Archive for the 'Screenwriting' Category

No coincidence, no story

Serendipity.

DB here:

I’ve been thinking about coincidences lately. Watching Hong Kong movies can do that to you.

Hong Kong vs. Hollywood?

Initial D; I Corrupt All Cops.

In Initial D (2005, Andrew Lau Wai-keung and Alan Mak Siu-fai, script by Felix Chong Man-keung), the protagonist Takumi is dazedly in love with the seductive schoolgirl Natsuki. Takumi’s pal Itsuki is out with another girl when he spots Natsuki riding out of a “love hotel” with an older man. Itsuki tells his pal. This leads to a major crisis, in which Takumi’s faith in Natsuki is shaken.

Then there’s I Corrupt All Cops (2009) from the indefatigable writer-director-producer-actor Wong Jing. (Many wish he were far more fatigable.) Unicorn, a corrupt, brutal police officer, has just been savagely beaten by gamblers who once were his allies. He staggers to a street stall and nearly collapses, spitting blood into his congee. Then he glimpses his girlfriend getting out of a rich man’s car. In the next scene, when he visits her apartment, he finds his boss, the even more corrupt cop Lak, in her bed. His realization that he can trust no one pushes him to join the police anti-corruption unit.

True, the coincidences play different roles in the two movies. In Initial D, there might be an innocent explanation for Natsuki’s visit to the hotel. Perhaps Takumi’s friend even mistook another girl for her. So we may be inclined to suspend our judgment and wait for more information about whether she’s actually being unfaithful. In I Corrupt All Cops, Unicorn’s suspicions about his girlfriend’s disloyalty are immediately confirmed; instead of suspense, we get surprise, in the form of the revelation of who her lover is.

But in each case, a major plot movement is triggered by sheer accident. Itsuki wasn’t spying on Natsugi’s assignation; he was trying to talk his date into the love hotel. Unicorn wasn’t suspicious of his girlfriend, he just happened to be across the street when she came home. Each coincidence is also a matter of timing: Had either man come a few minutes later to the location, he wouldn’t have learned the big secret. In retrospect, we are likely to think that the screenplays of Inital D and I Corrupt All Cops are using chance rather than causality to move their action forward.

Granted, Hong Kong films are generally weak in plot construction. Even the lauded films of Wong Kar-wai are built out of casual encounters and unpredictable turns of events. The old Chinese maxim “No coincidence, no story” might seem to give accidental revelations a high place in this cinema. But Hong Kong films aren’t outstanding offenders. When you start to look, you find that films in different traditions are no less committed to coincidence. After all, Rick in Casablanca notices the vast implausibility of what’s just happened: “Of all the gin joints in all the towns in all the world, she walks into mine.”

One precept of Hollywood screenwriting has been that coincidences are permissible when you’re setting up the narrative. Indeed, they’re often necessary: Circumstances have to come together in some way to launch an extended action. A sudden rainstom brings boy and girl together under the same awning, creating the cute meet, and things can build from there.

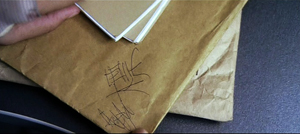

But, the Hollywood wisdom goes, don’t use a coincidence to develop or resolve the plot. Consider another Hong Kong film, Infernal Affairs (2006, directed by Lau and Mak, with script by Chong). Chan the undercover cop has come in from the cold. While officer Lau is out of his office, Chan is poking idly around Lau’s desk. There he finds the envelope on which Chan himself once scribbled a correction.

That envelope was in the hands of the gang that Chan joined. If Lau has that envelope, he must be the triad mole in the police force. This recognition triggers the film’s climax: Chan flees police headquarters and sets out to unmask Lau’s treachery.

You would think that if Hollywood filmmakers were anxious to avoid such a timely accident, the Infernal Affairs remake known as The Departed (directed by Martin Scorsese, script by William Monahan) would find another way for Billy Costigan to discover that Colin Sullivan is the mole. But no. Billy notices the telltale envelope sticking out from a pile of papers on Sullivan’s desk.

The different ways the two films drive the discovery home to the audience merit a closer look than I can spare here. My point is that the handy coincidence of the police mole leaving this damning clue for his adversary to find is used without apology in the Hollywood movie. And like its counterpart, the scene sets off the movie’s climax. You could even argue that Infernal Affairs supports its revelation a little better. Billy accidentally glimpses the crucial envelope, but Chan is actively browsing Lau’s desk, perhaps because after years spent among triads he doesn’t trust anyone .

So you have to wonder. Maybe filmmakers in many traditions have accepted the Chinese maxim. Moreover, contrivance of this sort doesn’t seem to damage a film’s reputation. (Many critics considered The Departed one of the very best US films of 2006.) More generally, we seldom feel such coincidences to be arbitrary or forced. Maybe screenwriters and directors have found ways to mask the coincidental tenor of such scenes.

As with our earlier Inception entry, we’re in the realm of motivation.

The roots of coincidence

Most story actions result from characters’ choices, purposes, reactions, plans, and the like. These factors create patterns of cause and effect. Chan/Billy didn’t just mosey into Lau/ Colin’s office: He came in because he thought it was safe to break his cover. We accordingly worry for him because we know, as he doesn’t, that he’s far from safe.

Everyone seems agreed that a plot can’t replace all causal connections with a string of coincidences. If everything happens by convenient accident, then we can’t form any expectations about what will happen next. And without expectations, our cognitive and emotional engagement with the story is likely to be slight. Moreover, designing a story packed with coincidences isn’t that hard. Children do it all the time. But most artistic traditions thrive on their constraints. If anything at all can happen to advance or conclude your plot, you’re playing tennis without a net. The interesting challenge for a storyteller in traditional forms is to create a pattern of incidents that arouses our curiosity, builds up suspense, and presents surprises that turn out to be, in retrospect, cunningly prepared for—all the while playing on our emotions.

Yet, and again: No coincidence, no story. Sometimes, the plot’s forward momentum needs encounters and discoveries not planned by the characters. So how can these convenient accidents be made to serve narrative craft?

Well, what is a coincidence anyway? At the least, it’s a matter of converging incidents, as the name implies; but surely it involves more.

I wake up one morning and ask, “I wonder what my sisters are up to? I haven’t heard from them in a while.” Nothing important is happening in the family, no health crises or upcoming reunions. I just wonder how the girls are. So I reach for the phone, but before I can dial I get a call from Diane (the Texas sister). I say, “What a coincidence! I was just going to call you.”

This sort of thing happens. But not all the time. Not even most of the time. The thousands of things that flit through our day almost never match up so nicely. And we don’t notice it when they don’t match up, because we don’t expect them to. The non-coincidences of everyday life go unregistered because they’re so pervasive.

On those rare occasions when things do sync up, we notice. In The Evolution of God, Robert Wright puts it well:

It makes sense that human brains would naturally seize on strange, surprising things, since the predictable things have already been absorbed into the expectations that guide them through the world; news of the strange and surprising may signal that some amendment of our expectations is warranted.

We usually attribute such coincidences to chance. But humans aren’t very good at thinking about chance. If the coincidence seems meaningful, as many do, we’re always tempted to consider it the result of some secret force. Did I send out invisible thought-waves that Diane somehow picked up? Did fate, or God, make her call me? In general, when we notice patterns, we look for causes. The phone-call convergence is a pretty minimal pattern, but even there we might be tempted to find a cause.

I hang up on Diane and the phone rings immediately. It’s Darlene (the peripatetic sister). “I was just trying to call you, David, but the line was busy.” This is getting weird. The pattern heightens and may prompt a stronger impulse to search for causes. Do we three siblings mind-meld in some mysterious fashion? (If so, though, why do we need phones?) It’s just a coincidence, highly improbable but, out of all the times we three think about one another and make phone calls, not impossible.

I believe that narrative artists in all media are practical psychologists. They trigger and exploit and heighten our ordinary ways of making sense of the world. Philosophers and statisticians have sophisticated ways of thinking about chance, but they needed special training to get beyond our folk psychology. Artists take us as we are.

Stories can use coincidences because we accept them. They are the sorts of things that sometimes happen, and so, as Aristotle argued, they are fit subjects for plot-making.

The poet’s task is to speak not of events which have occurred, but of the kind of events which could occur, and are possible by the standards of probability or necessity (Poetics, Chapter 9).

Here Aristotle points to two sorts of possible events. There are events that we expect to happen as a necessary result of earlier events; this corresponds to some notion of causality. Then there are events that are merely probable—things that are likely to happen.

But how likely is my call from Diane and the followup from Darlene? Aren’t these examples of what Aristotle dismisses as “the arbitrary and fortuitous”? Not necessarily, because for Aristotle too the storyteller is a practical psychologist. Things that seem unlikely, he says, can be motivated by reference to people’s beliefs or to the fact that improbable things are likely to happen occasionally.

Irrationalities should be referred to “what people say,” or shown not to be irrational (since it is likely that some things should occur contrary to likelihood) (Poetics, Chapter 25).

In sum, how do you motivate a coincidence? Aristotle recommends two tactics, which I could use if I were writing a story featuring the felicitous phone calls. People say that members of a family have a special affinity that can cross time and space. And anyhow, stranger things have happened.

Narrative norms

SPL.

Aristotle suggests a third motivational tactic as well. He says that unlikely things may be resolved “by reference to the requirements of poetry.” Poetry here refers to any verbal artform, just as poet refers to the maker of literary works in general. So what are the “requirements” of storytelling?

Most minimally, a plot needs an inciting incident. If I were a fictional character, my lucky phone calls might kick off a plot in which my sisters and I, feeling a new and mysterious bond, set out on road trips to meet somewhere. The telephone contrivance would correspond to the Hollywood dictum that coincidences are permissible at the outset of the plot.

Many commentators on Aristotle take his mention of poetic “requirements” to involve more specific conventions, especially those of different genres. We’ve long known that certain kinds of art works permit things that would be forbidden in other kinds. A children’s movie is unlikely to show chainsaw dismemberings, unless Eli Roth has been given a producing deal at Pixar. This idea of genre fitness or decorum has implications for coincidences too.

Clearly, coincidences flourish in comedy. The innocent young man trapped in a lady’s boudoir will have to hide under the bed because her husband bursts in at an awkward moment. In the long chase sequence through old Hong Kong in Project A (1983), Jackie Chan keeps bumping into his superior officer. Sometimes Jackie is set back by the encounter, but once the officer inadvertently rescues him. David Lodge writes: “Audiences of comedy will accept an improbable coincidence for the sake of the fun it generates.” His novel Small World culminates in a pile-up of coincidences in which an airline check-in clerk happens to give the heroine a copy of The Faerie Queene at the precise moment she needs to check a literary reference.

This is all highly implausible, but it seemed to me that by this stage of the novel it was almost a case of the more coincidences the merrier, provided they did not defy common sense, and the idea of someone wanting information about a classic Renaissance poem getting it from an airline Information desk was so piquant that the audience would be ready to suspend their disbelief.

Melodrama is another genre that relies on coincidences, particularly those that bring bad luck. (Think of Rock Hudson’s cliff-edge fall in All that Heaven Allows.) Likewise, I think that the revelations of the incriminating envelopes in Infernal Affairs and The Departed are partly motivated by genre conventions. In undercover tales, the detectives have to be alert for any physical items that might betray them or offer clues. So the envelopes are something that the hypersensitive narc could plausibly fasten onto. (Why the envelopes are left lying around in the first place is another part of the story, which I’ll come to.) Similarly, Initial D is partly a teenage romance, and we know that such films require an obstacle to happiness; that’s what Itsuki’s accidental discovery provides.

There’s another “requirement” of poetic art that can motivate coincidence, and it cuts across different genres. In Wilson Yip Wai-sun’s SPL (2005), a brutal martial-arts fight in a nightclub ends with the gangland chief Wong Po hurling Inspector Ma through a window far above the street.

Down below in a waiting car are Wong Po’s wife and baby son, the only things in life he loves.

Care to have a guess where Ma lands?

This is a coincidence motivated by poetic justice: The brutal Wong Po has inadvertently killed his wife and child. Serves him right!

As we might expect, Aristotle anticipated poetic justice too. He remarked that there was a special sense of fitness when the statue of a murdered man toppled over on his killer.

Three dimensions of narrative

Casablanca.

In an essay in Poetics of Cinema I argued that we can think of any narrative as having three dimensions: the story world, the macrostructure of the plot, and the narration–the flow of information as it’s presented, moment by moment, in the film. Each of these dimensions can motivate coincidence, and each answers to what Aristotle calls “requirements” specific to narrative art.

Say you want two characters to meet without making a rendezvous. One way is to establish that each has a routine. Jack stops for coffee at Starbuck’s every morning on the way to work; so does Jill. Sooner or later, it’s plausible that they will run into each other. The appeal to routine is probably behind the unlucky coincidence in I Corrupt All Cops. After being beaten, Unicorn staggers to the food stall across from his girlfriend’s apartment house–evidently on his way to call on her.

Another sort of story-world motivation involves characterization. In Initial D, it’s not implausible that the randy Itsuki would be hanging around outside a love hotel. Given his personality, he’s more likely to see Takumi there than other, more upright characters would be. In Infernal Affairs, Lau is a cautious mole, but he has no reason to hide the telltale dossier because he thinks it would be meaningless to anyone else. (Lau can’t know that Chan is the one who scribbled the corrected spelling on the envelope.) Lau’s studied nonchalance lets him stack papers on his desk without concern that this one is particularly revelatory.

Coincidence can also be motivated by the overall plot structure. If you start your film by alternating scenes showing two characters living their lives separately, you make it easier for your audience to accept what might otherwise seem a chance meeting between them later. After all, if they aren’t going to have some interaction, why are they both in this story? Sleepless in Seattle provides a clear-cut instance, although here the conventions of the romantic comedy genre also insist that the couple will get together. (Vera Chytilová’s Something Different of 1963 shrewdly defeats the expectation aroused by this sort of alternating construction.)

Likewise, a flashback structure can motivate coincidences. If we’ve seen the outcome of an action, even implausible events leading up to it can seem more natural. At the start of The Big Clock (1945) we see a hunted man hiding in a vast clock mechanism that surmounts a skyscraper.

In a long flashback, we see what led up to Stroud’s plight. Fired from his magazine job, he meets up with a blonde woman who takes him bar-hopping. They wind up in her apartment, but she hurries him out just as his boss Janoth comes in. Stroud watches Janoth go into the woman’s apartment.

The encounter isn’t wholly accidental. We know, as Stroud does not, that the woman is Janoth’s mistress, and she knows Janoth is coming to visit her. Nonetheless, what happens next leads to Stroud’s being fingered for murder. Stroud has pretty bad luck, but the opening frame story of his flight retroactively motivates his presence at the crime scene; we wouldn’t have the clock scene unless it proceeded, as Aristotle might say, by necessity from something pretty serious. The order of presentation coaxes us to accept whatever led up to the opening situation.

The story world and the plot macrostructure can do only so much. Sometimes coincidences need more fine-grained motivation. Here’s where narration, the patterned flow of information, comes in. If a cowardly cowboy is just about to leave the saloon when the bullying gunfighter enters, it can seem less stage-managed if we show, beforehand, the gunfighter riding into town with his minions. It doesn’t make the encounter more plausible in the story world, but it prepares us to find it more plausible: the two paths seem to converge. Here crosscutting accomplishes on the small scale what alternating scenes can do for macrostructure.

An even simpler tactic is to have someone announce that what’s happening is extremely unlikely. Lodge points out the audacity of Henry James in The Ambassadors when he presents a major moment through a character who reflects, “It was too prodigious, a chance in a million. . . ” This is the equivalent of Rick’s comment about Ilsa dropping into his gin joint. A frank admission of a coincidence can pull you through.

It was meant to be

Many of these motivating factors can work together with a more sweeping one. Recall that we’re sometimes tempted to consider everyday coincidence the result, or sign, of forces larger than we can comprehend–God, karma, fate, the Sibling Affinity Frequency. A narrative can motivate its coincidences by suggesting that they are working out an elusive but powerful pattern. Somehow, coincidence is just the hand of destiny. The French film known in English as Happenstance (2000) provides an example, but so does Serendipity (2001).

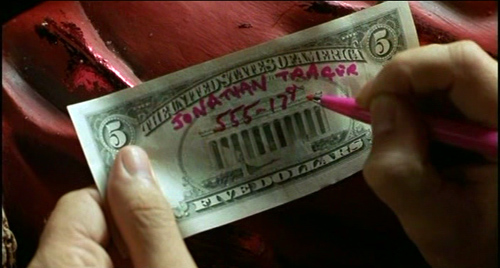

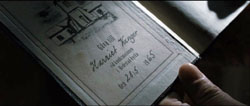

Jonathan and Sara meet cute in Manhattan, but mishaps separate them. They never learn each other’s identity. Years later, Sara is in San Francisco living with a musician, while Jonathan is about to get married. Vaguely dissatisfied and fretful, Sara returns to Manhattan to find Jonathan. Meanwhile, just before his marriage, he sets out to find her. Each one thinks that recapturing the love that flared up in one magical night would be worth one last effort.

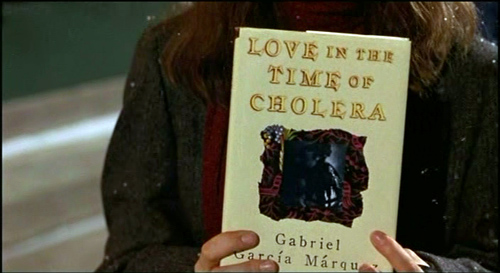

How do they find one another? Clues, plus coincidences. Jonathan starts to track Sara through a sales receipt for gloves she bought when they first bumped into each other. Sara returns to the Waldorf and visits “their” café in hope of finding some connection to Jonathan. But a lot of luck is involved too. Jonathan confirms Sara’s location thanks to her inscription in a used copy of Love in the Time of Cholera–a copy that his fiancée gives him, no less. By chance she bought Sara’s copy. Correspondingly, Sara finds the $5 bill Jonathan signed years before in her friend’s purse. Her friend got it as change at the café. The characters take purposive action, but they achieve their goals through coincidences.

These coincidences are simply outrageous. How can we motivate them? At the beginning of their magical night Sara announces that she believes that happy accidents are in fact controlled by fate. If she and Jonathan are meant to be together, things will arrange themselves the right way. She tells him this as they have coffee in her favorite café, Serendipity.

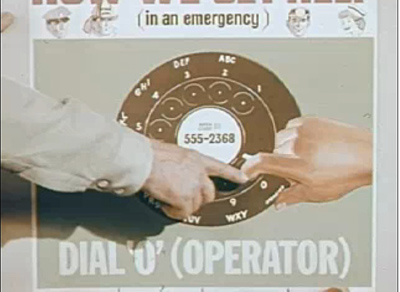

So Sara mounts some tests of their cosmic compatibility. She insists they leave the café separately: if they’re destined to remeet they will. Jonathan leaves his scarf behind, and she finds it, so they’re back together. She writes her contact information on a scrap of paper, but it blows away. “Fate’s telling us to back off,” Sara warns. Jonathan writes his phone number on the fiver, but she then pays for something with it, saying that if it returns to her, she’ll call him. In exchange, she’ll write her information in the Márquez novel and give it to a used bookshop; if he finds it, he can call her. Finally, at the Waldorf Astoria, each one is to get in a separate elevator car, pick a floor, and see if they’re in synch. It’s this test that leads him, through problems of timing, to lose her.

What motivates the cascade of coincidences, then, is the film’s starkly announced theme. In love, favorable coincidence is just serendipity; the film puts its operating procedure in Sarah’s mouth. To make your coincidences seem plausible, then, make your movie explicitly about how coincidences can be read as destiny.

But the theme doesn’t work on its own. Several of our other principles of motivation help out. For one thing we have Aristotle’s notion of common opinion: “What people say” about true love is that a couple is somehow meant for each other. In addition, of course, this is a romantic comedy, a kind of film that depends on separating and uniting lovers. We’d be very surprised, not to say disappointed, if these two didn’t wind up together. Genre helps motivate the way coincidences help out the couple.

Perhaps most interestingly, the “requirements of art” in Hollywood dramaturgy include a symmetrical play with motifs and character traits. Each lover is given a token—$5 bill, Márquez novel—and certain locales gain significance through repetition (Bloomingdale’s, the Waldorf, Serendipity, the skating rink). At the start of the film, Sara is the romantic, while Jonathan is more pragmatic. After a few years as a psychotherapist, however, she no longer trusts in fate. But by searching for her, Jonathan becomes a passionate believer in signs, reading everything around him as a possible trace of her presence. His pursuit of a love that defies likelihood moves his friend, the journalist Dean, to write a hypothetical obituary:

Even in certain defeat the courageous Trager secretly clung to the belief that life is not merely a series of meaningless accidents or coincidences. Uh-uh. But rather it’s a tapestry of events that culminate in an exquisite, sublime plan.

That plan is worked out through a traditional plot symmetry. Sara had found Jonathan’s scarf in the café at the start. At the climax, he discovers her jacket on a bench overlooking the ice rink where they shared their first date. (She had gone back there in a nostalgic mood earlier in the day.) Now, coming back for her jacket, she reunites with Jonathan. Hollywood’s use of tokens and props to develop the drama fits nicely with the theme of fate’s good offices. You could say that the vicissitudes of destiny are recruited to motivate some principles of classical plot construction.

Time out

You may dislike all the films I’m mentioning (Serendipity?! That’s a movie for wimps!). But my purpose here isn’t evaluative. I want to explore some principles that are used to make stories hang together, more or less. The same principles are present in what we sometimes call art films, from Bicycle Thieves to The Headless Woman. Coincidences abound in these movies, often motivated as the randomness of life, or n-degrees-of-separation, or mysterious larger forces that create correspondences (Paris nous appartient, the Three Colors trilogy of Kieslowski). Appeal to realism, to folk psychology, to genre, to thematic significance, and to formal unity can be found in virtually all narrative cinema. Here as elsewhere, I’m just trying to make such principles explicit and study how they work.

In thinking about those principles, I’m struck by one more way in which narratives need coincidences. What makes a story intriguing, or even worth paying attention to?

Here’s a story. I got up this morning, had breakfast with Kristin, went to school to take some frame enlargements from Hong Kong films, and dropped off the slides at a lab before coming home. Technically, it’s a story, but you yawned halfway through. To be engaging, stories need a remarkable situation or twist—a lover betrayed, a man pursued for a crime he didn’t commit, a cop discovering that his savior is his worst enemy, people who meet and fall in love and then lose one another.

We need, in short, something out of the ordinary. Coincidences, popping out from the bland backdrop of everyday life, can provide an uncommon event. At the start of a plot, they launch the action. At intervals, and with the proper motivation, they can be invoked if they liven things up. The effect may go back to the strangeness that Robert Wright suggests that we’re always on the lookout for.

Granted, the effect of motivation is to make coincidences seem less strange than they might otherwise seem. Most of these factors work to give the coincidences a sort of causal boost. Itsuki sees Natsuki because he’s at the love hotel, Chan/ Billy notices the envelope because he’s an alert cop, Jonathan and Sara get together again because they follow up clues and try really hard and anyhow an unseen hand (causally) shapes their fate, and so on. The coincidences are often covered by a causal alibi. That suggests that what’s most coincidental in these situations is timing.

Most movie coincidences run on tight schedules. A few moments later, Itsuki wouldn’t have seen Natsuki leave the love hotel; Unicorn wouldn’t have caught his wife with his boss; Chan/ Billy wouldn’t have found the telltale envelope; and so on. As the film unrolls, we want our extraordinary events tied to close shaves, barely missed messages, and revelations taking place under a ticking clock.

Every moment in filmic storytelling seems to bristle with possibilities of convergence and revelation. The sort of actions that make stories interesting are even more gripping if they take place under time pressure. Very often, if a key event had happened slightly earlier or later, there would have been no coincidence. And movies, unrolling at a pace to which we all submit, are well-suited to arouse our interest with turns of events that might, just barely, have been very different. Perhaps we accept the power of good or bad timing because, to recall Aristotle, “people often think” things like this: If I had missed that train, I would never have met my soul mate. . . .

Clearly, though, timing is a tale for another occasion.

My thanks to Ben Brewster for discussing these ideas with me and reminding me of the Chinese adage. That precept is briefly discussed in Kam-ming Wong, “‘No Coincidence, No Story’: The Esthetics of Serendipity in Chinese Fiction,” International Readings in Theory, History and Philosophy of Culture (St. Petersburg, Russia: EIDOS, 2003), Vol.16, 180-97.

My references to the Poetics come from Stephen Halliwell’s edition, The Poetics of Aristotle: Translation and Commentary (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1987), pp. 40, 42, and 63. My extracts from David Lodge’s The Art of Fiction (New York: Viking, 1993) are from his section on coincidence, pp. 149-153.

Hilary P. Dannenberg’s book, Coincidence and Counterfactuality: Plotting Time and Space in Narrative Fiction (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2008) includes many intriguing ideas about coincidence. Her focus is the “coincidence plot” in which people realize they’re related to one another. Some of her arguments are presented in more compact form in her article, “A Poetics of Coincidence in Narrative Fiction,” Poetics Today 25: 3 (Fall 2004), pp. 399-436.

P.S. 31 September: In a study of The Pledge, film scholar Gary Bettinson has a valuable discussion of how coincidence can be motivated to resolve a plot. It’s available here.

Serendipity.

Everybody’s Irish

Three Bad Men (1926) at the Piazza Maggiore; Orchestra del Teatro Communale di Bologna conducted by Timothy Brock. Photo by Lorenzo Burlando.

DB, still in Bologna:

The early Ford retrospective at Cinema Ritrovato rolls on. The surviving reel of The Last Outlaw (1919) proved very tantalizing. An end-of-the-West Western, it shows its grizzled hero revisiting the town of his youthful exploits. But now, in an anticipation of Ride the High Country (1962), civilization has taken over. Cars chase Bud off the streets and the theatre features movies (Universal Bluebirds at that, a bit of product placement). Ford heightens the contrast by letting us into the hero’s memory, introduced by the title: “Memories of the past flashing back to him”—the earliest reference to the term “flashback” I recall seeing in the movies.

The plot of Cameo Kirby (1923) involves a cardsharp who tries to help a southern family but whose chivalrous intentions are misunderstood. The film’s virtues were, I’m afraid, undercut by a choppy, contrasty print. Another 1923 vehicle, North of Hudson Bay (1923) was in much better shape. A fairly routine adventure about schemers trying to take over the gold claim of two brothers, it was enlivened by a mysterious murder scene, in which a man is shot before our eyes but we can’t say exactly how. Ford later replays the scene to clarify what happened, and then sets up suspense as the trap is put in play again, this time to kill our hero.

Kentucky Pride (1923) is a turf tale narrated by a racehorse. This might have become a tedious gimmick, but the film handles it with aplomb and modest emotion. Our narrator Virginia’s Future stumbles during the race, and the scene during which she is about to be shot generates a great deal of suspense and concern. At the end, her reunion with her son, Confederacy, is smoothly integrated into the humans’ reconciliations and just deserts. In between, Virginia’s Future passes from owner to owner, in something of a rough draft for the adventures of Bresson’s donkey in Au hazard Balthasar.

Kentucky Pride is a programmer, but between the peaks of racetrack excitement we get several arresting interludes. In one scene the now-destitute horse farmer reunites with his daughter. He’s at the dinner table. She comes up behind him and covers his eyes. So far, so conventional. But he raises his calloused, dirtied hands very slowly to touch her wrists. Prolonging the gesture shows not only Ford’s delicate way with such moments but the quiet skill of Henry B. Walthall; it’s impossible not to think of similar handwork in Griffith’s The Avenging Conscience (1914) and The Birth of a Nation (1915). The scene’s subdued pathos was enhanced by the accompaniment of Neil Brand, a Bologna regular.

Kentucky Pride is a programmer, but between the peaks of racetrack excitement we get several arresting interludes. In one scene the now-destitute horse farmer reunites with his daughter. He’s at the dinner table. She comes up behind him and covers his eyes. So far, so conventional. But he raises his calloused, dirtied hands very slowly to touch her wrists. Prolonging the gesture shows not only Ford’s delicate way with such moments but the quiet skill of Henry B. Walthall; it’s impossible not to think of similar handwork in Griffith’s The Avenging Conscience (1914) and The Birth of a Nation (1915). The scene’s subdued pathos was enhanced by the accompaniment of Neil Brand, a Bologna regular.

In another horsy tale, The Shamrock Handicap (1926), the financially challenged aristocrat is an Anglo-Irish lord , and to pay his taxes he sells some of his stable to an American racing entrepreneur. His top rider, Neil, goes along, leaving sweetheart Sheila behind. Once in the US, Neil takes a serious spill and acquires a game leg. Soon the aristocrat and his 120 % Irish household are coming to America to stake everything on racing their pride filly in the Handicap. The whole thing is a pleasant tissue of contrivance and coincidence, allowing Ford some chances for sentiment, camera tricks induced by ether, and gags on Irishness. The horse handler discovers that all his old friends and kinfolk in the New World have become cops.

There were opportunities to develop Sheila as more than a pretty face (that belongs to the enchanting Janet Gaynor), but the plot puts the menfolk to the front. The scenes of Neil’s acceptance in the hard-bitten jockey world show America as a place in which ethnic minorities hang together; his best friend is a Jewish rider who keeps a black valet. The characteristic Ford sadness surfaces in a lovers’ reunion. When Neil greets Sheila at dockside, Ford gives us a painful glimpse of wounded masculine pride. Neil stands waiting with his pals. Has he recovered?

As Sheila approaches, Neil swings his crutch abruptly away from her, as if to hide it. But the same gesture sharply reveals to us that he’s now lame.

In their embrace, the crutch falls away. Neil clutches Sheila as if she were not his sweetheart but his mother; he needs consolation, not passion.

The film may be about male pride, but as ever in Ford a man’s sense of self-worth is sustained by a touching reliance on women. So it’s fitting that the walking staff Neil leaves behind in Ireland–a slip in continuity, you might think–becomes his new crutch when he comes home again for good.

Lightnin’ (1925) moves not like lightning but at the pace of its elderly protagonist, Bill (Lightnin’) Jones. The opening is a drawling play with rustic humor, centering on Bill’s laborious stratagems to hide his whisky bottles from his wife. Bill isn’t Irish, but he might as well be, like the purported Welshmen of How Green Was My Valley (1941).

Initially the film seems to depend on one of those promising screenwriting switcheroos. The couple manage a hotel perched on the border between California and Nevada, so aspiring divorcées can collect their California mail and still maintain residency in Nevada. A dividing line runs through the center of the house, and it provides some adroit byplay when a young lawyer, pursued by corrupt businessmen, teases the Nevada sheriff by hopping from state to state. The romance between the lawyer and the old couple’s adopted daughter is handled briskly, with the usual repeated-and-varied dialogue motifs (courtesy Frances Marion’s script). One might expect a climax wringing comic confusion out of the divided household. But soon the border gimmick is forgotten and Ford moves to the emotional core of the movie, the testing of the old couple’s marriage.

When Mrs. Jones tries on a guest’s fashionable dress to find out what it’s like to wear nice clothes, Bill reacts obtusely. It’s his indifference as much as her decision to sell the hotel to land-grabbers that pushes her to sue for divorce. The climax is a prolonged trial scene in which Bill becomes his own advocate. As in later folkish tales like Judge Priest (1934) and The Sun Shines Bright (1953), plot dynamics take a back seat to horseplay and quietly detailed scenes of character reaction and reflection. Some laughs are milked from the family dog wavering between husband and wife, the judge flirting with a flapper, and the dimwitted drinking buddy with his two pudgy children. But soon Bill is fingering his Civil War medal as he slowly confesses his faults as a husband, and we recognize what we’d learn to call a pure Fordian moment.

Those were the days when you could make a film about old people.

For more on Ford, visit Tag Gallagher’s generous and wide-ranging website. It includes a revised version of his critical biography on the Skipper, as well as articles on many other filmmakers. For more Cinema Ritrovato photos, go here. For Gabe Klinger‘s rapid-fire Bologna updates, try Mubi. And for remarks on non-Fordian entries in this abundant festival, check in with us again soon.

Watching a movie, page by page

The Ghost Writer (above); The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo (below).

DB here:

Aristotle said, quite reasonably, that every plot has a beginning, a middle, and an end. But that doesn’t mean that every plot consists of three acts. Aristotle doesn’t mention act divisions in the Poetics for the good reason that classical Greek plays didn’t have them. The three-act play is just one convention that emerged in the history of storytelling.

As early as 20 BCE Horace was suggesting, “Let no play be either shorter or longer than five acts.” Influenced by this edict, Renaissance editors and playwrights adhered to five acts for many years. We have, of course, plays in two acts (Alan Ayckbourn’s Norman Conquest cycle) and four acts (Pygmalion, The Admirable Crichton, many of Chekhov’s). TV dramas are routinely divided into a teaser and four acts, broken up by commercials. All of those plots have beginnings, middles, and ends, so it’s silly to think that only the three-act structure can fulfill Aristotle’s dictum.

As early as the seventeenth century, the Spanish playwright Lope de Vega recommended three acts as best. In Europe, the format came into its own during the nineteenth century, evidently dislodging the five-act one. One reason may have been that three parts are architecturally simple, sturdy, and easily visualized. Around 1820 Hegel remarked: “Three such acts for every kind of drama is the number that will adapt itself most readily to intelligible theory.” What such a theory might look like was sketched by Lope, who anticipates modern advice manuals.

In the first act set forth the case. In the second weave together the events, in such wise that until the middle of the third act one may hardly guess the outcome. Always trick expectancy.

So proponents of the three-act screenplay formula should revise their pedigree. They’re actually pushing the Lope-Hegel tradition—which admittedly sounds less impressive than dropping the name of Aristotle.

Three acts, more or less

Despite the historical misunderstandings, there’s some reason to think that Hollywood screenwriters, and now filmmakers across the world, have followed a rough three-“act” scheme. Where they got this idea and when it started is still hard to say, but it’s been at the core of nearly every screenplay manual since the 1980s. Kristin and I have looked at this format from an academic perspective, and our views are outlined briefly on this site here and here and here. For more detailed arguments you can read her Storytelling in the New Hollywood and Storytelling in Film and Television and my The Way Hollywood Tells It.

In those places we’ve argued that Hollywood feature films tend to fall into chunks of 20-30 minutes. As a result a movie may display three parts, or four, or more (if the film is very long) or even two (if it’s unusually short). When the film has four parts, it tends to split the long second act that the manuals recommend into two.

A four-parter usually goes like this. A Setup lays down the circumstances and establishes the primary characters’ goals. The Complicating Action is a sort of counter-setup, modifying the original goals or creating new ones. At about the midpoint, there emerges a Development section characterized by delays, subplots, and backstory. There follows the Climax, which resolves the action by decisively achieving or failing to achieve the protagonist’s goals. The film typically ends with a brief Epilogue that establishes a settled state, happy or unhappy. Each of these sections is demarcated by a turning point—a moment of crisis, usually involving an unforeseen twist or a major decision by the protagonist.

Two recent films, The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo and The Ghost Writer, offer good examples of how the four-part template governs plot structure. I won’t walk through each one here, but both seem to me to adhere quite closely to this model. Today I’m more curious about the original novels. We know that books are routinely reshaped for movie treatment. Is there a sense in which the plot structure of the originals fits the film formula?

Fiction as film

I ask because some fiction writers have come to believe in the enduring power of the three-act structure for all narratives. In The Weekend Novelist (1994), Robert J. Ray recommends that aspiring writers use it (although he breaks Act II into two parts around the midpoint). He finds the pattern enacted in his book’s primary model, the novel The Accidental Tourist. “We’re working with the structure of [Anne] Tyler’s Tourist because it is classical, three acts” (142). This, Ray claims, follows “Aristotle’s dictum of beginning, middle, and end” (141). Ray makes a comparable suggestion in The Weekend Novelist Writes a Mystery (1998), naming the three parts Setup, Complication, and Resolution; a midpoint again splits “Act II.1” from “Act II.2.”

Ray’s are the earliest instances I’ve found of explicitly applying screenwriting structure to prose fiction. Later ones would include Stephen Greenleaf’s 1996 article “A Mystery in Three Acts” and James Scott Bell’s 2004 book Plot and Structure. Bell argues somewhat grimly that life itself has three acts: childhood, “the middle where we spend most of our time,” and “a last act that wraps everything up” (23). Ridley Pearson, in the 2007 article “Getting Your Act(s) Together,” tells us that the “three-act structure, handed down to us from the ancient Greeks [!], is one that’s proven successful for thousands of years” (67). “Name a film or book you think rises above others, and chances are, if you go back and study it, the story line will fit into this form” (85). Brenda Janowitz recommends plotting a Harlequin romance as if it were a movie like Mean Girls.

But screenwriting adepts will notice one thing that these advisors neglect: the lengths of the parts. The book that popularized the three-act structure in film circles was Syd Field’s Screenplay of 1979. Not only did he lay out the template, but he indicated running times for each section. Act 1 should last about thirty minutes, Act 2 sixty minutes, and act three about thirty. Assuming that one minute of screen time equals a page of the screenplay, that means that a two-hour movie should run about 120 pages. Field’s metric proved very influential, with script readers, producers, and writers all striving to find plot points at twenty-five minutes and ninety minutes.

To be strictly parallel, then, a “three-act novel” should be divisible into parts having a page ratio of 1:2:1. The only manual I know that is willing to bite this bullet is Writing Fiction for Dummies (2009). (The title has a catchy ambiguity, no?) According to the authors, Act 1 takes up the first quarter of the book, Act 2 the middle half, and Act 3 the last quarter (p. 147).

In the film versions of The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo and The Ghost Writer, the segments and timings fit the four-part model fairly neatly. (Try it yourself, in the theatre or when the films come out on DVD.) But what happens when we look at published books? Will we find what Ray found in The Accidental Tourist—conformity to the formula? Are practicing novelists using the template? Are the timings, or rather the page-counts, of the books congruent with the film model?

First I’ll consider Robert Harris’ novel The Ghost, the source of The Ghost Writer. The next section looks at Stieg Larsson’s The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo. If you want to avoid spoilers, skim and skip accordingly.

Ghost writers in the sky

The opening chapters of The Ghost introduce the unnamed narrator, a professional writer who is on the verge of breaking up with his girlfriend. Hired to ghost-write ex-Prime Minister Adam Lang’s memoirs, he is replacing Lang’s aide McAra, who drowned under mysterious circumstances. The Ghost takes the job just as news media are floating the charge that Lang helped the US ship British citizens to black sites to be tortured. The Ghost travels to join Lang, who is staying in America with his secretary Amelia and his wife Ruth. At his hotel, the Ghost encounters a surly British man who asks him pointed questions about Lang. This setup lays out the affair between Amelia and Lang, Ruth’s sexual jealousy, and the mounting political pressure on Lang, along with the sinister Brit in the bar. The section ends on p. 83 of the 335-page Gallery paperback edition, almost exactly one-quarter of the book.

The complicating action arrives when the Ghost’s first sit-down with Lang the next day is interrupted by the announcement that Rycart, former Foreign Secretary in Lang’s government, has asked the Hague to investigate the PM for war crimes. Under pressure from protestors, Lang decides to go to Washington for appearances’ sake. In the meantime, the Ghost discovers a set of clues McAra has left behind: photos of Adam in his Cambridge days, records and news reports of his party activities, and a mysterious phone number that turns out to be Rycart’s. All this creates a counter-setup. There is something foul afoot.

The Ghost ruminates constantly on McAra, a writer who has become something of a ghost haunting his successor. Soon the digital file of McAra’s draft of the memoir vanishes from the Ghost’s email. Most fundamentally, he discovers that in the first interview Lang has lied to him about how he got into politics.

That was when I realized I had a fundamental problem with our former prime minister. He was not a psychologically credible character. In the flesh, or on the screen, playing the part of a statesman, he seemed to have a strong personality. But somehow, when one sat down to think about him, he vanished. This made it impossible for me to do my job. . . . I simply couldn’t make him up (162).

At this point the protagonist decides on a new goal: to investigate on his own. This transforms his official assignment, and it happens on p. 163—quite close to the midpont of the book.

The development section is filled out with the usual delays, false leads, counter-maneuvers, and backstory. The Ghost’s investigation brings him to an interrogation of an old man who suspects foul play in McAra’s death, a sexual encounter with Ruth, a meeting with a professor with apparent CIA connections, and a suspicious vehicle in the vicinity. The turning point comes with another decision. “The more I considered it, the more obvious it seemed that there was only one course of action open to me.” The Ghost phones Rycart and flies to New York to meet him. This passage concludes on p. 256.

The climax sporadically unravels the clues McAra has left behind. In their meeting Rycart and the Ghost conclude that Lang was recruited by Professor Emmett during their Cambridge days and became a US puppet. Rycart has taped his exchange with the Ghost and uses that to force him to return to confront Lang. On Lang’s private plane, the Ghost accuses him but Lang’s denials are disconcertingly sincere. On disembarking, he is killed by a suicide bomber—the crusty Brit who blames Lang for the death of his son in Iraq. Although he’s haunted by dreams of a drowning McAra (“You go on without me. . .”), the Ghost plows ahead with Lang’s now-posthumous memoirs. All seems to have been settled until the book launch, when the Ghost discovers another way to interpret the evidence. He returns home to check McAra’s manuscript, where he finds a coded message identifying Ruth as the one recruited by Emmett; she was the mole. This revelation that the first solution was wrong, a detective-story device going back at least to Trent’s Last Case of 1913, arrives on p. 330.

An epilogue of only five pages reports that the Ghost is on the run. If anything happens to him, his former girlfriend will publish his story. “Am I supposed to be pleased that you are reading this, or not? Pleased, of course, to speak at last in my own voice. Disappointed, obviously, that it probably means I’m dead.”

The result conforms fairly strongly to the triple ratio: Act 1 runs 83 pages, Act 2 runs 173 pages, Act 3 runs 79 pages. Using the four-part template, we get 83/80/93/74, with a five-page epilogue.

Not perfect symmetry, but that’s hardly to be expected. Novelists stretch or compress as needed, and they can make scene boundaries a little fuzzier than what we find in films. For such reasons, other analysts might shift my breakpoints a few pages fore or aft. In addition, many films make the climax section somewhat shorter than the others, so we won’t always get perfect symmetry in novels either. Still, The Ghost offers a reasonably close approximation to the sort of plot template that we find in many commercial movies.

Double duty

Stieg Larsson’s The Girl Who Played with Fire provides a somewhat different sort of plot. We have two protagonists and three lines of action—two mysteries plus a search for revenge—or rather four, if you count the prospect of a romance between the protagonists. The book is also much longer than The Ghost, running 644 pages in the Vintage paperback edition I have. You might therefore expect more large-scale parts. But . . . .

The setup lays out the three major lines of action. Journalist Mikael Blomkvist, misled by an informant, publishes a false news story about the dealings of the businessman Wennerström. After Blomkvist is sentenced to prison, the second line of action kicks in: Henrik Vanger asks him to find what happened to his brother’s granddaughter Harriet. Meanwhile the neopunk hacker Lisbeth Salander is introduced as a security analyst researching Blomkvist for Vanger. By p. 138 Blomkvist has decided to accept the Vanger assignment. This section is not far from being a quarter of the text, and it corresponds to a major break, the end of Part 1 (“Incentive”).

The next large-scale section complicates things on two levels. It plunges Blomkvist into the details of Vanger family history and Harriet’s disappearance, and it brings Lisbeth Salander’s life to a point of crisis. We learn her past as an orphan and a denizen of the streets and hacker subculture, living under the thumb of her guardian Bjurman. This section is rather long, about 150 pages, because it has to establish Lisbeth as a dual protagonist and show her stratagems for escaping Bjurman’s sexual exploitation. Blomkvist must also serve his short prison time in this segment.

I’d argue that the plot’s midpoint occurs on page 323, halfway through the book. Chapter 16 begins:

After six months of fruitless cogitation, the case of Harriet Vanger cracked open. In the first week of June, Blomkvist uncovered three totally new pieces of the puzzle. Two of them he found himself. The third he had help with.

These revelations propel Blomkvist into a lengthy investigation of serial murders, which requires him to hire Lisbeth as his research assistant. While the two follow up clues, they start an affair.

On p. 477, it seems to me, the climax begins. The investigation has cast suspicion on Martin Vanger, Harriet’s brother. Blomkvist hears Martin returning home. “That somehow brought matters to a head.” Blomkvist goes out to confront him. Two pages later Martin shows him into the basement. “Blomkvist had opened the door to hell.” Now scenes of Lisbeth’s research and return to the village alternate with scenes showing Blomkvist at the mercy of Martin in his torture chamber.

Because the central plot involves two mysteries, the climax is extended. I’d argue that the two mysteries, the serial killings and Harriet’s disappearance, are solved by page 560 or so. But there remains the matter of Blomkvist’s revenge on the plutocrat Wennerström, who had tricked him into printing a phony story.

That dangling plotline is tied up in the next chunk (pp. 562-628), which forms in effect a second climax. Thanks to Lisbeth’s research, Blomkvist and his partners prepare to publish an expose of Wennerström’s crimes in Millennium. The evening that Blomkvist goes on TV, public opinion shifts decisively in his favor, and as the translation has it, “Blomkvist’s appearance marked a turning point.” He has won, and so has Lisbeth, who has drained money from Wennerström’s offshore accounts.

The sixteen-page epilogue tells us that Wennerström, facing disgrace and jail, kills himself. By now the two protagonists have struggled up from below. Blomkvist redeems his reputation and becomes the toast of journalism. Lisbeth, poor and victimized by men, becomes independent and enjoys her stolen fortune. There remains only the question: Will the two unite romantically? A final scene replies with a very old plot devices that’s one of Larsson’s favorites: a chance encounter that triggers a misunderstanding.

So I’m proposing a 138-page setup, a 150-page Complicating Action, and a 154-page Development. If you consider my two climaxes a single stretch, you have a 149-page climax section. That makes the big parts roughly equal, with a tailpiece of 16 pages. Even though The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo has nearly twice the page-count of The Ghost and crams in two protagonists and several plotlines, it displays the symmetry we find in the more compact book. The chief difference is between a comparatively short climax and a protracted one—the same difference we often find in classically constructed films. For these novels, and I suspect many others, the three-act/ four-part template provides a solid architecture for the plot.

Miracles, critical fantasies, or just tradition?

I won’t try to align the parts articulated in the novels with those we find in the finished films. The congruences are fairly close, once you grant that both films compress scenes and lop off characters and plotlines that are developed in the novels. Instead, I want to close by asking some questions.

Would novelists admit to consciously adopting this structure? If they don’t, or if we think it’s implausible that they would, we’re confronted with the charge that we’re simply projecting this structure onto the books. Are we and the writers of manuals shoehorning these plots into the three-act/ four-part format? Could we come up with equally persuasive patterns if we set out looking for seven or seventeen or seventy “acts”?

To take the last question first: Probably not. I think my analyses carve the films and books at the joints, more or less. One reason I like Kristin’s analytical method is that it hinges on characters’ goals and their pivotal decisions or reactions. These tend to be emphatic, well-articulated moments in the plot; a lot, as we say, depends on them.

True, there is some room to argue about which ones might be most far-reaching. You can propose alternatives, and I can change my mind. But the rival candidates for goals and decisions and major turning points aren’t likely to be radically different. We agree on most structural conventions, and our differences tend to be fine-grained, not gross.

Still, this sort of analysis arouses skepticism, and rightly so. How can writers and filmmakers achieve this neat structure without conscious planning? Can you follow the rules without doing so deliberately? Kristin offers an explanation that emphasizes the intuitive search for proportion in the creative process. She invokes Vivaldi concerti, medieval altarpieces, daily comic strips, and even the Great Pyramid at Giza as examples of balance among parts in both high and popular arts.

The evident use of proportions in many narrative films provides one more indication of the enduring classicism of the mainstream Hollywood system. Presumably what practitioners have intuitively assumed to be the optimum range of lengths for each part was discovered early on. It has been passed down the generations of filmmakers as a result of the simple fact that most practitioners gain their basic skills by watching a great number of movies (Storytelling in the New Hollywood, 44).

I think that there’s still a lot to learn about these templates. How are they disseminated among filmmakers? Why are we unaware of these parts while watching the film? They don’t stand out like chapter divisions in a novel. Or do we sense them subliminally? And how widespread are they? Do we find them in classic studio cinema of the 1920s through the 1950s? (Kristin thinks so, as do most writers of screenplay manuals.) Do we find them in films from other cultures and periods? If so, perhaps filmmakers elsewhere have found them to be reliable ways to engage viewers. Possibly these models were spread with the circulation of American movies.

I’ll provide my own epilogue by noting that the novelists’ borrowing of screenplay structures is a recent instance of a long-term process: the “cinefication” of other media. Today we call successful novels “tentpoles” or “blockbusters” or “locomotives,” and we say they’re “released” rather than “published.” What used to be called a series of novels is now likely to be called a franchise. It may be that many novelists have absorbed the lessons of screenplay manuals. If you wanted your book to be bought by a producer, why not make it like a film beforehand?

More abstractly, we have artistic transfer and technical influence. For a long time critics have argued that literary modernists like Faulkner and Hemingway, along with more popular genre writers, have tried for “cinematic” styles and have sought to imitate the “camera eye” in their narration. Today perhaps we see a structural influence as well: rules of film plotting mapped onto prose fiction. The next page-turner you read may have been engineered to flow across your eyes at the brisk pace of a Hollywood movie.

Several of my references to classical theorizing about act divisions are taken from Oscar Lee Brownstein and Darlene M. Daubert, eds., Analytical Sourcebook of Concepts in Dramatic Theory (Westport, CT: Greenwood, 1981). For more on classical Greek drama’s structure, go here. You can read a brief summary of the history of act divisions in western drama here.

On the three-act screenplay structure as applied to independent films, see J. J. Murphy’s You and Me and Memento and Fargo. See also J. J.’s independent cinema blog.

Stephen Greenleaf’s “A Mystery in Three Acts” appeared in The Writer 109, 4 (April 1996). Ridley Pearson’s article “Getting Your Act(s) Together” appeared in Writer’s Digest 87, 2 (April 2007), 67-69, 85. For another application of three-act structure to the novel, go here. The author claims that “movies rather than books are easier to analyze in that the main plot points are visual.”

On The Ghost Writer, a useful interview with Robert Harris is here. An entry on Creative Loafing points out ambiguities and vague spots in the movie’s plot. A January 2008 draft of the script, which incorporates voice-over narration, is available here.

The most influential account of how American novelists adapted cinematic techniques is Claude-Edmonde Magny’s Age of the American Novel: The Film Aesthetic of Fiction between the Two Wars. See also Keith Cohen’s Film and Fiction: The Dynamics of Exchange.

The Ghost Writer.

Festival as repertory

DB here:

This picture points backward and forward. It looks back to the days when movies were shown on a big screen to hundreds of people in real time. No pausing or fast forwarding; you take what you get. Some viewers are settled in pretty close to the screen, and a few dare to sit in the front row. (Save me the center seat, fortunately still vacant.) The critic sits slumped far back, implying coolly distant appraisal. The pen is poised to note down moments of power, beauty, or stupidity.

But the big auditorium is nearly empty, and this makes the drawing foreshadow the approaching end of moviegoing. The warning signs are emerging: Visit any movie, even an Imax spectacular, in the off-hours (Monday through Wednesday, especially matinees) and you’re likely to find the house as empty as it is here. As for the critic, ready to jot down notes for a review: An anachronism these days, as many will tell you.

But wait. Isn’t the theatrical business booming? We’re told that 2009 was a banner year, and 2010 will be even better. True, worldwide admissions for 2009 totaled $29.9 billion, a new high. But the increase, according to the MPAA, is mostly due to 3D. In the US, the format accounted for 11 % of the country’s $10.6 billion box-office income, a sum about equal to the gain over last year’s take. Moreover, the number of domestic tickets sold increased only a little from recent years, to 1.4 billion. Overall, the years 2005-2009 have fallen off from the high points of 2002-2004, when attendance was 1.5 billion or more.

Nor is the international film industry expanding its audience. For the last five years or so, worldwide attendance has been remarkably flat, with only the Asia-Pacific region seeing signs of growth. Overall, it seems, 3D serves to let Hollywood hang on to its audience, and charge more.

The spurt in theatrical income helps offset the decline of packaged media. The DVD sell-through boom lasted from 1998 to about 2008, when subscription rental companies (Netflix, Lovefilm) and kiosks (Redbox et al) pushed down retail sales. The slump was accelerated by a glut of DVD releases, big-box stores offering discs at rock-bottom prices, the rise of downloading and video on demand, and, not least, a massive recession that made consumers cost-conscious. Today, many industry observers think that young people are more inclined to graze in the luxuriance of YouTube than visit the multiplex. At best, the Millennials might watch a current hit streaming on their cellphones or laptops or TV monitor. An admittedly small-scale inquiry in the recent Screen Digest (April, p. 100; here, but proprietary) suggests that most young entertainment fans don’t feel a need to rent a disc, let alone buy one. Moreover, all those sampled saw far more movies on monitors, often through shady downloads, than on theatre screens.

It’s not hard to imagine a near future when a movie opens simultaneously on the global market to satisfy its most devoted public before moving in a very few weeks to DVD, VOD, iTunes, and other digital platforms. It then snuggles into hundreds of thousands of hard drives around the world, ready to be awakened when somebody feels the urge to watch. These seem to be the two poles we’re moving toward: the brief big-screen shotgun blast, and the limbo of everlasting virtual access. You can argue that the very success of home video, cable, and the internet have cheapened our sense of a movie’s identity.

Which is one reason why film festivals are very, very important.

Apocalypse then and now

I’ve spent most of the last several weeks at festivals. The Hong Kong International Film Festival is a 2 1/2 week showcase of global cinema, attached to a major regional market assembly and spiced with local attractions and international retrospectives. The Wisconsin Film Festival is a 4 1/2 day local event highlighting US independent cinema but with a leavening of recent arthouse titles and restored classics. Ebertfest, formerly Roger Ebert’s Festival of Overlooked Films, is a topical festival held in a single venue, featuring a wide array of guests, and reflecting its founder’s eclectic tastes.

Each offers unique pleasures, and each reaffirms the value of the theatrical motion-picture experience. I’ve already written a bit about Hong Kong here and here and here, and I hope to write more about the Wisconsin event soon. For now I’ll concentrate on a few high points of Ebertfest, which took Roger’s cartoon above as its emblem. Kristin and I have been guests for many years (our posts are in the Festivals: Ebertfest category on the right), but this time she was in Egypt scouring the sands for pieces of statues. So I’ve had to blog solo.

Fortunately, we now have a vast archive of what happened in Urbana. With the generosity typical of Roger’s event, all the Q & A sessions and panel discussions were recorded and streamed. They’re available here. And for an appreciative account of what it all means, see Jim Emerson’s piece on Roger’s site.

Start with the obvious. Apocalypse Now Redux was shown in a Technicolor restoration in the Virginia Theatre, a picture palace built in 1926. The image loomed, the sound engulfed you. Several people, most of them young, told me that they felt privileged to have seen the film, for once in their lives, as it must be seen. As soon as you get a home theatre that matches this presentation in sheer primal impact, call me. I’m coming over.

Editor and sound designer Walter Murch, one of my heroes, was prevented from coming by the European volcano ash. So I tried in my introduction to pay homage to what is surely one of the most complex soundtracks of any film of the period—a mixture of synthesizer, rock and roll, and layer upon layer of subtly enhanced noises. During the screening I was able to appreciate some of the daring soundfields Murch created. When Willard gets up to look out the blinds of his Saigon hotel, the sound in the left and right and surround channels narrows abruptly to the central speaker, bringing him back to mundane R & R reality. Later, most ordinary dialogue comes from the central speaker, but when Willard voices his commentary, we hear him from all three front speakers; the soft tone creates an intimacy, while the auditory spread gives it weight and authority.

A panel of commentators including Ali Arikan, Michael Phillips, and Janet Pierson did a fine job of probing various aspects of the film. Ali considers it Coppola’s crowning achievement and one of the great American films. Michael, by contrast, thought that what he aptly called the “terror and grandeur” of its opening half gives way to off-kilter and pretentious scenes in Kurtz’s compound. Janet, who had seen the film on the big screen more often than any of us, found it an enduringly impressive accomplishment in both sound and image. With the audience we had a lively exchange about the role of women in the film and the inclusion of the notorious French plantation sequence. Matt Zoller Seitz made a shrewd point about how the film shows Americans bringing along homegrown entertainments (Playmate performances, rock music, surfing) to redefine the war in familiar terms.

Despite all the shock and awe, I like the film only moderately. It’s a stunning logistical accomplishment, and it has some brilliant moments; but I think it has problems almost as soon as Willard moves upriver. I might be the only person who finds the Kilgore scenes overdrawn, almost Dr. Strangeloveish. When Kurtz bends down to give water to the wounded Vietnamese, he’s interrupted by news of surfing, and he yanks his canteen away as the VC scrabbles for it.

Heavy, heavy—as is the repeated motif of Americans strafing civilians and then tending to their wounds. Willard spells it out: “We cut them in half and then give them a Band-Aid.” Yet I still admire the utterly disorienting opening, which mixes thrumming choppers with ceiling fans and justifies what Michael Herr called it: the rock-and-roll war. Later we’ll see battles wreathed in psychedelic haze, and a hallucinatory assault on the bridge, with Willard stumbling through the dark and watching battle-fried infantrymen hurl ordnance into a void. It’s like a light show at the climax of a rock concert.

One of my favorite comments about the movie came during Dick Cavett’s television show circa 1980. Dick asked Jean-Luc Godard what he thought of Apocalypse Now. This was a period in which most of the press coverage obsessed about the film’s soaring budget. Godard remarked that Coppola had not spent enough. Cavett asked for an explanation. Godard: “Well, he spent only fifty million dollars and the war cost fifty billion. You cannot film this war on such a small budget.” That’s the way I remember it, anyhow.

From Rwanda to LA

Quick notes on two other E’fest titles. (I’ve already discussed Departures here.)

“I wanted to make a film for a Rwandan audience.” Not what you might expect to hear from an American director of Korean descent. Accordingly, Lee Isaac Chung gave Munyurangabo a leisurely pace and structure. The plot centers on two young men, Sangwa and Munyurangabo (aka Ngabo), taking what seems to be an enigmatic journey. One is Hutu, the other Tutsi. Longish takes and fairly distant framings follow them hitchhiking and stopping over at Sangwa’s home. Gradually, hints such as Ngabo’s carefully wrapped machete suggest that they are heading toward a confrontation. When the revelation comes, our attachment shifts from Sangwa and his family conflicts to Ngabo’s mission of vengeance. Chung explained that the soundtrack develops accordingly, moving from objectivity to subjectivity as we start to hear what his two protagonists hear.

The production background, explained by Chung and his colleagues Sam Anderson (co-writer and producer) and Jenny Lund (co-producer and sound recordist), was fascinating. The script consisted largely of a scene outline, and the dialogue was developed with the actors. The Americans worked with translators in guiding the performances. In some cases they drew on their own experiences. Perhaps partly because of its respect for everyday life, the film has been shown on local television and in the Parliament. It has become a Rwandan film.

My colleague J. J. Murphy has written an acute analysis of Munyurangabo. He rightly praises the sudden entrance of a bardic young man who recites a six-minute poem celebrating liberation and reconciliation. The performance wasn’t planned, Chung said, but it has become a high point of the film. J. J. also links to other enlightening interviews given by Chung, Anderson, and Lund.

If Munyurangabo’s loose structure evokes the Dardennes brothers, Michael Tolkin’s The New Age has the coiled-serpent dramaturgy of a classic psychodrama-comedy. It’s 1994, and a prosperous LA couple is suddenly without income. Facing bankruptcy, Katherine and Peter auction off their paintings, try to borrow from Peter’s father, and eventually open a boutique catering to the tastes of their friends. At the same time they slide into casual affairs and ceremonies of New Age spirituality. Ebert’s review captures the movie’s range of reference:

Tolkin gives us one richly detailed set piece after another, involving luncheons, openings, massages, telephone tag, psychic consultations, sex, heartfelt conversation, and pagan rituals led by a bald-headed woman who sees what others cannot see. Meanwhile, the material universe remains the one thing Peter and Katherine can really count on.

Few American films examine money and class, but this one is actually about needing a paycheck. By the end, when each of our protagonists becomes a seller rather than a buyer, we have seen a remarkably sharp dissection of a lifestyle.

In the Q & A afterward, Tolkin said that the genesis of the film came from watching a Melrose shop sink into failure. When I saw the film on its initial release, lines like “It’s not an insult, it’s an intervention” and “We need space” (psychological, but also retail) leaned me toward taking the film as satire. I still do. But Tolkin insists that it’s not. The plot dares to have two truly repellant protagonists, but Tolkin doesn’t find them nasty. “I like them.” He majored in religion in college and he takes his characters’ beliefs, no matter how shallow, seriously—not a big surprise from the creator of The Rapture.

He elaborated on some differences between novels and films. When he rereads one of his novels, he thinks, “How was I ever that smart?” but when he rewatches a film it’s the imperfections that jump out. A movie has to be more compressed and rhythmically varied than a novel—something The New Age demonstrates in its brisk montages alternating with slowly unfolding scenes. In the discussion Jim Emerson praised the film’s density of detail, Tolkin elaborated by invoking William Carlos Williams’ belief in compact expression.

The next two paragraphs include plot details you may prefer to pass over.

Tolkin’s script is indeed firmly contoured. The couple’s crucial quarrel takes place at the thirty-minute mark and launches the two major plot lines. They decide to try a separation (while sharing the house), and they launch their boutique. The development section begins about halfway through, as they conduct their love affairs and watch the shop founder. The last act presents their options: bankruptcy, suicide, low-end work.

Arguably the climax is Peter’s desperate effort to make his first telemarketing sale. Here, I think, Tolkin’s ambivalent sympathies come out. Early in the film Peter had asked a cold-caller whether he ever thought he’d be doing this as a career; it’s less a moral condemnation than glib snobbery. But when Peter has to close the sale, his self-loathing is mixed with a certain pride. The cashiered ad exec finds that he can do this. He’s on the road back.

The gorgeously designed movie, with hard blacks and saturated primaries, has a developing palette (“swatches for each act,” Tolkin says). Unhappily, I can’t study the design arc here because The New Age seems never to have had a DVD release. So much for the Celestial Multiplex. Good old 35mm pulled us through, in a radiant print.

Scholars seem now to agree that film festivals serve as an alternative international distribution system. Like Hollywood’s more formal and routinized machine, festivals bring movies to audiences. Usually the movies are current ones, and a festival is offering local viewers their only chance to see such pictures before video release.

Ebertfest shows that there’s an essential place for what we might call the repertory festival. That’s one that revives and reappraises films from earlier periods—and “earlier” may mean only a few years ago. Jumping from 1929 (Man with a Movie Camera, accompanied by the Alloy Orchestra) to the 1980s (Apocalypse Now, Barfly) and the 1990s (The New Age) and then right up to 2008 (Vincent, Trucker, Departures, Synecdoche, New York, Song Sung Blue), this year’s edition reminds us that every film, old or new, is a part of history.

To come fully into history, I’m convinced, a film needs scale. Even intimate dramas attain their true gravity when spread out like a gigantic picnic on a pale blanket. It’s not the only way to enjoy cinema, certainly; but it’s one that we must never abandon. Like the note-taker in the back row and the geeks up front, everyone needs a full view.

Apocalypse Now Redux.

PS 28 April: I just discovered this piece by Steven Zeitchik, who argues that reviving classics in a big-screen event format could also be good business.