there came the demand to add the Soviet model of the “literary screenplay,” a detailed specification of scenes, dialogue, and the like. Filmmakers resisted this, preferring the customary and more flexible “technical screenplay” that was largely the province of the director. Petr mentioned new screenwriting trends pioneered by Frank Daniel that gave directors the authority to modify the literary format. By the late 1950s, filmmakers had found ways to make the literary screenplay a less rigid blueprint for filming.

Back in the USSR, the screenwriting institution found even the literary screenplay a difficult basis for mass output. Maria Belodubrovskaya’s talk focused on “plotlessness” as a rallying cry and term of abuse in the 1930s-1940s Soviet film. There were long debates about whether “themes” sufficed to make a film or whether you needed strong plots in the Hollywood vein. Film-policy supervisor Boris Shumyatsky urged the latter course, and the popular success of Chapayev (1934) seemed to support his case. By the late 1930s, though, Shumyatsky was purged and the tide turned against strong plots. Film executives found a concern with plot too “Western” and “cosmopolitan,” and annual film production became based on themes rather than stories. Most provocatively, Masha suggested a lingering influence of Soviet Montage storytelling, which based films on vivid but loosely linked episodes. She illustrated her case with an analysis of Pudovkin’s In the Name of the Motherland (1943), with its diffuse lines of action and sudden reversals and omissions.

Back we go

Scarface (1932).

Naturally, Madison wouldn’t be Madison without strong papers on the history of cinema, and many conference presentations suited the tenor of the joint.

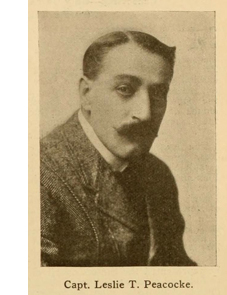

Stephen Curran offered an enlightening study of one of the least-known but most colorful figures in early American screenwriting, a man with the dashing name of Captain Leslie T. Peacocke. He was credited with over 300 screenplays, including Neptune’s Daughter (1914). He acted, directed, and wrote novels too. He was one of the first script gurus, writing magazine columns on the craft and eventually the early manual Hints on Photoplay Writing (1916).

Stephen Curran offered an enlightening study of one of the least-known but most colorful figures in early American screenwriting, a man with the dashing name of Captain Leslie T. Peacocke. He was credited with over 300 screenplays, including Neptune’s Daughter (1914). He acted, directed, and wrote novels too. He was one of the first script gurus, writing magazine columns on the craft and eventually the early manual Hints on Photoplay Writing (1916).

Stephen surveyed Peacocke’s contribution to the emerging scenario market. Peacocke believed that successful screenwriting couldn’t be taught, but he could give hints about developing original stories, thinking in visual terms, and practical craft maneuvers like snappy names for characters. During the Q & A, Stephen added that a great deal of Peacocke’s rhetoric was aiming to raise his own profile in the industry. In conversation afterward, Stephen praised the Media History Digital Library and Lantern (flagged in an earlier blog) for immensely helping research into early film. Here, for example, is Peacocke’s 216-item dossier on Lantern.

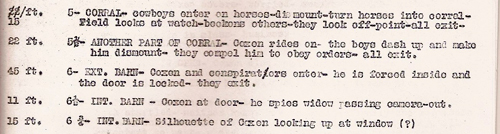

Andrea Comiskey argued that for the same period, we can study scripts and extrapolate craft practices that otherwise go undocumented. Her focus was the disparity between what manuals like Peacocke’s said and what actually got jotted down in working scenarios. Studying several screenplays from the American Film Company of Santa Barbara, she found that the manuals’ recommended stylistic approach was revised in the course of shooting.

The manuals proposed that each scene would be built out of a lengthy single shot (called, confusingly, a “scene”) which could at judicious moments be interrupted by an “insert.” An insert was usually a letter or piece of printed matter read by the characters, but it might also be a detail shot of a prop, hands, or an actor’s face.

In preparing scenarios, the writers assigned numbers to each “scene,” as the manuals recommended. But Andrea found that in the filming, the director and cameraman added shots, breaking down the action into more bits. This was, in effect, a move away from the strict scene/insert method and a shift toward what would become the classical continuity system. To maintain a paper record for the editor, the interpolated shots would be recorded and labeled in fractions. Instead of a straight cut from 6 to 7, the filmmakers might wedge in 6 ½, 6 ¾, and so on. Here’s an extract from Armed Intervention (1913), courtesy Andrea.

Strange as this sounds to us today, it was preferable to renumbering the shots, which could cause confusion. (Is shot 17 the original 17 or the later one?) The fractions kept the footage consistent with the scenario across the production process. So it turns out that (as usual?) filmmakers were a bit ahead of the screenplay gurus, even back in the 1910s.

Lea Jacobs asked a question about the transition from silent to sound film: How did filmmakers manage the pacing of dialogue? Silent movies had great freedom of pacing, while the shift to talkies seemed to many filmmakers to slow things down. Lea’s research indicated that two strategies for speeding things up emerged: creating shorter scenes and shortening dialogue passages within them. She reviewed how these ideas emerged in Hollywood’s own discourse in the 1930s and in certain films. In the first years of sound, scenes were rather long (often because they were derived from stage plays) and speeches were similarly extended. But in the 1931-1932 season, she argued, short scenes and quicker repartee became more common.

She traced the process in three films of Howard Hawks, from the stagy Dawn Patrol (1930) through The Criminal Code (1931), which opens in the new style but then turns to longer sequences, and then to Scarface (1932). The gangster film shifted toward shorter scenes and more laconic dialogue than did other genres, and Scarface displays this in full flower. Tony Camonte’s takeover of the South Side beer trade is presented in six harsh, violent scenes that add up to little more than three minutes. Workers in the sound cinema, it seems, were soon pushing toward that rapid tempo we identify with the 1930s.

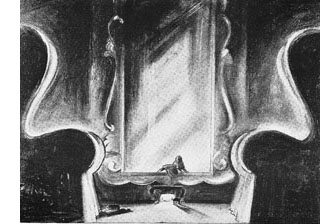

Storyboards have now entered academic studies. Chris Pallant and Steven Price offered some historical insights by comparing some early storyboards by William Cameron Menzie with those of early Spielberg films. When Menzies was storyboarding Gone with the Wind, he called it “a complete script in sketch form” and “a pre-cut picture.” Selznick’s publicity director characterized it: “The process might be called the ‘blue-printing’ in advance of a motion picture.” The striking revelation was that the storyboarding was not done after the script was finished. Menzies worked from the book, and the storyboard and script were created in parallel. Menzies’ storyboard for the 1933 Alice in Wonderland revealed a similarly elaborate process. It was 624 pages long, with one page per intended shot. Each page contained a sketch at the top, a paragraph describing the planned technological traits of the shot (such as lens length), and the traditional screenplay dialogue at the bottom. It’s hard to imagine many people other than a genius like Menzies being able to provide such a comprehensive plan for a film. (A sketch for Alice is on the right here. DB has written about Menzies here and here.)

Storyboards have now entered academic studies. Chris Pallant and Steven Price offered some historical insights by comparing some early storyboards by William Cameron Menzie with those of early Spielberg films. When Menzies was storyboarding Gone with the Wind, he called it “a complete script in sketch form” and “a pre-cut picture.” Selznick’s publicity director characterized it: “The process might be called the ‘blue-printing’ in advance of a motion picture.” The striking revelation was that the storyboarding was not done after the script was finished. Menzies worked from the book, and the storyboard and script were created in parallel. Menzies’ storyboard for the 1933 Alice in Wonderland revealed a similarly elaborate process. It was 624 pages long, with one page per intended shot. Each page contained a sketch at the top, a paragraph describing the planned technological traits of the shot (such as lens length), and the traditional screenplay dialogue at the bottom. It’s hard to imagine many people other than a genius like Menzies being able to provide such a comprehensive plan for a film. (A sketch for Alice is on the right here. DB has written about Menzies here and here.)

Spielberg used sketches in addition to a screenplay from the start. Duel, surprisingly enough, was supposed to be shot in a studio, but the director insisted on working on location. The sketches he made for it do not resemble a traditional storyboard but instead are like pictorial maps framed from an extremely high angle. He also plotted out the paths of the vehicles with overhead views of the roads. The storyboards for Jaws were done from the novel at the same time that the script was being written, just as Menzies had done with Gone with the Wind. (The same thing happened with Jurassic Park.) Storyboards were vital, among other things, for telling the crew which of the four versions of the shark would be used. One fake shark had only a right side, another a left, and which one was needed depended on the direction the shark was crossing the screen. The speakers distinguished between the “working” storyboard and the “public” one. The public one is what sometimes get published, but it usually has each image cropped to remove the information about the shot (e.g., who will work on it) noted underneath.

Brad Schauer contributed to a roundtable on the American B film back when The Blog was in its infancy. He has been researching the role of B’s in the industry for many years, and he brought to our event some new ideas about them in the postwar period. His paper, “First-Run and Cut-Rate” showed that there were still plenty of theatres showing double bills in the 1950s and 1960s (DB can confirm it), and the market needed solid, 70-90 minute fillers. One answer was the “programmer,” or the “shaky A” that featured somewhat well-known talent, color, location shooting, and familiar genres (Westerns, swashbucklers, horror, crime, comedy, and science fiction). Shot in half the time of an A, with budgets in the $500,000-$750,000 range, programmers fleshed out double bills and sometimes broke into the A market.

What does this have to do with screenwriting? Brad decided to test whether Kristin’s ideas about four-part structure (here and here) held good with programmers. Looking at several, he came up with a plausible account that films like Battle at Apache Pass and Against All Flags simply compressed the four parts into short chunks, typically running fifteen to twenty minutes. In The Golden Blade, Rock Hudson formulates his goal (revenge) two and a half minutes into the movie.

Too few things happen?

La Pointe Courte (1955).

In most films, Agnes Varda said, “I find that too many things happen.” How can screenplay studies move beyond Hollywood’s jammed dramaturgy to consider the more spacious sort of storytelling we find in “art cinema”?

Colin Burnett offered a general overview of art-cinema norms that is somewhat parallel to our and Janet Staiger’s The Classical Hollywood Cinema. To a great extent, of course, “art films” differ from classically constructed films. They can be more ambiguous, more reflexive, more stylized and at the same time more naturalistic. They often replace a tight causal chain with episodic construction and nuances of characterization. The protagonists may have complex mental states; they may have inconsistent goals, or no goals at all; they may be passive; they may have shifting identities.

Yet Colin argued against claims that art films lack narrative altogether. “Art films offer reduced scene dramaturgy, rarely its complete absence.” They possess structuring devices comparable to Hollywood acts. A film’s large-scale parts may be based on a character’s development, on changes in space or time, or on variations of action and/or reaction. A question was raised as to whether such a broad category as art cinema could be characterized in such ways. Given the enormous range of types of films made in the Hollywood tradition, however, it seems possible that the art cinema could be described in a similar fashion. (For our thoughts on the matter, go here and here.)

A great many art-film strategies can be seen as stemming from modernism in literature and the other arts. As if offering a case study illustrating Colin’s argument, Kelley Conway focused on La Pointe Courte. Varda’s first film is now coming to be considered the earliest New Wave feature. But Varda wasn’t the prototypical New Waver. She wasn’t a man, she wasn’t a cinephile, and she took her inspiration from high art, not popular culture. A professional photographer who loved painting and literature, she brought to this film (made at age 26) a bold awareness of twentieth-century modernism. The result was a striking juxtaposition of stylization and realism, personal drama and community routine. In La Pointe Courte, we might say, neorealism meets the second half of Hiroshima mon amour.

Inspired by Faulkner’s Wild Palms, Varda braided together two stories. While families in a fishing village live their everyday lives, an educated couple work through their marriage problems in a long walk. Remarkably, Varda had not seen Rossellini’s Voyage to Italy. After supplying background on the production process, Kelley focused on matters of performance. She explained how Varda, well aware of Brechtian “distanciation,” made the couple’s dialogue deliberately flat. By contrast, the villagers’ lines, through scripted, were treated more naturalistically. La Pointe Courte emerges as an anomie-drenched demonstration of how little you need to make an engrossing movie.

To script or not to script (or to pretend not to script)

Maidstone (1970).

The SRN embraces research into the absence of a script as well. At one limit is the work of avant-gardists like Stan Brakhage. John Powers’ “A Pony, Not to Be Ridden” discussed how non-narrative filmmakers used paper and pencil to organize their work, much as a poet might make notes on a draft. John’s examples were three films by Brakhage, each developed out of sketches and jottings assembled after shooting but before editing. Unconstrained by any script format, Brakhage had to invent his own version of storyboarding and screenplay notes.

Compilation filmmakers also discover their structure in the process of collecting and sifting material. Documentarist Emile de Antonio, whose collection resides in our WCFTR, had to build his screenplay up after he had assembled some material. “A script won’t be ready,” he remarked, “until the film is finished.” Vance Kepley’s paper showed that In the Year of the Pig was the result of a massive effort of “information management.” De Antonio sought out press clippings, sound recordings, and news footage and then had to create an archive with its own system of labeling, cross-references, and easy access.

De Antonio started with the soundtrack, which was itself a montage of found material, and then created a “paper film,” cutting and pasting vocal passages and descriptions of images. At the limit, he charted his film’s structure with magic-marker notations on large strips of corrugated cardboard, as Vance illustrated.

One panel session took a close look at improvisation in fiction features. Line Langebek and Spencer Parsons gave a lively paper with the innocuous title “Cassavetes’ Screenwriting Practice.” Explaining that Cassavetes did use scripts (“sometimes overwritten”), and he relied on actors to help create them in workshop sessions, they proposed thinking of his work as exemplifying the “spacious screenplay.” Their ten principles characterizing this sort of construction include:

Write with specific actors in mind. Use a “situational” dramaturgy rather than a rise-and-fall one. The work is modeled on free jazz, with moments set aside for specific actors. Even minor actors get their solos. Shoot in sequence, so that emotional development can be modulated across the performances.

Line and Spencer’s precise discussions cast a lot of light on the specific nature of Cassavetes’ creative process and pointed paths for other directors. They added that the spacious screenplay is really for the actors and the director; the financiers should be given something more traditional.

Norman Mailer called Cassavetes’ films “semi-improvised.” He tried to go further, J. J. Murphy explained in “Cinema as Provocation.” Mailer wanted his three films Wild 90, Beyond the Law, and Maidstone to be completely improvised, utterly in the moment. “The moment,” he proclaimed, “is a mystery.” Mailer opposed the “femininity” he claimed to find in Warhol’s films, so he encouraged his male players to indulge their machismo playing gangsters, cops, and aggressive entrepreneurs. J. J., whose book on Warhol stressed the psychodrama component of the films, finds Mailer no less devoted to having his players work out their problems through unrestrained behavior. The climax of Maidstone, in which an enraged Rip Torn begins to strangle Mailer, becomes the logical outcome of Mailer’s needling provocation of his actors. How ya like the mystery of this moment, Norman?

Within the Hollywood industry, improvisation is identified strongly with Robert Altman’s films, but Mark Minnett‘s “Altman Unscripted?” shows another side to his work. Focusing on The Long Goodbye, Mark finds that the film doesn’t vary wildly from the script. The principle plot arcs aren’t changed, although Altman decorates them by letting minor characters inject some novelty. He encouraged the guard who does impressions of Hollywood stars, and he gave latitude to Elliott Gould, whose improvisation elaborates on the issues of trust and bonding that are embedded in the script. Some scenes are condensed or altered, as often happens on any production, but the Altman mystique of freewheeling, anything-goes creativity isn’t borne out by the film. Altman’s characteristic touches are built around what’s “narratively essential,” as laid out in the screenplay.

We learned a lot more at the conference than we can cover here. For example, Jule Selbo brought to our attention Sakane Tazuko, a woman screenwriter-director in 1930s Japan. Rosamund Davies explored the ways in which transmedia storytelling could enhance historical dramas. Carmen Sofia Brenes traced out how different senses of verisimilitude in Aristotle’s Poetics might apply to screenwriting. We learned of a planned encyclopedia of screenwriting edited by Paolo Russo and a book on the history of American screenwriting edited by Andy Horton. Not least, there was Eric Hoyt, whose “From Narrative to Nodes” showed how digitized screenplays could be used to graph character action and interaction over time. (A nice moment: When asked if his analytic could be rendered in real time, he clicked a button, and the thing moved.) Once more we’re in the x-y axes of Emmerdale and In the Year of the Pig, but now in cyberspace. Eric’s results on Kasdan’s Grand Canyon appears here on the right, but only as an enigmatic tease; he will be contributing a guest blog here later this fall.

In other words, you should have been here. Next time: October in Potsdam, under the auspices of Kerstin Stutterheim at the Hochshule für Film und Fernsehen “Konrad Wolf.” DB was at this magnificent facility last year for another event, and we’re sure–to coin a phrase–a hell of a time will be had by all.

Thanks very much to J. J. and Kelley, as well as to Vance Kepley, Mary Huelsbeck, and Maxine Fleckner Ducey of the WCFTR. Special thanks to Erik Gunneson, Mike King, Linda Lucey, Jason Quist, Janice Richard, Peter Sengstock, Michael Trevis, and all the other departmental staff that helped make this conference a big success.

Thanks also to Noah Ollendick, age 12, who asked a smart question.

P.S. 4 Sept: Thanks to Ben Brewster for a correction!

J.J. Murphy and Kelley Conway, conference coordinators.

Industrial strength

Edith Head costume sketch for To Catch a Thief. From Edith & Oscar: A Costume Exhibit, WCFTR website.

DB here:

Until the 1970s, academics interested in film seldom paid close attention to Hollywood as an industry. Some economists and historians of law were beguiled by the sight of an oligopoly eventually dismantled by Supreme Court decree. But these scholars weren’t particularly interested in the products of the studio system.

People interested in the movies took three positions. The most dogmatic, voiced by one of my grad-school professors, ran this way: “Money doesn’t matter.” That is, art will always triumph over business. If a movie is good, the circumstances of its making are irrelevant. And we study only good movies, so we needn’t consider the business.

Another view acknowledged the importance of the industry but saw it as a vague, overarching force. Creative artists were seduced by it or struggled against it. A powerful director like Chaplin or Hitchcock could control his work to a considerable degree. For the less powerful, the studios (along with censorship agencies) were barriers to creative work. They forced directors to bow to the demands of moguls or a debased public.

The third view was largely celebratory. The studios represented a wondrous confluence of talent at every level, from script to music, and the System mysteriously spun out marvels of drama, comedy, and spectacle: Hollywood as Gollywood. Researchers in this tradition ferreted out as much information as they could about the old days, infusing encyclopedic ambitions with fan enthusiasm.

What came to be called “Wisconsin revisionism” or “the Wisconsin Project” proposed some alternatives.

Auteurist in the archive

Corner of WCFTR office area. Photo: Mary Huelsbeck.

When I came to UW–Madison to teach in 1973, I was an auteurist with a taste both for Hollywood and foreign cinema. I knew relatively little about how the studio system functioned. Its machinations were simply factored out of my consideration. Directors, from Hitchcock and Hawks to Dreyer and Mizoguchi, were what loomed in my consciousness, and I wanted to spend my life studying what they had accomplished.

But contact with students, faculty, and campus personalities at Madison changed my thinking. There was The Velvet Light Trap, a defiantly unofficial magazine that ran special issues on all manner of non-auteur subjects, especially studios, periods, and genres. There were ambitious film societies like Fertile Valley and the Green Lantern, showing offbeat items. There were smart, well-informed grad students. There was the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research, which housed thousands of prints, the center of my lustful thoughts both day and night. The WCFTR also housed vast archives of papers, scripts, photos, and other documents of Hollywood’s golden era.

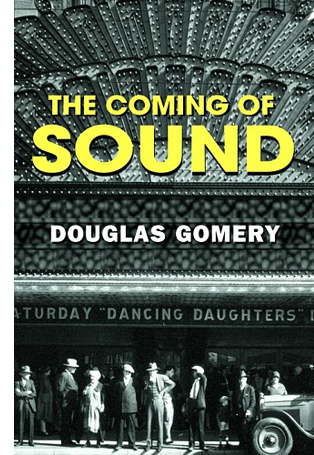

Then there were Professor Tino Balio and Dissertator Douglas Gomery. My conversations with them, both in and out of the office, showed me that there were fruitful questions to be asked about the nature and conduct of the studio system. These two scholars, I think, more or less invented the rigorous historical study of Hollywood as a business enterprise.

Take Doug’s dissertation (and subsequent book). How did Warner Bros. innovate sound? Was Warners, as most accounts claimed, a threatened company, desperately driven to try a new technology to stave off bankruptcy? Doug answered the question in a revelatory way: The evidence pointed to Warners’ innovation of sound as a carefully calculated business decision made by a company that had already explored the technology and the market. In fact, WB was not going bankrupt, it was actually expanding into other domains, including radio. By using a traditional historical model of technological diffusion, Doug made the Warners’ decision intelligible. He served as a TA in my first course at Wisconsin, and our friendship proved to be a case of the student teaching the teacher.

Take Doug’s dissertation (and subsequent book). How did Warner Bros. innovate sound? Was Warners, as most accounts claimed, a threatened company, desperately driven to try a new technology to stave off bankruptcy? Doug answered the question in a revelatory way: The evidence pointed to Warners’ innovation of sound as a carefully calculated business decision made by a company that had already explored the technology and the market. In fact, WB was not going bankrupt, it was actually expanding into other domains, including radio. By using a traditional historical model of technological diffusion, Doug made the Warners’ decision intelligible. He served as a TA in my first course at Wisconsin, and our friendship proved to be a case of the student teaching the teacher.

Tino, who was presiding over the WCFTR, became another premiere scholar of filmmaking as a business. His books, anthologies, and book series brought immense attention to our collection of material on United Artists, Warner Bros., and RKO. He taught courses in the history of the industry, both survey courses and in-depth seminars. I think I learned more sitting on examination committees with him than I had in many of my grad-school lectures.

Many of the research questions asked by Tino, Doug, and their peers didn’t concern the movies themselves. Some did, though. I remember Cathy Root’s study of stars as strategies of “product differentiation.” More broadly, in the 1970s and early 1980s, some of us suspected that the Hollywood system of production, distribution, and exhibition could affect what then was called “the film text.”

As a result, Kristin, Janet Staiger, and I tried to show how Hollywood’s mode of production did more than simply limit gifted artists or yield pop-culture diversions. In The Classical Hollywood Cinema (1985), we tried to understand how the organization of production shaped work routines, technology, adjacent institutions, conceptions of quality, and other factors that did impinge on how the films looked and sounded. Over the years these aspects of filmmaking practice took off on their own, becoming somewhat detached from the industrial conditions that created them. When the studio system faded away in its classic form, the community’s notions of narrative construction, stylistic expression, professional practices, and other factors hung on. The economics changed, but the aesthetics persisted.

Now there are many people working to show how industrial factors interact with filmmakers’ creative choices. Kristin and I have continued these explorations in books and blog entries, extending them to other periods (e.g., the 1910s, the New Hollywood, the 1940s). I like to think that much of our work over the last decades has tried to blend the careful empirical and explanatory work of Tino, Doug, and others with the analysis of art and craft typical of film criticism. We can ask some questions that cut across the over-simple Art/Industry split.

Let a thousand projects bloom (motto, People’s Republic of Madison)

This exercise in autobiography was triggered by some recent events. One is the spiffy new website for the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research. Under its recent director Michele Hilmes and current director Vance Kepley, the Center has gotten a new jolt of energy. It’s promoting its vast collections in an attractive way and is starting to spotlight some that weren’t well-known. The selections are bolstered by informative program notes by Maria Belodubrovskaya, Booth Wilson, and others.

Certainly the Center’s heart, for historians of Hollywood, is the United Artists collection. This assembles United Artists business records from 1919-1965, scripts and stills from Warner Bros. and RKO, and several thousand film features, shorts, and cartoons, mostly from 1928 to 1948. Then there are the hundreds of named collections, provided by individual donors. The refurbished website calls attention to several of them: the personal and business correspondence of Kirk Douglas (some items now digitized), the Blacklist collection (six of the Hollywood Ten represented), the dazzling array of Edith Head’s costume designs (okay, I’m going a bit Gollywood). There are records for Otto Preminger, Walter Wanger (the basis of Matthew Bernstein’s biography), and Shirley Clarke. The restored Portrait of Jason was discovered in her collection.

Lately, needing information on Guest in the House (1944), I turned to the WCFTR screenplay by Ketti Frings. Her name looks like a Scrabble hand, but she turns out to be a fairly significant screenwriter, contributor to The Bells of St. Mary’s (1945), Dark City (1951), and By Love Possessed (1961). Some other day I must get around to prowling in the papers of Vera Caspary, an extraordinary person who is far more than the author of Laura (though I’d be happy just being that).

Beyond Hollywood, the Center holds major collections of Russian cinema and, more recently Taiwanese cinema. And if you must leave cinema behind for theatre, you can investigate Eugene O’Neill, George S. Kaufman, and many other luminaries. In sum, a resource to make you happy for decades.

A career and a conference

The expansion of the Center owes everything to Tino Balio, who served as director in its crucial years. It was he who acquired the UA treasures and many of the named collections. Access to the UA papers enabled him to write the definitive history of the company, but it also created a huge spillover effect: dozens of research projects were nourished by his pursuit of this collection—which came to us at a time when virtually no universities, not even those in LA, were seeking Hollywood corporate records.

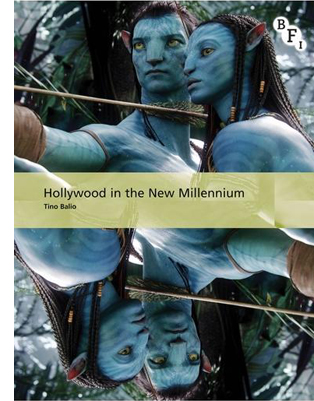

So it’s fitting that, as the WCFTR redesigns its public profile, we see the publication of Tino’s Hollywood in the New Millennium.

In a sense it’s a sequel to his earlier books, The American Film Industry (1976, 1985) and Hollywood in the Age of Television (1990). But these were anthologies, whereas this is through-composed. It’s most like his magisterial survey of the business strategies behind the art-film explosion, The Foreign Film Renaissance on American Screens, 1946-1973 (2010): a careful study of a remarkable period in US film history.

In a sense it’s a sequel to his earlier books, The American Film Industry (1976, 1985) and Hollywood in the Age of Television (1990). But these were anthologies, whereas this is through-composed. It’s most like his magisterial survey of the business strategies behind the art-film explosion, The Foreign Film Renaissance on American Screens, 1946-1973 (2010): a careful study of a remarkable period in US film history.

Hollywood in the New Millennium charts the trends that characterize the last fifteen or so years of the American film industry. It surveys financing, production, distribution, exhibition, ancillary markets, and the independent realm. Tino analyzes the ways in which new technologies have changed all these areas, mostly to the benefit of the bottom line, but he also recognizes that technology can undermine the business, especially in the hands of what he calls “the I-want-it-for-free consumer.”

He surveys studio policies, attempts at synergy, and viral marketing. He traces the rise and fall of executives and is especially strong on the emergence of the overriding strategy of the tentpole picture aimed at teenagers and families. Since all studios belonged to entertainment conglomerates, the constant demand was for large-scale profits. For all its financial excesses, the tentpole strategy, Tino argues counterintuively, was an austerity measure.

By the decade’s end, every studio was in the tentpole business. Although the costs of producing and marketing such pictures were enormous, they were the only types that could perform on a global scale and generate significant returns. . . . The sure thing was a good hedge against a dying DVD business, the fragmentation of the audience, and the unknown impact of the internet and social media on Hollywood marketing practices.

In short, you could not ask for a more concise, reliable map of where Hollywood is today. The bibliography is expansive enough to inspire other researchers to dig into both printed and online sources.

Tino has exercised a remarkable influence on two generations of film scholars, but in an almost surreptitious way. Now every film student learns about the structure and conduct of the film industry, but few know that Tino played a pivotal role in making this sort of knowledge central to academic film study. Now in his mid-seventies, Tino has left a peerless legacy of research.

Speaking of research, our campus will be hosting a major conference that includes the WCFTR as a key component. The Screenwriting Research Network International is holding its annual gathering here on 20-22 August. I attended the Brussels SRNI conference two years ago and wrote about it here and here. I think it’s fair to say that a hell of a time was had by all. This is a stimulating bunch, and anyone interested in filmmaking would benefit from attending.

Keynote speakers this year are Larry Gross (48 Hrs, True Crime, We Don’t Live Here Anymore, Veronika Decides to Die), Jon Raymond (Old Joy, Wendy and Lucy, Meeks Cutoff , and several novels), and. . . Kristin!

Keynote speakers this year are Larry Gross (48 Hrs, True Crime, We Don’t Live Here Anymore, Veronika Decides to Die), Jon Raymond (Old Joy, Wendy and Lucy, Meeks Cutoff , and several novels), and. . . Kristin!

The scholars are no less stellar and include Kathryn Millard, Richard Neupert, Jill Nelmes, Steven Maras, Riikka Pelo, Eva Novrup Redvall, Nate Kohn, Ronald Geerts, Andy Horton, Ian Macdonald, and a great many more. Go here for a complete program. You will be impressed.

Needless to say, among the guests are many UW alumni: Patrick Keating, Colin Burnett, Maria Belodubrovskaya (currently a faculty member too), Brad Schauer, Mark Minett, Mary Beth Haralovich, and David Resha. All of them have been steeped in archival research, centrally at WCFTR. Also home-grown are the conference organizers, J. J. Murphy (who blogs here) and Kelley Conway, who is finishing her book on Agnès Varda after immersion in that great lady’s personal archive. Another faculty member, Eric Hoyt, is curator of the remarkably full and free Media History Digital Library; expect him to divulge newer-than-new research sources and methods. I’ll crowd into the act with a paper tied to my 1940s book.

All in all, I see a pleasing continuity from my salad days, through forty years of teaching and viewing and writing, to this moment: a new Balio book, a sparkling shop window for the Center, and new generations of researchers eager to show that The Industry and The Art of Cinema aren’t always that far apart.

Earlier memoirs of Mad City culture in the 1970s-80s are here and here.

For more on the origins of Wisconsin revisionism, see my introduction to Douglas Gomery, Shared Pleasures: A History of Movie Presentation in the United States (University of Wisconsin Press, 1992) and this entry. We have a blog entry on Tino’s Foreign Film Renaissance on American Screens here.

On the remarkable Vera Caspary (Wisconsin’s own) see not only her fine thrillers Laura and Bedelia but also her Bohemian autobiography The Secrets of Grown-Ups (McGraw-Hill, 1979).

Thanks to Steve Jarchow, CEO of Here Media and Regent Entertainment, for his many years of support of the WCFTR’s activities.

Kelley Conway, Tino Balio, and Lea Jacobs; Madison, WI September 2011.