Archive for the 'Silent film' Category

American (Movie) Madness

Grover Crisp and Lea Jacobs outside the University of Wisconsin–Madison Cinematheque.

DB here, again:

He holds sway over thousands of movies and the transfer of hundreds of DVDs. At home he has a high-definition set, but he gets local channels on a rabbit-ears antenna. If that isn’t a working definition of a Film Person, I don’t know what is.

Over the years our UW Film Studies area has hosted many visiting Film Persons, including archivists Chris Horak, Mike Pogorzelski, Joe Lindner, Schawn Belston, and Paolo Cherchi Usai. (1) Being a department centrally interested in film history, we’re eager to screen recent restorations and learn the ins and outs of film archivery.

This year our Cinematheque screened several Sony/ Columbia restorations, running the gamut from Anatomy of a Murder to The Burglar. We wound up our series, and our season, with a stunning print of Frank Capra’s American Madness (1932). To conclude things with a bang, Lea Jacobs, Karin Kolb, and Jeff Smith brought Grover Crisp, Sony’s Senior Vice President of Asset Management, Film Restoration, and Digital Mastering.

Kristin and I had met Grover at the Cinema Ritrovato festival in Bologna, and after hearing him introduce some restorations, we knew he had to come to Madison. It was a Bologna screening of American Madness that convinced me that we had to show this sparkling print on our campus. Fortunately for us, Grover squeezed a Madison visit into his schedule and suffered the caprices of American Airlines’ delays. We had about two days of his company.

It was a great learning experience. On Thursday 8 May he addressed our colloquium, where he showed two shorts: a 1933 Screen Snapshots installment explaining the process of motion picture production, from script to final product, and a trim 75-second short by his colleague Michael Friend tracing the evolution of filmmaking technology. On Friday Grover introduced American Madness and took questions.

Just a note about terminology: Archives engage in both film preservation and film restoration. Preservation means, as you’d think, saving films for the future. This involves maintaining the materials (prints, negatives, camera material, sound tracks) in surroundings that minimize harm and deterioration. Restoration demands more resources. It involves trying to create an authoritative version of the film as it existed in some earlier point in history. But that’s a complicated matter, as we’ll see.

Archives and assets

Grover brings a Film Person’s sensitivity to the mission of film preservation. What does that mean? For one thing, he takes the long perspective. Film archivists think about how to store and maintain films for decades, even hundreds of years. In an industry geared to short-term cycles, booms and busts and jagged demand curves, a commercial archivist like Grover, or Schawn of Fox, has to reconcile traditional museum standards with market demands, strategic release considerations, and current studio policies. In short, he has to think both about saving the film for a century and about hitting a DVD street date.

Grover explained his obligations at Sony Pictures Entertainment. He manages all film and television materials. That means preserving everything for any future use and restoring some items for video and theatrical screening. It also means that he keeps abreast of current TV and film productions. This gives him a chance to “embed archival needs” into production and postproduction processes. For example, from 1991 to the present, YCM separation masters are prepared for every film. (2) And today, when a film is finished and output digitally onto a negative for release prints, another negative is assembled from the camera negative, the most pristine source, and that goes into cold storage.

Grover supervises a staff of about twenty-five people, six of whom are overseeing film laboratory and audio work full-time. Unlike other studio archives, Sony does not hand off preservation tasks to outside companies. Being a Film Person, Grover asks that for films a new negative be created, and fresh screening prints be prepared.

What impelled a big company like Sony to invest so much in preservation and restoration? Grover explained that the rise of home video taught most studios that their libraries had some value. In particular, executives were impressed by Ted Turner’s 1986 purchase of MGM for its library, which he could recycle endlessly on TBS. They realized that the libraries were genuine assets. Old movies enhanced the firm’s value (if it were to be sold, as many were in those days) and could be exploited through new media platforms, like cable.

The arrival of DVD made all the studios return to their libraries to make high-quality versions of their top titles. Now the high-definition format of Blu-ray will re-start restoration because of the leap in quality it offers.

Sony moved early, partly because it understood new media. When Sony bought Columbia Pictures in 1989, the Japanese executives envisioned a synergy between Sony’s hardware and a movie studio’s software. “One of the first things they asked,” Grover recalls, “was, ‘What’s the condition of the library?’” Soon afterward, Sony set up the first systematic collaboration between studio archivists and museum-based archivists. The Sony Pictures Film Preservation Committee included archivists from Eastman House, the Library of Congress, UCLA, MoMA, the Academy, and other institutions. In addition, Grover modeled Sony’s restoration policies on the exemplary work of legendary UCLA archivist Bob Gitt (whose work on sound restoration we’ve already saluted in another entry).

Digital restoration has been part of the Sony program. The 1997 restoration of Capra’s Matinee Idol (1927), from a Cinémathèque Française print, was the first live-action high-definition restoration from any studio.

Sony holds between 3600 and 5000 titles. It’s impossible to be more precise at this point because in hundreds of cases the rights situation is uncertain. But of the core library, about half to two-thirds of the films are restored. Crisp’s team is at work on about 200 titles at any moment! Many more are restored than warrant DVD release, but they may be available On Demand and via TCM, which has recently acquired cablecast rights to several older Columbia titles.

Restore, yes! But what, and how?

We’re grateful for preservation, but for cinephiles, restoration holds a special thrill. A “restored” Intolerance or Napoleon or von Sternberg movie gets us salivating. This year Cannes ran nine restorations on its program.

But what is a restoration?

We expect that a restoration will provide a film with a better-quality image or soundtrack than we’ve had so far. We often expect as well that a restoration will provide a more complete version of the title. Yet there are problems with both expectations.

First, who’s to say what the quality of the original is? Grover encountered this difficulty in restoring Funny Girl. It was released in the classic Technicolor dye-transfer process, usually considered the gold standard for color cinematography. He assembled five original Technicolor prints and all of them looked different. It turns out that Technicolor prints varied quite a bit. (3) The kicker was that Grover couldn’t make the new dye-transfer 35mm print of Funny Girl match any of these reference prints. That didn’t stop it looking fabulous when it premiered in LA.

What about restoration that adds footage to an existing version of a movie? My previous blog entry mentioned an example, the wild and crazy Nerven (1919), to be issued on DVD by the Munich Film Museum. Stefan Drössler, Munich’s curator, has done a remarkable job of incorporating new footage into the longest version of Nerven to date. (The new material includes “living intertitles,” in which actors drape themselves around gigantic letters.) But Nerven remains incomplete, lacking about a third of its original material.

What about restoration that adds footage to an existing version of a movie? My previous blog entry mentioned an example, the wild and crazy Nerven (1919), to be issued on DVD by the Munich Film Museum. Stefan Drössler, Munich’s curator, has done a remarkable job of incorporating new footage into the longest version of Nerven to date. (The new material includes “living intertitles,” in which actors drape themselves around gigantic letters.) But Nerven remains incomplete, lacking about a third of its original material.

Moreover, it’s possible to “over-restore” a film. That is, by adding footage culled from many versions, the restorer may be creating an expanded version that nobody actually saw.

Original version? What does that mean? Paolo Cherchi Usai has reflected on this at length. (4) Is the original what the film was like on initial release? This is tricky nowadays for new titles, because as Grover pointed out, most films are “initially released” in several versions. Since Hollywood filmmaking began, different versions have been made for the domestic and the overseas markets, and often the overseas versions are longer. Sometimes a film opens locally or at a film festival and then is modified for release. Major films by Hou Hsiao-hsien and Wong Kar-wai have played Cannes in versions longer than circulated later.

Now suppose that the film was modified by producers or censors for its initial release somewhere. If you can determine the filmmaker’s wishes, should you restore the film to what she or he wanted it to be? That flouts the historical principle of getting back to what people actually saw. Consider the shape-shifting Blade Runner. Only now, twenty-five years after its release, has the U. S. theatrical version appeared on video.

Or what do we do when a filmmaker, after the release, decides that the film needs to be changed? Late in life, Henry James felt the urge to rewrite many of his novels, and the revised versions reflect his mature sense of what he wanted his oeuvre to be. Why can’t a filmmaker decide to recast an older film? Such was the case with Apocalypse Now Redux and Ashes of Time Redux. Since the later version represents the artist’s latest viewpoint, should that be the authoritative version?

Grover encountered a variant of this problem when he invited one cinematographer to help restore a film. The cinematographer’s own aesthetic and approach to his work had evolved over the years, so he started to tweak things in a way that was taking the look of the film to a level much different than the original achievement. Grover had to steer him back to respecting the film’s original look.

On the brighter side: Grover brought in master cinematographer Jack Cardiff to advise on the restoration of A Matter of Life and Death. Cardiff said that one scene needed a “more lemony” cast. Grover tried, but each time Cardiff said it wasn’t right. Finally, Grover confessed that he just couldn’t get that lemony look. Cardiff nodded. “Neither could I.”

Grover offers this nugget of wisdom: It is almost impossible to get an older film to look the way it does when it was originally released. The color will never look as it did, nor will sound sound the way it did. Film stocks have changed, printing processes have changed, technology in general has changed. Every version is an approximation, though some approximations may be better than others. Take consolation in the fact that even when the movie was in circulation, it may have already existed in multiple versions.

What do consumers want?

All archivists explain that compromises enter into the preservation process down the line. One of the revelations of Grover Crisp’s visit was the awareness of just how many of these compromises come into play, and how some of them are tied to what DVD buyers expect.

Many films from Hollywood’s studio era are soft, low-contrast, and grainy. Project a 1930s nitrate copy today, and though it will be gorgeous, it’s likely to look surprisingly unsharp. Things apparently didn’t improve when safety stock came along in the late 1940s; projectionists complained that those prints were even softer and harder to focus than nitrate ones. As recently as the 1970s, films were not as crisp as we’d like to think. I’ve examined the first two parts of The Godfather on IB Tech 35mm originals, and though they look sharp on a flatbed viewer, in projection the grains swarm across the screen like beetles. (I should add that many of today’s films also look mushy and grainy in the release prints I see at my local.)

But I think that DVD cultivated a taste for hard-edged images, perhaps in the way that music CDs cultivated a taste for brittle, vacuum-packed sound. It’s not surprising, then, that video aficionados are often startled when a DVD release of a classic movie looks far from clean. This is not always attributable to a film’s not being cleaned up to the fullest extent the technology allows. Some films are inherently grainy, gritty, or soft-looking. With the advent of Blu-ray and HD imagery for the home, those films’ look is often mistaken for problems with the transfer, or signs that the distributor didn’t care enough to spend the money to thoroughly make it new. “New” in this case means contemporary.

So there are compromises, according to Grover, that the studios are having to deal with:

What do do about a film that is really grainy? Do you remove the grain, reduce the grain, leave the grain alone? Everyone seems to have a different answer, and it often puts the distributor in a difficult situation. These are questions that will be answered over time, as the consumer gets used to seeing images in HD that truly represent the way a film looks.

Another compromise involves sound. “Now you’re getting to an ethical area,” Grover remarks. In restoring early sound movies, Sony removes only clicks, pops, and scratchy noises (while still keeping the original, faults and all, as a reference). Sound problems are compounded in films from the early 1950s. Many releases at that time were shot in a widescreen process but retained monaural sound. Yet avid DVD buyers want multitrack versions to feed their home theatres. “If it’s not 5.1, we get complaints.” So Grover’s engineers “upmix” mono, as well as two-channel stereo, to 5.1—though they strive to keep the 5.1 minimal and retain as much authenticity as possible. Not on every film, of course: often the original mono track is included on the DVD.

On the positive side, Sony held the original tracks for Tommy (1975), originally released in Quintaphonic. (Old-timers will remember that audiophiles were urged to upgrade to this, and some LPs were released in that format.) Grover was pleased that he could replicate the theatrical version’s 5-channel mix on the DVD. (More details here.)

Now for a hobby horse of mine. The 1950s-1960s standards for multichannel sound were not those of today’s theatres. Today’s filmmakers funnel important dialogue through the front central speaker. But in multi-track CinemaScope and other widescreen formats, dialogue was spread to the left and right speakers as well, and these were behind the screen. That meant that a character standing on screen left was heard from that spot as well. (Remember, these screens might be seventy feet across.) Long ago Kristin and I saw an original 70mm release print of Exodus (shot in Super Panavision) in a big roadshow house in Paris. The ping-pong effect of the conversations between Ralph Richardson and Eva Marie Saint was fascinating.

Today, however, it might be distracting. In a home theatre, where discrete tracks present sound from offscreen left or right, it would seem downright weird. Although Grover didn’t comment on this, it’s clear that the big-screen classics from the magnetic-track era are remixed for DVD to suit current theatrical and home-video standards. This makes it very difficult for researchers to study the aesthetics of sound design from that period. Even if you visit an archive, that institution almost certainly isn’t able to project the film in a multi-channel version. (5) Is it too late to ask DVD producers to replicate, on a second soundtrack, the original channel layout? This would be a big favor to the academic study of the history of sound, and some home-theatre enthusiasts might develop a taste for the old-fashioned sonic field.

Last questions

Q: Do Grover and his colleagues take notice of online chat about DVD releases?

A: Yes, because it’s important to know what many participants in those conversations want from a film’s release, and they may also know things (from a hardcore fan’s pespective) about a film that is useful to know. Grover’s staff members can learn about missing scenes and other variant prints. But sometimes the Net writers are working from incomplete information and can get things wrong. A fan fervently announced that one word was intelligible in the “original” version of a film but not on the DVD. Yet the theatrical release version muffled the word. It turns out that the word was audible in a remixed TV version, which the fan had used as reference. Likewise, one critic who found the color on the Man for All Seasons Special Edition DVD too vibrant was evidently using a VHS version as the reference point. (For what it’s worth, the color in the Man for All Seasons theatrical release I saw was extremely vivid.) And Grover and his colleagues never intervene in the online debates.

Q: Why do DVDs seem different from projected prints—often much sharper?

A: An original film frame, in camera negative, has more resolution than can be captured in a print. Most prints are a generation or two past the material that a DVD transfer uses, so they gain a certain softness. Granted, however, in making high-definition video masters sometimes the tools to sharpen and de-grain the image are overused.

In addition, it’s generally a good idea to get your home video display calibrated. Most home displays are way too bright, sometimes brighter than a theatre screen. If you darkened the room and had the display dialed down, DVDs would look more film-like.

Q: When will we get the Boetticher westerns?

A: It’s the most frequent question Grover gets asked. Soon, soon: A boxed set of restored titles is on the way.

Q: And what about all the Capra titles?

A: Sony plans to restore each of them. Columbia struck many prints of them, and so there is some negative wear. Some negatives no longer exist. On one title, Say It with Sables (1928), Sony has neither negative nor prints.

There’s a too-good-to-be-true backstory here. Capra had a ranch in Pomona, which upon his death was bequeathed to Pomona State University. After some years, people found in a locked stable his private collection of prints struck in 1939. The cache included Lost Horizon, You Can’t Take It with You, It Happened One Night, and the best-quality print of Mr. Smith Goes to Washington Grover had yet seen. There were also photographs Capra had shot of premieres and vacations. Thanks to the good offices of Frank Capra, Jr., Sony acquired the prints and used them in its restorations.

As for American Madness, Grover called it a “training film” for later Capra productions. The theme of faith in the little man, manifested in a bank run that tests a humane banker’s alliances in the community, points ahead to It’s a Wonderful Life and other films. Sony holds a complete soundtrack and a nearly complete original negative. UCLA held a complete nitrate print donated by the Los Angeles Parks and Recreation Department; evidently the film was screened in parks as public entertainment. That print wasn’t in good condition, but it allowed Grover’s team to fill out certain scenes. The nitrate print’s footage is noticeably lighter and grainier in a few places. American Madness wasn’t a digital restoration, but if it were done today Grover would probably use CGI to blend in the alien footage.

Talkies, with a vengeance

It was fine to see the film again; its brisk inventiveness held up. The gleaming and geometrical images of the opening, which acquaint us with the daily routine of opening the bank vault, might have come out of Metropolis. One helter-skelter montage sequence, complete with canted framings and chiaroscuro lighting, looks forward to Slavko Vorkapich’s delirious contributions to Mr. Smith and Meet John Doe.

The tactics of depth composition that we find in many 1930s movies reappear here, and the illumination has dashes of noir.

I especially like the dynamic pans that carry Walter Huston and Pat O’Brien in and out of the main office; I suspect that they’re cut together faster and faster as the climax gets near. And the huge set of the bank lobby, publicized at the time as the biggest set yet built on the Columbia lot, remains not only impressive but functional. It establishes a cogent geography to which Capra adheres strictly while filming it from a great variety of angles.

But this is not a treat just for the eyes. American Madness flaunts its mastery of emerging talkie technique. The rising action is accentuated by the steady increase in volume of the growing crowd in the bank lobby. The clerks’ scattershot morning chat in the vault is captured in microphone distances and auditory textures that suggest a hollow, sealed-off space. Hawks’ rapid-fire patter in Twentieth Century (1934) has an antecedent here, and at the same studio. The actors speak at a terrific clip, scarcely pausing between lines, and sometimes the dialogue overlaps. We even get competing lines, two or more speeches rattled off at once. (And did Hawks get the idea for His Girl Friday’s variants on telephone chatter from O’Brien working the receivers at the climax?)

In films like this, American movies talk American. Consequently, I’m inclined to regard as an in-joke the glimpse we get of a marquee that’s advertising another Columbia picture: Hollywood Speaks.

Thanks to Grover and Sony Pictures Entertainment for a wonderful series and an enlightening brace of talks. American Madness is available on the DVD set The Premiere Frank Capra Collection.

(1) Chris Horak has been head archivist at George Eastman House, the Munich Film Museum, Universal, and the Hollywood Museum; he’s now Director of the UCLA Film & Television Archive. Mike Pogorzelski is Director of the Film Archive for the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences; Joe Lindner is Preservation Officer there. (Both are former Badgers.) Schawn Belston is Vice President of Asset Management and Film Preservation at Twentieth Century Fox. Paolo Cherchi Usai is Director of ScreenSound Australia, the national archive, and director of the recent film Passio. Kristin interviewed Mike and Schawn for this blog entry.

(2) YCM separation masters are made by copying a color film onto three black-and-white films. Thanks to filtering, these preserve color luminance at the different values of yellow, cyan, and magenta. Since these monochrome versions are not as susceptible to fading, they can be used for archival preservation. Combined, they can recreate the original color image.

(3) This confirms my impression when I’ve seen different Technicolor prints of the same title. You sometimes get this effect with a composite print, in which the color values change from reel to reel. Anecdotally, I’ve heard that Technicolor staff in the studio days would sort reels according to their dominant color (“That’s the yellow pile over there”).

(4) See Chapter 7 of Silent Cinema: An Introduction (London: British Film Institute, 2000). This book, incidentally, is a good introduction to the sheer fun of archive work. Others communicating the same enthusiasm are Roger Smither and Catherine A. Surowiec, This Film Is Dangerous: A Celebration of Nitrate Film (Brussels: FIAF, 2002) and Dan Nissen et al., eds., Preserve Then Show (Copenhagen: Danish Film Institute, 2002).

(5) This problem renders the activities of Britain’s National Media Museum in Bradford all the more important. There you can see classic films in a great many formats and sound arrays.

American Madness.

15 June: Thanks to Kent Jones for correcting a name slip.

19 June: Breaking News: Grover has just been promoted to Senior Vice President for asset management, film restoration, and digital mastering. Nice timing; wish we could say our blog put him over the top, butVariety explains that it was good old-fashioned talent. Congratulations to Grover!

Coming attractions, plus a retrospect

Invasion of the Brainiacs

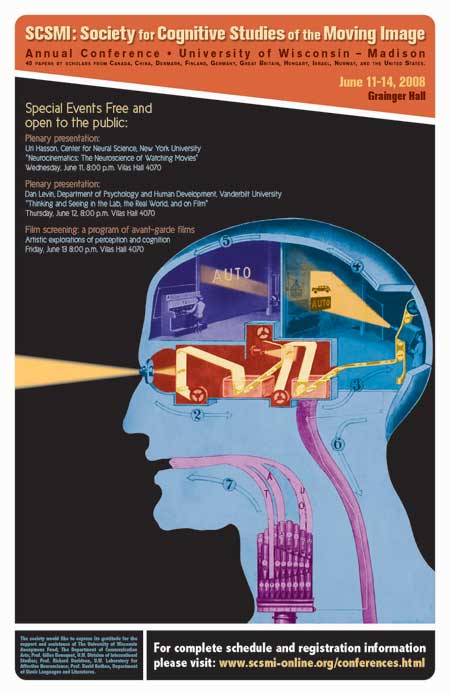

First, the event that will occupy us through next week: the annual conference of the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image, a group founded in 1997. This year’s gathering brings researchers from Britain, Germany, Hungary, Israel, Turkey, Canada, China, and the Nordic countries, as well as many from the U. S. The meeting is here in Madison, from 11 to 14 June.

In over forty sessions, researchers will be talking about how we respond to movies, TV shows, and videogames. How has digital imagery changed our experience of cinema? How does film music enhance our emotional response to the story? How do films guide our visual attention to one part of the screen, and how much do viewers differ in this? How do we respond when movie characters behave inconsistently?

I’ve already blogged and bragged about our event here, but now I want to highlight four attractions. If you’re in or near Madison, you might want to stop by; and in any case, you might want to check the links mentioned below.

For some years Professor Uri Hasson of New York University’s Center for Neural Science has studied how the human brain responds during film viewing. Using fMRI techniques, he has discovered that Hollywood films, such as those by Hitchcock, have created remarkably similar responses across a variety of viewers. Art films, he says, may require just as much concentration, but they will elicit less convergent reactions. He’ll present the fruits of his research on June 11. You can learn more about Uri’s research here.

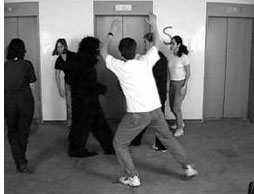

On June 12, Professor Dan Levin will lecture on “Thinking and Seeing in the Lab, the Real World, and on Film.” Levin has been actively studying how viewers’ concentration, watching a film or in real life, encourages them to overlook actions or changes taking place in front of them. He showed the power of “inattentional blindness” in his famous “gorilla-suit” experiments. Filmmaker Errol Morris recently interviewed Levin for The New York Times about continuity errors in films. You can read more of Dan’s fairly mind-bending work here.

On June 12, Professor Dan Levin will lecture on “Thinking and Seeing in the Lab, the Real World, and on Film.” Levin has been actively studying how viewers’ concentration, watching a film or in real life, encourages them to overlook actions or changes taking place in front of them. He showed the power of “inattentional blindness” in his famous “gorilla-suit” experiments. Filmmaker Errol Morris recently interviewed Levin for The New York Times about continuity errors in films. You can read more of Dan’s fairly mind-bending work here.

NB: 12 June 2008: In fact, the gorilla-suit experiment was conducted by Dan Simons, not Dan Levin. The last link takes you to Simons’ article. Both Dans work in the area of attention and “change blindness,” and they have collaborated on several projects. I apologize for the error.

There is a registration fee for the conference’s day events, but these evening lectures are free and open to the public. Each begins at 8:00 PM and will be held in 4070 Vilas Hall, 821 University Avenue.

The final night of the conference is devoted to a screening of experimental and avant-garde films that provoke questions about how we respond to cinema. There will be a discussion of them afterward, which will include two of the filmmakers, Joseph Anderson and J. J. Murphy. This screening, open to the public, starts at 8:00 PM in 4070 Vilas.

During the conference, one event is devoted to a discussion of Noël Carroll’s The Philosophy of Motion Pictures. This book is a remarkable effort to mount a systematic philosophy of film, TV, and related media. It’s full of provocative claims (e.g., that cinematic movement isn’t an illusion) and nifty examples. Noël is a polymath, with two Ph. D.s and more books and articles than anybody, including he, can count. Four other scholars will criticize some aspect of the book’s arguments, and Noël will respond. (One of those critics, Lester Hunt, is a philosophy prof here who maintains a wide-ranging website and a blog that often touches on film.) There should be some fireworks.

There are other brainiacs coming, many of them pioneers in this area: Joe and Barb Anderson, Murray Smith, Torben Grodal, Patrick Colm Hogan, Carl Plantinga, Paisley Livingston, Sheena Rogers, Dan Barratt, and Tim Smith (aka Continuity Boy), and too many others to include here. In all, I’m proud of what our local team, with the energetic Jeff Smith as point man, has accomplished in setting up this jamboree.

As regular readers know, I think that cognitive research into cinema holds great promise. It brings together a group of scholars from different disciplines who want to understand, in an empirical way, how movies work. The field is very young, and it’s not the only way to go; but it has a lot to contribute to our understanding of media, and maybe our understanding of the mind too.

Up to now SCSMI has been quite an informal group, but now we have a more systematic organization. We have officers, bylaws, and a sense that our research is coalescing around key ideas, about which there is lively and congenial disagreement. And, because there are more people who want to get involved, we’ll start meeting every year. The 2009 gathering is slated for Copenhagen.

I hope to dash off a blog entry in medias res. We’ll also do our best to introduce our colleagues from overseas and from the Coasts to the glories of brats, cheese, beer, and of course The House on the Rock.

By the way, you might want to check on this cognitive scientist, who claims that every one of us can see into the future (but only a little bit).

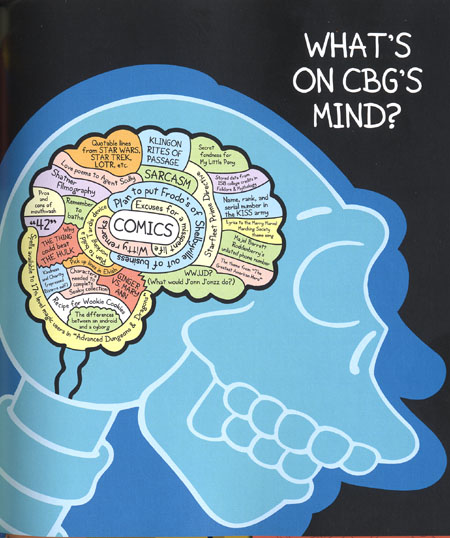

Kristin and the Comic-Book Guys (100,000 or so)

Speaking of gatherings of like-minded individuals, TheOneRing.net people have invited Kristin to take part in their panel on the upcoming Hobbit project at Comic-Con in San Diego, on Friday, July 25 at 10 am. She hopes to blog from among the multitudes.

A new website and a nervous DVD

There’s a new and attractive website up and running. Sponsored by the Museum of the Moving Image in Astoria, NYC, Moving Image Source is a vast project packed with links, research data, and essays about films both classic and contemporary. The first posse of writers includes Michael Atkinson, Jonathan Rosenbaum, Ed Sikov, Melissa Anderson, and other luminaries. The topics range from Andy Warhol and Howard Hawks to Werner Herzog (an interview). Steered by Dennis Lim, this is bound to be an essential watering hole for everybody interested in film history and criticism.

Speaking of film history, an important film is coming to DVD. Robert Reinert’s 1919 Nerven, which I wrote about in Poetics of Cinema, has been restored by Stefan Drössler and his crew at the Munich Filmmuseum. This is one of the strangest movies of the silent era. The plot, as Chris Horak points out in his accompanying essay, is steeped in Spenglerian melancholy, reminding us that Expressionism could be politically conservative as well as revolutionary. The visuals are at once monumental and unstable, like boulders teetering over a precipice. I try to analyze them in another contribution to the DVD booklet. Drössler has contributed an essay on the process of restoration.

Nerven was a box-office fiasco and never achieved the fame of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. In a way, it is more disturbing than that official classic because Reinert’s alternation of frenzy and somnambulism takes place in a more or less solid world, like ours. Frantic scenes of street fighting mix with brooding images of a bourgeoisie sliding into religious possession or straight-up lunacy. It is not every day that you see a movie that begins with a man throttling his wife and then lovingly refilling their parakeet’s water cup. If you’re a fan of wild deep-space imagery way before Citizen Kane (as above), this one’s for you. And yes, it will have English subtitles.

Nerven will be available later this summer from the Filmmuseum’s shop. It joins an abundance of other fine DVD titles, such as Borzage’s The River and a collection of Walter Ruttmann’s works.

Retrospect: In Europe they do things differently?

Because we see a very thin slice of foreign-language cinema, audiences underestimate the extent to which European films often imitate Hollywood. Surely the cultures of the great continent would never stoop to the crassness of our movies? A trip to any multiplex in Paris or Berlin would probably disabuse people of this notion. The current instance is the reigning French hit Bienvenue chez les ch’tis (Welcome to the Sticks), apparently a fish-out-of-water tale that would induce groans from our intelligentsia.

Kristin has already written about this phenomenon here. I found some supporting evidence last week while scrabbling through an old folder for our Film History revision. It was a 2002 pamphlet from the Filmboard of Berlin Brandenburgh GmbH, a publicly limited company coordinating German state funding. The text laid out a set of guidelines, in English, for productions that the Filmboard would support. After explaining that the judges must consider financial return as well as cultural factors, the guidelines insist that the quality of the screenplay is of paramount importance. What makes a good screenplay?

The success of a film decisively depends upon whether the audience can engage enthusiastically with the actors on the screen. An audience looks for strong central characters whose fates it can identify with. The hero or heroine should have goals and needs and should have an emotional effect on an audience. Further dramaturgical criteria:

There must be a concrete goal, which at the end of the story is either reached—or not.

There should be a risk involved for the central character in not reaching his/her goal.

The goal is perhaps difficult to reach, and the struggle to do so should bring the central character into conflict. The audience sympathizes with the story when, for example, the hero or heroine follows the wrong goal, makes mistakes, or experiences a crisis.

This sounds easy to understand. But writing screenplays is more complex.

*The central character should have subconscious needs. He/ she should lack an important human quality and only gradually experience this for him/herself.

*At the end of the story the central character should come to know his/her unconscious needs and gain a satisfactory recognition about him/herself and life in general, which can be formulated in the emotional subject matter of the film.

*The central character should undergo a process of development, as characters that do not develop are boring. Moments of decision in stories are the key for good character development.

The passage lays out a lot of what U. S. screenplay manuals have been asserting for decades (notions that Kristin and I have analyzed in various books). This is still more evidence that the Hollywood model, with its goal-oriented chain of causes and effects and its protagonist who improves through a “character arc,” holds sway far beyond our own shores. Whether it should be so widespread is another question, but for Kristin and me, this template or formula is a bit like the sonnet or the well-made play: a form that can yield results good, bad, and indifferent. The point is to take the form seriously enough to understand what makes it work.

From Comic Book Guy’s Book of Pop Culture (New York: HarperCollins, 2005), n.p.

Hands (and faces) across the table

DB here:

In books and blogs, I’ve expressed the wish that today’s American filmmakers would widen their range of creative choices. From the 1910s to the 1960s (and sometimes beyond), US filmmakers cultivated a range of expressive options—not only cutting and camera movement but other possibilities too. Studio directors were particularly adept at ensemble staging, shifting the actors around the set as the scene develops.

You can still find this technique in movies from Europe and Asia, as I try to show in Figures Traced in Light and elsewhere on this site. But it’s rare to find an American ready to keep the camera still and steady and to let the actors sculpt the action in continuous time, saving the cuts to underscore a pivot or heightening of the drama. Now nearly every American filmmaker is inclined to frame close, cut fast, and track that camera endlessly. I’ve called this stylistic paradigm intensified continuity.

As Los Angeles agent and former editor Larry Mirisch once put it in conversation with me: “They used to move their actors; now they move the camera.” Most of today’s prominent directors prefer kinetic camerawork and machine-gun cutting. This tends to make their staging rather simple and static: we get stand-and-deliver or walk-and-talk (subject of a blog entry here).

The result is a split in contemporary American style. Action scenes are often gracefully and forcefully choreographed (though sometimes the editing fuzzes up character position and overall geography). By contrast, conversation scenes, which could be choreographed as well, are handled either as a Steadicam walk-and-talk or simply as seated actors talking to one another, with cuts breaking up the lines and the camera on the prowl. (I discuss some examples in The Way Hollywood Tells It, pp. 128-173.) (1) You sometimes suspect that today’s directors are most at home shooting lots of people hunched over workstations, making the principal form of suspense a LOADING command.

Don’t get me wrong. Like all styles, intensified continuity isn’t a bankrupt option; many fine directors, from the Coens to Michael Mann, have worked vigorous variants on it. What I’m arguing for is more plurality, more tones in the director’s palette. I’ve revived these cranky ideas in discussing a single shot, this time in Variety. Today’s blog entry expands on that brief piece, so you may want to hop over to it here before reading what follows.

Directing us

One task facing any director is to direct—not only actors but us. The filmmaker must direct our attention to what’s important for responding to the drama at any moment. Since the late 1910s, we’ve known that close-ups and frequent cutting do just that. Tight framings and rapid cuts can steer the audience’s attention through a scene. So the question becomes: How can you direct attention without using close views and fast cutting?

Well, for one thing you can place the main action in the center of the picture format. If there are several points of interest in the shot, which is usually the case, you can arrange them symmetrically around the central zone of the shot—in film, usually an zone just above the geometrical center of the picture format. You can also position your main players so that the most important ones are closer and/or facing toward the camera. By turning a character away from the camera, you can drive the audience’s eye to someone else. There are other pictorial cues worth mentioning (lighting, color combinations, patterns in the set design), but these will hold us for now. Add in movement—characters shifting their position, especially coming closer to the camera—and you have a suite of cues that a film shot can provide.

Apart from these purely compositional factors, you the director can exploit some cues that are part of our social proclivities. When we watch other people, we’re attracted to areas of high information—which, for creatures like us, are faces and hands. Faces send signals about what people are thinking and feeling, with the areas around the eyes and mouth telling us most. Hands are the source of gestures, as well as potential threats. And of course if someone is speaking and others are listening, we are likely, all other things being equal, to look at the speaker.

The crucial fact is that in ensemble staging all these cues, and more, are at work at the same time. The director’s skill is orchestrating them so that they support one another, guiding us to see this or that. (On rare occasions, the director will use them to misguide us, but let’s stick with the default for the moment.) For a long time, filmmakers knew intuitively how to coordinate these cues to create rich and intricate shots; I fear that they no longer know how. (2)

That’s what makes one passage in Paul Thomas Anderson’s There Will Be Blood of interest to me. The scene presents Paul Sunday explaining to Daniel Plainview that there’s oil on his family’s property. Daniel and Paul are bent over a map on a tabletop, with Daniel’s assistant Fletcher Hamilton and Daniel’s son HW watching. The scene is presented in a single shot, with a slight camera movement forward at the start.

The composition could hardly be simpler: four people lined up, three at the edge of the table. The heads cluster around the center of the format, with HW lower and off-center; no surprise that he’s the least important character in the scene (though his question to Paul foreshadows action in the film to come). Paul is explaining where the oil is, and the two men’s faces and hands command our attention as they speak.

Many directors would have cut in to a close-up of the map, showing us the details of the layout, but that isn’t important for what Anderson is interested in. The actual geography of Plainview’s territorial imperative isn’t explored much in the movie, which is more centrally about physical effort and commercial stratagems.

Questioning Paul about his family, Daniel turns slightly away. This clears a moment for HW to ask about the girls in Paul’s family, and for a moment our attention is steered to the right, to pick up their interchange.

Then Fletcher asks about the farm, and as Paul and Daniel tilt their faces to him, he earns his place in the center of the frame. Before, when we could see the faces of the two men closest to the camera, he was subsidiary, but now he becomes salient. On the left, Daniel shifts away uneasily, turning almost completely away from the camera. In answering Fletcher, Paul turns away in the opposite direction, as if shy or guilty; his awkward gesture of stroking his hat seems to confirm Daniel’s doubts about him.

During a pause, Paul turns back to stare directly at Daniel, saying quietly, “The oil is there.” At the same time, Daniel, still turned away, is exchanging a glance with Fletcher. At this point, Anderson’s training of us pays off: we’re ready to detect the slight shift in Fletcher’s eyes, which confirms that Daniel’s looking at him. “Watch their eyes,” as John Ford liked to say.

Paul sets out to leave, and he refuses the invitation to stay the night. At this point comes the scene’s biggest gesture. Daniel raises his hand, in the dead center of the frame.

Spreading his long, thin fingers, Daniel commands our attention. He seems at once to be halting the young man and threatening him. But the gesture becomes the prelude to a handshake. Daniel’s characteristic blend of bluff assurance, friendliness, and aggressiveness are packed into this single gesture. (At the climax, other gestures will recall this one.)

Daniel steps closer to Paul, blocking out Fletcher, to make his threat: If he travels so far and doesn’t find oil, he’ll find Paul and “take more than my money back.” Paul agrees and moves away. “Nice luck to you, and God bless.”

The men watch Paul leave the building. End of scene.

Without any close-ups or cutting, Anderson has skillfully steered us to the main points of the scene, which are carried by the performers. The drama builds through small changes of position, shifts of weight, and facial expressions that accompany the dialogue. (The somber, plaintive music adds an uneasy edge.) Daniel seems more threatening when we don’t see his reaction, and Anderson’s camera forces us to scrutinize Paul’s expressions and body language for signs that this is a scam. It takes confidence to make a raised hand the climax of a scene, but the gesture gains its force by being the most aggressive moment in an arc of quietly accumulating tension.

All the principles involved here—frontality, spacing of figures, slight shifts of compositional focus, actors’ body language—are simple in themselves, but they gain a strong impact by cooperating with one another. The scene’s quiet obliqueness is characteristic of the film, which, at least until the last few minutes, carries us along with hints about where the action might go and what drives its characters.

Yet simplicity shouldn’t imply simplification. Anderson’s willingness to give the shot several points of interest, some more stressed than others, creates an understated tension. The shot’s gravity stems from its conciseness, a quality that Anderson admires in 1940s studio films like The Treasure of the Sierra Madre.

Two more tabletops

The staging strategies Anderson uses aren’t new, as I’ve suggested. They’re part of the history of film as an art form, and many directors have continually relied on them. I don’t think that this is always a matter of influence, although surely filmmakers learned from watching earlier films. Often, directors working within similar constraints intuitively rediscover what other directors have already done.

Consider this scene from Kurosawa Akira’s The Most Beautiful (1944). The setting is a plant where Japanese workers, mostly girls and women, are manufacturing bombsights. The workers have vowed to increase production for the war effort, and they are working to the point of exhaustion. The plant supervisors are worried that the pace will take its toll on the girls.

The scene starts with the eldest supervisor studying the output chart, lying on a table below the frame edge. His colleagues are turned away, at the window. He is the one who must decide how to keep the girls healthy and the output steady. The table and the window will be the two poles of the action, and the actors will oscillate between them. The process starts when the eldest retreats to the window, and one comes forward to study the report.

He’s followed by his opposite number, and they echo one other in rubbing their necks. They’re as tired as the assembly-line girls. Their superior turns and says that there’s no point in lowering the quota because the girls are so devoted that they’d push harder anyway.

The men have turned to listen to him, driving our attention to his centered, frontal figure. After the elder has turned away again, the man on the right says that this might be the critical juncture. Remarkably, all three men remain turned from us, creating a slight pictorial tension.

This tension is extended when the supervisor on the left states his confidence in the children, their team leader, and their teacher. This makes the eldest turn around.

The speaker walks to the window, arguing that the girls will succeed, but the leader turns away again dubiously. He doesn’t offer a decision because an offscreen voice announces that a teacher has come to see them, and they all turn to look.

The factory’s problem isn’t solved; the seesawing of the staging has presented that irresolution dynamically. In a single shot, the difficulty of the administrative decision has been expressed in counterweighted movements in and out, by the figures’ frontality and dorsality. Again, it can seem simple, but where a contemporary American director would have given us a prolonged passage of stand and deliver, with intercut close-ups, Kurosawa has created a little ballet out of the men’s uncertainties. Like Daniel’s raised hand, but with even less emphasis, the assistant’s plea on behalf of the girls’ commitment has gained a subtle prominence. Yet all he has done is walk to the window.

I’m not saying, of course, that Anderson took the idea from Kurosawa. Given the initial choice to stage the scene behind a table, and the inclination to present the action in one shot, both directors spontaneously drew on basic staging principles. This is what film directors have always done. So as a finisher, here’s one last tabletop interlude from Cecil B. DeMille’s Kindling (1915). The entire scene is a dense and intricate affair, but let’s pick just one moment. Maggie has become a servant to a rich woman, Mrs. Burke-Smith, and she’s about to be arrested for theft. Detective Rafferty is ready to handcuff her, but Mrs. Burke-Smith changes her mind.

DeMille arranges his actors so that we can’t miss the rich woman’s moment of decision. She is in the foreground, and her face is in the upper center of the frame. The other actors are blocked, so that her expression is the only one we can see clearly at the crucial moment. Her hand gesture, stretching across the central axis of the frame, confirms that she won’t charge Maggie. (For a similar use of “blossoming” actors’ movements in 1910s cinema, go here and look at Figs. 2A10-2A11.) What DeMille knew, Kurosawa discovered afresh, and Anderson hit upon it again.

Strategies of staging, like other principles shaping how films tell stories, lie behind each concrete creative decision the film artist makes. They run as undercurrents through film history, almost never discussed by critics. They form a body of tacit knowledge, flowing across our usual distinctions of period, genre, director, national cinema. We can trace continuities and changes, examining how the strategies are revived, revised, or rejected. They can provide us with subtle but powerful experiences. They constitute a skill set that is available to filmmakers today. . . if any will, like Anderson, seize the chance.

(1) True, Wes Anderson keeps the camera still, but in his frontal, family-portrait framings the cutting and line readings do all the work; dynamic staging isn’t on his menu.

(2) I survey the development of these and other tactics in Chapter 6 of On the History of Film Style. On this site, for one example go here and scroll down to the Bauer material.

All singing! All dancing! All teaching!

Kristin here—

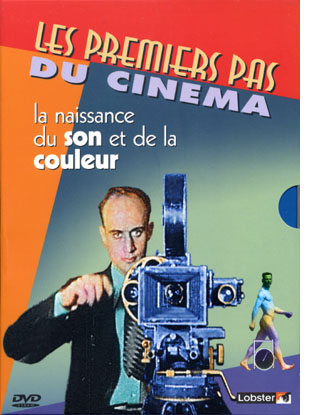

David and I are currently revising our second textbook, Film History: An Introduction, for a third edition due out next year. As part of the research, I’ve been watching two recent DVDs on the early history of sound and color. Both offer valuable resources for those teaching introductory film-history classes, as well as more specialized ones.

Twenty-five years ago, when I last taught a survey history class, the resources for teaching about the innovation of sound were discouragingly limited. The early Vitaphone shorts were as yet unrestored, with most of their accompanying discs damaged or lost. The most famous early sound films were mainly available in mediocre 16mm prints. Showing an “early” sound film often meant a René Clair classic from the early 1930s—a time when the transition to sound was well along, if not over. Le Million or Á nous la liberté demonstrated the artistry that an imaginative director could bring to the early sound cinema, but it wouldn’t give much idea of the struggle inventors and filmmakers went through to create the complex technology.

The same was true for pre-1935 color. There was no way to adequately survey the range of processes and experiments, from early hand painting and stenciling to two-strip Technicolor. The poor 16mm prints of early films often gave no real indication of what they had looked and sounded like when they were made.

Since then archivists have been intensively discovering and preserving films, and in some cases these have been released on DVD. Often these discs are simply collections of films, but documentaries incorporating short films and clips are becoming more common, especially since they make attractive television programs.

Discovering Cinema (Flicker Alley)/Les Premiere pas du cinéma (Lobster & histoire)

A two-DVD survey from the very active Lobster archive in Paris devotes a disc each to sound (2003) and color (2004). Lobster is a private archive started in 1985 by two film enthusiasts, Serge Bromberg and Eric Lange. (The website offers a choice of French or English text.) It began as an effort to discover lost films. Building on its success, Lobster has grown into a major resources for restoring films—both their own discoveries and commissions from other archives and from film companies.

David and I bought this set when it came out. The French boxed set offers a choice of French- or English-language versions. (It’s not region-coded, but it is PAL, which means it won’t play on NTSC players, the standard in the U.S. and some other countries.) The French version isn’t on the Amazon.fr site, but fnac is offering it.

In September, 2007, the American version was released by Flicker Alley. This is another private archive, founded in 2002, also by an enthusiast, Jeffery Masino. The company hasn’t put out many titles yet, but the DVDs available so far are impressive. Flicker Alley collaborates with Turner on restorations, and presumably its catalogue will grow.

Each Lobster documentary is about 52 minutes long, and the supplements include a number of complete films.

The disc devoted to color is subtitled “Un rêve en couleur” and in English the slightly more poetic “Movies Dream in Color.” It’s organized by the three types of cinematic color: Colors and Tints (that is, black and white film painted or dyed), Additive Synthesis (using filters on the projector lens to add color to black-white film), and Subtractive Synthesis (recording separate colors on separate strips of film and combining them in printing).

The disc devoted to color is subtitled “Un rêve en couleur” and in English the slightly more poetic “Movies Dream in Color.” It’s organized by the three types of cinematic color: Colors and Tints (that is, black and white film painted or dyed), Additive Synthesis (using filters on the projector lens to add color to black-white film), and Subtractive Synthesis (recording separate colors on separate strips of film and combining them in printing).

There’s a quick run-through on color in pre-cinema devices: slides, peep shows, and topical toys. The next section gives a splendid demonstration of how stencils were used to hand-color films (such as the unidentified example above), as well as some briefer coverage of tinting and toning.

Moving to additive color systems, the film deals with Friese-Green’s early experiments, Charles Urban’s Kinemacolor, with its brief commercial success, Gaumont’s technically sophisticated Chronochrome, and various lenticular systems. Given that these attempts require special projection, the recreated examples given here are one of the few ways that we can see such films today. All of them proved dead ends, however, so they are of more interest for their technical ingenuity than for their ultimate impact.

The final part of the film turns to Technicolor, founded in 1915. The firm quickly turned away from its early additive experiments and settled on a subtractive system using two strips of film and later, in the 1930s, three strips—resulting in the vibrant hues that many people still think of as the acme of filmic color. “Movies Dream in Color” gives a brief but useful run-down of Technicolor’s progress, through its early two-strip successes like The Black Pirate through the exclusive contract with Disney in the 1932-36 period, and its triumph thereafter as the main color system of Hollywood. There is also some coverage of the two brands that combined all colors on a single negative, Kodachrome and Agfacolor, but the coverage essentially ends in 1939, before either had become widespread.

Incidentally, an in-depth study of Technicolor has recently been published: Scott Higgins’ Harnessing the Rainbow: Color Design in the 1930s.

The filmmakers weave together interviews with a number of prominent archivists, including Paolo Cherchi Usai (co-founder of “Le Giornate del Cinema Muto” festival and now director of Australia’s national archive) and Gian Luca Farinelli (director of the Cineteca di Bologna).

“Learning to Talk” (in the French set “Á la recherche du son”) uses the same group of experts and a somewhat similar three-part organization: “artistic sound” (that is, live sound during the projection of silent films), sound on disc, and sound on film.

The segment on live sound is excellent. It again starts with pre-cinema music and effects for magic-lantern shows and progresses to Reynaud’s hand-drawn Pantomimes lumineuses, with their specially written music. One highlight is documentary footage of a man demonstrating the use of an elaborate sound-effects box, with its brushes, cans of pebbles, and other crank-operated devices that simulated such actions as trains moving and crockery being smashed.

The sections devoted to sound-on-disc and sound-on-film are less well set forth, since the filmmakers try to cover many pioneers in France, the U.S., Germany, and Denmark. Again, several of the devices covered were novelties that led nowhere or that failed for lack of amplification, the use of non-standard film widths, and other reasons.

Once the story reaches the lengthy invention process of the two main American systems, Warner Bros.’ Vitaphone (using discs) and Fox’s Movietone (sound-on-film), it proceeds more clearly. “Learning to Talk” includes some of the Case and Sponable demo films, a Movietone News interview with Mussolini, and a clip from Don Juan. Presumably because of rights problems, no footage from The Jazz Singer is shown.

The bottom line is that the color disc strikes me as the more useful for teachers. The sound one gives good coverage, but again many of the systems discussed are not historically significant to anyone but specialists. For a history of that deals largely with the American innovation of sound, one can now turn to a superb recent DVD.

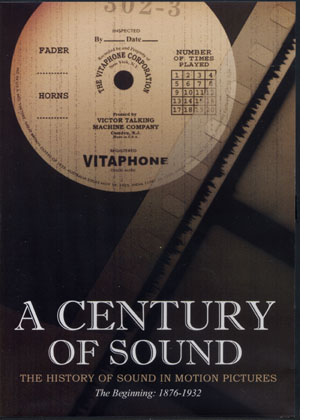

A Century of Sound: The History of Sound in Motion Pictures: The Beginning: 1876-1932 (UCLA Film & Television Archive and the Rick Chace Foundation).

This disc originated in a lecture on early sound by Robert Gitt, who has long been the preservation officer for UCLA’s film archive. Gitt has supervised on the restoration of many important films. In 1991 his team launched the Vitaphone Project. Vitaphone, Warner Bros.’s commercially successful sound system of the 1926-31 period, used phonograph records rather than optical tracks on the film strip. Over the decades many of those discs were damaged or separated from the original reels, and the Vitaphone shorts sat in their cans, reduced to silence.

Gitt and company set about finding as many discs for the surviving Vitaphone films as they could. Over the years they were amazingly successful in tracking them down and rejoining sound and image in a sound-on-film format that can be shown on modern projectors. You can trace the progress of the project since its beginning through its online newsletter, which currently runs from fall, 1991 to winter, 2007/08.

Colleagues urged Gitt to turn his lecture on sound, copiously illustrated with clips, into a DVD. He took the opportunity to expand the talk and to incorporate more and lengthier clips. Most documentaries on film history include only brief clips from any scene. Gitt has wisely opted to include whole scenes, and he has had access to high-quality archival prints of the key early sound films. He also offers early tests made by the companies responsible for innovating sound, as well as documentary shorts they used in selling their processes to industry executives. Rather than writing a script for someone else to read, Gitt appears as presenter and narrator. He humorously admits to the dullness of some of the technical shorts and acknowledges the occasionally silly or racist content of some of the films. At the same time, though, he makes clear what is significant about the examples he presents, and they all become more intriguing than they would if seen individually, out of context.

Colleagues urged Gitt to turn his lecture on sound, copiously illustrated with clips, into a DVD. He took the opportunity to expand the talk and to incorporate more and lengthier clips. Most documentaries on film history include only brief clips from any scene. Gitt has wisely opted to include whole scenes, and he has had access to high-quality archival prints of the key early sound films. He also offers early tests made by the companies responsible for innovating sound, as well as documentary shorts they used in selling their processes to industry executives. Rather than writing a script for someone else to read, Gitt appears as presenter and narrator. He humorously admits to the dullness of some of the technical shorts and acknowledges the occasionally silly or racist content of some of the films. At the same time, though, he makes clear what is significant about the examples he presents, and they all become more intriguing than they would if seen individually, out of context.

The result offers an extraordinary array of clips that teachers could draw upon even if they don’t have time to show the entire lengthy documentary. For Vitaphone there are some of the early shorts, the entire duel scene from Don Juan, extended excerpts from The Better ‘Ole, Old San Francisco, Lights of New York, and others. For Fox Movietone there are scenes from 7th Heaven and Sunrise, as well as George Bernard Shaw’s charming appearance in an issue of Movietone News.

Despite some lively moments, many of the early sound films are slow and clunky, due to the limitations of the available equipment. Gitt balances them by ending with some familiar examples of the imaginative early use of the new technique: the “Paris, Please Stay the Same” number from Lubitsch’s The Love Parade, a generous excerpt from Mamoulian’s Applause, and a portion of I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang (which, be warned, gives away the ending). Teachers whose schedules don’t permit them to devote precious screening time to an early sound feature can give their students a reasonably good sense of the transitional period with such clips.

We’ve all heard the stories about how certain actors’ careers were destroyed by sound, but for the teacher there’s again the problem of how to demonstrate this to classes. Gitt has filled this need as well. Among the bonuses (which are few because so much is included in the film), there is one on the fates of actors. For each Gitt supplies both a clip of the actor in a silent film and in a sound one. The actors whose careers took a nose dive in sound films are represented by Rod La Roque, Norma Talmadge, John Gilbert, and Charles Farrell. Those who successfully made the transition are Ronald Colman, Joan Crawford, William Powell, and Laurel and Hardy. Gitt makes plausible cases why the public responded to each actor as it did.

As the disc’s title implies, it is intended to be part of a series of three documentaries that will cover the entire century. If Gitt continues to get access to the sort of material he presents here, the result should be an impressive overview of the subject and a boon to educators. If in the 1970s and 1980s we had dreamt up our ideal documentary subject for teaching early sound, it would have looked a lot like A Century of Sound—except we couldn’t have imagined all the material that existed in the vaults, waiting to be found and restored.

A Century of Sound is not available commercially. Educators and researchers can request a free copy (with a $10 shipping charge) by downloading a pdf form here.

The Jazz Singer (Warner Bros.)

Released this past October, this three-disc deluxe set marks the first time that The Jazz Singer has been on DVD. (Legally, that is; there was apparently a Chinese bootleg.) It also includes numerous supplements, some of which might be useful for teaching the introduction of sound.

The first disc contains the restored print of The Jazz Singer, a complete version of Al Jolson’s Vitaphone short, A Plantation Act, and some other shorts. One of these is the classic Tex Avery cartoon, I Love to Singa, inspired by The Jazz Singer and starring “Owl Jolson.”

An 85-minute documentary, The Dawn of Sound: How Movies Learned to Talk is the main item on the second disc. It was made by Turner Entertainment and bears a copyright date of 2007. Like so many TV shows, it doesn’t trust enough in the inherent interest of its topic. Rather than explaining the sound systems clearly by type, the writers have opted to try and stress the four Warner brothers as interesting personalities (not very successfully) and the intense competition among the sound systems in the late 1920s. The opening third cuts together too many brief, unidentified film clips and talking-heads comments, which doesn’t make for a coherent introduction to the topic. The production of the Vitaphone shorts is not well explained, though the film does point out that the shorts were more influential than Don Juan in making the new process appeal to audiences. There are excerpts from the main early Warners sound films, as well as a section on actors who succeeded or failed in talkies.

Another item on this second disc is the entire surviving footage—two scenes—from Gold Diggers of Broadway, a two-strip Technicolor musical from 1929. It’s rather an arbitrary inclusion, but as it’s not likely to come out on DVD in any other context, we should be grateful to have it. The scenes are pretty dreadful, apart from the spectacularly cubistic melange of Parisian landmarks in the set.

Another item on this second disc is the entire surviving footage—two scenes—from Gold Diggers of Broadway, a two-strip Technicolor musical from 1929. It’s rather an arbitrary inclusion, but as it’s not likely to come out on DVD in any other context, we should be grateful to have it. The scenes are pretty dreadful, apart from the spectacularly cubistic melange of Parisian landmarks in the set.

The rest of the disc consists mainly of some older documentaries on early sound made by Warner Bros. One, The Voice from the Screen (1926) was intended as a demonstration of Vitaphone for technicians. The presenter is not, to say the least, charismatic, and it’s obvious why Discovering Cinema and A Century of Sound use only excerpts. Nice to have it complete, but students wouldn’t sit still for the whole thing. The Voice that Thrilled the World was directed by Jean Negulescu in 1943, on the occasion of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences adding a best-sound Oscar—the first of which happened to go to Warners’ Yankee Doodle Dandy. This short seems to be the source for the staged footage of early sound breakthroughs that show up, unidentified, in The Dawn of Sound and the other documentaries. Not surprisingly, The Voice that Thrilled the World primarily hypes the Vitaphone process.

“Okay for Sound” (1946) celebrated the twentieth anniversary of Don Juan’s premiere, and it recycles a lot of material from the 1943 short. Like The Voice that Thrilled the World, it was a theatrical short, intended as much to promote current Warners’ films as to celebrate the studio’s past triumphs. The film handily includes an extended clip of Jolson singing the saccharine “Sonny Boy” number in The Singing Fool (1928).

(A companion book with a slightly different title, “Okay for Sound!” was published in 1946. It’s a picture history of sound. The photos are not well produced, and many are just publicity stills from films. It does contain quite a few photos of sound equipment. It turns up with surprising frequency in used-book stores. The phrase, by the way, is what recordists would call out to indicate to directors when the sound was operating and the action could start–their equivalent of the camera operators’ “Speed!”)

When the Talkies Were Young (1955) is an odd, low-budget documentary that consists of fairly extended clips from some early Warners’ talkies: Sinners’ Holiday (1930), 20,000 Years in Sing Sing (1932), Night Nurse (1931), Five Star Final (1931), and Svengali (1931). These aren’t bad, though unfortunately the narrator occasionally interjects comments during the action.

The third disc contains over three and a half hours of restored Vitaphone shorts, a treasure trove for teachers who want to show some examples of these. The first one, Behind the Lines (1926), is the example we use in our box on “Early Sound Technology and the Classical Style” in Chapter 9 of Film History: An Introduction (see Figures 9.4 and 9.5, p. 197 in the second edition).

If I had to make a choice of just one of these three DVD releases in looking for clips for a unit on early sound, I would favor A Century of Sound as having the best organized presentation and the most useful set of excerpts. The “Learning to Talk” disc could be useful as a briefer, self-contained teaching tool. The Jazz Singer package is a bit of a hodgepodge, but educators who want to deal with early sound in depth could pluck out some very useful additional material from it.

A May 12, 1925 Case test with Gus Visser and his duck singing a duet of “Ma, He’s Making Eyes at Me.” (Added to the National Film Registry in 2002 and included in both Learning to Talk and A Century of Sound.)