Archive for the 'Silent film' Category

Ritrovato 2017: An embarrassment of riches

Place de la Concorde (somewhere between 1888 and 1904)

KT here:

David’s recent entry stressed the world-wide scope of offerings here at Il Cinema Ritrovato. The time period covered is even broader–this year as broad as it could possibly be. The final night’s film in the Piazza Maggiorre will be Agnès Varda and JR’s prize-winning documentary straight from this year’s Cannes festival, Visages Villages, with Varda here to introduce it. Yesterday we saw a work that may have been created before the cinema itself had been properly invented.

The earliest years

Somewhere in the time period 1888 to 1904, French scientist Etiennes-Jules Marey created a huge photographic format, a filmstrip 88 mm wide and 31 mm high. He exposed a series of images along this broad strip but never intended to project them as a film. As with much of Marey’s work, these high-quality photographs were tools to allow him to analyze movements, in this case those of humans and horses in the Place de la Concorde.

The National Technical Museum in Prague has scanned this series of frames to create a digital copy that can be projected in motion. The results, lasting only 45 seconds, has a clarity and detail that seems to rival that of Imax film. (The image at the top only hints at the effect.) We watched the piece four times and would have been glad to see it at least as many more.

A major thread running through the festival is the year 1897, which, although only the second year of the established film industry, already saw the making of many beautiful and intriguing films. Among the ones shown here were films made by the American Mutoscope Company (later known under the more familiar name, American Mutoscope and Biograph) and British Mutoscope and Biograph. These films, made to be shown in both peepshow machines and projected onto screens, utilized a 68 mm format.

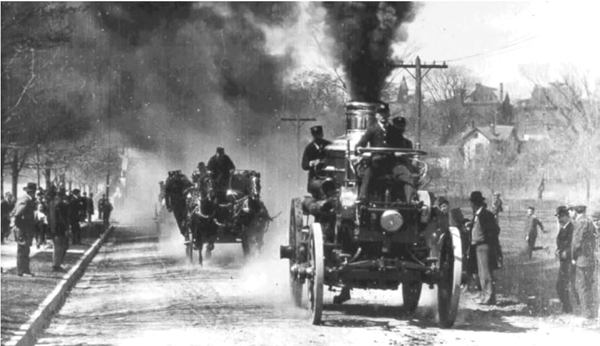

Such films have mainly been seen in poor prints that give an impression of primitive crudeness. Thanks to preservation work on collections in the EYE Filmmuseum and the BFI-National Archive, the richness and clarity of these films have become evident, and they look anything but primitive. One American film (above) is Jumbo, Horseless Fire Engine, credited to William Kennedy-Laurie Dickson himself, provides what must have been an exciting variant on the many films featuring horse-drawn fire engines racing along streets.

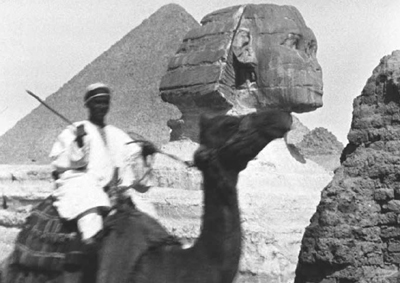

One of the Lumière company’s most prolific traveling cameramen was Alexandre Promio. I was naturally intrigued by series he filmed in Egypt in 1897. One thing that struck me about 28 films in the program was how few featured famous tourist attractions and truly picturesque images. True, Les Pyramides (vue générale) shows one of the most familiar ancient sites in the world, the Sphinx against the great pyramid of Khufu.

Most of the rest of these brief films are remarkably mundane, however. Place de la Citadelle shows an open space with a nondescript building in the distance rather than the two main attractions of the Citadel, the Mosque of Mohammed Ali and the spectacular view out over the city. Village de Sakkarah (cavaliers sur ânes) shows fellahin riding donkeys in modern Mit Rahina, but in the background the colossal quartzite statue of Ramesses II lies on the ground (where it still lies today, covered by a shelter). It is a beautiful statue, visited by nearly all tourists, and yet in the film it is merely a distant, vague shape, identifiable only to those who are familiar with it.

Numerous other views are moving, taken either from trains and showing ordinary industrial buildings or from boats, showing mainly palm trees. The collection leads one to speculate what prompted Promio to choose his subjects.

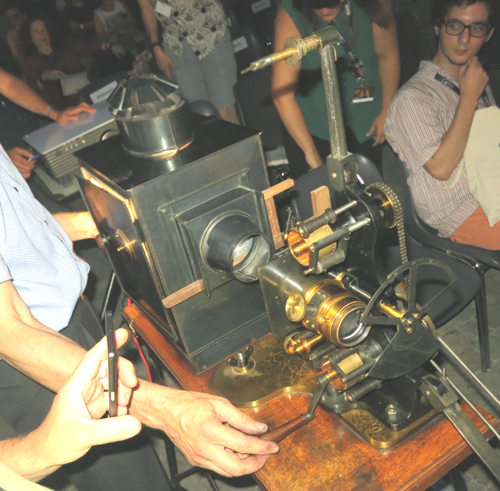

I believe the tradition of showing films in the open air of the Piazzetta Pier Paolo Pasolini (the courtyard of the Cineteca di Bologna) on carbon-arc projectors began in 2013, which I reported on it. This popular feature has expanded, with three programs this year. The first centered around Addio, Giovenezza!, which David described in his entry. The second was particularly special, with a five early shorts ranging from 1902 to 1907 shown on a vintage 1900 projector, hand-cranked by Nikolaus Wostry of the Filmarchiv Austria. The films were charming, but the star of the show was the projector. It looked like a magic lantern dressed up with special attachments that allowed for moving pictures, including a shutter sitting in front of the lens rather than within the body of the lantern. Indeed, the thing looks like a magic lantern converted into a film projector.

This projector cast a much smaller image than the later carbon-arc projector used for the second part of the show. The image had rounded corners and it flickered distinctly. At times, despite Wostry’s obvious expertise at hand-cranking, the image would briefly go to black. Watching this presentation, it became easy to grasp how early audiences might have been constantly aware of the artifice, the machine, creating these images and have marveled at any sort of moving photographs that were cast on the screen before them. It was a magical few minutes, making almost real the section of the program entitled “The Time Machine.”

Classics of 1917

Although there was some thought of ending the Cento Anni Fa programs once the feature film became established, that has fortunately not been done. Instead, a mixture of shorts and features continues to celebrate the cinema of a century ago. Some of the Italian films David wrote about came from that year.

I had the chance to see two masterpieces from that year back to back: André Antoine’s Le coupable and Victor Sjöström’s The Girl from Stormycroft. Both center around the subject of women seduced and left pregnant by their selfish lovers.

I had never seen Le coupable. Antoine is often referred to as a naturalist theatrical director, but going by Le coupable and La terre (1921), he is equally a major film director in the realist tradition, though his output consisted of only nine films from the brief period 1917 to 1922.

While La terre was filmed largely in the countryside, Le coupable was shot in the streets of Paris, and many of its interiors seem to be set in real rooms. Antoine manages to combine the gritty realism of his lower-class milieux with beautiful cinematography (see bottom image). The story takes the unusual form (for its day) of a lengthy series of flashbacks framed by a trial of a young thief and murderer. The past does not unroll from witnesses’ testimony, however, but from one of the presiding judges’ lengthy confession that he is the father of the accused and had abandoned the boy’s mother. The situation is pure melodrama, but Antoine’s light touch and feel for the settings of the action make it a masterpiece.

The Girl from Stormycroft has the distinction of being the first adaptation of a novel by internationally popular author Selma Lagerlöf, whose work was to be the basis for several classics of the Swedish silent cinema, including The Phantom Carriage and Stiller’s The Saga of Gõsta Berling (1924). It is set in the countryside, in a group of small villages. Helga, the heroine, has been seduced by a married man who refuses to acknowledge her child as his own. In a key trial scene, she gives up her suit against him to prevent his committing a sin by swearing to a lie on the Bible. This gains the admiration of a well-off and kind young man, Gudmund, who persuades his mother to take Helga on as a maid. When his fiancée and her parents visit Gudmund’s family, they express disgust at her presence and depart (above), leaving Gudmund is left with doubts about his upcoming marriage.

Early sound films

Il Cinema Ritrovato’s programs offer an opportunity to sample early sound films from a much wider range of countries than usual. Gustav Machaty, best known for Ecstasy (1933), made From Saturday to Sunday in 1931. It follows a pair of working girls who go out to a ritzy nightclub with two wealthy men, intending to exploit the two for a lavish night out while avoiding their sexual demands.

This proves more difficult than they expected, and we end up following one of the pair as she is stranded late at night in the pouring rain. As the title suggests, the action is a slice of life, lasting less than 24 hours. Machaty manages to blend the visual style of the late 1920s with a firm grasp of sound technology. The result is an entertaining if rather conventional tale.

Mexican filmmakers seem to have proved equally adept at taking up sound. The program notes for the program “Rivoluzione e avventura: Il Cinema Messicano dell-Epoca d’Oro” point out that Mexican production burgeoned in the 1930s, going from one feature in 1931 to 21 in 1933.

The earliest film in this thread, El Compadre Mendoza (1933), is a technically and stylistically impressive film, looking like a Hollywood film of the same era. It’s part of a trilogy about the Mexican Revolution, coming between director Fernando de Fuentes’ El prisionero 13 (1933) and Vámonos con Pancho Villa (1935), though it is quite comprehensible and enjoyable on its own.

The irony of the title is that the protagonist, a jovial, sociable plantation owner, is professing loyalty to both sides, and for years he manages to live a pleasant life with his family and staff on their large hacienda. The film is remarkable in portraying the Revolution almost entirely offscreen. The narrative sticks mostly to Mendoza’s house, and we gauge the progress of the fighting purely through a series of sequences in which either revolutionary or government troops ride up the long, tree-lined road to the house. There Mendoza and his household provide a bit of socializing, putting up an effective façade of loyalty to whichever army is present at the time.

Mendoza develops a particular friendship with Felipe, a Revolutionary general (above), who also attracts Mendoza’s young wife in what develops into a lengthy unconsummated romance. Inevitably Mendoza’s juggling of the two sides collapses as he is forced to help one of them against his will.

For me the most unexpected discovery of the festival was the second Mexican film, Two Monks (1934). It is considered the first in the Mexican Gothic genre. It was inspired by the Spanish-language version of Dracula (directed in 1931 by George Melford for Universal), as well as by German Expressionist films.

There are no monsters in the film. Instead, a frame story set in a monastery that looks straight out of Murnau’s Faust (1926) introduces a young monk, Javier, who has gone mad. He attacks another monk, Juan, with a crucifix and confesses to the prior that he did so because Juan had committed a terrible crime. A lengthy flashback lays out the story of Javier’s love for Ana and his eventual rivalry with Juan. In the second half, Juan also confesses, and the story is repeated from his point of view. Scenes we saw earlier are replayed, often starting at an earlier point or ending at a later one, in a way that alters our understanding of the two monks’ past relationship. The result is not a Rashomon-type situation, for the two men agree on the events they describe, disagreeing only on the implications of those events.

It’s a remarkable narrational technique for this early in film history. The atmospheric claustrophobia created by the small cast (no passers-by are seen in the brief street scenes and no servants appear in the houses) and of dread created by the sets and the dissonant music of the climactic scene would bear comparison with the horror films of Universal and Hammer.

Restorations that make me feel old

Film restoration has been around for decades, but at some point within the several years I noticed that an increasing number of films were being restored were ones that I had seen when they first came out or shortly thereafter. Modern classics restoration wasn’t just for silent films and movies from the golden studio era. Now they’re for modern classics: The Graduate, Belle du jour, Women in Love, Blow-Up, and Day for Night (not to mention the restorations shown at Il Cinema Ritrovato in past years).

My first thought is, why do such recent films need restoration? Answer: maybe they’re not as recent as they seem to me. My second thought is, haven’t the studios realized that they need to take care of their films? Answer: Yes, to some extent, given the vital work done by studio archivists like Grover Crisp and Shawn Belston. Still, will There Will Be Blood be neglected until it needs restoration in twenty years’ time?

My first thought is, why do such recent films need restoration? Answer: maybe they’re not as recent as they seem to me. My second thought is, haven’t the studios realized that they need to take care of their films? Answer: Yes, to some extent, given the vital work done by studio archivists like Grover Crisp and Shawn Belston. Still, will There Will Be Blood be neglected until it needs restoration in twenty years’ time?

Among the relatively recent films presented in restoration here is Med Hondo’s West Indies (1979). The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project undertook to restore a number of films by Hondo, a Mauritanian actor and director and one of the most important directors from the African continent.

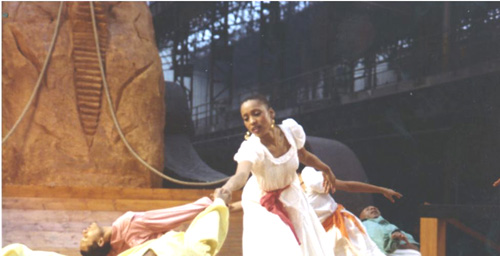

West Indies is a remarkable film, a musical on the history of French slave-owning in its Caribbean colonies. Inside an empty factory Hondo built a large set depicting the upper and lower decks of a slave ship. The various sections of this ship provide stages upon which scenes, anything from a 1968 demonstration in the streets of Paris to a slave auction hundreds of years before. Five actors representing colonial interests, including a black man who cooperates in order to maintain his position as a figurehead governor, take similar roles throughout the action.

It’s a lively, entertaining film, done in color and widescreen, as well as a maddening look at French complacency and casual cruelty. Most of the musical numbers are dances rather than songs, with Hondo himself having choreographed several of them.

Hondo, now 81 and reportedly seeking backing for another film, was present at the festival and introduced the screening of West Indies that we attended. He was visibly moved by the chance to show this little-known work to an appreciative audience and thoroughly won us over during his brief presentation. With luck we will see a tenth film from him.

Thanks to Guy Borlée for his assistance with this blog, and to the programmers and staff of Ritrovato for another dazzling year. You can download the entire festival catalogue here.

Kelley Conway reviewed Visages Villages at Cannes for our blog.

Le coupable (1917)

Ritrovato 2017: Drinking from the firehose

DB here:

Immense scale and teeming activity are nothing new to Il Cinema Ritrovato, the Cineteca di Bologna’s annual jamboree of restored and rediscovered films from all over the world. The scorching heat–90 degrees and more for the first few days–only makes it seem more intense than usual.

Kristin and I had to miss the last Ritrovato session, but we’re convinced that this nine days’ wonder is still the film-history equivalent of Cannes.

In one way, your choice is simple. You can follow one or two threads–say, the Robert Mitchum retrospective or the Collette and cinema one or the classic Mexican one, or whatever–and dig deep into that. Or you can skip among many, sampling several, smorgasbord-style.

In practice, I think most Ritrovatoians pursue a mixed strategy. Settle down one day for a string of, say, early Universal talkies and another day check out the restored color items. On off-days roam freely. The problem is you will always, always miss something you would otherwise kill to see.

At the start, I plumped for 1910s films, particularly Mariann Lewinsky’s reliable 100 Years Ago cycle. My other must was the Japanese films from the 1930s; half of the titles brought by Alexander Jacoby and Johan Nordström, were new to me. As of this writing, I haven’t seen those, but I have dug into the 1917 items. And I indulged myself with, no surprise, some gorgeous Hollywood things.

1917 and all that

Malombra (1917).

If you caught any of my dispatches from Washington DC earlier this year (starting here) you know I was burrowing deep into American features of the 1910s That complemented several years of archival work on European films of the same period. So of course the chance to sample 1917 features from Hungary, Poland, Russia, and elsewhere was not to be passed up.

Some superb ‘teens films I just skipped through familiarity. Gance’s Mater Dolorosa (1917), possibly the most patriarchal film in the thread, remains tremendously inventive at the level of silhouette lighting and continuity cutting (a huge variety of camera setups during the fatal love tryst). And one of the very greatest directors of the period, Yegenii Bauer, was represented by two of his last films, The Revolutionary and Towards Happiness. I’ve studied both elsewhere, in On the History of Film Style, Figures Traced in Light, and online. Even so, I found plenty to keep me busy.

One of the main threads was devoted to Augusto Genina, a director with an astonishingly long and prolific career. Probably best known for Prix de Beauté (Miss Europe, 1930), he started in 1913 and made his last film in 1955. His 1910s films confirm that Italy was producing many films of striking beauty and audacity in those years.

Take Lucciola (1917, right), the story of a waif who befriends a harbor layabout but leaves him to become a society princess admired by a debonair painter and three bulbous plutocrats. Pivoting from social satire to low-life melodrama, the film makes use of bold lighting and meticulous cutting, usually along the lens axis. (Like many European films of the ‘teens, Lucciola lies sort of between tableau cinema and the faster-cut American style.) All in all, a strong, tight movie.

Take Lucciola (1917, right), the story of a waif who befriends a harbor layabout but leaves him to become a society princess admired by a debonair painter and three bulbous plutocrats. Pivoting from social satire to low-life melodrama, the film makes use of bold lighting and meticulous cutting, usually along the lens axis. (Like many European films of the ‘teens, Lucciola lies sort of between tableau cinema and the faster-cut American style.) All in all, a strong, tight movie.

In a similar vein is Addio, Giovenezza! (1918), adapted from a popular song. This one, screened in an open-air venue thanks to an arc-lamp projector, is another sad Genina tale. A careerist law student abandons his rooming-house maid for a social butterfly with a wardrobe to die for. Apart from one startling scene in a milliner’s shop, illuminated mostly by spill from the street, the lighting isn’t as daring as in Lucciola. Still, the poignant plot is again inflected by comic touches, proceeding largely from the hero’s nerdish fellow student. Genina redid the story again in 1927, and I’m hoping to catch that screening.

Malombra (1917), starring the diva Lyda Borelli, was by the great Carmine Gallone. (I’ve discussed La Donna nuda and Maman poupée hereabouts.) After moving into a castle, Marina becomes possessed by the spirit of the woman who died there. Our heroine’s job is to take revenge on the faithless husband. Flirtatious and iron-willed, Borelli dominates her scenes with shifts of stance, sudden freezes, rapid changes of expression, languorous arm movements, and, at one climax, a swift undoing of her hair that lets it all tumble wildly around her face. The print, needless to say, was superb.

In a lighter vein, if you wanted proof of the inventiveness of ‘teens Italian film, you couldn’t do better than Wives and Oranges (Le Mogli e le arance; 1917). This agreeably silly movie sends a bored young man to a spa populated by incredibly aged parents and a bevy of scampering daughters. With an avuncular friend, Marcello capers with the girls before settling on the most modest one as his wife. But her friends aren’t disappointed because our hero’s pals come for a visit and get roped into matrimony too.

Wives and Oranges has a remarkable freedom of narration. The film uses montage sequences with a fluidity that is rare at the time. To convey the boredom of Marcello’s daily routine, a string of quick shots is punctuated by changing clock faces. Later, the idea of finding one’s ideal love mate by matching halves of oranges is presented via an absurd montage of old folks, youngsters, babies, and just abstract hands, all wielding oranges.

Marcello’s paralyzing dilemma of choice is given as a nondiegetic insert of a donkey unable to decide between a hay bale and a bucket of water. These flashy devices keep us interested in a situation that, in script terms, is probably stretched too thin–although when things slow down you can count on the daughters forming a chorus line and zigzagging down the road or popping out from under the dinner table one by one.

Almost as lightweight was The War and Momi’s Dream (La Guerra e il sogno di Momi, 1917), by the great Segundo de Chomón, who moved among France, Spain, and Italy making fantasy films of many types. This one is largely meticulous puppet animation, in which a boy’s toys come to life and enact–at the height of the World War–their own combat.

Trick and Track marshall other toys to play out some seriocomic clashes, including a burning farmhouse and one astonishing shot of an entire town landscape, covered in a long camera movement. Again, there’s no underestimating the sheer technical audacity of Italian cinema of these days.

There’s always an exception, of course. The late David Shepard left us, among much else, Shepard’s Law of Film Survival: The better the print, the worse the movie. A good example is La Tragica fine di Caligula Imperator (1917), signed by Ugo Falena. It’s surprisingly retrograde for an Italian film of the period. Neither the staging (flat, distant) nor the cutting (minimal) nor the lighting (little modeling) is much in tune with contemporary norms. The problem may be the immense sets, which are indeed impressive but which seem to encourage the actors to a hard-sell technique.

The most amped-up is Caligula himself. Playing a mad Roman emperor often tempts any actor to gnaw table legs. But as an example of what a silent film really could look like, Caligula should be required viewing for anybody who sneers at Those Old Movies. If Christopher Nolan saw it, he’d demand to shoot on orthochrome nitrate.

Other 1917 features included The Soldier on Leave, from Hungary, and Stop Shedding Blood!, by the great Russian director Jakov Protazanov. The former was restored from a 17.5mm copy, the latter was missing the two central reels. The Protazanov in particular had some sharp staging in depth and rich sets.

In the same batch was Pola Negri’s screen debut in Bestia (1917, imported to the US as The Polish Dancer). In a fine copy, you could appreciate the bouncy but sultry screen presence that made her a star. And as often happens with films from anywhere in this period, the sets sometimes play peekaboo with the action. Pola, after a night out with her thuggish lover, sneaks back to her bed while her father snores in the background, caught in a slice of space.

Back in the USA

Kid Boots (1917).

The 1917 American entry was a strong, unpretentious Western by Frank Borzage, Until They Get Me. It’s missing some scenes in the middle, but it remains a forcefully quiet movie. The only gunplay takes place at the start, when a man racing to get to his wife in childbirth is forced into a gunfight. He kills the drunkard who provoked it, but by the time he reaches his home, his wife is dead. Now he must flee Selwyn, a mountie. Stealing a horse, he picks up an orphan girl fleeing an oppressive household. The rest of the film will intertwine the fates of the three, leading to a surprisingly civilized resolution.

Borzage is one of the many great directors–De Mille, Dwan, Walsh, Ford, Brown, King, Barker–who started doing features in the mid-teens. Most had long careers. They mastered the emerging norms of Hollywood continuity cinema and learned to deploy them with tact and precision. Just the timing of the reaction shots in Until They Get Me is worth study.

Frank Tuttle started in features a bit later, in 1922, but Kid Boots (1926), my first movie of the Ritrovato, showed complete mastery of comic storytelling. Eddie Cantor, a fired tailor, becomes amanuensis to Tom Sterling, a man-about-town in the throes of a divorce. The twist is that his wife, learning of Tom’s new inheritance, wants to halt the divorce by sharing his bed again. Eddie’s job is to keep the wife and the lawyers at bay until the divorce becomes final. Into this tangle plops perky Clara Bow in her first film after her breakout role in Mantrap (also 1926). You could watch her cock her chin and roll her eyes for hours. She steals the picture from Billie Dove.

The gag situations come thick and fast, with one high point being Eddie’s efforts to get Clara jealous by recruiting a strategically open door to help him pretend that his left arm actually belongs to Tom’s seductive wife. The whole thing culminates in a breathless chase on horses along a treacherous mountain pass. Eddie and all the others keep things lively, and Tuttle’s direction is exacting.

I strayed from the ‘teens again at Dave Kehr’s urging. Of Dave’s magnificent MoMA restorations, I caught William K. Howard’s Sherlock Holmes (1932). Apart from a wild-eyed Ernest Thesiger and an imperturbable Clive Brook, it boasts an abstract opening of silhouettes and confrontational close-ups and a conclusion of percussive flashes as Moriarty’s gang torches its way into a bank.

Ace cinematographer George Barnes had a field day with this one.

That was followed by Tay Garnett’s Destination Unknown (1933), a tense drama of a crisis on a bootlegging ship immobile on a windless sea. Hard, fast playing by Pat O’Brien and Alan Hale was offset by the leisurely presence of none other than Ralph Bellamy, aka Jesus of Nazareth. Don’t ask; just see it.

More from me, and Kristin, later in the week.

Thanks to Guy Borlée for a great deal of assistance on this entry. Thanks as well to the programmers and staff of the festival, especially Gian Luca Farinelli and Mariann Lewinsky.

The Ritrovato site is constantly updated. For our earlier Ritrovato communiqués, go here.

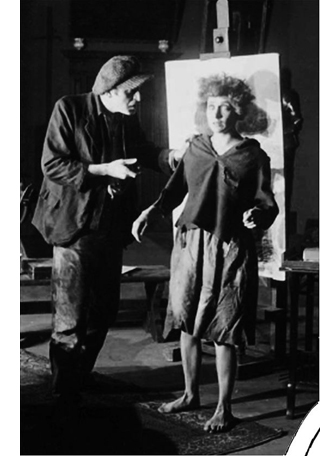

Malombra (1917; production still).

Ladies at all levels

La cigarette (1919)

Kristin here:

Earlier this month Flicker Alley released another of its ambitious collections of historic films, Early Women Filmmakers: An International Anthology. The dual-format edition contains three discs DVDs and three Blu-ray discs. Its ambitions are reflected in part by the volume of material included (652 minutes) and in part by the range of its contents, from well-known classics to obscure titles.

The collection was one of the last projects curated and produced by the late David Shephard. As with many of Flicker Alley’s releases, it was a joint project with Film Preservation Associates (Blackhawk Films) and Lobster Films of Paris, working with several film archives. The films are arranged chronologically, with the earliest being Les chiens savants (1902), a music-hall dog act attributed to Alice Guy Blaché, and the latest Maya Deren’s classic experimental film, Meshes of the Afternoon (1943).

The publicity for the collection emphasizes that “More women worked in film during its first two decades than at any time since” (from the slipcase text). I would be interested in how such a claim was arrived at. It seems unlikely to me, if only because the film industries of the major producing countries have grown enormously since the silent and early sound periods. Still, despite this claim, the notes in the accompanying booklet (written by Kate Saccone, Manager of the Women Film Pioneers Project) describe how the DVD/Blu-ray release “reclaims that stature of ‘woman director’ and celebrates it in all its glory.” (One film included, Discontent [1916], is listed as “by Lois Weber”; in this case she wrote the screenplay, which was directed by Allen Siegler.) Thus the program does not survey the range of filmmaking work women performed–but such a survey would be essentially impossible. The lack of detailed credits on early films makes it difficult to determine even the director of a given film.

The silent films

It is not really possible to discuss all the films, but I’ll mention some and link to earlier entries where we’ve discussed some of them.

Of the 25 titles on the three discs, fourteen are silent. Six of these give an overview of work of Blaché, with three French films and three made after her move to the US.

Lois Weber is represented by three films, starting with perhaps her best-known work, Suspense (1913). With its unusual angles (see above), elaborate split-screen phone conversations, and action shown in the rear-view mirror of a speeding car, this is one of those films you show people to demonstrate how wonderfully inventive directors around the world became in that incredible year. I am also very fond of her feature, The Blot (1921).

The third Weber film, Discontent (1916), may surprise those familiar with her socially conscious features. In the mid-1910s Weber worked in a variety of genres. While David was doing research recently at the Library of Congress, he watched some incomplete or deteriorated Weber films that haven’t been seen widely. He wrote about False Colors here and here. Discontent is a comedy with a moral. An elderly man is living in a home for retirees, but he envies his well-to-do family. Finally they invite him to live with them, and naturally everyone ends up annoyed by the situation–including the protagonist, who winds up returning to the home and his friends.

Mabel Normand apparently directed quite a number of her films for Mack Sennett, and Mabel’s Strange Predicament (1914) is one of them. Its cast also includes Charles Chaplin and was his third film to be released, although it was the second shot and the first one in which he wore a version of his Little Tramp costume. Not surprisingly, he steals every scene he’s in. Normand even plays second fiddle to him, with her character forced for a stretch of the action to hide under a bed, where she is barely visible while Chaplin performs some funny business in the same room. (The print seems to have been assembled from two different copies, the bulk of the film being in mediocre condition with the ending abruptly switching to a much clearer image.)

One curious item in the program is Madeline Brandeis’ The Star Prince (1918). According to her page on the Women Film Pioneer’s Project, Brandeis was a wealthy woman who made films, mainly centering around children, as a hobby. Some of these were apparently intended for educational use. The Star Prince, her first film, is clearly aimed at children. A few of its adult characters are played by young adults, while children play both children and adults. This becomes a bit disconcerting when we assume for a long time that the prince and princess are perhaps seven or eight, until they fall in love and become engaged.

Despite the amateur filmmaking, there are some attempts at superimpositions and other special effects to convey the fantasy, as well as an charmingly clumsy pixillation of a squirrel puppet, the position of which is changed far too much between exposures.

This is the sort of local production, made outside the mainstream industry, that so seldom survives, and it is a welcome balance to the more sophisticated works that make up the bulk of this collection.

Speaking of which, the next part of the program consists of two features by one of the best-known female directors, Germain Dulac. The first, La cigarette, appeared in 1919. It’s melodrama about an fifty-ish Egyptologist, who has just acquired the mummy of a young princess who was unfaithful to her older husband. The professor begins to imagine that he is suffering a similar fate when his young and beautiful wife (see top) begins spending time with an athletic young fellow.

I remember seeing this film nearly forty years ago and thinking it was pretty weak. Luckily I have seen many films from this era since and know better how to watch them. Seeing it again I liked it quite a bit. It’s beautifully shot and well acted, and its sympathetic depiction of the doubting husband and the clever and resourceful wife is more subtle, in my opinion, than that of the marriage in The Smiling Madame Beudet (which is also included in this set). I was glad to have a chance to see the film again and recognize it as being among Dulac’s best work.

The silent section of the program ends with Olga Preobrazhenskaia’s The Peasant Women of Ryazan (1927). The title emphasizes that Preobrazhenskaia’s film is set in a provincial area. Ryazan, the capitol, is about 120 miles southeast of Moscow, so it is not one of the far-flung regions of the USSR. Still, it would have been distant enough at the time to have its own distinctive culture. Peasant Women gives us plenty of local costumes and customs without giving the sense of this being ethnography first and narrative second. Exotic though it may seem to us, this would have been recent history to Russians when it first came out.

Although most synopses claim that the story runs from 1916 to 1918, it actually begins shortly before World War I, probably in 1914, as the heroine Anna marries Ivan in a lively wedding scene including a carriage ride for the bridal couple (below). Shortly thereafter news of the war comes, and Ivan reluctantly departs for to serve in it. Anna is left in the household of her lecherous father-in-law, who rapes and impregnates her. The war goes on and ends, with the Revolution taking place entirely off-screen.

The second woman of the title is Wassilissa, a tougher sort, who applies to convert a decaying local mansion (we are left to assume that it was confiscated in the wake of the Revolution). She is seen at the end as being the prototype of the new Soviet woman, though Preobrazhenskaia throughout avoids hitting us over the head with overt propaganda.

The sound films

Perhaps not surprisingly, most of the directors on the third disc, devoted to sound films, are likely to be more familiar to modern viewers. Nevertheless, Marie-Louise Iribe and her film Le Roi des Aulnes (1920), were completely unknown to me. She was the niece of designer Paul Iribe and worked primarily an actress during the 1920s, and this seems to have been her only solo directorial effort. (IMDb lists her as the co-director of the 1928 version of Hara-Kiri, which she also starred in.)

Le Roi des Aulnes is one of the musically based movies that were popular in the early sound era, being based on both Goethe’s and Schubert’s versions of “Der Erlkönig.” It’s nicely photographed, and the part of the father is played by Otto Gebühr, known for being trapped by his resemblance to Friederick der Grosse into playing that role time after time from 1921 to 1941. He’s predictably excellent here, though the stretching of the short poem into a 45-minute film forces him to register worry and eventually grief throughout. Indeed, despite extrapolated incidents, such as the injury of the father’s horse and the need to procure a new one, a great deal of repetition occurs: lots of riding through marshes and menacing appearances by the Erlkönig, who is portrayed as a large man in chain-mail.

The special effects are the most impressive thing about the film, using double superimpositions in widely different scales, with the giant king holding a small fairy on his palm.

Despite its problems, the film is a valuable addition to our examples of this mildly avant-garde trend that flourished for a short time.

Most of the rest of the directors are well-known and can be mentioned more briefly.

The great animator and innovator of silhouette animation Lotte Reiniger is represented by three short films: Harlequin (1931), The Stolen Heart (1934), and Papageno (1935). I have written about Reiniger’s complex compositions, including her subtly shaded backgrounds. Of the directors represented here, she is the one who enjoyed the longest career, from 1916, when she would have been 17, to 1980, when she was 81. I discuss a BFI boxed set of some of her 1950s films here. I haven’t been able to find a complete filmography, but William Moritz estimates that she made “nearly 70 films.”

Alexandre Alexeieff and Claire Parker’s A Night on Bald Mountain is similarly familiar. Like Iribe’s Le Roi des Aulnes, it falls into the genre of illustrations of existing musical pieces, being an illustration of a piece of the same name by Modest Mussorgsky, as arranged by Nikolay Rimsky-Korsakov. It was created by manipulating hundreds of pins on a large frame called a pinboard, invented by Alexeieff, his first wife Alexandra Grinevsky-Alexeieff (whom he divorced in order to marry Parker in 1940), and Parker. The textured effect is quite unlike that of any other type of animation.

Dorothy Davenport was a prolific actress from 1910 to 1934. She is perhaps most remembered as the widow of Wallace Reid, a star who died from the effects of morphine in 1923. She directed seven films over the next decade, ending with the film in this set, The Woman Condemned (1934), mostly either uncredited or signing herself Mrs. Wallace Reid.

The Woman Condemned is a B picture, produced independently and distributed through the states’ rights system. It’s a competently done murder mystery that gains some interest by withholding a great deal of information from the audience. There are two main female characters, the victim and the accused (seen below in an interrogation scene), and we have very little idea of their motives and goals until the climax of the film. The revelations involve a twist on the same level of groan-worthiness as “and then she woke up.” But again, having a little-known B picture adds to the wide variety of films presented here.

One can hardly study early women directors and skip over the favored documentarist of the Third Reich, Leni Riefenstahl. Day of Freedom (1935) is a good choice for inclusion, occupying only 17 minutes of screen time and amply demonstrating Riefenstahl’s undeniable gift for creating gorgeous images from ominous subjects.

Experimental animator Mary Ellen Bute is represented by two contrasting abstract shorts, the lovely black-and-white ballet of shapes, Parabola (1937) and the vibrant and humorous Spook Sport (1939), the latter (below) made with the collaboration of Norman McLaren.

Dorothy Arzner, the only woman to direct mainstream Hollywood A films from the 1930s to the and 1940s, is introduced via a clip from one of her most famous films, Dance, Girl, Dance (1940). In the scene, Maureen O’Hara’s character interrupts her dance routine to tell off an audience of mostly men who are cat-calling her.

Maya Deren’s first film, Meshes of the Afternoon (1943) ends the program (see bottom). It is a happy choice, since of all the films in the program, it has undoubtedly had the greatest influence on the cinema. Much of the subsequent avant-garde cinema has turned away from music-inspired abstraction and opted for ambiguity, psychological mystery, and impossible time, space, and causality.

Valuable though this collection is, I cannot help but think that some of the directors represented have been oversold. Saccone sums them up:

Together, these 14 early women director have produced bodies of work that are inspiring, controversial, challenging, invigorating, and thought provoking. These women were technically and stylistically innovative, pushing narrative, aesthetic, and genre boundaries.

Surely not all of them meet these criteria. We would hardly expect one hundred per cent of the male directors of the same era to be “technically and stylistically innovative,” so why should we expect all of the work by fourteen varied female directors to be so? Saccone quotes Tami Williams’ book, Germaine Dulac: A Cinema of Sensations. on how the director searched “for new techniques that, in the light of official discourse of governmental and social conservatism, and the modernity of the new medium, were capable of expressing her progressive, antibourgeois, nonconformist, and feminist social vision.” Saccone sees this search in The Smiling Madame Beudet, where “Dulac utilizes cinema-specific techniques such as irises, slow motion, distortion, and superimposition, as well as associative editing, to give visibility to the inner experiences and fantasies of an unhappily married woman …”

Readers might infer that Dulac innovated these techniques. Yet they had already been established as conventions of French Impressionist cinema, notably in Abel Gance’s J’accuse (1919) and La roue (1922) and Marcel L’Herbier’s El Dorado (1921). For example, Dulac surely derived the distorted image of Beudet that conveys his wife’s disgust (below left) from a similar shot of a drunken man in El Dorado (right).

This is not to say Dulac isn’t a fine filmmaker or that she had no new ideas of her own. Only that she didn’t single-handed discover these techniques, but rather she turned the emerging repertoire of Impressionist techniques toward portraying a woman’s experience.

In some cases films that were co-directed by these women are presented as their sole efforts. Lois Weber’s Suspense was directed, as were many of her early shorts, with her husband, Phillips Smalley. Quotations from interviews with both Weber and Smalley make this clear. In 1914, Smalley said of his wife, “She is as much the director and even more the constructor of Rex pictures than I.” “Even more” because Weber often wrote the screenplays for their films and in at least some cases edited them. Weber later described how Smalley worked from her scripts: “Mr. Smalley got my idea. He painted the scenery, played the leading role and helped direct the cameraman.” Directing the cameraman is part of the job of a director.

The list of films in the booklet attributes Night on Bald Mountain entirely to Claire Parker, though on the backs of the disc cases the credit is to Claire Parker and Alexandre Alexeieff. Alexander Hackenschmied (aka Hammid) is not mentioned in the list of films, and the booklet refers to him as having a “close collaboration ” with Deren, even though he and Deren are both listed as directors on the original credits of Meshes of the Afternoon.

Still, if the collection does not make the case that all of the women represented were wildly talented and innovative, it does show the variety of ways in which women managed to work both in and out of the mainstream industry. It’s valuable collection of historical examples and should be welcomed by anyone interested in the silent and early sound eras.

It is worth noting in closing that viewers should not expect all of these films to be presented in the usual beautiful restorations we are used to from Flicker Alley. Some of these films are indeed gorgeous, including the two Mary Ellen Bute shorts, Peasant Women of Ryazan, Day of Freedom, Meshes of the Afternoon, and La cigarette (though the latter has some small stretches of severe nitrate decomposition). Other prints are quite good or at least acceptable. A few of the films simply do not survive in any but battered or faded prints, notably Discontent and The Star Prince. But we are lucky to have them at all.

The quotations from the Smalley and Weber interviews are from Shelley Stamp’s Lois Weber in Early Hollywood (University of California Press, 2015), pp. 26-27.

[May 23] Many thanks to Manfred Polak, who has drawn my attention to a higher estimate of Reiniger’s lifetime production of silhouette films. Her friend and executor, Alfred Happ, put the figure at about 80. The source is an exhibition catalog from the Stadtmuseum Tübingen, which houses Reiniger’s archived material: Lotte Reiniger, Carl Koch, Jean Renoir. Szenen einer Freundschaft. Die gemeinsamen Filme. ed. Heiner Gassen and Claudine Pachnicke (Stadtmuseum Tübingen, 1994).

Carl Koch was Reiniger’s husband and collaborator; Reiniger created an animated sequence for her supporter and friend Jean Renoir’s La Marseillaise. According to Manfred, “Alfred Happ and his wife Helga were Reiniger’s closest friends and caretakers in her last years in Dettenhausen (near Tübingen, Germany). After Reiniger’s death, Alfred Happ was the administrator of her estate. If you ever come to Tübingen, visit the Stadtmuseum (City Museum), where her estate is hosted now. A part of it is shown in a permanent exhibition.” He also provided a link to a touching account of Reiniger’s friendship with the Happs.

Meshes of the Afternoon (1943)

Wayward ways and roads not taken

DB here:

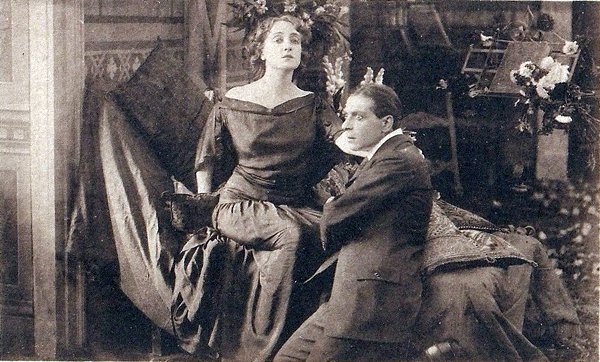

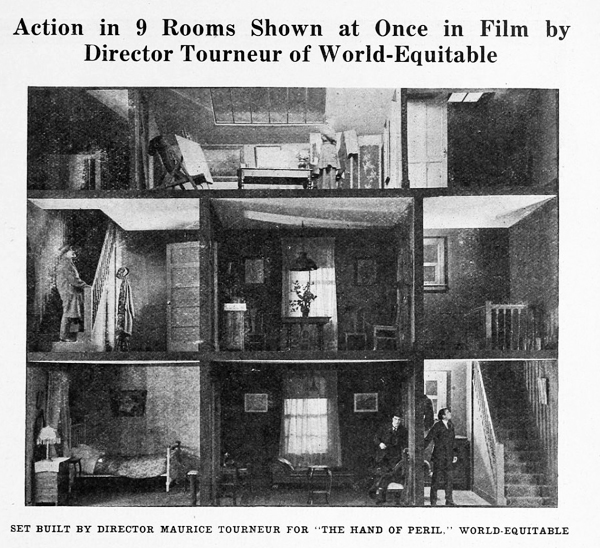

The Hand of Peril (1916) was trumpeted as something new in movie storytelling. It avoided the “cut-back”—that is, crosscutting between different lines of action. In this film, according to the Motion Picture News story above, “nine rooms of a house are shown, with action occurring in each room simultaneously. . . . The action occurring in one room . . . would have to be ‘flashed back’ were the nine rooms not shown.”

Variety found the innovation valuable for pacing. The movie “unfolds in the first four reels with the speed of a race horse. The suspense is constant and there isn’t any let-up whatever until the last few hundred feet.” It’s not clear whether the whole action took place in the house, but for the scenes that did, it appears that the cutaway set served a reference point, a sort of macro-establishing shot. This view gave way to cut-in closer views of the scenes in specific rooms.

Another trade journal noted: “The experiment is quite novel and attractive and fits in admirably in the story, but if it will prove of general worth cannot be told yet.” Now we can tell. This was a road not taken. Crosscutting remained in force, being far more cheap and flexible than dollhouse sets.

No copies of The Hand of Peril are known to have survived. Yet the fact that it was made suggests just how energetic the 1910s were in raising striking creative possibilities—some of which became conventional, some of which fell by the wayside. Seeing this sifting and winnowing at work was a constant delight during my recent stay in the Kluge Center at the Library of Congress. Watching nearly a hundred American features from 1914-1918 drove home to me how excitingly strange movies can sometimes be.

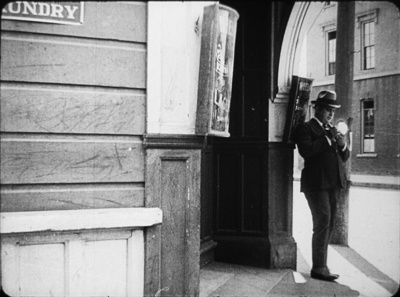

On the one hand, the conformist side of the films was there in abundance. Most of what I encountered were variants of an emerging “classical Hollywood cinema,” as they (we) say. Some efforts were crude, some smooth, but you could tell what the filmmakers were going for, and it was a thrill to see obscure films effortlessly exploiting schemas that would become central to our films. What a kick to see, in The Sign of the Spade (1916), a detective using a hand mirror to trail a suspect, with beautiful control of POV, frame composition, and rack-focus.

Hitchcock, eat your heart out. Well, wait until you start making films.

Yet looking for norms sensitized me to non-normative things—not merely clumsy efforts, but genuine attempts to try something different. Different and, to our eyes, often odd. American features of the 1910s include cuts and framings and camera moves and lighting choices and performance bits that no one now could imagine using.

My viewing companion James Cutting compared the week’s worth of films he saw to the Cambrian explosion in evolution, a period where all manner of organisms burst forth in profusion—before selection pressures wiped many out. While filmmakers were mastering classical plotting and continuity style, lots of other stuff was going on.

Have a look. Actually, several looks.

Widescreen, no. Tallscreen, yes.

Ready Money (1914).

In this shot, the story action is taking place at the nightclub table, but the society types gathered there are overwhelmed by all the hubbub around and above them. And we aren’t given closer views to help us sort it all out.

In all periods of film history, directors usually tried to center the action. Yet in early years, they sometimes favored framings that would today be considered strangely decentered. One of my favorite tactics from the ‘teens involves putting important elements in the bottom of the frame, notably in extreme long shots. In The Spoilers (1914), Cherry flops back in her saddle when she sees the devastated mining camp.

At the big reception in The Sowers (1916), a modern director would have put Paul and the dignitaries he greets in the foreground, and let Princess Tanya descend in the distance. But William C. de Mille creates a vast vertical composition, setting Paul in his braided uniform in the lower third of the frame and putting Tanya far back on the staircase.

Such top-heavy shots look odd to us, but they have a sort of grandeur, and the taste for them can be acquired. You can see a more intimate example in the fine recent release of Thanhouser films restored by the Library of Congress. The opening sequence of The Picture of Dorian Gray (1915) shows Dorian at the theatre, in a box in the foreground with Romeo and Juliet playing onstage behind him.

Even in the teens, I think this is an outlier. Most theatre scenes are handled with cutting to reverse angles of the audience and the onstage players. When there’s a box in the foreground, it’s usually anchored as such, as in Feuillade’s Fantômas (1913) or Willliam Wauer’s Der Tunnel (1915).

The strange symmetry of the Dorian Gray composition, aided by putting Dorian’s head along the vertical axis rather than off to the side, and by putting the object of his attention, the actress, directly above him, is really startling. The all-over quality of these compositions usefully remind us that every inch of frame space is there to be used if you have the imagination. We’ll see this hypersaturation of the frame in some later examples, but eventually the tactic would go away. Shots would put the human figures in the center of the format, or in long shots place them gracefully on foreground right or left.

Scene + insert

Both European and American directors of the 1910s employed what I’ve called the tableau approach. Within a fixed camera setup and fairly distant framing, the viewer’s attention is controlled through staging, either lateral or in depth. I’ve given plenty of examples elsewhere of how flexible and precise this style can be. A beautiful example occurs in Lois Weber’s False Colours, which I’ve already analyzed along these lines.

During the years I examined, directors were already discarding this approach in favor of cutting-based ways of guiding our eye. Some freely put the camera at various points around a set or an outdoor scene. (In all national cinemas of the period, we find more variety of camera placement on location than in sets, for obvious reasons.) More common was the tendency toward what was called the “scene-insert” method. A master shot of middle range (the “scene”) would be followed by a closer view of something within that space (the “insert”). Very often that cut would be an axial one—that is, a setup straight along the camera axis. Although sometimes decried as a mistake, the axial cut has been used by filmmakers of all eras.

The corn-husking bee in The Hoosier Schoolmaster (1914) illustrates how a basic tactic of the tableau style may be integrated with the scene-insert method. The new schoolteacher is boarding with Mrs. Means, who’s trying to get him to marry her daughter. As the community gathers (that corn won’t husk itself), Mrs. Means forces her daughter on him. The teacher, though, is more attracted to the demure town outcast Hannah. First, Mrs. Means stands behind the schoolmaster and her daughter. Back to us, she addresses the hayseeds.

She moves away to show Hannah in the background. In the tableau approach, this blocking-and-revealing action is usually repeated throughout the shot, but here it’s a one-off device. As soon as it happens, the schoolmaster turns to look back.

Now comes an axial cut to Hannah in the background.

Simple and efficient, this is a good example of the scene-insert method, here enabled by a bit of depth staging. Later stretches of the scene will use the blocking-and-revealing tactic in conjunction with further axial editing.

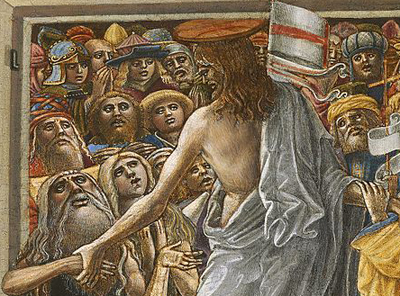

Sometimes the “insert” phase takes a turn that doesn’t look so simple. Consider this shot from The Spoilers (1914). In another wildly decentered framing, the hero Roy Glenister has jumped down from a balcony (upper right) to land on the floor of a big dance hall as seedy as anything in Deadwood. He lands and faces the crowd in the far distance, while the foreground area of gamblers clears away in a panic, so we can see him a bit better.

This is a very distant framing, so we get an axial cut in to him crouching before the surly crowd.

This is a striking insert because in order to give a sense of the massed crowd Roy faces, the director has apparently stacked people up—by height, and perhaps on risers of some sort—so that a welter of faces appear piled up against him. The showgirls at the very top of the frame are on the stage, but the people in the middle were on the same floor as Roy in the master shot. The technique is reminiscent of the stacking of crowds we find in classic Western painting. Here’s a detail from one of the weirdest pictures I saw in the National Gallery, Christ in Limbo by Benvenuto di Giovanni (ca. 1436).

Later filmmakers would presumably have used a high angle to let us see the faces; but then we’d lose the looming effect of Roy’s back in the foreground. Artistic choices are always trade-offs, and here, for the sake of a strong expressive effect, director Colin Campbell has sacrificed spatial realism in a way that probably wouldn’t occur to a contemporary filmmaker.

The shift from long shot to a closer view here is pretty extreme. At several points in my viewing I noticed that when using the scene-insert method, filmmakers often didn’t try for a smooth gradation of shot scales. The old triumvirate long shot/ medium shot/ close-up aims to lead the viewer gradually to the heart of the action, but in the 1910s directors seemed almost impatient to get to the meat of things.

So, for instance, in William Desmond Taylor’s Pasquale (1916), the good-hearted hero is trying to keep up appearances at the wedding of the woman he loves. We get a cut from a very long shot to a tight close-up, accentuated by the vignetting that isolates Pasquale’s face. No medium-shot eases the transition.

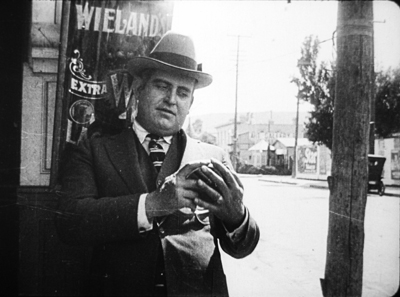

For modern audiences, I think this is a bit of a bump–but nothing compared to the scene-insert leap we get in Vanity Fair (1915). In what is everybody’s idea of what those old movies look like, Becky is exploring the parlor. It’s a very distant shot, atypical for an interior of this scale. And the abrupt jump to a very close insert shows not Becky but the photograph she studies.

This is quite odd. Even stranger, the camera stays back from Becky throughout the film.

It’s unusual for an American movie of 1915 to avoid inserts, especially since Becky is played by the famous Minnie Maddern Fiske, who had popularized the part on stage. Where are the star close-ups, as in Pasquale? Are we dealing with simple incompetence? Apparently not, Variety suggests.

This seems plausible. By shooting most scenes in anachronistic long shots, the director could play down the fifty-something performer portraying a young girl. In the process he could associate the classic story with pre-teens photodramas, which seldom used close-ups. This deliberate anachronism suggests that filmmakers were already aware of the choices of shot scale they now had, and what the scene-insert method committed them to.

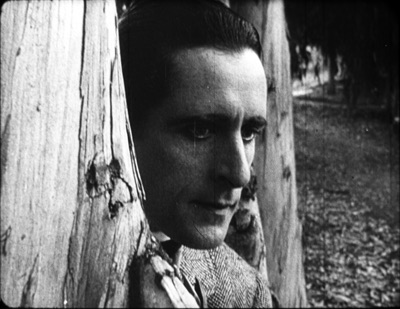

What survives of Weber’s marvelous False Colours offers a great many lessons in the range of 1910s techniques, but one sequence flaunts the all-over long shot and the jolting insert. The conman Bert has persuaded his wife Flo to pose as the missing daughter of the wealthy actor Lloyd Phillips. In this scene, Flo and Phillips have retreated to a park bench to get better acquainted. Bert hides behind a tree to watch them.

This is a pretty standard situation, but it’s handled in an eccentric way. As the couple sit in awkward silence on the bench, in the far left background Bert creeps in. Problem is, you can barely see him: only his hand, on the far, far left center, is visible in silhouette as it approaches the tree, followed by a dark blot. Thanks to Photoshop, I give you the insert that Weber denies us.

Who would see this? Maybe a viewer from the time, trained in different viewing skills–someone used to the frame’s being packed full? I consider this possibility in an older entry. And there’s certainly a slice of light space left vacant to allow for the hand, creating an extreme case of aperture framing. Anyhow, Weber then does what Taylor did with Pasquale. She cuts from the fairly distant shot to a big close-up of Bert peering out from the tree.

Compared to the bare hint of his arrival with the fugitive hand, this strenuous shot is overcompensation. All we needed was a sort of medium shot of him listening, preferably with the couple in the foreground to orient us. That shot comes, but again in an eccentric way. At first, Phillips blocks our view of Bert, so the actor in the rear has to raise his head–creating the impression of floating just above Phillips’ hat. Again, I supply a blow-up.

And when Flo, lying, says in a dialogue title that her mother talks of Phillips constantly, Bert’s head jerks up angrily. He’s still stuck atop Phillips’ hat. Another huge close-up reinforces his reaction.

Maybe it’s all a mistake? Did Weber screw up a simple scene? Why not just settle Flo and Phillips a little more to the right on the bench, leaving plenty of space on the distant left for Bert to creep behind the tree and peer out, perfectly visible to us throughout? Then, if you insist, you could have the big close-ups of Bert’s reaction? Or did the DP not allow for Phillips’ blocking Bert? (Remember, they didn’t have reflex viewing back then; the viewfinder didn’t show exactly what the lens took in.)

I can’t say. Maybe this is bold, maybe just a botch. But scenes like this in False Colours demonstrate the far-reaching possibilities that people were trying out in the Cambrian explosion of film style.

Jam sessions

Liberty Belles (1914).

In Ready Money, The Spoilers, and other instances we’ve already seen a penchant for stuffing the frame with figures, props, and items of setting. People at the time apparently noticed it too. Charlie Keil, in his indispensable survey of film style from 1907-1913, writes:

Critics advised against “crowded groupings” for numerous reasons: first, if a massing of characters seemed unnaturally pressed together, it would expose the limits of the shooting conditions and destroy the illusionism that cinema was meant to sustain; second, such unnatural staging would violate the standard of composition derived primary from photography, which stressed balance and order; and third, overly compressed staging might obscure the central narrative action and create problems of comprehension for the viewer.

Widescreen, as I’ve mentioned before, poses problems. How do you fit in the human body? How do you fill up the lateral expanse, or do you leave it empty? The squarer rectangle of the 1.33 (or even narrower) frame of early cinema allowed bodies to be packed in, and we’ve seen a surprising vertical dimension to the compositions. Filmmakers found ingenious ways to jam in their figures, especially when they began moving them closer to the camera. By 1914, with the “American foreground,” the front line of action might get pretty crowded.

The climax of Kindling (1915) shows that Cecil B. DeMille was no slouch at filling up the midshot space and then developing the scene through small gestures and changes of posture. It’s far too long for me to run through here, but I think you get the idea.

The blocking and revealing, the slight changes that hide or unmask someone behind someone else, the tendency for actors to freeze so that one performer’s movement draws our eye: all these tactics of long-shot tableau staging are played out in small compass. Call it a jam session.

Cecil’s brother William followed suit in a film of the following year, The Heir to the Hoorah (1916). This comedy of class differences centers on three newly rich gold miners, all bachelors. The roughnecks Bud and Bill urge Joe to marry Geraldine so that there will be an heir to their fortunes. Geraldine’s mother, Mrs. Kent, invites the men to a dinner with her swanky friends. For once, the rich folks aren’t snobs but are good-natured folks–and they have to be, for the clumsy ways of Bud and Bill would outrage anyone less tolerant.

William C. de Mille often avoided long shots and instead covered scenes in fairly tight medium shots and plans américains. Just before the guests go into dinner, they’re huddled together in just such a composition. On the left, Bud is chatting with Joe and a fancy lady. On the right, Geraldine and her mother watch. Behind them are the lady’s husband and Bill. At first the action is on the right, as Mrs. Kent frets about the deplorables Geraldine has brought into the house.

Faces now get diced and sliced, masked and shifted. The gag is set up by servants emerging out of distant darkness. A small aperture opens up so we can see Bud and the others on the left picking up their drinks from a tray.

The insert is a surprisingly tight long-lens shot of the group on the left, though with others hovering around the right frame edge. Drinks are taken, a toast proposed.

And Bud proceeds to spill his drink on the lady, who responds without rancor.

Another insert shows a reaction shot of Bill and the lady’s husband, also unflapped, before cutting back to the full “scene.” By now, with waiters coming out from behind foreground figures, there are nine characters crammed into the shot.

There’s more to come when Bud’s spur gets caught in the lady’s gown, but you get the idea. Axial cuts carve into this mob and shove bits and pieces of faces, bodies, and gestures out at us. The principles of tableau staging are squeezed down into medium shots. William C. de Mille was a pioneer of multiple-camera shooting for ordinary scenes, and he may well have used a separate camera for the long-lens shots (even though the position of Geraldine on the right is wildly cheated between shots 2 and 3 and 3 and 4).

Later Hollywood filmmakers would favor much cleaner images of groups, with heads evenly spaced out across the frame. But visual artists had long explored the bunched-faces option. Here, for instance, is Degas’ daringly unbalanced and crowded Pauline et Virginie of 1876.

Yet these somewhat wild experiments weren’t dead ends. They remained artistic possibilities to be explored more, when other filmmakers hit upon them. Altman’s and Jancsó’s crowded telephoto shots revive the packed frames we see in the 1910s, and other filmmakers found artistic rewards in fanning out figures as in the lovely frame above from Liberty Belles. Those cute girls come back to life in Hou’s Cute Girl (1981) and Millennium Mambo (2001).

Even The Hand of Peril‘s dollhouse set didn’t go absolutely extinct, as admirers of Jerry Lewis (The Lady’s Man), Godard (Tout va bien), and Wes Anderson (The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou) know. Film style, it seems, knows few dead ends, only detours.

There’s a tendency to think that the history of style constitutes an ever-expanding menu of options. Today, you can cut the way Griffith or Eisenstein or Godard did, right? A similar case has been made for technological change. For decades it was much harder to make a color film than a black-and-white one, but now filmmakers can pursue either option. Most filmmakers in the silent era couldn’t make a talkie, but today’s filmmakers can go silent if they want.

Yet it’s proven surprisingly hard to make a contemporary film look and sound like one from an earlier era. On the sheerly technological front, it’s not easy to recapture the tonal range of orthochromatic nitrate, or the sound texture of early talkies, or the saturation of Technicolor. As for style—how you stage, how you cut, how you frame, and so on—again certain things are hard to recapture. It seems that certain stylistic possibilities, like purely technological ones, have been taken off the menu.

Why is style so hard to recapture? Some elusive nuances of lighting and color depend on technological factors we can’t recreate. IB Tech can’t easily be mimicked with a dropdown menu. On other dimensions, the range of creative options in earlier eras just doesn’t come easily to today’s filmmakers. But maybe by looking at those films we can reconstruct that range. We might also encourage filmmakers to take the sort of chances people did at the very beginning of what we have come to call Hollywood.

This is, I think, my last post for a while on my 1910s adventures at the Library of Congress. I must move on to other projects. As ever, I’m tremendously grateful to the John W. Kluge Center, and particularly its director Ted Widmer, for enabling me to conduct this research under its auspices. A special thanks to Mike Mashon of the Motion Picture Division, and all the colleagues who have been helping me in the Motion Picture and Television Reading Room: Karen Fishman, Alan Gevinson, Rosemary Hanes, Dorinda Hartmann, Zoran Sinobad, and Josie Walters-Johnston. Thanks as well to James Cutting for enjoyable discussion as we watched old movies together.

The new collection of Thanhouser films that includes The Picture of Dorian Gray also provides an enjoyable tour of the LoC Culpeper facility I blogged about in the spring.

I’m grateful to Charlie Keil for ideas and help with sources. The passage I’ve cited from him is in Early American Cinema in Transition: Story, Style, and Filmmaking, 1907-1913 (University of Wisconsin Press, 2001), 134-135.

The quotations from Variety come from anonymous reviews of The Hand of Peril (24 March 1916), 24, and Vanity Fair (29 October 1915), 22.

Other entries about my DC viewing are Anybody but Griffith, Movies in the mountain, and on the machine, Film noir, a hundred years ago, and When we dead awaken: William Desmond Taylor made movies too. More generally, see the category of entries on Tableau staging and my books On the History of Film Style and Figures Traced in Light: On Cinematic Staging. The relation of the tableau style to Hou’s work is considered in the latter, as well as here.

On the difficulty of replicating older film styles, see our blog entries on The Good German and forging a film.

Building the set for The Life Aquatic (Wes Anderson, 2004).