Archive for the 'Streaming' Category

Moana’s roundabout voyage back to the multiplex: A guest post by Nicholas Benson and Zachary Zahos

I dimly remember hearing in late 2020 that the sequel to Moana (2016) was going to be Moana: The Series, streaming on Disney+ rather than a theatrical feature. David and I liked Moana very much, but in those of Covid and non-theater-going, it seemed a minor thing. A series wasn’t appealing, and we could just ignore it. Then about a year ago it was re-announced as a theatrical feature. I just assumed that the powers-that-be had simply decided that what was by that time being called Moana 2 would make more money by being released “Only in theaters,” as the posters inevitably pointed out.

That was true, but there’s much more lurking behind such a decision. Straight to streaming or released to theaters first? has become a puzzling question for studios as they discover that the huge profits they assumed their new streaming services would bring in were not all that huge or maybe not profits at all.

I am delighted to have two experts, Nicholas Benson and Zachary Zahos, who follow the distribution strategies of the film industry, contribute a guest post on how Moana 2’s change from modest Disney+ series to a box-office hit creeping up on the total domestic gross of Wicked reflects major shifts in the industry’s decisions about releasing options.

Nicholas Benson received his Ph.D. in Media and Cultural Studies from the University of Wisconsin-Madison and is now an Assistant Professor in the Department of Communication and Media at SUNY Oneonta. His current work considers the intersection of discourses of storytelling and management within franchise production cultures. Zachary Zahos also received his Ph.D. from the University of Wisconsin-Madison and is currently serving as Public History Fellow at the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research. Back in September Zach and Matt St. John contributed a entry to this blog, examining a claim that movie lovers had stopped going to theaters.

Thank you, Nick and Zach, for your contribution to our understanding of the current tangled distribution systems of the current industry! Over to you.

The curse has been lifted—at Walt Disney Pictures.

After a run of box-office bombs, Disney’s flagship film studios bounced back in 2024: Pixar with Inside Out 2, 2024’s top-grossing film, and Walt Disney Animation Studios with Moana 2, which just cleared $1 billion globally. Even Mufasa: The Lion King, a CGI prequel produced by Disney’s live-action division, looks destined to overcome a weak start to become a profitable “sleeper hit.”

The cynical read on all this is that Disney, to quote The Town’s Matt Belloni, “engineered” a surefire 2024 by pushing riskier bets, such as Pixar’s Elio and the Snow White remake, to this calendar year. But, at the end of the day, adaptive engineering, risk mitigation, studio chicanery, whatever you call it—this is how Hollywood lives to tell another tale, and you need not look further than Moana 2 for a revealing case of Disney executives reading the horizon and changing course.

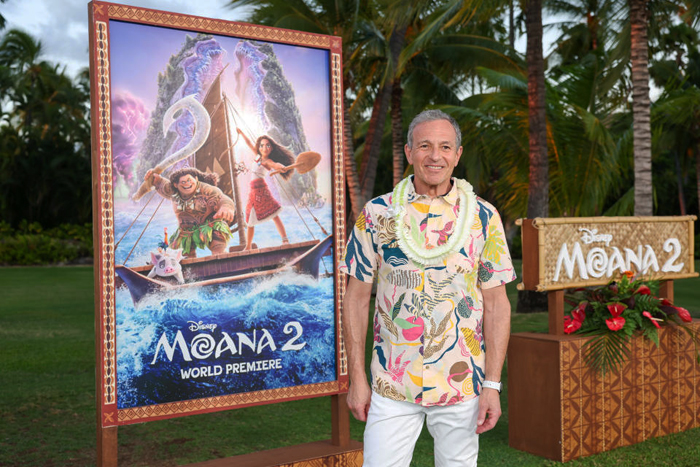

Moana 2’s present status, as a resounding theatrical success, interests us in particular due to the roundabout journey—and P.R. spin—it took to get here. For those unaware, the film now playing in multiplexes called Moana 2 was greenlit in 2020 as a television series (titled Moana: The Series) for the company’s streaming platform Disney+. It was only last February when CEO Bob Iger announced that this project was instead heading to theaters under the new title Moana 2. While the trades were quick to discuss the financial calculus behind such a shift (per Deadline: “after misfires … more Moana is a safe bet for the House of Mouse”), Disney has been careful to publicly attribute this decision to creative, rather than business-minded, imperatives. For instance, Jennifer Lee, former CCO at Disney Animation, told Entertainment Weekly in September:

We constantly screen [our projects], even in drawing [phase] with sketches. It was getting bigger and bigger and more epic, and we really wanted to see it on the big screen. It creatively evolved, and it felt like an organic thing.

As genuine as this sentiment might be, we sincerely doubt that Moana 2’s last-minute about-face, from streaming series to theatrical film, emerged from creative disagreements alone. The film industry has changed rapidly over the last five years—streaming has undergone its own boom and bust cycle during this time, with vintage concepts like advertising, bundling, and return-on-investment, bringing Hollywood executives down to earth. In short, the Walt Disney Company that announced Moana: The Series in 2020 is different from the one that released Moana 2 in theaters last month.

Longtime readers will recall this blog’s fondness for the first film, as shared by David, Kristin, and Jeff Smith. We count ourselves Moana fans, as well, while also agreeing with critical consensus that Moana 2 lacks the inspiration (or songs) of the original.

But what follows is not a review. While we will make reference to certain storytelling choices present in the film, our main goal here is to argue that Moana 2—or, more specifically, the production and circulation context surrounding it—is symptomatic of a global industry in flux. As the world’s largest legacy entertainment company, Disney is not one to buck trends but rather to reinforce them. An engaged analysis of Disney’s recent executive-level decisions offers us a chance to gauge which way the winds of commerce are blowing.

Yet the company’s sheer scope, both internally and across its multi-generational audiences, invariably creates sites of tension and contest. We see that in Jennifer Lee’s public assurances concerning Disney’s creative community, and not its C-suite, steered Moana 2 into theaters. But we also see such tension and contest in how Moana 2’s production history throws long-standing hierarchies at the Walt Disney Company into relief. As a result of Disney+ and recent executive initiatives which we will delve into here, the line separating the company’s film and television output has become increasingly blurred, as have the rules for successfully exploiting marquee franchises, particularly those geared toward younger audiences.

What is clear to us is that, even in success, Disney+ has failed to solve all of its parent company’s problems and in the process has created several new ones. This is not simply because of profit margins, but also because such investments, from both studio and audience, run downstream from discursive categories like “film,” “television,” and “streaming.”

In the case of Moana 2, the shift of Disney’s prized sequel from the “streaming television” to the “theatrical film” column, months out from release, occurred in large part due to the promise of greater financial returns. That much seems obvious, no matter what Jennifer Lee and other creative executives say, given how most studios across the industry have learned to love movie theaters again.

But we do not wish to suggest these leaders are lying through their teeth, either. As strategic as Lee’s statement to Entertainment Weekly may have been, she does seem to genuinely represent the values and norms of the world’s most famous animated film studio. Where else but movie theaters do you go when you design your expensive franchise sequel to be “bigger and more epic”? So, while Moana 2 sailed back to multiplexes amidst an industry-wide correction away from pyrrhic victories in streaming, its journey looks especially inevitable if you account for the particular industrial apparatus from which the film came.

We’ll expand on these ideas by teasing out a few historical threads relevant to Moana 2’s production. These concern Disney+, Disney Animation Studios, and the Walt Disney Company, as well as the latter’s general playbook toward franchising animated entertainment.

Disney+ and the business of animation today

Disney’s recent theatrical rebound is notable given the obstacles—some of them industry-wide, others self-inflicted—its film division has faced since its peak in 2019. That year, Walt Disney Studios reported $11.1 billion in worldwide theatrical revenue, with a record seven films (among them the animated sequels Toy Story 4 and Frozen II) each surpassing $1 billion at the global box office. In November of 2019, the company launched its Disney+ streaming platform. While it always seemed destined to succeed, Disney+ exploded in growth months later as the COVID pandemic closed theaters and Disney’s theme parks.

Since that high-water mark, Disney’s films have struggled, partially due to counterproductive distribution decisions and a streaming-focused production pipeline. On the distribution side, during the pandemic then-CEO Bob Chapek (above) launched Disney+’s day-and-date “Premier Access” program and arranged for Pixar’s latest films, beginning with Soul (2020), to skip theaters and instead premiere on the streaming platform. While this strategy fueled subscriber growth, almost every animated film Disney released to theaters in its wake, most notably Lightyear (2022) and Strange World (2022), underperformed at the box office. Analysts have attributed this cold streak to a range of causes, including the notion that Disney’s streaming release strategy had “conditioned audiences” to wait for theatrical releases to hit streaming.

Much ink has already been spilled on another contributing pop psychology phenomenon, that of “franchise fatigue.” The idea that audiences are burned out by the proliferation and interconnectedness of so much franchise material may not be neatly supported by the data. The top 10 movies of 2024 were all franchise properties, after all. It is a more credible notion if one examines Disney’s many spin-offs on streaming. Since 2019, the company’s marquee film production companies, among them LucasFilm and Marvel Studios, have shifted resources to producing long-form television series for Disney+. LucasFilm and Marvel respectively launched their Disney+ slates with The Mandalorian and WandaVision, both of which were well received and highly rated. But ever since, Disney’s streaming series have attracted increasingly mixed critical responses (even after controlling for toxic fan reactions) and diminishing viewership numbers (here and here).

That does not mean all Disney+ originals are destined for failure. What seems increasingly clear is that certain forms of programming, such as animation, perform more consistently, albeit under a typically lower ceiling of viewership. In October, The Hollywood Reporter published a 3000+ word article headlined, “Is Disney Bad at Star Wars? An Analysis.” To be clear, the piece answers its core question with, “On balance, no.” Nevertheless, this article is relevant to this discussion in that it contrasts the strong ratings of the Star Wars animated series on Disney+ with the franchise’s live-action series for the same platform. New animated series like The Bad Batch have more than earned their keep, with their large volume of episodes (usually 16 per season vs. 8 for live-action series) driving viewer engagement at a fraction of the cost of their recent live-action counterparts.

So, Disney+ is a sensible launching pad for new animated Star Wars series. Does that make it also wise to premiere the latest Disney Princess tale on the same platform? (Despite Moana 2’s “Still not a princess!” joke, in the eyes of Disney, she officially is one, as the Princesses scene in Ralph Breaks the Internet, below, demonstrates.) Well, that depends.

Traditionally, Disney has had three main paths for exploiting animated franchise content: theatrical distribution, commercial television, and direct-to-video (DTV). Each of these had clear advantages and disadvantages, and for many years these three paths looked fairly straightforward. Theatrical distribution, both then and now, is prestigious and visible to a large, diverse audience, and it comes with the potential for massive global box office revenues and merchandising opportunities which can immediately counteract the large budget.

The other two categories—commercial television and DTV—were lucrative paths for many years at the Walt Disney Company, but under the Disney+ paradigm have begun to appear less distinct from the theatrical option. Commercial television traditionally came with less expectation that it feel cinematic, and therefore could be made on a smaller budget. Television series promise a smaller, more concentrated audience of children or existing fans and a long tail financial model that relies on revenue generated through ad support and future syndication possibilities. DTV content, for its part, follows a similar model to commercial television but at an even lower scale of cost, with accordingly lower (but faster) profit potential.

The visibility of commercial television content within the Disney animated fold is moderate (and outright low for DTV). Millions of children apparently watched the Tangled (2010) spin-off Rapunzel’s Tangled Adventures, which was produced by Disney Television Animation and aired from 2017 to 2020 on the Disney Channel. We don’t expect you, reader, to have heard of this show, though at the same time we would be surprised if you never before heard of Tangled. Thus, even resounding successes of this type will remain off the radar of the general, adult-aged public, and so commercial television spin-offs, even if not the highest quality, will not inherently hurt the brand as a large film can.

It’s on this last point, regarding visibility, where the project formerly known as Moana: The Series was always destined to be different. With the company’s flagship studio, Disney Animation Studios, producing it, the budget leaped beyond any animated project Disney produced before for television or DTV. Launching Moana: The Series exclusively on Disney+ had potential upside, but as we will see, these benefits began to look questionable.

Moana’s voyage toward streaming…

Moana: The Series was first announced, by Jennifer Lee, at the virtual Disney Investor Day event in December 2020. The broader theme of the investor’s day was Disney’s new structure, which separated content creation from distribution in a bid to turn to what newly appointed CEO Bob Chapek referred to as a “DTC [direct-to-consumer] first business model.” The Moana series thus joined a slate of other Disney+ releases, including day-and-date release movies like Raya and the Last Dragon (2021), Marvel series such as Loki (2021-2023), and limited series such as WandaVision (2021). Though executives continued to gesture towards the importance of “legacy distribution platforms,” such as theatrical and linear television, the focus was on the corporation’s investment in Disney+. As Chapek put it in his opening statement:

We knew this one-of-a-kind service featuring content only Disney can create would resonate with consumers and stand out in the marketplace and needless to say Disney+ has exceeded our wildest expectations.

The idea to expand the Moana franchise into a series, therefore, was a direct result of corporate confidence in DTC platforms as the future of distribution. Chapek’s new corporate structure promised a streamlined production pipeline that seemed to completely separate the creation and production process from the distribution process — in other words, creatives would generate content and then the distribution team would figure out the best way to get that content to the consumer. Chapek explained the structure in a statement:

Managing content creation distinct from distribution will allow us to be more effective and nimble in making the content consumers want most, delivered in the way they prefer to consume it. Our creative teams will concentrate on what they do best—making world-class, franchise-based content—while our newly centralized global distribution team will focus on delivering and monetizing that content in the most optimal way across all platforms, including Disney+, Hulu, ESPN+ and the coming Star international streaming service.

This new agnostic approach to distribution seemed to lead to a general confusion about how to staff DTC productions. The Moana follow-up presented a mixed bag in terms of who was brought back from the original production. Voice talent Dayne Johnson and Auliʻi Cravalho respectively reprised their roles as Maui and Moana. However, original Moana directors Ron Clements and John Musker were absent. Instead, Jason Hand, Dana Ledoux Miller and David G. Derrick Jr. (above) were hired to co-direct and run the series. Hand, who had the most experience working with Disney animation of the three, started his career at Disney in 2005, as a layout artist on the DTV sequels Tarzan 2: The Legend Begins and Lilo & Stitch 2: Stitch Has a Glitch. Disney has a well-known apprenticeship program and tends to hire and promote from within, so it’s not out of the ordinary that a series like this would be given to greener talent looking to gain experience.

That said, Moana: The Series’s production team was indicative of a broader ambivalence the company seemed to have about how much to invest in, and therefore how to staff, DTC content. While the series Baymax! (2022) brought in Big Hero 6 (2014) director Don Hall as showrunner, other series like Zootopia+ (2022) and the upcoming Tiana (2025) did not bring back the same directing or writing teams from the original films. Instead, Zootopia+ was directed by Trent Correy and Josie Trinidad, who previously worked in the Animation and Story departments on Zootopia, respectively. Tiana is reportedly being run by Joyce Sherri, who served as staff writer for the Netflix miniseries Midnight Mass (2021).

…and back to the multiplex

News on the Moana series remained sparse from 2020 until February 2024, when Bob Iger announced during a CNBC interview that the series would now be a theatrical feature slated for a fall 2024 release. The news came shortly before a Q1 earning call where he assured shareholders that “the stage is now set for significant growth and success, including ample opportunity to increase shareholder returns as our earnings and free cash flow continue to grow.”

Iger’s assurance came on the heels of a tumultuous few years for Disney, after a series of box-office failures and an internal struggle for power that resulted in the ousting of CEO Bob Chapek and a return to the post for Iger. While the issues faced by Disney were multifaceted, the all-in approach to DTC content was central to the company’s financial struggles. Subscriber fees could only generate so much revenue, and that revenue didn’t seem enough to sustain the enormous content library required to maintain a streaming platform. In September of 2022, Bob Chapek indicated to Hollywood Reporter that Disney+ had a content problem. As Chapek put it:

It’s important to go back to when Disney+ was launched and what the hypothesis was about how much food you had to give that system for it to truly maximize its potential, and I would say we dramatically underestimated the hungry beast and how much content it needed to be fed.

The extent of this issue became apparent during a 2023 lawsuit against Disney by investors alleging Disney hid the actual costs of running the service to offer the appearance of profit potential. Though the service is reportedly now profitable, since its inception Disney+ has racked up over 11 billion dollars in losses, showing that the DTC, subscription-based model has not been the massive success it was predicted to be in 2020.

In late 2024, as the premiere for the re-titled Moana 2 approached, those who worked on it related to press outlets various versions of how the series abruptly shifted to a theatrical film. We can return to that September Entertainment Weekly profile to see a few explanations side-by-side. For instance, co-director David G. Derrick Jr. described the decision to pivot from a series to a feature film as a moment of “mutual realization” between the studio’s various teams:

It became apparent very early on that this wanted to be on the big screen. It felt like a groundswell within the whole studio.

Co-director Dana Ledoux Miller framed it as a push from the creatives, out of a desire to showcase their work. She suggested the project had “the best artists in the world” and added:

Why are we not letting them shine on the biggest screen in the biggest way?

This rhetoric stood in sharp contrast to Chapek’s 2020 Investor Day video, in which he seemed to downplay the importance of theatrical distribution in favor of the convenience of DTC exhibition. At that point, there was no sense that artists would feel minimized by having their work showcased on DTC platforms. Instead, these new comments by the creative team touted theatrical exhibition as a prestigious honor and the only way to showcase quality artistic achievement.

In other words, after years of the studio relegating several projects to Disney+ or day-and-date releases, Moana 2’s pivot feels like a pointed reinvestment in the theatrical experience. Jennifer Lee reinforced this perspective when she said to Entertainment Weekly:

Supporting the theaters is something that we talked about. … We love Disney+, but it will go there eventually. You could really put it anywhere, but these artists create stories that they want to see on the big screen and that we want the world to see on the big screen.

When the show was reworked as a movie, the absence of certain high-profile talent associated with the first Moana—especially popular songwriter Lin-Manual Miranda—became apparent. The official reason for Miranda’s absence was that he was already committed to another Disney theatrical project, Mufasa: The Lion King (2024). While Moana composers Mark Mancina and Opetaia Foa’i did return to score the movie, the new songs for the sequel were primarily composed by Abigail Barlow and Emily Bear. The two were, as Billboard put it, “the youngest (and only all-women) songwriting duo to create a full soundtrack for a Disney animated film.” Until that point their only real credit was writing an unsanctioned viral musical based on the Netflix show Bridgerton (2020 – ). Though having young women write the music for a musical about young women was a positive move for Disney, the pair’s relative inexperience became more conspicuous when the Disney+ show was transformed into a tentpole feature film. In its review of the film, The Hollywood Reporter noted that “Miranda’s absence is unfortunately felt” throughout the musical numbers. Variety, more pointedly, called the new batch of songs, “imitation-Lin-Manual knockoffs.”

The lack of personnel continuity between Moana and Moana 2 highlights the general disorganization within Disney’s new corporate structure. Despite the claim that content can be created and then distributed wherever by reading the will of the data gods, the reality is projects still seem to work best when the venue of the exhibition is known during the early stages of production. When Disney has done theatrical sequels they tend to staff them with creative talent from the original. Jennifer Lee oversaw the creation of Frozen 2 (2019), Andrew Stanton returned for Finding Dory (2016), and Pete Doctor directed Inside Out 2 (2024). Though Miranda claims he was otherwise preoccupied, one wonders if he would have still worked on Mufasa: The Lion King had he known the Moana follow-up was destined for a theatrical release.

While this is primarily an industry analysis, even a cursory look at Moana 2’s narrative reveals the editorial marks left by this unusual production. As with the first film, the sequel tasks Moana with breaking an ancient curse, except this one was set by a storm god named Nalo, who drove the different peoples of Polynesia apart. With this clear objective, Moana remains a classical, goal-oriented protagonist, but the seams begin to show once you look at the other characters. Curiously, Nalo remains an off-screen antagonist, who is not properly introduced until a mid-credits scene that mimics Thanos’s first appearance in The Avengers (2011). The journey is also now populated by a group of secondary characters easily identified by a defining trait (e.g., Moni is a huge Maui fanboy). The first act, set on Moana’s well-populated island of Motunui, feels especially abridged from the project’s looser, episodic origins, and the onslaught of new characters leaves little room for the emotional depth and character development that many critics respect about the first film (here and here).

The seams where Moana: The Series was stitched together into Moana 2 are not only evident in the story, but in the production and promotion as well. Being forced into the throes of a giant A-list press junket was probably not what these first time directors signed up for; it’s certainly something the team behind the direct-to-video Cinderella II: Dreams Come True (2002) never had to deal with, and for good reason.

Yet Moana 2’s directors were left answering questions about decisions made in the first movie they had little or no control over. For example, the cute pig Pua, whom fans felt was underused in the original movie, took on a more prominent role in the sequel. When asked by CinemaBlend if they responded to any feedback about the first film, director/writer Dana Ledoux Miller responded:

Look, people really wanted Pua in that first movie on the canoe. I wasn’t around, but we put Pua on the canoe now.

While not overly awkward, the exchange highlights the behind-the-scenes break in continuity. Similarly, young songwriters who should be establishing their own identity were instead having their work compared to the beloved music of Lin-Manuel Miranda. Ultimately, while this has financially paid off for Disney, Moana 2 was clearly a ship built for the smaller more secluded waters of Disney+. Though it has survived, the tepid reviews suggest it may have been only by the skin of its teeth.

Riding the popcorn-bucket wave

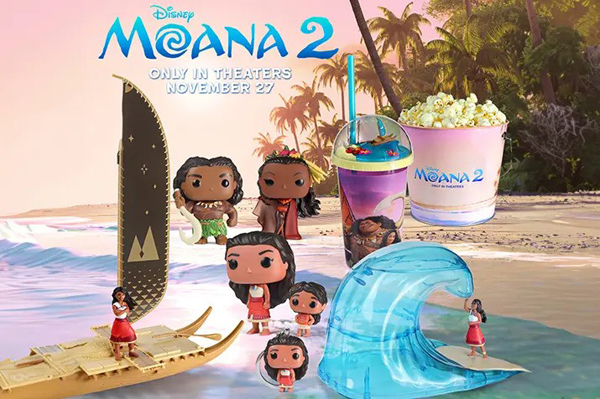

Moana 2 is not only indicative of the pitfalls of the DTC model but highlights the inherent potential of theatrical distribution, especially for franchised content. Despite lukewarm reviews, the movie has already earned record numbers at the box office. More importantly, it has reignited interest in the brand more broadly. Moana became the latest entry in a list of high-profile collectors’ popcorn buckets distributed by theaters (above).

While they might seem like a gimmick, these popcorn buckets have become an integral aspect of the theatrical distribution model and the “post-pandemic ‘identification’ of moviegoing.” They  work in favor of both the theaters and the studios by raising awareness about the films and the brand. As one journalist pointed out, “I didn’t realize Despicable Me 4 was happening until I saw the popcorn bucket.” With the release of toy lines (Funko dolls aplenty, including Pua, above and left), popcorn buckets (and nacho boats!), and theme park tie-ins, the hype machine that spins around a massive theatrical release has become somewhat intuitive over the past century in a way that DTC models have difficulty emulating, even with the benefit of synergy within vertically integrated corporate structures.

work in favor of both the theaters and the studios by raising awareness about the films and the brand. As one journalist pointed out, “I didn’t realize Despicable Me 4 was happening until I saw the popcorn bucket.” With the release of toy lines (Funko dolls aplenty, including Pua, above and left), popcorn buckets (and nacho boats!), and theme park tie-ins, the hype machine that spins around a massive theatrical release has become somewhat intuitive over the past century in a way that DTC models have difficulty emulating, even with the benefit of synergy within vertically integrated corporate structures.

Though box-office numbers are important, this hype is equally valuable. In this way, Moana 2 was a success even before it debuted. The trailer for Moana 2 broke the record for the most-watched trailer for a Disney movie ever, reaching over 178 million views in 24 hours. Likely not coincidentally, that trailer ended with an image of Maui holding Pua, announcing that this cute character was, as Miller had put it, “on the canoe” and (more importantly) ripe for new licensing deals. When Moana 2 was announced to be a movie, it kicked off one of the largest and most lucrative global merchandising campaigns in recent memory. Apart from Moana merchandise, there were brand partnerships with airlines to local Hawaiian food chains. Imagery flooded public spaces. Hasbro introduced cutting-edge 3D printing technology to inject toys and dolls as quickly as possible into the marketplace. This success, both in theaters and retail, suggests that even if somewhat clunky, the 11th-hour decision to turn a television show into a movie seems to have been financially prudent – at least in this instance.

New rules, some of them old

During Disney’s 2024 Q4 earnings call, Bob Iger admitted, seemingly unintentionally, the motivation for recent subscription price increases for Disney+. According to Iger, these streaming price hikes were designed less to generate revenue through subscriber fees and more to shift consumers to the ad-supported model:

It’s not just about raising pricing, it’s about moving consumers to the advertiser-supported side of the streaming platform. … The pricing that we recently put into place, which is increased pricing, was actually designed to move more people in the AVOD [advertising video-on-demand] direction because we know that the ARPU [average revenue per user] — and interest in it from advertisers in streaming — has grown.

Iger’s comments point to how these companies are starting to recognize (or grapple with) where the actual value of the streaming service lies within the broader corporate structure: specifically, how the streaming service functions, or serves, the vast media franchises these companies have restructured around. Until recently, executives imagined them as vertically integrated platforms that allowed corporations to get content directly to consumers without the need for middlemen (though, with the exception of Comcast, third-party telecom companies still control the actual distribution pipeline, complicating the notion that these are truly vertically integrated systems). As this system evolves to support ads, content will need to be capable of sustaining viewers over time and selling ad space to sponsors. In other words, despite all the obfuscation of what will likely amount to a transition period, streaming services seem destined to be mostly a different distribution platform for what had been commonly known for the past century simply as commercial television.

Despite some disruptions over the past several years, theatrical distribution continues to hold a privileged position in the cultural zeitgeist, especially for high-profile properties. Movies can air on TV, but the experience of watching them is still culturally different from that of watching something in a movie in the theater. The act of going to the movies is an event apart from one’s day-to-day life (one must schedule a movie, what David called “appointment viewing”), while television, regardless of its distribution mechanism, remains intertwined with the cadence of one’s daily routine.

Take, for example, a recent review of Mufasa: The Lion King (2024) in Polygon. Writer Petrana Raduloviv opines that the movie would have fared better as a video-on-demand release:

Mufasa: The Lion King, the 2024 movie about Simba’s majestic father, seems like it could exist right alongside Simba’s Pride, The Lion King 1 ½, and the animated TV show The Lion Guard. Except instead of being cheaply thrown together for young audiences, it was directed by Academy Award winner Barry Jenkins (Moonlight, The Underground Railroad), with a script from Catch Me If You Can screenwriter Jeff Nathanson, and music from Lin-Manuel Miranda.

In other words, the string of Lion King sequels might lead people to think that this latest one could be treated like the previous ones, being presented DTV. The celebrity talent involved, however, kindled enough interest to lure audiences into theaters and make Mufasa a hit.

Despite claims to the contrary, lines between various exhibition sites remain strong. DTV content and theatrical releases are seemingly different cultural categories that, in turn, invite different reading strategies. As the above quote suggests, success is, in part, based on expectations, and expectations tend to be tied directly to the site of the exhibition. As media conglomerates consolidate and organize transmedia franchises, they must negotiate the utility and corporate value of each exhibition site at their disposal. The task for media producers over the next few years is to calculate the financial value of these cultural categories and use that to calibrate the production costs of their various franchise proliferations. In short, this difference in cultural capital between these two exhibition sites constitutes a difference in industrial strategy as corporations seek to exploit and profit from their various properties in myriad ways. How this shakes out will have lasting effects on the future of film and television creation for decades.

Studios are grappling with these questions of medium-specificity, appropriate exhibition, and franchise management in real-time. New rules are being forged that will shape the future of distribution. As we see it, streaming is unlikely to collapse theatrical and television into a single system but instead offer a hybrid exhibition site that seems to fill the role of both commercial television and the direct-to-video market.

What complicates streaming currently is that it has traditionally been subscriber-supported and therefore followed a premium cable, rather than a commercial television, model of production (see Amanda D. Lotz for more on this distinction). Unlike the commercial television or direct-to-video route, where the value for those exhibition options was tied to their lower production costs, streaming tends to demand a similar quality production to film since it’s not really competing with broadcast television. Instead its rival is seemingly premium cable programming like Game of Thrones. Therefore, it’s very expensive, sometimes more expensive than film production.

Streaming tends to look for a larger audience and is not aimed at exploiting as much as expanding a story world as a franchise. This strategy may be something that fans of that particular story world want, but a general audience would rather watch individual stories than dive into an elaborate franchise saga. Streaming shows also tend not to consistently generate the same cultural impact as a theatrical release (is anyone talking about The Skeleton Crew?). In other words, as it exists, streaming offers the worst of all worlds for media conglomerates looking to exploit their intellectual properties in ways that generate revenue and help the brand. Shows are expensive to produce, they can generate bad press and harm the brand, but they have very little potential to generate large revenues.

We would argue that this is likely why Moana: The Series was reworked into Moana 2 and prepared for a theatrical run. Though the budget has not been officially revealed, based on industry sources, the budget was likely close to the $150 million budget of the first movie. In other words, it’s not because the story got “too big,” but because the budget was too big to justify it being tossed into the increasingly large pile of disposable Disney+ content.

Moana 2 is part of a clear trend. In 2023 The Mandalorian’s final season was transitioned from a Disney+ series to the upcoming theatrical release, The Mandalorian and Grogu (2026). Inside Out 2 (2024) enjoyed a successful box office run as a traditional Pixar theatrical release. A few months later, after the movie hit streaming services, the short, animated spin-off series Dream Productions (2024) debuted on Disney+. The four-episode limited series was produced on a severely reduced budget concurrently with the feature film production. However, mid-production Disney cut the episode order from seven to four.

When Moana: The Series was announced in 2020, Disney also announced a Tiana musical series based on the Princess and The Frog (2009). Though it was set to be released in 2023, it’s still in development – perhaps preparing to shift into a feature film. Disney has also systematically canceled or prepared to phase out many of its more expensive shows, even popular ones. Shows such as Ahsoka, Andor, and The Acolyte are all being canceled after one or two seasons. This suggests that Moana 2 did not evolve on a whim, but rather as part of a broader systematic move away from expensive Disney+ series and towards high-profile theatrical content. As Disney builds its advertising infrastructure, we’ll likely see Disney+ pursue things like Young Jedi Adventures (2023): franchise spin-offs aimed at families and children that are relatively cheap to produce and have syndication potential.

Yet Moana 2 also highlights a unique value of streaming over other forms of exhibition: data. Moana (2016) was the most streamed movie of 2023. Because of this, Disney knew that Moana (2016) was popular among their fanbase. This likely gave Iger and others some confidence that even without the A-list creative talent behind the scenes, the property alone could carry a sequel to a box office win, which in turn results in positive press and better stock performance. Similarly, the popularity of The Mandalorian (2019 -) as the second most streamed series on Disney+, behind only The Simpsons, likely factored into the choice to greenlight The Mandalorian and Grogu (2026) for theatrical release. We would likewise guess that the greenlighting of Frozen 3 and Zootopia 2 was likely less about some burning creative need to expand those stories and more about promising Disney+ data.

The decision to release the Moana sequel in theaters also reflects the obvious point that theatrical movies generate a higher profile than DTV series. Once they end their theatrical runs and are offered on streaming services, the desire to see them may lead to new subscribers.

Ultimately, what we see is not the erasure of one form of exhibition in favor of streaming, or competition between theaters, television, and streaming services, but the formation of a nascent symbiosis between these sites, as media conglomerates consider their place within each corporate enterprise.

Our gratitude to Matt St. John for inspiring and improving this piece.

We would also like to thank Kristin for her edits and insights on contemporary animation.

Relevant to this discussion is a newly filed lawsuit suing Disney for copyright infringement over the Moana franchise. Entertainment Weekly broke this news on January 12, and it goes without saying that we will follow this case as it proceeds.

Calm that camera!

Succession (2023).

DB here:

Thanks to our Wisconsin Film Festival, Ken Kwapis paid us a visit. Director of The Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants and many other features, Ken also has experience directing TV, notably The Office. He’s a generous filmmaker, and he radiates enthusiasm for his vocation. I took the opportunity to talk with him about camera movement in contemporary media. He taught me a lot, and what I’ve come away with I share with you.

Camera ubiquity, with a vengeance

In the early silent era, fiction filmmakers around the world discovered what we might call camera ubiquity—the possibility that the camera could film its subject from any point in space. This resource was more evident in exterior filming than in a studio set, so early films often display a greater freedom of camera placement when the scene is shot on location.

At the same time, filmmakers began realizing the power of editing. This technique offered the possibility of cutting together two shots taken from radically different points in space. Yet an infinity of choices is threatening, and some filmmakers, mostly in the US, constrained their choices by confining the camera to only one side of the “axis of action,” the line connecting the major figures in the scene. Different shots could cut together smoothly if they were all taken from the same side of the 180-degree line. The result was the development of classical continuity editing. The director was expected to provide “coverage” of the basic story action from a variety of angles, but all from the same side of the line. Classical continuity was in force for American films by 1920 and was quickly adopted in other national cinemas.

The one-side-of-the-action constraint was encouraged by the fact that much filming of staged action took place on a set, designed according to the theatrical model. The camera side of the space was behind an invisible fourth wall, like that in proscenium theatre. To some extent directors compensated for the limitation on camera position by fluidly moving actors around the frame, from side to side and into depth or toward the viewer. Still, the “bias” in choosing setups was reinforced by the increasing weight of the camera in the sound era, which made it hard to maneuver within both interior and exterior settings. Camera movement in a more or less wraparound space was possible, but it was usually very difficult. It commonly required a dolly or crane on tracks to prevent bumps.

Technicolor filming, with its monstrously big camera units, reinforced the bias toward proscenium sets, 180-degree space, and a rigid camera. So did the postwar vogue for widescreen cinema. But in the 1950s filmmakers were also exploring the possibility of lighter, more flexible cameras. The body-braced cameras often produced bumpy, slightly disorienting images but yielded a more “immersive” space that gave the story action immediacy and spontaneity. By the early 1960s, handheld camerawork was being seen in both documentaries and fiction films. At the same time, fiction filmmakers were gravitating toward more location filming. In addition shooting on location with portable cameras promised greater savings on budgets, an attractive option for both independent and mainstream directors.

Handheld shooting was becoming more common in the 1970s, when its problems were overcome by the invention of the Steadicam, first displayed to audiences in Bound for Glory (1976). This stabilizer permits the operator to move smoothly through a space.

The new device was more than simply a substitute for a camera on a dolly and tracks. Ken pointed out to me that the Steadicam encouraged the increasing use of the walk-and-talk shot showing two or more characters striding toward a constantly retreating camera. This proved to be an efficient way of covering pages of dialogue. Beyond that, the Steadicam became an all-purpose camera for filming any sort of scene.

Over the same years, directors embraced multiple-camera shooting—originally aimed at handling complex stunts—for every scene, and they recruited A and B cameras, often mounted on Steadicams, for ordinary dialogue scenes. In most cases, the B camera was mounted alongside the A, but with the B camera in other spots there was a certain erosion of the axis of action. Now a conversation may be captured from a greater variety of angles than classical coverage would favor. Filmmakers have replaced 180-degree staging and shooting with what’s called 250-degree coverage. In The Way Hollywood Tells It I drew an example from Homicide: Life on the Streets. A free approach to the axis of action is common today, as in this example from Succession (2023).

A rough sense of the axis of action is maintained, and there are matches on action, but our vantage “jumps the line” as well. Moreover, the camera is constantly moving within the shots. It’s panning to follow or reframe the characters, sometimes circling them or abruptly zooming, and always wavering a bit, as if trembling. What some Europeans call the “free camera” is very common nowadays, and Ken and I talked mostly about this creative option.

Eye candy

By now, many filmmakers have chosen to make nearly every shot display some camera movement independent of following moving characters. This tactic was noted and recommended in a manual by Gil Bettman (First Time Director, 2003). (Readers of The Blog know of my fondness for manuals.) “To make it as a director in today’s film business, you must move your camera” (p. 54). The risk is making the audience more aware of the camerawork than of the story, so Bettman adds:

A good objective for any first time director would be to move his camera as much as possible to look as hip and MTV-wise as he can, right up to the point where the audience would actually take notice and say, ‘Look at that cool camera move.”

Like cinematographers in the classical tradition, Bettman declares that the camerawork should be “invisible” (p. 55). By now, you could argue, the predominance of camera movement has made it somewhat unnoticeable. Ordinary viewers have probably adapted to it.

One factor that aids the “invisibility” of camera moves is the speed of cutting. If the shots are short, the viewer registers the camera movement but probably doesn’t have time to notice whether it’s distracting or not. The effect of this isn’t restricted to action scenes. Even dialogue scenes may catch conversations up in a paroxysm of character reactions, camera movement, and swift editing. Creating these rapid-fire impressions, it seems to me, is what a lot of modern filmmaking seeks to do, at least since the early 2000s. It’s sometimes called “run and gun” shooting. Here’s an instance from The Shield (2003), with sixteen shots in less than a minute.

Arguably, Hill Street Blues (1981-1987) popularized this look for the police procedural genre, when DP Robert Butler urged his team to “Make it look messy.”

This sequence and the Succession passage points up another factor. Knowing that their films would ultimately be displayed on TV, some directors began “shooting for the box” by using tighter shots and closer views. TV directors such as Jack Webb were already working in this vein of “intensified continuity,” and many others had started their careers in broadcast drama and accepted the impulse toward forceful technique. Television has long demanded that the image seize and hold viewers, likely sitting in living rooms and prey to many distractions. Fast cutting and constant camera movements keep the viewer’s eye engaged. No surprise, then, that our TV programs present a fusillade of images that make it hard to look away.

Constant camera movement has another benefit. Many camera movements tease us. The start of a shot suggests that the camera will bring us new information, so we must wait for the end. Filmmakers love a “reveal,” and even a small reframing can suggest the camera is probing for something new to see. By now, however, filmmakers can play with us and use camera movement to flirt with our attention: the shot can begin with a clear image but drift away to conceal the main subject. I first noticed this almost maddening stylistic tic in The Bourne Ultimatum (2007), but it crops up occasionally elsewhere. In one scene of The Shield (2006), the camera slides behind a character, finds nothing to see, and slides back.

The peekaboo reframing would seem to throw the viewer out of the story in just the way that worries Bettman. I’m inclined, though, to think that it is part of a general, and fairly recent, expansion of viewers’ tastes. Self-conscious technical virtuosity has long been an attraction of mainstream filmmaking, and audiences have responded with appreciation. Think of Busby Berkeley or Fred Astaire dance numbers, or the railroad junction scene in Gone with the Wind. I suspect that many members of today’s audiences now happily say, “Look at that cool camera move” and don’t mind being pulled out of the story. (I’d say, though, that they aren’t being pulled out of the film, but that’s matter for another blog entry.)

This tendency would accord with what Bettman calls the taste for eye candy. For him, this seems to consist of bursts of light or color, usually produced by camera movement. More generally, I think audiences would consider impressive sets, striking costumes, and good-looking people to be eye candy. And now, I suspect, flashy camera work counts as eye candy too. The case is obvious with the showboating following shots in Scorsese and De Palma, but I think it applies to the jagged, in-your-face techniques seen in run-and-gun sequences. Advocates of the silent film as a distinct art never tired of insisting that cinema was above all pictorial. “The time of the image has come!” thundered Abel Gance. It took a while, but now that people compete for bigger home screens we have to admit, for better or worse, that everybody acknowledges that film is a visual art.

Many flies on many walls

Most moving shots today don’t utilize the Steadicam, whose usage needs to be budgeted and scheduled separately. The run-and-gun look is well served by modern cameras designed to be handheld. DPs and operators know that a wavering, even rough shot is acceptable to most modern audiences, and filmmakers seem to assume that handheld images lend a documentary “fly-on-the-wall” immediacy to the scene. In addition, wayward pans, swish pans, and abrupt zooms are felt to enhance that sense that we’re seeing something immediate and authentic. (Flies are easily distracted.)

Problem is, this approach is far from what a real documentary film looks like. True, the individual images might be rough, but their relation to one another is quite different from those in a documentary. For one thing, they occupy positions that documentary shots can’t achieve. Shot B may be taken from a spot we’ve just seen to be empty in shot A, as in the sequence from Succession. As Ken put it, “There’s no such thing as a reverse angle in a documentary.” Or shot B may be taken from a very high or low angle, where a camera is unlikely to perch, as in this passage of The Shield (2007) which hangs the camera in space peering through a railing.

Sometimes shot B will represent the optical viewpoint of a character, which is unlikely in an unstaged documentary. Putting it awkwardly, the free-camera style achieves a greater degree of camera ubiquity than we can find in a standard documentary. (Years ago, I made this point in relation to The Office.)

For another thing, the flow of run-and-gun shots always captures the salient story points. A documentarist, with one or two cameras following an action, is still likely to miss something significant (and to cover the omission with elliptical editing and continuous sound). But the modern method offers its own rough-edged equivalent of classical coverage. The action remains comprehensible. Sometimes the camera will even wander off on its own to frame something the characters aren’t aware of, providing a modern equivalent of classical “omniscient” narration.

What we have, I think, is a modern variant of the one-point-per-shot mandate of traditional editing, but featuring shots of that evoke greater “rawness” than studio filming did. And maybe it’s not as modern as we think. Here’s a sequence from Faces (1968), complete with walk-and-talk, or rather stagger-and-talk, as well as camera ubiquity and matches on action that would be difficult in a documentary.

I’d argue that John Cassavetes, much admired by filmmakers who followed, supplied the prototype for today’s run-and-gun look. Admittedly, it’s been stepped up; I suggested in The Way Hollywood Tells It that intensified continuity has been further intensified.

Nervous energy

Intensified how? Apart from all the swishes and zooms and focus changes, some bells and whistles aim to enhance the sense of “energy” attributed to the style. The peekaboo framings I mentioned would be one instance. Here are some others.

The shot, distant or close, which simply trembles. Let’s call it the wobblecam. It suggests the handheld shot, but it’s brief and seems shaky just to evoke a sort of vague tension. Wobblecam shots are so common now that entire scenes are built out of them, as in the Succession clip.

The arc: In filming TV talk shows, how do you keep viewers glued to the screen? One option is what a 1970 manual calls the arc. Here the camera travels in a slow partial circle that refreshes the image gradually. The framing reveals constantly changing aspects of the panelists and is a nice change from master shot/ insert editing. I remember this as common in 1950s programs.

The “roundy-round” (thanks, Ken): This extends the arc to 360 degrees, circling around one or more characters, urging us to watch for bits of action or dialogue—usually timed for maximum visibility. It’s also used to convey a character at a loss, say mystified by which way to turn, or characters embracing (whoopee). The technique can be found sporadically before the 1990s, when it becomes quite common. Ken pointed out that the roundy-round was extensively used on E. R. to underscore time slipping away during life-and-death surgery.

The “roundy-round” (thanks, Ken): This extends the arc to 360 degrees, circling around one or more characters, urging us to watch for bits of action or dialogue—usually timed for maximum visibility. It’s also used to convey a character at a loss, say mystified by which way to turn, or characters embracing (whoopee). The technique can be found sporadically before the 1990s, when it becomes quite common. Ken pointed out that the roundy-round was extensively used on E. R. to underscore time slipping away during life-and-death surgery.

The slider: The enhancement I find most distracting is the camera’s slow leftward or rightward drift while filming static action. Usually it’s a master shot, but it doesn’t have to be, and it can sometimes interrupt a series of close views. Unlike the wobblecam, this is more teasing because we’re used to such a shot revealing something. It doesn’t, but I think it holds out the promise and keeps us watching.

Writing The Classical Hollywood Cinema I came to realize that supply companies created lighting and camera devices designed to meet the developing needs of filmmakers. Thanks to Ken, I learn that this tradition continues. You can buy or rent gear that will enable arcs, roundy-rounds, and the slider (right). Both in technique and technology today’s Hollywood is a continuation of yesterday’s.

If a director constantly relies on camera movement, there’s no reason to object. The elegant moves of Ophuls or Mizoguchi or of McTiernan in Die Hard provide the sort of continuous engagement and ultimate pictorial payoffs that justify the technique. My examples illustrate more gratuitous camera moves, choices that “add energy” but once they’ve become conventional, seem wasteful. Usually, they reveal nothing and end up minimizing the power of a gradual reveal when it comes along.

But who am I to complain? Film styles change under production pressures and artistic inclinations. As a student of film history, I have to study what’s out there. Still, run-and-gun remains only one option. There are still lots of films and shows, like Tär and The Woman King and Barry, that rely on rigid camera setups and discreetly motivated movements. (Ken’s Dunston Checks In (1996), shown to an appreciative crowd at the festival, is a good example.) Another alternative is providing precise shot breakdowns that feature unusual “eye-candy” angles, as in Better Call Saul’s views from inside mailboxes and gas tanks. That trend constitutes another way to expand options within camera ubiquity. There are also the long-take films in which complicated camera moves preserve the patterns and emphases of classic continuity. (See the discussion of Birdman.) And then there’s the effort by Wes Anderson to go in the other direction, to submit to constraints far more severe than classical shooting—an austere refusal of camera ubiquity.

I must ask Ken about all these options too. Next time, I hope.

Thanks to Ken Kwapis, who enormously expanded my sense of the practical choices available to the filmmaker.

The TV production manual discussing the arcing shot is Colby Lewis, The TV Director/Interpreter (New York: Hastings, 1970), 131-132. Other mobile framings are reviewed in the same chapter.

For examples of filmmakers believing that the rough-edged style is like documentary shooting, see remarks on Succession in Zoe Mutter, “Fury in the Family,” British Cinematographer and Jason Hellerman, “How Does the ‘Succession’ Cinematography Accentuate the Story?” at No Film School. Butler’s comments on Hill Street Blues are quoted in Todd Gitlin, “’Make It Look Messy,’” American Film (September 1981) available here.

You can feel the thrill of silent-era creators and critics in realizing the possibility of camera ubiquity. Dziga-Vertov celebrated the power of the Kino-Eye to go anywhere, while Rudolf Arnheim saluted cinema’s ability to provide unusual angles that bring out expressive qualities of the world. What would they make of a shot like this below?

Better Call Saul (2015): Extremes of camera ubiquity.

Catching up

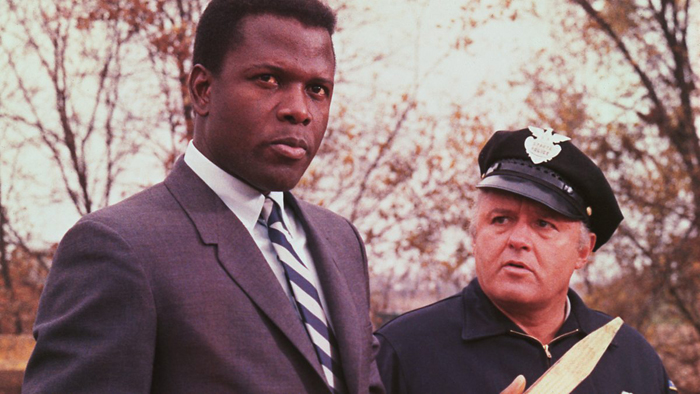

In the Heat of the Night (1967; production still).

DB here:

Some health setbacks have delayed my plans for a new blog entry, but as I clamber back from a bout of pneumonia, I thought I’d signal a couple of things I’ve read and enjoyed recently.

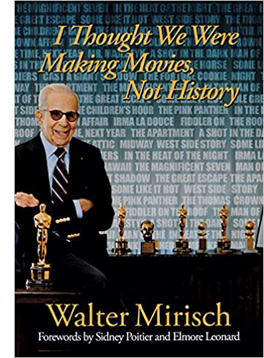

Walter Mirisch’s I Thought We Were Making Movies, Not History is a discreet but still informative account of the career of a major producer (In the Heat of the Night, Some Like It Hot, West Side Story, The Magnificent Seven, and many other classics). Apart from offering some vivid vignettes of working with stars, Mirisch (UW grad) is very good on the corporate maneuvering that created, then sideswiped, United Artists. He swam with sharks and survived. Bonus: introduction by Elmore Leonard.

Stylish Academic Writing by Helen Sword is a lively guide to perking up your prose. Unlike most tips-from-the-top manuals, this is based on systematic research that yields some surprises. (Yes, scientific reports are allowed to use personal pronouns. No, literary theory isn’t the most opaque writing on earth: Educational research is.) There’s a lot of good advice here. I wish I’d read it before revising Perplexing Plots.

A shrewd, funny analysis of (a) the current prevalence of mystery stories and (b) streamers’ shotgun programming policies is offered by J. D. Conner in “Going Klear: A Glass Onion Franchise in the Wild” in the Los Angeles Review of Books. This wide-ranging essay ponders franchises, viewer tastes, and other current concerns. Extra points for noticing the Columbo revival.

Way back in 1964, crime reporter Fred Cook caused a stir with The FBI Nobody Knows. After decades of celebrating the agency and its boss (a “confirmed bachelor” not yet revealed as in the closet), Cook’s chronicle of a frighteningly powerful force in the government inspired Rex Stout to write his top-selling Nero Wolfe book, The Doorbell Rang. Cook’s review of FBI history doesn’t out Hoover, and it does praise his ability to disclose WWII spy rings. But it concentrates on how his obsession with persecuting leftists had a long, ugly history. Today, when right-wingers are accusing the agency (staffed mostly with Republicans), it’s salutary to be reminded that the feds were long committed to ruining the lives of “communists” like Martin Luther King and ignoring the real danger of organized crime. Cook is helped by a whistleblower who reports mind-bending tales of peer pressure among agents. A lot of US history is crammed into this exciting, well-documented book.

I hope, when I can type (and think) more fluently, to post a new entry. On, I think, the power of crosscutting. Or maybe Puss in Boots: The Last Wish….

Clyde Tolson and J. Edgar Hoover in 1937. Source: The New Yorker.

P.S. 14 February 2023: In a stroke of serendipity, I learn that Paul Kerr’s new book, a historical-critical study of the Mirisch Company, is coming out next month. Knowing Paul, an expert on American independent production, I’m sure it will be deeply researched and an absorbing read. Congratulations, Paul!

P.S. 25 February 2023: Sad news: Walter Mirisch died yesterday. He was 101. The Variety report is here.

Streaming media: All you can eat, until it eats you

DB here:

In 2013 Spielberg and Lucas declared that “Internet TV is the future of entertainment.” They predicted that theatrical moviegoing would become something like the Broadway stage or a football game. The multiplexes would host spectacular productions at big ticket prices, while all other films would be sent to homes. Lucas remarked: “The question will be: ‘Do you want people to see it, or do you want people to see it on a big screen?’”

I wrote the preceding paragraph two years ago, and the Covid outbreak and enhanced technology have made the split between theatrical distribution and streaming distribution even sharper. (And as the Movie Brats predicted, multiplexes are raising ticket prices.) A crisis point was reached last month when Netflix glumly reported that instead of adding 2.5 million customers as it had expected, it lost some 200,000. Worse, the firm announced a likely loss of 2 million more in the next quarter. The news led Netflix stock to fall by over 30%, wiping out over $45 billion in value.

This stunning decline, coupled with Warner Bros. Discovery’s decision to cut the recently launched CNN+, sent shock waves through the industry. Stock values dropped for Disney, Warners, Paramount, and Roku as well, even though some had strong subscription growth. At the moment, disillusion seems to be settling in. A Wall Street analyst has noted:

We think the industry is facing a point of no return in which the economics of the old models look increasingly frail while the potential of the brave new world now appears overly hyped.

Discussions of mergers, acquisitions, and big company restructuring are ongoing, with layoffs already starting.

As researchers, we at The Blog try to see past current convulsions to larger patterns. But it seems plausible that we are approaching some significant changes. Without trying to predict much, and being no expert on streaming tech, I still thought I’d try to think through some ideas about the state of streaming and its historical significance.

An interim report

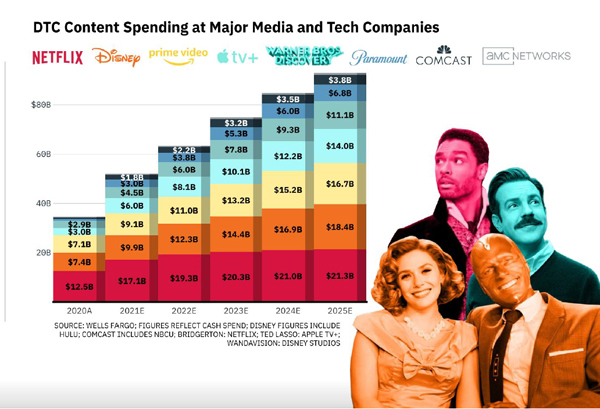

The Future of Content, Variety Intelligence Platform April 2022, p. 10.

Best to start with some basic information. Here’s what I came up with, all subject to correction and nuancing.

Streaming is now firmly established as a distribution/exhibition platform. It’s now the focus of all major US media conglomerates and it’s a market force every independent producer and company must reckon with. Broadcast television is waning. Viewership is declining, and this year saw a ten-year low in the number of pilot shows ordered by the networks. Cable subscriptions are likewise plummeting. Over the last ten years, cable channels lost 30-50% of viewers. Only the Discovery channel managed to grow, and live sports (e.g., ESPN) hung on, though damaged by the pandemic. Globally, streaming is growing rapidly, with both Hollywood majors and national and regional media firms plunging in.

Theatrical film, severely curtailed by the pandemic, is staggering. In nearly every country of the world, 2021 attendance was half or less that of 2017-2019. Studios are now releasing far fewer features, even in the crowded summer months. About 1000 theatre locations have not reopened since early 2020. Los Angeles has lost the Arclight and Pacific Theatres chains and the Landmark Pico theatre. In my home town a five-screen second-run house shuttered during the pandemic, and a six-screen multiplex is rumored to close soon.

As Lucas and Spielberg foresaw, the films that fill multiplexes are blockbuster franchises. So far this year, Spider-Man: No Way Home and Dr. Strange in the Multiverse of Madness have done robust business, and exhibitors confidently expect big turnout for Top Gun: Maverick and Jurassic World Dominion. The surprise success of Everything Everywhere All at Once ($47 million box office) doesn’t mitigate the bleak prospects for most offbeat theatrical fare. Prestige films, romantic comedies, arthouse films, and many genre pictures can’t usually yield big enough returns, and the aftermarket–cable, DVD, and other ancillary outlets–which helped support them in the past scarcely survives.

Which leaves streaming as a primary source of filmed entertainment. At least 86% of US households access streaming services, either by subscription (SVOD) or as ad-supported services. The result is an immense amount of choice. You can browse studio libraries, imports, straight-to-streaming features (e.g., the latest Pixar releases) and series (e.g., Inventing Anna, Tokyo Vice).

Except for Netflix, Amazon Prime, and Apple+, the major streaming services are aligned with US entertainment conglomerates. Indeed, streaming made Netflix and Amazon entertainment behemoths, as attested by recent Academy Awards and Emmys.

Exact figures fluctuate, but the principal subscription streamers vary enormously in scale. At the beginning of this year, pre-meltdown, Netflix declared a global subscription base of about 220 million, with Disney+ at 196 million. Paramount claimed about 56 million (incuding Showtime and other offshoots), Discovery 22 million, and Peacock 24.5 million, including both paid and free. According to Amazon, over 200 million Prime members streamed material in 2021. As of March, Apple+ was estimated to have 25 million paid subscribers, with about twice that number benefiting from access via promotions (e.g., purchase of Apple hardware).

The simultaneous theatrical/streaming release (Dune, Wonder Woman 1984) is becoming rare as audiences return to theatres, but it remains an option (e.g., Firestarter). More common is a strategic delay far less than the usual ninety-day window that was common before the pandemic. The Batman opened in multiplexes on 4 March and was streaming 18 April. Universal and Paramount are prepared to send a feature online 17 days after theatrical release.

Fickle audiences and fluctuating “content” create churn. As a monthly subscription transaction, paid streaming lets consumers depart at will. Canceling cable subscriptions was difficult due to long-term contracts and obstreperous bureaucracy. Unsubscribing to Netflix or Apple+ is a lot easier. In addition, cable programming had a considerable stability, with long seasons and evergreen attractions. Studios signed extensive licenses for films and series, since cable was a perpetual money machine. Moreover, a movie might be available on several cable outlets. Now, however, the streaming industry faces audience churn.

Defections are common, especially among the young. An April survey found that nearly a third of Gen X subscribers and nearly half of Millennial and Gen Z subscribers have both added and dropped at least one streaming service in the last six months. Overall, nearly a third of subscribers say they have canceled at least one service in the same period. Web-experienced viewers are adept at hopping onto and off the latest thing.

Churn is accentuated by the exclusivity of the new media oligopoly. As the majors discovered the money to be made, they regained control of their library licenses. Netflix had The Office, its most popular attraction, until Warners took it back in 2019–soon after Netflix had renewed it for $100 million. The turnover is ongoing: this month Netflix lost Top Gun, the Ninja Turtles, the Muppets, Marvel TV series, and the first six seasons of Downton Abbey. The majors have gradually reasserted the exclusivity of their product.

As competition has intensified, streamers have been forced to acquire their own programming, both films and series. The pool must be refreshed to retain current subscribers and attract new ones. The problem is that once the new material has run its course, viewer loyalty can wane. This is especially true when the streamer dumps a full season of a series for bingeing: it encourages newcomers to sign up briefly and then defect. Disney has executed a powerful balancing act between legacy material and new offerings (Pixar features, Marvel spinoffs) that keep audiences faithful.

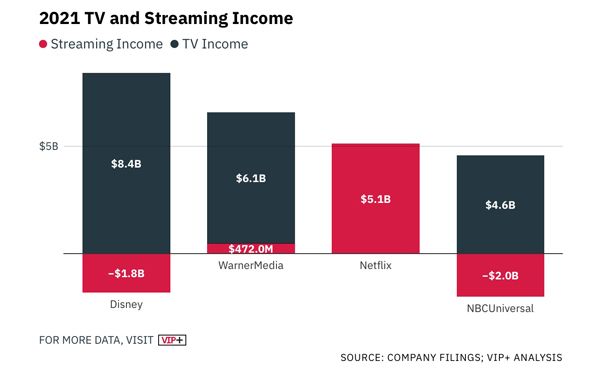

Streaming is not yet profitable. Broadcast and cable television are far more lucrative because they gain revenue from advertising and fees. Disney and Universal each lost about$2 billion on streaming in 2021.

Hence the concern over Netflix’s April report of decline in subscriptions. Streaming is its core business. A loss of $2 billion for the Disney conglomerate (parks, cruises, ABC TV, etc.) amounts to a rounding error. The majors’ deep pockets can sustain streaming enterprises for some time, but Netflix is far more vulnerable.

The streaming services are investing huge amounts in new “content.” The major providers are estimated to spend $50 billion acquiring projects this year. Producers are in a powerful position to demand big budgets to outmatch the competition. The costs are exacerbated by the high demands of talent, who now expect to be paid largely up front, since there is little opportunity for the deferred fees and back-end deals that depend on ancillary revenue.

No wonder then that several services have raised subscription rates. More drastically, in its current crisis Netflix has announced plans to offer an ad-supported tier of the sort already provided by Universal/NBC’s Peacock. Other services, Disney included, will probably shift to a similar option, especially since there is some evidence indicating that consumers will accept commercial interruptions in exchange for lower fees. Netflix also plans to control password-sharing, which helped it grow recognition but in the face of intense competition depletes its audience. It may be harder to combat the use of virtual private networks, aka VPNs, which allow roundabout access to region-based offerings.

One monetization strategy seems to be the rebirth of windows. Once a high-demand film is released to streaming, the service can add an upcharge for accessing it. Blockbusters like The Batman and the new Spider-Man trilogy were launched online with an extra fee for initial viewing. Over time, the prices fell gradually, just as in the old first-run/ second-run days. Even classics can benefit from premium treatment: The Godfather is free on Paramount+, but a rental costs $3.99 on Amazon Prime and Apple+. Arthouse fare is even more privileged; I paid $19.99 to see Drive My Car in its online release, though now it’s free on HBO Max.

It’s still TV

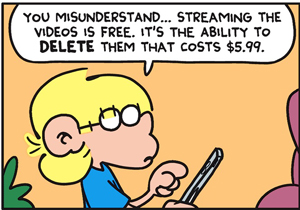

Bill Amend, Foxtrot.

In the late 2000s, streaming video entertainment was the province of mostly smallish, scattered companies like Twitch, Pluto, and others. Netflix and YouTube also took the plunge. Hulu, a consortium of Fox, Universal, and Disney, represented the majors’ initial effort to explore the market. As download speeds improved, problems with buffering and latency were overcome by new streaming protocols.

Soon enough, a familiar cycle emerged. Tim Wu’s book The Master Switch shows that mass information technologies (telegraph, telephone, film, TV) tend to consolidate into oligopolies. Major companies buy or kill off the competition. This happened with streaming, as one by one the big players came to the foreground. Netflix had early-mover’s advantage, having pioneered the distribution of DVDs by mail, and Amazon had a massive customer base in place already. The studios had helped Blockbuster wipe out small video-store chains, which had demonstrated the existence of a massive market, then turned their attention to selling discs directly to consumers. In 2019 the big players began to consolidate control over the expanding streaming landscape.

By acquiring other services (e.g., Paramount’s buying Pluto) and assembling proprietary components already in hand (e.g., WarnerMedia’s repurposing HBO Go), the firms have come up with integrated platforms. Disney+ launched in 2019, Peacock and HBO Max in 2020. Discovery+ and Paramount+ appeared in 2021, and Amazon bought MGM earlier this year. Sony, while licensing its film releases to its counterparts, has focused on animation by picking up Crunchyroll, which will absorb Sony’s Funimation service.

It’s early in the game, and it will take time for the companies to reassemble libraries that have licenses yet to expire. Doubtless many titles will be available for premium rental on rival sites, since no company wants to leave money on the table. Still, it seems clear that a considerable siloing of “content” will enable firms to enhance their power over their intellectual property. From this standpoint, we can think of streaming as a new phase in the development of home video.

In the earlier entry, I argued that home video formats gave the consumer a great deal of freedom. Even cable promoted “appointment viewing,” but tape, and then DVD, allowed the consumer a lot of flexibility. You could buy or rent a movie and watch it when you pleased. You could copy it too. Convenience is always a plus in a consumer item, and home video added to it a welcome price point: renting a tape or disc was cheaper than buying a movie admission, and in discount bins you could find a DVD for a few bucks.

With physical media, movies became manipulable by the audience. Ripping a DVD yielded a file that could be remade. Mashups, Gifs, and other transformations were feasible. Video essays changed film studies, and satire, homages, and fan analyses filled the internet. You could play with your movies.

Streaming withdrew this flexibility but offered greater convenience. A platform combines the array of a video store (think of those tiled pages as display racks) with push-button access. You still have the option of time-shifting, and you can share home viewing with others. But there’s no longer a physical medium. You don’t own or rent the film as object; you have bought access to it as a display, and only when you’re online. (“Buying” a digital copy is no guarantee of possession, if the service loses its license to the title.)

For decades, movie exhibition was a service business. We paid for the experience. Briefly, between 1980 and 2020, films became consumer artifacts as well. Ordinary folk enjoyed the sense of possession shared by film collectors of earlier decades. But with the decline of discs, we are once more paying for the experience while the object lies elsewhere.

Because of Hollywood’s preternatural fear of piracy, turning the artifact back into a service is a way to secure intellectual property. Not that people will stop trying to make personal copies. It’s possible to record streaming transmission, but the majors are counting on several factors. Just as people became tired of piling up DVDs they probably won’t watch, they could tire of filling hard drives with rips.

A few hardcore headbangers will enjoy sticking it to the man, but most people will reckon if you already pay for streaming the movie, why copy it? Given customer inertia and the convenience of streaming, why bother to pirate a movie that’s probably on streaming somewhere, available whenever you want? The trouble and expense of ripping may be greater than simply signing up for another subscription service. There are certainly overseas markets for pirated streaming shows, but as the companies expand their platforms abroad, piracy may diminish.

In sum, streaming has become the next step in the majors’ reassertion of control over their IP. It surpasses the old video store’s inventory, offers the convenience of click-ordering and time-shifting, and retains the advantages of in-home consumption. All we relinquish is ownership of a copy. Now that SVOD services are generating new attractions, providing long-running series with spaced-out hour-long episodes, and exploiting advertising-supported tiers, we are getting a version of fully on-demand cable TV.

We can glimpse this prospect in the demand for bundling, or aggregation. Customers’ biggest complaint is that there’s too much choice. The 200 channels of maximal cable are dwarfed by the streaming torrent. Nielsen estimates that as of last February there were 817,000 unique program titles available. Hence the emergence of streaming MVPDs, the “multichannel video programming distributors.” They provide a mix of movies, broadcast network series, classic TV, sports, and cable news. The best example is YouTube Live, which charges $64.99 per month, far beyond most of its SVOD competitors and reminiscent of classic cable fees. Yet YouTube Live is the most popular MVPD.

Add to this the number of FAST outlets, free ad-supported streamers such as Pluto, Tubi, Roku, Freevee, et al. With MVPDs these already constitute about a third of streaming offerings. One survey found that 34% of US consumers would prefer a free streaming service with 12 minutes of ads per hour. Streaming is starting to look like. . . well, just good old TV. The free platforms approximate broadcast TV, and the paid ones are cable reborn.

It takes time to make a classic

Atom Egoyan, Artaud Double Bill (2007).

Streaming demands a constant flow of new material, compared with the relative stability of broadcast TV, so the problem has been how to release it all. Netflix made a splash by dumping entire seasons at once, encouraging bingeing and getting immediate buzz and uptake. Viewers came to expect the big gulp. One survey found that over half of viewers under sixty now want firms to provide all the episodes of a series at once. But this strategy can damage long-term subscriptions by encouraging churn.

It also makes the product forgettable. Most direct-to-streaming films have a short shelf life. Does anybody watch War Machine (2017) or Bird Box (2018) now? Most auteur efforts seem to me to have had little cultural impact, not even Scorsese’s The Irishman (2019, with a mild theatrical release as well) or Soderbergh’s The Laundromat (2019). They came and went fairly quickly. A rolled-out theatrical film had an afterlife, it could circulate through the culture in many ways, and it could find niche audiences. Could The Godfather (1972) have its standing today if it were released straight to SVOD? Are there now “classic” streaming features?