Archive for the 'Silent film' Category

Gradation of emphasis, starring Glenn Ford

DB here:

Charles Barr’s 1963 essay “CinemaScope: Before and After” has become a classic of English-language film criticism. (1) It proffers a lot of intriguing ideas about widescreen film, but one idea that Barr floated has more general relevance. I’ve found it a useful critical tool, and maybe you will too.

Grading on a curve

Barr called the idea gradation of emphasis. Here’s what he says:

The advantage of Scope [the 2.35:1 ratio] over even the wide screen of Hatari! [shot in 1.85:1] is that it enables complex scenes to be covered even more naturally: detail can be integrated, and therefore perceived, in a still more realistic way. If I had to sum up its implications I would say that it gives a greater range for gradation of emphasis. . . The 1:1.33 screen is too much of an abstraction, compared with the way we normally see things, to admit easily the detail which can only be really effective if it is perceived qua casual detail.

The locus classicus exemplifying this idea comes in River of No Return (1954). When Kay is lifted off the raft, she loses her grip on her wickerwork bag and it’s carried off by the current. (See the frame surmounting this entry.) Kay and her boyfriend Harry are rescued by the farmer Matt. As all three talk in the foreground, the camera catches the bundle drifting off to the right.

Even when the men turn to walk to the cabin, Preminger gives us a chance to see the bundle still drifting downstream, centered in the frame.

The point of this shot, Barr and V. F. Perkins argued, is thematic. As Kay moves from the mining camp to the wilderness, she will lose more and more of her dance-hall trappings and be ready to accept a new life with Matt and Mark. The last shot of the film shows her final traces of her old life cast away.

Cutting in to Kay’s floating bag would have been heavy-handed; if you stress a secondary element too much, it becomes primary. Barr reminds us that any film shot can include the most important information, as well as information of lesser significance. A film can achieve subtle effects by incorporating details in ways that make them subordinate as details and yet noticeable to the viewer. Or at least the alert viewer.

In Poetics of Cinema, I wrote an essay on staging options in early CinemaScope, and Barr’s idea helped me illuminate some of the strategies I discuss. (For earlier comments on Barr on Scope and River of No Return, see my article elsewhere on this site.) Today I want to consider how the notion of gradation of emphasis has a more general usefulness.

Barr contrasts the open, fluid possibilities of CinemaScope with two other stylistic approaches, both found in the squarer 1.33 format. The first approach is the editing-driven one he finds in silent film. This tends to make each shot into a single “word,” and meaning arises only when shots are assembled. Barr associates this approach with Griffith and Eisenstein. The second approach, only alluded to, is that of depth staging and deep-focus shooting, typically associated with sound cinema of the late 1930s and into the 1950s.

Both of these approaches, montage and single-take depth, lack the subtle simplicity of Scope’s gradation of emphasis.

There are innumerable applications of this [technique] (the whole question of significant imagery is affected by it): one quite common one is the scene where two people talk, and a third watches, or just appears in the background unobtrusively—he might be a person who is relevant to the others in some way, or who is affected by what they say, and it is useful for us to be “reminded” of his presence. The simple cutaway shot coarsens the effect by being too obvious a directorial aside (Look who’s watching) and on the smaller [1.33] screen it’s difficult to play off foreground and background within the frame: the detail tends to look too obviously planted. The frame is so closed-in that any detail which is placed there must be deliberate—at some level we both feel this and know it intellectually.

To see Barr’s point, consider a shot like this one from Framed (1947).

The shot, rather typical of 1940s depth staging, displays an almost fussy precision about fitting foreground and background together. That bartender, for instance, stands squeezed into just the right spot. (2) Barr claims that we sense a certain contrivance when primary and secondary centers of interest are jammed into the 1.33 frame like this.

We don’t sense the same contrivance in the widescreen format, he suggests. Barr assumes, I think, that the sheer breadth of any Scope frame will include areas of little consequence, whereas that’s comparatively rare in a 1.33 composition. This is an intriguing hunch, but uninformative patches of the frame may not be intrinsic to the Scope technology. Perhaps the fairly neutral and inexpressive uses of Scope that dominate the early 1950s, the sense of empty and insignificant acreage stretching out on all sides, make us expect that little of importance will be found there. Accordingly, directors can create a sense of discovery when we spot a significant detail in this stretch of real estate.

Anyhow, Barr indicates that if static deep-space staging made the frame too constrained, 1930s and 1940s directors who combined depth with camera movement created more spacious and fluid framings. He suggests that Mizoguchi, Renoir, and others anticipated the possibilities of Scope.

Greater flexibility was achieved long before Scope by certain directors using depth of focus and the moving camera (one of whose main advantages, as Dai Vaughan pointed out in Definition 1, is that it allows points to be made literally “in passing”). Scope as always does not create a new method, it encourages, and refines, an old one (pp. 18-19).

Barr believes that Scope positively encouraged gradation of emphasis, and that widescreen directors of the 1950s and 1960s have made the most fruitful use of the strategy. But he allows directors of all periods utilized gradation of emphasis, even in the standard 1.33 format. This is, I believe, a powerful idea.

Before Scope: Making the grade

Barr’s discussion of silent cinema, relying on notions of editing associated with Griffith and Soviet directors like Eisenstein, is done with a broad brush, but it’s typical of the period in which he was writing. We didn’t know much about silent filmmaking until archivists started to exhume important work in the 1970s. It’s no exaggeration to say that we haven’t really begun to understand the first twenty-five years of cinema until fairly recently.

In a way, the staging-driven tradition of the 1910s, which I’ve often mentioned on this site (here and here and here), exemplifies some things that Barr would approve of. Directors of that period made extraordinary use of the frame and compositional patterning. They staged action laterally, in depth, or both. They let shots ripen slowly or burst with new information. This approach to using the full frame (with only occasionally cut-in elements) has come to be called the tableau style, emphasizing its similarity to composition of a painting—although we shouldn’t forget that these films are moving paintings, and the compositions are constantly changing. The result is that emphasis tends to be modulated and distributed among several points of interest.

Central to this strategy, I think, was camera distance. American directors tended to set the camera moderately close, cutting figures off at the knees or hips, and by taking up more frame space, the foreground actors tended to limit the area available for depth arrangement or for significant detail.

This shot from Thanhouser’s The Cry of the Children (1912) is a rough 1910s equivalent of the crammed shot from Framed above. (See also the tightly composed shots from DeMille’s Kindling (1915) here.)

The European directors, by contrast, tended to let the scene play out in more distant shots, creating spacious framings of a sort that would be reinstituted in early CinemaScope. Consider this shot from Holger-Madsen’s Towards the Light (Mod Lyset, 1919) and another from Island in the Sun (1957).

Both, it seems to me, have the type of open composition and the foreground/ background interplay that Barr praises in his article.

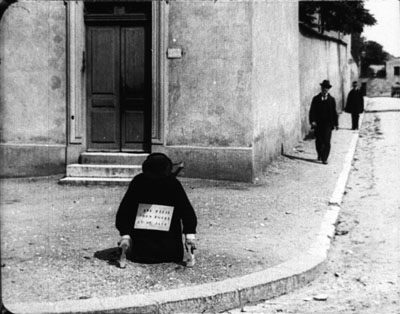

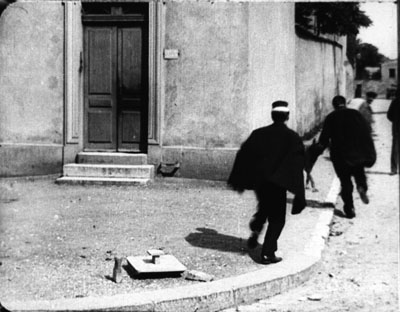

We can go back further. The Lumière brothers’ cameramen made fiction films as well as documentaries, and we occasionally find moments that suggest early efforts at gradation of emphasis. In Le Faux cul-de-jatte (1897), an apparent amputee is begging in the foreground while in the distance a man is walking down the street.

A cop crosses the street from off right and follows the pedestrian.

As the foreground fills up, the man we’ve seen in the distance gives the beggar some money.

As he goes out left, the cop is still approaching, and a vagrant dog appears.

The cop comes to the beggar, partially blocking the dog, who takes care of other business. (Not everything in this movie is staged.)

The cop checks the beggar’s papers and finds them to be suspect. The fake amputee jumps up and races off in the distance, with the cop pursuing.

As with many staged Lumière shorts, several figures converge in the foreground in order to create a culminating piece of action. Here the distant man and the cop, both secondary centers of interest, serve as a kind of timer, assuring us that something will happen when they meet at the beggar.

These are just some quick examples. We should continue to study the ways in which, with minimal use of editing, early filmmakers found ingenious ways to create gradation of emphasis. (2)

Some uses of grading

Barr, like most critics writing for the British journal Movie, was sensitive to the ways in which technique has implications for character psychology and broader thematic meanings. Kay’s bundle is one point along a series of changes in her character and her situation. But gradation of emphasis can serve more straightforward narrative purposes as well.

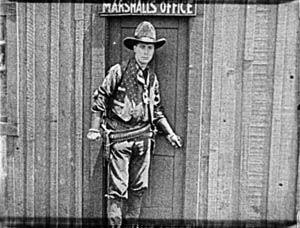

Consider our old friends, surprise and suspense. In the original 3:10 to Yuma (1957) Dan Evans is confronting the ruthless outlaw Ben Wade.

We get a string of reverse shots.

Then in one shot of Wade, without warning, a shadowy figure emerges out of focus in the left background.

Now we realize that Evans has been diverting Wade from the fact that the sheriff’s posse is surrounding him. Now we wait for Wade to discover it; how will he react?

While we’re on Glenn Ford, another nice example occurs in Framed. Mike Lambert has been romancing a woman named Paula, but we know that she and her lover Steve are plotting to fake Steve’s death and substitute Mike’s body.

She brings Mike to Steve’s elegant country house, having presented Steve as someone she knows only slightly. When Mike goes into the bathroom to wash up, we notice something important behind him.

With Mike at the sink, we have plenty of time to recognize Paula’s robe. Director Richard Wallace prolongs the suspense by giving us a new shot of Mike in the mirror, with the robe no longer visible.

But when Mike turns to leave, a pan following him brings him face to face with what we saw, accentuated by a track forward.

We get Mike’s reaction shot, followed by a cut to Steve and Paula downstairs, suspecting nothing. “So far, so good,” says Steve, looking upward at the bathroom.

The rest of the scene will play out with Mike aware that they’re deceiving him. As often happens with suspense, we know more than any one character: We know the couple’s scheme and Mike doesn’t, but they don’t (yet) know that Mike is now on his guard.

This isn’t as subtle a case as River of No Return, but I suspect that it’s more typical of the way Hollywood filmmakers use gradation of emphasis. Paula’s bathrobe is a good example of what I called in The Classical Hollywood Cinema the strategy of priming: planting a subsidiary element in the frame that will take on a major role, even if initially its presence isn’t registered strongly. My example in CHC was a coat rack in the Dean Martin/ Jerry Lewis comedy The Caddy (1953). In effect, the distant pedestrian in the Lumière film is an early example of priming.

Howard Hawks adopts the Lumière technique in order to sustain a flow of dialogue in Twentieth Century (1934). Here the foreground conversation is accompanied by a procession of people emerging in the distance and stepping up to take part.

The shot concludes, as does the shot of Faux cul-de-jattes, with a retreat from the camera.

The priming of secondary elements here, the summoning of the train attendant and the conductor, obeys Alexander Mackendrick’s dictum that the director ought to construct each shot so as to prepare for what will come next.

As Barr indicates, the idea of gradation shades insensibly off into general matters of cinematic expression. In The Devil Thumbs a Ride (1947), the bank robber has hitched a ride with an unassuming civilian, and they stop for gas. When the attendant shows a picture of his little girl, the robber gratuitously insults her. (“With those ears she’ll probably fly before she can walk.”)

Later, the station attendant hears a radio broadcast describing the fugitive. First he has his head cocked as he listens attentively, but then his gaze drifts to the picture of his little girl.

The attendant is the center of dramatic interest, but when he looks at the picture, so do we (primed by the view of it earlier). Instantly we understand that the attendant’s resolve to call the police springs partly from an urge to get even with the man who insulted his daughter. A minor instance, surely, but it illustrates Barr’s point that the notion of gradation of emphasis leads us to consider “the whole question of significant imagery.”

The more the merrier

Barr seems to favor a plain style; he prefers Preminger’s quiet framings to the rococo imagery of Aldrich’s Vera Cruz (1954). Presumably the famous shot above from Wyler’s Best Years of Our Lives (1946) would be too obviously composed for Barr’s taste.

But there is merit in considering how a secondary center of interest can vie for supremacy. André Bazin declared Wyler’s shot a bold stroke exactly because its self-conscious precision created a tension between what was primary and what was subordinate. (3) The action in the foreground is of dramatic interest because Homer has learned to play the piano, and this represents a phase of his coming to terms with his wartime disability. Yet the most consequential action is taking place in the distant phone booth, where Fred breaks up with Al’s daughter Peggy. The gradation of emphasis is inverted, and we wait in suspense to find out what happens. Bazin taught us to recognize that what appears to be primary may actually be creatively distracting us from the scene’s principal action. (4)

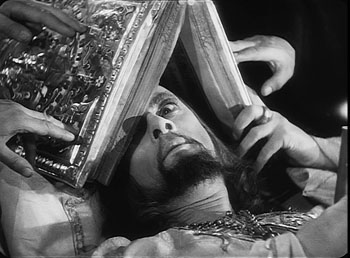

A director can also turn a primary center of interest into something secondary, but powerful. In one sequence of Eisenstein’s Ivan the Terrible I (1944), the apparently dying tsar is being prayed over by churchmen. Ever suspicious, he peers out from under the book, using only one eye.

As the scene develops, Prince Kurbsky meets Ivan’s wife and tries to seduce her. In the background an icon’s eye glares out, as if Ivan is watching them.

The single eye, which is a motif we find in other Eisenstein films, becomes a significant one throughout both parts of Ivan. More generally, this device manifests Eisenstein’s conception of polyphonic montage, which explored how the filmmaker can control all the various aspects of his images and make them weave throughout the film—promoting one at one moment, demoting it at another. (5)

Barr’s essay assumes that Eisenstein’s montage stripped each image down to a single meaning. In fact, though, Eisenstein wanted to multiply the sensuous and intellectual implications of each shot by weaving objects, gestures, body parts, musical motifs, and the like into an ongoing stylistic fabric. Each shot’s gradation of emphasis can suggest thematic parallels, deepen the drama, or heighten emotional expression, just as a complex score enhances an operatic scene.

Tati as well likes to create an interplay between primary and subsidiary centers of interest. Or rather, he sometimes abolishes our sense of what is primary and what isn’t. The crowded compositions of Play Time (1967) often bury their gags in a welter of inessential details. During the lengthy scene in the Royal Garden restaurant, a minor running gag involves the dyspeptic manager. He has just mixed some headache medicine with mineral water, but the action is easily lost within the tumultuous image. Even the soundtrack cues us only slightly, with a bit of fizz among the music and crowd noise.

As the manager lowers the glass, Hulot thinks it’s pink champagne being offered to him.

Rolling the stuff in his mouth, Hulot realizes his mistake as he earns a stare from the manager.

There is so much competing sound and activity in the shot that some viewers simply don’t notice this bit at all. In Play Time, gradation of emphasis is often flattened out, leaving us to rummage around the composition for the gag.

Some final notes

Barr was not particularly interested in the mechanics of how we come to notice something in the shot, be it primary or secondary in value. In On the History of Film Style, I suggested that many aspects of technique work to call attention to any element in the field. The filmmaker can put a something in motion, turn it to face us, light it more brightly, make it a vivid color, center it in the frame, have it advance to the foreground, have other characters look at it, and so on. These tactics can work together in a complex choreography. In Figures Traced in Light, I argued that they depend on the fact that we scan the frame actively; the techniques guide our visual exploration. (6)

You can see this guidance at work in most of the examples I’ve mentioned. In River of No Return, we are coaxed into noticing Kay’s bundle because we’re cued by movement (the bundle falls and drifts off), performance (she shouts, “My Things!” and stretches out her arm), music (we hear a chord as the bundle splashes), and framing (Preminger’s camera pans slightly as the trunk drifts away). The critic can refine our sense of the effects that a film arouses, but it’s one task of a poetics of cinema, as I conceive it, to examine the principles and processes that filmmakers activate in achieving those effects.

Finally, we might ask: To what extent do we find gradation of emphasis in current filmmaking? Today’s American cinema relies heavily on editing, using a style I’ve called intensified continuity. Each shot tends to mean just one thing, and once we get it we’re rushed on to the next. The unforced openness of the wide frame that Barr celebrated has been largely banned, in favor of tight singles—even in the 2.40 anamorphic format. It seems that most filmmakers are no longer concerned with gradation of emphasis within their shots.

To find this strategy surviving at its richest, I think we have to look overseas. If you want names: Angelopoulos, Tarr, Kore-eda, Jia, Hou. (7)

(1) It was published in Film Quarterly, vol. 16, no. 4 (Summer, 1963), 4-24. Unfortunately, it’s not available free online, nor is a complete version available in anthologies, so far as I know. If you have access to online journal databases, you can find it. Otherwise, off to the library w’ye!

(2) In the Poetics of Cinema piece (pp. 303-307), I argue that some early uses of Scope tried to approximate such tightly organized composition, despite technological barriers to focusing several planes of action.

(3) See André Bazin, “William Wyler, or the Jansenist of Directing,” in Bazin at Work: Major Essays and Reviews from the Forties and Fifties, ed. Bert Cardullo, trans. Cardullo and Alain Piette (New York: Routledge, 1997), 14-16.

(4) Actually the phone booth is primed for our notice by earlier shots in Butch’s tavern. See On the History of Film Style, 225-228.

(5) For more on Eisenstein’s idea of polyphonic montage, see my Cinema of Eisenstein (New York: Routledge, 2005) and Kristin’s Eisenstein’s Ivan the Terrible: A Neoformalist Analysis (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1981).

(6) For some empirical evidence of this guided scanning, see the work of Tim Smith at his website and in this entry on this site.

(7) I discuss some of these alternatives in On the History of Film Style and the last chapter of Figures Traced in Light.

Eternity and a Day.

PS 15 Nov. Two more items. First, if the ideas floated here intrigue you, you might want to take a look at an earlier entry on this site, called “Sleeves.”

Second, I had planned to include one more example, but forgot it. In Lumet’s Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead, Andy Hanson’s life is unraveling. We follow him back to his apartment, and as he enters on the extreme left, his wife Gina is visible sitting on the extreme right, her back to us.

Gina forms a secondary center of attention, but the key to the upcoming action is revealed in a third point of interest: the black suitcase pressed against the right frame edge. The shot tells us, more obliquely than one showing her leaving the bedroom with the case, that she is planning to leave him. Lumet’s image, reminiscent of the framing of the trunk in River of No Return, shows that gradation of emphasis isn’t completely dead in American cinema. The orange scrap of yarn, knotted to the handle for baggage identification, is a nice touch of realism as well as a welcome color accent that further draws the suitcase to our notice.

13 days without movies? Not desirable, but possible

DB yet again:

Our road trip started back on the twelfth of September. We drove to Iowa City and ate at our grad school hangout, Hamburg Inn no. 2. (We even remember Hamburg Inn no. 1, long since vanished.) We pressed on through Nebraska to Denver, for a meeting of the Amarna Research Foundation, which helps support the Egyptian expedition on which Kristin works. She gave a presentation about the unique composite statuary of the Amarna era containing a new hypothesis that Barry Kemp, head of the expedition, found promising. After enjoying the hospitality of ARF president Bill Petty and his wife Nancy, we visited the Rocky Mountain National Park.

After a long day’s drive west, we overnighted in Elko, Nevada, where we learned that Barack Obama was scheduled to give a stump speech the next morning. We hung around and joined an enthusiastic group from all over northern Nevada to hear what he had to say.

After shaking hands with Barack, we moved on, rolling through Utah and into Oregon and Crater Lake National Park. Then up the coast highway to Seattle, where our nephew Sanjeev works for Microsoft and lives with his wife Maggie. We did some nifty touristic things in Seattle, and then with Sanjeev and Maggie we pressed on to Vancouver for its annual film festival.

During our westward passage through Grand Island (neither grand nor apparently an island), Craig, Elko, Klamath Falls, Coos Bay, Tillamook, and Tumwater, we saw many intriguing things. There was, for instance, the perfect rainbow in the bleakly beautiful northwestern Nevada desert.

In a little Colorado town, we found the toilet seat with fishing lures embalmed within.

In Snoqualmie Falls, Washington, while we downed burgers and malts at the Candy Factory & Café, four red-hot mamas came in and spontaneously started singing 1940s swing, Andrews-sisters style.

Yet such roadside attractions can’t compensate for our trip’s biggest drawback. We didn’t see a single complete film, not even on the free HBO available in motels. We used our late evenings to wolf down Subway subs and scan the Internets for news of lipstick, pigs, and less important things like the free fall of the U. S. economy.

Still, even without watching movies we did run across many traces of cinema. So don’t worry: This isn’t a travel entry, but rather an offhand effort to note the ways film keeps crossing our path, sometimes in surprising ways.

Movies everywhere

For instance, Bill Petty, an ardent Egyptomane, has created a home theatre unlike any other. The Pharaohs surely look with envy on this screening room.

In this venue, Bill showed us his home-made mashup of the Lon Chaney Phantom of the Opera with the Andrew Lloyd Webber score. That was the closest we got to movie viewing on the trip.

Also in Denver, we ate breakfast with Diane Waldman, old friend and film prof at University of Denver, and her husband Neil. We of course wound up in a restaurant with movie posters.

Passing through Vernal, Colorado, we spotted the most austere multiplex we’d ever seen.

Then there was Donna Kupp’s Books in Reedsport, Oregon. Donna has an excellent collection of classic paperbacks and magazines.

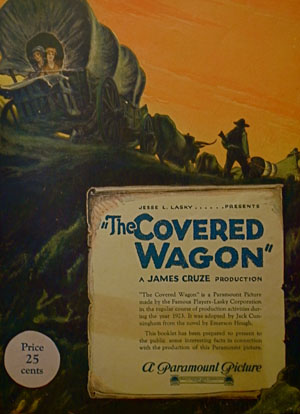

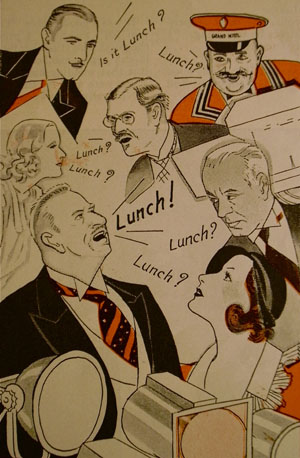

The high points of our purchases were an original souvenir program for The Covered Wagon and a pretty issue of Photoplay from 1932, which featured a gossipy story about the making of Grand Hotel.

The ladies’ big-band quartet wasn’t our reason for stopping in Snoqualmie, of course. You know why. The town was the shooting location of Twin Peaks. Hence this inevitable snapshot.

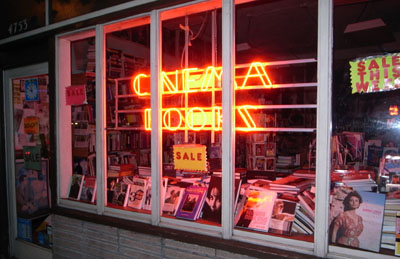

In Seattle, we discovered Stephanie Ogle’s outstanding Cinema Books on Roosevelt Way, N. E. This store is stuffed to the rafters with film items old and new–books, magazines, posters, and stills. Kristin even autographed some copies of her books.

We picked up several items there. Earlier that day, we visited Paul Allen’s lively Science-Fiction Museum. Sumptuous exhibits, but we weren’t allowed to photograph them. We did, however, get a chance to study a clone of the alien from The Day the Earth Stood Still.

As usual, a trip to an art museum provokes me to think of cinema. You don’t need much nudging to see this Rubens prototype for a Last Supper ceiling as a steep low-angle Welles or Hitchcock shot.

Less obviously, Abraham Janssens’ Origin of the Cornucopia (c. 1619) suggests a wide-angle lens at work. The three dryads stuffing the cornucopia are monumental, and monumentally skewed.

The stretched arm of the dryad on the left and the tipped knee of the one on the right seem to bulge right out of the picture plane. Check the hands, which thrust out of the picture and loom larger than the ladies’ heads. In particular, though you can’t see this in reproduction, the thumbnail of the figure on the right is a little blob of paint sitting on the painting’s surface, accentuating the sense that this hand is pointing right at us. Such images remind us that 2-D and 3-D are not so easy to keep distinct.

Our road trip confirms that movies are everywhere, waiting in the corners of our lives, ready to be activated with barely any prompting. Nonetheless, these are all merely teases, snacks making us eager for the banquet to come in Vancouver.

For Jim Emerson: Barbara Stanwyck, from Photoplay (Oct 1932).

Rio Jim, in discrete fragments

The first moving-pictures, as I remember them thirty years ago, presented more or less continuous scenes. They were played like ordinary plays, and so one could follow them lazily and at ease. But the modern movie is no such organic whole; it is simply a maddening chaos of discrete fragments. The average scene, if the two shows I attempted were typical, cannot run for more than six or seven seconds. Many are far shorter, and very few are appreciably longer. The result is confusion horribly confounded. How can one work up any rational interest in a fable that changes its locale and its characters ten times a minute?

H. L. Mencken, 1927

DB here:

Between about 1913 and 1920, the way movies looked changed, and we are still living with the results. What were the changes? What brought them about?

I’m just back from Brussels, after a two-week visit to the archive. During earlier trips, I’ve concentrated on examining films from the 1910s that exemplify the tableau tradition. That’s what we might call the stylistic approach that tells the story and achieves its other effects predominantly through staging—by arranging the actors within the frame, forming patterns that reflect what is important at a given moment.

The tableau tradition dominated European cinema of the early and mid-1910s, and it was also on display in the U. S. It is sometimes considered “theatrical” and “uncinematic,” but that’s a shortsighted view. The tableau tradition is one of the great artistic triumphs of film history. For backup on this, consult Ben Brewster and Lea Jacobs’ Theatre to Cinema and my On the History of Film Style and Figures Traced in Light. And you can go here and here on this site.

As the 1910s moved on, the staging-driven approach gave way to one dominated by editing. Roughly speaking, this strategy surfaced at two levels. Directors began to use crosscutting, aka parallel editing, more strenuously. By alternating shots, you could show events taking place at two or more locations. This technique was not used only for last-minute rescues; it was a way of keeping track of all the characters in nearly every sequence, whether they were going to converge or not.

Second, within a single strand of action, 1910s directors exploited analytical editing, breaking down a scene’s space into a host of details. Griffith often gets the credit for this tactic (and he happily claimed to have invented it), but it’s probably most fairly understood as a collective innovation.

Directors in the tableau tradition didn’t entirely avoid crosscutting or analytical editing, but there was a measurable shift of gravity in the second half of the 1910s. In the U.S., many filmmakers pushed editing techniques very hard. You can sense their exhilaration in discovering how editing lets them control pacing, make story points concisely, build suspense, and force the viewer to keep up.

During the 1910s, American movies became breathless. The hurtling pace of Speed Racer or The Dark Knight has its origins here; seen today, The Battle at Elderbush Gulch (1913) and Wild and Woolly (1917) still look mighty rapid-fire. And then as now some observers, like Mencken, complained that it was all too fast and furious.

Over the last thirty years, many scholars have studied this change, but for a glimpse of some supporting data, you can visit the remarkable website Cinemetrics. Yuri Tsivian, Barry Salt, and a corps of volunteer scholars have been measuring Average Shot Lengths in films from all eras. The data from the 1910s are pretty unequivocal. In the US around 1916-1918, movies became editing-dominated, shifting from an ASL of over 10 seconds, sometimes as much as 30 seconds, to 5-6 seconds or less. A 4-6 second average per shot persists in Hollywood through the 1920s, so Mencken’s guess about the “scenes” (as shots were then known) changing ten times a minute was more or less right.

Back in the 1980s, Salt and others, including Kristin and me, picked 1917 as a plausible point of reference for the consolidation of the continuity style. That was the point at which virtually every US film we watched contained at least one example of specific continuity techniques. (Most contained many more instances, of course.) We talk about that magical year in this entry, which you might want to read as an introduction to what follows today.

In just a few years, continuity editing became a coherent, supple means of expression, and it has defined Hollywood film style up to the present. What brought this about? Kristin and Janet Staiger offered an explanation in our 1985 book, The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960. They traced out several factors that encouraged and sustained this style. Especially important were the development of longer films, a conception of filmic quality, and the emergence of a specific division of labor.

Lately I’ve been revisiting these early years, chiefly to watch how directors pick up and refine the stylistic schemas that were coming into broader use. I want to know more about the little touches that directors had to control in creating this style. I’ve also been interested in to what extent these techniques were picked up by directors in Europe and Asia. The evidence is pretty clear that continuity cinema became a lingua franca of film style.

So if last year I pondered the minute compositional adjustments of Evgenii Bauer, this year it was all cutting. I focused on three filmmakers, but I’ll save discussion of two of them for a rainy day, or a book. In all, it was a thrill, as ever, to watch a stylistic system coalesce across a batch of films that are seldom mentioned in the history books.

The trail to continuity

The extraordinary films starring William S. Hart typify early American continuity techniques. After a distinguished career on the stage, Hart began as a film actor in 1914, when he was nearly fifty. He was intent on bringing realism to the newly burgeoning Western genre. His films were at first made under the auspices of Thomas Ince, a pioneer of rationalized production techniques, and with his Ince pictures Hart found worldwide success. He followed a rousing feature debut (On the Night Stage, 1915) with many shorter films. In 1917—mark the year—Hart broke with Ince and set up his own firm for The Narrow Trail. He continued to make films into the early 1920s, with Tumbleweeds (1925) marking his farewell to cinema.

Hart often directed his own pictures, though he also had the services of strong directors like Reginald Barker. The films have an assured brio, thanks to careful cutting and some felicitous touches.

They are fast-moving: In the five 1915 Hart films I watched, the ASL ranged from 8 to 11 seconds, but in 1916, the average jumped to 5-6 seconds per shot. The Narrow Trail seems to have an ASL of 3.7 seconds, but I can hardly believe it and I must verify it with another viewing. The 1918 and 1920 films I viewed average between 4.9 and 5.4 seconds per shot.

Just as important as the speed of cutting, naturally, is what Hart does with his cuts. In one scene from Between Men (1916), you can see the tableau aesthetic undermined by analytical editing. Gregg is a shifty stock trader, a species we still nurture. He’s trying to destroy Hampton’s fortune because he thinks that when the old man is destitute he’ll force his daughter to marry Gregg. Hampton has asked Bob White (Hart) to help get the goods on the suitor.

In one scene, the master shot approximates a tableau setup: Bob and Gregg stand in the middle ground, with a room visible behind them.

As the men swap increasingly tense challenges, Margaret Hampton enters the adjacent room and stands behind them as they talk. A director in the tableau tradition would have sustained the master shot and shown Margaret approaching in the background and drawing closer, reacting to what the men say. She could easily have been stationed hovering at the curtain on the right.

Instead, director C. Gardiner Sullivan has her arrive from another doorway in the adjacent room, one not visible in the master shot of the two men. He then cuts back and forth between the men and Margaret, and he positions her at the left curtain–so that the men block her from our view! The blockage motivates cutting to Margaret for her reactions to what Bob and Gregg say.

Only when she wants to challenge Bob’s suggestion that he might marry her does Margaret come into the same frame as the men, who part to make room for her.

It turns out that this sequence is but a rehearsal for a lengthier passage in which Hampton will come in from the adjacent room (via the door we do see in the background). As with Margaret’s entrance, his arrival will be blocked by Gregg’s body, and Sullivan will cut among the trio in the foreground and Hampton’s approach behind them. That passage, which could also have been handled in a single framing in the tableau style, consists of four distinct setups and eighteen shots!

So even depth-based scenes can be recast as rapid découpage. The passage is probably overcut, but you can sense the filmmakers’ exhilaration in their power to chop up the world into separate, slightly jolting bits, forcing the audience to keep abreast of each item of information.

Managing details

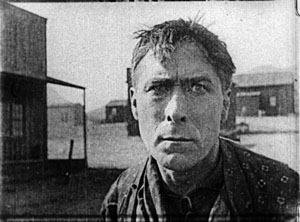

The variety of setups is worth noticing in another film, for here we can see the filmmakers taking pains to show each bit of action most clearly and emphatically. In The Return of Draw Egan (1916), when Egan sees the mayor’s daughter Myrtle he decides to stay on as marshal of Yellow Dog. The first shots show them looking at each other.

The next pair of shots shows the two looking at each other in close-up.

This gradual enlargement of the figures in a reverse-shot sequence would of course become a staple of analytical editing—perhaps it already was in 1916. Cut back to another framing of Egan, as the mayor signals Myrtle to join them. The slightly off-center composition reiterates her position off left.

Cut back to Myrtle, exiting her close-up. The next shot shows her joining the men, to be introduced to Egan.

But this is a different camera position than the one showing the men just previously. The daughter’s entrance has motivated a slightly changed composition. In the 1910s, cutting began to dictate staging, so that each composition had to fit smoothly into the flow of shots.

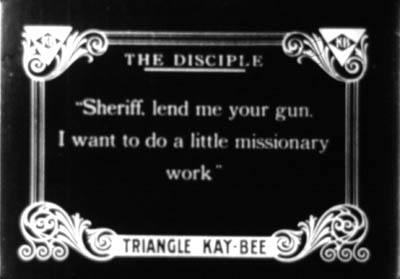

This sequence from Draw Egan doesn’t utilize axial cuts, those cuts that keep to the same angle and move straight in or out. Here the actors are angled to suggest that we are to some degree in between them. Indeed, sometimes the camera will put us directly between the characters. Here is a climactic confrontation from The Disciple (1915). A doctor has cuckolded Hart, but Hart brings him to save his daughter. As the doctor enters, the wife’s shameful look is met by Doc’s anxious expression, with a furious Hart pressing a pistol to his back.

This freedom of camera placement extends to point-of-view cutting. Again, this is an old technique, but like other old techniques, it was revived and refined as part of the synthesis that became the continuity style. So Keno Bates, Liar (1915; a splendid title) can make use of a cameo picture that captivates Bates after a shootout with the man who robbed him.

Later, the dance-hall girl catches sight of her rival when Bates muses on the cameo.

The pov framings don’t change much, but the angle chosen easily approximates both Bates’ view and her view over his shoulder. Moreover, the shot of Bates’ hands isn’t the sort of vacuous insert we often see at the period, with a letter or an object isolated against a blank ground. Here, the backgrounds change, so that the first shot is situated naturally in the wild, while the second is consistent with the barroom locale.

Putting the pieces together

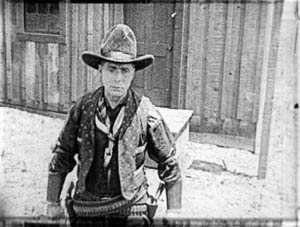

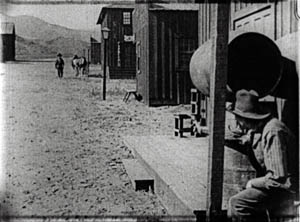

From very early in the history of Westerns, the main street shootout seems to have been a solid convention. Already in The Return of Draw Egan, it’s treated with a vitality and ingenuity that suggests creative reworking of a staple. The climactic shootout also shows just how flexible the new technique could be.

Egan has told his enemy, Arizona Joe, that he’ll meet him when the setting sun’s rays hit the saloon window. So the film crosscuts Egan in his marshal’s office with a nervous Joe, seen in close-up, eyeing the window.

When Joe gets up the nerve to leave, he hides behind a barrel and waits to ambush Egan. When Egan leaves his office, a reverse tracking shot follows him striding toward us.

Then we get an orienting long shot with Joe in the foreground and Egan approaching.

Edging sideways, Egan spots a reflection of Joe’s head in a window. These shots surmount today’s blog entry. You can see Egan’s reflection in the upper left pane.

Now aware of Joe’s tactic, Egan steps diagonally forward, coming ominously right up to the camera.

He fires and dispatches Joe. The townsfolk, who have been huddled in a house watching, declare they want Egan to stay on as marshal, despite his outlaw past. Myrtle chimes in, and we get a happy ending. Chaotic fragments? Mencken couldn’t have been more wrong. Or maybe he was just being grumpy.

The trail to Hollywood

There’s plenty more in these films—beautiful, sometimes minuscule matches on action; subtle timing of frame entrances and exits; and even proto-over-the-shoulder reverse shots. And we don’t have to claim that Hart’s films are the only innovative ones. They take their place within a broader, collective achievement that we still haven’t fully grasped.

Editing permitted everyone to act at small scale; the bargirl who sees Bates’ cameo need only lower one fist, tighten the other, and narrow her eyes to express her jealousy. The new style nurtured laconic stars like Hart. His films are full of pathetic situations that demand he display stoicism but also sensitivity. The long shots could emphasize his gestures and stances, while close-ups could display his worn, haunted face and pale eyes. He acts with those eyes, glancing aside to recall a traumatic event or looking downward as he hesitates to break bad news. Often the plot demands that he conceal his feelings or hide the truth behind an event, and the changing shots could penetrate the surface drama and highlight his slightest reactions. Hart could underplay his role because the editing shows us everything he might have said.

Known in France as Rio Jim, Hart was very influential on the Europeans. His pictures, along with De Mille’s The Cheat (1915) and the films of Chaplin and Fairbanks and many others, offered tutorials in the new style. Arguably, the cumulative force of these mainstream releases was greater than the influence of Griffith’s more prestigious output of the moment. There was only one Intolerance (1916), the film by which Griffith was most widely known abroad, but week by week the Westerns and comedies and dramas pouring out of Hollywood flaunted a new, almost frighteningly energetic approach to cinema.

Timing favored the Americans. The style emerged at around the start of World War I, when hostilities gave U. S. films a chance to displace the big French and Danish companies in many markets. Kristin explains how this happened in Exporting Entertainment, and she talks about the exceptional case of Germany in Herr Lubitsch Goes to Hollywood.

Some European directors picked up the new style immediately, others took a bit longer, and a few, like Feuillade, never fully adjusted to it. The principles of the older tableau style never utterly died out, as I try to show in Figures Traced in Light. But the future belonged to the editing-based aesthetic. Canonized, tweaked, updated, dismantled, undermined—however filmmakers reacted to classical continuity, it became the basis of international cinematic storytelling.

My epigraph comes from H. L. Mencken, “Appendix from Moronia: Note on Technic,” from Prejudices: Sixth Series (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1927), rep. in Phillip Lopate, ed., American Movie Critics: An Anthology From the Silents Until Now, expanded edition (New York: The Library of America, 2006), 35-36.

Silent film speeds can vary, so shot counts can yield different averages. I saw some of the Harts I mention in projection at last year’s Il Cinema Ritrovato, and they were projected at 18 or 19 frames per second, a common speed for the period. My ASLs are based on the running time. For the titles I saw in Brussels on a flatbed viewer, my basis was the length in meters. From that I’ve calculated running times and averages, assuming 18 frames per second. Projectionists of the time had freedom to screen at different speeds, so it’s possible that late 1910s Hart films were sometimes shown at 20 frames per second, which of course would make their cutting pace even faster.

For more on Hart’s career, see Diane Kaiser Koszarski, The Complete Films of William S. Hart: A Pictorial Record (New York: Dover, 1980). Koszarski devotes space to each film, with credits, excerpts from contemporary reviews, and excellent production stills. She also provides a sensitive critical overview. In William S. Hart: Projecting the American West (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2003) Ronald L. Davis has given us a brief, engrossing biography based on interviews and extensive archival research. Hart’s memoir, My Life East and West (1929, reprint 1994) is of course indispensable.

B is for Bologna

A big crowd assembles for one of the nightly screenings on the Piazza Maggiore.

Not laziness or old age (we hope) but sheer busyness has reduced our Bologna blogging to a single entry this year. Last year we managed three entries, but this time there was just so much to see, from nine AM to midnight, that we couldn’t drag ourselves away to the laptop. That it was blazing hot and surprisingly humid may have given us less biobloggability as well. Still, DB has many pictures, so maybe a followup blog with unusual images of critics and historians disporting in the sun….

Some backstory: Hosted by the Cineteca of Bologna, Il Cinema Ritrovato is an annual festival of rediscovered and restored films. Every July hundreds of movies are screened in several venues. For our 2007 report, with more background and some orienting pictures, go here and then here and here. Watch a lyrical trailer for the event here.

As before, both KT and DB contribute to this year’s entry. But first, the breaking story.

Freder and Maria, together again for the first time

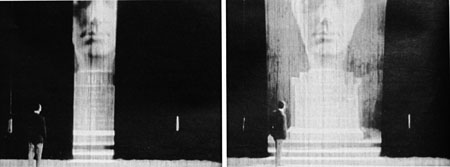

While we were there, the news of a long version of Metropolis broke. The estimable David Hudson offers a quick guide and an abundance of links at GreenCine. A rumor went around Bologna that fragments of the new Buenos Aires print would be screened, but instead there was a twenty-minute briefing anchored by Martin Koerber of the Deutsche Kinemathek. Along with him, Anke Wilkening (Friedrich-Wilhelm-Murnau Stiftung), Anna Bohn (Universitat der Kunste, Berlin), and Luciano Berriatua (Filmoteca Espanola) provided some key points of information.

*Provenance: The “director’s cut” was released in Argentina during the 1920s, with Spanish intertitles and inserts made at Ufa. A collector acquired a print. (Once more we have a collector to thank for saving film history.) When the Argentine film archive (Museo del Cine Pablo C. Ducros Hicken) received the copy in the 1960s, a 16mm dupe negative was made, and the nitrate original was discarded, a common practice at the time.

*Condition of the copy: The print is very worn, as the frame reproduced by Die Zeit indicates. Can the torrent of lines and scratches be eliminated? The rescue isn’t likely to be perfect; the damage is perhaps “beyond the reach of our algorithms,” as Martin puts it. To my eye, judging from the Die Zeit frames, many images are lacking in texture and contrast as well.

*Condition of the copy: The print is very worn, as the frame reproduced by Die Zeit indicates. Can the torrent of lines and scratches be eliminated? The rescue isn’t likely to be perfect; the damage is perhaps “beyond the reach of our algorithms,” as Martin puts it. To my eye, judging from the Die Zeit frames, many images are lacking in texture and contrast as well.

*Completeness: Contrary to some reports, virtually all the missing scenes are present on the Argentine print, the single exception being a small portion at a reel end. Among the new sequences are scenes filling in the roles of three characters (Georgy, Slim, and Josaphat), a car journey through the city, and moments of Freder’s delirium.

How can the researchers be confident that the print is so complete? It’s a fascinating story.

Metropolis has been reconstructed many times since the 1960s. In 2001, the Murnau foundation presented a digital restoration of the film supervised by Martin Koerber in collaboration with Enno Patalas. In this version, which is available on DVD (Transit Film, Kino International) about 30 minutes of the original material are missing. In 2003-2005 Enno Patalas and Anna Bohn together with a team at the University of the Arts in Berlin created a “Study Edition” version in which the missing footage was represented by bits of gray leader. For the first time the full length of the film was reconstructed with help from the the original music score.

In 2006 a “DVD study edition” was released by the Film Institute of the Berlin University of the Arts (Universität der Künste Berlin; DVD-Studienfassung Metropolis). This scrupulous version includes the original score, a lot of production material, and the complete script by Thea von Harbou. It’s a model of how digital formats can assist documentation of film history. The DVD incorporates production stills and intertitles from the missing scenes, and presents each scene in its original duration (sometimes with only gray leader onscreen). The editors determined the duration of each scene by a critical comparison of the remaining film materials with the music score and other source materials. This DVD edition was released in a limited edition available to educational and research facilities. For information see here or here.

In 2006 a “DVD study edition” was released by the Film Institute of the Berlin University of the Arts (Universität der Künste Berlin; DVD-Studienfassung Metropolis). This scrupulous version includes the original score, a lot of production material, and the complete script by Thea von Harbou. It’s a model of how digital formats can assist documentation of film history. The DVD incorporates production stills and intertitles from the missing scenes, and presents each scene in its original duration (sometimes with only gray leader onscreen). The editors determined the duration of each scene by a critical comparison of the remaining film materials with the music score and other source materials. This DVD edition was released in a limited edition available to educational and research facilities. For information see here or here.

Bohm and Patalas’s comparative method proved itself valid: The Buenos Aires footage fitted the gaps in their study edition perfectly!

A viewing copy will not be forthcoming immediately, given the restoration task, but sooner or later we will have a good approximation of the fullest version of one of the half-dozen most famous silent movies. Getting news like this while among archive professionals is one of the unique pleasures of Cinema Ritrovato. (Special thanks to Dr. Bohn for clarification on several points and to enterprising film historian Casper Tybjerg, who helped me get a copy of the Die Zeit issue.)

Two Davids and a Kevin: Robinson, Brownlow, and Shepard at a critics’ lunch.

Powell meets Bluebeard and Bartók

KT: One of the high points of the week for me was Michael Powell’s 1964 film of Béla Bartók’s short opera Bluebeard’s Castle. It was made for German television and shown in Bologna as Herzog Blaubarts Burg. Unfortunately it was programmed opposite the screening of fragments from Kuleshov’s Gay Canary, but Powell’s post-Peeping Tom films are so difficult to see that I made the difficult choice and gave up hope of seeing the entire Kuleshov retrospective.

Despite being relatively recent in comparison with most of the films shown during the week, Herzog Blaubarts Burg is one of the most obscure. I felt it was an extremely rare privilege to see it, one which I will probably never have again, at least in so splendid a print.

The film belongs to the late period of Powell’s career, after the controversial Peeping Tom had made it impossible for him to work within the mainstream film industry. It was produced by Norman Foster—though not the Norman Foster who directed Journey into Fear and several of the Charlie Chan and Mr. Moto films. This Norman Foster was an opera singer whose stage career was cut short by a dispute with Herbert von Karajan. His widow, Sybille Nabel-Foster, explained this and described how Foster produced and starred in two television adaptations, Herzog Blaubarts Burg and Die lustigen Weiber von Windsor (1966). Foster had originally approached Ingmar Bergman to direct the former, but when that proved impossible, Powell stepped in—and probably a good thing, too. It was definitely his kind of project.

The two performers are perfect for their roles. Foster plays Bluebeard brilliantly, having both a powerful bass voice and the necessary combination of handsomeness and a sense of threat. His co-star, the excellent soprano Ana Raquel Satre, recalls the pale beauties of some of Powell’s earlier films (Kathleen Byron as the increasingly mad Sister Ruth in Black Narcissus, Pamela Brown in I Know Where I’m Going!, and particularly Ludmilla Tcherina in The Tales of Hoffman), but she also bears a resemblance—perhaps deliberately enhanced through costuming and make-up—to Barbara Steele and other horror-film heroines of the 1960s.

The film was shot cheaply in a Salzburg studio, using garish, modernist settings against black backgrounds. These create a labyrinthine, floating space that avoids seeming stage-bound. (Hein Heckroth, the production designer, had previously worked on several Powell films, including The Red Shoes and The Tales of Hoffman.) I was reminded of Hans-Jürgen Syberberg’s Parsifal (1982), which looks somewhat less original in the light of Powell’s film.

As Nabel-Foster explained, after its initial screening on German television, Herzog Blaubarts Burg has been shown seldom because of rights complications with the Bartók estate. Non-commercial screenings have occurred on public television in the U.S. and Australia, but basically the film is off-limits until the copyright expires in 2015, seventy years after the composer’s death. Nabel-Foster has been providently preparing for a DVD release, gathering the original materials.

The print shown was a privately held Technicolor original from the era, in nearly mint condition. (The British Film Institute has a print as well.) The sparse subtitles written by Powell himself were added for this screening.

I’m not convinced that the film is quite the masterpiece that some claim, but it is a major item in Powell’s oeuvre nonetheless, and I felt privileged to have seen it in ideal conditions.

[July 12: Kent Jones, a great admirer of Powell and Bluebeard’s Castle, tells me that he programmed it at the Walter Reade in New York for a centenary retrospective of the director’s work in 2005. Foster’s widow introduced that screening as well.]

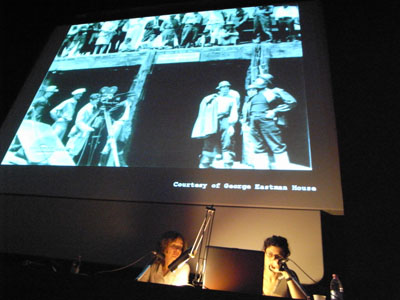

Janet Bergstrom and Cecilia Cenciarelli summarize their research on von Sternberg’s lost film The Sea Gull.

1908 and all that

KT: There were several programs of silent shorts, which I could only sample, as they tended to play opposite the Kuleshov films. As usual, the Bologna program included selections of short films from 100 years ago, so we were treated to numerous films from 1908. I was particularly pleased to see The Dog Outwits the Kidnappers, directed by Lewin Fitzhamon, who had made Rescued by Rover two years earlier. That film had been so fabulously successful that it had actually been shot three times as the negatives wore out from the striking of huge numbers of release prints.

The Dog Outwits the Kidnappers at first appears to be a sort of sequel (as it is described in the program), since it stars the same dog (Blair) who had played Rover, and again there is a kidnapped baby. It’s not really a sequel, though, since Cecil Hepworth, who had played the father in the earlier film, here appears as the kidnapper, and the dog is not named Rover. The new film is more fantastical than the original, since the dog races after the car in which the child is abducted and rather than fetching its master, effects the rescue itself by driving the car back home when the villain leaves his victim unattended!

Other 1908 films I particularly enjoyed: In Pathé’s Le crocodile cambrioleur, a thief hides inside a huge fake crocodile and crawls away, creating fear wherever he goes. The Acrobatic Fly by British director Percy Smith, provides a very close-up view of an apparently real fly juggling various small objects. (How was it done? It’s a mystery to me.)

Another retrospective series was “Irresistible forces: Comic Actresses and Suffragettes (1910-1915).” The suffragette films were rather depressing, despite the fact that many were meant at the time to be comic and amusing. Mostly the joke was how masculine these determined women were, a self-verifying proposition when the filmmakers often chose to have the suffragettes played by men. My favorite program was one involving early French female comics. I’ve long been fond of Gaumont’s Rosalie series since seeing a few at an early-cinema conference in Perpignon, France back in 1984. Rosalie, a chubby, cheerful little dynamo played by Sarah Duhamel, was highly entertaining in three films in the “France—Rosalie, Cunégonde et les autres…” program.

As Mariann Lewinsky, who devises these annual series, pointed out, Duhamel is the only early female French comic whose name we know. Léotine, represented here in Rosalie and Léotine vont au théâtre, is played by an anonymous actress. I had not encountered Cunégonde, also anonymous, before, but she proved to be quite amusing as well. I particularly liked Cunégonde femme du monde, where she plays a maid who dresses up as a society lady when her employers go off on a trip; the carefully constructed story and twist ending are impressive for such an apparently minor one-reeler.

It was a treat to see a succession of gorgeous prints of von Sternberg’s films. I particularly enjoyed seeing Thunderbolt (1929) again after many years. Back in 1983 I taught a survey film history course in which I used the director’s first talkie as my example of the transition to sound. Not a good example, I must admit, since Thunderbolt is completely atypical, with its highly imaginative use of offscreen sound. The second half, set primarily in a prison block, involves shouts from unseen cells and a small band that breaks into songs, often completely out of tone with the action, at unexpected moments. Eisenstein and the other Soviet directors would have thoroughly approved of its sound counterpoint. I have to admit that I prefer von Sternberg’s George Bancroft films (Underworld, Docks of New York, and Thunderbolt) to the Dietrich ones. Not only are the plots simpler and more elegant, but they contain a genuine element of emotion that is not, as in the Dietrich series, frequently undercut by irony.

I didn’t make it to many of the CinemaScope films playing on the very big screen in the Cinema Arlecchino theater, but I did enjoy two westerns. Anthony Mann’s Man of the West (1958) and John Sturges’ Bad Day at Black Rock (1954) both looked terrific and were highly popular with everyone we talked to. The latter was particularly a revelation, since in contrast to the Mann, it hasn’t had much of a reputation among cinephiles.

A Rodchenko angle for Yuri Tsivian.

Teacher and experimenter

DB: As Kristin mentioned, we missed a lot of the “Hundred Years Ago” series—a pity, since 1908 is a miraculous year—in order to keep up with one of our favorite directors, Lev Kuleshov.

In the 1960s and 1970s, it was common to say that Eisenstein and Vertov were the most experimental Soviet directors, while the others were more conventional. Then we realized that in films like Arsenal (1928), Dovzhenko had his own wild ways. Then we discovered the Feks team, Kozintsev and Trauberg, and the bold montage of The New Babylon (1929). A closer look at Pudovkin, particularly his early sound films like A Simple Case (1932) and Deserter (1933), revealed that he too was no timid soul when it came to daring cutting and image/ sound juxtapositions. But surely their mentor Kuleshov, admirer of Hollywood continuity and proponent of the simplest sorts of constructive editing, played things safe?

Wrong again. Just as we must reevaluate the other master Soviet directors (even in their purportedly safe Stalinist projects), so too does Kuleshov deserve a fresh look. He got this thanks to Yuri Tsivian, who with the help of Ekatarina Hohlova (right; granddaughter of Kuleshov and his main actress Aleksandra Hohlova) and Nikolai Izvolov, mounted a superb retrospective. It ranged from Kuleshov’s first solo effort, Engineer Prite’s Project (1918) to his final film, the short feature Young Partisans (1942-3, never released).

Wrong again. Just as we must reevaluate the other master Soviet directors (even in their purportedly safe Stalinist projects), so too does Kuleshov deserve a fresh look. He got this thanks to Yuri Tsivian, who with the help of Ekatarina Hohlova (right; granddaughter of Kuleshov and his main actress Aleksandra Hohlova) and Nikolai Izvolov, mounted a superb retrospective. It ranged from Kuleshov’s first solo effort, Engineer Prite’s Project (1918) to his final film, the short feature Young Partisans (1942-3, never released).

My admiration for Kuleshov, confessed in an earlier blog entry, already led me to spot some weirdnesses in Mr. K’s official classics. The Extraordinary Adventures of Mr. West in the Land of the Bolsheviks (1924) boasts some very un-formulaic cutting in certain passages (including an upside-down shot when cowboy Jeddy ropes the sleigh driver), and By the Law (1926) makes chilling use of discontinuities when the scarecrow Hohlova holds the Irishman at gunpoint. But thanks to the retrospective we can confidently say that Kuleshov was no less venturesome, at least in certain projects, than his pupils.

Soviet specialists already suspected that The Great Consoler (1933) was K’s sound masterpiece, and another viewing confirmed it. It incorporates three registers. William S. Porter, in prison but serving in the pharmacy, witnesses brutality and oppression and is driven to drink. Under the name O. Henry he writes cheerfully sentimental tales as much to console himself as to charm readers. His stories are in turn consumed by shopgirls like Dulcie, a romantic who may not realize how unhappy she is. Kuleshov adds a level of sheer fantasy, represented by a pastiche silent film dramatizing O. Henry’s “A Retrieved Reformation,” in which a safecracker trying to go straight reveals his identity by saving a girl trapped in a bank vault. The embedded story features characters from the other two levels, convict Jimmy Valentine and Dulcie’s lover, a vaguely sadistic businessman in a ten-gallon hat.

The Great Consoler reminds us of the popularity of O. Henry in the Soviet Union, both among readers and the Russian Formalist literary theorists, who were fascinated by his flagrant, playful artifice. (Boris Eikhenbaum’s essay on the writer is one of the most brilliant pieces of literary analysis I know.) Even though Kuleshov must denounce Porter for reconciling the masses to their misery under capitalism, the zest of the embedded film and the unique architecture of the overall project pay tribute to another entertainer who did not forgo experimentation. And Kuleshov’s image of a writer in prison probably had Aesopian significance for artists in the era of Socialist Realism.

K’s other major sound experiment, less widely seen, is Gorizont (1932). The title is at once a man’s name and the Russian word for “horizon”—a metaphor literalized in the final shot of a train leaving a tunnel. As Yuri pointed out, it is one of the few Soviet films centered on a Jew, and so the formulaic growth-to-consciousness plotline takes on a new resonance in the light of Slavic anti-semitism. Lev Gorizont is an amiable, somewhat thick young man who dreams of emigrating to the US to make his fortune. But in New York he finds only poverty and disillusionment, eventually returning home to help make a better society. Famous for its use of sound, Gorizont contains a passage of imaginative “counterpoint.” Both Lev and his friend Smith have been jilted by the social-climber Rosie. As they talk, we hear warm piano music, but not until the end of the scene does Smith speculate that probably Rosie is somewhere listening to Chopin. The music has retrospectively functioned somewhat like crosscutting, suggesting that Rosie now lives among the wealthy.

Kuleshov, like Eisenstein, gained his fame for his ideas on editing and sound montage, but both men were deeply interested in performance. Kuleshov’s idea that the film actor should become an angular mannequin carries on the impulse of Meyerhold’s biomechanics, and he anticipated CGI software in suggesting that human action could be plotted on a three-dimensional grid. Still, Kuleshov usually gives his figures a fluid dynamism that doesn’t seem mechanical. The three narrative registers of The Great Consoler are delineated largely through acting: naturalistic and slowly paced in the prison scenes, rigid and posed in the shopgirl romance, and broad and eccentric in the embedded silent movie.

Kuleshov’s performance theories popped out of other films in the series. What survives of The Gay Canary (1929) centers on a cabaret actress courted by lustful reactionaries during the civil war, and her scenes of fury, as she flings around flowers, vases, and pieces of furniture, come off as acrobatic rather than realistic. Naturally, the circus milieu of 2 Buldy 2 (1929) encourages stunts. A father and son, both clowns, are to perform together for the first time, but the civil war separates them, and the elder Buldy, tempted for a moment to acquiesce to the White forces, casts his lot with the revolution. At the climax Buldy Jr. escapes the Whites thanks to flashy trampoline and trapeze acrobatics; the gaping enemy soldiers forget to shoot. Even Kuleshov’s more naturalistic films show flashes of kinetic, stylized acting. A partisan listens to a boy while draping himself over a door. A Bolshevik official answers the phone by reaching across his chest, twisting his body so the unused arm can hike itself up, right-angled, to the chair.

The interaction of the body with props occurs with a special flair in Young Partisans. A Bolshevik partisan tells some children how a boy saved his life in a German-occupied town (This flashback was directed by Igor Savchenko and functions as a short film on its own.) Having learned their lesson, the kids gather in their schoolroom and under the teacher’s eye draw a map of the partisans’ camp. But when Nazi soldiers burst in, the teacher flips the blackboard over; now all we see is algebra.

A scene of Hitchcockian suspense ensues: Will the Germans turn over the blackboard and discover the map? The tension is enlivened by a grotesque moment, when one alcoholic soldier finds a jar holding a pickled frog and decides to drink the formaldehyde. “Draw a map—show me where the partisans are!” the officer demands. He flips the blackboard, and in a split-second we see a boy crouching behind it; the blackboard swings into place toward us, the map now erased. The boy ducks into his seat, brushing off chalk dust.

There were plenty of other revelations. We got the reconstructed Prite (was it the first really modern Soviet film?), a bit of an original Kuleshov experiment in constructive editing, and a tantalizing fragment from The Female Journalist (1927), with a surprisingly pensive Hohlova as a modern-day reporter. Sasha (1930), directed by Hohlova herself, was a sympathetic portrait of a pregnant woman. An educational film called Forty Hearts (1930) explained the need to electrify the Soviet countryside and was brightened by faux-naïve animation. Timur and His Crew (1942), with some of the charm of a Nancy Drew movie, showed Young Pioneers helping on the home front; it unexpectedly centered on a girl’s devotion to her military father.

There were plenty of other revelations. We got the reconstructed Prite (was it the first really modern Soviet film?), a bit of an original Kuleshov experiment in constructive editing, and a tantalizing fragment from The Female Journalist (1927), with a surprisingly pensive Hohlova as a modern-day reporter. Sasha (1930), directed by Hohlova herself, was a sympathetic portrait of a pregnant woman. An educational film called Forty Hearts (1930) explained the need to electrify the Soviet countryside and was brightened by faux-naïve animation. Timur and His Crew (1942), with some of the charm of a Nancy Drew movie, showed Young Pioneers helping on the home front; it unexpectedly centered on a girl’s devotion to her military father.

One of the biggest surprises was news of Dokhunda (1936), an ethnographically based fiction set in Tazhikistan. Although the film is lost, Nikolai has reconstructed its plan, revealing that Kuleshov adopted a strange preproduction method. He prepared “living storyboards,” photos of the cast enacting the scenes. He then drew and scratched on them, creating busy, nervous backgrounds or changing the figures’ features and hair styles—Kuleshov as pre-Warhol scribbler, or a graffiti artist tagging his own images.

Nikolai has also finished a DVD edition of Prite that exemplifies what he calls hyperkino, a way of annotating and comparing a film’s images, texts, and supplementary materials for instant access. Another project involves the Yevgenii Bauer classic, The King of Paris (1917), which Kuleshov completed. We haven’t had the intertitles for this, however, but now Nikolai has discovered them, and they will go on the DVD version that is being completed. For more information on these projects and Dokhunda, go to hyperkino.net.

So Kuleshov stands revealed as more supple and ambitious than most of us once thought. Once more Bologna plays to its strengths—filling in gaps but also forcing us to rethink what we thought we knew.

The key issue: What the hell am I going to be seeing now? From left, Olaf Muller, Jonathan Rosenbaum, Don Crafton, Haden Guest, and KT.

So much else to report, so little time. Besides The King of Paris, there was a string of fine 1910s films. Raoul Walsh’s Pillars of Society (1916), while not a patch on his Regeneration of the previous year, offered a solid adaptation of Ibsen. The Dawn of a Tomorrow (1915), James Kirkwood’s Mary Pickford vehicle, seemed to me flat and talky, but others liked it. For me the outstanding item was Paul Garbagni’s In the Spring of Life (1912). Beautifully directed in the tableau style, with precise depth choreography and a stirring scene of a theatre consumed by fire, it starred three men who would become great directors very soon: Sjöström, Stiller, and Georg af Klercker.

Not to mention the von Sternbergs (I liked An American Tragedy much more on this outing), the Scope revivals (Man of the West, Ride Lonesome in a handsome digital restoration from Grover Crisp), my first viewing of Duvivier’s La Bandera (1935), the Monta Bell items (most notably the incessantly energetic Upstage from 1926), and on and on.

What can Gianluca Farinelli, Peter von Bagh, and Guy Borlée, along with their devoted staff members, do for an encore? Bravo! Now take a rest.

Standing Room Only for the rarely seen Children of Divorce (Sternberg/ Lloyd, 1927).