Archive for the 'Tableau staging' Category

Il Cinema Ritrovato, number 9 and counting

Kristin here:

For a second year running I unexpectedly ended up attending Il Cinema Ritrovato in Bologna alone. (For the 2012 report, see here.) Last year David’s back went out shortly before we were due to leave. This year an exceptionally long stretch of days with heavy thunderstorms resulted in flooding in our basement (where many of our books reside). I had already been in London for nearly three weeks and was planning to meet David in Bologna. Instead, he valiantly stayed home to deal with the unwanted water, and I went on to the expanding smorgasbord of films presented by the festival.

The programmers are limited to their existing venues: the relatively small Mastroianni and Scorsese auditoriums in the Cineteca’s building, the larger Arlecchino and Jolly commercial cinemas, and the vast space of the Piazza Maggiore for the nightly open-air screenings starting at 10 pm. This year for the first time, to accommodate the many films, post-dinner screenings, starting at 9:30, 9:45, or 10 pm, were scheduled in the Scorsese and Mastroianni.

Faced with so many options, one could only focus on a few of the bounteous threads of programming. I opted to see as many of the early Japanese sound films as possible, the early (pre-mid-1960s) Chris Marker works, and the annual Cento Anni Fa series, this year presenting a sampling of films from 1913, the year when worldwide the cinema seemed to take an extraordinary leap forward in complexity and inventiveness. Whenever there was a gap, I could fit in items from the other threads: European widescreen movies; cinema of the 1930s that presaged the coming war; a retrospective of the work of Soviet director Olga Preobrezhenskaja, another devoted to Vittorio de Sica, primarily as an actor, more Chaplin restorations from the Cineteca’s ongoing project, the newly restored Hitchcock silents, and of course various other newly restored films. A tradition of highlighting the work of a Hollywood director has become a centerpiece of Il Cinema Ritrovato, with the subject this year being Allan Dwan.

Japanese Talkies, Part 2

Last year I caught only a few of the films in the retrospective of early Japanese sound films. I regretted not being able to see more, but the Ivan Pyriev and Jean Grémillon threads lured me away. This year the rival was Chris Marker, but I determined that by careful planning, I could fit almost everything in both retrospectives into my schedule. These became my top priorities.

The Japanese series is ongoing and organized not by auteurs but by film companies. The programmers were again Alexander Jacoby and Johan Nordström, whose encyclopedic knowledge of the history of Japanese studios of the 1930s made  for fascinating introductions. This year it was PCL and the very obscure company JO, both of which made American-style musicals in the early and mid-1930s. These were not the best films in the season, but they were highly entertaining. This series also had the advantage of being presented entirely in 35mm and with English subtitles devised years ago for traveling retrospectives.

for fascinating introductions. This year it was PCL and the very obscure company JO, both of which made American-style musicals in the early and mid-1930s. These were not the best films in the season, but they were highly entertaining. This series also had the advantage of being presented entirely in 35mm and with English subtitles devised years ago for traveling retrospectives.

I had seen only one of the films in the series, Mikio Naruse’s 1935 masterpiece, Wife, Be like a Rose. I didn’t remember much about it, except that it was marvelous, and it proved so on second viewing. Naruse often has been compared with Ozu, both during his active career and since. Overall, he seems to me not as great a filmmaker, but Wife, Be like a Rose must be among his best films and would undoubtedly rank alongside some of Ozu’s work of this period. A moga (modern girl) is upset that her father has deserted his family in Tokyo and established another family in the countryside. Determined to drag him back to his familial responsibilities, the daughter confronts the possibility that he was right in leaving her mother. The film is shot in a somewhat Ozu-like style, with low camera heights and across-the-line shot/reverse shots. Still, there is no slavish imitation (the climax is filled with camera movements), and Naruse’s film is both moving and stylistically engaging.

Naruse was the only director with two films in the retrospective. His Five Men in the Circus, also released in 1935, was a less ambitious work than Wife, Be like a Rose, but it was an entertaining story of musicians on the road earning a living during the Depression, encountering disappointments in work and love.

Naruse has already gained a modern reputation in the West, but for some the discovery of the season was Sotoji Kimura, whose Ino and Mon was well received. As with so many of this thread’s films, its subject was a modern girl struggling with tradition. Mon, who has become pregnant and doesn’t want to marry her child’s father, returns to her country home and faces sullen opposition from her much beloved but fiercely traditional brother Ino. Aside from its realistic depiction of the countryside, the film is notable for its Soviet-style scenes of work on a nearby construction project supervised by the siblings’ father (left).

Naruse has already gained a modern reputation in the West, but for some the discovery of the season was Sotoji Kimura, whose Ino and Mon was well received. As with so many of this thread’s films, its subject was a modern girl struggling with tradition. Mon, who has become pregnant and doesn’t want to marry her child’s father, returns to her country home and faces sullen opposition from her much beloved but fiercely traditional brother Ino. Aside from its realistic depiction of the countryside, the film is notable for its Soviet-style scenes of work on a nearby construction project supervised by the siblings’ father (left).

The Japanese musicals were all charming films. Romantic and Crazy (1934) starred the popular comic performer Kenichi Enomoto, better known as Enoken. (In the West, he is most familiar from his comic role in Akira Kurosawa’s third feature, The Men Who Tread on the Tiger’s Tail [1945].) Romantic and Crazy is basically a college musical imitating the early 1930s films of Eddie Cantor–and at  moments I wished I were watching an Eddie Cantor musical. The other two musicals–Tipsy Life (Sotoji Kimura, 1933) and Chorus of One Million Voices (Atsuo Tomioka, 1935)–were quite entertaining. Clearly the filmmakers felt no compunction about stealing recent American songs and setting the tunes to new Japanese lyrics. The most popular seemed to be “Yes, Yes, My Honey said Yes, Yes!” as sung by Cantor in the 1931 musical Palmy Days; the tune was heard in at least two of the films.

moments I wished I were watching an Eddie Cantor musical. The other two musicals–Tipsy Life (Sotoji Kimura, 1933) and Chorus of One Million Voices (Atsuo Tomioka, 1935)–were quite entertaining. Clearly the filmmakers felt no compunction about stealing recent American songs and setting the tunes to new Japanese lyrics. The most popular seemed to be “Yes, Yes, My Honey said Yes, Yes!” as sung by Cantor in the 1931 musical Palmy Days; the tune was heard in at least two of the films.

Another notable film was Sadao Yamanaka’s Kôchiyama Sôshun (1936), one of his three surviving feature films. (These and fragments of others are available on a new set from Eureka! in its “Masters of Cinema” series.) It’s a strange film, partly comic but mostly a crime story. An attractive woman, played by a very young Setsuko Hara, keeps a shop owned by a local gangster, and tries to prevent her thuggish younger brother from becoming a criminal. The title character, Kôchiyama Sôshun, appears to be an idler getting by on the income from his wife’s gambling house, but he apparently has unlimited sources of money. Despite his shady background, Kôchiyama tries to help save the heroine when, after her brother has gambled away the house and shop, she is forced to sell herself into prostitution.

The seasons of early Japanese sound films will continue during the 2014 Il Cinema Ritrovato, with a focus on Shochiku.

Chris Marker’s youth returns

It has been difficult to see any of Chris Marker’s early films lately. By early I don’t mean early 1950s, but essentially anything made before La jetée (1962). As Florence Dauman of Argos Films explained in an introduction to one of the programs, Marker thought of the films made during his first decade as a director as mere trials and didn’t want them seen again. Fortunately Dauman and others made the decision not to honor his wishes. Perhaps Marker thought that his later films, more complex and philosophical (Sans soleil comes to mind), were how he wanted to be remembered. But the playful, emotional, politically committed film essays of the 1950s and early 1960s are precious and not to be abandoned. We were treated to excellent restored prints of them during the festival.

The only film that made me understand Marker’s reluctance to show his early work was Olympia 52 (1952), a documentary on the Olympic Games in Helsinki. It was Marker’s first professional feature, and it is barely competent. The coverage sticks almost entirely to the track and field events, with endless 100-meter dashes, shot-puts, hurdles, high jumps, pole-vaults, and so on. The several cameras filming the events rendered very different footage, ranging from excellent to dark gray. Cut together, these shifting images look amateurish. A brief series of shots of yacht-racing, equine-jumping, and other sports leads back to more shot-puts, hurdles, pole-vaults, and so on. Valuable practice for Marker, no doubt, but a film which bears no hint of the talent soon to burst forth.

It was wonderful to see Letter from Siberia (1958) again after so many years. David and I had taught it in an introductory class in the mid-1970s. Its repeated series of shots of a bus on a street and some men doing construction work has been an example of the powers of the sound track from the very first edition of Film Art in 1979 to the present one.

There were no subtitles on the prints, and the headphone translation could never keep up with the rapid, contemplative voice that accompanied these images, so I missed much of the point of Dimanche à Pékin (1956) and Description d’un Combat (1960). Marker’s written contribution to Joris Ivens’ documentary …À Valparaiso (1963) presaged much of his later work. His 16mm documentation of American hippies’ gently protesting assault on the Pentagon in La sixiéme face du Pentagone (1968) made me proud to be an American (something not too easy in the light of recent events).

Dwan at his peak? The 1920s

I missed most of the Dwan films, but I managed to fit in three of the four from the 1920s. These did not include the 1923 Gloria Swanson vehicle Zaza, alas, though I heard good things about it from friends who saw it. The three I caught seemed to represent Dwan at the height of his career.

I had seen the other Swanson film, Manhandled (1924) before, but it was a treat to see it again. It’s a strange mixture of realism–most notably in the famous early scene of the working-class heroine’s commute home on a crowded subway–and an absurdly melodramatic plot in which she manages to attain the pampered stature of a kept woman while maintaining her virtue. Swanson is a delight, and the fact that the film is incomplete, missing a scene in which she demonstrates her talent for mimicry by imitating various characters, including Charlie Chaplin, is a true pity. We can only hope that a complete version will someday surface.

Dwan’s 1927 melodrama, East Side, West Side, was a considerable surprise. For a director who has a reputation for making B picture in the sound era, this high-budget production seemed remarkable. The production design and cinematography were excellent, and a ship accident scene done with models was unusually convincing. The print was a fine restoration by the Museum of Modern Art. The Iron Mask (1929, above) was introduced by Kevin Brownlow (right), who had helped supervise the restoration.

Dwan’s 1927 melodrama, East Side, West Side, was a considerable surprise. For a director who has a reputation for making B picture in the sound era, this high-budget production seemed remarkable. The production design and cinematography were excellent, and a ship accident scene done with models was unusually convincing. The print was a fine restoration by the Museum of Modern Art. The Iron Mask (1929, above) was introduced by Kevin Brownlow (right), who had helped supervise the restoration.

As always it was a treat to hear anecdotes from the man who had the inspired idea of interviewing stars and filmmakers from the silent era before it was too late. The Iron Mask was another impressive print, dated 1999 and bearing a Carl Davis score. I much prefer Douglas Fairbanks in his early comedies to his more famous swashbuckler films, and the story and staging in this one seemed very by-the-numbers, especially in comparison to the more imaginative East Side, West Side. Its main interest, and that was considerable, lay in the impressive sets designed by Ben Carré and William Cameron Menzies and its glowing cinematography by Henry Sharp.

By the end of the week, I was happy to have caught these particular Dwan films. From conversations with people who followed his thread more closely, I gathered that they thought the 1920s titles were the best of those shown in Bologna.

Glimpses of 1913

There was a time when the Cento Anni Fa series, programmed by Mariann Lewinsky, was a must-see for me. With the proliferation of screenings, however, seeing all of the sessions has become difficult, and I found myself ducking in and out to catch a few items now and then. I wanted to see the new restoration of Mario Caserini’s remarkable feature, Ma l’amor mio non muore!, but there was something else I wanted to see playing opposite both screenings. Luckily the Cineteca has put the film out on DVD. The catalog claims that it’s the first diva film. It stars Lyda Borelli in a spectacular performance, plus it has many complex examples of what David calls tableau staging (see here), especially in the amazing set in the frame above. One of the must-see films of 1913.

I am not a great fan of Italian (or any other) spectacles set in ancient times, and there were quite a few included in the series. They also tend to be rather long, which makes it more difficult to fit them into a packed schedule. Still, I did like Spartaco ovvero il gladiatore della Tracia (Giovani Enrico Vidali). Its minor actors and extras avoided giving the usual impression of people milling around in sets; they actually behaved as if they were living in real places in antiquity. The actress playing Emilia (not listed in the catalog) gave an engaging performance, quite the opposite of the diva approach, though Mario Guaita as Spartaco depended largely on rolling his eyes upward at frequent intervals to convey suffering. As Ivo Blom points out in his program notes, however, Guaita turns out to be the the first strongman figure, bending iron bars with his hands a year before Bartolomeo Pagano supposedly innovated this iconic gesture as Maciste in Cabiria.

More than that film, though, I was impressed by Luigi Maggi’s La lampada della nonna. It begins with an old woman knitting beside an oil lamp. When her grandchildren try to present her with a new electric one, she objects. The bulk of the film is an extended flashback set in the era of the Risorgimento, with the heroine in her youth helping to shelter a wounded officer and falling in love with them. The lamp, seen unobtrusively in the background of several shots, comes to play a key role as a signal in the climactic scene. Again there is an unusual degree of naturalness in the acting, with the extras in the military campground scene, for example, all given bits of plausible action to collectively present the impression of an actual campground. The flashback structure, framing, staging, and acting all reminded me strongly of Griffith at the same period.

There were slight but charming films like Léonce et Toto, a very funny Léonce Perret comedy (director unknown, but probably Perret). Léonce’s wife receives a tiny chihuahua as a gift and immediately dotes on it, to the point of putting it on the table at meals. The hero is disgusted and tries increasingly devious and extreme ways of getting rid of the little pest. Another was an American documentary with the irresistible title Aquatic Elephants. Who would not delight in five minutes of elephants rolling cheerfully in a pond while silly men try to stand on them and invariably fall into the water?

DVDs and Blu-ray

Just about every film scholar and buff in the world probably knows the Criterion Collection. As a brand, it’s sort of the Pixar of high-end home-video. We all have at least some of its releases on our shelves, whether lined up alphabetically or by director or by number. This year a session was devoted to the background of the company, with guests Jonathan Turell and Peter Becker (left and right, above). The history of Criterion is a bit complicated. Briefly, it was founded in 1984 to release laserdiscs and eventually, after the introduction of DVDs in 1997, switched to that format, eventually adding Blu-ray discs. Becker joined the company in 1993.

Criterion is closely linked to the historically important Janus Films, founded in 1956 and responsible for distributing many of the most famous art films of subsequent decades. In 1966 it was acquired by Saul J. Turell and William Becker, the fathers of the two speakers. Their sons are now co-owners of the Criterion Collection, of which Peter is the president; Jonathan is director of Janus.

To David’s and my generation of film students, Janus was a key player in our discovery of art cinema. How many of us, I wonder, first watched many of the classics that now grace Criterion DVDs through the landmark PBS series, “Film Odyssey,” in 1972? I first saw and was bowled over by Ivan the Terrible in that series. Three years later, when I was working on my dissertation on the film, I called Janus and got through to Saul Turell. Could I possibly borrow 35mm prints of the two parts of the film, I asked, explaining that I needed and to take frames from good copies. He gave me the name and phone number of a person in the company’s storage facility to call, and she arranged to ship the prints to me. I was able to spend weeks in front of a Steenbeck in the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research, wallowing in strange, beautiful images and sounds. Nearly all the illustrations in my book, Eisenstein’s Ivan the Terrible, were taken from those prints.

That same spirit of cooperation with academic film studies has lived on. David and I are grateful for our friendly relationship with the Criterion team, who have cooperated in our creation of video-based online examples tied to Film Art: An Introduction. (The examples all come from Janus films; a sample analysis of a clip from Vagabond is available on YouTube.)

The pair’s presentation included a video, The Criterion Collection in 2.5 Minutes. It features over 600 clips from the collection as of September 1, 2012, chosen and edited by Jonathan Keogh, clearly one of the company’s most devoted fans. Although cut too fast too allow the viewer to identify every title (and I must admit, I don’t think I could recognize every single one, even with longer excerpts), it’s an exhilarating paean to great cinema.

The plaudits in the festival’s annual DVD contest were spread, deliberately or not, among many DVD/Blu-ray companies, with none winning more than one award. A number of items that we’ve covered here took home awards: Flicker Alley’s collection of films by the Russian firm in Paris, Albatros, was deemed the best boxed-set of silent films; and Edition Filmmuseum’s set of four Asta Nielsen films shared the award for best rediscovery. Our friends at the Belgian Cinematek won best Blu-ray boxed set for the “Henri Storck Collection.” Criterion took home best Blu-ray for its edition of Paul Fejos’s Lonesome. For these and the other winners of this year’s DVD awards, see Jonathan Rosenbaum’s website. (As one of the jurors, he explains the changes in the award categories this year.)

The Return of Carbon Arcs

I’m old enough to remember when carbon-arc projectors were the norm. Gradually xenon lamps replaced them, starting in 1956. This year, the festival put on two outdoor screenings in the courtyard of the Cineteca’s building. These started at 10 pm, so they competed with the bigger shows in the Piazza Maggiore. I usually don’t go to the Piazza screenings, since they tend to end late, and I don’t want to fall asleep during the 9 am screenings the next day. But the two programs, billed as “Il Cinema ambulante Ritrovato. Tesori dal Fondo Morieux,” were considerably shorter, so I attended the first one. As the name suggests, the idea was to simulate a traveling cinema of the early era. The first screenings included one Pathé film from 1904 and five others from 1906, some with hand-stenciled color. All six were rediscovered titles.

I’m old enough to remember when carbon-arc projectors were the norm. Gradually xenon lamps replaced them, starting in 1956. This year, the festival put on two outdoor screenings in the courtyard of the Cineteca’s building. These started at 10 pm, so they competed with the bigger shows in the Piazza Maggiore. I usually don’t go to the Piazza screenings, since they tend to end late, and I don’t want to fall asleep during the 9 am screenings the next day. But the two programs, billed as “Il Cinema ambulante Ritrovato. Tesori dal Fondo Morieux,” were considerably shorter, so I attended the first one. As the name suggests, the idea was to simulate a traveling cinema of the early era. The first screenings included one Pathé film from 1904 and five others from 1906, some with hand-stenciled color. All six were rediscovered titles.

They came from the remarkable 2006 find of a wealth of films, equipment, posters, and even sets and puppets, in a warehouse in Belgium. The collection all originated from the stock of the traveling Théâtre Morieux, which had started with puppet and magic-lantern programs, adding films in 1906. All this material had been in the warehouse for a century and was in good condition.

The projector used for the program was not from 1906, but it was old, and very heavy. I happened to be between films when a truck with a crane delivered the projector and a generator and a team set up the equipment facing a small screen on one side of the courtyard. (At the very top of today’s entry, the crane lowers the projector body onto its platform. Above, festival coordinator Guy Borlée watches as the lamp housing is attached. Bottom, all ready to go and waiting for the sun to set.) The projector was a Prevost, of French manufacture, I would guess from the 1940s.

When 10 pm arrived, it became apparent that the light from buildings near the Cineteca could not be entirely controlled. Shadows of the trees in the courtyard were cast on the screen, with light patches between them. But traveling cinemas no doubt frequently set up in venues where nearby sounds and other distractions abounded, so we all accepted the light pollution as part of the experience.

Perhaps the most memorable of the films was Cambrioleurs modernes (“Modern Burglars,” director unknown, 1904). In some ways it was rather crude, with the set consisting of two large painted house façades facing each other, angled from the front, and a wall beyond them. The acrobatic burglars arrived over the wall to rob one house, propping a long board against an upper window to use as a chute for sliding furniture and other large objects down.

The action becomes faster and more impressively choreographed as police arrive, also over the wall, and give chase. Soon burglars and comic cops are diving through windows and doors in the two buildings, as well as performing comic acrobatics on the chute. The whole thing, as far as I could tell, was done in a single take, though there might have been some invisible cuts. If it was indeed one shot, it was a most impressive piece of staging and performance.

This ‘n’ that

Jean-Pierre Melville’s 1963 crime/road movie L’Aîné des Ferchaux (based on a minor Georges Simenon novel) is almost impossible to see on the big screen, apparently due to some sort of rights problem that keeps the French distributor from circulating it. (It is available on a region 2 French DVD without subtitles.) The festival managed to show it in the European widescreen thread by borrowing a print from Svenska Filminstitutet, complete with Swedish subtitles. Translations in Italian and English were projected on small screens below the image. I quickly got accustomed to skipping down to the read the third set of subtitles. It’s certainly not one of Melville’s masterpieces, but it’s definitely worth seeing.

The basic premise is that an unscrupulous banker, Dieudonné Ferchaux (veteran French star Charles Vanel), flees arrest by flying from Paris to New York and then setting out toward the South via car. Michel Maudet, an unsuccessful young boxer (Jean-Paul Belmondo), also unscrupulous but so far with no apparent serious crimes to his name, goes along as his secretary. Although the two seem to like each other, Michel becomes increasingly tempted to steal the suitcase stuffed with cash that Ferchaux has picked up in New York, while Ferchaux seems to lose interest in visiting various other places where he has stashed away large sums. The gradual switch in their power relationship furnishes one main line of interest.

The film is also remarkable in that the two stars did not go to the U.S.A. to appear in the considerable amount of landscape footage shot there by a second unit. Instead, they worked in interior sets in France, as well as exteriors that pass for America. Melville managed to stitch these two kinds of footage into a reasonably convincing depiction of an American road trip.

Another film that has long been hard to see outside Italy, at least in its original form, is Rossellini’s L’Amore (1948), two contrasting short tales displaying the acting talent of Anna Magnani. The first, Une voca umana, is based on Jean Cocteau’s  much-adapted short play, La voix humaine. Confined to an apartment, it concentrates on a woman talking on the phone with the lover who has recently left her, trying to convince him that she has adjusted to the break-up while demonstrating through her behavior that she is devastated. Rossellini never places the camera much further back than a plan-américain position, and most of the time the framing displays Magnani’s face in close-up. Short though it is, it becomes repetitive, and it is too evidently a display of virtuoso acting.

much-adapted short play, La voix humaine. Confined to an apartment, it concentrates on a woman talking on the phone with the lover who has recently left her, trying to convince him that she has adjusted to the break-up while demonstrating through her behavior that she is devastated. Rossellini never places the camera much further back than a plan-américain position, and most of the time the framing displays Magnani’s face in close-up. Short though it is, it becomes repetitive, and it is too evidently a display of virtuoso acting.

The longer second part, Il Miracolo, is more engaging and original. It is based on an idea by Fellini and a script by Tullio Pinelli and Rossellini. A feeble-minded homeless woman, Nannina, who is tending a herd of goats near a small Italian village, meets a traveler (played by Fellini, left) whom she, being very pious, assumes to be St. Joseph. He offers her wine and, when she falls asleep, rapes her. Learning that she is pregnant, and not realizing what the traveler did, Nannina becomes convinced that she is carrying the baby Jesus. She is teased and hounded by the townspeople. This part of the film led to censorship problems, not because of the sexual content (the rape is simply skipped over and merely implied) but because of the apparent parody of the Immaculate Conception. (This, too, has been available in a mediocre copy without subtitles on an Italian DVD.)

Apart from its innate interest, L’Amore is historically important for the “Miracle Decision” in the U.S., where it was banned for sacrilege. The Supreme Court decision in the case led to the extension of first-amendment protection to cinema.

Il Cinema Ritrovato has become a venue for the exhibition of the latest restorations by Martin Scorsese’s World Cinema Foundation. This organization restores films from countries whose archives do not have the means to do such work. Since 2007, the foundation has preserved on average three films a year. This year the items on show at Bologna included Filipino director Lino Brocka’s Manila in the Claws of Light (1975, also known as Manila in the Claws of Neon). I had never seen a Brocka film (it’s discussed in a passage of Film History: An Introduction, for which David was responsible), but I was impressed by this one, widely considered to be his best.

It follows a naive young man from the countryside whose girlfriend has become the victim of sex-trafficking; he seeks her in Manila and experiences unfair wage practices and other forms of corruption. Brocka managed to blend seamlessly an absorbing narrative with sympathetic characters and an undercurrent of bitter social critique. Remarkably, Brocka also shot a 22-minute making-of documentary, quite similar to modern DVD supplements, that explains how he created realistic scenes of construction work with a small budget and shooting on location with non-professionals.

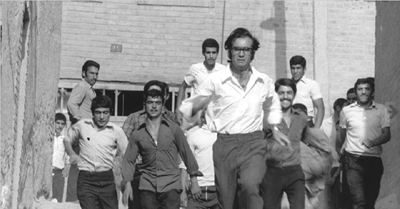

Another World Cinema Foundation restoration shown this year is the 1971 classic, Ragbar (Downfall, directed by Bahram Bayzaie). Given the extraordinary burst of creativity that has occurred in Iranian filmmaking since the 1980s, I had high hopes for this. In some ways it resembles more recent classics, most notably in its setting in a school.

The hero is a misfit who has come to teach at the school and becomes the victim of pranks and taunts by his unruly students. A rumor gets started that he is in love with the older sister of one of the students, and in attempting to scotch the rumor, he falls in love with her. Gradually he comes to understand his students and gain their respect. The film is entertaining, though the slim plot seems dragged out too long. The approach is more like commercial mainstream art cinema than like more recent Iranian films. Culturally it is quite interesting, showing some of the customs of the era shortly before the overthrow of the Shah. Most notably the women wear western-style clothes, and some are unveiled.

Unfortunately I had to miss a third Foundation restoration, Ousmene Sembène’s early short Borom Sarret (1969).

The World Cinema Foundation screenings are among the high points of Ritrovato, and I look forward to seeing more of them in years to come. Among all the festival’s restorations of well-known classics (this year Hiroshima mon amour, Richard III, and so on), it was a pleasure to see as well some well-known but hitherto difficult to see films. I hope all three, plus Brocka’s making-of, are included in a future WCF DVD set. (The first set was issued last year and is available from amazon.fr.)

Finally, I managed to see a few of the films in the “War Is Near: 1938-1939” thread. One was a program of three of Humphrey Jennings’ less familiar documentaries, all from 1939: Spare Time, about how working-class people spend their leisure time; The First Days, on the preparations for war in England after its declaration; and S. S. Ionian, on a cargo ship paying visits to ports of call in the Mediterranean. The first two had the true Jennings touch, looking at everyday events with a fresh, unpretentiously poetic viewpoint. The third was more conventional, aimed at presenting information about the importance of non-military shipping for the war effort. All three films, along with a dozen others, are available on the first volume in the BFI’s region-free DVD edition of Jennings’ complete films.

I also saw Edmond T. Gréville’s Menaces (1940). Its story of impending war is what David would call a network narrative, set among the residents of a cheap Parisian hotel–a sort of low-rent version of Grand Hotel. Although most of the stories are not directly about the war, its threat hovers over them all. Perhaps the stand-out is Prof. Hoffman, a disfigured emigré German war veteran (Erich von Stroheim) who gradually realizes that once war breaks out, he will be an enemy alien in the country he considers home. (The film is available on a region 2, unsubtitled French DVD.)

Menaces was the last film I saw at this year’s festival, and now I look forward to being able to report in tandem with David at next year’s!

Once more we thank the Ritrovato team (especially Marcella Natale), led by Peter von Bagh, Guy Borlée,and Gian Luca Farinelli, for their visionary achievements. They have changed our conception of what a film festival can be, and they have led us to a deeper and wider appreciation of the glories of cinema.

[July 19: Thanks to Antti Alanen for pointing out that Saul and Jonathan Turell’s name has only one r. It’s spelled indiscriminately all over the internet with one r or two, so thanks also to Brian Carmody of Criterion for confirming that Turell is correct.]

[July 29: Guy Borlée has kindly sent me links for some of the festival events that have gone online at Vimeo since I posted this entry. There’s a set of all the lectures given during the week, including the Peter Becker and Jonathan Turell presentation on the Criterion Collection that I describe above (direct link to the Criterion session here). I mentioned Kevin Brownlow’s introduction to The Iron Mask, but he did a whole presentation on Allan Dwan as well. You can also watch the DVD awards ceremony.]

Scoping things out: A new video lecture

A Star Is Born (1954).

DB here:

Cripes! It’s video-lecture fever!

Well, maybe that’s an exaggeration. Still, we do have something new for you.

A video analysis of constructive editing showed up last fall, and a rather long one called “How Motion Pictures Became the Movies” was posted earlier this year. Now comes one on the aesthetics of early CinemaScope in the US.

It’s a new version of a talk now retired from the lecture circuit and snugly cached on the web. I’m hoping both viewers and filmmakers will be interested in this, particularly in its analyses of staging and composition. The piece makes a more general argument about how new technologies offer both advantages and constraints.

“CinemaScope: The Modern Miracle You See without Glasses!” runs about fifty minutes. It’s our first one in HD, so it looks pretty nice on many displays. It could be shown in classes, and I’d be happy if teachers wanted to use it. As with our earlier entries, it’s also available on Vimeo here, where you can leave feedback if you want.

I’m also providing the chapter on Scope from Poetics of Cinema. Think of the lecture as the DVD and the chapter as the accompanying booklet. You can go to the essay if you want to dig deeper into the subject, see other examples of what I’m talking about, or learn the sources for my arguments.

By the way, if you’re interested in the art and craft of widescreen cinema, I’ve posted a web essay on Hong Kong anamorphic here.

As usual, I’m very grateful to my creative tech wranglers Erik Gunneson, who produced the video, and Peter Sengstock. Thanks as well to our web tsarina Meg Hamel.

I’ll have to suspend production of these video lectures for a while, but Kristin and I are hoping to float another novelty soon, perhaps in the next couple of months.

Thanks for everyone who has supported our work through Tweeting, Facebooking, linking, or just telling their friends.

Wild River (1960). From 35mm frame.

Sometimes two shots . . .

The Mormon’s Victim (1911).

DB here:

. . . just knock you out.

Last summer during a trip to the Royal Film Archive of Belgium I came across a single camera setup that bloomed like a flower in an almost casual way. This entry is in the same spirit, but there’s nothing casual about this cut. I spotted it during my current visit to the Danish Film Archive in Copenhagen.

Nina Gram is engaged to Sven Berg, best friend of Nina’s brother Olaf. But Andrew Larsson, a Mormon, fascinates Nina with his courtliness and his gripping sermons. One night, during a visit to her family’s home, Larsson gets Nina alone while Sven, Olaf, and others are playing cards in another room. She’s starting to succumb to Larsson’s charm offensive (though we think he has offensive charm).

As The Mormon’s Victim (Mormonens Offer, 1911; Nordisk Films, directed by August Blom) develops, Larsson will induce Nina to flee to Utah with him, where he’ll keep her prisoner. Sven and Olaf will track them down by train, ship, and auto, the entire flight and pursuit joined through crosscutting reminiscent of Griffith. The Mormon’s Victim has several memorable shots, including some striking ones taken from a car. But in particular there’s this cut. The two shots surmount today’s entry.

A full shot shows Larsson and Nina in the parlor. Earlier in the scene Sven has left the card game in the distant room to check on what his fiancée is up to. He comes forward hesitantly; this is partly to express his vague worries about Larsson, but it’s also Blom’s way of making sure we know it’s Sven in the rear of the tableau. When Sven returns to the game, he settles in directly behind Nina and Larsson, so that he becomes the most visible figure at the card game.

When Larsson entices Nina away from the piano, they place themselves on the settee in the foreground. And in my first image up top, we can see solid, oblivious Sven right behind them. A blow-up of that area of the shot is on the right.

Then Blom cuts directly in. The axial cut was the most frequent sort of editing found within scenes at this period, and Blom’s cut is more or less along the camera axis, though displaced a bit to the right. The result is a medium two-shot of Larsson staring almost hypnotically at Nina and her responding with rising passion.

You see where I’m going with this. There’s actually a third person in the shot. Sven is still sitting behind them, but now even more tightly sandwiched between the faces–a tiny figure but fully discernible in the 35mm print. On the right I enlarge that portion of the image for you. Dead center, Sven’s tiny head floats between their profiles like a bubble from Nina’s lips or a rose between her teeth.

You see where I’m going with this. There’s actually a third person in the shot. Sven is still sitting behind them, but now even more tightly sandwiched between the faces–a tiny figure but fully discernible in the 35mm print. On the right I enlarge that portion of the image for you. Dead center, Sven’s tiny head floats between their profiles like a bubble from Nina’s lips or a rose between her teeth.

This is a remarkable shot. Since Nina eventually turns away and refuses Larsson’s kiss, we’re tempted to say that the shot creates a visual metaphor, suggesting that Sven “comes between” them. Fair enough, especially since the Danes have the same figure of speech (at komme i mellem). But I’d also want to signal how this possibility of thinly-sliced depth fits smoothly into the tableau style I’ve discussed many times on this blog and in my recently posted video lecture. It relies on hyper-precise staging in depth, accentuated by the axial cut (always a cut that accentuates depth).

It’s all the more remarkable because in those days, the camera viewfinder was mounted alongside the lens. We’re so used to reflex viewing–that is, seeing exactly what the lens of our camera or phone is framing–that we tend to forget that until the 1960s, in most cases a cinematographer had to compose the shot allowing for the parallax difference between the viewfinder and the lens. True, in most tableau shots the camera is far enough back to give some leeway for background planes, and some cameras could swivel (“toe in”) the viewfinder inward as the framing got closer. But this scene remains an extraordinary piece of filmmaking. The cinematographer Axel Graatkjaer, only twenty-six when he shot this film, deserves credit for pulling off a rare stunt.

The Mormon’s Victim is yet another example of the great variety and boldness of the cinema of the 1910s. Had I known it, I would probably have squeezed it into my video lecture, “How Motion Pictures Became the Movies.” Maybe I can work it into the followups I plan to post later this year. In the meantime, take this as another instance of why we should thank film archives for preserving fairly obscure films that have a lot to teach us about what talented creators have done with our favorite medium.

Ron Mottram surveys the local films of this period in his indispensable The Danish Cinema before Dreyer. For more on the tableau style, see the lecture I just mentioned, along with the blog entries in the category. I have more on Danish films and the tableau tradition here, and I discuss that tradition as a background to Dreyer in an essay on the Danish Film Institute’s Dreyer site.

Thanks to Thomas Christensen and Mikael Braae of the archive for all their help. I have devoted other entries to their archive and Danish film culture, but this might be the most relevant today.

Mikael Braae surveys a recently received collection of over 400 35mm film prints. He’s in the process of sorting and examining them. There are still big 35mm collections out there!

What next? A video lecture, I suppose. Well, actually, yeah….

DB here:

We’ve said several times that this website is an ongoing experiment. We started just by posting my CV and essays supplementing my books. Then came blogs. We quickly added illustrations to our entries, mostly frame enlargements and grabs. Eventually, video crept in. In 2011 we ran Tim Smith’s dissection of eye-scanning in There Will Be Blood. Last year, in coordination with our new edition of Film Art: An Introduction, we added online clips-plus-commentary (an example is on Criterion’s YouTube channel), and near the end of the year Erik Gunneson and I mounted a video essay on techniques of constructive editing.

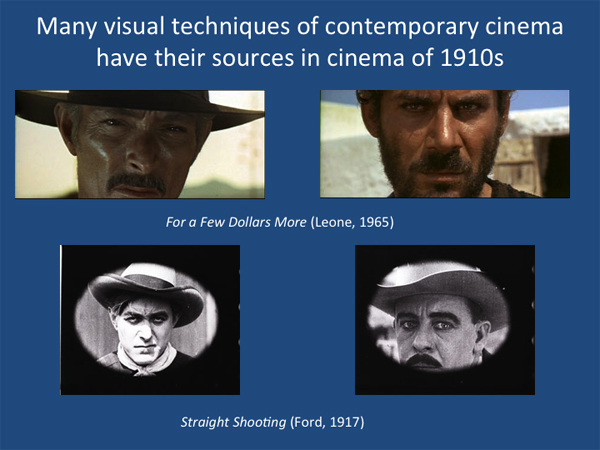

Today something new has been added. I’ve decided to retire some of the lectures I take on the road, and I’ll put them up as video lectures. They’re sort of Net substitutes for my show-and-tells about aspects of film that interest me. The first is called “How Motion Pictures Became the Movies,” and it’s devoted to what is for me the crucial period 1908-1920. It quickly surveys what was going on in cinema over those years before zeroing in on the key stylistic developments we’ve often written about here: the emergence of continuity editing and the brief but brilliant exploration of tableau staging.

The lecture isn’t a record of me pacing around talking. Rather, it’s a PowerPoint presentation that runs as a video, with my scratchy voice-over. I didn’t write a text, but rather talked it through as if I were presenting it live. It nakedly exposes my mannerisms and bad habits, but I hope they don’t get in the way of your enjoyment.

“How Motion Pictures Became the Movies” is designed for general audiences. I’ve built in comments for specialists too, in particular, some indications of different research approaches to understanding this period of change.

The talk runs just under 70 minutes, and it’s suitable for use in classes if people are inclined. I think it might be helpful in surveys of film history, courses on silent cinema, and courses on film analysis. If a teacher wants to break it into two parts, there’s a natural stopping point around the 35-minute mark.

Some slides have several images laid out comic-strip fashion, so the presentation plays best on a midsize display, like a desktop or biggish laptop. A couple of tests suggest that it looks okay projected for a group, but the instructor planning to screen it for a class should experiment first.

I plan to put up other lectures in a similar format, with HD capabilities. Next up is probably a talk about the aesthetics of early CinemaScope. I’d then like to spin off this current one and offer three 30-minute ones that go into more depth on developments in the 1910s.

The video is available at the bottom of this entry, but it’s also available on this page. There I provide a bibliography of the sources I mention in the course of the talk, as well as links to relevant blogs and essays elsewhere on the site.

If you find this interesting or worthwhile, please let your friends know about it. I don’t do Twitter or Facebook, but Kristin participates in the latter, and we can monitor tweets. Thanks to Erik for his dedication to this most recent task, and to all our readers for their support over the years.