Archive for the 'Tableau staging' Category

Wayward ways and roads not taken

DB here:

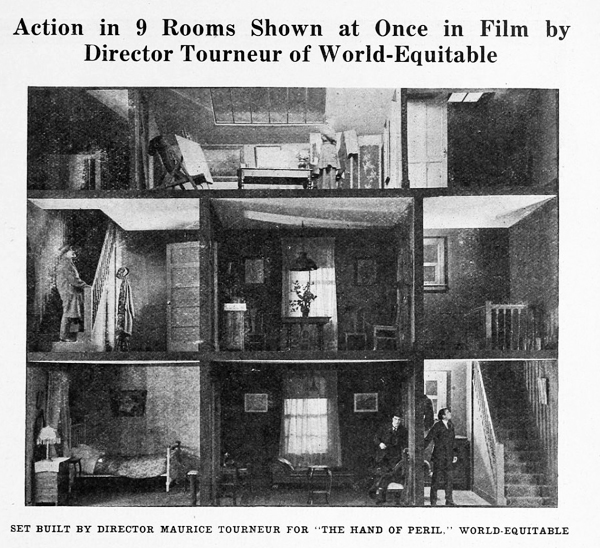

The Hand of Peril (1916) was trumpeted as something new in movie storytelling. It avoided the “cut-back”—that is, crosscutting between different lines of action. In this film, according to the Motion Picture News story above, “nine rooms of a house are shown, with action occurring in each room simultaneously. . . . The action occurring in one room . . . would have to be ‘flashed back’ were the nine rooms not shown.”

Variety found the innovation valuable for pacing. The movie “unfolds in the first four reels with the speed of a race horse. The suspense is constant and there isn’t any let-up whatever until the last few hundred feet.” It’s not clear whether the whole action took place in the house, but for the scenes that did, it appears that the cutaway set served a reference point, a sort of macro-establishing shot. This view gave way to cut-in closer views of the scenes in specific rooms.

Another trade journal noted: “The experiment is quite novel and attractive and fits in admirably in the story, but if it will prove of general worth cannot be told yet.” Now we can tell. This was a road not taken. Crosscutting remained in force, being far more cheap and flexible than dollhouse sets.

No copies of The Hand of Peril are known to have survived. Yet the fact that it was made suggests just how energetic the 1910s were in raising striking creative possibilities—some of which became conventional, some of which fell by the wayside. Seeing this sifting and winnowing at work was a constant delight during my recent stay in the Kluge Center at the Library of Congress. Watching nearly a hundred American features from 1914-1918 drove home to me how excitingly strange movies can sometimes be.

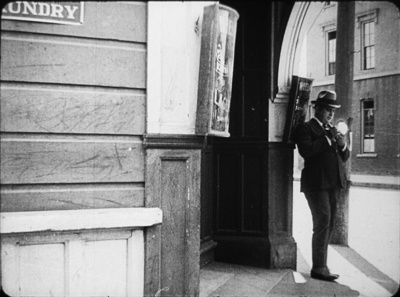

On the one hand, the conformist side of the films was there in abundance. Most of what I encountered were variants of an emerging “classical Hollywood cinema,” as they (we) say. Some efforts were crude, some smooth, but you could tell what the filmmakers were going for, and it was a thrill to see obscure films effortlessly exploiting schemas that would become central to our films. What a kick to see, in The Sign of the Spade (1916), a detective using a hand mirror to trail a suspect, with beautiful control of POV, frame composition, and rack-focus.

Hitchcock, eat your heart out. Well, wait until you start making films.

Yet looking for norms sensitized me to non-normative things—not merely clumsy efforts, but genuine attempts to try something different. Different and, to our eyes, often odd. American features of the 1910s include cuts and framings and camera moves and lighting choices and performance bits that no one now could imagine using.

My viewing companion James Cutting compared the week’s worth of films he saw to the Cambrian explosion in evolution, a period where all manner of organisms burst forth in profusion—before selection pressures wiped many out. While filmmakers were mastering classical plotting and continuity style, lots of other stuff was going on.

Have a look. Actually, several looks.

Widescreen, no. Tallscreen, yes.

Ready Money (1914).

In this shot, the story action is taking place at the nightclub table, but the society types gathered there are overwhelmed by all the hubbub around and above them. And we aren’t given closer views to help us sort it all out.

In all periods of film history, directors usually tried to center the action. Yet in early years, they sometimes favored framings that would today be considered strangely decentered. One of my favorite tactics from the ‘teens involves putting important elements in the bottom of the frame, notably in extreme long shots. In The Spoilers (1914), Cherry flops back in her saddle when she sees the devastated mining camp.

At the big reception in The Sowers (1916), a modern director would have put Paul and the dignitaries he greets in the foreground, and let Princess Tanya descend in the distance. But William C. de Mille creates a vast vertical composition, setting Paul in his braided uniform in the lower third of the frame and putting Tanya far back on the staircase.

Such top-heavy shots look odd to us, but they have a sort of grandeur, and the taste for them can be acquired. You can see a more intimate example in the fine recent release of Thanhouser films restored by the Library of Congress. The opening sequence of The Picture of Dorian Gray (1915) shows Dorian at the theatre, in a box in the foreground with Romeo and Juliet playing onstage behind him.

Even in the teens, I think this is an outlier. Most theatre scenes are handled with cutting to reverse angles of the audience and the onstage players. When there’s a box in the foreground, it’s usually anchored as such, as in Feuillade’s Fantômas (1913) or Willliam Wauer’s Der Tunnel (1915).

The strange symmetry of the Dorian Gray composition, aided by putting Dorian’s head along the vertical axis rather than off to the side, and by putting the object of his attention, the actress, directly above him, is really startling. The all-over quality of these compositions usefully remind us that every inch of frame space is there to be used if you have the imagination. We’ll see this hypersaturation of the frame in some later examples, but eventually the tactic would go away. Shots would put the human figures in the center of the format, or in long shots place them gracefully on foreground right or left.

Scene + insert

Both European and American directors of the 1910s employed what I’ve called the tableau approach. Within a fixed camera setup and fairly distant framing, the viewer’s attention is controlled through staging, either lateral or in depth. I’ve given plenty of examples elsewhere of how flexible and precise this style can be. A beautiful example occurs in Lois Weber’s False Colours, which I’ve already analyzed along these lines.

During the years I examined, directors were already discarding this approach in favor of cutting-based ways of guiding our eye. Some freely put the camera at various points around a set or an outdoor scene. (In all national cinemas of the period, we find more variety of camera placement on location than in sets, for obvious reasons.) More common was the tendency toward what was called the “scene-insert” method. A master shot of middle range (the “scene”) would be followed by a closer view of something within that space (the “insert”). Very often that cut would be an axial one—that is, a setup straight along the camera axis. Although sometimes decried as a mistake, the axial cut has been used by filmmakers of all eras.

The corn-husking bee in The Hoosier Schoolmaster (1914) illustrates how a basic tactic of the tableau style may be integrated with the scene-insert method. The new schoolteacher is boarding with Mrs. Means, who’s trying to get him to marry her daughter. As the community gathers (that corn won’t husk itself), Mrs. Means forces her daughter on him. The teacher, though, is more attracted to the demure town outcast Hannah. First, Mrs. Means stands behind the schoolmaster and her daughter. Back to us, she addresses the hayseeds.

She moves away to show Hannah in the background. In the tableau approach, this blocking-and-revealing action is usually repeated throughout the shot, but here it’s a one-off device. As soon as it happens, the schoolmaster turns to look back.

Now comes an axial cut to Hannah in the background.

Simple and efficient, this is a good example of the scene-insert method, here enabled by a bit of depth staging. Later stretches of the scene will use the blocking-and-revealing tactic in conjunction with further axial editing.

Sometimes the “insert” phase takes a turn that doesn’t look so simple. Consider this shot from The Spoilers (1914). In another wildly decentered framing, the hero Roy Glenister has jumped down from a balcony (upper right) to land on the floor of a big dance hall as seedy as anything in Deadwood. He lands and faces the crowd in the far distance, while the foreground area of gamblers clears away in a panic, so we can see him a bit better.

This is a very distant framing, so we get an axial cut in to him crouching before the surly crowd.

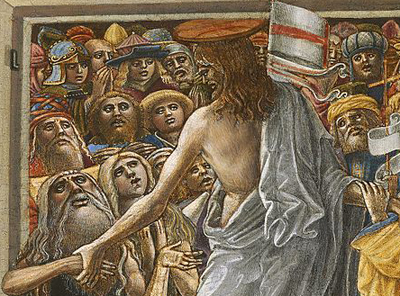

This is a striking insert because in order to give a sense of the massed crowd Roy faces, the director has apparently stacked people up—by height, and perhaps on risers of some sort—so that a welter of faces appear piled up against him. The showgirls at the very top of the frame are on the stage, but the people in the middle were on the same floor as Roy in the master shot. The technique is reminiscent of the stacking of crowds we find in classic Western painting. Here’s a detail from one of the weirdest pictures I saw in the National Gallery, Christ in Limbo by Benvenuto di Giovanni (ca. 1436).

Later filmmakers would presumably have used a high angle to let us see the faces; but then we’d lose the looming effect of Roy’s back in the foreground. Artistic choices are always trade-offs, and here, for the sake of a strong expressive effect, director Colin Campbell has sacrificed spatial realism in a way that probably wouldn’t occur to a contemporary filmmaker.

The shift from long shot to a closer view here is pretty extreme. At several points in my viewing I noticed that when using the scene-insert method, filmmakers often didn’t try for a smooth gradation of shot scales. The old triumvirate long shot/ medium shot/ close-up aims to lead the viewer gradually to the heart of the action, but in the 1910s directors seemed almost impatient to get to the meat of things.

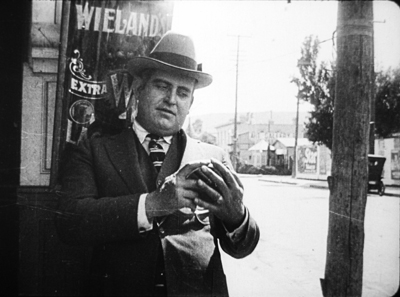

So, for instance, in William Desmond Taylor’s Pasquale (1916), the good-hearted hero is trying to keep up appearances at the wedding of the woman he loves. We get a cut from a very long shot to a tight close-up, accentuated by the vignetting that isolates Pasquale’s face. No medium-shot eases the transition.

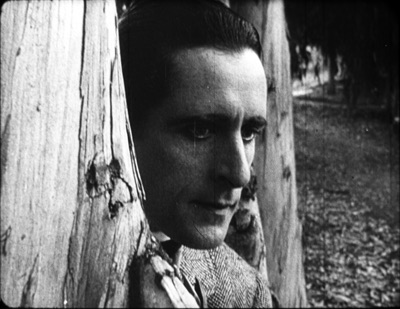

For modern audiences, I think this is a bit of a bump–but nothing compared to the scene-insert leap we get in Vanity Fair (1915). In what is everybody’s idea of what those old movies look like, Becky is exploring the parlor. It’s a very distant shot, atypical for an interior of this scale. And the abrupt jump to a very close insert shows not Becky but the photograph she studies.

This is quite odd. Even stranger, the camera stays back from Becky throughout the film.

It’s unusual for an American movie of 1915 to avoid inserts, especially since Becky is played by the famous Minnie Maddern Fiske, who had popularized the part on stage. Where are the star close-ups, as in Pasquale? Are we dealing with simple incompetence? Apparently not, Variety suggests.

This seems plausible. By shooting most scenes in anachronistic long shots, the director could play down the fifty-something performer portraying a young girl. In the process he could associate the classic story with pre-teens photodramas, which seldom used close-ups. This deliberate anachronism suggests that filmmakers were already aware of the choices of shot scale they now had, and what the scene-insert method committed them to.

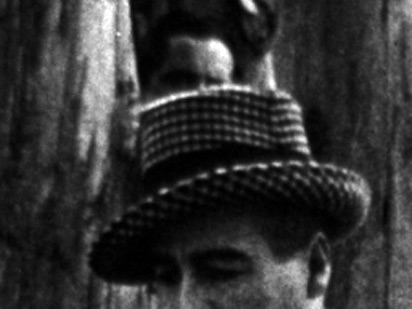

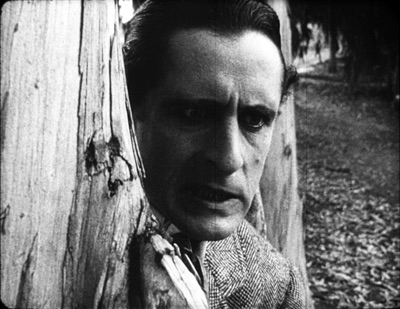

What survives of Weber’s marvelous False Colours offers a great many lessons in the range of 1910s techniques, but one sequence flaunts the all-over long shot and the jolting insert. The conman Bert has persuaded his wife Flo to pose as the missing daughter of the wealthy actor Lloyd Phillips. In this scene, Flo and Phillips have retreated to a park bench to get better acquainted. Bert hides behind a tree to watch them.

This is a pretty standard situation, but it’s handled in an eccentric way. As the couple sit in awkward silence on the bench, in the far left background Bert creeps in. Problem is, you can barely see him: only his hand, on the far, far left center, is visible in silhouette as it approaches the tree, followed by a dark blot. Thanks to Photoshop, I give you the insert that Weber denies us.

Who would see this? Maybe a viewer from the time, trained in different viewing skills–someone used to the frame’s being packed full? I consider this possibility in an older entry. And there’s certainly a slice of light space left vacant to allow for the hand, creating an extreme case of aperture framing. Anyhow, Weber then does what Taylor did with Pasquale. She cuts from the fairly distant shot to a big close-up of Bert peering out from the tree.

Compared to the bare hint of his arrival with the fugitive hand, this strenuous shot is overcompensation. All we needed was a sort of medium shot of him listening, preferably with the couple in the foreground to orient us. That shot comes, but again in an eccentric way. At first, Phillips blocks our view of Bert, so the actor in the rear has to raise his head–creating the impression of floating just above Phillips’ hat. Again, I supply a blow-up.

And when Flo, lying, says in a dialogue title that her mother talks of Phillips constantly, Bert’s head jerks up angrily. He’s still stuck atop Phillips’ hat. Another huge close-up reinforces his reaction.

Maybe it’s all a mistake? Did Weber screw up a simple scene? Why not just settle Flo and Phillips a little more to the right on the bench, leaving plenty of space on the distant left for Bert to creep behind the tree and peer out, perfectly visible to us throughout? Then, if you insist, you could have the big close-ups of Bert’s reaction? Or did the DP not allow for Phillips’ blocking Bert? (Remember, they didn’t have reflex viewing back then; the viewfinder didn’t show exactly what the lens took in.)

I can’t say. Maybe this is bold, maybe just a botch. But scenes like this in False Colours demonstrate the far-reaching possibilities that people were trying out in the Cambrian explosion of film style.

Jam sessions

Liberty Belles (1914).

In Ready Money, The Spoilers, and other instances we’ve already seen a penchant for stuffing the frame with figures, props, and items of setting. People at the time apparently noticed it too. Charlie Keil, in his indispensable survey of film style from 1907-1913, writes:

Critics advised against “crowded groupings” for numerous reasons: first, if a massing of characters seemed unnaturally pressed together, it would expose the limits of the shooting conditions and destroy the illusionism that cinema was meant to sustain; second, such unnatural staging would violate the standard of composition derived primary from photography, which stressed balance and order; and third, overly compressed staging might obscure the central narrative action and create problems of comprehension for the viewer.

Widescreen, as I’ve mentioned before, poses problems. How do you fit in the human body? How do you fill up the lateral expanse, or do you leave it empty? The squarer rectangle of the 1.33 (or even narrower) frame of early cinema allowed bodies to be packed in, and we’ve seen a surprising vertical dimension to the compositions. Filmmakers found ingenious ways to jam in their figures, especially when they began moving them closer to the camera. By 1914, with the “American foreground,” the front line of action might get pretty crowded.

The climax of Kindling (1915) shows that Cecil B. DeMille was no slouch at filling up the midshot space and then developing the scene through small gestures and changes of posture. It’s far too long for me to run through here, but I think you get the idea.

The blocking and revealing, the slight changes that hide or unmask someone behind someone else, the tendency for actors to freeze so that one performer’s movement draws our eye: all these tactics of long-shot tableau staging are played out in small compass. Call it a jam session.

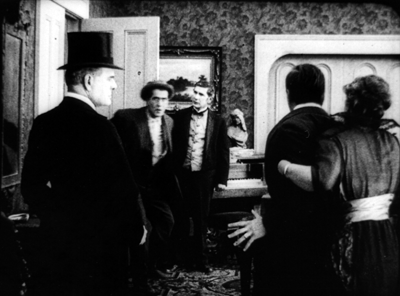

Cecil’s brother William followed suit in a film of the following year, The Heir to the Hoorah (1916). This comedy of class differences centers on three newly rich gold miners, all bachelors. The roughnecks Bud and Bill urge Joe to marry Geraldine so that there will be an heir to their fortunes. Geraldine’s mother, Mrs. Kent, invites the men to a dinner with her swanky friends. For once, the rich folks aren’t snobs but are good-natured folks–and they have to be, for the clumsy ways of Bud and Bill would outrage anyone less tolerant.

William C. de Mille often avoided long shots and instead covered scenes in fairly tight medium shots and plans américains. Just before the guests go into dinner, they’re huddled together in just such a composition. On the left, Bud is chatting with Joe and a fancy lady. On the right, Geraldine and her mother watch. Behind them are the lady’s husband and Bill. At first the action is on the right, as Mrs. Kent frets about the deplorables Geraldine has brought into the house.

Faces now get diced and sliced, masked and shifted. The gag is set up by servants emerging out of distant darkness. A small aperture opens up so we can see Bud and the others on the left picking up their drinks from a tray.

The insert is a surprisingly tight long-lens shot of the group on the left, though with others hovering around the right frame edge. Drinks are taken, a toast proposed.

And Bud proceeds to spill his drink on the lady, who responds without rancor.

Another insert shows a reaction shot of Bill and the lady’s husband, also unflapped, before cutting back to the full “scene.” By now, with waiters coming out from behind foreground figures, there are nine characters crammed into the shot.

There’s more to come when Bud’s spur gets caught in the lady’s gown, but you get the idea. Axial cuts carve into this mob and shove bits and pieces of faces, bodies, and gestures out at us. The principles of tableau staging are squeezed down into medium shots. William C. de Mille was a pioneer of multiple-camera shooting for ordinary scenes, and he may well have used a separate camera for the long-lens shots (even though the position of Geraldine on the right is wildly cheated between shots 2 and 3 and 3 and 4).

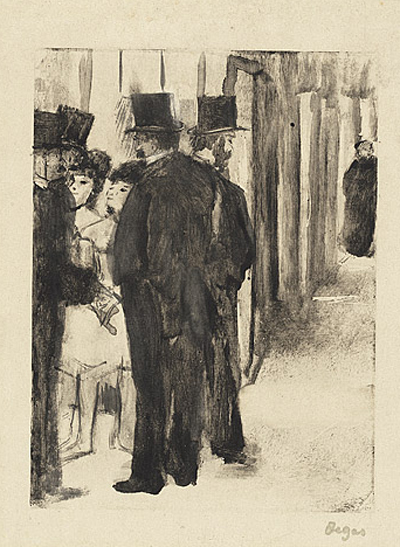

Later Hollywood filmmakers would favor much cleaner images of groups, with heads evenly spaced out across the frame. But visual artists had long explored the bunched-faces option. Here, for instance, is Degas’ daringly unbalanced and crowded Pauline et Virginie of 1876.

Yet these somewhat wild experiments weren’t dead ends. They remained artistic possibilities to be explored more, when other filmmakers hit upon them. Altman’s and Jancsó’s crowded telephoto shots revive the packed frames we see in the 1910s, and other filmmakers found artistic rewards in fanning out figures as in the lovely frame above from Liberty Belles. Those cute girls come back to life in Hou’s Cute Girl (1981) and Millennium Mambo (2001).

Even The Hand of Peril‘s dollhouse set didn’t go absolutely extinct, as admirers of Jerry Lewis (The Lady’s Man), Godard (Tout va bien), and Wes Anderson (The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou) know. Film style, it seems, knows few dead ends, only detours.

There’s a tendency to think that the history of style constitutes an ever-expanding menu of options. Today, you can cut the way Griffith or Eisenstein or Godard did, right? A similar case has been made for technological change. For decades it was much harder to make a color film than a black-and-white one, but now filmmakers can pursue either option. Most filmmakers in the silent era couldn’t make a talkie, but today’s filmmakers can go silent if they want.

Yet it’s proven surprisingly hard to make a contemporary film look and sound like one from an earlier era. On the sheerly technological front, it’s not easy to recapture the tonal range of orthochromatic nitrate, or the sound texture of early talkies, or the saturation of Technicolor. As for style—how you stage, how you cut, how you frame, and so on—again certain things are hard to recapture. It seems that certain stylistic possibilities, like purely technological ones, have been taken off the menu.

Why is style so hard to recapture? Some elusive nuances of lighting and color depend on technological factors we can’t recreate. IB Tech can’t easily be mimicked with a dropdown menu. On other dimensions, the range of creative options in earlier eras just doesn’t come easily to today’s filmmakers. But maybe by looking at those films we can reconstruct that range. We might also encourage filmmakers to take the sort of chances people did at the very beginning of what we have come to call Hollywood.

This is, I think, my last post for a while on my 1910s adventures at the Library of Congress. I must move on to other projects. As ever, I’m tremendously grateful to the John W. Kluge Center, and particularly its director Ted Widmer, for enabling me to conduct this research under its auspices. A special thanks to Mike Mashon of the Motion Picture Division, and all the colleagues who have been helping me in the Motion Picture and Television Reading Room: Karen Fishman, Alan Gevinson, Rosemary Hanes, Dorinda Hartmann, Zoran Sinobad, and Josie Walters-Johnston. Thanks as well to James Cutting for enjoyable discussion as we watched old movies together.

The new collection of Thanhouser films that includes The Picture of Dorian Gray also provides an enjoyable tour of the LoC Culpeper facility I blogged about in the spring.

I’m grateful to Charlie Keil for ideas and help with sources. The passage I’ve cited from him is in Early American Cinema in Transition: Story, Style, and Filmmaking, 1907-1913 (University of Wisconsin Press, 2001), 134-135.

The quotations from Variety come from anonymous reviews of The Hand of Peril (24 March 1916), 24, and Vanity Fair (29 October 1915), 22.

Other entries about my DC viewing are Anybody but Griffith, Movies in the mountain, and on the machine, Film noir, a hundred years ago, and When we dead awaken: William Desmond Taylor made movies too. More generally, see the category of entries on Tableau staging and my books On the History of Film Style and Figures Traced in Light: On Cinematic Staging. The relation of the tableau style to Hou’s work is considered in the latter, as well as here.

On the difficulty of replicating older film styles, see our blog entries on The Good German and forging a film.

Building the set for The Life Aquatic (Wes Anderson, 2004).

Movies in the mountain, and on the machine

DB here:

I’m back in Madison from 2 1/2 months in Washington, DC. under the auspices of the John M. Kluge Center, where I was this year’s Chair of Modern Culture. This kind appointment allowed me to pursue my research into 1910s American film style, than which nothing could be more fun. Along with that were some extramural activities. The most spectacular one was our Kluge field trip into the most overwhelming media archive in the world–the bulging-biceps caped crusader of film, TV, and sound preservation.

Treasures under Mount Pony

Dr. Strangelove could have come up with the idea. If the Russians attack the US, better have a deep underground vault for storing a few billion dollars to replenish currency supplies on the East Coast. So in the Culpeper, Virginia countryside build a gigantic secret bunker. Include facilities for housing 500 or so personnel to keep the government, or what was left of it, running for a month. Add amenities like a pistol range and refrigeration units to cool cadavers that couldn’t be buried outside. Getting assigned here in nuclear winter would definitely count as subterranean homesick blues.

This super-secret complex was completed in 1969. It boasted foot-thick concrete walls and was surrounded by barbed wire and machine-gun nests. By 1992, the bombs had failed to fall, so the complex was decommissioned and eventually offered for sale. After a major grant to the Library from the David and Lucille Packard Foundation, a long-time friend of American film history, the building was transferred to the Packard Humanities Institute . The facility was renovated thanks to over $260 million of Packard and Congressional funding. A lot, yes, but in 2017 dollars that comes to about $402 million, and Beauty and the Beast has scared up about twice that over the last couple weeks.

The renovation turned this vast bank vault/bomb shelter into the world’s most colossal and up-to-date media storage and preservation facility. Opened in 2007, the National Audio-Visual Center is also known as the Packard Campus. Its collection of films, videos, and audio records, along with posters and documents, come to over six million items sitting on ninety miles of shelving. With 80 per cent of it sunk below ground, it was designed to be an exemplary green building, with a vast gardened roof.

Thanks to the energy of Kluge Center director Ted Widmer and his colleagues, we had a chance to visit the place. Greg Lukow, Chief, NAVCC–Packard Campus, and Mike Mashon, head of the Moving Image section, led us in a labyrinthine, carefully organized three-hour tour of the dazzling facility.

I can’t convey all that we learned about conservation of film, TV, sound recordings, and digital media. Rest assured that the hundred-plus people working away here in state-of-the-art conditions are striving mightily to save media artifacts for you and me and our heirs. Here are some high points.

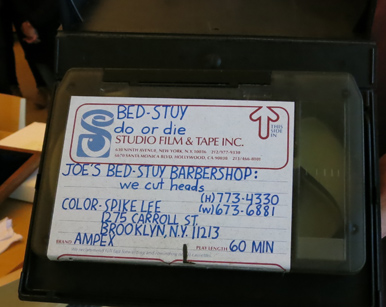

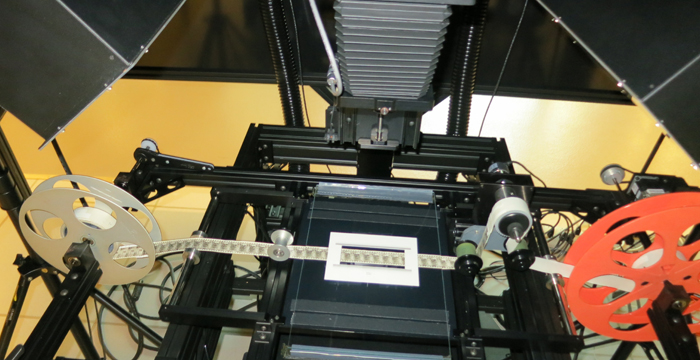

Mike introduced the visitors to the moving-image formats of the media conserved at the facility, everything from film and videotape to Digital Cinema Packages. Spike Lee’s first film, as a copyright deposit, is there too, on Ampex tape.

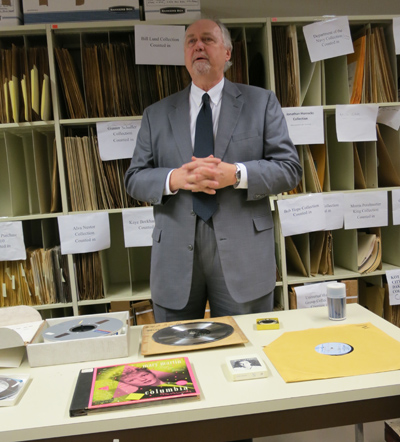

Sound isn’t neglected, as Greg offered a comparable overview of all the audio formats, including cylinder and wire recording. Yes, 8-tracks are also involved. On the right you see the Scully Lathe, a gleaming bad boy that cut disks. Used from the 1930s into the 70s it’s being brought back with the new interest in vinyl records.

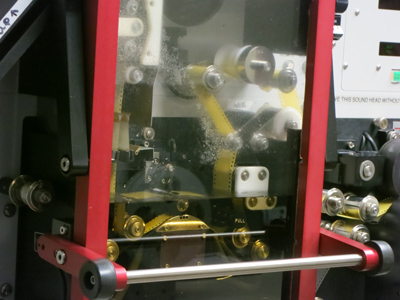

We visited several lab and restoration rooms, including one for wet-gate printing and another for migrating VHS tapes to digital files. Since the latter has to be done in real time, robots are recruited for the job, busily gliding up and down ranks of cassettes.

Of course we had to stop by film vaults, kept a chilly 39 degrees. On the left we see some of the holiest of holies, nitrate vaults. It looks like a Spanish Civil War prison, rows and rows of heavy doors. The vault on the right contains master safety film elements, on both acetate and polyester stock.

What’s a trip to an archive without despoiled artifacts? On the left, a flaking glass-based 16-inch lacquer instantaneous disc from the NBC radio collection. “Instantaneous” means that it was a recording of a live broadcast, and so was probably unique. On the right, we have decomposed nitrate film.

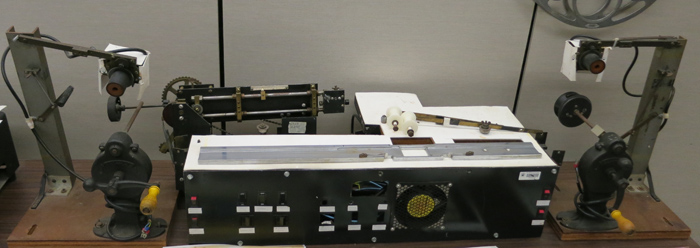

Of enduring interest to cinephiles is the famous paper print collection. Film companies of the earliest years submitted to the Library movies on rolls of paper, to be copyrighted in the manner of still photographs.To be preserved and screened, those had to be turned back into films. During the 1950s that task was fulfilled by Kemp R. Niver in a home-made rig.

He transferred some 3,000 titles to 16mm–not the ideal format, but better than nothing. Some results were fuzzy and jumpy, but many came out okay. I watched several during my stay, including The Hoosier Schoolmaster (1914).

Since then, some excellent 35mm prints have been made from the paper prints, and still more success has been found with digital remastering, which can correct for misaligned frames on the original paper copies.

It was good to learn that film copies of new releases are still being submitted for copyright deposit. An impeccable print of Get Out arrived while I was there, and of course 35mm advocate Christopher Nolan wouldn’t miss a chance to save Inception and other of his works.

But I was dismayed to learn that a great many companies, taking advantage of a loose requirement about what counts as a deposit copy, are submitting DVDs, Blu-rays, and even DVD-R versions of their films. If they can’t submit a print, they should at least provide an unencrypted DCP. Otherwise, scholars and audiences of the future will encounter the digital equivalent of the crawling, scraped deterioration we see with film.

101 movies

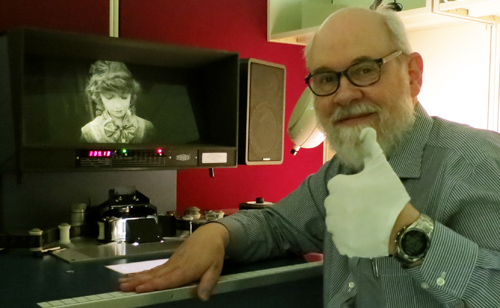

Fortunately for me, 1910s films are still available on film. Viewing prints of films stored at Culpeper are shipped to the James Madison Building in the District. There, in the Moving Image Research Center, they may be viewed on my old friend, the flatbed machine known as a Steenbeck. Every day a Steenbeck patiently awaited my depredations.

The staff of the Reading Room were just superb in helping me order titles and dig up information about them. Above you see the team I worked with: Dorinda Hartmann, Rosemary Hanes, Josie Walters-Johnston, and Zoran Sinobad.

I learned an enormous amount from them, and I enjoyed talking movies with them during our breaks. Others who helped me greatly were Karen Fishman, Research Center Supervisor, MBRS Division; Alan Gevinson, curator of the American Archive of Public Broadcasting; and David Pierce, Assistant Chief, NAVCC–Packard Campus.

My mission was to see as many American fiction features from the 1910s as I could. This was the period when a five-reel film (ca. 60-70 min.) became a dominant format, though shorts and longer films were also being made. I’ve spent about a decade watching largely European films of the period in various archives and in Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato, with results I’ve occasionally discussed on this blog. A visit to the LoC nicely complemented my Continental and Nordic explorations. Although several American films from the period are available on DVD, I’ve tried to see even those in film copies. (Why? Tell you later.)

For a time I was joined by James Cutting, perceptual psychologist extraordinaire, who enthusiastically wanted to watch these old movies. His presence helped me a lot, sharpening my attention to things in the images. Here’s James, skewed, during our nighttime trip to Chinatown for food and Get Out.

In all, across 42 business days (had to take days off for holidays and inauguration), I saw 101 films, 98 from my period and three others for other projects.

Not all the films survive complete. Some lacked one or more reels. That’s a great pity in the case of Lois Weber/ Phillips Smalley’s False Colours (1914), Sunshine Molly (1915), and Idle Wives (1916); William deMille’s The Sowers (1916); William Desmond Taylor’s Ben Blair (1916); and many other stunning projects I got a glimpse of. But a little is better than nothing, as I’ve tried to show in an earlier entry and hope to show in later ones.

A few portions that remained were plagued by deterioration. Usually, that consists of ameba-like creatures swarming over the image. Some decadents wallow in these miasmas, especially on tinted prints. (See Lyrical Nitrate and Decasia.) Me, I can’t romanticize turning a 1910s drama or comedy into a 1960s abstract film. I want to see the story and the style, dammit.

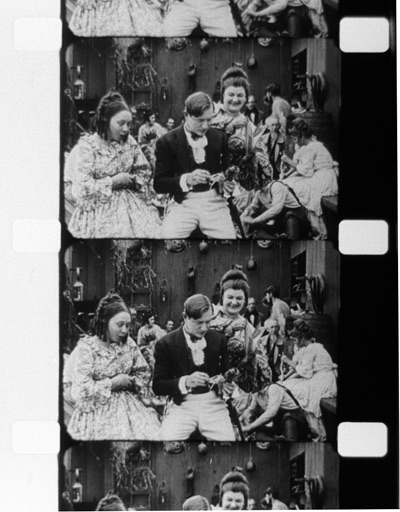

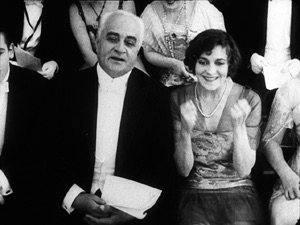

Another form of deterioration yields a ghostly, scraped-off image. Sometimes the decay changes from shot to shot, presumably because at some points the shots were segregated for tinting and toning. Here’s The Caprices of Kitty (Smalley, 1915), with Elsie Janis watching a play. In a gag on celebrity, she’s also an actor on stage (and in drag). After the nice shot of her and her father in the audience, the stage shot makes you shudder.

A first effort to clean it up with Photoshop helps, but still…Makes you remember why all that effort on the Packard Campus is necessary.

Of course a great many copies I watched were gorgeous. Orthochromatic film, with a ton of light dumped on the sets, yields images with incredibly rich gray scales. (My Ilford photochemical black and white couldn’t capture that range.) When we saw this parlor shot from By Right of Purchase, a 1918 Norma Talmadge melodrama, James blurted out, “Clutter!” A connoisseur of dense images, James later ran it through his algorithms and found that it had a spectacular degree of clutter.

Filigreed clutter is another big reason to like the 1910s, and archives like the LoC team are keeping it visible for us.

Deterioration isn’t the only insult these movies suffer. There’s the degradation of them in oft-copied versions. Compare this shot, from Reginald Barker’s splendid William S. Hart film The Bargain (1914), with the image you get if you buy the bootleg DVD.

Shot scale changes because of video cropping, facial expressions become unreadable, the eyes go dark, and that mounted trophy in the back just disappears. Of course things go a lot better with a video version of a film restored by the Culpeper crew (Moving Image Curator Rob Stone in particular). Olive Films has just released Wagon Tracks (1919), a fine William S. Hart film, on a very pretty Blu-ray derived from a tinted Library of Congress restoration.

So it can be done well, though I still prefer to study a 35 print, preferably untinted. Call me cranky.

The Packard Campus visit brought home to me how much effort is spent saving our film heritage. That heritage includes films that are little-known, but deserve better recognition. Watching with me, astonished by the technical ingenuity and wide-ranging experimentation rushing past us, James was reminded of the Cambrian Explosion, that period of origin and rapid diversification among earthly organisms.

It’s an intriguing analogy. A mere dozen years yielded “our cinema,” as I’ve argued in this video lecture–the sturdy prototypes of moviemaking today. Yet along with enduring models of story and style came a cascade of ingenious novelties that weren’t taken up much. The 1920s, for all their innovations, tended to prune away some of the more eccentric but intriguing tendencies that burst out in the 1910s. In my next entry on the subject, I’ll offer some examples.

I owe a tremendous debt to the John W. Kluge Center for supporting my stay at the Library of Congress. Thanks especially to Ted Widmer, Director of the Center, and his colleagues Emily Coccia, Travis Hensley, Callie Mosley, Mary Lou Reker, and Dan Turello. Also I enjoyed enlightening conversations with Peter Brooks, in residency at the Center, and the other Kluge Chairs Timothy Breen, Jose Casanova, and Wayne Wiegand, all embarked on fascinating projects.

Thanks also to all the staff at the Packard Campus, who enthusiastically shared information about their work habits. We’re grateful to Greg and Mike for spending so much time with us.

The digital spoor on the Packard Campus leads far and wide; a Google search will yield you many nifty items. The 2007 plans for the facility are reviewed in this information-packed presentation by Greg Lukow. For something more recent, try the Wired visit by Brian Gardiner. On the digitizing side, see Boing Boing’s extensive coverage, including an interview with Greg. There’s a good half-hour C-span documentary tour led by Mike Mashon. Mike’s blog Now See Hear! offers updates on current Campus events.

Tony Slide’s Nitrate Won’t Wait (McFarland, 2000) remains the essential source on U.S. film preservation. It has some good anecdotes about Kemp Niver, including one involving a pistol and Raymond Rohauer. Criterion has a nifty little film on wet-gate restoration of The Man Who Knew Too Much (1935).

If you’re interested in film research, you need to read James Cutting’s sweeping big-data studies on film. A good summing up of part of it is “Narrative Theory and the Dynamics of Popular Movies.” There’s interesting commentary on it here from a psychologist and here from a screenwriter (who clings to the three-act model). James’s book on the formation of the canon of Impressionist painting has been invoked in Derek Thompson’s book Hit Makers: The Science of Popularity in an Age of Distraction (Penguin, 2017), 23-26.

For more on visual clutter, see this paper on clutter and visual search, of which Tim Smith, master of eye movements, is a co-author; and two papers specifically on movies, by James, one with Kacie Armstrong: here and here.

DB makes Lillian bashful in The Lily and the Rose (1915).

Waldo Lydecker, James Schamus, and 1910s movie storytelling

Laura (1944).

DB here (in DC):

Over the next two weeks I’m involved with several events during my stay at the John W. Kluge Center of the Library of Congress. If you’re near Washington, do consider coming to one or all of these doings.

First up is a screening of a sparkling restored print of Otto Preminger’s Laura (1944), at the gorgeous Packard Campus Theater in Culpeper, Virginia on 8 March. The show, a new addition to the Theater’s spring schedule, starts at 7:00 pm, a half-hour earlier than the customary time. I’ll be giving a brief introduction.

On the following Monday, 13 March, the Kluge Center will host “James Schamus on Philip Roth and the Art of Adaptation.” After a screening of James’s directorial debut Indignation, he will participate in a discussion with the audience. I’ll play moderator. The event will take place at 3:00 pm in the Pickford Theater, on the third floor of the Library’s Madison Building, 101 Independence Ave. S.E.

James, professor at Columbia and producer and writer of many important American and Chinese films, needs no introduction to this blog’s readership. (Above, he’s with frequent collaborator Ang Lee.) We’ve celebrated his work here, and I discussed the admirable Indignation just last summer. This upcoming session should be an exhilarating afternoon.

Lastly, I’m giving a talk, “Studying Early Hollywood: The Search for a Storytelling Style.” It develops some of the issues I’ve floated in my books, other lectures, this video lecture, and most recently this blog entry. The talk is set for 4 pm. on Thursday, 16 March. It takes place in room 119, a magnificent venue on the first floor of the Library’s Thomas Jefferson Building, 10 First St. S.E.

All these events are free and open to the public, and you don’t need tickets.

Being at the Kluge Center has been very stimulating, and my research into 1910s visual style has benefited hugely from access to the LoC’s film collections. These three events are wonderful ways to wrap up a stay that has gone by all too fast. If you’re in the vicinity, come by and say hello.

Thanks to the many people who have made these events happen: At the Kluge Center Ted Widmer, Mary Lou Reker, Dan Turello, Travis Hensley, and Emily Coccia; at the Packard Campus Greg Lukow, Mike Mashon (initiator of many things), and David Pierce.

More information on the Packard Campus Theater is here. A summary of James’s vast career is here.

The Packard Campus Theatre. Photo by Glenn Fleishman.

Anybody but Griffith

Motion Picture News (19 December 1914), 148.

DB here:

For almost two months, I’ve been in Washington, DC at the Library of Congress. The John W. Kluge Center generously appointed me Kluge Chair in Modern Culture. This honor has enabled me to work with the enormous collection of the Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division to sustain my research in American narrative cinema of the 1910s.

I wanted to go more deeply into an area I mapped out in the video lecture, “How Motion Pictures Became the Movies” and in the books On the History of Film Style and Figures Traced in Light. The general question was: How did the norms of storytelling technique develop between 1908 and 1920? More specifically, I hoped to trace out an array of stylistic options emerging for the feature film. What range of choice governed staging, framing, editing, and kindred film techniques?

Theatre, but through a lens; painting, but with movement

If you’ve seen that lecture, or just followed this blog from time to time, you know that I’ve sketched out two broad stylistic trends operating at the period. One, celebrated as a breakthrough for a hundred years, involves the development of continuity editing. That trend was explored by several historians of early film, including Kristin in the book we did with Janet Staiger, The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960.

Critics and historians who saw editing as the essence of cinematic technique called the second trend “theatrical” and regressive. Directors in that trend supposedly simply planted the camera in one spot and let it run, recording performances and not bothering to cut up the scene into closer views. This “tableau” tradition was superseded by an editing-based style–and, many thought, a good thing too.

Over the last twenty years, however, scholars have reappraised that apparently static and passive camera. Lea Jacobs and Ben Brewster’s trailblazing book, Theatre to Cinema: Stage Pictorialism and the Early Feature Film (1997) traced film’s many debts to theatrical plotting, set design, and especially performance. In a parallel series of articles, Yuri Tsivian proposed that the “precision staging” of the 1910s had deep affinities with traditions of painting and visual culture. Lea, Ben, and Yuri showed that the tableau tradition offered rich creative choices to filmmakers.

For my part, I was concerned to explore how ensemble staging worked in a moment-by-moment fashion to call the viewer’s attention to key aspects of the action. Editing does that by cutting to closer views. In the tableau method, emphasis arises from composition, movement, and other pictorial strategies.

In light of all this research, it seems clear that during the 1910s the tableau strategy developed into a powerful expressive resource. After Figures Traced in Light (which found the tradition still alive in directors like Angelopoulos and Hou), I continued to collect examples of creative staging at this early period. The results led me to analyze films by Yevgenii Bauer, Danish directors, and other Europeans.

Evidently the tableau persisted until 1920 or so in Europe, especially Germany, but the editing-centered option had already become dominant in America. But how long, and in what ways, did tableau methods hang on in the US? Or was the switchover quite quick? By 1917, Kristin had posited, continuity editing had crystallized as the primary storytelling style. I thought I’d try some depth soundings of the period.

Evidently the tableau persisted until 1920 or so in Europe, especially Germany, but the editing-centered option had already become dominant in America. But how long, and in what ways, did tableau methods hang on in the US? Or was the switchover quite quick? By 1917, Kristin had posited, continuity editing had crystallized as the primary storytelling style. I thought I’d try some depth soundings of the period.

Since my time was limited, I had to focus. Charlie Keil’s superb Early American Cinema in Transition: Story, Style, and Filmmaking 1907-1913 (2001) analyzed a great many films of that phase in depth, particularly with respect to editing techniques. So I thought I’d start with 1914 and simply try to see as many features from that year as I could. I then would sample items from later years. My only rule was to watch films that aren’t part of the canon–no Griffith, Chaplin, Fairbanks, Pickford, Fatty et al. I did, however, try to see rare things by Lois Weber, Reginald Barker, and other well-regarded filmmakers.

What did I come up with? I’m still watching and thinking, but let me share a few items that excite me. Clearly, despite plenty of audacious editing, the tableau technique was alive and well in America in 1914-1915. And the more I see, the more I’m inclined to rethink the terms under which I value Mr. D. W. Griffith.

Tableau trickery

A simple illustration of how a fairly distant tableau can vividly guide our attention shows up in The Case of Becky (1915), directed by Frank Reicher.

Before an audience, the sinister hypnotist Balsamo hypnotizes Becky. From a deck of cards he has selected the ace of hearts, and in her trance she has to find it. There’s almost no movement in the frame: Balsamo stays frozen, as does Becky, except for her one hand flipping over the cards.

No need for a close-up: With Balsamo as still as a statue, every viewer will be watching that tiny area of the screen occupied by her hands, and we wait for her to find the ace. When she does, Balsamo accentuates her minimal gesture by twisting his arm and freezing into another pose.

Is this, then, simply filmed theatre? Not really. First, many tableau framings, like the Case of Becky instance, put the actors closer to us than stage performers would be.

Just as important, the perspective view of the camera yields a chunk of space very different from that of proscenium theatre. In cinema, for instance, depth is more pronounced, and actors can be shifted around the frame to block or reveal key information. This isn’t pronounced in the Case of Becky example because the two characters are more or less on the same plane and the background is covered by curtains. But consider this shot from The Circus Man (1914), by Oscar C. Apfel.

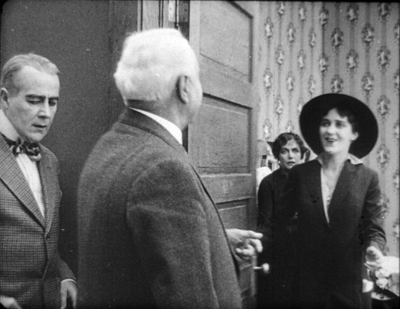

The circus owner Braddock has been sent to prison for murder and attempted robbery, a plot engineered by Colonel Grand. Now Braddock has served his sentence, and in a scene too complex to trace entirely here (but maybe in a later entry), he bursts in past the butler to confront Grand. Here’s what we see.

Such a scene would be inconceivable on the stage because of the audience’s sightlines. People sitting in the left side of the auditorium couldn’t see Braddock’s entrance, because he’d be concealed by Grand, who’s standing in the foreground left. Audience members on the right side of the auditorium couldn’t see Braddock either, because Mrs. Braddock and David are standing on the right foreground.

The shot makes sense from only a very limited number of points, only one of which is occupied by the camera. Maybe a few people in the center of the theatre would have a fairly clear view of such an action, but as we’ve seen with The Case of Becky, they wouldn’t be so close to the players.

The sheer fact of optical projection means that cinematic space is narrow and deep, while stage space is broad and (usually) fairly shallow. On the stage, players tend to be spread out laterally, allowing for many sightlines. Cinematic staging can be deep and diagonal.

On the other hand, the tableau shot isn’t perfectly analogous to a painting. While the lens chops out a perspectival pyramid in three dimensions, the movement in the frame creates a two-dimensional flow–a cascade of planes and edges very different from what we’d get in a painting. This flow can be used to reveal or conceal bits of space as the action develops.

You can see this compositional flow clearly in an earlier phase of the Circus Man sequence. Before Braddock bursts in, David has been arguing with Colonel Grand in the foreground. David’s and Grand’s heads occupy the area that Braddock will soon claim. Just before that entrance, Mrs. Braddock pulls David back a bit to the right, and Grand recoils fractionally to the left. This creates a hole that Braddock can come into (as above).

This sort of slight shifting is akin to what we see in the astonishing poorhouse sequence of Victor Sjöström’s Ingeborg Holm (1913), analyzed here. Clearly the Americans were executing the same sort of choreography as the Europeans, which turns the static image of a painting into something more dynamic, a sort of micro-dance.

Flo and flow

The married couple Lois Weber and Phillips Smalley are responsible for a little masterpiece of early cinema, Suspense (1913), which I’ve discussed here. It’s become a classic largely because its audacious close-ups and cutting seem to anticipate classic Hollywood style. But seeing, or sort of seeing, two other films by Weber and Smalley suggest that they were no less adept at the tableau method.

I say “sort of seeing” because the copy of Sunshine Molly (1915) was so deteriorated that in long stretches only faint outlines of the people and locales were visible. The plot was pretty clear, but the images were so blotchy that only a few furnish clear frames. Still, it would seem to have been quite a good film. With False Colours (aka False Colors, 1914), two or three reels were missing. But what was there was pretty spectacular, and one scene is really striking if you’re interested in staging.

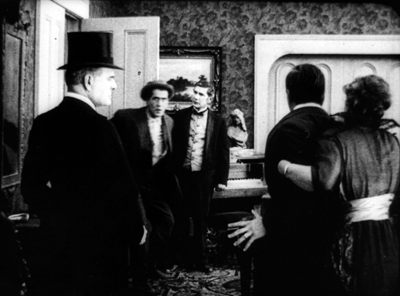

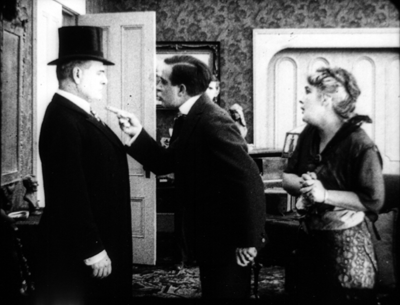

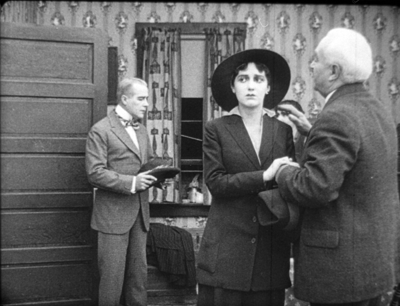

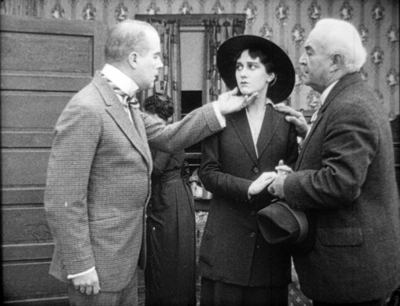

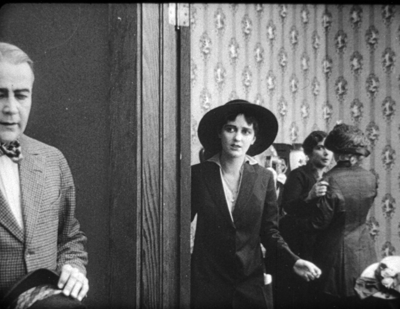

As with The Circus Man, at first glance things look stagebound. Dixie’s long-separated father comes to the foreground where she stands waiting with the theatrical manager. He abandoned her as a baby, and now that she’s found success as an actress she spurns him.

But no stage arrangement could yield the layout we get in this shot. While father and daughter and manager occupy the “forestage,” we see Flo, who has impersonated Dixie in an effort to get the father’s money, step into the gap. (Flo is played by Lois Weber.)

Thanks to the depth of the “cinematic stage,” we get what Charles Barr calls “gradation of emphasis”–not just two layers of space, as in The Circus Man, but action and reaction in depth, as we wait for the foreground action to develop. That action hits its high point when the father touches Dixie’s chin.

This gesture partly masks Flo, who briefly turns away as well. The emphasis falls firmly on the father’s contrition. Dixie still refuses him, and so he says farewell, re-exposing Flo turning in the background.

As he departs, so that we get the full force of his encounter with Flo, Dixie turns from the camera. We must concentrate on the moment in the background when the imposter shows remorse for having won the love of the man she deceived.

At the door

You might object: “But David! Those examples are still very stagebound. The Case of Becky shot is itself on a stage, and the others, despite all their depth, show boxlike rooms from straight on. They seem firmly tied to a proscenium concept. Shouldn’t we expect something more natural?”

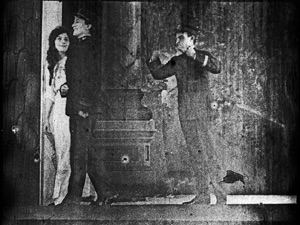

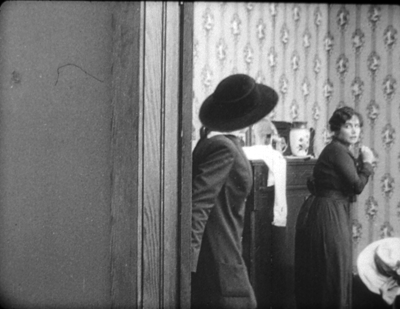

Fair enough, so I submit this earlier phase of the False Colours scene. This time we have a doorway, framed diagonally, that cuts off a lot of playing space. And we see obliquely into a corner of a room, not straight on to a back wall. Yet you still get an interplay of faces and bodies, carrying to a daring extreme the blocking-and-revealing tactics we’ve seen in The Circus Man and in the later phase of the False Colours scene.

Dixie comes to Flo with Flo’s mother. At this point Flo recognizes Dixie as the daughter she’s been impersonating and is deeply ashamed. You won’t be surprised by the dazzling precision of the frontal placement of Flo, no matter how far she is from the camera.

Flo is consoled by her mother, and Dixie shuts the door discreetly.

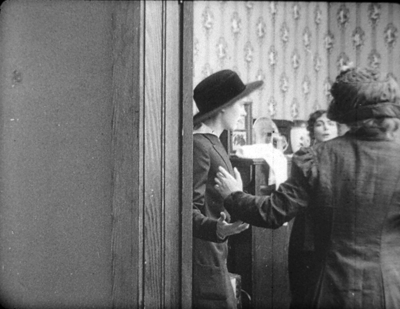

But why so much empty space on the left of the door? Because now the theatre manager is coming, and the framing shows us what Dixie doesn’t know: Her father is standing there alongside the manager.

There’s a moment of suspense before the father hesitantly steps to the doorway and Dixie sees him for the first time in seventeen years.

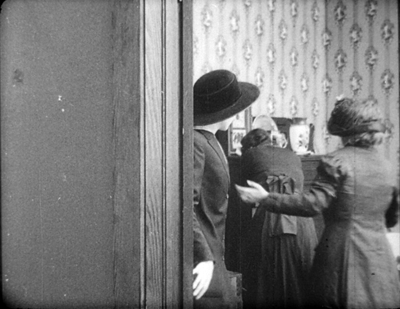

He blots out everything but her reaction, until Flo’s face slides into visibility. Cornered, she’s terrified to be confronting the man she has deceived.

The father’s valet has obligingly slid into the left to balance the frame, but he stands as frozen as the hypnotist Balsamo had been, looking patiently downward, to make sure we concentrate on the pitch of drama taking place in the distance. This is as purely “cinematic” a scene as anything involving editing.

And who needs close-ups?

Griffith is a great director, but other filmmakers of his period were exploring cinematic possibilities he didn’t consider. Their editing is often more subtle and careful, and the exponents of the tableau style achieve a pictorial delicacy mostly at variance with his work.

More and more, this Founding Father of Hollywood seems to me an outlier–an eccentric, raw, occasionally clumsy filmmaker who went his own way while others refined a range of stylistic practices. I’m starting to think he favors a brute-force approach, in both physical action and the evocation of sentiment. The result is powerful, but… Well, I’m reluctant to say it, but after my two months of immersion in Anybody But Griffith, he’s starting to seem somewhat crude.

I’m tremendously grateful to the John W. Kluge Center, and particularly its director Ted Widmer, for enabling me to conduct this research under its auspices. A special thanks to Mike Mashon of the Motion Picture Division, and all the colleagues who have been helping me in the Motion Picture and Television Reading Room: Karen Fishman, Rosemary Hanes, Dorinda Hartmann, Zoran Sinobad, and Josie Walters-Johnston.

Ben Brewster and Lea Jacobs’ Theatre to Cinema is available for download here.

For our blog entries relevant to the tableau tradition, go here. Lois Weber made many other important films, notably Hypocrites (1915), Where Are My Children? (1916), Shoes (1916), and The Blot (1921). See the exceptionally detailed Wikipedia entry for more information.

False Colours (1914).