Archive for the 'Screenwriting' Category

Scriptography

Hollywood screenwriters at work, according to Boy Meets Girl (1938).

It’s not every conference that opens a morning session by asking the men in the audience to take off their underwear.

But I anticipate.

Last weekend I was a guest of the Screenwriting Resource Network’s fourth annual Screenwriting Research Conference in Brussels. I think that a hell of a time was had by all, and I learned quite a bit, including some reasons why people are interested in screenplays.

Schmucks with Underwoods

Catherine Turney script for No Man of Her Own (1950).

In my youth, there seemed to be a solemn pact among my peers that we would never study certain areas: censorship, audiences, adaptation (novels into film, particularly), and screenwriting. An earlier generation had, through patient labor, shown decisively that these subjects were dead boring. We, on the other hand, were fired by notions of the director as auteur, and indifferent to what were called “literary” and “sociological” approaches to film. So we triumphantly turned toward The Text—that is, the finished movie.

Things have changed since then. Yet there are still tempting reasons to consider the study of screenwriting a nonstarter if you’re interested in cinema as an art. If you think of the finished film as the achieved artwork, then study of screenplay drafts risks seeming irrelevant. Whatever the screenwriter(s) intended seems irrelevant to the result. So what if six or more screenwriters labored over Tootsie? The movie stands or falls by what we see onscreen.

This was the view presented in Jean-Claude Carrière’s three talks to our group. He suggested that the screenplay is destined to become landfill, and rightly so. It’s like the caterpillar that becomes a butterfly. Once the film has been made, the script has no intrinsic value.

Someone might say, “Wait! We study a painter’s sketches, a novelist’s drafts, or a composer’s early scores. These materials can contribute to understanding the finished work, and sometimes they have an artistic value of their own.” The problem is that in these arts, the preparatory materials are in the same medium as the result. But a script can’t count as a version of the film because prose can’t adequately specify the audiovisual texture of a movie. It’s commonly thought, plausibly, that giving the same script to two directors would result in significantly different films. So the script is at best a series of suggestions for filming, not a sketchy version of the movie. Why not discard it when the film is done?

The study of screenwriting has probably also lain in the shadows because of the proliferation of screenwriting gurus and how-to manuals. Every American over the age of eighteen seems to be writing a screenplay; the Cable Guy who visited me last week was working on two. So all the seminars and advice books have arguably put thinking about screenplays rather close to the amateur-script racket.

Moreover, screenplay studies seem to be part of a broader, paradoxical development in academic film studies. Today scholars have more access to films than ever before, thanks to video, festivals, archives, and the internet. Yet many researchers prefer to talk about everything but the film. More and more scholars want to study just those subjects that my cohort considered dull or irrelevant: censorship and regulation, audiences (composition, demographics, critical reception, fandom), and preproduction factors (storyboards, scripts). In addition, many academics have turned to bigger thematic ideas like film and architecture, film and the city, film and modernity. These trends of research usually make only glancing reference to actual movies, mostly mining them for quick illustrative examples.

In sum, many academics have abandoned the study of film as an artistic medium that finds its embodiment in important works. To get to know particular films more intimately, you increasingly have to go to the Net, to writers like Jim Emerson, Adrian Martin, and other sensitive analytical critics. Talking about screenwriting can seem to be another way of avoiding coming to grips with the intrinsic power of movies.

You can probably tell that one side of me shares some of the biases I’ve listed. But when I remind myself that what people should study aren’t topics but questions, I cheer up quite a bit. For there are, I think, worthwhile questions to be asked about all these areas, screenwriting included. The Brussels event gave some good instances of resourceful, occasionally exciting research into them.

Based on my short acquaintance, most of the research questions seem trained on one of two broad areas: Screenwriting and The Screenplay.

In the trenches

Kinky & Cosy

Screenwriting can be thought of as a practice, a creative activity with both personal and social aspects. How, we might ask, do screenwriters or directors express themselves in the script? How does a media industry recruit, sustain, and reward screenwriters? What are the conventions and constraints at work in a particular screenwriting community?

Questions like this are somewhat familiar to me. When I wrote my first book, on Carl Dreyer, I had to examine his scripts (notably the unproduced Jesus of Nazareth), and that helped me understand his characteristic methods of researching and planning his films. Later, when I collaborated with Kristin and Janet Staiger on The Classical Hollywood Cinema, I recognized a more institutional side of things. We can see from the films of the 1910s that filmmakers were cutting up the space in fresh ways. But this wasn’t a matter of directors simply winging it on the set. Kristin used published manuals and Janet used original screenplays to show that shot breakdowns were planned to a considerable degree before shooting. This habit made production more efficient and controllable.

At the Brussels get-together, Steven Price offered further evidence of this sort, which displayed some of his research on early scenarios for Mack Sennett movies like Crooked to the End (1915). Interestingly, Steven found that sometimes the later version of a continuity script was more laconic than the initial one. Perhaps the gags, once spelled out in the first draft, could be left up to the actors. This is the sort of thing he identified as a “trace” of production practices.

A parallel of sorts emerged in Maria Belodubrovskaya’s paper on screenwriting under Stalin. The Soviets, admiring Hollywood efficiency, tried to come up with a similar system. But their efforts to produce films in bulk were blocked by a censorship apparatus bent on ideological correctness. No surprise there, I guess. But Masha showed convincingly that the very efforts to mimic Hollywood’s “assembly-line” system also discouraged authors from submitting scripts. The writers thought (like many of their LA counterparts) that such a setup denied them creative freedom. In addition, the prospect of story departments providing a stream of screenplays ran afoul of the tradition that gave the director control of the final draft. And the role of producer, as one who could steer the whole process, didn’t exist! So much for the Soviet Hollywood.

What about other media? Sara Zanatta traced out the process of creating Italian TV series. She reviewed some major formats (miniseries, original series, adaptations of foreign series) and then took us through the process of creating individual episodes. Interestingly, it seems that the Italian system, unlike US television, makes the director the boss of it all. Frédéric Zeimat explained how he gained entry to the local screenwriting community through his university education, including work in Luc Dardennes’ workshop at the Free University of Brussels. Eventually he came up with a script that won prizes. He is about to become a showrunner for a sitcom.

One of the most stimulating panels I heard considered the writing of graphic novels and animation. Richard Neupert explored how recent French animation sustained the tradition of individual authorship while still acceding to some international norms of moviemaking. The cartoonist Nix discussed how he faced new problems in transferring his three-panel comic strip Kinky & Cosy from print to television. TV demanded less written text, especially signs, so that the clips could be exported outside Belgium. More deeply, Nix had to rethink how to pace the action and leave a beat (say, two seconds) after the punchline.

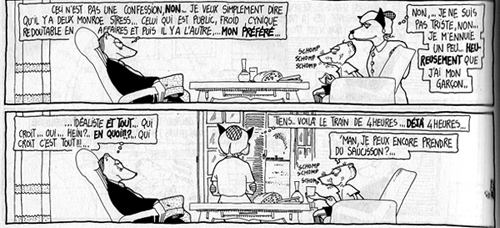

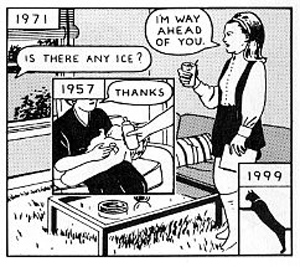

Pascal Lefèvre, one of Europe’s leading experts on comic art, provided a brisk, packed account of the history and practices of scriptwriting for Eurocomics. He described patterns of collaboration, format, and creative choice, placing special emphasis on comics as a spatial art different from cinema. His example was a page from Regis Franc’s ulta-widescreen album Le Café de la plage. Here’s a portion in which two periods of Monroe Stress’s life coexist in a single space. He muses as an adult while his childish self gobbles up food under the guidance of Mom.

Comics space can also change abruptly, as when a window appears in second panel.

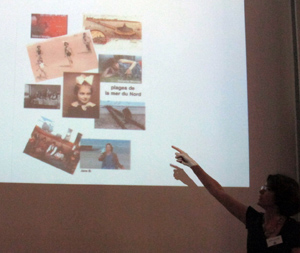

Other papers presented less institutionally fixed, more personal versions of screenwriting as a practice. Kelley Conway’s lecture on Agnes Varda exploited unique access to the filmmaker’s notebooks, scrapbooks, and databases. Kelley showed how Varda conceived three of her documentaries by means of strict categorical structures that were then frayed by digressions born out of the material she shot.

Anna Sofia Rossholm provided something similar for Bergman. Out of the vast Bergman archive she quarried sixty “workbooks,” typically one for each film. Whereas Varda’s books were filled with cutouts and images, Bergman was a word man, treating the books as diaries that recorded “this secret I.” Anna Sofia proposed that in his jottings and planning, Bergman not only communed with himself (calling himself an idiot on occasion) but also explored patterns of doubling akin to those we find in the films. The workbooks evidently held a special place for him: he included their pages in films like Hour of the Wolf and Saraband.

David Lean might be thought of as working in between the Hollywood system and the more personal European milieu. Ian Macdonald suggested that one of Lean’s unfilmed projects sheds light on what he calls screenplay poetics. Macdonald seeks, I think, a principled method for studying the creative process. He does this by tracing how a screen idea is transformed in a series of documents generated by the creative team. The process, he points out, is governed by the participants’ various conceptual frameworks. For Nostromo, Lean solicited two screenwriters and oversaw their rather different versions of the novel. Ian showed that Lean seems to have found solutions to adapting the book by fitting it to the three-act structure advocated by Hollywood artisans, a concrete case of a filmmaker accepting a fresh “poetics” or set of creative constraints.

All of these inquiries could lead to more general thoughts about the creative process in cinema. For some filmmakers, it’s a professional task, undertaken with full knowledge that problems and constraints will have to be dealt with. For others, such as Bergman and Varda, it’s obviously deeply personal, even autobiographical. Perhaps most intimate was the film discussed by Hester Joyce. New Zealand filmmaker Gaylene Preston based Home by Christmas (2010; above) partly on audiotape interviews with her father as he recalled his World War II experiences. Her script reconstructed her interviews with actors, then filled in scenes with documentary footage and scenes she imagined. It’s a family memoir on several levels: Preston’s daughter portrays her own grandmother.

The Screenplay: What is it?

Several of these probes into the creative process raise a more theoretical question. How should we best conceive of the screenplay? As a blueprint? A recipe? An outline? These labels all suggest something disposable preliminary to the real thing, the movie. But why can’t we think of the screenplay as a freestanding object? After all, there are films without screenplays, but there are also screenplays—some written by distinguished authors—that were never made into films. And some of these, like Pinter’s Proust screenplay, are read for their own sake.

In cases like this, should we consider the screenplay a literary genre? And if the screenplay for an unproduced film can be considered a discrete object, what stops us from treating a filmed script in exactly the same way? Moreover, why even speak of a single screenplay, when we know that most commercial films at least go through several drafts? Can’t we consider each one an independent literary text? We’re now far from Carrière’s idea that the script finds its consummation in the finished film and as a piece of writing it should wind up in the ashcan.

And not all screenplays are literary texts. The scrapbooks and databases that Varda accumulates are works of visual art, collages or mixed-media assemblages. Are these merely drafts of the film, or do they have an independent existence or value? We seem to be asking the sort of question that Ted Nannicelli poses in his Ph. D. dissertation. Is there an ontology of the screenplay?

Take a concrete example. Ann Igelstrom’s paper, “Narration in the Screenplay Text,” asked how literary techniques are deployed in the screenplay. When a passage in the script for Before Sunset begins, “We see…,” who exactly is this we? Ann argued that traditional narrative concepts involving the source of the narration, the implied author and implied reader, and the rhetoric of telling can illuminate conventions of screenwriting. Here the screenplay seems definitely a literary text.

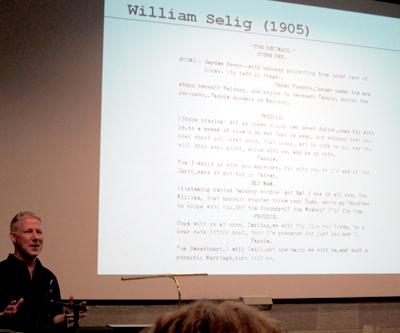

In his keynote address, “The Screenplay: An Accelerated Critical History,” Steven Price (above) declared a more abstract interest in the ontology of the screenplay but proposed that there was no clear-cut way of defining it. Historically, the screenplay takes many forms. Steven pointed out that even in Hollywood, there were many alternative formats, ranging from detailed breakdowns to the “master-scene” method (the option that didn’t specify shots or camera positions). And conceptually, the screenplay carried traces of its original production purposes, as well as other constellations of meaning. (Mack Sennett scripts seem to him part of a Sadean tradition of dehumanized, repetitive recombination.) So if there is a distinctive mode of being of the screenplay, outside of its role in production, it will turn out to be a messy one.

Envoi

J. J. Murphy presents a paper on Ronald Tavel. Photo courtesy Richard Neupert.

If we conceive studies of screenplay and screenwriting as revolving around specific research questions, those of us interested in film as art can learn a lot. If our interests are in film history, researchers can show how organizations of production and individual choices by screenwriters/directors can shape the final product. For those of us interested in more theoretical explorations, asking about the nature and “mode of being” of the screenplay can’t help but make us think more about the ontology of cinema itself.

And if we want to know films more intimately, being aware of the creative choices that were made by the filmmakers throws a spotlight on aspects of the film we might otherwise not notice. It’s all very well to say we’ll examine the film “in itself,” but our attention is invariably selective. Knowledge of behind-the-scenes decisions can sharpen our awareness of artistic matters. Anna Sofia’s research on Bergman, like Marja-Riitta Koivumäki’s paper on Tarkovsky’s screenplay for My Name Is Ivan, activates parts of the film for special notice.

Because there were split sessions at the conference, and because I was plagued by jet lag, I couldn’t attend every panel and talk. I regret missing papers I later heard were very fine, and I haven’t written up everything I heard. I haven’t sufficiently talked about screenwriting pedagogy, represented in papers like Lucien Georgescu’s dramatic appeal to rethink whether screenwriting should be taught in film schools, or Debbie Danielpour’s stimulating survey of her methods of teaching genre scripting. So this is just a small sample of what these folks are up to. But you can tell, I think, that they’re posing questions at a level of sophistication that my 1960s cohort couldn’t have envisioned. Despite what the cynics say, there is progress in academic work.

As for men’s underpants: All is explained here.

I’m grateful to conference organizers Ronald Geerts and Hugo Vercauteren for inviting me to speak at the gathering. I must also thank conference organizer and old friend Muriel Andrin, along with Dominique Nasta and their colleagues and students from the Arts du Spectacle Department at the Université Libre de Bruxelles. My friends at the Cinematek, Stef and Bart and Hilde, helped me with my PowerPoint. Thanks as well to the Universitaire Associatie Brussel (Vrije Universiteit Brussel / Rits-Erasmushogeschool Brussel) and Associatie KULeuven (MAD-Faculty / Sint Lukas Brussel). A high point of the event was the visit to La Fleur en Papier Doré. Special thanks to Gabrielle Claes for her heartfelt introduction to my talk, not to mention a delicious bucket of moules.

A founding document in the contemporary study of the screenplay is Claudia Sternberg’s Written for the Screen: The American Motion-Picture Screenplay as Text (Stauffenburg, 1997). Other books central to the conference cohort include Steven Maras’s Screenwriting: History, Theory, and Practice, Steven Price’s The Screenplay: Authorship, Theory and Criticism, J. J. Murphy’s Me and You and Memento and Fargo: How Independent Screenplays Work, and Jill Nelmes’s anthology Analysing the Screenplay, which includes many essays by members of the group. See also the affiliated Journal of Screenwriting.

For more information on the Screenwriting Research Network, go here. (Thanks to Ian Macdonald for the link.) The next conference will be held in Sydney, and the 2013 one will take place in Madison, Wisconsin.

P.S. 22 Sept 2011: A panel discussion with Jean-Claude Carrière held during the conference is available here. Although the site is in Dutch, the discussion is in English. Thanks to Ronald Geerts for the information.

P.P.S. Thanks to Joonas Linkola for a spelling correction!

Coke does go through you pretty fast. Richard Neupert at a Coca-Cola machine that exploits a Brussels landmark.

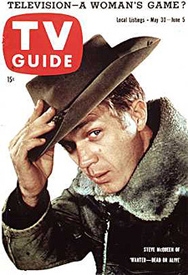

JCC

The Milky Way (La Voie lactée, 1969)

DB here, writing from a gray Brussels:

All the problems of a film are in the script.

When a film is made, the screenplay disappears.

When you consider what a scene needs to express, ask: How can the actor act it?

When you’re writing a scene, try to act it out yourself.

Rather than letting dialogue explain the action, let the action explain the dialogue.

It will always be possible to make films. Don’t forget to make cinema.

These and other epigrammatic insights flowed easily from Jean-Claude Carrière during his visit to the Cinematek of Belgium and the annual conference of the Screenwriting Research Network. I hope to devote a later blog to other attractions of this stimulating get-together. For now, a brief tribute to the volcanic charm of the legend known as JCC.

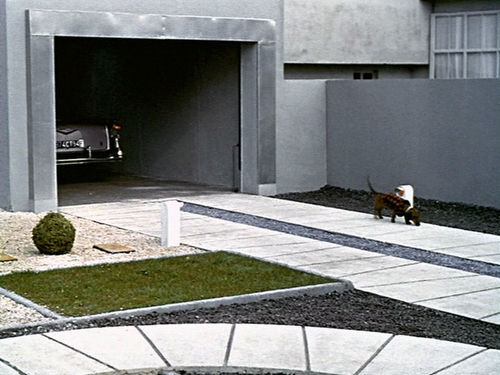

JCC entered cinema under the aegis of Jacques Tati. Tati wanted someone to turn M. Hulot’s Holiday and Mon Oncle into novels, and the very young writer seemed the right candidate. But Tati quickly learned that JCC didn’t know how a film was made. So he assigned Pierre Etaix and the editor Suzan Baron to tutor the lad in the ways of cinema. First lesson: Go through M. Hulot on a flatbed viewer, examining the script line by line while watching shot by shot. As a result, JCC says, he began to understand “the film that you don’t see.”

In the course of his career, JCC has written novels, plays, essays, screenplays, even a scenario for a graphic novel. In the process he became one of the most distinguished and respected screenwriters of the last fifty years. His most famous collaborations were probably with Buñuel, from Belle de Jour (1967) to the master’s last film, That Obscure Object of Desire (1977). He worked with Etaix (The Suitor, 1962), Forman (Taking Off, 1971), Schlöndorff (The Tin Drum, 1979), Godard (Every Man for Himself, 1980), Wajda (Danton, 1983), Oshima (Max mon amour, 1986), Kaufman (The Unbearable Lightness of Being, 1988), Peter Brook (The Mahabarata, 1989), Malle (Milou en Mai, 1990), and Haneke (The White Ribbon, 2007). He has also become known for his work on major French costume pictures and adaptations, such as Cyrano de Bergerac (1990) and The Horseman on the Roof (1995), as well as work with younger directors, including Wayne Wang (Chinese Box, 1997) and Jonathan Glazer (Birth, 2005). His TV scripts are numberless.

Directors both young and old come to him for the unique forms of collaboration that he offers. Instead of going off to write the screenplay, JCC meets frequently with the director. (Sometimes the director stays in his house.) He might ask the director to write the script for him, and they go over the result. Through these methods, JCC tries to help the director “find the film that he wants to make.” But his methods are flexible, tailored to the director’s temperament. When he was working with Buñuel, the men met daily to tell each other their dreams, some of which wound up in The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie (1972). Similarly, JCC prefers to meet with the actors before production, letting them try out the parts so that he can revise things for each one’s habits of speaking. For Cyrano, Depardieu read the entire play aloud, taking all the parts, and then listened to it over and over on cassettes to refine his interpretation.

Brussels gave JCC a busy twenty-four hours. In conversation with the critic Louis Danvers he introduced a Cinematek screening of The Milky Way. He gave a keynote address for the Screenplay Network conference, and he participated in a panel discussion with members of the Flemish Screenwriters Guild at the film school RITS. These sessions ranged freely over his career and his conceptions of filmmaking. He believes that there is a language of film that sets it apart from other arts. That language is grounded in the play of meaning and emotion that comes from putting one shot after another.

He explained the point through an example that seems at first to be a restatement of the classic Kuleshov effect. In Shot 1, a man in his apartment looks out the window. Shot 2: The street. A woman is walking with another man. We’ll assume that our man is seeing them. Shot 3: Our man reacts.

But contrary to Kuleshov’s dictum, his facial expression should not be neutral. In fact, his expression tells us how to understand the scene. If the man looks upset, we surmise that he’s jealous. If he’s benevolent, we assume that the woman is a friend, his daughter—or a flirt. The filmmaker needs not only techniques like framing and cutting, but also the performances of actors.

Now cut to the woman in her bedroom brushing her hair. We need to make sure the audience understands that it’s the same woman, so maybe we have to go back and add a shot to the earlier scene, a closer view of her in the street. This constant flow and readjustment of images is based on guiding the spectator discreetly but firmly through the action. The audience isn’t aware of this “secret film,” but it governs everything the viewer thinks and feels.

For this reason, the young screenwriter needs to learn everything about how a film is made. When JCC was acting in The Wedding Ring (1971), a film starring Anna Karina, he learned that simply getting up from a couch can be a complicated matter. When he stood up spontaneously, dipping forward to lift his body, the cinematographer had to correct him: It looked awkward on film. JCC learned that he had to stand up in an unnatural way, with his feet spaced and his back rigid, so that it looked smooth on film. The screenwriter must know that even the smallest moment of action, easy to write in the comfort of a study or a café, is subject to the contingencies of production.

For this reason, the young screenwriter needs to learn everything about how a film is made. When JCC was acting in The Wedding Ring (1971), a film starring Anna Karina, he learned that simply getting up from a couch can be a complicated matter. When he stood up spontaneously, dipping forward to lift his body, the cinematographer had to correct him: It looked awkward on film. JCC learned that he had to stand up in an unnatural way, with his feet spaced and his back rigid, so that it looked smooth on film. The screenwriter must know that even the smallest moment of action, easy to write in the comfort of a study or a café, is subject to the contingencies of production.

Where to get ideas for films? From the classics, of course. (“Balzac is the greatest screenwriter—every character is vivid.”) But above all you must observe reality. Tati taught JCC to sit vigilantly in a café. Study everyone who passes. Notice details. Imagine the person as a character in a story. Give him or her some motivations. What you must do is “find the fiction in the reality.” When JCC presided over the French film school La FEMIS, he promoted an exercise that required students to move out into a public space, like a market, and come back with stories about the people they saw. JCC praised Tati’s genius for spinning gags and situations out of passing life—“as if God had created the world so that it could furnish a film by Jacques Tati.”

JCC must be one of the few screenwriters who doesn’t gripe about his work being changed in its final incarnation onscreen. He sees the screenplay as ephemeral, the chrysalis for the butterfly. Once you accept the fact that your text must be sloughed off on its way to becoming cinema, you can take joy in your work. For young people, JCC advised the same relaxed, exploratory attitude. Conceive of yourself as a writer, able to move across media. The venues for your writing are constantly changing, so be prepared to write for television as well as film, to write comics and documentaries and plays. Above all, “Don’t despair of the future of cinema. It’s wide open.”

Jean-Claude Carrière turns eighty next week.

The best introduction to Carrière’s career and ideas that I know is his book The Secret Language of Film (Faber, 1995). Some of this text overlaps with Exercice du scénario (FEMIS, 1990), coauthored with Pascal Bonitzer. That book is worth reading too, but it hasn’t to my knowledge found English translation. An illuminating interview is here.

P.S. 11 September 2011: Thanks to Jonathan Rosenbaum for correcting an error in JCC’s filmography, which I’ve rectified above. Jonathan also remarks:

I assume that you know, by the way, that Carrière appears in a scene of Certified Copy, playing something similar to the “wise old guru” role played by the Turkish taxidermist in Taste of Cherry and the doctor in The Wind Will Carry Us.

I did know and should have worked it in!

P.P.S 22 September 2011: A panel discussion with Jean-Claude Carrière held during the conference is available here. Although the site is in Dutch, the discussion is in English. Thanks to Ronald Geerts for the information.

Mon Oncle (1958). “I followed Tati more or less everywhere, usually with Etaix, attending projections followed by long anxious discussions. (‘Can we clearly see the dog’s tail go past the electric eye that shuts the garage door? Yes? Clearly? You’re sure people will see it?’)

Julie, Julia, & the house that talked

Enchantment.

DB here:

For the last couple of decades, American filmmakers have been exploring storytelling options that break up timelines. Flashbacks are the most obvious examples, but so too are time-travel and parallel-universe stories; Source Code was a recent example, which I talked about here. Elsewhere I’ve mentioned that these new formats revive narrative innovations that we find in 1940s Hollywood movies—the topic of my course at the Zomerfilmcollege in Antwerp in July. While planning that course, I’ve come up with an intriguing pair of movies that can tell us something about how the romance film, drama or comedy, handles a couple of features of storytelling we probably don’t think enough about.

When parallel lines meet

Julie & Julia.

What is a story made of? Minimally, characters and their doings. Some theorists of narrative offer a more abstract description. Stories, they say, consist of agents (characters) who exist in states of affairs (John was married to Mary) and who perform actions (John tried to divorce Mary). Still talking abstractly, a narrative organizes the agents’ states of affairs and actions according to certain principles.

Principles of time, indicating sequence and duration. John married Mary, then after a while he tried to divorce her. Some theorists think that ordering events and states of affairs in time is the essential feature of narrative.

Principles of causality. John is tried to divorce Mary because he fell in love with Audrey. Perhaps not all narratives exhibit causality, but most surely do.

Principles of space, a place in which the story unfolds. John met Mary at the supermarket and they fell in love at the beach, but at work one day John was introduced to Audrey, the new head of his department and they had coffee at Starbucks…. Some stories rely on a very specific sense of locale (e.g., a tale of a man buried alive), while others evoke the environment rather vaguely (as in jokes beginning with a priest, a rabbi, and a minister walking into a bar).

These core ingredients look very general, but they can be good guides in starting to analyze a story. We can ask how time is organized, what causes what to happen, and how space is patterned, and the answers can reveal intriguing things about the way the narrative works.

There’s one more principle worth remembering. Most narratives involve parallelism. That occurs when characters, situations, actions, or other factors are likened to or contrasted with one another. (I don’t say “compared or contrasted” because “comparison” means pointing out both likenesses and differences. Call me fussy.) So our hypothetical tale might include another man, John’s friend Jack, who lives a happy married life with Jill. In fact, romantic comedies often include subplots, as when we get a secondary love affair between friends of the main couple. Serendipity, discussed in another blog entry, is a straightforward instance.

Sometimes a filmmaker can create an entire plot out of parallels. Griffith did it in Intolerance, drawing comparisons among different historical epochs. More common is the film that gives two or three protagonists equal weight and likens or contrasts their situations. In Wedding Crashers, John’s romantic pursuit of a woman is counterpointed with the raunchier efforts of Jeremy to escape a woman pursuing him. Kristin has proposed that some plots create “parallel protagonists” who pursue separate goals but converge because one of them tries to meet the other, as in Desperately Seeking Susan and The Hunt for Red October. And in what Variety calls “criss-crossers,” or what I call “network narratives,” many characters become fairly salient as they intersect, and each can be compared to another. Examples would be Grand Hotel, Tales of Manhattan, and Love, Actually, which depend largely on contrasts.

Kitchen stories

Julie & Julia.

So parallelism can operate at greater or lesser strength, as a minor accessory to the flow of time, causality, and space; or it can become a firmer principle shaping the story.

This sort of firming up is visible in Nora Ephron’s Julie & Julia. We have two sets of characters in two time frames: Julia and her husband Paul in the late 1940s and 1950s, and Julie and her husband Eric in the early 2000s. The two stories are crosscut, so that we alternate between them as each one develops.

What links them? Most explicitly, some causal factors. Julie is dissatisfied with her thankless job. Since she loves to cook, she decides to devote a year to trying all the recipes in Julia Child’s famous Mastering the Art of French Cooking. At Eric’s suggestion she writes a blog chronicling her daily efforts, and gradually she finds an audience, eventually making her a celebrity. So Julia’s cookbook becomes a central cause in changing Julie’s life.

What about Julia? In her postwar plotline, she is also unfulfilled in her career, but she loves to eat. She learns French cuisine and revels in creating elaborate dishes. At the urging of Paul, she collaborates with two friends in writing, and eventually publishing, a cookbook for “servantless” American housewives. So Julia’s efforts are presented as another chain of cause and effect.

The parallels are obvious. Both women turn to cooking in search of personal fulfillment. Both take up writing, to share their knowledge and experiences with others, and both become published authors. Both have supportive husbands who inspire them. The film is about love, but each couple’s bond isn’t threatened by an outside figure, as in other romance films. Their bond is strengthened by the love of food, not to mention good-hearted sex.

Some more detailed parallels emerge as well. There are spatial contrasts: Julia is exhilarated by Paris and their lush apartment, while Julie’s depression is deepened by their cramped Queens walkup, perched above a pizza joint. Both Julie and Julia encounter initial disappointment in their efforts to reach an audience. Julie’s blog initially finds only her mother as a reader, while Julia’s manuscript is at first turned down by publishers.

Both couples enjoy sharing their food with friends, although Julie’s college pals, now self-centered businesswomen, aren’t as supportive as Julia’s writing partners. Both couples undergo a strain, with Paul being interrogated by McCarthyite politicians and Eric made annoyed by Julie’s growing obsession with Julia and the blog’s readership. Even specific motifs, like butter, lobsters, and boning a duck, draw out parallels between the two heroines. Montage sequences highlight the linkages, as when pairs of shots show both women cooking and tasting the same dishes.

Julie in fact becomes what Kristin in Storytelling in the New Hollywood calls a parallel protagonist. Often in such plots, one protagonist becomes fascinated with the other, as Salieri gets obsessed by Mozart in Amadeus. Julie is captivated by Julia’s charisma, to the point of wearing her signature pearl necklace.

Julie and Julia never meet; it’s hinted that in her old age Julia is miffed by Julie’s blog. Yet the plotlines meet in a spatial parallel. Julie and Eric visit the Smithsonian reconstruction of Julia’s kitchen. He takes a picture of it.

After they’ve left, the display shifts into an image of the original kitchen, where Julia and Paul get the news that her book has been printed. The scene finally conjoins the couples and reaffirms each woman’s success and each man’s pleasure in it.

Two times in one space

Two times blend within a single domestic space in another movie built out of parallels, Irving Reis’s Enchantment (1948). Again the action plays out in different eras: a turn-of-the century story of love and jealousy within the Dane family, and tale of awkward courtship set during the blitz.

In the first story, the widower John Dane adopts an orphan girl, Lark. After his death, the eldest daughter Selina rules the house, coddling her brothers Pelham and Rollo but treating Lark like a servant. Once they have grown, both men come to love Lark (Teresa Wright), and she reciprocates with love for Rollo (David Niven). Selina blocks their union through several stratagems, relying partly on Rollo’s reluctance to challenge her, and Lark leaves to marry an Italian count. She becomes the great lost love of Rollo’s life.

An old bachelor, Rollo lives in the family home until his grandniece Grizel (Evelyn Keyes) arrives from America, posted to help the British war effort. Grumbling at first, Rollo eventually comes to enjoy having her in the house, especially when Grizel attracts the attentions of a Canadian flyer, Pax (Farley Grainger). She fends him off, on the grounds that she’s already been hurt in love once and doesn’t want to risk it again. At the climax, as a bombardment begins, Rollo urges Grizel to go to Pax. He says, acknowledging his wasted life, that if she loves him, she can’t wait a moment; things can change in an instant.

In effect, Rollo acknowledges the parallels between the two generations, seeing Grizel on the verge of making his mistake. “Don’t stop to bargain for happiness.” Grizel races out and finds Pax as the bombs fall. She achieves the happiness that Rollo foolishly lost. Back at the house, Rollo is killed when a bomb strikes the house.

I’ve presented the two plotlines sequentially, but like Julie & Julia, the film alternates them, treating the distant past as flashbacks from the wartime drama. Like Ephron’s film, Enchantment puts the climaxes side by side. The big scene of Rollo’s losing Lark to the count is followed immediately by the climax in the present, when Pax declares his love, Rollo advises Grizel to follow him, and the house is damaged, though not destroyed, by the bombardment. Again, there is a basic causal link between the eras, this time based on kinship: because Grizel is a relation she bivouacs with old Rollo. The parallels are likewise highlighted by motifs, not least the necklace that Rollo gave Lark as a pledge of love. She returned it as she departed, but after he has come to love his great-niece, he gives it to her as a token of her happiness. “She wore it one night. You’ll wear it a lifetime.”

Enchantment is based on a novel by Rumer Godden, probably best known to cinephiles as the author of Black Narcissus and The River, both turned into extraordinary films. The novel, Take Three Tenses: A Fugue in Time (1945), has a more complicated parallel structure than Reis’s film. It creates several time zones: the marriage of Dane senior and his frail wife Griselda; the growth of their children; their young adulthood; and the blitzkrieg period we see in the film. In addition, as perhaps a redundancy device, the central male is given a different name at different stages: Rolly as a child, Rollo as a young man, and Rolls as an old man.

Enchantment is more conventionally focused. Griselda is a central character in the book, but the film drops her and picks up the family saga after her death. Even then, it devotes only four short scenes to the childhood of the siblings. The result is to concentrate on the youthful Rollo-Lark romance, but it loses a string of parallels involving courtship and marriage, particularly the contrast between Grizelda and her modern namesake.

In a mildly experimental gesture characteristic of much popular fiction of the forties, Godden’s novel treats time in an unusual way. The World War II scenes are given in the past tense, but all the earlier periods are rendered in the present tense. So you get passages that mix different eras.

Proutie took it up to Rolls in his dressing room, where Rolls was sitting.

“The post, Mr. Rolls.”

“Go away,” said Rolls. “Leave me alone.”

Proutie put the letter on the table at Rolls’ elbow and went away.

Years before there is another letter, a letter written by Rolls in answer to many letters of Selina’s.

She reads it in her room sitting in the blue-and-white armchair on which this afternoon, dressing to have tea with Pax, after she had been asleep, Grizel tossed down her pyjamas and left, standing by it on the rug, a pair or swansdown slippers that she called her “scuffs.”

Selina as a girl has a swansdown muff, dyed violet with a rose in it, but she keeps it tidily in tissue paper in the cupboard; she does not throw her things about nor leave them on the floor. As she reads Rolls’s letter, Selina is not a girl; she is an elderly woman and that day she feels old. You ask me, Lena, why I don’t come home. That is a question that is rather difficult to answer. I seem to have a distaste for the house.

Call it dumbed-down Proust or Faulkner if you want. In any case, the fluid shifts from past to present are given not only through adjustments of tense but also by emblematic objects, like the letters and the swansdown accessories, that lead us, stepwise, through time. It’s almost as if Godden were mimicking cinematic technique, dissolving from one image to another (letter to letter, slippers to muff).

The film picks up the hint and does sometimes dissolve from the present to the past. More original, and perhaps closer to the seamless uniting of periods, is the way the narration revives a rare device. In Caravan (1934), the returning Countess Wilma turns to her old governess, asking if she remembers the last day she was in her bedroom. The camera pans left to the governess, who gets a faraway look in her eyes.

Then she scrunches up her face and commands Wilma to come to her. Pan right to Wilma, now a child, in a tantrum.

Interestingly, the whole flashback is played in this one shot, ending on the governess recalling the scene and tracking back to a full shot of the grown-up Wilma.

Similarly, several Enchantment transitions are handled in a single shot, but here the panning movements typically highlight enduring parts of the house. Old Rollo has grudgingly let Grizel stay in Selina’s bedroom. As Rollo says, in an auditory flashback, “There’s no such thing as an empty room,” we see Grizel at the dressing table. The clock stops and as she puts it up to her ear, she looks screen right.

The camera pans to the door, with a maid calling, “Miss Selina,” and then pans back to show Selina as an adolescent at the dressing table.

Nearly all of these single-shot transitions pivot around items that have remained in the house over the years, like a clock or a chandelier or the central staircase. These reflect passages in Godden’s novel that itemize household furnishings across the years or use them to tie together two scenes in different years.

No such thing as an empty room

While speaking of those years, I’ve oversimplified a bit. In Take Three Tenses, even the World War II era, the most recent setting of the action, is enclosed in a frame given in what we might call the persisting present. The book begins:

The house, it seems is more important than the characters. “In me you exist,” says the house.

There follows a past-tense account of the elderly Rollo’s learning that his family’s lease on 99 Wilshire Court is up. Then we have a several-page tour, in the present tense, of the house from top to bottom. It’s launched by this sentence:

In the house the past is present.

Moreover, Godden takes literally the house’s claim that “In me you exist.” She confines all the novel’s directly presented action to the building. What happens outside, we learn through reports. At the book’s end the opening tour is echoed in miniature. There various lines of dialogue from all periods mingle, and the narration insists that the house will endure “in its tickings, its rustlings, its creakings” and ends “In me you exist.” So the house, past, present, and future, enfolds all the dramas played out in it.

The sovereignty of domestic structure is provided by the novel’s chapter structure, which, after an initial “Inventory,” presents “Morning,” “Noon,” “Four o’Clock,” “Evening,” and “Night.” The headings gather only scenes taking place at the named time of day, though the scenes are gathered freely from across many years. (Take that, Alan Ayckbourn.) The fugal voices come together at these nodal points. Once again, the house sets the rules, the household routines being more important than a chronological or causally-driven time scheme.

Godden’s effort to suggest layers of the past in any room or time of day is difficult to capture on film. Perhaps Richard McGuire, working in the medium of comics, comes closer with his famous 1989 piece “Here.” A room’s corner is invaded by events from many periods.

An approximate cinematic equivalent is Ivan Ladislav Galeta’s Two Times in One Space (1976/1985), with a time delay that creates ghostly figures from moments 219 frames apart.

Only the room remains stable in this out-of-phase presentation of a meal prepared and eaten. (Perplexingly, the action on the distant balcony unfolds in standard duration.)

Galeta’s version isn’t an option for a classical Hollywood film like Enchantment. The closest analogy comes during a parallel between Rollo as a young officer out to meet Lark, and Pax as he hurries to meet Grizel. A graphically matched dissolve puts Pax in Rollo’s place.

This device, however, doesn’t convey the persistent presence of the house. Enchantment finds another way to shelter its interchange between past and present. It lets the house talk.

As the film opens, the camera approaches 99 Wilshire Court and the house introduces itself to us in voice-over commmentary. “You almost passed me.” The house invites us to “see what the mirrors have seen.” It turns mournful. “I miss my people. In me they live.” The camera coasts through empty rooms, as we hear voices welling up from different parts of the past.

We don’t know the speakers yet, but the device prefigures the dramas to come, as well as suggesting Godden’s idea that the house endures as a repository of fugitive, phantom life. As the camera reveals Rollo talking with his solicitor, the voice-over explains, “The house is his story.”

Although we might not recognize it on first viewing, this is another single-shot flashback, since in the initial present, that of the deserted house, Rollo is already dead. The narration is taking us back to the opening phase of the wartime plotline.

Trimming back Godden’s ensemble plot, the narration gives us a protagonist and identifies what happens to the house with what has happened to him. Yet the house takes precedence, in that the flashbacks aren’t triggered by his or anyone else’s memory. This is rare in classical cinema of the period, which usually motivated returns to the past by someone recounting or recalling earlier events. It would be too glib to say that these flashbacks are “the house remembering,” but the fact that transitions are more objectively anchored than usual does yield a sense that time has a shape that we sense more acutely than the characters can.

Subjectivity does enter, at least apparently, in Rollo’s imaginary dialogues with Lark. At various points she speaks to him in imagination, or in some realm the lovers share. Again, though, we can’t ascribe those voices to his mind. After he has been killed, the camera tracks back from his body.

As in the beginning, voices haunt the parlor. During the camera movement the young Lark asks, “We shall always be in love, won’t we?” “Yes,” Rollo replies. “Even when we’re old?” “Even when we’re old.”

The film doesn’t confine its action as strictly to the house as Godden’s novel does. We follow Grizel to her job at the military post, and the young Rollo to a shop to buy Lark a necklace. Nevertheless, the sense of enclosure, not to mention closure, is provided after we’ve seen Rollo felled by the German bombardment. The camera continues backward, through a window as the house’s voice-over narration assures us that no story really ends. The house seems to have cheered up in the course of the narrative; no longer missing its people, it looks forward to a new generation. Echoing the future-oriented ending of Take Three Tenses, the house concludes: “In me, the young will live again, with the heart’s lease on life.”

Sometimes we expect that recent films will be more complex than older ones, and that’s often true. But an older film often turns out to have more angles than we get nowadays. Julie & Julia is an amusing and touching entry in the American Cinema of Quality. (Is Scott Rudin today’s Samuel Goldwyn?) And it’s true that Enchantment doesn’t multiply its parallels as ingeniously as Julie & Julia does. Yet Ephron entertains us with clever reiterations of the basic comparison of the two women, given in the title anyway. Enchantment avoids such detailing in search of a wider emotional range.

Julia is admirable, and Julie grows by imitating her, but their stories don’t carry the bittersweet resonance of the stories of Rollo and his descendants. You can argue that Enchantment softens some of the novel’s harsher side; there Rollo loses Lark by prevaricating, while in the film he is partly the victim of bad luck. (The trains stopped running.) Even so, the film preserves the severe self-denial we find in Grizel, who sees her fear of passion as “the Dane vice,” and the bitter self-reproach of the lonely Rollo. Then there’s the house as a wise reliquary of human lives, humming with voices from the past. Julie & Julia makes its locales simply part of many tidy parallels. Enchantment lives by comparisons too, but it also lets space come forward as a factor that can, at least momentarily, become as engaging as other dimensions of storytelling.

The approach to narrative theorizing I started out with is, roughly speaking, action-oriented. The ideas of time, causality, and space emerge logically out of a concern with how the plot lays out its arcs of action. An alternative approach, no less fruitful, is agent-oriented. It treats action as secondary to the portrayal of character traits and psychological activity. The agent-centered perspective is especially useful for studying narratives in which the characters seem larger than life and their vividness exceeds their role in the narrative patterning (in Dickens, for instance), or when there is very little external action (as in Beckett). The classical narrative tradition of Hollywood, despite its powers of characterization (helped out by the star system), seems to me to to concentrate most on organizing action. There plot is usually primary. And there’s nothing wrong with that!

For more on flashbacks and their degrees of subjectivity, see “Grandmaster Flashback” on this site.

My quotation from Take Three Tenses: A Fugue in Time (Boston: Little Brown, 1945) comes from p. 174. John R. Frey argues that the tense shifts in the novel are actually more subtly discriminated than I’ve indicated. Godden uses, he claims, the present and the imperfect for the main action and the perfect and the past perfect for the flashbacks. See “Past or Present Tense? A Note on the Technique of Narration,” The Journal of English and Germanic Philology 46, 2 (April 1947), 205-208.

Promoting space as a narrative factor, rivaling time and causality, is something Kristin and I have written about in various places. See in particular Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema, Chapters 6 and 7.

A short film inspired by McGuire’s “Here” is, well, here. Chris Ware, who wrote an essay, “Richard Mcguire and ‘Here’–A Grateful Appreciation,” Comic Art no. 8 (2008), 4-7, seems to have been inspired by it in certain installments of his Building Stories; also try here, searching under “Building Stories.”

Galeta’s Two Times in One Space is available on this DVD collection of his works.

Julie & Julia.

Take it from a boomer: TV will break your heart

DB here:

Every so often someone will ask Kristin and me: “Why don’t you write about television?” This is usually followed by something like:

”You’re interested in narrative. The most exciting narrative experiments are going on in TV, not film.”

”You’re interested in visual experimentation. The most exciting developments in visuals are in TV.”

”TV is where the audience is.” Or “TV is where the culture is.”

”Film is borrowing a lot from TV, and producers and directors are crossing over.”

We might answer by saying we don’t watch any TV, but that would be a fib. Like everybody, we watch some TV. For us, it’s cable news commentary, The Simpsons, and Turner Classic Movies.

Truth be told, we have caught up with some programs on DVD. We watched the British and the US versions of The Office and enjoyed both (though the American version, no surprise, makes the characters more lovable). Kristin watched The Sopranos’ first season for a particular project. For similar purposes I watched and enjoyed Moonlighting and some Michael Mann TV material. Intrigued by the formal premise of 24, I dipped into the first season, but I found it visually so wretched I couldn’t continue. I got through four seasons of The Wire on DVD, largely because of the Pelecanos connection, but I found it over-hyped. It seemed to me a sturdy policeman’s-lot procedural, but rather fragmented and uninspiringly shot.

That’s it for the last three decades. No real-time monitoring of episodic TV (we haven’t seen Lost or Mad Men or the latest HBO sensations) and none of the reality shows or the music shows or even comedy like Colbert or Jon Stewart.

So we aren’t plugged in to the TV flow. Americans currently log over four and a half hours a day in front of the tube, so clearly we’re derelict in our duty. As Clay Shirky points out in Cognitive Surplus, TV viewing is Americans’ unpaid second job.

But why don’t I start following episodic TV? The answer is simple. I’ve been there. I was a TV kid before I was a film wonk. And I can assure you that watching TV leads to painful places—frustration, anger, sorrow. All you’re left with is nostalgia.

Commitment problems

I see the difference between films and TV shows this way. A movie demands little of you, a TV series demands a lot. Film asks only for casual interest, TV demands commitment. To follow a show week after week, even on a DVR, is to invest a large part of your life. Going to a movie demands three or four hours (travel time included).

Whether a movie is good or bad, at least it’s over pretty soon. If a TV show hooks you, prepare for many long-term ups and downs—weak episodes, strong ones, mediocre ones. Favorite actors leave or die, and replacements are seldom as good as the originals. A new character may be charming or annoying. An intriguing hero may accumulate distracting sidekicks. Plots take weird turns, sometimes dillydallying for months. All this can drag on for years.

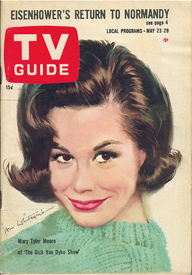

Of course TV-philes enjoy this slow samba. They point out, rightly, that living through the years along with the characters, watching them change in something like real time, brings them closer to us. Who doesn’t appreciate the way Mary Tyler Moore evolved into something like a feminist before America’s eyes? As early as 1952, the sagacious media critic Gilbert Seldes pointed out that intellectuals who thought that TV was plot-dependent were wrong.

It is natural that the actual plot of a single self-contained episode should be comparatively unimportant. . . . The very limitations of the style leads its creators to develop characters of considerable depth, to create dramatic conflict out of the interaction of people rather than out of an artificial juxtaposition of events. As television is a prime medium for transmitting character, this is all to the good (Writing for Television, pp. 115-116)

We get to know TV characters with an informal intimacy that is quite different from the way we relate to the somewhat outsize personalities that fill the movie screen. We learn TV characters’ pasts, their hobbies, their relations with kin, and all the other things that movies strip away unless they’re related to the plot’s through-line.

Having been lured by intriguing people more or less like us, you keep watching. Once you’re committed, however, there is trouble on the horizon. There are two possible outcomes. The series keeps up its quality and maintains your loyalty and offers you years of enjoyment. Then it is canceled. This is outrageous. You have lost some friends. Alternatively, the series declines in quality, and this makes you unhappy. You may drift away. Either way, your devotion has been spit upon.

It’s true that there is a third possibility. You might die before the series ends. How comforting is that?

With film you’re in and you’re out and you go on with your life. TV is like a long relationship that ends abruptly or wistfully. One way or another, TV will break your heart.

TV brat

Trust me, I’ve been there. Unlike most film nerds, I wasn’t a heavy moviegoer as a child. Living on a farm, I could get to movies only rarely. But my parents bought a TV quite early. So I grew up, if that’s the right phrase, on the box.

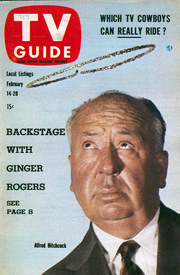

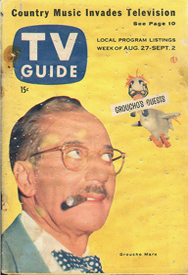

Childhood was spent with Howdy Doody (1947-1960) and Captain Video (1949-1955) and Your Hit Parade (1950-1959) and Jack Benny (1950-1965) and Burns and Allen (1950-1958) and Groucho (You Bet Your Life, 1950-1961) and Dragnet (1951-1959) and Disneyland (1954-2008) and The Mickey Mouse Club (1955-1959). With adolescence came Alfred Hitchcock Presents (1955-1965) and Maverick (1957-1962) and Ernie Kovacs (in syndication) and Naked City (1958-1963) and Hennesey (1959-1962) and The Twilight Zone (1959-1964) and Route 66 (1960-1964) and The Defenders (1961-1965) and East Side, West Side (1963-1964).

Some of the last few titles I’ve mentioned evoke particularly fond feelings in me. At a crucial phase of my life, they presented models of what the adult world might be.

For one thing, adults had an easy eloquence. Some of these shows seem overwritten by today’s standards, but actually they brought to television a sensitivity to language that seems rare in popular media now. Bret Maverick had a smooth line of patter, and even racketeers on Naked City could find the words. Dragnet‘s dialogue is remembered as absurdly laconic, but actually it showed that very short speeches could carry a thrill. At the other extreme were the soliloquys in Route 66. One that sticks in my mind came from a daughter, torn between love and exasperation, saying how touched she was when her father called one of her simpleton boyfriends “uncomplicated.” (The line was modeled on something said by Faulkner, I think.) I don’t recall characters insulting one another as much as they do nowadays, and of course obscenity and body humor were yet to come. At that point, TV relied so much on language that it might be considered illustrated radio.

Second, these shows made heroes of adults who were reflective and idealistic. They mused on social problems and thought their positions through. The father-son lawyers of The Defenders often disagreed about the moral choices their clients had made, and as a result you saw the different ways in which legal cases shaped people’s lives and public policy. Even a cop show like Naked City was less about fights and chases than it was about the causes, and costs, of crime.

Third, adults were empathic. This was partly, I suppose, because I was drawn to liberal TV; but I think it’s striking that my favorite dramatic shows showed professionals committed not to billable hours but to helping other people.

El segundo pueblo

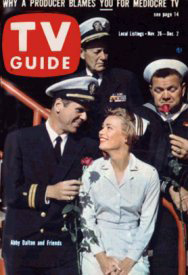

These qualities were epitomized in Hennesey. The continuing cast was small. Chick Hennesey (Jackie Cooper) is a navy doctor in his mid-thirties. His irascible superior Captain Shafer, is played by Roscoe Karns, bringer of dirty fun in 1930s and 1940s movies (“Shapely’s my name, shapely’s my game”). Nurse Martha Hale (Abby Dalton) serves as a romantic interest for Hennesey, and Max Bronski (Henry Kulky) is a dispensary assistant; both are vivid characters in their own right. A few others pop in occasionally, notably the rich eccentric dentist Harvey Spencer Blair III (played with eerie passivity by James Komack).

The series began as a situation comedy, but soon it became an early instance of the “dramedy”—the TV equivalent of sentimental comedy. In this classic genre, moderately grave problems cannot shake the essential concord of human relations. The tonal mixture makes a laugh track distracting; Hennesey‘s was eventually phased out.

The series was created and largely written by Don McGuire, who modeled his protagonist on a doctor he admired. Hennesey is l’homme moyen sensual, a man of no great ambitions or grand passions. He smokes cigarettes (Kent was a sponsor) but, surprisingly, doesn’t drink alcohol. He served in the army when very young (at Guadalcanal), went to UCLA medical school, and was drafted into the navy. Neither a career officer nor an ordinary doctor, he is more at home with enlisted men than the brass.

Hennesey isn’t a dramatic blank, but his virtues are quiet ones. He simply wants to help people get over the daily bumps in the road. He stammers when bullied by someone more aggressive, but sooner or later he quietly stands his ground. When he has a chance to do something decisive, he does it without fanfare. In the pilot episode, he has to override Shafer in order to extricate a man’s arm from a flywheel. But afterward he is likely to wonder whether he did the right thing. He often confesses his fears and weaknesses. Hennesey is a prototype, far in advance, of the caring, sharing male. He is, as Martha sometimes tells him, nice; but that sounds too soft. He is simply decent.

The plot often calls on him to confront people far more harsh and self-centered than he is. Often Captain Shafer, playing the narrative role of Arbitrary Lawgiver, assigns Henessey to unpleasant duties, like dealing with a lady psychologist who wants to find out why men join the navy. Often Henessey has to help men and women adjust to navy life, or to tell them that they are too unhealthy to continue. Sometimes he reminds arrogant doctors why they took up the calling. He also encounters civilians with problems that impinge on his own life. Going home to meet the doctor who inspired his career choice, he finds a bitter widower. In other episodes he simply observes someone else rising to the occasion. A bumbling helicopter pilot is a figure of fun until, behind the scenes, he risks his life to save a girl with appendicitis.

Everything about the series is modest: the level of the performances (only Shafer raises his voice), the accidents and digressions that deflect the plot, the cheap sets and recycled exterior shots, the jaunty hornpipe score that becomes an earworm on first hearing. But all these things enhance that TV-specific sense of a comfortable world with its familiar routines and unspoken bonds of teasing affection.

The show illustrates one of the virtues of TV of the time: talk. Characters emit single lines or even single words at a pace recalling that of the 1930s screwball comedies. Nurse Hale is the fastest, Shafer comes next, and Hennesey is left to play catch-up. In one episode, Shafer has just learned he’s going to be a grandfather, and he leaves the office euphoric. But Martha is a beat ahead.

Hennesey: I betcha this has him in a good mood for weeks.

Martha: For what?

Hennesey: For days.

Martha: Do you want to bet that within thirty seconds he’ll be in a bad mood?

Hennesey: No, that’s ridiculous.

Martha: Is it?

Hennesey: Of course. What could possibly get him upset in—?

Shafer returns, frowning.

Shafer: I just thought of something.

Martha: His first grandchild will be born overseas.

Shafer: Right.

Martha (to Chick): Think you’re playing with kids, huh?

The exchange, including blocking, takes nineteen seconds. It’s conventional, I suppose, but its brisk conviction modeled for one thirteen-year-old the possibility that adults are alert to each moment and enjoy rapid-fire sparring with their friends.

Harvey Spencer Blair III has more highfalutin rhetoric. In a 1961 episode, he declares his plan to run for mayor of San Diego.

Harvey: My election will see the rise of little people to positions of consequence, the molding of our future cultures, the era of a new world. Join with me, my dear, in crossing the New Frontier.

Martha: Leave the petition with me, Dr. Kennedy.

Harvey: I revel in the comparison.

Here even the double takes are modest. Characters react with a frown or a tilted chin or a widening of the eyes or a slight shake of the head. There can be verbal double-takes as well, mixed in with overlapping lines in the His Girl Friday/ Moonlighting manner. At the start of a 1961 episode, Martha enters the infirmary. Henessey is at the desk and Max is filing folders.

Without looking up, Chick says what he thinks Nurse Hale should say.

Hennesey: Morning, Max. Morning, doctor. Sorry I’m late.

Martha: I am not.

Hennesey (looking up): You’re not? It’s ten minutes after eight–

Martha (overlapping): I mean I’m not sorry. I have a very good excuse.

Hennesey: You had a run in your mascara?

Martha: I had to stop and talk to the senior nurse.

Max: Did you get it?

Martha: Yes.

Hennesey: Get what?

Max: Good, I’m glad.

Martha: Thank you, Max.

Hennesey: Get what?

Max: I bet it’ll be nice up there.

Martha: I hope so—

Hennesey (overlapping): Up where?

Max: If it isn’t too cold.

Hennesey: Oh, no, it can’t be too cold, it’s only cold up there in August—that is, if the winds from the equator don’t –Look, you two, don’t you think it’s only fair that if you discuss something in front of a third party, you might just—

Martha: A run in my mascara?

Nobody I knew talked like this, but why not talk like this? It would make life more lively. Backchat, I’ve learned over the years, can get you in trouble; life isn’t a TV show. But I still think that repartee, especially featuring stichomythia, is one of the pleasures of being a grownup. So too are the catchphrases we weave into our chitchat. The Hennesey tag I enjoyed was “El segundo pueblo,” uttered oracularly at a moment of crisis, and always translated with a different, incorrect meaning. My own life would feature motifs like “A meatloaf as big as the Ritz” (undergrad days), “Kitchen hot enough for you yet?” (grad school), and “If I’m gonna get shot at, I might as well get paid for it” (professorial years).

Being a film wonk, I can’t rewatch episodes without noting that those directed by McGuire have some flair. His staging fits the characters’ unassuming demeanor, providing a deft simplicity we don’t find in modern movies. This is doorknob cinema; scenes start when somebody enters a room. And people in the foreground respond to others coming in behind them.

The faster the gab, the slower the cutting, but extended takes can refresh the image by moving actors around. In one scene, Harvey, still planning to run for mayor, is slated for a court-martial. He enters to get the news. His somewhat zombified gait contrasts with Hennesey’s peppy, arm-swinging stride, usually on exhibit during the opening credits. (I learned things about grown-up walking styles too.)

As the shot goes on, Harvey gets the news he’s headed for the brig. Shafer and Hennesey gloat, but in the foreground, Martha suspects that Harvey’s got an ace up his sleeve.

When Harvey says he can’t attend his hearing, Martha lifts her cup: “Here comes the voodoo.”

Harvey reminds his colleagues that he’s due to be discharged from the service before the hearing date. The ensemble responds by regrouping, with Martha and Shafer trading places in the foreground and Hennesey slinking off.

When everybody has assumed a new position, Harvey volunteers to re-up, causing Shafer to shudder.

As Martha sits and Hennesey comes forward, Harvey produces some tickets for his campaign rally, at which Clifton Webb (yes, go figure) will be speaking. Interestingly, Jackie Cooper stays a bit out of sight, preparing for a later stage of the shot.

Harvey leaves, and Shafer’s attention turns to Hennesey as the person to be blamed.

Soon we are seeing characters moving in depth again as Martha gives a typical head-shake in the foreground.

The shot exploits principles of 1940s Hollywood depth staging, as did many of the filmed programs of the period. (The Defenders is particularly rich in this regard.) Simple and sharp, McGuire’s scene is more skilful than anything I saw yesterday in The Expendables.

Chick and Martha got married in the last episode of the series, in May of 1962. I would never see these people again, except in re-runs and syndication. In fact, all my favorite programs were cancelled during my high-school years. I set out for college in summer 1965, disabused of my love for TV. Ahead lay cinema, which would never betray me.

Of course watching a TV series on DVD changes the dynamic of week-in, week-out absorption; but the rhythm of real-time viewing seems to me one of TV’s artistic resources. Besides, wading through a whole series on DVD is still a hell of a commitment.

Gilbert Seldes’ Writing for Television is an original and imaginative study of conventions that still hold sway. He’s especially astute on how the differences in conditions of reception (film, public; TV, domestic) shape creative choices. Another entry on this site discusses Seldes as a critic of modern media.

On the idea that we are especially susceptible to popular culture in our early teens, see our earlier entry here.

Extensive collections of some of my favorite shows, like Reginald Rose’s The Defenders and David Susskind’s East Side, West Side are available for study in our Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research. Nat Hiken, a Milwaukee boy, also generously left us a cache of Bilkos and Car 54s.

Hennesey, once rerun on cable channels, has evidently never been published on DVD. Gray-market discs offer a few fugitive episodes, recycled from VHS, kept alive by others with an affection for the program. The most complete information I’ve found on the series is in David C. Tucker’s Lost Laughs of ’50s and ’60s Television: Thirty Sitcoms that Faded Off the Screen (McFarland, 2010), pp. 47-53. A list of episodes and broadcast dates is here.

For more on one staging technique that McGuire uses, you can visit our post on The Cross. See also Jim Emerson’s outstanding analysis of composition and cutting in Mad Men at scanners; the sequence he studies is reminiscent of mine. The best guide to analyzing TV technique is Jeremy Butler’s landmark Television Style.

George C. Scott in East Side, West Side. Stephen Bowie’s Classic TV History site provides a detailed study of this series.

PS 10 September 2010: Believe it or not, I hadn’t read A. O. Scott’s praise of current TV before I wrote this, but his thoughts develop the sort of ideas I mention at the start of this entry.

PPS 10 September 2010, later: Jason Mittell completely understood this entry. If you think that I’m saying TV isn’t worth studying , please read Jason’s careful piece. (In fact, you could count my discussion of Hennesey as an argument for studying TV!)

PPPS 11 September 2010: In my roll-call of TV that Kristin and I watched, how could I have forgotten our devotion to Twin Peaks (1990-1991)? I think I neglected to mention it because we didn’t consider of a piece with ordinary TV. We wanted to follow David Lynch’s career, and we considered the show an extension of his movies. Besides, the series showed the symptoms I diagnosed I mentioned above: episodes fluctuated in quality, and although I liked the later part of the second season better than many people did, its finale was a letdown for me too. For Kristin’s thoughts on Twin Peaks as TV’s equivalent to “art cinema,” see her Storytelling in Film and Television.

PPPPS 5 May 2011: Jackie Cooper died yesterday. The Times obituary glancingly mentions Hennesey, but ignores its real achievements.