Archive for the 'Film technique: Cinematography' Category

Watching you watch THERE WILL BE BLOOD

DB here:

Today’s entry is our first guest blog. It follows naturally from the last entry on how our eyes scan and sample images. Tim Smith is a psychological researcher particularly interested in how movie viewers watch. You can follow his work on his blog Continuity Boy and his research site.

I asked Tim to develop some of his ideas for our readers, and he obliged by providing an experiment that takes off from my analysis of staging in one scene of There Will Be Blood, posted here back in 2008. The result is almost unprecedented in film studies, I think: an effort to test a critic’s analysis against measurable effects of a movie. What follows may well change the way you think about visual storytelling.

Tim’s colorful findings also suggest how research into art can benefit from merging humanistic and social-scientific inquiry. Kristin and I thank Tim for his willingness to share his work.

Tim Smith writes:

David’s previous post provided a nice introduction to eye tracking and its possible significance for understanding film viewing. Now it is my job to show you what we can do with it.

Continuity errors: How they escape us

Knowing where a viewer is looking is critical to beginning to understand how a viewer experiences a film. Only the visual information at the centre of attention can be perceived in detail and encoded in memory. Peripheral information is processed in much less detail and mostly contributes to our perception of space, movement and general categorisation and layout of a scene.

The incredibly reductive nature of visual attention explains why large changes can occur in a visual scene without our noticing. Clear examples of this are the glaring continuity errors found in some films. Lighting that changes throughout a scene, cigarettes that never burn down, and drinks that instantly refill plague films and television but we rarely notice them except on repeated or more deliberate viewing. In my PhD thesis I created a taxonomy of continuity errors in feature films and related them to various failings during pre-production, filming, and post-production.

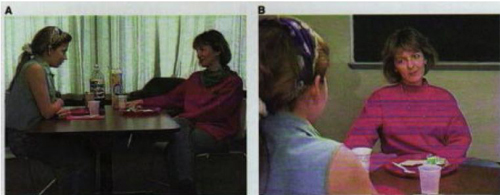

Our inability to detect continuity errors was elegantly demonstrated in a study by Dan Levin and Dan Simons. In their study continuity errors were purposefully introduced into a film sequence of two women conversing across a dinner table. If you haven’t seen it before, watch the video here before continuing, and see how many continuity errors you can spot.

Two frames from the clip used by Levin and Simons (1997). Continuity errors were deliberately inserted across cuts (e.g., the disappearing scarf), and viewers were asked after watching the video whether they noticed any.

The short clip contained nine continuity errors, such as a scarf that changed colour, then disappeared, plates that changed colour and hands that changed position. During the first viewing, viewers were told to pay close attention but were not informed about the continuity errors. When asked afterwards if they noticed anything change, only one participant reported seeing anything and that was a vague sense that the posture of the actors changed. Even during a second viewing in which they were instructed to detect changes, viewers only detected an average of 2 out of the 9 changes and tended to notice changes closest to the actors’ faces such as the scarf.

Although Levin and Simons did not record viewer eye movements, my own experiments investigating gaze behaviour during film viewing indicate that our eyes will mostly be focussed on faces and spend virtually no time on peripheral details. If you as a viewer don’t fixate a peripheral object such as the plate, you are unable to represent the colour of the plate in memory and can, therefore not detect the change in colour when you later refixate it.

Tracking gaze

To see how reductive and tightly focused our gaze is whilst watching a film, consider Paul Thomas Anderson’s There Will Be Blood (TWBB; 2007). In an earlier post, David used a scene from this film as an example of how staging can be used to direct viewer attention without the need for editing.

The scene depicts Paul Sunday describing the location of his family farm on a map to Daniel Plainview, his partner Fletcher Hamilton, and his son H.W. The entire scene is treated in a long, static shot (with a slight movement in at the beginning). Most modern film and television productions would use rapid editing and close-up shots to shift attention between the map and the characters within this scene. This frenetic style of filmmaking–which David termed intensified continuity in his book The Way Hollywood Tells It (2006)–breaks a scene down into a succession of many viewpoints, rapidly and forcefully presented to the viewer.

Intensified continuity is in stark contrast to the long-take style used in this scene from TWBB. The long-take style, which was common in the 1910s and recurred at intervals after that period, relies more on staging and compositional techniques to guide viewer attention within a prolonged shot. For example, lighting, colour, and focal depth can guide viewer attention within the frame, prioritising certain parts of the scene over others. However, even without such compositional techniques, the director can still influence viewer attention by co-opting natural biases in our attention: our sensitivity to faces, hands, and movement.

In order to see these biases in action during TWBB we need to record viewer eye movements. In a small pilot study, I recorded the eye movements of 11 adults using an Eyelink 1000 (SR Research) eyetracker. This eyetracker uses an infrared camera to accurately track the viewer’s pupil every millisecond. The movements of the pupil are then analysed to identify fixations, when the eyes are relatively still and visual processing happens; saccadic eye movements (saccades), when the eyes quickly move between locations and visual processing shuts down; smooth pursuit movements, when we process a moving object; and blinks.

Eye movements on their own can be interesting for drawing inferences about cognitive processing, but when thinking about film viewing, where a viewer looks is of most interest. As David demonstrated in his last post, analysing where a viewer looks whilst viewing a static scene, such as Repin’s painting An Unexpected Visitor, is relatively simple. The gaze of a viewer can be plotted on to the static image and the time spent looking at each region, such as a characters face or an object in the scene can be measured.

However, when the scene is moving, it is much more difficult to relate the gaze of a viewer on the screen to objects in the scene. To overcome this difficulty, my colleagues and I developed new visualisation techniques and analysis tools. These efforts were part of a large project investigating eye movement behaviour during film and TV viewing (Dynamic Images and Eye Movements, what we call the DIEM project). These techniques allow us to capture the dynamics of gaze during film viewing and display it in all its fascinating, frenetic glory.

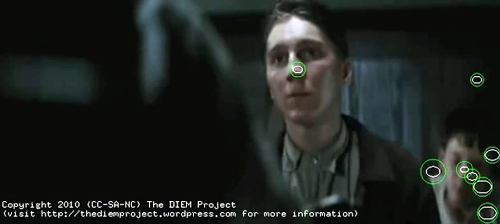

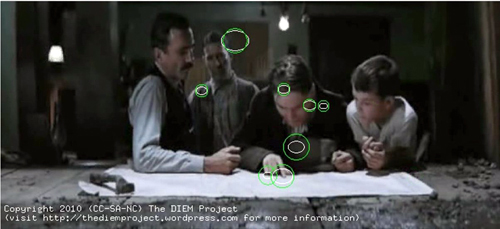

To begin, the gaze location of each viewer is placed as a point on the corresponding frame of the movie. The point is represented as a circle with the size of the circle denoting how long the eyes have remained in the same location, i.e. fixated that location. We then add the gaze location of all viewers on to the same frame. Although the viewers watched the clip at different times, plotting all viewers together allows us to look for similarities and differences between where people look and when they look there. This figure shows the gaze location of 8 viewers at one moment in the scene. (The remaining 3 viewers are blinking at this moment.)

A snapshot of gaze locations of 8 viewers whilst watching the “map” sequence from There Will Be Blood (2007). Each green circle represents the gaze location of one participant, with the size of the circle indicating how long the eyes have been in fixation (bigger equals longer).

You have a roving eye

Plotting static gaze points onto a single frame of the movie allows us to see what viewers were looking at in a particular frame, but we don’t get a true sense of how we watch movies until we animate the gaze on top of the movie as it plays back. Here is a video of the entire sequence from TWBB with superimposed gaze of 11 viewers.

You can also see it here. The main table-top map sequence we are interested begins at 3 minutes, 37 seconds.

The most striking feature of the gaze behaviour when it is animated in this way is the very fast pace at which we shift our eyes around the screen. On average, each fixation is about 300 milliseconds in duration. (A millisecond is a thousandth of a second.) Amazingly, that means that each fixation of the fovea lasts only about 1/3 of a second. These fixations are separated by even briefer saccadic eye movements, taking between 15 and 30 milliseconds!

Looking at these patterns, our gaze may appear unusually busy and erratic, but we’re moving our eyes like this every moment of our waking lives. We are not aware of the frenetic pace of our attention because we are effectively blind every time we saccade between locations. This process is known as saccadic suppression. Our visual system automatically stitches together the information encoded during each fixation to effortlessly create the perception of a constant, stable scene.

In other experiments with static scenes, my colleagues and I have shown that even if the overall scene is hidden 150milliseconds into every fixation, we are still able to move our eyes around and find a desired object. Our visual system is built to deal with such disruptions and perceive a coherent world from fragments of information encoded during each fixation.

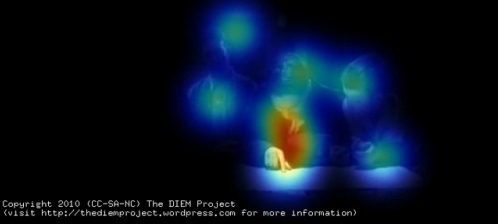

The second most striking observation you may have about the video is how coordinated the gaze of multiple viewers is. Most of the time, all viewers are looking in a similar place. This is a phenomenon I have termed Attentional Synchrony. If several viewers examine a static scene like the Repin painting discussed in David’s last post, they will look in similar places, but not at the same time. Yet as soon as the image moves, we get a high degree of attentional synchrony. Something about the dynamics of a moving scene leads to all viewers looking at the same place, at the same time.

The main factors influencing gaze can be divided into bottom-up involuntary control by the visual scene and top-down voluntary control by the viewer’s intentions, desires, and prior experience. As part of the DIEM project we were able to identify the influence of bottom-up factors on gaze during film viewing using computer vision techniques. These techniques allowed us to dissect a sequence of film into its visual constituents such as colour, brightness, edges, and motion. We found that moments of attentional synchrony can be predicted by points of motion within an otherwise static scene (i.e. motion contrast).

You can see this for yourself when you watch the gaze video. Viewers’ gazes are attracted by the sudden appearance of objects, moving hands, heads, and bodies. The greater the motion contrast between the point of motion and the static background, the more likely viewers will look at it. If there is only one point of motion at a particular moment, then all viewers will look at the motion, creating attentional synchrony.

This is a powerful technique for guiding attention through a film. But it’s of course not unique to film. Noticing points of motion is a natural bias which we have evolved by living in the real world. If we were not sensitive to peripheral motion, then the tiger in the bushes might have killed our ancestors before they had chance to pass their genes down to us.

But points of motion do not exist in film without an object executing the movement. This brings us to David’s earlier analysis of the staging of this sequence from TWBB. This might be a good time to go back and read David’s analysis before we begin testing his hypotheses with eyetracking. Is David right in predicting that, even in the absence of other compositional techniques such as lighting, camera movement, and editing, viewer attention during this sequence is tightly controlled by staging?

All together now

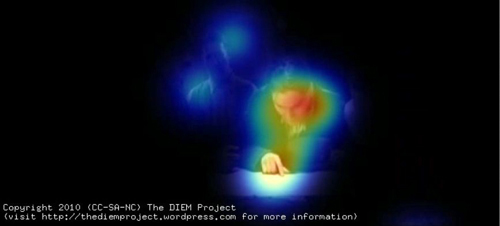

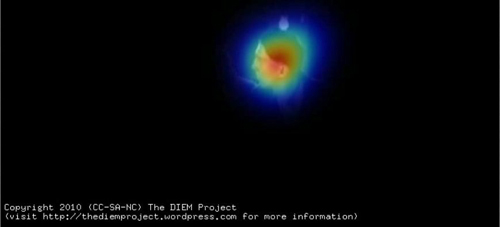

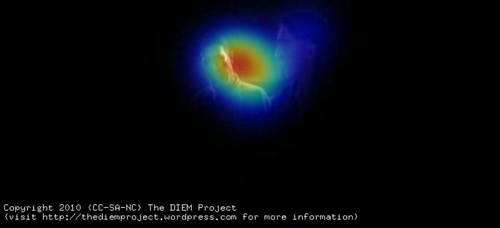

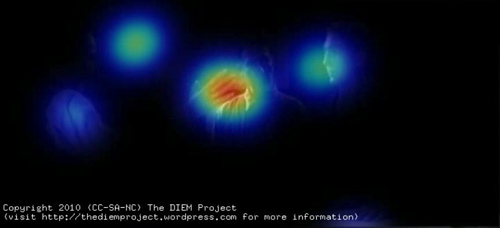

To help us test David’s hypotheses I am going to perform a little visualisation trick. Making sense of where people are looking by observing a swarm of gaze points can often be very tricky. To simplify things we can create a “peekthrough” heatmap. A virtual spotlight is cast around each gaze point. This spotlight casts a cold, blue light on the area around the gaze point. If the gazes of multiple viewers are in the same location their spotlights combine and create a hotter/redder heatmap. Areas of the frame that are unattended remain black. By then removing the gaze points but leaving the heatmap we get a “peekthrough” to the movie which allows us to clearly see which parts of the frame are at the centre of attention, which are ignored and how coordinated viewer gaze is.

Here is the resulting peekthrough video; also available here. The map sequence begins at 3:38.

Here is the image of gaze location I showed above, now matched to the same frame of the peekthrough video.

The gaze data from multiple viewers is used to create a “peekthrough” heatmap in which each gaze location shines a virtual spotlight on the film frame. Any part of the frame not attended is black, and the more viewers look in the same location, the hotter the color.

David’s first hypothesis about the map sequence is that the faces and hands of the actors command our attention. This is immediately apparent from the peekthrough video. Most gaze is focused on faces, shifting between them as the conversation switches from one character to another.

The map receives a few brief fixations at the beginning of the scene but the viewers quickly realise that it is devoid of information and spend the remainder of the scene looking at faces. The only time the map is fixated is when one of the characters gestures towards it (as above).

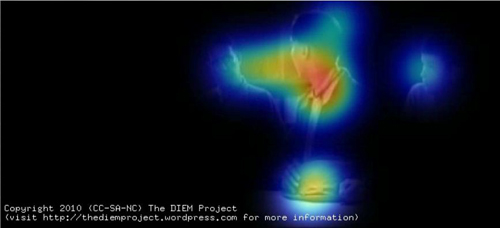

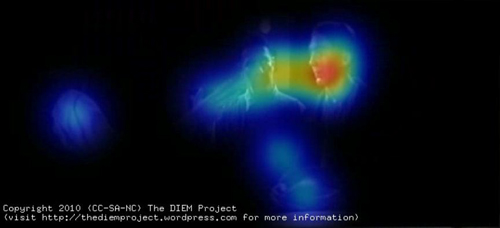

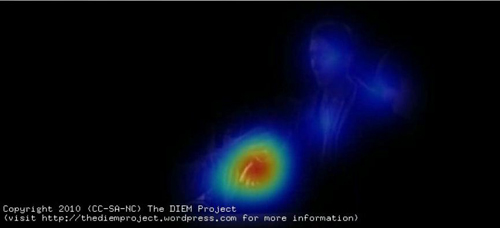

We can see the effect of turn-taking in the conversation on viewer attention by analyzing a few exchanges. The sequence begins with Paul pointing at the map and describing the location of his family farm to Daniel. Most viewers’ gazes are focused on Paul’s face as he talks, with some glances to other faces and the rest of the scene. When Paul points to the map, our gaze is channeled between his face and what he is gazing/pointing at.

Such gaze prompting and gesturing are powerful social cues for attention, directing attention along a person’s sightline to the target of their gaze or gesture. Gaze cues form the basis of a lot of editing conventions such as the match an action, shot/reverse-shot dialogue pairings, and point-of-view shots. However, in this scene gaze cuing is used in its more natural form to cue viewer attention within a single shot rather than across cuts.

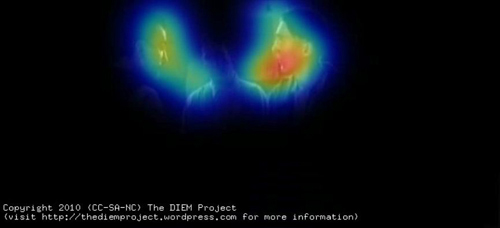

As Paul finishes giving directions, Daniel asks him a question which immediately results in all viewers shifting the gaze to Daniel’s face. Gaze then alternates between Daniel and Paul as the conversation passes between them. The viewers are both watching the speaker to see what he is saying and also monitoring the listener’s responses in the form of facial expressions and body movement.

Daniel turns his back to the camera, creating a conflict between where the viewer wants to look (Daniel’s face) and what they can see (the back of his head). As David rightly predicted, by removing the current target of our attention the probability that we attend to other parts of the scene is increased, such as H. W., who up until this point has not played a role in the interaction. Viewers begin glancing towards HW and then quickly shift their gaze to him when he asks Paul how many sisters he has.

Gaze returns to Paul as he responds.

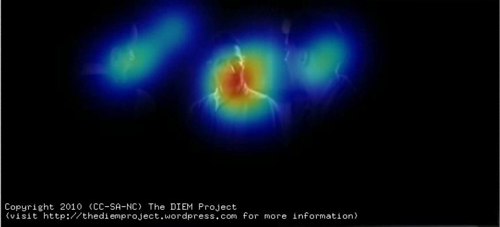

Gaze shifts from Paul to Daniel as he asks a short question, and then moves to Fletcher as he joins the conversation.

The quick exchanges of dialogue ensure that viewers only have enough time to shift their gaze to the speaker and then shift to the respondent. When gaze dwells longer on a speaker, such as during the exchange between Fletcher and Paul, there is an increase in glances away from the speaker to other parts of the scene such as the other silent faces or objects.

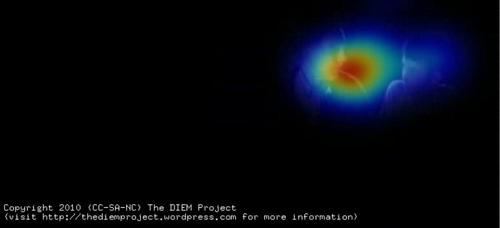

An object that receives more fixations as the scene develops is Paul’s hat, which he nervously fiddles with. At one point, when responding to Fletcher’s question about what they grow on the farm, Paul glances down at his hat. This triggers a large shift of viewer gaze, which slides down to the hat. Likewise, a subtle turn of the head creates a highly significant cue for viewers, steering them towards what Paul is looking at while also conveying his uneasiness.

The most subtle gesture of the scene comes soon after as Fletcher asks about water at the farm. Paul states that the water is generally salty and as he speaks Fletcher shifts his eyes slightly in the direction of Daniel. This subtle movement is enough to cue three of the viewers to shift their gaze to Daniel, registering their silent exchange.

This small piece of information seems critical to Daniel and Fletcher’s decision to follow up Paul’s lead, but its significance can be registered by viewers only if they happened to be fixating Fletcher at the time he glanced at Daniel. The majority of viewers are looking at Paul as he speaks and they miss the gesture. For these viewers, the significance of the statement may be lost, or they may have to deduce the significance either from their own understanding of oil prospecting or other information exchanged during the scene.

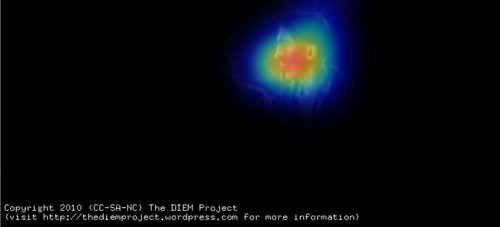

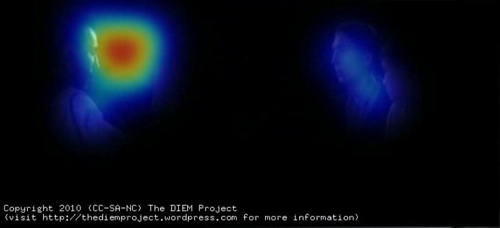

The final and most significant gesture of the scene is Daniel’s threatening raised hand. As Paul goes to leave, Daniel stalls him by raising his hand centre frame in a confusing gesture hovering midway between a menacing attack and a friendly handshake. In David’s earlier post he predicted that the hand would “command our attention.” Viewer gaze data confirm this prediction. Daniel draws all gazes to him as he abruptly states “Listen….Paul,” and lifts his hand.

Gaze then shifts quickly; the raised hand becomes a stopping off point on the way to Paul’s face. . .

. . . finally following Daniel’s hand down as he grasps Paul’s in a handshake.

We like to watch

The rapid sequence of actions clearly guide our attention around the scene: Daniel – Hand -Paul – Hand. David’s analysis of how the staging in this scene tightly controls viewer attention was spot-on and can be confirmed by eyetracking. At any one moment in the scene there is a principal action signified either by dialogue or motion. By minimising background distractions and staging the scene in a clear sequential manner using basic principles of visual attention, P. T. Anderson has created a scene which commands viewer attention as precisely as a rapidly edited sequence of close-up shots.

The benefit of using a single long shot is the illusion of volition. Viewers think they are free to look where they want but, due to the subtle influence of the director and actors, where they want to look is also where the director wants them to look. A single static long shot also creates a sense of space, clear relationship between the characters, and a calm, slow pace which is critical for the rest of the film. The same scene edited into close-ups would have left the viewer with a completely different interpretation of the scene.

I hope I’ve shown how some questions about film form, style, practice, and spectatorship can be informed by borrowing theory and methods from cognitive psychology. The techniques I have utilised in recording viewer gaze and relating it to the visual content of a film are the same methods I would use if I was conducting an experiment on a seemingly unrelated topic such as visual search. (See this paper for an example.)

The key difference is that the present analysis is exploratory and simply describes the viewing behaviour during an existing clip. What we cannot conclude from such a study is which aspects of the scene are critical for the gaze behaviour we observe. For instance, how important is the dialogue for guiding attention? To investigate the contribution of individual factors such as dialogue we need to manipulate the film and test how gaze behaviour changes when we add or remove a factor. This type of empirical manipulation is critical to furthering our understanding of film cognition and employing all of the tools cognitive psychology has to offer.

But I expect an objection. Isn’t this sort of empirical inquiry too reductive to capture the complexities of film viewing? In some respects, yes. This is what we do. Reducing complex processes down to simple, manageable, and controllable chunks is the main principle of empirical psychology. Understanding a psychological process begins with formalizing what it and its constituent parts are, and then systematically manipulating and testing their effect. If we are to understand something as complex as how we experience film we must apply the same techniques.

As in all empirical psychology the danger is always that we lose sight of the forest whilst measuring the trees. This is why the partnership between film theorists and empiricists like myself is critical. The decades of film theory, analysis, practice and intuition provide the framework and “Big Picture” to which we empiricists contribute. By sharing forces and combining perspectives, we can aid each other’s understanding of the film experience without losing sight of the majesty that drew us to cinema in the first place.

On the importance of foveal detail for memory encoding, see J. M. Findlay, Eye scanning and visual search, in The Interface of Language, Vision, and Action: Eye movements and the visual world, ed. J.M. Henderson and F. Ferreira (New York: Psychology Press, 2004), pp. 134-159. Levin and Simons’ continuity-error experiment is explained in D. T. Levin and D. J. Simons, “Failure to detect changes to attended objects in motion pictures,” Psychonomic Bulletin and Review4 (1997), pp. 501-506.

A note about our equipment and experimental procedure. We presented the film on a 21 inch CRT monitor at a distance of 90cm and a resolution of 720×328, 25fps. Eye movements were recorded using an Eyelink 1000 eyetracker and a chinrest to keep the viewer’s head still. This eye tracker consists of a bank of infrared LEDs used to illuminate the participant’s face and a high-speed infrared camera filming the face. The infrared light reflects of the face but not the pupil, creating a dark spot that the eyetracker follows. The eyetracker also detects the infrared reflecting off the outside of the eye (the cornea) which appears as a “glint”. By analysing how the glint and the centre of the pupil move as the viewer looks around the screen the eyetracker is able to calculate where the viewer is looking every millisecond.

As for the heatmaps, the greater the number of viewers, the more consistent the heatmaps. The present pilot study used gaze from only 11 viewers, which introduces a lot of noise into the visualisations. Compare the scattered nature of the gaze in the TWBB video to a similar scene visualised with the gaze of 48 viewers. We would probably see the same degree of coordination in the TWBB clip if we had used more viewers.

For a comprehensive discussion of attentional synchrony and its cause, see Mital, P.K., Smith, T. J., Hill, R. and Henderson, J. M., “Clustering of gaze during dynamic scene viewing is predicted by motion,” Cognitive Computation (in press). Social cues for attention, like shared looks, are discussed in Langton, S. R. H., Watt, R. J., & Bruce, V., “Do the eyes have it? Cues to the direction of social attention,” Trends in Cognitive Sciences 4, 2, pp. 50-59. For more on our inability to detect small discontinuities, see Smith, T. J. and Henderson, J. M., “Edit Blindness: The relationship between attention and global change blindness in dynamic scenes,” Journal of Eye Movement Research (2008) 2 (2), 6, pp. 1-17.

For further information on the Dynamic Images and Eye Movement project (DIEM) please visit http://thediemproject.wordpress.com/. This research was funded by the Leverhulme Trust (Grant Ref F/00-158/BZ) and the ESRC (RES 062-23-1092). To view more visualisations from the project visit this site. The DIEM project partners are myself, Prof. John M Henderson, Parag Mital, and Dr. Robin Hill. Gaze data and visualisation tools (CARPE: Computational and Algorithmic Representation and Processing of Eye-Movements) can also be downloaded from the website. When using or referring to any of the work from DIEM, please reference the Cognitive Computation paper cited above.

Wonderful work in this area has already been conducted by Dan Levin (Vanderbilt), Gery d’Ydewalle (Leuven), Stephan Schwan (KMRC, Tübingen), and the grandfather of the recent revival in empirical cognitive film theory, Julian Hochberg. I am indebted to their pioneering work and excited about taking this research area forward.

Finally, I would like to thank David and Kristin for inviting me to describe some of my work on their wonderful blog. I have been an avid follower of their work for years and David has been a great supporter of my research.

DB PS 26 February: The response to Tim’s blog has been astonishing and gratifying. Tens of thousands of visitors have read his essay here, and his videos have been viewed over 700,000 times on sites across the Web. I’m very happy that so many non-psychologists–scholars, critics, and filmmakers–have found something of value here. The extended discussion on Jim Emerson’s scanners site, in which I participated a little, is especially worth reading. For more comments and replies from Tim and his team, go to Tim’s Continuity Boy blogpage and the DIEM team’s Vimeo page. At Continuity Boy, Tim will post more videos based on his group’s experimental efforts.

DB PS 18 October: Tim has posted a new, equally interesting experiment on tracking non-visible (!) movement on his blogsite.

THE SOCIAL NETWORK: Faces behind Facebook

DB here:

What do John Ford, Andy Warhol, and David Fincher have in common? Eyeball these remarks.

Ford, asked what the audience should watch for in a movie: “Look at the eyes.”

Warhol: “The great stars are the ones who are doing something you can watch every second, even if it’s just a movement inside their eye.”

Fincher, on the big club scene in The Social Network: “What’s cinematic are the performances . . . . What their eyes are doing as they’re trying to grasp what the other person is telling them.”

It isn’t just cinema that makes eyes important. Eyes are felt to be significant in literature, from the highest to the lowest. In just a couple of pages of a pulp adventure story you can read these sentences:

“Then it certainly does look very mysterious,” he said, but his blue eyes were quiet and searching.

Chief Inspector Teal suddenly opened his baby-blue eyes and they were not bored or comatose or stupid, but unexpectedly clear and penetrating.

What do quiet eyes look like, actually? Or searching ones: perhaps they’re moving a bit? Bored or comatose eyes might be droopy, so let’s count the eyelids as part of the eye. But what could make eyes, by themselves, penetrating? Nonetheless, we think we understand what such sentences mean.

Watching eyes is tremendously important in our social lives. We need to monitor other people’s glances to see if they are looking at us. We need to track what else they might be looking at. We need to watch for signals sent by the eyes, particularly attitudes toward the situation we’re in. For example, we seldom look directly into each others’ eyes, as characters in movies do constantly; in real life, “mutual gaze” is intermittent and brief. But if two people stare intently at each other, we’re likely to assume keen attraction or rising aggression.

In an essay from Poetics of Cinema available on this site, I talk about mutual gaze in cinema and how it can be exploited for dramatic purposes. The same essay takes up the issue of blinking; we blink frequently, but film characters seldom do, and the actors usually make the blinks emotionally expressive (of fear, uncertainty, weakness, etc.).

The problem is that eyes, by themselves, tell us very little about what the person behind them is thinking or feeling. We can show this with a little experiment.

Do the eyes have it?

What do these eyes tell us?

Certainly they give us information–about the direction the person is looking, about a certain state of alertness. The lids aren’t lifted to suggest surprise or fear, but I think you’d agree that no specific emotion seems to emerge from the eyes alone.

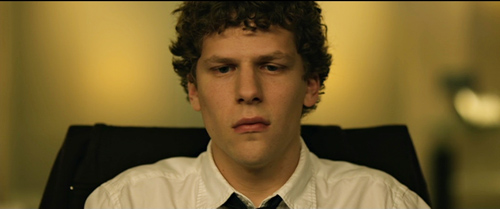

So what happens if we add eyebrows? (I’ve tipped the one above to conceal the brows; now you get to see the face’s proper angle.)

Now there’s a degree of surprise. The brows are lifted somewhat. But still the emotion seems fairly unspecific: not particularly sad or angry or distressed; probably not joyous either. Then what?

I’d call this dazed, slightly perplexed surprise. The sloping brows suggest the man is trying to figure out what’s happened; but the mouth is a slight gape. You can almost imagine the lips murmuring: “Ohhh,” or “Wow,” and not in appreciation or pleasure. If you wanted to show someone being blindsided, this is a pretty precise way to do it.

Of course context helps us a lot. Eduardo Savarin has just been gulled by his partner Mark Zuckerberg and by the interloper Sean Parker. His stock in the company that he co-founded is now worthless. So the situation informs our reading of Eduardo’s expression, and this permits the actor to underplay. Actor Andrew Garfield doesn’t give us bug-eyed surprise or frowning bafflement; he relies on our understanding of what he must be feeling (what we would feel) in order to refine and nuance his expression. When an actor underacts, we’re often expected to fill in the emotions we could plausibly imagine him to be feeling, on the basis of the story at this point. In isolation, the expression might be vague or ambiguous; the narrative situation helps sharpen it.

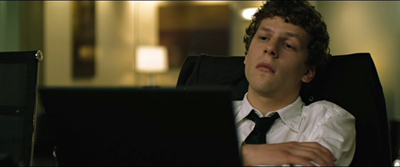

Back to the main question: How informative are the eyes alone? Try this one.

Again, I’ve tipped the shot a little to conceal the brows. Not much evident from the bare eyes, is there? Again, a certain focus and interest, but that’s about it. No marked surprise or fear or sadness.

Something has been added. The brows aren’t lifted in surprise or fear or sadness or distress; they seem to be relaxed. The angle of the look suggests concentration, but we’re not getting as much information as we got from Eduardo’s brows. We need a mouth.

The impression of concentration is greater, and I think we’d agree that this small smile of satisfaction gives us some insight into what the character is feeling. Again, the eyes tell only part of the story.

And again context matters. Mark Zuckerberg has just figured out that he can enhance The Facebook by adding users’ information about their romantic relationships. The tight, sidelong smile confirms not only his genius but also his view that college is partly about getting laid.

Less with the eyebrows

At this point you might be getting impatient with me. Isn’t this all obvious? Of course the actors use their faces–they’re paid to do that. But sometimes going obvious can get us to notice things.

For one thing, the eyes in themselves aren’t that emotionally informative. Pupil dilation can convey physical arousal, but that’s another story for another time. More commonly, the eyes give us the all-important information about what the person is looking at. The lids convey alertness, or drowsiness, or if they’re pinched a bit, concentration or anger.

Sometimes the eyes give us all the information we get. Here is Mark just before he agrees to take the job coding for the Winklevoss brothers’ project, The Harvard Connection. He moves from alertness to calculation by narrowing his eyes. As the phrase goes, you can hear the wheels turning.

Crucial to this moment is that nothing but Mark’s eyes and lids move; he doesn’t even turn his head. At the film’s climax, he will open up a little bit, and the eyelids play a central part. Getting the news that the Facebook party has been busted, Mark starts to breathe more laboriously, then wobbles his head slightly and closes his eyes. For once his concentration is broken.

It’s about as close as Mark comes to a canonical expression of sadness.

Obvious as it seems, by isolating the eyes we can notice the division of labor among eyes, eyelids, brows, and mouth: Each component supplies a bit of information. We’re remarkably skillful in integrating all these cues. What researchers into face perception call the informational triangle–the two eye regions tapering down to the mouth–creates a package of social and psychological signals. It’s this whole ensemble, the most informative parts of the face working together, that guides us in making sense of other people, or of film acting.

I’ve come to especially appreciate eyebrows. Daniel McNeill, in The Face: A Natural History, writes:

The eyebrow is the great supporting player of the face, and its work generally escapes notice. It helps signal anger, surprise, amusement, fear, helplessness, attention, and many other messages we grasp almost at once. Indeed, without eyebrows the surprise expression almost disappears. The eyebrows are such active little flagmen of mind-state it’s amazing anyone can wonder about their purpose. We use them incessantly (p. 199).

Since eyebrows are so important, actors must control them carefully. In the film’s first scene, Erica Albright moves her eyebrows vivaciously (and widens her eyelids too), but Mark’s brows are rigid and knit together.

This scene introduces us to Mark’s facial behavior. He will glance to the side when he’s pressed, but he’ll focus sharply on the other person when he’s trying to dominate the conversation. His mouth seems to be ruled by the triangularis and mentalis muscles, creating the inverted smile sometimes called the “facial shrug,” even when the lips are relaxed. Erica smiles a lot, something that usually triggers a responding smile. But not from this guy, though a smirk will occasionally flit over his mouth when he says something insulting. The closest we get to a true smile, I think, is at the blowout conclusion of the contest for internships, and that’s seen in the fairly distant long shot at the top of this section.

Above those eyes and that mouth sit those hooded brows, almost never lifting or lowering. Which is to say that Mark seldom shows surprise, and his anger will usually be visible in the set of his mouth (and in his words.) His flatlined brows sometimes suggest keen concentration, sometimes aloofness when he tilts his head back, or more pervasively the sense that everything in the vicinity is irritating. He seems to be permanently scowling, an effect that Fincher and DP Jeff Cronenweth accentuate by lighting that draws his brows closer together and hollows out the eye sockets.

How different this performance is from the actor Jesse Eisenberg’s everyday facial configuration (or at least the one he employs to send us other signals) can be seen in the making-of documentary accompanying The Social Network on DVD. One example surmounts this entry and shows a much different set of expressive cues–raised eyebrows, wider eyes, more cheerful mouth. The actor’s face is very mobile; he can even turn in the inner corners of his brows, which is hard to do voluntarily.

In one section of the making-of, Jesse reports that Fincher was often telling him, “Less with the eyebrows,” and onscreen Eisenberg delivered. By the end, for the last shots of Mark alone, Fincher asked for what’s become famous as the Queen Christina effect–an expression that could be read in many ways. “I want everybody to put anything on it.”

The result is a portrait of Generation Whatever, or an image of stoic loneliness, or of bemused curiosity about an old girlfriend, or. . . .

One more consequence of my noting the obvious: The centrality of faces to modern movies. Today’s films use close-ups very heavily, probably more than at any other point in film history. (The Way Hollywood Tells It explores some reasons why.) What I’ve called the “intensified continuity” style of modern cinema relies on tight single shots of individual players.

So modern players must be maestros of their facial muscles and eye movements. In other styles of filmmaking, currently and historically, the actor’s performance is projected onto more body parts through gestures, stance, gait, and the like. Recall Cary Grant, who performed with his whole body. Of course he wasn’t bad in close-ups either.

Faces aren’t everything in movies like The Social Network. Most characters use their arms and hands freely–probably the Winklevi the most. Mark is straightjacketed, but even he will gesture sometimes, as when a drooping Twizzler becomes his hand prop. He usually prefers a shrug, though it’s executed without the eyebrow lift most people add. Postures and personal walking styles play key roles in the film as well.

Still, as in most movies today, here eyes and brows and mouths are the main channels of emotional information. Fincher again: “It was really a movie about kids’ faces.” And even films from the 1910s, made before directors used a lot of cutting, often used long-shot staging to direct attention to the body’s most informative zones. A 1913 book on film acting noted, “Facial expression is perhaps the most important part of photoplaying. . . . After all is said and done the eyes are really the focus of one’s personality in photoplaying.”

Facebook facework

I can’t offer a complete account of nonverbal behavior in The Social Network here, but I want to end with a hypothesis that would be worth more detailed inquiry. The film’s central relationship is that between über-nerd Mark and Econ-major Eduardo, the coder and the aspiring tycoon (although he also supplies Mark with a crucial algorithm). Through facework, Fincher and his actors delineate the contrasting personalities and trace their shifting dynamic.

From the start, we get Mark’s stare of frowning concentration, drawing on the muscle called the corrugator, Darwin’s “muscle of difficulty.” By contrast, Andrew Garfield’s performance is marked by a look of worry and abashment. He’s often kinking his eyebrows, furrowing his brow, and ducking his head. Fincher motivates this behavior by having him often stoop over Mark’s workstation, tilt his head downward, and lift his eyes from underneath his brow.

In this shot/ reverse-shot passage, Mark’s mask never slips but Eduardo, wrinkling his brow and tipping his chin down a bit, looks apologetic.

Even when Eduardo has every right to berate Mark, he looks like he’s the one in the wrong. Instead of displaying the jammed-down, pinched-together brows of an angry man, he won’t lose his patient, slightly anxious look.

See the last image on this entry for a moment when Eduardo seems on the verge of tears–and this is after he’s gotten an invitation to join two alluring women.

You can argue that the blindsided expression we dissected earlier is one culmination of the facial cues that Andrew Garfield has been blending in the course of the film. But things are more complicated. The plot gives us two forward-moving timelines, one in the past tracing the rise of Facebook, the other in the present, during which Mark is deposed in two lawsuits. At an early deposition, Mark’s implacable stare works to make Eduardo revert to his old obeisance.

But in a climactic face-off, we come to see a different Eduardo.

Eduardo’s quiet testimony about whether anyone’s share but his was diluted (“It wasn’t”) affects Mark more deeply than the bluster of the Winklevoss brothers. The words are delivered without the usual sidelong glance, kinked eyebrows, or head ducking that has defined Eduardo earlier. His brow is smooth, his brows level. This is man to man, and it’s Mark who breaks off eye contact.

You could nuance this transformation by tracing it scene by scene, and contrasting it with the body language displayed by other characters. For today I simply wanted to sketch the broad development that I think is at work in this core relationship. The drama of domination and betrayal is played out in eyes, eyebrows, mouths, mutual gazes, and the like as much as it is in the dialogue and incidents.

There is no art, Shakespeare’s Duncan says, to read the mind’s construction in the face. He’s right about the reading part; we grasp expressions fast, intuitively, and often reliably. But there is art in the performer’s construction of the face, and of the director’s cinematic shaping of it.

John Ford’s remark about looking at the eyes is quoted in Joseph McBride’s Searching for John Ford (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2010), p.2; the Warhol quotation comes from Andy Warhol and Pat Hackett, POPism: The Warhol ’60s (New York: Harper and Row, 1980), p. 109; quotations from David Fincher come from the bonus features on the collector’s edition DVD of The Social Network. My quotations about eyes in fiction are drawn from Leslie Charteris, Prelude for War (New York: Doubleday, Doran, 1938), pp. 171, 173. The 1913 quotation about eyes comes from Francis Agnew’s Motion Picture Acting (Syracuse: Reliance Newspaper Syndicate), p. 40; I learned of it from Janet Staiger’s article, “‘The Eyes Are Really the Focus’: Photoplay Acting and Film Form and Style,” Wide Angle 6, 4 (1985), pp. 14-23.

Ed Tan offers a very good analysis of the issues I mention here in his article “Three Views of Facial Expression and Its Understanding in the Cinema,” in Moving Image Theory: Ecological Considerations, ed. Joseph D. Anderson and Barbara Fisher Anderson (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2005), pp. 107-127. I find Vicki Bruce and Andy Young’s In the Eye of the Beholder: The Science of Face Perception (Oxford University Press, 1998) a very helpful guide to ideas in this research area. The “facial shrug” is described in Gary Faigin’s excellent The Artist’s Complete Guide to Facial Expression (New York: Watson-Guptill, 1990), pp. 104-105.

There’s a fascinating debate in the human sciences about whether particular aspects of nonverbal communication are constant across cultures. Gestures vary considerably, but are facial expressions universal to some degree? Or do they differ from culture to culture? Are they primarily expressions of the person’s emotion, or are they signals which have developed, through evolution or cultural convention, to influence others? You can read more about these and other issues in Paul Ekman and Wallace V. Friesen, Unmasking the Face (Cambridge, MA: Maor Books, 2003) and Alan J. Fridlund, Human Facial Expression: An Evolutionary View (San Diego: Academic Press, 1994). The classic account is by Darwin, whose 1872 book Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals is available in an edition in which Ekman includes an afterword explaining the development of this research tradition.

Up to the minute, more or less: Contemporary research on smiling and eye contact.

PS 2 February: Thanks to William Flesch for correcting my Shakespeare citation: I originally attributed it to Hamlet.

Direction: Come in and sit down

Tampopo (1985).

There is what we call the Hollywood Style. . . . . Master shot [filmed] from the very beginning [of the scene] to the end, then a close shot from beginning to end, then from angles A and B, cutaways, et cetera. Then all of the materials are assembled later in the editing room. But in Japan, the editing plan is prepared before shooting. When you cut, it’s a matter of trimming heads and tails and just putting it together. Three days after the end of filming, there is a rough cut of the film.

Itami Juzo (The Funeral, A Taxing Woman).

DB here:

Planet Hong Kong 2 still on the way…. very close to ready…. deciding among cover designs…. soon; sooner if possible….

In the meantime, some creative choices involved in directing a simple scene.

Shanghai’d

What could be easier than getting a man into a room and sitting him down? The opening scene of Shanghai (2010) seems to me to bungle this basic piece of tradecraft.

In the image above, journalist and spy Paul Soames is being beaten up by the minions of Captain Tanaka. Who’s the poor sod who has to hang those big flags so high in movie torture chambers like this? Anyhow, soon the torturers drag Soames up the stairs, likewise in long shot, to meet the captain.

A brief shot of a door opening seems to put us in Soames’ shoes. But that viewpoint isn’t carried through consistently: we cut abruptly to the other side of the door, to a long-lens medium shot of Tanaka opening it.

Soames steps forward and is greeted by Tanaka.

Now comes the establishing shot, from quite far away, as Soames walks to the desk. This shot is interrupted by cutting back to the shot of Soames moving forward.

As the shot continues, Soames sits down and looks up. Throughout the scene, this setup will be assigned to cover Soames, with the camera panning and reframing as necessary.

Counting the swinging-door shot, it has taken four shots to get Soames into the room. But the actors aren’t yet fully in place. As Soames turns his head, Tanaka (back to master shot) moves around on Soames’ left side. The phone starts ringing.

Tanaka begins to halt at his desk, but before he stops moving we cut again to Soames, whose attention has shifted to the phone. He has asked that his embassy be notified, and now he suggests that it’s the embassy calling.

Cut to a close-up of the telephone, the object of Soames’ attention, and another shot of Soames, as before, as he looks expectantly back at Tanaka.

Now we have a closer shot of Tanaka, still slightly moving, and we catch his disdainful expression.

After Tanaka lifts and drops the receiver to cut off the call (another close-up), he settles into place. The rest of the conversation is played out in those loose over-the-shoulder shots that modern directors like so much.

Throughout, the shots of Soames seem to be from the same camera setup as when he entered. No repositioning of the camera marks stages of his part in the conversation, though at the end of the scene a pair of close-ups shows Tanaka asking, “Where is she, Mr. Soames?” Cue the flashback.

It’s not just that it took director Mikael Håfström over a dozen shots to get Soames and Tanaka into position for their central duet. Hitchcock might use several shots too. But each of his would be calibrated for specific expressive effects, such as subjective point-of-view treatment or a striking composition. Instead, the Shanghai shots exemplify a fairly casual cover-everything approach–a scattergun version of what Itami called the Hollywood Style.

Here the individual shots make a big deal out of a simple piece of business. We don’t need to see all of Tanaka’s office (since the rest of the space never gets used in the scene), and it doesn’t need to be so vast in the first place (except to announce that this is an expensive movie). The long-lens camera setup that lets Soames advance into the room and sit exists solely to let us watch the actor act, and it provides awkward cuts when bits of it are embedded in extreme long-shots.

It’s not hard to imagine alternatives. A straightforward tracking back from Soames as he enters and sits, framed from further away, would have kept both him and Tanaka in the frame. This framing could have easily shown Tanaka coming around to take up a position in the foreground by the desk, perhaps turned partly toward us so that we could peg him as a major character. Then if you insist on a cutaway to the ringing telephone, it would have had more impact, interrupting a sustained shot and contrasting to the fuller frame showing the two men.

Today many directors believe that we must always see the face of the person who’s speaking. So we get lots of shots, mostly singles, one per line, and each face is usually in close-up or medium-shot. Hence the great number of cuts per scene; here, counting from the swinging door, we get 23 shots in 97 seconds. And hence the repetitive reverse shots that cover the conversation.

I’m not the only one who notices these things. “If I see another over-the-shoulder shot,” says Steven Soderbergh, “I’m going to blow my brains out.”

Television probably has a lot to do with the emergence of this style, as some historians, me included, have argued. You have to be a good director to overcome the choppiness inherent in this manner of filming. I don’t think that Hafstrom did that. If the director had planned his shots in the finer-grained way Itami indicates, we might have had more visual variety, along with compositions and cutting that take us beyond the actors’ faces and line readings.

Dandelion soup

Now we might look at how Itami does it. An early scene of Tampopo (1985) also demands that a man, along with his sidekick, come into a room and sit down. We see Goro the trucker and his pal Gun enter the noodle shop, along with the little boy they’ve found lying on the street. We see them first from outside and then from inside the new locale, much as in our Shanghai example. But there’s no need for anything like that insert of the opening door.

Cut to a point-of-view shot that makes a point: Goro is entering a room full of thugs. Itami pans to show two knots of men in the shop, some of them threatening.

While each Shanghai shot does one thing at a time, this shot does two things at once. This shot sets up the hostilities that will ensue, while also laying out the space of the shop and positioning all Gun’s adversaries in it, along with the proprietress Tampopo.

Cut back to the men at the door, but it’s a different framing, from further back, than we saw initially. Now some of the thugs are staring at our heroes.

Itami is calibrating his compositions to give us new information. If this composition had been used for the first shot of the men entering, the subjective pan across the room wouldn’t have been so surprising. Now the camera cranes back to follow Goro and Gun striding to the middle of the shop and sitting down. They order bowls of noodles.

This orientation will be the dominant one in the course of the scene. But the space isn’t as bare as in the Shanghai scene; the men we see dotted around the room will play important roles in the action now and later. As in the Shanghai scene, there are cuts to close-ups, but they show more informative items than a ringing telephone. One shot picks out Tampopo herself (establishing her as a major character), another picks out Gun’s skeptical view of her cooking technique, and a third tilts down to show her hands cooking noodles in water not yet boiling.

To the noodle connoisseur Gun, this proves that she’s a maladroit cook, and another shot of the two men shows his reaction.

Cut to a long-shot. The long-shots of the office in Shanghai are always from a single position (the result of straight-through master-shot coverage), but here we get a slightly different framing than we’d seen earlier. The camera is somewhat lower, which allows Itami to stage a little piece of business. Tampopo’s son Tabo runs unseen out from behind the young thugs, along the aisle behind the stools, into the foreground, and out frame right. He has been beaten up outside, but Tampopo takes it in stride.

When Tabo has gone, the men resettle in for the next phase of the scene, when Tampopo serves Goro and Gun. The entire shot we’ve just seen is held for forty-one seconds. Soon a fight will erupt, delaying the revelation of how awful Tampopo’s noodles are.

This is not virtuoso direction, but it is smooth and precise. Each shot blends with the next with a degree of care we don’t get in the Shanghai instance. That’s partly because each shot is given its own small, completed arc of action. (The nine shots I’ve listed run ninety seconds.) For example, Tabo’s run down the aisle is prepared by a slight shift in Goro’s glance at the end of an earlier shot I’ve mentioned. He looks toward the door and tells Tabo he’ll catch cold.

This moment prepares us for the next bit of action, while also setting up the trucker’s gruff concern for the boy, an important element of the plot to come.

More generally, across the whole scene each long shot does more than simply orient us or cover changes in position; it’s enlivened by movement and incident. Nothing in the Shanghai scene approximates Itami’s willingness to let body language replace facial close-ups. Here Goro coolly samples the noodles while the gang prepares to rumble.

Later, an entire scene will be played in a packed long shot lasting nearly a minute. Goro has brought Tampopo to watch a master chef at work, and Itami is perfectly okay with concealing her face as she calls off all the orders that people have just made. We don’t need a close-up of her expression when she speaks; the important thing is her aptitude and the customers’ enthusiastic applause.

An unassertive shot like this, you want to say, respects the audience by letting us see everything that matters at each moment. We call it directing a movie.

Itami’s remarks in our epigraph come from Bob Strauss, “Director Juzo Itami,” Premiere (June 1988), p. 25. Soderbergh’s comment about OTS shots is taken from “Matt Damon: Steven Soderbergh really does plan to retire from filmmaking,” at the Los Angeles Times.

Shanghai has probably not come to a theatre near you. Delayed during the shooting, it sat on the shelf for some time before its premiere last summer in China. It’s announced for U. S. release in 2011 but the Weinstein company website says only that it’s “coming soon.” Planet Hong Kong redux will beat it, for sure.

As chance would have it, Tanaka in Shanghai and Gun in Tampopo are both played by Watanabe Ken.

My arguments about the emergence of this “intensified” version of classical continuity are made in The Way Hollywood Tells It, pp. 117-189. I’ve done a blog on the idea here; it’s hardly fair for me to compare Nora Ephron with Lubitsch, but she sort of asked for it. For more on economical staging and cutting, see our entry on Spielberg’s shooting style, as well as the idea of the Cross. For another comparison of Hollywood direction with an Asian alternative, see our entry on Jackie Chan’s Police Story.

A. D. Jameson makes strong points about inefficient shot breakdown in his essay “Seventeen Ways of Criticizing Inception.” Jameson invokes The Ghost Writer as a good counterexample, and indeed Polanski’s film often displays the sort of cut-to-cut restraint and control that Itami calls for. Jameson elaborates further in another epic post. There’s also an intriguing discussion at Jim Emerson’s Scanners blog of how much a filmmaker should rely on close-ups; the film at hand is Black Swan.

P.S. 5 January 2010: We’ve had an enthusiastic response to this entry; thank you, Twitterers. It occurred to me that readers might be interested in a similar comparison between Asian filmmaking and U.S. practice in a very early entry, back in 2006. Ironically, Soderbergh’s Good German was involved, the subject of an earlier post. The contrast case was Johnnie To’s PTU.

Shanghai (2010).

Ratio-cination

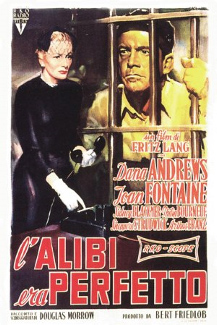

Beyond a Reasonable Doubt.

DB here:

Good timing. Just as I was about to enable more aspect-ratio fetishism, I got news of the publication of Widescreen Worldwide, from John Libbey. Edited by John Belton, Sheldon Hall, and Steve Neale, it has its distant origins in a 2003 conference at the National Media Museum in Bradford, England. Widescreen Worldwide will be a very useful volume, with material on little-studied U. S. systems and a lot of information on formats in Japan, France, Italy, and Russia, even Norway.  Most studies of widescreen technology seldom discuss the creative uses to which it was put. But this collection features several essays focusing on the artistry of the wide formats, emphasizing the work of Preminger, Peckinpah, Okamoto, Suzuki, et al. As the publisher’s blurb puts it:

Most studies of widescreen technology seldom discuss the creative uses to which it was put. But this collection features several essays focusing on the artistry of the wide formats, emphasizing the work of Preminger, Peckinpah, Okamoto, Suzuki, et al. As the publisher’s blurb puts it:

The book documents how the aesthetic strategies explored during the first wave of American widescreen films underwent revision in Europe and Asia as filmmakers brought their own idiolect to the language of widescreen mise-en-scène, editing, and sound practices. As a global phenomenon, widescreen cinema thus presents the opportunity to examine how different cultures appropriate the technology to advance extremely different cultural and aesthetic agendas.

I have an essay included on the Shaw Brothers directors, and I’m happy to be in such distinguished company in this major publication. My essay is available on this site. The paper I gave at the conference, on Hou Hsiao-hsien’s early anamorphic films, is also posted here.

Speaking of widescreen: Today, we go back to While the City Sleeps and SuperScope, thanks to some correspondents and further fooling around on my part.

Ratio decidendi

The story so far: SuperScope was a widescreen system devised by Irving and Joseph Tushinsky for RKO . It extracted a wide image from the 1.37 standard frame and printed it as a squeezed anamorphic frame, to be unsqueezed at a ratio of 2.0 to 1. (A later version allowed for a 2.35 stretch.) In principle, it’s an early version of what Super 35 does now. Some RKO films, notably Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956), were shot in knowledge that they would be given the SuperScope treatment; others were SuperScoped after the fact.

The question before the jury was: Do SuperScope prints of Lang’s While the City Sleep (1956) faithfully reflect his intentions? The answer I settled on was: Probably not. A Variety story indicated that the SuperScope prints were made for European distribution, though perhaps some sneaked into the US theatrical market or the 16mm aftermarket.

Now for a little more on Lang’s compositions. Several viewers have commented on all the headroom visible in the full frame. The ‘Scope print I examined displayed some as well, but not as much, as my illustrations for the earlier entry indicate. More likely the film was masked in the US to something like 1.66 or 1.75. I reproduced some frames from a 1.75 laserdisc version, and they look reasonably good. Overall, I suggested that City’s fairly open compositions suggest that Lang was expecting the film to be masked somewhat in projection, but not to the full 2.0:1 ratio we get with SuperScope.

Although for most of its length, While the City Sleeps seems quite okay at 2.0, I found one shot that would be quite awkward in full SuperScope. Alas, I didn’t photograph it from the 35mm European print I examined, but I’ve used my stills from the print to guide my cropping of the 1.37 frame in this instance. The results are, as the lawyers say, probative.

The scene is mundane: Walter Kyle gets a phone call from his errant wife Dorothy. She’s carrying on an affair with Harry, the art director of the newspaper Walter runs. Walter talks with her, and Lang cuts to her responding. I show you the 1.75 versions.

When Lang cuts back to Walter, he provides a new camera setup featuring the butler Steven. This is to prepare us for a joke: Walter says he’ll have Steven meet Dorothy at the front door in his underwear. Steven reacts with embarrassment. Given that a lot of the film plays on the sexual rapacity of men, the humor is a shade sick.

A narrative convention: The stuffy, puritanical butler. But notice that in the 1.75 frame, Steven’s full face is quite visible. Of course it’s even more visible in the full-frame version. (Fussy Lang, or fussy somebody, seems to have aligned the face with the swoop of the ceiling.)

But the composition would look more awkward if chopped in the SuperScope 2.0:1 version. Here’s one framing, using the cropping points typical of other anamorphic shots in the European 35mm print.

In addition, since the crop slices more off the bottom region than the top, Walter’s body is also lost in the anamorphic version. But this is still probably the best compromise. Some frames in the 35mm S’Scope version favor the lower region of the original shot. But in this shot that option would be disastrous.

It’s hard to imagine that the director of the painstakingly composed Moonfleet (1955) would have wanted to saw Steven’s skull in half.

Mors ultima ratio

So Lang didn’t shoot the film expecting it to be SuperScoped. Nevertheless, things that escape directors’ intentions can have their own impact on viewers. In the codicil to the earlier blog entry, I wondered if French critics’ admiration for While the City Sleeps might have been based on their seeing wider prints than Americans did—in effect, gathering Lang into the cohort of skilled anamorphic filmmakers that included Ray, Preminger, Minnelli, et al. Samuel Bréan wrote to tell me that one critic, Jacques Lourcelles, raised this issue explicitly. Lourcelles writes:

For both this film and Lang’s next film, Beyond a Reasonable Doubt, the format poses a thorny problem that can be resolved only by considering aesthetic matters. The film, not shot in CinemaScope, was exhibited in Superscope (a wide format used at RKO and created through laboratory processes), and then in a normal format. Which is better? In my opinion, the wider one. Only there, for instance, do the camera movements and the newspaper-office set have their true impact. Even if the Superscope version was “manufactured” in the lab, Lang knew that the film would be seen on the wide screen and his direction was conceived as a function of that. The same goes for Beyond a Reasonable Doubt; to cite just one instance, the first sequence showing the condemned man walking toward the electric chair is obviously conceived for the wider format.

This does lead to some intriguing speculation on how “misreadings” of films can have positive consequences. The French celebration of Lang’s 1950s films led American and British critics to reevaluate them.

The case of Beyond a Reasonable Doubt is quite parallel to that of While the City Sleeps. Released in September 1956, it too was reviewed in Variety as a non-anamorphic picture. Its U. S. publicity makes no reference to a widescreen format. But its overseas posters claim that it is in “RKO-Scope.” Huh?

By the end of 1956, the Tushinskys had split from RKO and were selling SuperScope generally. So in November 1956 RKO simply announced that it had developed “a new widescreen, anamorphic process” that would carry a ratio of 2.0:1. Historians of widescreen have assumed that this is SuperScope by another name. The same publicity announced that soon all the studio’s films would be in RKO-Scope. But RKO ceased making movies on 1 January 1957. Universal took over distributing the remaining pictures.

Again, on the basis of the posters and Lourcelles’ comments we can be confident that Beyond a Reasonable Doubt was shown in a 2.0:1 aspect ratio in some overseas markets. As airless a movie as Lang ever made, with disconcertingly generic sets and severe framings and camera movements, it engendered a fascination in French critics. The story itself is a model of Langian guilty conscience. A reporter looking for a new book to write agrees to a hoax that will attack capital punishment. He’ll plant clues indicating that he’s a murderer in order to prove that an innocent man can be convicted. Lang’s narration offers his customary feints and ellipses. Smooth hooks, verbal and visual, carry us across scenes. Casual details are dropped in, or a sudden cutaway appears, and we’re misled into thinking we’re ahead of the plot. We are in fact behind it. Crucial story information is skipped over, but we’re not aware of what has been deleted until much later. We should have noticed.

Appearing in the same year as Around the World in 80 Days, The King and I, Lust for Life, Giant, Anastasia, War and Peace, and other sweeping spectacles, Beyond a Reasonable Doubt was a bare-bones programmer. Lang’s last American film doesn’t waste its energy on the pictorial flourishes of budget-strapped directors like Siegel or Fuller. Other B-films could whip up visual flair with chiaroscuro, close-ups, and fast cutting, but Lang’s images seem disconcertingly banal; yet their simplicity gives them an odd purity. In an influential review, Jacques Rivette declared that Lang was, in effect, filming concepts.

I don’t find any shots in Beyond with a vertical bias comparable to the shot featuring Steven the butler in City. The 1.37 frame shots are very empty up top. So here’s an experiment in reconstructing an approximation of what Europeans saw.

Dux vitae ratio

As I suggested in the earlier blog, for decades Lang composed his frames carefully, balancing figures in dynamic patterns and sometimes putting important elements along the sides or in a corner. Here are some examples from one of his most beautiful films, The Ministry of Fear. He likes triangular compositions that tuck heads into corners, as well as camera angles that let foreground items anchor the faces and bodies.

When the frame is unbalanced, it’s for a reason, such as purse-rifling.

A director so committed (like Ozu) to putting heads high in the shot must have felt annoyed when he had to hang inexpressive space over his players, as in the shot at the very top of today’s entry. When he left headroom in earlier films, it served an exacting compositional purpose, as you see below. Those wedge-formations of tapers, backing up threatening cobras, look back to the decor of his German films.

I suspect that it pained him to accept the more open framing demanded by non-anamorphic ratios. In CinemaScope you could count, more or less, on the proportions of your image being respected. But shooting flat, could you really be sure what would stay in the shot? Projectionists could mask it to 1.66, 1.75, 1.85, and even wider. These ratios were so imprecise, and this is one precise director. Lang “shot to protect,” as they say, but he couldn’t protect what was already gone: his compact, quietly masterful compositions.

John Belton wrote to me to echo the idea that Lang would probably have realized that While the City Sleeps would be cropped to as much as 1.75.

Certainly every director after 1954 composed for wide screen projection. As for SuperScope, why didn’t they just project it flat with a 2:1 matte in the aperture? It certainly would have looked sharper. Maybe the answer lies in the relative abundance of CinemaScope installations overseas?

Good question for further research. Another interesting sidelight: Who was the SuperScope representative for Europe? For a time, apparently none other than Edgar G. Ulmer! Ulmer is identified as a SuperScope representative in “Tushinsky’s Teuton Deal,” Variety, 7 September 1956, p. 5. Michael Campi wrote to inform me that in Australia he too saw a 2.0:1 print of While the City Sleeps.

RKO’s announcement of RKO-Scope can be found in “And Now–RKO-Scope,” Variety, 30 November 1956, p. 1. More background on the winding down of the studio is provided in Richard B. Jewell and Vernon Harbin, The RKO Story (London: Octopus, 1982), pp. 242-245.

The Jacques Lourcelles comment appears in his Dictionnaire du cinéma vol. 3 (Paris: Laffont, 1992), p. 294. I’m grateful to Samuel Bréan for calling my attention to it. Rivette’s 1957 essay on Beyond a Reasonable Doubt, “The Hand,” is available in Cahiers du cinéma: The 1950s: Neo-Realism, Hollywood, New Wave, ed. Jim Hillier (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1985), pp. 140-144. It has been included in a site devoted to Jacques Rivette, Order of the Exile. (The hand Rivette refers to is that in the shot of the warrant above; had Rivette not seen the RKO-Scope print, he might have had to title the essay, “The Hands.”) The poster images for Beyond a Reasonable Doubt come from the ever-generous DVD Beaver, and its review of a Spanish disc.

The Ministry of Fear.