Archive for the 'Silent film' Category

How to watch FANTÔMAS, and why

DB here:

He is, we’re told in the opening of the first volume, “The Genius of Crime.” Not a genius, the genius. And he doesn’t play nice.

“Fantômas.”

“What did you say?”

“I said: Fantômas.”

“And what does that mean?”

“Nothing. . . . Everything!”

“But what is it?”

“Nobody. . . . And yet it is somebody!”

“And what does the somebody do?”

“Spread terror!”

In the standard English translation, the last line sounds exceptionally scary, especially today. The original French, “Il fait peur,” is closer to “He creates fear,” but that sounds tamer in English than in French.

In whatever language, for a hundred years this catechism has proven bone-chilling. Cinephiles, crime fans, avant-garde artists, and mass audiences have found the tales anxiety-provoking, even hallucinatory. The delirious imagery and plot twists are felt to harbor a demented poetry. So the first reason to celebrate the arrival of a U. S. DVD version of Louis Feuillade’s great installment-film Fantômas (1913-1914) is that we can all have a look at what made Apollinaire and Magritte and Resnais and Robert Desnos tremble.

I confess myself of the other party. I enjoy tales of Fantômas and Dr. Gar-el-Hama (the Danish equivalent in movies of the era) and Dr. Mabuse and Haghi (of Lang’s magnificent Spione, 1928) but they don’t give me an existential frisson, or unmoor me from rationality, or make me feel the secret currents swirling through the modern city. Call me cold-blooded.

On second thought, don’t. The best-made efforts in the master-mind genre do heat my blood—but because they arouse my love of narrative invention and dazzle me with flourishes of cinematic style. The conventions of the genre, all the disguises and elaborate schemes and surprising revelations engineered by the Genius behind the scenes, the cascades of coincidence and the hairbreadth escapes, aren’t merely enjoyable in themselves. They show how little plausibility matters to storytelling. (People may say they like realism, but they’re suckers for far-fetched stories.) And in order to make the whole farrago of traps and conspiracies flow along, you need filmmakers who can hold our interest with swift pacing and ingenious narration. On many occasions, depicting virtuosity of crime has called forth virtuoso cinematic technique.

So let Fantômas make your flesh creep, if your flesh is creepward inclined. But even if it’s not, we should celebrate Louis Feuillade’s triumph in creating, in the first great era of filmmaking 1908-1918, a fine piece of cinematic storytelling. To appreciate it, we need to watch—really watch—what he’s doing.

So let Fantômas make your flesh creep, if your flesh is creepward inclined. But even if it’s not, we should celebrate Louis Feuillade’s triumph in creating, in the first great era of filmmaking 1908-1918, a fine piece of cinematic storytelling. To appreciate it, we need to watch—really watch—what he’s doing.

Thirty-two Fantômas novels by Marcel Allain and Pierre Souvestre were published from 1911 through 1913. By the time Feuillade launched the film version in May of 1913, the book cycle was winding down; in La Fin du Fantômas (1913), the master criminal dies, at least for a while. Souvestre died in 1914, but the prodigious Allain revived the series and the villain during the 1920s.

When the films were made, Feuillade was working for Gaumont, one of the two most powerful French studios. He was head of production, overseeing other directors while turning out his own movies at a rapid clip. He signed over fifty films, mostly one-reel shorts, in 1913 alone. The Fantômas films are often thought of as a serial, but they are really long installments in a series, somewhat like our Bond and Bourne franchises. A “feature” film at the period might run fifty to seventy-five minutes. As with our franchises, there are recurring characters. The films pit police inspector Juve and the journalist Fandor against Fantômas and his accomplices, notably the treacherous but passionate Lady Beltham.

Feuillade was one of the great directors. He had a fine comic touch, not only in the shorts featuring child players like Bébé and Bout de Zan but also in farcical two-reelers like Les Millions de la bonne (The Maid’s Millions, 1913). His dramas could be powerful too, epitomized for me in the two-part feature Vendemiaire (1919) and sentimental melodramas like Les Deux Gamines (1921) and Parisette (1922). Still, he’ll probably always be most famous for his crime films like Les Vampires (1915-1916), Judex (1917), Tih Minh (1919), and of course the first of them, Fantômas.

The new video edition, which comes to us from Kino, is the third DVD release I’ve seen. The first was a French set from Gaumont in 1998, the first full year of the DVD format. The box contains a handsome booklet with background material, pictures, and an interview with Feuillade, but the intertitles aren’t translated. All subsequent releases seem to be based on the Gaumont copy used in this collection. That results in so-so picture quality, a rather haphazard score pasted together from classical pieces, and occasional distracting sounds, like birds tweeting in outdoor scenes. The UK Artificial Eye PAL release of 2006 includes a brief introduction by Kim Newman but no booklet. The original Gaumont titles are preserved, with English subtitles added.

Kino’s version unfortunately eliminates the French titles altogether, substituting English translations. Visually, however, I prefer the Kino version to the others, which on my monitors is less contrasty and heavily saturated in its tinting. Still, the Gaumont master was made in the early days of DVD authoring and could stand a complete redo. In fact, Gaumont should release many more Feuillade titles, starting of course with Tih Minh.

How best to persuade you that these movies are worth watching? I decided to concentrate on just the first episode, Fantômas (aka The Shadow of the Guillotine) as a sample of Feuillade’s artistry. Everything I analyze here is on display in later installments, sometimes more flamboyantly. The creative principles at work are explored in greater detail in my books On the History of Film Style and Figures Traced in Light (which has a long chapter on Feuillade), as well as in several items on this site.

1. Get ready for preposterousness. The film, based on the first book in the series, rearranges the novel’s plot order considerably and simply excises the first half’s major line of action, a hideous murder. Even with cuts, though, the film asks us to believe that after Fantômas, disguised as one Gurn, is put into prison, he can get his wealthy mistress to bribe a guard to let him out for a while. And that during their rendezvous, the couple can replace the murderer with an actor who happens to be playing Gurn in a stage show based on the case. And that the actor, having been drugged, can’t recall his identity.

There’s at least one glaring plot gap in the film. Juve solves the mystery of the disappearance of Lord Beltham when he discovers his body in a steamer trunk about to be sent overseas. The novel explains his rather tenuous line of reasoning (Chapter 11), but the film simply shows him arriving at Gurn’s apartment and examining the fatal trunk. Presumably, though, Feuillade could afford to be elliptical. Some of the audience would have known the novels and could fill in bits that seem enigmatic to us.

The film’s climax is in fact less implausible than the novel’s, perhaps out of considerations of good taste. In the novel, the actor substituted for Gurn actually dies at the guillotine; the authorities realize their mistake only when they see the head smeared with greasepaint. In the film, Juve interrogates the dazed Valgrand and astounds other officials by revealing that he isn’t the prisoner they had locked up. Even then, it seems unlikely that nobody but Juve would have noticed the prisoner’s wig and false mustache.

Far-fetchedness is built into the genre, so the problem is handling. Craziness must be treated matter-of-factly, and Feuillade’s sober technique takes all the wild developments in its stride. Nothing fazes Fantômas, or our director.

2. Accept the conventions of “pre-classical” cinema. Film historians often consider the years from 1907 to 1917 as leading up to the sort of cinematic storytelling we know, replete with lots of cutting, close-ups, and camera movements. A film like Fantômas exemplifies some tendencies of French cinema in this period. There is relatively little crosscutting among lines of action. The film uses no shot/ reverse-shot or extended passages of close-ups. Typically a cut is used to enlarge printed matter, like a news story or a business card, or to emphasize crucial details. Here is Juve discovering a clue, Gurn’s hat, in Lady Beltham’s parlor.

Interior sets were usually designed to be seen from only one camera orientation. In exteriors, we get somewhat freer cutting, presumably because real surroundings don’t confine the camera as much as a fake set does.

In this transitional era, some habits of earlier years hang on: the fairly distant framings, the fairly obvious sets, and the occasional glances at the audience.

You can almost sense stylistic change happening during such moments. In earlier films, characters constantly looked at the audience, but in Fantômas a character’s eyes pause fractionally on us before drifting away, as if the look to the camera simply signified thinking, not an effort to share a response.

Similarly, Feuillade seems to be sensing the need for varying his camera positions in a way that we’d find in later cinema. Consider his handling of the Royal-Palace Hotel.

To show the elevator entry on different floors he reuses the same set. This is motivated realistically, since hotels look more or less the same on different floors. But if the camera were framing every elevator shot exactly the same way, we would have weird jump cuts when cutting from floor to floor, and the use of the same set would be more apparent. So Feuillade not only re-labels each landing at the top of the frame, but he shifts his camera position slightly, moving the framing rightward in the string of shots showing the elevator descending to the ground floor.

The slight shifts in framing reinforce the sense that we’re on different floors.

3. Watch the back door. Deep space is common in exteriors from the beginning of cinema, even in Lumière shorts, but by the early 1910s filmmakers were starting to replace relatively flat interior sets with ones that give their actors more playing space in depth. Here, for example, is a Bohemian party from Feuillade’s Une Nuit agitée of 1908. The parlor and the action are shot in a flat, lateral way, and people enter the room from the right or left.

Compare the depth in the interiors of many scenes in Fantômas of five years later.

Once sets become deeper, the rear door becomes very handy for entrances and exits, and Feuillade is a master of using it. It’s usually fairly close to the center, but in the actor Valgrand’s dressing room, it’s off to the side.

The rear door prepares us for upcoming action and provides another center of compositional interest—advantages that don’t come up when actors enter from the sides of the frame. The door also allows people to be shown overhearing what is going on in the foreground.

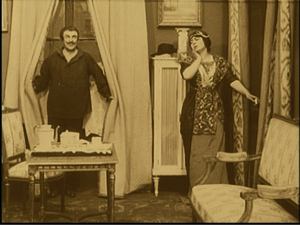

4. It isn’t theatre! There’s a common belief that the cinema of this period simply records performances as if on a stage. But that’s not true. As most of these shots show, the camera is usually closer than any spectator would be to a stage play. Feuillade reminds us of what a real stage performance would look like when Lady Beltham sees the actor Valgrand in the dramatization of Gurn’s capture. (It’s reminiscent of the stage-like set in Une Nuit agitée above.)

Valgrand’s gestures are broad ones, suitable to being seen from a great distance. But in the surrounding story, the performances are much more subdued. Feuillade demanded dry, quick acting from his players, and their gestures aren’t extravagant. (Juve usually jams his hands in his overcoat pockets.) Instead, Feuillade keeps his actors busy with small props. Here, as Fandor writes a story, Juve is brooding on his failure to capture his adversary. Before he’s finished one cigarette he’s already rolling another, and he lights up the new one end to end.

Crucially, theatrical space is geometrically very different from cinematic space, as I’ve argued in several other entries. A shot like this wouldn’t work onstage because spectators sitting to the right or the left would have their sightlines blocked by furniture.

Because the camera slices out a wedge of space in depth, actors can be carefully arranged in dynamically developing compositions that would not be visible on the stage. When the doped-up Valgrand is brought to be questioned by the police officials, we first see him through the rear doorway–a view that wouldn’t be shared by many spectators in a theatre performance.

The dazed actor is questioned, with Juve emerging slowly out of the welter of authorities behind him.

Needless to say, the earliest phases of this shot would be unintelligible on a stage; for most members of the audience, the other actors would block Juve. Recall as well that this was accomplished in an era when directors and cinematographers could not look through the lens to see exactly how the configuration would appear onscreen.

5. Develop an appreciation of complex staging. In a cinema relying on analytical editing, our attention is driven to one item or another through cutting and closer views. By contrast, the director of “tableau cinema,” as this 1910s style is sometimes called, must shift the actors around the sets in ways that call our attention to what’s important at each moment. In the course of the scene, the director must also try to maintain some pictorial harmony on the two-dimensional plane of the screen. Shots are subtly balanced, then unbalanced, then rebalanced, all in the service of story intelligibility.

As we’d expect, depth can play a key role here. Take the simple moment when Lady Beltham’s butler announces the arrival of Nibet, the prison guard whom she bribes. Lady Beltham turns at the sound, rises, and moves to the settee.

As Nibet enters, Lady Beltham returns to her writing desk. This is our old friend the Cross, refreshing the image by having the actors trade placement in the frame.

The same choreography of balancing, unbalancing, and rebalancing can be found when the characters aren’t arranged in depth. The scene of Lady Beltham and Gurn drugging Valgrand plays out laterally. Gurn hides behind a curtain, and our awareness of his presence there colors the whole scene. But because Valgrand will be on the settee, for some while Lady Beltham’s position at her tea table would make an appearance by Gurn compositionally clumsy.

As the drug takes effect, Lady Beltham moves to Valgrand’s side. This gesture of concern unbalances the composition–until Gurn peeps out to rebalance it.

Lady Beltham’s stare at him makes sure we notice his presence. Soon the police arrive to return “Gurn” to his cell.

Again Lady Beltham moves to the right, and again it’s motivated: She wants to make sure the cops have gone. But that movement clears a space for Gurn, i.e. Fantômas, to reveal himself in triumph just as Lady Beltham relaxes in relief.

The synchronization demanded of the actors, in pacing and placement, is considerable, and of course the director has to coordinate everything. Feuillade, directing with shouts and a drillmaster’s whistle, drove his actors through each long-take scene. Turn off the music occasionally and imagine him calling out instructions to them.

These examples, and many others, gainsay David Kalat’s curious claim in the Kino commentary that Feuillade’s work exhibits an “anti-style” that doesn’t present stories “cinematically”–because he doesn’t exploit cutting and changes of camera position.

The camera has been plopped down perfunctorily in front of a set in which the actors meander around within the frame without any sense of composition. In several scenes the actors nonchalantly turn their backs on the audience completely. Only rarely does a shot appear in which the actors seem positioned in front of the camera for any specific pictorial effect. The shots ramble on with hardly any change of point of view until the scene ends and a new one takes its place (Disc 1, 11:54-12:20).

Actually, here and in other works, Feuillade’s staging is quite precise. I doubt that many directors today could block fixed shots as fluidly as he does; sustained, intricate staging in this sense is an almost lost art. Hou Hsiao-hsien, in his films up through Flowers of Shanghai, might be the last great exponent of this technique.

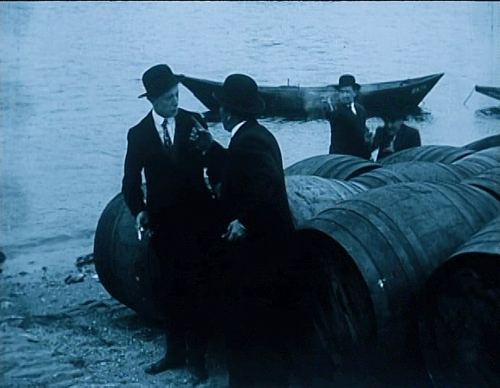

We find the same principles at work in later Fantômas episodes. Some scenes have greater pictorial splendor than the ones I’ve considered; many aficionados believe that the essence of the series is on display in the second installment, Juve contre Fantômas. Certainly it has crazier plot twists. (I got through a whole blog without mentioning Juve’s python-repelling suit, below.)

Granted, it’s hard to study the films as they’re unfolding. That’s partly because Feuillade guides our eye so subtly that we get caught up in the plot. Still, re-viewing can help us spot the fine points. With this DVD set, you have at least five and a half hours of fun before you.

In the lurid tales of Allain and Souvestre, Feuillade found sensational material. He had fine actors. He had luminous prewar Paris as a backdrop. And he had at his fingertips all the resources of tableau cinema. The whole mixture creates a lively cinematic experience. Watching films like Fantômas and Ingeborg Holm and The Mysterious X and many others from 1913, we can still be bowled over by their exquisitely modulated storytelling. If Feuillade is less baroque than Bauer and less poignant than Sjöström, he’s also more brisk, laconic, and playful. Call him the Hawks of the tableau tradition. Thanks to this new release, more Americans will have a chance to enjoy his exuberant creativity.

And they can have all the frissons they want.

Searching “tableau” in our blog entries will offer many further examples of what I’m discussing here. Our 1913 entryoffers an overview of what Feuillade’s contemporaries were up to.

The Kino set includes two other Feuillade films, The Nativity (1910) and The Dwarf (1912). These are better transfers than the main attractions, and make for some interesting comparisons with his artistic strategies in Fantômas. There’s also a short documentary on Feuillade’s career, adapted from the Gaumont box set Le Cinéma premier, which contains many Feuillade titles. Other Feuillade films are available on US DVD: Les Vampires, in an out-of-print Image set; Judex, from Flicker Alley; and various items in the Kino package Gaumont Treasures, 1897-1913. That set, a selection from the Gaumont box, includes The Agonie of Byzance, made the same year as the first installments of Fantômas.

As times changed, Feuillade adopted editing, sometimes in rather flashy forms. For examples, go to my chapter on Feuillade in Figures and here. Essays by Ben Brewster and Lea Jacobs show how performance style adjusted to the tableau tradition. Charlie Keil’s Early American Cinema in Transition traces the somewhat differing developments in U. S. cinema of the period.

For all things Fantômas, visit the Fantômas Lives website. There’s also the very helpful Encyclopédie de Fantômas (1981), self-published by the mysterious ALFU. If you want to know the percentage of deaths by defenestration in the oeuvre (6.8 %), this is the book for you. David Kalat offers a wide-ranging survey of Fantômas’ influence on modern art and popular culture in “The Long Arm of Fantômas,” in Third Person: Authoring and Exploring Vast Narratives, ed. Pat Harrigan and Noah Wardrip-Fruin (MIT Press, 2009), 211-224.

Francis Lacassin has written prolifically on both Fantômas and Feuillade. The arch criminal earns a chapter in Lacassin’s À la recherche de l’empire caché (Julliard, 1991), while his Louis Feuillade: Maître des lions et des vampires (Bordas, 1995) remains the essential work on the director.

Juve contre Fantômas.

The buddy system

Sweet Smell of Success.

DB here:

Many of our friends write books, and what are friends for if not occasionally to promote each other’s books? Here’s an armload of titles, most of them recently published. They’re so good that even if the authors weren’t our friends and colleagues, I’d still recommend them.

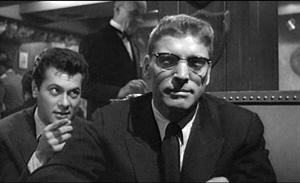

James Naremore has made major contributions to film studies since his fine monograph on Psycho, published way back in 1973. That book remains one of the most sensitive analyses of this much-discussed movie. Now he has another monograph, on the stealth classic Sweet Smell of Success. When I was coming up, Alexander Mackendrick wasn’t much appreciated, and this movie slipped under the radar. More recently it has emerged as one of the model films of the 1950s, and not just for James Wong Howe’s spectacular location cinematography. It’s a very brutal story, with Tony Curtis playing against type as venal press agent Sidney Falco and Burt Lancaster as J. J. Hunsecker, a monstrously vindictive newspaper columnist.

Jim’s book provides a scene-by-scene commentary but also more general analysis of production circumstances and directorial technique. An enlightening instance is what Mackendrick called “the ricochet”—when character A talks to character B but is aiming at character C. This allows the filmmaker great flexibility in framing and cutting, often showing C’s reactions while we hear the dialogue offscreen. In the shots surmounting this blog, Sidney is needling J. J. by asking the Senator if he approves of capital punishment. Jim’s book joins his work on Welles, Kubrick, and film noir as part of a subtle reassessment of American postwar cinema.

With the current revival of interest in André Bazin’s film theory, it’s fruitful to look again at the “classical” theoretical tradition in which he participated. “Classical” here refers to the very long period before the emergence of semiotic and psychoanalytic theories of cinema in the 1960s. The newer theories have somewhat beclouded our recognition of how imaginative and wide-ranging the old folks were. In Doubting Vision: Film and the Revelationist Tradition, Malcolm Turvey scrutinizes four thinkers who saw film as having the power to show us things beyond (or above, or below) surface reality. In the spirit of analytic philosophy, Turvey carefully lays out the positions of Béla Balázs, Jean Epstein, Siegfried Kracauer, and Dziga Vertov before asking whether their claims hold up.

With the current revival of interest in André Bazin’s film theory, it’s fruitful to look again at the “classical” theoretical tradition in which he participated. “Classical” here refers to the very long period before the emergence of semiotic and psychoanalytic theories of cinema in the 1960s. The newer theories have somewhat beclouded our recognition of how imaginative and wide-ranging the old folks were. In Doubting Vision: Film and the Revelationist Tradition, Malcolm Turvey scrutinizes four thinkers who saw film as having the power to show us things beyond (or above, or below) surface reality. In the spirit of analytic philosophy, Turvey carefully lays out the positions of Béla Balázs, Jean Epstein, Siegfried Kracauer, and Dziga Vertov before asking whether their claims hold up.

I’m not giving much away by revealing that Malcolm thinks the revelationist tendency has its problems. But his purpose isn’t simply to reject the position. He treats it as an instance of what he calls “visual skepticism,” the idea that we ought to treat our ordinary intake of the world as something suspect. This idea, Malcolm argues, is central to modernism in the visual arts. He extends his critique of visual skepticism to more recent theorists as well, notably Gilles Deleuze, and he shows how his own ideas apply to films by Hitchcock, Brakhage, and other directors. Malcolm’s book is a model of theoretical clarity and probity, and a stimulating read as well.

Skepticism of another sort is central to Carl Plantinga’s Rhetoric and Representation in Nonfiction Film. One result of semiotic theory was to question whether a film could ever adequately represent reality. If a movie is only an assembly, however complex, of conventional signs, it can’t give us access to something out there. Even a documentary, some theorists argued, had no privileged access to the real world, let alone to general truths. “Every film is a fiction film” was a refrain often heard at the time. Carl tackles this assumption head-on by carefully arguing that just because a documentary is selective, or biased, or rhetorical, that doesn’t mean that it can’t affirm true propositions about our social lives.

Like Malcolm, Carl brings a philosopher’s training in conceptual analysis to debates about the ultimate objectivity of any documentary. In adopting a position of “critical realism” opposed to skepticism, Carl examines the realistic status of images and sounds, the way documentaries are structured, and filmmakers’ use of technique. He shows, convincingly to my mind, that a documentary may offer an opinion and still be objective and reliable to a significant degree. Carl’s 1997 book went out of print before it could be published in paperback. He has enterprisingly reissued it as a print-on-demand volume, and it’s available here.

To take film theory in another direction, there’s Evolution, Literature, and Film, edited by Brian Boyd, Joseph Carroll, and Jonathan Gottschall. As a wider audience has become aware of the power of neo-Darwinian thinking, more and more scholars have been arguing that evolutionary theory can shed light on aesthetics. The most visible effort recently is Denis Dutton’s The Art Instinct.

To take film theory in another direction, there’s Evolution, Literature, and Film, edited by Brian Boyd, Joseph Carroll, and Jonathan Gottschall. As a wider audience has become aware of the power of neo-Darwinian thinking, more and more scholars have been arguing that evolutionary theory can shed light on aesthetics. The most visible effort recently is Denis Dutton’s The Art Instinct.

For some years Brian, Joe, and Jonathan have been in the forefront of this trend, with many books and articles to their credit. Their anthology pulls together broad essays on biology, evolutionary psychology, and cultural evolution before turning to art as a whole and then focusing on literature and cinema. There are also pieces displaying evolutionary interpretations of particular works, and a finale that provides examples of quantitative studies of genre, gender variation, and sexuality, including an article called “Slash Fiction and Human Mating Psychology.”

Among the film contributors are other friends like Joe Anderson, a pioneer in this domain with his 1996 book The Reality of Illusion, and Murray Smith, who provides an acute piece called “Darwin and the Directors: Film, Emotion, and the Face in the Age of Evolution.” There are also essays of mine, drawn from Poetics of Cinema. In all, this book presents a persuasive case for an empirical, broadly naturalistic approach to the arts.

By the way, the same team is involved with an annual, The Evolutionary Review, edited by Alice Andrews and Joe Carroll. Its first issue offers articles on Facebook, musical chills, women as erotic objects in film, and Art Spigelman’s In the Shadow of No Towers (by Brian Boyd).

Some books emerge from conferences, and Tom Paulus and Rob King’s Slapstick Comedy is a good instance. Based on “(Another) Slapstick Symposium,” held at the Royal Film Archive of Belgium in 2006, the anthology brings together a host of experts who look back at madcap comedy in American silent film. There are essays on particular creators—Griffith, Sennett, Fatty, and Chaplin, inevitably—as well as pieces on slapstick parodies of other movies and the genre’s relation to modernity, also inevitably. Tom Gunning offers a fine analysis of Lloyd’s Get Out and Get Under (1920), concentrating on a complex string of gags around an automobile. The collection gathers work by some of the outstanding scholars of silent film while also, of course, making you want to see these crazy movies again.

You also want to see all the movies lovingly evoked by Gary Giddins in Warning Shadows: Home Alone with Classic Cinema. As indicated in another blog entry, I find Giddins one of the best appreciative critics we’ve ever had. Any essay, indeed almost any sentence, cries out to be quoted. Here he is on Edward G. Robinson:

You also want to see all the movies lovingly evoked by Gary Giddins in Warning Shadows: Home Alone with Classic Cinema. As indicated in another blog entry, I find Giddins one of the best appreciative critics we’ve ever had. Any essay, indeed almost any sentence, cries out to be quoted. Here he is on Edward G. Robinson:

His round, thick-lipped, putty face could brighten like paternal sunshine or shut down in implacable contempt or stall with crafty desperation or pontificate with ingenuous wisdom; his short, stumpy, erect frame could sport a tailor-made as smartly as Cary Grant.

Some of the pieces in Giddins’ latest collection were designed to accompany DVDs, but they will outlast this evaporation-prone genre. Other reviews come from the New York Sun, which gave him freedom to mix and match his subjects: Young Mr. Lincoln and Lust for Life (both biopics), Lady and the Tramp and Miyazaki movies. The collection opens with Giddins’ thoughts on how changes in film exhibition, from nickelodeons to digital screens, have altered our relationship with the movies. This isn’t just nostalgia, because his survey allows him to celebrate the power of DVD to exhume forgotten titles. The standards for a film classic, he notes, “are gentler and more flexible” than those in appraising other arts. “The passing decades are a boon to the appreciation of stylistic nuance that gives certain melodramas and genre pieces the heft of individuality.”

Who was Segundo de Chomón? In the 1970s, I kept finding that films I thought were by Méliès turned out to bear this mysterious signature. You imagine a man in a cape and a floppy hat. Photographs show someone a little less operatic, but with a superb mustache. Today he’s far from a mystery, although many of his movies can’t be fully identified. Several scholars have followed his trail, none more thoroughly than Joan M. Minguet Batllori in Segundo de Chomón: The Cinema of Fascination.

Chomón started as a cinema man-of-all-work in Barcelona, translating film titles, distributing copies, and producing films for Pathé. After moving to Paris in 1905, he continued working for the company and established his fame with trick films. He returned to Barcelona to create a production company, but that failed. On he went to Italy, where he specialized in visual effects, most famously for Cabiria (1914).

In his Parisian Pathé years, he was in charge of all the studio’s trick films, which included not only stop-motion, superimpositions, and other effects but also marionettes and animation. Joan argues that he was a prime exponent of the “cinema of attractions,” Tom Gunning’s term for that early mode of filmmaking which aims to startle and enchant the audience. A famous instance is Kiriki, acrobats japonais (1907), which shows gravity-defying stunts.

Chomón accomplished this by shooting from straight down, filming the performers on the floor. They had to simulate leaps and flips as they rolled along each other’s bodies, and then they had to slip perfectly into position. This English edition of Joan’s book on Chomón, full of information and providing a “provisional filmography” along with many pages of gorgeous color images, will be available soon here.

We recently noted the anniversary of our book on classic studio cinema, a 1985 project in which we bypassed talking about exhibition. That part of the industry has been a scholarly growth area in the years since, and one of the newest yields is Epics, Spectacles, and Blockbusters: A Hollywood History, by Sheldon Hall and Steve Neale. It’s a chronological account of Big Movies, from the earliest features to the digital era, and it concentrates on how such films have been marketed and shown. It explains how exhibition changed across the decades, and how we got the phenomenon of the “roadshow” movie, the film shown selectively (only certain cities), at intervals (perhaps only one matinee and one evening screening), and at more or less fixed prices. My middle-aged readers will remember roadshow releases like The Sound of Music (1965), although there were many before and even a few since.

We recently noted the anniversary of our book on classic studio cinema, a 1985 project in which we bypassed talking about exhibition. That part of the industry has been a scholarly growth area in the years since, and one of the newest yields is Epics, Spectacles, and Blockbusters: A Hollywood History, by Sheldon Hall and Steve Neale. It’s a chronological account of Big Movies, from the earliest features to the digital era, and it concentrates on how such films have been marketed and shown. It explains how exhibition changed across the decades, and how we got the phenomenon of the “roadshow” movie, the film shown selectively (only certain cities), at intervals (perhaps only one matinee and one evening screening), and at more or less fixed prices. My middle-aged readers will remember roadshow releases like The Sound of Music (1965), although there were many before and even a few since.

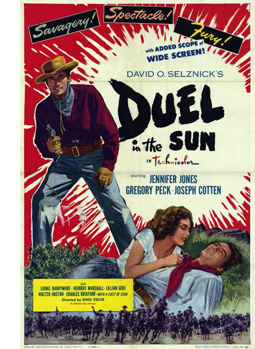

Sheldon and Steve trace in unprecedented detail the cycles of blockbusters that have run throughout American cinema. In the process they refreshingly redefine the very idea. We don’t usually think of The Best Years of Our Lives as a Big Movie, but it runs three hours and was considered a “special” production, comparable to the more obvious sprawl of Duel in the Sun. The authors bring the story up to date by considering today’s event movies as a “Cinema of Spectacular Situations.” Yes, that category includes comic-book films, Inception, and, of course, the 3D sagas that may finally be wearing out their welcome. (My editorializing, not theirs.)

Japanese cinema is endlessly fascinating in all its eras; I’d argue that in toto it’s one of the three greatest national cinemas in film history. The postwar period is exceptionally interesting because of the American occupation (1945-1951) and its effects on Japanese film culture. This period has already provoked one of the best books we have on Japanese cinema, Kyoko Hirano’s Mr. Smith Goes to Tokyo, and it finds a worthy accompaniment in Hiroshi Kitamura’s Screening Enlightenment: Hollywood and the Cultural Reconstruction of Defeated Japan. Kyoko focused on how US policy shaped domestic filmmaking, while Hiroshi asks how the Occupation helped American studios penetrate the local market.

Over six hundred Hollywood movies poured into Japan during the period, and Hiroshi traces how local tastemakers as well as U.S. policymakers drew audiences to them. Young Japanese learned about the Academy Awards, assembled in movie-study clubs to discuss what they were seeing, and were urged to consider even a gangster tale like Cry of the City (1950) as demonstrating the humanistic side of democracy. A center of this activity was Eiga no tomo (“Friends of the Movies”), a magazine that went beyond entertainment news and tried to reshape the tastes of young people. In sharp prose and vivid evidence, Hiroshi captures the ways in which American cinema promised to help heal a devastated country.

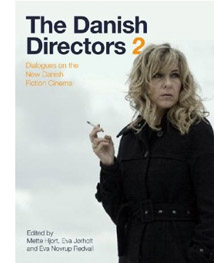

The Danish Directors, by Mette Hjort and Ib Bondebjerg, has become a standard companion to the most successful “small cinema” on the European scene. Now it has a successor in The Danish Directors 2: Dialogues on the New Danish Fictional Cinema, edited by Mette, Eva Jorholt, and Eva Novrup Redvall. Once again, we get lengthy, in-depth interviews covering the value of film education, the vagaries of funding, and filmmakers’ creative decision-making. Lone Scherfig, Christoffer Boe, Per Fly, Paprika Steen, and many other major figures are included. (Disclosure: The editors were kind enough to dedicate the book to me.)

The Danish Directors, by Mette Hjort and Ib Bondebjerg, has become a standard companion to the most successful “small cinema” on the European scene. Now it has a successor in The Danish Directors 2: Dialogues on the New Danish Fictional Cinema, edited by Mette, Eva Jorholt, and Eva Novrup Redvall. Once again, we get lengthy, in-depth interviews covering the value of film education, the vagaries of funding, and filmmakers’ creative decision-making. Lone Scherfig, Christoffer Boe, Per Fly, Paprika Steen, and many other major figures are included. (Disclosure: The editors were kind enough to dedicate the book to me.)

While the first volume is a rich storehouse of information on Danish film in “the Dogma era,” the newest volume shows how directors (some of whom made Dogma projects) have gone beyond it. In preparing 1:1, a film about Danes and Arab immigrants living in a housing project, Annette K. Olesen had a full script but concealed it from the non-professional cast. After getting the performers comfortable with ordinary situations, she began staging scenes while encouraging improvisation. Screenwriter Kim Fupz Aakeson incorporated the improvised material into revisions of the script.

By contrast, the prolific director-screenwriter Anders Thomas Jensen (Adam’s Apples, The Green Butchers), relies on strong structure, with lean expositions and sharply defined climaxes. He appreciates clean filming technique too.

It’s easy to make something that’s ugly and handheld, but you have to take telling stories with images seriously. You have to take the language of film seriously. Many Danish directors have started doing this in recent years and it’s wonderful, because there was a time when everything looked Dogma-like and I found myself thinking, “It’s got to stop now.”

To those who think that Danish cinema is at risk of becoming a cinema of cozy liberal reassurance, this collection offers many salutary signs. Every director speaks of the need to keep innovating, to push ahead provocatively. Simon Staho, whose Day and Night seems to me one of the most adventurous Danish films of recent years, aims at utter purity: “My task is to figure out how to add as little as possible to the black screen. The damned problem is that you have to add image and sound!”

What makes all these books exciting to me is a willingness to test ideas–sometimes very general ones–about cinema and the wider world by examining film as a distinctive art form. Even the most conceptual books on this week’s shelf are firmly rooted in the particular choices that creators make and the concrete ways that viewers respond.

Next stop: Vancouver International Film Festival. Whoopee!

Day and Night.

A serial for the unserious

Please silence your mobile phone during the film! Le Pied qui étreint 1: Le Micro bafouilleur sans fil (1916).

DB here, still in Yurrp:

Today the Cinémathèque Française will celebrate Bastille Day by showing one of the strangest movies the programmers could have picked–sort of the Monty Python’s Flying Circus of the 1910s.

Le Pied qui étreint (1916), directed by Jacques Feyder, is a four-part parody of the crime serial. The title translates as “The Clutching Foot,” and as if that weren’t a clear enough signal, Gaumont’s announcement in the trade press set the tone:

A sensational film in 1979 episodes–assembled in four installments without any dull spots.

The running conflict pits the plus-size inventor Clarin, his boy assistant, and his rich girlfriend Eliane against a ruthless, incompetent secret society modeled on Feuillade’s Vampires. The boss of the gang is a mysterious masked figure always wheeled around in a baby carriage with his feet sticking out in front. Gang members recognize each other by flashing an emblem of a bare foot painted on the soles of their shoes.

In the first episode, Clarin invents a wireless telephone, which causes him some embarrassment in movie theatres. Electricity is also on the mind of the Clutching Foot gang, who rewire Eliane’s house so that when she answers the phone she falls into spasms of shocks. Soon all the servants who try to grab her are splayed out on the floor, convulsing in synchronization. Fortunately Clarin and his assistant rescue all by judicious use of rubber gloves.

In “The Black Ray,” the gang devises a gadget that emits a beam that will turn a white person black. The device proves startlingly effective on Eliane, but again Clarin has a scientific solution, sending a current through her to revive her pale beauty. Part three involves the Chinese branch of the The Clutching Foot. They kidnap Eliane and lull her into languor by means of a sinister incense. But Clarin, disguised as a Chinese, rescues her, and his boy displays unexpected pistol skills by dispatching a dozen Chinese while eating a bun.

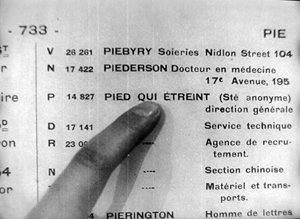

Feyder and his scriptwriters make merciless fun of the still-emerging serial conventions. Masked thugs break into a house, but passing citizens and policemen are completely indifferent. A mysterious message is sent to the heroine via paper airplane, which gets stuck in her hair. When some of the gang converge on Eliane’s parlor, they hide in different crannies and flash their foot-insignia all at once. The apparently unlimited resources of Zigomar and Fantomas are taken to their logical conclusion when the Clutching Foot team boasts of its resources in the city directory.

The iconic image of cops converging on crooks is pushed to a nutty limit.

The last installment is the most peculiar. The master of the Clutching Foot is revealed to be none other than Charlie Chaplin. This shameless effort to cash in on the star’s popularity makes him central to the episode. After a chase through a hotel, Chaplin escapes the cops, worms his way into Eliane’s affections, and winds up marrying her. The wedding feast features a lookalike for the star Max Linder as well as guests from other Gaumont films, including the child star Bout-de-Zan and Marcel Levèsque, a comic fixture in early Feuillade and memorable as the censorious concierge in Le Crime de Mr. Lange. The Charlot imitator is Georges Biscot, discovered by Feyder and soon to play many roles for Feuillade. The woman who slinks around in her leotard and makes with those Irma Vep eyes is Musidora herself. The jokey star walk-on is clearly not unique to our time.

The movie ventures into new territory at the end, when Charlot and Eliane retire to the bridal suite. For once the randy tramp gets some real action.

In a nice closing touch, the hotel staffer who collects shoes for cleaning writes the room number in chalk on Charlie’s boots–a recollection of the high-sign of his gang.

I haven’t mentioned other appeals, such as Chinese gangsters flung off a spinning weather vane, or the moment in the last installment when Clarin’s lad sets up a projector in the lab and, as if willing the whole movie to start over, screens the opening of the serial’s first part. Take that, Postmodernism!

It’s all a bit juvenile, but no harm in that. Sometimes, as Tsui Hark remarks, it’s fun to be stupid. And Le Pied qui étreint should remind us of something important. Too often we assume that parody is a sign that a form or genre is exhausted, that there’s nothing left to do but mock it. But that’s not always so. Parody needn’t announce decline or decadence. Parody is lurking everywhere, ready to spring out as soon as conventions are crystallizing. Irreverence, vulgarity, reflexivity, derangement, and dirty fun are wired into popular cinema from the very start.

For contemporary reactions to the film, which were a little stiff-lipped, see Henri Bousquet, “‘Le pied qui étreint,'” Cahiers de la Cinémathèque no. 40 (1984), 23-24. My quotation from the Gaumont ad is taken from this article. For a brief online comment and a nice production still, go here.

Thanks to Nicola, Francis, and Bruno, who reminded me that Feyder was a Belgian.

Marcel Levèsque, Kitty Hott, Biscot, and Musidora at the wedding feast.

More cinema Bolognese

Josette Andriot, decked out for Protéa.

Kristin here, with more from Cinema Ritrovato in Bologna:

When one thinks of female masters of disguise and action in the silent cinema, Musidora as Irma Vep in Feuillade’s Les Vampyrs probably springs first to mind. But for the historian, hovering always in the background was the legendary film by Victorin-Hippolyte Jasset, Protéa (1913), with Josette Andriot in the lead role. We knew the film mainly from a frequently reproduced image of the heroine in a black outfit, one of many she wears in the film.

Andriot was unconventionally beautiful, with dark hair and eyes and strong rather than delicate features. She was a genuine athlete, hired initially by Jasset for her riding ability, though he later exploited her acrobatic abilities in chases and scrambles around buildings.

Andriot was unconventionally beautiful, with dark hair and eyes and strong rather than delicate features. She was a genuine athlete, hired initially by Jasset for her riding ability, though he later exploited her acrobatic abilities in chases and scrambles around buildings.

Protéa has now been restored, though there is still missing footage. The heroine’s partner is Lucien Bataille, looking rather like a particularly devious James Cagney in the role of L’Anguille (“The Eel”), whose quick-change abilities and athleticism match hers. The thin, episodic plot revolves around a classic Macguffin, a treaty between two imaginary, vaguely Eastern European countries. The pair must acquire the document and hold onto it through one danger after another, outnumbered and chased all the while by a ruthless gang of spies for the other side.

I was startled by how modern the film seemed. Critics today tend to claim, inaccurately, that big action films throw some big thrill at the audience every few minutes. Protéa really does. The underlying purpose of the plot is to have the two leads escape from one sticky situation and change disguises, only to land immediately in another sticky situation. It’s essentially a serial boiled down into a feature.

The term “cinema of attractions” was originally coined by Tom Gunning to describe very early films that depended on novelties rather than narratives. These days, many academics apply the phrase to almost any film, old or new, boasting a lot of action and big special effects. But I’m tempted to use it of Protéa anyway. Jasset usually doesn’t keep Protéa and L’Anguille in any one disguise or situation long enough to exploit the initial premise. One moment she’s pretending to be a man; next thing we know, she’s an elegant partygoer and L’Anguille is a servant. The basic problem is that whenever the characters get into trouble, they don’t rise to the occasion by exploiting their current roles more cleverly. They just flee and assume a new disguise to try again. As a result most of the individual episodes remain unmemorable.

One exception is a sustained sequence showing the couple as traveling animal trainers. At one point they crawl into the cage and play with a real lion, and they stay in these disguises long enough to actually use the big cats to fend off their pursuers. The final hectic chase, with Protéa on a bicycle fleeing toward a bridge set aflame by the villains, is the most impressive passage we can enjoy as sustained action. (I won’t reveal how it comes out, except to say that the climactic moment prefigures a modern action heroine driving a bus toward a gap in an unfinished freeway.)

Protéa is fun, in large part due to the talent of the two leads. It’s a pity that this was Jasset’s penultimate film. He died in hospital before it was released. (His last film, La Danseuse de Kali, also starring Andriot, was recently rediscovered by our friend Hiroshi Komatsu and was shown in this year’s festival.) Perhaps Jasset would have developed into one of the major directors of serials. Still, one can see why Feuillade, who knew how to build suspense by stretching out a scene’s action, became the French master of the form.

Etaix Refurbished

In an earlier entry, I mentioned that for some years French comic director and actor Pierre Etaix had not controlled the rights to his own films (two shorts and six fiction features). During that time, they were out of circulation and unavailable in any format. That situation has finally been rectified. Etaix has recovered the rights, and all the films have now been restored. They were re-premiered earlier this year at Cannes, and two were included in Il Cinema Ritrovato: the short Heureux anniversaire (1962) and the feature Le grand amour (1969).

Etaix’s early work in the cinema was during the 1950s as an assistant to Jacques Tati, and he is widely seen as having been greatly influenced by Tati. That’s true to some degree. In Le grand amour there are gags using sudden peculiar noises. Although the plot centers around the hero Pierre, his wife Florence, and his in-laws, there are nosy neighbors and waiters through whose eyes we are occasionally asked to view the action. When Pierre’s friend gives him instructions on how to behave on an upcoming date with his pretty secretary, bar patrons assume that they’re witnessing two gay men flirting.

Still, Etaix’s general approach is not particularly Tatian. He does not play a continuing character from film to film. In Le grand amour, as the young husband lured into managing his father-in-law’s factory, he dresses in conservative suits and casual wear; no Hush Puppies, striped socks, and too-short raincoat for him. Pierre succeeds in his dull job, unlike Hulot, who makes a mess of things when given a low-level job at his brother-in-law’s factory. The neighbors watch Pierre not because he is eccentric, but because they jump to wrong conclusions about his mundane behavior.

More importantly, though, Le grand amour creates a great deal of its humor with a technique that Tati would never use. He frequently shows hypothetical alternatives to the scene at hand. What if Pierre’s sophisticated friend were married to Florence? We see a scene played out with the friend in his place. There is a dream in which Pierre’s bed drives like a car along a country road, encountering other bed-cars and finally picking up the new secretary, hitchhiking by the road. When Pierre finally dares to take the secretary out to dinner, he launches into a nervous, boring monologue on business prospects, and we see him as she does, successively older and grayer with each reverse shot. When the gossipy neighbors pass along a story about Pierre, we see the successively exaggerated versions played out one by one, from the reality in which he merely tips his hat to a pretty woman he passes in a park through overt flirting to a passionate encounter behind a bush.

Le grand amour is not as funny as Tati’s films, but that probably results from an explicit melancholy that underlies this tale of disillusionment with marriage and final acceptance of the realities of life-long love. At times it reminded me more of the playful moments in Truffaut, especially in Shoot the Piano Player. Whether or not one wants to place Etaix in the New Wave, his play between reality and fantasy would seem to put him in the category of “ludic modernism” that Malcolm Turvey spoke about in his paper at the recent Society for the Cognitive Study of the Moving Image conference.

The restored print was beautiful, with the kinds of bright and pastel colors and high-key lighting that one seldom sees in the drab films of today. Presumably the new copies will show at other festivals and in art-houses with DVD releases to come.

Cinephiles’ corner

Bologna brings out a bevy of critics, historians, programmers, and unabashed film lovers of all stripes. Herewith, a sampling from DB.

Two critics for the ages: Kent Jones of Physical Evidence and the World Cinema Foundation, alongside Joe McBride, author of books on Ford, Capra, Welles, and Spielberg.

Dick Abel and Virginia Wright Wexman, both distinguished scholars, flank a copy of Dick’s book, French Cinema: The First Wave–presumably kept under glass like the rare specimen it is.

Curatorial cuddling: Haden Guest of the Harvard Film Archive, Adrienne Mancia retired from MoMA (and once a UW Badger).

The Cottafavi Cult invictus: Critics and programmers Barbara Wurm, Olaf Möller, and Christoph Uber, always in the front row.

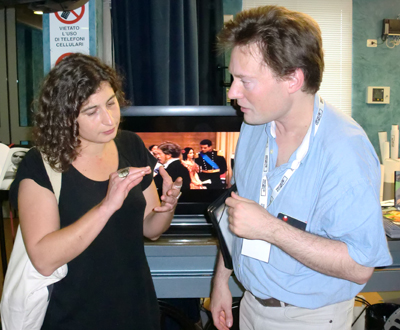

Camille Blot-Wellens, director of Film Collections at the Cinémathèque Française tells Danish historian Casper Tybjerg of her restoration of Albert Capellani’s Chevalier de Maison-Rouge (1914).

Two walking film encyclopedias sitting down: Kevin Brownlow, pioneer British historian, director, and collector, and Lee Tsiantis of Turner Classic Movies.

David Meeker, master of British cinema and jazz on the screen; Matthew Bernstein, author of Walter Wanger, a study of the Leo Frank lynching, and other studies of film history and culture.

Mariann Lewinsky, heroic programmer of the 1910 series and the Capellani retrospective, introduces Nikolaus Wostry, of Filmarchiv Austria.

More to come in at least one more Bologna-based entry!