Archive for the 'Silent film' Category

Bill Morrison’s lyrical tale of loss, destruction, and (sometimes) recovery

Kristin here:

Many readers of this blog have heard of the Dawson City Film Find (hereafter DCFF), as it is called in Bill Morrison’s extraordinary documentary, Dawson City: Frozen Time. How in 1978 work on a construction site in Dawson City, Canada, led to the discovery of hundreds of reels of nitrate films packed into a swimming pool in 1929, covered over, and forgotten. How these reels turned out to be from silent films, mostly from the 1910s, many of them previously thought entirely lost.

Few will know the story in the detail with Morrison provides, nor will they know the rich historical context that he provides for the discovery and recovery of the reels. His film is not, however, simply a presentation of the DCFF. It’s about growth, loss, recovery, and destruction in several areas, all circling around Dawson City as their hub. The subtitle “Frozen Time” is a bit misleading. The reels of nitrate sealed away in the permafrost were no doubt frozen, and the temporal fictional and newsreel images they contained were lost for decades.

Morrison, however, weaves information about a variety of other subjects together in a way that makes the passage of time palpable for us. We see its effects on people and places and discover the odd, fortuitous connections among them in a dizzying fashion.

A complex film like this deserves an extended commentary, which I offer below. There are spoilers galore in it, and I would suggest seeing the film before reading this. It should appeal to anyone interested in early cinema, in North American history, and in documentaries in general. Kino Lorber has recently released Dawson City: Frozen Time on Blu-ray, with extras including eight films from the DCFF.

Easing into the past

The films-in-a-swimming-pool hook is what Morrison uses to lure us into his larger historical weave. He begins with a hint of the recovered footage, showing a baseball game which will later be revealed as the scandalous 1919 World Series where White Sox players were bribed to throw the deciding game. Then we see briefly see Morrison himself being interviewed by a talk-show host, followed by a lady in 1890s costume enthusiastically introducing a premiere screening of some of the restored films for an audience in the Palace Grand. That theatere is a modern reconstruction of the first theater built in Dawson City, used for live drama, opera, eventually films, and other forms of entertainment.

We move by stages back into history. Fifteen months before the premiere the discovery was made: a man running a back hoe turned up reels and coils of film. We meet the protagonists of the film-discovery portion of Morrison’s tale: Michael Gates, curator of Collections at Parks Canada from 1977 to 1996, and Kathy Jones-Gates, Director of the Dawson Museum from 1974 to 1986. She was Kathy Jones at the time of the discovery; this tale even has a romance, since the pair married after working together on the recovery of the buried reels. The couple describe the initial find, over still photos of mud-covered reels taken with Jones’s camera (above).

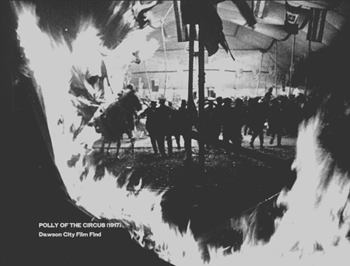

Morrison now takes us further back, to demonstrations of how nitrate film was made (with extracts from a 1937 film optimistically titled Romance of Celluloid) and how it is prone to catch fire and burn fiercely. The well-known 1897 Charity Bazaar disaster in Paris is cited, while film of a burning tent and fleeing spectators is shown. No visual record survives of the Charity Bazaar disaster, not even photographs. News accounts used engravings as illustrations. The burning tent footage is from a film released twenty years later, Polly of the Circus (1917), one of the main lost films recovered in the DCFF.

Morrison does not hide this source but superimposes a caption giving the film’s title, date, and source. This is the first time he draws upon DCFF images to evocatively represent real historical events. Later in Dawson City, the mention of an actual person, such as Gates, sending a letter will be accompanied by a montage of letter-reading moments culled from DCFF films. It’s a clever way to add a little humor and to show off a wide variety of the titles without dwelling on long clips from any one film.

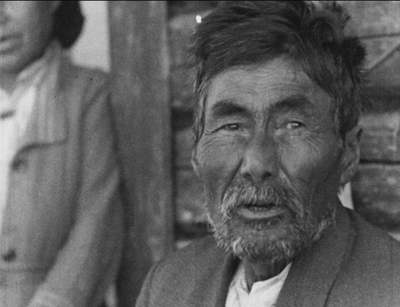

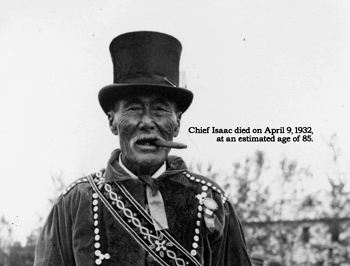

Having established the destructibility and danger of nitrate, Morrison flashes back to the earliest period portrayed in the film. Epic photographs show forested landscape. The narration, done with captions rather than voiceover, informs us that for millennia the area where the Klondike River flows into the Yukon has been the hunting grounds for one of the First Nations, the “native Hän-speaking people.” (The footage is from City of Gold, the famous 1957 Canadian documentary about Dawson City, which will become more important later in Morrison’s film.) A photo introduces Chief Isaac, leader of one subgroup of the Hän.

Nothing is said at this point, but the fate of these hunting grounds initiates one of the major threads recurring through the film, that of ecological destruction.

The third major thread is the history of Dawson City itself, which is as fascinating as the story of the buried films. In late 1896 or early 1897 one Joseph Ladue claimed 160 acres as a town site, where he sold lumber and lots to prospectors. By the summer of 1897 there were 3500 residents, and Morrison uses population figures to trace the wide swings in the town’s fortunes over the decades.

At this point the Northwest Mounted Police relocated the Häns’ village five miles downriver, and their fishing and hunting grounds were destroyed by mining.

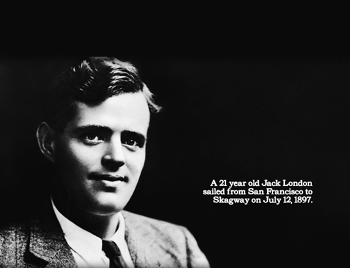

During the descriptions and facts about the huge amounts of gold coming out of the area, Morrison introduces other motifs and threads. He mentions that Jack London was among the prospectors. He was the first of several writers and theater figures who were in the Yukon, often during these early years. Most of them resurface late in the film later on, turning out to have surprising connections with the history of the cinema and each other.

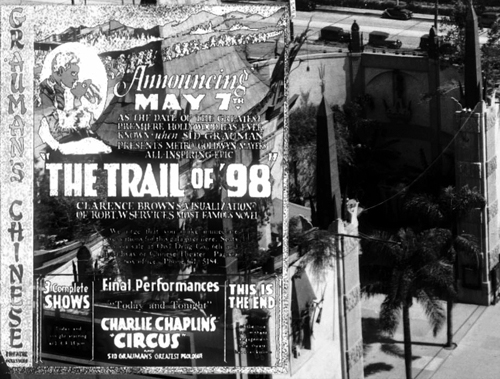

Famous entrepreneurs of later years got their starts here. Sid Grauman was a newspaper boy who eventually went on to build a theater chain, including the Egyptian and Grauman’s Chinese in Los Angeles. Ted Richard, who staged boxing matches in the Monte Carlo theater, later founded the New York Rangers and rebuilt Madison Square Garden. Alex Pantages started as a bartender, rebuilt Dawson City’s Orpheum theater after it burned to the ground in 1899 and showed traveling programs of early movies. He became one of the first major film tycoons, building a string of 70 theaters in North America.

The Gold Rush frozen in time

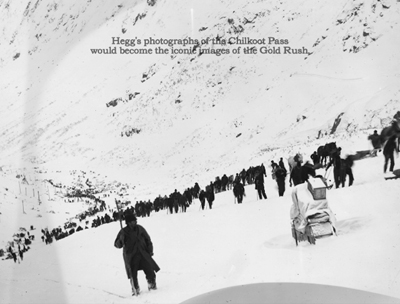

One of the revelations of Dawson City is the work of photographer Eric Hegg, who traveled to the Yukon alongside with the hordes of hopeful prospectors. He, however, worked as a photographer, and shot thousands of images that became, as Morrison’s caption says, “the iconic images of the Gold Rush.” The one above shows the arduous and crowded journey up over the notorious Chilkoot Pass. Chaplin later staged a remarkably similar scene for The Gold Rush (1925), though whether he could have seen Hegg’s images is unclear.

By the summer of 1898, the population of Dawson City was around 40,000, and the richest claims were all taken. Businesses were set up to cater to the prospectors, including Hegg’s photographic studio. Saloons, casinos, theaters, as well as more practical boat-builders and banks sprang up. Of the two initial banks that opened branches, the Canadian Bank of Commerce is the more important to Morrison’s story, since it eventually acted as the Dawson City agent for distributors sending films to town.

The first boom ended in the spring of 1900, after the announcement of a gold strike in Nome. Three-quarters of Dawson City’s population left, including Hegg, who left his collection of glass negatives with his partner, Ed Larss. He opened a new studio in Skagway and continued to document the Gold Rush.

After his departure, Hegg disappears from Dawson City for quite some time. His work there, however, was also fortuitously rescued from oblivion. Twenty minutes from the end, we are introduced to Irene Caley and Will Crayford, who married in 1947 and decided to move a cabin from Dawson City to Rock Creek. Inside the walls they found hundreds of Hegg’s glass negatives. How they got there is unknown. Coincidentally, Hegg died in 1947, presumably unaware of the recovery of his early negatives.

The newlyweds proposed to strip the emulsion off the plates and use them to build a greenhouse. Luckily a local shopkeeper recognized their nature and gave the couple plain plates in exchange for the 93 glass ones, as well as 96 nitrate negatives. He donated the collection to the National Museum of Man in Ottawa. Arguably this rescue is as significant as the DCFF, especially given that Hegg’s photographs mostly survived in beautiful condition and constitute the best record of the Gold Rush’s first stage.

In 1949 a book of Hegg’s photographs, edited by Edith Anderson Bccker, was published as Klondike ’98.

Subsequently documentary film director and producer Colin Low saw the plates in Ottawa and was inspired to make City of Gold (1957), co-directed by Wolf Koenig. City of Gold, which drew extensively on Hegg’s images, was nominated for an Oscar for Best Short Film. The awards ceremony took place at the Pantages Theater in Los Angeles, built and owned by the same Alexander Pantages who launched his theatrical career in Dawson City. It would be nice to think that whoever attended that ceremony representing City of Gold saw the connection.

In 1900, Hegg moved to Skagway and continued to document the Gold Rush. His post-Dawson City photographs also survive. The University of Washington’s collection contains over 2100. Its library offers a short biography and a generous sampling of those photographs here.

Weaving the threads together

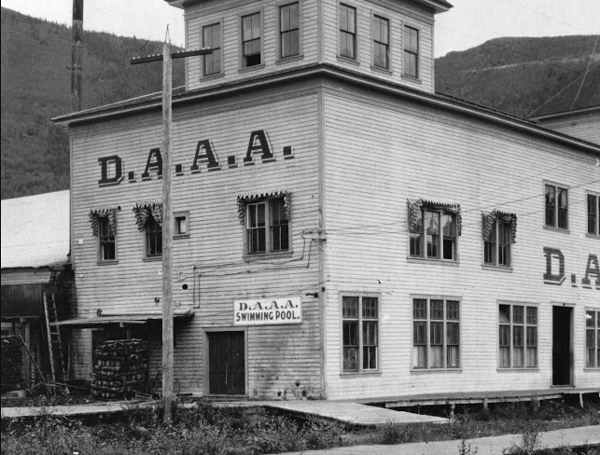

Dawson City’s second boom was less spectacular but more ominous. The White Pass Railroad made Dawson City more accessible, and heavier equipment was brought in: giant hoses to break up the ground, sluices to convey the ore to a central locale, and so. Miners brought their families to live in Dawson City, with the population steadying at 9000. Various institutions, including banks, the Carnegie Library (above), and, in 1902, the huge Dawson Amateur Athletic Assocation (DAAA) building was built, with an auditorium, billiards room, bowling alley, skating rink, and swimming pool (top). I can’t summarize the whole film, but by this point Morrison has introduced enough people and places to start connecting them up in unexpected ways.

One such thread meanders like this. The celebrity motif returns at about this point, with Marjorie Rambeau (later to have a career as a character actress in movies from 1917 to 1957) performing in Dawson City with a traveling theatrical trouple. Rambeau is not significant here, but Fatty Arbuckle was also in the cast. This information is accompanied by a frame from Fatty’s Day Off (1913), a film discovered in the DCFF.

Shortly after this, we hear of two further celebrities-to-be who were in Dawson City. In 1908, poet Robert Service arrives to work at the Canadian Bank of Commerce, and the following year he writes his first and best-known novel, The Trail of ’98 (1909), about the Gold Rush. From 1908 to 1912, William Desmond Taylor works as a timekeeper on a large gold-mining dredge belonging to the Yukon Gold Company, founded by Daniel and Soloman Guggenheim in 1907. These dredges handled most of the mining, throwing many out of work and causing Dawson City’s population to shrink to 3000. Huge dredges would continue to grind down the land for decades.

In 1912, Taylor left for Hollywood, where he enjoyed a short but prolific career as an actor and director, before, as Morrison foreshadows, his untimely death.

These people disappear for a time, and we learn that in 1911 the auditorium of the DAAA was turned into a movie house, the DAAA Family Theater. Other theaters in town went over to showing films. Morrison conveys this via an amusing montage of shots of people in cinema and theatrical audiences, all from DCFF films. He also provides a quick summary of disastrous nitrate fires during the early 1910s.

There follows a long interlude of coverage of the suppression of laborers and leftists during this period, in part to show off some of the newsreel footage preserved in the DAAA swimming pool. These include the Ludlow Massacre of 1914, the “Silent Parade” protesting violence against African-Americans in 1917, and the World Series scandal of 1919.This somewhat tangential though interesting foray into politics also serves to bring us forward nearly a decade.

The Solax studio fire, which also happened in 1919, provides a rather wobbly transition back to film and Dawson City as the end point of a film distribution line. The population has sunk to 1000 by this point. Since the films shown in the town during this decade were not shipped back to the distributor, many of them were stored in the basement of the Carnegie Library and continued to be through the 1920s.

A long, effective montage of shots from various DCFF films follows, beginning with people listening through doors and going through them, so that we get the impression of a giant house with dozens of people sneaking around. This is followed by shots of men attempting to embrace women and being repulsed.

The last of these is from The Kiss (1914), starring William Desmond Taylor. A caption announces his murder in 1922.

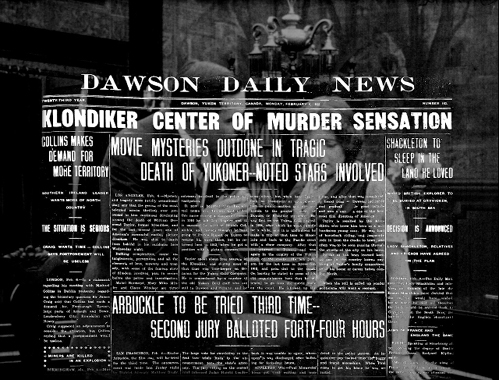

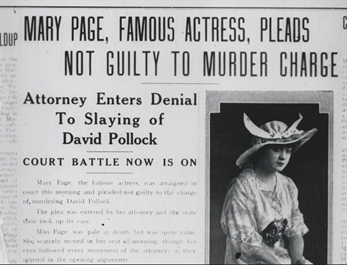

A Dawson City newspaper page announcing the murder and calling Taylor a “Klondiker” and a “Yukoner” is superimposed over another image from The Kiss. Coincidentally, just below this story is one about Arbuckle’s second murder trial ending in a hung jury. The second Taylor headline points out: “Noted Stars Involved.” One of these was Mary Miles Minter, and Morrison shows her in a film, The Little Clown (1921), from the DCFF. Minter had acted in films directed by Taylor, though this is, alas, not one of them. It was however, discovered among the DCFF films. Not one to quit there, Morrison cuts to a shot from another DCFF film, The Strange Case of Mary Page (1916), which has a plot that resembles Taylor’s case.

That two Hollywood directors should have been linked to murder cases, one as victim, one as alleged perpetrator (Arbuckle was never convicted), was certainly a gift to a director keen to stitch as many elements of his film together as possible through associations rather than straightforward historical causes.

Other connections are less elaborate. At the point where the story of Dawson City has reached the late 1920s, The Trail of ’98 (1928), an adaptation of the Robert Service novel mentioned above, is shown via a superimposed poster to be screening at Grauman’s Chinese, another chance confluence of two people who could not have crossed paths in the Yukon, since Grauman left there in 1900.

The burial

All this material has brought us to the point when the accumulating films in the library basement were transferred to the DAAA swimming pool. By 1928 Dawson City had developed a “modest season tourist industry.” Chief Isaac, whom we met early on, had become mayor of Moosehide (above). And Clifford Thomas, the man responsible for putting the film reels in the swimming pool, moved to Dawson City to work at the Canadian Bank of Commerce. He also became the treasurer of the Dawson Amateur Hockey League, which played on the ice rink installed annually over the swimming pool.

In 1929 the library storage had reached capacity, and when Thomson inquired of the studios what he should do with the films, he was instructed to destroy them. At about the time, it was decided to fill in the pool so as to allow for a the skating rink to get rid of a broad bulge caused by the pool’s cover. Thomson made the decision to use the reels as fill in this conversion. Numerous other reels were burned or thrown into the Yukon River–a standard way of disposing of trash.

Morrison could have skipped back to the recovery of the films roughly fifty years later, but instead he continues the Dawson City story. First, he poetically indicates the long decades the reels spent sealed underground with a montage of women asleep, all drawn from DCFF films. The talkies finally reach Dawson City, and more silent reels are dumped or burnt. Chief Isaac dies in 1932.

Parades continue to celebrate the Gold Rush heritage, as recorded by George Black, an avid local amateur cinematographer who recorded several events shown in Dawson City. The one below took place in 1941.

By 1950, the population of Dawson City dropped under 900 people. The last theater was torn down in 1961, though the replica of the Palace Grand went up as a multi-purpose facility in 1962.

On November 15, 1966, the Yukon Consolidated Gold Corporation closed down its last dredge. A lengthy drone shot flies high over the tortuous, unnatural landscape that resulted from many decades of grinding down and spewing out the land (bottom). The ecological thread has not been emphasized through most of the film, but it comes to a devastating conclusion.

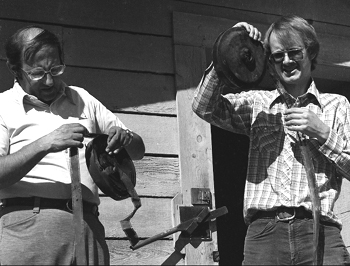

Morrison reaches the discovery of the reels in 1978, and Gates and Jones-Gates resume their story. They contact Sam Kula, Director of Audiovisual Archives, 1973-1989 at the National Archives of Canada. Kula comes to Dawson City, and he (left) and Gates (right) investigate the sodden reels of film.

Kula initially suggested donating the films to the local museum and contacted Kathy Jones. She helped dig up the films, which turned out to be far more numerous and buried far more deeply than they imagined. A newspaper item about the find led to a letter from Clifford Thomson. His explanation of how he had arranged for the films to be put in the swimming pool solved that mystery and provides us with our basic knowledge of the origins of the reels.

The rest of the film’s tale of the reels’ discovery follows how the three rescuers tried to ship the thems to the National Archives of Canada, with several truck, bus, and air services refusing to deal with nitrate film. In November of 1978 a Canadian Air Force plane delivered 506 reels to the Archives.

Morrison ends with a series of shots from various DCFF films with heavy deterioration. The thread of nitrate’s flammability and the recounting of numerous nitrate fires finds its quiet ending in the film’s lengthy final shot. A female dancer performs a modern dance that apparently expresses anguish. Blank white flashes flicker across the frame, suggesting that the dancer is being enveloped by the flames generated by nitrate film.

It is a fitting ending to a film that blends fascinating information and poetic associations in equal measures.

Some caveats

Despite my considerable admiration for Dawson City: Frozen Time, I have to take issue with some of the descriptions in this last part of the film. The narration does not point out that most of the films recovered were incomplete–not surprisingly, given how many reels were burned or otherwise destroyed. A film historian would assume that. A casual viewer would not. Similarly, there is an explicit statement that “every other copy” of these films had been lost to fire and decay. Some of these films, however, survived elsewhere, and sometimes in better copies.

The reception of the film has, through no fault of Morrison, distorted the significance of the DCFF considerably further. This evidently started with a extensive article in Vanity Fair that dubbed the DCFF “The King Tut’s Tomb of Silent-Era Cinema.” Numerous reviewers picked up this idea and repeated it, as when Kenneth Turan began his review, “It’s been called the King Tut’s Tomb of silent cinema, a celluloid find at one of the world’s far corners that dazzled the film universe.”

I cannot think of a more inapt comparison. Tutankhamun’s tomb is one of only two largely undisturbed royal tombs from the entire three-thousand-year history of ancient Egypt, and it is far and away the more important of the two. Despite the tomb’s small size in comparison with others in the Valley of the Kings, an extraordinary number of intact royal grave goods came from it–about 5000 of them (a small sample shown above). Indeed, most of what we know about ancient Egyptian royal grave goods is derived from those pieces. Tutankhamun’s tomb is, as far as we now know, unique.

In contrast, there have been many hundreds of discoveries of original silent films. One of the most notable is the Desmet collection in the Netherlands, which contained over 900 films, most of them complete and in excellent condition. Other such discoveries have ranged from single prints to large collections. Those who have discovered and restored these films are still building the international archival holdings of silent cinema. The Dawson City find is simply one important contribution to this extensive and ongoing effort.

Sam Kula himself wrote, “No-one familiar with the considerable resources now accessible through the work of film archives throughout the world would seriously argue that the Dawson Collection, or any one cache of early film, will lead to a wholesale re-write of the histories.”

The story continued

Morrison essentially ends his account when the films leave Dawson City, which is quite understandable. But the viewer might ask what happened next. There is little attention paid to the lengthy, complex procedures necessary to rescue the films from the effects of their long burial and to transfer their images onto modern negatives.

The Blu-ray release contains a nine-minute supplement, Dawson City: Postscript, which does trace some of the subsequent history of the rescued reels. We see the washing of the films in the Canadian facility, as well as the storage facilities in which the original films were stored once they had been duplicated. In the US, the Library of Congress’ 388 reels are now kept at the Packard Campus in Culpeper, Virginia, which David visited and blogged about earlier this year. Morrison maintains his history of Dawson City as well, noting that in the summer of 1979 the town suffered a disastrous flood and that the premiere of some of the restored films took place shortly after that, on September 1.

At first glance, the Dawson find seems to have been handled in a casual way, with local administrators who were not film archivists digging up reels with shovels and handling them in a way that today would seem reckless. Some have assumed that considerable unnecessary damage was done to the films after their discovery. Yet no written account of the whole affair has yet been published.

I asked our friend Paolo Cherchi Usai, Senior Curator of the Moving Image Department of the George Eastman Museum, for his opinion. He kindly gave me his account of the rescue process, which suggests that the original participants in Dawson City did the best they could under extremely challenging circumstances.

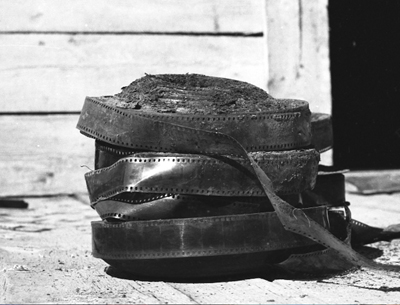

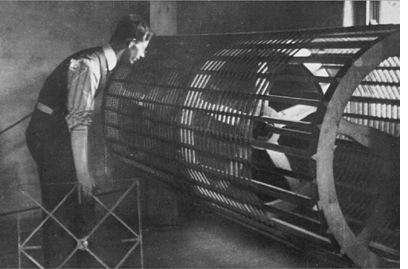

As Paolo wrote in introducing his description, “Please note that what I know is just a matter of oral history — things I heard from the protagonists and witnesses of the events, several years ago. Also, I have not yet seen Bill Morrison’s film.” Others may be able to correct or expand upon some of what Paolo has written. Still, it provides a very informative and useful summary of the rescue process. (I have identified the people mentioned below in brackets. The undated image of a silent-era drying drum is the only image in this entry that is not from Dawson City: Frozen Time.)

In my opinion, the rescue of the Dawson City was a miracle of improvisation and initiative achieved under extremely difficult and often adverse circumstances (see below). In all fairness, I can’t call it a disaster (I can think of other occurrences in my field where that term could rightfully apply). In hindsight, it is all too easy to point out the mistakes made in the process; back in 1978, archival practices were less sophisticated than they are now.

The comparison with Tutankhamen’s tomb is indeed excessive in regard to the aesthetic importance of the films; there is no exaggeration, however, in pointing out the extraordinary circumstances surrounding the discovery, and the steps taken in a very short period of time. You don’t find silent films in a frozen swimming pool that often. When you do, the historical value of the artifacts is not an issue. You want to save all the objects, and then find out their worth. That’s the main reason for the mystique surrounding the discovery; that’s also why I heard about it as soon as I started studying silent film history and film preservation.

It must be pointed out at the outset that the film reels found in the layer right under the permafrost that covered the swimming pool were already decomposed. Nothing could be done to save those prints. It is my understanding that preliminary identification work was undertaken at Dawson City, and that such work was implemented in a cold area. It may be argued that there was no particular reason why this work had to be done there instead than later in Ottawa, but that’s what happened. The late Sam Kula, one of the protagonists (together with Bill O’Farrell [Head of Film Preservation, 1975-2002, National Archives of Canada] and Paul Spehr [former Secretary for the Motion Picture Section of the Library of Congress and Assistant Chief of the Motion Picture Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division of the Library of Congress], among others) of this story, may have been able to explain this.

The reels gradually thawed in at least three stages, during their transfer to a) an air-force base near Dawson City; b) the National Archives in Ottawa; c) the Library of Congress. The thawing could perhaps have been minimized (if not avoided altogether) if the material had been processed in a refrigerated area from beginning to end. This didn’t happen. The nitrate unit at the National Archives of Canada had been shut down to make room for operations on safety materials, and no special precaution could apparently be taken while dividing the collection in two main groups: the Canadian newsreels to be kept at the National Archives, and the American films to be sent to the Library of Congress.

Bureaucracy was the nemesis of the Dawson City rescue project. The only way Bill O’Farrell could bypass it was for him to personally transport the reels of American films from Canada to the US by car, in a large station wagon, from Ottawa to Suitland, Maryland. His heroic feat — perhaps the most important of his career — would have hardly been possible today. He had no choice; following the usual protocol would have taken months, and the emulsion on the prints would have melted completely. Paul Spehr did his part by having the films accepted into the collection in record time, without following the standard acquisition procedures at the LoC. O’Farrell had alerted Spehr that “there is water in the cans” — this is what Spehr heard on the phone, and he expected this to be the case when the material arrived. It’s not that the reels were drenched in a pool of water in each can; but there was water. The prints had thawed.

In that situation, it was deemed necessary to do something about that water. The technical staff at LoC designed and built  a drying drum, similar to those used in film laboratories during the silent era. Because of their size, each reel had to be unwound and cut into sections of approximately 300 feet each. The reels were dried that way. They were unwound while very wet on the edges of the reels, and the emulsion inevitably peeled off from the left and right margins of the frame; hence the distinctive look of the Dawson City films we can see today in reproduced form. I think the very same method for drying the films was applied in Ottawa to the Canadian newsreels.

a drying drum, similar to those used in film laboratories during the silent era. Because of their size, each reel had to be unwound and cut into sections of approximately 300 feet each. The reels were dried that way. They were unwound while very wet on the edges of the reels, and the emulsion inevitably peeled off from the left and right margins of the frame; hence the distinctive look of the Dawson City films we can see today in reproduced form. I think the very same method for drying the films was applied in Ottawa to the Canadian newsreels.

To reiterate the point, the whole story has always been described to me as an emergency rescue performed at breakneck speed, a chain of events where careful advance planning could not be part of the picture. The only way to avoid the partial loss of the emulsion would have been to undertake the entire process in a much colder working area. By the time the reels reached Dayton, however, it would have already been too late to apply such a solution, even if a low-temperature processing area had been available. All that could be done at LoC was to “stabilize” the material long enough for it to go through the printers for duplication.

So that’s that. I hasten to add that my recollections raise a number of questions to which I have no answer.

Our thanks to Paolo for filling in so much of the rest of the story of the Dawson City Film Find.

Thanks to Jonathan Hertzberg of Kino Lorber for his assistance.

The Sam Kula quotation comes from his account of the DCFF rescue, “Rescued from the Permafrost: The Dawson Collection of Motion Pictures,” which can be found on Archivaria: The Journal of the Association of Canadian Archvists #8 (Summer 1979), reprinted from American Film (July 1979).

A brief description of the “Public Archives of Canada/Dawson City Collection” is on the Library of Congress “Motion Pictures in the Library of Congress” page.

THE LOST WORLD refound, piece by piece

Kristin here:

Like just about all kids, I was fascinated by dinosaurs for a while. That’s probably why my mother bought a copy of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s 1912 fantasy-adventure novel, The Lost World, at a yard sale and gave it to me to read while I was sick in bed. I must have been about nine. It was a battered photoplay edition, complete with photos of scenes from the 1925 movie. I read other Victorian-Edwardian fantasy-adventure books, mostly Verne and Haggard, at around the same time. I suppose they prepared me for reading The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings at age 15 and developing a life-long attachment to them. This doesn’t mean that I consider The Lost World a masterpiece, but having come to it so young, I retain a fondness for it. I was interested to find out what the new Flicker Alley release of a new restoration of the film is like.

Doyle’s novel deals with a scholar and explorer, Professor Challenger, who has recently visited a remote site in South America and is ridiculed by all for his claims that dinosaurs survive on an inaccessible plateau there. The hero, Edward Malone, a lovelorn reporter courting a woman who insists she wants a daring, heroic husband, enlists on an expedition to test Challenger’s stories. So does a skeptical rival of Challenger’s, Professor Summerlee, and a hunter-adventurer, Sir John Roxton, who wants to add a stuffed dinosaur to his other trophies. Many adventures follow, including vengeful Spanish guides marooning the expedition atop the plateau, where they encounter dinosaurs, ape-men, and Indians. The team escapes and manages to take a pterodactyl back to London. Challenger’s reputation is restored.

Following on the novel, I saw the 1960 Irwin Allen version of The Lost World. At the age of perhaps ten or eleven I enjoyed it, though I did recognize that Jill St. John’s character was a total and unnecessary fabrication and the “dinosaurs” were lizards with prostheses.

The 1925 version

Naturally when I was a grad student in film studies, I took my first opportunity to see the 1925 version. It was produced by the important studio and distributor First National Pictures three years before it was absorbed by the upstart Warner Bros. In those days the only version available was a 50-minute abridgement made by Kodascope, and it was not, to say the least, impressive.

I cannot say that I paid much attention to the subsequent restorations: the 1998 George Eastman House version, which, while still incomplete, was a distinct improvement, and the the 2000 David Shepard version, which was basically the same but with digital improvements to sound and image.

The 2016 restoration by Serge Bromberg’s Lobster Films as presented now on Blu-ray by Flicker Alley, has added considerable footage. This extends the film to 103 minutes, close to its original running time. The main thing missing is a scene of cannibals attacking the expedition members as they travel upriver to the controversial plateau, as well as a few other brief moments.

As an adaptation, it’s a distinct improvement on the 1960 version. After all, the novel was only 13 years old when it was made. Doyle was still alive; he would not publish his final Sherlock Holmes story until 1927 and his final works of fiction until 1929. Conventions and tastes in popular fiction, whether filmic or literary, had not changed nearly as much as they had by Irwin Allen’s day.

The main casting was impeccable, with Wallace Beery the perfect choice for the powerful, pugnacious Challenger (above) and Lewis Stone for the epitome of British stalwart rectitude. The film even managed to do a good job of concocting a love interest by introducing Paula White (Bessie Love), the daughter of the original discoverer of the lost-in-time plateau and eager to participate in an expedition to rescue her marooned father. Then it gave her little to do. Bessie Love just has to look terrified at intervals, in a series of close-ups surrounded by an iris and with a blank background–clearly shot later with someone telling Love just to glance in all directions and register fear. These moments add up to something a realization of a Kuleshov experiment.

Her presence does, however, allow Stone to give perhaps the most subtle and sympathetic performance in the film. He’s in love with White but nobly gives her up to Malone. As Malone, Lloyd Hughes manages to look suitably handsome and impetuous. Arthur Hoyt, older brother of director Harry O. Hoyt), plays Professor Summerlee. His many “little man” roles later included the hotel owner in It Happened One Night, and he was one of Preston Sturges’ regular actors. (“Looking perpetually befuddled was Hoyt’s stock-in-trade,” as I. S. Mowis puts it in his IMDb biography of Hoyt.) Unfortunately the film exaggerates Summerlee’s somewhat amusing traits, thereby making him a strictly comic character. (One wonders how Claude Rains, so very dissimilar from Beery, could be chosen for the same role in the 1960 version. Casting against type, presumably.)

By the way, although the film seems basically to be set in the Edwardian era of the novel’s original publication, the introduction to the final London portion of the story shows Piccadilly Circus at night, including a movie palace show The Sea Hawk (1924), another First National release that included Wallace Beery and Lloyd Hughes (Malone) its cast.

A little synergy that brings the story up to date.

Puppets and people

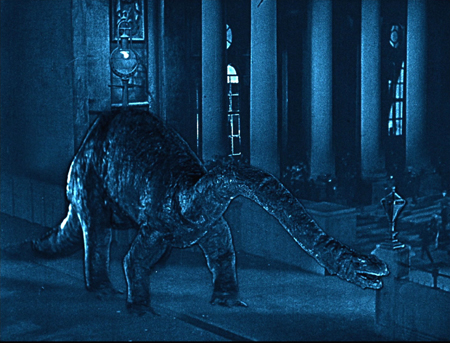

The main attraction of the film, of course, is its technology. Some of it was quite innovative. It is thought to be the first time when the special effects of a feature film were largely accomplished through puppet animation.

There had been earlier puppet films, including Ladislas Starevich‘s realistic creation of artificial insects apparently acting out conventional melodramas. Accomplished though they were, these did not mix live-action with real actors in the same shots, as do the miniature landscapes with the moving dinosaurs.

In The Lost World, combinations usually involve the actors placed in the lower foreground, observing the dinosaurs from varying distances. Atop this section, for example, in a very skillfully done shot, an allosaurus approaches the campsite of the expedition members. The place where the live-action at the lower right joins the miniature set at the upper left is difficult to discern, and the careful lighting of both areas aids in the illusion.

The late scenes of the film, where a brontosaurus escapes into London’s streets and causes panic resorted to a new and complex technology, moving mattes. This device involved using stencils cut for each frame and doubly exposing prints from two negatives. Moving mattes allowed figures filmed separately to be inserted into scenes without the use of superimpositions. The result usually was fairly obvious, betrayed by an evident join line around the added figure. Differences in texture and lighting also caused problems. Still, given the technical limitations of the day, the results are impressive. (The most famous use of moving mattes in this era was probably the reunited couple’s oblivious stroll through traffic in Sunrise.)

The Lost World drew more heavily on stationary mattes, and for the most part, the technology is pretty convincing. The scene of the allosaurus-triceratops-pterodactyl fight (at the top) contains a stationery matte. The lower part of the frame is a river with plants on the banks swaying in the breeze. About a third of the way up the composition, there is a join to the miniature set in which the action was animated. There the plants are completely stationery, but the movement of the real plants in the lower area gives a degree of verisimilitude to the whole scene. The shot of the team confronting the allosaurus at the top of this section also uses this technique.

Digital copies let us pause and figure out some of O’Brien’s secrets. After the allosaurus has dispatched the unfortunate triceratops seen in the image at the top of this entry, a dramatic moment occurs in a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it flurry of motion as it suddenly snatches a pterodactyl in mid-flight and kills it. Pausing on the action, we can see that O’Brien used wires to support the allosaurus during its leap, as well as nearly invisible wires along which to slide the pterodactyl. I didn’t notice any other scenes in which O’Brien had to resort to visible props.

And at least the dinosaurs, unlike King Kong, didn’t have fur that ruffles almost continually, betraying the movements of the animators’ fingers in between exposures of the frames. As a result, the animation in The Lost World almost looks more sophisticated than that of Kong.

Moreover, O’Brien’s puppets, constructions of rubber and foam over metal skeletons, included balloons inside that could have air pumped in and out to simulate breathing. It’s a measure of the man’s inspiration that he realized how much this technique would contribute to the lifelike quality of the dinosaurs.

One of the supplements gives another insight. It is listed as “Deleted scenes,” or outtakes, but occasionally O’Brien or perhaps one of his assistants (the footage is too indistinct to tell which) pops into the image for a few frames, incongruously appearing submerged to his waist in a primordial landscape.

Such images give a sense of the considerable scale of the miniature landscapes and the puppets, as well as the labor involved in this novel endeavor.

The new print

This newest restoration, having been cobbled together from many disparate elements, inevitably is variable in its visual quality. Much of it is splendid, as indicated in most of the images reproduced in this entry, especially the one at the top. Others are clearly worn, with light lines, as in the shot above of Challenger and Summerlee watching a brontosaurus pass in the background. Again a matte shot has been used, its joint probably running along the top of the little sandy ridge behind which the men hide.

The rather poignant scene of the dinosaurs fleeing from a volcanic eruption is unfortunately worn as well. Such stretches, however, are in the minority.

The new version also includes tinting and toning based on recently discovered footage, as well as a brief scene combining red and blue colors when Malone throws a torch into the mouth of an allosaurus to drive it away.

The disc comes with a booklet by Bromberg outlining the extensive restoration work on the versions of The Lost World, as well as the disc’s two musical-track options, one by Robert Israel and one by the Alloy Orchestra. Supplements include a commentary track by Nicolas Ciccone and some short films and clips by O’Brien. The Silent Era website offers a detailed rundown on the many video releases of The Lost World. Once more Lobster Films and Flicker Alley are to be congratulated on another contribution to the retrieval of cinema’s history.

Lubitsch redoes Lubitsch

DB here:

All artists rely on predecessors in one way or another. True, at any moment the artist may confront a dizzying array of options; there are a lot of models out there. And sometimes artists work against received traditions rather than building on them. (Usually, though, those assaults on tradition borrow from other traditions, often minor ones.)

Anyhow, it’s a good first move to assume that any artwork we encounter owes something to forebears. If we want to understand continuity and change in film history, then, we can try to know something about genes, styles, received habits, work routines, and other ongoing pressures on moviemakers.

Schema and revision

Favorites of the Moon (Iosseliani, 1984).

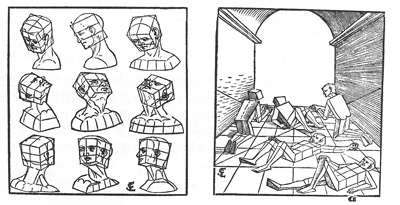

Among the strategies for making sense of a given film or filmmakers, one I’ve found useful I’ve swiped from E. H. Gombrich. In Art and Illusion, he wrote of schema and revision as one way of thinking about an artist’s ties to tradition. A schema is a pattern that has proven reliable for art-making in the past. His examples are the geometrical templates that became part of the training of Western European artists.

Gombrich suggests that artists adapt the schemas to the purposes at hand–new tasks, or the urge to capture aspects of reality that their predecessors missed.

Once a hack has learned how to make the image of a tolerably convincing head, he may be tempted to use this standard formula for the rest of his days, merely adding just such distinguishing features as will mark the admiral or the court beauty. But obviously once he is in possession of a standard head, he can also use it as a starting point for corrections, to measure all individual deviations against it. He may first draw it on his canvas or in his mind, not in order to complete it, but to match it against the sitter’s head and enter the differences onto his schema.

Hence the Gombrichian slogan: Making precedes matching. You render a version of visual reality in and through the forms bequeathed to you by tradition, adjusting them as you may need.

In film, I suggested in On the History of Film Style, we have several stylistic schemas. A prototype would be shot/ reverse-shot staging and cutting. You can replicate the schema, just running it again, as most filmmakers do. (All those damn shoulders.) You can revise it, as Ozu, Bresson, and other filmmakers did. You can adapt it to the long take, as Hitchcock and Iñarritu did. Or you can reject it, as Tati and Iosseliani did with their extreme long-shots. Iosseliani: “As soon as I see a film that begins with a series of shots and reverse shots, with lots of dialogue and well-known actors, I leave the room immediately. That’s not the work of a film artist.”

Stylistic schemas are perhaps the easiest to spot; when they cluster, we get something like a style in a general sense, such as continuity editing, or more recently what I’ve called “intensified continuity.” Even minor genres, like long-take lipdubs, have their own schemas. And revisions are ongoing. In mother! Darren Aronofsky fills the “free-camera,” run-and-gun handheld style, which usually favors medium shots, with extreme close-ups that put menacing, barely identifiable action in out-of-focus backgrounds. The result can be seen as a revision of the blink-and-you’ll-miss-it reframings on display in the Bourne films.

There are schemas for narrative too. At the broadest level, the sacred Three-Act Structure can be thought of as a macro-schema; so too the more fleshed-out Four-Part Structure Kristin has proposed. In my new book Reinventing Hollywood, I invoke the schema/revision idea to talk about more specific narrative strategies of the 1940s. Examples are the flashback plot, with a shuttling between present and past, and the network narrative, which brings friends, kinfolk, and strangers together in a limited time or space.

Watching Ernst Lubitsch’s Rosita (1923) again at the Venice Film Festival reminded me that the schema/revision process can take place not just between the filmmaker and tradition but within the work of a director. Once a director develops a “signature style,” that too can be reworked, refined, stretched, or even repudiated. Griffith recast his characteristic last-minute-rescue crosscutting pattern, once by making the rescue too late (Death’s Marathon), and once by multiplying it by four (Intolerance). Ozu not only revised Hollywood continuity principles, but then tweaked and played games with his customized version. Arguably, Hitchcock did the same with his refined point-of-view structures and man-on-the-run plot patterns.

In the Lubitsch case I’m considering, we have a very tiny piece of schema revision, but one that shows him to be a fastidious creator. Having sculpted a small moment one way, he extracted its principles and remade it, for other purposes in another film.

The grapes

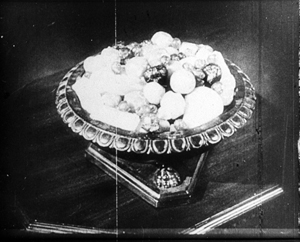

The street singer Rosita is in the palace waiting for the king. At first she’s awed by the scale of the room, but then she spies a bowl of candied fruit on a little table. As often happens in Lubitsch’s American silents., this plays out through eyeline cutting.

Rosita heads out of her shot and a frame-edge cut brings her to the table. She drifts past the fruit, eyeing it, and now the sequence’s rhythm is established.

When Rosita leaves the frame, the camera holds on the table and the fruit bowl.

After a beat, she strolls into the frame moving right, pointedly ignoring the fruit. She goes out of frame and Lubitsch holds on the bowl.

Then Rosita comes in from offscreen right and plucks a grape as she passes through the frame. Lubitsch holds the empty shot.

Rosita comes in again from the left, snags another grape, and walks out frame right.

After another beat, she thrusts back into the frame and starts to dig into the fruit.

She’s hungry but afraid of being caught, so she swipes the food as casually as she can. Once she thinks she’s not being watched, she can take what she wants.

Instead of cutting the action up, Lubitsch holds the shot and makes a sort of contract with the viewer. The gag depends on simple spatial continuity; we know where Rosita is when she’s out of frame, so we can anticipate her coming back in and wonder what she’ll do on the next pass. By holding on the table, the camera “knows” she’s coming back and waits for her; the bowl draws her like a magnet. We enjoy the game of expectation Lubitsch has set up.

Simple as it is, this passage shows the patterned nature of a stylistic schema. You could plug different things into that pattern—a bed rather than a table, a gun on a counter, a detective casually looking for clues—but as long as you set up the pause holding on the “empty” frame as the actor passed through to and fro, we’d have a recognizable schema. It’s one that other filmmakers could use.

Or one that Lubitsch himself could cleverly revise. If the Rosita version builds a mild sort of suspense, what if we added a dose of surprise? That’s what happens in Lady Windermere’s Fan (1925).

The drawer

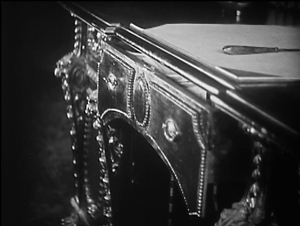

Lord Darlington, hoping to drive a wedge between Lady Windermere and her husband, suggests that she look for a check Lord W wrote to the mysterious Mrs. Erlynne. Lady W walks into the study and pauses at her husband’s desk, then goes to sit in a chair nearby.

Like Rosita studying the fruitbowl, she eyes the desk drawer holding the check.

She rises and, thanks to another frame-edge cut, walks to the desk. But thinking the better of it, she leaves the frame, going out left.

The camera stays on the desk. Pause.

Suddenly Lady W bursts into the frame, but from the right side.

Lubitsch, who understood the rules of continuity better than almost anybody, knew perfectly well that she should have come back in from the left. The actor had to go around behind the camera in order to come in from this “impossible” angle. We’d be startled to some extent if Lady W had suddenly burst in from the left, but now the effect is amplified by the unpredictable entrance from the right. To spatial suspense, holding on the desk, Lubitsch has added spatial surprise.

Interestingly, there’s another anomaly here: the early POV shot of the drawer. It represents what Lady W sees, but from the opposite angle, from the “other side” of the desk. A shot respecting her vantage point would have looked like this.

Since this is a silent film, even if Lubitsch had made a mistake during filming, the shot could have been flipped in postproduction to look correct. It’s just possible that this “wrong” POV shot is another schema revision–one that anticipates Lady W’s “wrong” reentry into the desk shot. This possibility is strengthened soon afterward when Lady W tries to open the drawer, in a framing that shows the “correct” angle.

And soon afterward, when Lord Windermere joins his wife, he will look at the drawer from the “correct” angle as well.

A spare take of his POV shot could have replaced Lady W’s mismatched one. (Though the fastidious Lubitsch gives us a slightly different angle from Lady W’s, one corresponding to the position of Lord W). It seems likely, then, that Lubitsch simply wanted Lady W’s odd POV shot. Perhaps he saw it as a cryptic hint that something important was about to happen on the other side of the desk, where Lady W will pop in.

With Lubitsch, we’re always getting into such pictorial niceties. In any case, having tried out the “waiting camera” schema in Rosita, garnished it with predictable frame entrances and exits, Lubitsch revised the schema to create a different effect. He knew that audiences would expect Lady W to reenter the way Rosita did, and he exploited our expectations to yield a bump of surprise–one that increases the expressive effect of her pouncing on her husband’s secret.

More generally, the concept of schema/revision seems to me a useful tool for studying a filmmaker’s ties to tradition, as well as his or her developing personal style. This is not to mention the role of rivalry, another important pressure for continuity and change in film craft. Once a schema is out there, people can compete for ways to revise it. But that’s a topic for another day.

My frames from Rosita are from the standard, rather bad surviving print. It has recently been restored by the Museum of Modern Art under the auspices of Dave Kehr, and the new version looks very fine. More information here.

The illustration of heads comes from Erhard Schön’s manual of 1538, reproduced in Gombrich’s Art and Illusion (Princeton University Press, 1960), p. 159; my quotation comes from p. 172.

The quotation from Iosseliani comes from “Iosseliani on Iosseliani,” in The 24th Hong Kong International Film Festival Catalogue (Hong Kong: Urban Council, 2000), p. 138.

Kristin provides close analysis of Lubitsch’s silent film style in Herr Lubitsch Goes to Hollywood: German and American Film after World War I, available online here. I discuss this sequence from Lady Windermere in more detail in Chapter 9 of Narration in the Fiction Film. But when I wrote that, I hadn’t seen Rosita. I consider how Ozu varied his bespoke version of continuity editing in Chapters 5 and 6 of Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema, available online here.

Fruitbowl, Mary Pickford, Ernst Lubitsch, and Holbrook Blinn on the set of Rosita.

Venice 2017: Lubitsch and Pickford, finally together again

Rosita (1923).

KT here:

Few of Ernst Lubitsch’s and Mary Pickford’s silent films are as little known to modern viewers as Rosita (1923). It survived only in an incomplete print in the Soviet film archive, and a few other archives had copies of that print. Specialist researchers could see it, as I did while working on Herr Lubitsch Goes to Hollywood. (You can get a downloadable copy here.) Now the Museum of Modern Art has made a 4K restoration that played here at the Venice International Film Festival as a special screening on the night before the festival opening. Curator Dave Kehr introduced the film.

Rosita has gained an unwarranted reputation as an inferior Lubitsch film. In Kevin Brownlow’s interview with Mary Pickford published in The Parade’s Gone By, Pickford claims that she was not happy with Rosita and parted ways with Lubitsch as a result. As I detail in Herr Lubitsch, however, correspondence between Pickford and Lubitsch reveals that a few years after Rosita, Pickford was still on cordial terms with him and asked for help on the editing of Sparrows. Why she made such a story up is anybody’s guess, but no one should see it for the first time believing that Pickford’s negative opinion, expressed late in her life, was her view of the film in the 1920s.

Rosita was Lutbitsch’s first American film, though as I show in my book, he had learned American style while still working in Berlin and that it shows in his last two German films, Das Weib des Pharao (1922) and Die Flamme (1923). Rosita is a neat blend of Lubitsch’s two favorite genres during his German period, comedy and historical epic.

The plot has Pickford as the title character, a Spanish street singer and dancer (see top) who catches the eye of a philandering king. Despite the actress’ reputation as a sweet young thing with sausage curls, she was quite versatile. Here she plays a street-wise, confident young woman clever enough to hold off the king’s advances while tricking him into lavishing her and her family with clothes and a villa.

There’s also a handsome soldier; Rosita falls in love with him and must save from the gallows. His plight furnishes the more serious and suspenseful side of the plot.

Lubitsch uses the big sets and crowds that he had become famous for with films like Madame Dubarry (1919) and Anna Boleyn (1921). Working with a Hollywood budget, he created some huge vistas, including a street scene near the beginning where carnival revelers are seen from the foreground to the very distant background (with a glass shot providing the towers; see bottom). The endlessly tall prison wall is another impressive setting.

The print we have seen up to now was not in good shape visually, being quite contrasty with blown-out highlights. The MOMA has done an impressive job of restoration, improving the visual quality distinctly. The intertitles in the surviving print, being in Russian, had to be replaced by using many sources. One reel preserved by Pickford herself provided the visual design template (still photos of scenes used as backgrounds for art titles). The texts were translated from Russian, gleaned from Swedish and German censorhip lists, an early draft of the screenplay held by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, a few lines quoted in reviews of the time, and a music cue sheet preserved at George Eastman House.

Gillian Anderson described to us the process of reconstructing the original score. It “was actually created from the 1923 cue sheet by James C. Bradford based on the original score by Louis F. Gottschalk. I located 45 of the pieces called for in the cue sheet (from collections all over the world, including the LC), timed each scene, cut each piece of music to fit each scene (the music was specified by the cue sheet). I only orchestrated one piece. Then I created the piano conductor score and then cut and pasted each of the orchestral parts. to match. The orchestrations for all but one of the pieces were the original orchestration from the teens and twenties.”

Gillian Anderson described to us the process of reconstructing the original score. It “was actually created from the 1923 cue sheet by James C. Bradford based on the original score by Louis F. Gottschalk. I located 45 of the pieces called for in the cue sheet (from collections all over the world, including the LC), timed each scene, cut each piece of music to fit each scene (the music was specified by the cue sheet). I only orchestrated one piece. Then I created the piano conductor score and then cut and pasted each of the orchestral parts. to match. The orchestrations for all but one of the pieces were the original orchestration from the teens and twenties.”

The result works beautifully with the film, as Anderson demonstrated when she conducted the Mitteleuropa Orchestra to accompany the presentation (right).

Rosita may not be among Lubitsch’s greatest films, but it is charming both in itself and as a display of Pickford’s talents. He would go on to discover the genres that made him one of Hollywood’s top directors. In place of the delightfully broad comedy of his German comedies like Ich möchte kein Mann sein (1918) and Die Puppe (1919) he discovered the sophisticated romantic comedy in such masterpieces as The Marriage Circle (1925) and Lady Windermere’s Fan (1926). It would serve him well in the sound era with Trouble in Paradise (1932), The Shop around the Corner (1940), and others. Earlier, as sound came in, he turned out a variant of the genre in a brief series of romantic musical comedies (e.g., The Love Parade, 1929; The Smiling Lieutenant, 1931).

The applause after the screening of Rosita was enthusiastic and prolonged. The restoration should receive wide circulation at festivals and archival series, as well as on Blu-ray–presumably with this score included.

Our Rosita images come from a print derived from the Russian version. The MoMA restoration is far more crisp and clear.

Thanks for Gillian for correcting our original brief description of her work on reconstructing the score and for providing a more detailed account of how she did it!

Rosita (1923).