Archive for the 'Silent film' Category

Bugs: The secret history

DB here:

One of the many penalties of watching movies on TV is the prevalence of bugs.

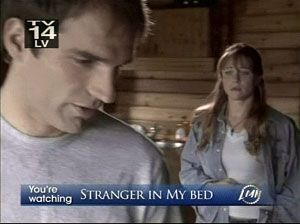

This is the nickname adopted by media makers for those little channel logos and watermarks that hop onto your screen. Sometimes these translucent signatures surface at intervals, to minimally satisfy FCC channel identification demands. Others let you know the movie you’re watching, or will be later.

But just as often the bugs just squat in a corner forever, teasing your eye away from the movie. Bugs are to the 2000s what editing and time-compressing were to earlier eras. “Movies, uncut,” boasts the IFC bug. But not unspoiled.

Bugs are bad enough when they are hovering in a black vacuum, made forlorn by letterboxing.

But they really jump into competition when they take up part of the image. How can you watch what actors are doing when there’s something faintly readable floating up from below?

I find it impossible not to look at a bug occasionally. In dark shots, sometimes it’s the most visible thing on the screen. Even in bright shots I stare at it. Maybe I’m hoping that it will be different this time. Yet when it changes, as it does on the Lifetime channel, I watch it more attentively, which only makes me more annoyed.

It’s like the mesmeric spell of Time Code, ticking away the movie’s life, and yours.

I’m not the first to complain. An eloquent manifesto, originally called Squash the Bugs, dates back to 2000, when the infestation was starting. Several other souls participated in the movement.

We know why bugs are swarming all over TV. Somebody better dressed than you or me is worried that we will be recording A Christmas Story or Smokey and the Bandit or Stranger in My Bed. We might even try to sell copies, or post a clip online. In principle, the bug is a badge of ownership, warning that we could be prosecuted. In practice, nobody expects to sue every user, so bugs help spread the brand. It’s like putting a designer logo on a shirt, making you a walking ad. Who wouldn’t want their bug, microscopic as it is, all over YouTube (which of course tacks on its own bug)?

But like everything else that we take for granted, bugs aren’t new. In their earlier form, they’re rather likable.

Silent but deadly

Movie bugs go back to the first years of cinema, when producers were no less worried about media piracy than they are today. Between 1895 and 1915, films circulated very freely around the world, and enterprising crooks happily duped originals and passed them off as their own productions. To block this, filmmakers tried to find ways to keep their trademarks on the film.

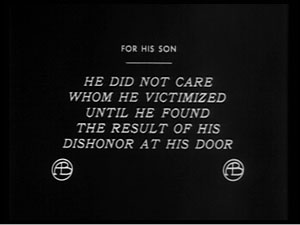

The obvious step was to put the trademark in the intertitles, and many companies did. Here is one for For His Son, a 1912 Griffith film from American Biograph. (What did the protagonist do for his son? He created a soft drink called Dopocoke, which turns the college boy into a hopeless addict.) Note the handsome AB insignia.

But of course a pirate could simply replace such original titles with ones of his own. The next logical step was to incorporate the trademark into the images, which couldn’t be replaced. Without the technology to create near-invisible superimpositions, the filmmakers took the obvious course.

They put the company logo into the set.

The AB circle typically appeared as a wall decoration. Biograph characters loved to furnish their surroundings to highlight this motif, preferring to put it at eye level and frame center. The logo could be found in unexpected places, like movie theatres (Those Awful Hats, 1908), and it could brighten the dreariest hovel (What Shall We Do with Our Old?, 1911).

The plaque’s popularity stretched back to Civil War days (In the Border States, 1910), and even in medieval times a king might mount the stylish AB on a brick wall (The Sealed Room, 1909).

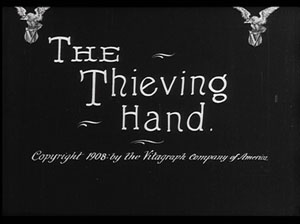

Not to be outdone, Biograph’s competitor, the Vitagraph company, had a beautiful soaring eagle logo, which conveniently furnished a striking V graphic.

Judging from the evidence of this 1908 film, however, Vitagraph had a sideline in manufacturing safes.

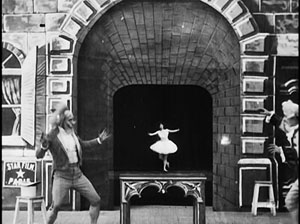

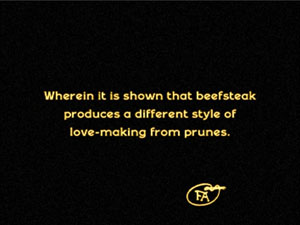

The practice of building the trademark into the mise-en-scene seems to have begun in France. Georges Méliès, whose fantasy films were popular around the world, took measures to counter piracy early. You can see his Star-Film logo on the building stone in the left corner of this frame from La Danseuse microscopique (1902). Shift it to the right corner and we’d have a modern-day bug.

At the very top of this entry is a frame from Le Voyage de Gulliver à Lilliput et chez les géants (1902). There Méliès attached the Star-Film seal to the barrel sitting just left of center.

At the very top of this entry is a frame from Le Voyage de Gulliver à Lilliput et chez les géants (1902). There Méliès attached the Star-Film seal to the barrel sitting just left of center.

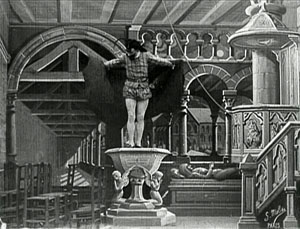

But Méliès didn’t always shove his imprimatur to the edge of the frame. In Le Tonnerre de Jupiter (1903) it sits just below the eagle that Zeus bestrides.

In the earlier Diable au convent (1899), Méliès exercised another option, simply signing his image as if it were a painting. To a large extent, it was.

Léon Gaumont had two marques, each enclosed in a chrysanthemum ring. The most famous one is a majestic Gaumont, but an alternative, ELGE (that is, LG), haunts Alice Guy’s Billet de banque (1907). First, in a café, the logo is attached to a table, and later it’s a decorative baseboard in a police station.

In Guy’s Le Frotteur (1907), Gaumont simiply stuck its logo to a chair leg.

Then there’s the Pathé Frères rooster.

Easy enough to embed that, you’d think. Just have a rooster stroll through a shot now and then—not only barnyard scenes, but ones set in a courtroom or a factory. Still, roosters are pretty accessible to any film pirate, so Pathé went the more ordinary route of weaving its logo into the set.

An insistent example comes in The Physician of the Castle (1907), possibly the source for Griffith’s The Lonely Villa (1908) and Lois Weber/ Phillips Smalley’s Suspense (1913). The plot is sort of a 1907 Panic Room. The logo is initially a plaque in the parlor of the castle, visible just behind the kneeling doctor.

An identical plaque is perched in nearly the same spot on the wall of the doctor’s own parlor, as we can tell when his family is besieged by the invading tramps.

The tramps pass through another room, where the trademark stands proudly on another wall, on screen right.

And when the wife tries to phone the husband for help, we get an insert that shows the Pathé cock nearly perched on her shoulder.

Why do I find the old bugs charming and the new ones annoying? I suppose it’s partly because the old ones were hand-crafted, not the result of keyboard twiddling. They are tangible. They are part of the scene’s space. Hard to see on DVD, the embedded marques are striking in 35mm projection, and spotting them is part of the pleasure of early film. Moreover, the filmmakers intended them to be there, or at least they accepted the need for them. But what director today is happy when the Sundance bug creeps into her compositions?

The old bugs seem to have gone extinct around 1912, but they will cling to their films. They bear witness to filmmaking of a specific time, and they anticipate problems that persist today. In tackling the threat of piracy, the old bugs seem at once naïve and intelligent. I see them as a rational solution to a hard problem, narrative consistency be damned. Today’s bugs, floating on top of the story world, seem more like corporate tattoos or graffiti. They don’t exist within the action, so you could argue that they are less disruptive. But they become a different sort of distraction, hovering halfway between the story world and the space of viewing. Bugs are spectres haunting the film.

On rare occasions, a modern add-on can be appropriate. In a Méliès film on the recent Flicker Alley set, L’Oracle de Delphes (1903), some TV agency has clapped its own digital bug into the lower right corner. It really is about beetle-size, and it dares to be a single eye looking back at you. That icon adds a touch of peculiarity not out of keeping with the Méliès aesthetic.

You can argue that this smirch on the image is a minor sacrilege. But I suspect that the Master of Montreuil would have grinned in approval.

For more on bugs, aka DOGS (Digital Onscreen Graphics), see Wikipedia. Thanks to Jason Mittell for helping me name these pests. And all hail Turner Classic Movies for keeping its bugs to a minimum.

The Sunbeam (Griffith, American Biograph, 1912).

PS 19 January 2009: “Subliminal” bugs: I had hoped to include a frame illustrating the anti-piracy stamp used on current 35mm releases, but couldn’t find one quickly. This mark consists of a tight pattern of dots resembling a character in Braille. The stamp would presumably be copied if someone shot off the screen or ran the film through a telecine. How effective these bugs are at tracing pirate copies I can’t say, but you can detect them, especially in bright scenes; I usually notice one every third reel or so, just left of the center of the frame. I’ll keep looking for a frame and try to add one to this entry.

John Powers alerted me to the fact that even Michael Snow’s Région Centrale got the bug treatment when it was telecast on Italy’s RAI 3 TV. Thanks to John for this scary example.

P.P.S. 24 January 2009: On the Internets, ask and ye shall receive. Olli Sulopuisto wrote to link me to the Wikipedia entry explaining the domino dots, known as CAPs. The entry includes an illustration. Olli also contributed to Jim Emerson‘s scanners blog, which contains good commentary on CAPs from Jim and his readers.

P.P.P.S. 29 May 2013: Can anti-piracy bugs be integrated into the movie or TV show? Yes!

The ten best films of . . . 1918

Kristin here–

We ended 2007 with a salute to the 90th anniversary of the solidification of the classical Hollywood filmmaking system. 1917 was not only the year when all the guidelines—continuity editing, three-point lighting, and unified story structure—gelled in American cinema. It was also one of those years (like 1913, 1927, and 1939) when a burst of creativity took place internationally. For those years, it’s hard to keep one’s greats list to ten.

Enough of you enjoyed that entry that we thought we would come up with another list to end 2008. For some reason, 1918 doesn’t yield the plethora of great films that obviously should go on such a list. Maybe it’s the sheer accident of preservation. After a string of masterpieces from Douglas Fairbanks in 1917, there seems to be a dearth of his films extant from the following year. Some filmmakers, like Cecil B. De Mille, simply released fewer films in 1918. And of course, some masterpieces may still lie gathering dust on archive shelves, waiting to be discovered.

Still, great films were made that year, some familiar—some that should be better known. Some are available on DVD, and some are excellent candidates for release by some of the enterprising companies like Kino International, Image Entertainment, and Flicker Alley.

1. The list isn’t in rank order, but for me the outstanding film of 1918 is Berg-Ejvind och hans hustru, better known to most as The Outlaw and His Wife, by Victor Sjöström. This tale of an enduring love between a man  hunted by the police and a rich landowner who falls in love with him, and, as one title says, “Hearth and home and every man’s respect—she gave it all up for his sake.” The result is one of the cinema’s great romances as the pair flees to the mountains and spend the rest of their lives amidst the natural landscapes that create spectacular backdrops for the action.

hunted by the police and a rich landowner who falls in love with him, and, as one title says, “Hearth and home and every man’s respect—she gave it all up for his sake.” The result is one of the cinema’s great romances as the pair flees to the mountains and spend the rest of their lives amidst the natural landscapes that create spectacular backdrops for the action.

This year Kino also brought out a disc with the dynamite double bill of two tragedies Ingeborg Holm (1913) and Terje Vigen (1916). David and I have both written about the staging in Ingeborg Holm, and David has had much to say on tableau staging in 1910s cinema. Watch these three films, and you will understand why we consider Sjöström perhaps the great director of the decade. It’s a shame that more of his films are not available yet in the U.S. Buy copies of these, and maybe Kino will bring more of them out.

2. Another master of this era, Louis Feuillade, made a sequel to his Judex (1916): La Nouvelle Mission de Judex. David discusses both in the second chapter of his Figures Traced in Light. Although Judex is available on DVD, so far the second serial is not.

3. I suspect that Hearts of the World is one of those D. W. Griffith features that a lot of film enthusiasts have heard of but not seen. Remarkably, it’s not available on DVD. (Keep your old laserdisc if you’ve got one!) I have to admit, it’s not one of my favorite Griffiths, though it does have a charming performance by Dorothy Gish and contains scenes that were actually shot near the front lines in France.

4. Ernst Lubitsch was making the transition from shorts to features in 1917 and 1918. While Carmen is historically important for his development toward his mature style, most audiences these days would probably find Ich möchte kein Mann sein (“I don’t want to be a man”) more entertaining. It’s a comedy about an independent young lady who escapes her strict governess and guardian by going out on the town disguised as a man—in the process joining her guardian without his recognizing her (see the frame at the bottom). Its star, Ossi Oswalda, was an outgoing blonde dynamo, quite different from Pola Negri, whom Lubitsch turned to for his later historical epics.

Kino has made several of Lubitsch’s films from the late 1910s and early 1920s available. Ich möchte kein Mann sein can be bought on a single disc with Die Austerinprinzessin (“The Oyster Princess,” 1919), another Oswalda comedy. I’d recommend getting it as part of the larger “Lubitsch in Berlin” set, which also includes the hilariously imaginative Die Puppe (“The Doll,” 1919), the Expressionist satire Die Bergkatze (“The Wildcat,” with Negri in her one comic role for Lubitsch, 1921), an Arabian-nights epic Sumurun (1920), and the historical epic Anna Boleyn (1921), as well as a documentary on Lubitsch.

5. In 1918 Cecil B. De Mille made a film that would change his career’s trajectory: Old Wives for New. At the  time, this romantic drama that seemed risqué in its casual depiction of adultery, golddiggers, and especially divorce as creating a happy outcome. Up to that point De Mille had been working in a whole range of genres, creating imaginative films that helped define the classical style. The success of Old Wives for New led him to specialize in spicy romances known for their haute couture costumes. The film is available on a disc from Image that includes De Mille’s other major film of 1918, The Whispering Chorus.

time, this romantic drama that seemed risqué in its casual depiction of adultery, golddiggers, and especially divorce as creating a happy outcome. Up to that point De Mille had been working in a whole range of genres, creating imaginative films that helped define the classical style. The success of Old Wives for New led him to specialize in spicy romances known for their haute couture costumes. The film is available on a disc from Image that includes De Mille’s other major film of 1918, The Whispering Chorus.

6. Hell Bent, by John Ford, was long thought to be among his many lost westerns from the early years of his career. It was rediscovered in the Czechoslovakian archive and shown years ago in Pordenone at the Il Giornate del Cinema Muto festival. I must confess that I don’t remember it very well, apart from one spectacular tilt downwards as a stagecoach (?) races down a winding mountain road. Not as good as Straight Shooting, and Hell Bent survives in rocky shape (perhaps too much so for DVD release), but Ford films of this era are so rare that I’ve listed this one.

7. Like Lubitsch, in the late 1910s Charlie Chaplin was making a gradual transition from shorts to features. In 1916 and 1917 he released a remarkable string of Mutual two-reelers, from The Rink (December 1916) to The Adventurer (October 1917). In 1918, with A Dog’s Life and Shoulder Arms, he increased the films’ length to three reels, or roughly 45 minutes, and started releasing through First National. He also cut back on the number of titles released each year. Apart from a brief promotional film for war bonds, A Dog’s Life and Shoulder Arms were his only 1918 releases. Which is better? I suppose most people would say Shoulder Arms. To me it’s a toss-up.

8. David and I started attending Il Giornate del Cinema Muto in 1986, when the festival was launching its great series of national retrospectives. In quick succession, these retrospectives revealed three hitherto virtually unknown but major auteurs of the 1910s: the Swede, Georg af Klercker, in 1986; the Russian, Evgeni Bauer, in 1989; and the German Franz Hofer, in 1990. Bauer’s career ended with his death in 1917. Hofer remained active until the early 1930s. The Giornate’s German program contained only six of his films, however, and those from the 1913-1915 period. I suspect that means the later teens titles are lost.

In contrast, nearly all of af Klercker’s films survive, mostly in the original negatives. The prints shown at Pordenone were stunning. The director had a great eye for settings, using beaded curtains, mirrors, and other elements to considerable effect. He made three films in 1918: Fyrvaktarens dotter, Nobelpristagaren,Nattliga toner, the first two of which were shown in the 1986 retrospective.

Unfortunately since then the films have not been made widely available, either in prints or on DVD. Having not seen the two titles just mentioned since 1986, I can’t say that I remember them well enough to judge between them. So I’ll just leave all three films here, along with the advice to seize any chance you may get to see those or af Klercker’s other films.

(Given how little known af Klercker’s work is outside Sweden, I should point out a major English-language piece on the director’s style, Astrid Söderbergh Widding’s “Towards Classical Narration? Georg af Klercker in Context,” in editors John Fullerton and Jan Olsson’s Nordic Explorations: Film Before 1930 [Sydney: John Libbey, 1999].)

9. Stella Maris, directed by Marshall Neilan, was the first of five features Mary Pickford starred in in 1918. Its reputation lies mainly in the fact that Pickford played a double role, the bed-bound but lovely title character, and an ugly, slightly deformed orphan. In its outline, the story sounds abstract and overly symmetrical. Stella Maris’s relatives shut her off from all ugliness in the world, keeping her in happy innocence well into her teens. Unity, the orphan, has known nothing but deprivation. As Stella comes to glimpse the grim side of life, Unity is adopted and has glimpses of the beauties enjoyed by the rich. Both become miserable as a result.

The overall implication is pretty grim. Stella’s world is initially wonderful only because everyone lies to her. She becomes embittered when she finally discovers this. At the heart of the tale is the deception that life is beautiful. Unity, who has not been deceived, knows better from the start. Even one brief reference to the war, as a troupe of soldiers passes by the estate where Stella lives, makes it seem tragic—this in a film that came out about two months after the U.S. had entered World War I.

The balance between the two characters is made less artificial than it might sound by Pickford’s extraordinary performance—not so much as Stella, who is a rather passive version of the typical Pickford persona, but as Unity. The waif’s frequent disappointments and outright suffering create a strong effect that shadows even the quasi-happy ending. It’s a beautifully made film as well, with the use of glamorous backlight (as in the image at the top of this entry). Stella Maris is available on DVD from Image.

10. I have been hard put to find a feature to round out the list, so I’m substituting a group of shorts. They’re not masterpieces by any means, but each displays the talents of a great silent comic well on the way toward his most fruitful period.

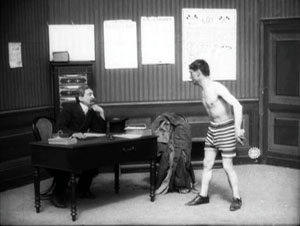

There’s no single great film to mark Harold Lloyd’s transition, but during 1918 he was developing his “glasses” character. He had had a modest success with his “Lonesome Luke” series from 1915 to 1917, where he essentially created a variant of Chaplin. In September, 1917, Lloyd first wore his famous black, lens-less glasses in Over the Fence. His early one-reelers wearing those glasses were still sheer slapstick, with little of the characterization that he would later develop to go with his new look. Arguably it was 1919 or even 1920 before he had fully nailed that persona. Still, during 1918 one can see him groping toward the formula.

Kino’s “The Harold Lloyd Collection” volumes contain four films from that year, all co-starring Lloyd’s  regular co-stars, Snub Pollard and Bebe Daniels. The Non Stop Kid (the title on the film; filmographies mistakenly give it as The Non-Stop Kid; May 21), Two-Gun Gussie (May 19), The City Slicker (June 2, all three on volume 2), and Are Crooks Dishonest? (June 23, on volume 1). The development clearly came in fits and starts. Two-Gun Gussie and Are Crooks Dishonest? are both slapstick affairs involving tricks and mistaken identify. The Non Stop Kid, though, has Lloyd in a more familiar situation, using his wits to foil a crowd of suitors and win the heroine’s hand. The City Slicker has a similar feel to it, though unfortunately the end is missing. The Non Stop Kid also has Lloyd donning a disguise in the form of a false moustache that somewhat resembles the one he had worn as Luke. This scene has a startling effect, blending the glasses character and the Luke character.

regular co-stars, Snub Pollard and Bebe Daniels. The Non Stop Kid (the title on the film; filmographies mistakenly give it as The Non-Stop Kid; May 21), Two-Gun Gussie (May 19), The City Slicker (June 2, all three on volume 2), and Are Crooks Dishonest? (June 23, on volume 1). The development clearly came in fits and starts. Two-Gun Gussie and Are Crooks Dishonest? are both slapstick affairs involving tricks and mistaken identify. The Non Stop Kid, though, has Lloyd in a more familiar situation, using his wits to foil a crowd of suitors and win the heroine’s hand. The City Slicker has a similar feel to it, though unfortunately the end is missing. The Non Stop Kid also has Lloyd donning a disguise in the form of a false moustache that somewhat resembles the one he had worn as Luke. This scene has a startling effect, blending the glasses character and the Luke character.

1917 and 1918 formed the high point of the string of comic shorts directed by Fatty Arbuckle, in which he also co-starred with Buster Keaton and Al St. John. When Keaton went solo, he proved to be a far better director than Arbuckle. Arbuckle tended to simply face his camera perpendicularly toward the back of the set for every shot, just cutting to whatever scale of framing would best display a gag. Here it’s the perfectly timed and executed gags that dazzle, and the films are often hilarious. In 1918, the team made The Bell Boy, Moonshine, Out West, Good Night Nurse, and The Cook. The latter shows off Arbuckle and Keaton’s dexterity at juggling props and Fatty’s surprising grace, as when he improvises a Salome dance with a head of lettuce standing in for that of John the Baptist!

The 13 surviving Arbuckle-Keaton films (some with missing bits) are available on Eureka’s definitive boxed set, “Buster Keaton: The Complete Short Films.” (That’s Region 2 format only, and available from Amazon UK.) Image’s “The Best Arbuckle Keaton Collection” has 12 films, missing only the more recently rediscovered The Cook. Image brought out The Cook on a disc with Arbuckle’s A Reckless Romeo (1917, sans Keaton). Kino’s two separately available volumes of “Arbuckle & Keaton” (here and here) contain 10 shorts total, again missing The Cook.

Apart from all these films, it’s worth noting that in the world of animation, 1918 saw the release of Winsor McCay’s fourth cartoon, The Sinking of the Lusitania, and Dave Fleischer’s first, Out of the Inkwell, which launched the enduring series.

Next year, 1919. Happy 2009 to all our readers!

Preserving two masters

Kristin here—

This past weekend the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s Cinematheque played host to Stefan Drössler, the head of the Filmmuseum in Munich. The Filmmuseum is a major force in film restoration, and on Saturday we were treated to a much longer print of Ernst Lubitsch’s 1922 epic, Das Weib des Pharao, than had previously been available.

Lubitsch on the verge of going Hollywood

This restoration came too late for me to see it before my book on the director’s silent features, Herr Lubitsch Goes to Hollywood (2005), was published. Not that that was a problem. I was dealing largely with style in that book, and the old version furnished plenty of examples to support my point. I argued that Das Weib was a turning point in Lubitsch’s career. It was the first film he made after the German ban on film imports was lifted and he was able to see recent Hollywood films for the first time since the war. It was also made with American financing, offering him the chance to work with American cameras and lighting equipment—an opportunity that gave him much more stylistic flexibility.

As a result, Lubitsch goes from using mostly flat, frontal light to employing the recently developed three-point lighting system. The frame above shows a very Hollywood-style lighting layout, and that’s fairly typical of this film.

Of course, it was a treat to see the film with so much new material. As I recall, the old version ran about 40 minutes, while this one is 110 minutes. There’s still footage missing, replaced in this print by still photographs and summary intertitles. Still, the plot makes a lot more sense. For the most part, the visual quality is better. The restoration depended on footage supplied by a number of archives, however, and the occasional inferior shot indicates that a less well-preserved print had to be used as source material.

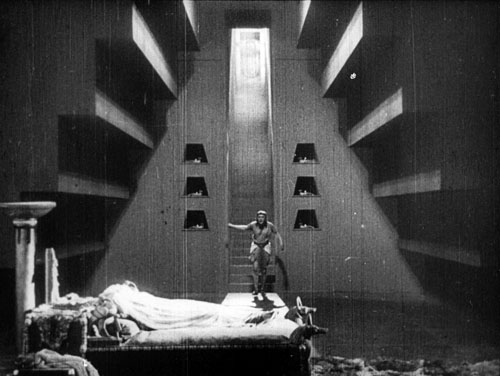

The story, set in ancient Egypt, is rather clichéd and the characters little more than ciphers. The interest lies mainly in the style and the majestic scale of the production. Given a much larger budget than usual and a longer shooting schedule, Lubitsch distinctly outdid his own earlier historical dramas, Madame Dubarry (1919) and Anna Boleyn (1921). Reportedly 8000 extras participated in the battle and crowd scenes, and the sets were erected on a colossal scale. Designer Ernst Stern was a serious Egyptology buff, and despite occasional lapses, the sets, props, and hieroglyphs are a lot more authentic than those in most movies set in this era. The film’s cast also includes a remarkable line-up of some of the most prominent actors of its day: Paul Wegener, Albert Bassermann, Harry Liedtke, and Emil Jannings (above).

Perhaps, as happened recently with Metropolis, a new, complete version of Das Weib des Pharao will someday be found. As Stefan said, however, more footage from Lubitsch’s last German film, Die Flamme (1922) would be even more welcome. An intimate drama starring Pola Negri, it survives in only one tantalizing reel. That footage reveals the director’s rapidly growing grasp of continuity editing as well as three-point lighting. Clearly he was ready to make the move to Hollywood and to even further development as a filmmaker. (My own dream film to be rediscovered would be Kiss Me Again, a completely lost 1925 Warner Bros. feature. Odds are pretty good that the one film Lubitsch made between The Marriage Circle and Lady Windermere’s Fan would be a masterpiece.)

A new Walter Ruttmann DVD

Seeing a 35mm print of such a restoration well projected is the ideal, of course, especially with an expert pianist like the Cinematheque’s David Drazin providing the accompaniment. For those who can’t get to such screenings or who want to study its restorations, the Filmmuseum also makes many of its restorations, as well as art and avant-garde films, available on DVD.

Stefan gave us a copy of one of the latest of these, a Walther (or Walter, as he sometimes spelled it) Ruttmann disc entitled “Berlin, die Sinfonie der Grossstadt & Melodie der Welt.” Actually, that’s a bit misleading, since the DVD actually contains a great deal more than those two features. All of Ruttmann’s surviving films up to 1931 are included. He was on the forefront of abstract animation, and the full series, Lichtspiel Opus I (1921), Opus II (1922), Opus III (1924), and Opus IV (1925), is included here. All have musical accompaniment, including Hanns Eisler’s 1927 score for Opus III. (That’s a frame from Opus I on the left.)

Stefan gave us a copy of one of the latest of these, a Walther (or Walter, as he sometimes spelled it) Ruttmann disc entitled “Berlin, die Sinfonie der Grossstadt & Melodie der Welt.” Actually, that’s a bit misleading, since the DVD actually contains a great deal more than those two features. All of Ruttmann’s surviving films up to 1931 are included. He was on the forefront of abstract animation, and the full series, Lichtspiel Opus I (1921), Opus II (1922), Opus III (1924), and Opus IV (1925), is included here. All have musical accompaniment, including Hanns Eisler’s 1927 score for Opus III. (That’s a frame from Opus I on the left.)

In addition, there’s a group of charming advertising films, all animated. These tend to be abstract and only bring in the product near the end. In doing the short for Excelsior tires, however, Ruttmann obviously found a round, nearly abstract shape that he could play with. A  tire rolls around in a flat landscape, having adventures that include going up and down the Excelsior factory smokestack and being threatened by spiky shapes that fail to puncture it.

tire rolls around in a flat landscape, having adventures that include going up and down the Excelsior factory smokestack and being threatened by spiky shapes that fail to puncture it.

Apart from these shorts, the two-disc set includes as bonuses a series of 22 paintings and drawings by Ruttmann, a number of texts by and about him, photographs, and so on. There’s also a CD-ROM section with additional documentation, plus a small booklet.

The two features are restorations. If you’ve only seen Berlin on a mediocre 16mm copy, this version should be a revelation. Its visual quality is gorgeous, and it has the original Edmund Meisel score, well played and well synched. The “symphony” aspect of the film makes a lot more sense with this accompaniment.

Melodie der Welt is credited with being the first German sound feature. It’s a lot simpler than Berlin. Financed  by a steamship company, it purports to follow a sailor on a huge liner around the world to exotic countries. Ruttmann takes footage from English, Greek, Japanese, and other cultures and cuts them together by topic to emphasize the similarities. Religious ceremonies are compared, military exercises intercut, children’s games assembled into a montage, people playing music (right), and so on. The laudable goal is to make customs of “exotic” peoples seem less remote and strange by showing them doing things that are not all that different from what Europeans do. A pity this was happening just before the Nazis sought to eradicate such notions of universal humanity.

by a steamship company, it purports to follow a sailor on a huge liner around the world to exotic countries. Ruttmann takes footage from English, Greek, Japanese, and other cultures and cuts them together by topic to emphasize the similarities. Religious ceremonies are compared, military exercises intercut, children’s games assembled into a montage, people playing music (right), and so on. The laudable goal is to make customs of “exotic” peoples seem less remote and strange by showing them doing things that are not all that different from what Europeans do. A pity this was happening just before the Nazis sought to eradicate such notions of universal humanity.

This set is just about ideal as a presentation of Ruttmann’s work in this period. I hope that someday a print of his 1933 fiction feature, Acciaio, will become available. It was made in Italy, and although it has been many years since I’ve seen it, I remember it as a very good film with spectacular documentary-style scenes shot in a steel mill—and as a forerunner of Neorealism.

David and I look forward to seeing Stefan at next summer’s Il Cinema Ritrovato festival in Bologna and to whatever new treasures he and his fellow archivists have restored.

His majesty the American, leaping for the moon

DB here:

Douglas Fairbanks is remembered today as the nimble, insouciant hero of a string of swashbuckling films: The Mark of Zorro (1920), The Three Musketeers (1921), Robin Hood (1922), The Thief of Baghdad (1924), Don Q Son of Zorro (1925), and The Black Pirate (1926). He is the primary subject of a gorgeously illustrated, solidly researched new biography by Jeffrey Vance with Tony Maietta. Proceeding film by film, the authors interweave his life story with production data and summaries of critical reception. While tracing his career, they make an intriguing case that Fairbanks’ 1920s features more or less founded the modern film of action and adventure.

Douglas Fairbanks is remembered today as the nimble, insouciant hero of a string of swashbuckling films: The Mark of Zorro (1920), The Three Musketeers (1921), Robin Hood (1922), The Thief of Baghdad (1924), Don Q Son of Zorro (1925), and The Black Pirate (1926). He is the primary subject of a gorgeously illustrated, solidly researched new biography by Jeffrey Vance with Tony Maietta. Proceeding film by film, the authors interweave his life story with production data and summaries of critical reception. While tracing his career, they make an intriguing case that Fairbanks’ 1920s features more or less founded the modern film of action and adventure.

In the five years before The Mark of Zorro, Fairbanks made twenty-nine features and shorts. Vance and Maietta are enlightening on this period, but they treat it as prologue to the more spectacular work. Now, as if to counterbalance their book, comes a new Flicker Alley DVD collection, Douglas Fairbanks: A Modern Musketeer, gathering ten of the early films along with a very pretty copy of The Mark of Zorro and Fairbanks’ last modern-day movie, The Nut (1921), made because he wasn’t sure that Zorro would be a hit. (It was.) To the DVD package Vance and Maietta have contributed an informative booklet and they offer enlightening conversation in a commentary track for A Modern Musketeer (1917).

Kristin and I have long been fans of the pre-Zorro titles. Kristin wrote an appreciation of the early films for a Pordenone catalogue, and I studied Wild and Woolly (1917) as an early prototype of Hollywood narration. (1) There’s no denying that the 1920s costume pictures offer dashing spectacle and derring-do. But the 1915-1920 films are something special—lively, lilting, and unexpectedly peculiar. (2)

Kristin and I have long been fans of the pre-Zorro titles. Kristin wrote an appreciation of the early films for a Pordenone catalogue, and I studied Wild and Woolly (1917) as an early prototype of Hollywood narration. (1) There’s no denying that the 1920s costume pictures offer dashing spectacle and derring-do. But the 1915-1920 films are something special—lively, lilting, and unexpectedly peculiar. (2)

Before he became Fairbanks, he was Doug, the relentlessly cheerful American optimist. This star image was created very quickly, in films and in public events that made him seem the nicest guy in the country. His manic energy came to incarnate the new pace of American cinema, and his films helped shape the emerging precepts of Hollywood storytelling.

Doug

Consider his contemporaries. William S. Hart keeps his distance; perhaps his severe remoteness comes from secret pain. The result is a man you respect and admire but can hardly love. Mary Pickford, though, is lovable, and so is Chapin, although his cruel streak complicates things. But Doug is quintessentially likable. His early films present us with a brash youth who is all pep and pluck, bouncing with barely contained energy, unselfconscious in his engulfing enthusiasm for life. Today he could be elected President, the ultimate guy to have a beer with. (In real life Fairbanks was a teetotaler.)

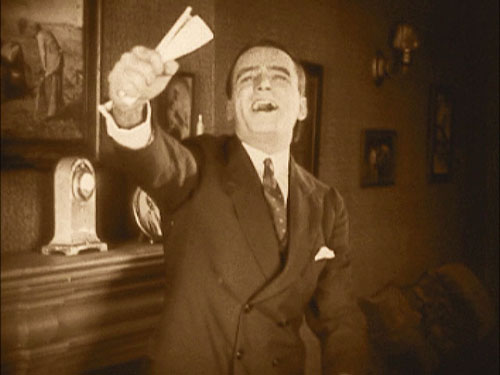

There is no guile in him, no hidden agenda. When he’s brimming with delight, as he often is, he flings his arms out wide. In another actor this would be hamminess, but for Doug it’s simply an effort to embrace the world. Any social embarrassments he commits—and they are plenty—he acknowledges with a puzzled frown before flicking on an incandescent grin. Who else makes movies with titles like The Habit of Happiness (1916) and He Comes Up Smiling (1918)?

There is no guile in him, no hidden agenda. When he’s brimming with delight, as he often is, he flings his arms out wide. In another actor this would be hamminess, but for Doug it’s simply an effort to embrace the world. Any social embarrassments he commits—and they are plenty—he acknowledges with a puzzled frown before flicking on an incandescent grin. Who else makes movies with titles like The Habit of Happiness (1916) and He Comes Up Smiling (1918)?

But how can such a genial fellow yield any drama? Give him an idée fixe, a cockeyed hobby or life philosophy into which he can pour his adrenaline. Now add a goal, something that his obsession blocks or unexpectedly helps him attain. Toss in the staples of romantic comedy: a good-humored maiden uncertain how to tame this creature of nature, a few old fogeys, some unscrupulous rivals. Hardened crooks may make an appearance as well. Be sure to include some tables, chairs, sofas, or horses for him to vault over, as well as some perches near the ceiling or on the roof; Doug feels most comfortable lounging high up. Add windows, for his inevitable defenestration. (In a poem about him, Jean Epstein wrote, “Windows are the only doors.”) There should also be chases. Other comedy stars run because they must. Doug’s joy in flat-out sprinting suggests that he welcomes the chance to flush a little hyperactivity out of his system. At the story’s climax he must save the day, taming his obsession and achieving his purpose while acceding to the claims of the practical world.

An early example is His Picture in the Papers (1916). In this satire on vegetarianism and the American lust for publicity, Doug works for his father’s health-food firm, even though he prefers thick steaks. But he’s full of ideas for promoting the product. Doug needs money to marry his equally carnivorous girlfriend, but his father will give him the dough only if Doug can pitch their line of dietary supplements. Doug vows to get his picture in every newspaper in town. While he launches a series of high-profile stunts—wrecking his car, entering a prizefight, brawling on an Atlantic City beach—his sweetheart’s father is pursued by a gang called the Weazels, who try to extort money from him.

The two plotlines converge, with Doug stopping a train wreck and winning a place on the front pages. (In a sly dig at the press, each news story contradicts the others.) The movie is a little disjointed, but several scenes are remarkable, not least a boxing match in an actual athletic club before an audience of cheering Fairbanks pals. And there is more than one funny framing, notably a nice planimetric one showing all our principals lined up and reading different newspapers celebrating Doug’s triumph.

As the title indicates, in The Matrimaniac (1916) Doug’s goal is elopement, which he pursues obsessively. He evades a rival suitor, his girlfriend’s father, a sheriff, and a posse of city officials in order to tie the knot in a gag that must have looked radically up-to-date. Reaching for the Moon gives us a more philosophical Doug, a naive disciple of self-help books that urge him to strive, to concentrate, and above all to keep his eye on the most supreme goal he can imagine. He ends up in New Jersey.

Wild and Woolly (1917) casts Doug as the son of a railroad tycoon. Although he lives in Manhattan, he dreams of being a cowboy. His bedroom boasts a teepee, and he practices his roping skills on the butler. Sent out to Bitter Creek to investigate a deal, he encounters the rugged frontier of his dreams, complete with shootouts, town dances, and hard-drinking cowpokes. But all of this is a show, staged by the locals to make him look favorably on a railroad spur. In another twist, a crooked Indian agent uses the charade to rob the bank and stir up an Indian settlement. Now Doug’s obsessions prove really useful, as his cowboy skills rescue the town.

Wild and Woolly is among the very best of the surviving early Fairbanks titles, and its adroit storytelling is still admirable today. The best-known version was a very poor print, salvaged from the Czech archives and still circulating on barely visible VHS and public-domain DVD copies. Forget those. On the Flicker Alley collection the image quality, while not perfect, allows this trim little masterpiece to be appreciated. (3)

“Always chivalrous, always misunderstood,” reads one intertitle in another gem, A Modern Musketeer. Here Doug is possessed by the spirit of D’Artagnan, simply because while he was in the womb his mother was reading The Three Musketeers. He manages to live up to his heritage as he overcomes a philandering rival and a bloodthirsty Indian. The climactic chase takes place at the Grand Canyon, affording Doug a chance to shinny up and down cliffs and do handstands along a precipice.

Doug never does things by halves. In Flirting with Fate, he is a starving artist, out of money and apparently unloved by his girl. The logical solution is to hire a killer to end his misery. Of course Doug’s fortunes instantly change, and life becomes worth living, but then he must somehow find his assassin and call off the hit.

Many of the early films show the protagonist fully formed as a cross between a cheerleader and a track star. But Fairbanks made a big success on stage playing a sissy. The task in such a plot is to turn him into a red-blooded man. His first film, The Lamb replayed this lamb-into-lion plot, which also served as the basis for Buster Keaton’s first feature, The Saphead (1920).

In the Flicker Alley collection, this strain of Doug’s work is represented by The Mollycoddle (1920). Doug is the descendant of hard-bitten westerners, but growing up in England has made him a fop. Coming to America with a batch of wealthy Yanks, he is a continual figure of fun, waving his monocle and cigarette holder. Once in Arizona, however, he’s confronted with a diamond-smuggling racket. He starts to channel his ancestors and turns into a hell-for-leather hero. He allies with a tribe of exploited Indians to capture the gang, in the process indulging in leaps, falls, canyon-scaling, and fistfights in raging rapids.

The titles often invoke craziness, vide the Matrimaniac, The Nut, and Manhattan Madness (1916). But this motif is carried to an extreme in one of the strangest pictures of the still-emerging Hollywood cinema. When the Clouds Roll By (1919) crams in enough gimmicks for three Doug stories. First, our hero is neurotically superstitious. He will climb over a building to avoid letting a black cat cross his path. He meets a girl who is as superstitious as he is, so after a session at the Ouija board, they seem a good match.

At the same time, however, a psychiatrist is making Doug the subject of a demonic experiment: Can one drive a person to madness and suicide? Through bribes and surveillance, Dr. Metz turns Doug’s life into hell—botching his romance, getting him disowned by his father, and even inducing nightmares. As if all this weren’t enough, the last reel jams in a train crash, a bursting dam, and a flood. Before this overwhelming climax, When the Clouds Roll By isn’t so much funny as eerily paranoiac. The way Dr. Metz’s Mabuse-like scheme enfolds everyone is as anxiety-provoking as anything in a film noir. This dreamlike movie ends on a surrealist note: Doug and his sweetheart get married when flood waters carry a church past them.

At the same time, however, a psychiatrist is making Doug the subject of a demonic experiment: Can one drive a person to madness and suicide? Through bribes and surveillance, Dr. Metz turns Doug’s life into hell—botching his romance, getting him disowned by his father, and even inducing nightmares. As if all this weren’t enough, the last reel jams in a train crash, a bursting dam, and a flood. Before this overwhelming climax, When the Clouds Roll By isn’t so much funny as eerily paranoiac. The way Dr. Metz’s Mabuse-like scheme enfolds everyone is as anxiety-provoking as anything in a film noir. This dreamlike movie ends on a surrealist note: Doug and his sweetheart get married when flood waters carry a church past them.

Across these films, in fact, the Fairbanks persona starts to disintegrate. Somewhat like those naïve Capra heroes of the 1930s (Mr. Deeds, Mr. Smith) who turn into melancholy victims in Meet John Doe and It’s a Wonderful Life, Doug becomes more brooding and helpless. In Reaching for the Moon, his absurd dream of glory is revealed as just that, a dream. When the Clouds Roll By saves itself from despair through splashy last-minute rescues.

Fairbanks was evidently becoming uncomfortable in cosmopolitan comedy. His taste for large-scale stunts and tests of prowess led him to the costume sagas of the 1920s. In the process, as Vance and Maietta point out, he cleared the way for Keaton and Harold Lloyd. Both comics would sometimes play obtuse idlers in the Lamb mode, and both would take thrill comedy to new heights. But avoiding Fairbanks’ ebullient optimism, Keaton brought a perplexity to every situation, along with an angular athleticism and a geometrical conception of plotting and shot composition. Lloyd frankly presented a hero lacking social intelligence, afflicted with a stammer or shyness or even cowardice, always desperate to fit in. Both men deepened the possibilities of modern-day comedy, thriving in the niche vacated by Fairbanks.

Bug and Mr. E

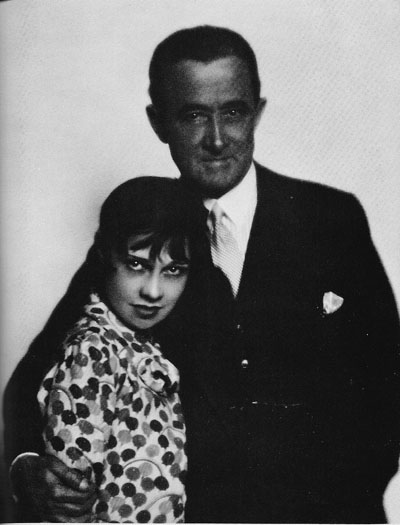

For nine of the early films, Fairbanks had the help of John Emerson and Anita Loos. All three worked on the stories, with Emerson usually directing and Loos writing the scripts and intertitles. The collaboration lasted only about two years, but it yielded some definitive moments in the creation of the Doug mystique.

Emerson found his first success acting and directing on the New York stage. Under Griffith’s supervision he started filmmaking in 1914, with an adaptation of his own successful play, The Conspiracy. I haven’t seen this or most of his other early work, but his 1915 Ibsen adaptation Ghosts, codirected with George Nichols, betrays little of the dynamism that would run through his Fairbanks projects (although The Social Secretary of 1916, without Doug, is lively enough). Emerson continued to direct films and New York stage productions until his death in 1936, at the age of fifty-eight.

Loos was a tiny prodigy. She sold her first scripts at age nineteen, with the third, The New York Hat (1913), directed by Griffith, earning her twenty-five dollars. (Her punctilious account book is reprinted in her 1974 autobiography Kiss Hollywood Goodbye.) After writing scores of shorts, she moved into features in 1916, when, she claims, Emerson discovered her script for His Picture in the Papers. Clearing the project with Griffith and casting Doug Fairbanks, the team proceeded. This, Fairbanks’ third feature, proved a great success and solidified important aspects of his star persona.

Loos married Emerson, whom she recalled as having “perfected that charisma, which even a bad actor has, of being able to charm his off-stage public.” (4) He called her Bug, she called him Mr. E., and they became a Hollywood couple. They kept themselves before the public eye with interviews and books like How to Write Photo Plays (1920) and Breaking into the Movies (1921). These are full of information about the filmmaking practices of the day.

Loos married Emerson, whom she recalled as having “perfected that charisma, which even a bad actor has, of being able to charm his off-stage public.” (4) He called her Bug, she called him Mr. E., and they became a Hollywood couple. They kept themselves before the public eye with interviews and books like How to Write Photo Plays (1920) and Breaking into the Movies (1921). These are full of information about the filmmaking practices of the day.

Why did Emerson and Loos split from Fairbanks? Loos says that that Doug had become somewhat jealous of her notoriety. (5) Further, the couple yearned to return to New York. There Loos would hobnob with the Algonquin club crowd and write Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, a successful serial, book, play, and silent film. Eventually she would write plays and return to Hollywood as an MGM screenwriter.

Although they remained married and collaborated on plays and films, the pair eventually lived apart, the better to ease Emerson’s philandering. “Mr. E.’s devotion was largely affected by the amount of money I earned,” Loos recalled. (6) By her own testimony, she earned plenty. She writes in 1921:

The highest paid workers in the movies today are the continuity writers, who put the stories into scenario form and write the “titles” or written inserts. The income of some of these writers runs into hundreds of thousands of dollars a year . . . . Scenario writing does not require great genius. (7)

Loos is largely credited with bringing the witty intertitle into its own. Expository “inserts” were often neutral descriptions of the action or pseudo-literary ruminations. Loos created intertitles that were amusing in themselves. When Jeff, the hero of Wild and Woolly, comes to Bitter Creek he’s delighted to find a rugged life matching the one he mimicked in his East Coast mansion. So naturally Loos’ title reads, “All the discomforts of home.”

She wedged in puns, satiric jabs, and asides to the audience. The vegetarianism portrayed in His Picture in the Papers makes for anemic romance. Loos’ title prepares us:

The young suitor and Christine kiss by tapping each other’s cheek with their fingertips.

Later the intertitle stresses the more robust wooing program launched by Doug.

By the time Loos and Emerson left Fairbanks, the look and feel of their contributions had been mastered by others, notably director Allan Dwan, and smart-alec intertitles continued to grace Fairbanks’ modern comedies. Throughout the 1920s, most comedies would strive, not always successfully, for the cleverness Loos brought to the task. My own favorite in her vein comes in the Lloyd vehicle For Heaven’s Sake (1926). Harold is a millionaire courting a girl working in her father’s mission house in the slums, and one of the titles refers to “The man with a mansion and the miss with a mission.” Such niceties largely vanished when movies started to talk.

Cutting edge

We can learn a lot about the history of Hollywood from these films too. In the 1910s, narrative techniques were being put in place: the goal-oriented hero, the multiple lines of action, the need to prepare what will happen later, the use of motifs as running gags. At the start of The Matrimaniac, we see Doug sneaking into a garage and letting the air out of a car’s tires. Only later, after he has eloped with the daughter of the household, do we realize that this was a way to keep her father from pursuing them. In the course of the same film, the elopement is aided by passersby, and Doug keeps scribbling IOUs to pay them. At the end, the parson who has helped the couple the most is rewarded by the biggest payoff, with Doug shoveling bills at him.

The same years saw the consolidation of the “American style” of staging, shooting, and cutting scenes. (For more on this trend, see our earlier entries here and here.) Fairbanks’ films from 1916 to 1920 display a growing mastery of continuity techniques; the style coalesces under our eyes.

The system depended on breaking up master shots into many closer views. This practice was less common among European directors of the time, who might supply inserts of printed matter like letters but did not usually dissect the scene into shots of different scales. In His Picture in the Papers, for instance, we get a master shot (nearer than it would be in a European picture) of Melville paying court to Christine, followed immediately by closer views that show their expressions.

This is a minimal case. Not only are the shots all taken from the same side of the line of action (the famous 180-system) but they are taken from approximately the same angle. Filmmakers sometimes varied the angle more, usually to indicate a character’s point of view but sometimes to bring out different aspects of the action. (See here for examples from William S. Hart.)

Very quickly directors realized that you didn’t need a master shot if you planned your shots carefully. In Flirting with Fate, the artist Augy is chatting with Gladys, while her mother and her rich suitor watch from another part of the room. No long shot presents both pairs.

The mother summons Gladys, and when she and Augy rise, director Christy Cabanne cuts to another shot of them, moving into the frame.

This is a very rare option in most national cinemas of the period, which would simply frame the couple in a way that allowed them to rise into the top of the same shot. Now Gladys hurries out, crossing the frame line. This exit matches her entrance on frame left, meeting her mother.

Such a scene is obvious by today’s standards, but a revelation at the time—a way of lending even static dialogue scenes a throbbing rhythm that absorbed viewers. Around the world, notably in the Soviet Union, young directors saw this as the cutting-edge approach to visual storytelling. The new style was as probably as exciting to them as the powers of the Internet are in our time.

Because of analytical editing, the cutting pace of American films of the late 1910s is remarkable, and the Fairbanks films, with their strenuous tempo, are fair examples; the average shot length in these films ranges between 4 seconds and 6.6 seconds. With so many shots, production procedures emerged to keep track of them. To a certain extent shots were written into the scenarios Loos refers to, but directors also broke the action up spontaneously during filming. The cameraman, and later a “script girl,” would log the shots during shooting so that they could be assembled correctly in the editing phase.

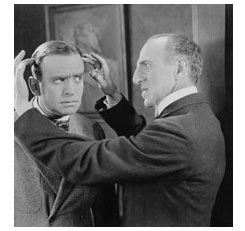

Directors were still refining the system, though, as we can see from an awkward passage of shot/ reverse shot in A Modern Musketeer.

The eyelines are a bit out of whack, but odder still are the identical backgrounds of the two shots. Evidently director Allan Dwan made these shots quickly and closer to the canyon rim, in the expectation that nobody would notice the disparity.

Point-of-view shots were easier to manage, and they could intensify the drama. Later in A Modern Musketeer, the rapacious Chin-de-dah tells the white tourists he’s getting married. To whom? asks Elsie. Instead of answering, “You,” he holds up his knife.

Sometimes you suspect that filmmakers were multiplying shots just for the fun of it. The early Fairbanks films are vigorous to the point of choppiness; action scenes spray out a hail of images, some offering merely glimpses of what’s happening. Wild and Woolly is especially frantic, with the final sequences of kidnapping, gunplay, and a ride to the rescue breathless in their pace. In the course of it, Emerson realizes that fast action needs some overlapping cuts to assure clarity. Doug bursts through a locked door in one shot, and from another angle, we see the door start to open again.

Only a few frames are repeated, but the movement gains a percussive force. Doubtless the Russians studied cuts like this; Eisenstein made the overlapping cut part of his signature style.

By contrast, The Mark of Zorro and its successors have calmer pacing. Doug’s acting got more restrained too, with his bounciness largely confined to the action scenes. Already in 1920, high-end pictures were finding a more academic look, a polished and measured style. Dialogue titles became more numerous, and big sets and other production values were highlighted.

I’ve been able to sample only a few points of interest in the early Fairbanks output. I haven’t talked about Fairbanks’ foray into Sennett-style farce, the cocaine-fueled Mystery of the Leaping Fish (1916), or the bold experimentation of the cinematography in the dream sequence of When the Clouds Roll By. My point is just to note that these films radiate exuberance—not only in their hero but in their very texture. Scene by scene, shot by shot, Doug’s energy is caught by an efficient, pulsating style that was an engaging variant of what would soon become the lingua franca of cinematic storytelling.

For other reading on Fairbanks, you can consult Alastair Cooke’s Douglas Fairbanks: The Making of a Screen Character (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1940), one of the earliest and still most thought-provoking studies; John C. Tibbetts and James M. Welsh’s His Majesty the American: The Films of Douglas Fairbanks, Sr. (South Brunswick, NJ: A. S. Barnes, 1977), which is wide-ranging and strong on the early films; Booton Herndon’s Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks (New York: Norton, 1977); and Douglas Fairbanks: In His Own Words (Lincoln, NE: iUniverse, 2006), a collection of interviews and essays signed (but probably mostly not written) by the star. I’ve also been enlightened by Lea Jacobs’ essay “The Talmadge Sisters,” forthcoming in Star Decades: The 1920s, ed. Patrice Petro (Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, forthcoming). Online, there is much information at the Douglas Fairbanks Museum site.

(1) Kristin Thompson, “Fairbanks without the Mustache: A Case for the Early Films,” in Sulla via di Hollywood, ed. Paolo Cherchi Usai and Lorenzo Codelli (Pordenone: Biblioteca dell’Immagine, 1988), 156-193; David Bordwell, Narration in the Fiction Film (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1985), 166-168, 201-204.

(2) This set is very well chosen, but there are enough other films surviving from this period to warrant another box. It could include The Lamb (1915), Double Trouble (1915), The Good Bad Man (1916), Manhattan Madness (1916), The Americano (1916), Down to Earth (1917), The Man from Painted Post (1917), His Majesty the American (1919), and The Half Breed (1916), in which Fairbanks plays a biracial hero. On the matter of race, the films in the collection aren’t free of condescension and stereotyping, but there are also moments of affection between Fairbanks and Native Americans. He had extraordinarily dark skin, a fact he apparently took in his stride.

(3) I believe that this print is from a different version than the one I’ve known before; a few shots seem to show slightly different angles. (Perhaps the earlier one was from a foreign negative?) An informative page of the Flicker Alley booklet signals the provenance of the prints. While I’m on the subject, I should mention that occasionally the framing seems a bit cropped, but that could be due to the source material.

(4) Loos, Kiss Hollywood Goodbye (New York: Ballantine, 1974), 2.

(5) Loos’ account of the break with Fairbanks can be found in her memoir, A Girl Like I (New York, 1966), 178. You have to admire a book that ends with the line, “Miss Loos, you sure are flypaper for pimps!”

(6) Loos, Kiss Hollywood Goodbye, 14.

(7) Emerson and Loos, Breaking into the Movies (Philadelphia: Jacobs, 1921), 43.

When the Clouds Roll By.

PS 30 Nov: Internets problems and a memory lapse kept me from mentioning two other important books on Anita Loos: Gary Carey’s lively biography Anita Loos (Knopf, 1988) and Anita Loos Rediscovered: Film Treatments and Fiction, ed. and annotated by Cari Beauchamp and Mary Anita Loos (University of California Press, 2003). Both Carey and Beauchamp echo Loos’ claims that the couple split from Fairbanks because he was somewhat envious of the attention they received, while Carey adds that Fairbanks wanted to break out of the “boobish” parts Loos wrote for him (p. 50).

PPS 8 Dec: Mea culpa again. I overlooked Richard Schickel’s book-length essay, His Picture in the Papers: A Speculation on Celebrity in America, Based on the Life of Douglas Fairbanks, Sr. (New York: Charterhouse, 1973). It’s a lively and thoughtful argument that Doug was one of the very first modern celebrities, and one who enjoyed his role as such.