Archive for the 'Film technique: Cinematography' Category

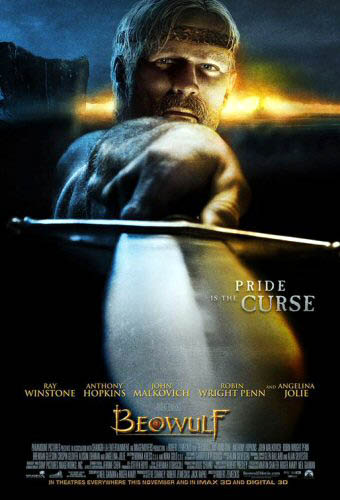

Bwana Beowulf

KT: I do not understand Beowulf. I don’t understand why the director who made one of the great modern Hollywood films, Back to the Future, and several very good ones, including Who Framed Roger Rabbit? and Cast Away, now has this fixation with creating nearly photo-realistic 3D digital images.

DB: I think that on the whole Zemeckis’ films have become weaker since Bob Gale stopped working with him. I like the sentiment of I Wanna Hold Your Hand and the crass misanthropy of Used Cars, and I think the Back to the Future trilogy mixes both in clever ways. But now almost every Zemeckis film seems to be less about telling a story than solving a technical problem. How to best merge cartoons and humans (Roger Rabbit)? How to push the edge of spfx (Death Becomes Her, Forrest Gump, Contact)? How to make half a movie showing only one character (Cast Away)? There’s a stunting aspect to this line of work, though I grant that it can lead to technical breakthroughs, as in Gump.

KT: I also don’t understand why most of the supposedly state-of-the-art effects technology looks distinctly cruder than the CGI in The Lord of the Rings, the first part of which came out six years ago. I don’t understand why studios that are trying to push 3D to a broad audience make a film with silly action aimed at teenage boys. That’s an OK strategy when you’ve got a $30 million horror film, but a budget of $150 million demands a lot broader appeal.

DB: And the evidence so far indicates Beowulf doesn’t have that appeal. The obvious comparison is 300, from earlier this year. According to Box Office Mojo it cost about $65 million to make, but it reaped $70 million domestically in its first weekend and wound up with $450 million theatrically worldwide. Beowulf grossed $27.5 million in its first US weekend and currently sits at about $146 million worldwide. I’d think that this has to be a disappointment. Recall too that the Imax screenings have higher ticket prices, so there are fewer eyeballs taking in Angelina Jolie’s pumps, braid, and upper respiratory area.

In addition, sources suggest that a 3-D version of Beowulf will not be available on DVD, so the sell-through takings—the real source of studio profit—may be significantly smaller than average.

KT: It seems to me that the people who are pushing 3-D so hard and hoping for it to become standard in filmmaking are forcing it on the public too soon. It’s still fiendishly difficult and expensive to shoot live action material in digital 3-D, so most projects are animated. One approach, taken in Beowulf, is to motion-capture real people and animate the characters to make them appear as much like the real people as possible. The problem is that they still have a weird look about them, like moving dolls. People have complained about the dead-eyed gaze of the characters in The Polar Express, and though there’s apparently been an improvement between the two films, the eyes don’t always look as though they’re focusing on anything. It can be done, though; the extended-edition Lord of the Rings DVD supplements about Gollum show how much effort went into making his eyes have a realistic sheen and flicker.

I was also struck by how clunky some of the animation looked. Beowulf is supposedly state of the art, and it certainly had the budget of a major CGI film. Yet some of the rendering and motion-capture was distractingly crude. I noticed that particularly on the horses. Their coats looked pre-Monsters, Inc., and their movements at times reminded me of kids rocking plastic toys back and forth. I suspect this effect had something to do with a lack of believable musculature. If you look at the way the cave troll was done in The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring (again, demonstrated in the DVD supplements), there was a specific program to simulate the way muscles move on skeletons, even the skeletons of imaginary creatures. Now, six years later, we see these things that look like hobby-horses—and that all run alike.

The backgrounds were often strange as well, simple and flat-looking, like painted backdrops. There were some exceptions, with the seascapes and rocky crags pretty realistically done. But just plain hillsides and groups of tents and so on looked almost sketchy in comparison with the moving figures, and I noticed that at times some fog would be put in, presumably to cover that problem up. There certainly was some very good animation as well, most notably the dragon, but there was no consistency of visual style.

DB: I’d go farther and say that 3-D hasn’t improved significantly since the 1950s. It ought to work: just replicate the eyes’ binocular disparity by setting two cameras at the proper interval or, now, by manipulating perspective with software. Yet in films 3-D has always looked weirdly wrong. It creates a cardboardy effect, capturing surfaces but not volumes. Real objects in depth have bulk, but in these movies, objects are just thin planes, slices of space set at different distances from us. If our ancestors had seen the world the way it looks in these movies, they probably wouldn’t have left many descendants.

It would take a perceptual psychologist to explain why 3-D looks fake. Whatever the cause, I’d speculate that good old 2-D cinema is better at suggesting volumes exactly because the cues to depth are less specific and so we can fill in the somewhat ambiguous array.

By the way, in watching a 3-D movie I seem to go through stages. First, there’s some adjustment to this very weird stimulus: I can’t easily focus on the whole image and movement seems excessively fuzzy. Then adaptation settles in and I can see the 2 ¼-D image pretty well. But adaptation carries me further and by the end of the movie I seem to see the image as less dimensional and more simply 2-D; the effects aren’t as striking. But maybe this is just me.

Back to the Future, or at least 1954

DB: I’d like to think about it from a historical perspective for a while. The industry seems to be repeating a cycle of efforts that took place in 1952-1954. The American box office plunged after 1947 as people strayed to other entertainments, including TV, and so the industry tried to woo them back with some new technology. Today, as viewers migrate to videogames, the Internet, and movies on portable devices, how can theatres woo their customers? Answer: Offer spectacle they can’t get at home.

Beowulf brings together at least three factors that eerily remind me of the early 1950s.

(1) Obviously, 3-D. The first successful 3-D feature era was Bwana Devil, released in November of 1952. It was an uninspired B movie, but it launched the brief 3-D craze. Columbia, Warners, and other studios made major pictures in the format, most notably House of Wax (1953). But costs of shooting and screening 3-D were high, with many technical glitches, and apart from novelty value, the process didn’t guarantee a big audience. The fad ended in spring of 1954, when all studios stopped making films in the format.

The process has been sporadically revived, notably in the 1980s (Comin’ at Ya, Jaws 3-D) and once more it fizzled. So, ignoring the lessons of history and chanting the mantra that Digital Changes Everything, we try it again.

(2) Big, big screens. In September of 1952, Cinerama burst on the scene with its huge tripartite screen and multitrack sound. It attracted plenty of viewers, but it could be used only in purpose-built venues. Like 3-D, its technology could never replace ordinary 35mm as the industry standard. The contemporary parallel is Imax, which though very impressive will not replace orthodox multiplex screens—too expensive to install and maintain, pricy tickets. Like 3-D, it’s a novelty. (1)

(3) The sword-and-sandal costume epic. It’s a long-running genre, but it got significantly revived in the late 1940s. It was a logical input for the new technologies of widescreen—not Cinerama but more practical offshoots that gained more general usage.

From the standard-format Samson and Delilah (1949), David and Bathsheba (1951), and Quo Vadis (1951) it was a short step to The Robe (1953) and The Egyptian (1954) in CinemaScope, The Ten Commandments (1956) in VistaVision, The Vikings (1958) in Technirama, Hercules (1959) in Dyaliscope, Solomon and Sheba (1959) and Spartacus (1960) in Super Technirama 70, and Ben-Hur (1959) in anamorphic 70mm Panavision. It is, incidentally, a pretty dire genre; the peplum might be the only genre that has given us no great films since Cabiria (1914) and Intolerance (1916).

In parallel fashion, the revival of the beefcake warrior film with Gladiator (2000) coincided with innovations in CGI and thus furnished new forms of spectacle for Troy (2004), Kingdom of Heaven (2005), and 300 (2007). This trend paved the way for Beowulf. When screens get bigger, Hollywood hankers for crowds, oiled biceps, big swords, and nubile ladies in filmy clothes. Not to mention soundtracks with pounding drums, wailing sopranos, and choirs chanting dead or made-up languages. And the conviction that Greeks, Romans, and those other ancient folks spoke with British accents. The innovation of Beowulf is to turn a Nordic hero into a Cockney pub brawler.

In other words, it’s 1954 again. So if we ask, Will it all last? I’m inclined to answer, Did 1954?

KT: Yes, the studios see the new technology as one more way to lure people away from their computers and game consoles and into the theaters. Maybe that will work to some extent. There’s no doubt that a lot of the people who have seen Beowulf have praised it as a fun experience and as having effectively immersive 3-D effects. I’m surprised at how many positive comments there are on Rotten Tomatoes, where the average score from both amateur and professional reviewers is 6.5 out of 10. That’s not exactly dazzling, but it’s a lot higher than I would give it.

Even so, the film hasn’t lured all that many people away from their other activities. You’ve mentioned that Beowulf hasn’t done all that well at the box-office. It did much better in theaters that showed it in 3-D. If it hadn’t been for the 3-D gimmickry, it would probably have been dead in the water from the start. And if 3-D effects remain on the level of gimmickry, they will soon wear out their welcome. Presumably the people who have been going to Beowulf are to a considerable extent those who are already interested in 3-D, and I can’t believe there are huge numbers of people really passionate about the idea of someday being able to watch lots of films in 3-D. If more films like Beowulf come out—ludicrous, bombastic action with distracting animation problems—they’re not likely to make the prospect any more attractive.

Eventually somebody—James Cameron or Peter Jackson, perhaps—will make the first great 3D film, and then maybe the passion will spread.

3-D in 2-D

DB: I’m doubtful that there will ever be a great 3-D film, and especially from those directors. But one last historical note.

I think that ordinary mainstream cinema has been setting us up for the flashiest 3-D flourishes for some time. One of the goals of the Speilberg-Lucas spearhead was to amp up physical action, to make it more kinetic, and this often showed up as in-your-face depth. Spielberg used a lot of deep-focus effects to create a punchy, almost comic-book look, and who can forget the opening shot of Star Wars, with that spacecraft arousing gasps by simply going on into depth forever? Seeing the movie in 70mm on release, I was struck by how the last sequence of Luke’s attack mission was maniacally concerned with driving our eye along the fast track of central perspective. Did it foreshadow the tunnel vision of videogame action?

In any case, I think that aggressive thrusting in and out of the frame was integral to the style of the new blockbuster. Since then, our eyes have been assaulted by plenty of would-be 3-D effects in 2-D. In Rennie Harlan’s Driven (2001), the crashing race cars spray us with fragments.

Jackson is definitely in the Spielberg line, favoring steep depth and big foreground elements. In King Kong, the primeval creatures lunge out at us, heave violently across the frame, and fling their victims into our laps.

Such shock-and-awe shots recall American comic-book graphics. These affinities are at the center of 300, as we’d expect. For example, a cracking whip curls out at us in slow motion, like a two-panel series.

Beowulf draws on this thrusting imagery, but inevitably it doesn’t seem fresh because so many 2-D films have already used it. Maybe the most original device is having the camera pull swiftly back and back and back, letting new layers of foreground pop in and shrink away. This is viscerally arousing in 3-D, but aren’t there precedents for it—in the Rings, in animated films, or some such?

Zemeckis tries to transpose into 3-D the style of what I’ve called, in The Way Hollywood Tells It, intensified continuity. This style favors rapid cutting, many close views, extreme lens lengths, and lots of camera movement. I found Zemeckis’ restless camerawork even more distracting than in 2-D. So I’m wondering if current stylistic conventions can simply be transposed to 3-D, or do directors have to be more imaginative and make fresher choices?

KT: That pull-back effect may be viscerally arousing, but in Beowulf it was usually pretty gratuitous and, for me at least, it called attention to itself in a way that was often risible. I don’t think there’s anything in Rings as crude as the shots in Beowulf that you’re talking about. In the opening scene of the latter, in the mead-hall, the camera zips into the upper part of the room, with rafters, chains, torches, and even rats whizzing in from the sides of the frame. None of that contributes to the narrative.

The flashiest backward camera movement, or simulated camera movement, I can think of in Rings is the one in the Two Towers scene where Saruman exhorts his army of ten thousand Uruk-hai to battle. The final shot is a rapid track backward through the ranks of soldiers holding flag poles. The point is to stress the enormous numbers of soldiers. There’s no gratuitous thrusting-in of set elements from the sides, just the cumulative effect of so many similar figures. The simulated camera also at one point “bumps” one of the flagpoles, causing it to wobble, but I take it that that’s an attempt to add a certain odd realism to the “camera” movement, not a knowing nudge to the audience. In Rings, the virtual camera usually follows action rather than moving independently through space. It tends to go forward or obliquely rather than backward.

As to transferring classical Hollywood style to 3-D or finding a whole new set of conventions to fit 3-D, Beowulf offers an object lesson. It uses a combination of the two. At times we have conventional conversations using shot/reverse shot, and at other times we have the swoopy-glidey style you described, with the camera zipping around the space and trying to see it from every angle within a few seconds.

The odd thing is, neither one works. The very close shot/reverse shot views of the digital characters make them look unnatural and emphasizes the not infrequent failure of their eyes to connect with each other. The swoop-glidey camera movements are silly and don’t stick to the narrative.

I’m not optimistic enough to think that directors can come up with a whole set of “fresher stylistic choices” to make 3-D work. Maybe Sergei Eisenstein, with his meticulous attention to every aspect of such topics, could have thought the issue through, but his solution would probably not be viable for the Hollywood studios. My own thought is that directors working in 3-D should probably stick to classical Hollywood style and avoid flashy stylistic effects. So far, the more blatantly 3-D something looks on the screen, the less it makes 3-D seem like something we want to watch on a regular basis. Think of the best films of this year: Zodiac, The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford, Ratatouille, Across the Universe, and so on. Would any of them be better in 3-D? Probably not.

Plus, I don’t like watching movies through something. Movies should just be the screen and you. The 3-D glasses are definitely better now than in the earliest days of the cardboard, red/green versions. Still, the Imax glasses we used in watching Beowulf were heavy enough to leave a groove on my nose. Make the mistake of touching the lenses, and you’ve got a blur on one half of your vision of the film. In short, I think that 3-D still has to prove itself, and Beowulf didn’t add any evidence.

(1) PS 9 December: DB: I originally added in regard to Imax: “It’s actually waning in popularity, except in newly emerging markets like China.” This disparaging comment was misleading. Yesterday I learned from Screen International that Imax recently signed a deal with AMC to install 100 systems in 33 US cities. Oops! Today Paul Alvarado Dykstra of Austin’s Villa Muse Studios kindly wrote to point out the Hollywood Reporter‘s coverage, which gives background on the costs of installing and maintaining an Imax facility.

I was, obscurely, thinking of the traditional Imax programming of travelogues and documentaries. I failed to register that these have been largely displaced by screenings of blockbuster features, catching fire in 2003 with The Matrix Reloaded and proving successful with The Polar Express and other titles. Imax is now largely an alternative venue for megapictures, and its seesawing financial performance may have been steadied by moving into the features market.

PS 26 December: Travel has delayed our timely linking, but we couldn’t neglect Mike Barrier’s in-depth critique of Beowulf here.

PPS 5 January 2008: Harvey Deneroff has a comprehensive and judicious discussion of the 3D situation here.

Sleeves

DB here:

Earlier this month, when I was giving a lecture on Mizoguchi Kenji at our university museum, I showed two images from A Woman of Rumor (Uwasa no onna, 1954). It’s a little-known film of his, and it’s probably not up to his finest, but seeing the stills again on the big screen made me want to write about one scene. That scene displays aspects of Mizoguchi’s artistry that I touch on in one chapter of Figures Traced in Light and in the website supplement here.

This blog entry constitutes, I suppose, another supplement. After all, I couldn’t include in the book all the moments in Mizoguchi’s work that I find fascinating. But since comparison is a good way to get under a movie’s skin, my examination of a parallel scene from another movie may have more general interest. Even though Woman of Rumor doesn’t seem to be available on video, maybe looking at this pair of examples would inspire some readers to take an interest in one of the two or three greatest filmmakers who ever lived.

In the court of Regina

William Wyler and John Barrymore.

What a year 1941 was in the American cinema! We remember it for Citizen Kane but it also brought us How Green Was My Valley (a better film than Kane, I think), and items like Sergeant York (the biggest box-office hit), Dumbo, The Philadelphia Story, Suspicion, Ball of Fire, High Sierra, The Lady Eve, Meet John Doe, The Maltese Falcon, They Died with Their Boots On, and one of the most daring movies ever made in America, The Little Foxes.

An adaptation of Lillian Hellman’s play, The Little Foxes offers a study in unbridled capitalism. It shows how economic interests pit the South against the North and white against black. Psychologically, it analyzes a household gripped by the ruthless domination of the matriarch Regina (Bette Davis), the wiliest member of a family of grasping entrepreneurs. Regina has all but flattened her husband and is trying to make her daughter Alexandra oblivious to the family’s corruption.

The Little Foxes was also bold in its style—in its own way, as venturesome as Citizen Kane. It hasn’t been fully appreciated because Wyler is still thought of as a rather middlebrow talent, an overcautious director who toned down the flamboyance of Gregg Toland’s deep-space and deep-focus compositions.

Some day I hope to blog in defense of Wyler, middlebrow movies, and Midcult art in general. That would involve a detailed analysis of Little Foxes. (1) For now let’s just say that Wyler’s direction of the film won the admiration of no less than André Bazin. Bazin taught us to appreciate Wyler’s work, though with some prompting from Wyler and Toland (as I suggest here). Wyler was also appreciated by Mizoguchi, who, apparently grudgingly, told his screenwriter Yoda that he admired Wyler’s use of the “vertical frame.” (2) Later I’ll suggest one way of understanding that phrase. Mizoguchi met Wyler at the 1953 Venice Film Festival, when Ugetsu Monogatari was up against Wyler’s Roman Holiday for the Silver Lion.

One scene not discussed by Bazin or Mizoguchi, as far as I’m aware, has always gripped me. Regina’s brother Oscar has a wife, Birdie, who has turned into a passive alcoholic. Birdie has learned of plans to marry Xan off to Leo, her shallow son. Her will has been broken by Regina and Oscar, but she summons up the courage to blurt out to Xan that she mustn’t marry Leo, no matter how strongly the family insists. Xan, who has no inkling of how her family twists people to suit their ends, protests that no such thing could happen. But Oscar overhears Birdie warning Xan off.

Birdie and Oscar are about to leave at the end of the evening. Wyler begins with a standard two-shot, very slightly off-center. But as Birdie frantically warns Xan, Oscar’s sleeve and pant leg appear in the lower left of the frame, with the swagged curtain at the doorway hiding his face.

For us, this creates suspense. Only after Birdie has babbled out her warning do the two women notice he’s there. Xan, not knowing how Oscar abuses Birdie, heads off to bed.

As she climbs the staircase (very important in the film and the original play, this staircase) and heads off to her bedroom, Wyler’s camera arcs to reveal Oscar. Wyler now cuts to show, more or less from Birdie’s point of view, Xan going into her room.

Birdie watches anxiously, then turns to face Oscar, with a look of resigned apprehension.

Again suspense: Oscar won’t punish Birdie with Xan watching, but the girl’s departure puts Birdie in jeopardy. In addition, Wyler’s shot of her reaction anticipates the wrath she’ll face. (Patricia Collinge’s fluent performance is equal to the dynamics of Wyler’s visuals.) These cuts anchor our empathy; Wyler has been saving the close-up of Birdie for this moment.

We return to the master framing as Birdie heads toward Oscar, passing into a patch of shadow. As she does so, he raises his hand abruptly.

Wyler cuts to a two-shot. Oscar slaps Birdie so hard she seems to bounce against the left frame edge. She cries out and then tries to stifle her voice—a psychologically apt gesture for this woman who muffles her sorrows throughout the film.

Again, Wyler daringly sets a key action off-center. The brutal discontinuity of the cut, which crosses the axis of action and sharply changes shot scale, accentuates Oscar’s violence. It’s also rather elliptical; run the cut slowly, and you never see his hand strike her.

Xan hurries out of her room and comes to the banister, her face on the upper right balancing the placement of Birdie’s in the prior shot. In the next shot, we see, over her shoulder, Oscar stride out. Birdie follows meekly, assuring Xan that nothing’s wrong. The coda of the scene will emphasize Xan’s puzzled anxiety, a phase in her process of coming to understand the domineering fury that rules her family.

Low- and high-angle shots like this last pair recur throughout The Little Foxes, and I suspect that these are the sorts of thing Mizoguchi was invoking in mentioning Wyler’s “vertical” space. Wyler’s steep angles activate upper areas of the frame that many American directors hadn’t explored.

The act of overhearing a revealing conversation is a standard dramatic convention, but Wyler has refreshed and nuanced it. We know how it would be normally handled. We’d see either a shot showing Oscar stepping fully into the background, or a series of cuts showing first Birdie and Xan and then Oscar listening and watching. Wyler revises the standard schema, taking it for granted that we can pick up on a subtler cue than usual: just a bit of Oscar’s body intrudes.

As a result we have to be more alert. The information isn’t centered, but rather tucked into the lower left. And this option conceals Oscar’s face. Not that we’re doubting he’s angry, but delaying showing his anger builds up greater tension. Wyler, unlike today’s directors, knows when to build up to revealing things that we anticipate, making the final outburst more forceful when it comes. Further, the rest of the scene continues to deny us a clear view of Oscar’s anger, all of which gets squeezed into his gesture of slapping Birdie. It’s Birdie’s reaction that Wyler stresses, and Oscar’s contempt for her is conveyed simply by his bearing, his gesture, and his manner of stalking out of the foyer.

It’s not too much to talk about rigor here. The schemas dominating today’s filmmaking, the stylistic paradigm I call intensified continuity, would demand tight close-ups of everybody from the start. But providing them would make it harder for Wyler to raise the emotion when the startling slap comes. Maybe a contemporary director would render this spike in slo-mo, or with a wobbly handheld camera, but that tends to seem overbearing and pumped-up—as a lot of current stylistic pyrotechnics do. In any case, I’m betting that no American director today would use Oscar’s sleeve in the quietly ominous way Wyler does.

Mizoguchi’s game of vision

Mizoguchi Kenji, in glasses, during the making of Ugetsu.

Mizoguchi is renowned for his long takes, which are often sustained in distant views featuring considerable camera movement. In the Mizo chapter in Figures Traced in Light, I suggest that these stylistic choices spring from his effort to engage the viewer mesmerically—as he put it, “to work the viewer’s perceptual capacities to the utmost.” He asks us to downshift our attention to the finest details of the action, which he then modulates for expressive effect. I draw examples from various films across his career to show how he creates drama out of remarkably slight differences in character position, lighting, and other factors.

But what happens when he foreswears virtuoso camera movements and single-take scenes and breaks the drama up into several shots? Today, many ambitious directors seem to take pride in stretching out their takes, so cinephiles are sometimes inclined to see a cut as a loss of nerve and a concession to the audience. But I try to show in Figures that Mizoguchi sustains his concern for nuance when he creates an edited sequence. The modulation of fleeting details is to be found in his closer shots too.

In A Woman of Rumor, Hatsuko runs a teahouse that funnels customers to the geisha establishment behind it. She has tried to protect her daughter Yukiko from the shame of her profession. Hatsuko has also been cultivating a young doctor she hopes to marry, giving him money to set up a clinic. Now the doctor, Matoba, has become attracted to Yukiko. The scene I’m examining takes place during the performance of a noh drama. Hatsuko leaves the auditorium and finds Yukiko talking with Dr. Matoba.

As she passes around a screen, she hears Yukiko saying she wants to learn piano in Tokyo. Hatsuko looks left, and Mizoguchi cuts to an approximation of her optical point of view on the couple in the lounge.

So far, so conventional. Mizoguchi seems to follow the intercutting option for treating a scene of overheard conversation. But he goes further. Having laid out the action, Mizoguchi starts the lesson in just-noticeable-details . . . with a sleeve. He cuts to a reverse shot putting Matoba and Yukiko in the foreground. Hatsuko is still back there, though. We can see her kimono sleeve on the left, poking out from behind the screen.

A sharp-eyed viewer might also spot Hatsuko’s shadow on a wall, in the center of the shot, over Matoba’s shoulder. This blow-up shows both the sleeve and her silhouette.

Here, friends, is one reason we want to watch films in 35mm, and projected really big.

It’s now that Yukiko says that she may leave her mother, and Matoba replies, “Maybe I’ll go too.” This is devastating to Hatsuko. The two people whom she loves most seem to care nothing for her. Her shocked reaction is given in a medium-shot showing her shifting out from behind the screen, her face partially hidden.

Mizoguchi has picked one variant of the overheard-conversation schema: shot of speakers/ reaction shot of eavesdropper. But he’s done so in his own way, using the barely discernible kimono sleeve to signal Hatsuko’s presence in the full shot of the couple. Likewise, the shot of Hatsuko listening is far from the usual close-up. Like other Japanese directors, Mizoguchi was fond of this arresting single-eye image. He used it earlier in his career, as shown in the first frame at the top of this entry, from Hometown (Furusato, 1930). The second frame is the last shot of his last film, Street of Shame (Akasen chitai, 1956). Quite a shot to end your career on, I’d say.

Most Japanese directors use this single-eye framing as a one-off flourish, but not Mizoguchi. The device epitomizes his demand that we concentrate on a detail. Isolating half a face gives impact to the slightest shift in the eye and eyebrow. Moreover, the split face reappears as a pictorial motif later in the scene.

As Matoba says he’ll go back to Tokyo for his doctorate, Mizoguchi cuts back to the setup for the second shot. Hatsuko moves left to sit on a chair around the corner from the sofa. This prepares for another, more prolonged game of visibility.

Now we get a thirty-second take of the couple on the sofa. As the scene develops, it becomes evident that Matoba is seducing Yukiko. Hatsuko slips in and out of visibility, her actions responding to and even echoing Matoba’s pressure on the girl. First, as he talks with Yukiko, we see Hatsuko’s sleeve and shoulder, between the vase and his shoulder. But as he slips his arm around Yukiko, her elbow moves aside, in an echo of his gesture.

Then, when Matoba presses his attention (“We’ll help each other . . . Depend on me”), Hatsuko’s face pops into view as her fingers emerge to grip the edge of her chair. Mizoguchi then lets her face subside, again slicing it in half.

In effect, this shot replays and expands upon the tactic governing the earlier two shots. Again we get the just-noticeable presence of the sleeve, but now rhyming with the action in the foreground. And again we get the facial reaction, impeded by a vertical cutoff, but this time in the distant shot rather than in a closer view. It turns out that those first four shots were training us for this more intricate game of vision.

At the moment Hatsuko’s face is sliced in half, Mizoguchi cuts. Now he prolongs the close view as he had extended the full shot of the couple. In this thirty-second shot, we watch her reaction, played out in slight modulations—changes in her facial expression, changes in the aspect of her face that we see, and changing relations to the curling palm plant in the vase before her.

We get a new angle on Hatsuko, slightly high, as Matoba says, “I’ll tell her.” Hatsuko stands up abruptly and the camera tilts to follow her.

With the simple action of her rising up, Mizoguchi changes his composition sharply. Hatsuko’s position in the frame changes only a little bit, but the massive vase on the left gives way to the curling stalks on the right. Radically refreshing a shot through minimal means is one felicity of Mizoguchi’s art.

Then, as if the full import of Matoba’s betrayal dawns on her, Hatsuko lowers her head sadly. Again her eyes are split up, this time thanks to the twisting stalk. In a characteristic Mizoguchi gesture, she turns from the camera, as if ashamed to face us, but also summoning up reserves for the next emotional shift.

When she turns back, her face burns.

I take this to be the scene’s emotional climax. Mizoguchi could have given it to us much sooner, by having Hatsuko turn angry as she peeped out from behind the screen. Instead, his game of vision allowed him to build patiently toward this unimpeded shot of her reaction. It prepares us for the next stages of the drama, later scenes in which she will confront her patron and launch jealous accusations at Yukiko.

Now we hear the performance ending, and Hatsuko lifts her head. This phase of the scene ends when Mizoguchi cuts to audience members coming into the lounge and greeting her.

By 1954 Mizoguchi had surely seen The Little Foxes. Had he decided to redo Wyler’s virtuoso staging in his own manner?

Both directors work with similar ingredients: overheard conversation, depth shots, judicious close-ups, and partial views. But the narrational weightings differ. Wyler’s film aligns and allies us with the people talking, whereas A Woman of Rumor ties us to the listener. (3) Wyler’s eight shots take eighty-one seconds; Mizoguchi’s eight shots take about two minutes.

Wyler’s handling is brisk, tense, and remarkably nuanced within the Hollywood tradition. Mizoguchi gives us his scene more sedately, wringing just-noticeable differences out of unassertive performances and simple elements of setting. No slap here, just a drama of wounded pride, lost love, and jealousy played out in the face, back, and sleeve of Tanaka Kinuyo, shifting behind a floral arrangement. What Wyler gives us as one sharp effect, Mizoguchi turns into a delicate, prolonged game of vision.

Am I fussing over minutiae? No; Wyler and Mizoguchi did. We just have to follow where they lead. As I try to show in my essay on blinking in cinema (4), directors attend closely to things that might seem trivial. Our analysis needs to be as fine-grained as their craft and artistry.

Oh, yes: at Venice Ugetsu won the Silver Lion. Wyler had to be content with Roman Holiday’s three Academy Awards.

(1) I sketch some of the possibilities in On the History of Film Style (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1997), 225-227.

(2) For more on Mizoguchi’s competition with Wyler, see Figures Traced in Light (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005), 134.

(3) I’m referring to Murray Smith’s deft analysis of what he calls alignment and allegiance in our relation to film characters. See Engaging Characters: Fiction, Emotion, and the Cinema (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995), Chapters 5 and 6.

(4) “Who Blinked First?” in Poetics of Cinema (New York: Routledge, 2007), 327-335.

PS 3 December: Thanks to Michael Kerpan for a name correction, and for the information that Woman of Rumor was once available on a French DVD.

PPS 27 February 2008: Good news. Now Woman of Rumor is available on the wonderful Eureka! Masters of Cinema series, along with the superb Chikamatsu Monogatari. The discs come with voice-over commentary by Tony Rayns and essays by Keiko McDonald and Mark LeFanu.

Three nights of a dreamer

DB here:

The close-up blogathon launched by Matt Zoller Seitz is over, but it contains enough specimens and analyses for a hefty book. It also inspired Jim Emerson to devote a cine-lyric to the close-up. I missed the deadline, so I suppose that this constitutes my sideways contribution to Matt’s enterprise.

Sideways, because a full-blown analysis of In the City of Sylvia (En la ciudad de Sylvia; Dans la ville de Sylvie) would be a breach of decorum. Most people haven’t heard of this new film by José Luis Guerin, let alone seen it. I saw it at the Vancouver festival in September, and it will make its way through the festival circuit over the coming months and should show up on cable or DVD thereafter. But apart from calling attention to it as a remarkable film, I want to look at one of its most absorbing sequences and suggest some of its originality. Lee Marshall has already pointed out one of Sylvia‘s arresting features:

Guerin seems to have created pure drama without recourse to story. We’re always taught that story is the engine of drama. Not here: somehow Guerin has created an almost plotless film that has the dramatic tension of vintage Hitchcock. (1)

Although the story situation is slight, the tension we feel springs partly from vivid stylistic patterns. In other words: Minimal and uncertain story action is heightened by engaging visual narration. This narration in turn derives its power from one of the most traditional devices of filmic storytelling.

Consider the other person’s point of view

The point-of-view shot is a mainstay of cinematic storytelling, and its history is an intriguing one. Many of the earliest examples we have are motivated as views through optical gadgets. Two films by the Englishman G. A. Smith, both from 1900, handily show the options. Grandma’s Reading Glass justifies the point-of-view image as what the boy sees when he peers at granny through her big magnifier.

Smith’s As Seen through a Telescope motivates the cut-in POV shot as what our dirty old man in the foreground has an eye for.

Fairly soon, this use of the magnifying POV shot was mingling with more straightforward ones. In The Birth of a Nation (1915), D. W. Griffith offers a rough-edged example. When the Stoneman brother and sister visit Ford’s Theatre on the night of Lincoln’s assassination, we see Elsie pointing out the famous actor John Wilkes Booth.

Booth is framed in an iris, which Griffith often uses to underscore an important image. But when Elsie studies Booth through her opera glasses, Griffith, usually not fastidious about such things, supplies the same irised image, now doing duty for the sort of magnifier-masking we get in the Smith films.

Presumably a more consistent technique would show Booth in long shot first, without the iris, and reserve the optical masking for replicating the view through the opera glasses. This is what happens in Ernst Lubitsch’s Lady Windermere’s Fan (1926), which contains a sequence built entirely around crisscrossed character looks. (1)

The woman of the world Mrs. Erlynne arrives at the racetrack and creates a stir, causing many men to watch her from all over the grandstand.

Note that Lubitsch has gone beyond Griffith by fitting the angle of Shot B to the viewer’s orientation, looking up. There are so many POV shots that at one point Lubitsch simply shows her from different angles and deletes the shots of each watching man.

This is a fascinating example of a process we often see in stylistic history. An “overlearned” visual convention can be treated elliptically; the filmmaker can leave out bits and we’ll fill them in. The binocular masking suffices to let us know that Mrs. Erlynne is being studied from afar. Moreover, Lubitsch gets an expressive bonus from being so concise. Now it doesn’t matter who’s watching, just that somebody is—actually, a lot of somebodies.

Later, after much more byplay with people looking at one another and misunderstanding what they see, Mrs. Erlynne sits down. Three gossips have been studying her, but now their view is blocked. So one gossip has to twist around to spy on her, and Lubitsch obligingly gives us a slightly tipped point-of-view framing—a full shot, without masking.

Adjusting her binoculars, the gossip is able to get a bigger view of Mrs. Erlynne, and she racks focus gleefully to catch a gray hair peeping out.

The visual narration in this sequence, already perfectly modulated, supplies the stylistic premise for Hitchcock’s Rear Window and all of its progeny, most recently Disturbia (2007). What might be overlooked is that by the 1920s the view through a device—field glasses, a microscope, a surveillance camera—had become a special, marked case. From then till now, the default POV pattern is the simple shot of a character looking, followed by an unadorned shot of what that person sees, from more or less the correct standpoint. Lubitsch’s sideways shot of the gossip’s view of Mrs. Erlynne, casually introduced, exemplifies the modern norm for presenting a character’s vision, and it’s so common that we seldom notice it.

POV shots: The basics

In his book Point of View in the Cinema, Edward Branigan itemizes the cues that the filmmaker can manipulate in creating a POV construction. (2) To simplify somewhat: Shot A shows a point in space and a character glance from that point. Shot B is taken from a camera position more or less approximating the point in A, and it shows an object. The shot-change presumes temporal continuity between A and B, and we assume as well that the character is aware of the object shown in B.

This seems like a complicated way of stating the obvious, but by teasing these elements apart, Branigan shows that each one can be manipulated in intriguing ways. For example, you can create a disorienting moment by violating the condition of temporal continuity. Ozu does this in Early Summer (1951), when Noriko and Aya decide to peek in at the man Noriko almost married. The two women tiptoe down a hall toward us as the camera tracks slowly backward. Ozu cuts to a forward-tracking shot that momentarily suggests a reverse angle POV on the corridor.

In fact, however, the camera movement is revealed to be the first shot of a new scene, among different characters, and we won’t ever see the man the two women went to spy on.

Here’s another interesting case, not cited by Branigan. In Halloween (1978), John Carpenter shows Laurie looking out a window and seeing Michael Myers in his mask, standing between fluttering washlines.

Cut back to Laurie, now frowning slightly.

Cut to a second POV shot; but now Michael has vanished.

This simple change in shot B’s object, Michael himself, has an uncanny effect. Did Michael just walk away from the washline? If so, this is an odd way to present it. Why not show him walking away? Alternatively, did he just disappear? Surely not; Laurie would be shocked. Carpenter wins twice over. Without obviously violating realism or directly showing that Michael has supernatural powers, he gives Michael the ability to come and go in a ghostly fashion. By the end of the film, when he miraculously disappears after a fall that would kill an ordinary person, we are prepared to believe that he is indeed, as Dr. Sam Loomis says, the Boogyman.

Who is Sylvia? What is she that all the swains commend her?

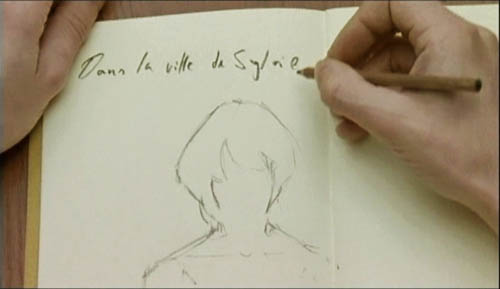

In the City of Sylvia centers on a young man staying at a hotel. We’re given no reason why he’s visiting the city, and no backstory about him. One day he’s sitting at a café. Now, across nearly twenty minutes of screen time he watches women and idly sketches them.

The sequence is a pleasure to watch, partly because of the constant refreshing of the image with faces, nearly all of them gorgeous, most of them female. Either Strasbourg has an extraordinary gene pool, or this café attracts only Ralph Lauren models. Yet the scene builds curiosity and suspense too, thanks to Guerin’s sustained and varied use of optical POV. He gives us an almost dialogue-free exploration of a cinematic space through one character’s optical viewpoint. (Stop reading here if you don’t want to know anything more about the film before you see it.)

The young man, known in Guerin’s companion film Unas fotos en la ciudad del Sylvia as the Dreamer, is almost expressionless as he scans the women’s faces. Slight shifts of his glance are accentuated by his habit of turning his head but keeping his eyes fixed. In over a hundred shots, Guerin uses some ingenious cinematic means to tease us into ever-greater absorption in the Dreamer’s visual grazing.

Fairly far into the sequence, Guerin gives us more or less the orthodox POV construction. The Dreamer looks at one woman at a table, and we see her return his look.

But here shot B isn’t really clean: the hands of the woman on the left sometimes block our view of the principal woman. This obtrusiveness is one of Guerin’s most basic strategies in the sequence. Inevitably, in passages before and after the cut I just showed, what the Dreamer is looking at is partially hidden in layers of faces and body parts.

Our prototype of the POV cut presumes a more or less single ‘point’ we are watching in shot B, but throughout this scene Guerin plays with this cue. He tantalizes us with several points to be observed, and he often obscures the most important ones. He also creates some startling juxtapositions. Near the very start we get this shot, which may or may not be the Dreamer’s POV.

By making the background girl seem to kiss the foreground guy, Guerin, as Eisenstein would say, “christens” his sequence. In effect, the image says: Watch out! Layered space will become important! When I saw this shot, I nearly jumped out of my seat.

The Dreamer is treated no differently, at least at the start. In most movies, the POV construction is set up with a clear, clean framing of our looker in shot A. Here, though, at the start of the scene Guerin peels away layers to get to our man. For the first six shots of the café, we don’t know he’s on the scene. Then he’s shown out of focus, in the background of more prominent action. The woman in the foreground has been primed to be the shot’s subject. At the moment she shifts her gaze and we try to read her expression, a second woman on the distant right shifts aside to reveal the Dreamer behind her.

Surely this is the most unemphatic entry of a protagonist we’ve seen in a while! Guerin is able to add planes to block the main ‘point’ of shot B because he’s working with long lenses, a crowded space, and careful choreography. Even focus plays a role, as in this case; our Dreamer is pretty hazy.

One upshot of this strategy is that we’re plunged into a “cubistic” space, in which slightly varied camera angles pick up bits of space we’ve seen in earlier combinations and oblige us to assemble it all in our head. Be thankful for the guy in the blue shirt above, for he plays an anchoring role in several setups that would otherwise float free.

It’s hard to convey in stills how much fascination and frustration that this teasing style creates. Like the Dreamer, we’re given only glimpses of the women, and even though we don’t know his purposes—is he just an artist in search of beauty? a serial killer picking out victims?—the partial views lure us at several levels. We try to complete the faces. We try to infer the women’s state of mind from their expressions and gestures, which are far more animated than our Dreamer’s.

And a search for story plays a part here. We’re primed for some action to start, and we browse through these shots looking for anything that might initiate it. Each face the Dreamer spots promises to kick-start a plot: when the Dreamer gets a full view of one of these women, perhaps things will get going.

Without giving away every detail, I’ll just say that the sequence has a strong visual arc as the Dreamer starts paying more and more attention to certain women. And just as he finally gets a full view of one fabulous face, his attention wanders to . . . another layer, this time one inside the café.

As he gapes at the woman inside, layers pile up, creating a cubistic climax of all the optical obstructions we’ve encountered.

The motif of reflections will take over the rest of the film’s visual design, and eventually we’ll see that some of the Dreamer’s drawings evoke the piled-up and sliced-up faces in the café shots.

Later in the film, the Dreamer will explain why he’s in the city and why he’s scanning women. We’ll have a tram ride that Guerin compares with Sunrise, and a scene in a music club that not only parallels the café sequence but evokes Manet. We’ll also have occasion to compare this film with Bresson’s Four Nights of a Dreamer, a citation signaled from the outset.

All that is to come. Even if the later scenes weren’t as compelling as they are, this café sequence would make Sylvia one of the most adventurous films I’ve seen this year. By revising the simple, long-lived POV schema, Guerin has made it yield fresh feelings and implications. Like Lubitsch’s racetrack scene, this imaginative sequence provokes the jubilation you feel in the presence of calm, precise artistry.

(1) Lee Marshall, “Past Perfect,” Screen International (19 October 2007): 27. The web version is here, but it may require a subscription.

(2) I analyze the visual narration of Lady Windermere, which I think deserves to be ranked with Potemkin and Sunrise, in Narration in the Fiction Film (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1985), 178-186.

(3) Edward R. Branigan, Point of View in the Cinema: A Theory of Narration and Subjectivity in Classical Film (The Hague: Mouton, 1985), 102-121.

Scribble, scribble, scribble

Detective (Godard, 1985).

Another damned, thick, square book! Always scribble, scribble, scribble, eh, Mr. Gibbon?

William Henry, Duke of Gloucester, 1781.

David here:

Kristin kept the blogfires burning while I traveled last week and did UW duties this one. I had a great time at the University of Georgia in Athens (but didn’t see Stipe) and at Emory in Atlanta (but didn’t see Scarlett). At both places I met sharp, energetic students and faculty. I have a couple of blog entries backlogged for posting, but now recent items relating to publications get the pole position.

First, a Japanese translation of our Film Art: An Introduction has just appeared. It’s a very handsome version of the seventh edition, rendered by Fujiki Hideaki and Kitamura Hiroshi. We’re grateful to them and to Nagoya University Press for publishing it.

First, a Japanese translation of our Film Art: An Introduction has just appeared. It’s a very handsome version of the seventh edition, rendered by Fujiki Hideaki and Kitamura Hiroshi. We’re grateful to them and to Nagoya University Press for publishing it.

Second, the University of California Press is having a big sale on many outstanding media titles, from Richard Abel’s books on French silent cinema and André Bazin’s classics of film theory to Michele Hilmes’ study of NBC television and Mike Barrier’s new Disney biography, The Animated Man. To get the discount you must sign up for an e-newsletter, but it’s not intrusive.

Among the books of mine on sale, the biggest bargain is the hardcover edition of Figures Traced in Light (2005), originally priced at $65, now going for $7.95 plus postage. (No, apparently I don’t get the full-price royalties.) You can find this item here. There are also paperback copies of Figures (going for $12.95) and of The Way Hollywood Tells It ($15.95). If you’re inclined, hurry: the sale ends on 31 October.

The biggest news, though, is that I just got my author’s copies of Poetics of Cinema, published last week. For a while Amazon was telling some people who pre-ordered it that copies won’t be available until 27 December, but now, despite what it says here, the book seems ready to ship.

The biggest news, though, is that I just got my author’s copies of Poetics of Cinema, published last week. For a while Amazon was telling some people who pre-ordered it that copies won’t be available until 27 December, but now, despite what it says here, the book seems ready to ship.

Bad news first. Poetics of Cinema is priced at $45 in paperback, with no sellers I know offering it at discount. Go ahead, say it: Very expensive. If you haven’t published a book, you may not know that authors have no say in the pricing of their work. Publishers would never set a price or price ceiling in a contract, and calculations about pricing are based on many factors, including what comparable books sell for. A high cost isn’t my preference, of course; every writer wants to reach as many readers as possible. But unless you blog or self-publish your work, the publisher sets the price.

There are some good reasons for the cost. Running to 500 fairly dense pages and containing over 500 photographs, Poetics of Cinema was a complicated book to produce. I peddled it to other publishers, but they ruled it out as too whopping an investment for them. So Routledge has priced it along lines of comparable books, reckoning in the size of the likely audience (I hope, more than 118.3 readers). I have to thank Bill Germano, then Publishing Director at Routledge, for taking a chance on this project.

From age fifteen or so I’ve been a compulsive writer. Scribble, scribble, scribble. I’ve been at work on one book or another for over thirty years. I’ve got several projects in mind for my next effort, but I’ve held back committing. Is there any point in publishing more books, at least as books?

I mean this as a serious question. Would it have made any difference to me or my readers if Poetics of Cinema appeared as pdfs, available at a price considerably less than $45? Wouldn’t I find more readers? What about variable pricing? If Radiohead can do it, why can’t I? Somebody in film studies should try putting a digital book for sale online; maybe I will. But for a few years at least, this last baggy monster will be available only in dead-tree format.

Poetics: Some puzzles

Gentlemen Marry Brunettes (Richard Sale, 1955).

If you’ve read this far, you may be interested in what the book is about. Most basically, it’s predicated on the belief that we make progress in research by asking questions. Some questions are too deep to be answered—call them mysteries—but others can be answered with a fair degree of precision and reliability. We can turn mysteries into puzzles and puzzles into plausible answers.

Here’s a fairly common sort of composition in Hollywood cinema of the 1940s. This shot from The Killers (1946) displays the sort of steep depth I’ve talked about at various points on this blog and in my other books.

But now here’s an equally tense confrontation at a counter, from Bad Day at Black Rock (1955), made in early CinemaScope.

It doesn’t look much like the 1940s shot. The characters stand far from us, and the figure in the foreground doesn’t loom over the background. The shot is more open, the composition more porous. And unlike The Killers, Bad Day doesn’t contain close-ups of the actors in any scenes.

So questions come to mind. Did John Sturges have to stage the scene in Bad Day this way? Did other filmmakers resort to the same choice? What factors created pressures toward this more spacious format? Could more resourceful filmmakers have done something different? And given that such shots are rare today, what changes made it possible for filmmakers in later years to create the tight anamorphic widescreen close-ups we have now (as here in Cellular)?

Despite all that has been written about CinemaScope and other early widescreen processes, no one has explored, shot by shot, what staging options were used by filmmakers. A chapter in Poetics of Cinema called “CinemaScope: The Modern Miracle You See Without Glasses” tries to show how filmmakers used the new format to tell their stories. This led them, I propose, to experiment with some staging strategies that, surprisingly, had precedents as far back as the 1910s.

Take another instance. We’re all familiar with recent films that present alternative futures, like Run Lola Run. A story line runs along and then is interrupted, and we switch to the same characters living a different storyline in a parallel universe. The emergence of such “forking path” movies arouses my curiosity. How do they work? How do they make their alternative-reality stories intelligible to the audience? How is it that we’re able to understand them? (After all, the notion of an infinite number of alternative universes to ours is pretty hard to get your head around.) Are such stories a brand-new innovation, or do they have precedents? (Clue: Remember A Christmas Carol?) Why do we see a cluster of these emerging in recent filmmaking?

I tackle these questions in another essay, called “Film Futures.” There I look at several such movies and try to spell out the tacit rules that filmmakers follow and that audiences pick up on. While this story format probably doesn’t constitute a genre, it does obey certain conventions, and I try to chart those. Some films also make some clever innovations in the format, which I also try to trace. The essay as well suggests how the conventions are handled differently in mass-market films like Sliding Doors and in art films like Kieślowski’s Blind Chance.

These two essays, along with the others in the book, try to explain and illustrate an approach to film studies I call film poetics. At bottom, this is an effort to explain why films are designed the way they are: how filmmakers have made certain choices in order to shape our response to their films. How do movies work? How do movies work on us?

Poetics: The project

Vagabond (Varda, 1985).

As a kind of reverse engineering, film poetics looks at both structure and texture. I argue that we ought to study how films are constructed architecturally, as revealed for instance in plot structure or narration. Poetics also concentrates on stylistic patterning, the way filmmakers organize the techniques available to the medium. Poetics traditionally deals as well with thematics, the subjects and ideas that are mobilized by filmmakers and reworked by large-scale form and cinematic style.

Put it this way: I want to know how filmmakers have confronted problems set by others, or created problems for themselves to solve. I want to know how they draw on the past to borrow or modify or reject creative strategies. I want to know filmmakers’ secrets, including the ones they don’t know they know. And I want to know how all this creative activity is shaped to the uptake of spectators in different times and places.

Some of what I’ve written on this blog could illustrate how the poetics-driven perspective works in particular cases. The book offers more such instances, probed in more detail than is possible here. Using a comparative method, I also trace out some general principles of film form and style as they have developed over history.

The book consists of fifteen essays. Some have been published before; those have been revised for this collection. Other essays are newly written. After a somewhat polemical introduction, the first part concentrates on some theoretical problems. The anchoring essay offers a general introduction to the idea of a film poetics, with several examples. (An earlier version is on pdfs here.) In the same essay, I float a model of how film viewers respond to various aspects of films. I distinguish activities of perception, comprehension, and appropriation, and I suggest that a cognitive perspective sheds light on them.

Part I also contains an essay considering how cinematic conventions work. A poetics-based approach will spend a lot of time on norms, traditions, and received routines, for these are often the basis of filmmakers’ creative choices. This essay argues that some conventions are local and require a lot of cultural knowledge, while others are cross-cultural, compelling us to study why certain cinematic strategies seem to crop up across the world.

The second part of Poetics of Cinema considers narrative, one of the most common ways in which films are organized to affect viewers. I wrote a new essay to launch this section, a wide-ranging study called “Three Dimensions of Film Narrative.” The three dimensions I consider are narration, plot structure, and the narrative world. The essay considers how each of these shapes our understanding of a film’s story. This essay ends with a discussion called “Narrators, Implied Authors, and Other Superfluities.”

Some more tightly-focused pieces follow. One is devoted to forking-path plots. Another concentrates on an odd question: What role does forgetting play in our watching a film? Cognitive theory can offer some answers, and I take Mildred Pierce as an example. There’s an update of an essay that has been something of a golden oldie in film courses, “The Art Cinema as a Mode of Film Practice.” In a supplement to that piece I suggest some new avenues of inquiry and draw on more examples, notably Varda’s Vagabond (Sans toit ni loi).

The longest piece in Part II is devoted to what I call network narratives. Prototypes of this would be Grand Hotel, Short Cuts, Crash, and Babel. This essay tries to show how a poetics of cinema shed light on this format, currently a very popular one. When I started looking at these movies, I was surprised to discover how many filmmaking traditions work in this vein; I append a filmography with nearly 250 items, and today I could update it with several more. (1) I consider how this option has developed distinctive strategies of narration, plotting, and worldmaking. I also survey some common themes running across network tales, such as the role of chance and fate. The essay finishes with more in-depth analyses of four films: Altman’s Nashville, Iosseliani’s Favoris de la lune, Anderson’s Magnolia, and Jean-Claude Guiget’s Les Passagers.

Poetics: More problems

Bus Stop (Logan, 1955).

Part III moves from questions of narrative to questions of film style, no stranger to this blog. The opening essay is a tribute to Andrew Sarris that appraises his role in making readers of my generation style-conscious. It’s the most personal piece in the book. There follows a study of Robert Reinert, a director in the German silent cinema who might have become much better known if his quite demented Nerven and Opium had been as widely seen as Caligari. The essay “Who Blinked First?” considers how our reaction to films is affected by the ways in which actors use their eyes, including how and when they blink. Big deal, huh? Actually, yes.

The monster essay in this section is the CinemaScope piece, of which I’ve given versions in lecture form over the last couple of years. I argue that some directors responded to the new widescreen technology by adapting certain norms of staging and shooting to the new format, while other filmmakers moved in more adventurous directions. The piece uses the model of problem/solution as a way to understand stylistic continuity and change, a framework I’ve floated in On the History of Film Style as well.

The last four studies in Part III are devoted to style in Asian cinema. There are two essays on Japanese film of the 1920s and 1930s, both expanded somewhat from their original versions. There I argue that we can see Japanese directors as building upon, as well as adventurously departing from, stylistic norms shared by most filmmaking countries of the period. This brace of essays fills out some ideas that I fielded in Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema, and they should appeal to that growing body of viewers who have developed a passion for Naruse Mikio and Uchida Tomio. It’s gratifying that several of the films I discuss, which I had to study in archives, are now circulating in touring programs.

Poetics of Cinema concludes with two studies of Hong Kong film, one surveying the stylistic tactics by which that very lively tradition excites its audience, the other analyzing the unique innovations of King Hu. The articles are companion pieces to Planet Hong Kong.

Poetics: The mysteries

A Touch of Zen (King Hu, 1970).

As an approach to answering questions about cinema, poetics blends history, criticism, and theory. It requires that we do research into the artistic history of film, looking at styles, genres, narrative modes, and other traditions. It asks for close analysis and interpretation of films. At the same time, it asks broader questions about what principles govern narrative, stylistic patterning, and the like. I’d say it obliges a historian to concentrate on aesthetics; it makes criticism more historical and theoretical; it ties theory to concrete historical conditions and the fine-grain workings of individual films.

Kenneth Burke used to say that you could get a sense of a book by looking at its first and last sentences. My book’s first essay opens this way:

Sometimes our routines seem transparent, and we forget that they have a history.

I think that this captures my concern to look closely at familiar things in film and try to make their principles a little more evident. Yet in trying to make filmmakers’ choices explicit and tracing out the principles undergirding how we make sense of movies, I’m sometimes criticized for simply stating common sense. Poetics can look bland alongside the skywriting swoops of most academic film theory. But skywriting is blurry and dissolves while you look at it. By contrast, clearly setting out some basics of filmic construction and comprehension offers a firmer place to start answering questions about how movies work and work on us.

Poetics tries to produce concrete, approximately true claims about cinema. Most film theory operates as an application, borrowing big theories of culture, identity, nationhood, and the like and then mapping them onto films. The results are usually thin. It seems to me that most film theory today is not carefully thought through or persuasively argued. For examples, see my essay in Post-Theory, the last chapter of Figures, and my comments here and here on this site.

In trying to establish reliable knowledge about cinema, we won’t answer every question and we will make false steps, but we can make progress. Film poetics is one way we film enthusiasts can join that tradition of rational and empirical inquiry which remains our most dependable path to knowledge. My introduction, though peppered with some pokes at Big Theory, has the serious purpose of making a plea for film scholars to join that tradition.

The final line of the book concludes the essay on King Hu:

The mainstream [Hong Kong] style has given us many beautiful and stirring films, but Hu’s eccentric explorations evoke something that other directors’ works seldom arouse: a sense that extraordinary physical achievement, if caught through precisely adjusted imperfections, becomes marvelous.

To get the full point you need to read the essay, but what should come through here is my concern to highlight filmmakers’ originality when I find it, and to locate it by means of a comparative method. In addition, I hope that what comes through is an appreciation of the sheer exhilaration we feel when a filmmaker has made the right, bold choice. A poetics-based approach probably can’t fully explain this feeling—it may fall under the heading of mysteries rather than puzzles—but at least it can reveal how some forces contribute to it.

My summary, and the size of the book, may leave the impression that I think that I’ve answered these questions fully. Of course I don’t. I try only to make some progress, realizing that offering answers is also an invitation to disagree, to refine the questions and tackle new ones. Nor do I think that these are the only questions that matter. We’re just starting to understand how films work and work on us, and there are a great many areas we haven’t charted. (Performance, to take a big one.) We have to start somewhere, though. I’d hope that by posing some questions and proposing some answers, Poetics of Cinema offers fruitful points of departure.

(1) Some candidates are 25 Fireman Street (1973, Hungary, István Szabó), Feast of Love (2007, US, Robert Benton), Continental—A Film without Guns (2007, Canada/ Stephane Lafleur), The Edge of Heaven (2007, Germany/ Turkey, Fatih Akin), Unfinished Stories (2007, Iran, Pourya Azarbayjani), God Man Dog (2007, Taiwan, Singing Chen [Chen Hsin-hsuan]), A Century’s End (2000, Korea, Song Neung-han), and Why Did I Get Married? (2007, US Tyler Perry).

A Moment of Innocence (Mohsen Makhmalbaf, 1996).