Archive for the 'Film technique: Cinematography' Category

Unsteadicam chronicles

DB again:

A spectre is haunting contemporary cinema: the shaky shot.

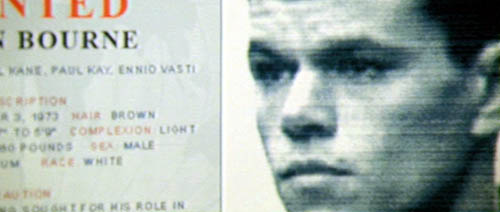

Viewers have been protesting for some years now. I recall friends asking me why the images were so bumpy in Woody Allen’s Husbands and Wives and Lars von Trier’s Dancer in the Dark. The Bourne Ultimatum, this summer’s wildest excursion into Unsteadicam, has put the matter back on the agenda.

If you drop in at Roger Ebert’s website, you’ll find many annoyed comments from readers about what one calls the Queasicam. The writers make shrewd points about the purpose and effects of director Paul Greengrass’s technique. I’ll try to add some historical perspective and a little analysis.

From whose Bourne no traveling shot returneth

First, what exactly are we talking about? Some viewers and critics think the jarring quality of the movie proceeds from rapid editing. The cutting in Bourne Ultimatum is indeed very fast; there are about 3200 shots in 105 minutes, yielding an average of about 2 seconds per shot. But there are other fast-cut films that don’t yield the same dizzy effects, such as Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow (1.6 seconds average), Batman Begins (1.9 seconds), Idiocracy (1.9 seconds), and the Transporter movies (less than 2 seconds).

As for the series itself, The Bourne Identity, directed by Doug Liman, was edited a tad slower, averaging 3 seconds per shot. The second entry, The Bourne Supremacy, also signed by Greengrass, was as fast-cut as this, coming in at 1.9 seconds. People noticed the rough texture of the second one, but it didn’t arouse the protests that this last installment does. Something else is up.

Partly, it’s not the pace of the editing but the spasmodic quality of it. Cuts here seem abrasive because they interrupt actions and camera movements. Pans, zooms, and movements of the actors are seldom allowed to come to rest before the shot changes. This creates a strong sense of jerkiness and visual imbalance.

Still, a lot of the film’s effect has to be laid at the handheld camera. The technique in itself, however, shouldn’t shock us. The handheld aesthetic has been with us a long time. There were silent-era experiments with the technique by E. A. Dupont (Variety, 1925) and Abel Gance (Napoleon, 1927). It recurred sporadically after that, but in mainstream cinema handheld shooting became common in 1960s films as different as The Miracle Worker, Seven Days in May, Dr. Strangelove, and the dramas of John Cassavetes. Today, many films from Asia and Europe as well as the US rely on the device all the way through. The Danes call it the “free camera,” and I write about it here. The trend is so widespread that it’s been satirized: In the Danish comedy Clash of Egos (2006), when an ordinary workman gets a chance to direct a movie, he insists that the camera be put on a tripod, and the cinematographer complains that he hasn’t done this since film school. Directors nowadays tell us that they are in search of energy, a moment-by-moment spiking of audience interest. You can get it through fast cutting, arcing camera movements, sudden frame entrances, the nervousness of the handheld shot, or all of the above.

Roughhouse

I think the upsetting qualities of the visuals in The Bourne Ultimatum derive principally from the particular way the handheld camera is used. Several of Ebert’s writers complain that the camerawork made them nauseated, and there seems little doubt that the shots are bouncier and jerkier than in much handheld work. Adding to the effect is the fact that Greengrass often doesn’t try to center or contain the main action. Sometimes, as in a fight scene, the camera is just too close to the action to show everything, so it tries to grab what it can. At other times Greengrass pans away from the subject, or shoves it to the edge of the 2.40:1 frame. In the standard technique of over-the-shoulder reverse angles, we see one character’s shoulders in the foreground and the primary character’s face clearly. Greengrass likes to let a neck or shoulder overwhelm the composition as a dark mass, so that only a bit of the face, perhaps even just a single eye, is tucked into a corner of the shot. This visual idea was already on offer in The Bourne Supremacy.

In The Way Hollywood Tells It, I described contemporary films as employing “intensified continuity,” an amplification and exaggeration of tradition methods of staging, shooting, and cutting. (I explain a little about it in this blog entry.) What Greengrass has done is to roughen up intensified continuity, making its conventions a little less easy to take in. Normally, for instance, rack-focus smoothly guides our attention from one plane to another. But in The Bourne Ultimatum, when Jason bursts into a corridor close to the camera, the camera tries but fails to rack focus on his pursuer darting off in the distance. The man never comes into sharp focus. Likewise, most directors fill their scenes with close-ups, and so does Greengrass, but he lets the main figure bounce around the frame or go blurry or slip briefly out of view.

Essentially, intensified continuity is about using brief shots to maintain the audience’s interest but also making each shot yield a single point, a bit of information. Got it? On to the next shot. Greengrass’s camera technique makes the shot’s point a little harder to get at first sight. Instead of a glance, he gives us a glimpse.

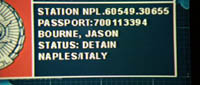

Although this strategy is more aggressive in this third Bourne installment, we can find it as well in Supremacy. An agent pulls a document out of a carryon bag, and for an instant we can see the government seal. In the next shot the agent bobs in and out of the frame, as if the camera can’t anticipate his next move.

Later in Supremacy, the camera jerks across a computer display and suddenly focuses itself, evoking the jumpy saccadic flicks with which we scan our world.

Greengrass claims that his creative choices were influenced by the cinema-vérité documentary school and cites as well The Battle of Algiers, which helped popularize the handheld look in the 1960s. At other times he says that the style is subjective: “Your p.o.v. is limited to the eye of the character, instead of the camera being a godlike instrument choreographed to be in the right place at the right time.” But our point of view isn’t confined to what Bourne or anybody else sees and knows. The whole movie relies on crosscutting to create an omniscient awareness of various CIA maneuvers to trap him. And if Bourne saw his enemies in the flashes we get, he couldn’t wreck them so thoroughly.

The Bourne Ultimatum belongs to a trend of rough-edged stylization sometimes called run-and-gun. The film has been described as bare-bones but it’s actually quite flashy. All the crashing zooms (accompanied by whams on the soundtrack), jittery shots, drifting framings, uncompleted pans, freeze-frame flashbacks, and other extroverted devices call attention to themselves. You can find earlier instances in Oliver Stone’s Natural Born Killers and U-Turn, along with stretches in Michael Mann’s latest films. In milder form you find the style on display in TV crime shows, as well as in the notorious docudrama The Road to 9/11.

The most extreme practitioner of this style is probably Tony Scott. From Spy Game through Man on Fire, Domino, and Déjà vu, he has taken this aesthetic in delirious directions. His framing is often restless, as if groping for the right composition. In this shot from Domino, the camera starts a bit too far to the right, shifts left to frame Frances a little better, zooms back hesitantly, then finally stabilizes itself as he grins at the Motor Vehicles worker.

A single shot may give us not only changes of focus but jumps in exposure, lighting, and color; sometimes it’s hard to say whether we have one shot or several. The result is a series of visual jolts, as in Man on Fire.

Scott, trained as a painter, pushes toward a mannered, decorative abstraction, aided by long-lens compositions and a burning, high-contrast palette. For Supremacy, Greengrass adopted a toned-down version of Scott’s approach, while in Ultimatum, he favors drab surroundings and steely colors. Still, both men’s approaches to run-and-gun are frankly artificial, and both remain within the premises of intensified continuity. Of the Waterloo Station sequence Greengrass says: “It has got a sense of energy.”

The Bourne coverup

There’s one more function of Bourne’s style I want to consider. In an earlier post, I quoted Hong Kong cinematographers’ saying about the shaky camera. The handheld camera covers three mistakes: Bad acting, bad set design, and bad directing. It’s worth considering, as some of Ebert’s correspondents do, what Greengrass’s style may serve to camouflage. One suggests that because the cutting doesn’t let the viewer reconstruct the fights blow by blow, anybody can seem to be a superhero if the filming is flurried enough.

Just as important, the director who is just (apparently) snatching shots doesn’t have to worry about building up performances slowly; s/he can simply give us the most minimal, stereotyped signals in facial close-ups. Lengthier shots let the actor develop the character’s reactions in detail, and force us to follow them. Classic studio cinema, with its more distant framings and longer takes, lets you follow the evolution of a feeling or idea through the actor’s blocking and behavior. The villain in the average Charlie Chan movie displays more psychological continuity than the nasty agents in Bourne Ultimatum.

Moreover, run-and-gun technique doesn’t demand that you develop an ongoing sense of the figures within a spatial whole. The bodies, fragmented and smeared across the frame, don’t dwell within these locales. They exist in an architectural vacuum. In United 93, the technique could work because we’re all minimally familiar with the geography of a passenger jet. But in The Bourne Ultimatum, could anybody reconstruct any of these stations, streets, or apartment blocks on the strength of what we see? Of course, some will say, that’s the point. Jason himself is dizzyingly preoccupied by the immediacy of the action, and so are we. Yet Jason must know the layout in detail, if he’s able to pursue others and escape so efficiently. Moreover, we can justify any fuzziness in any piece of storytelling as reflecting a confused protagonist. This rationale puts us close to Poe’s suggestion that we shouldn’t confuse obscurity of expression with the expression of obscurity.

The run-and-gun style is indeed visceral, but let’s be aware of how it achieves its impact. I’ve argued in Planet Hong Kong that the clean, hard-edged technique of classic Hong Kong films allows extravagant action to affect us viscerally; by following the action effortlessly, we can feel its bodily impact. We’re shown bodies in sleek, efficient movement that gets amplified by cogent framing and smooth matches on action. But in the fancy run-and-gun style, cinematography and sound do most of the work. Instead of arousing us through kinetic figures, the film makes bouncy and blurry movement do the job. Rather than exciting us by what we see, Greengrass tries to arouse us by how he shows it. The resulting visual texture is so of a piece, so persistently hammering, that to give it flow and high points, Greengrass must rely on sound effects and music. As a friend points out, we understand that Bourne is wielding a razor at one point chiefly because we hear its whoosh.

What else does the handheld style conceal? Since the 1980s, in many action pictures the cutting has become so fast, and often capricious, that we can’t clearly see the physical action that’s being executed. That complaint is justified in Bourne Ultimatum, certainly, but here the style also seeks to make the stunts seem less preposterous. Instead of showing cars crashing and flipping balletically, Greengrass barely lets us see the crash. All the conventions of the action film are smudged in Bourne Identity, as if a sketchy rendering made them seem less outlandish. In a Hong Kong film, Bourne in striding flight, grabbing objects to use as weapons without missing a beat, would be presented crisply, showing him executing feats of resourceful grace. But many viewers seem to find this sort of choreography outlandish or cartoony. So when Bourne plucks up pieces of laundry and wraps them around his hands to protect them when he vaults a glass-strewn wall, Greengrass’s shot-snatching conceals the flamboyance of the stunt.

Finally, I’d argue that the style camouflages something else: plot problems. I’m not talking about the hero’s indestructibility, which is a given in this genre. John McClane in Die Hard 4.0 survives about as much mayhem as does Jason Bourne. But there are some howlers here that, because of the rapid pace and the just-barely-visible action, are somewhat muffled. By whisking the action past us and forcing us to keep up, the film doesn’t allow us to dwell on its holes and thin patches.

The plot, praised by so many, is actually a very simple one: Find Guy A, but when he’s killed, locate the clues that will lead you to Guy B, etc. until you get to Mr. Big. The mechanics of how the clues are pursued remain obscure. (Skip ahead to the next paragraph if you haven’t seen the movie.) Why would an all-powerful CIA operation house its key players in offices that can easily be watched from a neighboring building? How does Bourne get into Noah Vosen’s office, past all the security? Is the revelation of Bourne’s identity and his training regimen really much of a surprise? The wrapup, showing the bad guys exposed by the press and punished by government investigation, seemed risible, not only because of the current inability of either press or congress to right any wrongs, but because I had no idea to whom Pamela Landy has faxed the incriminating documents. “You can’t make stuff like this up,” remarks one sinister agency boss, but many, many films have done so.

I’m not against handheld styles as such, and even Late Tony Scott Rococo can have its virtues. Yet I find the style as practiced by Greengrass to be pretty incoherent and nowhere near as engaging as most critics claim. It just seems too easy. But then, I think that certain standards of filmmaking craftsmanship have pretty much vanished, and the run-and-gun trend is one more symptom of that. Given the praise heaped on The Bourne Ultimatum, however, things are unlikely to change. Next time you head to the movies, you might want to bring your Dramamine.

Thanks to Vance Kepley and Jeff Smith for engaging discussion about The Bourne Ultimatum.

The Bourne Supremacy.

PS: I’ve done a followup entry on the Bourne series, elaborating on these points and adding some new ones.

PPS: One more, I hope final, cluster of comments on Ultimatum, this time on the plotting.

PPPS 5 January 2008: Spielberg weighs in on the Bourne style; thanks to Fred Holliday and Brad Schauer for calling my attention to this.

PPPPS 22 September 2008: This blog post and its mates have stimulated critical discussion in Spain. Manuel Garin has a lengthy piece on the Unsteadicam style in Contrapicado.

Bergman, Antonioni, and the stubborn stylists

DB here:

Jonathan Rosenbaum has created quite a stir. His New York Times Op-Ed piece, “Scenes from an Overrated Career,” offers a fairly harsh judgment on the films of Ingmar Bergman. In one sense the timing was awkward; the poor man had just died. But the article wouldn’t have attracted much attention if Rosenbaum had waited a few months, so if creating a cause célèbre was his goal, he chose the right moment.

Timing aside, there wasn’t much in the piece that hasn’t been said by certain cadres of cinephiles for decades. Back in the 1960s, people called Bergman “theatrical,” “uncinematic,” pretentious, and intellectually shallow. He was even accused of hypocrisy. His spiritual, philosophical films always seemed to depend on a surprising number of couplings, killings, rapes, and gorgeous ladies, often naked. Rosenbaum contrasts Bergman with Bresson and Dreyer, more austere religious filmmakers as well as great formal innovators, and this gambit too is familiar from late-night film-society disputes. Jonathan’s case is news in the good, grey Times, but it’s an old story among his (my) generation.

I think that this generational antipathy has many sources. While Bergman had considerable academic cachet, this may have hurt him with smart-alecks like us. Cinephile priests and professors told us that Bergman was a great mind, but we suspected them of snobbery, for they often disdained even foreign filmmakers who dabbled in popular genres. Kurosawa was admired for Rashomon and I Live in Fear rather than for Seven Samurai and Yojimbo. And many of Bergman’s intellectual fans despised the classic tradition of American studio film. Hitchcock had not yet convinced literature profs of his excellence, and Ford was a gnarled geezer who made Westerns. Bergman and his acolytes seemed just too square. Our money was on Godard, especially after Susan Sontag’s magisterial essay on him.

Furthermore, some critics were on our side. Pauline Kael, with her nose for elitism, mocked ambitious European experiments like Marienbad. Andrew Sarris, who had a huge influence on our generation, initially registered respect for the arthouse kings. They proved that an artist could put a personal vision on film, thus buttressing the auteur approach to criticism. But Sarris retreated fairly fast. He was more unflaggingly enthusiastic about American popular cinema, and by contrast he often characterized the new Europeans as gloomy, middlebrow, and narcissistic. (He did, after all, coin the phrase “Antonionennui.”) Sarris made it possible for us to argue that, say, Meet Me in St. Louis was a better film than L’Eclisse or Winter Light. (1)

Of course I’m generalizing; no Boomer’s experience was identical with any other’s. Speaking just for myself, I didn’t have a deep love for Bergman, and I still don’t. I was drawn to his early idylls (Monika, Summer Interlude) and impressed but chilled by the official classics (Smiles of a Summer Night, The Seventh Seal, The Virgin Spring). Persona, I admit, was a punch in the face. Seeing it in its New York opening, I felt that all of modern cinema was condensed into a mere eighty minutes. But no Bergman film afterward measured up to that for me, and after The Serpent’s Egg I just lost interest, catching up with Cries and Whispers, Scenes from a Marriage, Fanny and Alexander, and a very few others over the later decades.

We can talk tastes forever. Maybe you think Bergman is great, or the greatest, or obscenely overrated. I think that there’s something more general and intriguing going on beyond our tastes. What makes this hard to see is that the venues of popular journalism don’t allow us to explore some of the ideas and questions raised by our value judgments.

Critical semaphore

Take some of Rosenbaum’s criticisms, which Roger Ebert has persuasively answered. I’d add that Jonathan is sometimes applying criteria to Bergman that he wouldn’t apply to directors he admires. Bergman isn’t taught frequently in film courses? So what? Neither is Straub/Huillet or Rivette or Bela Tarr. Bergman is theatrical? So too are Rivette and Dreyer, both of whom Rosenbaum has written about sympathetically.

More importantly, Jonathan’s critique is so glancing and elliptical that we can scarcely judge it as right or wrong. A few instances:

*Bergman’s movies aren’t “filmic expressions.” There’s no opportunity in an Op-Ed piece for Jonathan to explain what his conception of filmic expression is. Is he reviving the old idea of cinematic specificity—a kind of essence of cinema that good movies manifest? As opposed to theatrical cinema? I’ve argued elsewhere on this site that we should probably be pluralistic about all the possibilities of the medium.

*Bergman was reluctant to challenge “conventional film-going habits.” Why is that bad? Why is challenging them good? No time to explain, must move on….

*Bergman didn’t follow Dreyer in experimenting with space, or Bresson in experimenting with performance. Not more than .0001 % of Times readers have the faintest idea what Jonathan is talking about here. He would need to explain what he takes to be Dreyer’s experiments with space and Bresson’s experiments with performance.

In his reply to Roger Ebert, Jonathan has kindly referenced a book of mine, where I make the case that Dreyer experimented with cinematic space (and time). Right: I wrote a book. It takes a book to make such a case. It would take a book to explain and back up in an intellectually satisfying way the charges that Jonathan makes.

Popular journalism doesn’t allow you to cite sources, counterpose arguments, develop subtle cases. No time! No space! No room for specialized explanations that might mystify ordinary readers! So when the critic proposes a controversial idea, he has to be brief, blunt, and absolute. If pressed, and still under the pressure of time and column inches, he will wave us toward other writers, appeal to intuition and authority, say that a broadside is really just aimed to get us thinking and talking. But what have we gained by sprays of soundbites? Provocations are always welcome, but if they really aim to change our thinking, somebody has to work them through.

I’ve suggested elsewhere that too much film writing, on paper and on the Net, favors opinion over information and ideas. Opinions, which can be stated in a clever turn of phrase, suit the constraints of publication. Amassing facts and exploring ideas in a responsible way—making distinctions, checking counterexamples, anticipating objections, nuancing broad statements—takes more time. Academics are sometimes mocked for their show-all-your-work tendencies, and I grant that this can be tedious. But we’re just trying to get it right, and that can’t be done quickly.

Now you know why our blog entries are so damn long.

This one is no exception.

Too often film talk slides from being film comment to film chat to film chatter. Even our best critics, among whom Rosenbaum must be counted, make use of a kind of rapid semaphore, signaling to the already converted. Evidently his ideal reader agrees that good cinema is challenging and experimental, directing actresses is a minor talent, and being admired by upscale Manhattanites is a sign of a sellout. Readers will self-select; those who have congruent tastes will pick up the signals. But these beliefs aren’t really knowledge. They’re just, when you get right down to it, attitudes.

I’ll try to explore just one of the issues Jonathan raises but can’t pursue: the question of how stylistically innovative Bergman was. Of course, I can’t write a book here either. I offer what follows as simply the start of what could be an interesting research project.

One stylistic arc

The rise of European arthouse auteurs in film culture of the 1950s and 1960s put the question of personal style on the agenda, but back then we didn’t have many tools for analyzing stylistic differences among directors. We didn’t know much about the local histories of those imported films; as Sarris recently pointed out, L’Avventura was Antonioni’s sixth feature but was his first film released in the US. Moreover, we didn’t know much about the norms of ordinary commercial filmmaking, in the US or elsewhere. (2) Today we’re in a better position to characterize what went on. (3)

In most countries, quality cinema of the late 1940s relied on variations of the Hollywood approach to staging, shooting, and cutting that had emerged in the silent era. Directors moved their performers around the set fairly fluidly and used editing to enlarge and stress aspects of the action. You can see a straightforward example of this approach on an earlier entry on this blogsite.

Many directors of the period built upon this default by creating deep space in staging and framing. Using wide-angle lenses, directors could allow actors to come quite close to the camera, sometimes with their heads looming in the foreground, while other figures could be placed far in the distance. Several planes of action could be more or less in focus. Here’s a straightforward example from William Wyler’s The Little Foxes.

We find directors exploiting this approach not only in the United States but in Eastern and Western Europe, Scandinavia, the Soviet Union, Japan, Mexico, and South America. Here’s an instance from the French film Justice est faite (1950).

Why did this approach emerge in so many countries at the same time? We don’t really know. It wasn’t simply the influence of Citizen Kane, as we might think. The Stalinist cinema had developed deep-space shooting in the 1930s, and we can find it elsewhere. Probably Hollywood’s 1940s films helped spread the style, but there are likely to be local causes in various countries too.

In any event, during the 1950s two technological changes posed problems for this style. One was the greater use of color filming, which renders depth of field much more difficult. The other innovation was anamorphic widescreen, a technology seen in CinemaScope and Panavision. These systems also had trouble maintaining focus in many planes when the foreground was close to the camera. The flagrant depth compositions we find in black-and-white ‘flat’ films were quite difficult to replicate in color and anamorphic widescreen.

Through the 1960s, the deep-focus style became a minor option and directors found other alternatives to presenting character interactions. The most basic one was simply to station the camera at a middle distance and create a more porous and open staging, with fewer planes of action and simple panning movements to follow characters.

One new approach relied not on wide-angle lenses but on lenses of long focal length. Instead of staging scenes in depth, putting the camera close to a foreground figure, filmmakers began keeping the camera back a fair distance and using long lenses to enlarge the action. This accompanied a trend toward greater location shooting; it’s easier to follow actors on a street or highway if the camera shoots with a telephoto lens. The long lens also reduces the volumes of each plane, so that figures tend to look like cutouts (4). This lens facilitated the development of those perpendicular images I’ve called, in some writing and on this blog, planimetric shots.

What fascinates me about this general pattern of stylistic change in the US is how many of the Euro auteurs go along with it. Take Fellini, who shifts from the bold depth compositions of I Vitelloni to the fresco-like flatness of Satyricon.

![]()

Likewise, Luchino Visconti’s early black-and-white work affords textbook examples of deep-focus cinematography, but in the 1960s he embraced the telephoto look, heightened by what we can call the pan-and-zoom tactic. In Death in Venice, the camera often scans a scene, searching out one player to follow then zooming back to reframe the figure in relation to others. One shot starts with the boy Tadzio, pans right across the hotel salon, to end on von Aschenbach, staring at the boy, and then zooming back to take in the larger scene.

Probably Rossellini’s 1960s films, such as Viva l’Italia! and Rise to Power of Louis XIV, were key influences on this look.

Leaving Europe, there’s Kurosawa, who was the first major director I know of to build zoom and telephoto lenses into his style. Satayajit Ray followed much the same trajectory from the Apu trilogy’s flamboyant depth to the pan-and-zoom close-ups of The Home and the World. Not every filmmaker took the long-lens option, but as it became commonplace in the 1960s, many major directors tried it.

What about Bergman? It seems that in most respects he went along with the general trends. We find deeply piled-up bodies early in his career (e.g., Port of Call, below) and through the 1950s and early 1960s (The Face, below).

Like his peers, with color and widescreen he shifted toward more open staging, long lenses, and zooms. For example, one telephoto shot of Cries and Whispers zooms back as the little girl emerges, zig-zagging, from behind the lace curtain.

We might conclude that Bergman mostly worked with the received forms of his day. At the level of shot design, The Face might have been shot by the Sidney Lumet of Fail-Safe. But Bergman did innovate somewhat, I think. Most obviously, he sometimes had recourse to the suffocating frontal close-up, as in a childbirth scene from Brink of Life.

He develops this visual idea by creating heads floating unanchored in both foreground and background. Here’s a famous image from Persona.

Pace Rosenbaum, I’d say that this sequence, with Elisabeth Vogler apparently quite oblivious to her husband’s mating with Alma, definitely “challenges conventional film-going habits”—or at least conventional ways we read a scene. It seems to combine the deep-space, big-foreground scheme of the 1940s with the tight close-ups of Bergman’s early work, and instead of specifying space it undermines it. We have to ask if what happens in the background is Elisabeth’s hallucination.

My case is very schematic, and we would need to study Bergman film by film and scene by scene to confirm that he stuck to the broad norms of his time. The norms themselves also deserve deeper probing than I’ve given them. (5)

But let’s push a bit further and examine Antonioni, that perpetual foil to Bergman. Broadly speaking, he passed through the same arc, from deep-focus compositions in the 1950s and early 1960s to telephoto flatness in his color work. Yet there are some important differences.

In the 1950s, unlike Bergman, Antonioni employed quite intricate staging, sustained by long takes. He usually didn’t opt for big foregrounds, favoring more distant framings and sidelong camera movements. The most famous instance is the startling 360-degree long take on the bridge in his first feature, Story of a Love Affair, but Le Amiche is also full of intricate staging in mid-ground depth. One scene shows fashion models bustling around after a successful show, congratulating the shop’s owner Clelia. She opens a card from her lover, is distracted by the arrival of her friends coming to congratulate her, and goes off with them. One model darts diagonally forward to investigate the message. All of this is handled in a single graceful take.

Antonioni relies on the fluid staging techniques developed in the early sound era and taken in diverse directions by Renoir, Ophuls, Preminger, Mizoguchi, and other directors of the 1930s and 1940s. Often, however, Antonioni’s characters move rather slowly and hold themselves in place, and as a result the overall spatial dynamic unfolds in marked phases. (6)

In the trilogy starting with L’Avventura, Antonioni relies on shorter takes and less florid camera movement. Now he emphasizes landscape and architecture so as to diminish the characters. If the expressionist side of Bergman plays up the psychological implications of the drama, the more austere Antonioni plays things down, “dedramatizing” his scenes by keeping the camera back, turning the figures away from us, and reminding us of the milieu. (You see the Antonioni influence on similar strategies in the work of Edward Yang, as I discussed recently on this blog.)

Once color came along, Antonioni changed his style, moving toward less dense staging and at times almost casual framing (as in The Passenger). He also had recourse to the telephoto technique, but I’d argue he brought something new to it. With Red Desert he accepted the abstraction inherent in the long lens and combined that with color design to create a pure pictorialism.

Ironically, Red Desert may have made Antonioni another sort of ‘expressionist’ than Bergman. The stylized palette of the film encourages us to ask if the industrial landscape is really so smeared and bleached out, or if we’re seeing it as Giuliana does. The same sort of painterly abstraction can be found in Zabriskie Point. In one scene, a pan over the travel decals on a family’s car window treats the boy inside as no more than another thin slice of space. Other scenes turn campus policemen into figures in grids.

You might even argue that the pan-and-zoom style gets a kind of meta-treatment in the climactic shot of The Passenger. There in a grandiose technical gesture Antonioni’s concern for architecture, his refusal to underscore a melodramatic plot twist, and his love of camera movement blend with the technology of the zoom. At the time, several of us (maybe Jonathan too) saw this shot as a response to Michael Snow’s Wavelength, relayed through the sensibility of Passenger screenwriter and avant-garde filmmaker Peter Wollen. Now it looks to me like a natural response of a very self-conscious artist to a stylistic trend of the moment.

A bestiary of stylists

To get crude and peremptory: Let’s say that once a director has reached maturity and become a confident artisan, several choices offer themselves. The filmmaker can be a flexible stylist, a stubborn stylist, or a polystylist (sorry for the awkward term).

A flexible stylist adapts to reigning norms. Bergman could be an aggressive-deep-focus director, then a pan-and-zoom director. Both approaches to staging and shooting preserved the expressive dimensions that mattered most to him: performance (chiefly face and voice), Ibsenesque bourgeois tragedy, Strindbergian play with dream and dissolution of the ego, and other elements.

Most of the major 1960s arthouse directors, from Truffaut and Wajda to Pasolini and Demy, were flexible stylists in this sense. So were a great many Hollywood and Japanese directors, such as Lubitsch and Kinoshita. Perhaps Ousmane Sembene, who also died recently, would be another instance. Buñuel becomes a fascinating case: He adopts the blandest, calmest version of each trend, creating a neutral technique, the better to shock us with what he shows.

A stubborn stylist pursues a signature style across the vagaries of fashion and technology. Dreyer from Vampyr onward does this; I argue in the book Jonathan cites that he seeks to “theatricalize” cinema in a way that goes beyond the norms of his moment. Perhaps Hitchcock and von Sternberg (at least in the 1920s and 1930s) fit in here as well. Bresson, Tati, and supremely Ozu were stubborn stylists. Give them a western or a porno to shoot, and they’d handle each the same way. (7)

This isn’t to argue that stubborn stylists never change or always do the same thing. Mizoguchi has a signature style and yet remains fairly pluralistic, at least at a scene-by-scene level. I think that the test comes in seeing how stubborn stylists persistently explore the constrained conditions they’ve set for themselves.

Signature styles help a filmmaker in the festival market, so we don’t lack for current examples of stubborn creators: Godard, Theo Angelopoulos, Hou Hsiao-hsien, Kitano Takeshi, Tsai Ming-liang, and Jia Zhang-ke. Granted, some of these may be rethinking their commitment to their stylistic premises.

A polystylist tries out different styles without much concern for what the reigning norms demand. Polystylistics holds a high place in modernist aesthetics. After the great triumvirate of Picasso, Joyce, and Stravinsky, with their bewildering arrays of periods and pastiches, the idea of the modernist as a virtuoso steeped in several styles became a powerful option. What’s been called postmodernism is no less favorable to polystylism; if you mix styles, you’ve presumably mastered them.

In cinema, some polystylists are just eclectic. Steven Soderbergh can give us the portentous pictorialism of The Underneath or Solaris, the grab-and-go look of Traffic, and the trim polish of Ocean’s 11. More deeply, there are directors like R. W. Fassbinder, Raoul Ruiz, and Oshima Nagisa who seem to pursue polystylistics on principle. It’s as if, rejecting the very idea of a signature style, they set themselves fresh, severe conditions for each project.

After The Boss of It All, we may want to count von Trier as a polystylist, not merely a director who changed his style from one phase of his career to another. Perhaps the best current example is Aleksandr Sokurov; who would dare predict what his next film will look like?

This whole entry is pretty sketchy, I grant you. The categories need further refining. I’ve ignored sound, which is very important. I’ve emphasized visual style, and just shooting and staging within that. (Nothing about lighting, cutting, etc.) So this is tentative—notes perhaps for a book-length argument. But I’ve made my point if you see that some ideas and some historical information can put intuitions about originality into a firmer framework.

And I’ve left the value judgments suspended. If you think originality trumps other criteria, then Bergman doesn’t probably come up as strong as Antonioni, let alone Bresson or Ozu or Dreyer. But if you can entertain the possibility that a great filmmaker can accept certain norms of his time, making those serve other channels of expression, then Bergman can’t automatically be faulted. At least thinking about him and his peers in the context of the history of film art gives us some data to ground our arguments. The world is more interesting and unpredictable than our opinions, especially those we formulated forty years ago.

(1) I actually hold this opinion.

(2) I assume that the arthouse auteurs were no less commercial filmmakers than their Hollywood counterparts. They were sustained by national film industries and supported by the international film trade. Eventually many were funded by Hollywood companies.

My friend and colleague Tino Balio is at work on a book tracing the role of overseas imports in the American film market of the 1940s-1960s, and it should be a real eye-opener to those who persist in counterposing art cinema and commercial production.

(3) Some of what follows is discussed in Part Four of Film History: An Introduction.

(4) I talk about both the deep-focus and long-lens tendencies in Chapter 6 of On the History of Film Style and Chapter 5 of Figures Traced in Light.

(5) For a wide-ranging account of art-cinema norms, see András Bálint Kovács’ forthcoming book, Screening Modernism: European Art Cinema, 1950-1980.

(6) I analyze this tendency, using other scenes from Le Amiche, in On the History of Film Style (pp. 235-236) and Figures Traced in Light (pp. 151-152).

(7) Suo Masayuki’s My Brother’s Wife: The Crazy Family is a softcore film made in a pastiche of Ozu’s style.

Story of a Love Affair (Cronaca di un amore).

PS, Sunday 12 August: Only a day later, new thoughts about something else I should have said about generational tastes. In the light of the Woody Allen eulogy that appears in the New York Times today, I think there’s more of a sub-generational split than I’d initially suspected. So here’s another gesture toward the sort of history of taste that Jonathan mentions.

Allen is in his seventies, a decade older than Jonathan Rosenbaum and me. He came of age in the affluent decade after the war. Allen saw Bergman films in the mid- to late 1950s, probably against the backdrop of Neorealism, British comedy, and French Cinema of Quality. In that context, Bergman’s movies looked pretty revolutionary.

But Jonathan and I came to maturity, if that’s the right word, in the mid-1960s. When I got to college in 1965, French directors (notably Resnais, Godard, Truffaut) and the Czechs, Hungarians, and others were getting established in US film culture. Bergman, Fellini, and Antonioni were already senior directors and soon they were starting to make what many of us perceived as career mistakes (Juliet of the Spirits, The Passion of Anna, even Blow-Up). Also, of course, concerns about their political alignments came more to the fore as the decade wore on. Many of my friends thought that The Battle of Algiers left all other films in the shade. These factors may have made the Boomers suspicious of “arty” foreign imports, of which Bergman’s work was a central instance. Interestingly, The Dove, a parody of The Seventh Seal and a film-society staple, came out in 1968, when Bergman may have been wearing out his welcome.

[Speaking of parodies, the SCTV skit, “Scenes from an Idiot’s Marriage”, in which Jerry Lewis (Martin Short) suffers the indignities of a cuckolded Bergman hero, is well worth checking out. The SCTV Fellini/ Antonioni parody, “Rome Italian Style,” is also pretty good, especially for its excellently awkward dubbing.]

Interestingly, Scorsese in age falls midway between Allen and us Boomers, and he contributes a Times tribute to Antonioni today. Maybe I have to split the generations even more: Bergman for 1955-1960, Antonioni for 1961-1965, Godard for 1965-1970? (Just kidding.) What strikes me are the differences in the essays. While Allen ranges widely, reports conversations, and praises Bergman in general terms, Scorsese’s piece evokes the texture of L’Avventura, suggesting how disturbing and demanding it was to watch. Maybe he inadvertently backs Jonathan’s claim that Bergman didn’t challenge his audience as much as he might have?

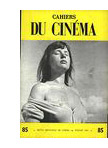

I’m grateful as well to readers responding to my arguments. Michael Kerpan kindly spread the word about my post on imdb and the Criterion Forum. Kent Jones wrote to point out that any argument about Bergman’s influence has to take into account the high regard in which he’s been held in France, among both critics and filmmakers. Kent itemizes not only Godard, Truffaut, and Rivette but Assayas, Téchiné, and Desplechin. It’s a fair point. Antoine de Baecque anchors much of his magisterial history of Cahiers du Cinéma around the mesmerizing power of that busty still of Harriet Anderson, flaunted on a 1958 Cahiers cover and swiped by Antoine in The 400 Blows. In 2003, my old friend Jacques Aumont published a large critical study on Bergman. Cahiers’ next issue will be devoted to the director.

I’m grateful as well to readers responding to my arguments. Michael Kerpan kindly spread the word about my post on imdb and the Criterion Forum. Kent Jones wrote to point out that any argument about Bergman’s influence has to take into account the high regard in which he’s been held in France, among both critics and filmmakers. Kent itemizes not only Godard, Truffaut, and Rivette but Assayas, Téchiné, and Desplechin. It’s a fair point. Antoine de Baecque anchors much of his magisterial history of Cahiers du Cinéma around the mesmerizing power of that busty still of Harriet Anderson, flaunted on a 1958 Cahiers cover and swiped by Antoine in The 400 Blows. In 2003, my old friend Jacques Aumont published a large critical study on Bergman. Cahiers’ next issue will be devoted to the director.

Speaking of French critics and directors, on imdb above Bertrand Tavernier points out that my memory failed. I did see Scenes from a Marriage and Cries and Whispers before The Serpent’s Egg, not after, as my post suggests.

My late Bergman viewing remains gappy. I still haven’t seen the long version of Fanny and Alexander, which everyone assures me is a masterpiece. Last spring, my friend and Bergman scholar Paisley Livingston showed me portions of the TV film The Last Gasp (1995). It’s about Georg af Klercker, the fine Swedish director of the 1910s. It was intriguing, but I was put off by Bergman’s inadequate pastiches of af Klercker’s remarkably poised and complex shots. Now that’s fussy taste, I admit.

Bando on the run

Sakamoto Ryoma (1928).

The Matsuda Eigasha company of Tokyo deserves enormous credit for restoring and making available classic Japanese films. My first visit to the firm twenty years ago was a revelation. Matsuda Shinsui was a former benshi, or spoken-word film accompanist, and he and his sons were collecting old films so that he could accompany them in screenings. A great many of the films were chambara, or swordfight movies. Most survived only in fragments, but what tantalizing fragments they were! (1)

The company made several of the films available on VHS tape, accompanied by benshi commentary prepared by Mr. Matsuda. I came away with several of these treasures. On later visits I was able to watch some films that hadn’t been transferred to video, and several of those deserve to be more widely seen.

When Mr. Matsuda’s son kindly drove me to my train station, I noticed that his car had a VHS player and video monitor installed in the dashboard. So much for my Tokyo-ga experience.

In 1979 Matsuda Eigasha compiled a documentary on the swordplay star Bando Tomasaburo. Now Digital Meme has made it available on DVD, complete with English subtitles. Bantsuma: The Life of Tomasaburo Bando is obligatory viewing for everyone interested in Japanese cinema. Not only does it handily trace Bando’s remarkable career through stills, interviews, and surviving footage. It also supports something I’ve tried to show for some time: that the Japanese action cinema of the 1920s and 1930s was one of the most powerful and creative trends in world filmmaking.

In 1979 Matsuda Eigasha compiled a documentary on the swordplay star Bando Tomasaburo. Now Digital Meme has made it available on DVD, complete with English subtitles. Bantsuma: The Life of Tomasaburo Bando is obligatory viewing for everyone interested in Japanese cinema. Not only does it handily trace Bando’s remarkable career through stills, interviews, and surviving footage. It also supports something I’ve tried to show for some time: that the Japanese action cinema of the 1920s and 1930s was one of the most powerful and creative trends in world filmmaking.

Action and innovation

Some writers have thought that Japanese filmmakers were developing a culturally anchored approach to filmic storytelling independent of Western influences. But in Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema and two essays in my forthcoming Poetics of Cinema, I argue something different. By the early 1920s Japanese filmmakers had mastered Hollywood’s norms of visual storytelling. In the Matsuda documentary, this is evident from the clips from early Bando films like Gyakuryu (1924) and Kageboshi (1924). Long shots are broken up into closer views, and conversations are treated in reverse-angle shots of speaker and listener. Camera movements follow the characters as they walk or run.

So far, so conventional. But many Japanese filmmakers revised the American approach, turning it into something more expressive and experimental. So, for example, a very steep high angle in Kirarazaka (1925) serves at first to show us that Bando is surrounded by fighters who use ladders to try to trap him. As the scene returns to this framing again and again, it becomes more abstract, with the fallen ladders becoming vectors of a geometrical shot design targeting the hero.

An even more remarkable example is Orochi (1925), a Bando film that survives intact and in fine shape. (Matsuda released it on VHS; I don’t think it’s on DVD yet.) The clip in the 1979 documentary shows one of Orochi‘s most dazzling passages. The hero, played by Bando, fights his way through a town, and, backed up against a wall, he’s trapped on all sides by his opponents. An extreme long-shot (below) shows us the situation, with Bando in the distant center. Many shots break this space down into opposing forces, Bando versus his adversaries, and quite fast cutting shows the men on either side of him.

The stretch that interests me most begins with a shot of Bando looking left.

The director Futagawa Buntaro then breaks the confrontation into separate shots of the other swordsmen. Nothing unusual about that. But most directors would have handled the next few shots of the standoff this way:

Shot of Bando looking left.

Shot of a combatant looking right (implicitly, back at him).

Shot of Bando looking right.

Shot of a combatant looking left (implicitly, back at him).

This way we’d get a clear, simple sense of the fact that he’s surrounded on all sides. Instead, Futagawa follows the shot of Bando looking left with no fewer than twelve very close shots of fighters, all looking rightward. For example:

Then we get six shots of their arms outthrust, as here:

We then get a shot of several men looking straight to the camera, as if they represent the group directly in front of Bando, no longer at the left. Next there appear another ten shots of fighters looking leftward at Bando, all of them quite close to the camera. For example:

In both sets of shots, many images are composed to match each other graphically: the first group of faces tends to place each man on the left frame edge, while the second set puts most men at the far right. The first set of shots develops a pattern, moving from tight facial close-ups to shots of arms and swords thrusting toward Bando. The second set develops toward showing faces that are ever more cut off by the right frame edge.

Add in the fact that all these shots are cut very quickly, ranging from four frames down to one! This is extraordinarily rare in 1925 cinema. (I talk more about how to study such passages in an earlier blog.) Words can’t really convey the way these images clatter against one another. Their percussive speed makes them graspable only as a tense thrust in one direction countered by an equally tense one opposite. Faces pile frantically up against Bando first one one side, then the other. The sense of linear force is strengthened by the shift from the cluster of face shots to that of the arms, with the transition handled in a pair of weird jump cuts along different men’s arms.

The transition from the first shot above to the second creates the impression that the man has jabbed with his spear, while the cut from the second to the third shot eases us to the forearm shots shown earlier.

This bravura passage is triggered by the initial shot of Bando, haggard and shaky. Perhaps the cascade of shots is motivated as subjective, reflecting his exhaustion in the face of entrapment. Just as likely, I’d say, is the fact that Futagawa took a stereotyped situation, the hero surrounded by his adversaries, and looked for a way to make it fresh, to use energetic stylistic innovation to amplify the story point emotionally and perceptually.

Nothing in the sequence violates continuity editing’s basic principles. The shots keep screen direction constant and character position clear. Indeed, the director has understood spatial continuity very deeply: the men to the left of Bando are pushed far to the left side of the frame, the men to the right are squeezed rightward, so that Bando is always implicitly filling the area they’re recoiling from. But what American director would have risked such a bold piece of cutting?

Orochi, let’s remember, was released the same year as Strike and Potemkin. If this passage had been known to the earliest generation of film historians, Japan might well have been greeted as another birthplace of daringly dynamic montage. (2)

There are several other intriguing flourishes in the footage on display in Bantsuma, particularly a scene of Bando dying in a swirl of steam (this entry’s top image). But two points should be clear: this is innovative filmmaking of a high order, and it took place in a shamelessly commercial film industry. Mainstream filmmaking in Japan has been open to stylistic experiment to a degree rare in other popular cinemas. You can trace a line from the 1920s to the present, from the chambara directors through Ozu and Mizoguchi and Kinoshita and Suzuki Seijin right up to Kitano and Miike. Along a parallel path, Hong Kong action cinema pressed filmmakers toward creative renovation of film technique. (3) In this tradition, the action films of Bantsuma and his peers hold an honored place.

The lessons are familiar ones from this blog. Mass-market cinema harbors experimental impulses; creative directors working in well-known genres are often striving to push the limits. By attending to technique, we can discover a dazzling variety in areas of film history not usually considered “artistic.”

PS: Through Digital Meme, Matsuda has also made available a treasury of 55 animated films from the earliest years. The are at work on a DVD of early Mizoguchi films, including a fragment I’m keen to see from Tojin Okichi (Okichi, Mistress of a Foreigner, 1930).

(1) A large set of them has been available for some years on a DVD-ROM, also available from Digital Meme. For useful reviews, go to Midnight Eye and hors champ.

(2) ) I offer several other examples in the essays “Japanese Film Style, 1925-1945” and “A Cinema of Flourishes” in the forthcoming Poetics of Cinema.

(3) I make this argument in Planet Hong Kong and the essays “Aesthetics in Action” and “Richness through Imperfection” in Poetics of Cinema.

Simplicity, clarity, balance: A tribute to Rudolf Arnheim

DB here:

On Monday, at age 102, Rudolf Arnheim died. You can read his obituary here, and this is a lovely website devoted to his work. He was one of the most important theorists of the visual arts of the last century, and he had enormous impact on how people, including Kristin and me, think about film.

A good Gestalt

In parallel with E. H. Gombrich, who died in 2001, Arnheim brought modern psychological concepts into the study of visual art. His most famous work, Art and Visual Perception (1954, new version 1974) has the sort of magisterial presence that very few books in any era achieve. Arnheim delighted in the fact when, visiting a painter’s studio, he would find a spattered copy on the workbench. Of the revised edition, entirely rewritten, he noted:

All in all, I can only hope that the blue book with Arp’s black eye on the cover will continue to lie dog-eared, annotated, and stained with pigment and plaster on the tables and desks of those actively concerned with the theory and practice of the arts, and that even in its tidier garb it will continue to be admitted to the kind of shoptalk the visual arts need in order to do their silent work (new ed., x).

He aimed at theory that actively participates in the way artists do their job. The chapter titles of Art and Visual Perception deal with the nuts and bolts of picture-making: Balance, Shape, Form, Growth, Space, Light, Color, Movement, Dynamics, and Expression. No puns, slashes, dashes, or parentheses. What academic theorist today would so boldly announce their concern with the craft of creating images?

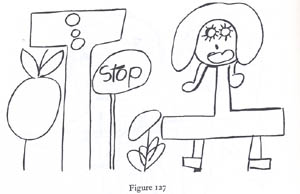

The book is subtitled, A Psychology of the Creative Eye, and the chapters’ subsection titles explain why. The hidden structure of a square . . . Vision as active exploration . . . Perceptual concepts . . . What good does overlapping do? . . . Why do children draw that way? . . . Gradients create depth . . . Visible motor forces . . . The priority of expression. Arnheim’s principal achievement in art theory was to integrate the Gestalt theory of perception with the traditional concerns of picture-making. He sought to show how perceptual laws discovered in the psychological laboratories of Berlin were intuitively applied by classic and modern artists.

As he put it, he was at the university at around age twenty:

My teachers Max Wertheimer and Wolfgang Köhler were laying the theoretical and practical foundations of gestalt theory at the Psychological Institute of the University of Berlin, and I found myself fastening on to what may be called a Kantian turn of the new doctrine, according to which even the most elementary processes of vision do not produce mechanical recordings of the outer world but organize the sensory raw material according to principles of simplicity, regularity, and balance, which govern the receptor mechanism.

This discovery of the gestalt school fitted the notion that the work of art, too, is not simply an imitation or selective duplication of reality but a translation of observed characteristics into the forms of a given medium (Film as Art, 3).

The Gestalters thought that these principles–figure/ground, completeness, good continuation, and the like–were fundamental to all human perception, across times and cultures. Art and Visual Perception makes a powerful case for this view. Today this position is so unfashionable that Arnheim’s calm confidence in it is quite stunning. For many scholars today, all that matters is what divides and differentiates us. But for eighty-plus years Arnheim emphasized ways in which we share a common experience of the world and of art.

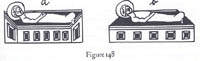

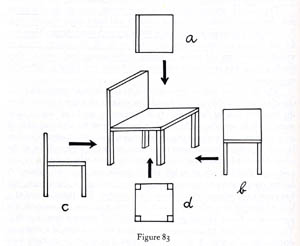

It’s often said that Arnheim favored modernist styles, like Cubism and expressionism, and that his emphasis on art as going beyond mere copying reflects modern artists’ will to distorted form. But he saw a deep continuity between classic art and modern art. Both traditions explored the perceptual force of form. Amazingly, he argues that the cockeyed creche in Fig. a conveys a stronger sense of three-dimensionality than the correct perspective presented in b. The “inverted” perspective encloses baby Jesus’ head fully, just a hollow cradle would.

It’s often said that Arnheim favored modernist styles, like Cubism and expressionism, and that his emphasis on art as going beyond mere copying reflects modern artists’ will to distorted form. But he saw a deep continuity between classic art and modern art. Both traditions explored the perceptual force of form. Amazingly, he argues that the cockeyed creche in Fig. a conveys a stronger sense of three-dimensionality than the correct perspective presented in b. The “inverted” perspective encloses baby Jesus’ head fully, just a hollow cradle would.

Arnheim saw the same form-giving activity at work in “primitive” art, the art of children, and even the art of the mentally ill. It turns out that the “universalism” of Gestalt theory underwrites diversity no less vigorously than the most ardent postmodernism.

Flexible striving

Arnheim made another contribution to our thinking about art, one that I think is rarely recognized. In a bold stroke, he extended the Gestalt conception of form beyond its concern with geometrical qualities and argued that form was inherently expressive. A triangle resting on its base wasn’t just balanced; it was weighty. We see the weeping willow as not just curved but sad; a skyscraper isn’t just tall, it’s aggressively thrusting upward. Every shape or movement we apprehend has a distinctive flavor and feeling. Indeed, he writes, “expression can be described as the primary content of vision”!

We have been trained to think of perception as the recording of shapes, distances, hues, motions. The awareness of these measurable characteristics is really a fairly late accomplishment of the human mind. Even in the Western man of the twentieth century it presupposes special conditions. It is the attitude of the scientist and the engineer or of the salesman who estimates the size of a customer’s waist, the shade of a lipstick, the weight of a suitcase. But if I sit in front of a fireplace and watch the flames, I do not normally register certain shades of red, various degrees of brightness, geometrically defined shapes moving at such and such a speed. I see the graceful play of aggressive tongues, flexible striving, lively color. The face of a person is more readily perceived and remembered as being alert, tense, concentrated rather than being triangularly shaped, having slanted eyebrows, straight lips, and so on (Art and Visual Perception, first ed., 430).

Arnheim found feeling in his forms.

Moving pictures

Arnheim wrote about many artforms, including mass media in his 1936 monograph on radio. His book on cinema, Film als Kunst (1932), was quickly translated into English as Film (1933). Always in search of greater clarity and point, Arnheim rewrote it in 1957. Oddly, he didn’t update it: You’ll search in vain for examples from the 1930s, 1940s, or 1950s. The touchstones remain Chaplin, Keaton, von Sternberg, and the Soviets. Arnheim held that cinema was essentially a pictorial art (see my earlier blog on this question) and that synchronized sound added very little; in fact, it might even inhibit visual experimentation. It was so easy to convey a story point with dialogue that lazy filmmakers would simply create photographed stage plays.

As a result, Arnheim is usually taken to be the summation of a certain strain of 1920s film theory. Like many earlier thinkers, Arnheim emphasized how film technique reshapes what is filmed. Close-ups, shot design, camera angles, and cutting make cinema no simple medium of reproduction. Film form transforms the world that is photographed. This position, commonplace today, was a real advance in the silent era and gave cinema artistic respectability, a subject that Arnheim reflected on thoughtfully in the 1933 edition of Film.

Again, Arnheim did more than synthesize current ideas. Theorists’ hunches that film stylized reality could now be grounded in Gestalt ideas about medium and form. In effect, Arnheim rewrote Film in the light of Art and Visual Perception, and the result was Film as Art. Here is the most famous passage:

Not until film began to become an art was the interest moved from mere subject matter to aspects of form. What had hitherto been merely the urge to record certain actual events, now became the aim to represent objects by special means exclusive to film. These means obtrude themselves, show themselves able to do more than simple reproduce the required object; they sharpen it, impose a style upon it, point out special features, make it vivid and decorative. Art begins where mechanical reproduction leaves off, where the conditions of reproduction serve in some way to mold the object (Film as Art, 57).

This, you might say, is Arnheim’s reply to Walter Benjamin’s theory of cinema as mechanical reproduction: no less than other artists, filmmakers use their medium, a photographic one, to create perceptually vivid effects akin to those in other arts.

Still, Arnheim held that film, like photography, has more limits than other arts. Tied to recording, film and photography can never achieve the range of expressive form we find in painting. I don’t believe this for a moment, but Arnheim clung to this opinion, I suspect, because of his deep love for creative freedom he found in other visual arts. And I sometimes think that for him, a painting harbored enough pushes, pulls, twists and torques. Movies just made explicit what was tactfully implied in still images.

Envoi

Kristin and I first saw Arnheim when we were graduate students at the University of Iowa, March 1972. He gave a lecture that stuck to his principles of 1933:

*Every art medium has a ceiling, beyond which it cannot effectively pass. The ceiling is somewhat low for the reproductive arts. Photography is more limited in what it can do than painting, and so is film.

*Films should be in black and white, the better to stylize reality. Are there no worthwhile color films? Pause. Red Desert, perhaps.

*Do you see many contemporary films? No.

Around 1980, I lined him up for a visiting lecture at UW. But he had to cancel; he had slipped on ice and broken his hip. He was then about seventy-five.

Later in the 1980s I visited Ann Arbor and had lunch with him. It was wonderful. By then I had read enough to ask him about Gombrich–an old friend and courtly opponent of his. (Read one of his reviews of Gombrich’s books to see what genuinely respectful disagreement looks like.) He saw pretty quickly that I was a Gombrichian and he gave a shrewd analysis of the dividing line: Gestalt psychology vs. ‘New Look’ cognitivism, illusions vs. expressive percepts, brain fields vs. schemas. He asked me to send me copies of my publications, which I did on and off during the decade. I never heard what he thought about my favorite fancy-pants sentence in Narration in the Fiction Film, when I contrasted J. J. Gibson’s theory of optical realism with Arnheim’s idea of expressiveness: “Gibson likes likeness, Arnheim loves liveliness.”

I thought of him often as I read more perceptual psychology. Gestalt work had once seemed to me a dead-end, but with David Marr’s theory of visual perception, a prototype of computational perceptual psychology, Gestaltism came roaring back. The “3D model representation” that Marr claimed operated in early vision uncannily echoes Arnheim’s discussion of our perception’s reliance on “characteristic aspects.” (Arnheim illustrates the idea with the various views of the chair, above. Which one is instantly recognizable as a chair?) And with contemporary interest in the relation between emotion and cognition, Arnheim’s theory of the expressive side of perception is creeping back too. Nothing worthwhile is forgotten, nothing goes away.

When we ran a book series at the University of Wisconsin Press, we were eager to publish an anthology of Arnheim’s film criticism, a collection originally published in German in 1977. Brenda Benthien, a close friend of Arnheim and his wife Mary, executed a lively translation and Arnheim supplied a touching introduction. A refugee of the Hitler years, an émigré across Europe and America, Arnheim summoned up the failure of the Weimar republic:

Even now I keep as a sort of talisman a bullet which in the days of the 1918 revolution, when I was fourteen, flew over the neighboring houses, bored a little hole through the windowpane, and fell inert on the carpet before my bed. Thus it began (Film Essays and Criticism, 3).

In the same introduction, Arnheim deplores the current state of cinema (“my basic objection to the talking film as a mongrel seems to me just as valid today as then”) and he warns against the cheapening of our vision:

Without the flourishing of visual expression no culture can function productively (5).

Aspiring film critics, and especially bloggers, should go back and read Arnheim on Keaton, Eisenstein, Gance, Pudovkin, Chaplin, von Sternberg, and other greats, as well as the essays “Style and monotony in film,” “Epic and dramatic film,” and especially “The Film Critic of Tomorrow.”

Scarcely a month goes by when I don’t have some idea that can be traced, however circuitously, to my reading of Arnheim. For instance, my blog on funny framings, posted a couple months ago, starts with his discussion of Chaplin’s The Immigrant. Arnheim’s theory of expression goes a long way toward explaining how composition can trigger laughter. I doubt that I’d be so alert to the possibilities of two-dimensional design in film shots if I hadn’t been tutored by Film as Art, Art and Visual Perception, The Power of the Center (1982, rev. 1988), his 1962 monograph on Picasso’s creative process in painting Guernica, and the essays in Toward a Psychology of Art (1966)–one of which is a skeptical review of Gombrich’s Art and Illusion. In preparing this entry, I found that my pleas that we probe the norms that guide filmmakers’ craft practices is just a clumsier restatement of this, which I discovered marked in Art and Visual Perception, the New Version:

Good art theory must smell of the studio, although its language should differ from the household talk of painters and sculptors (4).

Three years ago, after the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image convention in Grand Rapids, several of us from Madison–Ben Singer, Jen Chung, and Jonathan Frome–detoured back by way of Ann Arbor in order to call on Arnheim. He had just turned 100. He resided in an assisted-living facility, and his room was bright and clean, packed with books, remarkable drawings and paintings (Feininger, Köllwitz), a microfilm reader, and a worktable with a gigantic magnifying lens on an articulated arm. Conversation was difficult for him, but he seemed to understand everything we were saying. His smile was quick and his eyes were bright. When I showed him the first German edition of Film als Kunst I’d brought along, he turned it over in his hands as if he hadn’t seen one in years. He signed it, then shook his head apologetically at the shaky writing.

Now that Benjamin and Kracauer have become the prototypical Weimar intellectuals, it’s a pity that so many media students and professors are unaware of the importance of Arnheim’s work. His Leonardo-like interest in merging art and science is discouraged in a climate that posits the cultural construction of everything. He also writes with a grace and clarity that’s all too rare. In an unfashionable way, he exemplifies the passion, rigor, and dignity that interwar German intellectuals brought to the study of the arts. A lot of what he believed remains–what’s the word I want? Oh, yes–true.

Rudolf Arnheim, with Jonathan Frome, July 2004.

Line illustrations come from Art and Visual Perception.