Archive for the 'Silent film' Category

A legendary film returns from the realm of the lost

Kristin here-

Nearly two years ago, when Flicker Alley released its wonderful collection of French films made by the Russian-emigré production company Albatros in the 1920s, I wrote, “Now, if Flicker Alley will manage to release its long-rumored project, Albatros’s 1923 serial, La Maison du mystère, starring Mosjoukine, we will all be doubly grateful.” That release arrived yesterday.

For decades, La Maison du mystère remained one of the fabled lost films of the silent era. It was an enormous popular success upon its release in 1923, and critics praised it as well. Even Louis Delluc, who highmindedly promoted cinema as a realistic, restrained art, grudgingly said of it, “La Maison du mystère is a serial. They are a necessity. So be it. This one is intelligent, sober, frank, genuinely human.”

Watching the film today, “sober” seems an odd term. Despite its many arty moments, the film presents a conventionally melodramatic story, with Mosjoukine playing a struggling factory owner betrayed by a villainous “friend” who is secretly in love with his wife. He is falsely accused of murder, presumed dead after an escape from hard labor, and operates under various disguises. Blackmail, flashy escapes, a suicide pact, and flagrant coincidences all play roles. Yet in contrast to the fantastical ones of Louis Feuillade from the 1910s, the ones we are most familiar with today, Le Maison du mystère paid more attention to characterization and moved at a less breakneck pace. (Feuillade had moved into this sort of dialogue-centered melodrama himself in the 1920s, as in Les Deux Gamines, 1921, but these films are rarely watched today.)

With Alexandre Volkoff directing the script he and Mosjoukine adapted from a popular novel, filming began in the summer of 1921. At the beginning of 1922, Mosjoukine contracted typhoid fever and was out of commission for six months. Shooting was completed in the summer of 1922, and the film was released in ten weekly episodes starting in March of 1923. Ultimately, like so many silent films, it disappeared.

Severely abridged feature-length versions existed in some places. An 18-reel print discovered in the Iranian archive was destroyed in a fire before it could be sent to France for restoration. Luckily, the original negative turned up at the Cinémathèque française, having been donated in the collection of Alexandre Kamenka, the producer who took over Joseph Ermolieff’s company in 1922 and turned it into Films Albatros. After restoration, the film was shown at Il Cinema Ritrovato in 2002–well before we began our annual visits to that festival in Bologna. It was presented again at the Museum of Modern Art in 2003.

The Flicker Alley release runs 383 minutes and seems to be essentially complete, although the intertitles apparently are replacements. Unlike so many restorations derived from worn release prints, this one is visually gorgeous. It’s mostly in black and white, though it has appropriate tinting for fire and night scenes. Neil Brand provides an excellent piano score.

The old and the new

Like so many of the major French films of the 1920s, especially the Impressionist ones, La Maison du mystére combines a sentimental, old-fashioned story with unconventional stylistic devices: unusual pictorial motifs, beautiful cinematography and design, and imaginative staging. It is probably this visual interest that led to the film’s original acceptance by reviewers and to its enthusiastic reception by modern historians and silent-film buffs.

One visual motif that begins early on is silhouettes. The opening involves Mosjoukine’s character, Julien, still a bumptious, naive young man, courting Régine, the daughter of a wealthy couple who live near his chateau (the “maison” of the title). Despite his shyness, they manage to become engaged and walk joyfully through the woods together.

The entire wedding scene is then compressed into a series of shots done against bright white backgrounds render the actors and settings in near-black silhouettes (above). The result looks like a live-action version of a Lotte Reiniger cut-out animated film.

As I discussed in my entry on the Albatros DVDs, the settings in the studio’s films tended to be impressive as well. Here much of the interest is created by actual locales. David speculated that the whole film was conceived around the ruined fortress or castle where several scenes take place. That’s not likely, but the filmmakers used the ruins well. Rudeberg, a woodcutter whose penchant for amateur photography leads him to photograph the murder of which Julien is falsely accused and convicted, hides the prints in this castle. Rather than turning them over to the authorities, he is using them to blackmail the real murderer, the factory manager Corradin. Corradin twice follows him to the castle, leading to dramatic compositions of the two men in different parts of the frame. In the image at the top, Corradin slinks along the row of arched doorways at the bottom, while Rudeberg is visible moving through a higher archway at left center.

Alexander Lochakoff, the main designer for Ermolieff and then Albatros, was somewhat restricted by the story. He needed to provide realistic interiors for an antique-filled chateau rather than the modern apartments in which some of the other Albatros films take place. Still, he managed some characteristic designs, such as the prison corridor at the bottom of this entry, a location seen only in one brief shot.

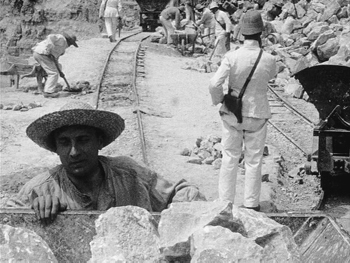

There are some brilliant moments of staging in depth. After Julien is sentenced to twenty years of hard labor, his new situation is introduced via a tracking shot with the camera atop a cartload of stone which he is pushing. Gradually the laborers breaking stone and the guards overseeing them are revealed (below left). In another shot in the ruins where Corradin is tailing Rudeberg, he is glimpsed in the background (below right).

In a scene late in the film, Julien plans to flee with Régine and their daughter Christiane. He is dressed as their chauffeur, but Corradin shows up and spots the car. Julien hides and watches him from behind a tree in the foreground.

We then see the two women approaching, framed through the back window of the car and watched by Corradin, in the foreground. He ducks down and pretends to fiddle with the car’s engine to prevent their realizing who he is as they draw near.

I could go on illustrating such stylistic flourishes, but I leave it to you to find them for yourself. There’s a very early example of a montage sequence to compress the passing of World War I into a series of titles, from 1914 to 1919, superimposed over stock footage of combat, and a marvelously choreographed high-angle scene in a forest as a troop of policemen pop out of nowhere to surround and arrest Julien.

All serials need stunts

Much of the film consists of conversations and confrontations among the characters, a trait which no doubt led critics to contrast the more action-oriented serials of recent years. Still, there are two sequences where derring-do takes over. After the police arrest Julien, he makes an escape via a rope down the tower and wall of his chateau, a feat accomplished in a single take tilting down to follow his progress.

Later, in an episode entitled “The Human Bridge,” Julien and four of his fellow prisoners escape from their guards while working on a railroad track. This lengthy sequence involves first the commandeering of a passing train and then a chase over an area of rocky crags. At once point the escapees find the rickety remains of a tall bridge above a river gorge and fling ropes across. The four other prisoners then lie end to end, clinging to the ropes, forming a bridge to allow Julien, who has been wounded during their flight, to cross over. One extreme long shot of the scene shows two of the men’s hats falling off, demonstrating as they drift down to the bottom that there is no trick photography involved. It is certainly as impressive as any of the stunts in Feuillade’s films.

Touches of Impressionism

La Maison du mystère certainly cannot be characterized as an Impressionist film. Yet the movement was beginning to expand in 1921, and there are some moments of subjectivity that draw upon its newly minted conventions. As his trial is drawing to an end, Julien closes his eyes, and the shot goes out of focus. We see a series of quickshots of his surroundings and his family as he seemingly recalls the events of the trial as a montage scene. Finally the same framing of Julien shows him coming into focus.

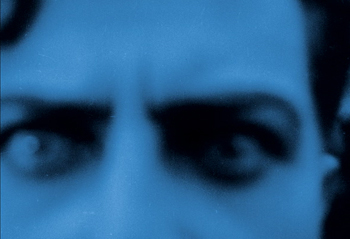

This is a fairly straightforward Impressionist device, but a more daring suggestion of a subjective state occurs much later. Julien’s daughter Christiane and Rudeberg’s son Pascal have fallen in love, and they vow that if they cannot marry each other, they will both commit suicide. When the villainous Corradin forces Christiane to agree to marry him, Pascal sets out to drown himself. His distraught state of mind is conveyed in a single shot as he walks toward the mill pond and hesitates. As he moves into the shot, he is framed in a standard medium close-up. As he hesitates, however, he moves unusually close to the camera and then backs partway out of the frame, as if afraid to continue. Finally he turns and stares into the camera, moving forward out of focus until his dark-shadowed eyes fill the frame. The implication is that he determines to go on with his plan.

(Fans of Evgeni Bauer will recognize Vladimir Strizhevski, the son in the director’s final film, The Revolutionary.)

Star turn

Apart from the imaginative staging, cinematography, and design, La Maison du mystère is full of fine performances. It provides a vehicle for a virtuoso performance by Mosjoukine. He is part Douglas Fairbanks, part Lon Chaney as he leaps energetically about in the early parts of the film and then dons various disguises during his long period as a fugitive. He briefly poses as a clown in a small circus and later returns to work incognito in his own factory as a wounded war veteran with a limp and eye-patch.

Mosjoukine’s fellow actors refuse to be overshadowed by the star, with Hélène Darly as Régine managing somehow to age from a young lady to a mature mother without any apparent change of makeup. Nicolas Koline, best known as Tritan Fleuri in Napoléon vu par Abel Gance, brings something of his usual comic persona to Rudeberg, while also conveying the character’s guilt over choosing to use his photographs for blackmail purposes rather than to reveal Julien’s innocence. Charles Vanel, who had been acting in films since 1910 and would become a major star in the sound era, conveys Corradin’s villainy perhaps too well, making one wonder why any of the other characters ever trusted him.

Flicker Alley, along with the Cinémathèque française, David Shepard, and Lobster Films, have filled in a major gap in film history, and we are indeed doubly grateful.

The quotation from Louis Delluc and information on the production of the film come from the essay, “The Art Film as Serial” by Lenny Borger with David Robinson, included as a booklet in the DVD set.

Impressionist films have been included in some of our “best films” of ninety years ago series. See 1921, 1922, 1923, and 1924.

Memory books, the movies, and aspiring vamps

Kristin here:

We are happy to have a guest entry from our long-time friend and colleague, Leslie Midkiff DeBauche, who recently retired from teaching film at the University of Wisconsin–Stevens Point. Back in the 1990s, when David and I were helping edit a series called “Wisconsin Studies in Film” (University of Wisconsin Press), Leslie contributed Reel Patriotism: The Movies and World War I. Now she is involved in a fascinating project on the same period, the 1910s. There is much focus these days on reception studies, which focuses on trying to gauge the reactions of audiences to movies. Reconstructing mental events is a difficult, near impossible task. Yet Leslie has found a way to glimpse the ways in which American girls and young ladies of decades ago consumed and thought about movies: by studying the scrapbooks they left behind. Here’s a sample of what she has discovered.

Fangirls of yesteryear

Kate Key received a scrapbook bound in red leather and entitled My Commencement as a gift from her oldest sister Ruth when she graduated from Lampasas High School, class of 1917.

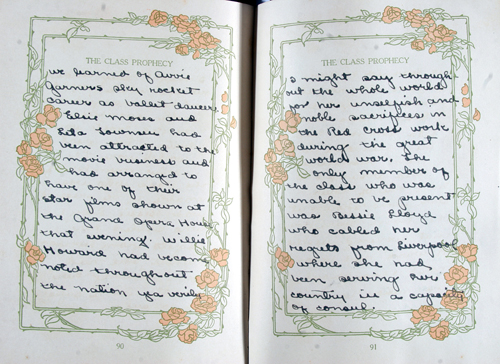

She was eighteen, born and raised in this central Texas farming and ranching community of about 2,100. As far as I can tell, there were no dedicated film theatres in town. Instead, movies alternated with concerts, vaudeville and plays on the bill at the Witcher Opera House. So, I was surprised to read in her class prophecy (a humorous forecast of what the students would be doing in a fictive future) that Elsie Moses and Leta Townsen would return for their class’s reunion in 1928 as movie stars and graciously show their films at the Grand Opera House.

This caused me to wonder whether girls who lived in other parts of the United States also made jokes out of the movies? Might scrapbooks offer film historians like me, interested in the ways that films fit into the lives of everyday people, a new sort of evidence of exhibition and reception in the 1910s and 1920s? When girls mentioned movies in their scrapbooks, or pasted in ticket stubs and theater programs, did they whisper “open sesame” to a quotidian film culture? Was that culture different from and more pervasive than that practiced by fangirls (and boys) who avidly consumed Photoplay and wrote mash notes to their favorite actors? I began to search out scrapbooks, specifically high school and college memory books.

To date, I have collected upwards of 45 scrapbooks. The scrapbooks I have found and studied are mainly the products of white, middle class and upper middle class girls. I have an example or two at either end of the economic spectrum. Despite my best efforts, I have had no luck so far finding the memory books made by African-American teenagers, though I suspect these exist. (I would welcome any suggestions.) New immigrants to the country may not have been aware of this “tradition.”

Before I survey what I have learned from American girls about themselves and about movie-going, let me tell you a bit about scrapbooks.

Multi-purpose compendiums

They have a long history in the United States. Samuel L. Clemons, Mark Twain himself, was an avid scrapbook-maker, and he patented a model featuring self-adhesive pages in 1873. By 1880, how-to books like E.W. Gurley’s Scrapbooks and How to Make Them, Containing Full Instructions for Making a Complete and Systematic Set of Useful Books, guided novices with instructions for what to include and even recipes for the glue to stick objects in place.

Arranged by topic and indexed for efficient access, early scrapbooks consolidated recipes for food or household concoctions. They served as encyclopedias and also provided entertainment. Poetry and fiction were appropriate inclusions harking back to the days of commonplace books. The scrapbook became a means for autobiography and a method of keeping family history. Gurley promoted making scrapbooks both an individual and a collective endeavor. Neighborhoods might organize a scrap-book club, and families could draw on the help of relatives to fill the gaps in their chronicles by bringing their books to reunions. For example, in 1906, Marion Renfrew, a school girl in Boston, invited her friend Eva Alberta Mooar to a party celebrating the “debut” of the “offspring of her labor and patience Memory Book.” Eva saved that letter in her own scrapbook, and the Arthur and Elizabeth Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America at Radcliffe preserved Mooar’s book in its archive.

Marketing scrapbooks to girls

Girls were a devoted audience for advice about creating scrapbooks, and the activity became, increasingly, a gendered one. By 1905, scrapbooks were a commodity, mass produced, sold at stationery shops, and complemented by auxiliary  businesses which supported them. Companies manufactured specialty paper corners, some with elaborate designs for sticking photographs to the scrapbook page. One genre of scrapbook was the memory book designed mostly for girls and young women and given to them as presents on special occasions like graduation from high school or college.

businesses which supported them. Companies manufactured specialty paper corners, some with elaborate designs for sticking photographs to the scrapbook page. One genre of scrapbook was the memory book designed mostly for girls and young women and given to them as presents on special occasions like graduation from high school or college.

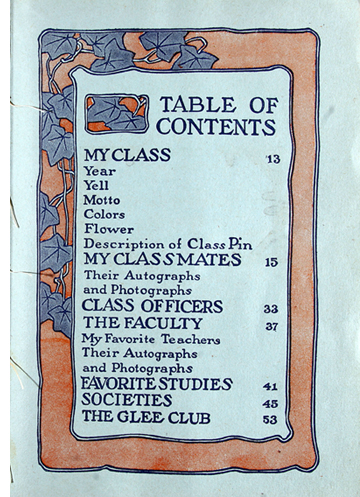

The Reilly & Britton Company offered eight different titles of school memory books for sale by 1917. The price of these gift books depended on their binding; “Fancy cloth, decorated with gold and two colors,” cost two dollars (about $40 today), but a leather cover with a velvety finish called ooze, added an extra dollar and twenty-five cents.

A blank page might have invited girls to fill in stuff of their choosing, but flowery Art Nouveau borders pushed the design toward a notion of conventional, appropriate girlhood. The filled spaces also conjured the metaphor that school was a garden, carefully tended, its flowers growing in tidy uniform beds. Memory books featured standard tables of contents that suggested what girls should preserve and how their mementos ought to be arranged. However helpfully intended, these headings also functioned to delimit what high school included and to prompt girls to tell a cheery, triumphal story in which “favorite” teachers, “best friends,” all sorts of parties, athletic endeavors, and the rituals of graduation would lead ineluctably to the happy reunion foretold by the class prophecy.

Still, what I have come to relish about girls who made scrapbooks is that they did not necessarily abide by the dictates of their books’ blueprints. They surely recognized the ideological requisites of girlhood structured onto memory book pages, but they may not have entirely subscribed to them. Often and idiosyncratically, girls changed and adapted their books.

Girls make scrapbooks to suit themselves

Elizabeth Walker travelled more than one hundred miles from Mineola, Texas to attend the College of Industrial Arts at Denton in 1918. She seemed to embrace the process of compiling My Memory Book. Hers was larger than most: 15” wide, 11” tall, and 2 ¼” thick. It appears that she received it when she matriculated and she filled in the pages as she progressed through her four years of teacher-training. After Elizabeth graduated in 1922, she became a teacher in El Paso. She continued to slide letters, documents including the Code of Ethics for Texas teachers and newspaper clippings, inside the back cover of her book during the 1930s. The most recent insertion was dated 15 July 1969. It was snipped from the school’s (now Texas  Women’s University) alumnae bulletin and brought her up-to-date on members of the class of ’22.

Women’s University) alumnae bulletin and brought her up-to-date on members of the class of ’22.

Still, at the beginning, the freshman Elizabeth had composed a bantering dialogue with her memory book’s table of contents. She treated it as a slightly irritating senior who was trying to tell her how to act. For instance, halfway down the list of things she was supposed to save were pressed flowers and leaves. “Don’t believe in ‘em,” retorted Betty.

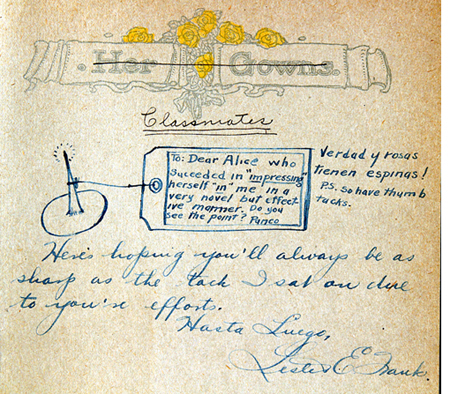

Alice Ebeling graduated in 1919 from South Bend High School in Indiana. She drew a line through the heading “Her Gowns,” replaced it with “Classmates,” and used the pages for autographs from her friends including Lester Frank (left). Apparently, he was on the receiving end of a prank she played in Spanish class.

Corinne Campau, Sophie B. Wright High School, New Orleans, class of 1919, crossed out “Favorite Studies” and pasted in a drawing of a rotund store clerk resembling the Campbell Soup kids drawn by Grace Drayton. Even better, the illustration covered up rude comments Corinne had written about a first-aid class and its annoying, irrelevant, teacher: “IT’S a joke. (‘Girls, I heard a case of a beautiful young woman—Oh, a sweet lovely young woman who fell on a brick + broke her hip.’)”

To me, there is irony, if not a nervous, dark humor in the decision of Fannie Klapman (Murray F. Tuley High School, Chicago, 1920) to glue a little cloth envelope embroidered with flowers on the page designated for “Card Parties.” The description she wrote underneath said, “New Year’s card from my brother at that time in France.” (He mustered out safely and went on to graduate from Crane Junior College in 1920.)

As well as manifesting a playful irreverence, the ways that girls altered memory books testified to a belief in their own agency. Scrapbooks were not private or secret like diaries. Girls took them to school where they solicited classmates’ autographs and good wishes; they showed them to friends who visited their homes. Although I expect many girls started to compile their memory books by following the order set out in tables of contents, when that rubric didn’t accommodate their stuff or their lives, they deliberately, messily, and with the knowledge that their actions would be seen, took matters into their own hands. They also began to make changes in the history of their lives at school almost as soon as they pasted their stuff in place. Memory books, like memory itself, were changeable, dynamic.

Movies and American girls

Since none of the books I have examined contain designated pages for films, how did American girls fit movie scraps into their memory books? When I consider my collection of artifacts, two broad patterns hold.

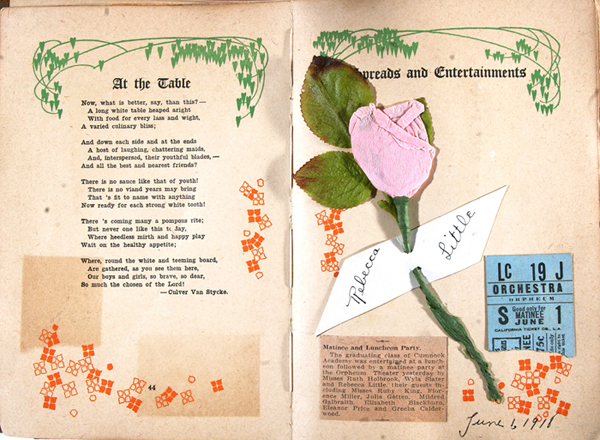

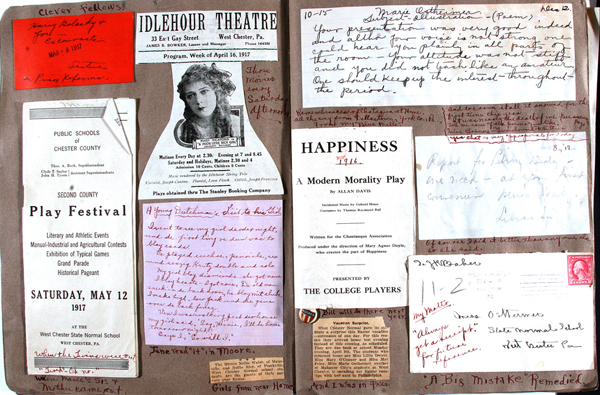

First, girls saved ephemera including ticket stubs, programs, occasionally newspaper advertisements that proved they actually saw films. (Above, Rebecca Little’s scrapbook from 1918.) I’ll call this category “Girls Go to the Movies.”

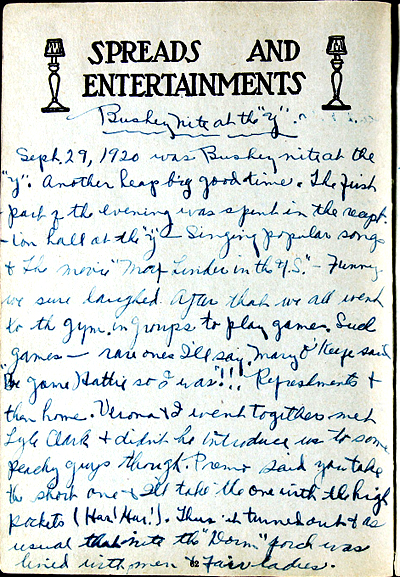

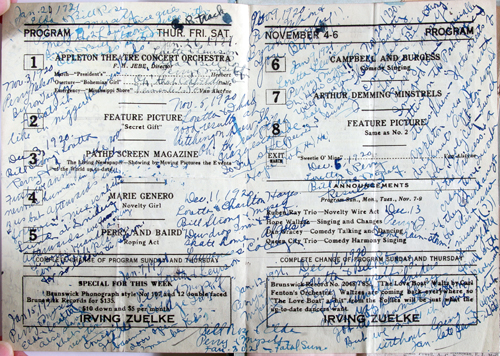

Second, and more intriguing, scrapbooks are crammed full of evidence that girls incorporated the movies–their actors, narrative conventions, and film titles—into a vernacular culture, national in its scope, spanning different religious affiliations. (Above, Hattie Stein’s School Friendship Book describes how she and her friends saw a Max Linder movie at the YMCA in Appleton, Wisconsin.) Let’s name this second motif, “Girls Make Fun with Movies.”

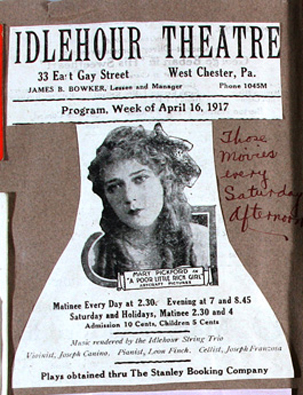

Girls go to the movies

Scrapbooks show that movie-going was one activity among many that mattered to girls in the 1910s and 1920s. No one expressed this better than did Marie Ostheimer, who graduated from West Chester Normal School in southeastern Pennsylvania in 1917. The only mention of film in the thirty-six pages of her Normal Life is the Liberty Bell-shaped newspaper ad for The Poor Little Rich Girl at the Idlehour Theatre which she clipped out (see bottom image). Nevertheless, she captioned it “Those movies every Saturday afternoon.” Her annotated two-page spread surrounds Little Mary with play programs, an excellent evaluation she received for a class presentation, news cuttings about her own and her friends’ trips home, and a receipt that was evidence of some sort of kerfuffle over a doctor’s bill. It is a snapshot of learning, leisure, and life experiences among which going to the picture show was part of the routine of weekend fun.

home, and a receipt that was evidence of some sort of kerfuffle over a doctor’s bill. It is a snapshot of learning, leisure, and life experiences among which going to the picture show was part of the routine of weekend fun.

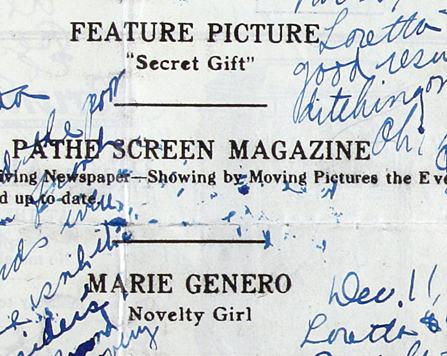

When girls did go to the movies with friends—which always seems to be the case—the screening was only one feature of the afternoon or evening’s or weekend’s entertainment. Case in point: Hattie Selma Stein, Busheys Business Academy, Appleton, WI, 1921-1922. She used a vaudeville program (above, the film Secret Gift is the 2nd turn and the chaser) to record the movies she attended during her year at school. Hattie jotted down the names of her companions, what the weather was like, how they “annoyed” the “nervous humans” seated in front of them, where they had snacks afterwards, and whether she and her boyfriend Perry won the race to the dorm’s porch swing at the end of the evening.

She didn’t always name the movie that served as the pretext for the date. Neglecting to note the film’s title wasn’t unusual in the scrapbooks I’ve examined. Instead, what girls saved was their experience of going to the movies.

For both Hester Swan from Independence, Missouri, class of 1919, and Janet Seidenman, who graduated from Western High School in Baltimore in 1926, food made an evening with friends and films tasty–an adjective which, at the time, meant not only yummy but also “in conformity with good taste.” Swan and twenty others attended a “line party,” featuring Marguerite Clark starring in Mrs. Wiggs of the Cabbage Patch. “After the show Grape Sherbert and Cake were served. We all had a lovely time and enjoyed the show and refreshments immensely.” In a page of her scrapbook, Seidenman drew an arrow from a caption “Richard Barthlemess [sic] in ‘The Fighting Blade.’ Peanut chews were served and everybody was happy,” to her admission ticket, which she also festooned with an inch-long strip of Kodak film negative.

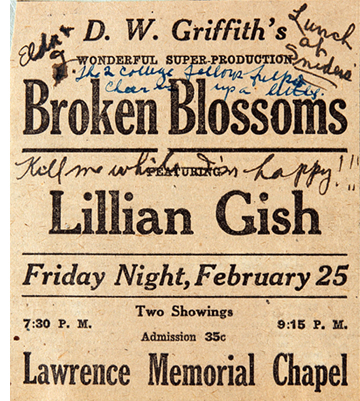

Every so often, though, going to the movies was a special occasion. Girls responded to promotional hype surrounding roadshows. When they saved movie programs, it was invariably from “big” films shown at a theaters which usually presented plays, for instance, the Majestic Theatre in Boston or the Savoy in San Francisco, or motion pictures made on the grand scale by D.W. Griffith. Hattie Stein captioned the ad for Broken Blossoms (right) showing at the Lawrence University Chapel, “Kill Me While I’m Happy.” She also noted that two “college fellows” were on hand to cheer her up and, of course, there was “lunch,” a colloquialism for snacks, at Sniders afterwards.

Girls make fun with movies

Girls did much so more than purchase tickets, sit in theaters, and watch movies before munching on peanut chews. Memory books show that girls around the United States incorporated the movies into their own playful culture. Certainly this is evidence that by the mid-teens, Americans were widely and deeply aware of information about movie stars, narrative conventions, movie-making itself, and the nuts and bolts of film exhibition. I think it’s also akin to the ways girls exercised control over their scrapbooks. When they used movies to make jokes, girls inflected the tone of the film industry’s advertising and narrative messages. They impressed their own proclivities onto increasingly standardized fare. The graduation convention of the class prophecy is a good place to start to see how girls adapted and used the movies for their own purposes.

So you want to be in pictures?

Class prophecies were an American school graduation tradition at least through the 1960s when I completed junior high. They were intended to be light-hearted, funny predictions about the future lives of the members of the class. Prophecies were guided by certain conventions of the form. They were often read publicly during graduation festivities, and it was not unusual to find pages designated for the class prophecy in memory books. Sometimes a prediction hinged on the student’s traits, interests, or romantic inclinations; it could hinge on word play about their name. It was important that the audience got the joke, or most of the jokes.

In nearly every class prophecy I encountered written from 1917 onward, at least one student was proclaimed to be destined for a job in the film industry. The most elaborate example lodged in Bertha Glennon’s memory book. Glennon graduated in 1918 from high school in Stevens Point, WI, the small city where I live. In fact, she was the author of her class’s prophecy and it was also her honor to read it aloud at Class Day a few days before the more formal graduation exercises. (She wore a dress of old-rose colored voile for the occasion.) The rhetorical device she created to frame her story was personal, timely, and more than a little macabre. The United States had entered World War I in April of Bertha’s junior year, and she had done her bit by helping to supervise in the Red Cross Room at school where students rolled bandages.

In the class prophecy, Glennon imagined herself as a nurse taking a break from her duties in a hospital on the western front. She sat on a hill and watched bombs explode in the distance. In each burst of smoke, Bertha saw a vision of the future. Boom! As the dusty haze resolved into an image, she identified classmates Ovid Meyer and Ada Kuhl in the midst of shooting a scene for a movie melodrama. Bertha Glennon described mise-en-scene, cinematography, and editing in sharp detail.

Glennon also wrote a diary that documented what she did every day during 1918, so, I know that in the five months leading up to her graduation she went to the movies fifteen times. Once she went on her birthday, another time because she didn’t have a date to the prom. She also recorded once when she went with her mother to visit a sick uncle. At his house she found a movie magazine which she read to pass the time while the grown-ups chatted. Bertha Glennon may have been a little better informed than most of my scrapbook girls, but she was not movie-mad.

Most often in class prophecies, girls were cast as movie stars. Dewene Flynt, Elizabeth Walker’s classmate at Mineola High School (1918) was sure to work for the American Motion Picture Co. and Adelheit M.W. Dettmann of Atlantic, Iowa (1918) was destined to be “Charles Chaplin’s leading lady.” After graduating in 1919 from Sophie B. Wright high school in New Orleans, Elizabeth Wakeman “will play piano at a moving picture show.”

“My Ambitions”

As you might guess, in real-life 1910s and 1920s America, relatively few girls made the transit from the high school auditorium to the movie studio, not even Rebecca Little who graduated from the Cumnock Academy in Los Angeles in 1918. (Martha Graham danced at the May Day celebration at her school that year.) Yet among the young women I have met in these books, one did actually become an actress: on the stage in the 1920s, on the radio in the 1930s, in the movies in the 1940s and 1950s, and on television in the 1950s and 1960s. She also wrote a novel, under the pseudonym Xanthippe, which was adapted into a film. Edith Meiser who graduated from the Liggett School in Detroit in 1917 is the exception that proves the rule. She was extraordinary.

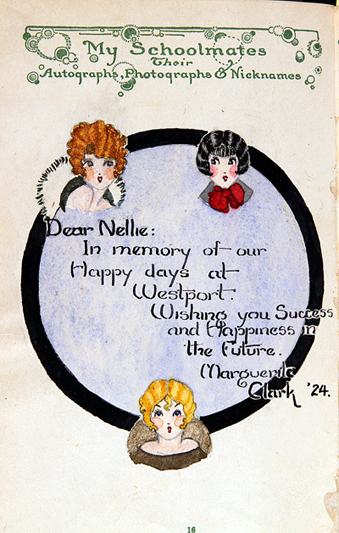

In fact, the hopes girls had for themselves and the wishes they made for others, were, in the main, conventional: success, happiness, good luck, and marriage. In a cartoon of a schoolgirl dreaming of her future, Sylvia Seidenman (Western High School, Baltimore, 1917) might have chosen the nurse with a hypodermic needle, a mother, a scholar, a ballet dancer, or a teacher with a ruler in her hand. Sylvia drew an arrow pointing at the typist, noting “This for me.” Edna Kallberg (Central High, Minneapolis, 1921) cut out and glued down a fat-cheeked toddler washing dishes (below left). “My Ambitions” was the heading which she affixed like a valance above the illustration. Nellie McKeever, from Westport High School, in Kansas City, Missouri (1924) had more talented friends and teachers than most girls did, but the same sentiments abide in their art and calligraphy (below right).

Girls didn’t make jokes with the movies when they autographed each other’s books; they wrote cautionary rhymes. “Long may you live; happy may you tarry, Court whom you please, but mind whom you marry.” (Mollie Winer warned Mary Louise Howell, Commercial High School, Atlanta, 1918.)

Some alluded to infamous moments in classes. Nearly always, they expressed the desire to be remembered. As Beatrice B. requested of Dolly Bennett (Houghton High School, Houghton, Michigan, 1921) “In the wood-box of your memory, save a little stick for me.”

The differences between the humorous fortunes cast for girls in class prophecies and the sincere but commonplace wishes one girl offered to another show that they fully understood a paradox at the heart of the popularity the film industry enjoyed with the American public. The stuff of the movies–its stars and its stories–must be both fanciful and familiar, provocative enough to pique the imagination, but also secure, a safe playground for parody. The industry provided fodder for jokes, whether it meant to or not.

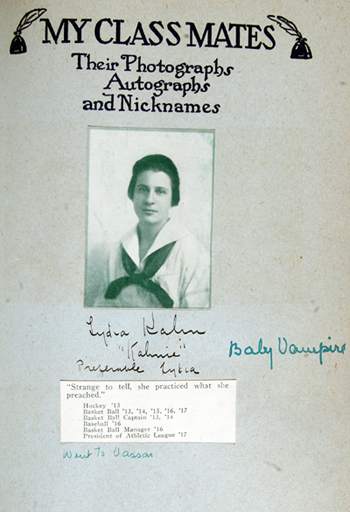

Starring Lydia Kahn, Baby Vampire

I will close this post with one last example of how girls employed the movies for their own amusement, to their own ends. The society these scrapbook girls lived in valued “correctness” in dress, speech, and behavior. Girls realized there were consequences—in life as well as in fiction–for not minding their Ps and Qs. As my grandmother Kate Key might have said, they knew “straight-up.” But, propriety did not stop girls from making fun of the rules governing them as young women, and movies gave them the ingredients for jokes.

Let me introduce Lydia Kahn, “Baby Vampire.” Vampire? The reference is to the character—a woman who destroyed men—made most famous by Theda Bara when she starred in the 1915 film, A Fool There Was. It was based on an 1897 Burne-Jones painting which inspired Kipling’s poem as well as both a play and a novel by Porter Emerson Browne. The movie coined the noun vamp and the verb to vamp. It also sparked jokes among young people all over the United States.

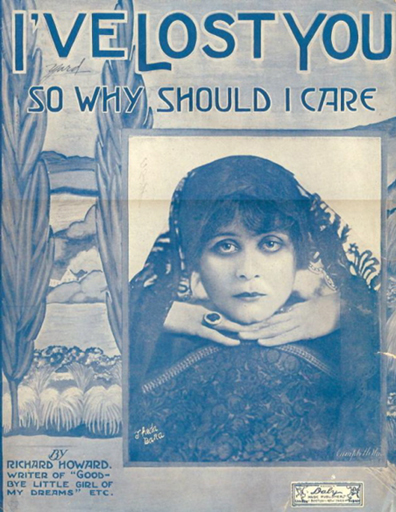

Kahn, the daughter of architect Albert Kahn, was memorialized as a vampire in Helen Schloss’s memory book. The girls were part of a remarkable class of upper and upper-middle class young women, including actress Edith Meiser, who graduated from the Liggett School in Detroit in 1917. The in-joke linking Lydia Kahn to Theda Bara was doubly made. First, there was the epithet Schloss scrawled next to her name. “Baby” in this context means vamp-in-training. Second, I found an allusion to Kahn as Bara in an issue of a little newspaper–more tongue-in-cheek than hard news–that the Liggett girls published their senior year. In a column headed “Heard at Grinnell’s” (a music store in downtown Detroit), one joke referenced a song, “’I’ve Lost Him so Why Should I Cry?’ which paraphrased the actual, “I’ve Lost You So Why Should I Care.” The titular question was attributed to “Kahnie,” which was Lydia’s nickname.

The sheet music portrayed Theda Bara—dressed, I think, for her role in Carmen (1915). Was Kahn a flirt? Had she broken up with some boy? Or, he with her? Was the question in the title ironic? Maybe Lydia Kahn was the opposite of a vamp but she bore a physical resemblance to Bara; perhaps Lydia Kahn did a great imitation of Theda Bara.

We’ll never know exactly why this joke worked so well that Helen Schloss transposed it from the Cap and Gown to her School Friendship Book, but my scrapbook collection can provide a context for interpretation. It turns out that Theda Bara’s vamp is the most common reference to the movies in memory books.

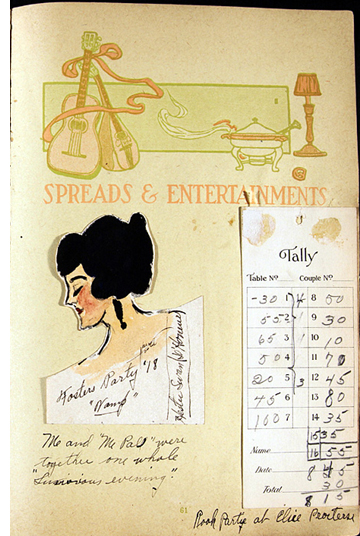

Lydia Kahn wasn’t alone, even in Schloss’s memory book, where Lucile Boynton was available to give lessons in vamping, “Efficiency guaranteed in three easy lessons. Prices reasonable.” Hester Swan’s place card at the Foster’s party (below left) read “Vamp” and pictured dangling earrings and a sophisticated demeanor. Although I expect this evening in Independence, Missouri was innocent, Swan wanted to remember that “Me and ‘My Pal’ were together one whole ‘Luxurious evening.’”

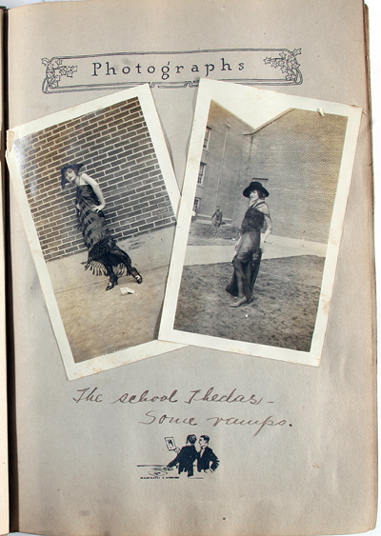

The prophecy for the Sophie B. Wright high school of 1919 foretold how Corinne Campau’s good friend Louisiana Clayton would depose Theda Bara as queen of the vamps after she graduated. This joke may have begun at the fashion show the seniors had hosted for the school’s junior class. Under snapshots of Lou dressed as the “Futurist,” and Aline Richter as “Hobble-Skirt Girl,” Corinne renamed them: “The school Thedas—Some Vamps” (above right). Everything about Lou screamed vamp: her outré costume, the slouchy, hand-on-hip pose, her dark-colored lips. There was another photo on the following page of Corinne’s memory book: here the school Theda is surrounded by classmates costumed as men–some kneeling, others leaning in–as Lou, blasé, looks off the right.

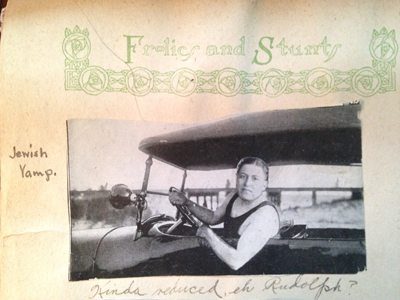

Even boys were liable to be called “Theda” or to be teased as vamps. Adele Franz seems to be recounting an embarrassing moment glimpsed in a boat house when she noted that Alfred J. Peterson, “alias Theda” would star in a production of “As the Lord Made Him.” And, Fannie Klapman printed “Jewish Vamp” beside a collage she had made by gluing the cut-out head of one of her male classmates onto the buff torso of a guy wearing a swim suit sitting at the wheel of an auto (below left ). To amplify the incongruity, underneath the picture she wrote, “Kinda reduced, eh Rudolph?” This might also be early evidence of Valentino’s star persona. No one in Fannie’s class was named Rudolph.

Klapman also commented upon other autographs friends wrote in her memory book. Next to a picture of Sara, who made an analogy between her own good wishes for the graduate and her love of Harold Lloyd, Fannie, somewhat cattily, I think, adds the annotation, “A would be vamp” (below right).

Hattie Stein and her girlfriends in Appleton, Wisconsin wore out the verb, vamping their way throughout their school year in 1920-1921.

What ought we to make of so many Thedas and so much vamping? I’m not entirely sure. If this is an example of an early 20th century meme, then Theda Bara and the vampire she portrayed function to throw conventional femininity and social mores into high relief. Bara was unambiguously evil in A Fool There Was. Girls (and boys) recognized this and camped her up even more. Girls could play dress-up and pretend to be bad—the better they were at the game, the clearer it was that they knew the rules of correctness. When I look at the references to Bara and vamping chronologically (and I surely wish I had more examples from 1915 and 1916), I detect a change. In the earliest mentions, there are connotations of physically sexuality (as with poor, perhaps naked, Alfred Peterson) and an imperious woman (hear the disdainful tone of “I Lost Him So Why Should I Cry” and imagine the smug look on Lou Clayton’s face as she ignores her admirers). By the early 1920s though, it seems to me that all menace has drained from verb and it simply means to flirt.

While there is more to tell about American girls, their memory books, and the movies, I must stop here. For readers who have watched and thought about American silent film or have studied its history, I hope that my research has added to your store. If you are interested in women’s history, I trust the scraps which illustrate this piece have reinforced what you know and have piqued your curiosity. I have grown inordinately fond of many of these girls and fascinated by their doings. My search for memory books continues; they are a rich resource for historians. They are exuberant, charming, funny, sometimes poignant and sad. They bear witness to how girls lived their everyday lives, what possibilities they were able to imagine for themselves, and the ways that movies fit into both these spheres.

I would like to thank David and Kristin for inviting me to share my work with you. It is a huge honor. I would also like to thank Doug Moore for shooting most of my photographs, and Sally Key DeBauche for casting her professional archivist’s eye on my scrapbooks and helping me to think about them as a collection.

The ten best films of … 1924

Die Nibelungen: Siegfried

Kristin here:

For a seventh year running, we skip ranking the current year’s films and instead hark back 90 years.

We started out with a list that was essentially an appendix to an entry, but soon we were dedicating whole entries just to the list. Our entries for past years are here: 1917, 1918, 1919, 1920, 1921, 1922, and 1923.

These lists are our way of calling attention to important silent films that some readers may have overlooked. In one case here we point out a largely forgotten film that deserves to be better known, in the hope that an archive will take the hint. With the proliferation of silent-film festivals, of DVD and Blu-ray releases with restored prints and supplemental material, and of TCM’s eclectic screenings of foreign and silent titles, there seems to be considerably more interest in these early classics. Herewith our choices for 1924.

For the last few years I’ve struggled to fill out the full list of ten films with truly deserving items. But as I’ve been predicting, the 1924 choices fell easily into place. As usual, some of these are obvious picks, already famous to most readers. Others are less obvious, and a few are unknown except to specialists. Some, though very important historically and artistically, are not currently available on DVD, which is a real shame.

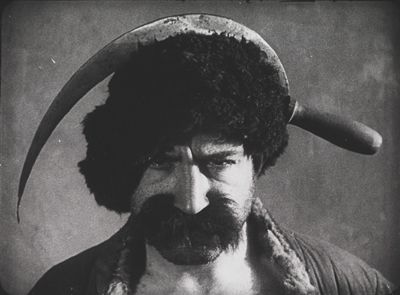

At last, the USSR

Films in the Soviet Montage style make up one of the most important cinema movements of all times. The key filmmakers of the movement, Eisenstein, Pukovkin, Dovzhenko, Kuleshov, Kozintzev and Trauberg, and others began their work later than the German Expressionist and French Impressionist directors. But at last one joins our list, with Lev Kuleshov’s The Extraordinary Adventures of Mr. West in the Land of the Bolsheviks.

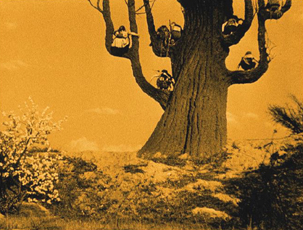

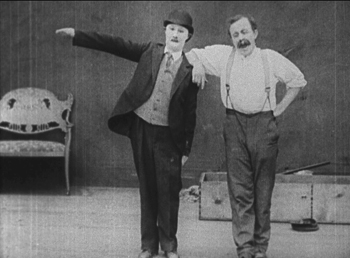

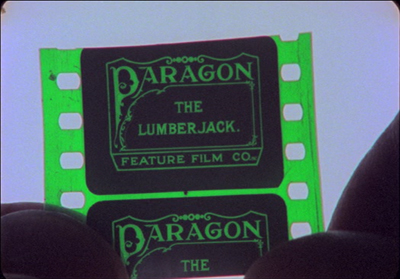

Although Kuleshov’s work has become more widely available, his most familiar work is still By the Law (1926), a grim tale of two members of a gold-prospecting team agonizing over how to bring to justice a colleague who has committed a terrible crime. Mr. West couldn’t be more different. This hilarious and grotesque comedy satirizes American perceptions of the new Soviet Union, as Mr. West, president of the YMCA, comes to for a visit, his faithful cowboy friend Jeddie in tow. They’re terrified of the barbaric land they expect to encounter, and a gang of thieves dupe Mr. West by dressing up in outfits that caricature West’s images of Bolsheviks (above).

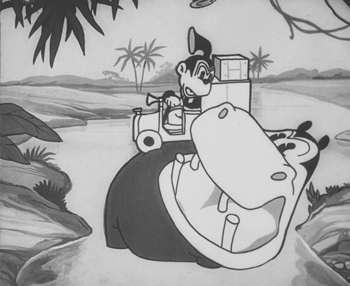

In making the film, Kuleshov and his team drew upon the experiments they had been doing in his classes he ran of the early 1920s. Film stock was scarce and all he and his students could do was practice staging scenes and make short editing experiments. They explored the possibilities of “biomechanical acting,” a style based more on gymnastic control and energy than on psychological subtleties of facial expression.

Once the group did get the resources to make a feature, their delight is evident in the lively editing and the exuberant performances. Alexandra Khokhlova, a gangly woman who was married to Kuleshov and starred in most of his films, plays a vamp who tries to lure Mr. West into her toils. Pudovkin, who studied with Kuleshov before going into directing himself, is the well-dressed gang leader who pretends to guide Mr. West away from danger. Boris Barnet, also to become a major director, performs feats of derring-do as Jeddie tries to save Mr. West.

Mr. West is not only a satire on Western fears of post-Revolutionary Russia but also a parody of American serials. (The latter was something Barnet soon tried in an actual serial, his 1926 Miss Mend.)

Mr. West is available on DVD in Flicker Alley’s set, “Landmarks of Early Soviet Film.”

German Expressionism begins to wind down

Last year I was hard put to pick a film to represent the German Expressionist movement in the top ten. I chose Erdgeist but mentioned Schatten and Raskolnikow as runners-up. By 1924 there were fewer Expressionist films released, though the movement would linger on until 1927, mainly carried on by the two greatest directors who had worked in the Expressionist movement: F. W. Murnau and Fritz Lang. Each of these contributed a classic film in 1924: Murnau’s The Last Laugh and Lang’s two-part epic: Die Nibelungen: Siegfried and Kriemhild’s Revenge).

The Last Laugh isn’t really Expressionist. The sets are mildly in the style, but what really fascinated Murnau at this point was the freedom of camera movement introduced by French Impressionism. He set out to make a character study. Emil Jannings plays a doorman in a large hotel (none of the characters’ names are given). His regal bearing and fancy uniform bring him respect among his fellow employees and from relatives and neighbors in the lower-middle-class neighborhood where he lives. He has aged to the point where he carry large luggage and is abruptly demoted to work as a rest-room attendant.

Murnau introduced what came to be known in Germany as the entfesselte Kamera, the “unfastened camera,” beginning in the opening shot where an elevator with a grill descends, carrying the camera and dramatically revealing the lobby. Murnau may have been directly influenced by one of last year’s top-10, Cœur fidèle, where Epstein put his camera on a spinning-swings carnival ride. Murnau saw other uses for the device. Like the Impressionists, he conveyed drunkenness through moving camera, though in this case he put the actor and camera on a turntable, so that the room spins past behind Jannings, conveying the dizzy happiness of the doorman at a party (above).

Using more imagination, Murnau follows sound with his camera. As the party ends, musicians exit to the apartment-block courtyard, and one plays a final tune under the window. Starting with a close-up, the camera “cranes” diagonally up and backward until the men are in long shot. A cut takes us to the doorman inside, happily listening.

Actually the camera was not on a crane. Murnau and cinematographer Karl Freund affixed a track over the courtyard with a small metal elevator underneath, so that the camera could move both back and forth and up and down. The camera was not literally unfastened in these cases, but it looked like it was.

Murnau wanted to end the film on a grim note with the protagonist seated alone in the hotel rest room. Commercial considerations led to a happier ending, however, with him unexpectedly becoming wealthy. The twist was so outrageous that Carl Mayer, the scenarist, considered it a comment on Hollywood’s insistence on happy outcomes. Hence the English title The Last Laugh. The original German means “The Last Man.”

The Last Laugh got distribution in the USA, but it was not a success. Hollywood practitioners studied it, though, and started hanging cameras from tracks themselves and trying other tricks. The track backward above a long, laden banqueting table soon became a cliché of Hollywood cinema.

Murnau would make two more mildly Expressionist films, Tartuffe (1925) and Faust (1926) before heading to Hollywood to make the ultimate hanging-camera film, Sunrise (1927)

The Last Laugh is available from Kino in the USA and Eureka! in the UK.

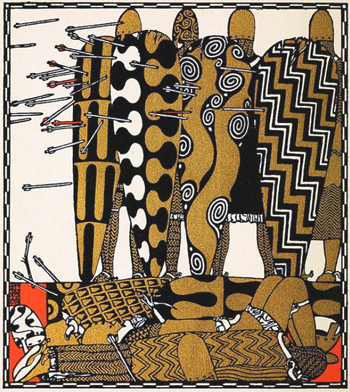

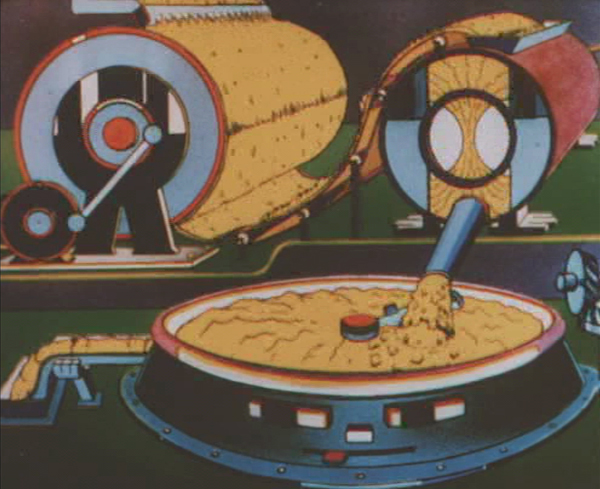

One of my favorite films of the 1920s is Lang’s two-parter, Die Nibelungen: Siegfried and Die Nibelungen: Kriemhilds Rache (Kriemhild’s Revenge). An adaptation of the ancient German myth, it mostly proceeds at a stately pace until the final battle scene. Some may find it slow, especially when compared with the lively, suspenseful Dr. Mabuse der Spieler (1922) and Spione (1928). Yet its leisurely presentation is appropriate to the subject matter. Equally important, lingering over images allows us to notice the details of the extraordinary settings and costumes, with their busy decorated surfaces and their startling arrangements within the shot.

Take the image at the top of this entry. Brunhilde, having been forced to marry King Gunther against her will, envies her sister-in-law Kriemhild, who has married Siegfried, the man Brunhilde loves. In this shot, Brunhilde mounts the steps of Worms Cathedral to confront Kriemhild and assert her right to enter the cathedral first. We see her from behind and then at the upper left as her ladies follow her, wrapped in their patterned hoods and black cloaks, creating an almost abstract composition. Lang build the enormous stairway outside the cathedral in two stages and then used the set imaginatively to stage several ceremonies and dramatic conflicts.

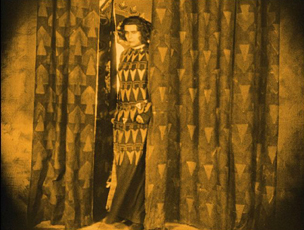

What makes this film Expressionist, I would argue, is the way the actors and settings interact, as in this moment when Brunhilde pauses by her window and then comes forward through the slightly parted curtain, exiting left. She pauses in the opening, her dress seemingly becoming part of the curtains for a moment.

The similarity and the pause have no narrative function, but it’s a very Expressionist composition. Insistent symmetry and acting also contribute to the style. In the second plot, the Hunnish King Etzel asks for Krienhild’s hand in marriage. She agrees on the condition that he will aid her in exacting her revenge on Siegfried’s killers. Upon her move to the land of the Huns, the style becomes a more familiar sort of Expressionism, with distorted trees and buildings that looks like they were built of mud that settled oddly before drying:

The elements of the German tales are all here: love, betrayal, suicide, revenge, presented in images worth savoring.

Lang was inspired in his approach to the film’s visuals by some illustrations by Carl Otto Czeschka for a 1909 retelling of Die Nibelungen published in 1909. The heavy decoration on the knight’s shields and many other surfaces in the film somewhat resemble this image, for example:

Yet the resemblance is far from exact. Clearly Lang used elements from these illustrations and took them off in his own direction.

The film has recently been restored and looks great on Blu-ray. Kino in the US and Eureka! in England have brought it out. Both have DVD editions as well.

Scandinavia’s golden age drawing to a close

During the first half of the 1920s, the Swedish cinema was a victim of its own success. Victor Sjöstrom (who has figured in these lists in 1918 and 1921, as well as in our “Lucky ’13” entry), had headed to MGM, becoming Victor Seastrom. In 1924 he released his first two films in 1924: Name the Man and He Who Gets Slapped. The latter was the newly formed MGM’s first in-house production to be released. It was a huge success, no doubt in large part due to the growing stardom of Lon Chaney, and it put the studio on the map and allowed Seastrom to stay in Hollywood, notably for The Scarlet Letter (1926) and The Wind (1928).

Mauritz Stiller (also a previous top-10 choice) was about to head for Hollywood as well, but his final Swedish film is one of his finest. Gösta Berlings Saga, a epic adaptation of Selma Lagerlöf’s novel, was made in two parts lasting over three hours. Many people will know it as the debut film of Greta Garbo. Fans should be forewarned that she is an important character and appears in the early and late scenes but disappears for a long stretch in the middle.

[December 30: As our friend Antti Alanen points out, Garbo had already acted in a comedy, Luffar-Petter (Peter the Tramp, 1922) and in some short advertisements.]

The film begins with Berling, a drunken pastor in a small town, being relieved of his duties. He ends up being taken in the “Chevaliers” at Ekeby the country estate of Margaretha Samzelius, a tough middle-aged woman who runs a group of foundries she has inherited from a lover. The Chevaliers are a group of hangers-0n, men who can drink and laze about most of the time but who must be charming and entertaining at Samzelius’ many dinner parties. Berling has a number of chances to redeem himself but ends up harming the people around him and sinking lower into despair. He is finally redeemed by the love of the Garbo character, Elizabeth, the new bride of a wealthy neighbor, to whom, it turns out through a technicality–and happy coincidence–she is not actually married.

Hansen and Garbo make a gorgeous couple (below left), but they are upstaged by the great Swedish stage actress Gerde Lundequist as Samzelius:

As usual, the film contains lovely scenes in the Swedish landscapes. There are some impressive night sleigh rides, including a famous scene in which Berling and Elizabeth are chased across a frozen lake by wolves. There is also one of the most impressive fire scenes I can recall from the silent era, as Samzelius’ efforts to smoke the Chevaliers out of the guest house where they live and inadvertently sets fire to the big main house as well.

Unfortunately the film was cut down into a single feature for its release outside Scandinavia. The Story of Gosta Berling was the main version that circulated for many years. The Swedish Film Institute restored it in stages as more footage was found, but the current print, at 183 minutes, is still missing some footage.

Beware picking up an older video release with the truncated film. The restored version was released on DVD in the USA by Kino. The original Svensk Filmindustri release (with English, French, Portuguese, German, and Spanish subtitles), is available here. The same DVD comes in a box set of six Swedish silent classics, which is widely available from the usual online sources.

Carl Dreyer has popped up on this blog several times, usually in passing. Not surprising, since David wrote a book about him way back 1981. Here he makes his second appearance on our ten-best lists (the first having been for his first feature, The President, in 1919) with Michael.

The film centers around a wealthy, aging artist, Claude Zoret. The main room of his house is decorated with several eye-catching pieces of sculpture, notably a mysterious battered head that looms in the background of many shots. Is it one of Zoret’s own works? Is it part of a collection of ancient statues? Much of the action takes place here, which has led some historians to place Michael in the tradition of the Kammerspiel. David calls it a borderline case. There are certainly scenes that leave Zoret’s studio, most notably one in a large theater set.

The film has been hailed as an early treatment of homosexuality. Although there is nothing overtly expressed, it is hard not to read such a subtext into the action. Zoret, wonderfully played by Danish director Benjamin Christensen, has many guests and admirers visit him, creating a little all-male coterie. He has taken in a young protegé, a very beautiful and very young Walter Slezak. Zoret refers figuratively to Michael as his son, but there seems to be another tie between the two. Moreover, there may be a hint that Charles Switt, a journalist apparently writing a biography of Zoret (at the center of the frame above), feels some jealousy toward the young man.

Trouble begins when a princess comes to commission a portrait from Zoret. Although he usually doesn’t do commissions, he is intrigued by her face and agrees. During her visits to the studio to pose, she meet Michael, who is immediately smitten. The affair continues as Michael becomes increasingly inconsiderate to Zoret,borrowing money to continue the affair and missing an important showing of his work. In contrast, Zoret shows unwavering generosity to Michael, despite being devastated by his desertion.

Ultimately Zoret paints his last work, showing an elderly, lonely man against a barren seascape. It is hailed as a masterpiece at a party which Michael does not attend.

The character study proceeds at Dreyer’s usual formal pace, and yet it is never dull. As much as any of his silent films, it looks forward in tone to his later sound ones.

A very nice print of Michael is available in the UK from Eureka! (not deliverable to the USA); Kino released what I assume is the same print in the USA.

She was nothing but a poor flower-maker

Every now and then I want to put a film on the list which is impossible to see unless you happen to live near one of the archives that has a print and they happen to program it. Still, in the hope of inspiring someone to restore it and make it available, I proceed.

The film is Jean Epstein’s L’Affiche (“The Poster”). Epstein first made our list last year for the much better known Cœur fidèle. L’Affiche is a bit like the earlier film, a simple melodrama made in the French Impressionist style. Its situation is highly conventional, and its plot depends on a massive coincidence.

The heroine is introduced as Marie, one of several women making artificial flowers. On her lunch break she thinks back to a romantic day she spent in the country. There she meets a young man, Richard. The couple go to an expensive restaurant, and Richard seduces Marie, and then abandons her, driving away alone the next morning.

Three years pass, and Marie has a small child, also named Richard. She enters him in a contest for the most beautiful child, with a cash prize, offered by an insurance company that wants to put the winner on their advertising posters. The boy wins, and Marie signs a 10-year contract for the rights to use little Richard’s image.

The child dies, however, and Marie visits his grave. As she leaves, she sees a huge poster with his image. The campaign has begun. Everywhere in Paris she goes, she sees the poster and finally begs the insurance company to end the campaign. The boss, however, refuses. Marie begins tearing down the posters, and she is soon arrested. Epstein handles the arrest scene without an establishing shot but builds it up through close-ups.

Initially we see only the back of Marie’s head and her arms tearing down a poster. There a cut-in to slightly closer framing as a policeman’s hand comes into the shot and touches her shoulder. A third shot shows her turning to the officer and staring in a way that suggests she is becoming mentally unbalanced. Finally a long shot establishes the scene as a second policemen enters to help arrest her.

It’s the sort of gradual revelation of space that Kuleshov was working with at the same time.

The boss of the insurance company is informed of this and sends his son to file a complaint against her. New copies of the poster are being put up all over town. The son is none other than the Richard who seduced Marie years before. Hearing her tale, he asks her forgiveness and takes her home to his parents. The father forbids their marriage, they marry anyway, and eventually (after his own younger child dies!), the boss blesses the marriage and agrees to take down the posters.

Summarized baldly, it sounds like an impossible plot to take seriously, but Epstein’s delicate, understated approach in presenting it and Nathalie Lissenko’s affecting performance as Marie manage to make it a great film. It’s full of Impressionist moments: Marie’s memory of her romantic day with Richard, a dance scene with rhythmic editing, a dream sequence, and plenty of gauzy shots and fancy wipes at transitions.

Earlier this year I complained because L’Affiche was not included in the big new box set of Epstein’s work, despite almost everything else from the period being there. It’s also not on the box set of films made at the Russian emigré studio, Albatros, even though Epstein’s other three Albatros films are there. I don’t whether there are rights problems or there simply isn’t a good enough print.

At least one streaming service claims to have L’Affiche available, but a search turns up numerous complaints about the site.

I should make mention of one other Impressionist film that came out in 1924. Perhaps it should be on the list rather than L’Affiche. It’s Marcel L’Herbier’s L’Inhumaine. L’Herbier appeared on our 1921 list for El Dorado, and even then I expressed reservations. Most of his films seem cold and by-the-numbers to me, not to mention a bit pretentious. But his films were historically important, and L’Inhumaine was influential in its use of art deco sets. At one time the film was available on DVD, but it seems to be out of print.

Three funny men …

And no, it’s not Chaplin, Keaton, and Lloyd this time. Chaplin didn’t release a film in 1924. His next would be what many would consider his funniest feature, The Gold Rush.

Over the years I’ve stressed that during the 1910s, the three great comics were working in shorts, honing their filmmaking and working up to their great series of features. By 1923 they had fully made the transition: Lloyd made Safety Last and Keaton Our Hospitality. Safety Last had a simpler plot, structured mainly by the stages of the hero’s climb up a building. Keaton went further with a complex story of a romance blooming between members of feuding families, using multiple locations, a developing causal line, and clever motifs. (We analyze it in Chapter 4 of Film Art: An Introduction.)

In 1924, Lloyd achieved a similar complexity with Girl Shy, one of his greatest films. He plays a bashful young tailor’s assistant who is terrified of women. Yet in secret he writes a guide for seducers, taking on the narrational persona of a jaded man of the world. Clearly he has taken his inspiration from movies of the day. The imaginary scenes from his book dramatize his success in gaining the love of a vamp (see bottom) and a flapper. The publishers decide that the book is so over the top that they will publish it as a comic story. During all this Harold develops a relationship with Mary, a quiet young woman from a wealthy family. When her father tries to buy Harold off, he pretends to spurn Mary. She is about to marry a rich man, but Harold determines to stop the wedding.

There develops one of the most epic chase scenes in all silent comedy, and indeed all cinema, as Harold commandeers all manner of vehicles, from cars and wagons to a firetruck and a speeding trolley (above).

Even Keaton never outdid that one. But from 1923 to 1927, these two each created a string of innovative, carefully crafted, hilarious films.

Girl Shy used to be available in a 3-DVD set from New Line, but that is no longer available–though one optimistic third-party seller offers it, still sealed in plastic, for $399.99). Now the individual releases of each DVD seem to be slipping out of print as well. Volume 1, which contains Girl Shy, is definitely out of print. Be forewarned: Volume 2, which includes the wonderful 1927 film The Kid Brother (look for it on a future list) seems like it’s not long for this world, and the same is true of Volume 3, with For Heaven’s Sake (1926).

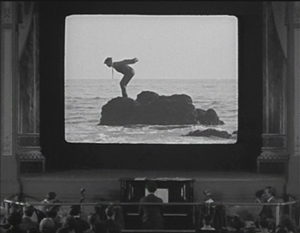

It was difficult to choose between Keaton’s two major releases of 1924, Sherlock Jr. and The Navigator. I chose the former mainly because of its perpetually astonishing transition from the frame story of a small-town projectionist unlucky in love to his dream of himself as a sophisticated detective. His dream takes the form of a movie, and the sleeping projectionist walks through the theater and into the onscreen action. With extraordinary precision, Keaton maintains a long-take framing of the pianist and audience in the auditorium while the hero onscreen undergoes a series of unexpected shot changes. In each he is in the same pose and position within the screen, but the backgrounds change arbitrarily, as when he begins to dive from a rock into the ocean and finds himself landing in a snowdrift:

The result is a marvelously convincing technical feat, giving the illusion of being a single shot as far as the theater is concerned and on the movie screen a character wandering through an appropriately dream-like series of edited shots. In general, Keaton was the most adept of the three great comics at using cinema technology to create gags, and this is his most elaborate attempt. (Though see also his short, The Playhouse, in which multiple exposures, flawlessly managed in-camera, create Keaton clones that play all the roles.)

The plot of the dream emerges after this virtuoso transition, and it remains hilarious throughout. The chase, while not quite as dazzling as the one in Girl Shy, has considerable variety of vehicles (one wonders if the two comics were consciously trying to best each other), including a passage where the hero rides the handlebars of a speeding motorcycle, unaware that the driver has fallen off.

Kino has packaged Sherlock Jr. together with Keaton’s early feature, The Three Ages (1923), and released them both on DVD and Blu-ray.

The third funny man was Ernst Lubitsch. The Marriage Circle was his second Hollywood film, and one of his best. Lubitsch had started out as a comic in silent shorts in Germany, but unlike the famous Americans, he entirely gave up acting to direct. Not that he directed only comedies, but his best films, including Lady Windermere’s Fan, Trouble in Paradise, and The Shop around the Corner, fall into that category.

The Marriage Circle is a light romantic comedy, following a chain of flirtations and misunderstandings. Prof. Stock has realized that his pretty young wife Mizzi has begun to neglect and nag him. She is soon attracted a newlywed, Dr. Braun. Mizzi happens to be an old friend of Braun’s wife Charlotte, which gives her opportunities to flirt aggressively with Braun. Charlotte is in turn admired by Braun’s medical partner, Dr. Mueller, though she laughs off his attempts to woo her.

It has often been pointed out that Lubitsch is a director of doorways. That’s not always true, but The Marriage Circle is built around visits. The five characters visit each other in various combinations, and the string of attempted seductions and jealousies builds. Stock encourages Mizzi’s pursuit of Braun, since he wants an excuse for a divorce. Charlotte naively pushes Braun into visiting Mizzi at home when she plays sick.

The sets and especially the doorways play a big role. Characters pause in doorways to take in a compromising situation they have interrupted. At one point Mizzi comes to Braun’s office. Mueller spots them in an embrace, but Braun claims he’s hugging his wife. Eager to alienate Charlotte from her husband, he opens the office door to reveal Charlotte in the waiting room:

This is the first film where one can see the “Lubitsch touch” in action. It’s an ability to use film techniques to hint at something naughty. Here the innuendos are aimed at the characters. We know more than any of them does, and the humor arises from watching them misinterpret what they see and hear. When they finally learn of their mistakes, they end the “circle” of the title.

The Marriage Circle is available to rent or buy in digital form on Amazon. I know nothing about the source or the quality. The only DVD easily available is a region 2 French one under the rather blah title Comédiennes. The print is distinctly soft (as the frame above suggests) but acceptable until a better one becomes available.

… and one not so funny

Greed is often spoken of as the film that historians and buffs would most like to see rediscovered. Part of it survives, of course–about two hours out of the original eight or so. Its producer, MGM, had it was edited down into a reasonably coherent feature, mainly by cutting out a number of characters and their subplots. I won’t say much about the film here, since it is already quite well-known.

The film is an adaptation of Frank Norris’ novel McTeague done in a naturalistic style, which was unusual for Hollywood films of that or any other day. It follows McTeague, an unlicensed dentist, who steals his friend Marcus’ girlfriend, Trina, and marries her. Their luck fluctuates, as Trina wins a lottery and McTeague is thrown out of work for not having a license. Trina becomes an obsessive miser, and McTeague, by now an alcoholic, murders her and flees to Death Valley with her money.

I find a lot of Greed heavy-handed and obvious. (I prefer the simpler Blind Husbands, which made our ten-best list for 1919.) It has an interesting style, however, with a lot of proto-Wellesian deep focus and low angles, complete with, in the case of the frame above, a hint of a ceiling. The final sequence in Death Valley is also very effective.

Apart from being 75% lost, Greed has never been released on DVD. (See Indiewire for comments on this.) In 1999 Turner Classic Movies edited a four-hour version, inserting production stills to suggest the missing scenes. This was reasonably effective, but it seems impossible to find a print of it that is not washed out and fuzzy. We’ve tried taping off TCM, as well as buying the VHS and laserdisc releases of that version. They all verge on unwatchable. I hope that the situation is not left where it is and that a true restoration is eventually done. My frame above comes from an archival 35mm print, so clearly better material exists.

The lost film that I would most like to see discovered is Lubitsch’s Kiss Me Again (1925). Given that it was made right before Lady Windermere’s Fan, there’s a good chance that it’s a masterpiece.

One of a kind

Last year I put Man Ray’s experimental short, La retour à la raison, on the list. Comparing experimental shorts to fiction features, though, seems unfair. This year I’m separating out the experimental category and will try to choose at least one film each year.

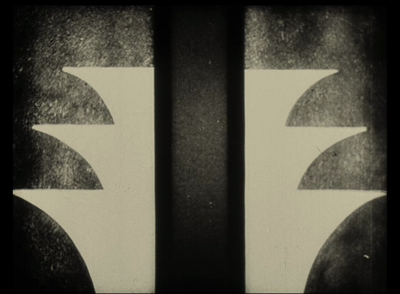

This year it’s Walter Ruttmann’s Opus 3, the third of his four films done with abstract animation.

All of the Opus films plus other Ruttmann shorts are available on a DVD set with Berlin, die Sinfonie der Grossstadt and Melodie der Welt. If you want to sample just Opus 3, which is about four minutes long, it has been posted multiple times on YouTube. Although a bit dark, this is the best copy I’ve found, and it has a nice, appropriate score by Hanns Eisler.

Bernard Eisenschitz made the connection between Lang and Czeschka in his massive Fritz Lang au travail (Cahiers du Cinéma, 2012) , pp. 38 and 42. Czeschka’s Nibelungen illustrations can be see along with the entire book on the Museum of Modern Art’s website, with a page-turning feature and the ability to enlarge the pages considerably. Individual illustrations can be found with a Google Images search on “Czeschka” and “Nibelungen.”

Thanks to Jonah Horwitz for a correction.

Girl Shy

DVDs and Blu-rays for your letter to Santa

The Cure (1917)

Kristin here:

One occasional feature of our blog has been to point out new releases on DVD and Blu-ray, especially of titles that haven’t gotten much publicity. Some of these are easily available at major sources like Amazon, while others have to be ordered directly from their publishers, often abroad. But if you have a multi-standard player, don’t hold back. Ordering from abroad isn’t as intimidating as it might seem. Many sites have English-language sales pages.

We’ve done a lot of these entries by now. You can find them through the DVD category in the list at the right, but I thought it might be useful to give links to all of them here, with brief indications of what each deals with. Some of the DVDs are probably out of print by now, but in this era of eBay and third-party sellers, one can usually track down such things. Then I’ll give a rundown on some recent releases.

The first was Dispatch from the Land of the Long White Cloud, written when David and I were fellows at the University of Auckland in May, 2007. I discussed some of the DVDs of New Zealand films that I had found in stores there. Some are famous, some obscure.

2008 was either a great year for DVDs or we just had more time to deal with them. On January 18, I posted Tracking down Aardman creatures, a guide to the classic animated films of Nick Park, Peter Lord, and their colleagues at Aardman. At the time it was probably the most complete information one could get on these films. Of course, Aardman has gone on to make other films and TV series, but this was the studio’s golden age. On February 1, I described with two boxed sets dealing with early sound films in All singing! All dancing! All teaching! As the title implies, these are a boon to film teachers, as well as buffs and researchers. In Coming attractions, plus a retrospect (June 6), David discussed the release of Robert Reinert’s very peculiar silent film, Nerven, and in Summer show and tell (July 28, 2008), he briefly dealt with a miscellaneous set of DVDs and books that we discovered during our annual visit to Il Cinema Ritrovato and other destinations. On December 10, in Preserving two masters, I discussed the restored version of Lubitsch’s Das Weib des Pharao (which at that point wasn’t out on DVD) and a Walter Ruttmann set.

2009 was a pretty good year, too. On February 18, I wrote about the Flicker Alley release of Abel Gance’s influential classic La roue, including historical background on the film, in An old-fashioned, sentimental avant-garde film. David took the occasion of of a new Criterion boxed set to summarize the work of the fine Japanese director Shimizu Hiroshi (May 9). On May 21, in Forgotten but not gone: more archival gems on DVD, I described two major boxed sets, one of Lotte Reiniger’s lovely but seldom-seen fairy-tale shorts, and one of early Belgian avant-garde cinema–and yes, the early Belgian avant-garde cinema includes some important titles. On August 2, David again caught up with the mixed batch of DVDs and books picked up in Europe over the summer or sitting in the stack of mail upon his return, in Picks from the pile. Finally, on November 9 I discussed the British release of Dreyer’s Vampyr with a very worth-while commentary track by Guillermo del Toro, who said, among other things, “I am not Carl Dreyer, and I should shut up.”

In February of 2010, I wrote DVDs for these long winter evenings, dealing with three sets with the work of three crucial filmmakers: Georges Méliès, Ernst Lubitsch (most of the German features), and Dziga Vertov. In October, it was More revelations of film history on DVD: a documentary on Veit Harlan, a new series of Soviet silent films, and the Flicker Alley set of Chaplin’s Keystone films. (For the follow-up, see below.) On November 28, Silents nights: DVD stocking-stuffers for those long winter evenings covered little-known Norwegian and Danish silents, a rare Expressionist film, Ford’s The Iron Horse, hilarious Max Davidson comedies, and the Kalem company.

For some reason it was a full year before we posted more DVD coverage in our second Christmas-gift-themed entry, Classics on DVD and Blu-ray, in time for a fröliche Weihnachten! (November 29, 2012). It probably took us that long to get through all the discs we picked up in Bologna and elsewhere. The title reflects the heavily German coverage: early Asta Nielsen films, Pabst’s first feature, the release of Das Weib des Pharao on DVD and Blu-ray, as well as the 1939 Hollywood version of The Mikado.

Earlier this year, on June 20, we posted our most recent DVD/Blu-ray entry, Recovered, discovered, and restored: DVDs, Blu-rays, and a book. It deals with a burst of releases of Norwegian silent films, a new entry in the “American Treasures” archive series, and some American films, famous and obscure.

Now more DVDs are piling up, and the time seems ripe for a third set of holiday-present suggestions, to give or hope to receive.

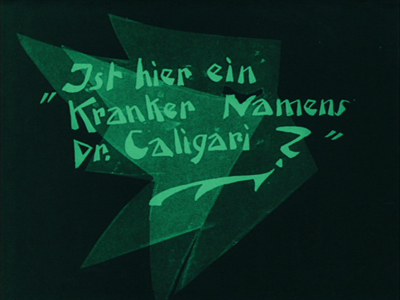

Caligari, restored at last

In our survey of the ten best films of 1920, I mentioned that Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari was one of the films that lured me into film studies during my undergraduate days. I know it very well. I was tempted to go to one of the screenings of the recent restoration this year at Il Cinema Ritrovato, but it was opposite other films I had never seen before, so I passed it up. Luckily now Kino Lorber has brought that restoration out on DVD and Blu-ray (sold separately).

The negative of Caligari does not survive in its entirety, but the restoration has taken the usual steps to fill it in and provide authentic tinting. The information comes from titles at the beginning of the DVD print:

The 4K restoration was created by the Friedrich-Wilhelm-Murnau-Stiftung in Wiesbaden from the original camera negative held at the Bundesarchiv-Filmarchiv in Berlin. The first reel of the camera negative is missing and was completed from different prints. Jump cuts and missing frames in 67 shots were completed by different prints.

A German distribution print is not existing. Basis for the colours were two nitrate prints from Latin America, which represent the earliest surviving prints. They are today at the Filmmuseum Düsseldorf and the Cineteca di Bologna.

The intertitles were resumed from the flashtitles in the camera negative and a 16mm print from 1935 from the Deutsche Kinematek-Museum für Film und Fernsehen in Berlin.

The digital image restoration was carried out by L’Immagine Ritrovata-Film Convservation and Restoration in Bologna.

The images are definitely clearer, with more detail visible than in prints I have seen before, and the film runs more smoothly. An inauthentic intertitle has been removed. In most prints, when the grumpy town clerk hears that Caligari wants a permit to exhibit a somnabulist, he calls him a “Fakir” and turns him over to his underlings to deal with. That title is now gone, and it’s clear that Caligari is annoyed at the man’s disdainful attitude rather than a specific insult. The intertitles have their original jagged, Expressionistic graphic design (see above) rather than the plain backgrounds used in many prints hitherto available.

There are optional English subtitles. The modernist musical track fits well with the film.

The supplements include a short essay which I provided and a documentary, Caligari: How Horror Came to the Cinema. The restoration is also available from Eureka! in the United Kingdom, with a different set of supplements and with DVD and Blu-ray sold together.

Flooded by flickers

If you want a lot of good laughs and have 1005 minutes to spare, Flicker Alley’s “The Mack Sennett Collection Volume One” offers 50 restored shorts which Sennett acted in, wrote, directed, and/or produced. (This 3-disc set is available only on Blu-ray.)

The films are presented in chronological order, starting with a 1909 comic short directed by D. W. Griffith at American Biograph and starring Sennett, The Curtain Pole. Two comedies directed by Sennett at American Biograph follow. In 1912 he founded Keystone, represented starting with The Water Nymph (1912) and ending with A Lover’s Lost Control (1915). In 1915 Sennett became one of the three points in the Triangle Film Corporation, along with co-founders Griffith and Thomas Ince. Keystone continued operating as Triangle Keystone, and films from that production unit from 1915 to 1917 are included. At that point Sennett went independent as Mack Sennett Comedies, making mainly two-reelers, beginning in this collection with Hearts and Flowers (1919) and running to The Fatal Glass of Beer (1933). See here for a complete list of titles. Each of the three discs contains a group of films as well as a set of bonuses at the end.