Archive for the 'Film technique: Cinematography' Category

Stretching the shot

Walker (2012).

It’s the editor’s job to think about coverage, and mistakes at this stage can have a very high price. Without that shot of the murderous feet walking slowly down the stairs, it’s impossible to build suspense. Inexperienced directors are often drawn to shooting important dramatic scenes in a single take—a “macho” style that leaves no way of changing pacing or helping unsteady performances.

Christine Vachon

DB here:

Go to any ambitious film festival, such as the Vancouver one Kristin and I are attending at the moment, and you’ll see several films made up of unusually sustained shots. Some Asian and European films may even be made entirely of long takes; in a few instances, none of the scenes may employ any editing at all. Movies made wholly of one-take scenes, or sequence-shots (plans-séquences) are probably more common today than they have been since 1920.

Why so many long takes? In the 1990s, when Vachon was writing, imitation and competition probably did come into play. The Movie Brats were sometimes up-front about their boy-on-boy rivalry. Here’s De Palma after seeing the shots following Jake into the ring in Raging Bull:

I thought I was pretty good at doing those kind of shots, but when I saw that I said, “Whoa!” And that’s when I started using those very complicated shots with the Steadicam.

Something similar may have been going on in earlier times. It seems to me that in 1940s Hollywood, directors came to a new consciousness of the long take. Preminger, Ophuls, Sturges, and Welles became famous for their sustained shots, and even Hitchcock, a long-time proponent of editing, switched sides, making some of the longest-take films of the era. Sometimes an action scene might be played out in one flamboyant take, as in The Killers and Gun Crazy. It does seem that these big boys appearing to compete to see how long they could hold their shots and how complicated they could make them. One scene in Welles’ Macbeth runs a full camera reel, or about ten minutes; Hitchcock’s Rope contains only eleven shots.

Yet I don’t think that macho showoffishness or competition can completely explain the urge to shoot long takes. Watching the Vancouver Dragons and Tigers series leads me to consider some other options.

Long view of the long take

Naniwa Elegy (1936).

Of course there were single-take movies at the beginning of cinema, as in Lumière’s documentary shorts. And in the period 1908-1920, as I’ve argued in many entries on this site, some great films were made relying on single-shot scenes. They operated with a staging-driven aesthetic that’s come to be known as the “tableau” style.

But with the rise of American cinema to international prominence, and worldwide directors’ willingness to create scenes in the process of editing, the long take became relatively uncommon. In the 1920s, a rapidly-cut film might make occasional use of a long take, often as a fairly intricate traveling shot, as in Murnau’s Sunrise and Vidor’s The Crowd. Early talkies sometimes began with a long tracking shot (e.g., Sunny Side Up, Scarface) before settling into a more editing-driven style. And a few directors in Western cinema, like Max Ophuls, Jean Renoir, and John Stahl, handled extended dialogue passages in a single shot. A long-take approach was somewhat more common in Japanese cinema, with of course Mizoguchi Kenji being a prime exponent in films like Naniwa Elegy, Sisters of Gion, and Genroku Chushingura.

Citizen Kane probably helped popularize the long take in the 1940s, but so did the development of new camera supports. Dollies that could move through a set in tight turns encouraged directors to try out more sustained shots. For such reasons, most long takes of the period involved camera movement. Although Welles had his share of flashy tracking shots, he was one of the few directors who also let the camera stay fixed in place throughout a scene, in both Citizen Kane (Toland emphasized its “single, non-dollying” shots) and the extraordinary kitchen scene of The Magnificent Ambersons.

Occasional long-take shots have been with us ever since, some of them highlighting balletic camera-actor staging, as in Antonioni’s bridge encounter in Story of a Love Affair and many interior shots of Le amiche. By the 1960s, and 1970s, some directors became identified with long takes and even single-shot sequences: Tarkovsky most famously, but also Straub and Huillet, Miklós Jancsó, and Theo Angelopoulos. Fassbinder tried it out occasionally (Katzelmacher) as did Wenders (Kings of the Road). And of course in the avant-garde, devastating half-hour shots marked some works by Andy Warhol, not your most macho filmmaker.

There are still long-take films being made in the mainstream—not only those motivated as scavenged recordings like Cloverfield or Paranormal Activity, but also ambitious experiments like Children of Men. On the whole, however, long-take technique has become a hallmark of festival cinema. As commercial directors (not just in Hollywood) has embraced ever-faster cutting, other filmmakers have pushed toward ever-longer takes. It’s as if the rise of what I’ve called intensified continuity has provoked filmmakers to go to the other extreme. This impulse is thrown into still sharper relief by the fact that many of these festival films use little camera movement. And today’s shooting on video lets you hold shots a lot longer than shooting on camera reels.

But what does long-take cinema buy you?

Dragons, tigers, and stillness

A Mere Life (2012).

This year’s Dragons and Tigers series, the festival’s panorama of recent Asian cinema, had its usual quota of young people’s films about young people, not unlike America’s Mumblecore. The kids hang out, smoke, drink, flirt, berate each other, sometimes humiliate one another, occasionally come to a crisis in their lives. Other films were a bit more unusual. Several of all types, though, pointed up the virtues and limitations of current approaches to long-take shooting.

Most low-budget directors employing long takes don’t do so out of bravado or competitiveness. The reasons are more mundane: the tactic saves time and money. If you have rehearsed your actors, or if you want spontaneity and improvisation, you can get through a lot of your film more efficiently if you simply record the action. Editing in post-production comes down to choosing your best takes and finding the best arrangement of them.

For instance, Ninomiya Ryutaro’s The Charm of Others has about fifty shots in its eight-five minutes. Most scenes consist of only one or two shots. One seven-minute shot shows a young layabout Sakata trying to jolly his girlfriend out of dumping him. She’s seen him with another girl and tells him, “Eat first, then we’re through.” Instead, he pokes and tickles her, makes faces and jokes about liking to eat hair, and eventually wins her back. It’s a nice little examination of how men turn boyish, even babyish, when they’re trying to avoid a woman’s wrath.

Ninomiya, who plays Sakata, explains that although he had each scene’s core action fully scripted, he let actors improvise a fair amount during shooting. (Some specific words, however, had to be used.) The girlfriend scene was shot four times, the first three developing one approach to the action and the fourth take trying a totally different approach. Ninomiya wound up using the third take.

The Charm of Others is shot in a loose handheld style, with panning and tracking to follow its characters. This “free camera” technique is probably the most common way off-Hollywood directors employ the long take. The approach was on display as well in Mine Goichi’s The Kumamoto Dormitory. The plot follows a pair of slackers who want to work in films but lack ambition and anything approaching realistic expectations. More editing-driven, and somewhat more slickly made than The Charm of Others, it still averaged about eleven seconds per shot, a far cry from contemporary Hollywood’s average of five seconds or less.

For the most part, The Kumamoto Dormitory uses long takes in traditional ways–to record a scene’s interactions, and sometimes to create parallel story situations. In the beginning a lengthy shot drifts along dorm corridors as kids are moving in. One later in the semester shows boys in each room masturbating, playing mahjongg or computer games, and otherwise goofing off. Near the end another traveling shot shows the boys packing to leave as we hear an admistrator’s public speech describing how dorm life brings beginning students and graduating ones closer together. His inspiring line, “You were brought into the world because you were needed,” becomes ironic in the light of the dead-end hopes of a would-be movie director and his pal, an aspiring stunt man.

More rarely, the camera can be locked off during the long take, creating a static setup that may be refreshed by slight pans and reframings. Two of the films I’ve discussed earlier, Romance Joe and In Another Country, exemplify this approach; the former has fewer than 200 shots, the latter fewer than seventy. A similar approach, with a little more emphasis on dramatic compositions, is taken in Park Sanghun’s A Mere Life, a movie not about twentysomething crises but about the failure of a man to provide security for his wife and child. In a somewhat Mizoguchian tale of misery, most scenes are covered in only one or two fixed shots. There’s a striking scene in a café which obliges us to scan the background when a con artist bilks the husband and flees with his money. At another point, the camera’s refusal to budge and the director’s refusal to cut create considerable tension. Soon after the husband has lost the family’s savings, walls block our view of his desperate attempt to kill his wife and child.

The static long take is used in a more transparent way in Luo Li’s Emperor Visits the Hell, the winner of the Dragons and Tigers competition. The curious premise is that characters in present-day China are reenacting an episode in the classic saga Journey to the West. The reenactment, moreover, isn’t an affair of costumes or combat. It’s more abstract. For instance, the Dragon King is decapitated in the original story, but the Triadish character playing him in this film strolls around with his head firmly in place.

There are few single-take scenes, but the starkness of the décor and the fact that characters tend to be planted in a single spot give the film a sense of ceremonial gravity enhanced by the precise choices of camera position. Only in an epilogue, during the production’s wrap party in a restaurant, do the cast and crew assume their everyday identities. Then the camera goes handheld and roams bumpily around the table.

By the end Emperor Visits the Hell becomes a collection of contemporary long-take options: fixed versus moving, rock-solid framing versus shakycam.

Time on our hands

The long take has, we’re often told, another purpose: to capture real duration. Editing, it’s said, fragments not only space but also time. Whenever you cut, you have the opportunity to skip over dead moments. With a long take, especially a static one, the filmmaker is in effect asking us to register all the dead time between more important gestures, expressions, or lines of dialogue. This happens again and again in The Charm of Others, The Kumamoto Dormitory, and most of the movies I’ve already mentioned.

But the assumption of that “real time” flows through the shot can be questioned. The most common counterexample is slow- or fast-motion, which doesn’t respect the actual duration of the action the camera records. A rarer instance is offered by Tsai Ming-liang’s episode Walker in the portmanteau project Beautiful 2012, sponsored by the Hong Kong International Film Festival Society.

The action is bare-bones: A Buddhist monk walks through Hong Kong bearing a crinkly plastic bag in one hand and a sweet bun in the other. Across twenty-four minutes, twenty-one shots trace his progress through the city. In most the camera never movies, capturing the monk’s movement in static, sometimes abstract compositions. The catch is that the monk, played by Tsai regular Lee Kang-sheng, is advancing with preternatural slowness.

Sometimes we have to play a sort of Where’s-Waldo game with the compositions, searching for his stooped head or brilliant red robe or bare feet in a crowded shot. Most often, the emphasis falls simply on the monk’s movement. Hands lifted, head bent, he makes his way as if walking underwater. We watch each foot lift, shift weight, and descend in excruciatingly small changes of position. The movement proceeds not from camera trickery or CGI gimmicks; Lee’s performance presents a “temporal close-up” of humble, unstoppable walking. Meanwhile traffic, passersby, and other parts of his surroundings bustle along as usual. This is really stretching the shot–making the long take seem even longer.

One effect of these shots is to unroll an image of pure spiritual discipline, a sort of Zen exercise showing how microscopically an adept can control his body. Pedestrian yoga, you might say. Another effect Tsai creates is to summon up two times in one shot: that of normal activity and that of a spiritual tempo nestled within, but also opposed to, ordinary life. Eventually, when the monk bites into the bun, even that is rendered with the clarity of stop-motion photography. Here the long take exercises an almost scientific force, letting us see a simple act pulverized, as if a Muybridge image were translated into live action.

At the opposite extreme is the action-packed long take, running about seventy-five minutes, that comprises J. P. Sniadecki and Libbie D. Cohn’s People’s Park. The filmmakers had the good idea of taking us through a day’s pleasure in the city park of Chengdu, China, by means of a single traveling shot. A modern version of People on Sunday, the film unrolls a pageant of the everyday. People snack, trot past, make cellphone calls, rest on benches, sketch calligraphy on the paving stones, and above all make music. We see band concerts, karaoke performances, traditional opera, and spontaneous dancing to pop beats. The film starts with couples dancing and ends with an exuberant display of bouncy soloists who, we learned from Libbie Cohn after the screening, come often to perform for the sheer fun of it.

Just as important, instead of shooting at eye level, Sniadecki and Cohn filmed from a wheelchair. The lower-than-normal framing emphasizes kids, fills the frame with torsos, and yields unexpected revelations of figures in depth. We also get to watch a choreography of politeness as people subtly adjust to the camera as it squeezes through crowds or sidles among couples on a dance floor. Far from being the weightless, invisible camera of most Hollywood films, this camera and its carriage occupy actual space as the whole unit carves a sinuous path through the park. How, we sometimes wonder, will it get through here?

Many of the most famous long takes in film history are, we might say, teleological: They build toward a climax. Think of the tracking shot that opens Touch of Evil, beginning with a bomb set ticking and ending with an explosion. In a quieter way, the tableau aesthetic of the 1910s often gave the shot a distinct curve of interest, building to an expressive peak. (See here and here.)

And occasionally in today’s cinema, a shot that seems casual will subtly prepare us for a payoff. In The Charm of Others, a drinking game allows Sakata to tell others around the table what they must do. He orders two boys to kiss, and the girls join him in chanting, “Kiss! Kiss!” Those boys have already been present from the start of the shot, but now they become more than a pair of framing shoulders. Their obeying the order close to us furnishes an enjoyable topper for the take.

One problem facing the makers of People’s Park was the need to provide such a climax. As in Russian Ark, a single-shot feature film can’t simply stop; it needs to draw to a close, preferably on a striking note. In my view, Sniadecki and Cohn manage it. It would be unfair to tip you off–can there be such a thing as a stylistic spoiler?–but let’s just say it’s a moment of abrupt change within what is otherwise continuous, evenly-paced unfolding. Yes, dancing is involved.

In certain contexts, a long-take trend can, as Vachon mentions, exude a certain bragadoccio. Competition among artists, though, even with some bravado, isn’t necessarily a bad thing, as 1940s and 1980s Hollywood suggests. Sometimes as well the long take is an exigency demanded by time and money. It can yield artistic advantages, too, by building suspense (as in A Mere Life) or surprise (as in The Charm of Others) or both (as in People’s Park). It can also be a mark of virtuosity, a quality prized in most artistic traditions. A well-done long take can be like a sustained aria in an opera; its confident audacity can make you smile.

The epigraph quotation is from Christine Vachon’s Shooting to Kill (Morrow, 1998); the passage is available here. My quotation from Brian De Palma comes from “Emotion Pictures: Quentin Tarantino Talks to Brian De Palma,” in Brian De Palma Interviews, ed. Lawrence F. Knapp (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2003), 148. I discuss stylistic competition in contemporary American film in The Way Hollywood Tells It.

I consider Mizoguchi’s use of the long take in Chapter 3 of Figures Traced in Light. Some elaboration of that chapter is on this site.

Toland’s explanation for avoiding cutting is explained in his essay “Realism for Citizen Kane,” available here. For more on his decision-making, see our book, The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960, as well as this blog entry. For more on 1940s “fluid camera” technique, go here.

The segments of the film Beautiful 2012 began life as online videos. They are linked at Hong Kong Cinemagic. They play rather jerkily on my laptop, but the motion in projection is completely smooth.

My thanks to Tony Rayns and Shelly Kraicer, programmers of the Dragons and Tigers series, for their acumen and assistance.

People’s Park (2012).

You are my density

DB here:

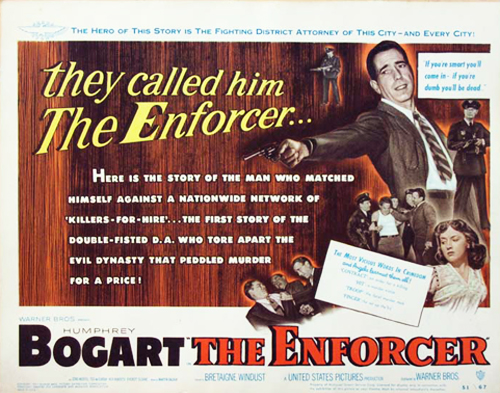

The mobster Joseph Rico is in protective custody; tomorrow he testifies against the big boss. But Rico fears reprisals, so he decides to escape. While a sleepy cop guards him in the washroom, he bends over the sink and rinses his face.

Turning so suddenly that water spatters on the mirror, he grabs the cop in an armlock and slams his head against the sink, just below the frameline.

Rico turns to the window to make his escape.

What interests me in this passage from The Enforcer (1951) is not just what happens in the mirror but also what happens on it. While Rico belabors the cop’s head, we’re given a chance to notice the splash of water that hit the mirror when Rico whirled to the attack. While the action is moving forward, we’re reminded of what had triggered it.

We get a sort of parallel reminder in the next scene, when we see the wounded cop again. He’s sporting a big bruise on his left temple, a souvenir of Rico’s assault.

Pfui. Details, you might say. Or you might (correctly) instance this as another case of Charles Barr’s enlightening notion of gradation of emphasis. But it’s worth getting a little more specific, because even this simple scene (by non-auteur director Bretaigne Windust) offers us something to think about, and something for today’s filmmakers to try.

Most films today don’t fully exploit the visual dimension of cinema. True, we have dazzling CGI and fancy camera moves. But when it comes to less flamboyant scenes, directors have limited their options by relying too much on stand-and-deliver and walk-and-talk. There are other aspects of visual storytelling that today’s filmmakers neglect. One aspect is the possibility of gracefully moving actors around the set in a sustained fixed shot. A specific tactic I’ve mentioned before is the Cross, and another involves ways to get people into a room. The option I’m going to sermonize about today is what I’ll call scenic density.

By scenic density I mean an approach to staging, shooting, and cutting in which selected details or areas change their status in the course of the action. I don’t count the bustle of background business, all that street traffic that is so much pictorial excelsior in our movies. Nor do I refer to stuffing the setting with desk and kitchen flotsam, allusive pop-culture posters, and the other distinctive “assets” that will be exploited when the film’s world gets transposed to a videogame. I mean something more expressive and intriguing.

Using it up

Go back to the Enforcer scene. The shot’s composition creates a delimited zone of action. The guard cop is framed tightly in the mirror. When the fight breaks out, it’s initially framed in that mirror–a narrowing of visual importance. Moreover, the shot is designed to highlight the spatter on the mirror. It’s fairly prominent, stuck near the center and, providentially, in the spot that the cop’s head initially occupied. The lighting picks out the drips, and in a shot where the figures move in and out of frame, there isn’t an equally constant center of interest. We’re probably concentrating on Rico’s punishing of the cop, but the dribbles of water remain prominent enough to claim our interest, especially when Rico passes out of frame.

So here’s my first condition for scenic density: the shot keeps several items of dramatic significance salient in the composition.

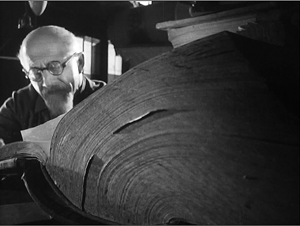

This technical choice asks the filmmaker to think of the frame as a field of dynamic masses and forces. Such an idea was part of the aesthetic of “advanced” European and Japanese silent cinema of the 1920s. Many directors explored this dynamism, often aided by low angles and wide-angle lenses. Here are examples from Eisenstein’s Old and New and Murnau’s Tartuffe.

This pictorial density became especially prominent in American cinema during the 1940s, when low angles, wide-angle lenses, and locations and smaller sets encouraged cinematographers to pack their compositions snugly, as in this shot from Panic in the Streets.

Boris Kaufman, cinematographer for Jean Vigo and Elia Kazan, summed up the principle:

The space within the frame should be entirely used in the composition.

Since cinema is a time-bound art, however, the salient elements in the shot could and should change. But if the frame space is wholly “used,” what room is there for change? The only options are to have the using-up elements shift position, or to reveal that the frame isn’t used up.

Vivid instances, also from the 1940s, can be seen in Anthony Mann’s work, both with and without John Alton. Generally, Mann used the new fashion for depth composition, especially big foreground elements, to heighten scenes of violence. Physical action becomes more aggressive if people rush the camera and halt in tight close-up, especially because wide-angle lenses tend to accelerate movement to the foreground. Mann thrusts violence abruptly to the camera with an almost comic-book effect, as when the club owner is shot in Railroaded, or a man is flung to the floor in Raw Deal.

Even when this in-your-face tactic isn’t employed, the Mann films find ingenious ways to develop what seem to be completely locked depth compositions. In Border Incident, Ulrich confronts the Mexican government agent Pablo, disguised as a Bracero. A looming depth shot is followed by a reverse shot displaying a compact composition.

Is the frame space fully used? The second shot above is opened up when Ulrich leans forward to sock Pablo, creating a vacant spot on the far right for Pablo to fall into. The shot is emptied and re-filled, dense once more.

Memories, memories

Aha, you may be saying. Density just refers to squinchy, fussy shots from an era that favored cheap flash. No. The Enforcer shot isn’t all that cramped. Of course the blank, unchanging walls serve to highlight the mirror-reflected fight and the water dribbling down the glass, but you can imagine how much more jammed and skewed Mann’s treatment of Rico’s escape would be. As for the flashier depth, I just needed some clear-cut cases of density, examples in which details and spatial zones become starkly salient. Now I want to suggest that scenic density can be achieved in something more spacious, even monumental. That has to do with time and memory.

Part of what gives the Enforcer shot its interest is the superimposition of two moments of action in a single space: Rico’s diversionary turn from the washstand, recorded in the splash he made on the mirror, and the struggle taking place a few seconds later. A further trace of that struggle and that splash is visible in the bruise on the cop’s head in the next scene.

That dripping spatter can stand in for the second quality of spatial density I want to highlight: Its capacity to coax us to recall earlier action in the locale. Characters leave their marks and spoors in the space, and those get activated as memories. Unlike the slick surfaces of today’s settings, in classic films the settings can bear the impress of human transit, leading us to recall bits of behavior and emotional states. Let me illustrate from Lang’s Hangmen Also Die (1943).

It’s Nazi-occupied Czechoslovakia, and Gestapo Inspector Ritter is questioning Mrs. Dvorak, the vegetable seller who could identify the woman who misled the officers pursuing an assassin. Torture, or at least what we think of as torture, hasn’t started. She is simply standing in front of his desk as he brandishes his riding crop in the manner of a good movie Nazi.

When Mrs. Dvorak denies knowing the woman, Ritter taps the back-rest of the chair. It simply falls off, and we realize it’s not fastened to the chair.

Ritter says, “Pick it up again.” Now we realize that intimidation has been applied for some while; Ritter has made the woman stoop to replace the back-rest many times. She does so again as the camera tracks back. This is nicely detailed too. She starts to pick it up by bending over, finds the effort too painful, and then goes to her knees to pick it up–just as Ritter taps his riding crop against her hand, a teacher gently chiding a slow pupil.

As Mrs. Dvorak rises to put the piece back in place, the camera pans slightly right to pick up the woman bringing in a tray. Happily Ritter sniffs the coffee jug and resumes questioning the old woman.

Cut to a shot of her by the chair. “Let’s start from the beginning,” says Ritter, offscreen. Unthinkingly Mrs Dvorak starts to rest her hand on the loose slat, forgetting that the top slat is unattached. It’s a natural response. She’s been standing there for a long time and would like something to rest on, and the chair is temptingly close. (Presumably, that’s its purpose, to taunt the unwary prisoner forced to stand a long time.) Remembering just in time, she yanks her hand away. If she knocks the back-rest off, she’ll just have to pick it up again.

Cut to Ritter. “Don’t be nervous, Mrs. Dvorak. I’m prepared to—”

Cut to Mrs. Dvorak. As he continues, “–devote to you all of tonight,” she forgets herself again and relaxes her hand, this time on the back-rest. It falls off, making her start.

She looks up as Ritter says, offscreen: “Even longer if necessary.” Cut to Ritter, gesturing with a piece of sausage and saying, coaxingly, “Well?”

Slowly she goes to her knees again as the camera tracks in on her.

Back to Ritter: “That’s the girl.” Back to her, rising in pain to replace the back-rest.

The scene concludes with Ritter reminding Mrs. Dvorak that she’s in Gestapo headquarters. She acknowledges that she doesn’t expect to leave without giving information. He starts his questioning all over again as the scene fades out.

This quietly suspenseful scene establishes a bit of furniture as a key prop. Once the faulty back-rest is marked for our notice, we’re expected to remember that it’s a means of intimidation–something that Mrs. Dvorak, in her anxiety about refusing to aid the Nazis, twice forgets. Lang’s shots, simple and uncrowded, makes the chair, like the spattered mirror in The Enforcer, preserve the trace of human activity. Yet it’s more acutely integrated into the scene’s drama than the mirror, and remembering how it was used earlier makes us wait tensely to see how it will be used again.

Long-term density

Several scenes later, the Nazis threaten to kill four hundred Czech hostages if the assassin isn’t turned over to them. Mascha Novotny has set out for Gestapo headquarters to denounce the man she helped, but she changes her mind and decides not to betray her country. She will only plead for her father’s life. Once more we’re in Ritter’s office.

Centered in the frame, standing out as a pale oblong against the grayer background, the fateful chair is made salient during Mascha’s conversation with Gruber. I suspect there’s a sort of spatial suspense here–will she move to the chair and dislodge the precarious piece of wood?–but more important, I think, is the fact that the chair ineluctably reminds us of Mrs. Dvorak and her quiet resistance to pressure.

Ritter leaves to consult his superiors. When he comes back, a new composition keeps the chair prominent and lends a new centrality to the clock on Ritter’s desk, surmounted by a snarling cat or something like it. (It’s visible in shadow in the earlier scene with Mrs. Dvorak.) But now the camera arcs to minimize the Dvorak chair and show the beast and Ritter targeting Mascha.

Soon enough, as if to make sure we remember, Mrs. Dvorak is brought back in, having undergone serious torture. The camera positions reactivate our memories of the earlier scene.

As she continues to lie to protect Mascha, Mrs. Dvorak never touches the chair. Although she has been tortured, she seems wearily defiant, as if her refusal to aid the Nazis has given her some strength: no need to lean on the chair now. As a final cue to our memories, Lang has Ritter play once more with his riding crop, letting its shadow fall on her heart.

The threat is clear: For lying, the old woman will pay with her life.

The chair reappears in a later scene, but I’d argue that then it serves more as a pointer to another prop. The resistance movement fights back by framing Czaka, a beer baron sympathetic to the Nazis, as the assassin. Lang could have explicitly recalled the questioning of Mrs. Dvorak by having Czaka lean on the slat and knock it off. Instead, the composition makes Ritter’s clock more important than it was in earlier shots. As Czaka tries to defend himself, the framing blocks our view of the chair but emphasizes the snarling catlike creature on top of the clock. And the chair has shifted a little off and become a bit darker; it’s no longer as salient.

This cluster of scenes from Hangmen Also Die illustrates how scenic density can add layers to a film. One scene recalls another not only by similarity of situation and locale but by tangible marks left on it by earlier action. Having seen Mrs. Dvorak subjected to Ritter’s oily intimidation, we generally expect something like it to be applied to Anna. This conventional situation is given a rich, concrete presentation by the repeated camera positions and the simple chair that, unmoving, enters into the drama.

Of course as a Hollywood director, Lang was pressured to reuse sets and camera setups. That saved money and time. But he turned such repetitions to his advantage by letting certain objects come forward at crucial moments. They not only become part of the drama but prime us to remember them, and what they revealed, in ensuing scenes. And even though Lang never pursued the aggressive, packed deep-focus of other directors working in the 1940s, he shows how roomier, less pressurized compositions could still be charged with echoes of earlier bits of behavior.

Is this sort of visual-dramatic economy, calling on precise memories of concrete actions, lost in today’s American cinema? I suspect it is.

In studying Hangmen Also Die, I was curious about a perennial problem. Was the byplay with the chair a Lang invention on the set, or was it some version of the script, or in the original story by Lang and Bertolt Brecht?

The film didn’t have a secret script, as the poster says, but the sources do remain a bit obscure. A draft of the original story signed by Lang and Brecht, in that order, exists. It indicates only that the greengrocer, called Frau Blaschke, is subjected to eight hours of “the usual Gestapo brutality” and refuses to identify the girl. There were other drafts of the screenplay, but I don’t have access to them, if they exist, and standard sources on Brecht in Hollywood don’t mention this scene’s details.

Somewhere along the line, though, the chair-back business was concocted. I found the shooting script signed only by John Wexley (Brecht claimed that he was robbed of credit) and annotated in pencil, perhaps by Lang. That script indicates that Ritter’s room contains “a vacant chair with its seat close against desk.” and Mrs. Dvorak is standing beside it as the scene begins. Much of the dialogue is the same , with some slight changes notated in pencil, possibly by Lang. But the camera movements indicated are different from those in the final film, and more importantly so are the actions. After Mrs. Dvorak claims that she doesn’t know the woman who helped the assassin, we read the following. I indicate pencil notations with {}.

In her fatigue, she places hand on back-rest of chair. But its dowels are loose and back-rest clatters to the floor.

RITTER (saccharine): Pick it up, Mrs. Dvorak.

CAMERA MOVES IN CLOSE as she obeys, stooping with painful fatigue–she has done this many times tonight.

RITTER: Now put it back in place, Mrs. Dvorak.

(She does so)

As Ritter questions her:

MED. SHOT – MRS. DVORAK. Without thinking, she is about to place hand again on loose back-rest–when she remembers and jerks back.

RITTER’S VOICE: Now don’t be nervous, Mrs. Dvorak…I’m prepared to devote to you all of tonight–and even longer, if necessary.

Mrs. Dvorak, unconsciously reacting to this, once more rests hand on chair. {She jerks back but} The piece of wood clatters to the floor.

MED. SHOT – RITTER. Ritter waits patiently; when she doesn’t move, inquires:

RITTER: Well…?

CAMERA PULLS BACK to INCLUDE Mrs. Dvorak, who stoops to repeat painful routine. Ritter smiles approvingly.

RITTER: That’s the girl.

Nothing here is indicated about Ritter’s riding crop, nor does he initially knock the back-rest off the chair. Mrs. Dvorak does it herself, accidentally. And the scripted line is “Pick it up, Mrs. Dvorak,” not, as in the finished film, “Pick it up again, Mrs. Dvorak.” The film version makes it clear that the byplay with the backrest is part of Ritter’s softening-up technique, something indicated in the script but not spelled out.

The later scenes in the film show other differences, mostly additions of things not mentioned in the shooting script. For instance, the script doesn’t mention the shadow of Ritter’s riding-crop. But the excerpt shows that the shooting script points toward some of the detailing we find in the finished film. It provides the sort of nudges that a director, especially one as oriented to gesture as Lang was, could elaborate on the set.

The Lang/ Brecht story has been published as “437!! Ein Seiselfilm,” in The Brecht Yearbook vol. 28: Friends, Colleagues, Collaborators, ed. Stephen Brockmann (2003), 9-30. The passage I mention, kindly translated for me by Ben Brewster, is on p. 16. Broader background on Brecht’s adventures in Hollywood can be found in James K. Lyon, Bertolt Brecht in America (Princeton University Press, 1980). Chapter 14 of Patrick McGilligan’s Fritz Lang: The Nature of the Beast (St. Martin’s, 1997) offers an account, mostly relying on Brecht’s viewpoint, of the making of Hangmen Also Die. The shooting script is in the John Wexley collection of the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research and the State Historical Society here in Madison. Thanks also to Marc Silberman, renowned Brecht expert, for advice.

Alignment, allegiance, and murder

House by the River (1950).

DB here:

“Point of view” is one of those terms that we can’t seem to do without, but it’s rather vague. The clearest application of the term would be to shots that conform more or less to what a character sees, presenting what we might call optical point of view.

But sometimes we’re given access to what a character sees, hears, and knows less narrowly. Without any optical pov shots, we might still be restricted to a character’s range of knowledge. This happens in detective films like The Big Sleep, which confines us almost completely to what Philip Marlowe knows. We follow him into scenes, stay with him as the action plays out, and then leave the scene when he does. We’re “with” him, but not via optical point of view.

In his book Engaging Characters, Murray Smith calls this sort of restriction to character knowledge alignment. He points out that it has both objective and subjective sides. Objectively, we’re spatially attached to a character in the course of a scene or several scenes. Subjectively, we may get access to the character’s thoughts, memories, dreams, or immediate perceptions (as with a POV shot). Spatial attachment refers to the limited range of our knowledge; subjective access refers to the depth of knowledge about the character’s inner experience.

But what about our emotional engagement with the characters? We usually call this “identification,” but Smith shows that this is a misleading way to think about what happens. Identification seems to imply taking on another’s state of being, but we don’t necessarily mimic a character’s emotions. We might pity a grieving widow, but she isn’t feeling pity, she’s feeling grief. Smith talks instead of allegiance, the extending of our sympathy and other emotions to characters on the basis of their emotional states. Allegiance, Smith maintains, depends partly on the moral evaluations we make about the character’s actions and personality.

Alignment and allegiance don’t necessarily involve us with only one character in the course of a film. Cases like The Big Sleep, which put us “with” Marlowe all the way through, are rare. Often a filmmaker shifts our alignment and allegiance away from one character to another, perhaps in the course of a single scene. That may involve some careful choices about staging, framing, sound, and cutting.

I offer you an example from Fritz Lang’s marvelously perverse House by the River. I’m afraid I can’t avoid spoilers, but at least I don’t give away the ending.

At the point of a nail file

Stephen Byrne, a struggling but well-to-do writer is married to the lovely Marjorie. But this doesn’t stop him from trying to seduce their maid Emily. While struggling with Emily, Stephen strangles her. With the help of his brother John, he stuffs Emily’s body into a large sack and deposits it in the river. Stephen’s crime has stirred something in him, and he begins writing a new book, Death on the River, with its plot based on what he has done. Meanwhile, an inquest into Emily’s disappearance casts suspicion on John as her killer.

The very end of the inquest scene has shown the prosecutor and chief inspector confronting Stephen, who says he won’t do anything to incriminate his brother. Since neither John nor Marjorie knows of this conversation, we’re aligned with Stephen. He now has precious information: the police are likely to be watching his brother, not him.

Our alignment with Stephen continues at the start of the next scene, which shows him at work on his manuscript. Marjorie comes in and asks to talk with him about Inspector Sarten.

After a pause to consider, Stephen reluctantly follows her into her bedroom. Lang’s camera, angled along the corridor, puts us strongly with him.

As Stephen enters the bedroom, Lang continues to favor him. Stephen comes into a knees-up shot facing front, but the answering shot of Marjorie weeping at the window is more distant, approximating his optical point of view.

Often filmmakers give us slightly stronger alignment with one character than another by framing one more closely than another. That happens here, I think, for Lang repeats these camera setups several times as Stephen apologies for being snappish and asks Marjorie what she wants to tell him. We know he’s being pleasant only because he wants information.

She comes forward and sits, reporting that she has seen the detective following her. Now we can see her expression more clearly and she is less remote from our concerns.

Again the setups repeat for a bit, with the framings still making Stephen more salient. Aligned with him, and to some extent allied as well, we are able to share his sense that danger is approaching. Stephen comes forward and steps into a more neutral and balanced framing. I’d argue that our sense of being “with” him now begins to taper off.

Marjorie points to the window (in one of Lang’s compositionally accented gestures) and suggests that an officer may be watching the house. Stephen goes to look out.

Stephen suggests that the police should be targeting John, since he’s acted suspiciously after the inquest. As Stepehn talks, he saunters to the dressing table and uses the file there to smooth his nails. He suggests that John may very well have had an affair with Emily. Although the framing is in long shot, we can see Stephen’s expression clearly, and it’s duplicated in the mirror. By contrast, when Marjorie rises indignantly and upbraids him, her back is mostly to us.

Stephen sits, remarking, “There’s a limit to this business of being brothers, Marjorie.” She turns slightly, saying, “Stephen, you’re insane.” This line prompts a cut to Stephen, still smoothing his nails but turned from us.

His face turned away and no longer visible in the mirror, Stephen says casually, “You’re very fond of him, aren’t you?” Now we’re more aligned with Marjorie, seeing more or less what she could see. Lang could have staged this phase of the scene to give us more information about Stephen’s expression (say a low-angle depth shot with his face in the foreground), but the opaque shot we get is balanced by a close, clear view of Marjorie for the first time in the scene–another step toward alignment and allegiance with her. The turned-away shot of Stephen also highlights his gesture of filing his nails, important in what will come next.

Cut to a medium shot of Marjorie’s reaction. “You know that.” Back to Stephen: “Are you in love with him?”

Stephen doesn’t see her reaction, which confirms his guess about her feelings for John, but we do. More important, our allegiance shifts toward her too. We know that Stephen is lustful (he’s seeing women in town every night), but Marjorie is suppressing her fondness for John for the sake of her marriage vows. She has the moral edge.

He questions her further, finally turning to her and grinning: “Don’t think I haven’t been aware of it.” Cut back to her: “You have a filthy mind”—something we know to be true. Her moral scheme fits ours, and sympathy for her builds.

This riposte wipes the smile from his face and he walks slowly toward her, the nail file extended like a knife, but also waggling jauntily in his hand. He recovers his flippancy and assures her he doesn’t feel any jealousy toward John because he no longer finds Marjorie attractive.

After he says he finds cheap perfume exciting, she calls him a swine. He resumes filing his nails. Stephen leaves the shot but, crucially, Lang’s camera dwells on Marjorie, glaring after him.

The scene’s final shot shows Stephen strolling down the corridor, and it ends with him smiling and slamming his door. It is a kind of symmetrical reply to the early shot of him going to her room.

This point-of-view shot anchors us with Marjorie, both perceptually and morally. She now realizes that she is the only ally John has.

Marjorie doesn’t know that Stephen is the killer and that John helped him dispose of the body. As often happens in films, we know more than any one character. As a result, we can register suspense when Stephen approaches with the nail file (we know he’s capable of stabbing her), but she evidently doesn’t feel herself in danger. To put it more generally, a string of scenes which restricts us to one character after another gives us a moderately unrestricted knowledge of the overall narrative.

Still, moment by moment, the director can use film technique to weight one character’s reaction more than another’s. We can balance those short-term reactions against our wider compass of knowledge. Our sympathies can shift as we register characters’ changing awareness of their situation, however partial their awareness may be.

Interestingly, the end of this scene, emphasizing Marjorie’s new understanding of Stephen’s turpitude, links to the next scene rather neatly. We see John at home, drinking with grim determination, but when he answers the door he finds Marjorie there.

The segue to Marjorie as a center of consciousness in the bedroom scene prepares for her going to comfort John.

More broadly, the shift initiates a new phase of the film in which Stephen must further cover up his crime. For nearly all of the film’s first half-hour, we’re restricted to Stephen’s ken, when he commits and covers up his crime. After that, the film’s narration alternates between scenes organized around Stephen and ones organized around John, with two brief ones centering on Marjorie. The inquest, at twelve minutes the longest sequence in the film, gathers together all the characters and functions as something of a neutral and objective reset.

That scene is followed by the one I’ve examined, in which we return to Stephen writing a manuscript, as we saw him at the start of the film. The new scene’s narrational weight briefly shifts, as we’ve just seen, from him to Marjorie. After she leaves John’s house, however, the film will build suspense by attaching itself almost wholly to Stephen as he plots to kill both his brother and his wife.

Smith points out throughout his book that alignment and allegiance are complicated matters. It sometimes happens that we have sympathy for the devil–someone who’s acted immorally but whom we might root for to some degree. Bruno in Strangers on a Train is a classic example. And we can think of instances of villains who engender some sympathy because they have some admirable features or because they are treated unfairly.

So I don’t want to leave you with the impression that Lang hasn’t toyed with our allegiances more severely in other stretches of House by the River. At the start, Stephen is at best a bounder, but who doesn’t want him to succeed initially in hiding his crime? (For one thing, if he didn’t try, the story would be over too soon.) And there may be something admirable in his cleverness and bravado as he tries to palm the guilt off on John. My discussion of this scene simply wants to show that the fluctuations of alignment and allegiance can be quite small-scale, and they often depend on niceties of directorial technique.

Craftiness

Artistry depends on craft, and craft is something both cinephile critics and academics have neglected.

Coming across that sentence in a recent essay in Film Comment, you might have a question. What is craft, and how is it different from artistry?

Some thinkers, most famously R. G. Collingwood, saw a sharp line dividing the two. I’m more inclined to see them on a continuum, at least in certain art traditions. In film, I’d suggest that craft consists in fulfilling the task at hand with skill and efficiency.

Craft implies a set of norms, a default or standard that any competent artisan should be able to fulfill. Artistry then, we might say, becomes a plus. It goes beyond the task’s narrow purpose. Ozu’s establishing shots, for example, do more than establish the locale of the upcoming scene. They create intricate plays with compositional motifs that recur through the entire film. Artistry may not necessarily add complexity, though; it can also compress and concentrate. Bresson eliminates establishing shots and providing environmental information through glimpses of background or information on the soundtrack.

Sometimes artistry adds a psychological complexity not apparent in the bare-bones task. This might be given through performance and/or the way the scene is shot. This is what I think happens in the House by the River scene. It’s not a flamboyant job of direction. We need to take a little effort to see how Lang has set up the master shot to allow Stephen to go to the window, then to the dressing-table; and to see how Lang has reserved the closer shots of the couple for a new level of conflict.

But so much might have been done by any solid artisan. And you could imagine other ways to shoot the scene. Someone like Preminger might have presented the entire encounter in a few balanced two-shots. Lang’s extras—the discreet use of optical point of view, the analogous corridor shots, and the subtle variation in shot scale between Stephen and Marjorie, not to mention Stephen’s playful waggling of the nail file—build subtle attitudes toward the characters.

Call it artistry, or cunning craft. Either way, it shows how directors can shape our experience by adjusting the range and depth of our knowledge, sometimes in small but powerful ways.

The distinction between range and depth of information in cinematic narration is presented in Film Art: An Introduction, Chapter 3 and in my Narration in the Fiction Film. For more on these concepts, see Meir Sternberg’s Expositional Modes and Temporal Ordering in Fiction. Murray Smith’s Engaging Characters refines these and other distinctions in order to understand how we grasp character in film.

Tom Gunning’s The Films of Fritz Lang offers a detailed, fascinating commentary on House by the River, concentrating especially on motifs of writing, mirroring, and filth.

For other entries on the craft of staging dialogue scenes, go here and here and here and here elsewhere on this site. For more on niceties of direction, from a director seldom credited with such, try here.

House by the River (1950).

Endurance: Survival lessons from Lumet

I don’t believe in waiting for the masterpiece. Masterful subject matter comes up only rarely. The point is, there’s something to advance your technique in every movie you do.

DB here:

Across half a century he outpaced his contemporaries. He was the last survivor of the vaunted 1950s generation of East-Coast TV-trained directors, men who went over to theatrical films just as the studio system was in decline. John Frankenheimer, Martin Ritt, Richard Lester, and Franklin J. Schaffner won big projects early on, but they also faded faster. As they were moving out of the game in the 1970s and 1980s, Lumet was getting his second wind. He ground movies out–good, so-so, or wretched–like a contract director of the studio days. Sometimes he had a strong stretch, as in the early 1980s, and sometimes not. He started in his early thirties with Jean Vigo’s cameraman Boris Kaufman, shooting crystalline black and white. At the end he was making a feature in high-definition video.

When Lumet died on 9 April, journalists were generous in their praise. But most of the eulogies seemed to me constraining. They overlooked his complicated role in postwar American film, and they neglected to supply the sort of historical context that make even his negligible films of interest. Concentrating on his official masterpieces (Dog Day Afternoon, Network), the obituaries cast him as a hard-nosed urban realist. That’s part of the story, but if we want a fuller picture of this long-distance runner, we need to trace his path in more detail. That in turn can teach us something about shifting generational opportunities in American cinema.

We can start by noting what the recent accolades seem to have forgotten: at the start of his career Lumet faced brutal hostility from the critical intelligentsia that ruled his home town.

Danger man

The Pawnbroker.

Reading 1960s film criticism, you might think that Sidney Lumet was the biggest threat to film art since the Hays Code. Young cinephiles today may be unaware of the vituperation that New York’s highbrow critics showered on him at the start of his career.

John Simon: “What is Lumet good at? Intentions, underlining, and casting.”

Manny Farber: “Giganticism is, of course, the main Lumet contribution [to The Group]. . . . Miss [Shirley] Knight, in a concentrated post-coitus scene atop [Hal] Holbrook’s chest, has a head the size of a watermelon.”

Andrew Sarris: “The Pawnbroker is a pretentious parable that manages to shrivel into drivel.”

Most tireless was Pauline Kael, who throughout the decades picked off nearly every Lumet movie with the casual contempt of Annie Oakley shooting skeet. From the backhanded compliment (“The Pawnbroker is a terrible movie and yet I’m glad I saw it”) to the eviscerating dismissal (Deathtrap is “an ugly play and what appears to be a vile vision of life”), Kael did not relent. She found Lumet’s staging “slovenly,” his color schemes inept; in Serpico “scene after ragged scene cried out for retakes.”

The hunt was in full cry in Kael’s 1968 essay, “The Making of The Group,” one of those behind-the-scenes journalistic forays that always end in tears for the production. Every such think-piece mysteriously assures the film’s commercial failure, while guaranteeing that posterity will remember each participant as a knave or a fool. Yet for sheer bloodthirstiness, Kael’s reportage easily surpasses that of her predecessor Lillian Ross in Picture.

Kael is out to show that the conditions of acquiring, producing, and marketing films have become almost utterly corrupt. No artist can survive the system. So she starts by establishing Lumet as merely a journeyman, shooting the script as a straightforward job of work.

But then things get rough. He is, for one thing, a poor craftsman.

He cannot use crowds or details to convey the illusion of life. His backgrounds are always just an empty space; he doesn’t even know how to make the principals stand out of a crowd . . . . Lumet is prodigal with bad ideas . . . . He will take the easiest way to get a powerful effect; in some conventional, terribly obvious way he will be “daring” . . . The emphasis on immediate results may explain the almost total absence of nuance, subtlety, and even rhythmic and structural development in his work. . . . I was torn between detesting his fundamental tastelessness and opportunism and recognizing that at some level it all works. . . . Because Lumet can believe in coarse effects he can bring them off.

He is also a severely deficient human specimen.

[He was] the driving little guy who talked himself into jobs . . . He seems to have no intellectual curiosity of a more generalized or objective nature . . . For Lumet, a woman shouldn’t have any problems a real man can’t take care of . . . . He’ll go on faking it, I think, using the abilities he has to cover up what he doesn’t know.

Kael has her generous moments, praising Long Day’s Journey into Night (1962), chiefly because of the performers, and in later years she would admire scenes in Dog Day Afternoon (1975). But usually her admiration boomerangs into a complaint (Lumet yields a fast pace, but that makes him slapdash). On the whole she and her Manhattan peers, who seldom agreed on anything, conceived Lumet as dangerous.

Why? Partly because they mostly set themselves against the middlebrow culture of the newspapers and newsweeklies. Many of Lumet’s early films were admired by staid critics. Praise from these quarters was anathema to the sophisticates. Somebody had to tell the Times’ Bosley Crowther that The Pawnbroker (1965) was not “a powerful and stinging exposition of the need for man to continue his commitment to society.”

Another strike against Lumet was his pedigree. He was said to have brought TV technique, simultaneously bland and aggressive, to theatrical cinema. Early live TV drama, confined by the home screen’s 21-inch format and weak resolution and hamstrung by punishing shooting schedules, pushed directors to rely on flatly staged mid-range shots, goosed up with close-ups, fast cutting, and meaningless camera movements.

Kael suggests that Frankenheimer, a common foil to Lumet at the period, managed in films like The Manchurian Candidate (1962) to convert the TV look into “a new kind of movie style,” though she never explains what that consists of. By contrast, Lumet simply followed the line of least resistance, emptying out his shots and “hammering some simple points home.”

There’s nothing on the screen for your eye to linger on, no distance, no action in the background, no sense of life or landscape mingling with the foreground action. It’s all there in the foreground, put there for you to grasp at once.

The TV style threatened to suffocate the glories of cinema: the full view, a more leisurely unfolding of action, a sense of life flickering on the edges of the plot. For Kael the TV-trained Lumet exemplifies the loss of the great tradition of artistic moviemaking personified in Jean Renoir.

Lumet was dangerous in another way. He seemed part of a trend toward heavy-handed showoffishness. Partly the trend was seen in the sweaty strain of Method acting, typified in Kazan’s work. Manny Farber proposed that the Method was at the center of the “New York film,” a fake realist package predicated on psychodrama, arty compositions, and liberal pieties. 12 Angry Men was “counterfeit moviemaking,” filled with “schmaltzy anger and soft-center ‘liberalism.’” Hard-sell cinema, Farber called it. Dwight Macdonald saw the same bludgeoning in The Fugitive Kind.

Lumet’s direction is meaninglessly over-intense; lights and shadow play over the close-up faces underlining lines that are themselves in bold capitals; every situation is given end-of-the-world treatment.

The new tendency toward self-conscious artifice didn’t just have New York roots. The French New Wave’s somewhat disjunctive cutting, unexpected camera movements, freeze-frames, and other flagrant techniques made audiences and filmmakers aware of film style to a new degree. Tony Richardson, John Schlesinger, and other directors scavenged these devices to give their films an up-to-date panache. Once more a critic needed to invent a new label for Lumet: Macdonald claimed that he was an exponent of the Bad Good Movie, “the movie that is directed up to the hilt, avant-garde wise,” in the vein of Mickey One, The Servant, The Trial, and the work of Godard. The Pawnbroker’s fragmentary flashbacks led Sarris to call it Harlem mon amour.

Harsh as they are, these comments do have a point. The early films shout and scream a lot, both dramatically and pictorially. Lumet admitted his love of melodrama, conceiving it not simply as overplaying but rather as conflict at the highest pitch of arousal: extreme personalities in extreme situations. So a silence is usually prelude to an outburst, and a bellow or a slap is never far off. The jury deliberations in 12 Angry Men (1957) become a group therapy session (or an Actors Studio class?) in which bigots must confess their traumas.

Stage Struck (1958) and The Group (1966) are pictorially innocuous, perhaps partly because they were shot in color, but The Fugitive Kind (1960) is a banquet of elaborate lighting effects whipped up by Kaufman. Macdonald wasn’t fair in his dismissal; the film is dominated by medium and long shots, with close-ups held in reserve for big moments, and the line readings don’t seem to me as overbearing as he suggests. Still, there is a sense of pressure, with very precise reframings and sets densely packed (mirrors, curtains, staircase railings) in a way that accords well with Williams’ overripe dialogue. There is an upside-down shot, and at some moments, as Macdonald notes, the illumination lifts or drops in magical ways—a surprise gift, Lumet claims, from Kaufman.

As a pluralist, Lumet would stage some scenes in full shots and long takes, sometimes at a surprising distance from the camera. But it was hard not to notice the other extreme. His most famous black-and-white films mixed in tight close-ups, oppressive sets, wide-angle distortions, and chiaroscuro. 12 Angry Men is relatively subdued in this regard, building toward more looming images at the climax, with some powerfully jammed ensemble frames.

Fail-Safe (1964) surrenders itself to flamboyant shot design once we get into the war room and then into the President’s sealed chamber. Contra Kael, as in 12 Angry Men, many of these shots have busy backgrounds, albeit not of the Renoirian sort.

The Pawnbroker (1965) is Lumet’s most famous orgy of strident technique, with Sol Nazerman nearly as caged at his counter window as he was in the camps. Even more overwrought is The Hill (1965) in which short lenses pump officers’ raging faces into gargoyle shapes, with pores and welts and gobs of sweat thrust under our noses.

In sum, this is not the director eulogized in Entertainment Weekly: “He never tried to dazzle audiences with flash and style.”

What critics didn’t note, however, was that the more outré look cultivated by Lumet, Frankenheimer, Ritt, and company fitted fairly snugly into 1950s Hollywood black-and-white dramatic style. The blaring deep-focus and violent close-ups exploited by the TV-born directors were already visible in the work of Mann (The Tall Target, 1951, below), Aldrich (Attack! 1956, below), Fuller, and many other directors.

During the 1950s what we might call roughly the “post-Welles” look was well-established for serious subjects and genre pictures alike. The Hill pushes things a bit, as Frankenheimer did in Seconds (1966), but the cramped, low-angle style on display in Lumet’s early work is part of a tradition that goes back years (and which had its echoes in many overseas directors, such as Bergman and Fellini). The wilder reaches of that style, it now seems clear, belonged to Fuller and company, not to mention the Kubrick of Strangelove and the Welles of Touch of Evil. Like Richardson, Schlesinger, and others, the TV émigrés may have gotten their wrists slapped for trying to map onto prestigious social-message movies the visual pyrotechnics already acceptable for program pictures.

Not incidentally, some directors had already found the wide-angle deep-focus look useful in their TV productions. Below are frames from Requiem for a Heavyweight (directed by Ralph Nelson, Playhouse 90, 1956); The Defender (directed by Robert Mulligan, Westinghouse Studio One, 1957); and Lumet’s own omnibus program Three Plays by Tennessee Williams (Kraft Television Theatre, 1958).

You can argue that their move to cinema actually smoothed out the directors’ style. The less square frame and bigger scale of the theatre screen made films like Frankenheimer’s debut The Young Stranger (1957) more spacious and relaxed than what could be seen on the box. 12 Angry Men was a polished effort, starting with an elaborately staged six-minute crane shot assembling the cast in the jury room, and using the width of the screen to enclose several faces. Looking back, we can see that Lumet offered something quite close to then-current Hollywood norms, and it looked less crude than what would be found on live TV of the period.

Still, The Pawnbroker and other films can be credited (or blamed) with helping spread the in-your-face style that would come to dominate American cinema of the next fifty years: disjunctive editing, slow motion, the arcing tracking shot (The Group), handheld shooting for moments of violence or anguish, glum color schemes (preflashing for The Deadly Affair), the teasing flashbacks that will be gradually filled in. Lumet’s early films are anthologies of most of today’s tics and tricks.

Yet by the time of his death, the director who was once feared as the vanguard of something new and awful had come to embody something old and trustworthy. Somehow the unambitious journeyman and pretentious copycat became a “classicist.”

How did that happen?

A prince of the city

Before the Devil Know You’re Dead.

Instead of indicating that he was joining or extending a tradition, Lumet reacted to the hailstorm of criticisms with surprising equanimity, at least in the interviews he gave so abundantly throughout his career. He was modest, acknowledging that many of his films turned out to be feeble, and he declared himself a learner. He tried different projects, he said, to improve himself. He wanted to learn to manage color, to work in different genres (e.g., the dark comedy Bye Bye Braverman, 1968), eventually to fall in love with digital video capture. To some extent Lumet changed because he really wanted to learn more and explore various sides of moviemaking.

Lumet always claimed that he didn’t apply a personal style to his projects; he tried to find the best way to handle the script. He thereby confessed himself to be what auteur critics of the 1960s were calling a “metteur-en-scène,” the director who judiciously enhances the material rather than transforming it to suit his personality. This was probably a good survival strategy in the new churn of the 1970s.

The mid-1970s was the Great Barrier Reef of American cinema. Virtually no members of Hollywood’s accumulated older generations, from Hitchcock and Hawks through the 1940s debutantes (Wilder, Dmytryk, Fuller, Siegel) and the 1950s tough guys (Aldrich, Brooks) to the TV émigrés, made it through to 1980. Many careers just petered out. The future belonged to the youngsters, the so-called Movie Brats. In this unfriendly milieu, Lumet fared better than most. He tried a semifarcical heist film (The Anderson Tapes, 1971) that mocked the rise of the surveillance society, with everybody wiretapping and taping and videoing everybody else. He mounted a classic mystery (Murder on the Orient Express, 1974), a musical (The Wiz, 1978), and a free-love romance (Lovin’ Molly, 1974). Of the items I’ve seen from these years, the most daring is The Offence (1972). This study of a sadistic British police inspector’s vendetta against a child molester offers a sort of seedy expressionism. In another gesture toward psychodrama, long conversations with the perpetrator reveal that the copper is a bit of a perv himself.

Lumet’s most successful rebranding took place in a sidelong return to the Pawnbroker milieu: low-end, location-shot, crime-tinged social commentary using New York theatre talent. Filming in color and casting off the baroque precision of the earlier work, he made his compositions more casual and his shot changes less precise. His cutting pace picked up: six seconds on average for Serpico (1973), five for Dog Day Afternoon (1975), both courtesy of the high priestess of the quick cut, Dede Allen. The driving tempo of these movies gave them an urgency that critics could tie to the ticking-clock plots, the atmosphere of urban pressure, and of course the extroverted acting of Al Pacino.

With the two crime films, and the satiric Chayefsky talkfest Network, Lumet remade his image. He was a New York filmmaker, offering raucous, hard-nosed, semi-cynical takes on corruption in the police, the justice system, politics, and the media. His protagonists tended to be Jews, Italians, and Irish, all working stiffs or bare-knuckle power brokers; and the enemy, again and again, turned out to be the Ivy elite. A tailor-suited WASP, male or female, was likely to sell you out. Only ethnic minorities knew the real score. The line could come from almost any mid-career Lumet film: “I know the law. The law doesn’t know the streets.”

The crowning achievement in this vein, for critics if not for audiences, was Prince of the City, a sprawling study of a cop’s patient years of taping and informing on his corrupt colleagues. More slowly paced than the earlier urban dramas, the film also marked Lumet’s move toward something else again. The style was drier and more sober, almost passive, emphasizing static and somewhat distant setups; the cutting slowed down to nearly nine seconds on average. As mid-period Lumet had blotted out the early years, now something more calm, even comparatively austere, came into view.

Whatever the project, however, by the later 1980s he was offering his own alternative to the fast-cut, whirlicam style that was bewitching young filmmakers. While directors in all genres were building scenes out of endless choker close-ups and cutting every four or five seconds, Lumet applied the brakes, lingering on two-shots, letting whole scenes play out in full frame, moving his actors around and ordaining a cutting pace close to ten seconds on average. The first eight minutes of The Verdict (1982) consist almost entirely of long shots and extreme long shots. The protracted takes and antic bodily contortions of Deathtrap might have come from a French boulevard farce; the first tight single of Christopher Reeves is delayed for half an hour. In an age in which critics decried the choppy confusion of tentpole action, the plainness on display in movies like Running on Empty (1988) and Night Falls on Manhattan (1997) looked anachronistic. Right to the end, Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead (2007) could spare a lengthy and distant shot to register a high-end drug boutique and shooting gallery. We had come from the Hysterical Lumet by way of the Gritty Lumet to the Restrained Lumet.

Acting in the frame

Yet he did not milk the urban crime vein dry. He continued to try a wide range of projects, even probing the Red Scare in Daniel (1983). The rationale was chiefly performance. Lumet was an “actor’s director.” He demanded at least two weeks of rehearsals, which included not only table readings but eventually full blocking of scenes, including fights and chases. Derived from his TV and theatre days, the method suited his belief that actors needed a firm structure in order to invent their characters. Interestingly, this actors-first rationale can be adjusted to any phase of the rough stylistic development I’ve plotted. The high-pressure facial shots of the early films can highlight the minutiae of the performances. But so can mid-shots that let actors build in bits of business.

Manny Farber praised the moment when Fonda in 12 Angry Men dries his fingers at length, one by one. It shows, Farber says, “the jury’s one sensitive, thoughtful figure to be unusually prissy” and provides a “mild debunking of the hero.” But it’s not the unintegrated detail Farber claims; Fonda’s coldness is set up early in the film, when he stands remotely from his peers and shows no interest in them as men. And Fonda was always a master of finger-work, which Lumet could exploit in fastidious framings. In Fail-Safe as the President tries to halt the bombers rushing toward the USSR, Fonda projects the man’s minutely controlled apprehensions by pausing to rub his fingertips together, off in the corner of the shot.

This micro-gesture suddenly leaps, as Eisenstein might say, into a new quality: a worried facial expression.

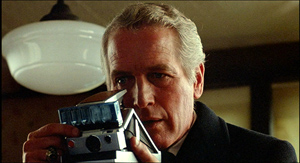

More explicit is the characterizing moment in The Verdict when Frank Galvin (Paul Newman) starts his day with a sugar donut and a full glass of whiskey. The setup is concise: He has crossed off the wakes he’s visited, and his palsied hand can’t pick up the glass without spilling some.

So Frank checks to see if anyone is looking before, like a dog, he bends his head to slurp off a little.

It’s a simple but powerful image of degradation, far removed from the trembling mouth and bulging brows of Steiger in The Pawnbroker.

Lumet cared as much for camera technique as for acting maneuvers. His book Making Movies provides a virtual manual of movie style as draftboard engineering. His gearhead side was probably another legacy of the buccaneering days of live TV and the New-Wave inspired awareness of artifice. He took inordinate pride in his “lens plots” and lighting arcs, charting purely technical changes that would weave their way through the film. (In this he was ahead of his time; now most filmmakers develop these technique arcs, or at least they say they do.) Despite this almost mechanical conception of technique, though, late Lumet rediscovered a bare-bones simplicity of performance and framing that was willing to risk looking flat. In Daniel, he lets the angry young man whose sister has wasted away into madness confront the poster agitating for their dead parents. No tracking in, no circumnambulating camera, no heightened cuts or nudging score. And no need to see Daniel’s face. Susan merely lifts her head.

It’s as if the visual rodomontade of the Movie Brats drove Lumet toward a new sobriety. When Galvin is preparing to try the case of the girl left in a coma through medical malpractice, he visits the hospital and takes Polaroids of her inert body. The slowly developing images not only give us the fullest view of the girl we’ve had so far. They also come to suggest his dawning realization that this is more than just a chance for big money.

Galvin starts to grasp that letting the hospital settle out of court will allow the officials to write off their mistake. There is a human cost to simply getting the check. If he does it, he will now be a better-paid ambulance chaser. Yet he doesn’t stand valiant for truth; the drunk is scared, drained of dignity, and he clutches his portfolio as a sad, ineffectual shield.

Offered the money, Frank takes out the photos and weighs them against the check. Then with a sigh of exhaustion, contemplating the fool’s crusade he’s launching, he returns the check and drops the pictures into his bag.

Very simple visual storytelling; it might have come from a 1930s movie. But this stark presentation of moral decision, given as a straightforward framing of a man’s body, achieves a measure of artistic nobility in a year that gave us Porky’s and Rocky III.

Telling it all, holding some back

Prince of the City.

It’s good to remember such moments of pictorial storytelling because Lumet’s films, especially the early ones, tend to be gabfests. If Eugene O’Neill, Tennessee Williams, and Paddy Chayefsky, along with the Method acting tradition, are your coordinates, you will be drawn to chatterboxes and blowhards. Lumet loved the spoken word, which was after all the mainstay of live TV (“illustrated radio,” it was sometimes called). It’s not clear that he ever shook the habit. His characters usually step onstage leaking exposition, announcing their pasts, their personalities, their plans, and their deepest feelings. This has the advantage of making plot premises clear, but it reduces the figures’ mystery and their ability to surprise us, or to complicate our feelings about them.

Sometimes Lumet did let story construction do heavier lifting. It happens in The Pawnbroker, because the nearly catatonic Nazerman speaks so little that the fusillade of flashbacks provides his backstory. More daringly, the large-scale back-and-fill of The Offence, peppered with small memories but also looping around the central incident in the interrogation room, seeks to reveal Sergeant Johnson’s affinities with the suspected child murderer. We need to remember Lumet’s early fondness for time-shifting plots before we declare Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead an old guy’s effort to catch up with Pulp Fiction.

Even without benefit of broken timelines, Lumet could occasionally hold back information to reshape our first impressions. Take the central revelation of Dog Day Afternoon, when cuddly Al Pacino reveals that his “wife” is not the woman he’s married to (a nice plot feint here) but the man whom he loves. This apparently sensationalistic twist comes early enough to modulate into pathos when Pacino’s character dictates his two wills.

Prince of the City realigns our sympathies in a more intricate way. At the start, Danny is presented as a tormented soul. We’re led to think that he turns snitch because of things we see: the invitation to go undercover, his brother’s and father’s angry concern that his pals are crooked, and above all the shameful efforts he makes to get drugs for his informant. Once he turns, however, he can’t limit the investigation, and at nearly the end his treachery has broken the most important ties in his life.

But “nearly the end” is the operative term, because Prince of the City boldly appends a ten-minute epilogue showing Danny being investigated himself. The Danny we saw at the film’s beginning may have been steeped in corruption; the drug bust we saw included, behind the scenes, a major ripoff of money; he has lied more than we realized; and it seems likely that he cheated on his wife with the prostitutes whom he supplied with drugs.

A modern filmmaker, or Lumet in his bodacious early mode, might have spiced these flat testimony scenes with lurid flashbacks. But sticking simply to Danny’s feeble, evasive stonewalling raises questions of his own vulnerability. Having watched him break down over years and having heroicized his suffering to a considerable degree, we have to judge him anew. Is he simply too weary to fight the charges, or has he been caught out? The ending might seem to allow for cynicism, but we can’t cast off our respect for what Danny has risked.

Further, Lumet intercuts the court scenes with government meetings about whether to prosecute Danny. In the manner of a Shavian problem play, this tactic obliges our sympathies to be clear-eyed. If The Verdict lays all its cards on the table and invites straightforward sympathy for Galvin, Prince of the City, by hiding major aspects of Danny’s character and circumstance, leads us to a more nuanced experience. The narrational dynamic of the film invites us to rethink our protagonist’s actions and decide whether to grant him mercy.