Archive for the 'Film technique: Cinematography' Category

Tony and Theo

Man on Fire (Tony Scott, 2004); The Suspended Step of the Stork (Theo Angelopoulos, 1991).

DB here:

In January of 2012, while shooting The Other Sea, Theo Angelopoulos was struck by a motorcyclist and died soon afterward. In August, Tony Scott committed suicide by jumping off Los Angeles’ Vincent Thomas Bridge.

Both men mattered to cinema. But which cinema?

From 1970 onward, Angelopoulos produced solemn films about Greek history, world war, emigration, and the collapse of struggles for political change. His hallmark was the extended—some said excruciating—long take. He presented his work as that of a thoughtful and passionate intellectual, a witness to history (or as he sometimes said, History) who was telling us hard, melancholy truths. His work received little mainstream distribution outside Europe and Japan, and some of his best films weren’t circulated nontheatrically or on video. Severe and abrasive, he alienated powerful members of film culture and was reported to have responded sourly when he did not win Cannes’ top prize.

By contrast, after Top Gun (1986), Tony Scott came to be the prototype of the ADD Hollywood director, a master of the blockbuster action picture. He gleefully marshaled visceral technique to jolt the eye and hammer the ear. His movies were unabashed booty calls, spotlighting female pulchritude in a tone of laddish camaraderie in an all-male milieu (sports, the military, the workplace). Not lacking intelligence, he avoided the sweeping pronouncements that made Angelopoulos look pretentious, but his early partnering with Simpson and Bruckheimer stamped him as raucously vulgar. He even dated Brigitte Nielsen.

Extremes meet

Déja vu (2008); Eternity and a Day (1995).

The statuesque versus the kinetic, the monumental versus the ephemeral, ponderousness versus cheap flash: To all appearances, these men lived in different cinematic worlds. Their careers were oddly counterpointed too. Angelopoulos, a festival darling in the 1970s and 1980s, became more unfashionable. By the time of his last release, The Dust of Time (2009), some critics were openly scornful. Scott faced gibes from the start but won some critical respect in the 2000s. After his death, critics were calling him a master. To many, Angelopoulos’s stubborn allegiance to 1970s modernism looked old hat, while Scott’s bodaciousness and eye candy seemed to have finally seduced audiences and critics alike.

I confess that both give me qualms. When Angelopoulos strains for significance, as he does at many moments throughout his oeuvre and almost constantly in The Dust of Time, he arouses all my impatience with pretentious Eurocinema. When Scott builds a scene out of Fuck-you-motherfucker dialogue and lingering views of pole dancers he reminds me of just how low contemporary American cinema can sink. And the style of each one can become predictable–an angled shot down a street portends a pan in Angelopoulos, while once somebody sits down in a Scott movie the camera is likely to start to twirl.

Despite these misgivings, I find that I can admire and enjoy both men’s films quite a lot. Their most venturesome work offers us powerful experiences, and they can teach us things about cinema—not least, how creative filmmakers can rework the medium and its historical traditions.

And their worlds overlap at least a little. Both men treat cinema as an art of scale. To see Man on Fire (2004) or Alexander the Great (1981) on home video, no matter how big your monitor, is to shrink the films fatally. Correspondingly both men relied on spectacle, stuffing the screen with sweeping, startling effects. True, Scott’s spectacle is maximalist, while Angelopoulos’s is austere. Yet once you’ve calibrated your bandwidth, the train that rumbles through the migrant camp in The Weeping Meadow (2004) becomes no less rattling than the rogue locomotive in Unstoppable (2010). “Go big or go home” might be each man’s motto.

Both play games with narrative as well. As early as The Hunger (1983) Scott’s incessant crosscutting uses the soundtrack of one line of action to comment on another. The time looping of Domino (2005) and Déja Vu (2008) creates flashbacks, replays, revised outcomes, and jumping viewpoints. More sedately, Angelopoulos perfected the time-shifting long take. The camera movements of The Traveling Players (1975) glide among different eras. From scene to scene, Angelopoulos will provide few marks of tense. Scene B may follow A, or precede it by several years, and no Hollywoodish superimposed title will help us out. It may be several minutes before we realize that decades have passed.

Yet the time-scrambling both directors enjoy isn’t wholly at the service of drama. Storytelling takes on a curiously subsidiary role in their work. Neither filmmaker, it seems to me, is centrally interested in probing what many of us take to be the core of narrative—character psychology. This isn’t to say there aren’t poignant moments and glimpses of inner lives. But each director also leaps beyond them.

I think in fact that Tony and Theo explore what happens when narrative slips away, when cinematic textures and patterning are allowed to override drama—to inflate it, deflate it, thrust it to one side, take it as a pretext for something more tangibly enthralling. Both filmmakers seek to shape our perception and emotion, letting the fluctuations of images and sounds engender a kind of mesmeric attention in themselves.

They accomplish this within two different traditions, that of modern Hollywood and that of “art cinema.” Yet they share a commitment to going beyond the given: Each director pushes his tradition to a limit.

Pulp fictions

Déja vu (2008).

Scott’s tradition is, most broadly, Hollywood narrative cinema, and up to a point he plays along. The plots are propelled by goal-directed characters who clash with others, and the results are contests (Top Gun, Days of Thunder, 1990), investigations (Beverly Hills Cop II, 1987; Man on Fire, Deja Vu), pursuits and conspiracies (Revenge, 1990; The Last Boy Scout, 1991; True Romance, 1993; The Fan, 1996; Enemy of the State, 1998; Spy Game, 2001; Domino), and ticking-clock suspense situations (Crimson Tide, 1995; The Taking of Pelham 123, 2009; Unstoppable).

At the center there usually stands one man, or a duo, who must undergo a test of courage and resourcefulness. In The Fan, an example of what Kristin has called the parallel-protagonist movie, a normal guy finds himself pursued by an obsessed admirer. A woman might serve as a gutsy partner, as in True Romance, or the object of the quest (Revenge, Spy Game), or the reward for success (The Last Boy Scout, Unstoppable). Only Domino has a female protagonist who survives through being as abrasive, dirty-minded, and foul-mouthed as her male partners and adversaries. Yet by her own admission, she has daddy issues and a longing to return to cozy wealth.

At bottom, then, Scott worked with straightforward pulp stories, and for about a decade he played them in the proper spirit. But with Enemy of the State (1998) he began to use the slipperier narrational strategies spreading through Hollywood of his time. Like Tarantino, who supplied the script of True Romance, Scott became willing—inspired, he suggests, by rock’n’roll and the films of Nicholas Roeg—to go a little wild.

His scripts started playing with what we usually call point of view. Some films become markedly, not to say traumatically, subjective. Spy Game splits the protagonist figure into two and gives us each one’s standpoint on the action. The Fan, from Peter Abraham’s fine novel, tracks a man’s obsession as it turns deadly. Man on Fire plunges into John Creasy’s mental world as he distills pain, guilt, piety, and alcoholism into a merciless sadism.

By the time we get to Domino, story presentation is pitilessly disjunctive. The main action is bracketed by a conventional frame showing the heroine telling her story to a police officer. A good thing, too; we couldn’t follow the action without her commentary. The tale fractures into quickfire AV displays, with pauses, backing-and-filling, alternative outcomes, and even written titles, as if we were getting the most juice-jangled PowerPoint talk in history.

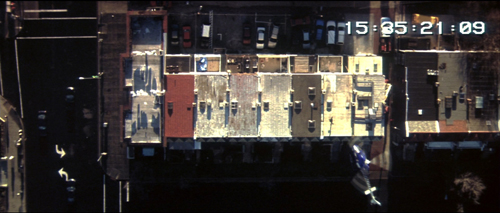

Another multiplication of perspective takes place via spy games. Most directors situate modern surveillance techniques within their story world; Paul Greengrass seems happiest shooting people bent over workstations. When your average director gives you a swooping helicopter shot, you don’t take it as the POV of a sinister government agency or a sensationalistic TV livecam. In Scott’s late films you’re likely to. He realized that all today’s security cameras, cellphones, and hostile eyes in the sky can do two useful things. They can chop story space and time into teasing fragments, and they can refresh the shot’s visual texture.

For quite some time Hollywood movies have used television for exposition. Characters tap into the flow of story events via TV broadcasts, and sometimes, as in The Siege (1998), the film simply cuts in news clips presented directly to us, without any mediating character. Passages like these, a contemporary equivalent of the newspaper headlines and radio broadcasts of classic studio cinema, usually smooth out the plot, linking things concisely.

But Scott takes pleasure in playing up the disparities among the footage, cutting from “direct” presentation of material to mediated images and sounds. In the conspiracy films, the video images seem to be coming from a vast image bank or database that the film is sampling on the fly. Moreover, the constant interruption of one shot by another, seen on computer or news broadcast or spycam, creates a nervous visual narration. In effect, Scott imports the mixed-format collages of Stone’s JFK (1991) into the action film (with more skill than Stone summoned up for Natural Born Killers of 1994 and U-Turn of 1997).

At the level of presentation, though, a narrower tradition shapes Scott’s style. In interviews and director commentaries he ceaselessly reminds us that he started out as a painter, and he has, I think, brought a fresh pictorial intelligence to the action film.

Too much is not enough

Days of Thunder (1990).

Like Michael Mann, Scott seems to have felt the need to give the action picture a dose of self-conscious artistry. The problem was the competition. The gold standard of the genre emerged in 1988 with the poised, tightly-woven classicism of John McTiernan’s Die Hard. How was an ambitious director to match that? Most directors were embracing variants of a style I’ve dubbed “intensified continuity”—fast cutting, simple staging, polar extremes of lens lengths, almost constant camera movement. The efficient but routine Richard Donner and Renny Harlin worked along these lines, while Michael Bay represented the style in almost pristine form. But what if a director who had trained as a painter at the Royal College of Art could take intensified continuity into new territory?

So yes, go along with the trend toward fast cutting; but make it even faster. In an era in the average shot in the average film runs between 3 and 5 seconds, why not make them 2 seconds? Or less? This was Scott’s choice from The Fan (1996) on. He seldom repeats a setup, largely because he has so many cameras stationed on the perimeter of the scene. Man on Fire contains at least 4100 shots, Domino over 5000, but perhaps we will never know just how many. Long passages are built out of multiple exposures, superimpositions, stop-and-go motion, and color shifts within a “shot.” The cut ceases to be a firm boundary as layers float up and slip away.

At times Scott, like Vertov in Man with a Movie Camera and Pat O’Neill in Power and Water, simply abandons the concept of a discrete shot, letting images seep through his frame.

And yes, move the camera; but move it in arabesques quite different from McTiernan’s unfussy following shots and tense track-ins. In particular, take the swirling camera as a given but then pivot your subject a bit as well. Cutting from one rotation to another can yield a little ballet of sculptural solidity, with barriers gliding by in the foreground and bursts of tonal values throughout. Here’s an example from Unstoppable.

In the 1980s and early 1990s films, Scott mixed haze and sharpness. Some scenes would be shot in metallic or earth tones and swathed in those smoky layers brother Ridley had popularized in Blade Runner. Other scenes would boast silhouettes, crisp edges, and blocks of bright color. Consider these images from Revenge, The Last Boy Scout (2 frames) and True Romance.

All framings–long-shot, medium-shot, close-up–tend to be covered by several cameras with very long lenses, which flatten and abstract the image. Later, having discovered the power of cross-processing reversal stock, Scott mostly gave up haze for what he called hyperrealism: high contrasts, along with Hockneyish color ripeness and thick but still transparent shadow regions.

Scott adds to the canons of intensified continuity the punch of the axial cut, that shot change that yanks figures toward or away from us (an effect that his last films mimicked by snap-zooms). Combined with long lenses set at various distances, this option creates a sense of constantly losing and refinding the point of the shot. As Connie swivels during a later stretch of the Unstoppable scene, the axial cut with different backgrounds pins her against varied blocks of color.

Critics complained that Scott’s style reminded them of MTV videos and commercials, a great number of which the Scott brothers produced. But there’s nothing inherently wrong with filmmakers drawing inspiration from advertising (as painters like Warhol and Stuart Davis did) or from video clips (as Wong Kar-wai seems to have done). What matters is what you do with your sources. It seems clear that Scott subjected these techniques to a new pressure, using them to thrust current norms to new extremes.

Intensified continuity, as I argued in The Way Hollywood Tells It, offers a mannerist version of classic continuity. If that’s accurate, then we might say that Scott provides a Rococo variant of intensified continuity itself. Michael Mann, another pictorialist, is more of a purist, seeking a sober gravity, while Scott doodles and scrawls across the surface of his scenes. Not only does he interpose reflections, rain, dust, and other particles between his subjects and us, but he reiterates lines of dialogue via supered titles.

Mann lets us soak up his images, but Scott tosses out one gorgeous composition after another in bewildering profusion. In the accelerated late films, they barely have time to register. The film seems to whisk away under our eyes. Shots lack an organic arc; they’re lopped off. Partial impressions pile up, defeating our urge to dwell on a composition. Sometimes you can’t trust your eyes. During the kidnap scene of Man on Fire, a thug prepares to shoot back at Creasy as a burst of flame is reflected in his car.

Problem is, nothing has caught fire in the scene; for once, no explosions. It’s purely a crazy jolt, literalizing the idea of a “firefight” without any realistic motivation.

These techniques are motivated to some degree by story demands: the need to suggest a mental state, to portray a heroic posture, or to amp up a fight or chase. But Scott’s visual and auditory handling exceeds the demands of clear storytelling. He wraps the most perfunctory dialogue scene in a dazzling embroidery that arrests attention in its own right. Mere decoration? I’d agree. Still, decorative art isn’t an unworthy calling, and decoration pursued with conviction and inventiveness demands our notice.

And this decoration isn’t dainty. Domino, Unstoppable, and the second half of Man on Fire have a grunge dimension, with shots that make our world look at once harsh and dazzling. Scott could be our Sam Fuller (complete with cigar), and Domino could be his Naked Kiss. Fuller might echo Scott’s gaffer, who said of Domino: It isn’t pretty, but it is beautiful.

Threnody

Ulysses’ Gaze (1995).

From The Birth of a Nation to Lincoln, American studio cinema tends to show grand historical events intertwining with the private dramas of great leaders or common folk. But there were other options. Eisenstein’s first three films—Strike, Battleship Potemkin, and October—floated the possibility of the “mass protagonist.” In these films, history is made by groups, and individuals are given largely symbolic roles. During the politicized 1960s, this model was taken up by filmmakers on the left.

The filmmaker who explored this option most fully was the Hungarian Miklós Jancsó. Although his films seem to be little-known today, he was a major force in reviving the idea of presenting history through group dynamics. Individuals play a role in The Round-Up (1965), Silence and Cry (1968), and The Confrontation (aka Bright Winds, 1969), but they are usually bereft of personal psychology. These figures are defined by their roles in a struggle—a civil war, a revolution, a clash with a domineering regime—and they are often pawns in a game of shifting power.

The Red and the White (1967), available on DVD, is a good example. This saga of the Russian Civil War that followed the 1917 revolution takes us through skirmishes between clashing armies, the tactics pursued by a squadron of Hungarian volunteers, and episodes in a Red Cross station. Individuals come to the fore briefly but are likely to vanish from later scenes, or simply die on the spot. One young Hungarian threads his way through the action, but he can hardly be said to be a point-of-view character, and we learn nothing of his background or motives. A great deal of the film is taken up with rituals of questioning prisoners, torturing and shooting captives, and ravaging innocents caught in the crossfire. At the climax, a tattered Red unit marches defiantly toward a superior White force, the entire confrontation played out in a stupendous landscape.

The Red and the White could defend itself from charges of formalism through its affinity with Soviet-style war dramas, but as Jancsó went on to examine episodes in Hungarian history, he soon gave up realism. He staged historical events in symbolic forms, on a bare plain or as obscure rituals in festivals rippling with music and dance. Examples are Agnus Dei (1972), and Red Psalm (1969; available on DVD). These films relied on endlessly tracking, craning, and zooming; the camera floats, and space stretches and squashes. The result was long-take extravaganzas. The Red and the White has fewer than two hundred shots; The Confrontation (1969) only thirty-five; Sirocco (1969) and Elektra, My Love (1974; on DVD) fewer than a dozen.

It seems to me that after Angelopoulos’s first film, he picked up and expanded Jancsó’s idea of investigating a nation’s history through mass dynamics and stripped-down spectacle. He proceeded more or less chronologically through modern Greek history. Days of ‘36 (1972) examines the dictatorial rule of General Metaxas (1937-1941) while The Traveling Players of 1975 covers the Nazi occupation and postwar civil strife. The Hunters (1977) revives the years from the civil war (1944-1949) to the mid-1960s through an arresting narrative device: present-day hunters find the corpse of a civil war partisan, as fresh as if killed yesterday. Alexander the Great (1980) doubles back to a period from the turn of the century until the 1930s, showing a bandit taking power over a remote village.

This tetralogy did pick out individuals, but it made them symbols of larger forces, often through names drawn from history or mythology. The travelling players are named Electra, Orestes, and the like; Alexander the bandit is a brutish version of his legendary namesake. Nevertheless, Angelopoulos’ presentation did little to acquaint us with them from the inside. He drew on none of Scott’s subjective tricks to convey instant impressions or fragments of memory; even his quasi-subjective flashbacks were likely to include the protagonist as he is today in the scene from the past.

Popular filmmaking depends on our accessing characters’ thoughts and feelings, but Angelopoulos largely gave that up. He made his plots depend on large-scale political forces. Sometimes, as in Days of ’36 and The Hunters, we are taken behind the scenes and shown the machinations of power, but usually history unfolds through impersonal forces—often outside the frame. When the apparatus of power is made visible, it’s through visions of police, soldiers, or other authorities. And those are often presented as rigid and impersonal.

Below, in Ulysses’ Gaze, a candlelight march is confronted by row upon row of police. The calm, mechanical way the officers fill up the middle ground makes the impending conflict quite suspenseful. When you think the composition, and the confrontation, have exhausted the shot’s duration and space, a crowd of citizens appears in the foreground to bear witness. All three groups are made into homogeneous blocks through the distant framing and the consistency of texture (flickering candles, uniforms, umbrellas).

The drama comes when our characters are forced to respond to the forces of oppression. They flee, they hide, or they’re captured and sent to prison or execution or exile. It’s an inglorious version of history, filtered through a Brechtian belief that distancing us from charged situations, presenting emotions dryly rather than melodramatically, can bring lucidity and a grasp of macro-dynamics. But Angelopoulos also traced his the origins of his oblique, sometimes opaque style to the pressures of censorship. Under the Greek junta, it was impossible to speak about history directly.

So I sought a secret language. Tacit understanding of the story. The temps morts in plotting a conspiracy. The unsaid. Elliptical discourse as an aesthetic principle. A film in which everything that is important takes place outside the frame.

Even after censorship ceased, Angelopoulos continued in this taciturn vein, making his films thoroughly decentered and dedramatized.

Yet in the 1980s, he tried to offer audiences more. He began to put distinct and individualized characters at the center of his films, and he achieved his survey of political change by sending them on modern Odysseys. In Voyage to Cythera (1983) a film director is conceiving a new project, and he visualizes the story of an elderly Communist let out of prison and returning to his village. In The Beekeeper (1985), a schoolteacher abandons his family and embarks on a trip across a bleak modern Greece. Landscape in the Mist (1988) follows two children convinced that their emigrant father is waiting for them just across the border. In The Suspended Step of the Stork (1991) a television journalist tracks down a prominent politician who seems to be hiding in a refugee village.

Two 1990s films plumb the characters’ pasts in more detail. Ulysses’ Gaze (1995) follows an archivist (called simply A) searching for a lost film and his own family history in the Balkans. In Eternity and a Day (1998), a poet in the last days of his life reflects on his life while accompanying a boy trying to return to Albania.

In the 2000s Angelopoulos began again thinking on an epic scale. Trilogy: The Weeping Meadow (2004) announced itself as the first installment in nothing less than a history of the twentieth century told through the experience of a single family. Concentrating on a refugee couple—one Russian, one Greek—it sets their fugitive romance against the events of World War I, the rise of Fascism, and the Greek Civil War, while also hinting at parallels to Attic tragedy. The second installment, The Dust of Time (2009) runs parallel to Voyage to Cythera and Ulysses’ Gaze in centering on a filmmaker, but he becomes less central to the plot than his father, his mother, and his mother’s lover–all victims of 1950s Soviet Communism who survive to see the fall of the Berlin wall.

Over these years, Angelopoulos collaborated with the Italian screenwriter Tonino Guerra (who died about two months after the director). Guerra, who worked with Antonioni, Fellini, the Tavianis, and many other directors, may have helped turn Angelopoulos toward less forbidding storytelling. The more vividly drawn protagonists of the late work were often played by well-established actors (Mastrioanni, Moreau, Ganz, Keitel, Dafoe, Piccoli), and two of the films center on children, one common way to kindle emotion. Eleni Karaindrou’s scores, full of threnodies rising up from massed strings, by also gave the films after Cythera a plangent warmth reminiscent of doleful musical pieces by Henryk Górecki and Arvo Pärt.

Still, these late films are only comparatively more accessible. Their stories come across as downbeat, episodic, relatively empty of conventional drama, full of “dead time” and unmarked time shifts, and deeply somber. Which is to say that they belong to the broader tradition of postwar European art cinema, its norms given fresh realization through echoes of Greek mythology and a signature style of exceptional rigor.

Stasis and sublimity

Alexander the Great (1981).

At the level of technique Angelopoulos again emerges as a synthesizer. An admirer of Mizoguchi and Antonioni, and again probably influenced by Jancsó, he became identified with the long take. From The Traveling Players on, scenes are presented in very few shots, often only a single one. Three films of the tetralogy contain between 125 and 150 shots, while The Hunters makes do with 49. And most of the films are very long (two nearly four hours), so the average shot length runs from 72 seconds (Days of ’36) to 206 seconds (The Hunters). As the later films became more accessible, the editing paced quickened only a little: no film has more than a hundred shots, and in all the average shot runs between fifty seconds and two minutes. Add together all the shots in Angelopoulos’ thirteen features and you have less than a third of the shots in, say, Scott’s Enemy of the State.

Most long-take filmmakers scale their framings to human activity; think of Ophuls and Renoir, capturing gestures and reactions as time flows through the image. But Angelopoulos combined the long take with the long shot, putting landscape at the center of his work. The stunning shot I’ve excerpted from The Red and the White above isn’t wholly typical of Jancsó’s films, which tend to have many close framings and to save vast views for climactic moments. By contrast, Angelopoulos makes very distant shots his default mode for exteriors, even for moments of high drama: a conversation in The Hunters, a death in Alexander the Great.

There are very few conventional close-ups in his films, and mid-shots are often forced on him by fully-built interiors, either locations or sets, as in the frame below from The Weeping Meadow. Even then, the camera often keeps its distance, subordinating characters to impersonal architecture and making their encounters seem fragile (The Suspended Step of the Stork).

Sometimes the tableau that results has considerable depth, as with groups gathered in interiors (The Hunters, below). More pointedly, a horrifying scene in Landscape in the Mist almost cruelly forces our eye back into the distance. In each shot, the most important action is furthest from the camera.

At other moments the long shot yields what I’ve called planimetric images. There’s still a fair amount of depth, but the shot is framed perpendicular to a back plane and figures are spread out in strips or layers. Some images earlier in today’s entry afford examples, particularly the developing street confrontation in Ulysses’ Gaze. The Weeping Meadow shows that this principle can be applied to a raft and rowboats too.

Like Scott, Angelopoulos relies on very long lenses, but he holds the shot so that the flattening effect of the lens creates a gradually changing pattern.

Both depth framings and planimetric ones were exploited by European filmmakers of the late 1960s and early 1970s, but Angelopoulos focused rigorously on them and joined them with consistently distant camera positions. As the dramaturgy downplays individual psychology, the shot scale makes individuals figures in a landscape. The result is often a rhythmic organization of the frame, a pattern of symmetries and abstract geometries (Traveling Players, The Dust of Time).

In the later films, moments of personal drama are played out in no less opaque distant shots. In Voyage to Cythera, the exile’s wife goes to their old cottage and coaxes him out. They must be exchanging a look of understanding, but only on the big screen is it visible.

Such fixed shots are riveting enough, but how can the filmmaker dynamize them and prepare for them? The answer for Angelopoulos was keeping the frame mobile. He refuses the giddy sweep and beguiling tempo of Jancsó. Angelopoulos is severe. Like Scott, he will use the zoom, but his enlargements or de-enlargements are stately, not staccato. (Again, that Red and the White shot may have been an early model for him.) In all, his mobile framings are as austere as the color palettes (earth and metal tones) and the lighting (subdued, often chiaroscuro, with usually a drab sky).

His camera pans with passing characters, sometimes letting them come close enough for us to identify them or catch an expression; a prolonged traveling shot follows Spyros’ wife in the scene above as she approaches the fence. But the very plainness of this technique can sharpen our expectations. As often in postwar European film, the extended, dialogue-free walk creates its own arc of interest. We rarely know where a character is headed on that walk, or what they see that makes them approach. In a way this technique recalls the thriller or horror film: show the reaction and pan to the cause of it. But with Angelopoulos that cause will tend to be something stupefying in scale, a revelation of a side of the world we haven’t suspected, perhaps a realm closer to surrealism (The Suspended Step of the Stork; Trilogy: The Weeping Meadow).

Hallucinatory images like these, presented with a calm gravity, suggest that the forces of history, like Goya’s dreams of reason, bring forth monsters—not raging and tumultuous ones, but ones displaying deathly, disturbing stillness. The emotional shock of the characters communicates itself to us as a pictorial shock, itself achieved by the simplest means. In Eternity and a Day, the protagonist and the boy come upon a refugee camp where the detainees, clinging to the fence, seem suspended in the mist.

The result of all these creative choices is a cinematic pageant, and not only because of its splendid imagery. Like the medieval pageant wagons that rolled scene after scene past a crowd, Angelopoulos’ scenes become a procession of tableaux. They are broken by movements—sometimes slow, sometimes sudden, almost always small. Only he could imagine this shot in Alexander the Great in which a tourist edges out from behind a pillar at the Temple of Poseidon and lifts his finger for silence. His arm arrests our attention without losing the monumental context.

If Tony Scott’s images are hurled out in a mad rush, Angelopoulos gives us time to see the smallest changes. Sometimes these emerge in cramped interiors, guided by aperture staging or a gliding camera. At other moments we must scan a vast space to spot our protagonists. What eighteenth-century thinkers called the Sublime, the fearsome majesty we apprehend in the enormity of the world outside ourselves, as during a storm at sea, has been given a political weight. Not despair, Angelopoulos insists, or even pessimism: rather, a collective melancholy at recognition of a sad destiny.

Like Scott, Angelopoulos pushed to new extremes certain premises of the traditions he chose to work in: Dedramatization, depersonalization, the long take, a reliance on staging that is dense or spacious, deep or planar, and the urge to represent history and contemporary life in a more abstract, majestic way. Heir to Antonioni and Jancsó, he carried their visual ideas to new limits and showed what more they could do. That strategy laid bare his own artifice, to the point that the minute fluctuations of style–no less “cinematic” than Scott’s–fascinate us in their own right.

All I’ve done is to trace some curves and whorls of each filmmaker’s signature, his characteristic principles of handling story and style in relation to the norms of his time. I haven’t tried to launch fine-grained analyses of particular scenes or entire films. Both are necessary, of course. Still, the sort of analysis I’ve outlined seems to me essential to appreciating their work fully.

That work has something broader to teach us about film and film criticism. Too often critics think that their job is to expose a film’s meanings. For most critics, that often entails a Zeitgeist interpretation. The movie is held to reflect the events, popular mood, or wish-fulfillment needs of its time. For academic critics, the hunt for meaning may also entail mapping a set of theoretical concepts onto the film, as with psychoanalytic or postmodernist interpretations.

But filmmakers like Scott and Angelopoulos remind us that we should say, more accurately, that films produce effects, of which meanings are only one type. The film provokes us to have an experience, part of which may be the search for themes and implications, but another part–perhaps the biggest and most basic one–is a guided process of perception, thinking, and emotion.

Of course, meanings matter. Enemy of the State warns us about how surveillance and data-mining can obliterate personal identity. Landscape in the Mist suggests that in the age of migrant labor, disputed boundaries, and ethnic wars, Europe has destroyed childhood. So far, so good; and we should go further. But tracing the dynamics of theme still obliges us to analyze the perceptible force of these films. That, I think, can best be recognized through a study of how the resources of cinema are deployed to give us an experience that isn’t reducible to paraphrasable ideas.

These cinematic resources, flaunted without apology from moment to moment, are the fabric of the movie. In fact, both men pretty relentlessly drain their scenes of thematic meaning. In Enemy of the State, Scott piles up so many surveillance and counter-surveillance stratagems that the anti-technology message seems just a pretext to multiply images, switch points of view, and futz up our own information-processing. In Ulysses’ Gaze, the shot of a dismantled Lenin statue floating down the river on a barge makes its “statement” immediately, but Angelopoulos won’t let it go. He follows its progress, shows people on the river banks kneeling and praying to it, and accompanies the whole sequence with Karaindrou’s surprisingly lilting music. The Symbol of Dead Communism has been drained of its portent and has become a curiously lyrical audio-visual display. These men go so far that they come out the other side.

Accordingly, both have been called heavy-handed: one is shallow, the other hollow. Granted, many viewers find art works that depend on kinetic impact or slow accumulation unsubtle. Yet sometimes force, bursting out or released in minute doses, is welcome. The Rite of Spring and Threnody for the Victims of Hiroshima both strike with a physical impact. Here the odd couple Tony and Theo find one more affinity: They suggest that subtlety in the arts may be overrated.

Information about the posse Tony Scott ran with in his early days can be found in Charles Fleming, High Concept: Don Simpson and the Hollywood Culture of Excess (Main Street, 1999). The gaffer discussing Domino is Bruce McCleery, and I’ve paraphrased his original comment: “It’s definitely not pretty, but on some level it can be truly beautiful.” See Pauline Rogers, “Lady Killer,” ICG Magazine (October 2005), 35.

Scott’s death has provoked a lot of good writing on the Net. See for example Manohla Dargis, “A Director who Excelled in Excess”; Jim Emerson, “Films on fire”; Christoph Huber and Mark Peranson, “World Out of Order: Tony Scott’s Vertigo”; Ignatiy Vishnevetsky’s “Smearing the Senses: Tony Scott, Action Painter”; and, for discussions of individual sequences, see “Tony Scott, a Moving Target,” the remarkable round-robin hosted by MUBI and Daniel Kasman and Gina Telaroli. Reliably, David Hudson has compiled web critics’ reactions at Fandor.

Jancsó’s films deserve closer scrutiny than they’ve received. My Narration in the Fiction Film includes an analysis of The Confrontation (not, so far as I know, available on DVD).

Perversely, having claimed that these directors’ images suffer when reduced, I’ve given you postage-stamp illustrations, and for this I apologize. Take them as waving you toward the need to see the films at full stretch. As for their quality, I’ve drawn as many illustrations from 35mm prints as I had available, but I’ve been obliged as well to rely on DVD copies, and those yield uneven results in the Angelopoulos frames. For discussions of the versions of his films available on DVD, see the Criterion Forum and Mubi.

The critical and academic literature on Angelopoulos is decently varied. Dan Fainaru’s Theo Angelopoulos: Interviews is a very good place to start. The best overview of most of the oeuvre is Andrew Horton’s Films of Theo Angelopoulos, which provides essential historical and biographical background. See also Andy’s anthology, The Last Modernist. For Cineaste Andy also wrote a touching reminiscence on the occasion of the director’s death. Catherine Grant has assembled a vast online dossier at Film Studies for Free, and David Hudson has charted immediate web responses here.

The French journal Positif was a loyal supporter of Angelopoulos, publishing articles and informative interviews for decades. My quotation above comes from Angelopoulos’s essay, “In my end is my beginning,” Positif no. 463 (September 1999), 62.

A little discussion of Angelopoulos, in the context of the fortunately short-lived ruckus about eat-your-vegetables cinema, can be found in this entry on our site. Chapter 4 of Figures Traced in Light: On Cinematic Staging is an expanded version of my essay in Andy Horton’s collection, and I’ve borrowed some of its ideas here. I hope to write more about Tony Scott’s work on this website later this year.

Enemy of the State (1998); The Traveling Players (1975).

Sometimes two shots . . .

The Mormon’s Victim (1911).

DB here:

. . . just knock you out.

Last summer during a trip to the Royal Film Archive of Belgium I came across a single camera setup that bloomed like a flower in an almost casual way. This entry is in the same spirit, but there’s nothing casual about this cut. I spotted it during my current visit to the Danish Film Archive in Copenhagen.

Nina Gram is engaged to Sven Berg, best friend of Nina’s brother Olaf. But Andrew Larsson, a Mormon, fascinates Nina with his courtliness and his gripping sermons. One night, during a visit to her family’s home, Larsson gets Nina alone while Sven, Olaf, and others are playing cards in another room. She’s starting to succumb to Larsson’s charm offensive (though we think he has offensive charm).

As The Mormon’s Victim (Mormonens Offer, 1911; Nordisk Films, directed by August Blom) develops, Larsson will induce Nina to flee to Utah with him, where he’ll keep her prisoner. Sven and Olaf will track them down by train, ship, and auto, the entire flight and pursuit joined through crosscutting reminiscent of Griffith. The Mormon’s Victim has several memorable shots, including some striking ones taken from a car. But in particular there’s this cut. The two shots surmount today’s entry.

A full shot shows Larsson and Nina in the parlor. Earlier in the scene Sven has left the card game in the distant room to check on what his fiancée is up to. He comes forward hesitantly; this is partly to express his vague worries about Larsson, but it’s also Blom’s way of making sure we know it’s Sven in the rear of the tableau. When Sven returns to the game, he settles in directly behind Nina and Larsson, so that he becomes the most visible figure at the card game.

When Larsson entices Nina away from the piano, they place themselves on the settee in the foreground. And in my first image up top, we can see solid, oblivious Sven right behind them. A blow-up of that area of the shot is on the right.

Then Blom cuts directly in. The axial cut was the most frequent sort of editing found within scenes at this period, and Blom’s cut is more or less along the camera axis, though displaced a bit to the right. The result is a medium two-shot of Larsson staring almost hypnotically at Nina and her responding with rising passion.

You see where I’m going with this. There’s actually a third person in the shot. Sven is still sitting behind them, but now even more tightly sandwiched between the faces–a tiny figure but fully discernible in the 35mm print. On the right I enlarge that portion of the image for you. Dead center, Sven’s tiny head floats between their profiles like a bubble from Nina’s lips or a rose between her teeth.

You see where I’m going with this. There’s actually a third person in the shot. Sven is still sitting behind them, but now even more tightly sandwiched between the faces–a tiny figure but fully discernible in the 35mm print. On the right I enlarge that portion of the image for you. Dead center, Sven’s tiny head floats between their profiles like a bubble from Nina’s lips or a rose between her teeth.

This is a remarkable shot. Since Nina eventually turns away and refuses Larsson’s kiss, we’re tempted to say that the shot creates a visual metaphor, suggesting that Sven “comes between” them. Fair enough, especially since the Danes have the same figure of speech (at komme i mellem). But I’d also want to signal how this possibility of thinly-sliced depth fits smoothly into the tableau style I’ve discussed many times on this blog and in my recently posted video lecture. It relies on hyper-precise staging in depth, accentuated by the axial cut (always a cut that accentuates depth).

It’s all the more remarkable because in those days, the camera viewfinder was mounted alongside the lens. We’re so used to reflex viewing–that is, seeing exactly what the lens of our camera or phone is framing–that we tend to forget that until the 1960s, in most cases a cinematographer had to compose the shot allowing for the parallax difference between the viewfinder and the lens. True, in most tableau shots the camera is far enough back to give some leeway for background planes, and some cameras could swivel (“toe in”) the viewfinder inward as the framing got closer. But this scene remains an extraordinary piece of filmmaking. The cinematographer Axel Graatkjaer, only twenty-six when he shot this film, deserves credit for pulling off a rare stunt.

The Mormon’s Victim is yet another example of the great variety and boldness of the cinema of the 1910s. Had I known it, I would probably have squeezed it into my video lecture, “How Motion Pictures Became the Movies.” Maybe I can work it into the followups I plan to post later this year. In the meantime, take this as another instance of why we should thank film archives for preserving fairly obscure films that have a lot to teach us about what talented creators have done with our favorite medium.

Ron Mottram surveys the local films of this period in his indispensable The Danish Cinema before Dreyer. For more on the tableau style, see the lecture I just mentioned, along with the blog entries in the category. I have more on Danish films and the tableau tradition here, and I discuss that tradition as a background to Dreyer in an essay on the Danish Film Institute’s Dreyer site.

Thanks to Thomas Christensen and Mikael Braae of the archive for all their help. I have devoted other entries to their archive and Danish film culture, but this might be the most relevant today.

Mikael Braae surveys a recently received collection of over 400 35mm film prints. He’s in the process of sorting and examining them. There are still big 35mm collections out there!

What next? A video lecture, I suppose. Well, actually, yeah….

DB here:

We’ve said several times that this website is an ongoing experiment. We started just by posting my CV and essays supplementing my books. Then came blogs. We quickly added illustrations to our entries, mostly frame enlargements and grabs. Eventually, video crept in. In 2011 we ran Tim Smith’s dissection of eye-scanning in There Will Be Blood. Last year, in coordination with our new edition of Film Art: An Introduction, we added online clips-plus-commentary (an example is on Criterion’s YouTube channel), and near the end of the year Erik Gunneson and I mounted a video essay on techniques of constructive editing.

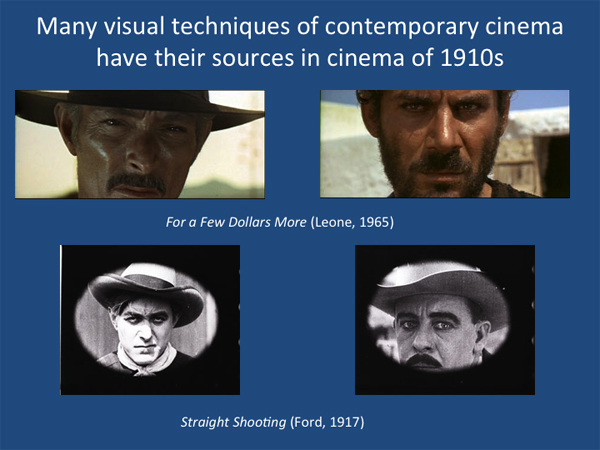

Today something new has been added. I’ve decided to retire some of the lectures I take on the road, and I’ll put them up as video lectures. They’re sort of Net substitutes for my show-and-tells about aspects of film that interest me. The first is called “How Motion Pictures Became the Movies,” and it’s devoted to what is for me the crucial period 1908-1920. It quickly surveys what was going on in cinema over those years before zeroing in on the key stylistic developments we’ve often written about here: the emergence of continuity editing and the brief but brilliant exploration of tableau staging.

The lecture isn’t a record of me pacing around talking. Rather, it’s a PowerPoint presentation that runs as a video, with my scratchy voice-over. I didn’t write a text, but rather talked it through as if I were presenting it live. It nakedly exposes my mannerisms and bad habits, but I hope they don’t get in the way of your enjoyment.

“How Motion Pictures Became the Movies” is designed for general audiences. I’ve built in comments for specialists too, in particular, some indications of different research approaches to understanding this period of change.

The talk runs just under 70 minutes, and it’s suitable for use in classes if people are inclined. I think it might be helpful in surveys of film history, courses on silent cinema, and courses on film analysis. If a teacher wants to break it into two parts, there’s a natural stopping point around the 35-minute mark.

Some slides have several images laid out comic-strip fashion, so the presentation plays best on a midsize display, like a desktop or biggish laptop. A couple of tests suggest that it looks okay projected for a group, but the instructor planning to screen it for a class should experiment first.

I plan to put up other lectures in a similar format, with HD capabilities. Next up is probably a talk about the aesthetics of early CinemaScope. I’d then like to spin off this current one and offer three 30-minute ones that go into more depth on developments in the 1910s.

The video is available at the bottom of this entry, but it’s also available on this page. There I provide a bibliography of the sources I mention in the course of the talk, as well as links to relevant blogs and essays elsewhere on the site.

If you find this interesting or worthwhile, please let your friends know about it. I don’t do Twitter or Facebook, but Kristin participates in the latter, and we can monitor tweets. Thanks to Erik for his dedication to this most recent task, and to all our readers for their support over the years.

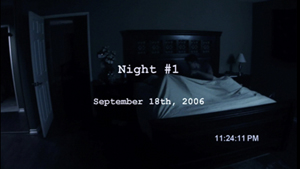

Return to Paranormalcy

Paranormal Activity (2007).

DB here:

What is there for me to do? Art historian Ernst Gombrich suggested that this is a problem that confronts every creative artist. If you want to make paintings or compose music or direct movies, you confront an existing community of artists and long-established traditions of art-making. You work with what you’re given. You inherit technology and materials, but you also inherit ideas and familiar conventions and well-worn work habits. You want to find a niche, but you’re also in competition with others for it.

You confront, in other words, a kind of ecosystem with its own history and a current state of play. How can you fit your talents and temperament into that ecosystem? How, more specifically, can you create something different?

Variorum moviemaking

Paranormal Activity (2007).

It can be useful to think of commercial filmmaking as this sort of system, a cooperative/ competitive arena challenging directors, writers, cinematographers, and other film artists to innovate. Innovation isn’t the only aim of moviemaking, of course, and just because something is innovative doesn’t mean it’s good. And not all innovations announce the fact; Jean Renoir’s deft uses of space in his 1930s films didn’t trumpet their originality. Innovation can be quiet and subtle.

Still, as students of the art of film, we’re naturally attuned to novelty—a fresh treatment of an established genre, an unusual approach to characterization, a new application of existing technology. If we’re interested in mainstream film, particularly Hollywood’s, we learn things from the way that filmmakers swarm over something new and try to mimic it or tweak it or turn it around. Make a movie about a possessed pre-adolescent girl who needs an exorcism, and soon we’ll have movies about possessed high-school girls, possessed dogs, possessed cars, and so on.

Call it the variorum quality of popular culture—the tendency to explore, sometimes exhaustively, all the possibilities of a single premise. Filmmakers seize an idea and run with it, in different directions. Of course they may be asking, “How can we cash in on this trend?” but in order to answer that they have to ask another question: “What if we did such-and-such differently?” Even if you start by trying to make money, you still have to make a movie. And that movie will need to be minimally distinctive. The question for the filmmaker remains: What is there for me to do?

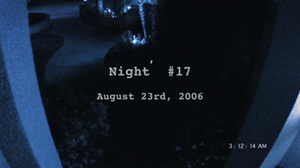

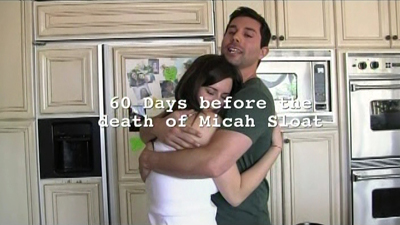

Something like this process is going on under our noses. Paranormal Activity (2007), Paranormal Activity 2 (2010), Paranormal Activity 3 (2011), and Paranormal Activity 4 (2012, released in October) have become a cheaply made but very successful franchise. Taken together, the four films have won estimated worldwide box-office revenues of $700 million and counting.

Their popularity offers one reason to examine them, but a better reason is that they make the variorum dynamic unusually clear. The originator and director of the first installment, Oren Peli, and the directors who followed (Tod Williams for the second entry, Henry Joost and Ariel Schulman for the last two, along with continuing writer Christopher Landon) were obliged to innovate within very tight limits. From movie to movie, they came up with fresh and unexpected solutions.

This isn’t about proving these movies to be masterpieces or stinkers. Whatever you think about the quality of the innovations I’ll be looking at, they offer us some leads about how filmic storytelling can change under the “selection pressures” of American commercial cinema.

More strikingly, the Paranormal Activity franchise is that rare thing: a popular series that stands out by very specific and noticeable uses of film technique. Audiences eat it up. The suspense and surprises are part of the appeal, certainly, but there’s reason to think that at least some viewers look forward to following each entry’s formal dynamic of familiarity and variation. Filmmaking becomes a kind of gamelike performance that coaxes us to ask: How will they deal the cards this time?

Of course there are spoilers from here on. Even the pictures contain spoilers.

The same, please, only different

The Blair Witch Project (1999).

The broad task that Peli faced when he began work on Paranormal Activity was clear: How to make a diabolic-possession film different from the others? By then, and still, that variant of horror was pretty well-defined. And indeed the film Peli came up with wasn’t that original in outline. A couple is disturbed by mysterious noises and actions in their house. They call in experts and try to find the source of the disturbance. Eventually the woman becomes possessed and kills her lover.

Throughout, the conventions of the supernatural film rule: sudden blackouts, bone-shaking noises emitted by offscreen fiends, and characters exploring basements, closets, moonlit yards, and other scary spaces. Special effects are invoked to levitate victims or drag them by unseen hands. Occasionally we’re faked out by scares launched as pranks that some characters pull on others. As usual, normal, i.e. bourgeois American life, is devastated by supernatural forces. Cozy domestic surroundings, including an array of consumer goods, become menacing. Much of all this was pioneered by The Exorcist (1973), so the tradition has plenty of cobwebs on it.

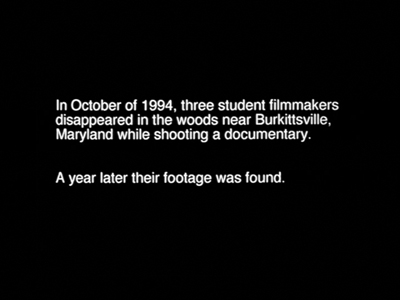

Shooting in seven days on a small budget, Peli settled on a formal framework that borrowed from another tradition, that of the pseudo-documentary fiction film. This too goes far back, to This Is Spinal Tap (1984) and Bob Roberts (1992), and before to Stanton Kaye’s Georg (1964), Jim McBride’s David Holzman’s Diary (1967), and Mitchell Block’s No Lies (1972) , and Peter Watkins’ Culloden (1964) and The War Game (1965). More distant predecessors might be Welles’ 1938 War of the Worlds radio broadcast, or even the fake memoirs we find in the early years of the novel. Today the pseudo-documentary mode, used for comic or dramatic purposes, is familiar to us from television shows like The Office. This mode has its own conventions, such as to-camera interviews and the occasionally awkward framing, most noticeable in the recurring image of a fallen camera.

The pseudo-documentary approach had been tried in the horror film in the 1980s, but it gained attention at the end of the 1990s with The Last Broadcast (1998) and The Blair Witch Project (1999). No surprise: Horror films tend to be low-budget items, and shooting in a run-and-gun manner, with handheld shots and awkward sound, was both cheap and realistic-looking. A cycle emerged, exemplified most notably in the bigger-budget Cloverfield (2008).

The problem of the pseudo-documentary is to motivate the fact that someone is filming these dramas. Various solutions have been worked out. You might make the protagonist a filmmaker exploring a subject or creating a diary. Or you can pretend that the people being filmed are celebrities (as in Spinal Tap). Or make the act of filming an effort to document dramatic occurrences. Filmmakers face a second problem as well: motivating how the film has been made public. You can, for instance, present it as a TV or theatrical documentary, as Spinal Tap purports to be. More recently another solution has been found. You can suggest that this film has been discovered after the events were over.

Because of this rationale, the approach is sometimes called the “found-footage” treatment, or in Varietyese the “faux found-footage film.” I’m not delighted by this term because for a long time “found-footage” has referred to films like Bruce Conner’s A Movie or Christian Marclay’s The Clock, assembled out of existing footage scavenged from different sources. So I’ll call fictional movies like Blair Witch and Cloverfield “discovered footage” films.

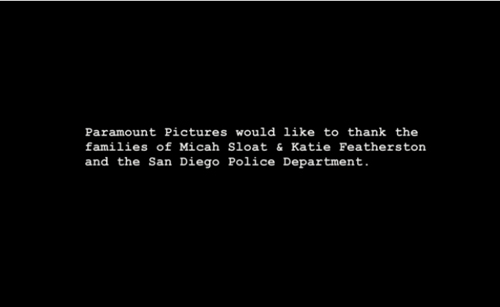

One reason for this name is that these films hark back to an early tradition of literary fiction, that of the “topos of the discovered manuscript” or “the old oak chest.” Here a tale is presented as a manuscript found and prepared for publication by other hands. The purpose, at first blush, is to give the story an air of authenticity. The same urge prevails in the discovered-footage horror movies, which use this blatant artifice to play with the possibility that these weird happenings really took place. As the image surmounting this blog entry suggests, Peli linked his film to this tradition, even letting the all-too-real company Paramount Pictures attest to the veracity of what we’re going to see.

The development of the Paranormal series took place under the sign of rivalry. A great many horror films of the late 2000s and early 2010s used the pseudo-documentary approach, sometimes marking the footage as recovered. After the success of Peli’s original film, intense competition emerged. There was a blatant ripoff (Paranormal Entity, 2009), followed by many others, including the subtler pseudo-doc The Last Exorcism (2010), which seems to presume that we’ll take it as a found-footage item too.

Just as important, in making successors to the original film, Peli and his colleagues had to compete with themselves. So they freshened up their plots. Paranormal 2 features not a live-in couple but a family; Paranormal 3 centers on an unmarried mother, her live-in boyfriend, and her two daughters. Paranormal 4 features a family whose neighbors are a possessed mother and son.

Interestingly, the subsequent films supply relatively little mythical or doctrinal backstory. Although there are always one or two scenes in which the characters launch on some research, the plots mostly minimize exposition about the hows and whys of possession. (Contrast The Exorcist.) We get just enough hints to assume that there’s a demon who offers women worldly goods in exchange for innocent boys’ souls. Mostly the films concentrate on the characters’ responses, chiefly their quarrels about whether the weird happenings are supernaturally caused. Each film needs at least one blocking character, somebody whose skepticism, obstinacy, or cluelessness keeps the plot going and prevents the characters from simply getting the hell out.

The films also vary protagonists and the characters we’re attached to. Micah moves the plot forward in the first entry with his urge to document the weird happenings, while in the second, the father Daniel and his daughter Ali take turns probing what’s going on. In the third film, again it’s mostly a male filmmaker, Dennis, who propels the inquiry, while in the latest iteration, the narrative momentum is passed to the inquisitive teenage girl Alex.

Perhaps the most up- to-date way the filmmakers refresh the franchise is by making the various films interlock. The films set up a chronology that positions the original release as the third phase of a larger action. Paranormal 2 occurs just before the events of the first one, and Paranormal 3 flashes back eighteen years to supply some preconditions for the previous entries. Moreover, some portions of the plots overlap, so that scenes from one installment are replayed in another, explaining how the time frames mesh. This sort of shuffling with time and perspective is nowadays common both within films and across them; the second and third Bourne films offer good examples.

Above all, the filmmakers have created a new ecological niche by virtue of some initial stylistic choices Peli’s first film made. They were striking but exceptionally constraining. To produce more Paranormal films created a very specific set of problems: How to respect those initial constraints and yet rework them in unpredictable ways?

Hand-eye coordination

Paranormal Activity 3 (2011).

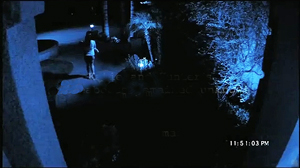

Cloverfield and The Blair Witch Project use the discovered-footage format to justify their amateurish look. These are on-the-fly records of some pretty strange phenomena. By contrast, the Paranormal Activity series doesn’t limit itself to handheld footage. It sets up a dynamic between that and something quite different: the fixed, distant shot reminiscent of surveillance footage.

The alternatives are laid out in the first film, when Micah, perplexed by the ghostly goings-on, buys a fancy video camera and sets it up in the bedroom he shares with Katie. That way he can capture what’s happening while they are sleeping. At other times he takes the camera off its tripod and shoots the house in the usual handheld, eyewitness way.

The result is a movie, and a series, with two markedly different visual treatments. The handheld footage is pure subjectivity, showing exactly what the camera operator sees. It responds immediately to what’s out there, panning or moving toward things of interest. It also permits fairly close shots of the other characters. By contrast, the locked-down shots are completely objective, recording in the manner of surveillance video. Indifferent to human intentions, the camera may be poorly placed to capture what’s happening. And it’s by and large committed to very wide and distant views, compared to the closer views yielded by the probing handheld lens.

Take the handheld technique first. This yields a severely restricted range of knowledge, as I’ve already discussed in relation to Cloverfield. This narrow range is suited for a film playing up mystery and suspense. In any given scene, we don’t know any more than the camera operator does. But of course this feature is also a drawback, because the filmmaker can’t build suspense through crosscutting—showing, say, a door creaking or a shadow moving somewhere else in the house.

The default for most fiction films is camera ubiquity. That is, in principle the camera can be anywhere and show us anything. If the camera doesn’t do that, you need special justification. So for thrillers or horror films, you can show just advancing feet or clutching hands or scary shadows, because we know that these genres promote gaps in our knowledge. We accept the obvious suppression of information.

Another way to justify not showing everything is attachment to one character’s range of knowledge. This is another common strategy of suspense and horror. Even more restrictive is an optical point-of-view treatment, which might be the polar opposite of camera ubiquity. Hitchcock was particularly keen to find ways he could drill into optical point-of-view as a narrative device.

Treating the camera as a vehicle for subjective POV can yield some sudden shocks. One of the most provocative ones in the Paranormal franchise occurs in the third installment, when Dennis approaches Julia at the top of the stairs. His camera-eye viewpoint makes her seem to be standing there, but as he approaches the perspective changes and we see that she’s actually floating.

In the same installment, the “Bloody Mary” encounter in the bathroom gains force not only through the camera’s limitation to Randy’s optical pov, but through the mirror that in the darkness reflects only the red dot of the camera’s “on” signal. It’s all we have to look at in a scene in which the sounds of thrashing and smashing overwhelm the image.

So the handheld subjective camera of Paranormal Activity and other films in the trend avoids camera ubiquity. This creates familiar problems, but filmmakers in this stylistic cycle have come up with solutions.

*How do you explain why the camera is recording this drama? The standard justification is that a crew has decided for some reason to make a movie about something, as in Spinal Tap and The Last Exorcism. Paranormal Activity finds two more pretexts. The video camera can record home movies in Daddy-cam fashion; this motivation is especially important in Paranormal Activity 2. Or the camera can serve to document the weird goings-on in the demon-haunted homes. This motivation is especially strong for the locked-down surveillance recordings.

The camera operator may be the protagonist or at least a major character. How do you show the character to the audience? Options: Have him or her shoot the act of filming in a mirror (very popular). Have him or her address the camera when it’s resting. Let other characters wield the camera and show the cameraperson. Or set the camera down and let it keep filming, often risking decentered compositions but still indicating things clearly enough.

Sometimes you want camera ubiquity. Shot/ reverse-shot cutting is especially valuable because it can emphasize major lines of dialogue and reactions. How can you achieve this in the subjective-camera style? By cheating a little. For example, a single-camera record can capture the give-and-take of a conversation only by either framing both people in a single shot or by panning between them. If you want proper shot/ reverse-shot cuts you have to use overlapping sound during editing to cover the moments when you stopped the shot or panned to reframe the other character. Even when you establish that two cameras are filming the action, you may have to cheat on position quite a bit. (See this discussion of a scene in The Office.)

Chronicle offers an intriguing example of how these problems can be solved. At the beginning Andrew, shooting into a mirror, explains that he has decided to film everything.

Throughout the early portions of the movie we get only what his camera sees, usually with him behind the viewfinder. But eventually we meet Casey, a young woman who has a camera too. The result is shot/ reverse-shot cutting justified as each camera’s viewpoint.

At the climax, when the boy superheroes fight it out above the city, so many people are filming the scene with cellphones, TV news cameras, and government surveillance, that the action is covered fully from many angles. The visual storytelling achieves camera ubiquity.

The impersonal view

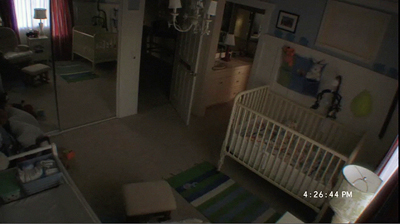

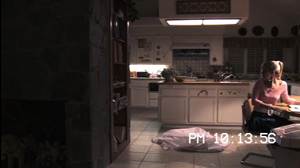

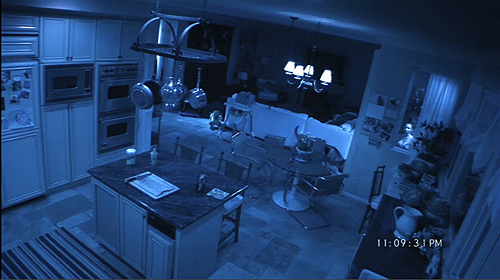

Paranormal Activity 2 (2010).

Many horror films have used the handheld approach, but the strongest innovation of the Paranormal series, I think, is the idea of counterweighting the free-camera shots with fixed-camera footage. Like the moving handheld shot, the locked-down surveillance shots avoid camera ubiquity and restrict us severely. But they have other advantages.

As we’ve seen, the fixed setup complements the human-centered handheld camera. It shows everything in front of it indiscriminately. By prying itself loose from the characters, and filming them while they’re not aware of it—especially when they’re sleeping—it allows us a more neutral sense of the film’s space and the things that happen in it. Just as important, it fits smoothly with some standard horror conventions.

For example, offscreen threats are central to the horror film, and the fixed camera can maintain their effects. As (bad) luck would have it, the cameras set up in Paranormal Activity aren’t always ideally framed for showing everything. Very often they merely suggest the demon’s pursuit of the characters. The demon Toby is just off left of frame in the third installment (he blasts some air at the babysitter Lisa) and some entity like Toby seems to be at work offscreen right in the second one, attracting Hunter’s attention.

Likewise, offscreen sound is crucial to the horror film, as Val Lewton and Jacques Tourneur showed long ago with the sudden intrusion of bus brakes into a suspenseful pursuit in The Cat People. The fixed camera can capture those sounds but because no human agent is behind it, there’s no way it can move forward to explore their sources, as a camera operated by a human might.

The surveillance shots, while limited visually, provide information that the subjective shots don’t. In the first film, while Micah sleeps, the bedroom-cam shows some weird goings-ons that he isn’t aware of—notably, Katie getting up and standing unmoving by the bed for several hours. In later installments, the presence of more than one surveillance camera can provide story information via crosscutting. As with Chronicle, multiplying surveillance views pushes the visual narration toward a more complete (and conventional) coverage of the action.

Crucial to the films’ innovation is the fact that the locked-down shots are distant views. The films have extraordinarily few shots for contemporary productions: about 230 in the first part, about 500 in the second (because of the multiple cameras), about 230 again in part three, and about 320 in the last. The number of setups is greater than these figures would suggest because some cuts are jump cuts or drop-frames within extended camera takes.

Long-take, locked-down shots are common in “festival cinema” but virtually unheard of in mainstream Hollywood film. Remarkably, we have box-office hits consisting of long, static takes that hold multiplex audiences in thrall. Of course the long “empty” takes are recruited to the conventional cause of sustained silence and sudden, startling outbursts. The genre, we might say, motivates the style. The same audience wouldn’t be so tolerant of a protracted shot in Tarkovsky or Hou.

Yet we shouldn’t dismiss these shots as mere gimmicks. Their stillness encourages us to scan these spacious frames for hints about what will happen next. The impersonal lens often lingers on bare spaces, and when something of interest happens we won’t be given a cut in. Sometimes the crucial action is barely there, as when Ali and Brad are hidden in shadow, behind the digital read-out, in the lower right of this shot.

To some extent, the distant framing of the surveillance shots revives classic staging techniques in a cinema that seems largely to have forgotten them. Instead of the barrage of close-ups and rapid shot changes we get with today’s intensified continuity style, we get lengthy, static, often indiscernible images we have to scour for clues.

Granted, often those clues are signaled through slight movements, as in the eerie twirling of the toy spider suspended over Hunter’s crib (top of this section). Centering is also important, as when the Ouija board’s planchette scuttles around and then bursts into flames. Sometimes a character can point to what’s important in the visual field.

For the most part, the static framings yield deep, dense compositions reminiscent of 1910s tableau cinema. In the second installment particularly, key bits of action are pushed very far from us or isolated in apertures. The kitchen camera setup lets Ali’s distant face poke up from the sofa into bare visibility (immediately below), or be framed in the window when she tries to get back in as Abby the dog approaches the locked door. (See bottom of this entry.) Unlike most modern films, these lose a great deal of information on small screens.

Overall, the handheld POV shot and the detached and distant long shot complement each other. Both are well fitted to the demands of the horror film, which requires secrets to be concealed from the characters while throwing out hints to us. Beyond genre conventions, though, these films might train the young audience to be patient and learn to settle into images that ripen slowly and don’t yield their meanings up immediately. Well, I can dream, can’t I?

Stretching the rules

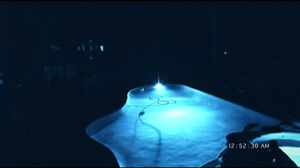

Paranormal Activity 2 (2010).

I’ve spoken of these films in general terms, but what makes the series particularly intriguing to me is the development from one installment to the next. The makers aren’t only competing with other filmmakers; they’re competing with themselves. Each new episode has to innovate within the framework they’ve set up—not only by expanding the story action, as we’ve seen, but also by varying the stylistic parameters. That generates new problems, self-imposed ones, and the search for new solutions.

The original Paranormal Activity sets up many of the stylistic premises of the series: the use of mirrors to introduce the camera and its operator, the idea that the investigator will replay the locked-down footage (and then film that with the handheld camera), and the need for at least one skeptical character who will resist the investigation. Here Micah has one camera, which he carries with him by day and installs on its tripod at night. And the resolution of the film is played directly to the camera, as Micah slips out at night to follow Katie and after a long pause is hurled back into the camera, smashing it to the floor. The tipped-over framing records Katie creeping forward, smiling, and roaring into the lens—her revenge on the filming she hated from the start.

Paranormal Activity 2 is largely a prequel, taking place about a year before the first one. Now the single camera is a daddy-cam, recording the arrival of Hunter, the baby born to Daniel and Katie’s sister Kristi. This camera is really a daughter-cam, because it’s mostly wielded by Ali, Daniel’s daughter by a previous marriage. She drives the investigation, but she’s initially more thrilled than afraid. (She also wonders if the ghost is her mother.) The situation shifts from a live-in couple (Paranormal 1) to a happy nuclear family (Paranormal 2) and from a midrange income level to a very prosperous one.

After the house is mysteriously ransacked, Daniel installs a home surveillance system. Six high-angle cameras cover the house. They’re trained on the front door, the back pool, the kitchen, the living room, Hunter’s room, and the master bedroom. In addition, we have Daniel’s Daddy-cam, now outfitted with night vision. This will become important in the climax, allowing us to glimpse, spasmodically, the demon’s response to the attempted exorcism of Kristi.

Naturally all these cameras yield a much-expanded range of knowledge. Now we can see at least part of what’s going on in various parts of the house, and the narration cuts freely from one room to another. Because of the shot scale, though, quicker cutting means that we have to run fast checks in each shot on whether anything seems dangerous.

Important shifts toward camera ubiquity, these new setups also can play a game with our expectations. For example, the eerie shots of the swimming pool at night show the bobbing pool cleaner sidling through the water. Yet Kristi points out that every morning the cleaner has been removed from the pool. The surveillance shots we see never show this, and not until late in the film, when other stretches of the surveillance footage are played, do we see it leave the water. Even sneakier is the tendency of the night footage to mislead us about what’s important. Nearly every night sequence begins with a shot showing the front stoop of the house, but nothing (so far as I can tell) is ever revealed by these images in Paranormal 2, though at the start of Paranormal 4 they pay off by showing Katie leaving with Hunter in her arms.

In context, Paranormal 2‘s recurring shot serves to announce a new sequence of hauntings, but it’s also a little amusing. The standard shot showing a safe household, with no one approaching, serves simply to remind us that the demon is already comfortably inside.

Paranormal Activity 3 is a more distant prequel, setting up the childhood of sisters Kristi and Katie. Here the novelty is the use of VHS tape to record the action. Again, the footage begins as Daddy-cam shooting, as Dennis films Katie’s eighth birthday party and then starts to make a sex tape with Julie. But when the spooky hijinks start, the man of the household decides to investigate. Unlike Micah, though, Dennis is a videographer by trade and so has three cameras at his disposal. He uses one as a handheld device, occasionally set up in his and Julie’s bedroom. He installs another camera in the girls’ bedroom and puts the third one downstairs.

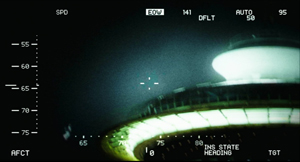

Reducing the “panopticon” of the previous installment from seven to three might be seen as a step backward, but the filmmakers have a clever innovation up their sleeve. Dennis can’t cover the downstairs adequately with his remaining camera. Out of a table fan he constructs a swiveling base to which he can attach a camera. This yields a panning back-and-forth framing.

Of course this mechanical panning is just as little concerned with items of human interest as the static shots of the earlier installments. Indeed, it maintains the horror-film convention of ominous offscreen action, but motivates it as impersonal scanning. The camera slowly reveals pieces of space, but if something exciting starts to happen onscreen, the camera relentlessly turns away.

Set in 2011, Paranormal Activity 4 is the first chronological sequel to the first entry, with a new cast of characters involved in action long after the initial demon outbreak. In some ways, making a teenage girl the protagonist is more conventional than the early films’ focus on couples. Still competing with themselves, the filmmakers needed to recast the series’ stylistic premises. They seem to have asked: Well, who uses dedicated video cameras today—especially if our characters are mostly teenagers? Accordingly, the franchise’s signature seesawing between handheld imagery and locked-down recording is now provided by cellphones and computers.

Although some footage purports to come from a video camera, most of it doesn’t. Alex and her boyfriend Ben set up four laptops around the house, all constantly recording what transpires in the rooms. This tactic allows some changes in the surveillance footage. The camera angle is typically lower than in Paranormal 2, since the laptops are sitting on tables or counters. Moreover, their framings can shift. In the boy Wyatt’s room, his laptop is sometimes closer or farther away, and is sometimes blocked by masses of blankets. The kitchen laptop is shifted around when Alex’s mother moves it closer to her work area.

In addition to recording the household’s supernatural doings, the laptop device lets the teenage heroine Alex have video chats with her boyfriend Ben. In the earlier films we get occasional to-camera monologues, but here we watch Alex talk close to the lens, directly to us, and at length; we see what Ben sees, and sometimes we see him from her screen’s vantage–a sort of virtual shot/ reverse-shot.

At crucial moments Alex picks up the laptop and carries it around with her. As a result, we get more conventional horror-film images of the protagonist—ideally an easily startled young woman—moving through space. In the earlier films, the camera operator’s reactions were given through the subjective framing and offscreen comments, curses, and yelps. Now when Alex hurries across the street to Robbie’s mystery house, we see principally her face.

Ariel Schulman acknowledged that the laptop device adheres to the “rules” of the franchise and the genre while producing, for the first time, conventional close shots of the camera operator. “We were really psyched just to do a shot where the girl’s carrying a laptop, and it’s just filming her. . . It just seemed like a really fun way to carry a camera and film ourself because otherwise there’s no other way to shoot close-ups in a ‘Paranormal’ movie.” Henry Joost adds: “The close-up on a teenaged girl’s face being scared is a horror movie icon. . . . If it’s dark, the only light is from the laptop screen, which is scary. It has all the right ingredients to be in a horror movie.”