Archive for the 'Silent film' Category

Vertov, sound technology, and 3D: Recent Blu-ray releases

The Man with a Movie Camera.

Kristin here:

Every now and then we accumulate a few new DVDs and Blu-ray discs and write up a summary of each. This entry is the first time when all the discs discussed are Blu-ray. In fact, none of these releases is available in the DVD format.

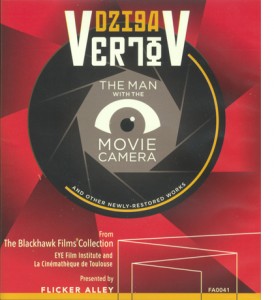

Vertov and more Vertov

Soviet director Dziga Vertov is known primarily for The Man with a Movie Camera (1929), one of the most revered silent films. It is a documentary, an experimental film, a city symphony, and a witness to Soviet society in the late 1920s, all in one. Flicker Alley has done great service to silent Soviet cinema with its Landmarks of Early Soviet Cinema and the serial Miss Mend by Boris Barnet and Fedor Ozep. Now it has brought out a Blu-ray disc of a remarkable 2014 restoration of The Man with the Movie Camera.

This version is based largely on a print struck from the original negative and left by Vertov with the Filmliga of Amsterdam, an early cine-club. It subsequently passed to the Nederlands Filmmuseum. The restoration added clips culled from other archival prints to fill in gaps in this copy, producing an edition that will be a revelation to many who are used to the scratchy, contrasty, and cropped prints that have circulated for decades.

For one thing, seeing that missing left side of the frame makes a big difference. A booklet included with the disc points out that modern versions are usually taken from sound prints of the film, which required that the left portion of the frame be reserved for the sound track. As a result, that area of the image was cropped out. This new release restores the full-frame original, and the result is dramatically different from earlier versions. Its visual quality is also impressive (see top).

with the disc points out that modern versions are usually taken from sound prints of the film, which required that the left portion of the frame be reserved for the sound track. As a result, that area of the image was cropped out. This new release restores the full-frame original, and the result is dramatically different from earlier versions. Its visual quality is also impressive (see top).

Yet Flicker Alley has been too modest in emphasizing this as a release simply of The Man with a Movie Camera. The full title of the release is “Dziga Vertov: The Man with the Movie Camera and other Newly-Restored Works.” Yet the “Other Newly-Restored Works,” featured in very small print on the cover, are hardly incidental. They include features that many researchers and cinephiles have long wished that they could view in good prints–or any prints at all.

These other works include most of Vertov’s famous features of the 1920s and early 1930s: Kino-Eye (1924), his first feature; Enthusiasm: Symphony of the Donbass (1931), his first sound feature; and Three Songs about Lenin (1934), a celebration of the tenth anniversary of the death of Lenin.

I don’t think any of these films is as important as The Man with the Movie Camera. For me, Kino-Eye is the most charming, with candid depictions of peasant festivals and the like. It was Vertov’s first opportunity to stretch his ambitions after years of work in newsreels and documentaries. It has a spontaneity that perhaps disappeared in the later features.

The disc includes an informative booklet that discusses both the films and their restorations. As an extra, there is the 1925 Kino-Pravda newsreel episode that Vertov made to commemorate the first anniversary of Lenin’s death. It incorporates rare newsreel footage of Lenin, cutting it together in ways that look like modern gifs.

The visual quality is inevitably variable, with the earlier films looking contrasty, but these are no doubt the best versions that we are likely ever to have. This Man with a Movie Camera supersedes the one from the BFI (in the UK) and from Kino (in the USA), though many will want to have the latter for its lovely score by Michael Nyman. The Flicker Alley version has a very different, but highly appropriate, score by the Alloy Orchestra.

Not all of Vertov’s early features are included. For those who want more, Edition Filmmuseum’s release of A Sixth Part of the World (1926), The Eleventh Year (1928), both with a Michael Nyman score, and one shorter film plus a documentary on Vertov, remains a necessity.

3D curiosities

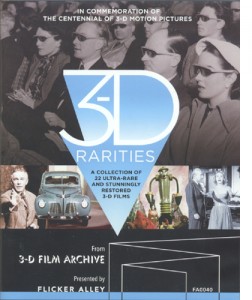

Flicker Alley has also developed a specialty in releasing DVDs and Blu-rays exploring film formats. The company has paid particular attention to Cinerama (This Is Cinerama, Cinerama Holiday, South Seas Adventure, Windjammer, Seven Wonders of the World, and Search for Paradise). Now, in celebration of the centennial of 3D exhibition , it branches out into 3D with 3-D Rarities, described as “A Collection of 22  Ultra-rare and Stunningly Restored 3-D Films.” (Since we cannot reproduce 3D frame enlargements, the images below are taken from the Flicker Alley webpage just linked.)

Ultra-rare and Stunningly Restored 3-D Films.” (Since we cannot reproduce 3D frame enlargements, the images below are taken from the Flicker Alley webpage just linked.)

This BD brings together a thoroughly heterogeneous collection of short items, assembled into two programs. The first, “The Dawn of Stereoscopic Cinematography,” covers the years from 1922 to 1952, with short films made outside mainstream Hollywood. Some test footage by Edwin S. Porter and William E. Waddell shown in 1915 no longer survives, so the earliest films on the program are “Kelley’s Plasticon Pictures” (1922-23), including Thru’ the Trees, a travelogue of Washington, D. C. featuring shots of famous buildings framed primarily by foreground tree branches to create planes in depth.

The items that follow range from promotional films to animated shorts to a burlesque comedy featuring two fairly tame striptease segments and two fairly unfunny comedians. A  promotional film for Chrysler shown at the New York World’s Fair (New Dimensions, 1940) traces the assembly of a new Plymouth in great detail and with impressive animation, with the parts hopping around and sliding into place on their own.

promotional film for Chrysler shown at the New York World’s Fair (New Dimensions, 1940) traces the assembly of a new Plymouth in great detail and with impressive animation, with the parts hopping around and sliding into place on their own.

For many the highlights of this first program will be four shorts from the National Film Board of Canada, two of them by Norman McLaren. The first, Now Is the Time (1951), uses the filmmaker’s familiar drawn-on-film style (right), while the second, Around Is Around (1951), employs an oscilloscope to create more abstract patterns.

Films by two of McLaren’s colleagues are also included: O Canada (1952) by Evelyn Lambart and Twirligig (1952) by Gretta Ekman. These films are among the only ones on the whole program where objects are not thrust or thrown “out” at the audience.

The first program ends with an advertisement, Bolex Stereo (1952), a camera which supposedly was going to bring 16mm 3D home-movies into people’s living rooms. The complicated technology demonstrated shows why the idea did not catch on.

The second program, “Hollywood Enters the Third-Dimension,” consists mainly of trailers interspersed with a few shorts. The trailers include It Came from Outer Space and Miss Sadie Thompson (both 1953). One fascinating film is Rocky Marciano vs. Jersey Joe Walcott (1953), and I say this as one who has no interest in boxing. This 16-minute black-and-white film starts at the training camps of the two opponents and moves on to the match itself, in which Marciano famously knocked out Walcott in less than two minutes. The in-ring controversy over the call occupies the last part of the film, giving the whole thing a distinct dramatic shape. Multiple-camera filming and 3D add visual interest.

Stardust in Your Eyes (1953), a comedy short starring comic and impersonator Slick Slavin (aka Slaven in the credits), is said in the program notes to have been “a big hit at 3-D festivals. Judge for yourselves, but I advise keeping a finger on the next-chapter button for this one.

Few of these shorts can be said to be important classics of the 3D repertoire, but overall one gains a sense of the surprising range of films made with the process. One also learns that thrusting guns, spears, swords, and even sling-shots toward the audience, as well as throwing stones and other missiles at them, never grow old as far as the makers of these films are concerned. We have a pistol aimed at us in one of the “Kelley’s Plasticon Pictures” from 1922 (below left) and a rifle in the trailer for Hannah Lee (1953, right).

At least we now have the 3D version of Mad Max: Fury Road to recharge this particular visual trope in highly original ways.

Sound marches on

Way back in 2008, when this blog was a mere two years old, I reported on the first volume of a two-disc set of DVDs inaugurating the highly ambitious project, A Century of Sound: The History of Sound in Motion Pictures. That first volume covered the period to 1932. This one is entitled “The Sound of Movies: 1933-1975.” There was of course a lot more recorded sound in that period, and the new set stretches to four Blu-ray discs, for a total of over twelve hours of running time.

I can’t claim to have watched all those hours, but every section I sampled boasted extraordinary amounts of information. Robert Gitt, who originated the project with a 1992 lecture, again narrates. The coverage includes a huge number of rare diagrams, photographs, documents, and demo reels. In addition, many of the chapters add clips from films that contained the most innovative sound techniques of their day. The Garden of Allah, Okhlahoma!, Medium Cool, and many other titles are excerpted in superb copies.

The set as a whole is a gold mine for specialist researchers and technology buffs. The discs include long and detailed passages on such topics as push-pull recording and noise reduction, the latter a crucial challenge to the sound-recording industry for decades. Teachers who searched assiduously could find many clips suitable for classroom use.

A fair amount of the material ought to be interesting to nonspecialists too. For example, the third disc includes a history of early multi-channel and directional sound. The section on early stereophonic systems is fascinating, with its coverage of Leopold Stokowski’s participation in the two most important early films to introduce this new technology to a popular audience: 100 Men and a Girl (1937) and Fantasia (1940). We get generous clips from each. From 100 Men and a Girl, we see most of the famous scene in which an orchestra plays on different levels of Stokowski’s house and multiple channels allow sonic “close-ups” of each type of instrument over close views of that section of the orchestra:

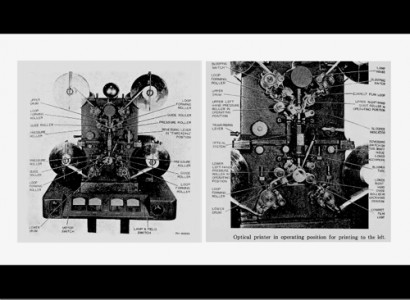

A thorough history of Fantasia includes the image below, typical of the sorts of material The Century of Sound presents: the Fantasound optical printer invented in order to print the multiple optical tracks used for the film’s stereo.

And someone obviously could not resist including a goodly dose of the short dances from the Nutcracker Suite section of the film (see bottom).

The Century of Sound is not for sale commercially. It “is available free of charge to educational, archival and research institutions and to qualified individual educators, researchers and scholars as a not-for-profit educational resource.” There is a modest fee for shipping. For information on ordering, write to CenturyofSound@cinema.ucla.edu.

Flicker Alley’s release of This Is Cinerama provoked David to a survey of Cinerama aesthetics in an earlier entry.

Fantasia.

Homunculus and his friends

Sappho (1921).

DB here:

Of the big-ass explosion movies, only two items in this summer’s spate of them have intrigued me. I liked Mad Max: Fury Road well enough, but not as much as MM2 and 3. I look forward to Mission: Impossible—Rogue Nation, in a series for which I have much affection. As for the arthouse releases, the ones I’ve already seen are A Pigeon Sat… (good but not as sardonically bizarre as earlier Andersson, methinks) and About Elly. That one is a masterpiece.

I have stronger reasons than indifference for missing so much, and for tardy blogging besides. I’ve been on my annual trip to Belgium for research and lecturing in the Summer Film College. As a result, your recent movie experiences and mine have been divergent, perhaps even insurgent.

Apart from two screenings in the Brussels Cinematek’s Hou series (their restoration of Green, Green Grass of Home, gorgeous vintage print of City of Sadness), I spent the last four weeks watching 35mm prints of movies by Godard, movies starring Burt Lancaster, and assorted silent films from the 1910s and 1920s. I also re-met one of the most charming directors I know of, and in general had a hell of a time.

Today’s entry focuses on my archive work. Next up, a report on the Summer Film College.

Conrad’s many moods, mostly unhappy

Landstrasse und Grosstadt.

The archive stuff was recherché. I’ve been trying to see as many 1910s and early 1920s features as I could, but this time around I didn’t catch anything as mind-bending as Jasset’s Au pays de ténébres (1911) or Doktor Satansohn (1916) or Fabiola (1919) or I.N.R.I (1920), encountered on earlier visits to the Cinematek. I did get further confirmation that in Germany the “tableau style” exploited so vigorously in Europe and somewhat in America in the 1910s, was pretty much replaced by Hollywood-style editing by 1920. And I got some welcome doses of Conrad Veidt, another favorite in this vicinity.

In Die Liebschaften des Hektor Dalmore (“The Liaisons of Hektor Dalmore,” 1921), Veidt plays a callous playboy who keeps on retainer a man who looks very much like him. It’s a lifestyle choice. When a compromised woman’s father demands that Hektor do the right thing, he sends out his double to marry her. Surprisingly, the double isn’t rendered through trick photography. Richard Oswald, always a fast man with a gimmick, found a pretty good Veidt lookalike, which can’t be easy to do.

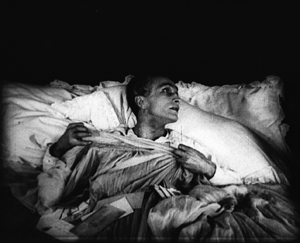

The hero’s Casanova complex carries him from dalliance to dalliance, and as you’d expect in a twins situation, there are confusions between the real and the fake Hektor. Fights and abductions liven things up. The climax is a duel in which the real Hektor, overconfident, learns to his grief that an outraged husband is a better marksman. The scene is handled through brisk shot and reverse-shot, garnished with an over-the-shoulder shot as Hektor aims his pistol. And there are dashes of mildly Expressionist set design (furnished by Hans Dreier). Veidt in a phone booth does the décor proud. But he doesn’t need fancy sets to project a feeling: on his deathbed, his expression and his clutching fingers show a man bereft of erotic illusions.

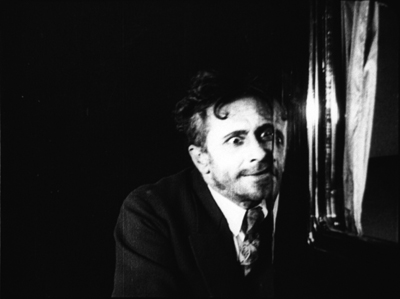

The other Veidt vehicle lacked doubles but not ambition. Landstrasse und Grosstadt (“Village and City,” 1921) casts him as Raphael, a wandering violinist who teams up with Migal, an organ grinder. They become a popular act in the big city, and as Raphael’s playing improves, Migal becomes his manager. Nadia, a woman who joins them, falls for Raphael and shares his success. But in an accident he suffers a hand wound and his career slumps. Migal sees his chance to move in on Nadia. Perhaps this shot gives you a hint of his designs.

Actually, most of Landstrasse and Grosstadt isn’t as hammy as this. A very nice shot shows Raphael in silhouette approaching a mansion to hear his rival Cerlutti give a salon concert. And of course Conrad gives the blind violinist a delicate, spectral pathos, as shown above.

Artificial man lurks in the shadows, destroys humanity

Sappho.

All the films I saw broke down scenes into many close shots, reminding us that Caligari (released 1920) probably wasn’t typical of German staging or cutting of that moment. It now seems to me almost consciously anachronistic, rejecting the reverse angles and precise scene breakdown that were becoming common. In Die Ehe der Fürstin Demidoff (“The Marriage of Fürstin Demidoff,” 1921), when a governess drags a recalcitrant girl back to her bedroom, the action is split up into four shots, all of different scales from close-up to long-shot.

Although I saw a fragmentary print of Sappho (1921), it’s clear that in parts it has the audacious monumentality of a Joe May production. The most staggering shot is that of the Opera surmounting today’s entry, but there’s no shortage of striking images. Above I include a shot of a madman that, thanks to window reflections, suggests his split-up psyche.

Sappho also doesn’t shirk editing effects either. During a frantic automobile ride, there are glimpses of hands on a steering wheel, a foot on brakes, panicked passengers, and POV shots through the windshield. Forty-nine shots rush by in a flurry, anticipating similar sequences in French Impressionist films like L’Inhumaine (1924). Feuillade was experimenting with rapid cutting of action at about the same time.

The most impressive, and nutty, film in this batch came from Homunculus, the largely lost German serial released through 1916 and into early 1917. The script was written by one of the blog’s favorite peculiar directors, Robert Reinert. The plot involves an artifical man created in the lab, à la Frankenstein’s monster. He’s a superman, in both strength and ambitions. The only surviving episode of the serial is Die Rache des Homunculus (“The Revenge of Homunculus,” 1916). (But see the codicil.) In this installment, posing as Professor Ortmann, Homunculus decides to drive humanity to destroy itself. He assumes a disguise to rouse the rabble, even inducing them to turn against himself in his Ortmann guise.

As in Expressionist drama, this overachiever is pitted against a crowd that, in the end, pursues him maniacally.

Director Otto Rippert gives us splendid mass effects in a quarry and along a beach, but there are also deep tableau images and sustained chiaroscuro, particularly in a showing the heroine Margot shrinking from Homunculus as he locks his rival in a dungeon.

Fans of Metropolis will notice that Rippert anticipates Lang’s unison choreography of crowds, as well suggesting that mob frenzy can create a sort of ecstasy in the woman who’s swept along.

In her book The Haunted Screen Lotte Eisner traces the films’ mass spectacle back to the stage work of Max Reinhardt and other theatre directors of the era. On the basis of this episode alone, Homunculus ranks with Algol and May’s Herrin der Welt as an example of big-scale fantasy in German silent cinema. Who needs Ant-Man when we have Homunculus?

Next time: Burt and Jean-Luc, together again for almost the first time.

Thanks to Nicola Mazzanti, Francis Malfliet, Bruno Mestdagh, and Vico de Vocht for their assistance during my visit to the Cinematek.

Kristin analyzes stylistic conventions of German cinema of this period in her Herr Lubitsch Goes to Hollywood (available for download here). She’s written on Caligari here and here.

A so-so copy of Sappho is on YouTube.

On Homunculus, Leonardo Querisima offers a wide-ranging discussion in “Homunculus: A Project for a Modern Cinema,” in A Second Life: German Cinema’s First Decades, ed. Thomas Elsaesser and Michael Weidel, pp. 160-167. Substantial excerpts can be found here.

Munich archivist Stefan Drössler has recovered a mass of Homunculus footage and has assembled a version of the serial, which premiered last year in Bonn. Nitrateville has the story.

The Brussels Cinematek will release its Hou restorations on DVD early next year: Cute Girl, The Boys from Fengkui, and Green, Green Grass of Home. As a reminder, my video lecture on Hou is here.

The still below, taken as the prints were readied for the Summer Film College, points ahead to our next entry–number 701, as it turns out.

Il Cinema Ritrovato: Back to the future (of movies)

DB here:

The Teatro Comunale of Bologna is an eighteenth-century opera house that was launched by a premier of a work by Glück. It has hosted massive productions of Wagner, Rossini, and Verdi, and was a favorite venue of Toscanini’s. Elegant and imposing, with box seats and an orchestra pit, it makes you feel like you’re in Senso or Liebelei.

In some years Cinema Ritrovato has secured the Teatro for gala screenings of silent films, complete with orchestral accompaniment. One show of Lady Windermere’s Fan was a delight. In another year, the hammering Meisel score for The Battleship Potemkin nearly blasted me out of my seat. I was sitting up front.

This year it was Rapsodia Satanica (1917) that got the Comunale treatment. This apparition has lost none of its exuberant morbidity, and we got to watch it with the original Pietro Mascagni score. Timothy Brock found that the original orchestra parts were lacking hundreds of tempo changes, because Mascagni himself conducted during screenings and never inserted them. Through careful testing against the film, Brock managed to create a score that brought a packed Communale audience to its feet cheering. One more testament to the power of 1910s cinema.

1915 and all that

Assunta Spina (1915).

I tried, really tried, to see other wonders from all the places and periods on display at this year’s overstuffed Ritrovato. But because of my love of ‘teens films, both American and not, I kept coming back to as many items from that era as I could squeeze in.

There was, centrally, the series Cento Anni Fa (A Hundred Years Ago), curated by Marianne Lewinsky and Giovanni Lasi. 1915 was, of course, a decisive year in American cinema, to be forever identified with Griffith’s monumental The Birth of a Nation. Standard histories would have it that this was the stroke that revealed the artistic power of cinematic storytelling. Griffith’s colossus was naturally very influential, but it wasn’t an isolated accomplishment. Earlier films, such as Weber/Smalley’s Suspense (1913), and other 1915 films–De Mille’s The Cheat and Walsh’s Regeneration in particular–are more typical stylistically of what Hollywood silent cinema would turn out to be.

Add to this list another 1915 item. If film history were an exercise in fairness, Reginald Barker would be recognized as one of the directors who set American filmmaking on its “classical” road. Working under Thomas Ince’s supervision, Barker showed a flair for economical framing, frequent changes of setup, and bold cutting within scenes. His Typhoon (1914) is at many moments more nuanced in its analytical editing than Birth.

1915 was a fine year for Barker. He turned out the long-praised The Italian (shown in the series), as well as the dynamic Civil War drama The Coward, along with superb William S. Hart westerns like On the Night Stage.

So The Despoiler, another Barker from 1915, did not disappoint. It survives only in a cut-down French print, but it still packs a sensational punch.

The original, according to a contemporary review, involves a border war in which troops invade a small town. The leader of the dark-skinned horde fastens on one beautiful woman, who has taken refuge in a nunnery. She is about to sacrifice herself to save the others, when the colonel learns that she is his own daughter. She is saved, and at the very end the whole thing is shown to have been a dream. The French version Châtiment (“Punishment”), painstakingly restored by the Cinémathèque Française in 2010, was modified to fit propaganda demands of the war period. Here the daughter really gets raped, and she shoots her attacker. The colonel turns his troops loose on the nunnery, but halts them in time when he realizes who the victim is. No dream stuff here.

Barker’s style is fluid, and he builds great suspense when the daughter, barely recovered, prepares to shoot her ravisher with his own pistol. The scene has judicious depth staging, as when the soldier lies drunkenly on the cot but he’s blocked by the woman’s gradual decision to use the weapon. At the proper moment she swivels aside to reveal his head lolling in the background.

The match-on-action when the woman turns and pulls up her sleeve is more perfect than many such cuts in Griffith’s films. She then strides to the background to give us a full view of her target.

A brief shot of the daughter’s attacker is replaced by a 3/4 view of her drawing a bead on him, with Jesus taking her side.

Other countries’ 1915 output wasn’t ignored. We got Denmark’s Revolutionary Wedding, proof that August Blom had not given up the somewhat rigid version of the tableau style he had used in Atlantis (1913). More florid were the Italian offerings. Assunta Spina (lovingly restored by Bologna’s own Cineteca and now available in a DVD), is a classic of the nation’s silent cinema. It was treated to a carbon-arc projection one evening in the courtyard. The less-known but no less flamboyant Il Fuoco (“The Fire”) is a melodrama about a rich woman who destroys a naive, passionate painter.

The two films are famous for showcasing the divas Francesa Bertini and Pina Menicelli respectively. But they’re just as important as powerful illustrations of the variety of 1915 pictorial styles. Assunta Spina is a triumph of tableau staging. By contrast, the opening of Il Fuoco, detailing the first encounter of the owl-woman and the burly artist, is as rigorous a piece of editing that I’ve seen anywhere at the period. Assunta Spina fills the frame with layers of depth (above and first still below). Il Fuoco makes play with bold optical POV, especially when the painter is transfixed by his languid model.

To which one can only say: Zowie.

Bluebirds of happiness

Back in the 1980s I wanted to see some films from Universal’s Bluebird Photoplay series. It had been accepted wisdom that the Bluebirds were among the first American films seen in Japan, and accordingly they had influenced Japanese filmmakers. My searchings led me merely to fragments at the Library of Congress. But today, according the Ritrovato’s indispensable catalog, about thirty complete titles have been found in archives. The most famous, Lois Weber’s Shoes (1916), screened at Bologna in 2011.

The Bluebird franchise was identified with feel-good stories, often rom-coms centered on women and derived from fiction by women. Mariann Lewinsky points out that the unit was a training ground for Rudolph Valentino, Mae Murray, Tod Browning, Rex Ingram, and several other notables. A striking number of Bluebirds were directed by women, in particular Elsie Jane Wilson. About 170 films were produced under the logo, and Hiroshi Komatsu’s catalogue entries confirm that they had a powerful impact on Japanese fans and filmmakers.

Four Bluebird titles, all discovered at the French CNC archive, confirmed the ingratiating charm attributed to the brand. Little Eve Edgarton (1916) centers on a botanist daughter who’s whip-smart in science. Her father tries to marry her off to an older colleague, but she resists. The Love Swindle (1918) is more elaborately plotted. The main couple meet cute during a comic home invasion, in which Diana Rosson proves better at defeating hungry tramps than Dick Webster, who gets conked out trying to protect her. After a date, Dick decides Diana’s too modern and highbrow for him. Diana, undaunted, takes a room in a pension and masquerades as her own impoverished sister, Miranda. Dick naturally falls for Miranda.

Here again, the polish and inventiveness of ‘teens Hollywood comes through. Stylistically, we find nearly everything characteristic of classical presentation: scene analysis, angled shot/reverse shot (though no over-the-shoulders), surprising camera movements, expressive low and high framings. In narrative terms, our heroines conceive goals and pursue them tenaciously. Rosamond in The Dream Lady (1918) even makes a list of her four aims in life. Getting a house is surprisingly easy; marrying a real gentleman takes a little longer.

There are as well ambitious storytelling gambits. At one point in The Dream Lady, an orphan girl imagines that she has a mother and lives in nice surroundings. Director Elsie Jane Wilson cuts freely between the girl’s fantasy and Rosamond looking in on her. One startling cut matches on the girl’s gesture of flouncing her ribbon, taking us between dream and reality. (It’s actually a cheat–wrong arm–but perhaps the change of angle covers the disparity. Sort of like here.)

Then there’s the plot of The Little White Savage (1919). It starts with a circus boss and his sidekick telling customers how they acquired a star attraction, a wild girl purportedly from an island on no maps. The flashback yarn is absurd from the get-go, and it gets wilder as it proceeds, as the heroic sidekick somehow goes from he-man adventurer to pious parson. In a surprisingly salacious passage, Minnie, escaped from the sideshow, hops into the clergyman’s bed. They squeeze and nuzzle unashamedly as nosy townsfolks watch in horror.

It’s all a tall tale, of course, confirmed when the frame story reveals Minnie as simply a cute modern girl. The Confession (Fox, 1918), hinged on a more serious lying flashback and may have supplied the premise for The Little White Savage. Again we find the 1910s as an era of fertile innovation. “Its breezy bold difference makes it worthwhile,” wrote a critic of this Bluebird release. “What Paul Powell and scenarist Waldemar Young have done here is the sort of adventure that makes screen progress.”

A bigger-budget Universal release served as pendant to the Bluebirds. Lois Weber’s Dumb Girl of Portici (1916) was a collaboration with dancer Anna Pavlova. A truncated version had long lain at the British Film Institute, but Geo Willeman and Valerie Cervantes found a 16mm print at the New York Public Library. That enabled them to create a very pretty, nearly-complete version, which now concludes with a lengthy Pavlova dance. The super-production, now running nearly two hours, was based on Daniel Aubert’s 1828 opera and offers some ambitious spectacle.

As a prestige entry with crowd scenes, lavish sets, and one of the stage’s top stars, it’s about as far from the humble Bluebirds as you can get. It’s notably stiffer and less dynamic too; what is it about costume pictures that makes for an academic approach? Still, The Dumb Girl of Portici and the Bluebirds exemplify the ways in which filmmakers of the period laid down many paths of exploration for the future.

The devil you know

I first saw Rapsodia Satanica some years back during a Brussels visit. I liked it fine, but seeing it with tinting and hand-coloring, on the big Comunale screen, with a live orchestra convinced me that it really needs its score. The plot is thin, but with the music throbbing along with its heroine’s seductive pirouettes and mournful drifting, the whole thing makes powerful cinema. It was in fact billed as a “Cinematic-Musical Poem,” suggesting that here lyricism will dominate.

With the score tightly matching fluent acting, I’m reminded of a point Kristin made some years ago. She wrote about the ‘teens as an era in which many directors opened up new domains of cinematic expressivity. Having developed effective methods of storytelling, they began looking for techniques that would deepen the emotional impact of the action. Rapsodia satanica is practically a case study for this tendency.

Countess Alba sells her soul to regain youth. One of her suitors kills himself, the other flees. She winds up alone on her estate. This simple story is elaborated through many techniques of mise-en-scène. There are the dancelike performances; Satan practically coils himself around his victim’s calf. There are the costume changes, as Alba moves from her heavy dowager dress to diaphanous veils in her voluptuous phase, and then, in her solitude, a simple shift. When she thinks the surviving lover is about to return, she wraps herself in the veils she wore before. Even the hand-coloring adds impact; as in the pair of stills below, often Alba’s dress is the only colored mass in the shot.

The hallucinatory images gain both precision and passion from the soaring score. Our heroine sells her soul to Satan in exchange for a return to youth. The moment when she sheds her elderly skin and emerges, like the butterfly we’ll see later, as a ravishing beauty is accompanied by a motif that exfoliates just as lushly. An offscreen pistol shot is prepared by a driving crescendo, but the orchestral outburst is still startling. The countess registers the realization that one lover has killed himself, and diva Lyda Borelli synchronizes her attitudes with that climax: body clenched at first, then sliding toward a more doleful pose.

At forty-two minutes, Rapsodia Satanica is practically, as Gian Luca Farinelli remarked in his introduction, an experimental film. Its unsettling use of multiple mirrors, trapping the heroine in fractured reflections, sets up Charles Foster Kane’s zombie-like passage through his palace. The film’s second part, in which the heroine drifts through landscapes and enormous rooms, looks forward to the American “trance films” of the 1940s and the Cinema of Walkies, from Neorealism and Antonioni to Tarkovsky. In all, the film lets us recognize the persistence of some trends across film history, and appreciate that the 1910s are not as far away as they might seem.

Thanks to Guy Borlée and Cecilia Cenciarelli for help with this entry.

The immense catalogue of this year’s Cinema Ritrovato, essential for background to the screenings, can be purchased here. There’s a pdf for reading or downloading here. These folks think of everything.

For contemporary accounts of The Despoiler, see the Lantern pages here and here. The Cinémathèque Française webpage provides a detailed explanation of the restoration. The Photoplay review of The Little White Savage is here.

You can read more about Bluebirds at Adrian Curry’s “Poster of the Week” site on mubi, from which I took the Bluebird logo above. Be sure to scroll down to enjoy the gorgeous designs on display.

For more on why the ‘teens are crucial, see the Vimeo talk, “How Motion Pictures Became the Movies.” On continuity editing, you might start here; on tableau staging, here. Kristin’s article is “The International Exploration of Cinematic Expressivity,” in Karel Dibbets and Bert Hogenkamp, eds., Film and the First World War (1995).

Rapsodia Satanica.

Il Cinema Ritrovato: The advantages of leaving home

Kristin here-

David and I are in Bologna for Il Cinema Ritrovato. Once again there is an overwhelming choice of films on offer, demanding a patient acceptance of the fact that one cannot possibly see anything close to everything one wishes. Careful planning can only do so much.

If there is anything I have learned from the films in the first half of the festival, it is that one should not leave home. In the earliest surviving Mizoguchi Kenji film, The Song of Home (1925), a talented but impoverished young man accepts the idea that staying in his village is best for both himself and Japan.

Nearly thirty years later, Girls in the Orchard (dir. Yamamoto Kajiro, 1953), the heroine must choose between going to Okinawa with her fiancé or marrying a man who can help her maintain her family’s traditional pear farm. Naturally, she makes the right choice.

The heroine of Ousmane Sembène’s first feature, the pioneering Senegalese film La noire de … (aka Black Girl, 1966) leaves her home country for France and the better life she dreams of, only to find herself virtually imprisoned working as a maid in Antibes.

The lesson is clear, and yet those of us who have ventured from around the world to Bologna are all the better for it.

Color blooms in Bologna

Color films have always featured on the program at Bologna, but this year various processes are on display in more threads than usual. While the past three festivals have offered a lengthy retrospective of early Japanese found films, this year’s it’s early Japanese color films. There are vintage Technicolor prints in one series, restored color from the silent era in several threads, and eye-poppers like Cover Girl among the restorations being shown off by various archives and labs.

The first screening on the opening afternoon of June 27 was The Thief of Bagdad–not the Fairbanks silent but the 1940 British version co-directed by Ludwig Berger, Michael Powell, and Tim Whelan. I must have been one of the few in the vast Arlecchino theatre who had never seen it, even in a faded 16mm print. Some were there to recapture the fond memories of their youth.

As a “vintage” print, it had an odd history. This was not a vintage re-release print, as some of us expected. It stemmed from the 1990s chemical restoration which was subsequently digitally scanned. The images looked like the Technicolor films of my youth (not quite the 1940s, but at least the 1950s). It was a relatively early film using the three-strip Tech process, which had really only reached its ideal form in Hollywood as recently as 1939, with The Wizard of Oz and Gone with the Wind.

This print had the eccentricities of the three-strip process. Some shots had poor registration, with red and green rims around the characters, while others were in perfect alignment. The matte lines for the numerous fantastical effects (flying horse, giant jinn, flying carpet) were very obvious, and the color changed suddenly for every dissolve. The print was probably not a bad indication of what audiences would have seen at the time.

The design certainly took advantage of the color process, with numerous false-perspective sets and costumes carefully arranged to show off the range of bright hues that Technicolor could achieve (above).

As for the film itself, it is extremely charming without being one of the masterpieces of the era. It suffers from having a bland pair of actors as Ahmad and the princess who loves him, and Sabu is perhaps a trifle too irrepressible as the titular thief, Abu. Miles Malleson, the comic character actor who co-scripted the film, steals the show as a Sultan so obsessed with elaborate mechanical toys that he trades his daughter to the villainous Jaffar (Conrad Veidt, acting rings around much of the cast) for the flying horse. It was an epic in its day and perhaps helped give rise to the many Technicolor fantasies of the 1950s.

A different sort of range was shown off in a program of silent films restored by the EYE Filmmuseum of the Netherlands. These included hand coloring, as in a 1915 short documentary preserved under its English title, Dutch Types, primarily consisting of shots of villages and schoolchildren.

A 1913 Italian film La falsa strada (dir. Roberto Danesi) was a tinted print. It starts off with a familiar situation of an opera singer giving up the stage to live a quiet life on her rich husband’s country estate. One might expect a young lover to rescue her from her boredom, but instead her very lively show-business friends from the city visit and cause the husband to be jealous of the singer’s apparent preference for their company over his. Unfortunately the final reel was missing.

Even more incomplete was Una notte a Calcutta (dir. Mario Caserini, 1918, right). Only a couple of scenes totaling eleven minutes survive, but they show off the talents of diva Lyda Borelli and suggest that the settings and costumes for this otherwise lost film were impressive.

The emphasis on color promises to continue next year, as with the hints dropped concerning further early Japanese color films to come on a second program.

The auteur of the year

Following a long-established tradition, the festival includes a retrospective of a Hollywood director, Leo McCarey. Having seen quite a few of the films on offer, I haven’t followed this thread faithfully. I fondly remembered Ruggles of Red Gap (1935) from a single 16mm viewing many years ago, though, and decided to watch it. I was glad I did. For a start, it was a mint 35mm print and a joy to watch. Moreover, I had remembered Charles Laughton’s performance as hopelessly mannered and eccentric. This time I caught many of the subtle gestures and glances that he used to convey the thoughts of a character who, at least in the early scenes, speaks little and then only very formally. The supporting cast is ideal for the witty script that condenses the overly long original novel.

McCarey got his start by directing two-reelers with some of the best second-tier slapstick comics of the 1920s, including Charlie Chase, Max Davidson, and Mabel Normand. One program of three showed off each in turn. The Uneasy Three (1925) casts Chase as an aspiring burglar invading a society party with two partners-in-crime sneaking in by impersonating a trio of classical musicians. Don’t Tell Everything (1927) has Max Davidson marrying a wealthy widow, only to have his obnoxious freckled son (Spec O’Donnell, as always) worm his way into the household by disguising himself as a surprisingly convincing maid. Finally, Should Men Walk Home? (1927) teams Creighton Hale and Mabel Normand in another stealing-a-brooch-from-a-society-party plot. Normand gives a late, great performance. (Imdb lists this as her penultimate role.)

The World Cinema Project restores another three

I always try to see the latest films restored by the World Cinema Project, which aims to save important movies made in countries that do not have the archives or resources to protect them. This year the films were La noire de …, Sembène’s first feature, Ahmed El Maanouni’s Moroccan film, Alyam Alyam (aka Oh the Days, 1978), and Lino Broca’s Insiang (the Philippines, 1976).

La noire de … deals with the post-colonialist effects of French rule in Senegal, with the heroine Diouana (below) eager to visit the France of her dreams. Once there, she is never allowed to leave the apartment of the French couple who has employed her; they told her she was to care for their children, but she is relegated to household tasks.

Our friend Peter Rist recalled seeing this film with a color sequence, but this was not included in the restoration. The informative panel introduction to the film, led by Cecilia Cenciarelli of Project, revealed that a sequence showing Diouana’s arrival in Marseilles was shot in color. The idea was to show the heroine’s hopeful view of her new country, contrasting with the black and white of the rest of her film as that hope dissipates. Cenciarelli said that there is no clear evidence that Sembène intended this color scene to be part of the final film. If it survives, it would make a valuable supplement to a future home-video release.

Going from Ruggles of Red Gap to Insiang was an experience in contrasts of the sort one often has here. Insiang is the film’s heroine, a laundress living in a Manila slum. The film was shot in a poverty-stricken area and incorporates many candid shots of children playing in mud and puddles. Much of the action involves shiftless young men who drink and gossip as the women around them do most of the work (above). Against this reality-based milieu, Brocka sets an extremely melodramatic story of Insiang and her mother competing for the affections of the same wastrel. One suspects that Brocka was trying to make his grim film palatable to a broader audience, but the film was a financial failure.

Maanouni took a very different approach for Alyam Alyam. There is a minimal plot about a young peasant earning money to travel to France or the Netherlands for work. This character and his mother and grandfather,  who strenuously object to be his perceived desertion of them, appear at intervals through the film. Most of the scenes, however, are poetic views of village life, evoking both the back-breaking labor of the countryside and the beauty of its traditions.

who strenuously object to be his perceived desertion of them, appear at intervals through the film. Most of the scenes, however, are poetic views of village life, evoking both the back-breaking labor of the countryside and the beauty of its traditions.

In introducing the film, Maanouni said that he wanted to question why Morocco cannot provide the opportunity and incentive to keep young people from leaving. By emphasizing a lyrical depiction of the countryside and the impossibility of earning anything but a subsistence wage, he makes vivid the sad waste of the nation’s potential–a problem that has persisted for decades since the film was made.

The unending march of restoration

The one theme that persists from festival to festival is the thread of re-discovered and restored films. The screenings and, increasingly, the panels and lectures on archival methods, reminds us of how expensive and difficult this process is and how much work goes on each year.

The main film I have seen so far among the restorations is Julien Duvivier’s little-known 1939 film, La fin du jour. (A restoration of his more famous Le belle equipe, 1936, was also shown this year.) It’s the story of a group of actors living in a chateau supported by private charities and dedicated to taking care of aging thespians. They play out their individual dramas against the backdrop of a threatened bankruptcy of the home and a dispersal of its inhabitants to various government hospitals across the country.

There are three primary stories. Cabrissade (Michel Simon) maintains his claim to dramatic fame despite having been only an understudy, and that to a star who never missed a performance. Now entering the home and disturbing its equilibrium is Saint-Clair (Louis Jouvet), an unrepentant seducer and liar. Marny (the less famous but excellent Victor Francen) is a successful actor depressed over his wife’s death, perhaps by suicide, after she ran away with Saint-Clair.

There are numerous small plotlines played out by skilled character actors of the era. The ensemble is interwoven in an impressive example of the “Cinema of Quality,” here practiced by scriptwriter Charles Spaak in collaboration with Duvivier. The tale briefly becomes maudlin toward the end but overall is a touching and often funny depiction of old age among a group particularly reluctant to face that time of life.

In the second half of Il Cinema Ritrovato, I’m concentrating on a small retrospective of Iranian cinema of the 1960s and 1970s, as well as a long-awaited restoration of Satyajit Ray’s Apu Trilogy.

David’s book Figures Traced in Light discusses how The Song of Home displays Mizoguchi’s early mastery of Hollywood-style staging and cutting, before he went on to try considerably different techniques.

Thanks to Manfred Polak for a correction regarding La noire de … His blog entry on the film is here.

La noire de… (Ousmane Sembène, 1966).