Archive for the 'Film technique: Editing' Category

News! A video essay on constructive editing

DB here:

In connection with our textbook, Film Art: An Introduction, we’ve created several videos examining film techniques. Thanks to Peter Becker and Kim Hendricksen of Criterion Classics and Janus Films, we’ve been able to include clips from film classics, from Ashes and Diamonds to Ugetsu Monogatari. Because our publisher McGraw-Hill sponsored the production of these pieces, most of them are on a dedicated website called Connect, accessible only to students and teachers using the book in courses. We’ve made one video freely available on Criterion’s own site, where Kristin discusses some editing techniques in Agnès Varda’s Vagabond.

But not everybody who reads Film Art is in a course using the online supplements. And some people who aren’t reading Film Art might still enjoy learning more about the topics we cover. Moreover, we’ve had such good response to the Connnect clips that we decided to create a longer, more wide-ranging piece, also suitable for classrooms. So we prepared another video and today are making it available to anyone.

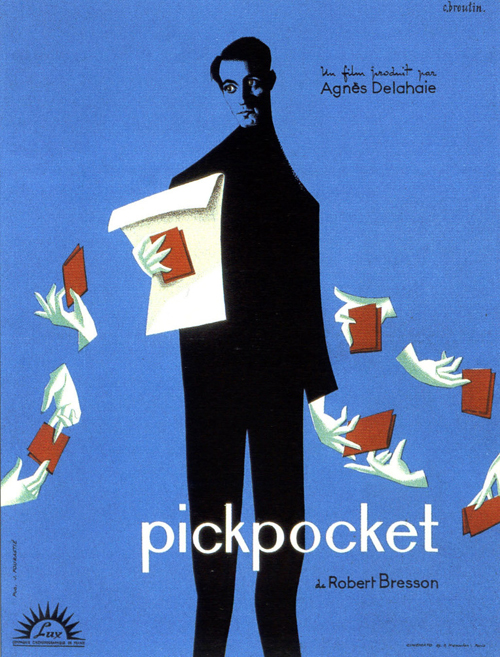

The Connect pieces mostly concentrate on single scenes, whereas this one roams across several films before focusing on a single example. Specifically, we look at the technique of constructive editing, which we discuss in Chapter 6 of FA. The video draws examples from silent films including Harold Lloyd’s Number, Please? (1920) and Lev Kuleshov‘s Engineer Prite’s Project (1918), while our more recent examples include The Social Network and The Ghost Writer. Thanks again to Criterion, the extract we focus on comes from Bresson’s brilliant Pickpocket (1959).

This piece is produced by Erik Gunneson, a local filmmaker who did an excellent job on the Connect materials. I wrote the script and narrated. (A cold I couldn’t shake off betrays itself in my voice.) We did the work in our production facility here at the University of Wisconsin–Madison Department of Communication Arts.

The links flagged above indicate blogs that are related to this new video. Some others are “What happens between shots happens between your ears” and “The Movie looks back at us” and “They’re looking for us.” There’s also “Three nights of a dreamer,” discussing a passage in In the City of Sylvia that may be a slantwise homage to Bresson’s editing technique.

Just to be clear: The twelve-minute video is available to anyone who’s interested. You can watch it below or on Vimeo. Erik, Kristin, and I hope you enjoy it.

PS 4 November 2012: Our discussion of the Kuleshov effect has led some to ask us whether the several videos on YouTube are authentic footage of Kuleshov’s experiments. Alas, they are not, but Kristin and I don’t know their provenance. However, in Oksana Bulgakowa’s documentary on the Kuleshov effect, available on YouTube, there are some fragments of the surviving footage, starting at 4:28. Oksana has also helped complete the experiment by inserting a substitute for a missing shot. In addition, I’m reminded by Joe McBride and Katharine Spring of Hitchcock’s famous explanation of the Kuleshov effect, available on the DVD, A Talk with Hitchcock. An excerpt from that is posted on YouTube, probably illegally.

Nolan vs. Nolan

DB here:

Paul Thomas Anderson, the Wachowskis, David Fincher, Darren Aronofsky, and other directors who made breakthrough films at the end of the 1990s have managed to win either popular or critical success, and sometimes both. None, though, has had as meteoric a career as Christopher Nolan.

His films have earned $3.3 billion at the global box office, and the total is still swelling. On IMDB’s Top 250 list, as populist a measure as we can find, The Dark Knight (2008) is ranked number 8 with over 750,000 votes, while Inception (2010), at number 14, earned nearly 600,000. The Dark Knight Rises (2012), on release for less than a month, is already ranked at number 18. Remarkably, many critics have lined up as well, embracing both Nolan’s more offbeat productions, like Memento (2000) and The Prestige (2006), and his blockbusters. Nolan is now routinely considered one of the most accomplished living filmmakers.

Yet many critics fiercely dislike his work. They regard it as intellectually shallow, dramatically clumsy, and technically inept. As far as I can tell, no popular filmmaker’s work of recent years has received the sort of harsh, meticulous dissection Jim Emerson and A. D. Jameson have applied to Nolan’s films. (See the codicil for numerous links.) People who shrug at continuity errors and patchy plots in ordinary productions have dwelt on them in Nolan’s movies. The attack is probably a response to his elevated reputation. Having been raised so high, he has farther to fall.

I have only a welterweight dog in this fight, because I admire some of Nolan’s films, for reasons I hope to make clear later. Nolan is, I think all parties will agree, an innovative filmmaker. Some will argue that his innovations are feeble, but that’s beside my point here. His career offers us an occasion to think through some issues about creativity and innovation in popular cinema.

Four dimensions, at least

First, let’s ask: How can a filmmaker innovate? I see four primary ways.

You can innovate by tackling new subject matter. This is a common strategy of documentary cinema, which often shows us a slice of our world we haven’t seen or even known about before—from Spellbound to Vernon, Florida.

You can also innovate by developing new themes. The 1950s “liberal Westerns” substituted a brotherhood-of-man theme for the Manifest-Destiny theme that had driven earlier Western movies. The subject matter, the conquest of the West by white settlers and a national government, was given a different thematic coloring (which of course varied from film to film). Science fiction films were once dominated by conceptions of future technology as sleek and clean, but after Alien, we saw that the future might be just as dilapidated as the present.

Apart from subject or theme, you can innovate by trying out new formal strategies. This option is evident in fictional narrative cinema, where plot structure or narration can be treated in fresh ways. Many entries on this blog have charted possible formal innovations, such as having a house narrate the story action, or arranging the plot so as to create contradictory chains of events. Documentaries have experimented with a film’s overall form as well, of course, as The Thin Blue Line and Man with a Movie Camera. Stan Brakhage’s creation of “lyrical cinema” would be an example of formal innovation in avant-garde cinema.

Finally, you can innovate at the level of style—the patterning of film technique, the audiovisual texture of the movie. A clear example would be Godard’s jump cuts in A Bout de souffle, but new techniques of shooting, staging, framing, lighting, color design, and sound work would also count. In Cloverfield and Chronicle, the first-person camera technique is applied, in different ways, to a science-fiction tale. Often, technological changes trigger stylistic innovation, as with the Dolby ATMOS system now encouraging filmmakers to create sound effects that seem to be occurring above our heads.

I see other means of innovation—for instance, stunt casting, or new marketing strategies—but these four offer an initial point of departure. How then might we capture Nolan’s cinematic innovations?

Style without style

Well, on the whole they aren’t stylistic. Those who consider him a weak stylist can find evidence in Insomnia (2002), his first studio film. Spoilers ahead.

A Los Angeles detective and his partner come to an Alaskan town to investigate the murder of a teenage girl. While chasing a suspect in the fog, Dormer shoots his partner Hap and then lies about it, trying to pin the killing on the suspect. But the suspect, a famous author who did kill the girl, knows what really happened. He pressures Dormer to cover for both of them by framing the girl’s boyfriend. Meanwhile, Dormer is undergoing scrutiny by Ellie, a young officer who idolizes him but who must investigate Hap’s death. And throughout it all, Dormer becomes bleary and disoriented because, the twenty-four-hour daylight won’t let him sleep. (His name seems a screenwriter’s conceit, invoking dormir, to sleep.)

Nolan said at the time that what interested him in the script—already bought by Warners and offered to him after Memento—was the prospect of character subjectivity.

A big part of my interest in filmmaking is an interest in showing the audience a story through a character’s point of view. It’s interesting to try and do that and maintain a relatively natural look.

He wanted, as he says on the DVD commentary, to keep the audience in Dormer’s head. Having already done that to an extent in Memento, he saw it as a logical way of presenting Dormer’s slow crackup.

But how to go subjective? Nolan chose to break up scenes with fragmentary flashes of the crime and of clues—painted nails, a necklace. Early in the film, Dormer is studying Kay Connell’s corpse, and we get flashes of the murder and its grisly aftermath, the killer sprucing up the corpse.

At first it seems that Dormer intuits what happened by noticing clues on Kay’s body. But the film’s credits started with similar glimpses of the killing, as if from the killer’s point of view, and there’s an ambiguity about whether the interpolated images later are Dormer’s imaginative reconstruction, or reminders of the killer’s vision—establishing that uneasy link of cop and crook that is a staple of the crime film.

Similarly, abrupt cutting is used to introduce a cluster of images that gets clarified in the course of the film. At the start, we see blood seeping through threads, and then shots of hands carefully depositing blood on a fabric (above). Then we see shots of Dormer, awaking jerkily while flying in to the crime scene. Are these enigmatic images more extracts from the crime, or are they something else? We’ll learn in the course of the film that these are flashbacks to Dormer’s framing of another suspect back in Los Angeles. Once again, these images get anchored as more or less subjective, and they echo the killer’s patient tidying up.

Nolan’s reliance on rapid cutting in these passages is typical of his style generally. Insomia has over 3400 shots in its 111 minutes, making the average shot just under two seconds long. Rapid editing like this can suit bursts of mental imagery, but it’s hard to sustain in meat-and-potatoes dialogue scenes. Yet Nolan tries.

In lectures I’ve used the scene in which Dormer and Hap arrive at the Alaskan police station as an example of the over-busy tempo that can come along with a style based in “intensified continuity.” In a seventy-second scene, there are 39 shots, so the average is about 1.8 seconds—a pace typical of the film and of the intensified approach generally.

Apart from one exterior long-shot of the police station and four inserts of hands, the characters’ interplay is captured almost entirely in singles—that is, shots of only one actor. Out of the 34 shots of actors’ faces and upper bodies, 24 are singles. Most of these serve to pick up individual lines of dialogue or characters’ reactions to other lines. The singles are shot with telephoto lenses, a choice exemplifying what I called the tendency toward “bipolar” lens lengths in intensified continuity–that is, either very long lenses or fairly wide-angle ones.

Fast cutting like this need not break up traditional spatial orientation. In this scene, there are a couple of bumps in the eyeline-matching, but basically continuity principles are respected. As Nolan explains on the DVD commentary, he tried to anchor the axis of action, or 180-degree line, around Dormer/Pacino, so the eyelines were consistent with his position, and that’s usually the case here.

I can’t illustrate all the shots here, but despite its more or less cogent continuity, the scene seems to me choppy, uneconomical, and fairly perfunctory in its stylistic handling. Nolan makes no effort to move the actors around the set in a way that would underscore the dramatic development. Because of the rapid editing, characters’ lines and gestures are cut off or unprepared for. There is no effort to design each shot, à la Hitchcock, to fit the line or reaction of the actor. Most shots are excerpted from full takes, all from the same setup. The most obvious example is the setup that pans to show Dormer as he comes in, stops, and reacts to the conversation. Thirteen shots are taken from that setup (not necessarily the same full take, of course, as the last frame here shows).

In Nolan’s recent films, this avoidance of tightly designed compositions may be encouraged further because he’s shooting in both the 1.43 Imax ratio and the 2.40 anamorphic one. There remains a general tendency toward loose, roughly centered framings.

Somebody is sure to reply that the nervous editing is aiming to express Dormer’s anxiety about the investigation into his career. But that would be too broad an explanation. On the same grounds, every awkwardly-edited film could be said to be expressing dramatic tensions within or among the characters. Moreover, even when Dormer’s not present, the same choppy cutting is on display.

Consider the 23 shots showing Ellie greeting Dormer and Hap as they get off the plane. Again we have full production takes broken up into brief phases of action (it takes five shots to get Dormer out of the plane), with an almost arbitrarily succession of shot scales. When Ellie leaves her vehicle to go out on the pier, the action is presented in nine shots.

We can imagine a simpler presentation—perhaps after an establishing shot, we track with Ellie down along the dock (so we can see her smiling anticipation), then pan with her walking leftward into a framing that prepares for the plane hatch to open. Arguably, the need to show off production values—the vast natural landscape, the swooping plane descending—pressed Nolan to include some of the extra shots. They don’t do much dramatically, and the strange cut back to an extreme long-shot (to cover the change to a new angle on Ellie?) may negate whatever affinity with her that the closer shots aim to build up.

Swedish sleeplessness

Magic Mike.

Want an up-to-date comparison? Steven Soderbergh’s Magic Mike has a quiet, clean style that conveys each story point without fanfare. Soderbergh saves his singles for major moments and drops back for long-running master shots when character interaction counts. His cuts are just that; they trim fat. He doesn’t resort to those short-lived push-in camera movements that Nolan seems addicted to. He doesn’t waste time with filler shots of people going in and out of buildings, or aerial views of a cityscape. Soderbergh can provide an unfussy 70s-ish telephoto long take of Mike and Brooke walking along a pier and settling down at a picnic table in front of a Go-Kart track while her brother Adam materializes in the distance. In a single year, with Contagion, Haywire, and Magic Mike, Soderbergh has confirmed himself as our master of the intelligent midrange picture. To anyone who cares to watch, these movies give lessons in discreet, compact direction.

For a more pertinent contrast case, we can go back Insomnia’s source, the 1997 Norwegian film of the same name written and directed by Erik Skjoldbjaerg. Here a Swedish detective, vaguely under suspicion for an infraction of duty, comes to a town on the Arctic Circle for a murder investigation. The plot is roughly similar in its premise, but the working out is quite different, and I can’t do justice to it here. Let me mention just two points of contrast.

First, the cutting is less jagged. Skjoldbjaerg’s film comes in at ninety-seven minutes, about fifteen minutes shorter than Nolan’s, and its cutting rate is much slower, around 5.4 seconds. That means that many passages are built out of sustained shots, particularly ones showing the detective Jonas Engström walking or sitting in a brooding, self-contained silence. Also, this version finds ways to convey several bits of information concisely, in carefully designed shots. For a straightforward example: We see Engstrom’s eyes open, as he’s unable to sleep, and then he lifts his head. Rack focus to the clock behind him.

Nolan uses several shots to get across a comparable point.

As for subjectivity, Skoldbjaerg is just as keen to get us inside his detective’s head as Nolan is. At times he uses the sort of flash-cutting Nolan employs, so we get fragmentary reminders of the fog-clouded shooting. But Skoldbjaerg doesn’t tease us with unattributed inserts (Nolan’s flashbacks to Dormer’s framing of a suspect), and he never suggests, via images of the murder and its cleanup, that his detective can imagine the crime concretely. Instead, Skoldbjaerg often evokes his character’s unease through camera movements that upset our sense of his spatial location. The camera shows Engstrom striding into a room…and then swivels rightward to show him in his original location, as if he’s sneaked around behind our back.

Then Engstrom turns, and we hear a footstep. Cut to a shot showing that the sound is made by him, walking in another room.

I’m not going to suggest that Skoldbaerg innovates more radically than Nolan does, though most viewers probably are more startled by these devices than by Nolan’s. I think that the original Insomnia’s stylistic gamesmanship owes something to other precedents, going back to Dreyer’s Vampyr. What I find more interesting is that Nolan had available the prior example of these strategies from his Nordic source, and he still chose to go with the more conventional, cutting-based options.

The editing-driven, somewhat catch-as-catch-can approach to staging and shooting is clearly Nolan’s preference for many projects. He doesn’t prepare shot lists, and he storyboards only the big action sequences. As his DP Wally Pfister remarks, “What I do is not complicated.” Comparing their production method to documentary filming, he adds: “A lot of the spirit of it is: How fast can we shoot this?”

Throwing it against the wall

We can find this loose shooting and brusque editing in most of Nolan’s films, and so they don’t seem to me to display innovative, or particularly skilful, visual style. I’m going to assume that his strengths aren’t in the choice of subjects either, since genre considerations have kept him to superheroics and psychological crime and mystery. I think his chief areas of innovation lie in theme and form.

The thematic dimension is easy to see. There’s the issue of uncertain identity, which becomes explicit in Memento and the Batman films. The lost-woman motif, from Leonard’s wife in Memento to Rachel in the two late Batman movies, gives Nolan’s films the recurring theme of vengeance, as well as the romantic one of the man doomed to solitude and unhappiness, always grieving. If this almost obsessive circling around personal identity and the loss of wife or lover carries emotional conviction, it owes a good deal to the performances of Guy Pearce, Hugh Jackman, Christian Bale, and Leonardo DiCaprio, who put some flesh on Nolan’s somewhat schematic situations.

You can argue that these psychological themes aren’t especially original, especially in mystery-based plots, but the Batman films offer something fresher. The Dark Knight trilogy has attracted attention for its willingness to suggest real-world resonance in comic-book material. Umberto Eco once objected that Superman, who has the power to redirect rivers, prevent asteroid collisions, and expose political corruption, devotes too much of his time to thwarting bank robbers. Nolan and his colleagues have sought to answer Eco’s charge by imbuing the usual string of heists, fights, chases, explosions, kidnappings, ticking bombs, and pistols-to-the-head with sociopolitical gravitas. The Dark Knight invokes ideas about terrorism, torture, surveillance, and the need to keep the public in the dark about its heroes. Something similar has happened with The Dark Knight Rises, leaving commentators to puzzle out what it’s saying about financial manipulation, class inequities, and the 99 percent/ 1 percent debate.

Nolan and his collaborators are doubtless doing something ambitious in giving the superhero genre a new weightiness. Yet I found The Dark Knight Rises, like its predecessor, unable to bear the burden. It seemed to me at once pretentious and confused in a manner typical of Hollywood’s traditional handling of topical themes.

The confusion comes into focus when journalists, needing an angle on this week’s release, look for a coherent reflection of that elusive, probably imaginary zeitgeist. I think that most popular films don’t capture the spirit of the time, assuming such a thing exists, but simply opportunistically stitch together whatever lies to hand. Let me recycle what I wrote four years ago.

I remember walking out of Patton (1970) with a hippie friend who loved it. He claimed that it showed how vicious the military was, by portraying a hero as an egotistical nutcase. That wasn’t the reading offered by a veteran I once talked to, who considered the film a tribute to a great warrior.

It was then I began to suspect that Hollywood movies are usually strategically ambiguous about politics. You can read them in a lot of different ways, and that ambivalence is more or less deliberate.

A Hollywood film tends to pose sharp moral polarities and then fuzz or fudge or rush past settling them. For instance, take The Bourne Ultimatum: Yes, the espionage system is corrupt, but there is one honorable agent who will leak the information, and the press will expose it all, and the malefactors will be jailed. This tactic hasn’t had a great track record in real life.

The constitutive ambiguity of Hollywood movies helpfully disarms criticisms from interest groups (“Look at the positive points we put in”). It also gives the film an air of moral seriousness (“See, things aren’t simple; there are gray areas”). . . .

I’m not saying that films can’t carry an intentional message. Bryan Singer and Ian McKellen claim the X-Men series criticizes prejudice against gays and minorities. Nor am I saying that an ambivalent film comes from its makers delicately implanting counterbalancing clues. Sometimes they probably do that. More often, I think, filmmakers pluck out bits of cultural flotsam opportunistically, stirring it all together and offering it up to see if we like the taste. It’s in filmmakers’ interests to push a lot of our buttons without worrying whether what comes out is a coherent intellectual position. Patton grabbed people and got them talking, and that was enough to create a cultural event. Ditto The Dark Knight.

Since I wrote that, Nolan has confirmed my hunch. He says of the new Batman movie:

We throw a lot of things against the wall to see if it sticks. We put a lot of interesting questions in the air, but that’s simply a backdrop for the story. . . . We’re going to get wildly different interpretations of what the film is supporting and not supporting, but it’s not doing any of those things. It’s just telling a story.

Just to be clear, I don’t think the just-telling-a-story alibi is bulletproof. The cultural mix on display in a movie can still exclude certain ideological possibilities, or frame the materials in ways that slant how spectators take them up. My point is only that we ought not to expect popular movies, or indeed many movies, to offer crisp, transparent visions of politics or society. Thematic murkiness and confusion are the norm, and the movie’s inconsistencies may reflect nothing more than the makers’ adroit scavenging.

Subjectivity and crosscutting

Nolan’s innovations seem strongest in the realm of narrative form. He’s fascinated by unusual storytelling strategies. Those aren’t developed at full stretch in Insomnia or the Dark Knight trilogy, but other films put them on display.

One way to capture his formal ambitions, I think, is to see them as an effort to reconcile character subjectivity with large-scale crosscutting. Nolan has pointed out his keen interest in both strategies. But on the face of it, they’re opposed. Techniques of subjectivity plunge us into what one character perceives or feels or thinks. Crosscutting typically creates much more unrestricted field of view, shifting us from person to person, place to place. One is intensive, the other expansive; one is a local effect, the other becomes the basis of the film’s enveloping architecture.

The Batman trilogy has plenty of crosscutting, but as far as I can tell, subjectivity takes a back seat. Nolan’s first two films reconcile subjectivity and crosscutting in more unusual ways. Following takes a linear story, breaks it into four stretches, and then intercuts them. But instead of expanding our range of knowledge to many characters, nearly all the sections are confined to what happens to one protagonist, and they’re presented as his recounted memories in a Q & A situation.

Likewise, Memento confines us to a single protagonist and skips between his memories and immediate experiences. Again what might be a single, linear timeline is split, but then one series of incidents is presented as moving chronologically while another is presented in reverse order. Again, the competing time trajectories aren’t presented as large blocks but are fairly swiftly crosscut.

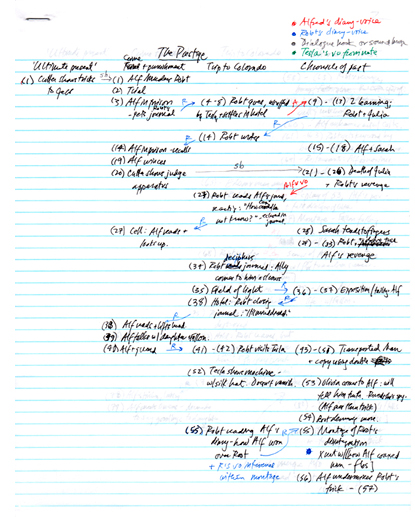

In The Prestige, dual protagonists, both with a secret, take over the story, but the presentation remains steeped in subjectivity. Now much of the action is filtered through each magician’s notebook of jottings and recollections, translated into voice-over commentary. One character may be reading another’s notebook in which the writer reports reading the first character’s notebook! And of course these tales-within-tales are intercut, with one man’s frame story alternating with the other’s past experience. You can work it all out diagrammatically, as I tried to do in my notes (on right).

In The Prestige, dual protagonists, both with a secret, take over the story, but the presentation remains steeped in subjectivity. Now much of the action is filtered through each magician’s notebook of jottings and recollections, translated into voice-over commentary. One character may be reading another’s notebook in which the writer reports reading the first character’s notebook! And of course these tales-within-tales are intercut, with one man’s frame story alternating with the other’s past experience. You can work it all out diagrammatically, as I tried to do in my notes (on right).

With Inception, subjectivity takes the shape of dreaming, and the crosscutting is now among layers of dreams. The embedding that we find in The Prestige is now carried to an extreme; in the long, climactic final sequence a group dream frames another dream which frames another, and so on, to five levels. Once again, these all get intercut (although Nolan wisely refrains from reminding us of the outermost frame too often, so that our eventual return to it can be sensed more strongly).

Kristin and I have written at length about these strategies in earlier entries (here and here). To recapitulate, Kristin found Inception‘s reliance on continuous exposition a worthwhile experiment, and I argued that the lucid-dreaming gimmick was simply a motivational strategy, a pretext for connecting multiple plotlines through embedding rather than parallel action. My point in the first essay is summed up here:

As ambitious artists compete to engineer clockwork narratives and puzzle films, Nolan raises the stakes by reviving a very old tradition, that of the embedded story. He motivates it through dreams and modernizes it with a blend of science fiction, fantasy, action pictures, and male masochism. Above all, the dream motivation allows him to crosscut four embedded stories, all built on classic Hollywood plot arcs. In the process he creates a virtuoso stretch of cinematic storytelling.

My later thoughts tried to survey the breadth of Nolan’s development of formal strategies. Here’s my conclusion:

From this perspective, Inception marks a step forward in Nolan’s exploration of telling a story by crosscutting different time frames. You can even measure the changes quantitatively. Following contains four timelines and intercuts (for the most part) three. Memento intercuts two timelines, but one moves backward. Like Following, The Prestige contains four timelines and intercuts three, but it opens the way toward intercutting embedded stories. The climax of Inception intercuts four embedded timelines, all of them framed by a fifth, the plane trip in the present. For reasons I mentioned in the previous post, it’s possible that Nolan has hit a recursive limit. Any more timelines and most viewers will get lost.

The Dark Knight Rises hasn’t dulled my respect for Nolan’s ambitions. Very few contemporary American filmmakers have pursued complex storytelling with such thoroughness and ingenuity.

Nolan has made his innovations accessible, I argued, by the way he has motivated them. First, he appeals to genre conventions. Following and Memento are neo-noirs, and we expect that mode to traffic in complex, perhaps nearly incomprehensible plotting and presentation. He has called Inception a heist film, and what many viewers objected to—its constant explanation of the rules of dream invasion—is not so far from the steady flow of information we get in a caper movie. In the heist genre, Nolan remarks, exposition is entertainment. Further, the separate dreams rely on familiar action-movie conventions: the car chase that ends with a plunge into space, the fight in a hotel corridor, the assault on a fortress, and so on.

But I should have mentioned another method of motivation–one that helps make the films comprehensible to a broad audience. In some cases the formal trickery is justified by the very subjectivity the film embraces. It’s one thing to tell a story in reverse chronology, as Pinter does in Betrayal; but Memento’s broken timeline gets extra motivation from the protagonist’s purported (not clinically realistic) anterograde memory loss. (We’ve already seen a lot of amnesia in film noirs.) Subjectivity is enhanced by the almost constant voice-over narration, reiterating not only Leonard’s thoughts but what he writes incessantly on his Polaroids and his flesh.

In The Prestige, each magician’s journal records not only his trade secrets but his awareness that his rival might be reading his words, so we ought to expect traps and false trails. And in Inception, the notion of plunging into a character’s mind becomes literalized as a dream state. Once we accept the conceit of controlled dreaming, we can buy all the spatial and temporal constraints the dream-master Cobb sets forth. As with Memento, Nolan creates a set of rules that allow him to crosscut many different time lines. In each film, the subject matter—memory failure, magicians’ enigmas, controlled dreaming—serves as an alibi for both subjectivity and broken timelines.

Synching story and style

Can you be a good writer without writing particularly well? I think so. James Fenimore Cooper, Theodore Dreiser, Sherwood Anderson, Sinclair Lewis, and other significant novelists had many virtues, but elegant prose was not among them. In popular fiction we treasure flawless wordsmiths like P. G. Wodehouse and Rex Stout and Patricia Highsmith, but we tolerate bland or clumsy style if a gripping plot and vivid characters keep us turning the pages. From Burroughs and Doyle to Stieg Larsson and Michael Crichton, we forgive a lot.

Similarly, Nolan’s work deserves attention even though some of it lacks elegance and cohesion at the shot-to-shot level. The stylistic faults I pointed to above and that echo other writers’ critiques are offset by his innovative approach to overarching form. And sometimes he does exercise a stylistic control that suits his broader ambitions. When he mobilizes visual technique to sharpen and nuance his architectural ambitions, we find a solid integration of texture and structure, fine grain and large pattern.

Here’s a one-off example. Nolan has remarked that he’s mostly not fond of slow-motion simply to accentuate a physical action, or to suggest some mental state like dream or memory. Inception motivates slow-motion by another of its arbitrary rules, the idea that at each level of dreaming time moves at a different rate. Here a stylistic cliché is transformed by its role in a larger structure, as Sean Weitner pointed out in a message to us.

Memento displays a more thoroughgoing recruitment of style to the purposes of guiding us through its labyrinth. The jigsaw joins of the plot require that the head and tail of each reverse-chronology segment be carefully shaped, because they will be reiterated in other segments. Within the scenes as well, Nolan displays a solid craftsmanship, with mostly tight shot connections and an absence of stylistic bumps.

He can even slow things down enough for a fifty-second two-shot that develops both drama and humor. Leonard has just shown Teddy the man bound and gagged in his closet, and Teddy wonders how they can get him out. In a nice little gag, Leonard produces a gun from below the frameline (we’ve seen him hide it in a drawer) and then reflects that it must be his prisoner’s piece. This sort of use of off-frame space to build and pay off audience expectations seems rare in Nolan’s scenes.

The moment is capped when Leonard adds, “I don’t think they let someone like me carry a gun,” as he darts out of the frame.

The straightforward stylistic treatment of Memento‘s more-or-less present-time scenes, both chronological and reversed, is counterbalanced by the rapid, impressionistic handheld work that characterizes Leonard’s flashbacks to his domestic life and his wife’s death (in color) and his flashbacks to the life of Sammy Jankis (in black-and-white). Nolan shrewdly segregates his techniques according to time zone.

If anything, The Prestige displays even more exactitude. Facing two protagonists and many flashbacks and replayed events, we could easily become lost. Here Nolan doesn’t use black-and-white to mark off a separate zone. Instead he relies more on us to keep all the strands straight, but he helps us with voice-overs and repeated and varied setups that quietly orient us to recurrent spaces and circumstances. Here Nolan’s preference for cutting together singles is subjected to a simple but crisp logic that relies on our memory to grasp the developing drama.

I’ve discussed these stylistic strategies in another entry and in Chapter 7 of Film Art. More generally, they serve the larger dynamic of the plot, which creates a mystery around Alfred Borden, hides crucial information while hinting at it, invites us to sympathize with Borden’s adversary Robert Angier (another widower by violence), and then shifts our sympathies back to Borden when we learn how the thirst for revenge has unhinged Robert. To achieve the unreliable, oscillating narration of The Prestige, Nolan has polished his film’s stylistic surface with considerable care.

Midcult auteur?

Trying to specify Nolan’s innovations, I’m aware that one response might be this: Those innovations are too cautious. He not only motivates his formal experiments, he over-motivates them. Poor Leonard, telling everyone he meets about his memory deficit, is also telling us again and again, while the continuous exposition of Inception would seem to apologize too much. Films like Resnais’ La Guerre est finie and Ruiz’s Mysteries of Lisbon play with subjectivity, crosscutting, and embedded stories, but they don’t need to spell out and keep providing alibis for their formal strategies. In these films, it takes a while for us to figure out the shape of the game we’re playing.

We seem to be on that ground identified by Dwight Macdonald long ago as Midcult: that form of vulgarized modernism that makes formal experiment too easy for the audience. One of Macdonald’s examples is Our Town, a folksy, ingratiating dilution of Asian and Brechtian dramaturgy. Nolan’s narrative tricks, some might say, take only one step beyond what is normal in commercial cinema. They make things a little more difficult, but you can quickly get comfortable with them. To put it unkindly, we might say it’s storytelling for Humanities majors.

Much as I respect Macdonald, I think that not all artistic experiments need to be difficult. There’s “light modernism” too: Satie and Prokofiev as well as Schoenberg, Marianne Moore as well as T. S. Eliot, Borges as well as Joyce. Approached from the Masscult side, comic strips have given us Krazy Kat and Polly and Her Pals and, more recently, Chris Ware. Nolan’s work isn’t perfect, but it joins a tradition, not finished yet, of showing that the bounds of popular art are remarkably flexible, and imaginative creators can find new ways to stretch them.

Box-office figures for Nolan’s films are compiled from Box Office Mojo. For detailed critiques of Nolan’s style, see Jim Emerson’s entries archived here; Jim’s video essay dissecting one Dark Knight action scene is here. A. D. Jameson’s essays on Inception are here and here.

Nolan discusses the background to Insomnia in John Pavlus, “Sleepless in Alaska,” American Cinematographer 83, 5 (May 2002), 34-45. My quotation about subjectivity comes from pp. 35-36. By the way, Insomnia does create a moment of tense quiet during the longish dialogue between Dormer and the killer Finch (Robin Williams) on the ferry: some sustained two shots give the adversaries time to size each other up (and Pacino gets an occasion to execute some business with an iron pole). Although the setup is broken by some irrelevant cutaways to the passing vistas, perhaps to cover faults in the takes, the sequence shows something of the sustained calm that we find in moments in Memento and The Prestige.

Thanks to Jonah Horwitz for the Wally Pfister link.

Umberto Eco’s 1972 essay, “The Myth of Superman,” appears in his book, The Role of the Reader. Portions are available here. One relevant passage is this: “He is busy by preference, not against black-market drugs nor, obviously, against corrupt administrators or politicians, but against bank and mail-truck robbers. In other words, the only visible form that evil assumes is an attempt on private property” (p. 123; italics in original).

Dwight Macdonald’s 1960 essay is available in Masscult and Midcult. A pdf is online here. Macdonald seems to have softened his demands a bit in later years. He praised 8 1/2, softcore modernism for sure, as Shakespearean in its vivacity. “The general structure–a montage of tenses, a mosaic of time blocks–recalls Intolerance, Kane, and Marienbad, but in Fellini’s hands it becomes light, fluid, evanescent. And delightfully obvious.” The essay is reprinted in Dwight Macdonald on Movies, pp. 15-31.

J. J. Murphy has a detailed analysis of Memento in his book Me and You and Memento and Fargo. I discuss the film’s contribution to complex storytelling trends in The Way Hollywood Tells It, pp. 74-82, where I also discuss the notion of intensified continuity editing. We analyze The Prestige‘s narrative, narration, and sound techniques in Film Art: An Introduction (ninth ed., pp. 298-307; tenth ed., pp. 298-306).

P.S. 19 August: Thanks to Guillaume Campreau-Dupras for correcting a film title.

PS 27 August: Thanks to the many bloggers and tweeters who linked to this entry!

The tireless A. D. Jameson has posted another probing critique of Nolan’s Bat-saga, this one concentrating on TDKR, here. While making serious points about Nolan’s use of expository dialogue and the confused politics of the film, the essay also contains some good jokes.

Not-quite-lost shadows

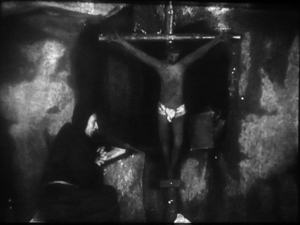

I.N.R.I.: The Catastrophe of the People (1920).

DB here:

One way to write the history of film as an art is to chart firsts. When was the first close-up, the first moving camera, the first use of cutting? Asking such questions was a common strategy of the earliest film historians, and it has persisted to this day in pop histories. Civilian readers can be excused for thinking that Griffith invented the close-up and Welles originated ceilings on sets. These myths have been recycled for decades.

The “revisionist” historians of the 1970s, mostly academics who aimed to do primary research, pointed out that talking about first times is risky. Too often the official account is wrong, and earlier instances can be found. In most cases, we can’t really know about first times. Too many films have vanished, and nobody can see everything that has survived. Innovation is always worth studying, but, the revisionists argued, it’s best understood within a context.

So they set themselves to figuring out not when certain cinematic techniques began but when they became common practice–when most filmmakers in a given time or place adopted them. That way we can discover innovations more reliably; they’ll stand out against the background of more orthodox choices. But of course, to build up a sense of these norms, it’s not enough to focus on the masterpieces cited in the official histories. You need bulk viewing.

Studying norms of storytelling and visual style is a large part of what Kristin and I have done since the 1970s. One section of our 1985 book The Classical Hollywood Cinema tried to chart when certain fundamental techniques of Hollywood storytelling coalesced into common practice. Kristin argued that the late 1910s are the key years, with 1917 as a plausible tipping point. By then, continuity editing and goal-oriented plotting, among other creative options, became dominant practices in American features. If you’re interested in blog posts touching on this, see the codicil.

Yet it’s reasonable to ask: But what happened in other countries? Was Hollywood unique, or were there comparable norms emerging in Russia, France, Germany, Denmark, Sweden, and elsewhere?

Several years ago, I began trying to watch as many US and overseas features from the period 1908-1920 just to see what I might find. Doing this led me to make arguments about the development of staging-driven cinema (often, but not only, European), as opposed to editing-driven cinema (usually, but not invariably, American).

A vast resource for my bulk viewing of 1910s cinema has been the Royal Film Archive here in Brussels. While the collection houses virtually every classic, it also includes films that haven’t been discussed by many historians–obscurities, if not downright rarities. Films from many countries passed through Brussels, and the archive was able to acquire copies from many distributors going back to the 1910s. Although I had watched several German films in the collection on earlier visits, this year I had a pretty concentrated dose. So as in previous years (see that codicil again), I offer you some chips from the workbench.

Cinematic scarcity

I.N.R.I.

German films of this period are of special interest for my research questions because of an unusual situation. From 1916, films from the US and nearly all of Europe were banned from Germany, and this ban held good until 31 December 1920. As Kristin puts it in her book Herr Lubitsch Goes to Hollywood (available as a pdf here):

Foreign films appeared only gradually on the German market. In 1921, German cinema emerged from years of artificially created isolation. . . .Because of the ban on imports, German filmmakers had missed the crucial period when Hollywood’s film style was changing rapidly and becoming standard practice. . . . The continuity editing system, with its efficient methods of laying out a clear space for the action, had already been formulated by 1917. The three-point system of lighting was also taking shape. In contrast, German film style had developed relatively little during this era.

Kristin was again exploring craft norms, the creative choices favored by Lubitsch’s contemporaries. She drew some of her evidence from films she saw here at the Cinematheque, but I wanted to revisit those and see some others. What exactly did German films look like at this point? Not the official classics like Caligari and Nosferatu, but more ordinary, maybe even bad movies?

The basic assumption: Since the German directors weren’t seeing American movies, they’d be less likely to imitate them. Some hypotheses follow from this. German directors would presumably rely less on cutting, especially within scenes, than Americans did. They might incline toward staging complicated action in a single shot. The cutting is likely to be what Kristin calls “rough continuity” or “proto-continuity”–essentially, long shots of the whole action broken by occasional axial cuts that enlarge something for emphasis. We wouldn’t expect to find sustained passages of close-up or medium-shot framings.

To give myself some reference points, on each visit I’ve watched European films in conjunction with American films of the same era. This mental trick helped differences pop out more easily.

Fortunately for peace in our household, I’ve found Kristin’s claims about German cinema well-founded. As in other years, I also stumbled across some gratifyingly strange movies.

Blocking, tackled

Throughout the period 1908-1920, we find many scenes staged in a single fixed shot. In many other blog entries, and in books like On the History of Film Style and Figures Traced in Light, I’ve tried to show that this wasn’t simply a passive recording of a “theatrical” scene. Drawing on capacities specific to the film medium, directors used composition, lighting, setting, and figure movement to shape the perceptual and emotional flow of the scene.

Here’s a late example from The Brothers Karamazov (1920) directed by Carl Froelich and Dmitri Buchowetzki. Starring Fritz Kortner, Emil Jannings, Werner Krauss, and other heavyweights, it has perhaps more ham per square inch than any other film I saw on this pass. Yet its tableau moments subordinate the performers’ charisma to an overall expressive dynamic.

Old Fyodor Karamazov has been murdered, and his son Dmitri is accused of the crime. Protesting his innocence, he’s about to be arrested when Grushenka bursts out. “I’m the guilty one!”

In the tableau tradition, “blocking” takes on a double meaning–not only arranging actors in the shot, but also judiciously using them to mask or reveal areas of space. Thus Dmitri at first blocks Grushenka, but when he lowers his hands, she pops into visibility–frontal and centered, so we can’t miss her. Dmitri sinks to the lower half of the shot when her dialogue title comes up, leaving her to command the frame. Meanwhile the police official has pivoted slightly, making sure that we pay attention to her outburst. Not incidentally, he blocks another policeman behind him, keeping the frame dominated by Grushenka.

This scene goes on quite a bit longer, with some careful balancing and rebalancing of points of interest in the lower part of the frame. The action ends with a nice touch: the embracing Dmitri and Grushenka are separated, and she’s pulled away, one arm flailing.

Without benefit of cutting, then, techniques of tableau construction guide our attention smoothly in the frame by using movement, centering, advance to the camera, character looks, blocking and revealing, and other tactics.

The Germans had embraced this tableau option in the earliest 1910s. The films of Franz Hofer and others show how an entire scene could be covered in a single camera position, with staging providing a continuous flow of interest. Go here for an amusing example from The Boss of the Firm, a 1914 comedy starring Lubitsch.

The commitment persisted into later years. The earliest film I watched in this cycle, Hilde Warren and Death (1917), by the quite interesting director Joe May, had several passages of tableau staging. In the most elaborate one, the mistress of Hilde’s dissolute son tells him that now he’s out of money, she has switched her affections to a rival. It plays out without a cut or intertitle for about a minute at 18 frames per second. When Fernande spurns him, he grovels, just as the salon door opens. (Whenever there’s a rear door like this, we’re likely to get a tableau scene.) His rival shows up to take her to the opera.

Fernande asks him to stay outside, but the son demands that he stay, waving his hand. In a staging tactic that should be familiar to us now, the son rises, blocking the rival for an instant.

The rival rebalances the composition, and makes himself visible, by moving to the right background. This switching of characters’ position in the frame is known as the Cross. But when the son gets angry, the rival crosses again, easing himself toward the area of conflict. Note that the son’s bodily attitude, tensing up, actually shifts him rightward a little, opening up a space for the other actor to be seen.

Now the rival steps to the forefront and wedges himself in between Fernande and the son. He invites the young man to leave, with a gesture that occupies the dead center of the frame: Who could miss its assured insolence? And now the maid, previously in the background and blocked by Fernande, makes herself known. Seeing how things are developing, she fetches the son’s hat.

The son gets off one last grimace, front and center, before departing. As he walks back, the rival swivels to blot him out, leading the ladies in mocking laughter. (It’s clear the rival belongs to the 1%.)

One good Cross deserves another: Now the rival settles in where the son was at the start of the scene, and the son is retreating in shame along the rival’s path.

This tableau technique, constantly calculating points of interest from the standpoint of monocular projection–that is, what the camera lens takes in–is far from theatrical. Well-timed blocking and revealing wouldn’t work given the multiple sightlines of a theatre stage. The action is staged for the only eye that matters: the camera’s.

Once we grant that theatrical playing space is quite different from that provided by the camera, we can see more exactly what the tableau tradition owes to the stage. Silent cinema’s “precision staging,” as Yuri Tsivian has called it, is close to choreography. If we want to appreciate what directors of this period accomplished we need to look at the scenes as varieties of pictorialized dance, designed around the axis of the camera lens.

Along the lens axis

To return to the first question: Yes, German films seem to have clung to the tableau tradition after 1917, when Americans had abandoned it. Yet shots like those in The Brothers Karamazov and Hilde Warren are fairly rare; most scenes in most German films of the period use a fair amount of editing. What do we make of that?

The trend is fairly general. Some staging-driven films, like Ingeborg Holm (1913) and the early serials of Feuillade, are built entirely out of one setup per scene, occasionally broken by cut-ins of printed matter or other details. This period constituted a brief golden age of this “tableau” tradition–visible in American cinema, but more pervasive in European cinema. But by the late 1910s, most directors around the world were cutting up their dialogue scenes at least a little. Gradually, the tight choreography of the tableau gave way to the easier method of using close-ups to pick out key instants.

The European default seems to have been what Americans called the “scene-insert” method. A long shot (called the “scene”) is interrupted by a cut to some part of it (the “insert”). Then we go back to the orienting view. The cuts are typically straight in and back along the lens axis.

Here’s a straightforward German example from The Devil’s Marionettes (Marionetten des Teufels, 1920). A fake medium has been brought to a rich man’s home to read the fortune of his daughter. As she leaves he pays her, and from his ring she’s able to identify him as a Duke.

Note that the first setup is much farther back than the tableau scenes in Brothers Karamazov and Hilde Warren. There’s not much to be done with such a distant shot except cut in.

The Devil’s Marionettes scene has two inserts, but it’s conservative by American standards. By 1917, Hollywood directors were increasing the number of “inserts” considerably and making them the dominant source of the ongoing action. Some European directors took this option; notable instances are Abel Gance and Victor Sjöström. Others, though, relied on the scene-insert approach, not building the action out of a lot of closer views. The post-1917 German films I’ve seen, most recently and on other occasions, favor a moderate scene-insert approach like the one in Marionettes. Accordingly, the “pure” tableau option waned.

Yet one basic idea of the tableau strategy persisted. We can see this in directors’ use of the axial cut, which provides a constant orientation to the setting. While American directors were often building up a scene from many angles, German directors seemed reluctant to show the action, at least in interior sets, from distinctly varied viewpoints. So when they broke a dialogue scene into many shots, they stuck to the camera axis, cutting in and out along that. You can see that in the Marionettes scene. Consider as well this moment in I.N.R.I.: The Catastrophe of the People (1920). Within a single overall orientation, the editing enlarges or de-enlarges the three characters in the boudoir.

Even with the drastic enlargement from the first shot to the second, or from the third to the fourth, our orientation is basically the same. The staging cooperates with this strategy, making sure that all three players’ faces turn to the camera, even if their bodies are angled away from it. They’re playing to the lens axis, we might say.

When directors try to shift the angle more drastically, the consequences can be strange. In Rose Bernd (1919), an adaptation of a famous Gerhardt Hauptmann play, an axial cut has brought the bullying Streckmann striding toward the camera to meet his wife and Rose, chatting in his garden.

As he flirts with Rose, director Alfred Halm provides another axial cut, from farther back, as a neighbor woman passes in the foreground. Rose turns to look.

The print is missing dialogue titles, but there evidently was one here, as Rose comments on the woman passing. The dialogue title provides some cover for the extraordinary cut to the next shot.

The time is clearly continuous, as the woman is still walking past the garden gate, now in the distance. But Rose, Streckmann, and his wife have been completely rearranged in the frame. They’re positioned frontally, as in the I.N.R.I. boudoir example, and they create the sort of foreground/ background dynamic characteristic of 1910s cinema generally. Halm could have shown Rose’s comment and the others’ reaction by cutting back in along the axis, to a closer shot of the group in the garden (like the second one above). Instead, he shifted his camera position sharply. The new shot does highlight Rose and her gesture, but at the price of spatial coherence.

Aliens, missing shadows, and lustful monks

Tötet nicht Mehr!: Misericordia (To Kill No More!: Misericordia, 1919).

So some of our hypotheses seem borne out. Many German directors apparently adopted a conservative position toward American-style analytical editing until the ban relaxed in 1921. After that, as Kristin documents in her Lubitsch book, films by Murnau, Lang, and others employ more varied angles and less frontal staging. It seems likely that the Germans learned about this approach from the new availability of films from America and European countries (some of which were adopting the American approach).

My latest plunge into Weimar cinema yielded other enjoyments. It’s commonly said, for instance, that Germans experimented with expressive lighting effects. So did directors in many other countries, but I did find some striking uses of sparse, stark illumination. One example is the prison cell from Tötet nicht Mehr!: Misericordia (1919), above. Even more daring is this double close-up from I.N.R.I.

Harvey Dent has nothing on the conniving Russian student Alexei, half of whose face seems just scooped away by shadow. The faint shadow cast on the wall tempts us, in a weird Gestalt illusion, to see his head as partly transparent.

Another area of German expertise was special effects, and I saw plenty of sophisticated double exposures, matte shots, and split-screen tricks. As you’d expect, some of these were used to suggest hallucinations or the supernatural. At the very top of today’s entry is another image from I.N.R.I., which presents the student Dmitri’s fever dream. Below are a couple of nice ones from Lost Shadows (Verlorene Schatten, 1921). A Satanic traveling showman puts on shadow plays, but his cast is drawn from real life: He bargains with people for their shadows, and eventually leaves the hero without one.

What, finally, about what we all yearn for: an extravagantly nutty film? Nothing in this foray matches the work of Robert Reinert (Opium, Nerven), about which I’ve written in Poetics of Cinema and on the DVD restoration of Nerven. Reinert is on another plane of delirium, as mentioned in an earlier entry. Nonetheless, apart from moments in many of those movies already discussed, I found two pervasively peculiar items.

The more well-known is Algol (1920), directed by Hans Werckmeister. The sets, although designed by Walter Reimann of Caligari fame, aren’t cramped and contorted but are instead vast, geometrical, and a bit reminiscent of the Monster-Machine aesthetic of Expressionist theatre.

The plot is your everyday visit from another planet. An alien from Algol visits a coal mine and gives a loutish miner a machine that generates endless energy. (Today the Algolian could take a bribe from an oil company to head back home.) The miner becomes a tycoon controlling the world’s energy supply. This monumental fantasy (big sets, big crowds) is enacted with maniacal gusto by Emil Jannings, who spends his wealth, like all good plutocrats, on bacchanals featuring crazy dancing.

Algol is forthcoming in the Filmmuseum DVD series.

The Plague in Florence (Die Pest in Florenz, 1919) is less famous, although the script is by Fritz Lang. Directed by Otto Rippert (Homunculus, 1916; Totentanz, 1919), this tells of Julia, a woman whose all-powerful sexuality wreaks havoc on the city. Even churchmen lust for her, and eventually Florence sinks into debauchery. What redeems, if that’s the right word, the city is the appearance of a plague that strikes citizens dead in their tracks. Personified as a gaunt woman rising up from the marshes and mournfully playing a violin, the plague eventually kills Julia and her umpteenth lover.

Before this, we’ve had everything I’ve mentioned and more: a couple of fancy tableau sequences, axial cuts, wild mismatches between shots, spectacular lighting effects (e.g., catacombs, below), and hallucinatory sequences. At one point, the mad monk vouchsafes Julia a glimpse of the horrors to come by showing her a river of corpses calmly flowing underground.

Of course the monk isn’t invulnerable to Julia’s charms. Trying to pray away the impulses she arouses in him, he sees her as his Savior. Herr Rippert, Señor Buñuel is on the other line.

Who knew film history could be so surprising? You don’t get this stuff in your usual pop history. But maybe it’s better we don’t share this with the civilians.

My usual heartfelt thanks to the Royal Film Archive of Belgium, its staff (particularly Francis, Bruno, and Vico), and especially its Director, Nicola Mazzanti. Thanks also to Sabine Gross for a translation.

My previous Brussels research visits are chronicled in this blog over the years. A 2007 entry talks about my viewing method and concentrates on Yevgenii Bauer. The following year’s entry is devoted to William S. Hart. An eclectic 2009 one surveys films from Germany, France, Denmark, and even Belgium. In 2010 I went twice, once in January (watching mostly Italian diva films) and as usual in July (but no entry for that visit, consumed as I was with writing about Tintin). The 2011 entry is diverse, covering many national cinemas, and, implausibly, runs even longer than the others.

We have many other entries on film style in the 1910s. One considers how the Hollywood style coalesced in 1917; another talks about Doug Fairbanks. There’s also an entry on 1913, which discusses both Suspense and Ingeborg Holm, and there are discussions of Sjostrom as a master of both the tableau approach and continuity editing. And of course there’s plenty on Feuillade’s staging; you might start here, and perhaps pause over the mini-essay here, which talks about the director’s eventual experiments with editing. Elsewhere on the site there’s an essay on Danish cinema that echoes some points made in today’s entry. (Unlike other countries, neutral Denmark was able to send its films to Germany during the war, so there may have been some influence there.) Broader comparative arguments about this material have been sketched in a lecture I’ve given in various places, “How Motion Pictures Became the Movies.”

Interest in German cinema of the period grew after Pordenone’s Giornate del cinema muto held its trailblazing program published as Before Caligari, ed. Paolo Cherchi Usai and Lorenzo Codelli (University of Wisconsin Press, 1991; now, alas, very rare). See also the valuable collection edited by Thomas Elsaesser, A Second Life: German Cinema’s First Decades (Amsterdam University Press, 1996). Kristin has an essay here on Die Landstrasse (1913), a remarkable instance of the tableau style.

As my research on the 1910s draws to a close, I’m thinking of how to synthesize and present my arguments. Originally I was considering a book, but the number of stills, and the specialized nature of the project, would probably make publishers shudder. At the moment, I’m thinking about creating a series of PowerPoint lectures, with voice-over. These would be freely available for people to use in courses if they wanted. That initiative would be another experiment in using the Web to get information and ideas out there to interested readers.

Professor Bordwell illustrates his views on visual storytelling (Algol).

JCC

The Milky Way (La Voie lactée, 1969)

DB here, writing from a gray Brussels:

All the problems of a film are in the script.

When a film is made, the screenplay disappears.

When you consider what a scene needs to express, ask: How can the actor act it?

When you’re writing a scene, try to act it out yourself.

Rather than letting dialogue explain the action, let the action explain the dialogue.

It will always be possible to make films. Don’t forget to make cinema.

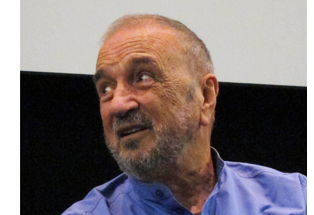

These and other epigrammatic insights flowed easily from Jean-Claude Carrière during his visit to the Cinematek of Belgium and the annual conference of the Screenwriting Research Network. I hope to devote a later blog to other attractions of this stimulating get-together. For now, a brief tribute to the volcanic charm of the legend known as JCC.

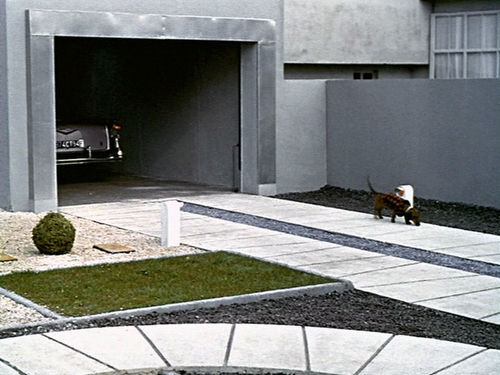

JCC entered cinema under the aegis of Jacques Tati. Tati wanted someone to turn M. Hulot’s Holiday and Mon Oncle into novels, and the very young writer seemed the right candidate. But Tati quickly learned that JCC didn’t know how a film was made. So he assigned Pierre Etaix and the editor Suzan Baron to tutor the lad in the ways of cinema. First lesson: Go through M. Hulot on a flatbed viewer, examining the script line by line while watching shot by shot. As a result, JCC says, he began to understand “the film that you don’t see.”

In the course of his career, JCC has written novels, plays, essays, screenplays, even a scenario for a graphic novel. In the process he became one of the most distinguished and respected screenwriters of the last fifty years. His most famous collaborations were probably with Buñuel, from Belle de Jour (1967) to the master’s last film, That Obscure Object of Desire (1977). He worked with Etaix (The Suitor, 1962), Forman (Taking Off, 1971), Schlöndorff (The Tin Drum, 1979), Godard (Every Man for Himself, 1980), Wajda (Danton, 1983), Oshima (Max mon amour, 1986), Kaufman (The Unbearable Lightness of Being, 1988), Peter Brook (The Mahabarata, 1989), Malle (Milou en Mai, 1990), and Haneke (The White Ribbon, 2007). He has also become known for his work on major French costume pictures and adaptations, such as Cyrano de Bergerac (1990) and The Horseman on the Roof (1995), as well as work with younger directors, including Wayne Wang (Chinese Box, 1997) and Jonathan Glazer (Birth, 2005). His TV scripts are numberless.

Directors both young and old come to him for the unique forms of collaboration that he offers. Instead of going off to write the screenplay, JCC meets frequently with the director. (Sometimes the director stays in his house.) He might ask the director to write the script for him, and they go over the result. Through these methods, JCC tries to help the director “find the film that he wants to make.” But his methods are flexible, tailored to the director’s temperament. When he was working with Buñuel, the men met daily to tell each other their dreams, some of which wound up in The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie (1972). Similarly, JCC prefers to meet with the actors before production, letting them try out the parts so that he can revise things for each one’s habits of speaking. For Cyrano, Depardieu read the entire play aloud, taking all the parts, and then listened to it over and over on cassettes to refine his interpretation.

Brussels gave JCC a busy twenty-four hours. In conversation with the critic Louis Danvers he introduced a Cinematek screening of The Milky Way. He gave a keynote address for the Screenplay Network conference, and he participated in a panel discussion with members of the Flemish Screenwriters Guild at the film school RITS. These sessions ranged freely over his career and his conceptions of filmmaking. He believes that there is a language of film that sets it apart from other arts. That language is grounded in the play of meaning and emotion that comes from putting one shot after another.

He explained the point through an example that seems at first to be a restatement of the classic Kuleshov effect. In Shot 1, a man in his apartment looks out the window. Shot 2: The street. A woman is walking with another man. We’ll assume that our man is seeing them. Shot 3: Our man reacts.

But contrary to Kuleshov’s dictum, his facial expression should not be neutral. In fact, his expression tells us how to understand the scene. If the man looks upset, we surmise that he’s jealous. If he’s benevolent, we assume that the woman is a friend, his daughter—or a flirt. The filmmaker needs not only techniques like framing and cutting, but also the performances of actors.

Now cut to the woman in her bedroom brushing her hair. We need to make sure the audience understands that it’s the same woman, so maybe we have to go back and add a shot to the earlier scene, a closer view of her in the street. This constant flow and readjustment of images is based on guiding the spectator discreetly but firmly through the action. The audience isn’t aware of this “secret film,” but it governs everything the viewer thinks and feels.

For this reason, the young screenwriter needs to learn everything about how a film is made. When JCC was acting in The Wedding Ring (1971), a film starring Anna Karina, he learned that simply getting up from a couch can be a complicated matter. When he stood up spontaneously, dipping forward to lift his body, the cinematographer had to correct him: It looked awkward on film. JCC learned that he had to stand up in an unnatural way, with his feet spaced and his back rigid, so that it looked smooth on film. The screenwriter must know that even the smallest moment of action, easy to write in the comfort of a study or a café, is subject to the contingencies of production.

For this reason, the young screenwriter needs to learn everything about how a film is made. When JCC was acting in The Wedding Ring (1971), a film starring Anna Karina, he learned that simply getting up from a couch can be a complicated matter. When he stood up spontaneously, dipping forward to lift his body, the cinematographer had to correct him: It looked awkward on film. JCC learned that he had to stand up in an unnatural way, with his feet spaced and his back rigid, so that it looked smooth on film. The screenwriter must know that even the smallest moment of action, easy to write in the comfort of a study or a café, is subject to the contingencies of production.

Where to get ideas for films? From the classics, of course. (“Balzac is the greatest screenwriter—every character is vivid.”) But above all you must observe reality. Tati taught JCC to sit vigilantly in a café. Study everyone who passes. Notice details. Imagine the person as a character in a story. Give him or her some motivations. What you must do is “find the fiction in the reality.” When JCC presided over the French film school La FEMIS, he promoted an exercise that required students to move out into a public space, like a market, and come back with stories about the people they saw. JCC praised Tati’s genius for spinning gags and situations out of passing life—“as if God had created the world so that it could furnish a film by Jacques Tati.”

JCC must be one of the few screenwriters who doesn’t gripe about his work being changed in its final incarnation onscreen. He sees the screenplay as ephemeral, the chrysalis for the butterfly. Once you accept the fact that your text must be sloughed off on its way to becoming cinema, you can take joy in your work. For young people, JCC advised the same relaxed, exploratory attitude. Conceive of yourself as a writer, able to move across media. The venues for your writing are constantly changing, so be prepared to write for television as well as film, to write comics and documentaries and plays. Above all, “Don’t despair of the future of cinema. It’s wide open.”

Jean-Claude Carrière turns eighty next week.

The best introduction to Carrière’s career and ideas that I know is his book The Secret Language of Film (Faber, 1995). Some of this text overlaps with Exercice du scénario (FEMIS, 1990), coauthored with Pascal Bonitzer. That book is worth reading too, but it hasn’t to my knowledge found English translation. An illuminating interview is here.

P.S. 11 September 2011: Thanks to Jonathan Rosenbaum for correcting an error in JCC’s filmography, which I’ve rectified above. Jonathan also remarks:

I assume that you know, by the way, that Carrière appears in a scene of Certified Copy, playing something similar to the “wise old guru” role played by the Turkish taxidermist in Taste of Cherry and the doctor in The Wind Will Carry Us.

I did know and should have worked it in!

P.P.S 22 September 2011: A panel discussion with Jean-Claude Carrière held during the conference is available here. Although the site is in Dutch, the discussion is in English. Thanks to Ronald Geerts for the information.

Mon Oncle (1958). “I followed Tati more or less everywhere, usually with Etaix, attending projections followed by long anxious discussions. (‘Can we clearly see the dog’s tail go past the electric eye that shuts the garage door? Yes? Clearly? You’re sure people will see it?’)