Archive for the 'Film technique: Cinematography' Category

Back to the vaults, and over the edge

Unstoppable? Not really. The Juggernaut (1915).

DB here:

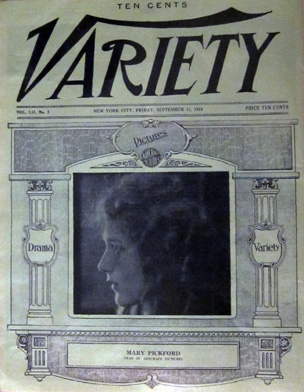

A few weeks ago, I praised Variety for making its back issues available digitally. The result is a magnificent vault of information. I also expressed frustration that the recent makeover of The Hollywood Reporter neglected to offer access to its original online archive, which indexed issues across the last twenty years. On the last point, some news.

First, my inquiry to the address listed on the HR website eventually yielded this blue note.

Good Morning,

We apologize for the delayed response.

I do not think there is a way to go back to prior to the changeover.

You would need to contact the publisher about that, as we do not handle the website directly.

Here is a phone number for you 323-525-2150.

Thank you.

I called the number, which handles only subscriptions, and the person answering had no idea what I was asking about.

But all is not lost. My first efforts to access the archive turned up very little for 2010, but shortly afterward I was able to access items from most of this year. Now, if you type a search term into the Search box of the HR site, it brings up items from as far back as 2008. This is an improvement over earlier attempts I made. It seems that THR is gradually adding old material to their archive, in reverse order.

Unfortunately, the search mechanism is quite indiscriminate. Searching “Johnnie To,” with and without quotation marks, yielded 290 hits, but I could find no articles about Johnnie To. Instead, the items with highest relevancy concerned Johnny Depp, Johnny English, John McCain, and the new Narnia movie.

The best news of all came from alert reader David Fristrom of Boston University. He advises me that the old HR archives are still available through LexisNexis. So I tried there with Johnnie To, and I got 338 references, stretching back to 1992. The ones at the top of the relevancy scale were indeed about Mr. To, including a Cannes piece called “Fest’s Red Carpet Flows with Blood.”

Accessing the archive isn’t straightforward, but you don’t need a subscription to HR if your library has purchased access to LexisNexis. I append David’s instructions at the end of this entry. Thanks to him for sorting this out for me.

Now, back into the Variety vaults.

This one’s a real train wreck

On 12 March 1915, Variety reviewed The Birth of a Nation. Alongside that review sits one of The Juggernaut, a Vitagraph feature directed by Ralph Ince. The reviewer, “Simc.,” dwells almost entirely on what he calls “the train-through-the-bridge thing.” The producers bought an old locomotive and some passenger cars, built a flimsy bridge, and ran their train off into what appeared to be a river.

The review exhibits some Variety touches that are still with us. Take the (quite reasonable) idea that nearly every movie is too long. “If this five-reeler were cut down to three reels, which could easily be done, the Vitagraph would have a real thriller.” There’s also the notion that people who come to the see the movie should be aware of its main attraction. “If the audience knows a train will go through a bridge at the finish, it won’t mind the fiddling about in the first four reels before that scene is reached. But if the audience doesn’t know what is to come, there may be many walk-outs.” At the beginning of Unstoppable we’ll sit through all the union and non-union wrangling and alpha-male preening if we’re sure we’re going to see a train that is certifiably unstoppable, except that it’s likely to be stopped by our heroes.

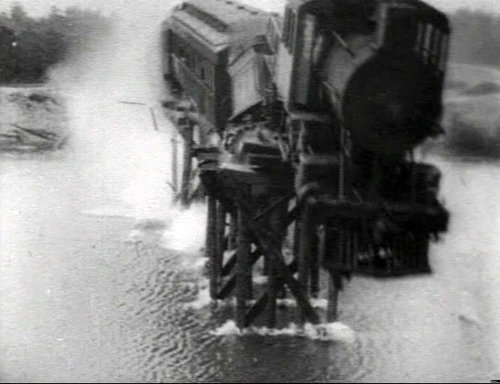

The Juggernaut does give us a pretty spectacular train wreck, as you see above. The entire film may not survive, but we have a version of the last reel (perhaps because a collector thought it worth saving). Train or no train, the film is of interest in showing what Griffith’s rivals were up to.

The plot centers on a crooked railroad magnate, Philip Hardin, and his college friend John Ballard. In the reel we have, Hardin’s daughter Louise, who loves John, sets out on an errand. When her car stalls she boards an express train. A track-walker finds worn ties on a bridge and warns the company, but too late. As Hardin races to stop Louise’s train, it arrives at the bridge and he watches it topple into the water. The sight kills him on the spot. John arrives and swims out to rescue Louise.

That’s when things get dicey. According to the Variety review and other sources, Louise dies in the wreck. Simc again:

The leading woman of the film, Anita Stewart, is discovered dead, lying against one of the windows, with particular pains taken that her features shall be clearly visible. . . . Anita is carried to shore and lain alongside of her father, who had died of heart failure (on land) a few moments before.

In the version available on DVD, John does bring her body ashore, but she revives, lifts herself up, and embraces him. The print ends there. Why the varying ending? Perhaps this is a version made at the time for a different market or in response to censorship, or it might be a rerelease using alternative footage. Or perhaps the press reviews were based on a synopsis supplied by Vitagraph, and the studio made modifications in the print before release.

The Juggernaut is also intriguing stylistically. By this point, crosscutting and scene analysis were common techniques in U. S. films. To set up the perilous situation, the cutting alternates shots of the track-walker, of Hardin, and of Louise. Once Hardin discovers that Louise is on the train headed for the dilapidated trestle, we are set up for a last-minute rescue–which fails. A particularly interesting series of shots shows Hardin’s trajectory converging with the train’s path. Riding in a power boat, Hardin looks back and we get a shot of the train in the distance, suggesting that he can see it.

From this we cut to a shot of Louise, confirming that she’s on board and showing her innocent lack of awareness. Then we get a repeated framing of the train rushing toward the bridge.

After another long shot of the train, we get a shot of Hardin in his powerboat with the train whizzing by in the background. This confirms that he was indeed watching it approach off screen left in the earlier shot, and it shows that he isn’t likely to catch up.

Once the train has toppled into the stream, there are some striking shots of people trapped inside or scrambling to escape. We see Louise raise one hand and then freeze, as if dying.

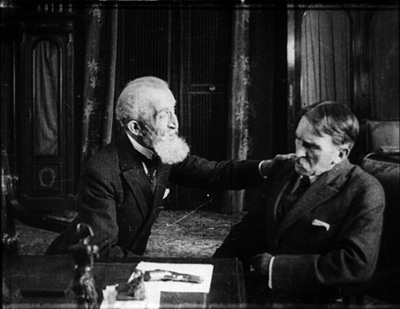

Earlier, there’s some emphatic “classical” cutting when Hardin learns that Louise is in danger. An enlarged framing (via an axial cut) underscores his reaction to the telegram.

Most striking is a series of shots of the dead-or-not Louise; the abrupt enlargement of her face has something of the force that Kurosawa would channel in his axial cuts.

Soon Ralph Ince cuts back along the same camera axis, and inward again as the couple embrace.

I can’t recall a comparable stretch of “concertina” cutting in the intimate scenes of Birth, and no such tight views of faces either. Griffith sometimes gives us “close-ups within medium-shots” by means of irising and vignetting.

Other directors (e.g., Dreyer) liked to use the serrated surround to highlight faces, but the American norm eventually became the unadorned closer view, as in the shot of Louise in The Juggernaut. Such shots probably saved production time as well. We’re confronted with the familiar situation that sometimes non-Griffith films from 1915 (e.g., The Cheat, Regeneration) look somewhat more “modern” than does Birth.

Going back to the train-through-the-bridge thing, the staging of the scene in late September 1914 elicited a lot of publicity. For one thing, the cost was played up; I’ve seen stories claiming $20,000, $30,000, and $50,000. The New York Times wrote up the shoot twice; the second of these could well be a publicity release from Vitagraph. According to the Times, the “river” was actually a flooded quarry. Before the shoot, buzz leaked out and crowds reported as numbering thousands showed up to watch. The crew spent hours herding them out of camera range. Actors were freezing in the water by the time cameramen got to take their shots. The Times also claims that the crash was filmed by fifteen (or twenty-five) cameras, a stupendously implausible number, especially in light of the footage we have. Worse, according to the second NYT story, Ince decided that the first pass didn’t work and they would have to start all over with a new train! A retake is not mentioned in Variety’s coverage, which does report some studio rivalry:

The ink on the New York dailies telling of the Vita’s big wreck stunt in the cameraing of “The Juggernaut” had hardly dried when the Universal sent over camera men posthaste Sunday to take views of what was left of the wreck. [Vitagraph studio manager Victor Smith], getting a hunch, got on the ground ahead of them and with a sturdy band of Vita “protectors” nipped the U’s little scheme in the bud.

One can only imagine how the “protectors” dealt with the Universal boys. Once more, the Variety Vault gives us the flavor, and perhaps sometimes the facts, of heroic times.

How to access the Hollywood Reporter archive, courtesy David Fristrom:

Once you are in LexisNexis, it can be a little tricky to search in The Hollywood Reporter (for some reason it doesn’t show up if you type “Hollywood Reporter” into the “Source Title” box), but you can follow these steps:

1. Click on “Power Search” in the upper-left corner.

2. On the “Power Search” page, find the “Select Source” box (near the bottom) and click on the “Find Sources” link.

3. On the “Find Sources” page, type “Hollywood Reporter” into the “Keyword” box and press enter.

4. At the top of the results should be “The Hollywood Reporter.”

Check the box next to it, then click on the “Ok-Continue” button that appears in the upper right corner.

5. You are now ready to search in the Hollywood Reporter archives –just type your search terms into the search box.

Thanks again to David!

The Variety review of The Juggernaut appears in the issue of 12 March 1915, p. 23. The story about Universal staff trying to shoot the wreckage is “Vita Putting It Over,” Variety, 10 October 1914, p. 23. The New York Times articles are “Film Train Wreck Almost a Tragedy,” NYT, 28 September 1914, p. 13, and “Tossing Dollars Around As If They Were Pennies,” NYT, 18 October 1914, p. X7. For more on Vitagraph, see Anthony Slide, The Big V: A History of the Vitagraph Company, rev. ed. (Metuchen: Scarecrow, 1987); Tony provides some production background on The Juggernaut on pp. 64-65.

The Juggernaut excerpt is available on Nickelodia 2, a DVD collection from Unknown Video. Oddly, the snapcase doesn’t list the reel as included on the disc, nor does the product information on the Unknown Video site or Amazon. I’d welcome more information about The Juggernaut‘s plot resolution if anybody out there has any.

The Juggernaut (1915).

The ten best films of … 1920

High and Dizzy

Kristin here:

Three years ago, we saluted the ninetieth anniversary of what was arguably the year when the classical Hollywood cinema emerged in its full form. The stylistic guidelines that had been slowly formulated over the past decade or so gelled in 1917. We included a list of what we thought were the ten best surviving films of that year.

In 2008 we again posted another ten-best list, again for ninety years ago. This annual feature has become our alternative to the ubiquitous 10-best-films-of-2010 lists that print and online journalist love to publish at year’s end. It’s fun, and readers and teachers seem to find our lists a helpful guide for choosing unfamiliar films for personal viewing or for teaching cinema history. (The 1919 entry is here.)

There were many wonderful films released in 1920, but, as with 1918, I’ve had a little trouble coming up with the ten most outstanding ones. Some choices are obvious. I’ve known all along that Maurice Tourneur’s The Last of the Mohicans (finished by Clarence Brown when Tourneur was injured) would figure prominently here. There are old warhorses like Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari and Way Down East that couldn’t be left off—not that I would want to.

But after coming up with seven titles (eight, really, since I’ve snuck in two William C. de Mille films), I was left with a bunch of others that didn’t quite seem up to the same level. Sure, John Ford’s Just Pals is a charming film, but a world-class masterpiece? A few directors made some of their lesser films in 1920, as with Dreyer’s The Parson’s Widow or Lubitsch’s Sumurun. Seeing Frank Borzage’s legendary Humoresque for the first time, I was disappointed—especially when comparing it with the marvelous Lazy Bones of 1924. (Assuming we continue these annual lists, expect Borzage to show up a lot.) Chaplin didn’t release a film in 1920, and Keaton and Lloyd were still making shorts, albeit inspired shorts. Mary Pickford’s only film of the year, the clever and touching Suds, is a worthy also-ran. Choosing Barrabas over The Parson’s Widow or Why Change Your Wife? over Sumurun has a certain flip-of-the-coin arbitrariness, but we wanted to keep the list manageable. But they all repay watching.

The year 1920 can be thought of as a sort of calm before the storm. In Hollywood a new generation was about to come to prominence. Griffith would decline (Way Down East may be his last film to figure on our lists). Borzage will soon reach his prime, as will Ford. Howard Hawks will launch his career, and King Vidor will become a major director. The great three comics, Chaplin, Keaton, and Lloyd will move into features. In other countries, an enormous flowering of new talent will appear or gain a higher profile: Murnau, Lang, Pabst, Eisenstein, Pudovkin, Dozhenko, Kuleshov, Vertov, Ozu, Mizoguchi, Jean Epstein, Pabst, Hitchcock, and others. The experimental cinema will be invented, and Lotte Reiniger will devise her own distinctive form of animation. Watch for them all in future lists, which will be increasingly difficult to concoct

In the meantime, here’s this year’s ten (with two smuggled in). Unfortunately, some of these films are not available on DVD. They should be.

The great French emigré director Maurice Tourneur figured here last year for his 1919 film Victory. The Last of the Mohicans is just as good, if not better. I haven’t read the Cooper novel, set during the French and Indian War, but it’s obvious that Tourneur has pared down and changed the plot considerably. The sister, Alice, is made a less important character, with the plot focusing on two threads: the Indian attack on the British population as they leave their surrendered fort and on the virtually unspoken attraction between the heroine Cora and the Mohican Indian Uncas. The seemingly impassive gazes between these characters, forced to conceal their attraction, convey more passion than many more effusive performances of the silent period. The actress playing Cora also wore less makeup than was conventional, de-glamorizing her and making her a more convincing frontier heroine.

The film is remarkable for its gorgeous photography, with spectacular location landscapes, some apparently shot in Yosemite (below left). Tourneur’s signature compositional technique of shooting through a foreground doorway or cave opening or other aperture appears frequently (below right). (Brown’s account of the filming in Kevin Brownlow’s The Parade’s Gone By makes it sound as though he shot most of the picture, but in watching the film I find this hard to believe.)

Finally, the film stands out from most Hollywood films of its day for its uncompromising depiction of the ruthless violence of the conflict between the British and those Indians allied with the French. The scene in which the inhabitants of the fort leave under an assumed truce and are massacred can still create considerable suspense today, and the outcome puts paid to the notion that all Hollywood films end happily.

The word melodrama gets tossed around a lot, and many would think of much of D. W. Griffith’s output as consisting of little besides melodramas. But Way Down East is the quintessential film melodrama. An innocent young woman (Lillian Gish) is lured into a mock marriage and ends up deserted and with a baby. The baby dies and she finds a place as a servant to a large country family, where the son (Richard Barthelmess) falls in love with her. Her sinful status as an unwed mother leads the family patriarch to order her out, literally into the stormy night. She ends up on an ice flow, headed toward a waterfall. Along the way there’s comic relief from some country bumpkins and a naive professor who falls for the hero’s sister. It all works, partly because Griffith treats the main plot with dead seriousness and partly because Gish elicits considerable sympathy for her character.

Not only is it a great film, but it provides a window into the past, preserving a popular nineteenth-century play and giving insight into the drama of that era. It’s hard to think of another feature film that conveys such a genuine record of the Victorian theater, directed by a man who had made his start on the stage of the same period. (Unfortunately the film does not survive complete. The Kino version linked above is from the Museum of Modern Art’s restoration, which provides intertitles to explain what happens during missing scenes.)

Way Down East displayed a conservative attitude toward sex that was rapidly receding into the past–at least as far as the movies were concerned. The same year saw two films that set the tone for the Roaring ’20s in their more risqué depiction of romantic relationships: Cecil B. De Mille’s Why Change Your Wife? and Mauritz Stiller’s frankly titled Swedish comedy Erotikon.

De Mille has featured on our previous lists, for Old Wives for New in 1918 and Male and Female in 1919. Why Change Your Wife? ramped up the sexual aspect of the plot, however, as a Photoplay reviewer made clear: “”Having achieved a reputation as the great modern concocter of the sex stew by adding a piquant dash here and there to Don’t Change Your Husband, and a little more to Male and Female, he spills the spice box into Why Change Your Wife?” The plot is not nearly as daring as this suggests. Gloria Swanson plays a wife who is straight-laced and intellectual, driving her husband to spend time with a stylish woman who tries to seduce him. Yet he flees after one kiss, and after his wife divorces him on the assumption that he has cheated on her, he marries the seductress. The heroine discovers the error of her ways and becomes sexy in her dress and behavior. As a result the husband regains his old love for her, and they remarry. No actual adultery occurs, and the first marriage is affirmed with a happy ending.

Why Change Your Wife? may have seemed more daring because De Mille here externalizes the shifting relationships through the costumes to the point where no viewer could miss the implications. Initially the wife’s demure dresses mark her as prudish, while the woman who lures her husband away is dressed like a vamp. Once the wife lets go, she dons similar revealing, expensive designer clothes. As a result, the male members of the audience might revel in a fantasy of their ideal wife, and the women would delight in displays of fashions most of them could never own in reality. It proved a successful combination. We tend to forget it now, but the 1920s was full of variants and imitations of Why Change Your Wife?, often featuring a fashion-show scene that was nothing but a parade of models in outlandish clothes. (Early Technicolor was sometimes shone off in such sequences.) Top designers like Erté were recruited to bring their talents to such films.

Fashion as a selling point in films remains with us. The glossy new version of The Hollywood Reporter, recently decried by David, now has a regular “Hollywood Style” section. The November 24 issue ran “Costumes of The King’s Speech,” and the December 1 issue describes “Fashions of The Tourist,” with photos of Angelina Jolie in her various costumes. In addition to shots of the stars, both articles feature enticing close-ups of lipstick, shoes, jewelry,and purses.

A double feature of Why Change Your Wife? and Erotikon would provide a vivid sense of the differing moral outlooks of mainstream America and Europe in the post-war years. In Erotikon, the situation is reversed. An absent-minded entomologist neglects  his sexy wife, who is having an affair with a nobleman. She is in love, however, with a sculptor, who is having an affair with his model. The sculptor returns her love, but eventually becomes jealous, not of her husband, who is his best friend, but of her lover. When the husband finds out that his wife has been unfaithful, he is mildly upset, but he settles down happily with his cheerful young niece, who pampers his taste for plain cooking and an undemanding home life. About the only thing these two films have in common is that they view divorce, which was still quite a controversial issue in the 1920s, as sometimes benefiting the people involved. Adultery actually occurs rather than being hinted at but avoided, though faithful monogamy is ultimately put forth as the ideal.

his sexy wife, who is having an affair with a nobleman. She is in love, however, with a sculptor, who is having an affair with his model. The sculptor returns her love, but eventually becomes jealous, not of her husband, who is his best friend, but of her lover. When the husband finds out that his wife has been unfaithful, he is mildly upset, but he settles down happily with his cheerful young niece, who pampers his taste for plain cooking and an undemanding home life. About the only thing these two films have in common is that they view divorce, which was still quite a controversial issue in the 1920s, as sometimes benefiting the people involved. Adultery actually occurs rather than being hinted at but avoided, though faithful monogamy is ultimately put forth as the ideal.

Erotikon reflects some of the influences from Hollywood that were seeping into European films after the war. Sets are larger, cuts more frequent (though not always respecting the axis of action), and three-point lighting crops up occasionally. Yet Stiller maintains the strengths of the Scandinavian cinema of the 1910s, with skillful depth staging (left) and a dramatic use of a mirror. In the opening of a crucial scene where the sculptor confronts the wife with her adultery, tension builds because she does not know he is watching her until she sees him in the mirror (see bottom). Still, apart from its European sophistication, Erotikon could pass for an American film of the same era. Stiller and lead actor Lars Hansen would both be working in Hollywood by the mid-1920s.

I can’t allow the nearly unknown director William C. de Mille to take up two slots this year, though it’s tempting. William’s career was shorter than that of his much better-known brother Cecil. It peaked in 1920 and 1921, though, and I still look back fondly on the films by him that were shown in “La Giornate del Cinema Muto” festival of 1991. That year saw a large retrospective of Cecil’s films, and the organizers wisely decided to include a  sampling of William’s surviving work.

sampling of William’s surviving work.

The two men’s approaches were markedly different. Where Cecil by this point was setting his films among the rich and using visual means like costumes to make the action crystal-clear to the audience, William was more likely to favor middle-class settings with small dramas laced with humor and presented with restrained acting and small props. Despite William’s skill as a director and his ability to create sympathy for his characters, he never gained much prominence, especially compared to his brother. He retired from filmmaking in 1932, at the relatively young age of 54. Yet obviously he was attuned to his brother’s style, having written the script for Why Change Your Wife? It may be characteristic of the two that Cecil capitalized the De in De Mille, while William didn’t.

Relatively few of William’s films survive, but these include two excellent films from 1920, Jack Straw and Conrad in Quest of His Youth. I don’t remember Jack Straw well enough to describe it. It involved the hero’s falling in love with a woman when they both live in the same Harlem apartment building. When her family becomes rich, Straw disguises himself as the Archduke of Pomerania in order to woo her. Sort of a Ruritanian romance but played out in the U.S.

I remember Conrad in Quest of His Youth better. The hero returns from serving as a soldier in India. He feels old and decides to try and recover his youth. The first attempt comes when he and three cousins agree to return to their childhood home and indulge themselves in the simple pleasures of their youth. Eating porridge for breakfast is a treasured memory, but the group discovers that this and other delights are no longer enjoyable to them as adults. Conrad goes on to seek romance elsewhere and eventually finds a woman who makes him feel young again. The film’s poignant early section manages in a way that I’ve never see in any other film to convey both nostalgia for the joys of childhood and the sad impossibility of recapturing them.

Neither film is available on DVD. Indeed, I couldn’t find an image from either to use as an illustration. The only picture I located is a rather uninformative one from Conrad in Quest of His Youth, above right, which I scanned from William C.’s autobiography (Hollywood Saga, 1939). It’s no doubt an indicator of William’s modesty that the frontispiece of this book is a picture of his brother directing a film.

Maybe this entry will serve as a hint to one of the DVD companies specializing in silent movies that these two titles deserve to be made available. They’re high on my list of films I would love to see again.

Most people who study film history see Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari very early on, though they probably push it to the backs of their minds later on. I have a special fondness for Caligari precisely because I did see it early on. I took my first film course, a survey history of cinema, during my junior year. Maybe I would have gotten hooked and gone on to graduate school in cinema studies anyway, but it was Caligari that initially fascinated me. It was simply so different from any other films I had seen in what I suddenly realized was my limited movie-going experience. It inspired me to go to the library to look up more about it, a tiny exercise in film research.

Some may condemn it as stage-bound or static. Despite its painted canvas sets and heavy makeup, however, it’s not really like a stage play. Many of the sets are conceived of as representing deep space, though often only with a false perspective achieved by those painted sets:

Still, in an era when experimental cinema was largely unknown, Caligari was a bold attempt to bring a modernist movement from the other arts, Expressionism, into the cinema. It succeeded, too, and inaugurated a stylistic movement that we still study today.

I haven’t watched Caligari in years (I think I know it by heart), but I’m still fond of it. The plot is clever grand guignol. It has three of the great actors of the Expressionist cinema, Werner Krauss, Conrad Veidt, and Lil Dagover, demonstrating just what this new performance style should look like. The frame story retains the ability to start arguments. The set designs area dramatically original, and muted versions of them have shown up in the occasional film ever since 1920. Even if you don’t like it, Caligari can lay claim to being the most stylistically innovative film of its year.

As I did for our 1918 ten-best, I’m cheating a bit by filling one slot of the ten with a pair of shorts by two of the great comics of the silent period. Both have matured considerably in the intervening two years. In 1918, Harold Lloyd was still working out his “glasses” character. By this point he is much closer to working with his more familiar persona. Similarly, in 1918, Buster Keaton was still playing a somewhat subordinate role in partnership with Fatty Arbuckle. In 1920, he made his first five solo shorts, co-directing them with Eddy Cline.

The Lloyd film I’ve chosen is High and Dizzy, the second short in which he went for “thrill comedy” by staging part of the action high up on the side of a building. (See the image at the top.) Four years later he would build a feature-length plot around a climb up such a building in Safety Last, one of his most popular films. In High and Dizzy, Harold is not quite the brash (or shy) young man he would soon settle on as the two variants his basic persona. The opening shows him as a young doctor in need of patients. He soon falls in love with the heroine, and through a drunken adventure, ends up in the same building where she lies asleep. She sleepwalks along a ledge outside her window, and when Harold goes out to rescue her, she returns to her bedroom and unwittingly locks him out on the ledge. The film is included in the essential “Harold Lloyd Comedy Collection” box-set, or on one of the two discs in Kino’s “The Harold Lloyd Collection,” Vol. 2.”

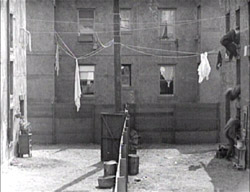

Neighbors was the fifth of the five Keaton/Cline shorts made in 1920. (It was actually released in early 1921, but I’ll cheat a little more here; there are other Keaton films to come in next year’s list.) It’s a Romeo and Juliet story of Keaton as a boy in one working-class apartment house who loves a girl in a mirror-image house opposite it. Two bare, flat yards with a board fence running exactly halfway between them separate the lovers. Naturally the two sets of parents are enemies.

Lots of good comedy goes on inside the apartment blocks, but the symmetrical backyards and the fence inspire Keaton. We soon realize that his instinctive ability to spread his action up the screen as well as across it was already at play. The action is often observed straight-on from a camera position directly above the fence, so that we–but usually not the characters–can see what’s happening on both sides. For one extended scene involving policemen, Keaton perches unseen high above them, hidden. Even though we can’t see him, the directors keep the framing far enough back that the place where we know he’s lurking is at the top of the frame as we watch the action unfold. The playful treatment of the yard culminates in an astonishingly acrobatic gag that brings in Keaton’s early music-hall talents.

The boy and girl have just tried to get married, but her irate father has dragged her home and imprisoned her in a third-floor room. She signals to Keaton, across from her in an identical third-floor window. A scene follows in which two men appear from first- and second-story windows below Keaton, and he climbs onto the shoulders of the two men below. This human tower crosses the yard several times, attempting to rescue the girl; each time they reach the other side, they hide by diving through their respective windows:

They perform similar acrobatics on the return trips to the left side, carrying the bride’s suitcase or fleeing after her father suddenly appears.

Neighbors is included as one of two shorts accompanying Seven Chances in the Kino series of Keaton DVDs, available as a group in a box-set.

Our final two films lie more in David’s areas of expertise than mine, so at this point I turn this entry over to him.

DB here:

With Barrabas Feuillade says farewell to the crime serial. Now the mysterious gang is more respectable, hiding its chicanery behind a commercial bank. Sounds familiar today. As Brecht asked: What is robbing a bank compared with founding a bank?

Over it all towers another mastermind, the purported banker Rudolph Strelitz. In his preparatory notes Feuillade called him “a sort of sadistic madman, a virtuoso of crime . . . a dilettante of evil.” Against Strelitz and his Barrabas network are aligned the lawyer Jacques Varèse, the journalist Raoul de Nérac (played by reliable Édouard Mathé), and the inevitable comic sidekick, once again Biscot (so perky in Tih Minh).

The film’s seven-plus hours (or more, depending on the projection rate) run through the usual abductions, murders, impersonations, coded messages, and chases. But there’s little sense of the adventurous larking one finds in Tih Minh (1919), in which the hapless villains keep losing to our heroes. The tone of Barrabas is set early on, when Strelitz forces an ex-convict into murder, using the letters of the man’s dead son as bait. The man is guillotined. The epilogue rounds things off with a series of happily-ever-afters in the manner of Tih Minh, but these don’t dispel, at least for me, the grim schemes that Strelitz looses on a society devastated by the war. Add a whiff of anti-Semitism (the Prologue is called “The Wandering Jew’s Mistress”), and the film can hardly seem vivacious.

According to Jacques Champreux, Barrabas was the first installment film for which Feuillade prepared something like a complete scenario, although it evidently seldom described shots in detail. The film has a quick editing pace (the Prologue averages about three seconds per shot), but that is largely due to the numerous dialogue titles that interrupt continuous takes. With nearly twenty characters playing significant roles and some flashbacks to provide backstory, there’s a lot of information to communicate.

Of stylistic interest is Feuillade’s movement away from the commanding use of depth we find in Fantômas and other of his previous masterworks. Here the staging is mostly lateral, stretching actors across the frame. Very often characters are simply captured in two-shot and the titles do the work, as if Feuillade were making talking pictures without sound. Once in a while we do get concise shifting and rebalancing of figures, usually around doorways. Here Jacques vows to go to Cannes and tell the police of the kidnapping of his sister. As Raoul and Biscot start to leave, Jacques pivots and says goodbye to Noëlle, creating a simple but touching moment of stasis to cap the scene.

Full of incident but rather joyless, Barrabas will never achieve the popularity among cinephiles of the more delirious installment-films, but it remains a remarkable achievement. The ciné-romans that would follow until Feuillade’s death in 1925 would lack its whiff of brimstone. They would mostly be melodramatic Dickensian tales of lost children, secret parents, strayed messages, and faithful lovers. Barrabas is not available on DVD.

You might think that a movie that opens with a frowning old man studying a skeleton would also be somewhat unhappy fare. Such isn’t actually the case with Victor Sjöström’s generous-hearted Mästerman, a story of a village pawnbroker obliged to take a young woman as a housekeeper. With his stovepipe hat and air of sour disdain, Samuel Eneman, known to the village as Mästerman, is a ripe candidate for rehabilitation. Once Tora is installed and has put a birdcage (that silent-cinema icon of trapped womanhood) on the window sill, the scene is set for Mästerman’s return to fellow feeling. But she is there merely to cover the debts and crime of her sailor boyfriend, and eventually Eneman realizes he must make way for young love. The drama is played out in front of the townspeople, and as often happens in Nordic cinema (e.g., Day of Wrath, Breaking the Waves) the community plays a central role in judging, or misjudging, the vicissitudes of passion.

As a director Sjöström is a marvel. His finesse in handling the 1910s “tableau style” shines forth in Ingeborg Holm (1913), but unlike Feuillade and most of his contemporaries, he immediately grasped the emerging trend of analytical editing. His The Girl from the Marsh Croft (1917) and Sons of Ingmar (1918-1919) show a mastery of graded shot-scale, eyeline matching, and the timing of cuts. In Mästerman he continued to use brisk editing and close-ups to suggest the undercurrents of the drama. He moves people effortlessly through adjacent rooms, and his long-held passages of intercut glances recall von Stroheim. On all levels, Mästerman deserves to be more widely known–an ideal opportunity for an enterprising DVD company.

As a director Sjöström is a marvel. His finesse in handling the 1910s “tableau style” shines forth in Ingeborg Holm (1913), but unlike Feuillade and most of his contemporaries, he immediately grasped the emerging trend of analytical editing. His The Girl from the Marsh Croft (1917) and Sons of Ingmar (1918-1919) show a mastery of graded shot-scale, eyeline matching, and the timing of cuts. In Mästerman he continued to use brisk editing and close-ups to suggest the undercurrents of the drama. He moves people effortlessly through adjacent rooms, and his long-held passages of intercut glances recall von Stroheim. On all levels, Mästerman deserves to be more widely known–an ideal opportunity for an enterprising DVD company.

For a valuable source on Feuillade’s preparation for Barrabas and other of his works see Jacques Champreux, “Les Films à episodes de Louis Feuillade,” in 1895 (October 2000), special issue on Feuillade, pp. 160-165. I discuss Feuillade’s adoption of editing elsewhere on this site.

Tom Gunning provides an in-depth discussion of Sjöström’s style at this period in “‘A Dangerous Pledge’: Victor Sjöström’s Unknown Masterpiece, Mästerman,” in Nordic Explorations: Film Before 1930, ed. John Fullerton and Jan Olsson (Sydney: John Libbey, 1999), pp.204-231. For more on some of the directors discussed in this entry, check the category list on the right.

Erotikon.

Trade secrets

DB here:

Over the last couple of months, some strange things have been happening to America’s most venerable show-business trade papers. In the case of Variety, the strange thing is very important and yields almost unalloyed good news. In the case of The Hollywood Reporter, the strange thing is, at least for the moment, a step backward.

Kristin and I have subscribed to weekly editions of both newspapers since the mid-1990s. With the advent of Web 2.0, each paper created an online archive, more or less searchable, stretching back into the 1990s. Not everything you would wish for, since Variety started publishing in 1905 and The Hollywood Reporter began in 1930. But film historians are grateful for anything. I found both papers’ archives very helpful in reworking Planet Hong Kong over the last year. Now, however, some of the recent happenings affect our ability to do research.

Issues about issues

First the bad strange new thing. In a collapsing advertising market, The Hollywood Reporter has done a makeover. From being a daily and weekly trade paper it turned into an upscale lifestyle weekly, sort of an industry-slanted version of Vanity Fair‘s movie issue, with a soupçon of airline magazine. Among the recycled press releases, superficial interviews, soft-focus profiles, and awards-season handicapping, you find fashion tips like “Into the Blue: Punch up your executive look—top to toe—with the season’s blockbuster hue.” There’s also the sort of feature that movers and shakers can use to promote themselves: “Hollywood’s Young Guns ….Where they work, why they matter, how they’re changing the game.”

True, Variety sometimes resorted to such frippery in these desperate years. V-Life was in some ways a forerunner of the new HR, but V-Life was a supplement. In the main paper you could still find reportage, analysis, overviews, and opinion. There’s relatively few of these ingredients in the new Hollywood Reporter.

If this is the strategy for fighting Movie City News and Deadline Hollywood and IFC, I’m betting on the webroots.

Anyhow, forget the daily THR ephemera. I want to go into the past, as I did until October, scrambling through elusive coverage of Hong Kong stuff. Problem is: I can’t do that any more.

THR not only remade its magazine; it remade its website, radically. So radically that when I go there via Safari or Chrome I get this welcome.

Well, you say, skip your bookmarks and go through Google. But then:

Only Firefox does the trick.

Anyhow, at last I’m on. Breaking News today starts with “Jennifer Grey Wins ‘Dancing with the Stars’; Bristol Palin Comes in Third.” Skip that. As a subscriber, I ought to be able to log in to the proprietary content, right?

Here is the routine. Using my old password, I have no luck. When I call the 800 number, an ominous recording tells me that they are aware of the “issues” (what we used to call “problems”) with the website and subscriber logins. After half an hour, a hard-working person answers and with a few magic passes of her mouse she gets me into the subscriber areas.

Yet the next time I try, I’m refused again. So I write to the email service they announce, and immediately get a form reply saying that my problem will be addressed in 1-2 business days. The next communiqué, from some days later, begins: “We apologize for the delayed response.” They give me a password which is suspiciously generic.

This has been going on for nearly three weeks. But I can live with it because I’m not so concerned with Jennifer Grey or Bristol Palin. I’m there for the archive.

Problem is, the Archive isn’t there for me. Once I’m inside as a subscriber, I find no way to get into the two decades of stories and stats I could reach under the earlier incarnation of the website.

Another call, another recording apologizing for the “issues,” another half-hour of wait, and now a very puzzled answerperson. Where’s the Archive? Nobody ever asked him that before. He’s no better than I am at finding a button for it. He consults his supervisor. The supervisor doesn’t know where the Archive went either.

You can search the site, he points out. True, but the search takes me only to items posted since the makeover began.

Hmmm. The best they can do is suggest I call the Editorial Offices. When I do, the recording instructs me to leave my story tip and someone will get back to me. I might say, “Psst, I have it on good authority that the next big color will be vermillion,” but instead I hang up.

Trying tonight, I find that the search function now turns up articles published throughout calendar 2010, but no earlier. So maybe THR will gradually expand its backfile. It would be too bad if the dolled-up version of the print mag drained resources from maintaining a stable and deep website. I worry that THR intends to dump the old (already very partial) online archive altogether, resetting the clock at the year of the makeover. If so, they send a signal that the past—theirs, that of the industry they cover—doesn’t matter. They wouldn’t even agree with Jack Valenti, who supposedly did say, “It’s only history,” and then opened the MPPDA papers for research.

Infinite Variety

13 September 2010 was the date of the good thing that happened to the trade papers. At that point, Variety went the opposite direction of The Hollywood Reporter. It opened up its vault completely.

For many years film historians have relied on Variety for detailed information about how Hollywood and other national industries have worked. Most of these historians have scanned the paper on microfilm, cranking through reel after reel, getting dizzy from the whizzing lines your eyes try to fasten on. But these scholars managed to do real research. You couldn’t believe everything you read in the paper, of course; you had to be skeptical. Still, getting something was always better than getting nothing.

More recently, Variety has kept an online archive of its materials since the early 1990s. These stories were in html-friendly format, not in the form of published pages, and some stories that appeared in the paper never made it online or were revised for the net. Older stories, mostly film reviews, were summarized and undated. So as records, they were only partly reliable. Still, even this iceberg-tip was well worth surveying.

In September, though, Variety put online its back file from 1906 to the present. Every page of the weekly and daily paper has been digitized. You can access it for a year for a $600 subscription fee, probably what many people pay for designer coffee over the same period. If you want shorter-term access, $60 gets you into up to 50 issues per month.

Reader, I signed up.

There were teething pains for a few weeks. Some pages failed to load, and often you had to scroll through an entire issue to find the page you wanted. But those “issues” are mostly in the past. Now you can plunge into an ocean of well-mapped movie coverage.

As usual with people of my generation, I’m shaken by the abrupt transition from a research economy of scarcity to one of overabundance. Had this bounty existed when Kristin and Janet Staiger and I wrote The Classical Hollywood Cinema, we might still be writing it. Type in “John Ford” or “Meet Me in St. Louis” and you’re led into the labyrinth, with one item teasing you to search others, forever.

Some things, for instance, seem never to change. “CINEMAS TO SURVIVE HI-TECH ERA,” wrote A. D. Murphy in the 4 August 1982 issue’s top story. People were claiming that the theatre experience would soon vanish (presumably because of home video, although that’s barely mentioned). No way, says Murphy, citing several reasons, including the plausible assumption that “Nothing yet has managed to keep young people confined to their homes.” He adds that going out to the movies is the most robust form of “pay per view….free of all that bother of billing, dunning, disconnects and such.”

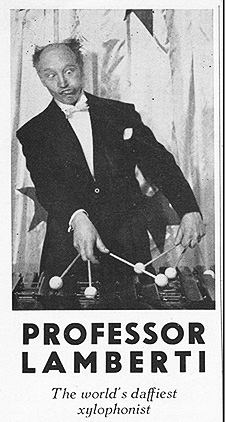

Yet a stroll through the vault can also remind you of how strange things were back then. How’d you like to sit through a live opening act before Citizen Kane? Variety tells us that in San Francisco’s Golden Gate theatre in early September 1941, Kane did brisk business at popular prices. It was accompanied by the vaudeville act of one Prof. Lamberti. The local Hearst newspapers, while refusing to advertise Kane for the unsurprising reason that Hearst thought the movie was about him, did advertise Prof. Lamberti’s act at the house. He was worth paying attention to. He never made snide fun of Marion Davies.

Yet a stroll through the vault can also remind you of how strange things were back then. How’d you like to sit through a live opening act before Citizen Kane? Variety tells us that in San Francisco’s Golden Gate theatre in early September 1941, Kane did brisk business at popular prices. It was accompanied by the vaudeville act of one Prof. Lamberti. The local Hearst newspapers, while refusing to advertise Kane for the unsurprising reason that Hearst thought the movie was about him, did advertise Prof. Lamberti’s act at the house. He was worth paying attention to. He never made snide fun of Marion Davies.

But who was Prof. Lamberti? A magician, a musician, a real prof? We check Variety for 22 March 1950 and learn from his obituary that “Professor” Lamberti was a comedian who played on stage and in nightclubs. According to the obit:

Lamberti’s best known act was playing the xylophone, while shapely gal did a striptease back of him and he was apparently unaware of the goings on. This provided the delusion that successive encores on the semi-classic tunes such as “Listen to the Mocking Bird” were prompted by the audience’s music appreciation, rather than the bumps and grinds of the peeler. Howl finish had the comic get hep and seltzer squirt the gal off stage.

I ask you: How could a red-blooded American male viewer concentrate on the ambiguities of Thompson’s quest after an opening act like that? And as a mood-setter for the opening sequence at Xanadu, the World’s Daffiest Xylophonist might not be ideal. Even more striking, we learn from the same obit that Prof. Lamberti did his signature bit in the film Tonight and Every Night (1945) with Rita Hayworth “as the strip-gal”—the same Rita Hayworth who was then married to Citizen Kane’s director.

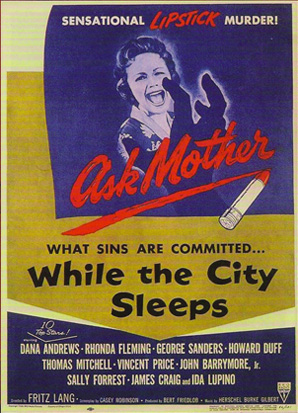

Aha, you say, but Wikipedia has an article on Prof. Lamberti too, and with more details than the Variety obit. (Please visit this orphan entry; it needs hits.) I would never badmouth Wikipedia, that wonder of our young century, but it’s not yet the poor man’s Variety vault. For one thing, it doesn’t use the phrase “bumps and grinds of the peeler.” Further, I can find no help on Wikipedia on a looming question that has vexed some of our best minds: At what aspect ratio should Lang’s While the City Sleeps (1956) be shown?

A lack of ‘Scope

There is a full-frame version occasionally broadcast on Turner Classic Movies and now available on Region 2 DVD. There’s also a 1.66 crop that was released on laserdisc many years ago. Some older cinephiles recall seeing a widescreen anamorphic version circulating on 16mm. Yet Lang apparently claimed he did not shoot the film in anamorphic widescreen.

When While the City Sleeps was made, the releasing studio RKO was supporting a widescreen system called SuperScope. That’s what Variety called it, anyhow, though sometimes you’ll see the name with a small middle s, or with “Super” italicized.

Invented by the brothers Joseph and Irving Tushinsky, SuperScope was a progenitor of the Super-35mm system of today. A film shot in standard full-frame 35mm would be turned into an anamorphic one. A portion of the frame was extracted, optically squeezed, and printed as an anamorphic image, which would then be unsqueezed in projection. The aspect ratio was 2.0:1. The reasoning was that it was easier to shoot a movie in the standard way and then “SuperScope” it than it was to shoot a CinemaScope film. Some projectionists called this process BogusScope, not just because it was fake but because Benedict Bogeaus was then a producer feeding projects to RKO, and some of his titles used the format.

Slightly Scarlet and Invasion of the Body Snatchers, both released in 1956, were designed to be given the SuperScope treatment. The films carry the logo in their credits, and contemporary Variety reviews mention the process by name (15 February 1956 and 29 February 1956). The accompanying Italian poster for While the City Sleeps also makes reference to the SuperScope process. But there is no mention of SuperScope on the release print, or in the Variety review (2 May 1956), or in the US release poster, or in the pressbook kindly posted online by TCM.

Lang is on record, in Peter Bogdanovich’s Who the Devil Made It, as saying that he disliked CinemaScope. He told Bogdanovich that he agreed with his famous claim in Godard’s Contempt that “CinemaScope is only good for snakes and funerals” (p. 224). But SuperScope is not CinemaScope (which is 2.35:1 or sometimes even wider), and moreover Lang made one of the better CinemaScope films in Moonfleet (1955). So the question can’t immediately be resolved on auteur grounds.

Moreover, SuperScope prints of While the City Sleeps do exist. I found one in a European archive some years ago. It was pretty fuzzy (a chronic problem with SuperScope prints, because of the rephotography involved), but I took some frames from it. Here are some comparisons with the 1.37 DVD.

For my purposes here, I could have simply cropped and blown up the full-aperture frame grabs, but I’d rather preserve the slightly bulgier quality that seems to have come with the anamorphic optics. Also, because the wider versions are from 35mm frames, they include a little more area on the sides, which is lost in video versions like my DVD grabs on the left.

Actually, the widescreen version isn’t terribly offensive to me. For one thing, it slices off that slab running across the top of the bar set in the first image above. But in some cases the change in shot scale and internal relations make for mild differences in emphasis. The SuperScope version brings characters quite a bit nearer to us. Do they also seem seem closer together? There’s also the matter of taste. Some will dislike the headroom in the left shot below, while noting that the right one looks like a classic early ‘Scope composition.

So which one is the original? You can sample the online cinephile discussions from 2003 onward here and here and here. The ever-diligent folks at DVD Beaver have much to add as well.

Fortunately, about five minutes of snooping in the Variety vault reveals the answer.

Joseph and Irving Tushinsky yesterday concluded a contract with RKO for conversion of “While the City Sleeps” into the SuperScope process for foreign release (“SuperScoping ‘City,’” Variety, 12 April 1956, p. 3).

According to other stories in Variety, several films were given the SuperScope treatment ex post facto, including a re-release of Olivier’s Henry V (1945).

So we can confirm the hunch expressed by some of the cinephiles above that the SuperScoped copies were destined for overseas screenings. The Variety vault proves useful for things both great and small. Okay, mostly small, but you get my point.

Scoping things out: An epilogue for ratio fetishists

SuperScope logo for Invasion of the Body Snatchers.

There’s still all that headroom in the full-frame images. That roominess is fairly uncharacteristic of Lang. In his pre-widescreen films, he used the whole frame, even the corners. Try SuperScoping this tightly-packed shot from Kriemhilde’s Revenge.

In Cloak and Dagger, Cooper’s character uses the apple on the workbench to explain the power locked up in the atom, and apples will become thematically significant in a later Adam-and-Eve scene.

Moonfleet also takes advantage of the lower right corner (see the image at the very end of today’s entry). But Lang’s last two American films, While the City Sleeps and Beyond a Reasonable Doubt (1956), seem to me to have more open and less compact compositions. There’s quite a bit of unused furniture in City‘s mise-en-scene, even though it adds a Vidor-Fountainhead air of vastness.

At this point we should recall that by 1956, most U. S. theatrical releases were shown in something wider than 1.33. There was a lot of variability, but films were commonly cropped in printing or projection to 1.66 or 1.75 or 1.85. Even if Lang did not shoot City with an anamorphic ratio in mind, he might well have assumed there would be cropping to some wide ratio. The approximately 1.75 ratio seen on the laserdisc version looks like a reasonable compromise between the extremes.

I’m inclined to say that Lang expected the film to be cropped somewhat in projection, but probably not to the full 2.0 proportions. He could no longer count on projectionists’ framing a single ratio, so he doesn’t tuck details along the edges or into the corners.

Unfortunately, I can’t find confirmation of Lang’s wide-frame choices in the fabled Variety vault. But I’m still looking, there and elsewhere. And maybe some researcher reading this entry can clarify things further. In any case, Variety has given a magnificent gift to those of us interested in film history–who ought to be everybody.

The standard source on widescreen systems of the postwar era is Robert E. Carr and R. M. Hayes, Wide Screen Movies: A History and Filmography of Wide Gauge Filmmaking (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 1988). Carr and Hayes discuss SuperScope, or as they call it SuperScope (the credit logo is actually in caps, as in SUPERSCOPE) on pp. 67-72 and list the films in that format on p. 104. They don’t include While the City Sleeps. See also Daniel Sherlock’s comments on the book at Film-Tech.

Writing this has led me to wonder whether the admiration of European, especially French, critics for While the City Sleeps is based on their seeing the anamorphic version. In their writings I haven’t found specific reference to SuperScope. Raymond Bellour’s probing 1966 essay “On Fritz Lang” is one of the few I know from that period to scrutinize the patterns of composition and framing in While the City Sleeps, but I can’t tell whether he’s referring to the widescreen version. An English translation is in Fritz Lang: The Image and the Look, ed. Stephen Jenkins; see pp. 31-35.

Although Turner Classic Movies has run While the City Sleeps in 1.37, the TCM website recommends that it play at 1.66. Interestingly, the illustrations in Tom Gunning’s Films of Fritz Lang are in about 1.75:1 ratio. Another SuperScope production, Jacques Tourneur’s Great Day in the Morning (1956), runs on TCM in this ratio. Since projectionists of the period, and still today, are fairly flexible about ratios, it’s possible that even anamorphic 2.0 SuperScope was projected with a little trimmed from the sides.

A DVD release of Invasion of the Body Snatchers includes both a SuperScope 2.0 version and a 1.37 one. But the 1.37 one is a pan-and-scan version of the SuperScope one, not the integral frame that SuperScope worked from. The DVD version of Slightly Scarlet from VCI International is framed at 1.78, and the transfer (of poor optical quality) has been bungled so that everything is slightly stretched left to right. Both Arlene Dahl and Rhonda Fleming are more zaftig than they should be.

For more on aspect ratios, you can go here and here on this site. I experiment with extracting ‘Scope proportions from a 1930s movie in a general essay on widescreen aesthetics, “CinemaScope: The Modern Miracle You See without Glasses,” in Poetics of Cinema, p. 323.

Correction (28 November 2010): The original version of the piece claimed that the Search function of the Hollywood Reporter website found only pieces published since the recent makeover. That was the case when I used it two weeks ago. A more recent search I conducted this evening turned up articles from throughout 2010. I have recast the entry to reflect this change.

PS (17 December 2010): More developments on the Hollywood Reporter backfile, and more on the uses of the Variety Vault are discussed in this later entry.

Moonfleet.

Bond vs. Chan: Jackie shows how it’s done

DB here:

During the 1990s several critics began to notice that filmmakers were doing something odd with action scenes.

Directors were consciously, even joyously, sacrificing clarity. When two characters were punching it out, the framing didn’t make it easy to know who was hitting whom, and how. Changes in angle and shot scale were sometimes so abrupt that you had little time to adjust. The cutting pace was so quick that you couldn’t entirely register the movement in shot A before shot B replaced it. Sometimes the spatial layout of the fight was confusing as well: too many close views, too few master shots. Later, the return of handheld shooting made many action scenes even more illegible, blurring and smearing them to the point that sound (as in the Bourne films) had to specify that a body has hit a window or a hand has busted a bottle. Now we have Sylvester Stallone’s The Expendables, which might be a new summit in overbusy, incoherent, inconsequential action.

I wrote about this trend back in the 1990s, and I’ve returned to it on occasion since. Other writers, notably Todd McCarthy of Variety, noticed it too. He referred to the full-throttle editing and “frequently incoherent staging” on display in Armageddon (1998): “Bay’s visual presentation is so frantic and chaotic that one often can’t tell which ship or characters are being shown, or where things are in relation to one another.”

A decade later comes Peter DeBruge’s review of the “muddled execution” of The Expendables: Staging simultaneous fights “might’ve worked had the editors assembled all that footage in such a way that we could tell where characters are in relation to one another or what’s going on.”

The Michael Bay approach has become the principal way in which action scenes are shot. It isn’t absence of craft that leads to these aimless bouts. The filmmakers actively want the action to be hard, even impossible, to follow. Sometimes I think that this blurred bustle is there to secure a PG-13 rating; if you could really see the mayhem, we might be moving toward an R. But filmmakers don’t say that they’re self-censoring. They seem to think that making the action illegible is creative because it promotes realism.

Stallone explains why he scrambled up the fight scenes in The Expendables.

I don’t think many action scenes are shown from the character’s point of view. They are more from the director’s point of view. On Rambo, I thought the most economical and original way to shoot [the action] would be through Rambo’s eyes—if he were directing, what would his style be? But The Expendables is an ensemble picture, so it’s somewhat of a blend. I thought, ‘This is not supposed to hang in the Louvre.’ I wanted it to be disjointed and rough, not choreographed. If you really were filming a big battle with five cameras, [their footage] would not all flow together, so we set up the [cameras] to film the action we’d scripted and told the operators they were on their own. We said, ‘Do the best you can, and we’ll use the interesting shots from the characters’ perspectives.’”

Camera operator Vern Nobles describes shooting the action as “multi-camera craziness.”

You might point out that if somebody were really filming a big fight with five cameras, at least a couple of camera operators would be shot or punched silly. And presumably a few times we’d actually see other cameras.

Realism, as usual, is simply a fig leaf for doing what you want. Virtually any technique can be justified as realistic according to some conception of what’s important in the scene. If you shoot the action cogently, with all the moves evident, that’s realistic because it shows you what’s “really” happening. If you shoot it awkwardly, that presentation is “realistically” reflecting what a participant perceives or feels. If you shoot it as “chaos” (another description that Nobles applies to the Expendables action scenes)—well, action feels chaotic when you’re in it, right?

Forget the realist alibi. What do you want your sequence to do to the viewer? Do you want it to pass along an impression of bustle and flurry? Or do you want to make the viewer wince, recoil, even mildly reenact the movements of the players? Then follow the Hong Kong tradition. Yuen Woo-ping once told me that his goal was to make the viewer “feel the blow.” To convey the effort and strain, the impact and pain: that’s something worth doing.

It’s something that the blur-o-vision tussles lack, but even fights that are more carefully filmed are strangely unmoving. In Tomorrow Never Dies (1997), there’s a fistfight on a catwalk above a rotary press line. The presentation is more or less spatially unified, but it lacks drive because of certain creative choices. For instance, when Bond punches a security guard, the man simply drops out of the frame.

Where does he go? He doesn’t fall off the catwalk but seems to grab the railing, so maybe he’ll return for another go-round. But he doesn’t. As Bond falls back, another guard sneaks up on him. The framing and screen direction suggest that he’s approaching Bond from the front.

Actually, he’s sneaking up from the rear.

When Bond turns, we don’t see his punch.

In fact, we don’t see much of anything. Although the attacker is erect in one shot, he seems to be kneeling in the next, when Bond kicks him, somewhere below the frameline.

The attacker is standing again in the next shot, and he’s flung backward by the force of Bond’s unseen kick.

When the man returns, he tries to tackle Bond. At least, I think he does. The maneuver takes place, again, underneath the frameline.

At last we get a wider shot, but this serves mainly to align the fight with the conveyor belt below the men; guess who will fall?

More fighting, with punches and grappling blocked by the men’s bodies, culminates in Bond’s adversary falling into the print run.

Even here, however, we don’t really see what happens to the victim. He plunges through the river of newsprint and the machine starts belching.

Overall, we get a mild impression of what happened in the fight, but the action unfolds vaguely and is hardly stirring. Is this how you earn a PG-13?

The Hong Kong way

Righting Wrongs (1986).

While revising Planet Hong Kong for its web edition, I’ve been revisiting classic Hong Kong action scenes. In 1997-98, when the book was written, I had to rely on laserdiscs, but since then I’ve been able to look at more 35mm prints. (DVDs usually don’t help answer the sort of questions I’m asking, for reasons reviewed here.) Now I have a chance to put some thoughts about these movies online, in this blog and in the upcoming digital update of the book. As a start, here’s a recipe drawn from the best of Hong Kong fury.

First, go for clarity in every way. Not murky earth-toned sets but brightly colored and sharply lit ones; even an alley can dazzle. Put the camera on a tripod; pan if you must, but save your dolly moves for simple emphasis. No handheld.

Second, aim for precision. Stallone’s comments imply that a cameraman captures a preexisting fight, snatching an “interesting” shot here or there. But that’s not the case. Movie action is choreographed and the framing is calibrated to that. The gestures should be legible, favoring crisp and staccato movement, while the image’s composition aims to convey the action cleanly. It’s a pity that the haphazard framing of Stallone and his cameramen have ruined the choreography of Cory Yuen Kwai, Jet Li’s action designer (and a fine director in his own right).

Third, establish a rhythm. This involves not only building the fight. It also involves synchronizing the pace of characters’ movements with that of the cutting. On the whole, the old rule applies: More distant shots should be held longer than closer ones. This doesn’t mean you can’t use fast cutting, only that your fast cutting can be more finely judged when you take shot scale, composition, and speed of movement into account.

Rhythm means sensing a pulse, and for that you need slight pauses. So don’t cut away to something else before a punch or kick is completed. Let the arc of movement, itself perhaps stretched over several shots, come to a point of rest, if only for a couple of frames.

Fourth—and here is where realism is most explicitly abandoned—amplify the expressive qualities of the action. If movement is zigzag or springy or oscillating, stress that. Give emotional qualities not only to facial expressions but also to postures and combat moves. American heroes just grimace while their bodies remain inexpressive, lumpish. The hard guys in The Expendables might as well be made of granite. But in contrast your fighters needn’t wave their arms wildly. Just concentrate energy and emotion in the action. If the hero attacks, let him become as focused as a javelin. If your heroine falls, don’t let her just drop out of frame: Let her land with a thwack, preferably on the spine or neck, and let her body’s recoil send a spasm through the spectator too.

Hong Kong cinema supports Sergei Eisenstein’s belief that expressive human action is “infectious.” He thought that if physical action onscreen is imbued with vivid force it can arouse sympathetic echoes in the spectator’s own body. After a great action scene, such as in many Chang Cheh and Lau Kar-leung films of the 1970s, or in Yuen Kwai’s Righting Wrongs, when a tough guy gets a spittoon in the face, the viewer feels trembling and tired, but in a good way.

Glass story

Jackie Chan has become such a beaming, easygoing star that we forget that he was an excellent director of brutal fight scenes. He proved adept at filling anamorphic compositions with dynamic movement, as well as plucking out items of a set and sweeping them into the action. (See the parlor fight in Young Master, 1980, or the shenanigans in the rope factory in Miracles/ Mr. Canton and Lady Rose, 1989). In Police Story (1985), Jackie is trying to rescue Salina and save all the computer records in her briefcase. Koo’s gang is determined to stop him. The fight moves through different areas of a shopping mall.

In each of these locales, Jackie plays a suite of variations on what you can do with escalators, staircases, and, most memorably, glass. I can’t do justice to all the skirmishes, but consider some instances of how he stages and cuts the action for an impact that American movies seldom achieve.

The variations get steadily more elaborate. Early in the sequence, Jackie flings one thug, achingly, across the bottom handrails of an escalator.

The shot could hardly be more legible. You see everything. Next, Jackie is grabbed from the rear.

Naturally he has to flip his attacker down to the floor below, rendered in two dynamic shots from directly below and above.

Interestingly, the shots are so clearly composed (even with the fancy mirror effect in the second) that they can be very brief: 26 frames and 16 frames. Down at the bottom, the unfortunate fellow smashes through a display and lands straight on his spine. Unlike the security guards in Tomorrow Never Dies, this thug gets a little commiseration as he rolls over groaning. As in any fight sequences, disposable thugs may come back into action, but at least we’ll clearly see the fates of those who are put permanently out of commission.

After this burst of action Jackie provides a pause as he abruptly looks up in search of Salina.

What else can you do with escalators? How about tossing the next thug down the slim gap between two of them?

In a nice touch, we hear a long squeak as he slides down the trough.

Tomorrow Never Dies sets up its conveyor-belt climax straightforwardly, but Jackie’s choreography is more surprising. Audacious and imaginative as the stunts are, however, they are framed and cut in a way that makes the action clear and precise. Through cinematic choices Chan builds up an infectious arousal. This stuff hurts.

After a set-to in a hallway, Jackie pursues the gang into an area filled with display cases. He takes on the men ferociously, and sets them smashing through the vitrines in another string of variations. Jackie slams down a mirror on one thug, swings another into a display, and sends one spinning through a window. Each shot, of course, is of diagrammatic simplicity, all the better to amplify the expressive dimension and key up the viewer. You can’t watch shots of men hurled into layers of glass without feeling a few palpitations.

Nearly every shot is bound tightly to the next. What will occupy shot B is launched on the fringes of shot A, sometimes for only a few frames. The string of matches on action creates a fluid continuity quite different from the choppiness we often find in American sequences.

A good instance occurs after Jackie has been pinned under a toppled shelf. In a medium close-up, the gang leader orders his thug into action; behind him the plaid-coated thug moves left.

In long shot, with Jackie at a disadvantage, the thug continues his movement in the background as he grabs a heavy statuette.

In a medium-shot, Mr. Plaid Jacket lifts the statue, but as he moves aside he reveals Salina rushing toward him in the background. Look quick: She appears in the fifteenth frame, and is gone within another fifteen.

We can only glimpse Salina passing behind the thug, but the next shot shows her clearly: running, baseball bat in hand, toward him. The trajectory could not be clearer, and she swings the bat directly through the vitrine.

The force of the action is multiplied by the simplest cut possible: an axial enlargement, with the action slightly repeated and slowed. The first shot of Salina’s swing lasts seventeen frames, the second exactly twice as long. The arithmetic of the cutting extends the action’s beat.

Bursts of glass form the dominant, painful motif of this part of the sequence. (Jackie’s crew suggested he call the film Glass Story.) The shifting dynamic of the fight is rendered through close encounters of the splintery kind. But these are differentiated. Long shots portray the torments of the gang, but Jackie’s first encounter with glass is treated in one simple close shot, just a second long, that usually makes audiences flinch.

Jackie is attacked by the gang leader and he shoves Salina out of the way.

The leader springs forward to whack Jackie with the briefcase.

Cut to the opposite angle, a tight shot of Jackie.

The briefcase continues to be swung, and Jackie’s head smashes the windowpane.

Jackie bounces off the glass and grimaces in agony.

The proximity of the glass shards to his eyes probably triggers some primal revulsion in us, but this is only part of the image’s force. The whole shot lasts only 28 frames. I think that part of its percussive impact comes from the fact that at the start we don’t have time to register that the pane is there. (There are only seven frames before Jackie hits.) When the glass bursts, it’s as startling as if the screen surface has cracked as well, and this amplifies the painful impact of the blow.

For a time Jackie is at the gang’s mercy. But he makes a comeback, and eventually in a kind of summary of his other maneuvers he will bash the leader, body and head, through two glass cases. This phase of the scene concludes with Jackie running Mr. Plaid through a series of cases at the point of a motorcycle. Both crescendos are filmed in clear, smoothly-cut shots—and long shots at that.

We may wince for the fate of these gangsters, but we shuddered when we saw Jackie’s face knocked through a window. Soon Jackie will be flipping the leader down an escalator, a sort of envoi to the scene’s first phase, and he will be sliding down a three-story light pole to catch up with boss Koo himself.

To use Stallone’s comparison, I’d happily hang this splendid sequence in the Louvre.

But what sort of MPAA rating would it receive today? The painful physicality on display is given a staccato force through the framing and cutting. And don’t call it cartoonish. It’s Bond who’s cartoonish, with his unflappable ease and perfectly functioning gadgets and defiance of the laws of gravity and those fights he wins without suffering a scratch. Jackie shows us the sweat. He and his victims fall with painful awkwardness, he gets gashed and bruised, and he’s all too vulnerable to physics (or at least Hong Kong physics). Bond wins through debonair resourcefulness and a lot of luck. Jackie wins by refusing to lose.

He refuses to lose the audience too. In Police Story Jackie’s manic urge to make the scene maximally gripping is itself a little scary. Nonetheless, when a director isn’t afraid of tapping the real power of movies, a fight scene can give us an adrenalin transfusion. Who needs 3-D? Maybe only weak directors.

For other discussions of Hong Kong action scenes, see my “Aesthetics in Action: Kung-Fu, Gunplay, and Cinematic Expression” and “Richness through Imperfection: King Hu and the Glimpse” in Poetics of Cinema. There are some other examples in my online essay on Shaw Brothers. My most ambitious efforts in this direction are in Planet Hong Kong, where I take up the issue of rhythm in more detail than I can here. Alas, many contemporary Hong Kong action scenes have learned bad habits from Hollywood. I’ll talk about the decline of crisp fight staging in the new edition of PHK, due online in early December.

Todd McCarthy’s 1998 review of Armageddon is here. Peter DeBruge’s review of The Expendables is here. Both may lurk behind a paywall. The coverage of The Expendables I mention is Michael Goldman, “War Horses,” American Cinematographer 91, 9 (November 2010), 52-56. The pilot online issue is here.

The Dragon Dynasty version of Police Story includes Bey Logan’s conversation with Brett Ratner. During the commentary, Ratner notes that Jackie holds his shots longer than would an American director, who would be likely to cut on every punch. Incidentally, I’ve found many DD releases of Hong Kong films to be superior in quality to other DVD versions, and Logan’s commentaries are information-packed. His book Hong Kong Action Cinema remains a fine piece of work.

The images from Tomorrow Never Dies are taken from DVD, with all the drawbacks of that format for close analysis. But I don’t think my conclusions would vary if I worked from 35mm. The Police Story frames are analog frame enlargements from a 35mm print and allow accurate frame-by-frame analysis. Even then, Jackie’s pacing is so fast that blurring is inevitable. Thanks to Heather Heckman for her assistance in turning my slides into digital files.

PS 17 September 2010: I forgot to mention that Matt Zoller Seitz has provided two of the most discerning (and hilarious) critiques of the Michael Bay High Rococo Action Style, here and here.

Young Master.