Archive for the 'Silent film' Category

Cinema bolognese

Cinema Ritrovato, a festival of rediscovered and restored films, is now in its twenty-first year. We visited its two previous installments, and we found it one of the most hugely enjoyable festivals on the calendar. Where else can you see films from 1907, Richard Fleischer’s Violent Saturday (1955), and a tribute to Ben Gazzara in a single week? Then there are the nightly screenings on the Piazza Maggiore, which attract hundreds of locals. The city plays host magnificently, with plenty of fine restaurants and perpetually cheerful people.

Mounting hundreds of screenings and panels is an enormous effort, but Gianluca Farinelli, Guy Borlée, Peter von Bagh, and all their colleagues have made it look easy. (The word sprezzatura comes to mind.) Here are our impressions from the first half of the event.

The home base is the Cineteca di Bologna, the local film archive. It’s located in a wide, quiet courtyard. It houses a large library and meeting rooms, along with two cinemas. During the festival, the Lumiere 1 auditorium specializes in silent screenings with piano accompaniment, while Lumiere 2 presents sound films. Widescreen titles and big events are reserved for the Arlecchino, a big, comfortable commercial theatre built in the era of roadshows and CinemaScope.

Organizing such a mixed program is more difficult in certain ways than presenting an event involving contemporary films, which are moving through the festival circuit already. Ritrovato must find good prints of titles that fit the year’s themes and also coordinate the ongoing efforts of archives that are restoring films.

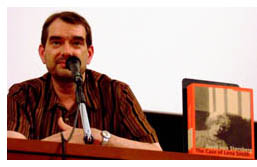

A good example is a remarkable project overseen by Alexander Horwath of the Austrian Film Museum. One of the most famous lost films in US history is Josef von Sternberg’s 1929 movie The Case of Lena Smith. In 2003, Japanese scholar Komatsu Hiroshi found a fragment, in very good condition, in China. On the basis of this, Horwath and his collaborators created a wonderful book that reconstructs the film. It includes a detailed shot breakdown (based on one published in Japan during the film’s release), along with gorgeous stills, script extracts, summaries of critical reception in various countries, and essays about the film’s place in history.

The fragment, previously screened at the Giornate del Cinema Muto last fall, was tantalizing. Lena and her friend Pepi are in the Prater, Vienna’s dazzling amusement park, and they are eyed by two young officers. The women watch some of the sideshow entertainments before darting away, the officers in pursuit. Several of the shots evoke the heady atmosphere of the park, with prismatic, superimposed images of the sideshow attractions and—typical von Sternberg—a spinning ride providing pulsating visions of the crowd.

In his panel presentation, Horwath stressed that the book couldn’t have been done without the cooperation of researchers around the world. The multilingual volume is to be made available in the UK and the US in 2008. It is a splendid example of what archives and scholars can accomplish working together, with festivals like Cinema Ritrovato providing a forum for rediscoveries. The book is available already at the archive’s website and will be distributed later this year by Wallflower in the UK and Columbia University Press in North America. (DB)

In his panel presentation, Horwath stressed that the book couldn’t have been done without the cooperation of researchers around the world. The multilingual volume is to be made available in the UK and the US in 2008. It is a splendid example of what archives and scholars can accomplish working together, with festivals like Cinema Ritrovato providing a forum for rediscoveries. The book is available already at the archive’s website and will be distributed later this year by Wallflower in the UK and Columbia University Press in North America. (DB)

One of the threads of this year’s festival is the early US career of Michael Curtiz. The Strange Love of Molly Louvain (1932) is an energetic Warners crook melodrama. Starring Ann Dvorak and the ever-annoying Lee Tracy, the film displays Curtiz’s characteristically staccato direction. The scenes with hard-bitten reporters use overlapping dialogue in a manner that prefigures His Girl Friday. Rarer was The Third Degree (1926), an early instance of Europe’s “International Style” infiltrating Hollywood. For his first Warners project, Curtiz fills an implausible mother-daughter melodrama with cloudy superimpositions, canted angles, florid tracking shots, oddball angles, extreme close-ups, and frantic montages played with prismatic lenses. Richard Koszarski gave an amusing and helpful introduction. (DB)

One attractive constant of the Ritrovato is a series of short films from 100 years ago. Thus when we first attended in 2005, there were groups of shorts from 1905. As we progress through the early years of the current century, we go in parallel through the early years of the previous one. Each day one or two small groups of 1907 films have been shown, grouped by country or genre. These included some familiar items, like the poignant Le Bagne des gosses (“Children’s Prison,” Pathé) and the amusing British chase film, That Fatal Sneeze (directed by Lewis Fitzhamon). I have run across references to early Westerns made in Europe but had not seen any from this early period. Les Apaches du Far-West (produced by Pathé) is as unauthentic as one might predict, with the cowboys riding on English-style saddles and the shoot-outs with the Apaches taking place in bucolic fields and woods that are clearly in France, not the West. (KT)

A major new initiative for international film preservation was announced in May at the Cannes Film Festival. The World Cinema Foundation was founded by Martin Scorsese, and its advisory board contains such major filmmakers as Abbas Kiarostami, Elia Suleiman, Walter Salles, and Wim Wenders. The goal is to restore films made in nations that lack the archival facilities to do so locally.

The Moroccan Transes (El Hal, 1981), directed by Ahmed El Maanouni, is the new foundation’s first restoration, and it was introduced by the director and by its producer, Izza Genini. The titles crediting Giorgio Armani, Cartier, and Qatar Airlines as sponsors raised some surprised laughter in the audience, but if Scorsese and his colleagues can draw funding from such sources into film restoration, all the better. Transes is partly a concert film and partly a history of a band that became popular in the 1970s by expressing young people’s frustrations and rebelliousness. The big concert that begins and ends the film is exhilarating in its depiction of the crowd’s enthusiasm—but chilling as well as soldiers patrol the audience and occasionally suppress the more demonstrative spectators. (KT)

Another major theme is the ever-popular star Asta Nielsen. Again, items familiar from other retrospectives are mixed with new discoveries. Karola Gramann has curated the series and plans to restore other Nielsen films, either new discoveries or better prints of familiar films. Zapatas Bande (1913-14), for example, existed before, but now a color print has been made based on tinting notations on an existing black-and-white copy. It’s a slight item, a casual tale of filmmakers getting into trouble while shooting an adventure movie, but it allows Nielsen to get away from her usual melodramas and display her range as a comic actor. (KT)

Another major theme is the ever-popular star Asta Nielsen. Again, items familiar from other retrospectives are mixed with new discoveries. Karola Gramann has curated the series and plans to restore other Nielsen films, either new discoveries or better prints of familiar films. Zapatas Bande (1913-14), for example, existed before, but now a color print has been made based on tinting notations on an existing black-and-white copy. It’s a slight item, a casual tale of filmmakers getting into trouble while shooting an adventure movie, but it allows Nielsen to get away from her usual melodramas and display her range as a comic actor. (KT)

Our first visit to Italy for a film festival was in 1986, when Le Gionate del Cinema Muto, in Pordenone, presented a vast retrospective of Scandinavian cinema from the pre-1919 era. One of the major revelations was that alongside Mauritz Stiller and Victor Sjöström, there was a third great Swedish director during the silent era, Georg af Klerker. The event also brought home to the audience one of the great tragedies of cinema history, the loss of many of Stiller’s and Sjöström’s films in an archive fire in the 1940s.

Every now and then, another film by one of these masters surfaces. This year the Ritrovato festival showed Madame de Thèbes, a 1915 Stiller film. As too often happens, the surviving copy, a French release print discovered by Lobster Films, was incomplete. The Svenska Filminstitutet has filled it out by inserting still shots created from copyright frames deposited at the Library of Congress and by replicating the original Swedish intertitles and letters. The result, full of sumptuous decor and extravagant plot twists, gives as good an approximation of the original as is now possible. It’s one more indication that the 1910s Swedish cinema was one of the glories of the silent era. (KT)

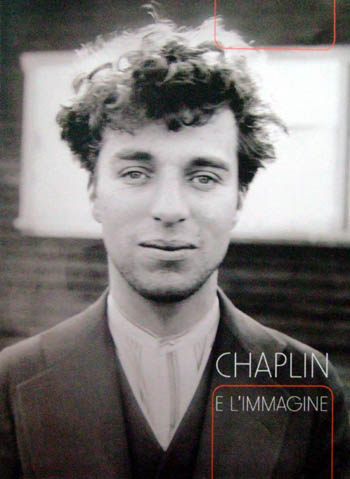

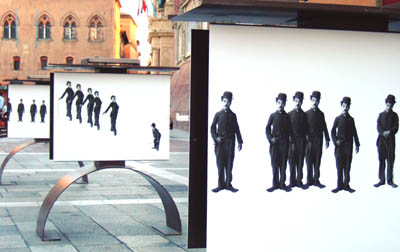

The festival has a close relation with the Charlie Chaplin estate; this is the place to come for the latest in Chaplin restorations and scholarship. Every year the festival mounts a tribute, including a superbly designed book on some aspect of Chaplin’s career. This year’s volume is a collection of rarely seen pictures, and its cover carries one of the most melancholy and haunting portraits of Charlie I’ve ever seen (up top).

The first big event of the festival was a screening in the city’s Teatro Communale, an overpowering opera house. It was a fitting venue for The Idle Class (1921) and The Kid (1921), accompanied by orchestra. The prints were pristine, shown in a nearly square ratio. The version of The Kid was based on Chaplin’s 1971 rerelease, since that represents his final thoughts, but the Bologna gang generously tacked on the material that Chaplin chopped out—all scenes with Edna Purviance, playing the unwed mother who abandons her baby. These scenes include her uneasy meeting her old lover years after she’s achieved success. The plot turn and the regretful tone seemed to me to look forward to A Woman of Paris. This version, along with the deleted scenes, is available on the MK2 DVD release.

The first big event of the festival was a screening in the city’s Teatro Communale, an overpowering opera house. It was a fitting venue for The Idle Class (1921) and The Kid (1921), accompanied by orchestra. The prints were pristine, shown in a nearly square ratio. The version of The Kid was based on Chaplin’s 1971 rerelease, since that represents his final thoughts, but the Bologna gang generously tacked on the material that Chaplin chopped out—all scenes with Edna Purviance, playing the unwed mother who abandons her baby. These scenes include her uneasy meeting her old lover years after she’s achieved success. The plot turn and the regretful tone seemed to me to look forward to A Woman of Paris. This version, along with the deleted scenes, is available on the MK2 DVD release.

The score was by Timothy Brock, who also conducted. On the following day Brock gave an enlightening seminar on how he based his scores on original themes that Chaplin came up with. Chaplin was in the habit of working and reworking tunes at the piano, and many of his efforts were recorded. The recordings came to light three years ago, and Brock was able to integrate the tunes into his scores—sometimes linking five or six in a single passage. (DB)

The score was by Timothy Brock, who also conducted. On the following day Brock gave an enlightening seminar on how he based his scores on original themes that Chaplin came up with. Chaplin was in the habit of working and reworking tunes at the piano, and many of his efforts were recorded. The recordings came to light three years ago, and Brock was able to integrate the tunes into his scores—sometimes linking five or six in a single passage. (DB)

A cloud was cast over our visit by the news of the death of Edward Yang (Yang Dechang). We admired his films and discussed them in Film History: An Introduction and my Figures Traced in Light. Edward was a likeable, tough-minded fellow. His films explored the effects of urbanization and politics on everyday life in Taiwan. He made his breakthrough to a broad international audience with Yi Yi (2000), but his other films, particularly Taipei Story (1985), The Terrorizers (1986), and A Brighter Summer Day (1991) are to me even more important. It’s a great loss that these aren’t easily available on DVD. When I get back to Madison and have access to pictures from my encounter with Edward in Kyoto in 1997, I hope to write a more adequate tribute. (DB)

1525 big thumbs up

Kristin here—

David and I just got back from Roger Ebert’s Overlooked Film Festival. It’s been held under the auspices of the University of Illinois, Roger’s alma mater, in late April for nine years now. This year the event was front-page news because our irrepressible host attended the event while recovering from surgery for salivary-gland cancer and complications last summer.

David and I just got back from Roger Ebert’s Overlooked Film Festival. It’s been held under the auspices of the University of Illinois, Roger’s alma mater, in late April for nine years now. This year the event was front-page news because our irrepressible host attended the event while recovering from surgery for salivary-gland cancer and complications last summer.

Roger’s features have changed somewhat and he faces further surgery and rehabilitation. Yet the man’s enthusiasm for movies and movie people has not waned. Most of the audience for Ebertfest (as it will officially be called starting next year) are regulars, and the standing ovations that greeted Roger and his wife Chaz show that the enthusiasm and affection are mutual. For more coverage, go here and here. For the official photoblog, with lots of neat pictures, go here.

If anything, Ebertfest audiences seemed even more cheerful and energetic than usual, happy that Roger has been so determined to avoid canceling this year’s event.

David and I have fond memories of Roger’s last visit to the Wisconsin Film Festival in 2006. There he introduced a restored print of Laura, held a signing at a local bookstore, and appeared at other screenings. People passing him on the street called out, “Hi, Roger,” as if he were an old friend. He graciously allowed me to interview him on the subject of press junkets for my chapter on marketing in The Frodo Franchise. There’s no way just to look up the history of junkets. No one has written one. But Roger is a primary document, having been attending them on and off since the 1960s. I learned a lot from our talk.

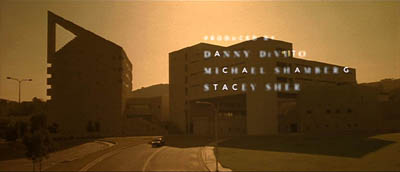

We drove down from Madison to Urbana-Champaign on Wednesday, David attending for the fourth year and I for the third. The opening film that evening was Gattaca (1997). With tepid reviews and box-office on its original release, Gattaca definitely counts as an overlooked film. Shown in an excellent print on the giant screen of the vintage Virginia movie palace, the cinematography was stunning and the story absorbing. Not an utter masterpiece, perhaps, but a very good film that deserved revival. As usual, people came from all over America to pack into the restored 1525-seat venue.

Now we’re back…and doing a summary blog. We had little time at the festival, and during our last day the web service at our lodgings conked out, so this stands as a fill-in.

Gattaca.

David’s two bits:

I saw ten films across three days and four nights.

The Virginia theatre did special justice to Gattaca. Writer-director Andrew Niccol used the anamorphic format imaginatively, a bit in the chilly manner of THX-1138, and the framings appeared to full effect on the 56-by-23-foot screen. This time I noticed how much the credit sequence, with only the G-A-T-C letters appearing first, owes to Godard. Like Alphaville, Gattaca uses not artificial sets but actual buildings to evoke the near future.

I thought that Moolade held up well on my second viewing, and the post-film discussion with the main performer Fatoumata Coulibaly (right) and Professor Samba Gadjigo was informative. The film’s call for an end to female genital mutilation is typical of Osmane Sembene’s use of controversial material; Professor Gadjigo recalled that Sembene calls his cinema a “night school” for Africa. Ms. Coulibaly said that in production “Papa Sembene” wouldn’t make eye contact with her, but before filming a painful sex scene he told her that she was “doing the scene for future generations.”

I thought that Moolade held up well on my second viewing, and the post-film discussion with the main performer Fatoumata Coulibaly (right) and Professor Samba Gadjigo was informative. The film’s call for an end to female genital mutilation is typical of Osmane Sembene’s use of controversial material; Professor Gadjigo recalled that Sembene calls his cinema a “night school” for Africa. Ms. Coulibaly said that in production “Papa Sembene” wouldn’t make eye contact with her, but before filming a painful sex scene he told her that she was “doing the scene for future generations.”

Sadie Thompson was still fine, I thought, with Walsh’s skill in cutting and staging exemplifying what Hollywood could do so easily in 1928. Swanson of course is tremendous in the role, using her whole body to tell the story of a woman who’s not as hard-edged as she makes out. The score by Joseph Turrin, conducted by Steve Larsen, was discreet and compelling.

La Dolce Vita seemed to me not to wear so well. I hadn’t seen it in at least twenty years, and its pacing and dramatic point-making appearing at once heavy and unfocused. Still, the film has that patented Fellini verve, and its daring fresco-like structure makes it a remarkable experiment in panoramic storytelling. It’s historically an enormously important film, and Jackie Reich illuminated it in our onstage discussion afterward. She has just published a book on Mastroianni’s career, Beyond the Latin Lover.

Of the items that were new to me:

The Weather Man took me by surprise, not only for its glum tone and antiheroic protagonist but also for its refusal of a tidy happy ending. Of Steve Conrad’s screenplay, Gil Bellows remarked that “one of the things that he can do is make you cringe for a character.” To his credit, Gore Verbinski, of Pirates of the Caribbean fame, found this uneasy domestic drama/ comedy a congenial project.

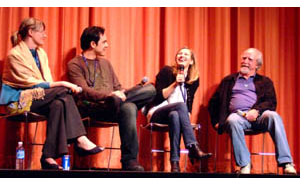

Come Early Morning by Joey Lauren Adams was a clear-eyed character study of an intelligent, flawed woman. Lacking villains and almost lacking heroes, it captures the rhythms of life in a small Arkansas town. Our protagonist, quietly efficient in her job, is caught in family and romance problems as she moves from man to man in a beery stupor. It was tactfully directed by Adams and graced by the underappreciated Ashley Judd. The Weather Man concludes with our hero facing us in close-up, but Come Early Morning ends with the protagonist turned away; in each case, the image feels right. On the left, Lisa Rosman, Eric Byler (Charlotte Sometimes), Joey Lauren Adams, and Scott Wilson (who plays the protagonist’s father).

Come Early Morning by Joey Lauren Adams was a clear-eyed character study of an intelligent, flawed woman. Lacking villains and almost lacking heroes, it captures the rhythms of life in a small Arkansas town. Our protagonist, quietly efficient in her job, is caught in family and romance problems as she moves from man to man in a beery stupor. It was tactfully directed by Adams and graced by the underappreciated Ashley Judd. The Weather Man concludes with our hero facing us in close-up, but Come Early Morning ends with the protagonist turned away; in each case, the image feels right. On the left, Lisa Rosman, Eric Byler (Charlotte Sometimes), Joey Lauren Adams, and Scott Wilson (who plays the protagonist’s father).

I must be the last person in North America to see Holes. Its tight plot, clever humor, and easygoing handling of racial matters endeared it to me. As in old Disney fare, familiar actors (Jon Voigt, Sigourney Weaver, Robin Wright Penn, Tim Blake Nelson) are willing to ham it up for the kids, with enjoyable results. And I was startled by the intricate flashback structure on offer; are kids now being trained to follow movies like 21 Grams? Given the interracial love story at the movie’s center, I had a new angle on what Walden Media might be contributing to modern Hollywood, something valuable that escapes cliches about “family-friendly” and “faith-based” entertainment.

Man of Flowers was a crowd-pleaser. I admired Paul Cox’s visuals, though the grainy print probably didn’t do justice to the range of dark tones in the original. An exercise in portraying a wealthy man’s obsessions and their sources in childhood, it moved toward Buñuel’s Archibaldo del Cruz, but it wasn’t prepared to be as lurid or delirious. A bit too dry and tasteful, perhaps. Still, I admire patient, unshowy long takes, and Man of Flowers is full of them. The photo above shows Paul reading a heartfelt tribute to Roger.

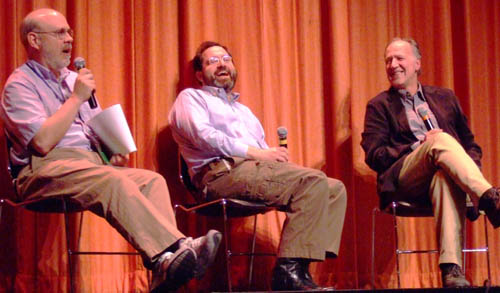

Perfume: The Story of a Murderer was much liked by the audience, and the presence of Alan Rickman made it all the more pungent. I wanted to like it more than I did. Despite my admiration for Tom Tykwer’s other films, particularly Winter Sleepers, The Princess and the Warrior, and Heaven, this one struck me as an overproduced Euro effort at a Big Movie. I thought it overdid the camera tricks (slow-mo, ramping) and the insistence on stuffing every shot with details (e.g., fish, cobwebbed glassware, glistening golden liquids). Above, you see the great actor with Festival Director Nate Kohn and entertainment analyst David Poland.

The simple and modest Stroszek was, for me, better at evoking smells—for instance, the stale smoke of the Himmel bar that our hero frequents. The print was faded and weatherbeaten, but the mysterious simplicity of this modern classic came through. The Wisconsin scenes, shot in Plainfield thirty years ago, wouldn’t need much changing today. As usual, I enjoyed the porous, unpredictable plot and Herzog’s willingness to dwell on unfathomable moments like a premature baby with powerful fingers (sleeping, he looks like a wrinkled alien) and the warped imagery of people passing a prison, seen through a hanging water bottle. The dancing chicken became one of the top screen icons of the 1970s.

Now for some quotes I like.

*Gattaca producer Michael Shamberg: “In the pilot scenes of Top Gun, Tom Cruise doesn’t wear his oxygen mask.” Ebertfest blogger Lisa Rosman: “It’s Scientology.”

*“None of the people I write about have friends.” Steven Conrad, screenwriter.

*“The US and Europe are my market. Africa is my public.” Osmane Sembene, quoted by Samba Gadjigo.

*Werner Herzog gave Roger Ebert an early alert about the importance of Anna Nicole Smith in American culture: “The poet must not avert his eyes.”

*“When I pray, I pray to Jesus.” Joey Lauren Adams.

*“Ambiguity in everyday life isn’t exactly celebrated in most movies. . . . It’s great when a big movie celebrates unnameable things.” Alan Rickman on Perfume.

*“Alan, be more subtle—do more.” Ang Lee to Alan Rickman, directing Sense and Sensibility.

*Why did Michael Wiese move to Penzance? “I was in a Witness Protec—oops.”

*“I’ve learned more about directing by working with bad directors than with good ones. And I’ve worked with a lot of bad directors.” Joey Lauren Adams.

*“Sometimes I think I’d like to join another species. . . . They seem to live a more sensible life.” Paul Cox.

*“Our technological civilization is not sustainable on this planet. Nature is going to regulate us very quickly. . . .We’ll be the next ones [to go extinct]. But that’s okay. Let’s enjoy movies and friendship and beer.” Werner Herzog.

*“I saw perhaps three or four films last year. I love cinema, but I’m not a cinephile.” Werner Herzog.

And some portraits of Ebertfest regulars:

First: Michael Wiese, filmmaker (Hardware Wars, The Sacred Sites of the Dalai Lamas) and publisher of outstanding books on the art and craft of film. Next, actor Scott Wilson (In Cold Blood, Junebug, The Host, and many more). Finally, Jim Emerson, who runs Roger’s website and writes fine film criticism at Scanners.

Each year, several guests receive an Ebert Thumb. This year, Kristin was one of the lucky ones.

Finally, here I am with Michael Barker, co-president of Sony Pictures Classics, and Werner Herzog. All I said was that I was from Wisconsin….

I plan to blog again soon about Roger and his contributions to filmmaking and film culture. For now, let me just echo Kristin’s opening point that his passion for film is exceeded only by his enjoyment of other people. This weekend’s gathering of top-rank filmmakers, young and old, and the enthusiastic audiences showed that he is probably the most deeply loved film critic whom we have ever had.

Homage to Mme. Edelhaus

Why are Americans polarized between francophobia and francophilia? Some people mock the French for liking Jerry Lewis, when most French people probably don’t even know who he is. Others think that France is the repository of world culture and represents the finest in writing about the arts, even though the Parisian intelligentsia can be pretentious and hermetic.

But we must face facts. When it comes to cinephilia, the French have no equals. They grant film a respect that it wins nowhere else. Spend a year, or even a month, in Paris, and you will feel like a Renaissance prince. This is a city where one lonely screen can run tattered prints of One from the Heart and Hellzapoppin!, once a week, indefinitely.

My first trip was too brief, only a week in 1970, but my second one—four weeks of dissertation research in 1973—left me exhausted. Reading Pariscope on the way in from the airport, I learned about a Tex Avery festival. I checked into my hotel and Métro’d to the theatre, where I and a bunch of moms and kids gazed in rapture upon King-Size Canary. Another time, also coming in from the airport, Kristin and I passed a marquee for King Hu’s Raining in the Mountain. Next stop, Raining in the Mountain. My memories of The Naked Spur, Ministry of Fear, Liebelei, Tati’s Traffic, and Vertov’s Stride Soviet! are inextricable from the Parisian venues in which I saw them.

Sound like a lament for days gone by? Nope. You can find the same variety on offer today. Of course the two monthlies, Cahiers du cinéma and Positif, have to take a lot of credit for this. Add Traffic, Cinéma, and several other ambitious journals, and you get a film culture unrivalled in the world.

Critics from Louis Delluc onward have led thousands of readers toward appreciating the seventh art. Historians like Georges Sadoul, Jean Mitry, Laurent Mannoni, Francis Lacassin, and others have enlightened us for decades. Academic film analysis would not be what it is without Raymond Bellour, Noel Burch, Marie-Claire Ropars, Jacques Aumont, and a host of other scholars. Above all stands André Bazin, the greatest theorist-critic we have had.

And the books! Arts-and-sciences publishing receives government subsidies; the French understand that books contribute to the public good. There are plenty of worse ways to spend tax dollars (e.g., trumped-up military invasions). The French, like the Italians, have created an ardent translation culture too. If you can’t read something in Russian or German, there’s a good chance it’s available in French.

I was reminded of the glories of Gallic film publishing when the mailman tottered to my door this week with twenty-two pounds worth of recent items I’d ordered. I haven’t even read them yet; otherwise, they’d be filed with Book Reports. Instead I want to spend today’s blog celebrating them as fruits of an ambition that has no counterpart in English-language publishing. All are grand and gorgeous and informative to boot.

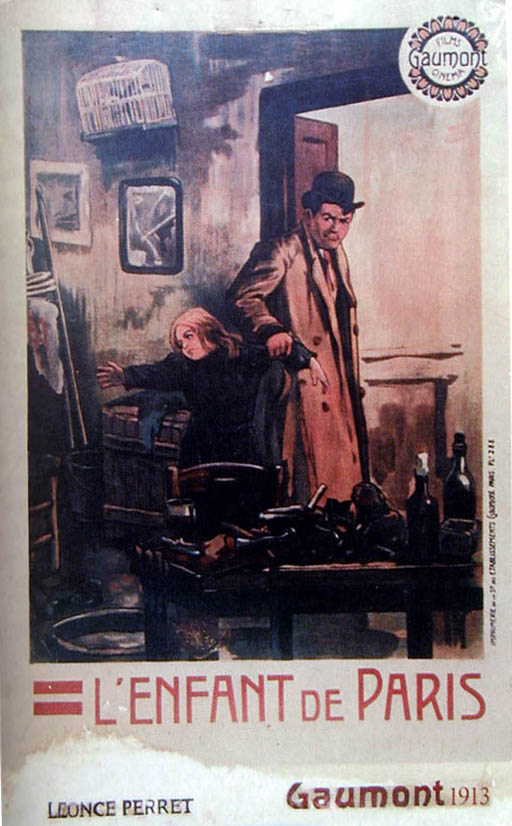

Daniel Taillé, Léonce Perret Cinématographiste. Association Cinémathèque en Deux-Sèvres, 2006. 2.5 lbs.

Daniel Taillé, Léonce Perret Cinématographiste. Association Cinémathèque en Deux-Sèvres, 2006. 2.5 lbs.

A biographical study of a Gaumont director still too little known. Perret was second only to Feuillade at Gaumont, and he performed as a fine comedian as well. His shorts are charming, and his longer works, like L’enfant de Paris (1913), remain remarkable for their complex staging and cutting. After a thriving career in France, Perret came to make films in America, including Twin Pawns (1919), a lively Wilkie Collins adaptation. He returned to France and was directing up to his death in 1935.

Although the text seems a bit cut-and-paste, Taillé has included many lovely posters and letters, along with a detailed filmography, full endnotes, and a vast bibliography. It compares only to that deluxe career survey of the silent films of Raoul Walsh, published by Knopf. . . .Oh, wait, there’s no such book. . . .Think there ever will be?

Il était une fois Walt Disney: Aux sources de l’art des studios Disney. Galéries nationales du Grand Palais, 2006. 4 lbs.

Il était une fois Walt Disney: Aux sources de l’art des studios Disney. Galéries nationales du Grand Palais, 2006. 4 lbs.

A luscious catalogue of an exposition tracing visual sources of Disney’s animation. Illustrated with sketches, concept paintings, and character designs from the Disney archives, this volume shows how much the cartoon studio owed to painting traditions from the Middle Ages onward. It includes articles on the training schools that shaped the studio’s look, on European sources of Disney’s style and iconography, on architecture, on relations with Dalí, and on appropriations by Pop Artists. There’s also a filmography and a valuable biographical dictionary of studio animators.

Some of the affinities seem far-fetched, but after Neil Gabler’s unadventurous biography, a little stretching is welcome. This exhibition (headed to Montreal next month) answers my hopes for serious treatment of the pictorial ambitions of the world’s most powerful cartoon factory. The catalogue is about to appear in English–from a German publisher.

Jean-Pierre Berthomé and François Thomas. Orson Welles au travail. Cahiers du cinéma, 2006. 4 lbs.

Jean-Pierre Berthomé and François Thomas. Orson Welles au travail. Cahiers du cinéma, 2006. 4 lbs.

The authors of a lengthy study of Citizen Kane now take us through the production process of each of Welles’ works. They have stuffed their book with script excerpts, storyboards, charts, timelines, and uncommon production stills.

The text, on my cursory sampling, will seem largely familiar to Welles aficionados; the frames from the actual films betray their DVD origins; and I would like to have seen more depth on certain stylistic matters. (The authors’ account of the pre-Kane Hollywood style, for instance, is oversimplified.) Yet the sheer luxury of the presentation overwhelms my reservations. A colossal filmmaker, in several senses, deserves a colossal book like this.

Alain Bergala. Godard au travail: Les années 60. Cahiers du cinéma. 2006. 5 lbs.

Alain Bergala. Godard au travail: Les années 60. Cahiers du cinéma. 2006. 5 lbs.

In the same series as the Welles volume, even more imposing. If you want to know the shooting schedule for Alphaville or check the retake report for La Chinoise (these are eminently reasonable desires), here is the place to look. Detailed background on the production of every 1960s Godard movie, with many discussions of the creative choices at each stage. Once more, stunningly mounted, with lots of color to show off posters and production stills.

Anybody who thinks that Godard just made it up as he went along will be surprised to find a great degree of detailed planning. (After all, the guy is Swiss.) Yet the scripts leave plenty of room to wiggle. “The first shot of this sequence,” begins one scene of the Contempt screenplay, “is also the last shot of the previous sequence.” Soon we learn that “This sequence will last around 20-30 minutes. It’s difficult to recount what happens exactly and chronologically.”

Emrik Gouneau and Léonard Amara. Encyclopédie du cinéma du Hong Kong. Les Belles Lettres, 2006. 6.5 lbs.

Emrik Gouneau and Léonard Amara. Encyclopédie du cinéma du Hong Kong. Les Belles Lettres, 2006. 6.5 lbs.

The avoirdupois champ of my batch. The French were early admirers of modern Hong Kong cinema, but their reference works lagged behind those of Italy, Germany, and the US. (Most notable of the last is John Charles’ Hong Kong Filmography, 1977-1997.) More recently the French have weighed in, literally. 2005 gave us Christophe Genet’s Encyclopédie du cinéma d’arts martiaux, a substantial (2 lbs.) list of films and personalities, with plots, credits, and French release dates.

Newer and niftier, the Gouneau/ Amara volume covers much more than martial arts, and so it strikes my tabletop like a Shaolin monk’s fist. There are lovely posters in color and plenty of photos of actors that help you identify recurring bit players. Yet this is more than a pretty coffee-table book. It offers genre analysis, history, critical commentary, biographical entries, surveys of music, comments on television production, and much more. It has abbreviated lists of terms and top box-office titles, as well as a surprisingly detailed chronology.

Above all—and worth the 62-euro price tag in itself—the volume provides a chronological list of all domestically made films released in the colony from 1913 to 2006! Running to over 200 big-format pages, the list enters films by their English titles and it indicates language (Mandarin, Cantonese, or other), release date, director, genre, and major stars. Until the Hong Kong Film Archive completes its vast filmography of local productions, this will remain indispensable for all researchers.

Above all—and worth the 62-euro price tag in itself—the volume provides a chronological list of all domestically made films released in the colony from 1913 to 2006! Running to over 200 big-format pages, the list enters films by their English titles and it indicates language (Mandarin, Cantonese, or other), release date, director, genre, and major stars. Until the Hong Kong Film Archive completes its vast filmography of local productions, this will remain indispensable for all researchers.

Mme. Edelhaus was my high school French teacher. A stout lady always in a black dress, she looked like the dowager at the piano during the danse macabre of Rules of the Game. She was mysterious. She occasionally let slip what it was like to live under Nazi occupation, telling us how German soldiers seeded parks and playgrounds with explosives before they left Paris. When I asked her what avant-garde meant, she replied that it was the artistic force that led into unknown regions and invited others to follow–pause–“in the unlikely event that they will choose to do so.”

For three years Mme. Edelhaus suffered my execrable pronunciation. When I tried to make light of my bungling, she would ask, “Dah-veed, why must you always play the fool?”

I suppose I’m still at it. But thanks largely to her I’m able to read these books as well as look at them. She opened a path that’s still providing me vistas onto the splendors of cinema.

From Hollywood to Atlanta to us

DB here:

Some day Ph. D. students will be writing dissertations on the contribution of Turner Classic Movies to US culture. I’d argue that Ted’s baby is as important to our collective sense of cinema history as the establishment of the Museum of Modern Art Film Department was.

As a movie fan, I’m overwhelmed by the chance to see so many of my favorites for the cost of monthly cable. As a film researcher, I find myself feeling as if a film archive dumped a dozen movies on my front lawn every morning. In 1990, my colleagues and I would’ve killed for the opportunity to see this stuff, and now it’s whizzed to us at home. “Seven Brides for Seven Brothers again?” some of us sigh. We are so spoiled.

To refresh his core MGM-RKO-WB titles, Turner showcases items from Columbia, Paramount, Goldwyn, and other studios. The channel has become an eternal college course in cinema, with no exams or papers and all viewers happy to earn a perpetual Incomplete.

To refresh his core MGM-RKO-WB titles, Turner showcases items from Columbia, Paramount, Goldwyn, and other studios. The channel has become an eternal college course in cinema, with no exams or papers and all viewers happy to earn a perpetual Incomplete.

Why mention TCM now? Because I’m especially wrought up by what’s on offer over the waning days of January. Every day boasts many classics, so I’ll mostly skip mentioning all the fine standbys that they’re running. Here are more offbeat things I’m up for, most of which I haven’t seen.

Overturning centuries of Western tradition, TCM defines a new day as starting at 6:00 AM. Sounds reasonable to me. But check for local playing times.

Jan 21: Stolen Moments (1920): I don’t get Rudolph Valentino’s appeal, but any film from this era demands a look.

Munchhausen (1943) A textbook classic from the Nazi cinema.

Jan. 22: The Legend of Lylah Clare (1968): Trashy premise + Kim Novak + Robert Aldrich = must-see.

Jan. 23: A cornucopia. I’ll just keep the recorder going all day for:

The Black Book (1949): As oddball a film as Anthony Mann ever made, with John Alton’s pitch-black scenes turning the French Revolution into a noir nightmare. Forget the commercial DVD, evidently ripped from a 16mm print; the TCM version should look better.

Gangster Story (1959): Walter Matthau starred and directed this NYC low-budgeter.

The Guilty Generation (1931): From Rowland V. Lee, endless supplier of B’s.

The Criminal Code (1931): Excellent Hawks with Karloff. Bogdanovich paid tribute to this in Targets.

A string of Boston Blackie films, from 1941-1942: I remember this popular B series from TV syndication in my childhood. Fast-paced and punchy, with direction by Robert Florey, Edward Dmytryk, Michael Gordon, and the prolific Lew Landers.

Angels over Broadway (1940; on right): Mostly shot in one nightclub set (in the Astoria studio?), a murky drama signed by Ben Hecht and Lee Garmes. Douglas Fairbanks Jr., Thomas Mitchell, and a young Rita Hayworth fill out sober long takes.

Angels over Broadway (1940; on right): Mostly shot in one nightclub set (in the Astoria studio?), a murky drama signed by Ben Hecht and Lee Garmes. Douglas Fairbanks Jr., Thomas Mitchell, and a young Rita Hayworth fill out sober long takes.

The King Steps Out (1936): Hard-to-see von Sternberg.

Jan. 24: Of course you’ll watch La Strada, Detective Story, The Big Carnival, etc. if you haven’t seen them. Me, I’m poised to record Merry Andrew (1958), a CinemaScope vehicle featuring Danny Kaye as an Oxbridge archaeologist. The film contains another unexorcizable ghost from my childhood, the song “Everything is Tickety-Boo.” What’s tickety-boo? Canadians know.

Jan. 25: Lots of prime stuff, including Experiment in Terror, Anatomy of a Murder, Dead Heat on a Merry-Go-Round, The Caddy, and several classic MGM musicals.

Jan. 26: A day devoted mostly Paul Newman and Paris, but there’s also:

The Killer Is Loose (1956): Boetticher. Say no more.

To Paris with Love (1955): Robert Hamer, director of the Ealing classic Kind Hearts and Coronets, gave us this, starring Alec Guinness, one of cinema’s finest and most modest actors.

A drive-in horror double bill courtesy William Beaudine: Billy the Kid vs. Dracula (1966) and Jesse James Meets Frankenstein’s Daughter (1966).

Jan. 27: Of course you’ll see, if you haven’t, Gunga Din, The Yearling, The Naked Spur, The Manchurian Candidate (kinda overrated, methinks), The Spy Who Came in from the Cold (kinda underrated), The Quiet American, etc. But there’s also:

The Last of the Mohicans (1935): This, rather close to Michael Mann’s later version, I remember as being pretty solid.

A Bullet for Joey (1955): Edward G and George Raft in their sunset years; can it be bad? Okay, it can, but I’m still going to check it out.

Jan. 28: Among much good stuff, including the still poignant Umbrellas of Cherbourg, I’ll be targeting Dragnet (1954), a nifty, seldom seen feature by that unique genius Jack Webb. How often do we get an ashtray’s-eye-view of a scene? Does this cablecast portend a DVD release?

Jan. 28: Among much good stuff, including the still poignant Umbrellas of Cherbourg, I’ll be targeting Dragnet (1954), a nifty, seldom seen feature by that unique genius Jack Webb. How often do we get an ashtray’s-eye-view of a scene? Does this cablecast portend a DVD release?

Jan. 29: It’s teen dance music till prime time: Bop Girl, Rock around the Clock, Don’t Knock the Rock, Don’t Knock the Twist, Don’t Rock the Twist, Don’t Twist My Rock, etc. Might just as well keep the recorder rolling… and rocking!

Today’s outstanding piece of esoterica is The Show (1927). Every year or so I’ve been writing TCM to ask them to play this strange item from the agreeably warped Tod Browning. Let’s just say that John Gilbert plays Cock Robin and Renee Adoree plays Salome, with Lionel Barrymore chewing the scenery as the villain. Other attractions include cuckoldry, decapitation, and murderous iguanas. With a new score from TCM’s highly laudable Young Composers competition.

Jan. 30: Of course you’ve seen Ford’s stunning Arrowsmith, Pressburger’s Life and Death of Colonel Blimp, This Happy Breed, Shane, His Girl Friday, etc. But don’t forget:

The Clairvoyant (1935): the relentlessly prolific Maurice Elvey, doyen of Brit good taste, directs Claude Rains (ditto) and Fay Wray.

Strike Me Pink (1936): Eddie Cantor isn’t for all tastes, but I want to give this one a chance.

Raffles (1939): I’m a sucker for gentleman-thief stories, and with Gregg Toland as cinematographer, Sam Wood may indulge his Gothic streak, so memorable in Our Town and Kings Row.

Jan. 31: Not as strong a day as yesterday, but I’ll be checking on This Could Be the Night (1957), helmed, as they say, by Robert Wise and starring the radiant Jean Simmons (another adolescent fascination of mine), and Mitchell Liesen’s The Mating Season (1950), written by Charles Brackett and starring the fascinatingly blank Gene Tierney.

February, devoted to Oscar pictures, doesn’t contain so many marginal items, but still it’s a cornucopia of outstanding movies.

Controversial as he is, Ted Turner has proven a generous mogul, both politically and cinematically. Forget colorization! That was a bogus issue, and anyhow, for every colorized title a spanking fine-grain positive was made for archival preservation. Turner has done more than any single person to sustain and publicize the American film heritage, and he’s made it available to everyone within reach of cable. You can read more about Ted in Ken Auletta’s brisk and chatty biography.

Dorothy’s rainbow comes to earth at TCM. Watch regularly. Check the website for extra stuff, and browse the 150,000 film database. Buy the monthly program guide; it’s only twelve bucks. While you soak up the pleasure, pause to pity the cinephiles overseas. Their version of TCM, hedged by rights holder restrictions, offers mere crumbs from our bursting banquet table.

PS: Since I first posted this, film historian Doug Gomery has pointed out that Turner hasn’t controlled TCM in 12 years, but both Time-Warner bosses Gerry Levin and Dick Parsons have kept it going. We owe them thanks for refusing to ‘AMC’ it with commercial breaks and dopey gimmicks. Fortunately it makes money for TW. Long may TCM prosper.

PPS as of 23 Jan.: Lee Tsiantis of the Turner Entertainment Group adds that credit also belongs to Jeff Bewkes, who among other duties oversees the channel. So a big thanks to him as well.