Archive for the 'Film technique: Editing' Category

Sometimes a jump cut…

A Touch of Zen (King Hu, 1970).

DB here:

….really is a jump cut.

I had spent a day studying King Hu’s The Valiant Ones at an archive. That night over dinner, my friend asked me what was taking me so long. I answered, “I’m trying to figure out his secrets.” Her brow furrowed, but then she said, “I suppose that’s all right as long as you never tell anyone.”

Reader, I told. Eventually.

The puzzle for me was how King Hu gets the remarkable kinetic effects in his fight scenes. He starts with the conventions of the Chinese wuxia (“martial chivalry”) film. Fighting with or without weapons, the warriors have extraordinary powers of speed and strength. They can sometimes defy gravity with “weightless leaps” that carry them great distances.

Today, digital special effects permit quite dazzling images showing flying warriors in extended long shots, as in Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon and Hero. But Hong Kong directors of the 1960s and 1970s had much more meager special effects available.

The alternative was to present these feats through constructive editing. A character leaps in shot A, flies through the air in shot B, and lands in shot C. All much easier to film than a single, faked long shot. From the 1980s on, strong but thin wires would keep the fighters in the air for long shots. Many fine films were made using wirework, but for the most part King Hu couldn’t use it. About his only technological support was a variety of trampolines that could be cunningly hidden in a set.

King Hu’s solution to the problem of flying swordfighters involves a unique approach to film technique. In an article called “Richness through Imperfection: King Hu and the Glimpse,” I argued that he found a way to make his fighters’ prodigious moves register in a percussive but almost subliminal way. It’s not just that if you blink, you miss the action. (Though if you do, you will.) His goal isn’t just to use brief shots (some only three or four frames long) to arrest our attention. More important, King Hu evokes the quasi-supernatural power of his fighters by suggesting that they move too quickly and unpredictably for the camera to catch.

He accomplishes this by reshaping the constructive-editing scheme of launch/leap/landing. He trims each shot to a minimum, provides several intermediate flying shots (each also very short), and makes our eye work by shifting the center of interest from shot to shot. He provides eccentric angles, unexpected cuts, and startlingly empty frames. Characters run, spring up, and soar, but in a flurry of frames, or on the screen edge, or dodging in and out of sight–blocked by bits of the set, or just by a framing that doesn’t adjust quickly enough to their impulsive movements.

A good example is the moment in Dragon Gate Inn (1967) when the eunuch Tsao attacks the group defending the family of General Yu on the roadway. A low angle shows him launching his jump.

So far, so conventional. But instead of giving us a clear image of Tsao in flight mode, Hu gives us this:

Tsao slides down the left frame edge, vanishes for an instant, then bounces up, already somersaulting, on his way to strike his adversary Hsiao. The framing fails to keep up with him, implying that he’s just too elusive, while his wayward entries into the frame provide percussive accents.

King Hu liked to play with the leap phase of the ABC pattern, as here and in my knockout passage for the day, shown at the top of the entry. In the penultimate confrontation of A Touch of Zen, Commander Hsu attacks the serene Abbot Hui Yan. Hsu leaps a huge distance and comes down directly in front of the monk. But King Hu renders this miraculous feat in two nearly identical framings: one showing the launch, the other the landing. Seen from over the monk’s shoulder, Hsu has been endowed with blinding speed through a sheerly cinematic effect–a bold jump cut.

Please note: This isn’t a clumsy patch job in the particular print. The cut is in the negative, and it’s been in every print I’ve ever seen of Touch of Zen.

“Jump cut” is a term that’s used in different ways. Sometimes it refers to various kinds of mismatches that yield a jolting discontinuity. I’m using the term here to denote an effect that results from excising some frames from a continuous shot. The classic examples have always been the cuts in Godard’s Breathless. The Touch of Zen example is a little less pure because you can see that Shot 2 doesn’t strictly continue Shot 1’s camera setup. King Hu has moved the abbot’s head and shoulder a little further away from us. But the compositions are graphically very close, and the impression on screen is of a single camera take with some frames lopped out.

When we ask, Where did Hsu go from shot to shot?, the answer is: In the cut. Without the advantage of special effects, King Hu has given us a propulsive impression of speed and ferocity.

His secret? Merely a uniquely cinematic imagination.

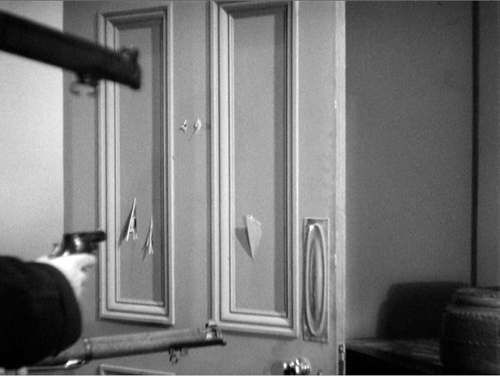

Some of our techie readers might be curious about the images here, photographed from a 35mm print. Perhaps they’ve noticed that Hu’s cutting has left its physical trace on the film strip.

In classic filmmaking practice, cuts were made with splices–physical joins between one piece of film and another. In film-based formats, splices were made with glue or transparent tape. (Today, of course, they’re largely made digitally and called “edits.”) Most filmmakers hid their splices, but there’s a robust tradition in avant-garde cinema of integrating splices into the image; you can see it, for example, in the work of Stan Brakhage and Paolo Gioli.

Splices are visible as horizontal flashes across the bottom of the screen. In 35mm filmmaking, the final printing phase usually masks those out. But, as Erik Gunneson reminds me, that’s harder when you’re shooting anamorphic scope. There the image is recorded full-frame on the film strip, so traces of the splice may remain visible, especially in older films.

When we look at the physical strip here,we can see that Hu’s negative cutter has simply spliced one shot to another with cement. The illustrations up top show the last frame of Shot A and the first frame of Shot B. You can see the neat splice, a horizontal line running along the bottom of the first frame and the top of the second. The same trace of a splice is visible in the cut involving Yang’s leap.

The odd thing to modern eyes is that there’s a bit of overlap, a thin slice that seems out of whack with both shots. In Shot A, the bottom edge of this thin strip cuts off the abbot’s head weirdly. Let me show you the first frame of the second shot again. Reading from top to bottom, you see a bit of the bottom of Shot A’s last frame, then the true frame line, then the weird little band. The bulk of the image is the frame that starts Shot B.

What’s that thin slice between the frame line and the yellow splice line? It’s the top bit of the next frame of the first shot as taken in camera. It shows the trees and the abbot’s head and ears as they appear at the top of Shot A’s composition. Instead of cutting exactly on the frame line of Shot A, the editor has overlapped a tad of the following frame in order to attach the two shots with cement. During a screening, the extra bit may be minimized or eliminated because the projector plate doesn’t show us the entirety of the image on the strip, but it is there.

Splices can be hidden through A/B rolling, which I believe is more common in 16mm than in 35mm production. I don’t believe that Chinese films of Hu’s day made use of this process, but I’d appreciate more information.

The essay on King Hu is in my Poetics of Cinema (Routledge, 2008), 413-430. For more on King Hu and his innovations, see Planet Hong Kong: Popular Cinema and the Art of Entertainment, available elsewhere on this site. Kristin and I discuss jump cuts and graphic matches in Chapter 6 of Film Art: An Introduction. See also the “Film Technique: Editing” category on the right of this page.

This blog entry follows from two others: “Sometimes a shot . . .” and “Sometimes two shots . . .”

I put up this post now because I’ll be giving a talk on Chinese martial arts cinema next Monday, 10 June at the Toronto International Film Festival Bell Lightbox, at 6:30. It’s a part of TIFF’s splendid summer-long celebration of Chinese cinema. On the day before, 9 June, there will be a free screening of Hou Hsiao-Hsien’s Dust in the Wind (1987) at 10:00 AM. After the show, there’ll be a panel featuring Bart Testa, Hou expert Jim Udden (who posted a blog entry with us on Hou’s new project), and me.

This entry is also to congratulate Peter Rist, tireless guardian of the Shaolin Temple, on his birthday.

A Touch of Zen.

Sir Alfred simply must have his set pieces: THE MAN WHO KNEW TOO MUCH (1934)

The Man Who Knew Too Much (1934).

DB here:

Hitchcock made six remarkable thrillers from 1934 through 1938, and I have long believed that the first one was the best. I think very well of Sabotage, and both The Lady Vanishes and The 39 Steps are strong contenders. But for me, The Man Who Knew Too Much has got damn near everything going for it.

I came to it a little late. It wasn’t the first Hitchcock I wrote about; that was Notorious, in a 1969 piece that nakedly reveals the limitations of a college senior’s knowledge. Nor was it the first Hitchcock I saw; that was Vertigo, when I was about ten. Inauspiciously for me, when Vertigo was revived for national television broadcast in 1972, I was flying to a job interview in Madison, Wisconsin.

I got that job, though, and soon The Man Who Knew Too Much became very important for me. Seeing it at a film society screening, I was bowled over. Then I discovered that it was available for purchase in a cheap 16mm print. I bought a print and began teaching the film as a model of narrative construction. It worked its way into the first edition of Film Art, in 1979 and hung around there for several editions.

That sample analysis has been available as a pdf on our site, but check it out at the Criterion site, where it’s enhanced with nice frame enlargements and a major extract. The essay makes my case for the movie as an extremely well-constructed piece in the classical storytelling tradition.

So I was the ideal consumer for a spruced-up DVD/ Blu-ray release, and as usual Criterion doesn’t disappoint. It’s a handsome version, with some fine supplements. We get two rare interviews with Sir Alfred from CBS’s arts program Camera Three (featuring Pia Lindstrom and William K. Everson) and a perceptive discussion with Guillermo del Toro, who makes a vigorous case for the film. So does Philip Kemp in his commentary, which is strong on production background. Kemp offers valuable information on script versions and on Hitchcock’s niche in the English industry. The accompanying booklet includes a lively appreciation by The Self-Styled Siren, aka Farran Smith Nehme.

So I was the ideal consumer for a spruced-up DVD/ Blu-ray release, and as usual Criterion doesn’t disappoint. It’s a handsome version, with some fine supplements. We get two rare interviews with Sir Alfred from CBS’s arts program Camera Three (featuring Pia Lindstrom and William K. Everson) and a perceptive discussion with Guillermo del Toro, who makes a vigorous case for the film. So does Philip Kemp in his commentary, which is strong on production background. Kemp offers valuable information on script versions and on Hitchcock’s niche in the English industry. The accompanying booklet includes a lively appreciation by The Self-Styled Siren, aka Farran Smith Nehme.

Interest in Hitchcock seems to be the one constant in the whirligig of tastes in film culture. He is a mainstay of home video and cable television; apparently the films can be re-released in perpetuity. Professors love to teach his films. The techniques are obvious and vivid, and the films offer a manageable complexity that encourages interpretation. Class, gender, power, the law—whatever your favorite themes, they’re all on the surface, yet enticingly ambivalent. Not to mention how much fun these movies are to watch. I’ve always enjoyed introducing “lesser Hitchcock” like Stage Fright and Dial M for Murder and then watching the audience fall under their spell.

Critics navigate by Hitchcock as a fixed pole star. Reviewers compare every new thriller to the classics of The Master of Suspense. Just look at what people write about Soderbergh’s Side Effects. And for those who promoted the auteur approach to Hollywood cinema, Hitchcock was a beachhead. Who could doubt that this man turned out personal projects within the impersonal machine known as Hollywood? And if he could do it, why not Ford, Hawks, Sternberg, Ray, and all the rest? Hitchcock nudged skeptics down the slippery slope toward auteurism.

Even if Hitchcock isn’t to your taste, you can’t avoid his influence. That became obvious around the 1970s, when directors began borrowing from him more or less overtly: Spielberg’s Vertigo track-and-zoom in Jaws (now itself a convention), De Palma’s homages/pastiches, Polanski’s use of point-of-view in Repulsion and Rosemary’s Baby, the endless Psycho sequels and the van Sant remake, and the rest. But Hitch was no less influential in his own day; I’d argue that filmmakers of the 1940s had to raise their game if they wanted to meet the challenge of Rebecca, Foreign Correspondent, Suspicion, Shadow of a Doubt, Spellbound, and Notorious. Billy Wilder told a reporter that Double Indemnity was his effort to “out-Hitch Hitch.”

What was so special? Obviously, the throwaway humor—sometimes airy, sometimes slapstick, sometimes sardonic. And obviously a gift for switching situations around, playing them against cliché, setting us up for a jolt. But I think there’s something else afoot. Part of the Master’s repute rests on virtuosity of film technique. Hitchcock makes movie movies, even when, like Rope or Dial M, they seem “theatrical.” And this movieness is best seen, I think, by considering a term that always comes up with Lord Alfred: the set piece.

Maintaining a tradition

Hitchcock held onto the flamboyant expressive devices of silent and early sound cinema far longer than any other director. For decades he kept alive techniques that many directors thought were old hat: abrupt cuts to details of gestures and objects; blurry point-of-view images to suggest distraught or befuddled states of mind (as above); very brief insert shots to accentuate violence. Compare Battleship Potemkin with Foreign Correspondent’s assassination scene.

Hitchcock built entire films around classic silent techniques. The Kuleshov effect governs Rear Window; the German “entfesselte” or “unchained” camera dominates Rope and Under Capricorn. Rope and Dial M revive the aesthetics of the German kammerspielfilm, or “chamber play.” The Germanic look was alive and well in the spiderweb shadow-work of Suspicion, while both French Impressionism and German Expressionism inform the dream sequences of Spellbound and Vertigo. He also preserved the “creative use of sound” that was the hallmark of directors like Clair and Milestone. While others had pretty much given up the expressionistic use of music and effects, Hitchcock was always ready to draw on them. The hallucinatory Merry Widow Waltz haunts Shadow of a Doubt, while Hitchcock’s penchant for giving us two pieces of information simultaneously, one in the image and another on the soundtrack, let him design scenes visually and push a lot of dialogue offscreen.

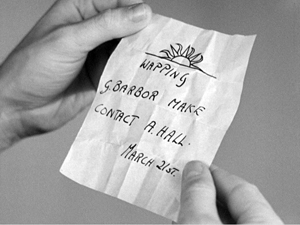

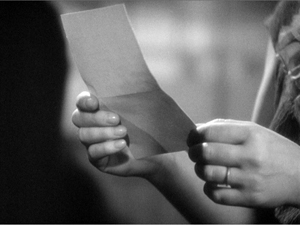

This flexibility of technique modulates from scene to scene. In The Man Who Knew Too Much, note-reading is presented in three ways, in rapid succession. First, Bob finds Louis’ note in the hairbrush.

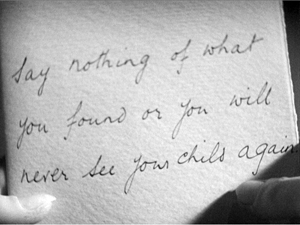

Soon Bob gets a message from the front desk. What does it say? Hitchcock hides that by, for once, not supplying subjective point of view.

Only when the note is passed to Jill do we get to see it, but with a twist. Nobody but Hitchcock would add an extra shot that cuts to the note in her hand without revealing what it says.

That extra shot is what Eisenstein called a primer; as with dynamite, you need a little charge to trigger the blast.

We often forget that classic silent directors used their pictorial techniques for suspense. Lang’s Mabuse films and Spione furnish plenty of instances, but so do the Soviet montage films. The scene in which the police wait for the worker to return to his wife in The End of St. Petersburg now looks like pure Hitchcock, and of course the Odessa Steps sequence was the Psycho shower of its day. So it isn’t surprising that Hitchcock would turn his silent-film virtuosity toward creating scenes of high tension and threatened violence. Nor is it surprising that his skills would crystallize in “set pieces.”

Everybody talks about Hitchcock’s fondness for set pieces. It’s part of his brand. We have the Statue of Liberty climax in Saboteur, the milk carried up the staircase in Suspicion, the milk-and-razor scene and the final suicide in Spellbound, the spectacular rescue of Alicia at the end of Notorious, and the efforts of Bruno to retrieve the lighter in Strangers on a Train.

But, come to think of it, what makes something a set piece?

Game, set piece, match

Foreign Correspondent (1940).

As commonly understood in the arts, a set piece is a fairly self-contained portion of a larger work. It has a distinct beginning and end, and it’s understandable and impressive if extracted from its original. It’s designed to be a bravura display of concentrated virtuosity. In music, an example would be an operatic aria like the Queen of the Night’s in The Magic Flute: it is so flashy and complete in itself that it can enjoyed on its own, in a concert setting.

Two early uses of the term shed light on its implications. In stage parlance, a “set piece” is an item of the set that can stand alone, like a gate or fake tree. In pyrotechnics, a “set piece” is a carefully patterned arrangement of fireworks; here again, it implies a display that dazzles the audience.

In the silent era, I’d suggest, the clearest exponent of set pieces is Eisenstein, who became known as “the master of the episode.” Many of his big scenes, like the Odessa Steps massacre, are developed at such length that they function as mini-films. But you can consider passages in Chaplin and Keaton as set pieces—the dance of the breadrolls in The Gold Rush perhaps, or the windstorm in Steambout Bill, Jr. The musical would seem to be a natural home of the set piece, with numbers standing out against more mundane scenes. In modern cinema, again under the aegis of Hitchcock: De Palma offers plenty, and perhaps the prize fights in Raging Bull constitute a string of them. Today the home of the set piece is the action picture; the chases and fights are the main attraction, and the genre challenges directors and crew to find new ways to intoxicate us.

The aesthetic of the set piece implies that some scenes function as filler while others get the whipped-up treatment. If that’s right, many great directors don’t favor mounting set pieces. Ozu, Mizoguchi, Dreyer, Hawks, and others present what we might call “through-composed” films. Just as Wagnerian opera and its successors minimized set pieces, these filmmakers create a surface texture that doesn’t create self-contained high points. (I grant you that the immolation of Herlofs Marthe in Dreyer’s Day of Wrath might count.)

Given the detachable quality of set pieces, it’s true that some of Hitchcock’s can seem implausible or gratuitous. How essential is Guy’s lighter to any plausible scheme of Bruno’s? If you want to kill Roger Thornhill, why send him to a crossroads in Midwest corn country? (A knife in the back on the Greyhound is more reliable.) It was this tendency to sacrifice story logic for stunning anthology bits that Raymond Chandler deplored:

The thing that amuses me about Hitchcock is the way he directs a film in his head before he knows what the story is. You find yourself trying to rationalize the shots he wants to make rather than the story. Every time you get set he jabs you off balance by wanting to do a love scene on top of the Jefferson Memorial or something like that.

Chandler has a point. How do you integrate a set piece into a whole movie? (I’ll make some suggestions shortly.) But first, give Hitch his due. For him, I think a set piece was a compact repository of inherently cinematic ideas carried to a limit within a sequence. A set piece is a challenge: How much can you squeeze out of a situation?

Go back to Foreign Correspondent. Setting an assassination in Amsterdam allowed Hitchcock to integrate the idea of a clue based on a waywardly turning windmill. So far, Chandler’s objection seems tenable: The windmill is just a gimmick. But once Hitchcock sets his hero exploring the lair, he can create a set piece that answers a question that no one ever thought to ask before: How do you eavesdrop in a windmill?

Johnny Jones has to evade the killers by crawling up alongside the giant gears, then down, then up again. At each step he barely escapes being spotted. When he seems safe, his topcoat gets snagged in the grinding gears, so he has to slip his arm out of it—just in time to avoid being crushed.

Yet once Jones is freed from the coat, it’s carried around the gearwork and might be spotted by the gang. And the old diplomat upstairs, mind hazed by drugs, is likely to reveal Jones’ presence. Hitchcock squeezes seven minutes of suspense out of all this, with a casual air that suggests: Of course, dear chap, any director worth his salary can see that a windmill harbors all kinds of excruciating menace. All in a day’s work, you know.

A whispered terror on the breeze

If anything is a set piece, the Albert Hall sequence in The Man Who Knew Too Much is. Philip Kemp’s commentary for the Criterion DVD considers it Hitch’s first, although aficionados would probably consider the “knife” sound montage of Blackmail at the very least a rough sketch for what would come. Lucky you: The entire Albert Hall sequence is excerpted on the Criterion site.

A set piece benefits from a simple premise. Here, Jill’s child is being held hostage, which keeps her from informing the police of what little she knows about the plot. We know that during the concert an assassin will try to shoot a diplomat.

You can imagine Chandler asking: Why plug Ropa during a concert, with all those witnesses? Why not when the target is on the sidewalk, shot from a rooftop for easy escape? You can hear that bland replying murmur: Raaaymond, it’s only a moovie…

So we have some conditions for a set piece: a compact piece of action limited in time and space. But there’s also a strong time marker. Ramon the assassin is to wait for a dramatic pause in the score; it’s followed by a shattering choral outburst that will muffle the pistol shot. We’ve been given a rehearsal of the passage in a gramophone record, but since we don’t hear the whole piece then, we can’t predict exactly when the chorus will hit its peak.

Hitchcock magnifies this uncertainty by letting the piece, Arthur Benjamin’s Storm Clouds Cantata, play out in its entirety. Its combination of lyrical and dramatic passages blend into a stream of music that coincides with the emotional action onscreen. I suspect that the piece, composed specifically for the film, glances at the most celebrated new choral piece of the era, William Walton’s Belshazzar’s Feast (1931). It too has a charged dramatic pause followed by a tremendous choral blast: “Slain!” You can listen to it here, and you can hear some of the musical affinities at 27:11 and after.

So the self-contained quality of the sequence is enhanced by the unfolding soundtrack, as well as its “bookend” structure: Jill arrives at the Albert Hall/ Jill leaves. (Hitchcock was very fond of this coming-and-going bracketing; many scenes of The Birds are built out of this.) But to be a set piece we need virtuosity too, right?

As our Film Art essay indicates, Hitchcock structures the scene using nearly every technique in the silent-cinema playbook. We get dynamically accentuated compositions, crisp point-of-view editing, subjective vision (even blurring as Jill drifts into a panicky reverie), and suspenseful crosscutting back to the gang holding Bob and Betty prisoner. The techniques build to their own crescendo, with more and shorter shots of Jill, the orchestra players, and the curtain concealing Ramon. As the climax approaches, details of the players’ performance pass in a flash. As another layer, though, all these visual techniques are synchronized with the musical structure of the piece. Most obvious is the slow tracking shot back from Jill as the female soloist launches in:

There came a whispered terror on the breeze./ And the dark forest shook.

The text has always teased me, because in my early years of studying the film I couldn’t hear everything there. Now that the Storm Clouds Cantata has become a minor concert piece, we have a full version of the text. It’s the description of an especially ominous storm, one that drives birds away and makes trees tremble in fear. The only creature left, vulnerable to the gale, is a child:

Around whose head screaming/ The night-birds wheeled and shot away.

The orchestral and choral forces mount on the line that has always come through the sound mix:

All save the child—all save the child.

The line is ambiguous. Its literal sense is that all the creatures have fled the oncoming storm except the child (“all save the child”). But Hitchcock’s cutting and the film’s overall context leave it as an imperative: the child must be rescued. Thus the musical dynamics and the text stress, for us and presumably for Jill, that Betty’s safety depends on what she does.

Soon the cantata’s text finds another analog in the concert hall. The choir sings of the storm clouds finally breaking and “finding release.” That phrase, repeated with rising intensity, yields the dramatic pause and then the final outburst that is to cover Ramon’s pistol shot. But now we have to see this phrase as prophecy and comment: Jill’s scream during the pause is the release of her tightened anxiety. And of course the line slyly signals the release of the suspense built up through the whole sequence.

With Hitchcock, you always get more.

In all, the sequence becomes exactly what a set piece ought to be: compact, with sharp boundaries and a strongly profiled arc of interest, elaborated with a great variety of technical resources and a thrusting emotional impact. But is it too much of an independent sequence? One can imagine Chandler worrying that Hitch doesn’t care much about how to hook it up with everything else. Let’s see.

This scepter’d isle

There’s no doubt that a plot driven by set pieces can seem episodic, just a matter of pretty clothes clipped to a slender line. In action movies it’s a classic problem, which, say, Speed doesn’t fully solve but Die Hard does.

You can mask an episodic plot, though, through some stratagems. First, make your filler material charming. The Man Who Knew Too Much gives us comedy in the dentist office and in the Tabernacle, with Bob and Clive mumbling messages through hymnody. You can also whisk the audience from scene to scene so quickly that the viewer has to concentrate on local connections. This is one purpose of what I’ve called the hook, the transition that smoothly links the end of one scene with the beginning of the next. If you’ve got some plot holes, strengthen your hooks–especially those that hide your gaps.

The Man Who Knew Too Much has some nifty hooks. I especially like the way the fingers pointing to the bullet hole are followed by a shot of Ramon’s head: effect and cause neatly given by a straight cut. Then there’s the contrast of the fire in the fireplace dissolving to the skier pin, a sort of thermal hook. But probably the most memorable one is Betty’s line about Ramon’s brilliantined hair.

This hook is a motif as well, and recurring images or sounds like this can help knit together your movie. In Foreign Correspondent, we get hats and birds in various scenes. Here, as our Film Art essay indicates, teeth, the skier pin, sharpshooting, the cantata’s main theme, and other motifs weave through the overall structure of the film.

You can as well knit your big scenes together through certain narrative patterns, such as a trip or a search, both strategies that Hitchcock employs in many movies. In The Man Who Knew Too Much, Bob’s investigation of the gang follows the menu set out in Louis’ note: the sun emblem, Wapping, G. Barbour, and A. Hall. This serves as a sort of map for the middle act of the film. Once Bob has cracked the message, though, the film shifts into a new register. Jill, who has been waiting passively at home, takes over the role of protagonist. And her actions will fulfill another motif: that of interruption and distraction.

The film begins with Betty’s dog disrupting Louis’ ski jump. That’s an innocent accident, as is the moment when Jill nearly spoils Roman’s skeet shooting. But soon afterward Abbott’s chiming watch deliberately breaks Jill’s concentration, making her lose the shooting match. In effect the Albert Hall sequence offers payback: With her scream Jill not only disrupts the performance but spoils Ramon’s aim as Abbott had spoiled hers.

The Albert Hall sequence fits into the film in a less obvious way, one that plays along the thematic dualities that marble the movie. Throughout the film contrasts “Englishness” with “foreignness,” the latter split between allies (Louis, Ropa) and enemies. The Storm Cloud Cantata and what follows represent a sort of triumph of England over her adversaries.

At the St. Moritz resort, the Lawrence family is set off from Louis, their French friend, and two men: Abbott the German and Ramon the Latin. (He’s handily fudged; he has a Spanish name but calls the English “extraordinaire.” And his hair is greasy.) “Sworn enemies, eh?” Jill says half-humorously to Ramon before losing the skeet shoot. After Louis’ death Bob is at a loss in the hotel, unable to speak German or Italian, and distracted while Betty is kidnapped. The English aren’t at home in this world.

Once Bob and Jill have returned to London, they join the family friend Clive, a Wodehousian upper-class twit but gifted with loyalty and tenacity. Bob and Clive have learned from Gibson of the Foreign Office that the gang intends to assassinate the diplomat Ropa. They must tell what they know; the killing could prove as catastrophic as the assassination that triggered the war of 1914-1918. Yet Bob keeps mum. He might be enacting E. M. Forster’s dictum: “If I had to choose between betraying my friend and betraying my country, I hope I would have the guts to betray my country.”

The conflict between family love and civic duty is played out in the rest of the second act, when the men’s investigation takes them to a working-class neighborhood of Wapping. There, we learn that behind respectable English institutions—a dentist, eccentric religion—foreign elements lurk. Bob has solved Louis’ riddle, but at the cost of becoming another hostage. Bob and Betty re-meet, in a characteristically subdued stiff-upper-lip encounter that denies Abbott the tearful scene he expected. The dignity with which Bob conducts himself, asking about Betty’s dressing gown and her school grades while staring defiantly at the gang, leaves the others abashed.

Clive has escaped, though, and has managed to send Jill to the Albert Hall. That musical set piece initiates the film’s climax dramatically but also thematically. For one thing, Benjamin’s cantata reaffirms another bit of Englishness. A national choral tradition runs back to Purcell and Handel, was sharpened in Mendelssohn’s Elijah, and was revived in the early twentieth century by Elgar’s Dream of Gerontius and Vaughan Williams’ Sea Symphony. Hitchcock and screenwriter Charles Bennett could have used Bach or Beethoven, but the choice of this brooding, mildly modernistic piece reminiscent of Walton is a nice bit of propaganda for British musical culture of the interwar years.

More importantly, the concert sequence solves the film’s ideological problem: How to save the world without destroying your family? Jill’s impulsive scream doesn’t divulge what she and Bob know about the gang, but it does serve to derail the gang’s plan and save Ropa. And by leading the police to follow Ramon to the hideout, she in effect chooses to risk Betty and Bob for the capture of the gang. Here, perhaps, the sheer drive of the action muffles the significance of her choice; Chandler complains that Hitchcock tended to take refuge from plot problems in “wild chases.”

What follows, in the middle of some violence that remains shocking today, is a vigorous reassertion of Englishness. The vignettes during the siege display stalwart national virtues. A postman insists on making his rounds during the gunplay. An inspector swipes sweets and pauses for a cup of tea. The police reluctantly take up arms, only after several of their unarmed number are mowed down. Slipping into adjacent buildings, snipers move a piano while its fussy owner rescues his potted plant. And a cop who was slated to go off duty finds a warm mattress to die on. This unassuming valor, so different from Ramon’s petulant swagger and Abbott’s self-congratulatory sadism, will win out. The victory is announced by the pent-up crowd rushing jubilantly forward as the siege ends.

In any other movie the mother would have been huddling with the child and the man would grab a rifle to pick off his enemy on the roof. But making Jill the crack shot reasserts another quintessentially English image: the hunting, shooting, riding mistress of the estate. She gets her second chance to fire, bringing down Ramon when even the police sniper hesitates. It’s also a bit of guilty revenge for the death of Louis, whom Jill danced into the line of fire. Hitchcock, as usual, renders it elliptically: we see Jill grab the gun but not fire it. As she and Bob and Betty are reunited, the movie that began with the line, “Are you all right, sir?” ends with a mother reassuring her weeping daughter, “It’s all right.”

This, we might say, is how you integrate set pieces into your movie—narratively, stylistically, and thematically. Others would disagree with me, but nearly forty years of living with this film hasn’t made me change my mind. The Man Who Knew Too Much is Hitchcock’s first thoroughgoing masterpiece.

Thanks to Abbey Lustgarten, UW-Madison alum, for her excellent production job on the Criterion disc. Thanks also to Peter Becker and Casey Moore for coordinating the posting of our Film Art piece with this blog entry.

For more on Chandler and Hitchcock, see William Luhr, Raymond Chandler and Film (New York: Unger, 1982), 81-93. My quotation comes from Raymond Chandler Speaking, ed. by Dorothy Gardiner and Kathrine Sorley Walker (Books for Libraries Press, 1971), 132.

Hitchcock probably doesn’t deserve 100% of the credit for the Foreign Correspondent windmill scene; it was designed by the great William Cameron Menzies.

When I wrote the Film Art analysis back in the 1970s, Kristin hadn’t elaborated her ideas about how large-scale parts, or acts, can shape a film. Yet I think that the three parts that the analysis mentions constitute pretty well-articulated acts. The first part has as its turning point Bob’s realization that when Gibson traces Betty’s call, police will converge on Wapping and endanger her. So Bob and Clive set out to save her. That decision comes about twenty-six minutes into the movie. I’d mark the end of the second act with Abbott’s sending Ramon on his mission after playing the cantata recording; that comes at about fifty-three minutes into the film. At this point we know everything we need to know, so the premises can play out. The last act is shorter, as climaxes tend to be. The Albert Hall sequence and the final shootout and rescue take up the final twenty-three minutes, capped by a very brief epilogue of the reunited family. For more on act structure, see Kristin’s entry here, mine here, and my essay on action movies, as well as Kristin’s Storytelling in the New Hollywood and my The Way Hollywood Tells It.

A final note: Frank Vosper, who plays Ramon, was a well-known stage actor and playwright. His most famous play is Love from a Stranger (1936); the film version was released in 1937. Another successful Vosper play was the fantasy comedy Murder on the Second Floor (1929), in which a writer devises a play consisting of all the clichés of sensational mystery fiction. But the Vosper play that piques my curiosity most is his 1927 drama called—I’m not kidding—Spellbound.

See? With Hitchcock you always get more.

The Man Who Knew Too Much.

Tony and Theo

Man on Fire (Tony Scott, 2004); The Suspended Step of the Stork (Theo Angelopoulos, 1991).

DB here:

In January of 2012, while shooting The Other Sea, Theo Angelopoulos was struck by a motorcyclist and died soon afterward. In August, Tony Scott committed suicide by jumping off Los Angeles’ Vincent Thomas Bridge.

Both men mattered to cinema. But which cinema?

From 1970 onward, Angelopoulos produced solemn films about Greek history, world war, emigration, and the collapse of struggles for political change. His hallmark was the extended—some said excruciating—long take. He presented his work as that of a thoughtful and passionate intellectual, a witness to history (or as he sometimes said, History) who was telling us hard, melancholy truths. His work received little mainstream distribution outside Europe and Japan, and some of his best films weren’t circulated nontheatrically or on video. Severe and abrasive, he alienated powerful members of film culture and was reported to have responded sourly when he did not win Cannes’ top prize.

By contrast, after Top Gun (1986), Tony Scott came to be the prototype of the ADD Hollywood director, a master of the blockbuster action picture. He gleefully marshaled visceral technique to jolt the eye and hammer the ear. His movies were unabashed booty calls, spotlighting female pulchritude in a tone of laddish camaraderie in an all-male milieu (sports, the military, the workplace). Not lacking intelligence, he avoided the sweeping pronouncements that made Angelopoulos look pretentious, but his early partnering with Simpson and Bruckheimer stamped him as raucously vulgar. He even dated Brigitte Nielsen.

Extremes meet

Déja vu (2008); Eternity and a Day (1995).

The statuesque versus the kinetic, the monumental versus the ephemeral, ponderousness versus cheap flash: To all appearances, these men lived in different cinematic worlds. Their careers were oddly counterpointed too. Angelopoulos, a festival darling in the 1970s and 1980s, became more unfashionable. By the time of his last release, The Dust of Time (2009), some critics were openly scornful. Scott faced gibes from the start but won some critical respect in the 2000s. After his death, critics were calling him a master. To many, Angelopoulos’s stubborn allegiance to 1970s modernism looked old hat, while Scott’s bodaciousness and eye candy seemed to have finally seduced audiences and critics alike.

I confess that both give me qualms. When Angelopoulos strains for significance, as he does at many moments throughout his oeuvre and almost constantly in The Dust of Time, he arouses all my impatience with pretentious Eurocinema. When Scott builds a scene out of Fuck-you-motherfucker dialogue and lingering views of pole dancers he reminds me of just how low contemporary American cinema can sink. And the style of each one can become predictable–an angled shot down a street portends a pan in Angelopoulos, while once somebody sits down in a Scott movie the camera is likely to start to twirl.

Despite these misgivings, I find that I can admire and enjoy both men’s films quite a lot. Their most venturesome work offers us powerful experiences, and they can teach us things about cinema—not least, how creative filmmakers can rework the medium and its historical traditions.

And their worlds overlap at least a little. Both men treat cinema as an art of scale. To see Man on Fire (2004) or Alexander the Great (1981) on home video, no matter how big your monitor, is to shrink the films fatally. Correspondingly both men relied on spectacle, stuffing the screen with sweeping, startling effects. True, Scott’s spectacle is maximalist, while Angelopoulos’s is austere. Yet once you’ve calibrated your bandwidth, the train that rumbles through the migrant camp in The Weeping Meadow (2004) becomes no less rattling than the rogue locomotive in Unstoppable (2010). “Go big or go home” might be each man’s motto.

Both play games with narrative as well. As early as The Hunger (1983) Scott’s incessant crosscutting uses the soundtrack of one line of action to comment on another. The time looping of Domino (2005) and Déja Vu (2008) creates flashbacks, replays, revised outcomes, and jumping viewpoints. More sedately, Angelopoulos perfected the time-shifting long take. The camera movements of The Traveling Players (1975) glide among different eras. From scene to scene, Angelopoulos will provide few marks of tense. Scene B may follow A, or precede it by several years, and no Hollywoodish superimposed title will help us out. It may be several minutes before we realize that decades have passed.

Yet the time-scrambling both directors enjoy isn’t wholly at the service of drama. Storytelling takes on a curiously subsidiary role in their work. Neither filmmaker, it seems to me, is centrally interested in probing what many of us take to be the core of narrative—character psychology. This isn’t to say there aren’t poignant moments and glimpses of inner lives. But each director also leaps beyond them.

I think in fact that Tony and Theo explore what happens when narrative slips away, when cinematic textures and patterning are allowed to override drama—to inflate it, deflate it, thrust it to one side, take it as a pretext for something more tangibly enthralling. Both filmmakers seek to shape our perception and emotion, letting the fluctuations of images and sounds engender a kind of mesmeric attention in themselves.

They accomplish this within two different traditions, that of modern Hollywood and that of “art cinema.” Yet they share a commitment to going beyond the given: Each director pushes his tradition to a limit.

Pulp fictions

Déja vu (2008).

Scott’s tradition is, most broadly, Hollywood narrative cinema, and up to a point he plays along. The plots are propelled by goal-directed characters who clash with others, and the results are contests (Top Gun, Days of Thunder, 1990), investigations (Beverly Hills Cop II, 1987; Man on Fire, Deja Vu), pursuits and conspiracies (Revenge, 1990; The Last Boy Scout, 1991; True Romance, 1993; The Fan, 1996; Enemy of the State, 1998; Spy Game, 2001; Domino), and ticking-clock suspense situations (Crimson Tide, 1995; The Taking of Pelham 123, 2009; Unstoppable).

At the center there usually stands one man, or a duo, who must undergo a test of courage and resourcefulness. In The Fan, an example of what Kristin has called the parallel-protagonist movie, a normal guy finds himself pursued by an obsessed admirer. A woman might serve as a gutsy partner, as in True Romance, or the object of the quest (Revenge, Spy Game), or the reward for success (The Last Boy Scout, Unstoppable). Only Domino has a female protagonist who survives through being as abrasive, dirty-minded, and foul-mouthed as her male partners and adversaries. Yet by her own admission, she has daddy issues and a longing to return to cozy wealth.

At bottom, then, Scott worked with straightforward pulp stories, and for about a decade he played them in the proper spirit. But with Enemy of the State (1998) he began to use the slipperier narrational strategies spreading through Hollywood of his time. Like Tarantino, who supplied the script of True Romance, Scott became willing—inspired, he suggests, by rock’n’roll and the films of Nicholas Roeg—to go a little wild.

His scripts started playing with what we usually call point of view. Some films become markedly, not to say traumatically, subjective. Spy Game splits the protagonist figure into two and gives us each one’s standpoint on the action. The Fan, from Peter Abraham’s fine novel, tracks a man’s obsession as it turns deadly. Man on Fire plunges into John Creasy’s mental world as he distills pain, guilt, piety, and alcoholism into a merciless sadism.

By the time we get to Domino, story presentation is pitilessly disjunctive. The main action is bracketed by a conventional frame showing the heroine telling her story to a police officer. A good thing, too; we couldn’t follow the action without her commentary. The tale fractures into quickfire AV displays, with pauses, backing-and-filling, alternative outcomes, and even written titles, as if we were getting the most juice-jangled PowerPoint talk in history.

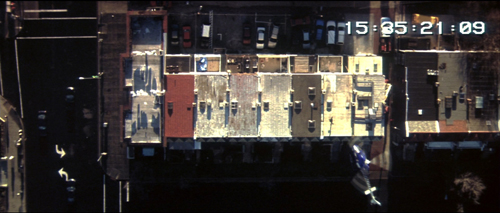

Another multiplication of perspective takes place via spy games. Most directors situate modern surveillance techniques within their story world; Paul Greengrass seems happiest shooting people bent over workstations. When your average director gives you a swooping helicopter shot, you don’t take it as the POV of a sinister government agency or a sensationalistic TV livecam. In Scott’s late films you’re likely to. He realized that all today’s security cameras, cellphones, and hostile eyes in the sky can do two useful things. They can chop story space and time into teasing fragments, and they can refresh the shot’s visual texture.

For quite some time Hollywood movies have used television for exposition. Characters tap into the flow of story events via TV broadcasts, and sometimes, as in The Siege (1998), the film simply cuts in news clips presented directly to us, without any mediating character. Passages like these, a contemporary equivalent of the newspaper headlines and radio broadcasts of classic studio cinema, usually smooth out the plot, linking things concisely.

But Scott takes pleasure in playing up the disparities among the footage, cutting from “direct” presentation of material to mediated images and sounds. In the conspiracy films, the video images seem to be coming from a vast image bank or database that the film is sampling on the fly. Moreover, the constant interruption of one shot by another, seen on computer or news broadcast or spycam, creates a nervous visual narration. In effect, Scott imports the mixed-format collages of Stone’s JFK (1991) into the action film (with more skill than Stone summoned up for Natural Born Killers of 1994 and U-Turn of 1997).

At the level of presentation, though, a narrower tradition shapes Scott’s style. In interviews and director commentaries he ceaselessly reminds us that he started out as a painter, and he has, I think, brought a fresh pictorial intelligence to the action film.

Too much is not enough

Days of Thunder (1990).

Like Michael Mann, Scott seems to have felt the need to give the action picture a dose of self-conscious artistry. The problem was the competition. The gold standard of the genre emerged in 1988 with the poised, tightly-woven classicism of John McTiernan’s Die Hard. How was an ambitious director to match that? Most directors were embracing variants of a style I’ve dubbed “intensified continuity”—fast cutting, simple staging, polar extremes of lens lengths, almost constant camera movement. The efficient but routine Richard Donner and Renny Harlin worked along these lines, while Michael Bay represented the style in almost pristine form. But what if a director who had trained as a painter at the Royal College of Art could take intensified continuity into new territory?

So yes, go along with the trend toward fast cutting; but make it even faster. In an era in the average shot in the average film runs between 3 and 5 seconds, why not make them 2 seconds? Or less? This was Scott’s choice from The Fan (1996) on. He seldom repeats a setup, largely because he has so many cameras stationed on the perimeter of the scene. Man on Fire contains at least 4100 shots, Domino over 5000, but perhaps we will never know just how many. Long passages are built out of multiple exposures, superimpositions, stop-and-go motion, and color shifts within a “shot.” The cut ceases to be a firm boundary as layers float up and slip away.

At times Scott, like Vertov in Man with a Movie Camera and Pat O’Neill in Power and Water, simply abandons the concept of a discrete shot, letting images seep through his frame.

And yes, move the camera; but move it in arabesques quite different from McTiernan’s unfussy following shots and tense track-ins. In particular, take the swirling camera as a given but then pivot your subject a bit as well. Cutting from one rotation to another can yield a little ballet of sculptural solidity, with barriers gliding by in the foreground and bursts of tonal values throughout. Here’s an example from Unstoppable.

In the 1980s and early 1990s films, Scott mixed haze and sharpness. Some scenes would be shot in metallic or earth tones and swathed in those smoky layers brother Ridley had popularized in Blade Runner. Other scenes would boast silhouettes, crisp edges, and blocks of bright color. Consider these images from Revenge, The Last Boy Scout (2 frames) and True Romance.

All framings–long-shot, medium-shot, close-up–tend to be covered by several cameras with very long lenses, which flatten and abstract the image. Later, having discovered the power of cross-processing reversal stock, Scott mostly gave up haze for what he called hyperrealism: high contrasts, along with Hockneyish color ripeness and thick but still transparent shadow regions.

Scott adds to the canons of intensified continuity the punch of the axial cut, that shot change that yanks figures toward or away from us (an effect that his last films mimicked by snap-zooms). Combined with long lenses set at various distances, this option creates a sense of constantly losing and refinding the point of the shot. As Connie swivels during a later stretch of the Unstoppable scene, the axial cut with different backgrounds pins her against varied blocks of color.

Critics complained that Scott’s style reminded them of MTV videos and commercials, a great number of which the Scott brothers produced. But there’s nothing inherently wrong with filmmakers drawing inspiration from advertising (as painters like Warhol and Stuart Davis did) or from video clips (as Wong Kar-wai seems to have done). What matters is what you do with your sources. It seems clear that Scott subjected these techniques to a new pressure, using them to thrust current norms to new extremes.

Intensified continuity, as I argued in The Way Hollywood Tells It, offers a mannerist version of classic continuity. If that’s accurate, then we might say that Scott provides a Rococo variant of intensified continuity itself. Michael Mann, another pictorialist, is more of a purist, seeking a sober gravity, while Scott doodles and scrawls across the surface of his scenes. Not only does he interpose reflections, rain, dust, and other particles between his subjects and us, but he reiterates lines of dialogue via supered titles.

Mann lets us soak up his images, but Scott tosses out one gorgeous composition after another in bewildering profusion. In the accelerated late films, they barely have time to register. The film seems to whisk away under our eyes. Shots lack an organic arc; they’re lopped off. Partial impressions pile up, defeating our urge to dwell on a composition. Sometimes you can’t trust your eyes. During the kidnap scene of Man on Fire, a thug prepares to shoot back at Creasy as a burst of flame is reflected in his car.

Problem is, nothing has caught fire in the scene; for once, no explosions. It’s purely a crazy jolt, literalizing the idea of a “firefight” without any realistic motivation.

These techniques are motivated to some degree by story demands: the need to suggest a mental state, to portray a heroic posture, or to amp up a fight or chase. But Scott’s visual and auditory handling exceeds the demands of clear storytelling. He wraps the most perfunctory dialogue scene in a dazzling embroidery that arrests attention in its own right. Mere decoration? I’d agree. Still, decorative art isn’t an unworthy calling, and decoration pursued with conviction and inventiveness demands our notice.

And this decoration isn’t dainty. Domino, Unstoppable, and the second half of Man on Fire have a grunge dimension, with shots that make our world look at once harsh and dazzling. Scott could be our Sam Fuller (complete with cigar), and Domino could be his Naked Kiss. Fuller might echo Scott’s gaffer, who said of Domino: It isn’t pretty, but it is beautiful.

Threnody

Ulysses’ Gaze (1995).

From The Birth of a Nation to Lincoln, American studio cinema tends to show grand historical events intertwining with the private dramas of great leaders or common folk. But there were other options. Eisenstein’s first three films—Strike, Battleship Potemkin, and October—floated the possibility of the “mass protagonist.” In these films, history is made by groups, and individuals are given largely symbolic roles. During the politicized 1960s, this model was taken up by filmmakers on the left.

The filmmaker who explored this option most fully was the Hungarian Miklós Jancsó. Although his films seem to be little-known today, he was a major force in reviving the idea of presenting history through group dynamics. Individuals play a role in The Round-Up (1965), Silence and Cry (1968), and The Confrontation (aka Bright Winds, 1969), but they are usually bereft of personal psychology. These figures are defined by their roles in a struggle—a civil war, a revolution, a clash with a domineering regime—and they are often pawns in a game of shifting power.

The Red and the White (1967), available on DVD, is a good example. This saga of the Russian Civil War that followed the 1917 revolution takes us through skirmishes between clashing armies, the tactics pursued by a squadron of Hungarian volunteers, and episodes in a Red Cross station. Individuals come to the fore briefly but are likely to vanish from later scenes, or simply die on the spot. One young Hungarian threads his way through the action, but he can hardly be said to be a point-of-view character, and we learn nothing of his background or motives. A great deal of the film is taken up with rituals of questioning prisoners, torturing and shooting captives, and ravaging innocents caught in the crossfire. At the climax, a tattered Red unit marches defiantly toward a superior White force, the entire confrontation played out in a stupendous landscape.

The Red and the White could defend itself from charges of formalism through its affinity with Soviet-style war dramas, but as Jancsó went on to examine episodes in Hungarian history, he soon gave up realism. He staged historical events in symbolic forms, on a bare plain or as obscure rituals in festivals rippling with music and dance. Examples are Agnus Dei (1972), and Red Psalm (1969; available on DVD). These films relied on endlessly tracking, craning, and zooming; the camera floats, and space stretches and squashes. The result was long-take extravaganzas. The Red and the White has fewer than two hundred shots; The Confrontation (1969) only thirty-five; Sirocco (1969) and Elektra, My Love (1974; on DVD) fewer than a dozen.

It seems to me that after Angelopoulos’s first film, he picked up and expanded Jancsó’s idea of investigating a nation’s history through mass dynamics and stripped-down spectacle. He proceeded more or less chronologically through modern Greek history. Days of ‘36 (1972) examines the dictatorial rule of General Metaxas (1937-1941) while The Traveling Players of 1975 covers the Nazi occupation and postwar civil strife. The Hunters (1977) revives the years from the civil war (1944-1949) to the mid-1960s through an arresting narrative device: present-day hunters find the corpse of a civil war partisan, as fresh as if killed yesterday. Alexander the Great (1980) doubles back to a period from the turn of the century until the 1930s, showing a bandit taking power over a remote village.

This tetralogy did pick out individuals, but it made them symbols of larger forces, often through names drawn from history or mythology. The travelling players are named Electra, Orestes, and the like; Alexander the bandit is a brutish version of his legendary namesake. Nevertheless, Angelopoulos’ presentation did little to acquaint us with them from the inside. He drew on none of Scott’s subjective tricks to convey instant impressions or fragments of memory; even his quasi-subjective flashbacks were likely to include the protagonist as he is today in the scene from the past.

Popular filmmaking depends on our accessing characters’ thoughts and feelings, but Angelopoulos largely gave that up. He made his plots depend on large-scale political forces. Sometimes, as in Days of ’36 and The Hunters, we are taken behind the scenes and shown the machinations of power, but usually history unfolds through impersonal forces—often outside the frame. When the apparatus of power is made visible, it’s through visions of police, soldiers, or other authorities. And those are often presented as rigid and impersonal.

Below, in Ulysses’ Gaze, a candlelight march is confronted by row upon row of police. The calm, mechanical way the officers fill up the middle ground makes the impending conflict quite suspenseful. When you think the composition, and the confrontation, have exhausted the shot’s duration and space, a crowd of citizens appears in the foreground to bear witness. All three groups are made into homogeneous blocks through the distant framing and the consistency of texture (flickering candles, uniforms, umbrellas).

The drama comes when our characters are forced to respond to the forces of oppression. They flee, they hide, or they’re captured and sent to prison or execution or exile. It’s an inglorious version of history, filtered through a Brechtian belief that distancing us from charged situations, presenting emotions dryly rather than melodramatically, can bring lucidity and a grasp of macro-dynamics. But Angelopoulos also traced his the origins of his oblique, sometimes opaque style to the pressures of censorship. Under the Greek junta, it was impossible to speak about history directly.

So I sought a secret language. Tacit understanding of the story. The temps morts in plotting a conspiracy. The unsaid. Elliptical discourse as an aesthetic principle. A film in which everything that is important takes place outside the frame.

Even after censorship ceased, Angelopoulos continued in this taciturn vein, making his films thoroughly decentered and dedramatized.

Yet in the 1980s, he tried to offer audiences more. He began to put distinct and individualized characters at the center of his films, and he achieved his survey of political change by sending them on modern Odysseys. In Voyage to Cythera (1983) a film director is conceiving a new project, and he visualizes the story of an elderly Communist let out of prison and returning to his village. In The Beekeeper (1985), a schoolteacher abandons his family and embarks on a trip across a bleak modern Greece. Landscape in the Mist (1988) follows two children convinced that their emigrant father is waiting for them just across the border. In The Suspended Step of the Stork (1991) a television journalist tracks down a prominent politician who seems to be hiding in a refugee village.

Two 1990s films plumb the characters’ pasts in more detail. Ulysses’ Gaze (1995) follows an archivist (called simply A) searching for a lost film and his own family history in the Balkans. In Eternity and a Day (1998), a poet in the last days of his life reflects on his life while accompanying a boy trying to return to Albania.

In the 2000s Angelopoulos began again thinking on an epic scale. Trilogy: The Weeping Meadow (2004) announced itself as the first installment in nothing less than a history of the twentieth century told through the experience of a single family. Concentrating on a refugee couple—one Russian, one Greek—it sets their fugitive romance against the events of World War I, the rise of Fascism, and the Greek Civil War, while also hinting at parallels to Attic tragedy. The second installment, The Dust of Time (2009) runs parallel to Voyage to Cythera and Ulysses’ Gaze in centering on a filmmaker, but he becomes less central to the plot than his father, his mother, and his mother’s lover–all victims of 1950s Soviet Communism who survive to see the fall of the Berlin wall.

Over these years, Angelopoulos collaborated with the Italian screenwriter Tonino Guerra (who died about two months after the director). Guerra, who worked with Antonioni, Fellini, the Tavianis, and many other directors, may have helped turn Angelopoulos toward less forbidding storytelling. The more vividly drawn protagonists of the late work were often played by well-established actors (Mastrioanni, Moreau, Ganz, Keitel, Dafoe, Piccoli), and two of the films center on children, one common way to kindle emotion. Eleni Karaindrou’s scores, full of threnodies rising up from massed strings, by also gave the films after Cythera a plangent warmth reminiscent of doleful musical pieces by Henryk Górecki and Arvo Pärt.

Still, these late films are only comparatively more accessible. Their stories come across as downbeat, episodic, relatively empty of conventional drama, full of “dead time” and unmarked time shifts, and deeply somber. Which is to say that they belong to the broader tradition of postwar European art cinema, its norms given fresh realization through echoes of Greek mythology and a signature style of exceptional rigor.

Stasis and sublimity

Alexander the Great (1981).

At the level of technique Angelopoulos again emerges as a synthesizer. An admirer of Mizoguchi and Antonioni, and again probably influenced by Jancsó, he became identified with the long take. From The Traveling Players on, scenes are presented in very few shots, often only a single one. Three films of the tetralogy contain between 125 and 150 shots, while The Hunters makes do with 49. And most of the films are very long (two nearly four hours), so the average shot length runs from 72 seconds (Days of ’36) to 206 seconds (The Hunters). As the later films became more accessible, the editing paced quickened only a little: no film has more than a hundred shots, and in all the average shot runs between fifty seconds and two minutes. Add together all the shots in Angelopoulos’ thirteen features and you have less than a third of the shots in, say, Scott’s Enemy of the State.

Most long-take filmmakers scale their framings to human activity; think of Ophuls and Renoir, capturing gestures and reactions as time flows through the image. But Angelopoulos combined the long take with the long shot, putting landscape at the center of his work. The stunning shot I’ve excerpted from The Red and the White above isn’t wholly typical of Jancsó’s films, which tend to have many close framings and to save vast views for climactic moments. By contrast, Angelopoulos makes very distant shots his default mode for exteriors, even for moments of high drama: a conversation in The Hunters, a death in Alexander the Great.

There are very few conventional close-ups in his films, and mid-shots are often forced on him by fully-built interiors, either locations or sets, as in the frame below from The Weeping Meadow. Even then, the camera often keeps its distance, subordinating characters to impersonal architecture and making their encounters seem fragile (The Suspended Step of the Stork).

Sometimes the tableau that results has considerable depth, as with groups gathered in interiors (The Hunters, below). More pointedly, a horrifying scene in Landscape in the Mist almost cruelly forces our eye back into the distance. In each shot, the most important action is furthest from the camera.

At other moments the long shot yields what I’ve called planimetric images. There’s still a fair amount of depth, but the shot is framed perpendicular to a back plane and figures are spread out in strips or layers. Some images earlier in today’s entry afford examples, particularly the developing street confrontation in Ulysses’ Gaze. The Weeping Meadow shows that this principle can be applied to a raft and rowboats too.

Like Scott, Angelopoulos relies on very long lenses, but he holds the shot so that the flattening effect of the lens creates a gradually changing pattern.

Both depth framings and planimetric ones were exploited by European filmmakers of the late 1960s and early 1970s, but Angelopoulos focused rigorously on them and joined them with consistently distant camera positions. As the dramaturgy downplays individual psychology, the shot scale makes individuals figures in a landscape. The result is often a rhythmic organization of the frame, a pattern of symmetries and abstract geometries (Traveling Players, The Dust of Time).

In the later films, moments of personal drama are played out in no less opaque distant shots. In Voyage to Cythera, the exile’s wife goes to their old cottage and coaxes him out. They must be exchanging a look of understanding, but only on the big screen is it visible.

Such fixed shots are riveting enough, but how can the filmmaker dynamize them and prepare for them? The answer for Angelopoulos was keeping the frame mobile. He refuses the giddy sweep and beguiling tempo of Jancsó. Angelopoulos is severe. Like Scott, he will use the zoom, but his enlargements or de-enlargements are stately, not staccato. (Again, that Red and the White shot may have been an early model for him.) In all, his mobile framings are as austere as the color palettes (earth and metal tones) and the lighting (subdued, often chiaroscuro, with usually a drab sky).

His camera pans with passing characters, sometimes letting them come close enough for us to identify them or catch an expression; a prolonged traveling shot follows Spyros’ wife in the scene above as she approaches the fence. But the very plainness of this technique can sharpen our expectations. As often in postwar European film, the extended, dialogue-free walk creates its own arc of interest. We rarely know where a character is headed on that walk, or what they see that makes them approach. In a way this technique recalls the thriller or horror film: show the reaction and pan to the cause of it. But with Angelopoulos that cause will tend to be something stupefying in scale, a revelation of a side of the world we haven’t suspected, perhaps a realm closer to surrealism (The Suspended Step of the Stork; Trilogy: The Weeping Meadow).

Hallucinatory images like these, presented with a calm gravity, suggest that the forces of history, like Goya’s dreams of reason, bring forth monsters—not raging and tumultuous ones, but ones displaying deathly, disturbing stillness. The emotional shock of the characters communicates itself to us as a pictorial shock, itself achieved by the simplest means. In Eternity and a Day, the protagonist and the boy come upon a refugee camp where the detainees, clinging to the fence, seem suspended in the mist.

The result of all these creative choices is a cinematic pageant, and not only because of its splendid imagery. Like the medieval pageant wagons that rolled scene after scene past a crowd, Angelopoulos’ scenes become a procession of tableaux. They are broken by movements—sometimes slow, sometimes sudden, almost always small. Only he could imagine this shot in Alexander the Great in which a tourist edges out from behind a pillar at the Temple of Poseidon and lifts his finger for silence. His arm arrests our attention without losing the monumental context.

If Tony Scott’s images are hurled out in a mad rush, Angelopoulos gives us time to see the smallest changes. Sometimes these emerge in cramped interiors, guided by aperture staging or a gliding camera. At other moments we must scan a vast space to spot our protagonists. What eighteenth-century thinkers called the Sublime, the fearsome majesty we apprehend in the enormity of the world outside ourselves, as during a storm at sea, has been given a political weight. Not despair, Angelopoulos insists, or even pessimism: rather, a collective melancholy at recognition of a sad destiny.

Like Scott, Angelopoulos pushed to new extremes certain premises of the traditions he chose to work in: Dedramatization, depersonalization, the long take, a reliance on staging that is dense or spacious, deep or planar, and the urge to represent history and contemporary life in a more abstract, majestic way. Heir to Antonioni and Jancsó, he carried their visual ideas to new limits and showed what more they could do. That strategy laid bare his own artifice, to the point that the minute fluctuations of style–no less “cinematic” than Scott’s–fascinate us in their own right.

All I’ve done is to trace some curves and whorls of each filmmaker’s signature, his characteristic principles of handling story and style in relation to the norms of his time. I haven’t tried to launch fine-grained analyses of particular scenes or entire films. Both are necessary, of course. Still, the sort of analysis I’ve outlined seems to me essential to appreciating their work fully.

That work has something broader to teach us about film and film criticism. Too often critics think that their job is to expose a film’s meanings. For most critics, that often entails a Zeitgeist interpretation. The movie is held to reflect the events, popular mood, or wish-fulfillment needs of its time. For academic critics, the hunt for meaning may also entail mapping a set of theoretical concepts onto the film, as with psychoanalytic or postmodernist interpretations.

But filmmakers like Scott and Angelopoulos remind us that we should say, more accurately, that films produce effects, of which meanings are only one type. The film provokes us to have an experience, part of which may be the search for themes and implications, but another part–perhaps the biggest and most basic one–is a guided process of perception, thinking, and emotion.

Of course, meanings matter. Enemy of the State warns us about how surveillance and data-mining can obliterate personal identity. Landscape in the Mist suggests that in the age of migrant labor, disputed boundaries, and ethnic wars, Europe has destroyed childhood. So far, so good; and we should go further. But tracing the dynamics of theme still obliges us to analyze the perceptible force of these films. That, I think, can best be recognized through a study of how the resources of cinema are deployed to give us an experience that isn’t reducible to paraphrasable ideas.

These cinematic resources, flaunted without apology from moment to moment, are the fabric of the movie. In fact, both men pretty relentlessly drain their scenes of thematic meaning. In Enemy of the State, Scott piles up so many surveillance and counter-surveillance stratagems that the anti-technology message seems just a pretext to multiply images, switch points of view, and futz up our own information-processing. In Ulysses’ Gaze, the shot of a dismantled Lenin statue floating down the river on a barge makes its “statement” immediately, but Angelopoulos won’t let it go. He follows its progress, shows people on the river banks kneeling and praying to it, and accompanies the whole sequence with Karaindrou’s surprisingly lilting music. The Symbol of Dead Communism has been drained of its portent and has become a curiously lyrical audio-visual display. These men go so far that they come out the other side.

Accordingly, both have been called heavy-handed: one is shallow, the other hollow. Granted, many viewers find art works that depend on kinetic impact or slow accumulation unsubtle. Yet sometimes force, bursting out or released in minute doses, is welcome. The Rite of Spring and Threnody for the Victims of Hiroshima both strike with a physical impact. Here the odd couple Tony and Theo find one more affinity: They suggest that subtlety in the arts may be overrated.

Information about the posse Tony Scott ran with in his early days can be found in Charles Fleming, High Concept: Don Simpson and the Hollywood Culture of Excess (Main Street, 1999). The gaffer discussing Domino is Bruce McCleery, and I’ve paraphrased his original comment: “It’s definitely not pretty, but on some level it can be truly beautiful.” See Pauline Rogers, “Lady Killer,” ICG Magazine (October 2005), 35.

Scott’s death has provoked a lot of good writing on the Net. See for example Manohla Dargis, “A Director who Excelled in Excess”; Jim Emerson, “Films on fire”; Christoph Huber and Mark Peranson, “World Out of Order: Tony Scott’s Vertigo”; Ignatiy Vishnevetsky’s “Smearing the Senses: Tony Scott, Action Painter”; and, for discussions of individual sequences, see “Tony Scott, a Moving Target,” the remarkable round-robin hosted by MUBI and Daniel Kasman and Gina Telaroli. Reliably, David Hudson has compiled web critics’ reactions at Fandor.

Jancsó’s films deserve closer scrutiny than they’ve received. My Narration in the Fiction Film includes an analysis of The Confrontation (not, so far as I know, available on DVD).

Perversely, having claimed that these directors’ images suffer when reduced, I’ve given you postage-stamp illustrations, and for this I apologize. Take them as waving you toward the need to see the films at full stretch. As for their quality, I’ve drawn as many illustrations from 35mm prints as I had available, but I’ve been obliged as well to rely on DVD copies, and those yield uneven results in the Angelopoulos frames. For discussions of the versions of his films available on DVD, see the Criterion Forum and Mubi.

The critical and academic literature on Angelopoulos is decently varied. Dan Fainaru’s Theo Angelopoulos: Interviews is a very good place to start. The best overview of most of the oeuvre is Andrew Horton’s Films of Theo Angelopoulos, which provides essential historical and biographical background. See also Andy’s anthology, The Last Modernist. For Cineaste Andy also wrote a touching reminiscence on the occasion of the director’s death. Catherine Grant has assembled a vast online dossier at Film Studies for Free, and David Hudson has charted immediate web responses here.

The French journal Positif was a loyal supporter of Angelopoulos, publishing articles and informative interviews for decades. My quotation above comes from Angelopoulos’s essay, “In my end is my beginning,” Positif no. 463 (September 1999), 62.

A little discussion of Angelopoulos, in the context of the fortunately short-lived ruckus about eat-your-vegetables cinema, can be found in this entry on our site. Chapter 4 of Figures Traced in Light: On Cinematic Staging is an expanded version of my essay in Andy Horton’s collection, and I’ve borrowed some of its ideas here. I hope to write more about Tony Scott’s work on this website later this year.

Enemy of the State (1998); The Traveling Players (1975).

What next? A video lecture, I suppose. Well, actually, yeah….

DB here:

We’ve said several times that this website is an ongoing experiment. We started just by posting my CV and essays supplementing my books. Then came blogs. We quickly added illustrations to our entries, mostly frame enlargements and grabs. Eventually, video crept in. In 2011 we ran Tim Smith’s dissection of eye-scanning in There Will Be Blood. Last year, in coordination with our new edition of Film Art: An Introduction, we added online clips-plus-commentary (an example is on Criterion’s YouTube channel), and near the end of the year Erik Gunneson and I mounted a video essay on techniques of constructive editing.

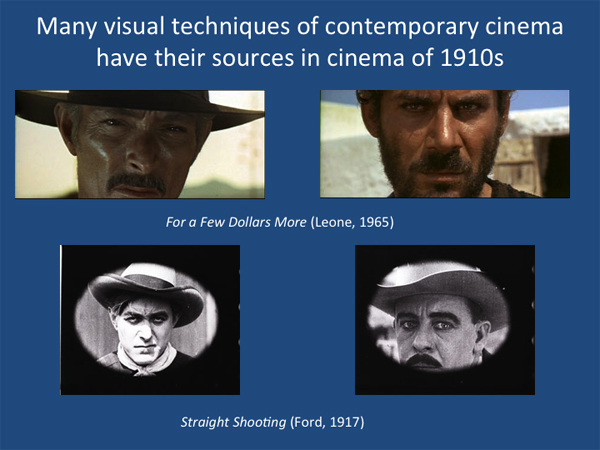

Today something new has been added. I’ve decided to retire some of the lectures I take on the road, and I’ll put them up as video lectures. They’re sort of Net substitutes for my show-and-tells about aspects of film that interest me. The first is called “How Motion Pictures Became the Movies,” and it’s devoted to what is for me the crucial period 1908-1920. It quickly surveys what was going on in cinema over those years before zeroing in on the key stylistic developments we’ve often written about here: the emergence of continuity editing and the brief but brilliant exploration of tableau staging.

The lecture isn’t a record of me pacing around talking. Rather, it’s a PowerPoint presentation that runs as a video, with my scratchy voice-over. I didn’t write a text, but rather talked it through as if I were presenting it live. It nakedly exposes my mannerisms and bad habits, but I hope they don’t get in the way of your enjoyment.

“How Motion Pictures Became the Movies” is designed for general audiences. I’ve built in comments for specialists too, in particular, some indications of different research approaches to understanding this period of change.

The talk runs just under 70 minutes, and it’s suitable for use in classes if people are inclined. I think it might be helpful in surveys of film history, courses on silent cinema, and courses on film analysis. If a teacher wants to break it into two parts, there’s a natural stopping point around the 35-minute mark.

Some slides have several images laid out comic-strip fashion, so the presentation plays best on a midsize display, like a desktop or biggish laptop. A couple of tests suggest that it looks okay projected for a group, but the instructor planning to screen it for a class should experiment first.

I plan to put up other lectures in a similar format, with HD capabilities. Next up is probably a talk about the aesthetics of early CinemaScope. I’d then like to spin off this current one and offer three 30-minute ones that go into more depth on developments in the 1910s.

The video is available at the bottom of this entry, but it’s also available on this page. There I provide a bibliography of the sources I mention in the course of the talk, as well as links to relevant blogs and essays elsewhere on the site.

If you find this interesting or worthwhile, please let your friends know about it. I don’t do Twitter or Facebook, but Kristin participates in the latter, and we can monitor tweets. Thanks to Erik for his dedication to this most recent task, and to all our readers for their support over the years.