Archive for the 'Silent film' Category

When we dead awaken: William Desmond Taylor made movies too

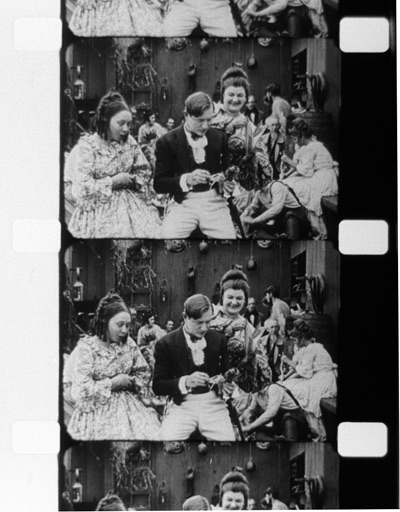

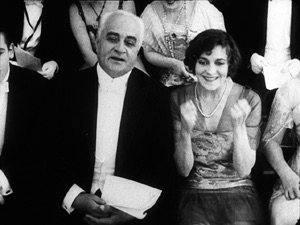

Ben Blair (1916).

DB here:

It wasn’t until they turned the body over that they realized he had been shot. By then, the crime scene had become chaos. Studio employees swarmed over the bungalow and swiped incriminating letters, while neighbors and reporters drifted in freely. The police left their own fingerprints around the place. No wonder the case remains unsolved.

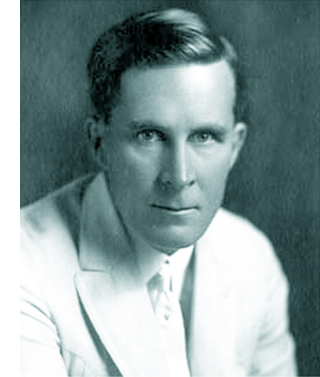

William Desmond Taylor’s place in film history is secure, but not because of his movies. His 1922 murder galvanized the nation. Suspects included stars Mabel Normand and Mary Miles Minter, Minter’s mother, an embezzler, an estranged brother, bootleggers, drug pushers, blackmailers, and assorted low-lifes. The case reeked deliciously of scandal.

William Desmond Taylor’s place in film history is secure, but not because of his movies. His 1922 murder galvanized the nation. Suspects included stars Mabel Normand and Mary Miles Minter, Minter’s mother, an embezzler, an estranged brother, bootleggers, drug pushers, blackmailers, and assorted low-lifes. The case reeked deliciously of scandal.

Minter was infatuated with him, her mother owned a .38, and Taylor’s secretary had absconded with a car and forged checks. Speculation spread in many directions. Was Taylor gay or bisexual? Was he a drug addict, or a supplier, or someone trying to rescue a friend from addiction? Did Mary and Mabel quarrel over his affections? Who was his late-night male visitor? Did the bungalow actually contain tagged items of ladies’ lingerie, and pornographic photos of Taylor cavorting with starlets?

For nearly a hundred years fans and tabloid TV have returned obsessively to the murder. Even King Vidor began sleuthing late in life with the aid of Colleen Moore.

Taylor cut quite the figure. Tall, handsome, and solemn of mien, he left Ireland and led a barnstorming life in America. He abandoned a wife and daughter in New York to take up touring stage work. He wound up in Hollywood. After some acting successes, he directed shorts before graduating to the popular serial The Diamond from the Sky (1915). His feature films were widely respected, and he became a key figure in forming the Directors Guild (then the Motion Picture Directors’ Association).

Okay, it makes a swell mystery. But what about Taylor’s movies?

The other sort of teenpix

Back in 1976, Richard Koszarski had the very good idea of mounting a program called The Rivals of D. W. Griffith for the Walker Art Center. Auteurism was at its height, so it’s no surprise that the program’s subtitle was Alternative Auteurs: 1913-1918.

Remember, this was before all those festivals that today specialize in exhuming silent classics. Beta and VHS had just been introduced and were not yet popular. There was no Criterion, Flicker Alley, or TCM, or any other platform that would give these old movies a mass-market afterlife.

Since then, things have improved a lot. We can now see on video nearly everything in Richard’s show: Wild and Woolly, Stella Maris, Juve vs. Fantômas, The Italian, Hell’s Hinges, The Mysterious X, Straight Shooting, The Gun Woman, Behind the Screen, The Rink, The Immigrant, The Outlaw and His Wife, The Cheat, and The Blue Bird. Some of the copies are shabby, but they’re out there. Anyhow, collectors’ 16mm dupes that circulated back in the day were hardly impeccable.

The program helped balance out historical accounts. Richard’s opening essay in the program’s catalogue flung down the challenge. Most historians had ignored the period, but:

Even the most casual investigation must reveal the years 1913-18 as the most hectic, tumultuous and progressive in the entire history of the cinema.

Richard’s aim wasn’t to attack Griffith. This was a time when cinephiles were discovering the superb Biograph shorts, and appreciation of his artistry was expanding. Instead, Richard usefully reminded us of all the other things going on as features emerged.

Looking at the films in this program will help anyone appreciate even more fully Griffith’s strengths, and pinpoint more certainly his weaknesses. Often his individual achievements will be matched, sometimes surpassed.

Richard’s introduction ably sums up the changes in the industry that made the period so fertile. And the contributors’ notes that follow, while brief, point up valuable things about the program. The Rivals of D. W. Griffith is still very much worth having.

Richard’s introduction ably sums up the changes in the industry that made the period so fertile. And the contributors’ notes that follow, while brief, point up valuable things about the program. The Rivals of D. W. Griffith is still very much worth having.

My recent investigation of nearly a hundred U.S. features from the period wasn’t exactly casual, but it seems merely a depth sounding of a vast body of extraordinary work. I’ve offered you glimpses of it in earlier entries (here and here and here), but there’s a lot more I’d like to share.

Which brings me back to William Desmond Taylor. He doesn’t figure in Richard’s Rivals show, probably because few of his films were available. Most of his work is lost. He signed forty features between 1915 and 1922, of which seventeen apparently survive, many incomplete. Most of those I’ve seen are solid but not dazzling. The amiable Tom Sawyer (1917) is a good example of how polished Hollywood cinema already was in 1917, and the leisurely Mary Pickford item Johanna Enlists (1918) is ingratiating as well. At the film’s climax Taylor tries for triangular staging of the type that would come in the 1920s, but he botches it with mismatched eyelines and screen directions. By the time of The Soul of Youth (1920), a touching movie about juvenile delinquency, the cutting is very meticulous, as in Huckleberry Finn (1920). Both films use startlingly tight close-ups, some of them shot with a wide-angle lens.

Taylor also claimed innovations in visual narration. His now-lost Sacred and Profane Love (1921) was promoted as including scenes in which an expository title rises up over character action, makes its comment, and melts away while the scene continues. Perhaps the opening of The Soul of Youth was a step in this direction. In chiseled silhouettes we see an unwed mother selling her baby to a gangster’s girlfriend, introduced through “art titles” dissolving away to reveal the action.

The Soul of Youth also includes some embedded scene movement in the corners of titles. Such experimentation with intertitles was a trend of the period.

So we have a director of some ambition. That inference is backed up by some flashy moments in earlier 1910s work. In 1916 Taylor released a remarkable nine features, and during my DC stay I saw what remains of four of them. Although they’re in parlous shape, they show a lively pictorial and dramatic intelligence. Are they auteur films in the strong sense? At least we can say that Taylor, like many other directors, was channeling just that exuberant creative energy that Richard evokes. Certain moments in two of these movies have genuine flair, and one film is an all-out stunner. I had never heard of any of them.

1916 and all that

My first 1916 title is Pasquale. It stars George Bevan, famous for his stage roles as good-natured Italians. It’s a story of friendship betrayed. Two immigrants who return home to fight for Italy are shown to be more honorable than the American men who cheat them and beat their women.

“A mighty good feature,” said Variety’s reviewer, but you can’t prove it by me. The Library of Congress print lacked the first and last reels, and what was in between consisted of scenes and parts of scenes jumbled up. While it’s certainly competent, I didn’t see much subtlety in its staging or cutting. The use of crosscutting to tie together its story lines was standard for the period.

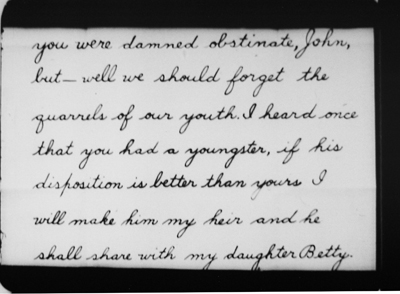

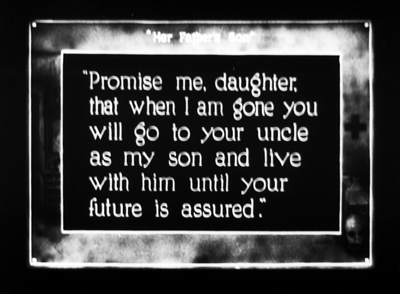

The print of the Civil War story Her Father’s Son was a little scrambled too, and it lacked the final reel, but it was more coherent. A girl from the North must pretend to be a boy—first, to satisfy an old Southerner’s urge for an heir, then after the war starts she is pressed into service as a courier, and eventually a sterling supporter of the confederacy. The most noteworthy bit of technique, I thought, involved the varied camera setups in one scene. Frances (Vivian Martin) is asked by her dying father to go live with his brother as a boy. The changes in shot scale and angle emphasize her moment of decision, as well as her reaction to her father’s death.

This passage shows more flexibility of camera setup than Griffith displays in the sequences in the Union hospital in The Birth of a Nation (1915), or in Intolerance, from the same year as Taylor’s film. Taylor here joins a general push toward finer-grained analytical editing in dialogue scenes. Other examples are Reginald Barker’s The Bargain (1914) and DeMille’s The Cheat (1915).

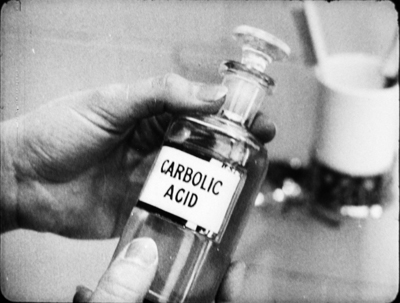

The House of Lies is more flamboyant and peculiar. Edna is an ethereal girl who likes waterfalls, poetry, children, and rabbits. Her stepsister Dorothy is vain and soulless. Mrs. Coleman is determined to marry both off to wealthy men. Refusing to trade her beauty for social position, Edna splashes her face with acid. She becomes the secretary of the sensitive author Marcus Auriel. But the stepmother is plotting to snare him for Dorothy, while also joining forces with a thief who wants to steal a financial document from Auriel’s safe.

Variety considered The House of Lies a good example of “what a feature picture should not be.” The reviewer considered it old-fashioned melodrama. Fair enough, but it doesn’t creak much and has considerable visual fluency. Sometimes there are echoes of the tableau style, as when Edna steps aside to reveal her sister and stepmother dressing in the background.

But the same tableau setup gets overridden by the sort of axial cut so common at the period. Earlier in the scene when the stepsisters get dressed for the big party at which they’ll be displayed, instead of letting Dorothy step aside to reveal the other women, Taylor “cuts through” Edna’s blocking figure to the women behind her.

The transition would be jumpy were it not for a (mispunctuated) title: “I don’t understand all this display mother; when we should still be in mourning for father.”

A variant of the axial cut employs a 180-degree reversal. We’ve already seen Edna’s reluctance to enter “the auction” at which rich men will look her and Dorothy over. She pauses at the doorway, which in wealthy houses of this period always seem to be covered with a heavy curtain.

Later, after her mother has taken Dorothy around to meet her guests, we see the poet Auriel remark to a friend that it’s like a modern slave market. Cut to the opposite side of the men to reveal Edna’s reaction to his line.

It’s this that drives her upstairs to destroy her beauty.

The acid-splashing is of course the grisly high point of this drama. It’s handled with what at first seems a tactful obliqueness.

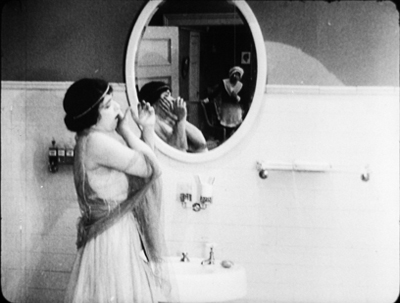

Mrs. Coleman has summoned a maid to bring Edna back to the gathering. As she enters, Edna stands at the mirror, pondering. Since Dorothy is the sister associated with mirrors, this seems out of character for Edna.

Seeing the maid, she picks up the bottle of acid. Before opening it, she experimentally rubs her face.

A closer view of her at the mirror shows her ostentatiously lifting the bottle, as if making sure the maid sees it. In retrospect, it may be that she’s staging the scene for an eyewitness.

Cut back to the original bathroom framing as Edna seizes her cheek and cries out. She runs into the next room, as seen in the reflection.

A nice match on action brings Edna into the boudoir, where she collapses.

Thereafter Edna sports a ravaged cheek or a discreet bandage. Eventually Auriel declares that he loves her despite her deformity. She then reveals that her scar is mere makeup. She never really applied the acid. She wanted out of the marriage auction and sought someone to love her for herself.

Taylor’s framing and cutting conspire with Edna to conceal her deception. Mirrors create spatial trickery in 1910s films from both America and Europe, often doing duty for reverse angles or POV cutting. The embedded image usually serves to expand what we know, as it does here.

But Taylor’s mirror reflection also makes the maid into a decoy, teasing us to watch her as well as Edna. Hiding what Edna was up to would have been more obvious if we didn’t have the maid to distract us. Of course Taylor could simply have cut away from Edna at the crucial moment, but that wouldn’t carry as much conviction as seeing an apparently full, if discreet, shot of the self-mutilation.

A noir western?

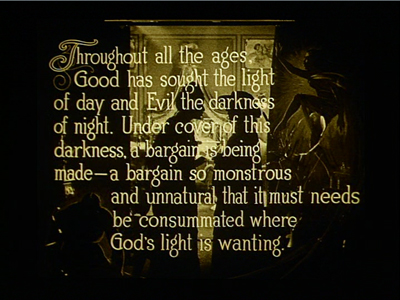

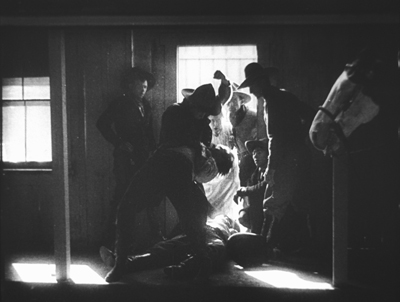

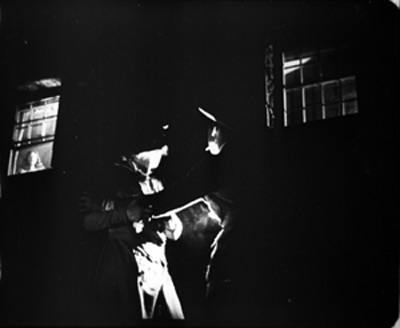

Noirish westerns like Duel in the Sun (1947), Pursued (1947), and The Furies (1950) revolve around dysfunctional families, tyrannical patriarchs, childhood anguish, and sadistic corruption. Somewhat in this vein is one of the story lines that inform Taylor’s Ben Blair (1916). The noirish action is embedded within a larger plot involving the clash of New York decadence and prairie rectitude. As a bonus, certain scenes evoke that proto-noir style I considered in an earlier entry. One scene of violence is spectacularly beautiful—Ford meets Mann, shall we say, before both showed up.

The film roughly follows the plot of the 1905 novel. When Tom Blair’s common-law wife dies of illness and neglect, he sets fire to his ranch house in an effort to destroy her corpse and kill her son Ben. The boy escapes and is adopted by the good-hearted rancher Rankin. Ben grows up alongside Florence, daughter of another rancher. When Flo’s father dies, his widow takes Flo to New York in search of a husband for her. In the meantime, Tom Blair has returned and is raiding local ranches for horses. He shoots Rankin, and Ben sets out to avenge both his mother and his benefactor.

The second half of the novel, and the film, brings Ben to New York. He finds Flo captivated by the urbane but unstable Clarence Sidwell. After Ben sees the depravity of city life, he tries to lure Flo away.

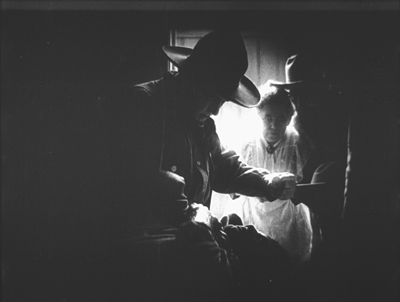

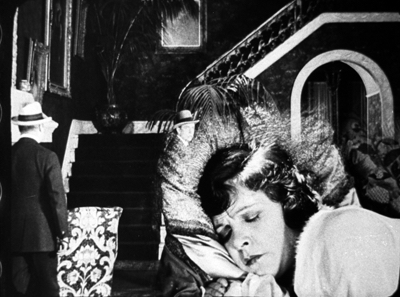

Second things first. Critics found the New York section of the book less evocative than the Western half, but such can’t be said for the film. An eyebrow-raising introduction to the rake Sidwell leaves little to the imagination.

Flo had told Ben she wanted to leave the West for “the things of civilization.” Now we get a title: “The things of civilization. Exhibit 1: Clarence Sidwell.” Fade in on a louche creature pouring himself a drink.

Shock cut back: In an extreme long-shot, a young woman bursts out from the distant bedroom, dodges Sidwell, zigzags desperately through the vast parlor, and hurls herself out of the foreground.

As the deep space of 1910s cinema becomes an obstacle course, we’re obliged to understand that the poor woman has been raped. The power of the scene comes from her frantic rush toward us in contrast with Sidwell’s bored calm.

When she collapses in the next room, he moves as if to follow her, then shrugs and returns to his post-coital drink. In the novel, Sidwell is a neurotic workaholic, nothing like this chilling libertine.

A parallel scene occurs later, when Ben has come to Manhattan to visit Flo. On the street at night, he chivalrously agrees to see a woman to her apartment, only to find that he’s been tricked into visiting a brothel.

As in the novel, he shoots his way out (these sissies can’t handle him), but not before he glimpses Sidwell there with a floozy. This, along with Sidwell’s rape of the woman we’ve already seen, reminds you of what all those censors were complaining about in the era of scandals around Fatty Arbuckle, Wallace Reid, and other Taylor contemporaries.

Ben learns that Flo has agreed to marry Sidwell, and Ben’s memory compares the brothel revelation with Flo’s farewell to him back on the ranch.

He must save her from this man.

Ben is too honorable to snitch on Sidwell. He simply walks in the family mansion and tells Flo that she is leaving with him in half an hour, or he will kill Sidwell. He counts on her underlying love for him and their childhood home. After her indignation dies down, she agrees happily to go “back to God’s country.”

The tension of the film’s first half centers on Tom Blair’s murder of the genial old Raskin and Ben’s pursuit of Blair. Tom, it turns out, isn’t Ben’s biological father; Raskin is. Tom has killed Ben’s mother through abuse and his natural father through homicide, so the son’s quest gains mythical overtones.

There are some majestic vistas, along with flashy exchanges of gunfire among rocks. The clincher comes when at the height of their fistfight, Ben is ready to strangle Tom and bends over him. The false father gasps for mercy.

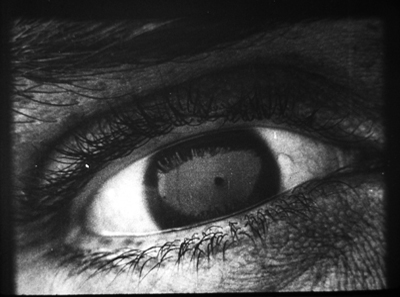

A brutal cut takes us to Ben’s eye, which fills with the image of Florence.

We realize that he couldn’t face Flo if he murdered a man in cold blood. So he lets Tom live, drags him back to town, and even saves him from a lynch mob. But this moment—in 1916, remember—shows how eager filmmakers of this period were to maximize the emotional power of a scene. Often we’ll find that an expository title and a bit of facial emoting has been replaced by tactics of cutting, framing, and here, precise special effects.

Devil’s doorway

Skilful backlighting is more precious than a gallon of peroxide!

William Desmond Taylor

This isn’t the film’s only prefiguration of the noir hero driven to the brink. Ben has nearly lost control earlier in the film, and this scene involves the noir look as well. It grows out of Tom Blair’s cold-blooded murder of Raskin.

In the novel, Ben witnesses it from the barn, but he’s too late to catch Tom before he rides off. In the film, Ben is in town, seeing off Flo and her mother at the train. Now the scene is played out for us, with the cook as an appalled side participant.

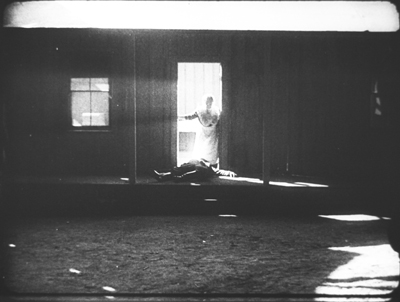

Hearing noise in the corral, Raskin steps out on the porch. The edge lighting outlines him vividly enough to be visible, and cut down.

A 180-degree reverse shot puts us inside as the cook rushes to the door and peers out.

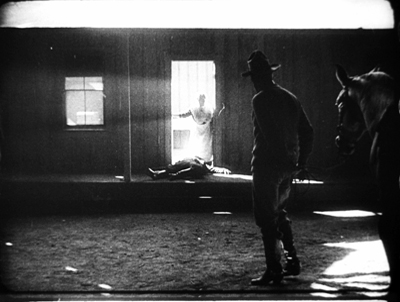

Cut 180 degrees again to a variant of the first shot, framing the bunkhouse in long shot. After a beat, Tom Blair and his horse appear in the foreground. The lighting here is of remarkable delicacy: the silhouettes are barely picked out.

We return to the shot inside the bunkhouse. Another beat: The face of the man passing emerges as she turns away in horror.

Tom mounts his horse and rides off. Soon, in another shot from outside, the ranch workers gather at the doorway, as Ben arrives with his horse. One standard option would be to have the dead man carried in, to have the men assemble around the body, and in clear light and shot/ reverse-shot, to show Ben issuing his orders. Instead, Rankin’s body lies blocking the threshold and all the action is played in the bright rectangle and made emphatic by axial cuts.

The first cut comes as Ben reacts to what has happened. He’s in darkness, with the cook and cowpokes watching.

Ben tells them to take care of Rankin: “Put up your guns, boys–This is my affair.”

When one of the men accuses him of trying to cover up for his father, Ben explodes and starts beating him. A cut in to a closer view shows him strangling the offender. As in later cinema, the abrupt cut accentuates the violence of Ben’s attack.

An axial cut back shows the victim protesting: “Let up–I didn’t mean it!” Ben shoves him aside and bends over the dead man sorrowfully.

The ranch hands carry Rankin’s body in. Ben is left in the doorway brooding on what he must do to avenge the death of his surrogate father.

Call it Fordian if you want. I wouldn’t object.

Given the fame of Dustin Farnum as a star at that moment, it seems fairly daring to subordinate a dramatic high point to this incisive visual design, with all the action squeezed into the doorway. Stance and gesture have replaced close-ups and facial reactions. The scene varies so much from the book that we might want to credit the scenarist, Julia Crawford Ivers. Ivers, who who had directed films herself, collaborated closely with Taylor on his projects. The cinematographer, perhaps Homer Scott (another Taylor mainstay and a significant DP before 1923), may also have had a big say in this virtuoso scene. The film could claim its “Lasky lighting” as typical of the Paramount brand.

All of Taylor’s surviving films I’ve seen are of interest; he’s clearly one of the more talented directors to give up the tableau and work in the continuity style that would define Hollywood. In particular, Ben Blair would definitely be worth reconstructing and restoring. The LoC print, while jumbled in its last two reels, is fairly complete, and the shots could be rearranged coherently. At the risk of spoilers, I wanted to share with you my discovery of this exciting piece of work. Taylor deserves to be remembered for more than his fate that night in February 1922.

Thanks again to the John W. Kluge Center for providing me a long stay at the Library of Congress. The Moving Image Research Center was my host, and so I’m grateful to Mike Mashon, Greg Lukow, Karen Fishman, Dorinda Hartmann, Josie Walters-Johnston, Zoran Sinobad, and Rosemary Hanes. They’re doing a wonderful job. Special thanks to Richard Koszarski for background on his Rivals program, and to Alan Gevinson for discussions of 1910s cinema generally and Taylor in particular.

Relevant to this entry is Kristin’s article is “The International Exploration of Cinematic Expressivity,” in Film and the First World War, ed. Karel Dibbets and Bert Hogenkamp (Amsterdam University Press, 1995), 65-85. She discusses American lighting practices of the period in The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960 (Columbia University Press, 1985), 223-227. See also Lea Jacobs’ article “Belasco, DeMille and the Development of Lasky Lighting,” Film History 5, 4 (December 1993), 405-418.

Some Taylor films are available on DVD. The most authoritative is the beautiful restoration of The Soul of Youth that’s included in Treasures of American Film Archives vol. III: Social Issues in American Film 1900-1934. Tom Sawyer is available in a fairly good copy, as is Huckleberry Finn, which doesn’t survive complete; it has played on TCM in a tinted version. Copies of Johanna Enlists and Nurse Marjorie are problematic but watchable.

Ben Blair was mostly liked in the trade papers, though Variety claimed that the film was “hardly up to the Paramount standard.” But using the same phrase, Manhattan’s Broadway movie theatre declined to show it. You wonder if the Sidwell rape scene had something to do with the decision. After some wrangling, the management cut it to two reels and “used it as ‘filler.'” Tastes do change.

On Taylor’s career, see Richard Koszarski, “The William Desmond Taylor Mystery,” Griffithiana 38/39 (October 1990), 253-56. The most authoritative reference on Taylor’s life is Bruce Long’s collection of clippings and commentary William Desmond Taylor: A Dossier (Scarecrow, 1991), from which my backlighting quotation comes (p. 162). Alan Gevinson’s filmography in Long’s book is the most comprehensive I know. Long also ran the online publication Taylorology, which offered exhaustive coverage and analysis of the murder.

Speaking of the murder, there’s enough material in books and online to keep aficionados busy for years. Whodunit? Since this entry is spoiler-filled, I’ll summon a lineup. The principal books on the case finger four suspects: Mary Miles Minter’s mother (favored by King Vidor, as reported by Kirkpatrick); Mary herself (Higham); a hitman for a drug gang (Giroux); and one of a trio of blackmailers (Mann). Long’s Dossier lists many errata in the first two of these. Of these, Giroux’s is the most sober and avoids High Tabloidese, as well as the confident reporting of the thoughts and feelings of people long dead. My own hunch is that too much evidence has been destroyed to permit a plausible conclusion.

Still, the Taylorologists have supplied fascinating information on what Hollywood culture was like at the period. It still astonishes me that celebrities like Taylor, Minter, and Edna Purviance could live without bodyguards and security, while Mabel Normand could just stroll down the street to buy a bag of peanuts. And all chroniclers agree that the studios kept a lid on an investigation that law enforcement conveniently botched.

A quick and entertaining overview of the scandal is Rick Geavy’s graphic novel Famous Players: The Mysterious Death of William Desmond Taylor (NBM, 2009).

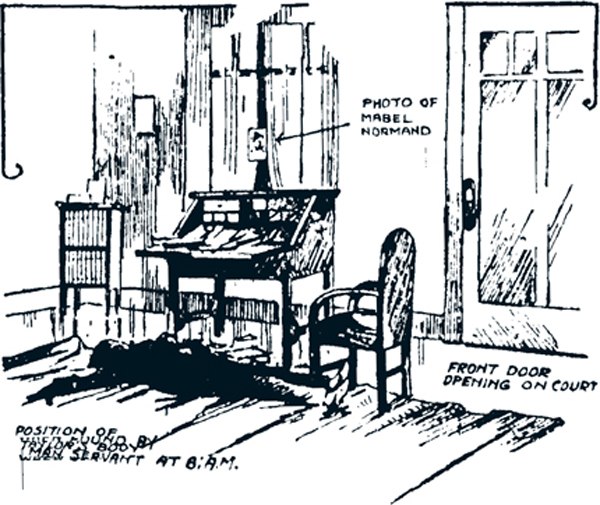

Okay, I can’t refrain from going a bit sleazy too. Below is a drawing of the crime scene from a newspaper of the period.

P.s. 4 January 2021: Add Erle Stanley Gardner to the list of distinguished investigators of the crime. His “1922: William Desmond Taylor,” summarizing press reports and offering some speculative inferences, appeared in Los Angeles Murders, ed. Craig Rice (Duell, Sloan and Pearce, 1947), 83-119.

Thanks to Taylorology and The Silent Era.

Film noir, a hundred years ago

A Romance of the Air (1918).

DB here:

One of the most persistent conventions in American cinema associates dark images with dangerous doings—crime, mystery, violence, espionage, sexual depredations, visits from beyond the grave. The strategy is most apparent in what critics eventually called film noir. Those 1940s “films of darkness” are sometimes said to derive from German Expressionist cinema, but the look was already a Hollywood tradition. Filmmakers had long treated scenes of mystery and suspense with hard, low-key lighting that yielded rich chiaroscuro.

When does it start? You can find very early examples, but it seems to have crystallized during the 1910s. Kristin has talked about this as a period when filmmakers were collectively struggling to tell somewhat lengthy stories in a clear fashion. Along with clarity, she argues, came efforts to add emotional impact to a scene. Those included dynamic staging, fast cutting, close-up framings, subtle but arresting performance styles, ambitious camera movements, and lighting that enhanced the mood of the action. She points to many European and American films of the years 1912-1916 that flaunt silhouettes and selective lighting.

I found a lot of prototypes of noirish images during my recent trawling through Library of Congress films from 1914-1918. In this era, it seems, filmmakers competed to create striking, even shocking, lighting effects. Later directors and cinematographers would adopt many of them as proven tools for boosting their scenes’ emotional power.

So today’s entry is mostly just some pictures that try to convince you, once more, that the 1910s laid down a great deal of what we take for granted in films ever since. You may want to turn up your display. We’re going dark.

No sunshine here

Start with the shot up top, from the independent production A Romance of the Air (1918). Produced by and starring Bert Hall, flyboy and author of the source book, it traces how German spies posing as French refugees win his confidence and try to steal secrets about troop movements. It was released in the month of the Armistice, and it got what appears to be a welcome reaction from audiences.

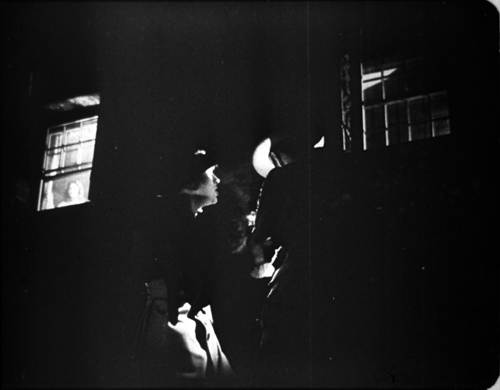

A Romance of the Air, nearly amateurish in its opening stretches, gets more competent as it goes along. But there’s only one real uptick from a pictorial viewpoint. Two spies have attempted to gas Edith, Bert’s sweetheart, but fortunately their incompetence leads them to the wrong room. They meet outside the house, and suddenly we get a shot that had me hollering.

As the man lights a cigarette, a low-slung angle shows the flare of the match illuminating his hatbrim and the countess beside him. In the upper left Edith peers down from a window. We might be in Hollywood, 1945, perhaps in the hands of production designer William Cameron Menzies or ace DP John Alton.

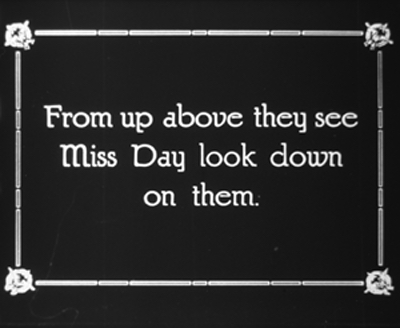

It’s interesting that a title pops in here, coaxing the audience to notice the face at the window.

The mistaken placement of “From up above” tells you something of the clumsiness of this whole production. Yet bad grammar is redeemed when we return to the framing as the spies twist around in surprise and the man clutches the countess.

Other filmmakers of the period would have trusted the audience to spot Edith, but nonetheless an undistinguished, forgotten film bequeathes us one bold moment.

We can see a more conventional look emerging when characters get sent to jail. By the end of the 1920s, filmmakers had found a way to crosslight cell bars to make them stand out crisply, as here in von Sternberg’s Thunderbolt (1929).

A jail scene in The Unknown (1915) isn’t so flashy, but the concept of edge-lighting the bars is there. If all you wanted was clarity, the naked cell door suffices, but the sidelight makes the barrier more vivid.

At this point, some directors were willing to leave large patches of the image in darkness, even at the risk of off-balance compositions. This is not only expressive; it saves money on set construction. So trust Maurice Tourneur to go further. In Alias Jimmy Valentine (1915), one of the most accomplished films of the era, we get cons as patient silhouettes.

No need to see their expressions; the outlines of their poses express their resignation.

Speaking of prisoners, consider the plight of Ivanoff, the revolutionary who has been sentenced to Siberia in Cecil B. DeMille’s The Man from Home (1914). He has escaped from the mines and taken refuge in a stable. Filing off his chains, he crouches as guards pass by outside. First, he’s in a glare, but when he hears them….

… he shifts into semi-shadow.

The guards’ approach is measured by a barely noticeable change: the gleaming surface on the far left is briefly darkened.

This is a bold instance of “Lasky lighting,” the brilliant effects which DeMille worked up with Wilfred Buckland, Belasco’s stage designer. Several films in my sample exemplify this style, which became part of Jesse Lasky’s Paramount brand. Examples are comparatively abundant because many Paramount films have survived from the silent era.

Camera obscura

In A Romance of the Air, the darkness is motivated as a night scene, and naturally prisons and hiding places are associated with danger. Another option is to stage scenes in darkened rooms, populated by sneaking and skulking characters. Again, the association with criminality is evident. In Alias Jimmy Valentine, hoods hide from cops and are visible thanks to diagonal edge lighting.

More dynamic are two suspense scenes in Madam Who (1918), the story of a plucky Southern belle who goes undercover for the Confederate cause. In the first, disguised as a man, she peers down from a hayloft to watch the meeting of the Sons of the North gang. We get an optical POV shot straight down, and then a close reaction shot, with a fish-hook of light snagging her face as she glances at us.

Reginald Barker, one of the most resourceful directors of the era, didn’t let up in a later scene of Madam Who. Jeanne and the secret agent Henry Morgan get the drop on the Sons’ leader Kennedy. The action plays out in layers of darkness, with her poking a pistol through the doorway right of center, and it’s capped by a stark close-up.

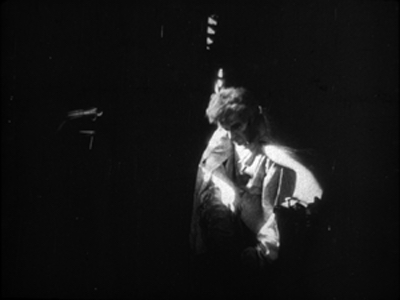

In the late 1910s, several directors use such darkened interiors for fight scenes. In De Luxe Annie (1918), the heroine’s husband takes a brutal beating from the criminal he’s trapped. The accomplice runs to administer a hypodermic.

Something similar happens in The Family Skeleton (1918), when dissolute Billy (Charles Ray) battles the bully who has tormented him throughout the movie.

Shadow-filled rooms help amp up suspense during fistfights. We can’t be sure who’s winning, and the enveloping darkness can also suggest more savage violence than could be shown in normal light.

Or you can stage a fight or a chase in a darkened area outdoors. The Sign of the Spade (1918) sets its climactic abduction and rescue under a seaside pier, and the silhouettes that result would not have shamed Panic in the Streets (1950).

As with the jail in Jimmy Valentine, we have to read the characters’ emotions–chiefly, the desperation of the fleeing woman–from their body language. And as often happens, the more we have to strain to see the action, the more gripping it becomes.

Billy and two Annies

De Luxe Annie (1918).

Of course what we call film noir includes more than visual style. Like many terms in the arts, film noir picks out a cluster concept. It links together distinctive subjects (urban life, abnormal mental states, misogyny), attitudes (alienation, nihilism, malaise, mistrust of authority and the upper class), themes (official corruption, revenge, male friendship and betrayal), plots (investigation, pursuit, deception), narrational devices (flashbacks, voice-over commentary, dreams and hallucinations), and visual techniques. Because noir is a cluster concept, eager acolytes can choose some noir-ish qualities of Film A and declare it a more or less plausible instance, while with Film B a quite different set of features might help it qualify too.

For example, in visual technique, only a few shots of Laura carry traces of the lighting style we think characteristic of noir. But the film does present a decadent, treacherous milieu harboring a mysterious, perhaps dangerous woman who may be feeding a man’s delusions and obsessions. Laura, I’d suggest, counts as a noir on thematic and narrative grounds more than on stylistic ones.

So do we find non-stylistic features of noir in the 1910s? Sometimes, yes. I’ll save my prime example, an intricate and beautiful thing, for an entry of its own. But here are two nifty cases where the visual pyrotechnics spring from noirish narrative and thematic pressures.

Billy Bates is warned that alcoholism runs in his family, but on getting his inheritance he holds a party and learns that he likes the stuff. Not needing to work, he keeps drinking. He falls in love with chorus girl Poppy Drayton, but when she’s insulted in a saloon he’s too crocked to defend her from the hulking Spider, who beats and shames him. Billy learns that Spider is planning to abduct Poppy and so lays a trap. He waits in Polly’s parlor, resolving to stay sober long enough to defend her. Unfortunately, there’s a decanter of scotch within easy reach….

The Family Skeleton (1918) was touted as a “semi-farcical production” but the semi- parts took alcohol addiction fairly seriously. The popular Ray often played the country-boy underdog, so audiences were probably unprepared to see him as a millionaire twitching from the D.T.’s. The scenes of his drunkenness are truly unnerving, even when the plot is lightened by the revelation that Spider is a detective hired by Poppy to force Billy to man up. Billy does, in the nocturnal fistfight illustrated above. There darkness makes Billy’s ultimate victory more plausible; we can’t really see his winning punches.

In the buildup to the fight, however, we get Billy’s growing anxiety over the scotch across the room. He stares at the decanter.

A cut shows us a condensed mental image: what would happen if he drank the contents. In this hypothetical future, the decanter is empty, and in it we see Spider breaking in and carrying off Polly while drunken Billy lolls helplessly.

As in the hallucinations of The Lost Weekend (1945), the filmmaker has taken us inside the addict’s fantasy.

Other subjective effects, like memories and dreams, were common in silent cinema too, though usually not plunged so deeply in darkness. In De Luxe Annie, Julie Kendall is worried that her husband is taking a risk by setting a trap for two dangerous swindlers. He will pose as an innocent mark and then arrest them when they try to con him. Julie’s concern emerges in a virtuoso split-screen dream sequence in which her husband is shot by the crook.

Later in the film, Julie will lose her memory and become the con man’s confederate, the new De Luxe Annie. The screenwriter’s old friend amnesia transforms an upper-class wife into down-at-heel swindler.

What triggers the amnesia? The most remarkable scene in the film. It’s either a brilliant coup or a happy accident, but either way it can stand as proof of the boiling energies of this era.

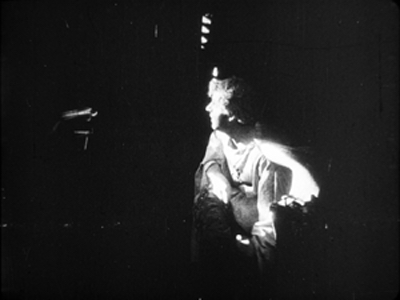

Worried about her husband, Julie follows him to the site of his trap. She goes in through the basement kitchen and enters almost total blackness. She stands in a tiny pool of light before a big double door, and it opens a crack.

Suddenly, and I mean instantly, the doors are wide open and we get a burst of light.

A jump cut has eliminated the movement of the doors swinging apart. (You can see the splice at the bottom of the second frame and the top of the third.) This is a very bold stylistic flourish.

Kristin suggests that it’s something of an accident. The overhead kitchen light is now lit up, and it was common at the time to cut out some frames when a light source is snapped on. That may be what led to this jump cut, though it’s not clear how anyone in the scene could have hit the power switch. In any event, the force of the cut is amplified by the ellipsis; the doors simply pop open.

Another pictorial surprise emerges when Julie moves a bit and it’s revealed that her figure has blocked De Luxe Annie, who’s facing her over the threshold. They start to grapple with one another and move into darkness on the right.

Annie runs off, but Jimmy the con man is fleeing too, and he shows up to wrestle with Julie. A slamming axial cut shows him punching her fiercely in the head. The edge lighting here is remarkable.

Jimmy gets away, leaving Julie to stagger out and into the fog. She’s contracted amnesia. Later she’ll meet Jimmy again and become his new partner in crime.

This scene is even replayed as a brief flashback, when the original Annie recounts to Jennie’s husband the clash that led to Julie’s disappearance.

This is presented in a more unsurprising way, since there’s nothing new to be learned about the fight. The shot shows the full swinging open of the doors and a clearer revelation of Annie’s presence.

All this won’t be news to aficionados of silent film, who are well aware that the 1910s, and then the 1920s, burst with ingenious creativity. But everybody needs reminding, and the rare films I was lucky enough to study are just part of a huge corpus. The official classics by Chaplin and Griffith and others can be restored and reissued again and again, and we’re grateful. Yet if they’re the peaks of a landscape, there are plenty of luscious valleys that remain unexplored.

Problem is, most of the films from which my scenes come are incomplete, often missing entire reels. So they’ll probably never be screened much, or made available on DVD or streaming services. This is why archives remain indispensable to keeping the entirety of our film heritage, fragments and all, available to researchers. It’s also why I wrote this entry, to share with you my enjoyment of films you may never have a chance to see.

More broadly, scenes like these help us nuance our thinking about those films we do know well. For one thing, they indicate just how rich the creative energies of the 1910s were, and how many options were not embraced by…oh, let’s say for example D. W. Griffith.

For another thing, if these neglected works throw up willy-nilly an alcoholic’s hallucinations, an anxious wife’s dream, a plot based on amnesia, and a strategic replay of a crucial scene, we ought to think twice about claiming that such storytelling strategies are somehow unique to film noir, or the zeitgeist of the 1940s–or our movies today, which continue to use them.

American commercial cinema has drawn on particular themes, plot structures, formal designs, and narrational strategies again and again throughout the decades. My book Reinventing Hollywood floats the claim that silent-cinema narrative devices like flashbacks and subjective sequences went somewhat quiet during the 1930s but were brought back fortissimo in the 1940s, when sound techniques could raise them to a new level of intensity. And I’ve been at pains to argue over the years that we still encounter them.

Again, no surprise once we think about it. This is just history at work: the continuity of a powerful, proven storytelling tradition. Once we’ve learned to love darkness, we can’t give it up.

Again I must give my thanks to the John W. Kluge Center for providing me a long stay at the Library of Congress. The Moving Image Research Center was my host, and so I’m grateful to Mike Mashon, Greg Lukow, Karen Fishman, Dorinda Hartmann, Josie Walters-Johnston, Zoran Sinobad, and Rosemary Hanes. They’re doing their utmost to preserve our film heritage.

For information on the survival of US silent films, download David Pierce’s indispensable study, done for the Library of Congress. The information on Paramount is on p. 41.

Kristin’s article is “The International Exploration of Cinematic Expressivity,” in Film and the First World War, ed. Karel Dibbets and Bert Hogenkamp (Amsterdam University Press, 1995), 65-85. She discusses American lighting practices of the period in The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960 (Columbia University Press, 1985), 223-227. In the same volume in discussing film noir I consider the established practice of chiaroscuro for scenes involving crime and mystery (p. 77).

The most in-depth account of Paramount’s lighting styles is Lea Jacobs’ article “Belasco, DeMille and the Development of Lasky Lighting,” Film History 5, 4 (December 1993), 405-418. This is a good place to record my deep debt to Kristin, Lea, and Ben Brewster, for years of tutelage in what makes the 1910s so important.

There are many good books on film noir, but the most comprehensive reflection on the category’s many implications is James Naremore’s More Than Night: Film Noir and Its Contexts, 2d ed. (University of California Press, 2008).

For more on 1910s film style, see this video lecture and this category of blog entries. I talk about other forays into the LoC collections here and here.

Lately, two video distributors have brought out less-known films from the period. There’s DeMille’s The Captive (1915) from Olive, and Irvin Willat’s Behind the Door (1919). The somewhat noirish frame below is from the latter. Flicker Alley, whose commitment to silent cinema from all countries has been extraordinary, deserves our thanks for making the San Francisco Silent Film Society’s restoration of this sensational, and sensationalistic, film available. For more on this restoration, visit the Flicker Alley site.

Behind the Door (1919).

Wisconsin Film Festival: Cutting to the chase, and away from it

Nocturama (2016).

DB here:

Despite my recent jab at D. W. Griffith, I gladly give him credit for making crosscutting a central technique of narrative cinema. Using editing to switch our attention from one story line to another is a fundamental resource of moviemaking everywhere.

Crosscutting is most apparent in those passages of quickly alternating shots that build tension during chases and last-minute rescues. That’s a prototype of what we credit Griffith with consolidating. But crosscutting is used outside such climactic stretches. Hollywood silent features often crosscut story lines throughout the film, without pressure of a deadline and without much happening in some lines of action. It seems to be a way that filmmakers found to keep the audience aware of many story strands.

Crosscutting is a cinematic version of a very old narrative strategy, that of alternating presentation. Once you have several story lines, you can switch among them. Homer does this in the Odyssey, interweaving Ulysses’ wanderings, Telemachus’ efforts to find him, and Penelope’s holding off the suitors.

Homer initially handles these lines in large blocks, in separate “books.” After attaching us to Telemachus in Books 1-4, Homer shifts us to Ulysses for a long stretch. Such interlacing can be found in medieval narrative too, and of course it dominates modern novels, with chapters shifting among action lines and character viewpoints.

Crosscutting large chunks can give way to shorter bursts. Ulysses’ travels occupy several books, but as he approaches Ithaca, Homer interrupts Book 15 to switch back and forth between him and Telemachus, also headed for home. In cinema, this sort of accelerated crosscutting, often driven by a deadline, has become identified with Griffith’s The Lonely Villa (1909), A Girl and Her Trust (1912), and other Biograph shorts. He lifts the principle of crosscutting to a vast scale in his features. The Birth of a Nation (1915) alternates North and South, home front and battlefront, carpetbaggers and Klansmen in a novelistic fresco.

Crosscutting usually implies some degree of simultaneity. While Telemachus searches for his father, Ulysses leaves Calypso and the suitors run riot in the palace. The notion of actions taking place at more or less the same moment is especially important in chases and last-minute rescues.

As a plot reaches its climax, there can be a sort of site-specific crosscutting too. Once Ulysses and Telemachus have joined forces to slaughter the suitors, Homer’s narration sometimes switches among areas of the fight, as in the battle scenes of the Iliad. While father and son hold off the suitors in the main hall, two servants capture one suitor in a storeroom. We recognize this technique of adjacent alternation when novels and films gather all the major characters in one spot for the climax and shuttles among them.

Crosscutting remains a basic filmmaking tool for most movies on our screens. Where would the Fast and Furious franchise be without it? But some contemporary filmmakers have made fresh uses of the technique. In Inglorious Basterds, Tarantino adopts the big-segment option, alternating lengthy blocks of action before using faster crosscutting when characters converge at the climax. Christopher Nolan has experimented with various tactics, including crosscutting different phases of the same action (Following) and crosscutting among embedded segments, dreams within dreams (Inception).

So there are still lots of options out there to be explored. Just look at some films shown at our Wisconsin Film Festival. Beware, though, of light and heavy spoilers.

Attachment plus anxiety

Frantz (2016).

At one end of the spectrum: Must you always use crosscutting? Wigilia, a charming short feature by Graham Drysdale, suggests not.

It’s built on two Christmas eves a year apart. In the first, a Polish refugee who cleans house for a brusque businessman is alone for the holiday and in his apartment prepares the traditional holiday meal—not for herself but for her absent family. She’s interrupted by the businessman’s vaguely hippy brother, and the two learn about each other as they share the meal. In the second evening, after the businessman has left the apartment to his brother, she returns and they bond more intensely.

Apart from an inserted dream sequence, we stay within the apartment. This concentration derives from the production circumstances; Graham explains that he was given a chance to make the film in short order, and to keep it manageable he came up with the idea of limiting the locale. He shot 53 minutes of footage in five days in the apartment, then did the two final scenes in two days. The narrowly focused drama, with many lines improvised, has no need for the free-roaming tactics we associate with crosscutting.

Crosscutting tends to give us a fairly unrestricted range of knowledge; often we know more than any one character. In The Girl and Her Trust, the telegraph operator holding off the robbers can’t be sure that her boyfriend is rushing to her rescue, and he can’t know how close the robbers are to seizing her. Alternatively, when we’re mostly restricted to one character, we don’t find a great deal of crosscutting.

That’s the case in François Ozon’s Frantz, a remake of Lubitsch’s Broken Lullaby (1932), also shown at WFF. Anna’s fiancé Frantz has been killed in the Great War. Out of sympathy his parents have taken her in and treat her as a daughter. But when she sees Adrien, a melancholy Frenchman, haunting Frantz’s grave, she gets curious. Most of the ensuing film is restricted to what Anna learns,

Adrien visits the family. Flashbacks lead us to think he’s what he hesitantly claims to be: a friend of Frantz from prewar Paris. But he has been pressed to tell the parents what they wished to hear. Adrien actually came to the village to beg their forgiveness for killing Frantz on the battlefield, where they met for the first time. Although we surely have reservations about the sad, apprehensive young man, we don’t learn the truth until Anna does, at about the midpoint of the film’s running time. By this time she has fallen in love with him.

There is some alternation of viewpoint in the film. A few scenes attach us to Adrien during his stay in the village, chiefly when he confronts bitter locals who still consider France their enemy. Still, these scenes don’t give us much direct information about the true backstory. And after Adrien has left and Anna has sought to keep the parents in the dark about the past, we remain attached to her. No crosscutting shows us Adrien’s return to France and his life there. As a result, we’re able to feel curiosity and suspense when Anna decides to track him down. The revelation of his civilian life raises a set of unexpected conflicts.

Both Wigilia and Frantz show that avoiding crosscutting can be a powerful way to keep our attention fastened on characters, the better to let their words and behaviors, as well as their inner lives, get primary emphasis. Crosscutting yields a panorama, while refraining from it can aid portraiture.

Crosscutting as usual

The Student (2016).

More toward the center of the spectrum lies ordinary crosscutting, the alternation among scenes that provide a broad perspective on the action. In Arturo Ripstein’s Western Time to Die (1965), the plot alternates between scenes featuring the returning convict Juan Sayago and episodes showing the reactions of different townsfolk—chiefly the sons of the man he killed. We also learn of efforts from women in the town to prevent the sons from taking revenge. This “moving-spotlight” narration isn’t perfectly omniscient, though. The plot gradually fills in information about what led up to Sayago’s crime, while revealing that the sons’ mission would amount to avenging a dishonorable father.

A similar sequence-by-sequence approach is seen in The Student, aka The Disciple, a Russian film by Kirill Serebrennikov. A fanatical teenager has become the scourge of the classroom, barraging teachers and pupils with Bible quotations and denunciations of bikinis. His mixed-up fundamentalism, which leads him at one point to challenge evolution by donning a gorilla outfit, is unpredictable and a pure power trip, Biblical bullying.

His mother can’t manage him, the administrators are reluctant to take stern action, and the school priest sees him as a potential recruit to the clergy. Only one teacher, Elena, challenges him with a mix of humor and sympathy. But to combat his increasingly wild behaviors, which include making himself a full-size cross which he can stretch out on, she too sinks into Scripture. She hopes to quote the Bible back at him and dislodge his dogmatism, but she too becomes obsessed and estranges herself from her boyfriend. Meanwhile, Venya gets his one true disciple, a limping underdog, and his campaign against homosexuality, science, and secularism turns violent.

A good part of the narration locks us in to Venya’s Dostoyevskian ferocity, thanks to a restless use of the “free camera” in lengthy following shots. (The film has only about 150 shots in 113 minutes.) But we do range more widely to get a broader view. The moving spotlight shows the mother’s frantic consultations with school officials, and Elena’s clashes with them, as well as with her boyfriend. Still, the climactic scene, which assembles all but one of the characters in a single meeting, has no need of a broader view. Like Wigilia, The Student draws its final power from drilling down into a confrontation around a table.

Gaps and folds in time

Killing Ground (2016).

Griffith rang many changes on his last-minute-rescue template, and one of the most startling occurs in Death’s Marathon (1913). A dissolute husband, bored with his life, decides to commit suicide and notifies his wife by phone. She calls the family friend, who races to prevent the death. Surprise: He’s too late.

A hundred-plus years later, crosscutting builds and then deflates suspense in the Romanian film Dogs, by Bogdan Mirica. There are two protagonists: Roman, a city fellow who has inherited his grandfather’s idle farm, and Hogas, the police chief. Both face off against sadistic hoodlum Samir and his thugs. A human foot has popped up (literally, in the first shot), and Hogas tries to trace its owner, while Roman decides how to dispose of the farm. Samir explores other possibilities, none very savory.

At first we’re restricted to Roman, who is frightened by distant lights and gunshots out on the property, and Hogas, who doggedly pursues his investigation. The alternation between them keeps Samir offscreen for some time. When he surfaces in a suspenseful drinking bout with Roman, and when Roman’s girlfriend comes to pay a visit, the threats start building.

The climax starts out as pure Griffith. Mirica crosscuts Roman’s drive back to rescue his girlfriend, Hogas’ pain-ridden walk to the farmhouse, and Samir’s ominous approach to the isolated woman. Interestingly, the pace of the cutting doesn’t much accelerate in these last moments; there isn’t a lot of alternation, and the emphasis is on prolonged actions (Hogas’ trudging pace, interrupted by coughing up blood, and Samir’s laconic dialogue with the girlfriend).

By the time Hogas arrives, he finds he’s too late. The conventional mystery and suspense of the first stretch are undercut by showing us only the eerie aftermath of a violent climax. Art-cinema norms can de-dramatize crosscutting, but the maneuver remain a revision of what Griffith tried for in 1913.

Three years after Death’s Marathon, Griffith showed the possibility of crosscutting radically different time frames. Intolerance (1916) interweaves four historical epochs while using crosscutting within each one as well. Since then, crosscutting has sometimes been used to juxtapose past and present (The Godfather Part II, The Hours), or alternative futures (Sliding Doors), or a real story and a fictional one (Full Frontal). Interestingly, Griffith is a bit more daring than these directors. These films usually alternate sequences or entire blocks. At first Intolerance does that too, using titles to mark the shift among its four eras. But as the film reaches its climax, Griffith cuts freely from one period to another. These shot-to-shot time shifts, jumping centuries in the burst of a cut, remain an audacious formal discovery.

In all these examples, we’re cued to realize when we move to another period. But Killing Ground, a grueling Australian thriller by Damien Power, doesn’t announce its time-shifting. It exploits our default assumption that crosscutting implies more or less simultaneous action.

At first Killing Ground does give us rough simultaneity, alternating between the yuppie couple, Ian and his fiancée-to-be-Sam, and a pair of gun-loving locals. But then the couple make camp near another family’s tent.

Through careful use of eyeline matches and other continuity cues, the narration welds together actions that are actually taking place at different times. The family’s evening meal and their foray into the woods happen well before Ian and Sam arrive, but the cutting implies that the two groups are living side by side.

Like Griffith, at moments Power shifts between the two periods on a shot-by-shot basis. Small disparities, like a baby bonnet and the placement of the campers’ vehicles, accumulate. By the time Ian follows one of the psychopaths into the woods, we realize that earlier events have been salted through the present-time action, the better to delay revealing the family’s fate. From then on, orthodox crosscutting takes over as Ian runs for help and Sam tries to hold the rampaging peckerwoods at bay.

The kids aren’t alright

At the distant end of the spectrum, how about building a whole movie out of full-blown crosscutting? A sustained example at WFF was Bertrand Bonello’s Nocturama. (Major spoilers ahead.)

For the first fifty minutes or so, we follow nine young people silently threading their way through Paris. They ride the Métro, pace along the street, pair up, separate, crisscross, and assemble at four sites—a line of parked cars, an office building, a Ministry, a statue of Joan of Arc. They’re setting bombs.

We can identify them only through their looks and behaviors. David and Sarah touch fingers fleetingly on a train. We learn from flashbacks that Samir and Sabrina are sister and brother, and their friend is the younger African Mika, all presumably from emigrant families. Flashbacks also show them meeting to plan their action and, once set on course, dance the night away.

There’s an unexpected shooting, but the bombs go off more or less as planned. The group assembles in an upscale department store to meet another confederate, the security guard Omar who will host them overnight. This brief “nodal” moment of unification melts away. Crosscutting follows them as they wander from floor to floor in a parallel to their passages through Paris.

The first section merges the art cinema’s best friend, the prolonged walk, with a thriller-based suspense: we don’t really know what they’re up to until we see a pistol at around 18 minutes and bomb materials somewhat later. The threads knot when we see a quick montage of the bombs.

This fine-grained crosscutting looks ahead to the fragmentary handling of the action in the department store, where the moving spotlight shifts rapidly as the conspirators disperse, assemble in pairs or trios, and disperse again.

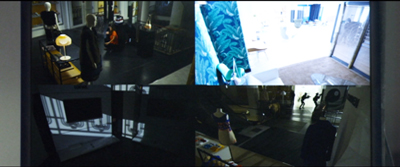

Crosscutting is the principal way filmmakers imply simultaneous action, but a lesser option, often favored by Brian De Palma, is the split screen. Bonello uses this device to show the result of the bombings. The shot looks forward to the quiet surveillance-camera display in the security office as the police prowl the shopping aisles. We see the kids moving from quadrant to quadrant, with an occasional flare marking a nearly soundless kill.

The terrorists’ motives are barely sketched, and they’re a cross-section of middle-class and working-class kids. Some are unemployed, others have low-end jobs, while others are on track for professional careers. A flashback shows several, perhaps meeting for the first time, while waiting for job interviews. The film’s second large part paints them as victims of consumer lust as they try on upscale fashions and make-up, but the point isn’t hammered home. To some extent they’re just killing time in what they think is a safe house.

Nocturama‘s crosscut climax balances, in more condensed form, the first section, as the conspirators are discovered by the police. At one point, an innocent who has come upon them by accident gets more emphasis than the gang members. His final moments are replayed through multiple viewpoints, as if the stranger’s fate drives home to them what death looks like up close. Soon enough each one will know exactly.

It might seem the height of film nerdery to join up films seen at a festival through their different uses of one technique. But is it any more of a strain than those journalistic accounts of how a batch of festival choices reflects The Way We Live Now? Every Berlin or Cannes or Toronto seems to bring forth think pieces looking for a common thread among radically different films, hoping to find today’s social mood in movies begun perhaps years before? Like most zeitgeist readings, they’re pretty easy to whip up.

But technical choices are more concrete than hints of the mood of the moment. Moreover, if you’re interested in cinema as an art, it can be enlightening to reveal the variety of creative options that are still available. The art may not progress, but our understanding of it can. And it’s heartening to find filmmakers refreshing traditional techniques to give us powerful experiences.

Just as important, studying how our contemporaries find new possibilities in something as old as crosscutting can encourage ambitious filmmakers today. The menu is open-ended. There’s always something new, and rewarding, to be done.

We had a wonderful time at this year’s Wisconsin Film Festival. Thanks to all the people and institutions involved, and especially the programmers Jim Healy, Mike King, and Ben Reiser. Each year it just gets better.

Wigilia is currently streaming on Amazon. Nocturama has just gotten a US distributor, the enterprising Grasshopper Film.

Good discussions of interlaced plotting in medieval tales are William W. Ryding, Structure in Medieval Narrative (Mouton, 1971) and Carol J. Clover, The Medieval Saga (Cornell University Press, 1982). Yes, it’s Carol “Final Girl” Clover.

For Tarantino’s use of block construction and time-bending, go here. We discuss Nolan’s penchant for crosscutting in this entry and that one, and at greater length in our e-book on his work.

Movies in the mountain, and on the machine

DB here:

I’m back in Madison from 2 1/2 months in Washington, DC. under the auspices of the John M. Kluge Center, where I was this year’s Chair of Modern Culture. This kind appointment allowed me to pursue my research into 1910s American film style, than which nothing could be more fun. Along with that were some extramural activities. The most spectacular one was our Kluge field trip into the most overwhelming media archive in the world–the bulging-biceps caped crusader of film, TV, and sound preservation.

Treasures under Mount Pony

Dr. Strangelove could have come up with the idea. If the Russians attack the US, better have a deep underground vault for storing a few billion dollars to replenish currency supplies on the East Coast. So in the Culpeper, Virginia countryside build a gigantic secret bunker. Include facilities for housing 500 or so personnel to keep the government, or what was left of it, running for a month. Add amenities like a pistol range and refrigeration units to cool cadavers that couldn’t be buried outside. Getting assigned here in nuclear winter would definitely count as subterranean homesick blues.

This super-secret complex was completed in 1969. It boasted foot-thick concrete walls and was surrounded by barbed wire and machine-gun nests. By 1992, the bombs had failed to fall, so the complex was decommissioned and eventually offered for sale. After a major grant to the Library from the David and Lucille Packard Foundation, a long-time friend of American film history, the building was transferred to the Packard Humanities Institute . The facility was renovated thanks to over $260 million of Packard and Congressional funding. A lot, yes, but in 2017 dollars that comes to about $402 million, and Beauty and the Beast has scared up about twice that over the last couple weeks.

The renovation turned this vast bank vault/bomb shelter into the world’s most colossal and up-to-date media storage and preservation facility. Opened in 2007, the National Audio-Visual Center is also known as the Packard Campus. Its collection of films, videos, and audio records, along with posters and documents, come to over six million items sitting on ninety miles of shelving. With 80 per cent of it sunk below ground, it was designed to be an exemplary green building, with a vast gardened roof.

Thanks to the energy of Kluge Center director Ted Widmer and his colleagues, we had a chance to visit the place. Greg Lukow, Chief, NAVCC–Packard Campus, and Mike Mashon, head of the Moving Image section, led us in a labyrinthine, carefully organized three-hour tour of the dazzling facility.

I can’t convey all that we learned about conservation of film, TV, sound recordings, and digital media. Rest assured that the hundred-plus people working away here in state-of-the-art conditions are striving mightily to save media artifacts for you and me and our heirs. Here are some high points.

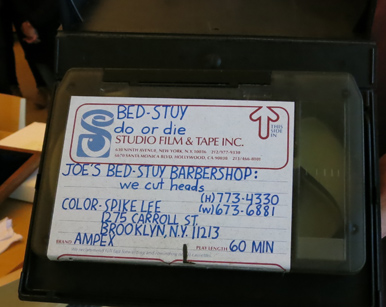

Mike introduced the visitors to the moving-image formats of the media conserved at the facility, everything from film and videotape to Digital Cinema Packages. Spike Lee’s first film, as a copyright deposit, is there too, on Ampex tape.

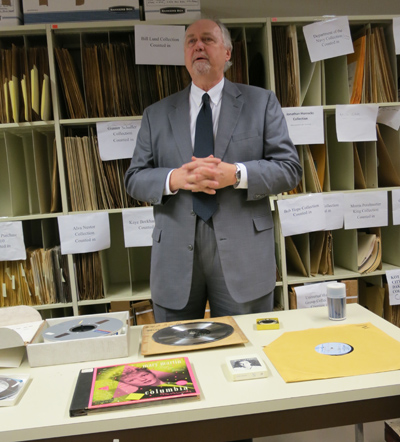

Sound isn’t neglected, as Greg offered a comparable overview of all the audio formats, including cylinder and wire recording. Yes, 8-tracks are also involved. On the right you see the Scully Lathe, a gleaming bad boy that cut disks. Used from the 1930s into the 70s it’s being brought back with the new interest in vinyl records.

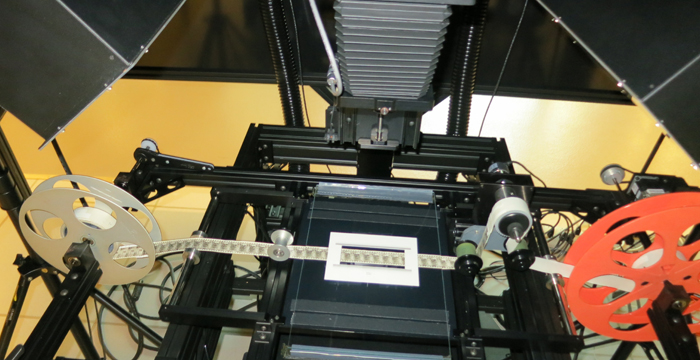

We visited several lab and restoration rooms, including one for wet-gate printing and another for migrating VHS tapes to digital files. Since the latter has to be done in real time, robots are recruited for the job, busily gliding up and down ranks of cassettes.

Of course we had to stop by film vaults, kept a chilly 39 degrees. On the left we see some of the holiest of holies, nitrate vaults. It looks like a Spanish Civil War prison, rows and rows of heavy doors. The vault on the right contains master safety film elements, on both acetate and polyester stock.

What’s a trip to an archive without despoiled artifacts? On the left, a flaking glass-based 16-inch lacquer instantaneous disc from the NBC radio collection. “Instantaneous” means that it was a recording of a live broadcast, and so was probably unique. On the right, we have decomposed nitrate film.

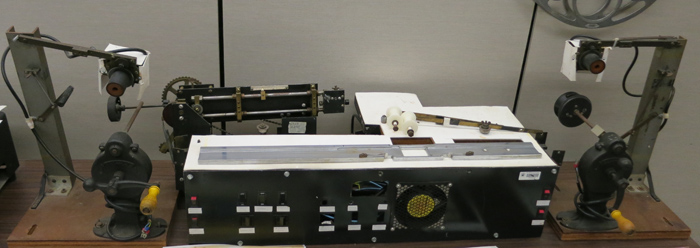

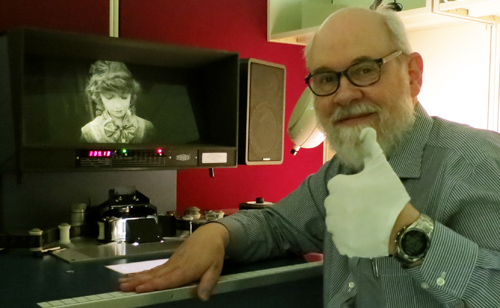

Of enduring interest to cinephiles is the famous paper print collection. Film companies of the earliest years submitted to the Library movies on rolls of paper, to be copyrighted in the manner of still photographs.To be preserved and screened, those had to be turned back into films. During the 1950s that task was fulfilled by Kemp R. Niver in a home-made rig.

He transferred some 3,000 titles to 16mm–not the ideal format, but better than nothing. Some results were fuzzy and jumpy, but many came out okay. I watched several during my stay, including The Hoosier Schoolmaster (1914).

Since then, some excellent 35mm prints have been made from the paper prints, and still more success has been found with digital remastering, which can correct for misaligned frames on the original paper copies.

It was good to learn that film copies of new releases are still being submitted for copyright deposit. An impeccable print of Get Out arrived while I was there, and of course 35mm advocate Christopher Nolan wouldn’t miss a chance to save Inception and other of his works.

But I was dismayed to learn that a great many companies, taking advantage of a loose requirement about what counts as a deposit copy, are submitting DVDs, Blu-rays, and even DVD-R versions of their films. If they can’t submit a print, they should at least provide an unencrypted DCP. Otherwise, scholars and audiences of the future will encounter the digital equivalent of the crawling, scraped deterioration we see with film.

101 movies

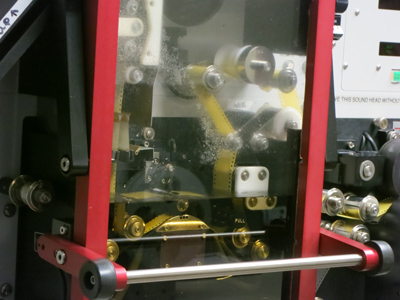

Fortunately for me, 1910s films are still available on film. Viewing prints of films stored at Culpeper are shipped to the James Madison Building in the District. There, in the Moving Image Research Center, they may be viewed on my old friend, the flatbed machine known as a Steenbeck. Every day a Steenbeck patiently awaited my depredations.

The staff of the Reading Room were just superb in helping me order titles and dig up information about them. Above you see the team I worked with: Dorinda Hartmann, Rosemary Hanes, Josie Walters-Johnston, and Zoran Sinobad.

I learned an enormous amount from them, and I enjoyed talking movies with them during our breaks. Others who helped me greatly were Karen Fishman, Research Center Supervisor, MBRS Division; Alan Gevinson, curator of the American Archive of Public Broadcasting; and David Pierce, Assistant Chief, NAVCC–Packard Campus.

My mission was to see as many American fiction features from the 1910s as I could. This was the period when a five-reel film (ca. 60-70 min.) became a dominant format, though shorts and longer films were also being made. I’ve spent about a decade watching largely European films of the period in various archives and in Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato, with results I’ve occasionally discussed on this blog. A visit to the LoC nicely complemented my Continental and Nordic explorations. Although several American films from the period are available on DVD, I’ve tried to see even those in film copies. (Why? Tell you later.)

For a time I was joined by James Cutting, perceptual psychologist extraordinaire, who enthusiastically wanted to watch these old movies. His presence helped me a lot, sharpening my attention to things in the images. Here’s James, skewed, during our nighttime trip to Chinatown for food and Get Out.

In all, across 42 business days (had to take days off for holidays and inauguration), I saw 101 films, 98 from my period and three others for other projects.

Not all the films survive complete. Some lacked one or more reels. That’s a great pity in the case of Lois Weber/ Phillips Smalley’s False Colours (1914), Sunshine Molly (1915), and Idle Wives (1916); William deMille’s The Sowers (1916); William Desmond Taylor’s Ben Blair (1916); and many other stunning projects I got a glimpse of. But a little is better than nothing, as I’ve tried to show in an earlier entry and hope to show in later ones.

A few portions that remained were plagued by deterioration. Usually, that consists of ameba-like creatures swarming over the image. Some decadents wallow in these miasmas, especially on tinted prints. (See Lyrical Nitrate and Decasia.) Me, I can’t romanticize turning a 1910s drama or comedy into a 1960s abstract film. I want to see the story and the style, dammit.

Another form of deterioration yields a ghostly, scraped-off image. Sometimes the decay changes from shot to shot, presumably because at some points the shots were segregated for tinting and toning. Here’s The Caprices of Kitty (Smalley, 1915), with Elsie Janis watching a play. In a gag on celebrity, she’s also an actor on stage (and in drag). After the nice shot of her and her father in the audience, the stage shot makes you shudder.

A first effort to clean it up with Photoshop helps, but still…Makes you remember why all that effort on the Packard Campus is necessary.

Of course a great many copies I watched were gorgeous. Orthochromatic film, with a ton of light dumped on the sets, yields images with incredibly rich gray scales. (My Ilford photochemical black and white couldn’t capture that range.) When we saw this parlor shot from By Right of Purchase, a 1918 Norma Talmadge melodrama, James blurted out, “Clutter!” A connoisseur of dense images, James later ran it through his algorithms and found that it had a spectacular degree of clutter.

Filigreed clutter is another big reason to like the 1910s, and archives like the LoC team are keeping it visible for us.

Deterioration isn’t the only insult these movies suffer. There’s the degradation of them in oft-copied versions. Compare this shot, from Reginald Barker’s splendid William S. Hart film The Bargain (1914), with the image you get if you buy the bootleg DVD.

Shot scale changes because of video cropping, facial expressions become unreadable, the eyes go dark, and that mounted trophy in the back just disappears. Of course things go a lot better with a video version of a film restored by the Culpeper crew (Moving Image Curator Rob Stone in particular). Olive Films has just released Wagon Tracks (1919), a fine William S. Hart film, on a very pretty Blu-ray derived from a tinted Library of Congress restoration.

So it can be done well, though I still prefer to study a 35 print, preferably untinted. Call me cranky.

The Packard Campus visit brought home to me how much effort is spent saving our film heritage. That heritage includes films that are little-known, but deserve better recognition. Watching with me, astonished by the technical ingenuity and wide-ranging experimentation rushing past us, James was reminded of the Cambrian Explosion, that period of origin and rapid diversification among earthly organisms.

It’s an intriguing analogy. A mere dozen years yielded “our cinema,” as I’ve argued in this video lecture–the sturdy prototypes of moviemaking today. Yet along with enduring models of story and style came a cascade of ingenious novelties that weren’t taken up much. The 1920s, for all their innovations, tended to prune away some of the more eccentric but intriguing tendencies that burst out in the 1910s. In my next entry on the subject, I’ll offer some examples.

I owe a tremendous debt to the John W. Kluge Center for supporting my stay at the Library of Congress. Thanks especially to Ted Widmer, Director of the Center, and his colleagues Emily Coccia, Travis Hensley, Callie Mosley, Mary Lou Reker, and Dan Turello. Also I enjoyed enlightening conversations with Peter Brooks, in residency at the Center, and the other Kluge Chairs Timothy Breen, Jose Casanova, and Wayne Wiegand, all embarked on fascinating projects.

Thanks also to all the staff at the Packard Campus, who enthusiastically shared information about their work habits. We’re grateful to Greg and Mike for spending so much time with us.

The digital spoor on the Packard Campus leads far and wide; a Google search will yield you many nifty items. The 2007 plans for the facility are reviewed in this information-packed presentation by Greg Lukow. For something more recent, try the Wired visit by Brian Gardiner. On the digitizing side, see Boing Boing’s extensive coverage, including an interview with Greg. There’s a good half-hour C-span documentary tour led by Mike Mashon. Mike’s blog Now See Hear! offers updates on current Campus events.

Tony Slide’s Nitrate Won’t Wait (McFarland, 2000) remains the essential source on U.S. film preservation. It has some good anecdotes about Kemp Niver, including one involving a pistol and Raymond Rohauer. Criterion has a nifty little film on wet-gate restoration of The Man Who Knew Too Much (1935).

If you’re interested in film research, you need to read James Cutting’s sweeping big-data studies on film. A good summing up of part of it is “Narrative Theory and the Dynamics of Popular Movies.” There’s interesting commentary on it here from a psychologist and here from a screenwriter (who clings to the three-act model). James’s book on the formation of the canon of Impressionist painting has been invoked in Derek Thompson’s book Hit Makers: The Science of Popularity in an Age of Distraction (Penguin, 2017), 23-26.

For more on visual clutter, see this paper on clutter and visual search, of which Tim Smith, master of eye movements, is a co-author; and two papers specifically on movies, by James, one with Kacie Armstrong: here and here.

DB makes Lillian bashful in The Lily and the Rose (1915).