Archive for the 'Film technique: Cinematography' Category

Do filmmakers deserve the last word?

DB here:

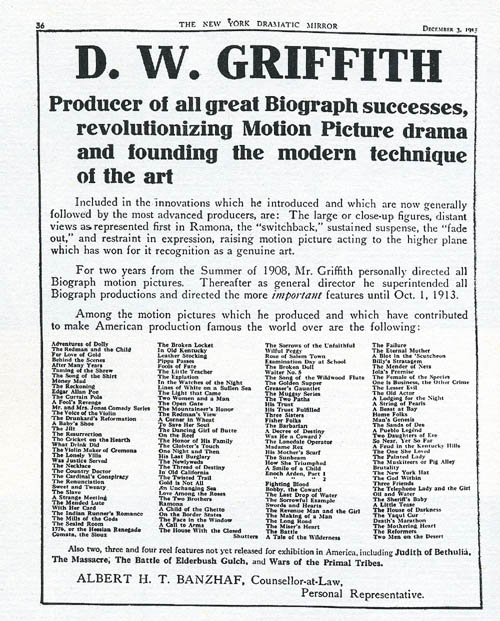

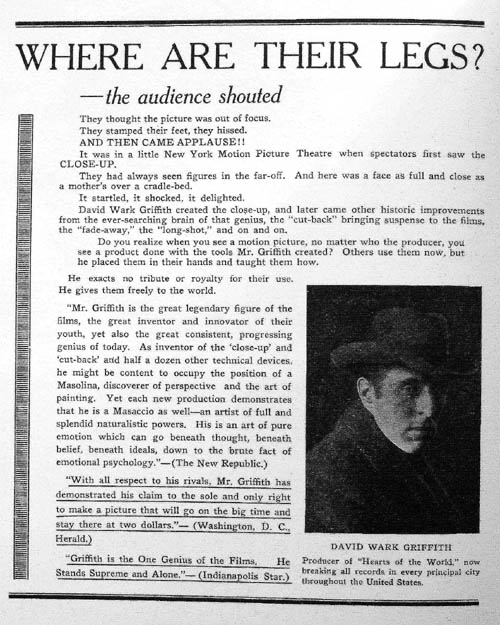

On 3 December 1913, the above advertisement appeared in the New York Dramatic Mirror. D. W. Griffith had left the American Biograph company and set out on an independent path that would lead to The Birth of a Nation and beyond. Because Biograph never credited directors, casts, or crews, he wanted to make sure that the professional community was aware of his contributions. Not only did he point out that he had made several of the most noteworthy Biograph films; he also took credit for new techniques. He introduced, he claims, the close-up, sustained suspense, restrained acting, “distant views” (presumably picturesque long-shots of the action), and the “switchback,” his term for crosscutting—that editing tactic that alternates shots of different actions occurring at the same time.

Griffith’s bid for credit was a shrewd move for his career, and it had repercussions after the stunning success of The Birth of a Nation two years later. Many historians took Griffith at his word and credited him with the breakthroughs he listed. He became known as the father of “film grammar” or “film language.” The idea hung on for decades. Here’s the normally perceptive Dwight Macdonald, criticizing Dreyer’s Gertrud for being anachronistic:

He just sets up his camera and photographs people talking to each other, usually sitting down, just the way it used to be done before Griffith made a few technical innovations. (1)

Filmmakers believed the Griffith story too. Orson Welles wrote of the “founding father” in 1960:

Every filmmaker who has followed him has done just that: followed him. He made the first close-up and moved the first camera. (2)

In the late 1970s a new generation of early-cinema scholars gave us a more nuanced account of Griffith’s place in history. They pointed out that most of the innovations he claimed either predated his Biograph work, (3) or appeared simultaneously and independently in Europe and in other American films. Some Griffith partisans had already conceded this, but they maintained that he was the great synthesizer of these devices, and that he used them with a vigor and vividness that surpassed the sources.

That judgment seems right in part, but Eileen Bowser, Tom Gunning, Barry Salt, Kristin Thompson, Joyce Jesniowski, and other early-cinema researchers have drawn a more complicated picture. (4) Griffith did speed up cutting and devote an unusual number of shots to characters entering and leaving locales. But these innovations weren’t usually recognized as original by previous historians. More interestingly, much of what Griffith did was not taken up by his successors. His technique was idiosyncratic in many respects. By 1915 younger directors like Walsh, Dwan, and DeMille were forging a smoother style that would be more characteristic of mainstream storytelling cinema than Griffith’s somewhat eccentric scene breakdowns. Instead of creating film language, he spoke a forceful but often unique dialect.

The New York Dramatic Mirror ad coaxes me to reflect on how filmmakers have shaped critics’ and historians’ responses to their work. Hawks and Hitchcock developed a repertory of ideas, opinions, and anecdotes to be trotted out on any occasion. Today, directors write books, give interviews, appear on infotainment shows, and provide DVD commentary. We know that many of the talking points are planned as part of the film’s publicity campaign, and journalists dutifully follow the lead. (In Chapter 4 of The Frodo Franchise, Kristin discusses how this happened with Lord of the Rings.) For many decades, in short, filmmakers have been steering critics and viewers toward certain ways of understanding their films. How much should we be bound by the way the filmmaker positions the film?

Deep focus and deep analysis

Citizen Kane (1941).

Determining intentions is tricky, of course. Still, I think that in many cases we can reconstruct a plausible sense of an artist’s purposes on the basis of the artwork, the historical context, surviving evidence, and other information. (5) This may or may not correspond to what the artist says on a particular occasion. For now, I want simply to point to one instance in which filmmakers have shaped critical uptake, with results that are both illuminating and limiting.

In the late 1940s and early 1950s, André Bazin, one of the great theorists and critics of cinema, argued that Orson Welles and William Wyler created a sort of revolution in filmmaking. They staged a shot’s action in several planes, some quite close to the camera, and maintained more or less sharp focus in all of them. Bazin claimed that Welles’ Citizen Kane and The Magnificent Ambersons and Wyler’s The Little Foxes and The Best Years of Our Lives constituted “a dialectical step forward in film language.”

Their “deep-focus” style, he claimed, produced a more profound realism than had been seen before because they respected the integrity of physical space and time. According to Bazin, traditional cutting breaks the world into bits, a series of close-ups and long shots. But Welles and Wyler give us the world as a seamless whole. The scene unfolds in all its actual duration and depth. Moreover, their style captured the way we see the world; given deep compositions, we must choose what to look at, foreground or background, just as we must choose in reality. Bazin wrote of Wyler:

Thanks to depth of field, at times augmented by action taking place simultaneously on several plane, the viewer is at least given the opportunity in the end to edit the scene himself, to select the aspects of it to which he will attend. (6)

While granting differences between the directors, Bazin said much the same about Welles, whose depth of field “forces the spectator to participate in the meaning of the film by distinguishing the implicit relations” and creates “a psychological realism which brings the spectator back to the real conditions of perception” (7).

In addition, Bazin pointed out, this sort of composition was artistically efficient. The deep shot could supply both a close-up and a long-shot in the same framing—a synthesis of what traditional editing had given in separate shots. Bazin wove all these ideas into a larger theory that cinema was inherently a realistic medium, bound to photographic recording, and Welles and Wyler had discovered one path to artistic expression without violating the medium’s biases.

There are many objections to Bazin’s argument, some of which I’ve rehearsed in On the History of Film Style. My point here is that Bazin was presenting analytical points that stemmed from publicity put out by Welles, Wyler, and especially their talented cinematographer Gregg Toland.

In a 1941 article in American Cinematographer, Toland talked freely about how he sought “realism” in Citizen Kane. The audience must feel it is “looking at reality, rather than merely a movie.” Key to this was avoiding cuts by means of long takes and great depth of field, combining “what would conventionally be made as two separate shots—a close-up and an insert—into a single, non-dollying shot.”(8) Toland defended his sometimes extreme stylistic experimentation on grounds of realism and production efficiency, criteria that carried some weight in his professional community of cinematographers and technicians. (9)

Toland’s campaign for his style addressed the general public too. For Popular Photography he wrote an article (10) explaining again that his “pan-focus” technique captured the conditions of real-life vision, in which everything appears in sharp focus. A still broader audience encountered a Life feature in the same year (11), explaining Toland’s approach with specially-made illustrations. Two samples show selective focus, one focused on the background, the other on the foreground.

An accompanying photo shows pan-focus at work, with Toland in frame center, an actor in the background, and Toland’s camera assistant in the foreground.

In sum, Toland’s publicity prepared viewers, both professional and nonprofessional, for an odd-looking movie.

Throughout the 1940s, Welles and Wyler wrote and gave more interviews, often insisting that their films invited greater participation on the part of spectators. In a crucial 1947 statement, Wyler noted:

Gregg Toland’s remarkable facility for handling background and foreground action has enabled me over a period of six pictures he has photographed to develop a better technique for staging my scenes. For example, I can have action and reaction in the same shot, without having to cut back and forth from individual cuts of the characters. This makes for smooth continuity, an almost effortless flow of the scene, for much more interesting composition in each shot, and lets the spectator look from one to the other character at his own will, do his own cutting. (12)

Some of this publicity material made its way into French translation after the liberation of Paris, just as Kane, The Little Foxes, and other films were arriving too. Bazin and his contemporaries picked up the claims that these films broke the rules. Deep-focus cinematography became, in the hands of critics, a revolutionary new technique. They presented it as their discovery, not something laid out in the films’ publicity.

But the case involved, as Huck Finn might say, some stretchers. Watching the baroque and expressionist Kane, it’s hard to square it with normal notions of realism, and we may suspect Toland of special pleading. Some of Toland’s purported innovations, such as low-angle shots showing ceilings, had been seen before. Even the signature Toland look, with cramped, deep compositions shot from below, can be found across the history of cinema before Kane. Here is a shot from the 1939 Russian film, The Great Citizen, Part 2 by Friedrich Ermler.

More seriously, some of Toland’s accounts of Kane swerve close to deception. For decades people presupposed that dazzling shots like these were made with wide-angle lenses.

Yet the deep focus in the first image was accomplished by means of a back-projected film showing the boy Kane in the window, while the second image is a multiple exposure. The glass and medicine bottle were shot separately against a black background, then the film was wound back and the action in the middle ground and background were shot. (And even the middle-ground material, Susan in bed, is notably out of focus.) I suspect that the flashy deep-focus illustration in Life, shot with a still camera, is a multiple exposure too. In any event, much of the depth of field on display in Kane couldn’t have been achieved by straight photography. (13)

RKO’s special-effects department had years of experience with back projection and optical printing, notably in the handling of the leopard in Bringing Up Baby, so many of Kane‘s boldest depth shots were assigned to them. But here is all that Toland has to say on the subject:

RKO special-effects expert Vernon Walker, ASC, and his staff handled their part of the production—a by no means inconsiderable assignment—with ability and fine understanding. (14)

Kane’s reliance on rephotography deals a blow to Bazin’s commitment to film as a medium committed to recording an event in front the camera. Instead, the film becomes an ancestor of the sort of extreme artificiality we now associate with computer-generated imagery.

Despite these difficulties, Toland’s ideas sensitized filmmakers and critics to deep space as an expressive cinematic device. Modified forms of the deep-focus style became a major creative tradition in black-and-white cinema, lasting well into the 1960s. Bazin’s analysis certainly developed Toland’s ideas in original directions, and he creatively assimilated what Toland and his directors said into an illuminating general account of the history of film style. None of these creators and critics were probably aware of the remarkable depth apparent in pre-1920 cinema, or in Japanese and Soviet film of the 1930s. Their claims taught us to notice depth, even though we could then go on to discover examples that undercut Toland’s claims to originality.

Some little things to grasp at

I assume that Toland and his directors were sincerely trying to experiment, however much they may have packaged their efforts to appeal to viewers’ and critics’ tastes. But sometimes artists aren’t so sincere. By the 1950s, we have directors who started out as film critics, and they realized that they could guide the agenda. Here is Claude Chabrol:

I need a degree of critical support for my films to succeed: without that they can fall flat on their faces. So, what do you have to do? You have to help the critics over their notices, right? So, I give them a hand. “Try with Eliot and see if you find me there.” Or “How do you fancy Racine?” I give them some little things to grasp at. In Le Boucher I stuck Balzac there in the middle, and they threw themselves on it like poverty upon the world. It’s not good to leave them staring at a blank sheet of paper, no knowing how to begin. . . . “This film is definitely Balzacian,” and there you are; after that they can go on to say whatever they want. (15)

Chabrol is unusually cynical, but surely some filmmakers are strategic in this way. I’d guess that a good number of independent directors pick up on currents in the culture and more or less self-consciously link those to their film.

Today, in press junkets directors can feed the same talking points to reporters over and over again. An example I discuss in the forthcoming Poetics of Cinema is the way that Chaos theory has been invoked to give weight to films centering on networks and fortuitous connections. As I read interview after interview, I thought I’d scream if I encountered one more reference to a butterfly flapping its wings.

More recently, Paul Greengrass gave critics some help when he suggested that the jumpy cutting and spasmodic handheld camera of The Bourne Ultimatum suggested the protagonist’s subjective point of view–presumably, Jason’s psychological disorientation and frantic scanning of his surroundings. I expressed skepticism about this on an earlier blog entry, Anne Thompson replied on her blog, and I returned to the subject again. Any director’s statement of purpose is interesting in itself, but it should be assessed in relation to the evidence we detect onscreen.

Another recent instance: the new Taschen book on Michael Mann. The luscious pictures, mainly from Mann’s archive, are the volume’s raison d’etre, but the filmmaker seems to have placed unusual demands on the text. F. X. Feeney writes:

An earlier version of this book completed by another writer attempted (in a spirit of sincere praise) to treat Mann’s films as reactions against film traditions, as subversions of genre. This fetched a rebuke from Mann: “It’s irrelevant and neither accurate nor authentic to compare my films to other films because they don’t proceed from genre conventions and then deviate from those conventions. They proceed from life. For better or worse, what I’ve seen and heard and learned on my own is the origin of this material. Maybe the film medium by nature spawns conventions, because we all built on what’s gone before, but the content and themes of my films are not facile and derivative. They are drawn from life experience.” (16)

We have to wonder if Mann’s objection played a role in eliminating the earlier writer’s version. If that happened, it’s an unusually strong instance of a director’s holding sway over critical commentary. (17)

In the text we have, Feeney provides a chronological account of Mann’s career: plot synopses, thematic commentary, production background. There’s no discussion of broader historical trends, such as the migration of TV directors into film, the creative options available in 1980s-1990s Hollywood, the development of self-conscious pictorialism in modern film, the possibility of genre films becoming art-films or prestige pictures, or the changes in media culture or American society. All of these lines of inquiry would require comparing Mann with other filmmakers. It remains for other writers, perhaps without the director’s cooperation, to put Mann’s achievement into such contexts.

It’s always vital to listen to filmmakers, but we shouldn’t limit our analysis to what they highlight. We can detect things that they didn’t deliberately put into their films, and we can sometimes find traces of things they don’t know they know. For example, virtually no director has explained in detail his or her preferred mechanics for staging a scene, indicating choices about blocking, entrances and exits, actors’ business, and the like. Such craft skills are presumably so intuitive that they aren’t easy to spell out. Often we must reconstruct the director’s intuitive purposes from the regularities of what we find onscreen. (For examples, see this site here, here, and here.) And it doesn’t hurt, especially in this age of hype, to be a little skeptical and pursue what we think is interesting, whether or not a director has flagged it as worth noticing.

(1) Macdonald, “Gertrud,” Esquire (December 1965), 86.

(2) Quoted in Orson Welles and Peter Bogdanovich, ed. Jonathan Rosenbaum, This is Orson Welles (New York: HarperCollins, 1992), 21).

(3) Such would seem to be the case of the close-up, which of course is found very early in film history. But Griffith’s idea of a close-up may not correspond to ours. More on this in a later blog, perhaps.

(4) I give an overview of this rich body of research in Chapter 5 of On the History of Film Style. See also various entries in the Encyclopedia of Early Cinema, ed. Richard Abel (New York: Routledge, 2005).

(5) The most detailed argument for this view I know is Paisley Livingston’s book Art and Intention: A Philosophical Study.

(6) “William Wyler, or the Jansenist of Directing,” in Bazin at Work: Major Essays and Reviews from the Forties and Fifties, ed. Bert Cardullo (New York: Routledge, 1997), 8.

(7) Orson Welles: A Critical View, trans. Jonathan Rosenbaum (New York: Harper and Row, 1978) 80).

(8) Toland, “Realism for Citizen Kane,” American Cinematographer 22, 2 (February 1941), 54, 80.

(9) See the discussion in Bordwell, Janet Staiger, and Kristin Thompson, The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1985), 345-349.

(10) Toland, “How I Broke the Rules in Citizen Kane,” Popular Photography (June 1941), 55, 90-91.

(11) “Orson Welles: Once a Child Prodigy, He Has Never Quite Grown Up,” Life (May 26, 1941), 110-111.

(12) Wyler, “No Magic Wand,” The Screen Writer (February 1947), 10.

(13) Peter Bogdanovich was to my knowledge the first person to publish some of this information; see “The Kane Mutiny,” Esquire 77, 4 (October 1972), 99-105, 180-90.

(14) Toland, “Realism,” 80.

(15) “Chabrol Talks to Rui Noguera and Nicoletta Zalaffi,” Sight and Sound 40, 1 (Winter 1970-1971), 6.

(16) F. X. Feeney, Michael Mann (Cologne: Taschen, 2006), 21.

(17) Mann’s reasoning puzzles me. He insists that his films can’t be compared to others along any dimensions, especially thematic ones. Yet in saying that his films are lifelike, he suggests that other films aren’t as realistic as his. Moreover, what about comparisons on grounds of technique, surely one of the most striking and admired features of Mann’s work? For reasons that are obscure, the director discourages any critical consideration of style; Feeney tells us that Mann hates the very word (p. 20).

Ad in Wid’s Year Book 1918.

PS: 15 October: I’ve received a clarification from Paul Duncan, editor of F. X. Feeney’s Michael Mann book for Taschen. He expresses general agreement with my suggestions about how directors shape the uptake of their work, but he explains that the Mann book isn’t an instance of it. Here are the comments bearing on my blog entry.

In reply to my suggestion of other avenues to explore about Mann’s career:

In fairness to F.X. Feeney, he only had 25,000 words to cover Mann’s career, and all the subjects you write about are really outside the scope of the book. It sounds as though these are subjects that you would like to explore, and I can’t wait to read them in a future book or blog.

As for whether Mann exercised some control over the book’s final form, which I float as one possible explanation for its compass:

First, you speculate whether Mann caused the first version of the book to be scrapped, i.e. He exerted editorial control/censorship over the book. This is not the case, and if it was, do you think that he would have allowed F.X. to write that in the published version of the book?

In Note 17 appended to Feeney’s quote, you write: “Yet in saying that his films are lifelike, he suggests that other films aren’t as realistic as his.” If you had continued Mann’s quote, you would have reported the following: “I don’t look at the excellent French director Jean-Pierre Melville to decide how to tell the story in Thief. I meet thieves. And I guarantee you the reason Melville’s Le Samourai 1967) has authenticity, the reason Raoul Walsh’s White Heat (1949) has authenticity, is because those film-makers knew thieves, too.” I do not see any evidence here that Mann suggests that his films are more lifelike than other directors’. Only that his films stem from life like other films stem from life.

Also, in Note 17, you write: “For reasons that are obscure, the director discourages any critical consideration of style; Feeney tells us that Mann hates the very word (p. 20).” The reason Mann hates the word “style”—and I apologize for not making this clear in the book—is because after producing the Miami Vice TV show, he was forever referred to as a stylist, and the “style” of the show was all anybody ever talked about. The implication was that Mann is a director of style without substance. Subsequently, Mann has been very wary of the word, and discussion of it, because it puts undue weight on one aspect of his work.

Finally, I would like to explain a little of the working method with Mann on the book. The book was researched and written during rehearsal, filming and editing of Collateral. F.X. wrote the text and was given full access to everything that Mann had said in interviews. Mann then read and annotated the text, and this was discussed face-to-face with F.X. Most of these annotations were of a factual nature, correcting dates, being precise about the sequence of events, and to correct misinterpretations of his comments in previous interviews. However, they would also bring up new comments from Mann about his work. F.X. then rewrote some texts to include Mann’s comments, and then F.X. wrote his replies. In this way, the book became more of a dialogue between Mann and F.X. and is stronger for it I feel. So, in this case, the filmmaker did not get the last word.

I thank Paul for his clarifications, which should be of interest to all the book’s readers. On only two matters do we disagree.

First, Feeney’s book achieves what it set out to achieve, and it deserves credit for giving us valuable information about Mann in a clear, pungent style. And no one expects a Taschen book to be an in-depth monograph covering all aspects of a director’s career. But I still think that length limits don’t prevent an author from raising the contextual issues I mention. Many articles manage to address matters that go beyond the sort of career survey that Feeney provides, so there are ways to sketch such issues in an abbreviated way. I inferred, erroneously, that the choice not to tackle them could have been related to Mann’s own views on the comparative dimension that such issues tend to rely on.

Secondly, a minor matter: The fact that Mann can invoke Melville and Walsh on films about thieves suggests that a comparative perspective is valuable; he’s including himself in the company of directors who know their subjects from life, in explicit contrast to those who don’t. I didn’t include the extra sentences because I thought that they simply provided further signs of the contradiction I found in Mann’s own position—that his films can’t be compared to other directors’ works.

Vancouver visions

Drizzle every day can’t dampen audiences’ enthusiasm.

DB again:

More dispatches from the Vancouver International Film Festival.

“Be pleased, then, you living one, in your delightfully warmed bed, before Lethe’s ice-cold wave will lick your escaping foot.” As a tram destination, Lethe makes a brief appearance in the Swedish film You, the Living, Roy Andersson’s latest comedy of trivial miseries. The line from Goethe is apt. After ninety minutes of drab apartments and Balthus-like figures, all bathed in sickly greenish light, you’re ready to stay in bed forever.

As in Songs from the Second Floor, Andersson gives us a loose network narrative, with barely characterized figures threading their way through urban locales. Long-shot, single-take scenes turn clinics and dining rooms into monumentally desolate spaces. Humans, either bulbous or emaciated, trudge through torrential rain and peer out from distant windows. The bodies may be distorted and careworn, but the spaces are even more so. We get a sort of dystopian Tati, in which gags, near-gags, and anti-gags are swallowed up in the cavities we call home and workplace. A carpet store stretches off into the distance, and a cloakroom seems like a basketball court.

In You, the Living, Andersson’s characters recount their dreams, and these open onto areas only a step beyond our world in their lumpish crowds and eerie vacancy. Judges at a trial are served beer as they condemn the accused. Spectators at an electrocution snack on popcorn from supersized buckets. How can I not like a filmmaker so committed to moving his actors around diagonal spaces, even if the frame is either sparse or uniformly packed, and though he does treat his people like sacks of coal? Don’t look for hope here, only a sardonic eye attracted by banality and pointlessness, images made all the bleaker by an occasional song.

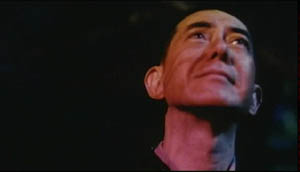

I’m drawn to directors who create a powerful visual and auditory world more or less out of phase with reality as we usually see it (in life and in movies). Andersson is one such director; Jiang Wen is another, whose audacious The Sun Also Rises is one of my favorites of the festival so far. Not doing so well with Mainland Chinese audiences, according to the International Herald Tribune, it hasn’t warmed up a lot of Western critics either. Amazingly, it was declined for competition at Cannes.

It seems impossible to discuss The Sun Also Rises without using the word “magic,” as in magic realism, but I saw it as more of a fairy tale or fable. Set in the Cultural Revolution, it tells two stories in the first two sections. A young boy’s mother goes a little mad on a labor farm; in another village, a teacher is compromised by the passionate love of a nurse and an accusation of sexual misconduct. The two stories intersect in a third section, which leads to a jubilant, if disconcerting, final stretch.

At the center of each plot stands a vivacious, passionate woman who unleashes a cascade of unhappy events. Yet the tone of the film is cheerful, almost giddy, thanks not only to Joe Hisaishi’s buoyant score (he may now be the Nino Rota of Asian cinema) but to Jiang’s fresh, assured technique. The movie starts with tight close-ups—the fish-design shoes the mother wants, her feet and hands, her son’s hands at the abacus—edited at a cracking pace. Staccato movements in and out of the frame give the whole passage a visual snap that launches the movie. Characters lunge through the shots, running this way and that without catching breath, and Jiang’s camera follows them without pausing for the sort of stately scene-setting that audiences may expect. Likewise, the second story opens with hands at play and work, the teacher stroking his guitar strings and a bevy of woman kneading bread dough.

At the center of each plot stands a vivacious, passionate woman who unleashes a cascade of unhappy events. Yet the tone of the film is cheerful, almost giddy, thanks not only to Joe Hisaishi’s buoyant score (he may now be the Nino Rota of Asian cinema) but to Jiang’s fresh, assured technique. The movie starts with tight close-ups—the fish-design shoes the mother wants, her feet and hands, her son’s hands at the abacus—edited at a cracking pace. Staccato movements in and out of the frame give the whole passage a visual snap that launches the movie. Characters lunge through the shots, running this way and that without catching breath, and Jiang’s camera follows them without pausing for the sort of stately scene-setting that audiences may expect. Likewise, the second story opens with hands at play and work, the teacher stroking his guitar strings and a bevy of woman kneading bread dough.

The exuberance of the characters and the style contrasts with the usual presentation of this cruel era of PRC history. Jiang finds real pleasure in Cultural Revolution kitsch, and he links a snapshot of the missing father to an iconic image from The Red Detachment of Women. It’s another knot joining the two plot strands; in the second section, villagers watch a screening of that film. Jiang makes the event a real festivity, with couples courting, the teacher humming along with the tunes, and an old lady feeding fish in a pond. Jiang dares to suggest that the force-fed popular culture of Maoism, so scoffed at now, gave genuine enjoyment

The fairy-tale atmosphere is conjured up by little mysteries, such as a talking bird and the possibility of taking dictation on an abacus, and bigger ones about fatherhood, a stone hut in the forest, and a shadowy figure named Alyosha, whose identity is more or less revealed in the film’s final long sequence. Variety‘s Derek Elley found The Sun Also Rises both rushed and dawdling, but you could say that about 8 ½ too. Like Fellini’s film, Jiang’s shows a filmmaker at the top of his powers inviting us to savor the exhilarating attractions of imagination.

Another world, another vision. The camera frames a rope descending into black water and tilts slowly, really slowly, up to reveal the ship’s prow and the deck, swathed in darkness. Two silhouettes are visible, and one says, “Don’t follow me too soon.” Soon we’re following the transfer of a small suitcase, the disembarking of passengers making their way to a train. This nearly thirteen-minute shot (!) gives way to another long take, in which we see, in the distance, a murder on the quay.

Béla Tarr has called The Man from London a film noir, and he explained that to me by saying, “Not an American film noir. They were done by bad directors. More like the original French film noirs.” Indeed, the opening shot, with its mists and murky waterfront, suggests Quai des brumes. But here the plot action is slight, presented at a distance, and opaque in its motives; 10 % story, we might say, but 90 % atmosphere. The camera coasts across the waterfront town with the same grave deliberation we see in Damnation, Sátántangó, and Werckmeister Harmonies, swallowing up the Simenon situation in Tarr’s fluid way of seeing, a scanning of ever-shifting surfaces and vistas.

With fewer than thirty shots across about 133 minutes, The Man from London is another exercise in long-take virtuosity, but I thought I noticed some fresh departures. For one thing, there are few characters and relatively few locales, and situations are brought out with unusual explicitness (for Tarr). Instead, it seemed to me that Tarr was exploring new possibilities in one of his pet techniques, the over-the-shoulder long shot I mentioned in an earlier entry.

The opening shot, at first an apparently objective survey of the moored ship, turns out to be a view from the tower manned by Maloin. In shooting the wharf, the camera is forever oscillating, within a single shot, between what we can see outside, at a distance, from a high angle, and glimpses of Maloin at his post, his head or shoulder sliding into the foreground. Imagine Rear Window without the reverse shots of Jimmy Stewart watching.

In earlier films, Tarr tended to be quite clear when his foreground character was noticing something in the distance; his chief interest lay in suppressing the character’s reaction. What we get here can be seen as a refinement of the opening shot of Damnation, with its awesome landscape gradually reframed by Karrer looking out his window, or of passages of the doctor at his window in Sótántangó. Several of the tower scenes in The Man from London, are elaborations of that image scheme, but with more ambiguity. The camera, slipping from long-shot background and close-up foreground, coasts along without telling us whether Maloin has seen exactly what we’ve seen. The result is a suspenseful uncertainty not only about what’s happening in the noir plot but also about what Maloin knows.

There are many other points of interest in the new film, and after one viewing I can’t claim to have a grip on them. But I do think critics have overlooked its sheer visual beauty and Tarr’s efforts to turn his style toward a fluid pictorial suspense.

Altogether less flamboyant than any of these was Suo Masayuki’s I Just Didn’t Do It (Japan), which I’d been looking forward to since my February entry. It’s definitely a change of pace for a director known for comedies that satirize youth culture and middle-aged boredom. A young man is accused of groping a schoolgirl on a crowded traincar. The police advise him to confess and pay a fine, but he insists on his innocence. This decision drops him into a judicial mill that grinds slow and altogether too fine.

The script carpentry seems to me excellent. The presentation of each phase of the boy’s case could have been dry, but Suo makes each step hinge on a detail of fact or inference, so small questions keep popping up—including questions about whether the boy really might have done it. The finale, which recalls Kurosawa’s Ikiru in its methodical summing up of everything we have seen, becomes grueling, but in a salutary way. In Japan, the film is a trailblazing critique of the criminal justice system, where most people arrested confess in order to avoid the almost inevitable guilty verdict in a trial. Eliminating a jury, barring defense counsel’s discovery of prosecution evidence, and capriciously replacing one judge by another midway through a case, the system encourages cynical submission.

Suo avoids stylistic pyrotechnics. He plays down his signature mugshot framings (the publicity still above is an exception) and has recourse to handheld camerawork simply to distinguish the train scenes from the rest of the film. Still, his shooting displays a quiet agility. The high point is probably the testimony of the schoolgirl, her identity protected by screens set up around her. Suo finds a remarkable variety of camera setups here, each well-judged to impart a particular piece of information. (In its resourceful changes of viewpoint, the sequence reminded me of Mizoguchi’s courtroom scenes in Taki no Shiraito and Victory of Women.) The title suggests a strident social-problem film, but Suo’s calm plainness of handling yields a quality rare in the genre: tact.

Many more films to report on, including Johnnie To’s latest, but I must rush off to—what else?—another movie. I’ll try for a wrapup on Thursday, while I’m on that highway in the sky.

The critics line up: Bérénice Reynaud, Shelly Kraicer, Chuck Stephens, and Tony Rayns.

The sarcastic laments of Béla Tarr

Werckmeister Harmonies.

DB here:

Last weekend, Facets MultiMedia in Chicago held a tribute to Béla Tarr. Milos Stehlik and his colleagues have been long-time champions of Tarr’s work, holding retrospectives and releasing nearly all his features on DVD (with Sátántangó soon to come). Tarr arrived on Saturday, but an emergency sent him back to Hungary sooner than he expected. So instead of discussing his work with a panel, he could only introduce the screening of Werckmeister Harmonies before running off to the airport.

The panel went ahead, with Jonathan Rosenbaum, Scott Foundas, and me chatting with Susan Doll of Facets. It wasn’t as pungent a session as it would have been with Tarr there, but I thought it was still pretty interesting. Jonathan, Scott, and Susan had thoughtful comments, and the questions from the audience were exceptionally good. The whole session was recorded for an online broadcast at some point, so you might want to watch out for that. And I have earlier blog entries on Sátántangó here and here.

In preparation for the panel I spent last week reconsidering Tarr’s work, so I offer a few notions about his films and how we might place them in the history of cinematic form and style. Some of these remarks build on things I said at the session.

Up close and personal

Some directors accommodate critics, accepting or at least tolerating writers’ efforts to probe the work. Not Tarr. Ask about his plots and characters, and he claims that he doesn’t tell stories. Point out what seem allegorical or symbolic touches, and he protests that he doesn’t make allegories and he hates symbols. Mention contemporary cinema, and the reply is abrupt: “For me, when I see something at the cinema it is always full of shit.” And if you tell him that his early films seem quite different from his more recent ones, he vehemently disagrees.

Some directors accommodate critics, accepting or at least tolerating writers’ efforts to probe the work. Not Tarr. Ask about his plots and characters, and he claims that he doesn’t tell stories. Point out what seem allegorical or symbolic touches, and he protests that he doesn’t make allegories and he hates symbols. Mention contemporary cinema, and the reply is abrupt: “For me, when I see something at the cinema it is always full of shit.” And if you tell him that his early films seem quite different from his more recent ones, he vehemently disagrees.

As Scott pointed out in our panel, though, it can be plausible to apply the concept of “period” to filmmakers’ work as we do to painters’ careers. Lars von Trier has been fairly explicit that after mastering a polished style for his work up through Zentropa/ Europa he wanted to try something new, and with The Kingdom he shifted toward a looser, on-the-fly style that pointed toward Dogme 95. Any viewer can be forgiven for thinking that Tarr has moved in the opposite direction of von Trier, from a pseudo-documentary approach toward something much more grave and majestic.

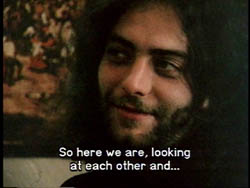

The first three theatrical features focus on the urban working class and their struggles to improve their lot. In Family Nest (1979), a family who can’t afford a flat of their own squeezes in with the husband’s parents. The tight quarters, the ceaseless complaints of the father-in-law, and the husband’s inertia force his wife and child to flee to the streets. The Outsider (1981) follows a young violinist as he drifts among jobs and into a passive marriage before being called up for military service. The family in The Prefab People (1982) has a flat and a decent job, but the wife finds the husband indifferent to her boring routines, and he looks for an escape in a job in another town. The concentration on ordinary people’s lives and the search for drama in the everyday dissatisfactions of city life put the films in the neorealist line of succession.

Stylistically, the films are stripped down in ways that also owe debts to modern traditions. Shot mostly handheld, adjusting the framing to the actors’ performances, they belong to a strain of films from the 1960s on that sought to suggest the immediacy of cinéma-vérité documentary. Unlike many such films, however, Tarr’s buy into a long-take aesthetic. Perhaps surprisingly, these movies’ shots run abnormally long: an average shot length of 32 seconds for Family Nest, 33.5 for The Outsider, 47 seconds for Prefab People. By comparison, Hollywood films of these years were consistently running between 4 and 8 seconds per shot, and comparatively few European and Asian films rely on shots as lengthy as Tarr’s.

Most scenes in these three films are dialogues, and the camera holds intently, if shakily, on faces. This concentration is enhanced by the general absence of establishing shots. A scene opens more or less in the middle of a conversation, and we get a character already challenging another. The visual pattern is that of shot/ reverse-shot, and in most scenes the first face is counterposed to a second one by either a cut or a pan. Shooting on location in cramped rooms, Tarr makes his framings tight; in Family Nest, the jammed frames give us and the characters almost no breathing space.

By relying on more or less isolated faces in close-ups, Tarr can absorb us in the intimate drama while sometimes catching us off guard. For instance, when we get a single character without an establishing shot, there is often a momentary uncertainty about where we are, or when the action is taking place. We also can’t be sure of who’s present besides the speaker, so the close view of him or her leaves us hanging: To whom is s/he talking? We’re pushed to pay close attention to what the character is saying, looking for any clues to the dramatic context. Tarr’s tactic also delays the reaction of the listener; he may withhold sight of the conversational partner until s/he speaks. The effect, heightened by the lengthy takes, is to turn many of these scenes into monologues, in which a character pours out his or her reaction to a situation, and we’re forced to take that in more or less pure form.

By the end of Family Nest, Tarr is shooting entire scenes concentrated on a single face, and because we don’t know if there is anyone else present, we have to take the talk as virtually a soliloquy.

It’s as if Tarr invoked the stylistic schema of shot/ reverse shot and simply postponed or suppressed the reverse shot, leaving only an inexpressive shoulder in the foreground, if that. I’ve discussed the delayed reverse-shot as a convention of European cinema in an earlier blog, and Tarr makes ingenious use of it.

Tarr builds these films out of conversational blocks, punctuated by undramatic routines. The result is that often major plot actions take place offscreen, or rather in between the dialogues. Exposition that other filmmakers would give us up front is long delayed, with bits of information sprinkled through the entire film. In Family Nest, the father claims that he’s seen Iren having an affair with another man. We can’t be sure he’s lying because we haven’t strayed enough out of the household to judge her activities. In The Outsider, one scene ends with the drifter Andras telling Kata, a woman he has recently met, that he has a child by another woman. The scene ends with him smiling in indifference, leaving his sentence unfinished. In the next scene, a band strikes up a tune: Andras and Kata are celebrating their marriage.

Most filmmakers would show us more of the courtship and a scene of proposal, but Tarr moves directly to the next block, suggesting Andras’ laid-back heedlessness. Agreeing to get married is no big deal. Further, by skipping over the most obviously dramatic incidents, Tarr’s storytelling joins that tradition of ellipsis celebrated by André Bazin in his essays on neorealism. No longer does the filmmaker have to show us every link in the causal chain, and no longer are some scenes peaks and others valleys. By deleting the obviously dramatic moments, the filmmaker forces us to concentrate on more mundane preambles and consequences.

This block construction yields an unusually objective narration. These films lack voice-overs, subjective flashbacks, dreams, and other tactics of psychological penetration. We have to watch the people from the outside, appraising them by what they say and do. It is a behavioral cinema. True, Prefab People opens with a flashback: The husband is packing to leave his wife, and the plot moves back to an anniversary dinner that ends badly. But the flashback to the earlier phase of the marriage isn’t framed as the wife’s memory. When the plot’s chronology brings us back to the moment of the husband’s departure, the replay of the opening allows us to watch the characters with more knowledge of what is driving them apart. Unsurprisingly if you know Tarr’s earlier films, that replay is followed by a long monologue showing the wife expressing her sorrow at his departure, without any visual cues about who, if anyone, is listening.

Then, without preparation, we see the couple back together, shopping in an appliance store. How did they reconcile? Have their attitudes changed, or are they simply reconciled to their old life? Like Antonioni and many other modern filmmakers, Tarr doesn’t tell us such things. He simply ends his film on a long take of husband and wife riding expressionless in the back of a truck, as much pieces of cargo as the washing machine beside them.

After the Fall

The second-phase films do look and feel rather different. Almanac of Fall (1984), a story of duplicity and spite among people sponging off a well-to-do older woman, offers a wholly elegant mise-en-scene. Characters are often framed from far back, surroundings take on much more importance, the framing is stable—often with windows, doors, and furnishings impeding our view of the action—and the camera moves smoothly, often in arcs around stationary figures. The takes are even longer, averaging just under a minute. The rococo lighting (patches of color seem to follow actors around) and atmosphere of strained upper-class narcissism seem like quite a break from the working-class films. If I had to find an analogy to Almanac of Fall, it would be Fassbinder’s Chinese Roulette (1976), with its camera arabesques and slightly decadent ostentation.

The overripe shots of Almanac of Fall signaled a shift toward a self-consciously formal cinema, but then Tarr stripped his settings and cinematography down. From Damnation (1988) onward, his films feature ruined exteriors, shabby interiors, elaborate chiaroscuro, rhythmic camera movement, and very long takes. (Damnation has an ASL of 2 minutes; Sátántangó, 2 minutes 33 seconds; Werckmeister Harmonies, 3 minutes 48 seconds).

Tarr insisted in conversation with me that there isn’t a sharp break between early and late styles. For one thing, his video piece Macbeth (1982) consists of only two shots across 63 minutes. It was made before The Prefab People, so his shift toward the ambulatory long take was already in the works. Moreover, The Outsider ends with a strained restaurant encounter captured in a virtuoso handheld shot running nearly seven minutes. A nightclub scene in The Prefab People likewise features some sidewinding long takes around a dance floor that wouldn’t be out of place, at least in their repetitive geometry, in Damnation.

If we’re inclined to look for other continuities, we can find them. In the films from Damnation onward, the deferred reverse shot has been put at the service of attached point of view, so that often when Tarr’s protagonists peer around a corner or out of a window, instead of optical pov cutting we have an over-the-shoulder view that conceals their facial reaction. One scene in Damnation starts as a typically Tarrian scrutiny of texture, with the wrinkling wall echoing Karrer’s topcoat. But then the camera arcs and refocuses, showing what Karrer is watching but not how he responds.

The blocklike construction of scenes in the early films carries on in the later work, but now Tarr minimizes the cuts within a scene, so that it becomes an even more massive hunk of space and time. Tarr refuses as well to use crosscutting, which would show us various characters pursuing their activities at roughly the same time—another strategy that keeps us fastened to one relentlessly unfolding chain of actions and, usually, one character’s range of knowledge. The avoidance of crosscutting will have major structural implications in Sátántangó, which overlaps characters’ individual points of view by replaying certain events and stretches of time.

The long-held facial shots of the early films don’t create a natural arc; the shot will go on as long as the character wants to talk. Similarly, many long takes in the later films don’t present a beginning-middle-end structure. We simply follow a character walking toward or away from us, pushing into a stretch of time whose end isn’t signaled in any way. This becomes especially clear in those extended long shots in which a character walks away toward the horizon and the camera stays put. Traditionally, that signals an end to the scene, but Tarr holds the image, forcing us to watch the character shrink in the distance, until you think that you’ll be waiting forever. Likewise, the diabolical dance shots of Sátántangó, built on a wheezing accordion melody that seems to loop endlessly, are exhausting because no visual rhetoric, such as a track in or out, signals how and when they might conclude. Early and late, Tarr won’t hold out the promise of a visual climax to the shot, as Angelopoulos does; time need not have a stop.

Nonetheless, I do agree with my fellow panelists that the later films have a significantly different look and feel, and it’s on them that Tarr’s place in world film history will chiefly rest. As I indicated at the end of Figures Traced in Light, he stands out as a distinctive creator in a contemporary tradition of ensemble staging. Like Tarkovsky, he shifts our attention from human action toward the touch and smells of the physical world. Like Antonioni and Angelopoulos, he employs “dead time” and landscapes to create a palpable sense of duration and distance. Like Sokurov in Whispering Pages (1993), he takes us into an eerie, Dostoevskian realm where characters are cruel, possessed, mesmerized, humiliated, and prey to false prophets.

Ties to tradition

Tarr, however, maintains that his work, early or late, owes little to cinema. He claims not to have been influenced by other directors, and he asserts that he gets his ideas from life, not from films. When pressed, he admits that he knew the films of Miklós Jancsó “and I liked them very much. But I think what he does is absolutely different from what we do.”

It’s not uncommon for strong creators to reject the idea of influence, and many feel that they may sap their originality if they’re exposed to other work. Still, nothing comes from nothing. Any artwork is linked to others through an expanding network of affinity and obligation. Often influence is like influenza; you catch it unawares, despite your efforts to ward it off. And sometimes artists on their own find strategies that other artists have already or simultaneously hit upon.

Whether or not Tarr consciously joined a tradition, his practices do link him to several trends. Tarr has rejected the idea, floated by Jonathan, that his early films are indebted to Cassavetes, but there seems little doubt that by 1979, when Family Nest was released, it contributed to the fictional-vérité tradition, regardless of his intent. Likewise, his late films’ reliance on long takes is part of a broader tendency in European cinema after World War II. The neorealists taught us that you could make a film about a character walking through a city (The Bicycle Thieves, Germany Year Zero), and other directors, such as Resnais in the second half of Hiroshima mon Amour, developed this device. With Antonioni, Dwight Macdonald noted, “the talkies became the walkies.” Jancsó took Antonioni further (acknowledging the influence) in the endless striding and circling figures of The Round-Up, Silence and Cry, and The Red and the White. So even if there wasn’t any direct influence, Antonioni and Jancsó paved the way for Tarr; they made such walkathons as Sátántangó and Werckmeister thinkable as legitimate cinema.

Still more broadly, as Hollywood cinema has become faster-paced, accelerating its action and cutting, art cinema in Asia and Europe has tended toward ever slower rhythms. Visit any festival today, as Scott mentioned in our panel, and you’ll see plenty of films with long takes and fairly static staging. I criticize this fashion a bit in Figures, but it’s undeniably a major option on today’s menu. It’s even been picked up in contemporary American indies, with Gus Van Sant’s work from Elephant on offering prominent examples. He, of course, has been crucially influenced by Tarr, but Hou, Tsai Ming-liang, Sokurov, and other directors haven’t. We seem to have a case of stylistic convergence, with Tarr choosing to explore the long take at the same time others were doing so.

Within recent Hungarian cinema, it would be fruitful to examine Tarr’s relation to his contemporaries. Janós Szasz’s Woyzeck (1994) takes place in a wasteland not unlike those of Damnation and Sátántangó. Even closer to Tarr is the work of György Fehér. I’ve seen only Passion (1998; right) and one scene from Twilight (1990). Here again we get very long takes with a supple camera, grungy settings, and down-at-heel characters wandering in rain and mist or dancing as if possessed by demons. Fehér has worked with Tarr as producer, dialogue writer, and “consultant.” We could also explore Tarr and Fehér’s affinities with Benedek Flieghauf, the younger director of The Forest (2003) and Dealer (2004). Fleghauf builds these films around extensive long takes, and the remarkable Forest carries the idea of the suppressed reverse-shot to an eerie extreme, as characters study mysterious offscreen objects that may never be shown us.

Within recent Hungarian cinema, it would be fruitful to examine Tarr’s relation to his contemporaries. Janós Szasz’s Woyzeck (1994) takes place in a wasteland not unlike those of Damnation and Sátántangó. Even closer to Tarr is the work of György Fehér. I’ve seen only Passion (1998; right) and one scene from Twilight (1990). Here again we get very long takes with a supple camera, grungy settings, and down-at-heel characters wandering in rain and mist or dancing as if possessed by demons. Fehér has worked with Tarr as producer, dialogue writer, and “consultant.” We could also explore Tarr and Fehér’s affinities with Benedek Flieghauf, the younger director of The Forest (2003) and Dealer (2004). Fleghauf builds these films around extensive long takes, and the remarkable Forest carries the idea of the suppressed reverse-shot to an eerie extreme, as characters study mysterious offscreen objects that may never be shown us.

More generally, and more speculatively, we could look to a wider movement in late and post-Soviet art toward mournfulness and lamentation in response to cultural collapse. Tarkovsky’s Nostalghia is one instance, but Larissa Shepitko’s The Ascent (1976) and Elem Klimov’s Come and See (1985) point in this direction too. Vitaly Kanevsky’s Freeze, Die, Come to Life! (1989) offers a rusting, dilapidated world not far from Tarr’s. In the 1970s and 1980s, composers like Arvo Pärt, Henryk Górecki, Giya Kancheli, Vyacheslav Artyomov, and Valentin Silvestrov created austere, threnodic music that sometimes evokes spirituality but just as often suggests a bleak end to everything. The very titles—Symphony of Sorrowful Songs (Górecki), Symphony of Elegies (Artyomov), Postludium (Silvestrov)—evoke something more than the death rattle of Communism. The pieces can be heard as meditations on the ruins of modern history, asking what humankind has accomplished and what can come next. Tarr’s severe parables, grotesque and sarcastic in the manner of Kafka, don’t exude the religiosity we can find in some of this music or filmmaking, but, at least for me, they share the impulse to lament humans’ inability to transcend their brutish ways. “I just think about the quality of human life,” he remarks, “and when I say ‘shit’ I think I’m very close to it.”

I have more ideas about Tarr, especially on Sátántangó and Werckmeister, but I have to stop somewhere. I hope to see his new film The Man from London when I go to the Vancouver International Film Festival next week, and of course I’ll report on it here.

The best piece of writing I know on Tarr’s cinema is András Bálint Kovács’ “The World According to Tarr,” in the catalogue Béla Tarr (Budapest: Filmunio, 2001).

Béla mesmerizes Lola, Chicago 15 September 2007.

Thanks to Milos Stehlik, Susan Doll, Charles Coleman, and Megan Rafferty of Facets, to Béla Tarr for generous conversation, and to András Kovács for enlightening discussions over the years.

PS 20 September: The reports of Tarr’s earlier visit to Minneapolis are emerging; here’s a good link.

[insert your favorite Bourne pun here]

DB here:

You may be tired of hearing about The Bourne Ultimatum, but the world isn’t.

It’s leading in the international market ($52 million as of 29 August) and has yet to open in thirty territories. It’s expected, as per this Variety story, to surpass the overseas total of $112 for the previous installment, The Bourne Supremacy. According to boxofficemojo.com, worldwide theatrical grosses for the trilogy are at $721 million and counting. Add in DVD and other ancillaries, and we have what’s likely to be a $2-$3 billion franchise.

There’s every reason to believe that the success of the series, plus the critical buzz surrounding the third installment, will encourage others to imitate Paul Greengrass’s run-and-gun style. In an earlier blog, I tried to show that despite Greengrass’s claims and those of critics:

(1) The style isn’t original or unique. It’s a familiar approach to filmmaking on display in many theatrical releases and in plenty of television. The run-and-gun look is one option within today’s dominant Hollywood style, intensified continuity.

(2) The style achieves its effect through particular techniques, chiefly camerawork, editing, and sound.

(3) The style isn’t best justified as being a reflection of Jason Bourne’s momentary mental states (desperation, panic) or his longer-term mental state (amnesia).

(4) In this case the style achieves a visceral impact, but at the cost of coherence and spatial orientation. It may also serve to hide plot holes and make preposterous stunts seem less so.

I got so many emails and Web responses, both pro and con, that I began to worry. Did I do Ultimatum an injustice? So I decided to look into things a little more. I rewatched The Bourne Identity, directed by Doug Liman, and Greengrass’s The Bourne Supremacy on DVD and rewatched Ultimatum in my local multiplex. My opinions have remained unchanged, but that’s not a good reason to write this followup. I found that looking at all three films together taught me new things and let me nuance some earlier ideas. What follows is the result.

For the record: I never said that I got dizzy or nauseated. The blog entry did, however, try to speculate on why Greengrass’s choices made some viewers feel queasy. Some of those unfortunates registered their experiences at Roger Ebert’s site. For further info, check Jim Emerson’s update on one guy who became an unwilling receptacle.

Another disclaimer: For any movie, I prefer to sit close to the screen. In many theatres, that means the front row, but in today’s multiplexes sitting in the front row forces me to tip back my head for 134 minutes. So then I prefer the third or fourth row, center. From such vantages I’ve watched recent shakycam classics like Breaking the Waves and Dogville, as well as lesser-known handheld items like Julie Delpy’s Looking for Jimmy. My first viewing of Ultimatum was from the fifth row, my second from the third. (1)

Finally: There are spoilers ahead, pertaining to all three films.

How original?

Someone who didn’t like the films would claim that they’re almost comically clichéd. We get titles announcing “Moscow, Russia” and “Paris, France.” You can poke fun at lines of dialogue like “What connects the dots?” and “You better get yourself a good lawyer” and the old standby “What are you doing here?” But these are easy to forgive. Good films can have clunky dialogue, and you don’t expect Oscar Wilde backchat in an action movie.

More significantly, all three films are quite conventionally plotted. We have our old friend the amnesiac hero who must search for his identity. Neatly, the word bourne means a goal or destination. It also means a boundary, such as the line between two fields of crops–just as our hero is caught between everyday civil law and the extralegal machinery of espionage.

The film’s plot consists of a series of steps in the hero’s quest. Each major chunk yields a clue, usually a physical token, that leads to the next step. Add in blocking figures to create delays, a hierarchy of villains (from swarthy and unshaven snipers to jowly, white-haired bureaucrats), a few helpers (principally Nicky and Pam), and a string of deadlines, and you have the ingredients of each film. (Elsewhere on this site I talk about action plotting.) The last two entries in the series are pretty dour pictures as well; the loss of Franka Potente eliminates the occasional light touch that enlivened Bourne Identity right up to her nifty final line

All three films rely on crosscutting Bourne’s quest with the CIA’s efforts to find him, usually just one step behind. Within that structure most scenes feature stalking, pursuits, and fights. In the context of film history, this reliance on crosscutting and chases is a very old strategy, going back to the 1910s; it yields one of the most venerable pleasures of cinematic storytelling.

Mixed into the films is another long-standing device, the protagonist plagued by a nagging suppressed memory. Developing in tandem with the external action, the fragmentary flashbacks tease us and him until at a climactic moment we learn the source: in Supremacy, Bourne’s murder of a Russian couple; in Ultimatum, his first kill and his recognition of how he came to be an assassin. The device of gradually filling in the central trauma goes back to film noir, I think, and provides the central mysteries in Hitchcock’s Spellbound and Marnie.

By suggesting that the films are conventional, I don’t mean to insult them. I agree with David Koepp, screenwriter of Jurassic Park and Carlito’s Way, who remarks:

There are rules and expectations of each genre, which is nice because you can go in and consciously meet them, or upend them, and we like it either way. Upend our expectations and we love it—though it’s harder—or meet them and we’re cool with it because that’s all we really wanted that night at the movies anyway. (2)

There can be genuine fun in seeing the conventions replayed once more.

The series makes some original use of recurring motifs, the most obvious being water. The first shot of the first film shows Jason floating underwater; in the second film he bids farewell to the drowned Marie underwater; and in the last shot of no. 3, we see him submerged in the East River, closing the loop, as if the entire series were ready to start again. There’s also a weird parallel-universe moment when Pam tells Jason his real name and birthdate. She does it in 2, and then, as if she hasn’t done it before, tells him again in 3, in what seem to be exactly the same words. In 3, though, it has a fresh significance as a coded message, and a new corps of CIA staff is listening in, so probably the second occurrence is a deliberate harking-back. Or maybe Bourne’s amnesia has set in again. [Note of 9 Sept: Oops! Something that’s going on here is more interesting than I thought. See this later entry.]

The look of the movies

The big arguments about Ultimatum center on visual style. The filmmakers and some critics, notably Anne Thompson, have presented the style as a breakthrough. But again, the movie is more traditional than it might first appear.

In a film of physical action, the audience needs to be firmly oriented to the space and the people present. The usual tactic is to present transitional shots showing people entering or leaving the arena of action. What might be filler material in a comedy or drama—characters driving up, getting out of their vehicles, striding along the pavement, entering the building—is necessary groundwork in an action sequence. So we see Bourne arriving on the scene, then his adversaries arriving and deploying themselves, in the alternation pattern typical of crosscutting. Surprisingly, for all the claims made about the originality of Greengrass’s style in 2 and 3, he is careful to follow tradition and give us lots of shots of people coming and going, setting up the arena of confrontation.

Then the director’s job is just beginning. Traditionally, once the scene gets going, the positions and movement of the figures in the action arena should be clearly maintained. Likewise, it’s considered sturdy craftsmanship to delineate the overall space of the scene and quietly prepare the audience for key areas—possible exits, hiding places, relations among landmarks. (See this entry for how one modern director primes spaces in an action scene.) I claimed in the earlier entry that such basic orienting tasks aren’t handled cogently in Ultimatum, and a second viewing of the scene in Waterloo Station and the chase across the Tangier rooftops hasn’t made me change that opinion. Later I’ll discuss how Greengrass and some commentators have defended the loss of orientation in such scenes.

All the films in the trilogy employ traditional strategies of setting up the action sequences, but the series displays an interesting stylistic progression. In Identity, Liman gives us mostly stable framings and reserves handheld bits for moments of tension and point-of-view shots. He saves his fastest cutting for fights and chases.

Supremacy displays a more mixed style. It contains passages of wobbly, decentered framing, but those exist alongside more traditionally shot scenes—stable framing, with smooth lateral dollying and standard establishing shots. There are some aggressive cuts, as in the crisp emphasis on the sniper at the start of the first pursuit, but on the whole the editing isn’t more jarring than usual these days. We also get, as I mentioned in the earlier entry, some almost willfully obscure over-the-shoulder shots, and occasionally we get the eye-in-the-corner technique that would become more prominent in Ultimatum.

As we’d expect, in Supremacy the bounciest camerawork and choppiest editing are found in the sequences of the most energetic physical action. Most of the surveillance scenes get a little bumpy, while the chases are wilder. The most extreme instance, I think, is the very last chase in the tunnel, when Bourne avenges the death of Marie and slams the sniper’s vehicle into an abutment. As in Identity, Supremacy arrays its technique along a continuum, saving the most visceral techniques for the most brusing action sequences.

So Ultimatum raises the stakes by applying the run-and-gun style more in a more thoroughgoing way. Everything is dialed up a notch. The flashbacks are more expressionistic than those of Supremacy: instead of dark hallucinations we get blinding, bleached-out glimpses of torture and execution, in staggered and smeared stop-frames. The conversation scenes are bumpier and more disjointed; the cat-and-mouse trailings are more disorienting, with jerky zooms and distracted framings; the full-bore action scenes are even more elliptical and defocused. It’s as if the visual texture of Supremacy’s tunnel chase has become the touchstone for the whole movie.

That texture I tried to describe in the earlier entry. Greengrass relies on camerawork, cutting, and sound to convey the visceral impact of action, rather than showing the action itself. The most idiosyncratic choices include framing that drifts away from the subject of the shot, oddly offcenter compositions, and a rate of cutting that masks rather than reveals the overall arc of the action. Some critics have liked the film’s technique, some have hated it, but I think my account stands as a fair account of the destabilizing tactics on the screen, and a likely source of some spectators’ vertigo.

Run-and-gun, with a gun

The style of Ultimatum is a version of what filmmakers call run-and-gun: shot-snatching in a pseudo-documentary manner. This approach has a long history in American film. The bumpy handheld camera, I tried to show in The Way Hollywood Tells It, has been repeatedly rediscovered, and every time it’s declared brand new. I have to admit I’m startled that critics, who probably have seen Body and Soul, A Hard Day’s Night, The War Game, Seven Days in May, or Medium Cool, continue to hail it as an innovation. Today it’s a standard resource for fictional filmmaking, to be used well or badly.

What’s at issue here are the role it plays and the effects it achieves. In Lars von Trier’s The Idiots, I’d argue that handheld work becomes genuinely disorienting because the camera is scanning the scene spontaneously to grab what emerges. But von Trier’s roaming camera yields rather long takes compared to what we find in the Bourne series. Greengrass is practicing what I called, in Film Art and The Way Hollywood Tells It, intensified continuity.

This approach breaks down a scene so that each shot yields one, fairly straightforward piece of information. The hero arrives at the station. Car pulls up; cut to him getting out; cut to him walking in. Traditional rules of continuity—matching screen direction, eyelines, overall positions in the set—are still obeyed, but the dialogue or physical action tends to be pulverized into dozens of shots, each one telling us one simple thing, or simply reiterating what a previous shot has shown. (Oddly, sometimes intensified continuity seems more, rather than less, redundant than traditional continuity cutting.)

Within the intensified continuity approach, we can find considerable variation. I argued that one highly mannered version can be found in Tony Scott’s later work, where the shots are fragmented to near-illegibility and treated as decorative bits. You can find Scott’s signature look tawdry and overwrought, but Liman and Greengrass belong in the same tradition. All three directors rely on telephoto lenses, for example, and they have recourse to well-proven techniques for rendering hallucinatory states of mind, as in these multiple-exposure shots, one from Man on Fire and the second from Bourne Supremacy.

Despite the stylistic differences among the three Bourne films, the basic one-point-per-shot premises remain in place. Here’s a passage from Supremacy. Jason gets off the train in Moscow. We get an establishing shot of the station as the train pulls in, followed by a shot of him getting off, moving left to right. The establishing shot is a smooth craning movement down, but the following shot is a little shaky.

Then we get a blurry shot of him walking, taken with a very long lens. A head-on shot like this traditionally creates a transition allowing the filmmaker to cross the axis of action, letting Jason walk right to left in the next shot.

Cut to closer view: Jason turns his head slightly. Cut to what he sees, in a shaky pov: Cops.

The answering handheld shot shows Jason reacting. As he strides on purposefully, a still closer shot accentuates his eye movement and adds a beat of tension.

Jason turns and goes to the pay phones, followed by the unsteadicam, then turns his head watchfully. A smooth match-on-action cut brings us closer.

But then Jason turns back to his task, and suddenly a passerby blots out the frame.

When the frame clears, a jouncy shot shows Jason’s hands thumbing a phone book. This might be a continuation of the same shot, or the result of a hidden cut. I suggest in The Way Hollywood Tells It that such stratagems are common in intensified continuity: blotting out the frame, flashing strobe lights, and other devices can create a pulsating rhythm akin to that of cutting. Jason turns the pages, and a jump cut shows him on another page.

Cut back to him scanning the pages. He writes down an address, in a very shaky framing.

Cut back again to Jason, and another smooth match-on action brings us back to the slightly fuller framing we’ve seen already. Greengrass shoots with at least two cameras simultaneously, which can facilitate match-cutting like this.

Jason strides toward us, going out of focus. Then a stable long shot pans with him, moving left as before. He leaves the station.

A very simple piece of action has been broken into many shots, some of them restating what we’ve already seen. In the days of classic studio filming, most directors wouldn’t have given us so many shots of Bourne leaving the train platform; a single tracking shot would have done the trick. A single shot could have shown us Jason at the phone, scribbling down the address. As a result, the whole passage is cut faster than in the classic era. The sequence lasts only forty-one seconds but shows sixteen shots. Two to three seconds per shot is a common overall average for an action picture today. The rapid cutting helps create that bustle that Hollywood values in all its genres.

It’s clear, I think, that here the run-and-gun technique is laid over the premises of intensified continuity, letting each shot isolate a bit of narrative information to make sure we understand, even at the risk of reiterating some bits. Jason has arrived in Moscow, he has to be careful because cops are everywhere, now he needs an address, he finds it, he’s writing it down . . . . All of this action is bookended by long shots that pointedly show us the character arriving at the station and leaving it.

I suggested in the earlier entry that in Ultimatum, Greengrass takes more risks than in the previous film. He still assigns one piece of information per shot, but now that piece is sometimes not in focus, or slips out of the center of the frame, or is glimpsed in a brief close-up. The September issue of American Cinematographer, which arrived as I was completing this entry, explains that he encouraged his camera operators to follow their own instincts about focus and composition. (3) Seeing Ultimatum again, I realized that the film can get away with this sideswiping technique by virtue of certain conventions of genre and style.

A telltale clue, like the charred label left over from a car bomb, can be given a fleeting close-up because physical tokens are carrying us from scene to scene throughout the film and we’re on the lookout for them. A sniper racing away out of focus in the distance is a character we’ve seen before, and he’s spotted in frame center before he dodges away. The larger patterning of shots relies on crosscutting or point-of-view alternation (Jason looks/ what he sees/ Jason reacts), and so the framing of any shot can be a little less emphatic. Given intensified continuity’s emphasis on tight close-ups for dialogue, faces can be framed a little loosely, trusting us to pick up on what matters most—changes in facial expression.

In short, because there’s only one thing to see, and it’s rather simple, and it’s the sort of thing we’ve seen before in other films and in this film, it can be whisked past us. This tactic crops up from time to time in Liman’s first installment, when a shot seems to fumble for a moment before surrendering the key piece of data. For example, Jason is striding through the hotel and a wobbly point-of-view shot brings the hotel’s evacuation map only partly into view.

Again, Greengrass takes a visual device that was used occasionally in Identity and extends it through an entire film.

Realism, another word for artifice

Finally, what’s the purpose behind Ultimatum’s thoroughgoing exploitation of run-and-gun? I quoted Greengrass’s claim that it conveys Bourne’s mental states, and some critics have rung variations on this. Of course the cutting is choppy and the framing is uncertain. The guy’s constantly scanning his environment, hypersensitive to tiny stimuli. Besides, he’s lost his memory! Yet the same treatment is applied to scenes in which Bourne isn’t present—notably the scenes in CIA offices. Is Nicky constantly alert? Is Pam suffering from amnesia?

Alternatively, this style is said to be more immersive, putting us in Bourne’s immediate situation. This is a puzzling claim because cinema has done this very successfully for many years, through editing and shot scale and camera movement. Don’t Rear Window and the Odessa Steps sequence in Potemkin and the great racetrack scene in Lubitsch’s Lady Windermere’s Fan thrust us squarely into the space and demand that we follow developing action as a side-participant? I think that defenders need to show more concretely how Greengrass’s technique is “immersive” in some sense that other approaches are not. My guess is that that defense will go back to the handheld camera, distractive framing, and choppy cutting . . . all of which do yield visceral impact. But why should we think that they yield greater immersion?

I think we get a clue by recalling that Supremacy and Ultimatum display the run-and-gun strategy that Greengrass employed in Bloody Sunday and United 93. This approach implies something like this: If several camera operators had been present for these historic events, this is something like the way it would have been recorded. We get a reality reconstructed as if it were recorded by movie cameras. I say cameras because we’re telling a story and need to change our angles constantly; a scene couldn’t approximate a record of the event as experienced by a single participant or eyewitness. In movies, the camera is almost always ubiquitous.

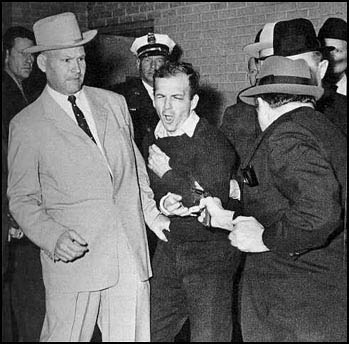

Recall the famous TV footage of Jack Ruby shooting Lee Harvey Oswald. There the lone camera lost some of the most important information by being caught in the crowd’s confusion and swinging wildly away from the action. But in a fiction film, we can’t be permitted to miss key information. So with run-and-gun, the filmmakers in effect cover the action through a troupe of invisible, highly mobile camera operators. That’s to say, another brand of artifice.

In general, the run-and-gun look says, I’m realer than what you normally see. In the DVD supplement to Supremacy, “Keeping It Real,” the producers claimed that they hired Greengrass because they wanted a “documentary feel” for Bourne’s second outing. Greengrass in turn affirms that he wanted to shoot it “like a live event.” And he justifies it, as directors have been justifying camera flourishes and fast cutting for fifty years, as yielding “energy. When you get it, you get magic.” (4)