Archive for the 'Film technique: Cinematography' Category

Walk the talk

The Magnificent Ambersons.

“It’s only history,” Jack Valenti is reported to have said when allowing scholars access to MPAA files. (1) After studying Hollywood for over thirty years, I should be used to the ways in which trade journalists (and some critics) forget or ignore historical precedents in moviemaking. But I still get bug-eyed when I encounter something like the Variety piece on TV director Tommy Schlamme (Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip).

The subhead tells us that this DGA nominee is known for his “hallway shots.” That gets my interest.

I lose interest fast. The writer tells us that Schlamme

developed the “walk and talk” on Sports Night and then mastered it on The West Wing.

The shot—which features two or more actors moving from one location to another on the set, often from one office to another via a hallway—has become a Schlamme signature.

The first sentence could be read as saying that Schlamme invented the walk-and-talk. Since I spent a little time studying this technique in The Way Hollywood Tells It, my inner film historian cries out, Aarrgh. Long before Sports Night (aired 1998-2000) and The West Wing (1999-2006), movies were developing such bravura shots.

The oblique view

In the prototypical walk-and-talk, two or more characters advance, and the camera tracks along, keeping them centered as they move through the environment. Such shots are quite uncommon in the silent cinema, but they emerge in 1930s films from many countries.

They were truly “signature shots” for Max Ophuls and the lesser-known Erik Charell. In Charell’s captivating The Congress Dances (1931) Lillian Harvey sings while a carriage takes her through an entire town and into the country, all in flowing tracking shots. Call it a ride-and-sing.

If that’s not as pure an instance as you’d like, we can find nice ones during a street scene of The Thin Man (1934). A more somber example occurs in Mizoguchi Kenji’s Story of the Last Chrysanthemums (1939), with the camera in a river bed angled upward at the couple it follows.

Usually such traveling shots from the 1930s and 1940s are shot obliquely to the actors. That is, the performers are seen in a ¾ view, and they walk along a diagonal path with respect to the frame edges; the camera moves on a similar trajectory. Sound cameras were mounted on dollies that usually ran on tracks. Framing the actors head-on raised problems with this gear. Performers couldn’t walk smoothly if they were stepping within rails, and there was a risk that the rails in the distance might appear in the frame. It was simpler to set the camera at an oblique angle so that actors could walk unimpeded and the tracks wouldn’t be seen. Directors continued to use this framing into the 1950s, as in Welles’ Othello (1952) and Fuller’s Forty Guns (1957). Both are unusually long takes; in the second, poor Gene Barry seems to be panting to keep up with the other men.

Back off

Today’s walk-and-talk is more likely to be a head-on framing, with the camera retreating from the actors. (More rarely, it dogs them from behind.) With a retreating Steadicam, you don’t have to worry about glimpsing the ground or floor behind the actors, in the distance, since there are no track rails to be exposed. Again, though, we have some precedents, most famously the splendid camera movements, evidently executed with a crane, in the ball sequences of The Magnificent Ambersons (1942), when George and Lucy stroll through the party.

When location shooting became more common in the 1940s and 1950s, cameras could be supported on more versatile dollies that didn’t require track rails, and these reverse-tracking shots become a bit more common. Kubrick, highly influenced by Welles and Ophuls, captured his officers striding through the trenches of Paths of Glory (1957). Vincent LoBrutto’s information-packed book (2) tells us that Kubrick’s dolly rolled backward on the planks that the actors walked on (authentic details, as boards were indeed used in the muddy trenches). Godard’s long traveling through the office lobby in Breathless (1960) was shot from a wheelchair.

Such head-on (and tails-on) shots can be found in several films well into the 1970s, as in Arthur Hiller’s The Hospital (1970). In fact, hospitals, police stations, and other sprawling institutional spaces seem to invite this approach.

By the 1980s, these shots proliferate in American films largely because the Steadicam makes them easy. One famous example is De Palma’s Bonfire of the Vanities (1990), which follows the drunken Peter Fallow through a hotel as he picks up and drops off many other characters.

Today such shots are very common in both high- and low-budget films. Schlamme’s “signature” device seems to be in pretty wide circulation. At best it’s a convention, at worst a cliché.

They’re called actors; let them perform action

I argue in The Way Hollywood Tells It that walk-and-talk is one of two principal staging techniques of contemporary Hollywood. The other, usually called stand-and-deliver, plants the characters facing one another and simply cuts from one to the other. The scene is built primarily out of singles (shots of only one actor) or over-the-shoulder framings. Here’s a typically static dialogue scene from The Matrix Revolutions (2003).

Both stand-and-deliver and walk-and-talk began in the studio era, decades ago, but then there were other options as well. Directors cultivated smooth, unobtrusive blocking tactics that moved characters in ways that reflected the developing scene. The actors had to perform with their whole bodies, and bits of business motivated them to circulate through the setting and turn toward or away from the camera. One example given earlier on this blog is from Mildred Pierce; here’s another, from the program picture Homicide (1949).

Detective Michael Landers has a hunch that the purported suicide of a former sailor is really murder. He has to persuade Captain Mooney to let him pursue some leads out of his jurisdiction. Today this might be played out in a stand-and-deliver session, with both men seated and shot/ reverse-shot cutting carrying the scene. But the director Felix Jacoves decides to let his actors earn their money through ensemble staging, not merely line readings. Here are just three shots from the middle of the scene that illustrate my point.

Landers stands at Mooney’s desk and gets a refusal. As he turns away to the left, Mooney walks to the rear files to put the papers away.

As they’re retreating to the opposite ends of the screen, Landers’ partner Boylan, who’s been offscreen for this phase of the scene, strides into the center and pauses at the door. The result of this choreography is both a balanced three-point composition and a chance to let us observe Boylan’s skeptical reaction to Landers’ next plea.

The camera tracks in as Landers approaches Mooney. Boylan shifts closer as well. What seems somewhat stagy as we analyze it doesn’t look obtrusive on the screen, because we’re following Landers’ arguments and watching the older men’s reactions. The closer framing and the position of the men, now face to face rather than separated by a desk, raises the dramatic pressure. As Landers pauses, Mooney folds his arms—a simple piece of body language that lets us know he’s still resisting.

Now a cut to Mooney, in an OTS framing, stresses his continued resistance as he tells Landers off, and a reverse shot gives Landers’ angry reaction.

Interrupting the sustained take, the shot/ reverse shot cuts have gained more emphasis than if they were part of a string of OTS shots. Jacoves has saved his cuts and closer views for a moment that raises the stakes visually as well as dramatically.

I’m not claiming that this is a brilliant stretch of cinema. (But you have to like a plot in which the hero defeats the killer by denying him access to insulin.) It’s just that the sequence activates, in a way that directors once took for granted, aspects of film art that we don’t find too often nowadays. Once you didn’t have to choose between Steadicam logistics and static dialogue; there is a very wide middle ground if you’re willing to move actors around the set and give them some body language and prop work. No need for a walk-and-talk here.

Schema and revision

The Variety article explains that Schlamme utilizes his long walk-and-talks to save time and money. But directors in the studio era shot their fully elaborated scenes like that in Homicide to be economical as well. If actors know their lines and hit their marks, playing out pages of dialogue in a few sustained setups can be very efficient; the Homicide full shot consumes 45 seconds. I’d argue that most contemporary directors have never learned to stage scenes this way. It’s a lost skill set. I make the case in more detail in Figures Traced in Light and The Way Hollywood Tells It.

To some extent, however, another skill set has emerged. Some walk-and-talks in The West Wing and other programs have an extra feature that the Variety writer and I haven’t mentioned. Often character A and B are walking toward us down the corridor, then B drifts off and C catches up with A. A and C walk for a while, then A peels off and C picks up somebody else, and so on. This approach is suited to multiple-protagonist dramas. You can show the plotlines crossing and separating.

I’m no TV historian, but I think that this technique showed up on St. Elsewhere (1982-1988), and it’s definitely on display in ER (1994-). Hospitals again. I think we also find this mingling/ separating choreography in contemporary film, but I can’t recall many examples in earlier eras. You could argue that one of the shots in the Ambersons’ ballroom does this, though I don’t think it’s a pure instance. (The principle of overlapping character actions is at work in many Renoir films, most famously in the final party melee in Rules of the Game, but Renoir doesn’t employ what we’re calling a walk-and-talk.) Did movies pick up this intertwined walk-and-talk from TV or vice-versa? I don’t know. If you do, drop me a line!

In On the History of Film Style and Figures Traced in Light, I argue that stylistic change in filmmaking often follows a logic of what art historian E. H. Gombrich calls schema and revision. (3) A pattern or practice becomes standardized, but then creators extend it to new situations or find new possibilities in it, and they modify it.

Camera movements have long been used to link characters. For instance, when Nick Charles circulates drinks in The Thin Man, Van Dyke tracks leftward to follow him from guest to guest.

So maybe in the 1980s and 1990s, when ensemble stories had to balance attention among several major characters, directors blended the multiple-interaction aspect of lateral camera movements with the schema of the advancing walk-and-talk. The result makes characters move in and out of each others’ orbits along a single trajectory. Whoever came up with this device, I’d speculate that it arose from the realization that the backing-up walk-and-talk could be repurposed for dramas following the fates of several protagonists.

It’s only history, but it matters if we want to understand stylistic continuity and change.

(1) Thanks to Richard Maltby for passing this along.

(2) Vincent LoBrutto, Stanley Kubrick: A Biography (New York: Fine, 1997), 141-142.

(3) E. H. Gombrich, Art and Illusion: A Study in the Psychology of Pictorial Representation (Princeton, N. J. Princeton University Press, 1960), especially Chapter III.

Shot-consciousness

Most professional critics seem uninterested in the film shot as a shot. They might notice when the images call flagrant attention to themselves, as in Zhang Yimou’s recent films, or in those protracted walk-and-talk Steadicam takes. On the whole, though, reviewers prefer to talk about plot and acting.

Granted, it’s hard to be aware of shots, especially if you get engrossed in the story. But if we want to be fully alert to how movies work on us, we should keep our eyes open. Back in 1968, I read The Moving Image by Robert Gessner, one of the first teachers of cinema studies in the US. There Gessner offered a sturdy piece of advice: Be shot-conscious.

About twenty years later, trying to be shot-conscious and all, I started to notice a certain type of image becoming more common, especially in European and Asian films. Then it started to appear in US films as well, especially indie items. Now it’s very common everywhere, though it’s still not the predominant sort of shot.

Here’s a fairly early example, from R. W. Fassbinder’s Katzelmacher (1969).

How to characterize it? The camera stands perpendicular to a rear surface, usually a wall. The characters are strung across the frame like clothes on a line. Sometimes they’re facing us, so the image looks like people in a police lineup. Sometimes the figures are in profile, usually for the sake of conversation, but just as often they talk while facing front.

Sometimes the shots are taken from fairly close, at other times the characters are dwarfed by the surroundings. In either case, this sort of framing avoids lining them up along receding diagonals. When there is a vanishing point, it tends to be in the center. If the characters are set up in depth, they tend to occupy parallel rows.

Linda Linda Linda (2005)

No one to my knowledge had noticed this sort of shot, let alone named it. I started to call it mug-shot framing, but I found that art historian Heinrich Wölfflin had called it planar or planimetric composition. I went with “planimetric” because that term suggests the rectangular geometry so often seen in these shots.

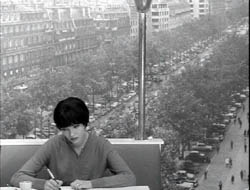

What’s striking is that such imagery is quite rare before, say, 1960. We can find some examples, principally in silent comedy and especially the films of Buster Keaton (himself a pretty geometrical director). But in the 1960s, we find Antonioni and Godard using planimetric shots fairly often.

Vivre sa vie (1962)

This image design became more popular from the 1970s onward. Why? In On the History of Film Style and Figures Traced in Light, I tried to trace out some sources and functions of it. Briefly, I think that the planimetric shot emerged from filmmakers’ growing reliance on long lenses, which tend to create a flatter-looking, more cardboardy space than wide-angle lenses do. A telephoto shot makes an image seem less voluminous. It seems to be made of slices of space lined up one behind another.

Filmmakers began using long lenses for many purposes, often because of the demands of filming on location. And some directors realized that long-lens optics offered fresh resources for staging and composition.

For instance, the planimetric scheme is well-suited to a “painterly” or strongly pictorial approach to cinema. In Figures, I discuss two directors who made planimetric shots central to their style. Hou Hsiao-hsien saw very deeply into the possibilities of these shots; I think he learned it from his early skill at shooting on the street with long lenses. You can find more about that here. By contrast, Angelopoulos used the planimetric image in conjunction with architecture and landscape to create a sort of de-dramatized spectacle, a spare grandeur reminiscent of icon painting.

The Suspended Step of the Stork (1991)

The functions of the planimetric image can vary a lot. Often it’s used to suggest stasis and passivity, as in the Katzelmacher instance. Kitano Takeshi picks up on this sense of torpor in certain shots of Sonatine, which suggests that being a gangster means having a lot of time to kill just hanging out.

Kitano’s use of the image also suggests a kind of childish simplicity or naïve cinema. Unlike Hou and Angelopoulos, Kitano uses the planimetric schema as if it were just the most basic way to film anything. Line up your characters and shoot ’em, as if they were figures in South Park or Cathy.

Kitano has compared himself to the kamishibai man, the street performer who narrates stories for children by flipping through illustrated cards, and Kitano’s paintings are more sophisticated, often planimetric versions of those drawings.

The planimetric schema can suggest something more oppressive too. That’s one purpose, I think, of certain shots in Terence Davies’ remarkable Distant Voices, Still Lives. The film’s stylistic system is quite rigorous in its use of straight-on compositions, and it’s worth more attention than I can give it here. For now I’ll just mention that the first part presents tableaux of unhappiness that suggest bleak family portraits.

Here and more generally, the planimetric image often carries the connotations of a posed photograph. Possibly the dry, rectilinear imagery of Walker Evans and the wide-eyed attitudes of Diane Arbus’s portraits have contributed to the sense of stiff ceremony such shots sometimes have.

Walker Evans, Roadside Stand Near Birmingham (1936)

Asian filmmakers combined the planimetric image with very long takes. In Kore-eda Hirokazu’s Maborosi, Yumiko’s husband comes home drunk, a slip from his usual reliable habits. She has just been remembering her previous husband, dead in a bike accident. The rocklike stability of the shot, aided by the grid backing the characters, throws every gesture into relief, particularly when Yumiko’s face lifts slightly into and out of shadow in the course of the action.

In the 1990s US indie filmmakers adapted this staging strategy. In Safe, Todd Haynes uses it to suggest the hard-edged sterility of the wife’s suburban life, which surrounds her with cubical furniture.

Wes Anderson used the image schema occasionally in Bottle Rocket but came to rely on it more and more. (He tended to use wide-angle rather than longer lenses, though; note the bulging effect in the Life Aquatic shot below.)

For Anderson, as for Keaton and Kitano, the static, geometrical frame can evoke a deadpan comic quality. This comes out as well in Jared Hess’s Napoleon Dynamite.

Initially, this scheme also helped filmmakers distinguish their work from Hollywood. Mainstream American films tend to film players in 3/4 views, except for certain situations, such as a theatrical performance or a scene showing a mammoth image display.

V for Vendetta (2005)

Some American directors seem to have used the planimetric shot decoratively, as a nifty one-off touch, as here in Kiss Kiss Bang Bang.

Many overseas directors who rely on this schema adjust their cutting accordingly. In Figures I called it compass-point editing. The usual tactic is to follow one planimetric shot with a reverse shot that’s also planimetric. In the first four shots of Kitano’s A Scene at the Sea, the camera angle switches either 180 degrees or zero degrees.

When I asked Kitano why he cut this way, he gestured toward me, then at himself. “When we are speaking, this is the way we look toward each other. It’s the most natural way to show a conversation.” Apparently this is why over-the-shoulder shots are pretty rare in Kitano’s films.

Planimetric shot/ reverse shot is seldom used in Hollywood films, and it seems to be reserved for certain confrontational situations, or institutional scenes (e.g., doctor/ patient conversations). It can sometimes suggest an unnerving or unnatural encounter, as in I, Robot. The detective Spooner is calling on his old friend Dr. Lanning, and their dialogue is shot in to-camera medium-shots.

At the climax of the conversation, the camera takes up a 3/4 position and arcs around Lanning, revealing him to be only a hologram, presenting his dying message to Spooner. The planimetric image is motivated as suitable for a flat, virtual presence.

Proyas has cleverly prepared us for this subterfuge by ending the previous scene with an unremarkable planimetric framing on Spooner as elevator doors close on him.

This shot leads directly to the initial shot of Dr. Lanning above, apparently addressing us, in a sort of shot/ reverse shot cut across two scenes.

As we might expect, Godard, who helped disseminate the schema, is all up for upsetting it, in Vivre sa vie and Made in USA. The first shot below teases us to read the flat background as a high-angle vista; the second carries the idea of a conversation in a planimetric frame to a beautiful absurdity.

My quick survey doesn’t exhaust the various forms and uses of this strategy. I just wanted to show how shot-consciousness can lead us to notice when filmmakers take up new pictorial tools and modify them for particular purposes.

Can they make ’em like they used to? continued

DB here:

In the wake of discussions of The Good German, on this site and elsewhere, the idea of a retro-looking movie has surfaced again. American Cinematographer‘s coverage of Casino Royale is very intriguing.

Phil Méheux, the cinematographer, decided that the opening sequence, a black-and-white passage showing Bond earning his 00 status, would pay homage to 1960s Techniscope. Techniscope was an optical process that produced 2.35:1 images without anamorphic lenses. It allowed great depth of field because it could take advantage of the wide-angle lenses available for non-anamorphic cinematography. The most familiar Techniscope images are probably those in Sergio Leone’s westerns.

For a Few Dollars More.

For a Few Dollars More.

Mehaux explains what he wanted for Casino Royale:

With Techniscope, the increased depth of field meant they were able to put things like lampshades and telephone boxes in the foreground, and they didn’t appear amoebic–you could actually see depth in them. In The Ipcress File, there’s a shot where a table lamp is huge in the frame and a man’s face is in the top right-hand corner. I really like that look. Part of the dialogue in our opening sequence was done with very carefully controlled shots that have huge things in the foreground and faces pushed to the corners of the frame. Little things like that echo the Cold War period of spy films.

But, but….

1. In the print of Casino Royale I saw in my local, the opening office scene didn’t really exploit sharp-focus foregrounds. There weren’t that many objects in the foreground, and they weren’t in discernible focus. Of course the cutting was so rapid that it was hard to concentrate on foreground/ background relations.

2. It’s fall of 1965, in Albany, New York. A film geek literally fresh off the farm is in his freshman year of college and goes to every movie in town. He sees The Ipcress File not once but three times. He’s fascinated by its flamboyant technique. He’s just seen Citizen Kane, so he’s impressed by deep staging and big foregrounds in this unheralded spy pic.

There’s even wilder stuff: a murder victim seen through a hanging lamp, for example.

The Geek reads up on long lenses, wide-angle lenses, and so on. Knowing nothing about Techniscope, he wonders how these extravagant shots got made. Just as important, why are they here (apart from looking cool)?

(Spoilers coming up. Skip to 3 if want to retain your innocence.)

After a couple viewings, the Geek begins to get a hunch about what those lampshades are doing there. Throughout the movie, actors are shot in juxtaposition to looming shapes–doors, lecterns, tabletops–which mask large stretches of the set.

And sometimes those blocking objects are lampshades.

At a climactic moment, our hero escapes from torture and calls his superior officer, who’s framed in the usual off-center way, with a lampshade dominating the shot. It works as a sheer (and pretty) block of solid color.

Turns out, however, that this time the shade actually conceals something important. The officer withdraws behind the shade and out pops a guest sitting alongside him.

The guest is the arch-villain. Now we know the officer is a traitor.

The Geek dimly realizes three things.

*A movie sets up visual “rules” it will follow or violate. (Later the Geek will call these intrinsic norms.)

*Visual motifs build up across a film, sometimes asking the viewer to notice them.

*A motif can seem gratuitous but that very gratuitousness can be exploited for storytelling purposes. When we see the red lampshade, we assume that it’s another decorative flourish, not a way of hiding information. Earlier sequences suggest that the device is a mannered tic but at the climax it helps spring a surprise. Motifs, the Geek would realize eventually, can fulfill narrational functions–that is, motifs can shape the ongoing flow of story information.

3. Sidney J. Furie was considered a showoffish filmmaker. Michael Caine said he belonged to the look-Ma-I’m-directing school. Certainly the outrageous compositions involving Marlon Brando’s sombrero in The Appaloosa back up that charge.

But like Richard Lester, Ken Russell, and other fancy-pants pictorialists, Furie can at least get us to notice technique. Not bad to cut your cinephile teeth on. Or at least so the Geek thinks, forty years afterward.

4. The AC article also talks about the problem of making poker games interesting. Hong Kong filmmakers figured this out long ago. Martin Campbell, director of the new 007 adventure, should study the crisp card sequences in Wong Jing’s God of Gamblers series. Filmed on a minuscule budget, they put the strained and blandly shot poker scenes of Casino Royale to shame. Incidentally, Wong’s use of diopters yields the sort of nifty depth that Meheux liked in Ipcress.

God of Gamblers.

God of Gamblers.

PS: Casino Royale didn’t learn the lessons of the 1960s well enough, in my view. After the sparkling opening credits, it was all downhill. The usual problems: overcut scenes, overcloseupped acting, incoherent chases and fights, uninspired dialogue you recite just before the actor says the line. One landing-strip truck fracas amalgamates Road Warrior, Raiders of the Lost Ark, and Die Hard 2. The makers have indeed updated the Bond franchise. After a series of lame 1970s-looking movies, the franchise has given us a lame contemporary-looking movie.

Granted, I never cared much for the Bond pictures. The Geek liked From Russia and Goldfinger, and Diamonds Are Forever is enjoyable in its wacko way. But for Machiavellian intrigue, Fritz Lang’s Spies remains the gold standard. No one can make ’em like he used to.

Spies

Spies

Cutting remarks: On THE GOOD GERMAN, classical style, and the Police Tactical Unit

DB herer:

For about ten days Kristin and I are off the grid, unable to check email, let alone blog.

In the meantime we’ll backlog some blogs (backblogs) to be posted at intervals. When we get back, we’ll probably divulge where we went.

This is a followup to my entry on The Good German of some days back. I want to talk a bit about editing technique in classical and contemporary film.

Recall that Dave Kehr’s fine reportage on Soderbergh’s Good German appeared in the New York Times. The film is set in postwar Berlin during the late 1940s, and Soderbergh is trying to film it with the production procedures of the time. He’s using boom microphones and incandescent lights, and he’s asking actors to deliver the lines in the forthright manner characteristic of classic studio acting. He’s using prime lenses of fixed focal length (as opposed to today’s zoom lenses with minutely adjustable focal length). Those prime lenses will often be wide-angle ones (e.g., 32mm), the sort that Soderbergh discovered that Michael Curtiz employed at Warners.

Soderbergh will also avoid multiple-camera shooting, which is common for most scenes nowadays; he will shoot single-camera. This has fascinating implications for staging and editing choices. Dave Kehr explains:

If there is a single word that sums up the difference between filmmaking at the middle of the 20th century and the filmmaking of today, it is “coverage.” Derived from television, it refers to the increasingly common practice of using multiple cameras for a scene (just as television would cover a football game) and having the actors run through a complete sequence in a few different registers. The lighting tends to be bright and diffused, without shadows, which makes it easier for the different cameras to capture matching images.

The advantage for directors is that they no longer need to make hard and fast decisions about where the camera will go for a particular scene or how the performances will be pitched. The idea is to pump as much coverage as possible into the editing room, where the final decisions about what goes where will be made.

The danger for a director is that with so much material available, the original vision may be drowned or never really defined; and the sheer amount of exposed film makes it possible for executives to step in (after the director has completed his union-mandated first cut) and rearrange the material to follow the latest market-research reports.

During the studio era it was more typical for directors to arrive on the set, block out their shots and light them with the use of stand-ins; the actors were then summoned from their dressing rooms and, after a brief rehearsal, they would film the lines needed in the individual shot. The crew would then break down the camera and move it to the next setup, as determined by the director.

“That kind of staging is a lost art,” Mr. Soderbergh said, “which is too bad. The reason they no longer work that way is because it means making choices, real choices, and sticking to them. It means shooting things in a way that basically only cut together in one order. That’s not what people do now. They want all the options they can get in the editing room.”

While the editing process now routinely takes months, “I had a pretty polished cut of ‘The Good German’ two days after we wrapped,” Mr. Soderbergh said. “It was shot to go together very, very specifically.”

Let’s start with the concept of coverage.

Shooting to Protect

Consider a traditional conversation scene.

In the classical Hollywood style, most such scenes were shot with a single camera. (In the silent years, big films would be shot with a second camera to provide a negative for foreign markets. This means that in some films, the overseas versions were slightly different, shot for shot, from their US counterparts.)

Your conversation scene will be edited. So how do you film it? Working with only one camera, directors developed procedures for “covering” a scene.

Here’s the default. The entire scene would be played out in a single, distant take, usually called the master shot (sometimes “master scene”–for a long time, filmmakers confusingly called shots “scenes”). The master shot provided an uninterrupted record of the whole scene, and thus served as a reference point for overall set geography, where actors were standing, and so on.

Once the master shot was finished, the filmmakers went on to break the scene down into closer positions. That meant repeating portions of the scene already played in the master. They shot the medium two-shots of the actors talking, the shots of each actor taken from over the shoulder of the other actor, the singles of each player–which might be medium-shots, medium close-ups, or close-ups.

(Sometimes the filmmakers also shot inserts, the detail shots of objects or printed matter that would be inserted into the action, but usually they were filmed another time, or by an entirely different crew under the supervision of an assistant or second-unit director. Often the hands we see in an insert close-up aren’t those of the actor.)

For each different camera position, the actor would have to repeat the relevant bit of dialogue, gesture, or whatever that had already been played out in the master. Must have gotten boring, no?

The question arises: How much coverage do you shoot? Do you have to film from all those angles, and do you have to repeat everything to the max?

One answer says yes. Overshoot. This is the shoot and protect option. Film lots more footage than you can possibly ever use. Film is cheap, and you want lots of options in the editing room. Since in the studio system, directors rarely supervised the editing of their films, the editor worked with the producer, and the producer wanted to readjust the film in the cutting phase–inserting a close-up of the star, tightening the pace, and so on.

Shoot and protect is an insurance policy, and producers still insist on it. In The Way Hollywood Tells It, I quote Swedish cinematographer Sven Nykvist’s remark that American directors shot a lot more coverage than European ones. “I believe that comes from the fact that producers usually have the final cut and they want to have all the material they can get.” In the studio era, producers might want changes and demand reshoots of portions of scenes so the sequence would cut together better.

During the studio era, the most famous director who relied on overshooting is George Stevens. In an interview with Kristin and me, William Hornbeck talked about how Stevens was maniacal about reshooting the scene from every angle he could think of. Then he would run the footage over and over, trying to decide what takes to use. One result of this is a fairly choppy style. The barroom fight in Shane is almost wholly created in the editing room, and some of the cuts are downright clumsy.

Or take the barbecue scene of Giant, where the cuts struggle to extract a throughline of action. Elizabeth Taylor stands on the edge of the crowd, and abruptly Stevens dissolves to an extreme long shot of the festivities.

So is the scene ending, as such a reestablishing shot might suggest? No, because we dissolve again to her, now walking to the tree in the foreground, captured in a high angle from a crane.

Most directors would have moved Elizabeth Taylor away from the crowd in a single tracking shot, letting the camera follow her approach to the tree. Stevens apparently hadn’t planned or filmed such a shot, so he had to use two dissolves, although there doesn’t seem to be a time lapse. Once Liz gets to the tree, the high angle obscures her face and gesture, so a cut tries to clarify:

Stevens cuts to a head-on shot of her starting to swing around the tree. But she doesn’t get a chance to complete this gesture because the tree blocks her face and arms. So Stevens cuts away to James Dean, already walking leftward to the car–another interrupted action.

Dean settles down to watch the barbecue from a distance, but instead of getting anything resembling a point-of-view shot, we go back to the uninformative high angle, in which a cowpoke offers Taylor a drink.

We can’t really see the first man’s gesture, or her reaction, so the dialogue has to carry the whole scene. And this action is interrupted again by another man proposing a toast to the couple. The high angle adds nothing to the scene. Didn’t Stevens film this bit of action from a more straightforward setup? If not, maybe he didn’t protect himself. Whatever happened, this passage seems to be very awkward filmmaking.

Granted, the cuts between Taylor and Dean do parallel them as outsiders and prefigure their alliance later in the film. But the same points could be made with smoother cuts and greater integrity of gesture. The scene’s fragmentation prefigures today’s interruptive editing.

Someone might argue that the jumpy cutting conveys something expressive about the scene (maybe Taylor’s anxiety about making a mistake in front of her new husband’s friends). But this is an all-purpose alibi, which can be invoked to defend any case of poor craftsmanship. My shot’s out of focus because…um…the hero’s uncertain of his identity. Moreover, if we defend the cutting as projecting Taylor’s anxiety, we’re tacitly granting that the scene has failed to convey that through performance, staging, and other techniques.

Lest it seem I’m being too mean to Stevens, I’ll just point out that occasionally he took some chances, even using single-shot high-angle staging reminiscent of Mizoguchi. Here’s an example from A Place in the Sun.

Shooting Cut to Cut

“Shooting for protection” sounds a bit defensive and wussy, like you’re afraid to make a choice. Suppose you try another tactic. Suppose you shoot only what you think you will finally cut together.

You might still shoot the master shot for insurance, but maybe not. On the whole, you’d shoot only the angles you’d decided on in advance, or perhaps you would add a few pieces for protection. Basically there would be only one way to cut the scene together. This was called filming “cut to cut” or “cutting in the camera.”

Hitchcock is the most famous exponent of this tactic, thanks largely to his claims that he preplanned everything that appeared on screen. After working out the script, shot lists, and storyboards, he knew exactly what he wanted, he said, and so the actual filming was a little tedious. I think he once remarked that he wished he could phone a film in. In truth, Sir Alfred exaggerated the precision of his planning. Bill Krohn’s excellent book Hitchcock at Work debunks “the myth of the storyboard” (which were often made after filming, to show reporters) and Krohn offers several examples of set improvisation, last-minute changes, tightening during editing, and so on (pp. 9-16). Nevertheless, on the whole Hitch probably shot significantly less coverage than most directors.

So too, evidently, did John Ford. Ford didn’t pre-plan his films to the minute degree Hitchcock claimed, but he achieved enough power in the system to avoid the shoot-and-protect method. According to editor Elmo Williams, whom I once asked about this, Ford had the reputation of giving his cutters almost no range of setups to choose from. If you give ’em a close-up, he supposedly said, they’ll use it. Ford apparently kept track of all the shots he wanted in his head, which may explain some of the mismatches that we find in his films. But it did mean that when the shooting was finished, he could hand the footage over to an editor and go out on his boat.

Another director who filmed coverage sparingly was W. S. Van Dyke, known as Wun-Shot Woody. You can read more about him here.

So there are degrees of coverage, from the maximal coverage of shoot-and-protect to the minimalism of cutting in the camera. Of course you can avoid coverage altogether by shooting your scene in a single take, from a single position (as Hou Hsiao-hsien often does) or with a moving camera. Producers hate this. Christine Vachon calls it “a ‘macho’ style that leaves no way of changing pacing or helping unsteady performances” (The Way Hollywood Tells It, 153). The director who doesn’t provide extensive coverage is a producer’s nightmare.

Camera A + Camera B + Camera C…+Camera N = ?

What about shooting the scene with more than one camera? Before the 1970s, multiple cameras were used chiefly for action sequences, and especially for things that couldn’t be repeated, like an explosion or cars hurtling off a cliff. Multiple cameras were also used for a brief period when sound first came in; watch nearly any film from 1929-1931 on Turner Classic Movies, and you’ll see scenes filmed much as TV sitcoms and soaps are filmed today, with several cameras. (For more on this, see The Classical Hollywood Cinema, Chapter 23.)

On the whole, though, multiple cameras were rarely used until some time in the early 1980s, when shooting schedules were accelerated. Faced with the need to turn out more footage quickly, directors began using “B” cameras to pick up alternate angles. Now a big picture may have “C” camera plus a Steadicam roaming around to grab details. One of my favorite quotes (in The Way, p. 154) is from John Mathieson, DP for Gladiator, who after explaining that by using seven cameras for some scenes, “I was thinking, ‘Someone has got to be getting something good.'” The old Hollywood directors, thinking through the scene shot by shot, knew when they were getting something good; now everybody just hopes.

In effect, as Dave Kehr’s article implies, multiple-camera shooting is today’s equivalent of classic coverage. Soderbergh is right to note that this practice postpones decisions until the editing stage. But it has other knock-on effects on the way the movie looks. I’ll consider just two, which I expand on in The Way.

1) Having reams of footage tends to speed up the cutting rate. Rather than sticking with a few angles, directors offered many choices tend to like a little bit of angle 1, the middle part of angle 2, another stretch of angle 3, and the last bit of angle 4. Four shots arise in the editing process, when maybe a single well-chosen one would do the job.

There are many sources of the fast cutting that rules contemporary cinema, but probably the practice of shooting with A, B, C, and N cameras is one.

2) Multiple camera shooting limits the freedom of camera position that single-camera shooting allows. Obviously, you can’t put Camera B in a position where it will be seen by camera A. In fact, you tend to keep all the cameras at a fair distance from the scene, using long lenses to enlarge the actors.

The implication is that the cameras really don’t work their way into the space as much as they do in single-camera shooting. You can’t put the camera between characters as easily, so Ozu’s characteristic frontal framings aren’t as feasible. Or, going back to Soderbergh’s beloved 1940s, take the variety of angles we find in the conversations between Spade and Gutman in The Maltese Falcon. These can’t easily be replicated with multi-cam staging.

Medium two-shots are also problematic with multiple cameras. (Hence perhaps all the singles and close-ups we get in contemporary films.) And all cinematographers grant that lighting an overall scene so that it looks right from several camera angles requires many compromises.

So I look forward to seeing how, in an age when single-camera coverage is rare, Soderbergh will handle these matters. Will The Good German‘s cutting rate be slower than is common nowadays? (The 1940s and early 1950s saw the widest disparity in average shot lengths in Hollywood’s history, from very short shots to ASLs over thirty seconds.) Will the camera penetrate the space in the manner of the ubiquitous setups of the studio years?

Finally, I’d just like to note that Soderbergh didn’t have to return to the 1940s for inspiration. Classic techniques of coverage, even cutting in the camera, are amply on display in other cinemas.

Mackendrick’s Axiom

Today’s choppy editing style is interruptive rather than integrative. A typical director today doesn’t let a shot ripen to full implication. The cut interrupts the shot rather than coming at the moment that will carry forward what’s been developing in the image.

The British director Alexander Mackendrick once suggested that at each moment the director must prepare the audience for what is going to happen next. If you’re really good, shot A prepares not only for B but for C and D as well. You can study this process in Lang, Ford, Hawks, and other classical directors, but it’s still visible today, I think, if we know where to look.

Yes, the answer is Asian cinema again. Hong Kong, no less.

Johnnie To Kei-fung began his career in television in the 1970s, made a feature in 1980, and returned to shooting TV series in the early 1980s. He shot single-camera cop shows, martial-arts shows, and other dramatic shows. No shot lists, no storyboards–no time! Given the brisk schedules of TV shooting, To mastered the ability to film one shot while thinking about the next three, the way a chess master conceives a string of moves. He makes the determining decisions about the sequence in the flow of production, then fine-tuning them in editing.

Johnnie To shifted to feature filmmaking in 1986, and he has turned out more than forty films since. Sometimes he finishes three films in a single year. His output includes many extraordinary achievements, such as Lifeline (1997), The Longest Nite (1998), Expect the Unexpected (1998), A Hero Never Dies (1998), The Mission (1999), Throw Down (2004) and several others. His two films about Triad life, Election 1 (2005) and Election 2 (2006) have received wide attention, as has his most recent release, Exiled. These last three have been picked up for US theatrical release.

His style can vary a lot from film to film, from the frenetic action of A Hero Never Dies to the hairtrigger poise of The Mission. But in each case you detect a director who makes his stylistic choices and sticks to them. He can structure a scene in his head and he can shoot the result efficiently. He is, we might say, today’s Woody Van Dyke. Except he’s quite a bit better.

Here’s a sequence that exemplifies Mackendrick’s axiom.

During the climactic gunfight of PTU (2003), a female police officer fires at a gunman. He fires back, and she drops her pistol as she dives back into her car. Then the cop Lo, the hapless slob we’ve been following, seeing the gunman about to fire, dashes out of the shot. This is followed by a shot of the gunman swiveling and firing.

The next shot is the crucial one. Through a rain-speckled car windshield we see Lo fleeing.

Why shoot from this fancy angle? It does two things at once. It tells us about the fleeing cop’s progress, continuing the action of the earlier shot of him, but it also puts us in the car, implying that the next phase of the action will take place here, rather than on the street. And so it does:

The wounded gunman staggers against the car, and again, instead of seeing his progress from the outside, we’re in the car. We don’t need to see his face, only the gun: director To films the danger. This shot expands on the previous one, keeping us in the front seat, and then gives us new information. The camera tilts diagonally to the policewoman crouching below the window.

The suspense is heightened when To cuts back to the pistol, bumping along the glass.

Will the gunman look inside the car? The movement of his arm is continued smoothly in a new angle:

….as he rushes off to the right in pursuit of Lo. Director To gives us both action and reaction in the same concise shot. The policewoman sobs in relief, and this sub-sequence ends with a pause on her.

The sequence has broader implications as well, since this officer has been suspecting all along that Lo has lost his pistol (which he has). Now she has lost hers. After the smoke has cleared, Lo strolls back to her, and the shot echoes the earlier shots taken through the windshield.

The irony dawns on her–in the heat of battle, it’s easy to lose your weapon–as she glances down at her discarded gun and retrieves it.

This sequence couldn’t have attained such precision if it were filmed with several cameras snatching shots, hoping to get something; nor with shoot-and-protect coverage. The passage is conceived cut to cut, in the director’s head. Each shot makes one or more points succinctly and leads us crisply to the next bit of action. When I asked Mr. To about the shot of Lo fleeing, seen through the windshield, he seemed surprised that I’d wonder. “Of course! You have to let people know they’ll see her in the car.”