Archive for the 'Silent film' Category

Unveiling Ebertfest 2014

Kristin here:

In the early days of Ebertfest, Roger personally introduced every film at this five-day event, which took place this year from April 23 to 27. He would be onstage for the discussions and question sessions after each screening, often joined by directors, actors, or friends in the industry.

In the summer of 2006, there began the long battle with cancer that Roger fought so determinedly. He withdrew gradually from full participation in the festival that he had founded in his hometown of Champaign-Urbana sixteen years ago. He struggled to immerse himself in the festival, even though repeated surgeries had robbed him of his voice. He introduced fewer films, doing so with his computer’s artificial voice, and when even that became too taxing, he sat in his lounge chair at the back of the Virginia Theater, enjoying the event and occasionally appearing onstage with a cheery thumbs-up. Finally, last year on April 4, less than three weeks before the fifteenth Ebertfest, he passed away. That year’s festival became a celebration of his life.

The celebration continued this year, though on a more upbeat note. Some films were chosen from a list that Roger had left to his wife Chaz and festival organizer Nate Kohn, and they selected others in the same indie spirit. The tradition of showing a silent film with musical accompaniment was maintained. As always, the festival passes sold out, and the crowd, including many long-time regulars, enthusiastically cheered both films and filmmakers.

The tributes

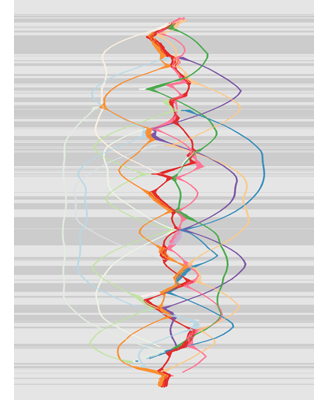

Roger did not live to see the documentary devoted to his life and based on his popular memoir of the same name, Life Itself. It premiered in January at this year’s Sundance Film Festival. He participated in its making, however, encouraging director Steve James (whose 1994 documentary Hoop Dreams Roger had championed) to film him during the final four months of his life. Some of this candid footage reveals the painful and exhausting treatments Roger underwent, but much of it stresses his resilience and the support of Chaz and the rest of his family.

Life Itself was the opening night film. James has done a wonderful job of capturing the spirit of the book and in assembling archival footage and photographs, interspersed with new interviews. The result is anything but maudlin, with a candid treatment of Roger’s early struggles with alcoholism and an amusing summary of Roger’s prickly but affectionate relationship with his TV partner Gene Siskel.

Life Itself was picked up for theatrical distribution by Magnolia Pictures and will receive a summer release, followed by a showing on CNN. (Scott Foundas reviewed the film favorably for Variety, as did Todd McCarthy for The Hollywood Reporter.)

Another tribute followed the next day, when a life-size bronze statue of Roger by sculptor Rick Harney was unveiled outside the Virginia Theater (above). Harney portrays Roger in his most famous pose, sitting in a movie-theater seat and giving a thumbs-up gesture. There is an empty seat on either side of him, so that people can sit beside the statue and have their photos taken. (See the image of Barry C. Allen in the section “Of Paramount importance,” below.)

Far from silent

Roger was a big fan of the Alloy Orchestra, consisting of (L to R above) Terry Donahue, Ken Winokur, and Roger Miller, who specialize in accompanying silent films. They have appeared several times at Ebertfest, playing original music for such films as Metropolis and Underworld. Rather than taking a traditional approach to silent-film music, using piano, organ, or small chamber ensemble, they compose modern scores, played on electronic keyboard combined with their well-known “rack of junk” percussion section, including a variety of found objects, supplemented with musical saw, banjo, accordion, clarinet, and other instruments. The result is surprisingly unified and provides a rousingly appropriate accompaniment to the silents shown at Ebertfest over the years.

I have had the privilege of introducing the film and leading the post-film Q&A on some of these occasions, including for this year’s feature, Victor Seastrom’s 1924 classic, He Who Gets Slapped. (Swedish director Victor Sjöström used the Americanized version during his career in Hollywood.) I put the film in context by pointing out three important historical aspects of the film. First, it was the first film made from script to screen by the newly formed MGM studio, formed in 1924 from the merger of Goldwyn Productions, Metro, and Louis B. Mayer Pictures. (Two earlier releases by MGM were Norma Shearer vehicles which originated at Mayer.) Second, it was probably the film that cemented Lon Chaney’s stardom, after his breakthrough role as Quasimodo in the 1922 Hunchback of Notre Dame. Starting in 1912, Chaney had been in well over 100 films before Hunchback, many of them shorts and nearly all of them supporting roles. Third, He Who Gets Slapped was Seastrom’s second American film after Name the Man in 1923, and a distinct improvement on that first effort.

Naturally MGM wanted a big, prestigious hit for its first production, and He Who Gets Slapped came through, being both a critical and popular success–and also boosted Norma Shearer to major stardom. Seastrom and Chaney both stayed on at MGM, though the former returned to European filmmaking after the coming of sound and Chaney died in 1930.

I was joined for the post-film discussion by Michael Phillips of the Chicago Tribune, and we talked with Donahue and Winokur while Miller sold the group’s CDs and DVDs in the festival shop. They revealed that this new score had been commissioned by the Telluride Film Festival and that it was a project that appealed to their taste for off-beat films. There were many questions from the audience, and we suspect that the Alloy Orchestra will continue to be a regular feature of the festival.

A cornerstone of indie cinema

Although Roger was occasionally criticized for supposedly lowering the tone of film reviewing by participating in a television series, he and partner Gene Siskel regularly tried to promote indie and foreign films that didn’t get wide attention. Roger did the same in his written reviews, and Ebertfest was originally known as the “Overlooked Film Festival.” Inevitably it was shortened by many attendees to “Ebertfest,” and eventually that name became official. It reflects the wider range of films that came to be included, with the silent-film screening and frequent showings of 70mm prints of films like My Fair Lady that were hardly overlooked.

Among Roger’s friends was Michael Barker, co-founder and co-president of Sony Pictures Classics, one of the most important of the small number of American companies still specializing in independent and foreign releases. A long-time Ebertfest regular, Barker usually brings a current or recent release to show, along with filmmakers or actors. This year he was doubly generous, bringing Capote (2005, above), to which Roger had given a four-star review, and the current release Wadjda (2012).

Roger never reviewed the latter, but it is certainly the sort of film that he loved: a glimpse into a little-known culture by a first-time filmmaker with a progressive viewpoint. Wadjda is remarkable as the first feature film made in Saudi Arabia, where there are no movie theaters. Moreover, it was made by a woman, Haifaa Al-Monsour, and tells the story of a little girl who defies tradition by aspiring to buy and ride a bicycle in a country where this, like women driving cars, was illegal. (Below, Wadjda learns to ride a bicycle on a rooftop, hidden from public view.)

Both the film and Al-Monsour thoroughly charmed the audience. Barker interviewed her afterward, and she revealed that, not surprisingly, the making of the film was touched by the same sort of repression that it portrays. Women are not allowed to work alongside men in Saudi Arabia, so Al-Monsour had to hide in a van while shooting on location. Given that there is no cinema infrastructure in the country, the film was a Saudi Arabian-German co-production, with Arabic and German names mingling in the credits. We also learned that it has since become legal for Saudi girls to ride bicycles. Perhaps someday filmmaking will become more common there, and male and female crew members can work openly together.

Naturally Wadjda was made with a digital camera, since this new technology is crucial to the spread of filmmaking in places like the Middle East where there is little money or equipment for production. In contrast, Capote was shown in a beautiful widescreen 35mm print that looked great spread across the entire width of the Virginia’s huge screen. Naturally the screening became a tribute to the late Phillip Seymour Hoffman, giving his only Oscar-winning performance (out of four nominations) in the lead role.

Barker had brought with him a surprise guest, Capote‘s director, Bennett Miller, whose appearance had not been announced in advance. He discussed how he and scriptwriter Dan Futterman learned that there was a second, rival Capote film in the works, Infamous (2006), which also dealt with the period when the author was researching In Cold Blood. Miller and Futterman decided to press ahead, a wise move in that their film drew more attention than did Infamous. Much of the discussion was devoted to Hoffman’s performance and his acting style in general.

Capote was Miller’s first fiction feature. He had come to public attention with his documentary The Cruise (1998), which Roger had given a brief three-star review. Roger continued his support for Miller with a four-star review for Moneyball (2011). It’s a pity he did not live to see Miller’s latest, Foxcatcher, which will be playing in competition at Cannes in May.

Overlooked no longer

Perhaps no young filmmaker better demonstrates the impact that Roger’s support can have on a career than Ramin Bahrani. Roger saw his first feature, Man Push Cart, at Sundance in 2006 and invited it and the filmmaker to the  “Overlooked Film Festival” that April. (Roger’s Sundance review is here.) The film then played other festivals, notably Venice and our own Madison-based Wisconsin Film Festival. It won several awards, including an Independent Spirit Award for best first feature. In October Roger gave the film a more formal review, awarding it four stars. Man Push Cart never got a wide release, and it certainly didn’t make much money. Still, quite possibly the high profile provided by Roger’s attention allowed Bahrani to move ahead with his career.

“Overlooked Film Festival” that April. (Roger’s Sundance review is here.) The film then played other festivals, notably Venice and our own Madison-based Wisconsin Film Festival. It won several awards, including an Independent Spirit Award for best first feature. In October Roger gave the film a more formal review, awarding it four stars. Man Push Cart never got a wide release, and it certainly didn’t make much money. Still, quite possibly the high profile provided by Roger’s attention allowed Bahrani to move ahead with his career.

His second film, Chop Shop, brought him to Ebertfest a second time, in 2009. (Roger’s program notes are here, and his four-star review here.) At about that time, Bahrani’s third film, Goodbye Solo, was released. Given its modest budget, it did reasonably well at the box office, grossing nearly a million dollars worldwide (in contrast to Man Push Cart‘s roughly $56 thousand). Bahrani inched toward mainstream filmmaking with At Any Price (2012), starring Dennis Quaid and Zac Efron, and he is currently in post-production on 99 Homes, with Andrew Garfield, Michael Shannon, and Laura Dern. During the onstage discussion, he spoke of struggling to maintain a balance between the indie spirit of his earlier films and the more popularly oriented films he has recently made.

Bahrani visited Ebertfest for a third time this year, belatedly showing Goodbye Solo. We had enjoyed this film when it came out, and it holds up very well on a second viewing. It’s a simple story of opposites coming together by chance. An irrepressibly talkative, friendly immigrant cab driver, Solo (a nickname for Souléymane), becomes concerned when a dour elderly man engages him for a one-way trip to a regional park whose main feature is a windy cliff. He fears that William is planning suicide. Solo arranges to drive William whenever he calls for a cab and even becomes his roommate in a cheap hotel. Gradually, with the help of his young stepdaughter Alex, he seems to draw William out of his defensive shell.

As in Bahrani’s earlier films the main character is an immigrant and played by one, using his own first name (Souléymane Sy Savané). He’s the main character in that we are with him almost constantly, seeing William only as he does. William is a vital counterpart to him, however. He is perfectly embodied by Red West, an actor who worked for Elvis Presley and did stunt work and bit parts in films and television since the late 1950s. He may look vaguely familiar to some viewers, but he’s not really recognizable as a star and comes across convincingly as an aging man buffeted by life’s misfortunes.

Most of the film takes place in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, Bahrani’s hometown, with many moody, atmospheric shots of the cityscape at night. One crucial scene involves a drive into the woods and mountains, however, and much of it is filmed in a dense fog. One questioner from the audience asked if Bahrani had planned to shoot in such weather or if, given his short shooting schedule, the fog turned out to be a hindrance to him. He responded that he had dreamed of being able to shoot in fog and that the weather cooperated on the three days planned for that locale. In fact, he re-shot some images as the fog became denser, to keep the scene fairly consistent.

Bahrani’s presence at Ebertfest spans half its existence, from 2006 to 2014. As the festival becomes more diverse in its offerings, it is good to have him back as a reminder of the Ebertfest’s early emphasis on the “overlooked.”

Of Paramount importance

Logo for National Telefilm Associates, TV syndication arm of Republic Pictures.

DB here:

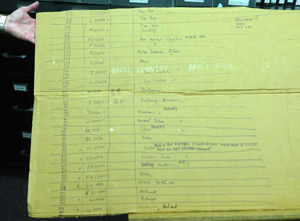

Among the guests at this year’s E-fest was Barry C. Allen. For over a decade Barry was Executive Director of Film Preservation and Archival Resources for Paramount. That meant that he had to find, protect, and preserve the film and television assets of the company—including not just the Paramount-labeled product but libraries that Paramount acquired. Most notable among the latter was the Republic Pictures collection.

We may think of Republic as primarily a B studio, but it produced several significant films in the 1940s and 1950s—The Red Pony, The Great Flammarion, Macbeth, Moonrise, and Johnny Guitar. John Wayne became the most famous Republic star in films like Dark Command, Angel and the Badman, and Sands of Iwo Jima. John Ford’s The Quiet Man was Wayne’s last for the studio, which folded in 1959. Next time you see one of the gorgeous prints or digital copies of that classic, thank Barry for his deep background work that underlies the ongoing work of his dedicated colleagues.

Barry told me quite a lot about conservation and restoration, but just as fascinating was his account of his earlier career. A lover of opera, literature, and painting since his teenage years, he was as well a passionate movie lover. An Indianapolis native, he thinks he saw his first movie in 1949 at the Vogue, now a nightclub. He projected films in his high school and explored still photography. He was impressed when a teacher told him: “If you want to make film, learn editing.” Soon he was in a local TV station editing syndicated movies.

Barry told me quite a lot about conservation and restoration, but just as fascinating was his account of his earlier career. A lover of opera, literature, and painting since his teenage years, he was as well a passionate movie lover. An Indianapolis native, he thinks he saw his first movie in 1949 at the Vogue, now a nightclub. He projected films in his high school and explored still photography. He was impressed when a teacher told him: “If you want to make film, learn editing.” Soon he was in a local TV station editing syndicated movies.

Hard as it may seem for young people today to believe, in the 1950s TV stations routinely cut the films they showed. Packages of 16mm prints circulated to local stations, and these showings were sponsored by local businesses. Commercials had to be inserted (usually eight per show), and the films had to be fitted to specific lengths.

WISH-TV ran three movies a day, and two of those would be trimmed to 90-minute air slots. That meant reducing the film, regardless of length, to 67-68 minutes. Barry’s job was to look for scenes to omit—usually the opening portions—and smoothly remove them. Fortunately for purists, the late movie, running at 11:30, was usually shown uncut, and then the station would sign off.

By coincidence I recently saw a TV print of Union Depot (Warners, 1932) that had several minutes of the opening exposition lopped off. We who have Turner Classic Movies don’t realize how lucky we are. Fortunately for film collectors, some stations, like Barry’s, retained the trims and put them back into the prints.

While working at WISH-TV, Barry began booking films part-time. He programmed some art cinemas in the Indianapolis area during the early 1970s, mixing classic fare (Marx Brothers), current cult movies (Night of the Living Dead), and arthouse releases like Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie—a bigger hit than anyone had anticipated. He also helped arrange a visit of Gloria Swanson with Queen Kelly; she carried the nitrate reels in her baggage.

At the same time, Barry was learning the new world of video editing, with ¾” tape and telecine. Because of his experience in television, Barry was contacted by Paramount to become Director of Domestic Syndication Operations. His chief duty was to deliver films to TV stations via tape, satellite, and prints. From that position, he moved to the preservation role he held until 2010, when he retired.

Barry is a true film fan. He has reread Brownlow’s The Parade’s Gone By many times and retains his love for classic cinema. The film that converted him to foreign-language cinema was, as for many of his generation, Children of Paradise, but he retains a fondness for Juliet of the Spirits, The Lady Killers, and other mainstays of the arthouse circuit of his (and my) day. He’s proudest of his work preserving John Wayne’s pre-Stagecoach films.

It was a great pleasure to hang out with Barry at Ebertfest. Talking with him reminded me that The Industry has long housed many sophisticated intellectuals and cinephiles. Not every suit is a crass bureaucrat.

Young-ish adult

Patton Oswalt had planned to come to Ebertfest in an earlier year, to accompany Big Fan and to show Kind Hearts and Coronets to an undergrad audience. He had to withdraw, but he showed up this year. On Wednesday night he screened The Taking of Pelham 123 to an enthusiastic campus crowd, and the following night, after getting his Golden Thumb, he talked about Young Adult. (Roger’s review is here.)

As you might expect from someone who has mastered stand-up, writing (the excellent Zombie Spaceship Wasteland), TV acting, and film acting, Oswalt stressed the need for young people to grab every opportunity to work. He enjoys doing stand-up; with no need to adjust to anybody else, it’s “the last fascist post in entertainment.” But he also likes working with other actors in the collaborative milieu of shooting film. He insists on not improvising: “Do all the work before you get on camera.” I was surprised at how quickly Young Adult was shot—one month, no sets. Oswalt explained that one aspect of his character in the film, a guy who customizes peculiar action figures, was based on Sillof, a hobbyist who does the same thing and sells the results. Oswalt talks about Sillof and Roger Ebert here.

As you might expect from someone who has mastered stand-up, writing (the excellent Zombie Spaceship Wasteland), TV acting, and film acting, Oswalt stressed the need for young people to grab every opportunity to work. He enjoys doing stand-up; with no need to adjust to anybody else, it’s “the last fascist post in entertainment.” But he also likes working with other actors in the collaborative milieu of shooting film. He insists on not improvising: “Do all the work before you get on camera.” I was surprised at how quickly Young Adult was shot—one month, no sets. Oswalt explained that one aspect of his character in the film, a guy who customizes peculiar action figures, was based on Sillof, a hobbyist who does the same thing and sells the results. Oswalt talks about Sillof and Roger Ebert here.

It’s common for viewers to notice that Mavis Gary, the malevolent, disturbed main character of Young Adult, doesn’t change or learn. “Anti-arc and anti-growth,” Oswalt called the movie. I found the film intriguing because structurally, it seems to be that rare romantic comedy centered on the antagonist.

Mavis returns to her home town to seduce her old boyfriend, who’s now a happy husband and father. A more conventional plot would be organized around Buddy and his family. In that version we’d share their perspective on the action and we’d see Mavis as a disruptive force menacing their happiness.

What screenwriter Diablo Cody has done, I think, is built the film around what most plots would consider the villain. So it’s not surprising that there’s no change; villains often persist in their wickedness to the point of death. Attaching our viewpoint to the traditional antagonist not only creates new comic possibilities, mostly based on Mavis’s growing desperation and her obliviousness to her social gaffes. The movie comes off as more sour and outrageous than it would if Buddy and Beth had been the center of the plot.

Making us side with the villain also allows Oswalt, as Matt Freehauf, to play a more active role as Mavis’s counselor. In a more traditional film, he’d probably be rewritten to be a friend of Buddy’s. Here he’s the wisecracking voice of sanity, reminding Mavis of her selfishness while still being enough in thrall to high-school values to find her fascinating. As in Shakespearean comedy, though, the spoiler is expelled from the green world that she threatens. It’s just that here, we go in and out of it with her and see that her illusions remain intact. Maybe we also share her sense that the good people can be fairly boring.

All you can eat

There aren’t any villains in Ann Hui’s A Simple Life, a film we first saw in Vancouver back in 2011. Roger had hoped to bring it last year, but Ann couldn’t come, as she was working on her upcoming release, The Golden Era. This year she was free to accompany the film that had a special meaning for Roger at that point in his life.

The quietness of the film is exemplary. It’s an effort to make a drama out of everyday happenings—people working, eating, sharing a home, getting sick, worrying about money, helping friends, and all the other stuff that fills most of our time. The two central characters are, as Roger’s review puts it, “two inward people” who are simple and decent. Yet Ann’s script and direction, and the playing of Deanie Yip Tak-han and Andy Lau Tak-wah, give us a full-length portrait of a relationship in which each depends on the other.

Roger Leung takes Ah-Tao, his amah, or all-purpose servant, pretty much for granted. She feeds him, watches out for his health, cleans the apartment, even packs for his business trips. When he’s not loping to and from his film shoot, he’s impassively chowing down her cooking and staring at the TV. A sudden stroke incapacitates her, and now comes the first surprise. A conventional plot would show her resisting being sent to a nursing home, but she insists on going. Having worked for Roger’s family for sixty years, Ah-Tao can’t accept being waited upon in the apartment. So she moves to a home, where most of the film takes place.

A Simple Life resists the chance to play up dramas in the facility. Thanks to a mixture of amateur actors and non-actors, the film has a documentary quality. It captures in a matter-of-fact way the grim side of the place—slack jaws, staring eyes, pervasive smells. (A small touch: Ah-Tao stuffs tissue into her nostrils when she heads to the toilet.) Mostly, however, we get a sense of the facility’s everyday routines as the seasons change. The dramas are minuscule. Occasionally the old folks snap at one another, and one visitor gets testy with her mother-in-law. One woman dies (in a bit of cinematic trickery, Ann suggests that it’s Ah-Tao), and an old man who keeps borrowing money is revealed to have a bit of a secret. It’s suggested that a pleasant young woman working at the care facility will become Roger’s new amah, but that seems not to happen. The prospect of a romance with her is evoked only to be dispelled.

Ah-Tao’s health crisis has made Roger more self-reliant, but his life has become much emptier. He seems to realize this in a late scene, when he stands in the hospital deciding how to handle Ah-Tao’s final illness. Throughout the film, food has been a multifaceted image of caring, community, friendship, childhood (Roger’s friends recall Ah-Tao cooking for them), and even the afterlife. Ah-Tao and Roger rewrite the Ecclesiastes line about what’s proper to every season by filling in favorite dishes. As he mulls over Ah-Tao’s fate, Roger is, of course, eating. But it’s cheap takeaway noodles and soda pop. This silent scene measures his, and her, loss better than any dialogue could.

The art of American agitprop

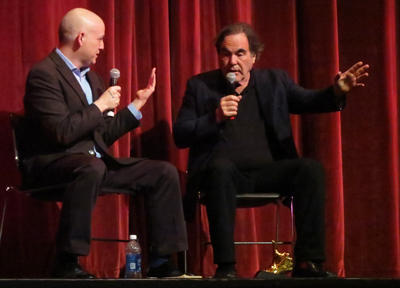

Matt Zoller Seitz and Oliver Stone on stage at the Virginia Theatre.

A Simple Life is a very quiet film. Ebertfest’s highest-profile visitors brought along two of the noisiest movies of 1989. It’s the twenty-fifth anniversary of Do The Right Thing (Roger’s review) and Born on the Fourth of July (Roger’s review), and seen in successive nights they seemed to me to put the “agitation” into agitprop.

During the Q & A, Spike Lee reminded us that some initial reviews of the film (here shown in a gorgeous 35mm print) had warned that the film could arouse racial tensions. Odie Henderson has charted the alarmist tone of many critiques. Lee insisted, as he has for years, that he was asking questions rather than positing solutions. “We wanted the audience to determine who did the right thing.” He added that the film was, at least, true to the tensions of New York at the time, which were–and still are–unresolved.

During the Q & A, Spike Lee reminded us that some initial reviews of the film (here shown in a gorgeous 35mm print) had warned that the film could arouse racial tensions. Odie Henderson has charted the alarmist tone of many critiques. Lee insisted, as he has for years, that he was asking questions rather than positing solutions. “We wanted the audience to determine who did the right thing.” He added that the film was, at least, true to the tensions of New York at the time, which were–and still are–unresolved.

The ending has become the most controversial part of the film. It’s here that Lee was, I think, especially forceful. The crowd in the street is aghast at the killing of Radio Raheem by a ferocious cop, but what really triggers the riot is Mookie’s act of smashing the pizzeria window. I’ve always taken this as Mookie finally choosing sides. He has sat the fence throughout–befriending one of Sal’s sons and quarreling with the other, supporting Sal in some moments but ragging him in others. Now he focuses the issue: Are property rights (Sal’s sovereignty over his business) more important than human life? Moreover, in a crisis, Mookie must ally himself with the people he lives with, not the Italian-Americans who drive in every day. It’s a courageous scene because it risks making viewers, especially white viewers, turn against that charming character, but I can’t imagine the action concluding any other way. Lee had to move the project to Universal from Paramount, where the suits wanted Mookie and Sal to hug at the end.

Staking so much on social allegory, the film sacrifices characterization. Characters tend to stand for social roles and attitudes rather than stand on their own as individuals. The actors’ performances, especially their line readings, keep the roles fresh, though, and the film still looks magnificent. I was struck this time by the extravagance of its visual style. In almost every scene Lee tweaks things pictorially through angles, color saturation, slow-motion, short and long lenses, and the like–extravagant noodlings that may be the filmic equivalent of street graffiti.

By the end, in order to underscore the confrontation of Radio Raheem and Sal, Lee and DP Ernest Dickerson go all out with clashing, steeply canted wide-angle shots. (We’ve seen a few before, but not so many together and usually not so close.) Having dialed things up pretty far, the movie has to go to 10.

In Born on the Fourth of July, Stone more or less starts at 11 and dials up from there. Beginning with boys playing soldier and shifting to an Independence Day parade that for scale and pomp would do justice to V-J Day, the movie announces itself as larger than life. The storyline is pretty straightforward, much simpler than that of Do The Right Thing. A keen young patriot fired up with JFK’s anti-Communist fervor plunges into the savage inferno of Viet Nam. Coming back haunted and paralyzed, Ron Kovic is still a fervent America-firster until he sees college kids pounded by cops during a demonstration. This sets him thinking, and eventually, after finding no solace in the fleshpots of Mexico, he returns to join the anti-war movement.

Even more than Lee, Stone sacrifices characterization and plot density to a larger message. The Kovic character arc suits Cruise, who built his early career on playing overconfident striplings who get whacked by reality. But again characterization is played down in favor of symbolic typicality. While there’s a suggestion that Ron Kovic joins the Marines partly to prove his manhood after losing a crucial wrestling match, the plot also insists that his hectoring mother and community pressure force him to live up to the model of patriotic young America. He becomes an emblem of every young man who went to prove his loyalty to Mom and apple pie.

Likewise, Ron’s almost-girlfriend in high school becomes a college activist and so their reunion–and her indifference to his concern for her–is subsumed to a larger political point. (The hippies forget the vets.) We learn almost nothing about the friend who also goes into service; when they reunite back home, their exchanges consist mostly of more reflections on the awfulness of the war. Later Cruise is betrayed, almost casually, by an activist who turns out to be a narc. But this man is scarcely identified, let alone given motives: he’s there to remind us that the cops planted moles among the movement.

What fills in for characterization is spectacle. I don’t mean vast action; Stone explained that he had quite a limited budget, and crowds were at a premium. Instead, what’s showcased, as in Do The Right Thing, is a dazzling cinematic technique.

Visiting the UW-Madison campus just before coming to Urbana for Ebertfest, Stone offered some filmmaking advice: “Tell it fast, tell it excitingly.” The excitement here comes from slamming whip pans, thunderous sound, various degrees of slow-motion, silhouettes, jerky cuts, Steadicam trailing, handheld shots, all jammed into the wide, wide frame. Every crack is filled with icons and noises–flags, whirring choppers, kids with toy guns, prancing blondes, commentative music. “Soldier Boy” plays on the supermarket Muzak when Ron is telling Donna about his plans.

By the time Ron visits the family of the comrade he accidentally killed, Stone finds another method of visual italicization: the split-focus diopter that creates slightly surreal depth.

Since so many scenes have consisted of a flurry of intensified techniques, simple over-the-shoulder reverse shots might let the excitement level drop. So a new optical device aims to deliver fresh impact in one of the film’s quietest moments.

Like Lee, Stone took the Virginia Theatre audience behind the scenes. He agreed with William Friedkin, who was originally slated to do the film: “This is as close as you’ll every come to Frank Capra.” Instead of using the shuffled time scheme of Kovic’s autobiography, Friedkin advised that “This is good corn. Write it straight through.” Hence the film breaks into distinct chapters, each about half an hour long and sometimes tagged with dates. They operate as blocks measuring phases of Ron’s conversion. Like many filmmakers of his period, Stone deliberately made each chapter pictorially distinct–the low-contrast Life-magazine colors of the opening parade versus the lava-like orange of the beachfront battle.

Stone pointed out that this film marked the beginning of his career as a figure of public controversy. Like Lee, he was attacked from many sides, and from then on he was a lightning rod. Matt Zoller Seitz (who’s preparing a book on Stone) pointed out that at the period, he was astonishingly prolific. From 1986 (Salvador, Platoon) to 1999 (Any Given Sunday), he directed twelve features, about one a year.

Lee was hyperactive as well over the same years, releasing fourteen films. And neither has stopped. Lee’s new film is the Kickstarter-funded Da Sweet Blood of Jesus, while Stone is touring to support the DVD release of his 2012 documentary series, The Untold History of the United States. Both men like to work, and more important, they’re driven by their ideas as well as their feelings. By seeking new ways to agitate us, they impart an inflammatory energy to everything they try. And in giving them a chance to share their insights and intelligence with audiences outside the Cannes-Berlin-Venice circuit, Ebertfest once again demonstrates its uniqueness. Roger would be proud.

The introductions and Q&A sessions for most of the films, as well as the morning panel discussions, have been posted on Ebertfest’s YouTube page. Program notes for each film are online; see this schedule and click on the title.

For historical background on Barry Allen’s work as an editor of syndicated TV prints, see Eric Hoyt’s new book Hollywood Vault: Film Libraries Before Home Video.

P. S. 1 May 2014: Thanks to Ramin S. Khanjani for pointing out that Ramin Bahrani had worked on other films before Man Push Cart. These included one feature he made in Iran, Biganegan (Strangers, 2000); it got only limited play in festivals and apparently a few theaters. I can’t find information about the others online, and presumably they were shorts and/or did not receive distribution. (K.T.)

Ann Hui, with Kristin, gets into the spirit of Ebertfest. David is represented in absentia by the Dots.

You can go home again, and maybe find an old movie

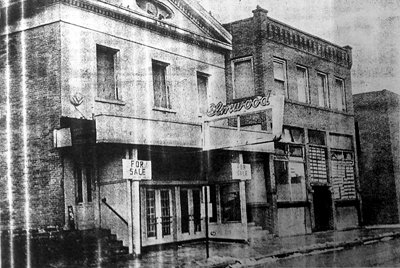

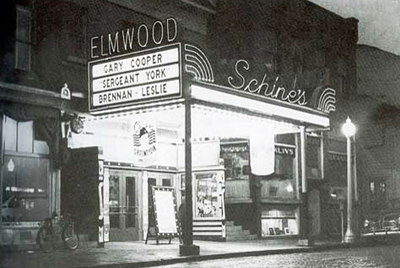

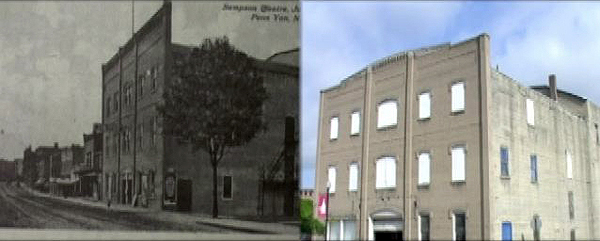

Schine’s Elmwood Theatre, Penn Yan, New York, late 1954-early 1955. Photo courtesy Yates County History Center.

DB here:

Nowadays when a theatre closes or goes digital, it says farewell by screening The Last Picture Show. That hadn’t yet become a tradition when the Elmwood Theatre of Penn Yan, New York presented Bogdanovich’s movie on its final day in November 1972.

Six people showed up.

The Elmwood had been going downhill for years. “I think the theatre building is an eyesore,” declared the chairman of the town’s Urban Renewal Agency. Once part of the powerful Schine circuit, the theatre had been acquired in the mid-1960s by the Rochester-based Panther chain, later renamed Countrywide. That firm seems to have specialized in low-budget genres and X-rated fare. In Penn Yan, the UR officer declared, most of the Elmwood’s programs were rated “restricted,” adding: “Yet it is claimed by some that it is a recreational facility for our children.” Disney films were screened at the Elmwood during those years, but local moviegoer Robert Brainard noted: “They were getting all the junk and nobody was going, not even the kids.”

When the theatre was finally closed, it stood vacant. Vandals broke the windows, and pigeons roosted inside. It had come a long way from the 1940s.

In 1974, two businessmen paid $11,000 for the building and turned it into a racquet club. That business operated for some years, but in 2003 the entire structure was demolished and a new village hall was built on the site.

By then a small three-screen mall cinema had set up business elsewhere in town. I report on a visit here.

In January, I was back in Penn Yan and naturally I sniffed around. Thanks to John H. Potter and Lisa M. Harper of the Yates County History Center, and my sisters Diane and Darlene, I came away with some precious information about the theatre I attended for the first eighteen years of my life.

I also came away with an extremely rare film.

Broadway Melodies and Cherry Blossom Queens

Captain Harry Morse ran steamboat trips on Lake Keuka. He was a legendary figure. Some said that as a boy he had caught a lake trout on his nose. (I know: How could you do that? Supposedly he bent over the side of a boat and a trout leaped up and glommed on.) More prosaically, Morse invested in Penn Yan movie houses, and in 1920 he bought the Shearman House Hotel, a popular stopover for visiting vaudevillians. Morse turned the Shearman House into a theatre.

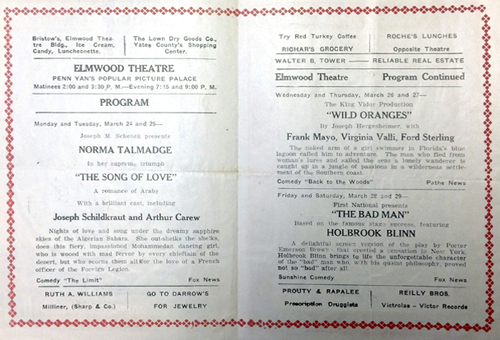

The Elmwood Theatre opened in 1921. It held at least 700 people. That’s pretty big for a town of 4500 people, but as the county seat and a business center, Penn Yan brought in farm families. Many shows were accompanied by printed programs listing coming attractions and carrying advertisements for local businesses. This one, for Song of Love, is from 1923.

Admission was typically 11 cents for matinees and 17 cents for evenings. “Specials” like Chaplin’s The Kid boosted ticket prices to 17 and 28 cents. In 1936 the Schine chain acquired the house.

The Elmwood benefited from the projection expertise of Nathaniel P. “Nat” Sackett. Nat had begun his film career in 1908 at another local movie house, vocalizing with the song slides shown between reels. He became a projectionist before joining the Elmwood in 1923. He stayed on for several decades. According to Nat, The Broadway Melody was the first sound film the Elmwood played. During World War II, he worried that too many theatres were running triple features. If the fad continued, production couldn’t keep up. For Penn Yan, one feature was good enough—especially if it was something like How Green Was My Valley or Captains of the Clouds.

A small-town movie house often became a community center. Elmwood patrons remember talent shows and holiday parties, with gifts and contests before the screenings. In 1940 a housewife attending I Love You Again could join an hour-long cooking class (with prizes) just before the show. Young women would be named Apple Blossom Queen or Cherry Blossom Queen. Halloween screenings included costume contests and of course sudden blackouts and scary sound effects. During the war, with no television or Internet, people flocked to the theatre for newsreels. Customers were steered in and out by ushers; the Elmwood employed them well into the 1950s.

“Today,” remembered Nancy Gillette, “most people cannot imagine a theatre as large as the Elmwood, which included a large balcony, being full most of the time.” By the 1930s, admission prices had come down a bit for children. Ten cents admitted Nancy to the Saturday marathon matinees: “Gene Autry, Hopalong Cassidy, Roy Rogers, Charlie Chan, the newsreel and one or two cartoons—WOW!” Lines of kids stretched down the block. In the 1950s, Diane and I were among them, watching the same cowboy heroes, along with Tarzan and Martin and Lewis.

Romances and marriages were forged at the Elmwood. In 1933, a young man taking tickets let a young woman slip out to retrieve the keys she left in her car. Over the next few days he began to drive by her house. Her cousin knew the young man and said, “Margaret, I am taking you out when Sam comes along, and I’ll stop his car and introduce you to him.” After two years of dating, Margaret and Sam married and eventually had three children. The Elmwood manager gave Sam’s mother and Margaret free passes.

Local kids like Sam found good work at the theatre. Being an usher got you free movies and a chance to flirt with the concession girls and those who came “solo.” After movies there was pizza at the Den below the theatre. But among the ushers’ tasks was the very onerous one of changing the marquee. Jerry Nissen remembered:

First you had to do layout on paper what the marquee was to say. Then, working from the last letter in the last row, fill a heavy wooden box until you get to the first letter of the first row. The solid metal letters were stored in the basement and you hauled them up to the street. Now imagine, if you will, climbing a rickety old step ladder in the rain or snow and taking down the old message and then letter by letter placing the new message on the two-sided marquee. Brrrr, it used to get very cold. Also on occasion we were the targets of some nice vocal comments and snowballs coming from the T & C Tavern across the street.

DIY movies, 1915

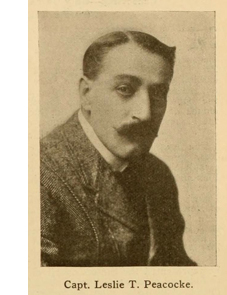

Wheat and Tares (Penn Yan Film Corporation, 1915).

Penn Yan had theatres before the Elmwood went up. In the ‘00s and ‘10s Nat Sackett sang at Theatorum and another theatre, both owned by the Wickham brothers. For a time Nat took over ownership of them. Before Captain Morse built the Elmwood, he was showing movies at the old Sampson legitimate theatre, as well as in the Cornwell, located above a department store. The town apparently had four screens in 1911.

With so many films playing within a couple of blocks, it’s perhaps not surprising that a local businessman decided to make one of his own.

Edward R. Ramsey owned a local paper mill and a factory that manufactured electrical cable. The story goes that when Ramsey observed that Hollywood, California was buying a great deal of his cable, he decided to try moviemaking. Ramsey sold his cable plant and started the Penn Yan Film Corporation.

After making some shorts, Ramsey tied his first feature production to a fund-raising effort by Keuka College. The college’s aim was to provide advanced education to rural students who couldn’t to go to a big university. Ramsey’s film would demonstrate the virtues of going to college. All the talent was local, including the cameraman, who was Ramsey’s brother. From outside, Broadway actor and occasional film director George E. LeSoir was recruited to direct the show.

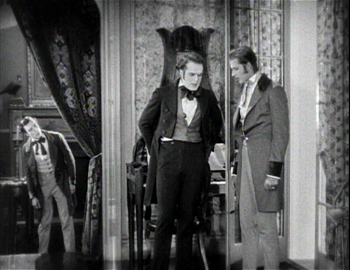

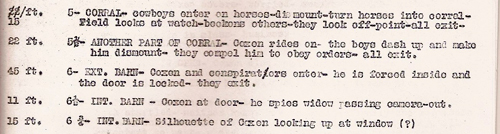

Shot in the summer of 1915, Wheat and Tares traces the story of two young men. Both Jim Watson and Will Beggs read dime novels, but Jim is encouraged by Alice Corwin, daughter of a Penn Yan businessman, to improve himself. Uplifted by literature, Jim leaves the farm for Keuka College. There he learns enough to become an auto salesman. At the same time, Will (who stuck to pulp fiction) falls in with a gang of layabouts and petty crooks. Their fates converge when Jim discovers oil. A crooked realtor hires Will to put Jim out of action long enough for the site option to expire. But Alice renews the option, and Jim’s family becomes rich. Meanwhile, Will’s life of crime catches up with him, and he is sentenced to a prison road gang. Jim and Alice, now married and with a child, stop when they see Will on the road. Jim vows to help his old friend go straight.

Despite its opening-night success at the Sampson playhouse, Wheat and Tares didn’t have legs. Keuka College closed in fall 1915 and didn’t reopen until 1921. Ed Ramsey died in an auto accident in June 1916. The film may have gotten no distribution outside the region. Stored in the Ramsey home, it was discovered decades later when the house was prepared for demolition. The film was transferred to safety stock and eventually to DVD. That’s the version I have seen.

In the moralizing manner of its day, the full title, Wheat and Tares: A Story of Two Boys who Tackle Life on Diverging Lines, contrasts the life paths of its two protagonists. A tare is a form of weed that infects a field of healthy wheat. Tares in their early stages look very much like wheat, so the metaphor implies that one must wait to see if a young man will turn out well or not. (The Biblical reference is a parable by Jesus, at Matthew 13: 34-35.)

The surviving copy of Wheat and Tares has lost its opening reel. What remains is a fairly ordinary 1915 film. The parallel stories of Jim and Will aren’t developed in tandem; we lose Will for most of the film. A great deal of the second reel is occupied with rich boys hazing Jim at college, which does teach him the manly art of self-defense, but to no special point: he doesn’t get to use his boxing skills later. Another undeveloped plot line involves a movie company filming in the vicinity.

Theme and plot don’t match very well. If you are trying to convince people that going to college will better them, why show your hero succeeding by stumbling onto an oil gusher? Jim would have been just as likely to find oil if he had stayed a sodbuster. The climax is particularly feeble: While Jim is recovering from the beating given him by Will and another thug, it’s Alice who saves the day. She does this not through extraordinary courage or sacrifice, but simply by having her father write a check that renews the option. The realtor, a very passive villain, does nothing, underhanded or otherwise, to block her maneuver.

Stylistically, you can hardly expect The Birth of a Nation, The Cheat, or Regeneration from this tiny Finger Lakes company. In most respects, the film resembles standard films of the period. Some filmmakers were exploiting the sort of crosscutting popularized by Griffith, but Ramsey and Le Soir take almost no advantage of it. There’s no fast cutting to pick up the pace. Most scenes are played in single shots, with close-ups used only to emphasize details, such as a deck of cards, that can’t be easily seen in the master framing. The closest shots of the principals occur during a phone conversation–again, a convention of the period.

Nor does the film exploit the sort of complicated staging we find in tableau cinema. There is one rather well-handled crowd shot, as well as a smooth track-in and-out when Will recruits a one-eyed thug to help him ambush Jim. Simple camera movements like this were by 1915 considered a fairly normal option.

There is an ambitious matte effect when Jim and his college chum Phil visit the movies, but even this fairly common device is somewhat bungled when the boys’ bodies become ghostly by crossing into the matte area.

Although Wheat and Tares exemplifies ordinary cinema of that day, like most films of the first great era of cinema it’s a pleasure to watch. Shooting on location yields spontaneous beauties. At one point Jim rides home on the trolley. In a film utterly lacking in calculated lighting effects, we get a lovely image. Not only do we see the town and wagons pass through windows, but after Will and his partner jump aboard, accidents of backlighting turn them into sinister shapes.

Trolley shots are among the glories of 1910s cinema; I don’t think I’ve ever seen a bad one.

Penn Yan must have been gorgeous then, with the main streets lined with elms.

The trees were felled by Dutch elm disease and other factors, I’m told.

As with any film shot in surroundings that you know, part of the fun comes in spotting familiar locales. John Creamer’s introduction juxtaposes some town landmarks. Here’s the Sampson Theatre, then and now.

Two locations that my sisters discovered pop up late in the film. For a chase, the camera was set up just around the corner from Ramsey’s house.

Ramsey’s house was demolished to add a building and a parking lot to the local hospital, but from that vantage point, we found the source of another shot. The camera was apparently set up in front of Ramsey’s home to frame Jim and Alice and their child in their chauffeur-driven Maxwell. The sidewalk in the foreground is gone, but the background area, including the fire hydrant, has stayed surprisingly constant.

And whatever the faults of Wheat and Tares, watching it gives you a glimpse of the entrance to Captain Morse’s Sampson Theatre (below). In the summer of 1915, Charlie Chaplin had sauntered into my home town. The show starts on the sidewalk, as they used to say.

I’m grateful to John and Lisa of the Yates County History Center for all their suggestions, for access to their files, and for the exterior photo up top and the shot of the Elmwood interior. You can read the local newspaper’s announcement of the Wheat and Tares premiere, with a teaser synopsis, here. Thanks also, of course, to Darlene and Diane. The picture of Penn Yan’s town hall was supplied by Darlene, whose photography site is here.

A DVD copy of Wheat and Tares is available for $15 from the Yates County History Center. You can email Lisa M. Harper, ycghs at yatespastdotorg, or call (315) 536-7318. Credit cards accepted.

The indispensable guide to the theatres in this region is Norman O. Keim’s Our Movie Houses: A History of Film and Cinematic Innovation in Central New York (University of Syracuse Press, 2008). You can read about the Schine chain there, or here.

Wheat and Tares is a prime example of an orphan film. Dan Streible of NYU is a moving force behind retrieving and restoring these elusive items, and a new Orphan Film Symposium is coming up in Amsterdam.

Wheat and Tares (1915). The sign on Charlie’s crotch reads” “Meet Me at the Sampson Program.”

The ten best films of … 1923

Le brasier ardent.

Kristin here:

Six years ago David and I celebrated the 90th birthday of the classical Hollywood cinema with a post that included a list of what we considered the ten greatest (surviving) films of 1917. Choosing the ten best films of 90 years ago has become a custom, one which helps us avoid doing a ten-best list for the current year. It’s a way of drawing attention to some wonderful but often little-known films, for those who are interested in exploring the treasures of silent cinema.

For previous entries, click here: 1917, 1918, 1919, 1920, 1921, and 1922.

For some reason, that 1917 list was pretty easy to put together. In recent years, I’ve had more trouble. As I wrote last year, “For the past two years, I’ve noted that it was difficult to fill out the list of ten masterpieces. I keep thinking that I’ll get to a year where I won’t have to say that, but 1922 turns out not to be that year. Some titles were obvious, but the last one or two took some hunting.” Well, 1923 still isn’t that year. I’ve again had some trouble filling out the top ten.

Why? 1923 should be packed with worthy candidates. But oddly, some of the most significant directors of the era didn’t make films that year. This seems to have been partly because success brought greater ambitions. In 1923 Fritz Lang was preparing his epic two-part Die Nibelungen, guaranteed to show up in next year’s list. Abel Gance had embarked the long road to the release of Napoléon, four years later.

Carl Dreyer, who had made three films in 1919 and two each in 1920 and 1921, was bouncing around among companies and countries in the mid-1920s, and didn’t again release anything until his 1924 German-produced film, Michael.

Others made relatively unremarkable films. F. W. Murnau’s surviving film from 1923, Die Finanzen des Grossherzogs, serves mainly to prove that comedy was not his strong suit. Victor Sjöström’s Eld ombord (The Hell Ship) doesn’t match the masterpieces we find elsewhere in his career. Louis Feuillade’s 1923 feature Le Gamin de Paris is likewise unexceptional, though it’s of interest for showing his abandonment of complex staging and his conversion to American-style cutting, including angled shot/reverse-shots. (Of Feuillade’s 1923 installment film Vindicta, we can’t speak; we haven’t been able to see it.)

Other films are lost. John Ford made four films that year, only one of which survives: an incomplete, beat-up version of Cameo Kirby that doesn’t make it look like anything special. Murnau’s first 1923 film, Die Austreibung, seems to be gone. Mauritz Stiller’s The Blizzard is lost, and he, too, was probably already involved in his own 1924 two-part epic, The Saga of Gösta Berling.

[December 29: Brian Darr tweets that The Blizzard is not lost, which I am glad to learn. Its Wikipedia entry confirms that it is only partially lost, with about two-thirds of the film known to be preserved.]

Finally, the Soviet cinema, which was to make such major contributions to 1920s cinema, had not yet gotten off the ground.

Still, with some help from David, I’ve concocted a list with some great films and some near-great ones. The place to start was obvious.

From the ridiculous to the sublime

Some years now we’ve been watching the careers of Charles Chaplin, Harold Lloyd, and Buster Keaton delivering wonderful short films and inching toward even greater things. This was the year they blossomed.

Chaplin made a charming short feature, The Pilgrim, this year, but he also surprised everyone by making a sophisticated sex comedy (appearing only in an unrecognizable cameo as a porter). The title role of A Woman of Paris features Chaplin’s regular leading lady, Edna Purviance, as a village girl, Marie, who loses her young boyfriend Jean through a misunderstanding. She runs off to the city to become a rich man’s mistress and realizes too late what she has lost.

The plot centers largely around this romantic triangle and Marie’s indecision about whether to return to her boyfriend, who has become an impoverished artist in Paris, or to stay in the luxurious life that Pierre provides her. The affair between Marie and Pierre is handled in a sophisticated and yet subtle way. There are no love scenes, but at one point Pierre finds himself without a handkerchief and goes into the bedroom to pluck one casually out of drawer. Clearly he spends a lot of time in their love nest.

At the same time, the film deals more generally with the gulf between the very wealthy and the working-class people who who serve them. In one well-known scene, a woman gives Marie a massage, and the camera stays mainly on the masseuse as she tries to maintain a neutral expression while obviously being shocked by the lurid gossip between Marie and a friend. In another, a kitchen assistant in a swanky restaurant cannot bear the odor of the aging game bird he has to fetch for the chef, but the chef and Pierre consider it a prime delicacy.

At the same time, the film deals more generally with the gulf between the very wealthy and the working-class people who who serve them. In one well-known scene, a woman gives Marie a massage, and the camera stays mainly on the masseuse as she tries to maintain a neutral expression while obviously being shocked by the lurid gossip between Marie and a friend. In another, a kitchen assistant in a swanky restaurant cannot bear the odor of the aging game bird he has to fetch for the chef, but the chef and Pierre consider it a prime delicacy.

One of the strengths of the film is that it does not take the obvious approach of making Pierre into a fat, obnoxious oaf. On the contrary, Adolphe Menjou plays him as a witty, unflappable figure. He thinks nothing of arranging a marriage with a rich woman while planning to carry on his affair with Marie, but he puts up with her shifting moods and does genuinely seem to love her. The touch of having him play his saxophone while Marie has a tantrum and orders him out (right) typifies the light touch Chaplin applies to what is ultimately a tragic story.

A Woman of Paris was not well received upon its release, at least by the ticket-buying public, who expected a Chaplin film to star the Little Tramp and to be straightforwardly funny. The title at the beginning, where Chaplin explains that he does not appear in the film undoubtedly did little to appease them. Many critics were respectful, however, and other filmmakers recognized the new type of sophisticated comedy that he had introduced. Lubitsch, who was working on Rosita at the same studio, United Artists, was definitely influenced by it–as we shall see next year when his The Marriage Circle figures in the top ten of 1924. That film includes Menjou, playing a similar role, and in fact after playing minor roles for nearly ten years, he became a star with Chaplin’s film.

[February 10, 2014: Paul Duncan, Film Book Editor for Taschen, has kindly supplied figures showing that A Woman of Paris was profitable, if not as much as Chaplin’s other films: “It earned United Artists $634,000, of which $608,868.91 went to Regent Film (the company Chaplin formed to produce films for Edna Purviance). So with a production cost of $351,853.03, A Woman of Paris made a healthy profit, though, as you write, obviously it would have been more if it had been a comedy starring Chaplin.” Paul also informs me that Taschen’s The Charlie Chaplin Archives, which he is editing, will be published later this year.]

By 1923, Harold Lloyd had already done some shorts featuring nail-biting but hilarious comedy high up on skyscrapers. (See High and Dizzy in our 1920 entry.) In 1923 he took the same sort of premise into the feature-length Safety Last and created an indelible image: a brash young man hanging from a tilting clock. The gags go on story by story. After surviving the clock, Harold manages to get to the next level, only to be chased out a flagpole by a dog (left). Looking back, people tend to remember the vertiginous climb as the whole film, though remarkably, it takes place only over the last third. Earlier scenes involve a romance and misunderstandings that arise from the hero’s job at a department store.

By 1923, Harold Lloyd had already done some shorts featuring nail-biting but hilarious comedy high up on skyscrapers. (See High and Dizzy in our 1920 entry.) In 1923 he took the same sort of premise into the feature-length Safety Last and created an indelible image: a brash young man hanging from a tilting clock. The gags go on story by story. After surviving the clock, Harold manages to get to the next level, only to be chased out a flagpole by a dog (left). Looking back, people tend to remember the vertiginous climb as the whole film, though remarkably, it takes place only over the last third. Earlier scenes involve a romance and misunderstandings that arise from the hero’s job at a department store.

Safety Last wasn’t Lloyd’s greatest film, but it launched the greatest period of his career. He’ll probably be joining us for these nostalgic lists every year now until 1927. The film is still available as part of New Line’s big box set of Lloyd’s films on DVD. (Buy that one, and you’ll be a step ahead of those future lists.) This summer the Criterion Collection brought Safety Last out on DVD and Blu-ray. There’s only that one feature on the disc, but it includes several supplements, including three newly restored Lloyd shorts and Kevin Brownlow’s 104-minute documentary, The Third Genius.

Keaton, too, entered a hugely creative streak in 1923. He made an amusing satire on Intolerance, the feature-length The Three Ages, in which Buster traces love through the stone age, the Roman era, and the Roaring Twenties. As Keaton himself acknowledged, “Cut the film apart and then splice up the three periods, and you will have three complete two-reel films.” He followed it up, however, with a masterpiece that displayed a complete command of story structure in the classical Hollywood mold: Our Hospitality. It’s arguably as fine as anything he ever made, except The General, which just edges it out.

Interestingly, Our Hospitality and The General are Keaton’s only two period pieces. (that is, if one excepts The Three Ages, which is far more farcical and does not attempt to recreate a realistic period atmosphere.) Both also take place in the South, and outdoors to a considerable extent. The milieu seems to have inspired him. Dealing with old-fashioned trains and other technology generated a lot of clever gags, and the fields, forests, and rivers helped give these two films a pictorial beauty that separates them from the Keaton’s other films.

Way back in 1978, when David and I were working on the first edition of Film Art: An Introduction, we wanted to include an extended analysis of a single film in each of the chapters on film technique. For mise-en-scene we chose Our Hospitality, which contains numerous uses of setting, costume, acting, and lighting brilliant enough to inspire a teacher and straightforward enough for students to notice and understand. Plus what better way to win over students who think that old black-and-white silent movies aren’t worth watching?

The story is simple. Willie McKay, the hero, travels from New York to the deep South, under the impression that he has inherited a mansion. The trip south on a very old-fashioned train supplies a long string of marvelous sight gags. There Willie meets the heroine, who shares his coach. Upon arrival, Willie discovers that his “mansion” is really a decaying house. Since the heroine has invited Willie to dinner, he wanders around to pass the time, unaware that he has inherited something else: a feud. The heroine’s family has a longstanding grudge against the McKays, and the father and two brothers are determined to shoot Willie. The only catch is that Southern hospitality dictates that they cannot kill him while he’s in their home.

In our analysis in Film Art, we pointed to the many motifs Keaton uses in service of the narrative, such as the moment of the hero’s rescue of the heroine as an echo of the earlier fishing pole/waterfall gag. One stylistic motif of staging comes back several times: Keaton using foreground doors or walls to create depth staging of moments when people spy or eavesdrop on others. In the frame on the left below, one of the brothers waits to ambush Willie, who is unaware of his presence (or indeed of the feud itself). In the one on the right, Willie eavesdrops on the brothers in their house, learning that they intend to kill him but that he is safe inside the house. Now Willie learns what’s going on, while the brothers don’t realize that he’s overhearing their plan. Such compositions are a motif in the film, forming a way of manipulating the narration–usually giving us more information than the characters onscreen have.

Like Safety Last, Our Hospitality ushered in the prime of the comedian’s career. Keaton made a string of marvelous features that lasted until The Cameraman in 1928. He didn’t always sign the films as director (he’s listed as co-director of Our Hospitality, along with John Blystone), but his unerring sense of how to compose images for the entire frame, both its surface composition and in depth, suffuses all his films of this period.

I’ve mentioned that Lubitsch was working at United Artists in 1923. Rosita was his first American film, starring Mary Pickford. It’s certainly not a masterpiece on the level of The Marriage Circle or Lady Windermere’s Fan, but Rosita is a charming and impressive film, certainly at least as good as Lubitsch’s other lesser films of the decade, Forbidden Paradise and Three Women.

As I discuss in my book, Herr Lubitsch Goes to Hollywood, the director had already been tentatively using classical Hollywood style in his last two German films, Das Weib des Pharao and Die Flamme. In Rosita, he managed to balance a typical historical epic from his German period (Madame Dubarry, Anna Boleyn) with the light, vivacious appeal of his star. She plays the title character, a cheerful street musician who is in love with Don Diego, an impoverished nobleman and military officer. Rosita catches the eye of the lecherous king. Don Diego ends up condemned to death, and Rosita plots to save him.

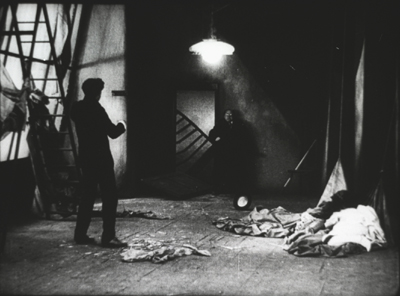

The sets were built on the enormous backlot of United Artists, where Douglas Fairbanks’ castle for Robin Hood had stood. The day after Rosita wrapped, the construction of the sets for The Thief of Bagdad began on the same lot. Indeed, one can detect a distinct similarity between Rosita’s big sets–city streets and a large prison–and those of the two Fairbanks films. This frame is a shot of the prison interior emphasizing a gallows in the background:

Given that this giant set was built in the open air, Lubitsch must have filmed this and other scenes at night, using the giant arc spotlights that had recently become a standard tool of Hollywood filmmaking to throw great swathes of illumination across the scene. In general, Rosita‘s style demonstrates that by 1923, Lubitsch had come fully to understand the American approach.

As a vehicle for Pickford, the film also is skillfully done, permitting her numerous intimate scenes that show off her charm. Given her star persona, the dramatic situation is leavened with humor in the interior scenes. Rosita’s poor family, a large, rowdy bunch, provides much of this, as when Rosita brings home a perfumed handkerchief and the impressed parents and children in turn bury their noses in it and sniff deeply. Rosita’s reactions to the King’s attempts to seduce her are also somewhat comic, though there is definitely a threat hanging over the situation.

Unfortunately, like all too many of the films on this year’s list, Rosita is difficult to see. It seems to have survived only in a Russian print, and a rather contrasty, worn one at that, as the frame above demonstrates. As long as that is the sole available material, a restoration might be too daunting. Still, in this day of digital manipulation, perhaps something could be done to improve the image quality. I hope at some point it will become available on home video. That also goes for Lubitsch’s other somewhat lesser films of the mid-1920s, Forbidden Paradise and Three Women.

Rosita’s reputation has suffered from strange statements Pickford much later made to Kevin Brownlow and which he published in The Parade’s Gone By. There she claims she and Lubitsch did not get along and that the resulting film was bad and a commercial failure. With the film itself unavailable for viewing, Pickford’s condemnation was accepted at face value. In fact, documents in the United Artists archive at the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research overturn Pickford’s supposed dislike for Lubitsch. For years she tried to find financing to make another film with him, and in 1926 she called upon him for help in editing Sparrows. With the discovery of the Soviet print, it becomes apparent that Rosita was far from the disaster Pickford later claimed. Why her memories of her work with Lubitsch became so distorted late in her life we shall probably never know.

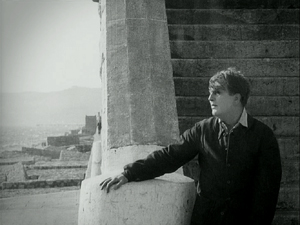

Overshadowed masters of French Impressionism

Abel Gance’s flashy La roue (on last year’s list) gets a lot of attention these days. He’s the high-profile representative of Impressionism. Yet 1923 saw the first fiction films from the director who was the movement’s modest heart: Jean Epstein. The very first, L’auberge rouge (“The Red Inn”) is a lovely film, but Cœur fidèle (“Faithful Heart”) epitomizes the quiet side of Impressionism. It’s story is as simple as they get: Marie is a barmaid whose foster parents try to force her to marry a thug, Petit Paul, while she is in love with the sensitive dock-worker Jean. The scenes around the waterside and the famous sequence in a carnival are all done with a realism blended with the subjective camera techniques that convey the characters’ thoughts, perceptions, and feelings in a way that was fresh at the time.

The exteriors were shot around the docks of Marseille, and Epstein uses superimpositions of the ocean to convey the lovers’ longing. Waves are sometimes superimposed over their figures, or one will look into the water and see the other’s face there, as when Jean envisions multiple images of Marie:

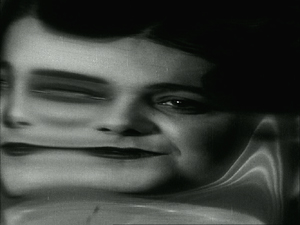

Shooting into a distorting mirror, Epstein uses the conventional Impressionist indicator of drunkenness as Petit Paul looks at a woman next to him in a bar:

Coeur fidèle has been released in the UK (Region 2) as a DVD/Blu-ray combo in Eureka!’s Masters of Cinema series. (This includes a helpful little booklet with excerpt from Epstein’s writings and a review of Cœur fidèle by René Clair.) It is also available as a Region 2 French DVD without English subtitles. As these frames indicate, the film survives in beautiful condition.

Along with La roue, Cœur fidèle proved hugely influential. It used the “unfastened camera” that later was credited to Murnau in The Last Laugh. Like Murnau, Hitchcock picked up Impressionist style, as reflected most obviously in his 1927 boxing film, The Ring. Hitchcock’s penchant for moving camera and subjectivity never went away. Hollywood, too, picked up the subjective techniques of Impressionism, especially in the 1940s films that David is studying now.

Unlike Cœur fidèle, Le brasier ardent (“The Burning Crucible”) was sophisticated, convoluted, and perplexing. It was one of two films directed in France by the Russian actor Ivan Mosjoukine for the émigré film company Albatros. (The earlier one is L’Enfant du carnaval, 1921; as far as I know, no print survives.) Earlier this year, upon the release of Flicker Alley’s box set of five Albatros films, I described Le brasier ardent:

It has a reputation as an audacious, surrealist, and almost incomprehensible film. This may be due to the fact that prints available in archives during the 1970s and 1980s lacked intertitles. The opening nightmare sequence is indeed disturbing, but at least with intertitles, we understand that it is only a dream. It begins with a wild-eyed man tied to a stake where he is about to be burned. The heroine stands looking on, resisting as the man pulls on her long hair, apparently intent on dragging her into the fatal flames to accompany him in death. Subsequent scenes of the nightmare show the heroine encountering different men, all played by Mosjoukine, culminating in a man in evening dress stalking her along a vaguely Expressionist street until she escapes and wakes up in bed.

This nightmarish opening must have established vivid expectations in the spectators of 1923 as to what sort of film they were in for. After the heroine wakes up, however, what follows is quite different. The main plot is a stylized but quite amusing comedy. The heroine is a pampered wife, married to a rich man whom she does not love. She is faithful, but he is unreasonably jealous. He goes to a distinctly odd detective agency, one department of which is “Recovery of Lost Wives” (above), with “Success guaranteed!” and “Nothing to pay in advance!” Juxtaposed with the bizarre opening, this quirky humor might have eluded puzzled audiences of the day. Certainly the film itself was a failure, and Mosjoukine stuck to acting thereafter.

Unfortunately for the husband, Detective Z, whom he picks from the eccentric group pictured above, is the very man, again played by Mosjoukine, whom his wife has dreamed about. What follows is an odd tale with the detective and wife gradually falling love. Mosjoukine, known for his tragic, intense characters in the Russian cinema, plays such figures in the fantasy sequences–but in the main story he is allowed to play for laughs, gamboling and rolling on the floor like a puppy when the wife finally appears at his mother’s apartment and declares her love for him.

Mosjoukine should not, however, be allowed to overshadow his co-stars, Ermolieff actors who were also were to make their way into the wider French production of the day, including Impressionism. The wife is played by Nathalie Lissenko, one of the stars of the pre-Revolutionary cinema, who had acted opposite Mosjoukine in Russia. Among her 1920s roles was the protagonist of one of Epstein’s finest films, the largely unknown L’Affiche (1924). The husband is Nicolas Koline, who started his career with Ermolieff only after the company had left the Soviet Union. He will be familiar to silent-film fans from his performance as Tristan Fleury in Gance’s Napoléon.

By this point, stylistic influences were beginning to pass back and forth between France and Germany. Le brasier ardent shows distinct touches of Expressionism in its decor, as when the heroine flees through a distorted door. (See top.)

I have to admit that the third Impressionist film on our top-ten list, Germaine Dulac’s La souriante Madame Beudet (The Smiling Madame Beudet) is not one of my favorites. It hasn’t got much of a plot. A sensitive woman in a provincial town finds her husband crass and unpleasant until a final crisis brings them–at least temporarily–together. It’s not so much the simplicity of the story, however, as the rather heavy-handed use of subjective camera tricks to convey Mme. Beudet’s thoughts about her husband, as when a distorting mirror conveys her grotesque view of him (at right).

I have to admit that the third Impressionist film on our top-ten list, Germaine Dulac’s La souriante Madame Beudet (The Smiling Madame Beudet) is not one of my favorites. It hasn’t got much of a plot. A sensitive woman in a provincial town finds her husband crass and unpleasant until a final crisis brings them–at least temporarily–together. It’s not so much the simplicity of the story, however, as the rather heavy-handed use of subjective camera tricks to convey Mme. Beudet’s thoughts about her husband, as when a distorting mirror conveys her grotesque view of him (at right).

We’ve just seen a similar distortion in Cœur fidèle, above, to show a drunkard’s point of view. In Marcel L’Herbier’s El Dorado, from 1921, another distorted-mirror close-up suggests drunkenness without using a character’s point of view (see Film History: An Introduction, 3rd edition, p. 79).

The film has decided virtues, such as the lovely shots of the small provincial town in which the film’s exteriors were made, as well as the genuinely surprising and touching ending, which pulls back somewhat from the simplistic characterization of M. Beudet.

As with some of our choices from previous years, The Smiling Madame Beudet goes on the list partly because of its historical importance. Dulac was one of the early women directors to make a career in the cinema. Back in the days of 16mm, prints of this film were among the few Impressionist classics available for film club and classroom use, and the film became a staple in feminist-film courses.

Ironically, nowadays teaching the film is more difficult. Oddly enough, none of the mainstream labels has brought out a DVD with English subtitles. A German DVD, which includes two other short Dulac films, Invitation au voyage (1927) and the surrealist classic La coquille et le clergyman (1928), is available. The copy on this DVD is probably the same as the fairly good-quality Swiss archive print on YouTube, with bilingual French and German intertitles. For anyone with even an elementary knowledge of either language, the titles are not very challenging.

Caligarisme spreads

Caligarisme was the French word for cinematic Expressionism, which, as the example from Le brasier ardent shows, fascinating many French filmmakers.

Despite the lack of major contributions from Murnau and Lang, in 1923 the country’s cinema was going strong. Several films that fall slightly short of being masterpieces appeared. By this point the Expressionist film movement was well established, having begun in 1920 with Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari. Some of its greatest films–Der müde Tod, Nosferatu and Dr. Mabuse der Spieler–had already appeared.

Three very good Expressionist films came out in 1923: Erdgeist (“Earth Spirit,” directed by Leopold Jessner), Schatten (“Shadows,” released abroad as Warning Shadows; Arthur Robison), and Raskolnikow (adapted from Crime and Punishment; Robert Wiene).

It’s really a toss-up as to which film should represent Expressionism on this year’s list. I give the edge to Erdgeist, largely because it and Von Morgens bis Mitternachts (“From Morn to Midnight”) are the two films from the movement that push the style the furthest. They come the closest to Expressionism as it existed in drama and the other arts. Most Expressionist cinema “tamed” the style a bit by applying it to genre tales: horror (Caligari, Nosferatu), fantasy (Der müde Tod), historical myth (Die Nibelungen), and science fiction (Algol, Metropolis). These two films, in contrast, depended on dramas where elemental human passions are released and taken to extremes, with the costumes, decor, makeup, and acting reflecting the characters’ inner states.

The film was based on the first of the two “Lulu” plays by Frank Wedekind: Erdgeist (1895) and its sequel Die Büchse der Pandora (Pandora’s Box, 1904). G. W. Pabst’s much better-known Pandora’s Box (1929) combines the two plays, which tell a continuous story about an amoral young woman who lives by exploiting wealthy men but drives them to extreme jealousy by flirting with other men.

In Pabst’s film, Louise Brooks plays Lulu as a vivacious young woman, seemingly unaware of her disastrous effect on the men around her. Asta Nielsen plays the character in Jessner’s film as a ruthless, mature woman. The plot concerns Dr. Schön, a rich man who found Lulu on the streets when she was a child and has raised her with the intent of having her become his mistress. At the beginning, she is married to Dr. Goll but immediately begins seducing Schwartz, an artist hired to paint her portrait. In the image below, Goll bursts in on them in Schwartz’s studio and Lulu collapses at the right. The distorted stairway, the streaks of light painted on the set, and the jagged shadows all create the Expressionist look–as does the eerie blank glow of Goll’s glasses.

The acting is exaggerated and unnatural. Nielsen, foregoing all glamor, frequently holds a grimace on her face to the point where she almost looks like she is wearing a mask. In an early scene Goll moves his cane about, and she dances like a marionette attached to it by strings. (Puppet-like acting was a convention of Expressionist drama.)

Overall, the style is so grotesque and the characters so unpleasant as to make it clear why Erdgeist is one of the least remembered of the major Expressionist films. It is not available on home video. The print I saw about 16 years ago had Dutch intertitles and was somewhat dark. Perhaps, like Von Morgens bis Mitternachts, it will eventually be restored and released on DVD.

Two Expressionist films deserve brief mention as well.