Archive for the 'Film technique: Editing' Category

Alignment, allegiance, and murder

House by the River (1950).

DB here:

“Point of view” is one of those terms that we can’t seem to do without, but it’s rather vague. The clearest application of the term would be to shots that conform more or less to what a character sees, presenting what we might call optical point of view.

But sometimes we’re given access to what a character sees, hears, and knows less narrowly. Without any optical pov shots, we might still be restricted to a character’s range of knowledge. This happens in detective films like The Big Sleep, which confines us almost completely to what Philip Marlowe knows. We follow him into scenes, stay with him as the action plays out, and then leave the scene when he does. We’re “with” him, but not via optical point of view.

In his book Engaging Characters, Murray Smith calls this sort of restriction to character knowledge alignment. He points out that it has both objective and subjective sides. Objectively, we’re spatially attached to a character in the course of a scene or several scenes. Subjectively, we may get access to the character’s thoughts, memories, dreams, or immediate perceptions (as with a POV shot). Spatial attachment refers to the limited range of our knowledge; subjective access refers to the depth of knowledge about the character’s inner experience.

But what about our emotional engagement with the characters? We usually call this “identification,” but Smith shows that this is a misleading way to think about what happens. Identification seems to imply taking on another’s state of being, but we don’t necessarily mimic a character’s emotions. We might pity a grieving widow, but she isn’t feeling pity, she’s feeling grief. Smith talks instead of allegiance, the extending of our sympathy and other emotions to characters on the basis of their emotional states. Allegiance, Smith maintains, depends partly on the moral evaluations we make about the character’s actions and personality.

Alignment and allegiance don’t necessarily involve us with only one character in the course of a film. Cases like The Big Sleep, which put us “with” Marlowe all the way through, are rare. Often a filmmaker shifts our alignment and allegiance away from one character to another, perhaps in the course of a single scene. That may involve some careful choices about staging, framing, sound, and cutting.

I offer you an example from Fritz Lang’s marvelously perverse House by the River. I’m afraid I can’t avoid spoilers, but at least I don’t give away the ending.

At the point of a nail file

Stephen Byrne, a struggling but well-to-do writer is married to the lovely Marjorie. But this doesn’t stop him from trying to seduce their maid Emily. While struggling with Emily, Stephen strangles her. With the help of his brother John, he stuffs Emily’s body into a large sack and deposits it in the river. Stephen’s crime has stirred something in him, and he begins writing a new book, Death on the River, with its plot based on what he has done. Meanwhile, an inquest into Emily’s disappearance casts suspicion on John as her killer.

The very end of the inquest scene has shown the prosecutor and chief inspector confronting Stephen, who says he won’t do anything to incriminate his brother. Since neither John nor Marjorie knows of this conversation, we’re aligned with Stephen. He now has precious information: the police are likely to be watching his brother, not him.

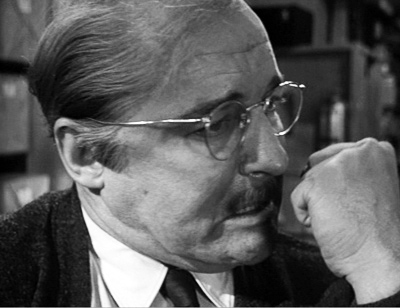

Our alignment with Stephen continues at the start of the next scene, which shows him at work on his manuscript. Marjorie comes in and asks to talk with him about Inspector Sarten.

After a pause to consider, Stephen reluctantly follows her into her bedroom. Lang’s camera, angled along the corridor, puts us strongly with him.

As Stephen enters the bedroom, Lang continues to favor him. Stephen comes into a knees-up shot facing front, but the answering shot of Marjorie weeping at the window is more distant, approximating his optical point of view.

Often filmmakers give us slightly stronger alignment with one character than another by framing one more closely than another. That happens here, I think, for Lang repeats these camera setups several times as Stephen apologies for being snappish and asks Marjorie what she wants to tell him. We know he’s being pleasant only because he wants information.

She comes forward and sits, reporting that she has seen the detective following her. Now we can see her expression more clearly and she is less remote from our concerns.

Again the setups repeat for a bit, with the framings still making Stephen more salient. Aligned with him, and to some extent allied as well, we are able to share his sense that danger is approaching. Stephen comes forward and steps into a more neutral and balanced framing. I’d argue that our sense of being “with” him now begins to taper off.

Marjorie points to the window (in one of Lang’s compositionally accented gestures) and suggests that an officer may be watching the house. Stephen goes to look out.

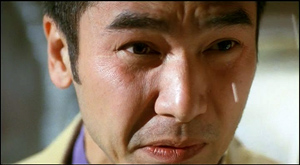

Stephen suggests that the police should be targeting John, since he’s acted suspiciously after the inquest. As Stepehn talks, he saunters to the dressing table and uses the file there to smooth his nails. He suggests that John may very well have had an affair with Emily. Although the framing is in long shot, we can see Stephen’s expression clearly, and it’s duplicated in the mirror. By contrast, when Marjorie rises indignantly and upbraids him, her back is mostly to us.

Stephen sits, remarking, “There’s a limit to this business of being brothers, Marjorie.” She turns slightly, saying, “Stephen, you’re insane.” This line prompts a cut to Stephen, still smoothing his nails but turned from us.

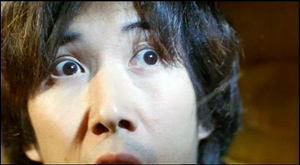

His face turned away and no longer visible in the mirror, Stephen says casually, “You’re very fond of him, aren’t you?” Now we’re more aligned with Marjorie, seeing more or less what she could see. Lang could have staged this phase of the scene to give us more information about Stephen’s expression (say a low-angle depth shot with his face in the foreground), but the opaque shot we get is balanced by a close, clear view of Marjorie for the first time in the scene–another step toward alignment and allegiance with her. The turned-away shot of Stephen also highlights his gesture of filing his nails, important in what will come next.

Cut to a medium shot of Marjorie’s reaction. “You know that.” Back to Stephen: “Are you in love with him?”

Stephen doesn’t see her reaction, which confirms his guess about her feelings for John, but we do. More important, our allegiance shifts toward her too. We know that Stephen is lustful (he’s seeing women in town every night), but Marjorie is suppressing her fondness for John for the sake of her marriage vows. She has the moral edge.

He questions her further, finally turning to her and grinning: “Don’t think I haven’t been aware of it.” Cut back to her: “You have a filthy mind”—something we know to be true. Her moral scheme fits ours, and sympathy for her builds.

This riposte wipes the smile from his face and he walks slowly toward her, the nail file extended like a knife, but also waggling jauntily in his hand. He recovers his flippancy and assures her he doesn’t feel any jealousy toward John because he no longer finds Marjorie attractive.

After he says he finds cheap perfume exciting, she calls him a swine. He resumes filing his nails. Stephen leaves the shot but, crucially, Lang’s camera dwells on Marjorie, glaring after him.

The scene’s final shot shows Stephen strolling down the corridor, and it ends with him smiling and slamming his door. It is a kind of symmetrical reply to the early shot of him going to her room.

This point-of-view shot anchors us with Marjorie, both perceptually and morally. She now realizes that she is the only ally John has.

Marjorie doesn’t know that Stephen is the killer and that John helped him dispose of the body. As often happens in films, we know more than any one character. As a result, we can register suspense when Stephen approaches with the nail file (we know he’s capable of stabbing her), but she evidently doesn’t feel herself in danger. To put it more generally, a string of scenes which restricts us to one character after another gives us a moderately unrestricted knowledge of the overall narrative.

Still, moment by moment, the director can use film technique to weight one character’s reaction more than another’s. We can balance those short-term reactions against our wider compass of knowledge. Our sympathies can shift as we register characters’ changing awareness of their situation, however partial their awareness may be.

Interestingly, the end of this scene, emphasizing Marjorie’s new understanding of Stephen’s turpitude, links to the next scene rather neatly. We see John at home, drinking with grim determination, but when he answers the door he finds Marjorie there.

The segue to Marjorie as a center of consciousness in the bedroom scene prepares for her going to comfort John.

More broadly, the shift initiates a new phase of the film in which Stephen must further cover up his crime. For nearly all of the film’s first half-hour, we’re restricted to Stephen’s ken, when he commits and covers up his crime. After that, the film’s narration alternates between scenes organized around Stephen and ones organized around John, with two brief ones centering on Marjorie. The inquest, at twelve minutes the longest sequence in the film, gathers together all the characters and functions as something of a neutral and objective reset.

That scene is followed by the one I’ve examined, in which we return to Stephen writing a manuscript, as we saw him at the start of the film. The new scene’s narrational weight briefly shifts, as we’ve just seen, from him to Marjorie. After she leaves John’s house, however, the film will build suspense by attaching itself almost wholly to Stephen as he plots to kill both his brother and his wife.

Smith points out throughout his book that alignment and allegiance are complicated matters. It sometimes happens that we have sympathy for the devil–someone who’s acted immorally but whom we might root for to some degree. Bruno in Strangers on a Train is a classic example. And we can think of instances of villains who engender some sympathy because they have some admirable features or because they are treated unfairly.

So I don’t want to leave you with the impression that Lang hasn’t toyed with our allegiances more severely in other stretches of House by the River. At the start, Stephen is at best a bounder, but who doesn’t want him to succeed initially in hiding his crime? (For one thing, if he didn’t try, the story would be over too soon.) And there may be something admirable in his cleverness and bravado as he tries to palm the guilt off on John. My discussion of this scene simply wants to show that the fluctuations of alignment and allegiance can be quite small-scale, and they often depend on niceties of directorial technique.

Craftiness

Artistry depends on craft, and craft is something both cinephile critics and academics have neglected.

Coming across that sentence in a recent essay in Film Comment, you might have a question. What is craft, and how is it different from artistry?

Some thinkers, most famously R. G. Collingwood, saw a sharp line dividing the two. I’m more inclined to see them on a continuum, at least in certain art traditions. In film, I’d suggest that craft consists in fulfilling the task at hand with skill and efficiency.

Craft implies a set of norms, a default or standard that any competent artisan should be able to fulfill. Artistry then, we might say, becomes a plus. It goes beyond the task’s narrow purpose. Ozu’s establishing shots, for example, do more than establish the locale of the upcoming scene. They create intricate plays with compositional motifs that recur through the entire film. Artistry may not necessarily add complexity, though; it can also compress and concentrate. Bresson eliminates establishing shots and providing environmental information through glimpses of background or information on the soundtrack.

Sometimes artistry adds a psychological complexity not apparent in the bare-bones task. This might be given through performance and/or the way the scene is shot. This is what I think happens in the House by the River scene. It’s not a flamboyant job of direction. We need to take a little effort to see how Lang has set up the master shot to allow Stephen to go to the window, then to the dressing-table; and to see how Lang has reserved the closer shots of the couple for a new level of conflict.

But so much might have been done by any solid artisan. And you could imagine other ways to shoot the scene. Someone like Preminger might have presented the entire encounter in a few balanced two-shots. Lang’s extras—the discreet use of optical point of view, the analogous corridor shots, and the subtle variation in shot scale between Stephen and Marjorie, not to mention Stephen’s playful waggling of the nail file—build subtle attitudes toward the characters.

Call it artistry, or cunning craft. Either way, it shows how directors can shape our experience by adjusting the range and depth of our knowledge, sometimes in small but powerful ways.

The distinction between range and depth of information in cinematic narration is presented in Film Art: An Introduction, Chapter 3 and in my Narration in the Fiction Film. For more on these concepts, see Meir Sternberg’s Expositional Modes and Temporal Ordering in Fiction. Murray Smith’s Engaging Characters refines these and other distinctions in order to understand how we grasp character in film.

Tom Gunning’s The Films of Fritz Lang offers a detailed, fascinating commentary on House by the River, concentrating especially on motifs of writing, mirroring, and filth.

For other entries on the craft of staging dialogue scenes, go here and here and here and here elsewhere on this site. For more on niceties of direction, from a director seldom credited with such, try here.

House by the River (1950).

Endurance: Survival lessons from Lumet

I don’t believe in waiting for the masterpiece. Masterful subject matter comes up only rarely. The point is, there’s something to advance your technique in every movie you do.

DB here:

Across half a century he outpaced his contemporaries. He was the last survivor of the vaunted 1950s generation of East-Coast TV-trained directors, men who went over to theatrical films just as the studio system was in decline. John Frankenheimer, Martin Ritt, Richard Lester, and Franklin J. Schaffner won big projects early on, but they also faded faster. As they were moving out of the game in the 1970s and 1980s, Lumet was getting his second wind. He ground movies out–good, so-so, or wretched–like a contract director of the studio days. Sometimes he had a strong stretch, as in the early 1980s, and sometimes not. He started in his early thirties with Jean Vigo’s cameraman Boris Kaufman, shooting crystalline black and white. At the end he was making a feature in high-definition video.

When Lumet died on 9 April, journalists were generous in their praise. But most of the eulogies seemed to me constraining. They overlooked his complicated role in postwar American film, and they neglected to supply the sort of historical context that make even his negligible films of interest. Concentrating on his official masterpieces (Dog Day Afternoon, Network), the obituaries cast him as a hard-nosed urban realist. That’s part of the story, but if we want a fuller picture of this long-distance runner, we need to trace his path in more detail. That in turn can teach us something about shifting generational opportunities in American cinema.

We can start by noting what the recent accolades seem to have forgotten: at the start of his career Lumet faced brutal hostility from the critical intelligentsia that ruled his home town.

Danger man

The Pawnbroker.

Reading 1960s film criticism, you might think that Sidney Lumet was the biggest threat to film art since the Hays Code. Young cinephiles today may be unaware of the vituperation that New York’s highbrow critics showered on him at the start of his career.

John Simon: “What is Lumet good at? Intentions, underlining, and casting.”

Manny Farber: “Giganticism is, of course, the main Lumet contribution [to The Group]. . . . Miss [Shirley] Knight, in a concentrated post-coitus scene atop [Hal] Holbrook’s chest, has a head the size of a watermelon.”

Andrew Sarris: “The Pawnbroker is a pretentious parable that manages to shrivel into drivel.”

Most tireless was Pauline Kael, who throughout the decades picked off nearly every Lumet movie with the casual contempt of Annie Oakley shooting skeet. From the backhanded compliment (“The Pawnbroker is a terrible movie and yet I’m glad I saw it”) to the eviscerating dismissal (Deathtrap is “an ugly play and what appears to be a vile vision of life”), Kael did not relent. She found Lumet’s staging “slovenly,” his color schemes inept; in Serpico “scene after ragged scene cried out for retakes.”

The hunt was in full cry in Kael’s 1968 essay, “The Making of The Group,” one of those behind-the-scenes journalistic forays that always end in tears for the production. Every such think-piece mysteriously assures the film’s commercial failure, while guaranteeing that posterity will remember each participant as a knave or a fool. Yet for sheer bloodthirstiness, Kael’s reportage easily surpasses that of her predecessor Lillian Ross in Picture.

Kael is out to show that the conditions of acquiring, producing, and marketing films have become almost utterly corrupt. No artist can survive the system. So she starts by establishing Lumet as merely a journeyman, shooting the script as a straightforward job of work.

But then things get rough. He is, for one thing, a poor craftsman.

He cannot use crowds or details to convey the illusion of life. His backgrounds are always just an empty space; he doesn’t even know how to make the principals stand out of a crowd . . . . Lumet is prodigal with bad ideas . . . . He will take the easiest way to get a powerful effect; in some conventional, terribly obvious way he will be “daring” . . . The emphasis on immediate results may explain the almost total absence of nuance, subtlety, and even rhythmic and structural development in his work. . . . I was torn between detesting his fundamental tastelessness and opportunism and recognizing that at some level it all works. . . . Because Lumet can believe in coarse effects he can bring them off.

He is also a severely deficient human specimen.

[He was] the driving little guy who talked himself into jobs . . . He seems to have no intellectual curiosity of a more generalized or objective nature . . . For Lumet, a woman shouldn’t have any problems a real man can’t take care of . . . . He’ll go on faking it, I think, using the abilities he has to cover up what he doesn’t know.

Kael has her generous moments, praising Long Day’s Journey into Night (1962), chiefly because of the performers, and in later years she would admire scenes in Dog Day Afternoon (1975). But usually her admiration boomerangs into a complaint (Lumet yields a fast pace, but that makes him slapdash). On the whole she and her Manhattan peers, who seldom agreed on anything, conceived Lumet as dangerous.

Why? Partly because they mostly set themselves against the middlebrow culture of the newspapers and newsweeklies. Many of Lumet’s early films were admired by staid critics. Praise from these quarters was anathema to the sophisticates. Somebody had to tell the Times’ Bosley Crowther that The Pawnbroker (1965) was not “a powerful and stinging exposition of the need for man to continue his commitment to society.”

Another strike against Lumet was his pedigree. He was said to have brought TV technique, simultaneously bland and aggressive, to theatrical cinema. Early live TV drama, confined by the home screen’s 21-inch format and weak resolution and hamstrung by punishing shooting schedules, pushed directors to rely on flatly staged mid-range shots, goosed up with close-ups, fast cutting, and meaningless camera movements.

Kael suggests that Frankenheimer, a common foil to Lumet at the period, managed in films like The Manchurian Candidate (1962) to convert the TV look into “a new kind of movie style,” though she never explains what that consists of. By contrast, Lumet simply followed the line of least resistance, emptying out his shots and “hammering some simple points home.”

There’s nothing on the screen for your eye to linger on, no distance, no action in the background, no sense of life or landscape mingling with the foreground action. It’s all there in the foreground, put there for you to grasp at once.

The TV style threatened to suffocate the glories of cinema: the full view, a more leisurely unfolding of action, a sense of life flickering on the edges of the plot. For Kael the TV-trained Lumet exemplifies the loss of the great tradition of artistic moviemaking personified in Jean Renoir.

Lumet was dangerous in another way. He seemed part of a trend toward heavy-handed showoffishness. Partly the trend was seen in the sweaty strain of Method acting, typified in Kazan’s work. Manny Farber proposed that the Method was at the center of the “New York film,” a fake realist package predicated on psychodrama, arty compositions, and liberal pieties. 12 Angry Men was “counterfeit moviemaking,” filled with “schmaltzy anger and soft-center ‘liberalism.’” Hard-sell cinema, Farber called it. Dwight Macdonald saw the same bludgeoning in The Fugitive Kind.

Lumet’s direction is meaninglessly over-intense; lights and shadow play over the close-up faces underlining lines that are themselves in bold capitals; every situation is given end-of-the-world treatment.

The new tendency toward self-conscious artifice didn’t just have New York roots. The French New Wave’s somewhat disjunctive cutting, unexpected camera movements, freeze-frames, and other flagrant techniques made audiences and filmmakers aware of film style to a new degree. Tony Richardson, John Schlesinger, and other directors scavenged these devices to give their films an up-to-date panache. Once more a critic needed to invent a new label for Lumet: Macdonald claimed that he was an exponent of the Bad Good Movie, “the movie that is directed up to the hilt, avant-garde wise,” in the vein of Mickey One, The Servant, The Trial, and the work of Godard. The Pawnbroker’s fragmentary flashbacks led Sarris to call it Harlem mon amour.

Harsh as they are, these comments do have a point. The early films shout and scream a lot, both dramatically and pictorially. Lumet admitted his love of melodrama, conceiving it not simply as overplaying but rather as conflict at the highest pitch of arousal: extreme personalities in extreme situations. So a silence is usually prelude to an outburst, and a bellow or a slap is never far off. The jury deliberations in 12 Angry Men (1957) become a group therapy session (or an Actors Studio class?) in which bigots must confess their traumas.

Stage Struck (1958) and The Group (1966) are pictorially innocuous, perhaps partly because they were shot in color, but The Fugitive Kind (1960) is a banquet of elaborate lighting effects whipped up by Kaufman. Macdonald wasn’t fair in his dismissal; the film is dominated by medium and long shots, with close-ups held in reserve for big moments, and the line readings don’t seem to me as overbearing as he suggests. Still, there is a sense of pressure, with very precise reframings and sets densely packed (mirrors, curtains, staircase railings) in a way that accords well with Williams’ overripe dialogue. There is an upside-down shot, and at some moments, as Macdonald notes, the illumination lifts or drops in magical ways—a surprise gift, Lumet claims, from Kaufman.

As a pluralist, Lumet would stage some scenes in full shots and long takes, sometimes at a surprising distance from the camera. But it was hard not to notice the other extreme. His most famous black-and-white films mixed in tight close-ups, oppressive sets, wide-angle distortions, and chiaroscuro. 12 Angry Men is relatively subdued in this regard, building toward more looming images at the climax, with some powerfully jammed ensemble frames.

Fail-Safe (1964) surrenders itself to flamboyant shot design once we get into the war room and then into the President’s sealed chamber. Contra Kael, as in 12 Angry Men, many of these shots have busy backgrounds, albeit not of the Renoirian sort.

The Pawnbroker (1965) is Lumet’s most famous orgy of strident technique, with Sol Nazerman nearly as caged at his counter window as he was in the camps. Even more overwrought is The Hill (1965) in which short lenses pump officers’ raging faces into gargoyle shapes, with pores and welts and gobs of sweat thrust under our noses.

In sum, this is not the director eulogized in Entertainment Weekly: “He never tried to dazzle audiences with flash and style.”

What critics didn’t note, however, was that the more outré look cultivated by Lumet, Frankenheimer, Ritt, and company fitted fairly snugly into 1950s Hollywood black-and-white dramatic style. The blaring deep-focus and violent close-ups exploited by the TV-born directors were already visible in the work of Mann (The Tall Target, 1951, below), Aldrich (Attack! 1956, below), Fuller, and many other directors.

During the 1950s what we might call roughly the “post-Welles” look was well-established for serious subjects and genre pictures alike. The Hill pushes things a bit, as Frankenheimer did in Seconds (1966), but the cramped, low-angle style on display in Lumet’s early work is part of a tradition that goes back years (and which had its echoes in many overseas directors, such as Bergman and Fellini). The wilder reaches of that style, it now seems clear, belonged to Fuller and company, not to mention the Kubrick of Strangelove and the Welles of Touch of Evil. Like Richardson, Schlesinger, and others, the TV émigrés may have gotten their wrists slapped for trying to map onto prestigious social-message movies the visual pyrotechnics already acceptable for program pictures.

Not incidentally, some directors had already found the wide-angle deep-focus look useful in their TV productions. Below are frames from Requiem for a Heavyweight (directed by Ralph Nelson, Playhouse 90, 1956); The Defender (directed by Robert Mulligan, Westinghouse Studio One, 1957); and Lumet’s own omnibus program Three Plays by Tennessee Williams (Kraft Television Theatre, 1958).

You can argue that their move to cinema actually smoothed out the directors’ style. The less square frame and bigger scale of the theatre screen made films like Frankenheimer’s debut The Young Stranger (1957) more spacious and relaxed than what could be seen on the box. 12 Angry Men was a polished effort, starting with an elaborately staged six-minute crane shot assembling the cast in the jury room, and using the width of the screen to enclose several faces. Looking back, we can see that Lumet offered something quite close to then-current Hollywood norms, and it looked less crude than what would be found on live TV of the period.

Still, The Pawnbroker and other films can be credited (or blamed) with helping spread the in-your-face style that would come to dominate American cinema of the next fifty years: disjunctive editing, slow motion, the arcing tracking shot (The Group), handheld shooting for moments of violence or anguish, glum color schemes (preflashing for The Deadly Affair), the teasing flashbacks that will be gradually filled in. Lumet’s early films are anthologies of most of today’s tics and tricks.

Yet by the time of his death, the director who was once feared as the vanguard of something new and awful had come to embody something old and trustworthy. Somehow the unambitious journeyman and pretentious copycat became a “classicist.”

How did that happen?

A prince of the city

Before the Devil Know You’re Dead.

Instead of indicating that he was joining or extending a tradition, Lumet reacted to the hailstorm of criticisms with surprising equanimity, at least in the interviews he gave so abundantly throughout his career. He was modest, acknowledging that many of his films turned out to be feeble, and he declared himself a learner. He tried different projects, he said, to improve himself. He wanted to learn to manage color, to work in different genres (e.g., the dark comedy Bye Bye Braverman, 1968), eventually to fall in love with digital video capture. To some extent Lumet changed because he really wanted to learn more and explore various sides of moviemaking.

Lumet always claimed that he didn’t apply a personal style to his projects; he tried to find the best way to handle the script. He thereby confessed himself to be what auteur critics of the 1960s were calling a “metteur-en-scène,” the director who judiciously enhances the material rather than transforming it to suit his personality. This was probably a good survival strategy in the new churn of the 1970s.

The mid-1970s was the Great Barrier Reef of American cinema. Virtually no members of Hollywood’s accumulated older generations, from Hitchcock and Hawks through the 1940s debutantes (Wilder, Dmytryk, Fuller, Siegel) and the 1950s tough guys (Aldrich, Brooks) to the TV émigrés, made it through to 1980. Many careers just petered out. The future belonged to the youngsters, the so-called Movie Brats. In this unfriendly milieu, Lumet fared better than most. He tried a semifarcical heist film (The Anderson Tapes, 1971) that mocked the rise of the surveillance society, with everybody wiretapping and taping and videoing everybody else. He mounted a classic mystery (Murder on the Orient Express, 1974), a musical (The Wiz, 1978), and a free-love romance (Lovin’ Molly, 1974). Of the items I’ve seen from these years, the most daring is The Offence (1972). This study of a sadistic British police inspector’s vendetta against a child molester offers a sort of seedy expressionism. In another gesture toward psychodrama, long conversations with the perpetrator reveal that the copper is a bit of a perv himself.

Lumet’s most successful rebranding took place in a sidelong return to the Pawnbroker milieu: low-end, location-shot, crime-tinged social commentary using New York theatre talent. Filming in color and casting off the baroque precision of the earlier work, he made his compositions more casual and his shot changes less precise. His cutting pace picked up: six seconds on average for Serpico (1973), five for Dog Day Afternoon (1975), both courtesy of the high priestess of the quick cut, Dede Allen. The driving tempo of these movies gave them an urgency that critics could tie to the ticking-clock plots, the atmosphere of urban pressure, and of course the extroverted acting of Al Pacino.

With the two crime films, and the satiric Chayefsky talkfest Network, Lumet remade his image. He was a New York filmmaker, offering raucous, hard-nosed, semi-cynical takes on corruption in the police, the justice system, politics, and the media. His protagonists tended to be Jews, Italians, and Irish, all working stiffs or bare-knuckle power brokers; and the enemy, again and again, turned out to be the Ivy elite. A tailor-suited WASP, male or female, was likely to sell you out. Only ethnic minorities knew the real score. The line could come from almost any mid-career Lumet film: “I know the law. The law doesn’t know the streets.”

The crowning achievement in this vein, for critics if not for audiences, was Prince of the City, a sprawling study of a cop’s patient years of taping and informing on his corrupt colleagues. More slowly paced than the earlier urban dramas, the film also marked Lumet’s move toward something else again. The style was drier and more sober, almost passive, emphasizing static and somewhat distant setups; the cutting slowed down to nearly nine seconds on average. As mid-period Lumet had blotted out the early years, now something more calm, even comparatively austere, came into view.

Whatever the project, however, by the later 1980s he was offering his own alternative to the fast-cut, whirlicam style that was bewitching young filmmakers. While directors in all genres were building scenes out of endless choker close-ups and cutting every four or five seconds, Lumet applied the brakes, lingering on two-shots, letting whole scenes play out in full frame, moving his actors around and ordaining a cutting pace close to ten seconds on average. The first eight minutes of The Verdict (1982) consist almost entirely of long shots and extreme long shots. The protracted takes and antic bodily contortions of Deathtrap might have come from a French boulevard farce; the first tight single of Christopher Reeves is delayed for half an hour. In an age in which critics decried the choppy confusion of tentpole action, the plainness on display in movies like Running on Empty (1988) and Night Falls on Manhattan (1997) looked anachronistic. Right to the end, Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead (2007) could spare a lengthy and distant shot to register a high-end drug boutique and shooting gallery. We had come from the Hysterical Lumet by way of the Gritty Lumet to the Restrained Lumet.

Acting in the frame

Yet he did not milk the urban crime vein dry. He continued to try a wide range of projects, even probing the Red Scare in Daniel (1983). The rationale was chiefly performance. Lumet was an “actor’s director.” He demanded at least two weeks of rehearsals, which included not only table readings but eventually full blocking of scenes, including fights and chases. Derived from his TV and theatre days, the method suited his belief that actors needed a firm structure in order to invent their characters. Interestingly, this actors-first rationale can be adjusted to any phase of the rough stylistic development I’ve plotted. The high-pressure facial shots of the early films can highlight the minutiae of the performances. But so can mid-shots that let actors build in bits of business.

Manny Farber praised the moment when Fonda in 12 Angry Men dries his fingers at length, one by one. It shows, Farber says, “the jury’s one sensitive, thoughtful figure to be unusually prissy” and provides a “mild debunking of the hero.” But it’s not the unintegrated detail Farber claims; Fonda’s coldness is set up early in the film, when he stands remotely from his peers and shows no interest in them as men. And Fonda was always a master of finger-work, which Lumet could exploit in fastidious framings. In Fail-Safe as the President tries to halt the bombers rushing toward the USSR, Fonda projects the man’s minutely controlled apprehensions by pausing to rub his fingertips together, off in the corner of the shot.

This micro-gesture suddenly leaps, as Eisenstein might say, into a new quality: a worried facial expression.

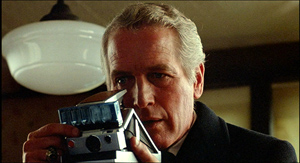

More explicit is the characterizing moment in The Verdict when Frank Galvin (Paul Newman) starts his day with a sugar donut and a full glass of whiskey. The setup is concise: He has crossed off the wakes he’s visited, and his palsied hand can’t pick up the glass without spilling some.

So Frank checks to see if anyone is looking before, like a dog, he bends his head to slurp off a little.

It’s a simple but powerful image of degradation, far removed from the trembling mouth and bulging brows of Steiger in The Pawnbroker.

Lumet cared as much for camera technique as for acting maneuvers. His book Making Movies provides a virtual manual of movie style as draftboard engineering. His gearhead side was probably another legacy of the buccaneering days of live TV and the New-Wave inspired awareness of artifice. He took inordinate pride in his “lens plots” and lighting arcs, charting purely technical changes that would weave their way through the film. (In this he was ahead of his time; now most filmmakers develop these technique arcs, or at least they say they do.) Despite this almost mechanical conception of technique, though, late Lumet rediscovered a bare-bones simplicity of performance and framing that was willing to risk looking flat. In Daniel, he lets the angry young man whose sister has wasted away into madness confront the poster agitating for their dead parents. No tracking in, no circumnambulating camera, no heightened cuts or nudging score. And no need to see Daniel’s face. Susan merely lifts her head.

It’s as if the visual rodomontade of the Movie Brats drove Lumet toward a new sobriety. When Galvin is preparing to try the case of the girl left in a coma through medical malpractice, he visits the hospital and takes Polaroids of her inert body. The slowly developing images not only give us the fullest view of the girl we’ve had so far. They also come to suggest his dawning realization that this is more than just a chance for big money.

Galvin starts to grasp that letting the hospital settle out of court will allow the officials to write off their mistake. There is a human cost to simply getting the check. If he does it, he will now be a better-paid ambulance chaser. Yet he doesn’t stand valiant for truth; the drunk is scared, drained of dignity, and he clutches his portfolio as a sad, ineffectual shield.

Offered the money, Frank takes out the photos and weighs them against the check. Then with a sigh of exhaustion, contemplating the fool’s crusade he’s launching, he returns the check and drops the pictures into his bag.

Very simple visual storytelling; it might have come from a 1930s movie. But this stark presentation of moral decision, given as a straightforward framing of a man’s body, achieves a measure of artistic nobility in a year that gave us Porky’s and Rocky III.

Telling it all, holding some back

Prince of the City.

It’s good to remember such moments of pictorial storytelling because Lumet’s films, especially the early ones, tend to be gabfests. If Eugene O’Neill, Tennessee Williams, and Paddy Chayefsky, along with the Method acting tradition, are your coordinates, you will be drawn to chatterboxes and blowhards. Lumet loved the spoken word, which was after all the mainstay of live TV (“illustrated radio,” it was sometimes called). It’s not clear that he ever shook the habit. His characters usually step onstage leaking exposition, announcing their pasts, their personalities, their plans, and their deepest feelings. This has the advantage of making plot premises clear, but it reduces the figures’ mystery and their ability to surprise us, or to complicate our feelings about them.

Sometimes Lumet did let story construction do heavier lifting. It happens in The Pawnbroker, because the nearly catatonic Nazerman speaks so little that the fusillade of flashbacks provides his backstory. More daringly, the large-scale back-and-fill of The Offence, peppered with small memories but also looping around the central incident in the interrogation room, seeks to reveal Sergeant Johnson’s affinities with the suspected child murderer. We need to remember Lumet’s early fondness for time-shifting plots before we declare Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead an old guy’s effort to catch up with Pulp Fiction.

Even without benefit of broken timelines, Lumet could occasionally hold back information to reshape our first impressions. Take the central revelation of Dog Day Afternoon, when cuddly Al Pacino reveals that his “wife” is not the woman he’s married to (a nice plot feint here) but the man whom he loves. This apparently sensationalistic twist comes early enough to modulate into pathos when Pacino’s character dictates his two wills.

Prince of the City realigns our sympathies in a more intricate way. At the start, Danny is presented as a tormented soul. We’re led to think that he turns snitch because of things we see: the invitation to go undercover, his brother’s and father’s angry concern that his pals are crooked, and above all the shameful efforts he makes to get drugs for his informant. Once he turns, however, he can’t limit the investigation, and at nearly the end his treachery has broken the most important ties in his life.

But “nearly the end” is the operative term, because Prince of the City boldly appends a ten-minute epilogue showing Danny being investigated himself. The Danny we saw at the film’s beginning may have been steeped in corruption; the drug bust we saw included, behind the scenes, a major ripoff of money; he has lied more than we realized; and it seems likely that he cheated on his wife with the prostitutes whom he supplied with drugs.

A modern filmmaker, or Lumet in his bodacious early mode, might have spiced these flat testimony scenes with lurid flashbacks. But sticking simply to Danny’s feeble, evasive stonewalling raises questions of his own vulnerability. Having watched him break down over years and having heroicized his suffering to a considerable degree, we have to judge him anew. Is he simply too weary to fight the charges, or has he been caught out? The ending might seem to allow for cynicism, but we can’t cast off our respect for what Danny has risked.

Further, Lumet intercuts the court scenes with government meetings about whether to prosecute Danny. In the manner of a Shavian problem play, this tactic obliges our sympathies to be clear-eyed. If The Verdict lays all its cards on the table and invites straightforward sympathy for Galvin, Prince of the City, by hiding major aspects of Danny’s character and circumstance, leads us to a more nuanced experience. The narrational dynamic of the film invites us to rethink our protagonist’s actions and decide whether to grant him mercy.

In the vanguard of a new style in the 1960s, Lumet remade himself as part of the 70s renaissance. That freed him to cover nearly every bet on the board, and some paid off. As hotshot younger directors sped past him into tentpole territory, he put the independent sector to use–financing through presales, working with stars on the way down and on the way up, releasing the films through boutique distributors, trying many options with a stubborn pragmatism. He handled failure, ignoral, and disdain better than probably any of us could. “Though his films are invariably flawed,” wrote Sarris in 1968, “the very variety of the challenges constitutes a sort of entertainment.” This zigzag career trajectory provides a unique, even heartening EKG of success and survival in the modern American film industry.

At the same time, he helped make audiences and critics more conscious of film technique, in ways both salutary and damaging. He was part of my film school: The very first movie I saw in a theatre during my freshman year of college was The Pawnbroker, and I revisited it several times. Here was a modern instance of “pure cinema,” worth comparing with A Hard Day’s Night and 8 1/2. (Yes, I hadn’t seen much.) Prince of the City has drawn me since I first saw it in a moldy two-screener in Florida and thought: “Can Hollywood have made a Brechtian film?” I leave for another time the tale of watching Prince in a nearly empty screening sponsored by Nick Cave.

You can probably tell that Lumet is not my favorite filmmaker. Several of his movies I earnestly hope never to see again, and even the ones I admire contain moments I would wish otherwise. But he has given me unique pleasures and prodded me to ask some questions that intrigue me. More broadly, I can’t understand the failures and accomplishments of modern American film without taking into account this marathon man.

For this entry, I haven’t managed to see or re-see as much of the Lumet output as I’d hoped, but the twenty-three films I revisited include his most famous titles (except for The Wiz, which might better be called infamous). My comments here supplement those I make about Lumet and his generation in The Way Hollywood Tells It, 145-147.

I’ve drawn my critics’ quotations from anthologies of their writings. The one I should probably signal explicitly is Pauline Kael’s “The Making of The Group,” in Kiss Kiss Bang Bang (Little, Brown, 1968). The piece is dated 1966, but I can’t prove that it was actually published then. I find it endlessly interesting, not least because it may help us trace some origins of critical clichés. I’m thinking not only of the art/ business dyad but also the appeal to Renoir as the prototype of the spontaneous film creator. Ironically, for at least some projects we have evidence that Renoir rehearsed his actors quite a bit and retook scenes until he was satisfied. Double irony: Somewhat before Kael was celebrating the careless grace of Renoirian spontaneity, he had in Testament of Dr. Cordelier (1959) turned to a multicamera technique for his own television project. Renoir and Lumet intersect in unexpected ways!

On live TV shooting methods, a succinct overview can be found in Erik Barnouw, Tube of Plenty (Oxford, 1975), 160-166, and of course Gilbert Seldes’ Writing for Television (Doubleday, 1952), which I’ve praised elsewhere on this site. Seldes scatters some intriguing comments on live TV drama through his The Public Arts (Simon and Schuster, 1956). Just as important, Criterion continues to serve film studies by releasing precious documents from early television. Watch the items included in The Golden Age of Television and the three Lumet/ Williams playlets folded into Criterion’s Fugitive Kind box to see what these directors were up against, and with what relief they must have greeted the wider choices available on film.

The indispensable sources on Lumet are the fine collection Sidney Lumet Interviews, ed. Joanna E. Rapf. It’s here that Gavin Smith can be found sketching a case for Lumet as continuing classic Hollywood while also pressing into “80’s modernism” (132). And of course everyone must read Lumet’s own Making Movies. On editing The Pawnbroker, see Ralph Rosenblum and Robert Karen, When the Shooting Stops… The Cutting Begins: A Film Editor’s Story (Penguin, 1975), 145-166. Glenn Kenny has an excellent 2007 interview with Lumet on digital techniques in the DGA Quarterly.

Credits: Stage Struck; Night Falls on Manhattan.

Time piece

Christian Marclay, The Clock (2010).

DB here:

Normally I wouldn’t comment on a movie after seeing only 10.4 % of it, but there are always exceptions. The Clock, which played at the Paula Cooper Gallery during our stay in Manhattan, runs 24 hours. It’s a compilation of over 3000 film clips, mostly from Hollywood but also from Europe and Asia. Some of the footage is easily recognized, but a lot of it I couldn’t identify.

The premise, or gimmick, is that every snippet of a scene is purportedly connected in some way to the passing of time measured on a clock. Characters check their watches, or the camera shows a wall clock or digital alarm clock or countdown device. There are tiny clocks and gigantic ones. If the whole thing has a star, it might be Big Ben, who reappears surprisingly often.

A nice idea, but why stretch it over twenty-four hours? So that the creator Christian Marclay can assemble scenes that synchronize perfectly with the passage of time in projection. A shot shows a watch at 11:55 AM; you look at your watch; it’s 11:55 AM. Wherever the piece is screened, it must start precisely at the corresponding local time. The Clock isn’t just about clocks; it is a clock.

The project teases you into lame puns, which I’ve been unable to resist. But my visits set me thinking about what makes The Clock unique and pleasant. Maybe it’s a little too pleasant.

Collage without closure

The Black Cannon Incident (1986).

In its collage of compiled material, what The Clock does is quite familiar to cinephiles. For a long time, experimental filmmakers have built works out of footage from mainstream movies. One of the most famous, Joseph Cornell’s Rose Hobart (1935), powerfully illustrates how the collage principle can pry images from their narrative context and call attention to their poetic or graphic qualities. The assemblage artist Bruce Conner did something similar in A Movie (1958), which creates anassociational form out of newsreels and old Hollywood sequences. Although both Rose Hobart and A Movie still evoke vague narrative expectations, Craig Baldwin whipped together found footage to create a hallucinatory narrative in Tribulation 99: Alien Anomalies under America (1991). An urgent, hard-bitten voice-over tells of CIA conspiracies and interplanetary conquest while we see images scavenged from cheap science-fiction films.

Nowadays plenty of filmmakers, especially on the Web, have snipped footage from old films to develop a theme. Jim Emerson has done it with close-ups, and Matt Zoller Seitz, Aaron Aridillas, and Steven Santos have created a video essay around guns in American film. Last summer, at the new facility of the Cinematek in Brussels, I found thematic loops running on their video monitors. Sometimes there was an interplay among them, so that characters one screen seemed to be looking at those in another. Some of the Cinematek loops in fact centered on clocks.

So the principle of compilation collage didn’t seem new to me. But Marclay refreshes it by the other central premise of The Clock: its time structure, which syncs moments indicated onscreen with moments of viewing.

Some fiction films (e.g., Cleo from 5 to 7, Nick of Time) and TV shows (e.g., 24) have played with the conceit of making the duration of the piece (“real time”) correspond to the amount of time covered in the plot. (Usually, however, the film fudges it.) But in The Clock, there’s no overarching plot, so the duration of that action can’t be determined. Marclay gives us real time with a vengeance, in the relentless correspondence between screen clocks and audience clocks.

Without this exact synchronization, The Clock would be an enjoyable but unexceptional found-footage movie. The onscreen clocks check the flow of the images like centers of magnetic force. They form nodes around which each set of shots revolves, like a musical key that a melody can drift from and return to.

This patterning too has parallels in the experimental film tradition, I think. What P. Adams Sitney famously called Structural film was a 1960s-1970s trend that often built the awareness of time into a film’s overall pattern. A simple example is Robert Nelson’s Bleu Shut (1970). A clock runs in the right corner of the frame to measure the time consumed by a film that is, we’re promised by a woman’s breathless voice-over, “exactly thirty minutes long.” (She lies.)

This patterning too has parallels in the experimental film tradition, I think. What P. Adams Sitney famously called Structural film was a 1960s-1970s trend that often built the awareness of time into a film’s overall pattern. A simple example is Robert Nelson’s Bleu Shut (1970). A clock runs in the right corner of the frame to measure the time consumed by a film that is, we’re promised by a woman’s breathless voice-over, “exactly thirty minutes long.” (She lies.)

A less explicit instance is Hollis Frampton’s Zorns Lemma (1970). In its central section, one by one a string of images replaces one-second shots of signs marking the letters of the Latin alphabet. The shot-changes set up a steady beat, and the pattern locks in a sense of momentum. Although we’re surprised by what images replace the letters, our expectations get focused on the inevitability of all the alphabet shots being deleted. There’s no literal clock, but we can sense this event slowly fulfilling itself. In addition, some of the replacement images show processes moving toward completion, such as dried beans steadily filling up a container. I’m tempted to say that in many Structural films, an actual or tacit clock tracing the film’s movement toward closure becomes a sort of non-narrative equivalent of a deadline in a storytelling movie.

The Clock doesn’t provide exactly that sense of closure, since it has no end point. It’s on a loop and, like a real clock, can be reset according to the time zone of the venue. But the nodal clock images make us aware of the film’s relentless unfolding, and its sync principle has affinities with the Structural tradition’s commitment to a precise time-based architecture. That tradition had its own sources, of course, including the experiments of the Fluxus movement, a trend that also influenced Marclay.

Top-down time

Tracing parallels shouldn’t lead us away from the unique qualities that make The Clock so appealing. For one thing, the fact that there isn’t a continually running readout, as in Bleu Shut or in an iPod slider, enables the film to test our feeling for passing time. Not every shot shows a clock; indeed, most shots in the portions I saw don’t. As we get captivated by clock-less images and follow their development within a scene, the arrival of a timepiece reminds us of the structuring principle. The appearance of a clock creates something like a punchline, while also letting us realize how loose our sense of duration in a movie usually is.

This test-like quality of the film, an important aspect of Structural film that Sitney points out, is reinforced by Marclay’s central idea. We are primed to scan the shots for clocks. Indeed, the search for the clock can reshift our sense of what is important about the scene. In an earlier entry, I discussed how Alfred Yarbus’ experiments in tracking eye movements assigned people tasks, such as estimating the social status of people in a painting. This created “top-down,” concept-driven search behavior. The Clock does the same thing, with the only explicit instruction being the title and our background knowledge of the piece’s procedures.

The result of our top-down search that we pay attention to clocks in the corners of shots or out of focus in the background, in scenes in which time isn’t really at stake. Normally we probably wouldn’t notice these items, but spotting them gives us a reward and allows us to admire Marclay’s cleverness. Some scenes seem to lack clocks altogether, but that doesn’t make them filler; a stretch of clockless footage only sharpens the fun when one shows up.

With shots pried free of narrative demands, you start to discriminate details, like the designs of numerals and brand identities. As you see the names Bulova, GE, Tissot, Hamilton Beach, and all the rest, you realize that it isn’t only James Bond films that use watches for product placement.

I’ve said that the film isn’t narrative in the same way that Craig Baldwin’s fantasy collages are. Yet it does tease us with some narrative expectations. If you recognize the footage, then you can summon up your memory of the story. If you don’t recognize the footage, you might still recognize the generic situation (investigation, pursuit, lovers’ confrontation, awakening in the morning). And the whole shebang does get you thinking about the role of time in narrative.

In this regard, the film makes an almost didactic point: Stories, at least those we’ve become used to, need clocks. They set the story world in motion, they measure its changes, and above all they provide deadlines that generate suspense, surprise, and satisfaction. The Clock makes deadlines especially apparent as we approach noon, when we get not only images from High Noon but also a flurry of other 12:00 PM shots (Titanic, for one). Noon is a really important moment in Central Standard Movie Time. I didn’t see the midnight stretch of The Clock, but I bet it’s a hell of a show.

Perfect timing

Like the compilation filmmakers, Marclay wants crosstalk among his bits, but the stretches of The Clock I saw don’t create much friction. There’s a lot of continuity from shot to shot: One character in one movie walks out a door, and we cut to another character from another movie entering a new locale. Music links scenes smoothly. Although Marclay was influenced by the diffuse, chance organizations promoted by John Cage, some of his earlier work emphasized through-line linkages and blending as well. Marclay’s famous record-album collages allow a unified figure to emerge as a gestalt binding together disparate images. On the right, you can see this happening in Guitar Neck (1992), which virtually diagrams the sort of smooth juxtapositions we get in The Clock.

Like the compilation filmmakers, Marclay wants crosstalk among his bits, but the stretches of The Clock I saw don’t create much friction. There’s a lot of continuity from shot to shot: One character in one movie walks out a door, and we cut to another character from another movie entering a new locale. Music links scenes smoothly. Although Marclay was influenced by the diffuse, chance organizations promoted by John Cage, some of his earlier work emphasized through-line linkages and blending as well. Marclay’s famous record-album collages allow a unified figure to emerge as a gestalt binding together disparate images. On the right, you can see this happening in Guitar Neck (1992), which virtually diagrams the sort of smooth juxtapositions we get in The Clock.

The result has a fairly slick texture. It goes down easily. I admire the way that Marclay and his assistants have rummaged through a vast archive and pulled together a majestic, utterly entertaining assembly. But emotionally it’s mostly cold. The year-end obituary tributes on Turner Classic Movies, reminding us that the perfect faces and bodies gliding past us are definitively gone, are more throat-catching than anything I saw here. Along another dimension, so are Conner’s A Movie and his dissection of the JFK assassination, Report (1963-67). Just as important, none of what I saw seemed to me particularly challenging or discordant, and in this regard The Clock parts company with the comparable film traditions.

Structural film was notoriously demanding, ruffling viewers’ perceptions and trying their patience. And experimental compilations were often seeking to shake us up, sometimes in absurd ways. An earlier blog entry of ours illustrates how Baldwin’s Mock Up on Mu (2008) builds disconcerting scenes out of bits taken from other movies. A man and woman constantly shift their identities and positions while their conversation continues without missing a beat.

Crucial to the classic compilation films is the central innovation of collage: the fragments do not blend into a smooth whole. There are clashes between one shot or clutch of shots and the next. There’s also a sense of material differences. Each piece of scuffed or distressed footage retains something of its own integrity. In his sound work, Marclay too claimed an interest in the “sound patina” of vinyl LPs:

When a record skips or pops or we hear the surface noise, we try very hard to make an abstraction of it so it doesn’t disrupt the musical flow. I try to make people aware of these imperfections and accept them as music; the recording is a sort of illusion, while the scratch on the record is more real.

But the shots in The Clock are mostly scrubbed clean of imperfections, presenting a sleek surface that facilitates the flow across shots. The movie is a pure product of the DVD era, with all those gleaming images so easily appropriated. At times Marclay manages to match weather conditions, with rain in one scene carrying over into the next. This tactic creates an intriguing sense that the two movies are set in a shared world, but it makes the gaps between the images even narrower.

For about twenty years there has been a controversy in the gallery world about whether the burgeoning tradition of “artists’ films” owes anything to avant-garde film traditions. It’s often summarized as the difference between the white cube of the gallery and the black box of the movie theatre. By setting The Clock alongside collage compilation films, am I guilty of comparing apples and oranges? For instance, the films have fixed beginnings and endings, whereas The Clock is an installation that can be entered at any point. It’s not a film but rather, to use a current phrase, a “time-based audiovisual work.” Moreover, some will argue that Marclay’s lineage doesn’t consist of Cornell, Conner, Baldwin, and Structural Film but rather Fluxus, Minimalism, Punk, and Scratch-and-Mix. (Marclay has devised a turntable he can play like a guitar.)

All of which carries some weight, but I see enough common features between the two traditions to make my main point: Based on what I sampled, this is an ingratiating work, virtuosic in a Postmodernist way. But it doesn’t risk the roughness, the boring patches, and the confusions of the film traditions I’ve invoked. Perhaps the most condemnatory thing you can say about The Clock is that it runs like clockwork.

But maybe things get more disruptive in the 89.6 % I wasn’t able to see.

This entry was written fairly early in The Clock‘s Manhattan run. (Thanks to James Schamus for tipping me to it.) I had no trouble getting in at 10:40 AM and staying until about 1:15. But it quickly became a sensation. A friend and I tried to visit on a chilly Friday night and confronted a long line. I heard from others that the line was just as forbidding at 5:00 AM. The problem, of course, is that you could wait a very long time, since there’s no set point when many are likely to leave. (Nobody will say, “This is where we came in.”) This New York Times article traces the rise of the Clock cult. The article also confirms that midnight is a high point of the video.

Yet another Times piece discusses The Clock as akin to recorded music, making some points related to mine above. Here is a loving account by Jerry Saltz, who logged nineteen hours on duty. Easy to enjoy and admire, Marclay’s piece probably deserves to be added to Christian Lander’s list of Stuff White People Like.

A good overview of the artist’s earlier work can be found in Jennifer Gonzalez et al., Christian Marclay (London: Phaidon, 2005). My quotation comes from p. 33.

On the experimental compilation film, see William C. Wees, Recycled Images: The Art and Politics of Found Footage Films (New York: Anthology Film Archives, 1993). See also Stefano Basilico, ed., Cut: Film as Found Object in Contemporary Video (Milwaukee Art Museum, 2004). P. Adams Sitney’s Visionary Film, second edition and thereafter, provides the most influential account of the Structural tradition. Scott MacDonald discusses Zorns Lemma at length in Avant-Garde Film: Motion Studies. For incisive analyses of how compilation and Structural films elicit particular activities from their viewers, see James Peterson’s Dreams of Chaos, Visions of Order.

Thanks to Jim Kreul and Jonathan Walley for guidance in the controversy about artworld and filmworld traditions. Jonathan’s essay “Modes of Film Practice in the Avant-Garde,” in Tanya Leighton’s collection Art and the Moving Image: A Critical Reader, is a useful guide to these and other trends. I advance some notions about the user-friendliness of another artist’s film project in this entry on Matthew Barney’s Cremaster cycle. Kristin and I have written about associational form in Conner’s A Movie in our book Film Art: An Introduction.

PLANET HONG KONG: The dragon dances

The Iceman Cometh (aka Time Warriors, 1989).

DB here:

Planet Hong Kong, in a second edition, is now available as a pdf file. It can be ordered on this page, which gives more information about the new version and reprints the 2000 Preface. I take this opportunity to thank Meg Hamel, who edited and designed the book and put it online.

As a sort of celebration, for a short while I’ll run a daily string of entries about Hong Kong cinema. These go beyond the book in dealing with things I didn’t have a chance to raise in the text. This is the third one. The first, a list of about 25 Hong Kong classics, is here. The second, an overview of the decline of the industry, is here. The fourth is a photo portfolio showing some stars; it’s here. Then comes an entry on western fandom, a photo gallery of director snapshots, and finally some reflections on the value of film festivals, capped by a list of some personal favorites. Thanks to Kristin for stepping aside and postponing her entry on 3D.

The longest chapter of Planet Hong Kong deals with action films. Here are some further thoughts on this fascinating genre.

Four aces of action

Tiger on Beat (1988).

Directing any action sequence poses several tasks. Once the stunts are decided upon, I can think of at least four such tasks.

1. The filmmakers need to present the physical actions clearly enough for the viewer to grasp them. Who hits whom, and how? What did X do to duck Y’s bullet? Which car is pursuing, which one is fleeing?

2. If the fight or chase is to be prolonged, one needs to come up with a series of phases that take the action into different areas of a locale, or into ever more dangerous situations. The classic arc is a fistfight that pushes the combatants to the edge of a cliff or roof, with the protagonist about to be shoved over. In other words, the action scene typically has a structure of buildup.

3. An action scene can express the emotions of the fighters—perhaps wrathful vengefulness on the part of one, versus cold calculation on the part of the other.

4. Finally, the filmmaker might want to try for a physical impact on the viewer. Just as sad scenes can make us cry and comic scenes can make us laugh, action scenes can get us pumped up. We can respond physically: we can tense up, blink, recoil, twist in our seat, and so on. How can the filmmaker achieve the level of engagement that Yuen Woo-ping emphasized in an interview with me: “to make the viewer feel the blow.”

I think that 1 and 2 are basic craft skills, with 3 and 4 being measures of higher ambitions on the part of filmmakers. Not everyone agrees. Philip Noyce says that incoherence (i.e., lack of clarity) is no problem:

I don’t necessarily think the audience member is looking for coherence; they are looking for a visceral experience. If they want coherence they can watch television.

Put aside the last comment, which begs for a bit more explanation. Noyce goes on to suggest a common rationale for lack of clarity: if the action’s confusing, it’s because the character is confused too. He praises Paul Greengrass’s framing and cutting in the Bourne films because

. . . The camera was used for its visceral possibilities rather than its literal ability. We felt the chase from the inside, where sometimes disorientation becomes an asset because it’s all about the velocity. Sometimes the pursuer and pursued don’t know where they are in relation to each other.

Greengrass’s fans have employed a similar argument, not so far from Stallone’s claims about The Expendables. It seems that many contemporary directors have concentrated on the fourth task, and to some extent the third, the expressive one (but only if the fighters’ emotion is disorientation). Job 1, basic and clear presentation, has become less important.

Yet it seems to me that the contemporary blur-o-vision technique doesn’t create a very sharp or nuanced impact. In effect, filmmakers try to amp up our response through jerky cutting, bumpy camerawork, and aggressive sound (which may be a major source of any arousal the movie yields). The result often doesn’t depend on what the actors do and instead reflects what can be fudged in shooting or postproduction. But we’re wired to react quite precisely to the movements made by living beings, human or not. If the film doesn’t make those movements at least minimally clear, we’re unlikely to sense anything more than a frantic muddle.

Further, Noyce doesn’t consider the possibility that a vigorous visceral effect can be created in and through coherent presentation of the action. The choice isn’t either/ or. The Asian action tradition, especially as practiced in Hong Kong, shows that we can have the whole package, often in quite elegant form.

OTT is OK

The Hong Kong tradition is probably most evident in its resourcefulness in fulfilling Task no. 2: creating an escalating pattern of mayhem and hairbreadth escapes. Filmmakers have been quite inventive in dreaming up outlandish twists in the action. The climax of Tiger on Beat (1988), from master Lau Kar-leung, indulges in what fans would call OTT (over-the-top) stuff. Above, outside a shop selling sailboats, Chow Yun-fat uses a clothesline to snap his shotgun out and blast the gang inside—becoming a literal gunslinger. Stepping up the intensity, Conan Lee Yuen-ba gets to work in a chainsaw duet.

The striking thing is that such flagrantly loopy combat is quite exciting, even exhilarating, while the realism that Noyce and Stallone promote can leave us fairly unmoved. Lesson: Artificially shaped grace can be tremendously arousing. Don’t forget how people get carried away watching dancing, acrobatics, or basketball.

I’ve speculated that the blur-o-vision action style is popular in Hollywood partly because it can suggest violence without showing it, so the sacred PG-13 rating isn’t at risk. No such qualms afflict Lau Kar-leung, who shows the main villain pinned to a table by Lee’s chainsaw. OTT again.

Note that each shot is from a different camera setup, typical of the Hong Kong “sequence-shooting” method. In addition, the whole scene integrates many elements of the setting into the fight. You get the impression that a Hong Kong action choreographer, stepping into a barber shop or a hotel lobby, instinctively thinks: What could be a weapon? What offers cover if someone rushes in with a gun? The Tiger shop yields barrels of paint, chainsaws, and worktables that can collapse under a man’s second-story fall. Even more exhaustive (and exhausting) is the classic fight at the end of Bodyguard from Beijing (1994). Here Corey Yuen Kwai, locking his antagonists in a modern kitchen, makes punitive use of not just knives and cutting boards but also the faucet and dish towels.

So part of what engages us in Hong Kong action is the filmmakers’ inventiveness in finding new ways to develop the basic premises of fights and chases. But this Tiger on Beat sequence also gives us the action in an utterly clear and cogent way. Every shot is brightly lit and crisply composed, with vivid colors in the sets, like those slashes of red. The cutting, while fast, makes everything totally intelligible through matches on action, obedience to the 180-degree rule, and a rock-steady camera. On top of all this, the thrusts and parries are given emotional force through the antagonists’ gestures and expressions (furious, startled, agonized). So conditions 1 through 3 are satisfied.

After this scene, we might ask Philip Noyce: Visceral enough for you?

Cutting to the chase

Matters of clarity, buildup, expressiveness, and impact on the viewer raise the perennial debate among Old China Hands, Martial Arts Division. To cut or not to cut?

For some aficionados, the less cutting the better. In classic kung-fu of the 1970s the full frame and longish take let actors show that they can do real kung-fu. No need to fake it through editing tricks. Actually, though, these films are quickly cut. Directors of the period realized that if the action is cogently composed, you can edit long shots as rapidly as you can close-ups.

No doubt, there are powerful effects you can achieve in the single shot. Admirers of full-frame action can point to an escalator gunfight in God of Gamblers, in which one passage is ingeniously staged in a single deep shot. Ko Chun’ s bodyguard Lung Ng fires at his pursuer in the upper floor.

His opponent falls down the opposite escalator, but another comes up behind, glimpsed in an aperture of the railing, and he fires at Lung.

Lung rises from the extreme foreground to return fire, and in the distance we see his attacker fall out of the slot at the railing.

On the big screen, you can feel your eye leaping from foreground to background, zigzagging across the frame. The dynamism of the action is mimicked in the rapid scanning we execute in taking it in. The eye gets some exercise.

Still, editing can serve my four purposes too. Some of the disjointedness of modern action scenes, we tend to say, comes from the speed of the cutting nowadays. Yet fast cutting can be quite coherent. There are about 490 shots in the twelve-minute climax of Tiger on Beat; nearly all are from different setups, and some are only a few frames long. Since the classic Hong Kong tradition builds upon a commitment to clear rendition of the action, it can use cutting to highlight information or repeat it. At one point, Chow whips his shotgun around a doorway and yanks his rope to pull the trigger on men he can’t see. We get five shots in three seconds.

The shots run, in order, 10 frames, 8 frames, 10 frames, 16 frames, and 38 frames. (I’m a frame-counter.) The lengthiest shot is about 1.5 seconds and the shortest is 1/3rd of a second. Yet each bit of action is so pointedly presented that it’s impossible to misunderstand, while the pace of the cutting forces us to keep up.

At an extreme, we have something like Sharp Guns (2001), a very low-budget, somewhat smarmy actioner that creates two spiky moments out of close-ups. Tricky On, the leader of our hit team, is pinned down alongside a mop-haired thug.

The kid recognizes him and raises his pistol in big close-up.

On, in even tighter close-up looks off, and the kid follows his glance.

A nearly abstract blade slices into the frame and the kid turns, his face going wan from the glare of the metal.

A hand thrusts. A neck bleeds.

Rack focus to On. Cut to Rain, the female assassin. The unfortunate thug’s head in the foreground of each shot specifies where each one is.

The fragmentation intensifies when soon afterward a blade whizzes leftward into the frame. In the next shot it glides past Tricky On.

On follows it with his eyes. Cut to another thuggish head, on his other side, with the blade embedded.

Rack focus again as the body slides down. Cut back to Rain, who has again saved her boss.

We haven’t had a single establishing shot in this sequence. The play of glances and turning heads, along with occasional foreground elements, lets us instantly understand that Rain has protected On from thugs on his left and right. Kuleshov would be happy.

Sharp Guns is surely no masterpiece, and you suspect that the close-up strategy pursued by director Billy Tang Hin-shing was a cheap way out. But give him credit for ingenuity, for well-timed cutting and movement, and for keeping the shots steady and legible. (Handheld shooting would dispel the force of the passage.)

Strongly marked cuts can also contribute a decorative punch. In A Better Tomorrow (1986), Chow is again pinned behind a door, and Woo cuts as he pokes his pistol around the edge.

The burst of that yellow slab in the new shot, counterbalancing the dark red of the earlier one, becomes the pictorial equivalent of a muzzle flash. Wouldn’t you like a bold cut like this in your film?

The pause that refreshes

Choreographer Yuen Bun during the filming of Throw Down (2004).

These are pretty flagrant examples. More commonly, Hong Kong cuts serve to sustain a line of motion or break one off abruptly. Later in the Better Tomorrow gunfight, Chow swivels from one adversary to another, who comes sailing in from above. (Remember: Artifice isn’t bad. And John Woo was an assistant director to Chang Cheh, one of the gurus of the 1970s martial arts cinema. In those movies people fly all the time.)

Woo is famous for using slow motion, but here what prolongs the movement are the cuts. They continue the movement of the thug as he’s hit and starts to fall, but oddly they suspend him in time a bit too.

When he finally descends, the camera pans down with him as he lands on the car. The next shot completes the movement, putting us in the car as his head smashes through the window.

Like the Tiger on Beat sequence, this passage exemplifies what Planet Hong Kong calls the pause/ burst/ pause pattern characteristic of Hong Kong action scenes. In the shots above, the soaring thug enters the first shot 7 frames before the cut. The next two shots run 13 frames and 18 frames. Most interesting is the last shot, the one from inside the car. It lasts 62 frames, making it the longest in the series. 30 of those frames show the thug’s head crashing through the window, but the remaining 32 frames have no movement except for his swaying tie. The sequence has paused for a little more than a second, sealing off this bit of action.

Another editor might have interrupted this last shot while the head was in motion, but the Hong Kong pause/ burst/ pause principle creates a distinct rhythm. A moment of stasis is followed by a stretch of sustained movement, smooth or staccato, building to a peak; then another instant of stasis. This pattern contrasts with the unorganized bustle typical of American films’ sequences.

I think that the Hong Kong tradition has shown what benefits arrive when directors strive to fulfill the first three of my four action tasks. I don’t have time here to go further, but PHK argues that the first three goals form a basis for the fourth—a strong, deeply physical engagement with the action. This need not conform to standards of realism if it galvanizes our eye and accelerates our pulse. What Eisenstein dreamed of, filmmakers in Japan and Hong Kong achieved: a fusillade of cinematic stimuli that pull us into the sheer kinetics of expressive human movement. Through precise staging and cutting and camerawork and sound, these directors offered us not an equivalent for a character’s confusion (we live in that state much of the time) but a galvanic sense of what pure physical mastery feels like.

After writing this blog, I was reading Alex Ross’s fine essay collection Listen to This and came across his essay on Verdi, which in an aside (pp. 198-199) notes the pleasures of OTT unrealism.

Most entertainment appears silly when it is viewed from a distance. Nothing in Verdi is any more implausible than the events of the average Shakespeare play, or, for that matter, of the average Hollywood action picture. The difference is that the conventions of the latter are widely accepted these days, so that if, say, Matt Damon rides a unicycle the wrong way down the Autobahn and kills a squad of Uzbek thugs with a package of Twizzlers, the audience cheers rather than guffaws. The loopier things get, the better. Opera is no different.

For more on the construction of Hong Kong action scenes, see here and here elsewhere on this site. A fuller discussion is in Chapter 8 of Planet Hong Kong.

14 Amazons (1972).