Archive for the 'Screenwriting' Category

Manhattan: Symphony of a Great City

DB here:

In December Kristin and I attended a wide-ranging conference at Rome University devoted to “Exploded Narration”—the effects that digital technology has had on storytelling in film and television. As our host Vito Zagarrio put it, the question is one of continuity or rupture. Have new formats like HD, the Internet, and DVD revolutionized media storytelling? Or are they serving traditional approaches?

Many papers explored the “rupture” option, while Kristin and I offered presentations that emphasized continuity. You can find one version of my argument elsewhere on this site. Still, both of us also pointed up some innovations, or what I called “spillover” effects. As so often with such questions, the answer turned out to be complicated.

We enjoyed the conference, and one standout aspect was the presence of Amos Poe. Poe is probably best known for his first feature, Alphabet City (1985), and for his 16mm film on the Punk scene, The Blank Generation (1976). His Triple Bogey on a Par Five Hole (1991) has also attracted attention. For three decades Poe has worked as a director, producer, screenwriter, and teacher. The Sundance festival is playing Amy Redford’s The Guitar, which Poe wrote and coproduced.

We enjoyed the conference, and one standout aspect was the presence of Amos Poe. Poe is probably best known for his first feature, Alphabet City (1985), and for his 16mm film on the Punk scene, The Blank Generation (1976). His Triple Bogey on a Par Five Hole (1991) has also attracted attention. For three decades Poe has worked as a director, producer, screenwriter, and teacher. The Sundance festival is playing Amy Redford’s The Guitar, which Poe wrote and coproduced.

Amos was great fun. A soft-spoken man with a quick and wicked sense of humor, he enlivened our dinners at various ristoranti. He also spoke extensively about screenwriting, which he teaches at NYU and at NYU’s Florence program. Like many screenwriters, he’s extremely intelligent and articulate about his craft. Three examples:

*How to learn screenwriting? Get a script version of a film you admire. Read the first ten pages, then closely watch the first ten minutes of the movie. Go back and read the next ten pages, and go ahead and watch the corresponding ten minutes. And so on until the end. Do this with three first-rate films, and you will have a concrete, intuitive understanding of how a screenplay works.

*A screenplay, Amos points out, isn’t a short story or novel or play. It’s a movie in words. It must make the reader see and hear an imaginary film, and not only the action, either. Without indicating specific shots, the descriptions should suggest the flow of long-shots and close-ups (”Her lipstick leaves a smear on the cigarette butt”). “The screenwriter is a filmmaker.”

*Write sounds into the background of scenes, setting them up for fuller presence later. If a train becomes important late in the story, mention the wail of a distant train early in the screenplay. This sort of auditory planting quietly strengthens the structure of the story in your reader’s mind.

Amos must be a terrific teacher. I learned a great deal from his descriptions of contemporary film conventions, several of which I hadn’t noticed before. Don’t be surprised to find some of them creeping into future blogs.

Given Amos’ expertise in mainstream storytelling, the film he presented was quite a surprise. It’s called Empire II, and though you don’t normally call a three-hour movie a delight, I can’t think of a better word. After a week of tourism and no films, it was just the sensuous boost that my hungry eyes needed.

Man with a Video Camera

Poe’s apartment on Christopher Street yields a stunning view of the Manhattan skyline—the Chrysler Building, Jefferson clock tower, and of course the Empire State Building. He planted a Sony PD150 video camera at his window for a year, from 1 November 2005 to 31 October 2006, and took time-lapse shots. Through single-framing, he captured a total of 1 or 1 ½ seconds of every thirty seconds of real time. He shot traffic, people, skies, and the horizon. He did not look at the footage until after the year was up.

He wound up with sixty hours of imagery. He then made an absolute gesture. Using Final Cut Pro, he compressed all sixty hours into three. What was already highly elliptical, a string of tiny slices of action, became enormously accelerated.

Poe and his students then spent months blending up to forty tracks of music, spoken verse, and sound effects. It’s a crisp stereo mix, with remarkable audio-visual correspondences: whipping wind and ticking machinery sync up with snow and the tower clock. The music, which ranges from alt-rock to Keith-Jarrettish piano strumming, works sympathetically but not redundantly with the imagery. (No surprise that Poe has made music videos.) Shooting the film cost virtually nothing, but Poe spent about $100,000 for music clearances, though old friends like Patti Smith and Deborah Harry gave him their material for free.

The result is a city symphony, a lyrical tribute to the looks and sounds of New York. It joins the tradition of Walter Ruttmann and Dziga Vertov, as well as Paul Strand’s Manhatta (1921) and Jay Leyda’s Bronx Morning (1931). It also reminds you that Poe has roots in the downtown avant-garde. In 1972-1975, he often watched works by Jonas Mekas, Stan Brakhage, Michael Snow, Bruce Baillie, and Jack Smith at Millennium Film Workshop, and he made films for its Friday night open screenings. As a result, Empire II carries premises of lyrical and Structural cinema into the digital era.

The conditions of production are at once subjected to strict guidelines—a single year, only views from the window, the 20x compression—and open to chance. As with the films of Ernie Gehr, chance becomes more felicitous when set within a rigid frame. “I needed to create a base for accidents to happen.” Poe refused to cut or rearrange what he had (”I don’t edit unless I get paid for it”) and so he was ready to accept what came out. “I had to let go of the result.” That result mixes smoothness and fracture; the moon arcs like a golf ball, but traffic hammers relentlessly in a way recalling the last sequence of Man with a Movie Camera. Every so often there are calm islands of blank frames, provided by Poe’s occasional neglect to set focus or exposure.

Poe’s Book of Hours and Days

The title pays homage to Warhol’s 1964 film, so often discussed and so little seen. In many ways, though, Poe gives us an anti-Empire. Instead of a silent film, sound, both aggressive and immersive. (The stereo tracks shoot noises bouncing across channels, swallowing you up.) Instead of a single night, a year’s time span. Warhol shot Empire at 24 frames per second but insisted on projecting it at 16, slowing up time; Poe’s single-frame sampling and frantic acceleration speed time up. Warhol used for the most part a single camera position and shot in long takes, but Poe presents a flutter of shots. The framing is steady, but what we see flickers and pulsates, creating superimposition effects comparable to Ruttmann’s and Vertov’s slashing diagonals.

Warhol was withdrawn and impersonal, but Poe turned on the camera when he spotted something that looked interesting. He felt free to focus, reframe, zoom, and shift camera position for different angles on the life beyond his balcony. Likewise, the automaton Warhol (”I’d like to be a machine”) is counterposed to Poe’s more organic sensibility. He never lets us forget the flowers twitching on his windowsill, and their growth and rearrangements become traces of his daily life in the apartment.

The rules are simple and viewer-friendly. We instantly recognize the trappings of city life; we know the cycles of the seasons and the shifts between night and day. This cogent structure throws all our attention on what we see from moment to moment, and how we see it.

The Empire State Building and the skyline around it, along with the flowing clouds, remain stable reference points for a flurry of visual transformations. The taxis and pedestrians we glimpse move in jagged, incomplete rhythms very different from the smooth flow of fast motion in Godfrey Reggio’s films like Koyaanisqatsi.

As you see, high angles, plays of focus, and tight framings provide energetic abstraction. Flaring exposure makes the Building look like it’s in flames, triggering echoes of the 9/11 attacks.

When the weather changes, the light does too. Raindrops become not only a pebbly surface on the windows but tiny filters. As with Warhol’s films, we have to change our conception of what counts as an event. Slight differences of framing and texture become visual epiphanies. Rain can be gray-green, and snow can go pale red. At times, the steeple clock face in the lower right becomes an imperturbable timekeeper, a sort of pictorial timecode, reminiscent of the clock in the corner of the shots of Robert Nelson’s Bleu Shut (1971).

Spring comes about halfway through. It’s as lyrical as you’d expect, but again the colors startle. If snow can be red, then budding trees can be blindingly white.

As in Ives’ Holidays Symphony, the festive iconography of Americana is made somewhat dissonant. July Fourth fireworks become splinters, and the slurred, jerky figures in the final Halloween chapter recall Mekas’ Notes on the Circus. Now shooting more continuously, with handheld shots and bumpy pans and zooms, Poe lets his 20x compression turn the parading ghosts, skeletons, nuns, and dark angels into scurrying hallucinations, complete with cellphones.

Empire II is at once exuberant and tranquil. What a pleasure to find a film devoted simply to seeking out beauty in everyday surroundings. “She celebrates the small,” sings Jimmie James while we see snow lashing the sidewalks. So does Poe. He has said that he made the film at a difficult period of his life, but what he has given us, I think, is jubilation.

PS 22 Jan: For more on Empire II, including a trailer, go to amospoe.com.

Live with it! There’ll always be movie sequels. Good thing, too.

DB:

You’ve heard it before. Facing a summer packed with sequels, a journalist gets fed up. This time it’s Patrick Goldstein in the Los Angeles Times, and his lament strikes familiar chords. Sequels prove that Hollywood lacks imagination and is interested only in profits. Sequel films are boring and repetitious. They rarely match the original in quality. And when good directors sign on to do sequels, they get a big payday but they also compromise their talents.

Me, I want more original and plausible ideas. So, I expect, do you. Time to call in the Badger squad, the ensemble of email pals drawn from various generations of UW-Madison grad students and faculty. I asked them if we can’t understand sequels in a more thoughtful and sophisticated way—historically, artistically, in relation to other media. The result is another virtual roundtable, like the one on B-films held here a few months ago.

There were enough ideas for several blogs, and I’ve regretfully had to drop a whole thread devoted to comics and videogames. Maybe I’ll compile those remarks into a sequel. For now, the participants are: Stew Fyfe; Doug Gomery; Jason Mittell (of JustTV); Michael Newman (of Zigzigger and Fraktastic); Paul Ramaeker; and Jim Udden. I throw in some ideas as well.

Are all sequels in the arts automatically second-rate?

DB: The Odyssey is a sequel to the Iliad, and the second, better part of Don Quixote is a sequel to the first. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings trilogy is explicitly a followup to The Hobbit. After killing off Sherlock Holmes in “The Adventure of the Final Problem,” Conan Doyle resurrected him for more exploits. The Merry Wives of Windsor brings back Sir John Falstaff after his death in Henry IV Part II, because, supposedly, Queen Elizabeth wanted to see him again, this time in a romance plot.

Michael Newman: Sequels exist in all narrative forms–novels, plays, movies, television, videogames, comics, operas. What is the Bible but a series of sequels? Didn’t Shakespeare follow up Henry IV with a part II? What of Wagner’s Ring Cycle and Updike’s Rabbit novels? Many novelists of high reputation have written sequels, including Thackeray, Trollope, Faulkner, and Roth. There is nothing intrinsically unimaginative about continuing a story from one text to another. Because narratives draw their basic materials from life, they can always go on, just as the world goes on. Endings are always, to an extent, arbitrary. Sequels exploit the affordance of narrative to continue.

What about film sequels? What’s their track record?

DB: Goldstein grants the excellence of Godfather II, but what about Aliens, The Empire Strikes Back, Toy Story 2, and Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (arguably the best entry in the franchise)? We have arthouse examples too, provided by Satyajit Ray (Aparajito and The World of Apu), Bergman (Saraband as a sequel to Scenes from a Marriage), and Truffaut (the Antoine Doinel films). If we allow avant-garde sequels, we have James Benning‘s One-Way Boogie Woogie/ 27 Years Later. As for documentaries, what about Michael Moore’s Pets or Meat?, the pendant to Roger and Me?

The world of film would be a poorer place if critics had by fiat banned all the fine Hong Kong sequels, notably those spawned by Police Story, A Better Tomorrow, Drunken Master, Once Upon a Time in China, Swordsman, and so on up to Johnnie To’s Election 2 and Andrew Lau’s Infernal Affairs 2. And arthouse fave Wong Kar-wai hasn’t been shy about making sequels.

Stew Fyfe: Other sequels of quality: The Bride of Frankenstein, Mad Max II (The Road Warrior), Spider-Man 2, X-Men 2, Dawn of the Dead, Sanjuro, Quatermass and the Pit. Personally, I’d also add Blade 2, Babe 2 and The Devil’s Rejects, but I’m sure those are arguable. Would The Limey be a sequel to Poor Cow? Del Toro speaks of Pan’s Labyrinth as a companion piece or “sister-film” to The Devil’s Backbone. If you want to include docs, there’s always the Up series.

Why are there film sequels in the first place?

DB: Most film industries need to both standardize and differentiate their products. Audiences expect a new take on some familiar forms and materials. Sequels offer the possibility of recognizable repetition with controlled, sometimes intriguing, variation. This logic can be found in sequels in other media, which often respond to popular demand for the same again, but different. Remember Conan Doyle reluctantly bringing back Holmes, and Queen Elizabeth asking to see Sir John in love.

Doug Gomery: Sequels happen because the studio owners have never figured out any business model to predict success. If #1 is popular, perhaps #2 will be almost as popular. Until recently, producers seldom expected the followup’s revenues to equal the first. The basics were keep costs low, keep risks low, and make a profit. Maybe not a large as the breakthrough initial film—but at least a profit.

But they’re not a contemporary development. As part of the Hollywood studio system, they have existed in all eras—the Coming of Sound, the Classical Era, and the Lew Wasserman era. They surely seem to be surviving Wasserman as well. Indeed, as much as I admire Wasserman, who can defend Jaws 2 and its successors?

In the classic era, it may seem that there were fewer sequels as such, but there was a variant called rewrites in another genre. Years ago as I did my first book, a study of High Sierra, I watched Colorado Territory with something close to awe. It’s a gangster film turned western almost line by line. After all, Warners owned the literary rights: why not recycle it?

Given the mercenary impulse behind sequels, does a director’s willingness to make one mean that he or she has sold out?

Goldstein: “Look at the great talent who’s on the sequel beat: Steven Soderbergh has done two Ocean’s sequels. Bryan Singer, the wunderkind behind The Usual Suspects, has done X-Men 2 and is at work on a sequel to Superman Returns. Christopher Nolan has left behind the raw originality of Memento to do Batman movies. Robert Rodriguez, who burst on the scene with El Mariachi, has done two sequels for Spy Kids, with a Sin City sequel on its way. After making Darkman and A Simple Plan, Sam Raimi seemed poised to be our generation’s dark prince of meaty thrillers but has turned himself into an impersonal Spider-Man ringmaster instead.”

Paul Ramaeker: To assume that the Spider-Man films must necessarily be less personal than Darkman or A Simple Plan (both of which are heavily indebted to the strictures of their genres) is to perpetuate a culturally snobbish perspective on comic books. I’ve not seen S-M3, but Raimi is a genuine fan of the character, a character with a long and complex narrative history, and given the way S-M2 continues and develops threads from the first film, I see no reason to assume he didn’t have some artistic investment in presenting his interpretation of the character over 3 films (or however many) to present a larger “story” about the character. Why should this not be seen as “personal” filmmaking to the same extent as any other kind of adaptation?

Moreover, speaking as a Soderbergh fan: I may not like Ocean’s 12 as much as Ocean’s 11, but it seems like an experiment made in good faith to me. It is a stranger movie than you would think from the way it gets picked up in articles like Goldstein’s. In fact, the way it plays with audience expectations is both dependent upon familiarity with the first film, and radically divergent from it- in many ways, it does the exact opposite of what sequels are supposed to do, which is to provide a “cozy” (Goldstein’s word) repetition of familiar pleasures. Perhaps it failed (again, I remain sort of fond of the film, which I think was best described as being like an issue of Us Weekly as put together by the editors of Cahiers du cinéma), but even so I think you’d have to call it a failed experiment rather than a rehashing.

Stew Fyfe: At a guess, I’d say that audiences or critics might evaluate the worthiness/mercenary nature of sequels by asking three questions:

(1) Has the sequel been made because there’s more story to tell?

(2) Has the sequel been made because the characters are great and people want to see them again?

(3) Has the sequel been made because there’s more money to be made?

Obviously, any combination of all three can be answered in the affirmative for any sequel and presumably the sequel wouldn’t get made if the answer to (3) was No. But with something like The Two Towers, (1) gets priority, while with Pirates 2 + 3, (3) nudges out (2). Even with (3), money, as the primary motivation, one could still make a good film. The suspicion of milking the franchise just makes the movie an easier target for critics.

Do sequels automatically equal predictability?

Jason Mittell: The line that most interests me in Goldstein’s piece is the last: “When it comes to entertainment, I’ll take excitement and unpredictability over familiarity every time.” This sets up a false dichotomy between the known and the unknown. As David and I both blogged about a few months ago, knowing a story doesn’t preclude suspense and excitement (and for some viewers, it might actually enhance it). And arguably knowing a storyworld actually allows for greater opportunities for excitement and unpredictability – a film/episode/entry in any series that doesn’t need to spend much time introducing already-established settings, characters, conflicts, etc. can literally cut to the chase. Think of the second Bourne film as a good example, or Spider-man 2 as a chance to deepen character once basic exposition is accounted for.

Paul Ramaeker: I have a theory. In the contemporary comic-book blockbuster, the sequels will always be better than the first entries. Spider-Man 2 is better than Spider-Man, X-Men 2 is better than X-Men, and I will bet that The Dark Knight will be better than Batman Begins, just as Batman Returns was better than Batman. The pattern seems to me to be that the first film in the series is relatively impersonal—the franchise must be established as a franchise, meaning that few boats will be rocked, and the director must prove that they can handle both a film on that scale, and can be trusted with the property with all the investment it represents.

But once they’ve done so, in the above cases where the first films enjoyed significant economic (and critical) success, the directors are given a bit more leeway, are allowed to drive the family car a little further and a little faster. In each case, the second film in the series by the same director has been significantly more idiosyncratic. Batman Returns has much more of Burton‘s sense of humor and interest in the grotesque; X-Men 2 is a much more serious and ambitious film narratively and thematically, more obviously the product of a prestige filmmaker (Singer’s never been an auteur by any stretch, so that will have to do). Spider-Man seemed sort of anonymous in terms of style, but Spider-Man 2 had a much more extensive and playful use of classic Raimi techniques: short, fast zooms; canted angles; rapid camera movements; whimsical motivations for techniques, like the mechanical-tentacle POV shot (virtually a repeat of his flying-eyeball POV from Evil Dead 2).

Who knows what The Dark Knight will be like, but I’m prepared to put money on the claim that it will have something to do with how people construct elaborate narratives around themselves to explain, justify, or obscure their actions and motives.

Are sequels part of a larger trend toward serial narrative?

DB: We can continue a story in another text within the same medium, but we can also spread the storyline across many platforms—novels, films, comic books, videogames. Henry Jenkins has called this process transmedia storytelling.

Michael Newman: Compared with literary fiction, there seems to be a strong propensity toward the never-ending story in genre storytelling like sci-fi and fantasy and superhero comics and spy novels and soap operas. Much of the cinematic sequel storytelling today might be considered as this kind of serialized genre storytelling. Such serials tend to have a low aesthetic reputation in comparison to more respectable genres. (The cinematic comparison would be summer blockbusters vs. fall Oscar bait.) Serial forms have historically been associated with children (e.g., comic books) and women (e.g., soaps). In other words, there is cultural distinction, a system of social hierarchy, at play.

Stew Fyfe: Yes, the longer-standing comics universes have made regular use of serial continuity to forge after-the-fact connections. It’s a form of what fans call retcon or “retroactive continuity.”

Sci-fi writer Phillip Jose Farmer used a similar concept, the “Wold Newton family” to link various mystery, pulp, crime, sci fi, adventure and spy fiction characters (so that Sherlock Holmes, Doc Savage, Sam Spade, The Shadow, Captain Blood and James Bond, among others, all become linked). Alan Moore did something similar with The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, and Warren Ellis in Planetary. More limited filmic examples of this might be Zatoichi vs. Yojimbo, or Enemy of the State (which more or less sticks The Conversation‘s Harry Caul into a Bruckheimer film). There’s Freddy vs. Jason, which very adroitly observes and incorporates the continuities of two long-standing, mostly dormant franchises. In television, there’s that whole, rather insane St. Elsewhere continuity thing.

In the current crop of movie sequels featuring superheroes, one thing that has been noticeable is the casting of minor characters who might serve as springboards for later storylines. We’ve seen Dylan Baker play Dr. Connors in two Spidey films, for example, so if they decide to go with The Lizard as a villain in one of the later films, they’ve already set him within the film series’ continuity. Aaron Eckhart’s casting as Harvey Dent in The Dark Knight could similarly be used to set up Two Face as a villain for film 3.

This is similar to the idea of leaving a film “open for a sequel,” but it seems more closely integrated into the planning and execution of the film. It also points to a middle ground between the “We’re going into this making three unified films” model (Lord of the Rings) and the “We can make more money, so let’s see what plot elements we can build off of” (Pirates of the Caribbean). This is more of a “We’re probably going to make more films, let’s give ourselves something to work with” model.

It also raises the question, I guess, if you want to start speaking of dangling causes extending past the end of a film, or in the case of Pirates, the conversion of plot elements into something like dangling causes. In Pirates 1, we hear of Bootstrap Bill Turner getting chained to a cannonball and shot out into the ocean, but wasn’t it after he was made immortal by the curse of the Aztec gold? I guess you could call this a retroactive cause. Or, noting the similarity to “retcon,” a “retcause.” Never mind, that sounds lame.

Michael Newman: In the contemporary era of media convergence, serialized storytelling is becoming a mainstay across media and genres. Serial narratives supposedly facilitate spreading franchises out across multiple platforms. The media franchise demands long-format storytelling that can be spun off in multiple iterations. The rise of sequels is a much larger issue than a bunch of directors trying to make lots of money or audiences having unadventurous tastes–sequel/serial franchises are a central business model in the media industry today, supported and encouraged by the structure of conglomeration and horizontal integration.

The real point of the LAT article is that Hollywood is all commerce and no art, and sequels are a symptom. But this is such old news. And to connect it to a Squeeze summer tour is really stretching.

Jason Mittell: I think Michael’s cross-media point is crucial – continuity of a narrative world is a core part of nearly every storytelling form, but the language of “sequel” is applied predominantly to film. “Series” seems a more respectable term, as it suggests an organic continuity rather than a reactive stance of “Hey, let’s do that again!”

Are some serial/ sequel forms better suited to different media?

Jason Mittell: I think the LAT article is ultimately trying to valorize cinema’s potential to introduce something new, in reaction to the presumed rise of legitimate and praised series narratives on television (The Sopranos, Six Feet Under, Lost, etc.). And perhaps he has a point. Maybe film should stick to presenting compelling stand-alone short stories, since television has emerged as the leader in narrating persistent worlds? Or maybe I’m just saying that to pick a fight…

Jim Udden: I disagree that films should stick with one-off feature-length productions and leave ongoing series work to TV. Television has long had its Made for TV Movies, so why shouldn’t cinema think more in terms of series than it does? After all, if these are truly hard times for the film industry, as we’re always told, doesn’t it make more economic sense to adapt, just as TV has done in the last couple of decades?

True, there are things that cannot be matched on either side. I cannot imagine any film ever matching the daunting complexity of Deadwood or The Wire. Then again, some things work best as a stand-alone concern. Try to imagine a sequel to Pan’s Labyrinth or Children of Men, or try to imagine either film being made only for TV, for that matter. Moreover, some sequels should never be made. (Remember 2010?) On the other hand, some films would have been better off had they been pitched as an HBO series. (Syriana comes to mind.)

Yet film has proven its ability to take on a series format even when it is not called that. In a sense the oeuvres of most of the great art cinema auteurs are series of sorts. Aren’t Tati’s films a series with the ongoing presence of Hulot (or Hulots, if we include the false ones in Play Time)? And does anybody castigate Wong Kar-wai for following up Chungking Express with Fallen Angels, or In the Mood for Love with 2046, which are not series, but mere (gasp!) sequels? Clearly these examples were based not just on aesthetic visions, but on banking on previous success. Why do we give them a pass, but not more mainstream fare?

I think the more closely we look, the more we might find there are series and sequels even if they are not tagged by those names. It does happen in documentary, and not just in the 7 Up series. For example, American Dream does seem to me to a continuation of Harlan County USA, if not an outright sequel. Bowling for Columbine and Fahrenheit 9/11 combined make for a more complex argument about the relation of the defense industry to class issues than each one does on its own.

In other words, none of these formats has any value on its own. Everything depends on the type of stories to be told and the talent and economic wherewithal to find the best format for that story (or argument). The most appropriate format could be just a two-hour film, or it could be a television series going on for years. Or it could be something in between, such as the first two Infernal Affairs films, which got clumsily condensed into one film in The Departed. Both television and film can equally participate in such in-between formats.

DB: I don’t agree with all of these arguments and opinions, and I don’t expect you to either. The point is that compared to journalists’ rote dismissal of sequels, these writers offer more stimulating and more probing arguments. These guys are researchers and teachers, and they offer detailed evidence for their claim. They also write clearly, a point to remember when people say that film academics always talk in jargon and pontificate about gaseous theories.

To end on an upbeat note, I note that some journalists avoid the conventional wisdom. Consider Manohla Dargis’ recent and welcome defense of the blockbuster. Her case doesn’t seem to me spanking new: the artistic possibilities of the format have been defended for several years by film historians, as well in Tom Shone’s lively 2004 book Blockbuster. (1) Still, in the pages of the good, gray Times, Dargis’s piece remains something of a breakthrough. Maybe some day the paper will host a defense of sequels as well. If so, consider this communal blog a prequel.

(1) A sample, with Shone responding to the charge that the ’70s blockbuster drove out ambitious American filmmaking: “Any revolution that left it difficult for Robert Redford to make a movie as self-importantly glum as Ordinary People can be no bad thing” (Blockbuster, 312).

PS 30 June: Jason Mittell continues the conversation by contesting another journo’s claim that the public is tiring of sequels this summer.

Trims and outtakes

Some jottings from DB:

Continuity Boy meets Badgers

Tim Smith, who studies how we perceive film, recently visited our department at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. His talk was splendid.

Tim Smith, who studies how we perceive film, recently visited our department at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. His talk was splendid.

Tim studies the ways we scan shots and shift our attention across cuts. His talk was illustrated with film sequences showing little yellow dots swarming around the frame; these indicate the points in the image where his subjects’ glances landed. Tim shows pretty conclusively that there’s a consensus about where viewers look during a shot (faces, movement, the center of the frame) and that classical continuity cuts can push our attention to and fro with remarkable facility. One of the most surprising findings was that viewers are often starting to shift their attention to a new frame area just before the cut comes. Why? Tim has some intriguing suggestions.

Tim also showed some remarkable effects of what I’ve called “intensified continuity,” the fast-cut close-ups that characterize so much current cinema. Because these passages leave no time for visual exploration, viewers seem to revert to a cursory test for the shot’s basic point, usually at the center of the frame. Tim’s examples from Requiem for a Dream were fascinating, showing how real viewers are playing catchup in very fast-cut sequences.

This is rich and promising research, showing once more that Leonardo da Vinci, Eisenstein, and a few others were right to think that many creative choices in the arts can be studied with the tools of science. It also shows that filmmakers, like other artists, are seat-of-the-pants psychologists, achieving complex effects through decisions that “feel right” and that they have no need to explain theoretically. That’s our job.

For Tim’s narrative of his visit, and a lot more about his research program, go here. For something not quite completely different, about eye-tracking, print ads, and crotches, go here.

Six more from RKO

The enterprising folks at Turner Classic Movies have discovered six RKO films that have been missing for many years. It’s a harvest of 1930s titles, promising some intriguing situations (e. g., Ginger Rogers as a telemarketer) and carrying the names of directors like William Wellman, John Cromwell, and Garson Kanin.

A Man to Remember (1938; at the top of this page), Kanin’s first film, is the only one of the batch I’ve seen so far. One of the New York Times‘ ten best films of 1938, it went virtually unseen until a print surfaced at the Netherlands Filmmuseum in 2000. A Man to Remember is a portrait of a small-town doctor who tends to the poor and lets others, chiefly a cadre of corrupt businessmen, take credit for his good works.

It could all be mawkish, but Edward Ellis plays the doctor as a testy guy who levels with his patients and wins the town’s respect through quiet cussedness. The performance echoes Ellis’ crabby but likable inventor in The Thin Man (1934). Dalton Trumbo’s script has an intriguing flashback structure, less bold than in The Power and the Glory (1933) but still ambitious for a B project.

The six RKO discoveries are screening on April 4th as an ensemble, then they’re scattered through the rest of the month. All should be worth checking out. Once more TCM proves itself the film-lover’s channel of first choice.

Bambi or kitty?

Two recent books support the claim that New Hollywood, or New New Hollywood, is at bottom in debt to old Hollywood. (The full case is presented in The Way Hollywood Tells It and Kristin’s Storytelling in the New Hollywood.)

David Mamet’s Bambi vs. Godzilla: On the Nature, Purpose, and Practice of the Movie Business (Pantheon) is as pungent and eccentric as you’d expect, but also deeply traditional in its storytelling advice. A movie’s characters must have goals, and over the course of three acts they achieve them, or definitively don’t. The Lady Eve is Mamet’s model of this construction. Furthermore, three questions structure every scene: Who wants what from whom? What happens if they don’t get it? Why now? In wide-ranging essays, Mamet pays tribute to the craftsmanship of below-the-line talent and celebrates movies as various as The Diary of Anne Frank and I’ll Sleep When I’m Dead (whose protagonist is remarkable for “his personification of enigma”).

David Mamet’s Bambi vs. Godzilla: On the Nature, Purpose, and Practice of the Movie Business (Pantheon) is as pungent and eccentric as you’d expect, but also deeply traditional in its storytelling advice. A movie’s characters must have goals, and over the course of three acts they achieve them, or definitively don’t. The Lady Eve is Mamet’s model of this construction. Furthermore, three questions structure every scene: Who wants what from whom? What happens if they don’t get it? Why now? In wide-ranging essays, Mamet pays tribute to the craftsmanship of below-the-line talent and celebrates movies as various as The Diary of Anne Frank and I’ll Sleep When I’m Dead (whose protagonist is remarkable for “his personification of enigma”).

Mamet adds a fair amount on editing, supplementing the remarks in his Pudovkin-flavored On Directing Film. For instance: “At the end of the take, in a close-up or one-shot, have the speaker look left, right, up, and down. Why? Because you might just find you can get out of the scene if you can have the speaker throw the focus. To what? To an actor or insert to be shot later, or to be found in (stolen from) another scene. It’s free. Shoot it, ’cause you just might need it.”

Mamet bemoans the script reader, whose motto must be Conform or Die. By contrast, Blake Snyder makes conformity seem fun and–well, if not easy, at least attainable. His Save the Cat! The Last Book on Screenwriting You’ll Ever Need (Michael Wiese Productions) bulges with formulas, recipes, and gimmicks.

Like Kristin and me, Snyder treats the Second Act as really two sections, broken by a midpoint. But for him three acts are just the beginning. He demands that there be an Opening Image (on script p. 1), Theme Stated (p. 5), Catalyst (p. 12) and on and on until we get the Finale (pp. 85-110) and the Final Image (p. 110). This is the most strictly laid-out cadence I’ve seen; it would be fun to see if actual scripts adhere to it. In addition, you get catchy tips like Save the Cat! (show the protagonist doing something likable early on) and the Pope in the Pool (burying exposition). Snyder includes a list of the most common screenplay errors. An enjoyable read with some hints about construction I hadn’t encountered before.

Like Kristin and me, Snyder treats the Second Act as really two sections, broken by a midpoint. But for him three acts are just the beginning. He demands that there be an Opening Image (on script p. 1), Theme Stated (p. 5), Catalyst (p. 12) and on and on until we get the Finale (pp. 85-110) and the Final Image (p. 110). This is the most strictly laid-out cadence I’ve seen; it would be fun to see if actual scripts adhere to it. In addition, you get catchy tips like Save the Cat! (show the protagonist doing something likable early on) and the Pope in the Pool (burying exposition). Snyder includes a list of the most common screenplay errors. An enjoyable read with some hints about construction I hadn’t encountered before.

Speaking of screenplays….

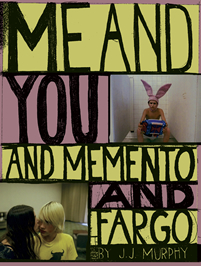

J. J. Murphy is an old friend (we went to grad school with him in 1971) and colleague (he teaches in our department). Renowned as an experimental filmmaker, he has turned his attention to American indie cinema. His new book Me and You and Memento and Fargo: How Independent Screenplays Work offers an in-depth analysis of several recent films. J. J. shows how they obey mainstream conventions of construction while still innovating in other ways. I especially like his discussions of Hartley’s Trust, Korine’s Gummo, and Lynch’s Mulholland Dr. I think it’s a book that everyone interested in current American cinema would find stimulating.

You can find out more about it, and read an excerpt, here. Congratulations, J. J.!

Originality and origin stories

Kristin here–

In the November 6 issue of Newsweek (also online), Devin Gordon comments on the recent trend in franchise series to throw in a prequel covering an earlier period in the main character’s life. “So-called origin stories—how fill-in-the-blank became fill-in-the-blank.”

At first David and I wondered whether Gordon, like so many film journalists, would go for the easy answer. There are at least two easy answers in the context of popular films, and especially blockbuster franchise films. One, their stories reflect something about the current psyche of the nation. Alternatively, they are symptoms of Hollywood running out of creativity and backbone and going for the tried and true.

The public psyche theory may sound profound at first, but it’s basically a quick way to write a story without knowing much of anything about film history or how the film industry works. There may be all sorts of reasons why a given kind of movie is made at a certain time. We all know about genre cycles. But society is vast and multi-faceted, and it isn’t hard to make any given film seem to “reflect” some aspect of it. Might the vogue for origins stories mirror a widespread desire to return to a more innocent era before 9/11? Bingo, you’re got your hook and can make your deadline. (Don’t get me started on the fact that most big films these days are negotiated, greenlit, planned, and in production for years before they appear, thus presumably reflecting not our own Zeitgeist but one that has come and gone.)

As to Hollywood running out of creativity, there are plenty of people in Tinseltown with great scripts and the desire to make them. We’re living in an age, though, when the big studios are owned by conglomerates. More than ever, the studio decision makers and the investors who buy their stocks keep an eye on the bottom line. Variety’s October 23 front-page story, “Less Dream, More Factory,” is on the layoffs and other cost-cutting measures that the big studios face. (By the way, we aren’t putting links to stories in Variety.com, since it’s a subscription-only site.) So the tactics of producers now must be to focus on exploiting the most popular characters and story premises for their tentpole projects.

Gordon recognizes this and puts his finger on a major reason for the vogue for “origin stories.” The studios have to prolong their most lucrative franchises, which are essentially their owners’ big brands. Yet those franchises can grow formulaic. One way to renew their energy can be to leap back in time.

Gordon opines, too, that “Ironically, playing it safe financially also provides studios with the cover to take creative chances.” He points to the fact that Peter Webber, who is directing Young Hannibal, has only the indie hit Girl with a Pearl Earring to his credit. Similarly, art-house darling Christopher Nolan gave one big franchise a new respectability and audience with Batman Begins and will try to continue to do so with The Dark Knight.

Linking origin stories to the hiring of such filmmakers is perhaps a bit of a stretch. The new Bond film, Casino Royale, the earliest in the order of Ian Fleming’s original novels, shows a younger agent. Much of the flashier high-tech props of recent entries in the series are apparently gone, with a grittier feel to the film. Yet it was directed by Martin Campbell, who also had made an earlier entry, GoldenEye, as well as both the Zorro films.

It’s true that recently Hollywood studios have shown a strange propensity to hire independent or foreign directors to helm entries in franchises. In the wake of his hit Once Were Warriors, New Zealand’s Lee Tamahori was imported and made Die Another Day and xXx: State of the Union. Warner Bros. brought in Mexican director Alfonso Cuarón (Y tu mamá también) to make the third Harry Potter film, presumably because many critics had dubbed the first two, by Chris Colombus, too bland. Perhaps the studios simply see franchises as needing shaking up at intervals. Yet this is part of a larger trend of indie directors suddenly boosted to blockbuster assignments, as when Doug Liman went from Go to The Bourne Identity and Mr. and Mrs. Smith.

An “origin story” in the sense that Gordon is using the phrase is a type of prequel that jumps back far enough to show the protagonist distinctly younger and different from the way he is in the original film or series. It then explains how he changed into that protagonist.

Hong Kong filmmakers are adept at prequels of this sort. God of Gamblers: The Early Years, shows us the source of the protagonist’s lucky ring and his taste for gold-wrapped chocolate, both of which are major motifs in the original God of Gamblers. The case of A Better Tomorrow is more complicated. John Woo and Tsui Hark had intended it to be a stand-alone film, and they made the mistake of killing off the most charismatic character. The film was such a hit, largely on the basis of Chow Yun Fat’s performance as Mark, that A Better Tomorrow II gave Mark a twin brother, Ken, and put Chow back in action. That film’s success led to a prequel to the first film. A Better Tomorrow III traces how the Mark character acquired his fighting skills and his signature costume and habits.

Origin stories are not entirely new to Hollywood, either. As far back as 1974, The Godfather Part II wove in flashbacks to a time well before the first film’s action, tracing Don Corleone’s rise. In 1979, there was Butch and Sundance: The Early Days.

Origin stories can be thought of as expansions of a basic convention of mainstream storytelling: the flashback to crucial formative moments in a character’s life. In that sense, perhaps the quintessential origin story is Citizen Kane. Today, when everything is potentially franchisable, such an early-days sequence can create a series. The prologue of Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade shows young Jones launching upon an adventure that prefigures the man he will become. (In what surely is an inside joke, River Phoenix even acquires Harrison Ford’s chin scar.) That sequence in turn spawned The Chronicles of Young Indiana Jones TV series (“Before the world discovered Indiana, Indiana discovered the world”) and four cable movies.

As a term, “origin stories” was coined by students of mythology, who use it to refer to various ethnic groups’ accounts of the origin of the world. In that case, it didn’t have anything to do with what we now call prequels.

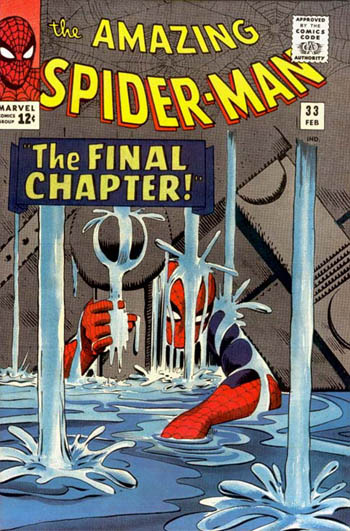

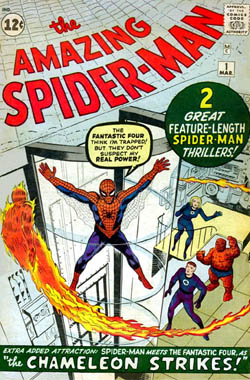

Then the term got taken up in discussions of comic books to identify the sort of thing that Gordon is talking about. Before television, comic books were the ultimate franchise form of the twentieth century. In comic franchises, particularly those centering on superheroes, a book or short series of books might be devoted to an origin story. (Dave Carter’s blog has a lengthy entry on comic-book origin stories, giving examples.) It’s not surprising that one of the main origin films, Batman Begins, came from the comics.

Gordon does not mention another reason why studios might want to continue a franchise by jumping back to the hero’s origins: actors can age too much to continue a role. It’s been over 14 years since The Silence of the Lambs, and Anthony Hopkins could probably not be convincing in another turn as Lecter. Possibly we’ll get a chance to see whether a 60-something (or 70-something at the rate things are going) Harrison Ford can bring audiences in for the on-again-off-again Indiana Jones continuation. Or actors may exit the franchise, as Jody Foster did before Hannibal. Or grow up too quickly, as the Harry Potter kids are doing before our eyes. Or die, as Richard Harris did in the same series, forcing Warners to substitute Michael Gambon as Dumbledore.

But origin stories don’t have these problems. Just get new actors. One thing tentpole franchise films have taught us is that, as strongly identified with a character as a star may become, if the character and premises are even stronger, a new actor will be accepted. It’s happened with Batman, Superman, Bond, and almost did—and could yet–with Spider-Man.

Such stories, however, have their dangers as well. If the audience is devoted to the character as he (and it’s mostly he so far) is, will they care about seeing him as a very different person? If Hannibal Lecter is the middle-aged psychopath we love to hate, do we want to learn that he was once a vulnerable, suffering youth?