Archive for the 'Silent film' Category

Seed-beds of style

The Hunt for Red October.

DB here:

Seminar, orig. German (1889): A class that meets for systematic study under the direction of a teacher. From Latin seminarium, “seed-plot.”

I retired from full-time teaching in July of 2005. Since then, while writing and traveling (both chronicled on this website), I’ve done occasional lectures. But this fall I tried something else. At the invitation of Lea Jacobs here at Madison, I collaborated with her on a graduate seminar called Film Stylistics.

It was a good opportunity for me. I had a chance to learn from Lea, Ben Brewster, and the students and sitters-in. The class also enabled me to test and revise some ideas I’d already explored, while garnering new ideas and information. I helped plan the sessions and pick the films, but I had no responsibilities about grading. I hope, though, to read the students’ papers at some point after the term is over.

Our goal was to introduce students to studying style historically and conceptually. We focused on group styles rather than “authorial” ones because we wanted to explore particular concepts. How useful is the concept of group norms in understanding broad stylistic trends? Can we explain stylistic change through conceptions of progress toward some norm? Does the model of problem and solution help explain not only a particular innovation but also the group’s acceptance of it? How viable are notions of influence in explaining change? How much power should we assign to individual innovation? Can we think of filmmaking institutions as not only constraining style (through tradition and conformity) but also enabling certain possibilities—nudging filmmakers in certain directions? Does stylistic study favor a comparative method, one that encourages us to range across major and minor films, as well as different countries and periods?

These are pretty abstract questions, so we wanted some particular cases. Lea and I picked three areas of broad stylistic change: the emergence of widescreen cinema in the 1950s, the arrival of sync-sound filming in the late 1920s, and the development of analytical editing or “scene dissection” in the 1910s and 1920s. We tackled these areas in this order, violating chronology because we wanted to move from somewhat hard problems to the hardest of all: Why did filmmakers in the US, and soon in other countries, move toward what has become the lingua franca of film technique, continuity editing?

The results of our research on these matters will emerge over the next few years, I expect. In the short term, during my final lecture Tuesday I went off on what I hope wasn’t too much of a tangent. I got interested in one particular kind of cut, and it led me to see, once more, how different filmmaking traditions can make varying uses of apparently similar techniques.

More cutting remarks

My concern was the axial cut. That’s a cut that shifts the framing straight along the lens axis. Usually, the cut carries us “straight in” from a long shot to a closer view, but it can also cut “straight back” from a detail. What could be simpler? Yet such an almost primitive device harbors intriguing expressive possibilities.

Axial cuts aren’t all that common nowadays, I think. Today’s filmmakers prefer to change the angle when they cut to a closer or more distant setup. But such wasn’t the case in the cinema of the 1910s and 1920s.

In the heyday of tableau-based staging, 1908-1918 or so, filmmakers seldom cut into the scene at all. European directors especially tended to shape the development of the action by moving actors around the set, shifting them closer to the camera or farther away. The most common cuts were “inserts” of details, mostly printed matter (letters, telegrams) or a photograph. But when tableau scenes did cut into the players, the cuts tended to be axial: the framing moved straight in to enlarge a moment of performance. Here’s an instance from the 1916 Russian film Nelly Raintseva.

During the mid-1910s, American films moved away from the tableau style toward a more editing-driven technique. This approach often relied on more angled framing and a greater penetration of the playing space, of the kind we’re familiar with today. But axial cuts hung on in American films, even in quickly-cut scenes. Lea pointed out some nice examples in Wild and Woolly (1917), especially those involving movement. In the example below, the first cut carries us backward rather than forward, and the second is a cut-in, but both are along the lens axis.

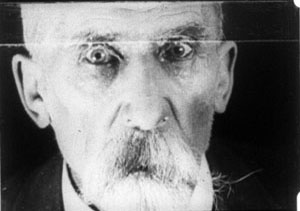

During the 1920s, axial cuts become a secondary tool of the American filmmaker, who now had many other camera setups available. But Soviet filmmakers of the 1920s, who adopted many American techniques in the name of modernizing their cinema, seemed to see fresh possibilities in the axial cut. For instance, in Dovzhenko’s Arsenal (1929), it becomes a percussive accent. The astonishment of a bureaucrat under siege is conveyed by a string of very fast enlargements.

The Soviets called such cuts “concentration cuts,” a good term for the way they make a figure seem to pop out at us. From being a simple enlargement (in tableau cinema) or one among many methods of penetrating the scene’s space (in Hollywood continuity), the axial cut has been given a new force, thanks to adding more shots and making them quite brief.

This aggressive method for seizing our eye—Notice this now!—has appeared in modern filmmaking too, as in this passage from Die Hard (1988).

Here the axial cut is clearly subjective, rendering John McClane’s realization that he can use the Christmas wrapping tape in his combat with the thieves. Director John McTiernan employed the device again in The Hunt for Red October (1990). The frames surmounting this entry show the heroes suddenly being fired upon.

It seems likely that many modern directors became aware of this device from seeing Lydia’s discovery of the pecked-up body of farmer Dan in The Birds (1963). Hitchcock knew Soviet montage techniques, so maybe we have a chain of influence here. In any case, the somewhat overbearing aggressiveness of the concentration cut has often been parodied on The Simpsons. Here’s a recent example.

By the law of the camera axis

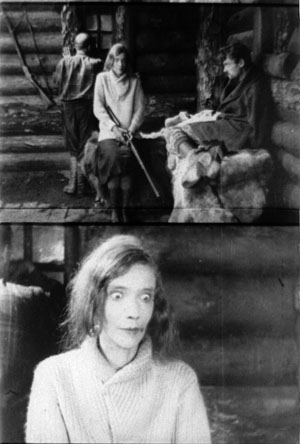

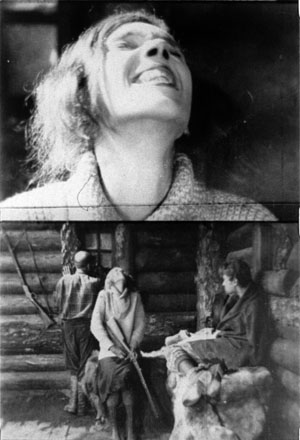

Axial cutting can be used more pervasively, as a structuring element for an entire scene. This is what Lev Kuleshov does in a climactic moment of By the Law (1926). Edith and her husband have kept the murderer at rifle point for days, and the strain is starting to show. She becomes hysterical, and Kuleshov uses a ragged rhythm of stasis and movement to convey it. First he cuts straight in from a master shot to a medium shot of her. I reproduce the frames from the film strip, for reasons that will become obvious.

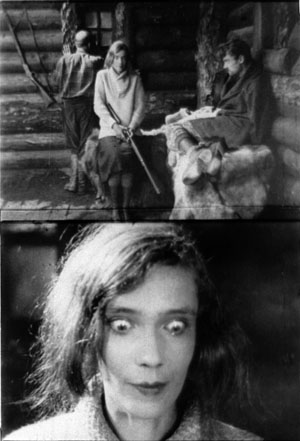

Then Kuleshov cuts straight back to the master setup. Again he cuts in, but to a closer view of Edith as she becomes more frenzied.

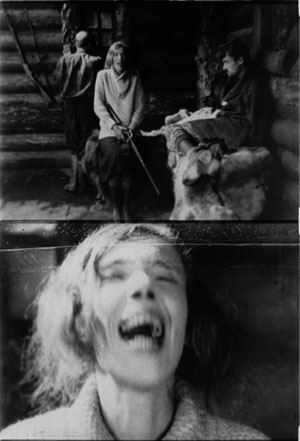

Cut back once more to the long shot, but only for fourteen frames. That shot is interrupted by a shot of Edith already laughing crazily, her head tipped back.

The shot of her laugh lasts only five frames, and this mere glimpse, combined with the blatant mismatch of movement, makes the onset of her spell all the more startling. When we cut back to the long shot her face and position now match.

The abrupt quality of her outburst would not have been as striking if Kuleshov had varied his angle. As the earlier examples show, when only shot scale changes and angle remains the same, the cuts can be very harsh, and Kuleshov accentuates this quality with a flagrant mismatch.

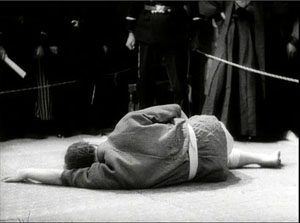

Akira Kurosawa likewise used the concentration cut to provide salient moments throughout his work; it almost became a stylistic fingerprint. At several points in Sugata Sanshiro (1943) he uses the device in the usual popping-forward way. But he varies it during Sanshiro’s combat with old Murai. He reserves dynamic, often elliptical cuts for moments of rapid action, and then he uses axial cuts for moments of stasis or highly repetitive maneuvers. In effect, the moments of peak action happen almost too quickly, while the moments of waiting are emphasized by cut-ins.

So at the start of the match, a series of axial cuts, linked by dissolves, present the fighters in a slow dance. But the ensuing throws are editing briskly. When old Murai is thrown and lies gasping on the mat, axial cuts accentuate his immobility. Kurosawa adds a rhythmic urgency on the soundtrack. After each cut-in, we hear the voice of Murai’s daughter, either offscreen or in his thoughts: “Father will win.” “Father will win.” “Father will surely win.”

The matching of lines to the editing is at work in the Simpsons parody too, in which the Comic Book Guy’s words are heard in tempo with the concentration cuts. “You. Are. Acceptable.”

Montage and the axial cut

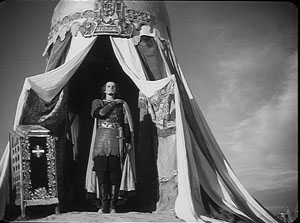

By now it’s easy for us to see that one scene from Alexander Nevsky (1938) opens with a series of axial cuts, out and in.

But why would Eisenstein, master of montage, regress to such a primitive device? He had occasionally used axial cuts in his silent films, as when we see Kerensky brooding in the Winter Palace in October (1928).

And Potemkin‘s famous cuts in to the Cossack slashing at the camera (that is, the baby, the old lady) are axial. (These cuts are pastiched by Eli Roth and Tarantino in Inglourious Basterds.) At the limit, Eisenstein toyed with the axial cut by moving the figures around during the shot change. In Potemkin, the ship’s officer reports to the captain that the crew has refused to eat. The captain leaves one shot and climbs the stair before Eisenstein cuts in to show him leaving again. The repetition would not be so perceptible if Eisenstein had varied the angle.

In the 1930s, Eisenstein began thinking about the axial cut as a basic structural element of a scene. In both his theory and practice, he promoted the axial cut to a level of prominence it hadn’t seen since the days of the tableau. Usually the cuts involve static subjects, like most of Kurosawa’s, but he still exploits the cut-ins to create vivid, if spatially impossible effects. At one point our popping in closer to Ivan the Terrible is doubled by him majestically and magically popping out of his tent to meet us, like a thrusting chess piece.

The new primacy of axial cutting comes from Eisenstein’s idea that “montage units” could powerfully organize the space of a scene. He thought that you could imagine filming a scene from only a few general positions, but then varying camera setups within each of these orientations. The montage unit was a cluster of framings taken from roughly the same orientation, as in the Pskov and Ivan scenes.

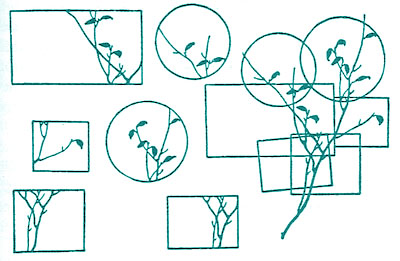

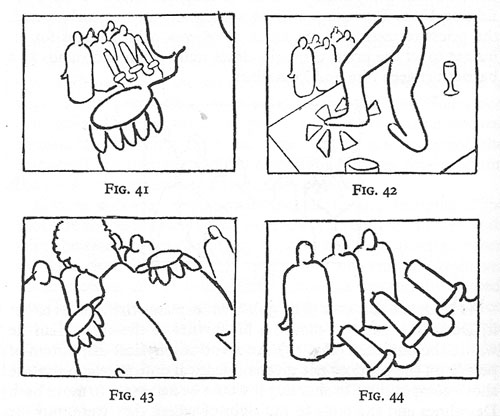

The idea may derive from his study of Japanese art, shown further above, in which he explored how a single image of a cherry branch could be chopped up into a great variety of compositions. In his course at the Soviet film school, he illustrated with a hypothetical scene of the Haitian revolutionary Dessalines holding his enemies at bay at a banquet. After imagining a master shot from the farthest-back position in the montage unit, Eisenstein proposes a series of dynamic closer views.

Eisenstein didn’t think that each scene had to be handled in a single montage unit. You could create two or three predominant orientations, with shots from each woven together. Or you could gain a sudden accent when a stream of setups from the same unit was interrupted by one from a very different angle. These ideas he put into practice throughout Nevsky and Ivan the Terrible.

Why? Eisenstein thought that combining shots taken from roughly the same orientation yielded a musical play between constant elements and variation. Each shot shows us something we’ve seen before but also something new, the way a bass line or sustained chords can continue underneath a changing melody. Eisenstein was convinced that this flowing weave of visual elements gave the spectator a deeper involvement in the film as it unfolded—an involvement akin to that found in Wagnerian opera.

The axial cut is a good example of how even a simple stylistic choice harbors rich creative possibilities. It also shows how a technique can change its impact in different filmmaking traditions. In the tableau tradition the axial cut was for the most part an abrupt enlargement heightening a moment of strong acting. In the early days of Hollywood continuity it became one editing option among many, and its power was somewhat muted. For the Soviets, concentration cuts could be multiplied and joined with fast cutting and big close-ups. The result could jolt the viewer by italicizing a face or an object–a purpose that has been taken up by contemporary Hollywood. For Kurosawa, the technique offered a way to contrast extreme movement and extreme stillness. And for Eisenstein, it suggested a global strategy for weaving visual elements into an immersive whole.

The protean functions assumed by this simple device remind us of how much there is yet to discover about film style. Despite all our discoveries over the last three decades, we have only begun. The name is apt: A seminar is where things start.

For more on the staging strategies of the tableau style, see On the History of Film Style and Figures Traced in Light: On Cinematic Staging, as well as blog entries here and here and here and here. You can find examples of emerging Hollywood continuity techniques in this entry on 1917 and this one on William S. Hart and this one on Doug Fairbanks. Sugata Sanshiro is at last available in a good DVD version from Criterion as part of its big Kurosawa box. Eisenstein’s ideas about the axial cut are explained in Vladimir Nizhny, Lessons with Eisenstein, trans. and ed. Ivor Montagu and Jay Leyda (New York: Hill and Wang, 1962), Chapters II and III. In The Cinema of Eisenstein I try to show how these ideas are employed in the Old Man’s late films.

Seated: Leslie Debauche, Lea Jacobs, Rebecca Genauer, Pam Reisel, Amanda McQueen. Standing: Karin Kolb, Andrea Comiskey, Ben Brewster, John Powers, Tristan Mentz, Heather Heckman, Aaron Granat, Jenny Oyallon-Koloski, Jonah Horwitz, and Booth Wilson. Evan Davis had to leave early.

Things we like of late

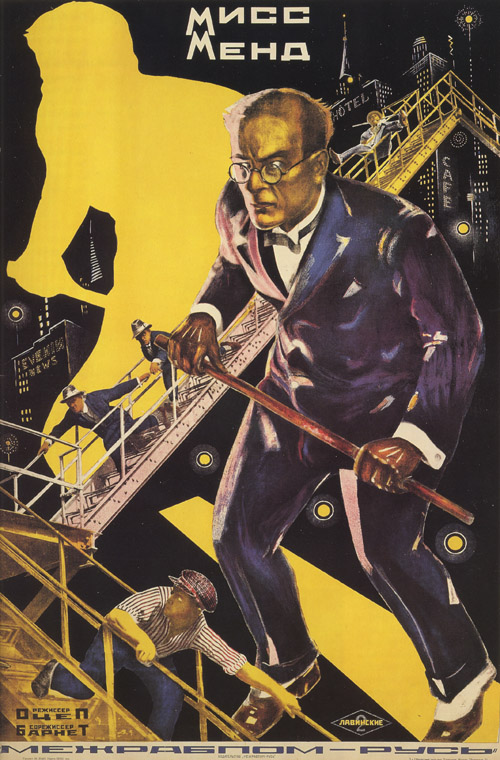

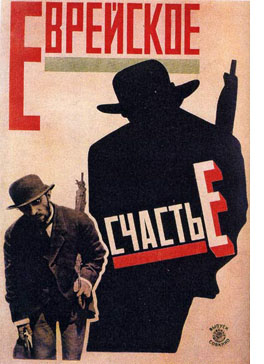

One of several posters the Stenberg brothers designed for Miss Mend.

We’ve been quite busy in the tail end of October. David sweated over a Bresson essay, started on his online version of Planet Hong Kong, and continued to help out in Lea Jacobs’ seminar on film stylistics. Kristin has started organizing a book about the statuary from the site in Egypt where she works for three weeks each year. And both of us have been steering the ninth edition of Film Art: An Introduction through the final phase of production. So instead of a blog essay this week, we offer some items from recent months that we think deserve wider notice and in some cases a pat on the back.

In our second report from the Vancouver film festival, Kristin wrote about a Chilean film, The Maid. She suggested that it was entertaining enough to be remade in English as a vehicle for an actress willing to play middle-aged and curmudgeonly. On October 16, the film was released theatrically. Starting in one theater, then going to six, and now 13 in its third week, it’s doing pretty well judging by per-theater averages. It’s not likely to get beyond big-city arthouses, but at least a release means that it should come out on DVD.

Speaking of DVDs, German silent cinema continues to be well-served with two new releases from British firm Eureka! F. W. Murnau’s 1922 film Phantom was already available in the US on the 2006 disc from Flicker Alley. The new Eureka! set includes both Phantom and Die Finanzen des Grossherzogs (1924). We saw the latter years ago at the National Film Theatre in London. It’s a comedy, and it struck us that Murnau was a bit ill at ease in that genre. Still, any Murnau film is worth a look. The set contains commentary on Die Finanzen by David Kalat, and there’s an essay on both films by Janet Bergstrom.

Speaking of DVDs, German silent cinema continues to be well-served with two new releases from British firm Eureka! F. W. Murnau’s 1922 film Phantom was already available in the US on the 2006 disc from Flicker Alley. The new Eureka! set includes both Phantom and Die Finanzen des Grossherzogs (1924). We saw the latter years ago at the National Film Theatre in London. It’s a comedy, and it struck us that Murnau was a bit ill at ease in that genre. Still, any Murnau film is worth a look. The set contains commentary on Die Finanzen by David Kalat, and there’s an essay on both films by Janet Bergstrom.

One of the best arguments that sequels and series, even those about super-villains out to rule the world, aren’t necessarily bad is Fritz Lang’s Dr. Mabuse films. They span almost the length of his directorial career, from the two-part serial Dr. Mabuse der Spieler in 1922 through Das Testament des Dr. Mabuse in 1933, up to his last but definitely not least film, Die 1000 Augen des Dr. Mabuse (1960), which David included in his Belgian summer course. For those who can’t get enough of this arch-fiend and his followers, Eureka! has packaged all three in a new boxed set. There are numerous extras, which you can read about here. For those who have only seen The 1000 Eyes of Dr. Mabuse dubbed in English, this set gives the option of German with subtitles or dubbed. (The films are not available from Eureka! separately.)

The films of Lev Kuleshov pupil Boris Barnet are only gradually being discovered outside Russia. One of the hits of this year’s “Il Giornate del Cinema Muto” was his 1928 comedy, The House on Trubnaya. Yes, there were Soviet Montage comedies, and this is one of the funniest. Let’s hope an enterprising company brings it out on DVD.* In the meantime, Flicker Alley is doing its bit to make Barnett known by releasing his 1926 three-part serial, Miss Mend. We saw it years ago without subtitles, so we look forward to finally finding out exactly what this fast-paced thriller is about. Something anti-capitalist involving the “Rocfeller and Co.” factory.

Soviet film was much on our minds this semester because our Cinematheque was running a series of films by Grigori Alexandrov. Probably best known for collaborating on Eisenstein’s silent films, Alexandrov came into his own in the 1930s with a series of lumpy but ingratiating musicals. They run the gamut from slapstick to mild satire (of familiar targets like bureaucrats). He likes silly gags, direct address to the audience, and a sort of relentless jollity that seems designed to prove Stalin’s claim in those years of privation that “Life has become gayer, comrades, life has become more joyous.”

Jolly Fellows (aka Jazz Comedy, 1934) is a somewhat labored effort in Marx Brothers absurdity, while Bright Path (1940) gives us a Stakhanovite Cinderella. It’s full of special-effects trickery used for comic effect, as when a poster coyly comes to life.

Although Alexandrov helped bring Hollywood production values to Soviet cinema, his 1936 Circus is a pointed critique of American racial bigotry.

Alexandrov’s best known film is Volga Volga (1938), reportedly Stalin’s favorite movie. It’s a meandering tale enacting the battle of highbrow music and popular tastes, including a clever scene (perhaps derived from the “Isn’t It Romantic?” number of Love Me Tonight) in which the movie’s principal tune jumps from boat to boat down the river, until it has become an unofficial national anthem. The films star Alexandrov’s wife, Lyubov Orlova, whose bullheaded energy swamps all resistance. The series is from a touring program, Red Hollywood, and you can read the background here.

Wisconsin Bioscope silent films went south in August–specifically, to São Paulo’s third Brazilian Days of the Silent Cinema. Here at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, Dan Fuller, a photographer and historian of photography, teaches students to use classic cameras and devise their own 1910s movies. Of the two Bioscope films chosen for the São Paolo festival, A Expedição brasieira de 1916 (2006) depicts the first earthlings’ arrival on the moon. It features a stirring performance by a novice actor (above) whose film career was tragically cut short when he decided to become a professor.

Cinema in yet another land is the subject of Research Guide to Japanese Film Studies by Abé Mark Nornes and Aaron Gerow. At its center is a robust bibliography, including journals as well as books, but there’s much more: a survey of archival collections of films and documents, a list of film distributors, a gathering of online resources, and even a list of bookstores specializing in Japanese cinema. Donald Richie calls it “a reference work which both illuminates and defines this field, clearing a formerly obscured terrain for future scholarship.” Markus and Aaron are strong participants in a tide of younger scholars, both Asian and Western, who are rethinking this very important national cinema.

Images, not moving, come at you in another package. Remember Viewmasters? Vladimir, a projectionist at the Northwest Film Center in Portland, makes handsome viewmaster-style discs presenting strange tales culled from Kafka, Calvino, and less-known sources. The images are still-lifes incorporating toys and props, and it’s up to you to figure out the narrative. Concept sometimes outruns execution, but the shots suggest a childhood world turned sinister. You can even get your own viewer–called, naturally, a Vladmaster.

Images, not moving, come at you in another package. Remember Viewmasters? Vladimir, a projectionist at the Northwest Film Center in Portland, makes handsome viewmaster-style discs presenting strange tales culled from Kafka, Calvino, and less-known sources. The images are still-lifes incorporating toys and props, and it’s up to you to figure out the narrative. Concept sometimes outruns execution, but the shots suggest a childhood world turned sinister. You can even get your own viewer–called, naturally, a Vladmaster.

At Parallax View, Sean Axmaker is building an online archive of the complete run of the legendary magazine Movietone News. Richard T. Jameson and Kathleen Murphy are leading voices in American film criticism, but I suspect that the younger generation isn’t as aware of them as it should be. In Movietone News and elsewhere they provide a body of criticism that nicely balances judgment, information, and ideas. Hats off to Jim Emerson for using Halloween as an occasion to point up Richard’s astute observations on modern shot design.

On Sunday night we went along with Jeff Smith to a campus lecture by Steven Pinker. The talk was a condensation of Pinker’s book The Stuff of Thought, a fascinating effort to show how various dimensions of language, chiefly semantics and pragmatics, reflect basic concepts of space, time, causality, and social relations. Language, Pinker says, furnishes a window into human nature. In a virtuoso turn, the book wraps up two trilogies at once: it caps a pair on cognitive and evolutionary theory (How the Mind Works and The Blank Slate) and a pair on grammar and semantics (The Language Instinct and Words and Rules).

On Sunday night we went along with Jeff Smith to a campus lecture by Steven Pinker. The talk was a condensation of Pinker’s book The Stuff of Thought, a fascinating effort to show how various dimensions of language, chiefly semantics and pragmatics, reflect basic concepts of space, time, causality, and social relations. Language, Pinker says, furnishes a window into human nature. In a virtuoso turn, the book wraps up two trilogies at once: it caps a pair on cognitive and evolutionary theory (How the Mind Works and The Blank Slate) and a pair on grammar and semantics (The Language Instinct and Words and Rules).

David first heard Pinker speak at an at extraordinary conference in Santa Barbara in August 1999. Coordinated by Leda Cosmides and John Tooby, “Imagination and the Adapted Mind” was an effort to explore how the arts could be illuminated by contemporary psychology, particularly one informed by an evolutionary perspective. This event–featuring not only Pinker but also Mark Turner, Eleanor Rosch, Ellen Dissayanake, Don Browne, and other luminaries–was a major moment in bringing “evolutionary aesthetics” to the table, although it’s taken about a decade for most humanists to catch up. (Several of the papers are available in a double issue of SubStance.) It was at that event that Pinker made his notorious suggestion that art was a byproduct of the brain’s evolution, a sort of “mental cheesecake” designed as a compact “superstimulus” appealing to our senses, mind, and emotions.

David had read The Stuff of Thought when it came out and had viewed the talk online. Sunday’s lecture remained a compelling performance, packing a remarkable number of ideas, data, and vivid examples into an entertaining seventy-five minutes. Pinker has been called the Dawkins of linguistics and cognitive psychology, but his sense of humor is rowdier. His straightfaced analysis of swearing is lively enough on the page, but it’s uproarious live.

Finally: Ever notice how many classic kung-fu movies are in widescreen? David has posted a new online essay tracing how Shaw Brothers popularized the anamorphic format in Hong Kong. The essay also considers how the widescreen format led Hong Kong filmmakers toward a distinctive approach to composition, cinematography, and dynamic movement. . . . of which the image below is a fair instance.

*[Nov 5: Thanks to James Steffen for alerting us to the fact that Edition Filmmuseum is bringing out The House on Trubnaya, along with Barnett’s other silent comedy of the same period, The Girl with the Hat Box, soon. There’s an impressive list of films in preparation, including the rare Expressionist classic Von morgens bis Mitternacht (1920), by Karl Heinz Martin. Comedy lovers should key an eye open for the release of a collection of Max Davidson’s hilarious silent comic shorts, including, we presume, the immortal Pass the Gravy.

Variety also has announced that Sundance is going national. On January 28, 2010, eight filmmakers will present their films and hold Q&As in eight theaters across the U.S.A. Madison, with one of only two Sundance multiplexes in the country, will be one of the host cities.]

Return to the 36th Chamber.

Searching for surprises, and frites

DB here:

Studying film history ought to be continually surprising. Yes, you often find your hunches and assumptions confirmed (which often means it’s time to check them again). But sometimes you find stuff coming out of left field that you had never expected. It would be too pompous to call these items breakthroughs, but every historian knows the little burst of pleasure that comes from seeing something that makes you say: How odd. I didn’t expect that. You might even allow yourself a Wow! now and then.

I was saying wow a fair amount during my two weeks in Brussels this summer. I go regularly, and not just for the moules, frites, and stoemp. I go to the Royal Film Archive, where I study old films. This time I was continuing to pursue some research questions that drove me in 2007 and 2008. What staging and editing strategies are at work in films of the crucial years 1910-1917? How might we explain the continuities and changes we find? I’m a long way from answering these questions fully, but I found some fresh and intriguing instances. One surprise is worth half a dozen confirmations.

Divas on parade

This year I concentrated on European movies. One of the most prominent genres of Italian cinema was the diva film, the movie whose dominant attraction was a beautiful, often fiery, somewhat otherworldly female star.The mesmeric charms of the genre have been celebrated in Peter Delpeut’s anthology film Diva Dolorosa, but the films really need to be seen in their entirety. The most comprehensive book on the subject is Angela Dalle Vacche’s Diva: Defiance and Passion in Early Italian Cinema, while my Wisconsin colleague Lea Jacobs has published detailed analyses of diva performance in Theatre to Cinema and here on the web.

In the 1910s, American cinema was turning out fast-paced films, but the diva films I saw provided less complex plots and remarkably protracted acting. An emblematic instance is the climax of Rapsodia Satanica (1917), starring Lyda Borelli. Alba has sold her soul to Mephisto in order to recover her youthful beauty. She toys with two men’s affections, and one kills himself (mysteriously leaving a scar on her face). The plot more or less halts.

Alba retreats into her chateau and wanders the grounds. She glides forlornly through her garden, idles at the piano keys, and drapes herself along a bridge. She strews flowers on the floor and even dresses herself up as a priestess. Most strikingly, she floats into a cluster of mirrors and drapes herself in layers of veils, creating a gauzy shroud.

Run at 16 frames per second, this cadenza of apparitions consumes nearly a minute and a half. Such an exercise in atmospherics might be considered wasteful in an American film of the time, but it enhances the expression of Alba’s late-blooming spirituality—just before Satan comes to claim his pledge.

The same sort of languid choreography can involve other players. The diva’s performance, as Jacobs has shown, is often closer to dance than to orthodox acting, and she can weave arabesques around her more or less stationary suitors. At times the diva is a virtual acrobat. If you can call a contortion graceful, we can find it in the angular wrist maneuvers of Borelli in La Donna Nuda (1914).

The diva’s divagations are usually shot from a distance, and often there are big sets that are cleared of other actors to allow the actress maximum freedom and minimum distraction.At key moments, there might be a straight cut-in to the diva in medium-shot, but the visual narration keeps our attention fixed on a single arresting figure.

This tendency varies from the sort of ensemble staging that I’ve studied in more detail in On the History of Film Style and Figures Traced in Light. The staging is based upon the diva’s decorative elaboration of her emotional states, rather than in the shifting configuration of several actors. This difference reflects a variation in pace as well: The diva’s subtle changes of expression and posture emerge gradually, but the behavior of actors in ensemble scenes tend to accelerate the flow of action and reaction.

The spotlighting of the diva was not a big surprise, perhaps, but at least a reminder that there are always several tendencies at work in film in any period. More unexpected was the opening sequence of Il Fuoco (1915), in which the heroine visits a lake for a sketching session. As she sits down, a painter arrives to do some painting of his own. There follows a sequence of fourteen shots taken from eleven camera setups, some quite close to the actors. The sequence displays the sort of orthodox continuity that we associate with American films of the same year (The Birth of a Nation, Regeneration, The Cheat).

Granted, European films of the 1910s display freer camera setups in exterior settings than in interior sets. Still, the director of Il Fuoco, Giovanni Pastrone, shows an intuitive mastery of angled shot reverse-shots and consistent eyelines. It makes me eager to see whether other European filmmakers were developing a tradition of continuity editing akin to the American one.

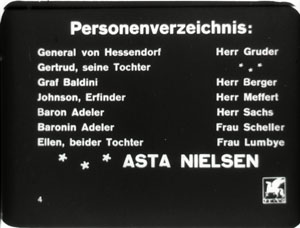

Asta Nielsen was, so to speak, a Danish-German diva. A beanpole with a long face and a slash of a mouth, she might seem an unpromising vessel for languid eroticism. Yet Die Asta became an icon of silent film after her sultry dance in Urban Gad’s Afgrunden (The Abyss, 1910) won her an international audience. In Germany she turned out a vast number of dramas and comedies, with her as undisputed main attraction. Lest we think that the term “star” is a modern one, the title card for S1 (1913) is already playing a coy game.

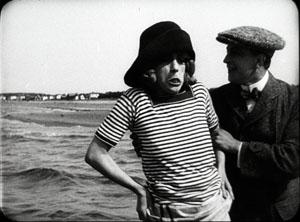

Again, with the spotlight on the heroine, the director’s decision can be simple. Evacuate the set and bring her closer to the camera, or if the set is cluttered, cut in to let Asta act.But she’s refreshingly unethereal, with changes of expression that are fleeting and unpredictable. At a lake with her lover, she flashes her legs at the camera and gives us a grin.

But a few frames later, her grimace becomes downright grotesque as she picks her way to shore. You can easily imagine her fear of losing her balance or stepping on a sharp stone.

Strong-willed and resourceful, Asta projects a wary intelligence. This, of course, doesn’t keep her from falling in love with worthless men.

Colorforms

Today’s archivists are determined to restore silent films to their original beauty, which includes the gorgeous colors achieved by tinting, toning, stencil coloring, and other techniques. Earlier this year Josh Yumibe came to our campus with a splendid collection of frames illustrating the range of possibilities. I saw several colored prints during my Brussels stay, including some original nitrate copies. Two from 1911 were films now acknowledged as “specialist classics.”

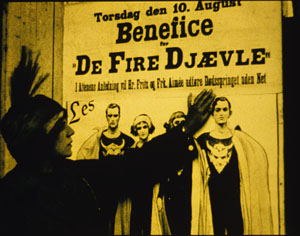

The Four Devils, directed by Robert Dinesen, is one in a cycle of circus films that was popular in Denmark at the period. A team of trapeze artists includes two men and two women; one couple has a steady romance, the other is fractured by the man’s attraction to a rich woman. Once Aimée is convinced of Fritz’s infidelity, she decides to kill him during a performance. The climactic “death leap” is rendered in about thirty shots, including one of an empty trapeze bar swinging. Under the big top, the compositions are full of detail and yet clearly laid out. And Dinesen reveals Aimée’s plan in one of the most ominous shots in silent Danish film.

Even more visually remarkable is Victorin Jasset’s Au pays de ténébres (In the Land of Shadows, 1911), a grim naturalistic drama set among coal miners. The film occasionally displays principles of depth staging that would be elaborated in some of the masterpieces of 1913. In one scene, the miners’ families gather in an anteroom. As they wait to identify the men killed in a cave-in, the bodies are barely discernible in the distance.

Au pays de ténébres illustrates a sort of structural usage of color. In scenes like the one above, the color is, in orthodox fashion, denoting a daylight interior. By contrast, the scenes in the mine are tinted blue, the standard hue for night and darkness.

But in the final scenes of the bodies assembled in the room of the dead, the color retains a blue cast, recalling the mine.

Thanks to the tinting, the living find themselves in the land of shadows.

Early auteurs

In the 1910s, we can find some distinct directorial approaches. One auteur is the German Franz Hofer, who liked to frame his actors in symmetrical architecture. Rectangular geometries are given a comic cast in Fraulein Piccolo (1915), a story about flirtatious officers and a schoolgirl forced to be both maid and bellboy. Here, two servants open doorways to watch a soldier starting to seduce the heroine.

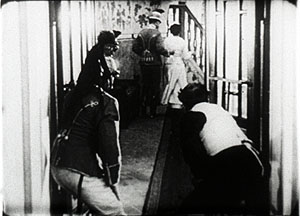

I hadn’t expected to find surprises in Henri Pouctal’s Chantecoq, a two-part French feature from 1916. Yet this espionage drama was consistently engaging, and not just because the popular comedian Pougaud played the deceptively naïve hero. Pouctal unrolls his scenes in an unusual variety of setups, including an astonishing low-angle view of two spies grappling with Chantecoq on the floor of a train compartment. The image recalls Anthony Mann’s steep railway compositions in The Tall Target.

Alfred Machin was Belgium’s preeminent director of the 1910s. He never seems to have seen a windmill he didn’t want to film, then burn down or blow up. Machin enjoyed recording Belgian folk culture, particularly village dancers, as is evident in classic one-reelers like Le Moulin maudit (The Accursed Mill, 1909), and he had a fondness for jungle cats like Mimur the leopard.

Each of the Machin features I saw shed light on my research questions. Le Diamant noir (The Black Diamond) confirmed that the European tableau style was by 1913 achieving considerable intricacy. In this film, Luc, a rich man’s secretary, is accused of stealing the daughter’s bracelet. The scene of the police interrogation is a muted ballet of figures retreating, advancing, blocking, and revealing.

The servant in the far distance returns to visibility when he’s needed to show the cops to Luc’s room.

In Machin’s La Fille de Delft (The Girl from Delft, 1914), the tableau depth cooperates with some muted cutting. Kate is a famous dancer, visited by Jef, the young shepherd who has loved her since she was a girl. In her dressing room, while stage-door roués wait to take her out for dinner, she gets a message from him.

As she lowers the note, she makes her two playboy admirers more visible; we can see them opening the window.

They peer out, and we get an over-the-shoulder shot of Jef waiting outside.

When we cut back to the master shot, the men are mocking him and Kate is deciding whether or not to admit him. She goes to the window herself and looks outside. Again we get the over-the-shoulder framing, but in two beats: Kate looking, then Kate looking away.

The poignant framing lets us linger on her moment of decision. When she closes the window, we know that she has decided to abandon her childhood friend.

Simpler in its drama and staging is Machin’s official classic, Maudite soit la guerre (Cursed Be War, 1914). Adolphe, a young man from a country suspiciously similar to Germany comes to Belgium, or a place like Belgium, to learn aviation. Adolphe falls in love with his host’s daughter Lidia, but soon war breaks out between their countries and they must part. The rest of the film, which includes some spectacular aerial scenes (and, naturally, a burning windmill), pleads for peace and brotherhood. Released in May of 1914, Machin’s anti-war film now seems a futile warning.

The Archive has restored the original’s Pathécolor, creating images of great loveliness. Some scenes show stenciled color, which helps articulate the planes of shots arrayed in depth. An example surmounts this blog entry. At other moments, deep red tinting enhances the battle scenes, notably one of an exploding dirigible.

In all, this outstanding restoration of Maudite soit la guerre reminds us of what audiences actually saw—films of deeply felt emotion, often accentuated by spectacular action like that on display today, and employing color with both intensity and delicacy.

The restorer’s art

During my stay, I particularly enjoyed the time I spent with Noël Desmet, supervisor of restorations at the Belgian Film Archive. Noël invented the most robust method of recovering silent film color. Around the world, archivists have adopted the Desmet system.

Noël is scheduled to retire in April of next year. His research will be continued by his colleagues, and he will enjoy some well-earned time among his orchids. Film culture rests upon the shoulders of committed archivists like him. Noël Desmet and his peers are the guardians of treasures, the patient preservers of the secrets and surprises harbored by the twentieth century’s most powerful art form.

For more on tableau staging in Europe and the US, see the entries linked above, as well as my notes from this summer’s visit to the Danish Film Archive, some comments on acting styles, my discussion of Charles Barr’s idea of gradation of emphasis, and an entry on hands and faces around a table. The most thorough analyses of these and other staging principles are in On the History of Film Style, Figures Traced in Light, and certain chapters of Poetics of Cinema.

For more information on Machin and Mimur, see the bilingual book edited by Eric de Kuyper, Alfred Machin Cinéaste/ Film-maker (Brussels: Royal Film Archive, 1995).The Diva Dolorosa disc contains extracts from major films, but unfortunately they aren’t specifically identified, and the original cutting patterns aren’t always respected. The difficulty with such celebratory appropriations of silent films is that they are unreliable as historical evidence. Worse, in today’s commercial market, such compilations make it unlikely that other video producers will launch complete DVD versions of the films.

Tagebuch des Dr. Hart (Dr. Hart’s Diary, Paul Leni, 1916)

PS 18 August: Thanks to Armin Jäger for a name correction!

The Bologna beat goes on

Guy Borlée, Festival Coordinator for Cinema Ritrovato, in a pas de deux with Moira Shearer.

DB here:

Like most film festivals, Cinema Ritrovato is many festivals. There’s so much on offer you can carve out your own mini-fests. You may meet a friend for lunch and learn that you two have seen none of the same movies. So here are some titles from my sampled version of Ritrovato.

1909 and a little later

Le Trust (Feuillade, 1911).

As Kristin pointed out in our last entry, we spent a lot of time in the 100 Years Ago thread. Things were definitely changing on screens in 1909. True, you still had your costume picture with suspiciously insubstantial walls and props, your gimmicky special-effects comedies (e.g., The Electric Policeman), and your chase films with people falling over and getting up and running on, endlessly.

But you also had powerful movies like Capellani’s L’Assommoir, discussed by Kristin, and charming ones like Charles Kent’s Vitagraph Midsummer Night’s Dream. There were crime films like Tell Tale Blotter and An Attempt to Smash a Bank, with its peculiar slow reverse tracking shots linking the lobby and the banker’s office. There was Cowboy Millionaire, which presents the always-edifying spectacle of a buckaroo bringing his uncouth pals to the big city. There were wonderful Film d’Art items, not least Le Retour d’Ulysse, which had the most rapid editing pace of any 1909 film I clocked. There was even a lifelong romance told through the fate of two pairs of shoes (Roman d’une bottine et d’un escarpin).

Louis Feuillade was one of the finest directors of the 1910s, but most of his earlier work that I’ve seen doesn’t suggest his mature storytelling skills. Of the 1909 Feuillades on display in Bologna, the two I found most intriguing were La Possession de l’enfant, about a divorced wife who kidnaps and raises her child in poverty, and La Bouée, a touching tale about a fisherman’s family about to lose everything. But the cherry on the sundae for me was a pristine print of a 1911 Feuillade, part of Eric de Kuyper’s program of films about financial crises. My man Louis did not fail me.

In Le Trust, a businessman indulges in a bit of corporate espionage. He hires a detective (the sinister René Navarre) to kidnap an inventor and squeeze a secret formula out of him. The detective resorts to some unusual methods, such as hiring an actor to dress in drag and impersonate a rival’s wife. The inventor is kidnapped but outwits his captors with a trick that could have come straight out of Les Vampires. The plot’s outrageous surprises are played straight and brisk, and we can see Feuillade moving toward the compact, inventive staging of Fantomas and Tih-Minh. How could Le Trust not be my favorite movie of the week?

Tsars, Commissars, and Jews

Given my fondness for Russian and Soviet film, Kinojudaica was a thread I followed fairly closely. This imaginative program, drawn from a larger package assembled by the Cinémathèque de Toulouse, ran from the 1910s to the early 1930s.

Given my fondness for Russian and Soviet film, Kinojudaica was a thread I followed fairly closely. This imaginative program, drawn from a larger package assembled by the Cinémathèque de Toulouse, ran from the 1910s to the early 1930s.

Véra Tcheberiak (1917) is probably more important for its subject matter than its fairly simple technique. The two-reel film was the third to treat a famous case of anti-semitic hysteria under the Tsar. In 1913, a Jew named Beilis was charged with ritual murder of a Christian child, and it became Russia’s Dreyfus affair.

More elegantly directed was Evgenii Bauer’s worldly, somewhat cynical Leon Drey (1915) which retains its fascination. (I wrote about its staging in an earlier entry.) But its intertitles still need to be restored.

Two later films were strongly marked by Soviet montage influence. In The Five Brides (Piat Nevest, 1929-1930), a shtetl is threatened with a pogrom by a gang of bandits. The band will spare the citizens if five virgins can be offered to their leaders. Director Aleksandr Soloviev accentuates this dramatic situation with every trick in the montage playbook: fast cutting, low angles, handheld shots, dynamic graphic conflict, and even explosions and bursting waves as Red partisans ride to the rescue. The final moments are missing, but there is plenty to savor, including an emotionally complex scene in which the elders decide to sacrifice their five virgins and suffocate a young man who is trying to stop them. The film was revised for Russian release, but we saw the original Ukrainian version.

No less engaging, though a little more formulaic, was Remember Their Faces (Zapomnite ikh litsa, 1931). A young Jewish worker devises a machine to speed the work of a tannery, but his efforts are blocked by saboteurs and anti-Semites. In a slap to the New Economic Policy, the chief villain is a private entrepreneur who wants to make the tannery uncompetitive. The scenes in which Beitchik is casually bullied by young thugs are quite strong. The final moments, when the bullies won’t even let Beitchik leave town unmolested, present the stirring image of the Komsomol youths marching to rescue him. Such support did not materialize behind the scenes: the film encountered censorship at every stage and was given a modest release.

Despite a 1927 Party directive ordering films treating anti-Semitism as a threat to socialism, both The Five Brides and Remember Their Faces encountered obstacles at every turn, largely on the grounds that the Party was given too small or too passive a role. In a fine book accompanying the series, Valérie Pozner supplies details of how the films were censored and suppressed.

Capra, company man

Donald Sosin gives us Scott Joplin’s “Wall Street Rag” (1909), uncannily appropriate today.

One of the highlights of this year’s Ritrovato was the Capra series, featuring his surviving silent work and several early sound pictures. We were also lucky to have Joe McBride, professor, critic, and UW alum, there to introduce many sessions.

I didn’t attend the talkies, having seen the batch except Rain or Shine (1930), but several of the silents grabbed my attention. Most seemed to be attempts by Columbia to hitch a ride on the bigger studios’ successes.

The Way of the Strong (1928) is a post-Underworld exercise in hoodlum redemption, graced by vigorous action, swift cutting (4.3 sec ASL by my count), and nice juggling of recurring props (mirrors, pistol barrels, a book devoted to great lovers). And the plug-ugly hero is truly ugly, none of your Hollywood fake-ugliness; a face only a blind girl could love. Submarine (1929) is a take on the What Price Glory plots analyzed by Lea Jacobs in her recent book. Two amiable sides of beef brawl and drink their way through navy life until a woman comes between them. The sexual rivalry is compelling, and the suspense during a stifling undersea rescue is admirably sustained. The Younger Generation (1929) owes something to the back-to-your-roots impulse of The Jazz Singer. Based on a Fannie Hurst story, it tells of a Jewish family that rises into society because of the son’s business acumen; in the process, class snobbery makes them increasingly unhappy.

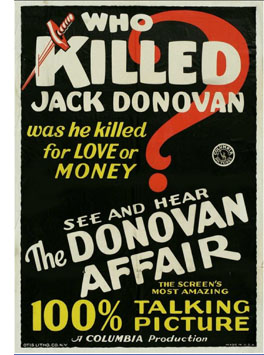

I leave aside the silent version of Rain or Shine, which I found underwhelming, so as to focus on the most curious thing I saw at the festival. The Donovan Affair is a Philovanceish murder mystery from a play by the ubiquitous Owen Davis. It was released in April 1929, and it isn’t particularly good. But it nags me.

I leave aside the silent version of Rain or Shine, which I found underwhelming, so as to focus on the most curious thing I saw at the festival. The Donovan Affair is a Philovanceish murder mystery from a play by the ubiquitous Owen Davis. It was released in April 1929, and it isn’t particularly good. But it nags me.

The movie was made in both silent and sound versions. Our print was silent, but it had no intertitles. At first blush it seemed to be the sound version without its track, sort of a 000% talking picture. The print’s average shot length is 9.3 seconds—too long for most late silents, but typical of some early talkies. Yet this did not look like any 1929 American talkie I have seen.

It had silent-film lighting, some huge lip-sync close-ups, and very smooth cutting. Except for a couple of moments, it lacked the jerky reframings, the long-lens imagery, and multiple-camera coverage typical of shooting from booths, the common practice of early talkies (and the talking sequences of The Younger Generation). Capra’s setups sat well inside the action, as was the case in 1920s silents and as would be the case in single-camera sound films a few years later.

Crazy as it sounds, I had to wonder if we were seeing a copy of the silent version made before titles were inserted! This is very unlikely. But if this was indeed an early talkie version, Capra was able to shoot sound with a fluidity that directors at bigger firms didn’t display—and in a rented studio at that, if the AFI Catalogue is to be believed. On the road and away from my research base, I can’t investigate further, but if you know more about the Donovan Affair affair, feel free to correspond and I’ll add postscripts.

Whatever the provenance of that Library of Congress print, the other silent/ early sound Capras have been admirably buffed by Sony’s Grover Crisp and Rita Belda (another Wisconsinite). The prints’ sparkle and sheen prove that even a minor-league studio (which Columbia was then) could turn out gorgeous imagery, thanks in no small part to cinematographers like Joseph Walker and Ted Tetzlaff.

Miscellany

The Lewinsky Dog surveys the climactic battle in Karadjordje (1911).

Be Patient! Department: Anke Wilkening, who was among those announcing the discovery of a new Metropolis print last year, gave us an update on the restoration process. The archivists are nearly done integrating the Argentine footage into the whole. Next comes the cleanup phase—awkward because the original Argentine print was heavily scratched and what we have is a 16mm copy and cropped for sound at that.

So far, the restored footage is clearly making secondary characters like Josaphat and the “Thin One” more prominent. But even the Argentine print is lacking things known to us, as three clips illustrated. Getting everything in some order will take time. Anke promises another report next year.

Box sets routinely attract attention at Bologna’s annual DVD awards, and this year things went according to form. The top prize went to Joris Ivens, Wereldcineast, a vast assembly of rare work by the Dutch filmmaker. Another generous package, Flicker Alley’s Douglas Fairbanks set, won best silent-film box set. (We have an entry on it.) Two more big collections, GPO Film Unit Collection vol. 2 (BFI) and Treasures from American Archives IV (Film Foundation) triumphed in the Sound Film and Avant-Garde categories.

Other winners: the two Vampyr releases (Eureka and Criterion) and Berlin, Symphony of a Big City (Munich Filmmuseum) for their rich bonus materials; Vittorio De Seta’s documentary collection Il Mondo Perduto (Feltrinelli Real) and two studies of Pasolini’s La Rabbia (Raro) in the Rediscovery category. Cinema Ritrovato wisely acknowledges that DVD producers are contributing powerfully to research into film history and are making rarities available to viewers who live far from festivals, archives, and cinematheques.

Not heralded—in fact, just sitting on the counter at the ticket booth—were still other DVDs, this time from Serbia. Sharp-eyed Olaf Müller pointed them out to me, and I’m grateful he did. Two volumes from the “Film Pioneers” series include a set of newsreels and, happily, the 1943 Innocence Unprotected (which Makavejev “decorated” in his revised version of 1968). A third disc consists of Karadjordje; or, Life and Deeds of the Immortal Duke Karadjordie (1911). This is the first Serbian and Balkan feature, and is thus, as the box text indicates, “one of a kind.” Same goes for Cinema Ritrovato itself.

Gian Luca Farinelli and Peter von Bagh, two more we have to thank for a great festival.

Just in time for Bologna, the historical journal 1895 has published a splendid special number on Le Film d’Art, ed. Alain Carou and Béatrice le Pastre. Feuillade’s Le Trust is available on the Gaumont early years DVD set and will soon be released on a Kino set drawn generously from the Gaumont collection. Keep your eyes open for early Capra features on Turner Classic Movies; several have run there recently.