Archive for the 'Tableau staging' Category

Watching movies very, very slowly

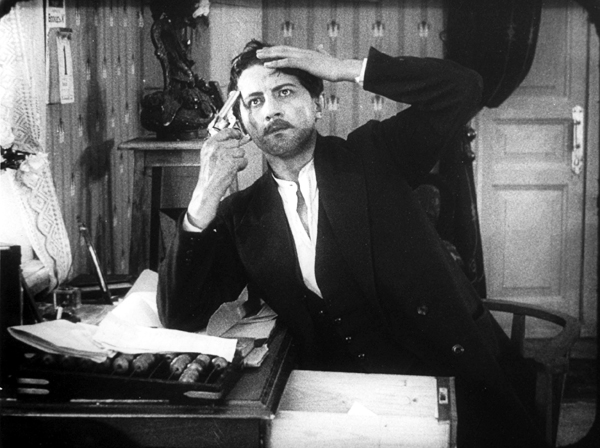

Children of the Age (1915).

DB here:

Before DVD and consumer videotape, how could you study films closely? If you had money, you could buy 8mm or 16mm prints of the few titles available in those formats. If you belonged to a library or ran a film club, you could book 16mm prints and screen them over and over. Or you could ask to view the films at a film archive.

I started going to film archives in the late 1960s, when they were generally more concerned with preserving and showing films than with letting researchers have access. Over the 1970s and 1980s this situation changed, partly because several archivists grew hospitable to the growing field of academic film studies.

I started going to film archives in the late 1960s, when they were generally more concerned with preserving and showing films than with letting researchers have access. Over the 1970s and 1980s this situation changed, partly because several archivists grew hospitable to the growing field of academic film studies.

At first archives found it easier to screen films for researchers in projection rooms, but eventually many let visitors watch the films on stand-alone viewers. That way the researcher could stop, go forward and back, and take notes. In researching my dissertation in the summer of 1973, I watched films at George Eastman House in 16mm projection, but a few weeks later in Paris, Henri Langlois of the Cinémathèque Francaise allowed me time on Marie Epstein’s visionneuse (a term I’ve admired ever since).

Over the years Kristin and I have visited archives in various countries. We’ve become particularly close to the Royal Film Archive of Brussels, partly because back in the 1980s the head, Jacques Ledoux, believed that Kristin’s research was worthwhile and allowed us to visit regularly. Without the cooperation of Ledoux and his successor Gabrielle Claes, we couldn’t have done a great deal of our research. No wonder it helped us so much: the Belgian Cinémathèque is arguably the most diverse archive in the world.

Case in point: My current visit. I came with two goals. First, I had to prepare for my lectures in Bruges later in the month. These consist of eight talks on anamorphic widescreen. So I planned to watch four early CinemaScope films, plus Oshima’s The Catch (1961) and the SuperScope version of While the City Sleeps.

I also wanted to fill in a big gap in my knowledge about a major silent filmmaker. More on him shortly.

Viewing on a visionneuse

If you’ve never watched a film on a viewer, let me explain. The classic viewer is a flatbed, or viewing table. It’s the size of an executive desk. Two platters or spindles hold a feed reel and a take-up reel. Motors drive the film through a series of sprocketed gates, past a projection device (usually a prism) and across a sound head. The film appears on a smallish screen. There’s usually a little surface space to set a notepad, along with a lamp on an articulated arm.

Before digital editing came along, such machines offered the only way filmmakers could cut sound and picture. (Now most phases of editing are done on computer, with physical editing reserved for late stages of postproduction.) Eventually flatbeds were offered in simpler versions for playback rather than editing.

The most common American-made viewer was the Moviola, which was initially not a flatbed but an upright machine. Eventually the German Steenbeck and KEM became the high-end standards for editing picture and sound. The Brussels archive relies on the Prévost, an Italian machine that is very easy to maintain. The Prévost, seen above, beams the image from the prism onto a mirror hanging over the machine, which bounces the picture onto the screen.

35mm films are mounted on 1000- or 2000-foot reels, the latter yielding about twenty minutes of film at sound speed. A feature film will consist of four or more 2000-foot reels. Even if you watch a film straight through, without stopping to make notes, it takes time to change the reels, so a two-hour movie will probably consume nearly three hours on a 35mm flatbed. And of course researchers stop a lot to take notes and move to and fro across a scene. If I’m studying a film intensively, I probably consume about an hour per 2000-foot reel. Across my life, I wouldn’t dare calculate how many months I’ve spent in visionneuse viewing.

Viewing on an individual viewer has both costs and benefits. Sometimes details you’d notice on the big screen are hard to spot on a flatbed. But with your nose fairly close to the film, you can make discoveries you might miss in projection. (Ideally, you would see the film you’re studying on both the big screen and the small one.) In addition, of course, you can stop, go back, and replay stretches. Above all, you get to touch the film. This is a wonderful experience, handling 35mm film. Hold it up to the light and you see the pictures. You can’t do that with videotape or DVD.

The scary part of any flatbed viewing, at least for me, is watching the film whiz along under your nose at ninety feet per minute. If you haven’t threaded the thing properly, or if the print has a weak splice or torn sprocket hole, you can rip the film. For this reason, archives typically don’t allow a researcher to handle films they hold in only one copy.

The average film you watch on a flatbed has an optical soundtrack, that squiggly line that is read by an optical valve. But early CinemaScope films had magnetic tracks so that they could provide stereophonic sound. In the picture below you can see that strips of magnetic tape, like those in tape cassette players, run along both edges of the film strip. For my Scope films, I was obliged to use a Prévost that could handle mag sound–and of course one that could be fitted with an anamorphic lens to unsqueeze the image to the proper proportions.

Hell on Frisco Bay (1954) was a color movie, but this print, like many from the period, has faded to bright pink. The Eastman color stock of the period was unstable, and many prints were processed carelessly. (In unsqueezing the frame, I’ve eliminated the color cast for better clarity.) Restoring color to films of this period is one of the major tasks facing film archivists. Cinema is a fragile art form.

Hours and hours of Bauers and Bauers

At the Giornate del Cinema Muto in Pordenone in 1989, Yuri Tsivian’s retrospective on Russian Tsarist cinema convinced a lot of us that good filmmaking in that country didn’t start with the Bolshevik revolution. Along with that retrospective came a wonderful book, Silent Witnesses, edited by Yuri and Paolo Cherchi Usai. Unfortunately hard to find now, it’s filled with information about pre-Soviet filmmaking.

Although I enjoyed the Tsarist films, I didn’t know exactly what to watch for. It took me some years to appreciate their artistry, and some of my ideas about them showed up in On the History of Film Style (1997) and Figures Traced in Light (2005). In those places I studied 1910s “tableau” staging and used some examples from Yevgenii Bauer, by common consent the most pictorially ambitious Russian director of the period. Kristin and I also used Bauer as an example of tightly choreographed mise-en-scene in Film Art (p. 143). I thought it was time I examined his work more systematically, and I knew that the Royal Film Archive held some Bauer prints, which they acquired from Gosfilmofond of Moscow.

Bauer had a brief but prolific career. He started directing in 1912 and completed eighty-two films before his death in 1917. Unhappily, only twenty-six of his works survive. Just as bad, most of those lack their original intertitles, so we don’t have the expository and dialogue titles we expect in silent films. The placement of the titles is sometimes signaled by two Xs marked on two successive frames. Without titles, the storylines can get obscure. Yuri, Ben Brewster, and other scholars have sought to reconstruct something approximating the original titles by studying the plays and novels that Bauer adapted. Three of the reconstructed films are available on a DVD called Mad Love, and Yuri has also created an innovative CD-ROM (right) that takes us through works of Bauer and his contemporaries.

Bauer had a brief but prolific career. He started directing in 1912 and completed eighty-two films before his death in 1917. Unhappily, only twenty-six of his works survive. Just as bad, most of those lack their original intertitles, so we don’t have the expository and dialogue titles we expect in silent films. The placement of the titles is sometimes signaled by two Xs marked on two successive frames. Without titles, the storylines can get obscure. Yuri, Ben Brewster, and other scholars have sought to reconstruct something approximating the original titles by studying the plays and novels that Bauer adapted. Three of the reconstructed films are available on a DVD called Mad Love, and Yuri has also created an innovative CD-ROM (right) that takes us through works of Bauer and his contemporaries.

Although he made comedies, Bauer is most famous for his somber psychological melodramas, often centering on class exploitation. A woman becomes a rich man’s mistress; when she abandons her husband and takes their baby, he commits suicide (Children of the Age). A serving maid is seduced by her master and callously tossed aside when he marries a flirt (Silent Witnesses). Things can get pretty dark. This is the director who made films entitled After Death (1915) and Happiness of Eternal Night (1915). In Daydreams (1915), a widower sees a woman who strikingly resembles his dead wife. Like Scottie in Vertigo, he follows her and becomes increasingly obsessed. Did I mention that he keeps a ropy braid of his dead wife’s hair in a glass box?

Seeing several films again confirmed my view that Bauer knew better than most directors how to organize a shot. His contemporary Louis Feuillade favored a quiet, sober virtuosity, but Bauer developed a flashy visual style. He’s most known for his ambitious use of light (Frigid Souls, below) and big, textured sets packed with columns, trellises, drapes, brocades, embroidered pillowcases, and other elements that add abstract patterns to a scene (Children of the Age, below).

Even a hammock can be stretched and framed to create a swooping web around the innocent heroine of Children of the Age, ensnared by the demimondaine.

In particular, I admire Bauer’s constant inventiveness in moving his actors around the set in smooth ways that always direct our attention to what’s happening at the right moment. European directors of this period seldom cut up a scene into several shots of individual actors; the frame typically shows us the entire playing space. Directors were obliged to shift their actors across the frame and arrange them in depth, like chesspieces.

This master-shot, single setup approach might seem hoplelessly restrictive. Today we expect films to have lots of cutting and camera movement. How does the filmmaker sculpt the action, moment by moment within a static frame?

Blocking, as in blocking the view

I trace some principles of this approach in the books I already mentioned. I’ll mention two strategies here, and if you want to know more you can follow up in On the History of Film Style and Figures Traced in Light.

Filmmakers of the 1910s created intricate choreography by moving actors left or right, up to or away from the camera. Often they set up unbalanced compositions and then rebalanced them, creating a kind of spatial tension that parallels the drama. In the course of the action, actors close to the camera might conceal those that are farther away. The blocking of the actors, in other words, also sometimes blocks our view.

In Leon Drey (1915), Bauer tells the story of a cynical womanizer. In one scene, he’s dallying with his latest conquest when another of his lovers bursts into his apartment. The first phase of the shot is very unbalanced; most directors would have put the mistress at the door on one side of the frame and Leon and the woman in his arms at the opposite side. Immediately, though, the woman flees to the bed in the back of the shot and activates the right area of the frame.

As the mistress rushes to the woman in the rear, Leon strides to the foreground and his burly body blots out the drama between the two women. We’re forced to concentrate on his cold indifference to both of his lovers. Eventually his mistress comes to the foreground to remonstrate with him. Now, at the high point of the scene, we have a balanced frame. Note that Leon continues to conceal the first woman; the scene’s not yet about her.

The mistress leaves, angry and desperate, and Leon placidly pays her no mind. As the door closes, he hurries to lock it and summons the first woman, now visible, back from his bed. He will have little trouble convincing her to return to his arms.

The dramatic curve of the scene has been expressed in compositional asymmetry and symmetry, concealing space and then opening it up.

Most directors of the period used principles like these to turn dramatic conflict into vivid choreography. Bauer also tried more unusual tactics. He was especially good at shifting actors’ heads very slightly to open or close off channels of action behind them. Here’s an instance from Her Heroic Feat (1914).

The butler informs Lina and her mother that the scandalous ballerina Klorinda is calling on them. At first Lina’s head is solidly blocking the doorway in the rear. As the butler goes to the rear door, Lina pivots a little to clear our view of that doorway.

Klorinda sashays in, and who could miss it? She’s wearing a bright dress, she’s centrally positioned, and she’s moving toward us. The other women refuse to look at her, but their immobility assures that we keep our eye on Klorinda. When she stops to greet them, then they move, pivoting away; Lina’s head goes back to blocking the doorway. Imagine how things would have gone if her head had been there when Klorinda appeared in the background.

Of course, we should also study the performance techniques of Bauer’s actors–a subject examined in a fine book by Ben Brewster and Lea Jacobs, Theatre to Cinema. The compositional tactics employed here work to draw our attention to the actors’ expressions and body language.

Still, not everything in 1910s ensemble staging owes a debt to the theatre. The changes in Lina’s head position, or Leon Brey’s calculated blockage of the women behind him, wouldn’t work on the stage; most of the audience wouldn’t see the exact alignment we get onscreen. Live theatre depends on varying sightlines, but in cinema, we all see the action from one position, that of the camera. Bauer, Feuillade, and their contemporaries realized that they could organize the action, down to the smallest detail, around what the camera could and could not take in.

The fluent choreography developed by 1910s directors is almost unnoticeable when you’re watching in real time. You’re supposed to register the what–the point of interest in the frame–rather than the how, the slight shifting of actors that highlights this face, then that gesture. By the time you realize that something has happened, the first stages of the process have slipped away, inaccessible to memory.

So there’s a need for slow viewing. Filmmakers have thousands of secrets, many that they don’t know they know. Sometimes we have to stop the movie, go back, and trace precisely how directors achieve their effects. Really slow viewing can help us discover how deep film artistry can be. All hail the visionneuse and the archives that allow scholars to use her.

For background on Bauer, see William M. Drew’s excellent career survey. I discuss Bauer’s relation to narrative painting in another blog entry.

In production and distribution of the period, the titles and inserts (close-ups of newspapers or messages) were sometimes stored on separate reels. In many cases, only the image reels have survived.

Several other Bauer films are available on Milestone’s invaluable DVD set Early Russian Cinema.

Professor sees more parallels between things, other things

An Onion report brought to my attention by Stew Fyfe celebrates the comparative method (“Professor Sees Parallels between Things, Other Things”). I confess myself an admirer of this approach. We can learn a lot by setting two things alongside one another. It’s even better if we have a reason to do so.

I thought about this when Kristin and I visited the Auckland Art Gallery in May. Their modern wing was hosting an intriguing Triennial show called Turbulence, an array of contemporary work, but I was more drawn to the Museum’s traditional collection. I saw a very nice Brueghel (he’s one of my favorites) and an arresting Adoration of the infant Jesus, painted by the rather minor Francisco Antolinez y Sarabia (1644-1700).

Though indifferently painted, it reminds me of El Greco in its tipped, piled-up figures. I enjoyed the acrobatic Madonna: Is she crouching, leaping, or tripping? It recalls Eisenstein’s point that much classic art creates impossible contortions which suggest various stages of movement, a point I discussed in a blog last year.

To get to those parallels: We wandered through the Gallery’s sturdy collection of British art and I was once again captivated by narrative painting of the late nineteenth century. Paintings have long been assigned the task of telling stories, but usually those stories were already well-known to the viewers, drawn as they were from history or mythology. In what’s come to be called “narrative painting,” the stories seem to be taken from life, although they’re really invoking our knowledge of prototypical situations.

Without the advantage of easily recognized religious or mythological tales, such pictures usually rely on a title to coax us fill in the story. The title specifies the context for the concrete action we see. For example, two prosperous young women are sitting in a garden. One is reading from a sheet of paper. What’s going on?

The title, Her First Love Letter, helps us zero in on specific aspects of the action and fill in the situation. The girl on the left, bathed in light, leaning forward eagerly and wearing the pale frilly dress, can be seen as the more inexperienced of the pair, caught up in the anticipation of the young man’s ardor. The more worldly woman sits relaxed, perhaps a little skeptical but also tolerant of the ways of young love. You can’t see it in reproduction, but the flower in the darker woman’s bosom is a mere spatter of paint, the brightest bit of red in the picture. The painting is by Marcus Stone and dates from 1889.

Narrative paintings like this are evidently one source of early cinema’s approach to staging and composition. This “full shot” somewhat recalls the sort of thing we see throughout European filmmaking of the first twenty years. Staging the action on more or less the same plane, viewing from a distance characters grouped around a table, is very common at the time.

Another picture can teach us a bit about acting.

Here the body language and facial expressions yield hints. The man sits casually, the woman more rigid, and his arm is not quite brushing hers. Absorbed in his book, he seems unaware she’s there. She sits stiffly, with downcast eyes and an expression that seems stoic. You can even take her slight unfolding of the colorful shawl as an invitation to the touch that he doesn’t offer.

This painting, by Walter Sadler, is called Married (undated but presumably turn of the century). Once the title tells us that the couple are husband and wife, we can infer that their passion has subsided, largely through the husband’s self-absorbed inattention. Did he really need to take three books into the garden? The single-word title also lets us see certain elements as iconographic clues. The woman’s white dress and bouquet recall the wedding, and the fallen badminton birdie and racket suggest an earlier time when they played together. Kristin sees sexual symbolism in the flowers in her lap and the books in his. The gallery’s caption suggests that the turtle is going off to hibernate and that the blocked-off back garden suggests no future for the relationship.

Putting aside the symbolic connotations, though, the strong cues supplied by the figures’ postures and expressions point us toward the sort of slight changes in body language provided by acting in early cinema. Some viewers think that early film acting was expansive and overblown, but that’s not always the case. Here is an instance from Evgenii Bauer’s Twilight of a Woman’s Soul (1913), in which Vera starts to confess an indiscretion to her admirer Prince Bol’skii. She raises her hands , an obvious indication of her anxiety, but more subtle is what’s going on below. At first her legs are turned toward him, but as she lifts her hands they shift a bit further away from him. Her small adjustment of her torso is a kind of accompaniment of the hand gesture, like a harmonic change accompanying a melody.

Both Her First Love Letter and Married lay their figures out along a line perpendicular to the viewer, a common strategy in early film. I discuss this in Figures Traced in Light; for other examples, see figs. 2A.7-11 here. The alternative is to arrange figures in depth, and one of the jewels of the Auckland collection illustrates this nicely. The title is more allusive than our others: For of Such Is the Kingdom of Heaven (1891), a reference to Jesus’s admonition to let children come to him (Matthew 19:14). The painter is Frank Bramley.

We are watching the funeral of a child, with the family carrying the almost weightless casket, swathed in flowers. In the picture’s suggestion of solemn movement, we might be tempted to say, we find early cinema before cinema. More to my point, though, is the way in which a diagonal layout creates a play between strong composition and rich ancillary effects.

The picture is composed along two lines, with the adult mourners grouped at the point where the procession intersects with the horizon. That horizon is given a widening sliver of light, a rolling wave that accentuates the heads of the two women right of center. The central bright patch of grays, whites and pastels is set off against the earth tones of the docks and the robust but respectful working-class onlookers. At the peak of the picture, the crowning moment of the angle formed by horizon and pier, is the bowed black head of the father.

The depth composition also guides our visual search, allowing us to discover a great variety of postures and facial views. The little girls in the center stride and sing from their hymnals dutifully, while the girl in the straw boater, bearing a huge bouquet, is staring at us—a disturbing effect, since her face is unhealthily gray. Will she be another victim?

In the years after 1908 or so, many filmmakers adopted the diagonal layout as a dynamic way to play out scenes. Here’s an instance from Bauer’s Twilight of a Woman’s Soul. Vera is calling on a men’s club where they practice fencing and pistol shooting. They put on a show for her.

The diagonal draws our attention to the target, but Vera’s contrasting bright costume and her tilted face are further accented by putting her at the opposite end of the vector. All these factors make sure we note that her eye is on the handsome marksman, Prince Bol’skii. Receding compositions like this offered 1910s filmmakers a way to guide visual search in ways similar to Bramley’s painting.

Even more intriguing to me in For of Such Is the Kingdom of Heaven is the figure who’s evidently the dead child’s mother. She is bowed and tucked away to the right of the husband and behind two pallbearers. Bramley has taken advantage of the diagonal view to mask her off, as if viewing her grief would be too great for us to bear. This device has a parallel in cinema too.

A film scene unfolds in time, unlike a painting’s action. So filmmakers can block certain parts of the action and then, at the proper moment, reveal it. If Bramley were working in film, he could arrange his cortege so that the mother’s face came gradually into view as the group advanced, creating both a dramatic and pictorial climax. This blocking-and-revealing tactic is common in the choreographed staging we find in 1910s films, and again Bauer’s Twilight of a Woman’s Soul offers a nice illustration.

Vera, now ill, is visited by her suitor Prince Dol’skii. Her parents object, but she begs her father to let him in, and he reluctantly agrees. As the action starts, she clutches her father as the doctor looks on. The men’s bodies mask a doorway in the background, and as a servant comes through it, they pivot, revealing him.

I’d argue that the servant’s entrance primes this area of the shot for the dramatically important entrance, that of Dol’skii. The father, the doctor, and the servant withdraw toward the back wall. After a pause, the Prince enters and advances.

Vera greets him warmly as he takes the father’s place in the shot.

I’m not arguing that these particular paintings influenced filmmakers, only that the principles that the painters employed were picked up by directors. The more general point is that in understanding film aesthetics, we can usefully compare movies to other movies, and movies to other arts. By doing this, we sharpen our sense of what various media can do. The professor in the Onion story wisely notes, “It’s not just similarities that are important, though—the differences between things are also worth exploring at length.”

All paintings shown here are in the permanent collection of the Auckland Art Gallery. Bauer’s film is available on a Milestone DVD. I hope to blog more about his work later this summer.