Archive for the 'Tableau staging' Category

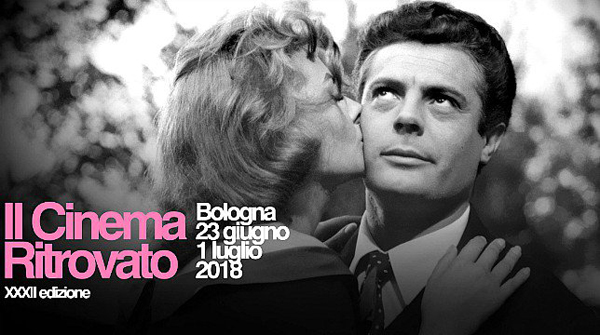

Bye bye Bologna

Lucky to Be a Woman (1955).

DB here:

How to sum up nine days of Cinema Ritrovato? I logged thirty-two features and half as many shorts and fragments, along with a few panels and workshops. Fate cursed me with the need to blog and to sleep, so I missed many prime items. And that’s including my (sad) decision not to revisit films I’d already seen, so I sacrificed new exposure to masterpieces from Ozu, Mizoguchi, Feuillade, Leone, de Sica, etc.

In this last Bologna roundup, all I can do is wave at some of the surprises and discoveries that captivated me.

Many of my pals praised the Mexican noir Western Rosauro Castro (1950), which I had to miss, but I did get compensated by Prisioneros de la Tierra (1939), an Argentine classic of romantic realism. The plot concerns the exploitation of peasant migrants forced to work in dire conditions. One scene, of a drunken doctor in the throes of the DTs, got a rise out of Jorge Luis Borges.

Even more shocking was the red-light melodrama Víctimas del Pecado (1951, above) by the great Emilio Fernández. A newborn baby dumped into a garbage can; a preening, sadistic pimp who can smoke, chew gum, and dance frantically at the same time; a nightclub dancer who tries to live righteously but winds up in prison for her pains; and several splashy music numbers–who could resist this? Not the Bologna audience, who burst into applause when, after slapping a child silly, said pimp got a quick and violent comeuppance. Of course the gorgeous cinematography of Gabriel Figueroa contributed a lot: One shot of a train blasting black smoke into the night would be enough to exalt a far less delirious movie.

Thanks to Dave Kehr of MoMA, who brought a sampler from his recent Fox retrospective, and to UCLA and other sources, aficionados of American studio cinema had no shortage of delights. Monta Bell’s Lights of Old Broadway (1925) gave Marion Davies a dual role as twins separated at birth and she made the most of half of it, playing a no-nonsense colleen who makes it big at Tony Pastor’s. Part of the fun was the film’s historical references: Teddy Roosevelt as an undisciplined schoolboy, Weber & Fields as a kiddie act, and a solicitous Thomas Edison urging the heroine to invest in electricity.

Ten years later, One More Spring (1935, above) from Henry King offered a gentle seriocomic Depression tale. Two homeless men squatting in a garage take in a woman who sleeps on the subway, and they try to make ends meet with the help of a kindly old couple. At first engagingly episodic in the McCarey manner, the plot gets more tightly bound when the old couple faces the loss of their savings. Janet Gaynor is endearing, as usual, and Warner Baxter brings his clipped energy to the role of a hopelessly optimistic failure. There are no villains. The banker struggles to save his depositors, though he’s frank enough to admit, “It’s all the fault of the Republicans. Still, I’ll vote for them in the next election. With the Democrats you never know what to expect.” Another big laugh from the crowd around me.

That Brennan Girl (1946) exemplified the opportunities that the boom in 1940s moviegoing offered downmarket studios. Apart from the second-tier cast and the warning “Not Suitable for Children,” the production’s B-plus aspirations were clear, yielding a surprisingly polished Republic picture (buffed up by a beautiful Paramount restoration). A woman raised by a predatory mother takes up petty theft and con games. She reforms, but after becoming a war widow she falls back into her old ways–endangering her baby in the process. That Brennan Girl could have served as an example in my Reinventing Hollywood book, since it flaunts a long flashback punctuated by dreams and bits of imaginary sound. Those narrative stratagems pervaded films at all budget levels.

That Brennan Girl (1946) exemplified the opportunities that the boom in 1940s moviegoing offered downmarket studios. Apart from the second-tier cast and the warning “Not Suitable for Children,” the production’s B-plus aspirations were clear, yielding a surprisingly polished Republic picture (buffed up by a beautiful Paramount restoration). A woman raised by a predatory mother takes up petty theft and con games. She reforms, but after becoming a war widow she falls back into her old ways–endangering her baby in the process. That Brennan Girl could have served as an example in my Reinventing Hollywood book, since it flaunts a long flashback punctuated by dreams and bits of imaginary sound. Those narrative stratagems pervaded films at all budget levels.

Another 1940s technique was the chaptered or block-constructed film, Holy Matrimony (1943), a genial comedy about switched identities, contains sections with titles like “But in 1907” and “And so in 1908.” The film, about a painter brought back to London from his tropical hideaway, reworks the Gauguin motif made famous by Maugham’s Moon and Sixpence (1919). Was this release an effort to build on Albert Lewin’s 1942 version of the novel? Monty Woolley plays himself, but Gracie Fields brought real warmth to the clever, ever practical woman who marries him.

Holy Matrimony was a welcome, if minor entry in the John Stahl retrospective. I had to miss the much-praised When Tomorrow Comes (1939) but was happy to break my rule of avoiding things I’d seen before when I had a chance to revisit Imitation of Life (1934). I persist in thinking this better than the Sirk version, not least because of its harder edge. Beatrice Pullman’s exploitation of her servant Delilah’s pancake recipe carries a sharp economic bite, and the brutal classroom scene yanks our emotions in many directions. (While Peola writhes in her seat, her mother asks innocently, “Has she been passin’?”) As in Stahl’s other 1930s efforts, his studiously neutral style is built out of profiled two shots in exceptionally long takes.

Ritrovato has always done well by its diva films, under the curatorship of Marianne Lewinsky. (They’ve just released a hot-pink box set of four classics.) In tribute to 1918 there were several star vehicles. I’ve already mentioned L’Avarazia (1918), an installment in a Francesca Bertini series devoted to the seven deadly sins.

Another high point was La Moglie di Claudio (1918), an exemplary tale of excess. When a movie starts by comparing its heroine to a spider, you know she means trouble. Cesarina (Pina Minichelli) two-times her husband, has an illegitimate child, flirts relentlessly with her husband’s protégé, collaborates with spies, and steals the plans to the cannon the husband has designed. She does it all in high style. As she dies, she falls clutching a window curtain.

In a fragment from Tosca (1918), we got a quick lesson in the illogical powers of cinematic composition. Tosca (Bertini again) visits her lover Mario in prison. Their furtive conversation is played out while the shadows of the guards come and go in the background. That’s a source of some suspense for us.

And for the couple as well. Instead of looking left at the offscreen window itself, which they could easily see, they–like us–turn to monitor the silhouettes.

It’s a nice variant on the background door or window so common in 1910s film.

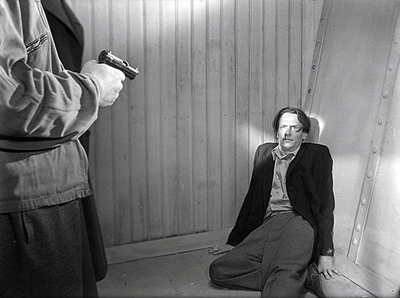

Of all the surprises, the biggest for me was This Can’t Happen Here (aka High Tension, 1950), an Ingmar Bergman thriller. You read that right.

This Cold War intrigue shows spies from Liquidatsia (you read that right too) infiltrating a circle of refugees living in Sweden. The first half hour is soaked in noir aesthetics, with men in trenchcoats glimpsed in bursts of single-source lighting. The preposterous plot gives us a briefcase full of secret papers, attempted murder by hypodermic, torture scenes, and enemy agents acting impossibly suave at gunpoint. A cadre meets in a movie theatre playing a Disney cartoon, with Goofy’s offscreen gurgles punctuating an informer’s confession.

Bergman forbade screenings of the film, but Bologna was given the rare chance to reveal another side of his obsessions with brooding solitude and the pitfalls of love. Peter von Bagh’s illuminating essay included in the catalogue rightly emphasizes how in This Can’t Happen Here murder becomes the natural outcome of an unhappy marriage.

My visit was topped off by the charming Lucky to Be a Woman (1955) in the Mastroianni strand. Sophia Loren, looking like a million and a half bucks, plays a working girl accidentally turned into tabloid cheescake. Mastroianni is a louche photographer who can make her career. Bantering at breakneck speed, they thrust and parry for ninety-five minutes, all the while satirizing modeling, moviemaking, and the itchy palms of philandering middle-aged men. Mastroianni spins minutes of byplay out of an unlit cigarette, while La Loren plants herself like a statue in the foreground, facing us; if Marcello’s lucky, she may address him with a smoldering sidelong glance.

What’s not to like? After thirty-two years, Ritrovato’s magnificence is unflagging.

As usual, thanks must go to the core Ritrovato team: Festival Coordinator Guy Borlée (with appreciation for help with this entry) and the Directors (below). They and their corps of workers make this vastly complex celebration of cinema look easy. It’s actually a kind of miracle.

Ehsan Khoshbakht, Cecilia Cenciarelli, Mariann Lewinsky, and Gian Luca Farinelli.

More Bologna bounty

I think this has become my favorite Ritrovato key image.

DB here:

Cinema Ritrovato rolls on, leaving your obedient servant little time to blog. Herewith some quick impressions on a thin slice of all that’s going on. For a full schedule of this incredible event, go here.

IB or not IB

“Not all IB Tech prints are created equal,” explained Academy Film Archivist (and UW–Madison grad) Mike Pogorzelski. In his last of his annual Technicolor Reference Print shows, he pointed out that Technicolor sent its best-balanced prints to big-city venues and circulated them widely. As a result, they got worn out. The prints most likely to survive were less-than-perfect ones sent to the hinterlands or just kept as backups. Hence the need to preserve the Reference Prints selected by the filmmakers as defining the Technicolor timbre of each film.

With clips ranging from The Godfather and Let It Be to Sssss and Billy Jack, the sample gave a good sense of what Tech looked like a few years before the imbibition (IB) process was abandoned in 1974. Mike and Emily Carman introduced the extracts with informative commentary. I had always thought that Gordon Willis’s cinematography on the Godfather films and The Parallax View increased graininess, and this show seemed to confirm that sense.

Those naughty pre-Code pictures, again

The John Stahl and William Fox retrospectives brought some spicy material. Women of All Nations (1931), Raoul Walsh’s episodic sequel to What Price Glory?, had Quirt and Flagg on the verge of all-out cussing in nearly every scene. A monkey wriggling inside El Brendel’s trousers created moments of good dirty fun. Bachelor’s Affairs (tee-hee, 1932) had Adolph Menjou peering down a golddigger’s front and praising her virtues: “What a charming combination.” She asks if it’s showing. Likewise this repartee: “Were you out last night?” “Not completely.”

William Dieterle’s Germanic Six Hours to Live (1932) begins as a political thriller and devolves into a Twilight Zone fantasy. A representative of a small country passionately protests worldwide tariff legislation. To keep his vote from vetoing the action, spies target him for elimination. Soon enough, he’s throttled to death. But an enterprising scientist takes the opportunity to try out his resuscitation ray, which gives the hero a few more hours to make his mark.

John Seitz photographed the whole farrago in glowing imagery shot through with shafts of blackness, alternately soft-focus and crisply edged. Here’s the magic machine.

The film’s look is an example, I suppose, of what Andrew Sarris once called “Foxphorescence”–the signature of a studio that, from Murnau and Borzage to Ford and 1940s noirs, played host to dazzling pictorial effects.

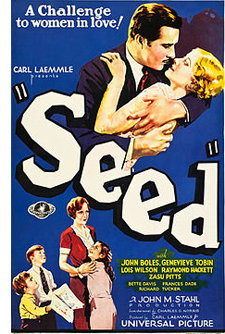

Not completely naughty, but certainly a film about sexual jealousy, was Seed (1931), one of the most anticipated films of the Stahl cycle. It lived up to its reputation as a masterly orchestration of sympathies. At the center is a love triangle based on two women’s roles: the mother and the businesswoman.

Aspiring author Bart Carter has given up his novel, and he lives–he thinks–happily with his wife Peggy and five rambunctious kids. When his old flame Mildred returns to the publishing firm Bart works for, she encourages him to keep writing and to stray from the household Peggy has made for him.

Aspiring author Bart Carter has given up his novel, and he lives–he thinks–happily with his wife Peggy and five rambunctious kids. When his old flame Mildred returns to the publishing firm Bart works for, she encourages him to keep writing and to stray from the household Peggy has made for him.

As often happens in Hollywood, the plot works only if the man is a jerk, and the action will set up things to make the woman take the blame. Mildred may not have schemed to pull Bart away from the start, but the shift in our sympathy to Peggy is pretty decisive. The film’s patient pace and stringently objective presentation lets contrasting feelings get developed gradually. The kids, particularly the whining runt of the litter, are annoying and troublesome. Mildred is no obvious predator, Peggy is trying valiantly to accommodate Bart’s ambition, and he’s enjoying his vacation from fatherhood while still struggling, albeit weakly, to stay loyal to his family.

Stahl was one of the major long-take directors of 1930s Hollywood, and Seed is exemplary in this respect. (The average shot lasts about twenty seconds.) His back-to-basics two shots, facing off characters in profile, become the default setting; there are scarcely any reverse angles or eyeline matches. This apparently simple creative choice, anticipating Preminger’s method of the 1940s and 1950s, puts all characters on an equal footing. The framings force us to concentrate on their conversation, avoiding the customary cuts that punch up particular lines or reactions. A similar steady observation is at work in Stahl’s fine Imitation of Life (1934) and Magnificent Obsession (1936).

1918 and all that

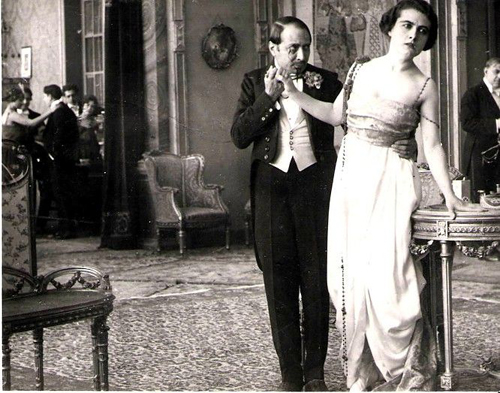

L’avarizia (1918). Production still.

Regular readers of this blog know that one area of my research is the stylistics of 1910s cinema in various countries. (Check the category tableau staging for a sample.) Naturally I dropped obsessively in on the 100-years-ago strands at this year’s Bologna. While there are more films to come, I found plenty to enjoy and think about in the first few days.

There was, for instance, Der Fall Rosentopf, a fragment of a farcical Lubitsch feature. Ernst plays his Sally character, now a detective investigating a flower-pot mystery. Lively enough, the surviving nineteen minutes from early scenes didn’t give me much sense of the whole.

Alongside it were two other comedies. Gräfin Küchenfee featured Henny Porten in a dual role, both countess and kitchenmaid. When the countess goes off to have fun, the maid assumes her identity. Eventually, the two women switch roles when the countess tries to evade police charges by pretending to be the maid. No less predictable in its comic situation was Puppchen, in which a young woman working in a fashion salon breaks a lifelike mannequin and must take its place. It may have been a model for Lubitsch’s Die Puppe (1919).

Stylistically, all these films were fairly staid, with little intricate staging, and they lacked analytical editing apart from axial cuts in and out. Their reliance on longish takes probably reflected the fact that US films, with their bold continuity editing, weren’t available in Germany until somewhat later.

One American film also rejected the emerging Hollywood style, in the name of naivete and fancy. That was Prunella by Maurice Tourneur. It doesn’t survive complete, and it’s been known for many years as a failed venture into artiness. The flat sets resemble children’s book illustrations, and the performance style is wilfully arch. I’ve never found Prunella very interesting, but it does offer further evidence that the 1910s harbored some eccentric and ambitious experiments.

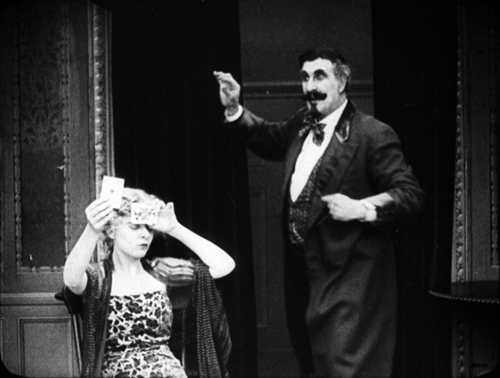

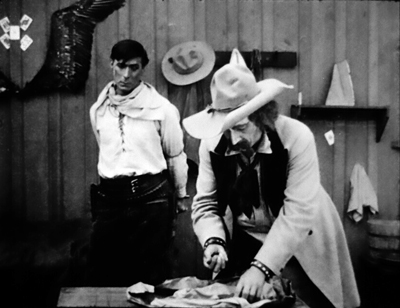

Gustavo Serena’s L’Avarizia impressed me more. It too relies on frontal acting and axial cutting, but as a vehicle for the great diva Francesca Bertini it seemed to me completely engrossing.

As part of a series illustrating the Seven Deadly Sins, it offers a starkly symmetrical plot. Maria and Luigi love each other, but each is dominated by an old miser. Her aunt and his father each amass a fortune in secret while manipulating the young people. Through a series of conspiracies and misunderstandings, the lovers are flung apart. Maria, friendless and illiterate, sinks down, down into the bottom of society.

Each step of the way is given powerful expression by Bertini’s face, gestures, and bearing. She grabs her hair to yank her head back; she blows cigarette smoke in Luigi’s face to show her contempt for his abandonment of her. At one high point, when Luigi falsely accuses her of infidelity, she wrestles with him on a tabletop, giving no quarter. In a tavern fight she pulls a knife before falling to the floor, writhing feverishly in what appears to be her last moments on earth. This is silent opera, with the soaring melody carried by the body.

Up against the fourth wall

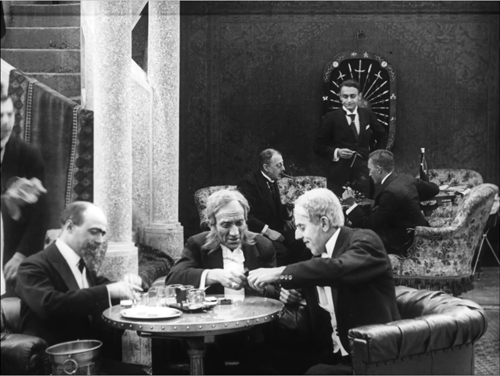

A meeting of the Antifeminist Club (The Oriental Language Teacher).

I wasn’t surprised to find a diva film full of sensuous appeals, but the big revelation of the 1918 cycle so far was the Czech comedy The Oriental Language Teacher (Učitel Orientálních Jazykû). It showed what you could do with a small cast, a few sets, and a cut-and-dried situation.

Sylva secretly falls in love with Algeri, who’s tutoring her in Turkish. After her father is being considered for a diplomatic post in Turkey, he decides to learn the language. He arrives during one of Sylva’s lessons, so she quickly disguises herself as an odalisque. Needless to say, Father is smitten with this exotic beauty. Add in his membership in the Antifeminist Club, led by a comic geezer who enjoys snapping clandestine photos of passing women, and insert deceptions involving a pianola roll, and you have some substantial complications.

Most striking from a pictorial standpoint were the very deep sets–modeled, stylistic historian Radomir Kokes tells me, on the Danish cinema of the period. The co-directors Olga Rautenkransovå and Jan S. Kolár present Sylva’s parlor in an unusual way. Most films of the period put foreground desks and tables at a diagonal bias. But here the father’s desk is thrust very close to us, perpendicular to the camera, and it runs the entire length of the frame.

Moreover, the father is centered at his desk, when the more normal placement would set him to left or right and clear a space in the other half of the frame for other characters. The depth, that is, is typically horizontal. Here, though, it’s also vertical. A character must descend the stair directly above the other, in a maniacally centered composition that’s mildly beguiling in itself.

The set depicting Algeri’s studio is a little more typical of the period, since his desk is placed off to one side, but every shot of this setup makes the foreground area curiously out of focus.

Given that the control of focus is precise in the parlor shots, the slightly fuzzy foreground of the studio set remains anomalous–an error, or a decision to differentiate the two spaces more sharply. In any case, here’s another example of how 1910s movies, from all corners of the world, can set you thinking about the possibilities of pictorial design.

More to come in the next entry, with a special focus on trial films.

Special thanks to Radomir Kokes for help with this entry. More generally, thanks to the Bologna leaders and staff for a tightly-run and ever-exciting event, along with the archivists who made these films available. In particular we owe a lot to Marianne Lewinsky, who curates the Cento Anni Fa series, and to Dave Kehr who, grinning, shares what he called on the first day MoMA’s “mildly obscure” treats. And Imogen Sara Smith gave an exceptionally lucid introduction to Seed.

For more on diva acting, see Ben Brewster and Lea Jacobs, Theatre to Cinema, a book available here, and this entry by Lea on Bertini. Kristin wrote about Prunella and other mildly experimental Hollywood films in Jan-Christopher Horak’s Lovers of Cinema collection.

For more on-the-spot pictures, check our new Instagram page.

John Bailey, President of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, and Michael Pogorzelski.

Something familiar, something peculiar, something for everyone: The 1910s tonight

Idle Wives (1916), produced by Lois Weber and Phillips Smalley.

DB here:

This year I’ve been bouncing between two magnificently creative decades in US film, the 1910s and the 1940s. In autumn I’ve been caught up in things involving Reinventing Hollywood, but those were followed by some big doings on campus.

In spring I was lucky enough to be in residence at the John W. Kluge Center at the Library of Congress. That enabled me to watch nearly a hundred feature films from 1914-1918. I did a talk at the Library reporting on some of that work, and I’ve offered some preliminary observations on those in earlier entries.

Last week, Jim Healy of our UW Cinematheque brought some of the films that had impressed me during my DC stay. There was a Saturday marathon of The Iced Bullet (1917), Alias Jimmy Valentine (1915), The Bargain (1914), Will Power (1913), and The Man from Home (1914). For our Film Studies Colloquium across two Thursdays we screened False Colours (1914; incomplete), The Case of Becky (1915), Idle Wives (1916; incomplete), and Ben Blair (1916). Some of these I’ve written about in earlier entries, here flagged by links.

The Saturday screenings were accompanied by the lively, indefatigable playing of David Drazin. David worked for many hours and without having seen the films in advance. He’s a superb artist.

Seeing the films again, of course I found more to say.

Revival and revision

The Case of Becky (1915).

One of the secondary arguments in Reinventing Hollywood is that many storytelling techniques of silent film subsided during the 1930s but were revived during the 1940s. Silent films were full of dream sequences, subjective points of view, fantasy projections, and flashbacks. Those got elaborated and consolidated for the sound cinema by Forties filmmakers.

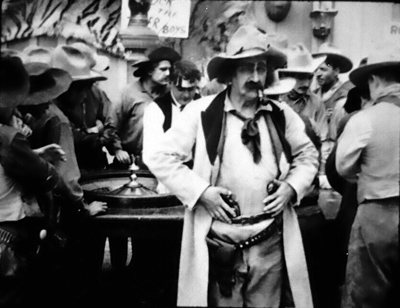

So it wasn’t surprising to find that The Bargain, a fine William S. Hart western, squeezed a lot of mental imagery into a single scene. The Sheriff has arrested Jim Stokes and retrieved the money he stole. Lashed to the bedpost, Jim remembers his wedding and the woman he’s betrayed, presented in a slow dissolve to the past.

Meanwhile, downstairs in the saloon casino, the Sheriff succumbs to an impulse and loses all his money at roulette. Then he remembers, via another dissolved-in flashback, that he scooped up the stolen money too.

Back in the present, he digs that money out of his poke and bets it—and loses.

Later, in the hotel room, Stokes learns of the Sheriff’s folly and has a good laugh. But then he imagines Nell waiting for him, shown in a split-screen image.

At which point the Sheriff imagines his telegram arriving at his town, announcing Jim’s capture and the recovery of the money. That vision reminds him that he can’t return without the money he has squandered.

This makes him strike the central bargain with the thief he’s captured.

In a 1930s film, these visualized memories would most likely be presented verbally, as part of the stream of dialogue. (“When I think of marrying Nell….””I’ve promised to bring the money back…”). But 1910s American films tended to use dialogue titles sparingly; a lot of the films we saw asked the viewer to grasp the situation without benefit of words. The Bargain has only nineteen dialogue titles in 77 minutes (at 16 frames per second).

The Bargain is a good example of how purely pictorial storytelling was used to explicate a situation. Interestingly, today’s films are rather close to this tendency: fragmentary flashbacks and mental visions are common in mainstream movies.

Another echo struck me, this time in The Case of Becky. This is an early story of split personality, a narrative premise popularized after The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1886). Here the young woman Dorothy (Blanche Sweet), under the sway of the sinister hypnotist Balzamo, develops a second identity, the surly and disruptive Becky. Becky isn’t really very dangerous, but when a young doctor, himself a master of hypnosis, falls in love with Dorothy, he determines to cast out Becky. He does so in a passage of intense mind control, visualized through a double exposure of Becky departing Dorothy’s body.

What interested me is that the same visual device was used by Arch Oboler in Bewitched (1945), one of the earliest psychoanalytical films of that era. The heroine’s two sides are summoned up by the shrink.

I suspect that Oboler got wind of the Selznick/Hitchcock Spellbound (1945) and rushed a B-film into production. (He could move fast because he adapted one of his radio plays.) Bewitched was released five months before the Selznick/Hitchcock film. It’s not great movie, but it has a sort of pre-Psycho pitilessness, and it’s always nifty to see a 40s film picking up on a silent-film device.

Cutting things up and filling the corners

My main research questions about the 1910s revolved around stylistics—matters of staging, lighting, shot scale, variety of camera setup, and editing choices. For about twenty years I’ve been exploring how, to put it broadly, the long-take, intricately staged tableau cinema was largely replaced by films dependent on continuity editing. By focusing on the years 1914-1918, I thought I could track the transition in finer grain.

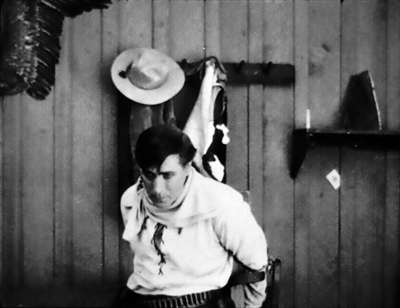

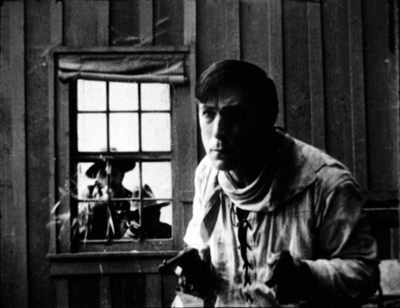

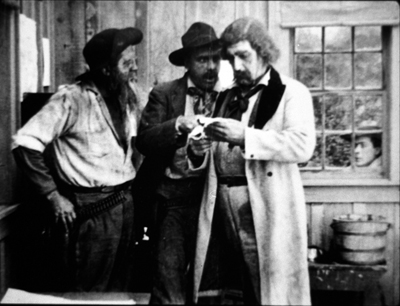

Many films were already building their scenes out of several shots. Go back to The Bargain, from 1914. A series of shots shows Stokes surrounded at the door and window, while also giving us a brief shot from a new angle incorporating tight depth, as the men at the window get the drop on him.

This freedom of camera placement within a single set is typical of the Hart films (see here and here), and of other films by Reginald Barker. It was sometimes visible in Alias Jimmy Valentine from the year before (1913), but it’s more pronounced in The Bargain. Several scenes in the hotel room where Stokes is tied up display a fairly wide array of camera setups.

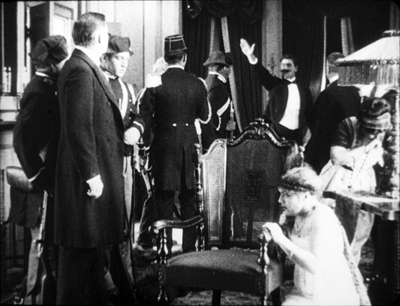

At the other extreme, The Man from Home (1914), credited to Cecil B. De Mille and Oscar Apfel, displays the tableau approach in full bloom. One long take at the climax shows a packed salon. To take just the high points of some pretty dense choreography: Ivanoff bursts in to confront his errant wife, who crumples in the lower right.

Pike holds off the Earl of Hawcastle, now partnered with Ivanoff’s wife. Hawcastle rushes to the right rear to open the curtains (stepping into a spotlight). Summoning the police, he returns to the middle ground to demand the arrest of the fugitive Ivanoff.

But a functionary arrives in the background, lifting his arm to signal the arrival of the bearded Grand Duke Vasili. Vasilii stalks in to take command of the middle ground and confront Hawcastle. Throughout. shrewd shifts of actors’ position open pockets of action, and the performers turn from the camera to drive our eye into depth.

Throughout most of this tableau, broken by occasional titles, Ivanoff’s treacherous wife is crouching in the lower right. This is an example of the “all-over staging” we find in 1910s cinema. Often corners and edges of the frame will be activated and demand to be noticed. For example, in The Bargain Stokes is observing a scene through a window. Cut inside the room, and Stokes can be seen way off to the right in a single pane.

Later directors would have placed the window nearer frame center so that Stokes’ face would be more quickly noticed.

Sometimes we find the filmmaker trusting the audience—or at least a modern audience—too much. In Ben Blair (1916), Ben is lured into a brothel and pulls his pistol in order to escape. But in the master shot, off to the right, the astute viewer can see the louche Sidwell, who’s aiming to marry Flo, cozying up to a hooker before he rises to flee the room. He has already met Ben and fears being recognized.

Director William Desmond Taylor doesn’t supply what I expect Barker would provide: a separate shot of Sidwell seeing Ben and rushing out of the room. Nor does Taylor provide a gradually unfolding tableau that would, by means of figure movement, frontality, centering, and other cues build to a crescendo revealing Sidwell’s presence—the sort of thing we see in The Man from Home. As it is, many viewers may miss the main point of the scene, which is to divulge Sidwell’s sexual betrayal of Flo.

But maybe this was best. Cutting straight in to Sidwell might have suggested that Ben recognizes him immediately. But he doesn’t. As Ben turns, Sidwell is ducking away. Ben has revealed, and seems to be concentrating, on a new center of interest, the woman who’s impudently blowing out cigarette smoke at him. He, like us, is distracted from Sidwell’s departure.

Still, we’re supposed to spot Sidwell even if Ben doesn’t. Only much later, after Sidwell has nearly convinced Ben to give up on courting Flo, does Ben realize that it was Sidwell he saw in the brothel. That’s done through a split-screen flashback of Sidwell starting guiltily beside his floozy.

Again, the shot is a little clumsy in showing Sidwell looking toward the camera, as if Ben saw him directly; but it seems to be another mental image, representing Ben’s now-clear impression that Sidwell was in the brothel.

We don’t have to puzzle over such matters in The Bargain. Barker had mastered the precision necessary for off-center details. When the Sheriff is risking his money at the roulette wheel, a close-up reveals that the croupier is controlling it.

But here’s the neat part. At the turning point, when the Sheriff loses everything, Barker gives us close-ups of the Sheriff and the croupier, but not the hand pressing the button.

We’re sufficiently trained to spot the croupier pressing the button in the long shot (again, off-center). There’s no need to show the gesture again because the priming close-up has told us the game is fixed. Interestingly, that insert shot doesn’t come at the very start of the Sheriff’s gambling jag, so initially we might think the wheel is honest. We get the revelation just when the Sheriff is about to bet the money he can’t afford to lose. That boosts the dramatic tension.

Movies within movies

The Iced Bullet (1917).

While stylistics was my prime research focus, I couldn’t help but notice some bold narrative initiatives. A good example of a playful one was The Iced Bullet (1917), which has a Russian-doll structure (like many 40s films).

The inner tale recounts how a scientific detective solves an attempted murder, one using the method tipped in the title. But that’s swallowed up in a prologue and epilogue showing a foppish author crashing the Ince studio. He manages to interfere with filming, evade the guards, and take refuge in an executive’s office. He has brought along his screenplay, The Iced Bullet, which he hopes to direct and star in.

At the desk he falls asleep and dreams the detective story we see. At the film’s end he wakes up and flees the studio, pursued by watchmen. One trade paper of the time suggests that the comic frame story was devised in order to expand and elevate the murder story–which may explain why the film has been credited to both Reginald Barker and Charles Swickard. Maybe one directed the frame story and one the embedded one.

As the frame story stands, it offers us not only a comic pretext but precious views of the vast Ince studio.

There are also some nerdish in-jokes. C. Gardner Sullivan, author of the whole film we see, appears as the executive whose office is commandeered, while Barker shows up as a raging director trying to get the aspiring screenwriter off the set.

And when that invader takes over Sullivan’s office, he scoffs at a huge bust of William S. Hart, by now a major star.

The year before, Lois Weber and her husband Phillips Smalley had given us a more intricate film-within-a-film structure. The central story of Idle Wives centers on the plights of three women. Anne Wall is a wealthy but disillusioned wife who leaves her husband John to take up settlement work. She lives with Alberta, who has married John’s brother Richard. The couple has been disowned by John’s mother and sister. In her charity duties Anne meets Molly Shane, who has left her family to run off with the no-good Larry. Anne helps Molly through her pregnancy and reconciles her with her family. John, seeing how Anne has changed the lives of unfortunate women, welcomes her back and faces down the disapproval of his mother and sister.

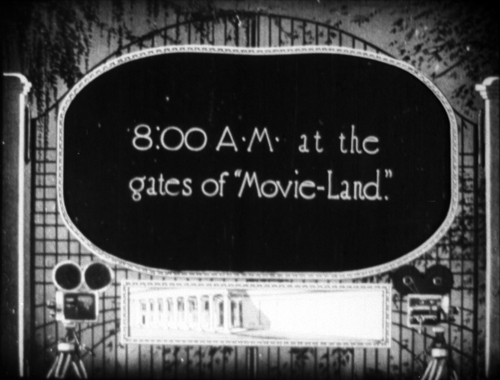

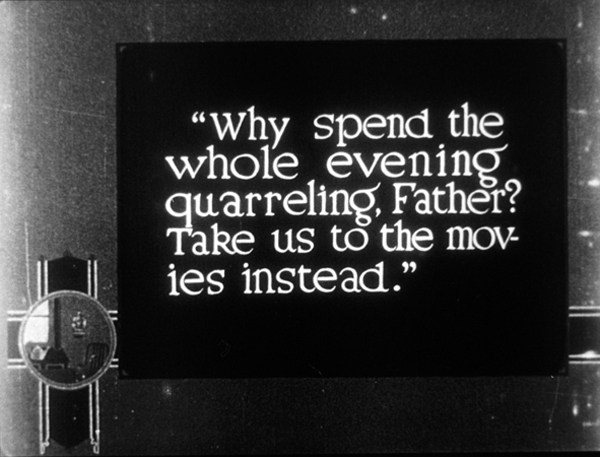

This story is enclosed within another one, involving three other women. The Jamiesons, though wealthy, have an empty marriage. When Jamison meets an old girlfriend, they decide to go see a movie. They’re trailed by Mrs. Jamieson. At the same time, Mary Wells disobeys her mother and goes out with the thug Tough Burns. They wind up going to the same movie theatre. And the poor, hard-working Smith family, whose daughter is longing to escape, decides to take a day off and go to the theatre as well. All of them join the audience for Life’s Mirror, a film by none other than….Lois Weber. It stars Weber and Philips Smalley, who’s given his own poster.

This frame story, not in the source novel, is pretty stunning. In the first reel the people assemble at the theatre, which, as you see up top, flaunts the Weber-Smalley brand. These scenes are fascinating representations of moviegoing culture of the time, showing the ticket booth and the auditorium.

Just as important is the way that seeing the movie affects the characters in the frame story. Shots show people in the audience reacting to the fictional world.

The point of the film is that the characters, recognizing their counterparts on the screen, improve their behavior. Cinema is granted the power to divine the problems of its audience, and to heal their lives.

Or so we’re told from contemporaneous synopses. Because, in one of the great losses of American silent cinema, we have only the first and second reels of Idle Wives. Fortunately, those constitute the prologue and the initial exposition of the inner story.

How does the frame story turn out? According to the fullest contemporary account I’ve seen, in the epilogue Jamieson sees his wife weeping in the aisle, sends her rival away, and reconciles with her. Mary is shocked into realizing the risk of dating Tough Burns, who seems ready to reform after seeing his fictional double behave so cruelly. The Smiths agree to be kinder to one another, and the daughter of the family realizes the danger of fleeing home.

Two network narratives, then, in a single movie. Idle Wives has over twenty individuated characters, linked by kinship or domestic circumstances. (For instance, in both stories some characters live in the same building.) It becomes didactic, as Weber’s films often are, with the theatre presenting a placard that underscores the lessons, and opening titles that address the audience directly. Idle Wives was fairly described by a review as “a preachment on the sacredness of the home, also on the power of the motion picture.”

For most film historians, the great experimental film of 1916 was Intolerance, another tale of parallel situations and fates. But the same month that Griffith’s ungainly masterpiece was released saw the appearance of Idle Wives—in its way, no less daring, and by today’s standards startlingly modern. How many other remarkable films have been lost or have gone unnoticed? Like archaeologists excavating a site, we have a lot more digging to do to understand the glories and unpredictable experimentation of the cinema of the 1910s.

Thanks to my hosts at the Kluge Center last spring: Ted Widmer, Emily Coccia, Travis Hensley, Callie Mosley, Mary Lou Reker, and Dan Turello, as well as the team in the Moving Image Research Center–Karen Fishman, Dorinda Hartmann, Josie Walters-Johnston, Zoran Sinobad, Rosemary Hanes, and Alan Gevinson–along with the Culpeper dynamic duo Mike Mashon and Greg Lukow. We in Madison are especially grateful to Lynanne Schweighofer and George Willemen for preparing a reconstructed version of Ben Blair. Thanks also to Jim Healy, Mike King, and Roch Gersbach for arranging the Madison screenings.

Some of David Drazin’s piano accompaniments are available on DVDs from Texas Guinan (that’s right, tguinan at aol.com).

Idle Wives has been posted online by the New Zealand Film Archive and the Library of Congress. An informative puff piece from the era is “The Smalleys Turn Out Masterpieces With Actors or With Types,” The Moving Picture Weekly 3, 14 (18 November 1916), 18-19, 26. The most comprehensive guide to Lois Weber’s career is Shelley Stamp’s Lois Weber in Early Hollywood (University of California Press, 2015). I discuss the Smalleys’ little masterpiece Suspense (1913) here. Reinventing Hollywood has a chapter on the psychoanalytic cycle of the 40s, including Bewitched.

On all-over staging, and bungling the tableau, see the entry “Looking different today?” We have some entries on decentered framing, one on Mad Max: Fury Road and another on Fritz Lang’s use of corner frame space.

Idle Wives (1916).