Archive for the 'Sometimes . . .' Category

Sometimes a swordfight . . .

The Valiant Ones (Zhonglie tu, 1975).

DB here:

. . . makes you sit up. And notice a simple but ingenious cinematic technique.

One of the refrains of this blog is: We want to know filmmakers’ secrets, even the secrets they don’t know they know.

Over my years of studying Hong Kong film, I kept coming back to the work of King Hu (Hu Jingquan), one of the great directors of Chinese cinema. Most famous for A Touch of Zen (1971), Hu made several other striking martial arts films: Come Drink with Me (1966), Dragon Inn (aka Dragon Gate Inn, 1967), The Fate of Lee Khan (1973), and Raining in the Mountain (1979).

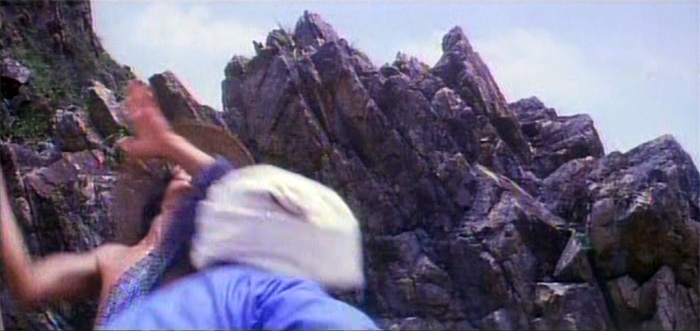

Kristin and I have a special fondness for The Valiant Ones (1975), which consists largely of virtuoso combat sequences. Here we find some of Hu’s most spectacular experiments in staging, framing, and cutting action scenes. The story isn’t complicated, but the result lives up to his motto: “If the plots are simple, the stylistic delivery will be even richer.” Unhappily, for reasons of rights, The Valiant Ones is harder to see than his other masterworks.

When I was studying Hu’s work at a European archive, I told the archivist that watching The Valiant Ones I had started to understand his secrets. She smiled and said, “All right, but don’t tell anyone.” Ha! Fat chance. I broke the news in an article and then in Planet Hong Kong. I use our current lockdown to share it more widely.

Suppose you have a character called the Whirlwind Swordsman. He circles his adversary so quickly, ducking and bobbing, shifting front and back, that the target is bewildered. How would you render this quicker-than-the eye tactic on film? Today’s directors think automatically of digital effects. But that wasn’t on the menu in 1975.

Wu Jiayun and his wife are pretending to be interested in joining a pirate gang. In a series of audition bouts, the chief pirate sends his minions to spar with them. Here we see first Wu’s wife take up a monk’s archery challenge. (I include that as bonus material.) It’s a fair sample of the rhythm Hu gets through a combination of editing and figure movement. The audition continues with Wu showing a stout pirate his Whirlwind technique.

Did you see what King Hu did? He used a double for Wu, dressed him in white, and had him rocket into and out of the foreground while the primary Wu dodged in and out of frame in the background. Sometimes Wu leaves one spot and reappears elsewhere only one frame later!

Significantly, Hu set up this cleverly confined framing by means of a simple axial match-on-action. The larger view oriented us to the area clearly.

Giving up his fondness for discontinuous cuts, Hu used this cut to prime us to expect continuity of space as the shot unfolds. The double is in effect inserted in the splice.

Is it merely a trick? All’s fair in cinema. The gliding, percussive force of the frame entrances and exits shows us a preternaturally gifted fighter whose moves are too fast for the naked eye. We have no time to reflect on how it was done.

Interestingly, Wu seems to have taught Mrs. Wu his technique. At the climax she gets a chance to practice surrounding a hapless fighter. See my stills up top and at the bottom.

Secrets? You bet. We appreciate them all the more when we work to discover them.

For more on King Hu, see Stephen Teo, Chinese Martial Arts Cinema: The Wuxia Tradition (Edinburgh University Press, 2009). I discuss Hu’s style in more detail in “Richness through Imperfection: King Hu and the Glimpse” in Poetics of Cinema, and in “Three Martial Masters” in Planet Hong Kong, 2d. ed.

A Touch of Zen and Dragon Inn are available in fine restorations in the Criterion Collection and on the Criterion Channel. Also on the Channel is Hubert Niogret’s superb biographical film about King Hu.

Some recent entries (here and here) review the ideas of axial cutting and matches on action.

This is the second time I’ve used King Hu in this series; he’s a rich source of startling cinema. For other “Sometimes…” entries, go here.

The Valiant Ones (1975).

Sometimes an actor’s back…

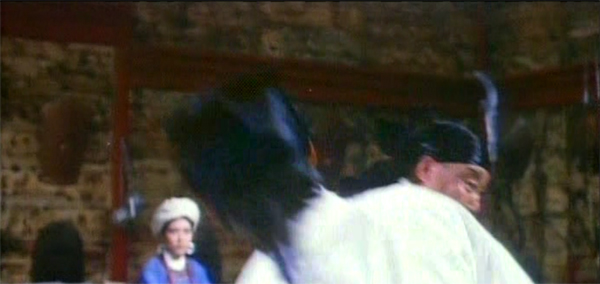

Il Maschera e il Volto (1919).

…can crisply punctuate a scene.

DB here:

One of the 1919 films on display at Cinema Ritrovato this year was Augusto Genina’s Il Maschera e il Volto (The Mask and the Face, 1919). It’s drawn from a popular play that satirized the erotic stratagems of the elite. The movie begins by introducing a gaggle of couples at a Lake Como house party, so I expected that it would create interlocking intrigues in the manner of silent-era Lubitsch films like The Marriage Circle (1924). Not so: the plot concentrates on one romantic triangle. The version we have, at 1799 meters, might be a little shorter than the original (said to be around 1900 meters), but it seems likely that the plot we have dominated the initial release too.

Savina is betraying her husband Paolo with the family lawyer Luciano. During the house party Paolo declares that a cuckolded husband has every right to murder the unfaithful wife. When he learns of Savina’s affair (but not Luciano’s complicity), he orders her to leave the household immediately. Paolo declares that she will become dead to him and their friends.

Paolo tells Luciano that he killed Savina. We get a lying flashback (yep, already and again) that shows him strangling her and dumping her body in the lake. Savina overhears his false confession. When she hears Luciano asserts that she got what she deserved, she realizes he’s worthless. Disillusioned about both of the men in her life, she follows Paolo’s order and leaves their estate.

Of course a woman’s corpse, face mutilated, is soon found in the lake. Now Paolo must stand trial for Savina’s murder, and Luciano must defend him.

Not the funniest comedy I ever saw, but it has a grim charm. One particular scene made me happy.

Piano ensemble

Readers of this blog know that I like to study staging in 1910s films, and Genina provided nifty examples in the 2017 Ritrovato season. Like the Lupu Pick film I reviewed at this year’s jamboree, Il Maschera lies stylistically midway between pure tableau cinema and editing-driven construction. Interior scenes are often broken up by many cuts, but they’re typically axial, straight-in and straight-back, without reverse angles. (The exception is the trial scene. As in many 1910s films, it creates a more immersive space through “all-over” cutting.) In most scenes, the shots enlarge actors to follow their responses, but we don’t get setups that penetrate the space, putting us inside the flow of action.

Still, axial cuts, as Eisenstein and Kurosawa and John McTiernan knew, have a peculiar power. They can be abrupt and punchy, or more subtle in readjusting the framings. The latter option is on display in the film’s first big scene, when all the guests gather in the salon around the piano.

The scene runs about two and half minutes and consists of twelve shots and six dialogue titles. What’s worth noticing is the slight variations in setups, coordinated with what Charles Barr has felicitously called “gradation of emphasis.” Often the changing setups are masked by an inserted dialogue title, so there are no bumps in continuity.

The orienting view is a bustling shot that piles up faces and shoulders along the horizontal axis.

In an axial cut-in, the guests debate the righteousness of Othello’s murder of Desdemona. A further cut-in shows Luciano and Savina on the far right sharing glances. (The curly-haired woman will prove an innocent witness.) It’s a Hitchcockian situation, but without the POV singles.

Soon an older husband rises from his chair in the rear (another cut-in, “through” the group) and comes forward to join them. He draws alongside the husband to calm him down.

I’ve talked about crowded tableaus like this before. The Americans I survey were somewhat bolder than Genina in jamming the heads even closer together, creating partial faces that float out of the background. Genina has, however, other goals in view.

The woman in white

During the cut-ins, Genina takes the opportunity to rearrange the actors around the piano and re-scale his shots. There are five distinct variants of the piano grouping; even setups that might seem the same aren’t quite. There are two setups of the adulterous couple. All these are calibrated to suit the action presented.

For instance, when Paolo launches his rant about unfaithful women, the framing is tighter to favor him, and the foreground woman in white is primed for her big moment.

Similarly, the second cut to the adulterous couple is framed somewhat differently from the earlier one (on left), with Luciano pushing aside the cute curlyhead. He and Savina are listening more intently to Paolo’s denunciation of faithless wives.

So what seem to be fairly straightforward repetitions of setups are in fact minutely adjusted to favor certain actions. This strategy allows Genina to return to the whole ensemble.

In a closer view, the woman in white suggests that they stop arguing about infidelity and go in to play cards. She rises, blotting out Paolo in mid-rant.

The effect would be less pointed if she were in black like the other women.

Everyone but the older husband turns away, and people retire to the next room in the distance. They drain the space like water emptying out of a tub. That leaves what filmmakers today would call the scene’s button: the old man noticing that Luciano and Savina don’t join the group. Throughout the scene they’ve been literally marginalized on the far right.

It’s through this older man we just barely see the couple leave. He seems to understand the game they’re playing. and now he watches them disappear, perhaps to a private rendezvous.

The scene ends with another turning from the camera, another actor’s back letting us know the action is done.

Very often, turning from the camera signals the end of scenes, and of films.

It would have been fairly easy for any director to simply let the actors clustered around Paolo drag him off to play cards. But by having the woman in the foreground pop up, cut off our view of Paolo, and trigger a general exit Genina makes the action taper off briskly. Staging in the silent cinema is full of such little felicities, and it’s one job of criticism to appreciate them. It’s especially important since such techniques seem no longer part of filmmakers’ skill sets.

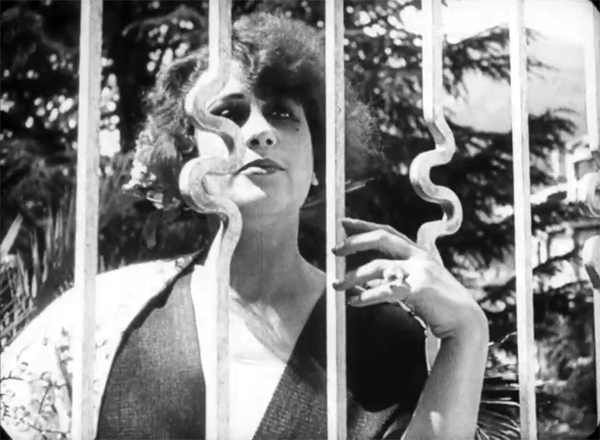

Then again, some Maschera images just whack you in the eye. Who doesn’t sense passion, elaborately caged, in the image below?

Thanks as usual to the Cinema Ritrovato Directors: Cecilia Cenciarelli, Gian Luca Farinelli, Ehsan Khoshbakht, Mariann Lewinsky, and their colleagues. We particularly owe Mariann for her curating of the Hundred Years Ago series every year. Special thanks as well to Guy Borlée, the Festival Coordinator.

Information about La maschera e il volto can be found in Vittorio Martinelli’s Il Cinema Muto Italiano: I film del dopogerra/1919 (Rome: Bianco et nero, 1960), 170-172.

Other Sometimes... entries consider a single axial cut, a shot in depth, a jump cut, a reframing, and a production still.

Il Maschera e il Volto (1919).

Sometimes a production still…

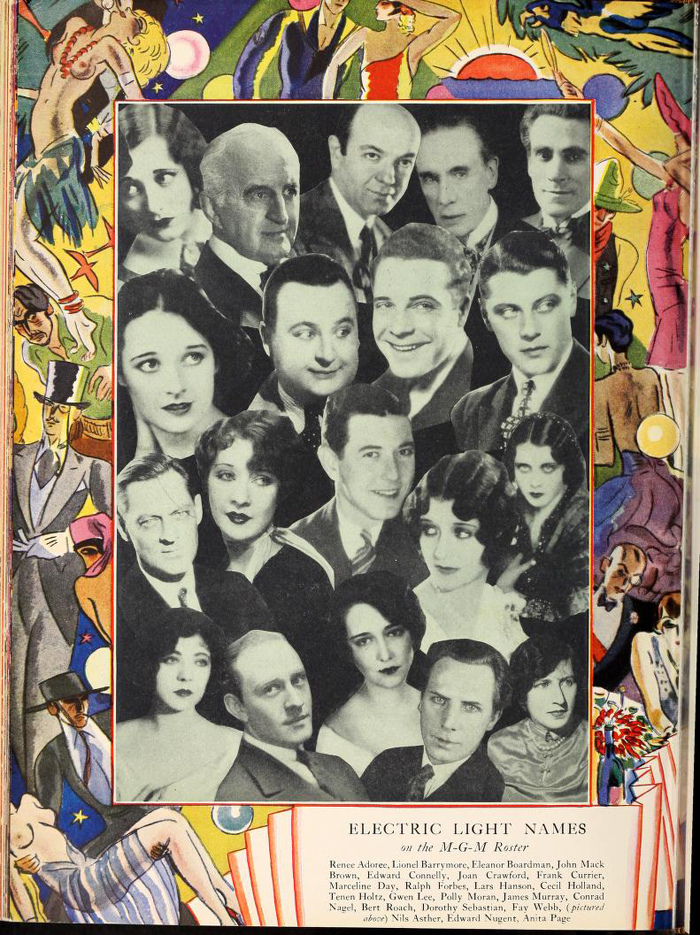

Frisco Sally Levy (MGM, 1927; dir. William Beaudine).

….makes you say, Jeepers.

Henry Sapoznik is an outstanding performer and producer of music, a many-times Grammy nominee, and my colleague here at UW, where he heads the Mayrent Institute for Yiddish Culture. He’s also the grand-nephew of character actor Tenen Holtz. When Henry showed me this still from his collection, it gave me a buzz in many ways. Let me count them.

The Buzz Topical. Open-carry at the family table. It’s not just for breakfast any more. Joey, do you like movies with guns?

The Buzz Narrative. Here’s the plot, courtesy of the American Film Institute:

Sally Colleen Lapidowitz, the daughter of an orthodox Jewish father and an intensely Irish mother, is the steady girl of Patrick Sweeney, a motorcycle cop. Sally becomes infatuated with Stuart Gold, a Jewish dandy, who, though he is approved by her father, soon proves himself to be a worthless cad. Patrick rescues her from the dandy, and all ends happily in the Hebrew-Irish family.

Alas, no mention of this intimate scene.

The Buzz Ethnic-Shtick. Frisco Sally Levy belongs to a cycle of comedies centering on Irish and Jewish families. The most famous are Abie’s Irish Rose (stage play, 1922; film, 1928) and The Cohens and the Kellys (1926 film). Variety thought the movie a hoot, “averaging a dozen laughs to the minute.” Special praise was reserved for the Lapidowitz boys: “as a team of juvenile comedians these two youngsters are unsurpassed.”

Then there’s the gag involving a St. Patrick’s Day parade, evidently in a color sequence. Ma and Pa call out from the sidewalk, “Hello, Pat!” “And immediately every one of the carefully tailored, frock-coated, top-hatted gentlemen turn about with military precision and raise their hats in unison.” “Then,” the critic adds, “there are laughs with the close-ups of an ambulance and a German band leading the Irish patriots.” We’re told that Tenen Holtz puts across his role of paterfamilias well, rising above the caricatured Jewish tailor, which is all too often “obnoxious if over-drawn and too Jewish for comfort.” Ouch.

The Buzz Compositional: Would that today’s production stills were as nifty. The grouping, the eyelines, and Patrick’s gesture all drive our attention to the pistol. But space is left for us to notice Sally’s fixed stare at Patrick (mute devotion? apprehension at the gunplay?). And there are centrifugal attractions. There’s the younger daughter with her head slumped in her plate. Scared? Asleep? Bored? Sick? Doped? And of course the pooch, intent on table scraps, is missing the point. Nice apartment too, with both a phone and a writing desk. A symmetrical room for a symmetrical shot.

Alas, the film has not yet been found (a nice way of saying “lost”). Is there a collector out there with a copy? In the meantime, with stills like these we can make up our own stories.

Thanks to Henry for the still and permission to post it. The review is “Frisco Sally Levy,” Variety (13 April 1927), 13. See also “‘Sally Levy’ Takes Frisco for $26,200,” Variety (27 April 1927), 7.

Other entries in the “Sometimes…” series are: “Sometimes a shot . . .” and “Sometimes two shots . . .” and “Sometimes a jump cut…” and “Sometimes a reframing…”

Exhibitors Herald and Moving Picture World (12 May 1928).

Sometimes a reframing…

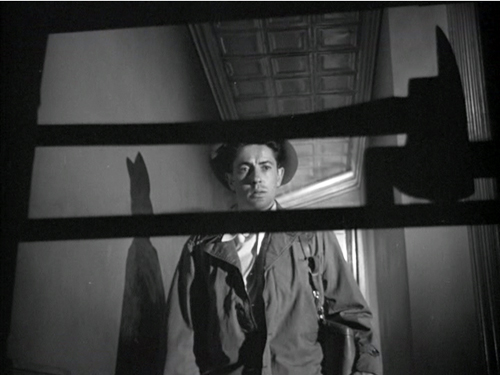

Side Street (1949).

DB here:

…just knocks you out.

“It can only be fully recommended to those who have a deep and morbid interest in crime.” Snooty judgments like this made Bosley Crowther the critical joke of generations. Today film lovers wear their deep and morbid interest in crime as a badge of honor. Especially when the crime is covered by Anthony Mann.

In Side Street (1949), Joe Norson has lost his business and works part-time as a postman while he and his wife await their first child. Having come back from war and wanting to give Ellen a good life, Joe is tempted to steal money he’s seen lying around the office of a crooked attorney. He grabs a folder containing what he thinks is a couple of hundred dollars; instead, it holds $30,000 of blackmail money. The woman who chiseled the money out of a businessman turns up dead, and the police are investigating. When Joe naively loses the money and sets out to recover it, he’s drawn into the murder, tracked by the gang, and targeted as a prime suspect by the police.

Variety and Crowther chided the screenwriters for a sketchy plot, and the complaint is somewhat fair. Joe is an unusually weak protagonist. He botches both his theft and his cover-up, leaving a trail that’s easy for the killer and the cops to trace. Because Joe is fairly passive and on the run, and he has to follow his clues in a fairly linear manner, and his schemes to fight back come to almost nothing, the action is filled out by scenes of the gang and the police tracking him.

What partly compensates for the plot’s problems is the bold location shooting. As part of the semi-documentary trend of the period (the film opens and closes with worldly-wise voice-over narration from the Homicide Captain), Side Street presents itself as a story rooted in urban reality. And indeed it is a triumph of location shooting. The characters visit a bank, Greenwich Village, Bellevue Hospital, and many neighborhoods. The final chase, with Joe trapped in a taxi with the killer and pursued by three cop cars, is a tour de force of geometrical shot designs that make city canyons part of the drama.

Mann has long been praised for integrating the forces of nature into the action of his Westerns, but this film shows his flair for cityscapes too.

Given the constraints of location filming, the freedom of Mann’s camera is all the more arresting. This time he’s not working with John Alton, the cinematographer most in tune with his baroque sense of light and framing. But Mann still gets punchy results from ace DP Joseph Ruttenberg. There is nothing quite so staggering as Alton’s framing of Claire Trevor and the cabin clock in Raw Deal, let alone the Grand Guignol imagery of Reign of Terror, but Ruttenberg does give us plenty of nicely dense compositions, exploiting the verticals and apertures available on location. There’s also a neatly discreet shot of a revolver peeking out from behind a door in distant long-shot; the shadow supplies the telltale shape.

Mann is a post-Kane filmmaker. Like nearly every Forties director of dramas, he learned from Toland and Welles that it’s fun to shove the action into the viewer’s face. The high angles of the city are counterbalanced by steep, low setups both inside and outside. Mann never met a “Russian angle,” or a ceiling, he didn’t like.

When the lens is more or less straight on, the frame can be tight and actors’ heads are packed into the frame like cantaloupes in a supermarket display.

In motion, the camera isn’t safe. Actors rush past the lens or thrust themselves straight at it.

When Joe flings himself out of a car, prepare to find yourself in the middle of traffic, with a truck rushing at you (a stunt done in real space, not against a back-projection).

Yet even studio-shot back-projections retain vigorous, immersive depth.

Mann’s visual dynamism, complete with aggressive foreground and distant depth, hits a high point in the dialogue-free scene that’s the topic of today’s sermonette. Joe hasn’t planned to steal the money, but circumstances lure him on. The lawyer’s out of his office, and the door has been left ajar. Joe earlier saw the money put into a file drawer, and as Joe prepares to slide the mail under the door, the cabinet stands temptingly in the foreground.

He impulsively heads for the cabinet, pauses before it, and then—thanks to an abrasive cut—grabs the handle violently. The drawer is locked. He recovers himself, almost grateful that he’s blocked, and he lurches out the door. No theft today, apparently.

Outside, Joe seems to be going on his way, but the long shot shows a barrier, like a railing in the foreground. It seems about as innocuous as the car hood we saw when Joe went in the building.

As Joe approaches, the camera tilts up to follow him and he stops, staring. He’s framed before what’s now revealed as a fire axe.

Another director—Hitchcock, perhaps—would have handled this with a medium-shot of Joe leaving and looking off, followed by an optical POV shot of the axe. Or you could show him leaving in the foreground, with the axe mounted in the distance; he glances back, sees it, and decides to go fetch it.

By contrast, Mann’s approach yields a sharp one-two snap: Joe approaches/ he stops. We see the axe, but almost by accident; the reframing is just following Joe’s movement. And we don’t need to see any more of the thing but its distinctive shape—its pure axe-ness given in silhouette. Rudolf Arnheim, who always advocated pictorial simplicity, would be pleased.

After a beat, in an abrupt cut, Joe grabs the thing.

He lunges down the corridor back to the office and starts to break into the cabinet. Now his violent adventure begins.

Crime I’m not so sure of, but with bodacious filmmaking like this, who wouldn’t acquire a deep and morbid interest in cinema?

It’s been too long since our last “Sometimes…” entry. For the others see: “Sometimes a shot . . .” and “Sometimes two shots . . .” and “Sometimes a jump cut…”

Bosley Crowther’s review of Side Street is “The Screen: New Crime Story,” New York Times (24 March 1950), p. 29.The Variety reviews, more or less identical, are in Daily Variety (22 December 1949), p. 3, and Variety (28 December 1949), p. 6. The Times covers the shooting of the climactic chase in “Taxi Acrobatics in Wall Street” (8 May 1949), X5.

For more on the postwar cinema’s love affair with vigorous depth staging and depth of field, see this entry on Bergman and Antonioni, this entry on Toland and depth of field, this entry on Manny Farber’s objections to Huston, this entry on dense staging, and this entry on Wyler’s staging in The Little Foxes. For much more see Parts Three and Four of our Film History: An Introduction, Chapter 27 of The Classical Hollywood Cinema, and Chapter 6 of On the History of Film Style.

Side Street.