Archive for the 'Film technique: Editing' Category

Direction: Come in and sit down

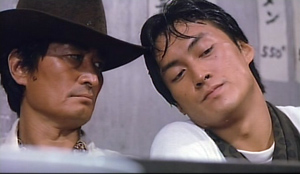

Tampopo (1985).

There is what we call the Hollywood Style. . . . . Master shot [filmed] from the very beginning [of the scene] to the end, then a close shot from beginning to end, then from angles A and B, cutaways, et cetera. Then all of the materials are assembled later in the editing room. But in Japan, the editing plan is prepared before shooting. When you cut, it’s a matter of trimming heads and tails and just putting it together. Three days after the end of filming, there is a rough cut of the film.

Itami Juzo (The Funeral, A Taxing Woman).

DB here:

Planet Hong Kong 2 still on the way…. very close to ready…. deciding among cover designs…. soon; sooner if possible….

In the meantime, some creative choices involved in directing a simple scene.

Shanghai’d

What could be easier than getting a man into a room and sitting him down? The opening scene of Shanghai (2010) seems to me to bungle this basic piece of tradecraft.

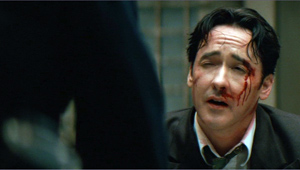

In the image above, journalist and spy Paul Soames is being beaten up by the minions of Captain Tanaka. Who’s the poor sod who has to hang those big flags so high in movie torture chambers like this? Anyhow, soon the torturers drag Soames up the stairs, likewise in long shot, to meet the captain.

A brief shot of a door opening seems to put us in Soames’ shoes. But that viewpoint isn’t carried through consistently: we cut abruptly to the other side of the door, to a long-lens medium shot of Tanaka opening it.

Soames steps forward and is greeted by Tanaka.

Now comes the establishing shot, from quite far away, as Soames walks to the desk. This shot is interrupted by cutting back to the shot of Soames moving forward.

As the shot continues, Soames sits down and looks up. Throughout the scene, this setup will be assigned to cover Soames, with the camera panning and reframing as necessary.

Counting the swinging-door shot, it has taken four shots to get Soames into the room. But the actors aren’t yet fully in place. As Soames turns his head, Tanaka (back to master shot) moves around on Soames’ left side. The phone starts ringing.

Tanaka begins to halt at his desk, but before he stops moving we cut again to Soames, whose attention has shifted to the phone. He has asked that his embassy be notified, and now he suggests that it’s the embassy calling.

Cut to a close-up of the telephone, the object of Soames’ attention, and another shot of Soames, as before, as he looks expectantly back at Tanaka.

Now we have a closer shot of Tanaka, still slightly moving, and we catch his disdainful expression.

After Tanaka lifts and drops the receiver to cut off the call (another close-up), he settles into place. The rest of the conversation is played out in those loose over-the-shoulder shots that modern directors like so much.

Throughout, the shots of Soames seem to be from the same camera setup as when he entered. No repositioning of the camera marks stages of his part in the conversation, though at the end of the scene a pair of close-ups shows Tanaka asking, “Where is she, Mr. Soames?” Cue the flashback.

It’s not just that it took director Mikael Håfström over a dozen shots to get Soames and Tanaka into position for their central duet. Hitchcock might use several shots too. But each of his would be calibrated for specific expressive effects, such as subjective point-of-view treatment or a striking composition. Instead, the Shanghai shots exemplify a fairly casual cover-everything approach–a scattergun version of what Itami called the Hollywood Style.

Here the individual shots make a big deal out of a simple piece of business. We don’t need to see all of Tanaka’s office (since the rest of the space never gets used in the scene), and it doesn’t need to be so vast in the first place (except to announce that this is an expensive movie). The long-lens camera setup that lets Soames advance into the room and sit exists solely to let us watch the actor act, and it provides awkward cuts when bits of it are embedded in extreme long-shots.

It’s not hard to imagine alternatives. A straightforward tracking back from Soames as he enters and sits, framed from further away, would have kept both him and Tanaka in the frame. This framing could have easily shown Tanaka coming around to take up a position in the foreground by the desk, perhaps turned partly toward us so that we could peg him as a major character. Then if you insist on a cutaway to the ringing telephone, it would have had more impact, interrupting a sustained shot and contrasting to the fuller frame showing the two men.

Today many directors believe that we must always see the face of the person who’s speaking. So we get lots of shots, mostly singles, one per line, and each face is usually in close-up or medium-shot. Hence the great number of cuts per scene; here, counting from the swinging door, we get 23 shots in 97 seconds. And hence the repetitive reverse shots that cover the conversation.

I’m not the only one who notices these things. “If I see another over-the-shoulder shot,” says Steven Soderbergh, “I’m going to blow my brains out.”

Television probably has a lot to do with the emergence of this style, as some historians, me included, have argued. You have to be a good director to overcome the choppiness inherent in this manner of filming. I don’t think that Hafstrom did that. If the director had planned his shots in the finer-grained way Itami indicates, we might have had more visual variety, along with compositions and cutting that take us beyond the actors’ faces and line readings.

Dandelion soup

Now we might look at how Itami does it. An early scene of Tampopo (1985) also demands that a man, along with his sidekick, come into a room and sit down. We see Goro the trucker and his pal Gun enter the noodle shop, along with the little boy they’ve found lying on the street. We see them first from outside and then from inside the new locale, much as in our Shanghai example. But there’s no need for anything like that insert of the opening door.

Cut to a point-of-view shot that makes a point: Goro is entering a room full of thugs. Itami pans to show two knots of men in the shop, some of them threatening.

While each Shanghai shot does one thing at a time, this shot does two things at once. This shot sets up the hostilities that will ensue, while also laying out the space of the shop and positioning all Gun’s adversaries in it, along with the proprietress Tampopo.

Cut back to the men at the door, but it’s a different framing, from further back, than we saw initially. Now some of the thugs are staring at our heroes.

Itami is calibrating his compositions to give us new information. If this composition had been used for the first shot of the men entering, the subjective pan across the room wouldn’t have been so surprising. Now the camera cranes back to follow Goro and Gun striding to the middle of the shop and sitting down. They order bowls of noodles.

This orientation will be the dominant one in the course of the scene. But the space isn’t as bare as in the Shanghai scene; the men we see dotted around the room will play important roles in the action now and later. As in the Shanghai scene, there are cuts to close-ups, but they show more informative items than a ringing telephone. One shot picks out Tampopo herself (establishing her as a major character), another picks out Gun’s skeptical view of her cooking technique, and a third tilts down to show her hands cooking noodles in water not yet boiling.

To the noodle connoisseur Gun, this proves that she’s a maladroit cook, and another shot of the two men shows his reaction.

Cut to a long-shot. The long-shots of the office in Shanghai are always from a single position (the result of straight-through master-shot coverage), but here we get a slightly different framing than we’d seen earlier. The camera is somewhat lower, which allows Itami to stage a little piece of business. Tampopo’s son Tabo runs unseen out from behind the young thugs, along the aisle behind the stools, into the foreground, and out frame right. He has been beaten up outside, but Tampopo takes it in stride.

When Tabo has gone, the men resettle in for the next phase of the scene, when Tampopo serves Goro and Gun. The entire shot we’ve just seen is held for forty-one seconds. Soon a fight will erupt, delaying the revelation of how awful Tampopo’s noodles are.

This is not virtuoso direction, but it is smooth and precise. Each shot blends with the next with a degree of care we don’t get in the Shanghai instance. That’s partly because each shot is given its own small, completed arc of action. (The nine shots I’ve listed run ninety seconds.) For example, Tabo’s run down the aisle is prepared by a slight shift in Goro’s glance at the end of an earlier shot I’ve mentioned. He looks toward the door and tells Tabo he’ll catch cold.

This moment prepares us for the next bit of action, while also setting up the trucker’s gruff concern for the boy, an important element of the plot to come.

More generally, across the whole scene each long shot does more than simply orient us or cover changes in position; it’s enlivened by movement and incident. Nothing in the Shanghai scene approximates Itami’s willingness to let body language replace facial close-ups. Here Goro coolly samples the noodles while the gang prepares to rumble.

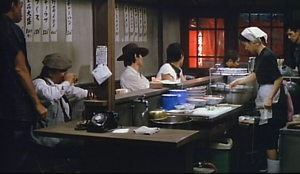

Later, an entire scene will be played in a packed long shot lasting nearly a minute. Goro has brought Tampopo to watch a master chef at work, and Itami is perfectly okay with concealing her face as she calls off all the orders that people have just made. We don’t need a close-up of her expression when she speaks; the important thing is her aptitude and the customers’ enthusiastic applause.

An unassertive shot like this, you want to say, respects the audience by letting us see everything that matters at each moment. We call it directing a movie.

Itami’s remarks in our epigraph come from Bob Strauss, “Director Juzo Itami,” Premiere (June 1988), p. 25. Soderbergh’s comment about OTS shots is taken from “Matt Damon: Steven Soderbergh really does plan to retire from filmmaking,” at the Los Angeles Times.

Shanghai has probably not come to a theatre near you. Delayed during the shooting, it sat on the shelf for some time before its premiere last summer in China. It’s announced for U. S. release in 2011 but the Weinstein company website says only that it’s “coming soon.” Planet Hong Kong redux will beat it, for sure.

As chance would have it, Tanaka in Shanghai and Gun in Tampopo are both played by Watanabe Ken.

My arguments about the emergence of this “intensified” version of classical continuity are made in The Way Hollywood Tells It, pp. 117-189. I’ve done a blog on the idea here; it’s hardly fair for me to compare Nora Ephron with Lubitsch, but she sort of asked for it. For more on economical staging and cutting, see our entry on Spielberg’s shooting style, as well as the idea of the Cross. For another comparison of Hollywood direction with an Asian alternative, see our entry on Jackie Chan’s Police Story.

A. D. Jameson makes strong points about inefficient shot breakdown in his essay “Seventeen Ways of Criticizing Inception.” Jameson invokes The Ghost Writer as a good counterexample, and indeed Polanski’s film often displays the sort of cut-to-cut restraint and control that Itami calls for. Jameson elaborates further in another epic post. There’s also an intriguing discussion at Jim Emerson’s Scanners blog of how much a filmmaker should rely on close-ups; the film at hand is Black Swan.

P.S. 5 January 2010: We’ve had an enthusiastic response to this entry; thank you, Twitterers. It occurred to me that readers might be interested in a similar comparison between Asian filmmaking and U.S. practice in a very early entry, back in 2006. Ironically, Soderbergh’s Good German was involved, the subject of an earlier post. The contrast case was Johnnie To’s PTU.

Shanghai (2010).

Back to the vaults, and over the edge

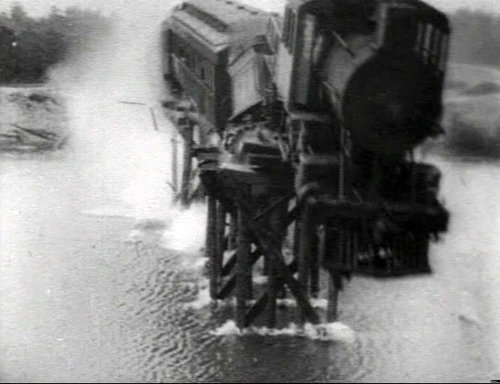

Unstoppable? Not really. The Juggernaut (1915).

DB here:

A few weeks ago, I praised Variety for making its back issues available digitally. The result is a magnificent vault of information. I also expressed frustration that the recent makeover of The Hollywood Reporter neglected to offer access to its original online archive, which indexed issues across the last twenty years. On the last point, some news.

First, my inquiry to the address listed on the HR website eventually yielded this blue note.

Good Morning,

We apologize for the delayed response.

I do not think there is a way to go back to prior to the changeover.

You would need to contact the publisher about that, as we do not handle the website directly.

Here is a phone number for you 323-525-2150.

Thank you.

I called the number, which handles only subscriptions, and the person answering had no idea what I was asking about.

But all is not lost. My first efforts to access the archive turned up very little for 2010, but shortly afterward I was able to access items from most of this year. Now, if you type a search term into the Search box of the HR site, it brings up items from as far back as 2008. This is an improvement over earlier attempts I made. It seems that THR is gradually adding old material to their archive, in reverse order.

Unfortunately, the search mechanism is quite indiscriminate. Searching “Johnnie To,” with and without quotation marks, yielded 290 hits, but I could find no articles about Johnnie To. Instead, the items with highest relevancy concerned Johnny Depp, Johnny English, John McCain, and the new Narnia movie.

The best news of all came from alert reader David Fristrom of Boston University. He advises me that the old HR archives are still available through LexisNexis. So I tried there with Johnnie To, and I got 338 references, stretching back to 1992. The ones at the top of the relevancy scale were indeed about Mr. To, including a Cannes piece called “Fest’s Red Carpet Flows with Blood.”

Accessing the archive isn’t straightforward, but you don’t need a subscription to HR if your library has purchased access to LexisNexis. I append David’s instructions at the end of this entry. Thanks to him for sorting this out for me.

Now, back into the Variety vaults.

This one’s a real train wreck

On 12 March 1915, Variety reviewed The Birth of a Nation. Alongside that review sits one of The Juggernaut, a Vitagraph feature directed by Ralph Ince. The reviewer, “Simc.,” dwells almost entirely on what he calls “the train-through-the-bridge thing.” The producers bought an old locomotive and some passenger cars, built a flimsy bridge, and ran their train off into what appeared to be a river.

The review exhibits some Variety touches that are still with us. Take the (quite reasonable) idea that nearly every movie is too long. “If this five-reeler were cut down to three reels, which could easily be done, the Vitagraph would have a real thriller.” There’s also the notion that people who come to the see the movie should be aware of its main attraction. “If the audience knows a train will go through a bridge at the finish, it won’t mind the fiddling about in the first four reels before that scene is reached. But if the audience doesn’t know what is to come, there may be many walk-outs.” At the beginning of Unstoppable we’ll sit through all the union and non-union wrangling and alpha-male preening if we’re sure we’re going to see a train that is certifiably unstoppable, except that it’s likely to be stopped by our heroes.

The Juggernaut does give us a pretty spectacular train wreck, as you see above. The entire film may not survive, but we have a version of the last reel (perhaps because a collector thought it worth saving). Train or no train, the film is of interest in showing what Griffith’s rivals were up to.

The plot centers on a crooked railroad magnate, Philip Hardin, and his college friend John Ballard. In the reel we have, Hardin’s daughter Louise, who loves John, sets out on an errand. When her car stalls she boards an express train. A track-walker finds worn ties on a bridge and warns the company, but too late. As Hardin races to stop Louise’s train, it arrives at the bridge and he watches it topple into the water. The sight kills him on the spot. John arrives and swims out to rescue Louise.

That’s when things get dicey. According to the Variety review and other sources, Louise dies in the wreck. Simc again:

The leading woman of the film, Anita Stewart, is discovered dead, lying against one of the windows, with particular pains taken that her features shall be clearly visible. . . . Anita is carried to shore and lain alongside of her father, who had died of heart failure (on land) a few moments before.

In the version available on DVD, John does bring her body ashore, but she revives, lifts herself up, and embraces him. The print ends there. Why the varying ending? Perhaps this is a version made at the time for a different market or in response to censorship, or it might be a rerelease using alternative footage. Or perhaps the press reviews were based on a synopsis supplied by Vitagraph, and the studio made modifications in the print before release.

The Juggernaut is also intriguing stylistically. By this point, crosscutting and scene analysis were common techniques in U. S. films. To set up the perilous situation, the cutting alternates shots of the track-walker, of Hardin, and of Louise. Once Hardin discovers that Louise is on the train headed for the dilapidated trestle, we are set up for a last-minute rescue–which fails. A particularly interesting series of shots shows Hardin’s trajectory converging with the train’s path. Riding in a power boat, Hardin looks back and we get a shot of the train in the distance, suggesting that he can see it.

From this we cut to a shot of Louise, confirming that she’s on board and showing her innocent lack of awareness. Then we get a repeated framing of the train rushing toward the bridge.

After another long shot of the train, we get a shot of Hardin in his powerboat with the train whizzing by in the background. This confirms that he was indeed watching it approach off screen left in the earlier shot, and it shows that he isn’t likely to catch up.

Once the train has toppled into the stream, there are some striking shots of people trapped inside or scrambling to escape. We see Louise raise one hand and then freeze, as if dying.

Earlier, there’s some emphatic “classical” cutting when Hardin learns that Louise is in danger. An enlarged framing (via an axial cut) underscores his reaction to the telegram.

Most striking is a series of shots of the dead-or-not Louise; the abrupt enlargement of her face has something of the force that Kurosawa would channel in his axial cuts.

Soon Ralph Ince cuts back along the same camera axis, and inward again as the couple embrace.

I can’t recall a comparable stretch of “concertina” cutting in the intimate scenes of Birth, and no such tight views of faces either. Griffith sometimes gives us “close-ups within medium-shots” by means of irising and vignetting.

Other directors (e.g., Dreyer) liked to use the serrated surround to highlight faces, but the American norm eventually became the unadorned closer view, as in the shot of Louise in The Juggernaut. Such shots probably saved production time as well. We’re confronted with the familiar situation that sometimes non-Griffith films from 1915 (e.g., The Cheat, Regeneration) look somewhat more “modern” than does Birth.

Going back to the train-through-the-bridge thing, the staging of the scene in late September 1914 elicited a lot of publicity. For one thing, the cost was played up; I’ve seen stories claiming $20,000, $30,000, and $50,000. The New York Times wrote up the shoot twice; the second of these could well be a publicity release from Vitagraph. According to the Times, the “river” was actually a flooded quarry. Before the shoot, buzz leaked out and crowds reported as numbering thousands showed up to watch. The crew spent hours herding them out of camera range. Actors were freezing in the water by the time cameramen got to take their shots. The Times also claims that the crash was filmed by fifteen (or twenty-five) cameras, a stupendously implausible number, especially in light of the footage we have. Worse, according to the second NYT story, Ince decided that the first pass didn’t work and they would have to start all over with a new train! A retake is not mentioned in Variety’s coverage, which does report some studio rivalry:

The ink on the New York dailies telling of the Vita’s big wreck stunt in the cameraing of “The Juggernaut” had hardly dried when the Universal sent over camera men posthaste Sunday to take views of what was left of the wreck. [Vitagraph studio manager Victor Smith], getting a hunch, got on the ground ahead of them and with a sturdy band of Vita “protectors” nipped the U’s little scheme in the bud.

One can only imagine how the “protectors” dealt with the Universal boys. Once more, the Variety Vault gives us the flavor, and perhaps sometimes the facts, of heroic times.

How to access the Hollywood Reporter archive, courtesy David Fristrom:

Once you are in LexisNexis, it can be a little tricky to search in The Hollywood Reporter (for some reason it doesn’t show up if you type “Hollywood Reporter” into the “Source Title” box), but you can follow these steps:

1. Click on “Power Search” in the upper-left corner.

2. On the “Power Search” page, find the “Select Source” box (near the bottom) and click on the “Find Sources” link.

3. On the “Find Sources” page, type “Hollywood Reporter” into the “Keyword” box and press enter.

4. At the top of the results should be “The Hollywood Reporter.”

Check the box next to it, then click on the “Ok-Continue” button that appears in the upper right corner.

5. You are now ready to search in the Hollywood Reporter archives –just type your search terms into the search box.

Thanks again to David!

The Variety review of The Juggernaut appears in the issue of 12 March 1915, p. 23. The story about Universal staff trying to shoot the wreckage is “Vita Putting It Over,” Variety, 10 October 1914, p. 23. The New York Times articles are “Film Train Wreck Almost a Tragedy,” NYT, 28 September 1914, p. 13, and “Tossing Dollars Around As If They Were Pennies,” NYT, 18 October 1914, p. X7. For more on Vitagraph, see Anthony Slide, The Big V: A History of the Vitagraph Company, rev. ed. (Metuchen: Scarecrow, 1987); Tony provides some production background on The Juggernaut on pp. 64-65.

The Juggernaut excerpt is available on Nickelodia 2, a DVD collection from Unknown Video. Oddly, the snapcase doesn’t list the reel as included on the disc, nor does the product information on the Unknown Video site or Amazon. I’d welcome more information about The Juggernaut‘s plot resolution if anybody out there has any.

The Juggernaut (1915).

Once upon some times in Hong Kong

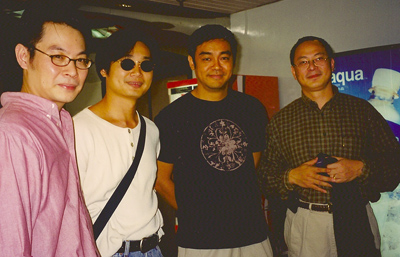

Johnnie To Kei-fung on the set of Running out of Time 2.

DB here:

Exactly nine years ago, Kristin and I were in Hong Kong. Lau Shing-hon, head of the film division of the Academy for Performing Arts, had arranged for me to be Sir Edwin Youde Memorial Fund Visiting Professor. It was a great honor, and Kristin and I enjoyed many happy sessions with Shing-hon, his colleagues, and his students. On this trip, though, something else happened. That lucky encounter has had consequences for my thinking about cinema throughout all the years since.

The encounter was the result of unintended networking. Jeff Smith, now a professor here at Madison, had been my TA in the early 1990s, when I was starting to include Hong Kong films in my courses. He caught the bug. While Jeff was teaching at NYU, a young Taiwanese man, Shan Ding, took some of his courses. Shan, who was naturally as keen on Hong Kong cinema as we were, wound up going to Hong Kong and eventually getting a job with Johnnie To Kei-fung.

So it was during our November 2001 stay that I got a call from a friend, who said that Shan was trying to reach me. Shan wanted to get together, but not in the customary coffee shop or noodle restaurant. He invited Kristin and me to come to a set.

Local heroes

Lifeline.

While doing research for my book Planet Hong Kong in 1996 and 1997, I managed to interview several directors, screenwriters, cinematographers, and action choreographers. Johnnie To was on my list of people to meet because of the cult classics The Big Heat (1988), Heroic Trio (1993), The Executioners (1993), and Loving You (1995). There was also his prestige picture, All about Ah-Long (1989) and an extraordinary movie I saw during one trip to Hong Kong, the firefighter drama Lifeline (1997). At about this time Mr. To was launching his own production company, Milkyway Image.

I keenly wanted to talk with Mr. To, but for various reasons it didn’t prove possible. I submitted my manuscript to the publisher in mid-1998, so I couldn’t incorporate discussion of the three Milkyway masterpieces of that year: Expect the Unexpected, The Longest Nite, and A Hero Never Dies. By the time the book came out in early 2000, there had been three more: Where a Good Man Goes (1999), Running Out of Time (1999), and possibly To’s finest work, The Mission (1999). There I was: the most important director of the late 1990s and early 2000s was largely left out of my book.

Ironically, soon after PHK came out, Wong Kar-wai’s In the Mood for Love and Ang Lee’s Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon triumphed at Cannes. Westerners’ perception of Chinese film changed forever. But in all this fuss, where was Johnnie To?

Making movies, that’s where. He emerged as a heroic figure of local film of the 2000s. True, Infernal Affairs (2002) and Stephen Chow Sing-chi and Wong Kar-wai sustained interest in Hong Kong movies on the international market. But Wong and Chow made films at long intervals, while IA was that rarity in Hong Kong, a “must-see” movie not starring Chow, Jet Li, or Jackie Chan. Johnnie To was just moving ahead, creating romantic comedies, cop dramas, and unclassifiable items like Running on Karma (2003) and Throw Down (2004). Election (2005) and Election 2 (2006) showed, in unprecedented detail, how triad societies governed themselves, and more daringly how they were still connected to mainland China. With his longtime collaborator Wai Ka-fai he went out on a limb with Mad Detective (2007), but on his own he gave us satisfying polars like Exiled (2006) and Triangle (2007) as well as lighter exercises like Sparrow (2008).

Unlike the reclusive Wong Kar-wai and Stephen Chow, To stepped into the public eye. He tried to sustain the local industry by hectoring the government, throwing his weight behind new awards, supporting student film contests. He worried, he has explained, that filmmaking in Hong Kong could collapse the way it did in Taiwan. And he kept surprising us—not least by signing arthouse demigod Jia Zhang-ke to make, of all things, a martial arts movie.

Most of those developments were in the future when we got the call from Shan.

One rainy street

Johnnie To and Shan Ding, Milkyway Image office, 2005.

A van picked us up on a rainy night and we drove far into the New Territories. Along the way Shan was explaining that he was a sort of man-of-all-work for Mr. To. I would see over the years that Shan would assist in scripting and shooting, he might step in front of the camera, and he would help execute ad campaigns. He was sometimes billed as a film’s “Production Supervisor,” which is probably as good a description as any. Because he has fluent English, he was the ideal liaison between Milkyway and the west. Shan played a central role in helping critics and festival programmers learn about Milkyway’s projects.

We arrived at a big abandoned storage facility in a grove of trees. A street set about a block long had been built, bathed in artificial rain and mist. Mr. To was presiding over things.

He greeted us warmly. I had met him briefly at a 1999 Hong Kong film festival event arranged by Athena Tsui and Li Cheuk-to. The festival’s Panorama section paid tribute to Milkyway’s big films of the previous year, and a seminar was held with Wai Ka-fai, Patrick Yau Tat-chi, Lau Ching-wan, and Mr. To.

But by then Planet Hong Kong was in press. Nonetheless, I came to the seminar and took notes. I hoped that some day I would write about this team’s remarkable movies.

That November night Mr. To graciously said he remembered me from the seminar. But he soon went back to work as the crew prepared for what would be a bicycle race. A bicycle race? Who’d be racing? Kristin and I turned, and I gaped. There was Lau Ching-wan.

What Chow Yun-fat was to John Woo, Lau was to To: his exemplary protagonist. Chow was virtually born in a tuxedo, but onscreen Lau projects the image of an ordinary working stiff. In To’s films he usually plays the profane, irritable, unheroic hero; or if the film has no hero, as in The Longest Nite, he becomes a glowering, implacable force.

Not tonight, though. He was as friendly as Mr. To. His English was fine and we chatted a little. For the life of me I can’t recall what we said; I was too, as the Brits say, gobsmacked. I have long known I was a fanboy at heart, but here was the embarrassing proof.

Standing next to him was Ekin Cheng Yee-kin–at that point, one of the leading jeunes premiers of Hong Kong film. He had made his career as a teen idol, particularly in the young-triads cycle known in English as the Young and Dangerous series. He was also extremely cordial.

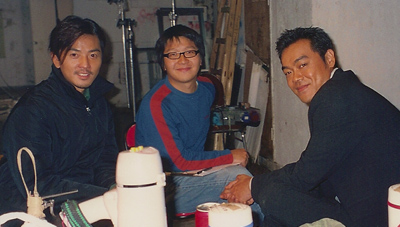

Both actors had to do a lot of waiting around between shots, of course. While we snacked on food from Styrofoam containers, there was time for pictures. Here’s one of Lau and Cheng flanking Yau Nai-hoi, Mr. To’s prolific screenwriter and later director of Eye in the Sky (2007).

We couldn’t get too close to the main set, but I did get some general shots of the crew at work. The crew filmed take after take of Lau and Cheng pedaling along the same short strip, over and over. I also got some shots of the stunt men, who were trying again and again to knock off some cars’ side mirrors. These guys take some serious spills.

Only when I saw Running Out of Time 2 was it clear that our night’s shoot, and others before and after, yielded a charming scene in which Ekin, the unnamed magician figure, taunts and exasperates Lau as detective Ho. It’s crucial because the race teaches Ho that Ekin’s mysterious cat-and-mouse game is essentially benevolent, even joyful. Staring at the set, I was impressed by how fake it looked. But on film, swathed in darkness, rain, and mist, it looks fine.

Yesterday, re-watching the movie, I enjoyed spotting the moment when we pass from the location to the set. From a shot taken on location, To cuts to a tighter shot of Lau, on the set.

Track in to Lau’s face as we hear a bike bell and Ekin whizzes by.

At Ekin’s urging, Lau grabs a bike and pursues him.

Once you see the film, you can notice how most of the shots are framed to conceal the fact that Lau and Ekin are pedaling down the same stretch over and over, sometimes in reverse directions on the set. Occasionally a changed background sign gives away the repeated takes.

Elaborate as this is set was, it’s still more economical in Hong Kong to mount such a thing than to spend nights on location to get dozens of shots. The magic of the movies, after all. And the signs enable product placement to help cover costs.

Never a man to waste a chance, Mr. To re-dresses the set a bit for Running Out of Time 2‘s cheery epilogue, when Christmas breaks out.

Just as in classical Hollywood cinema, scenes echo one another partly because it’s economical to re-use sets at different points in the movie.

This wasn’t my last encounter with Johnnie To. Shan kept in touch, and my spring visits to Hong Kong included a stopover at Milkyway headquarters. There I would run into Lorenzo Codelli, Shelly Kraicer, Todd Brown of Twitchfilm, Sabrina Baracetti of Udine’s Far East Film Fest, Grady Hendix of the New York Asian Film Festival, and other movers and shakers in film culture. Partly because of To’s promotional outreach to these tastemakers, he is much better known worldwide than he was in 2001. I managed to visit shoots for Throw Down, Exiled, and Triangle. He showed me work-in-progress versions of several films. Mr. To also sat down for interviews with me; my favorite is the one in which he went shot by shot through the “Sukiyaki” scene in A Hero Never Dies. Needless to say, I learned a lot from all these encounters.

These days I’m refurbishing my book for web publication, writing frantically while listening to Cantopop (Sammi and Faye and Gor Gor, mostly). Now I can give Milkyway its due. I’ve spent the last couple of weeks reviewing To’s oeuvre, and I’m more convinced than ever that he is one of the finest directors of the last fifteen years. Planet Hong Kong Redux will contain two lengthy sections on his films. Like all the illustrations in the new version, the stills (many from 35mm prints, not DVDs) will be in color.

As PHK Redux moves closer to online publication in mid-December, I’m mounting other items for the delectation of those discerning souls who know that Hong Kong has created one of the great traditions of film history. This week the site adds my DVD booklet essay on Mad Detective, courtesy Nick Wrigley and Masters of Cinema. And in a couple of weeks, as a run-up to PHK Redux, we’ll be putting up a gallery of celebrity snapshots I’ve taken since my first visit to Hong Kong in 1995.

Secrets

Oh, yes, what were the consequences of this evening in November 2001? Well, one was meeting a new batch of interesting people, Shan and Mr. To and Mrs. To and Martin Chappell and others. Their warm, informal hospitality constitutes one reason I come to Hong Kong every spring.

Another consequence: the conviction that I would have to write more about Hong Kong film. Having followed it since the 1970s, I thought I detected a dropoff in quality and energy in the late 90s. I wasn’t alone. The revised version of my book details how the industry went into a slump then. But the movies from Milkyway showed that you could still flourish in hard times. Seeing Mr. To’s movies made me want to stick with this tradition a little longer. So I continued to write, mostly short pieces about him, until PHK’s going out of print pushed me to update my thinking.

A third consequence of that set visit was broader and deeper. Getting to know filmmakers confirmed that I was a fanboy through and through, but I also felt it shifted me in new directions as a researcher. I’m fascinated by the practice of making movies. I still want to know, within my limited technical expertise, the tangible stuff that people do to build the images and sounds that captivate us. What tools do they use? What work routines have become standardized? What happens when technology or craft practices change?

As a graduate student, I thought that in order to understand movies we just needed to look at the screen. Although I had made some amateur films (bad ones), I failed to see that the fine grain of craft is exactly where artistry begins. By the time I started to write academic essays and books, especially The Classical Hollywood Cinema, I realized that knowing what goes on behind the screen sensitizes you to what’s there. You literally see more.

Most film academics aren’t interested in how craft can nourish artistry. In their eagerness to avoid “formalism,” they tend to neglect artistic traditions, trends, and choices. Movies are made, and the making—poeisis, as the old Greeks called it—demands concrete decisions about form and style. Filmmakers make different choices in different times and places, and we can try to analyze and explain some of those choices. As E. H. Gombrich once suggested, very simply, the artist’s key question is often: “What is there for me to do?” We need not stop there, but considering creative options and decisions is a good place to start if you want to do justice to the films, the filmmakers’ hard work, and the experiences we have as viewers.

I want to know directors’ secrets, especially the ones they don’t know they know. Planet Hong Kong was an effort to bring some of those secrets to light. I think I’ve found some more since then. Thanks to the courtesy of filmmakers like Mr. To, I’m compelled to try sharing them with you.

A fairly recent interview with Johnnie To is here. Especially interesting are his memories of growing up in Kowloon Walled City, a sort of criminal jungle. Corpses on the playground, that sort of thing.

Although the book will pay tribute to them, let me here signal two excellent online resources, now far more elaborated than when I wrote the first version of the book. Ryan Law’s Hong Kong Movie Database is indispensible for investigating people, companies, and films (detailed lists of cast and crew members). HKMDB also has a lively news section. Ross Chen’s vast and entertaining LoveHKFilm lives up to its name, with meaty reviews and news updates. There are many other fine sites, but these are the ones I’ve relied on most often. In addition, I must signal a book that came out too late for me to use; John Charles’ remarkable Hong Kong Filmography 1977-1997.

The friend whom Shan contacted was Li Cheuk-to. Since 1995 Ah-to has been my advisor, translator, editor, and host. I owe him more than I can say.

I have many other people to thank for my times in Hong Kong, and the revised PHK will do so. In the meantime, if you’re interested in Johnnie To and Milkyway, you can check my other blog entries here.

P.S. After I finished this entry there came the sad news of the death of Mr. Wong Tin-lam, a director from the classic era of Cantonese cinema. His Wild, Wild Rose (1960) is still remembered as a trail-blazer. The father of director Wong Jing, he brought a grassroots gravitas to some of the best Milkyway films, in which he was likely to play a Triad elder. Go here for more pictures and background information.

Wong Tin-lam in A Hero Never Dies.

P.P.S., 20 November: Thanks to Yvonne Teh for correcting my spelling! Check her enjoyable Hong Kong site Webs of Significance.

Bond vs. Chan: Jackie shows how it’s done

DB here:

During the 1990s several critics began to notice that filmmakers were doing something odd with action scenes.

Directors were consciously, even joyously, sacrificing clarity. When two characters were punching it out, the framing didn’t make it easy to know who was hitting whom, and how. Changes in angle and shot scale were sometimes so abrupt that you had little time to adjust. The cutting pace was so quick that you couldn’t entirely register the movement in shot A before shot B replaced it. Sometimes the spatial layout of the fight was confusing as well: too many close views, too few master shots. Later, the return of handheld shooting made many action scenes even more illegible, blurring and smearing them to the point that sound (as in the Bourne films) had to specify that a body has hit a window or a hand has busted a bottle. Now we have Sylvester Stallone’s The Expendables, which might be a new summit in overbusy, incoherent, inconsequential action.

I wrote about this trend back in the 1990s, and I’ve returned to it on occasion since. Other writers, notably Todd McCarthy of Variety, noticed it too. He referred to the full-throttle editing and “frequently incoherent staging” on display in Armageddon (1998): “Bay’s visual presentation is so frantic and chaotic that one often can’t tell which ship or characters are being shown, or where things are in relation to one another.”

A decade later comes Peter DeBruge’s review of the “muddled execution” of The Expendables: Staging simultaneous fights “might’ve worked had the editors assembled all that footage in such a way that we could tell where characters are in relation to one another or what’s going on.”

The Michael Bay approach has become the principal way in which action scenes are shot. It isn’t absence of craft that leads to these aimless bouts. The filmmakers actively want the action to be hard, even impossible, to follow. Sometimes I think that this blurred bustle is there to secure a PG-13 rating; if you could really see the mayhem, we might be moving toward an R. But filmmakers don’t say that they’re self-censoring. They seem to think that making the action illegible is creative because it promotes realism.

Stallone explains why he scrambled up the fight scenes in The Expendables.

I don’t think many action scenes are shown from the character’s point of view. They are more from the director’s point of view. On Rambo, I thought the most economical and original way to shoot [the action] would be through Rambo’s eyes—if he were directing, what would his style be? But The Expendables is an ensemble picture, so it’s somewhat of a blend. I thought, ‘This is not supposed to hang in the Louvre.’ I wanted it to be disjointed and rough, not choreographed. If you really were filming a big battle with five cameras, [their footage] would not all flow together, so we set up the [cameras] to film the action we’d scripted and told the operators they were on their own. We said, ‘Do the best you can, and we’ll use the interesting shots from the characters’ perspectives.’”

Camera operator Vern Nobles describes shooting the action as “multi-camera craziness.”

You might point out that if somebody were really filming a big fight with five cameras, at least a couple of camera operators would be shot or punched silly. And presumably a few times we’d actually see other cameras.

Realism, as usual, is simply a fig leaf for doing what you want. Virtually any technique can be justified as realistic according to some conception of what’s important in the scene. If you shoot the action cogently, with all the moves evident, that’s realistic because it shows you what’s “really” happening. If you shoot it awkwardly, that presentation is “realistically” reflecting what a participant perceives or feels. If you shoot it as “chaos” (another description that Nobles applies to the Expendables action scenes)—well, action feels chaotic when you’re in it, right?

Forget the realist alibi. What do you want your sequence to do to the viewer? Do you want it to pass along an impression of bustle and flurry? Or do you want to make the viewer wince, recoil, even mildly reenact the movements of the players? Then follow the Hong Kong tradition. Yuen Woo-ping once told me that his goal was to make the viewer “feel the blow.” To convey the effort and strain, the impact and pain: that’s something worth doing.

It’s something that the blur-o-vision tussles lack, but even fights that are more carefully filmed are strangely unmoving. In Tomorrow Never Dies (1997), there’s a fistfight on a catwalk above a rotary press line. The presentation is more or less spatially unified, but it lacks drive because of certain creative choices. For instance, when Bond punches a security guard, the man simply drops out of the frame.

Where does he go? He doesn’t fall off the catwalk but seems to grab the railing, so maybe he’ll return for another go-round. But he doesn’t. As Bond falls back, another guard sneaks up on him. The framing and screen direction suggest that he’s approaching Bond from the front.

Actually, he’s sneaking up from the rear.

When Bond turns, we don’t see his punch.

In fact, we don’t see much of anything. Although the attacker is erect in one shot, he seems to be kneeling in the next, when Bond kicks him, somewhere below the frameline.

The attacker is standing again in the next shot, and he’s flung backward by the force of Bond’s unseen kick.

When the man returns, he tries to tackle Bond. At least, I think he does. The maneuver takes place, again, underneath the frameline.

At last we get a wider shot, but this serves mainly to align the fight with the conveyor belt below the men; guess who will fall?

More fighting, with punches and grappling blocked by the men’s bodies, culminates in Bond’s adversary falling into the print run.

Even here, however, we don’t really see what happens to the victim. He plunges through the river of newsprint and the machine starts belching.

Overall, we get a mild impression of what happened in the fight, but the action unfolds vaguely and is hardly stirring. Is this how you earn a PG-13?

The Hong Kong way

Righting Wrongs (1986).

While revising Planet Hong Kong for its web edition, I’ve been revisiting classic Hong Kong action scenes. In 1997-98, when the book was written, I had to rely on laserdiscs, but since then I’ve been able to look at more 35mm prints. (DVDs usually don’t help answer the sort of questions I’m asking, for reasons reviewed here.) Now I have a chance to put some thoughts about these movies online, in this blog and in the upcoming digital update of the book. As a start, here’s a recipe drawn from the best of Hong Kong fury.

First, go for clarity in every way. Not murky earth-toned sets but brightly colored and sharply lit ones; even an alley can dazzle. Put the camera on a tripod; pan if you must, but save your dolly moves for simple emphasis. No handheld.

Second, aim for precision. Stallone’s comments imply that a cameraman captures a preexisting fight, snatching an “interesting” shot here or there. But that’s not the case. Movie action is choreographed and the framing is calibrated to that. The gestures should be legible, favoring crisp and staccato movement, while the image’s composition aims to convey the action cleanly. It’s a pity that the haphazard framing of Stallone and his cameramen have ruined the choreography of Cory Yuen Kwai, Jet Li’s action designer (and a fine director in his own right).

Third, establish a rhythm. This involves not only building the fight. It also involves synchronizing the pace of characters’ movements with that of the cutting. On the whole, the old rule applies: More distant shots should be held longer than closer ones. This doesn’t mean you can’t use fast cutting, only that your fast cutting can be more finely judged when you take shot scale, composition, and speed of movement into account.

Rhythm means sensing a pulse, and for that you need slight pauses. So don’t cut away to something else before a punch or kick is completed. Let the arc of movement, itself perhaps stretched over several shots, come to a point of rest, if only for a couple of frames.

Fourth—and here is where realism is most explicitly abandoned—amplify the expressive qualities of the action. If movement is zigzag or springy or oscillating, stress that. Give emotional qualities not only to facial expressions but also to postures and combat moves. American heroes just grimace while their bodies remain inexpressive, lumpish. The hard guys in The Expendables might as well be made of granite. But in contrast your fighters needn’t wave their arms wildly. Just concentrate energy and emotion in the action. If the hero attacks, let him become as focused as a javelin. If your heroine falls, don’t let her just drop out of frame: Let her land with a thwack, preferably on the spine or neck, and let her body’s recoil send a spasm through the spectator too.

Hong Kong cinema supports Sergei Eisenstein’s belief that expressive human action is “infectious.” He thought that if physical action onscreen is imbued with vivid force it can arouse sympathetic echoes in the spectator’s own body. After a great action scene, such as in many Chang Cheh and Lau Kar-leung films of the 1970s, or in Yuen Kwai’s Righting Wrongs, when a tough guy gets a spittoon in the face, the viewer feels trembling and tired, but in a good way.

Glass story

Jackie Chan has become such a beaming, easygoing star that we forget that he was an excellent director of brutal fight scenes. He proved adept at filling anamorphic compositions with dynamic movement, as well as plucking out items of a set and sweeping them into the action. (See the parlor fight in Young Master, 1980, or the shenanigans in the rope factory in Miracles/ Mr. Canton and Lady Rose, 1989). In Police Story (1985), Jackie is trying to rescue Salina and save all the computer records in her briefcase. Koo’s gang is determined to stop him. The fight moves through different areas of a shopping mall.

In each of these locales, Jackie plays a suite of variations on what you can do with escalators, staircases, and, most memorably, glass. I can’t do justice to all the skirmishes, but consider some instances of how he stages and cuts the action for an impact that American movies seldom achieve.

The variations get steadily more elaborate. Early in the sequence, Jackie flings one thug, achingly, across the bottom handrails of an escalator.

The shot could hardly be more legible. You see everything. Next, Jackie is grabbed from the rear.

Naturally he has to flip his attacker down to the floor below, rendered in two dynamic shots from directly below and above.

Interestingly, the shots are so clearly composed (even with the fancy mirror effect in the second) that they can be very brief: 26 frames and 16 frames. Down at the bottom, the unfortunate fellow smashes through a display and lands straight on his spine. Unlike the security guards in Tomorrow Never Dies, this thug gets a little commiseration as he rolls over groaning. As in any fight sequences, disposable thugs may come back into action, but at least we’ll clearly see the fates of those who are put permanently out of commission.

After this burst of action Jackie provides a pause as he abruptly looks up in search of Salina.

What else can you do with escalators? How about tossing the next thug down the slim gap between two of them?

In a nice touch, we hear a long squeak as he slides down the trough.

Tomorrow Never Dies sets up its conveyor-belt climax straightforwardly, but Jackie’s choreography is more surprising. Audacious and imaginative as the stunts are, however, they are framed and cut in a way that makes the action clear and precise. Through cinematic choices Chan builds up an infectious arousal. This stuff hurts.

After a set-to in a hallway, Jackie pursues the gang into an area filled with display cases. He takes on the men ferociously, and sets them smashing through the vitrines in another string of variations. Jackie slams down a mirror on one thug, swings another into a display, and sends one spinning through a window. Each shot, of course, is of diagrammatic simplicity, all the better to amplify the expressive dimension and key up the viewer. You can’t watch shots of men hurled into layers of glass without feeling a few palpitations.

Nearly every shot is bound tightly to the next. What will occupy shot B is launched on the fringes of shot A, sometimes for only a few frames. The string of matches on action creates a fluid continuity quite different from the choppiness we often find in American sequences.

A good instance occurs after Jackie has been pinned under a toppled shelf. In a medium close-up, the gang leader orders his thug into action; behind him the plaid-coated thug moves left.

In long shot, with Jackie at a disadvantage, the thug continues his movement in the background as he grabs a heavy statuette.

In a medium-shot, Mr. Plaid Jacket lifts the statue, but as he moves aside he reveals Salina rushing toward him in the background. Look quick: She appears in the fifteenth frame, and is gone within another fifteen.

We can only glimpse Salina passing behind the thug, but the next shot shows her clearly: running, baseball bat in hand, toward him. The trajectory could not be clearer, and she swings the bat directly through the vitrine.

The force of the action is multiplied by the simplest cut possible: an axial enlargement, with the action slightly repeated and slowed. The first shot of Salina’s swing lasts seventeen frames, the second exactly twice as long. The arithmetic of the cutting extends the action’s beat.

Bursts of glass form the dominant, painful motif of this part of the sequence. (Jackie’s crew suggested he call the film Glass Story.) The shifting dynamic of the fight is rendered through close encounters of the splintery kind. But these are differentiated. Long shots portray the torments of the gang, but Jackie’s first encounter with glass is treated in one simple close shot, just a second long, that usually makes audiences flinch.

Jackie is attacked by the gang leader and he shoves Salina out of the way.

The leader springs forward to whack Jackie with the briefcase.

Cut to the opposite angle, a tight shot of Jackie.

The briefcase continues to be swung, and Jackie’s head smashes the windowpane.

Jackie bounces off the glass and grimaces in agony.

The proximity of the glass shards to his eyes probably triggers some primal revulsion in us, but this is only part of the image’s force. The whole shot lasts only 28 frames. I think that part of its percussive impact comes from the fact that at the start we don’t have time to register that the pane is there. (There are only seven frames before Jackie hits.) When the glass bursts, it’s as startling as if the screen surface has cracked as well, and this amplifies the painful impact of the blow.

For a time Jackie is at the gang’s mercy. But he makes a comeback, and eventually in a kind of summary of his other maneuvers he will bash the leader, body and head, through two glass cases. This phase of the scene concludes with Jackie running Mr. Plaid through a series of cases at the point of a motorcycle. Both crescendos are filmed in clear, smoothly-cut shots—and long shots at that.

We may wince for the fate of these gangsters, but we shuddered when we saw Jackie’s face knocked through a window. Soon Jackie will be flipping the leader down an escalator, a sort of envoi to the scene’s first phase, and he will be sliding down a three-story light pole to catch up with boss Koo himself.

To use Stallone’s comparison, I’d happily hang this splendid sequence in the Louvre.

But what sort of MPAA rating would it receive today? The painful physicality on display is given a staccato force through the framing and cutting. And don’t call it cartoonish. It’s Bond who’s cartoonish, with his unflappable ease and perfectly functioning gadgets and defiance of the laws of gravity and those fights he wins without suffering a scratch. Jackie shows us the sweat. He and his victims fall with painful awkwardness, he gets gashed and bruised, and he’s all too vulnerable to physics (or at least Hong Kong physics). Bond wins through debonair resourcefulness and a lot of luck. Jackie wins by refusing to lose.

He refuses to lose the audience too. In Police Story Jackie’s manic urge to make the scene maximally gripping is itself a little scary. Nonetheless, when a director isn’t afraid of tapping the real power of movies, a fight scene can give us an adrenalin transfusion. Who needs 3-D? Maybe only weak directors.

For other discussions of Hong Kong action scenes, see my “Aesthetics in Action: Kung-Fu, Gunplay, and Cinematic Expression” and “Richness through Imperfection: King Hu and the Glimpse” in Poetics of Cinema. There are some other examples in my online essay on Shaw Brothers. My most ambitious efforts in this direction are in Planet Hong Kong, where I take up the issue of rhythm in more detail than I can here. Alas, many contemporary Hong Kong action scenes have learned bad habits from Hollywood. I’ll talk about the decline of crisp fight staging in the new edition of PHK, due online in early December.

Todd McCarthy’s 1998 review of Armageddon is here. Peter DeBruge’s review of The Expendables is here. Both may lurk behind a paywall. The coverage of The Expendables I mention is Michael Goldman, “War Horses,” American Cinematographer 91, 9 (November 2010), 52-56. The pilot online issue is here.

The Dragon Dynasty version of Police Story includes Bey Logan’s conversation with Brett Ratner. During the commentary, Ratner notes that Jackie holds his shots longer than would an American director, who would be likely to cut on every punch. Incidentally, I’ve found many DD releases of Hong Kong films to be superior in quality to other DVD versions, and Logan’s commentaries are information-packed. His book Hong Kong Action Cinema remains a fine piece of work.

The images from Tomorrow Never Dies are taken from DVD, with all the drawbacks of that format for close analysis. But I don’t think my conclusions would vary if I worked from 35mm. The Police Story frames are analog frame enlargements from a 35mm print and allow accurate frame-by-frame analysis. Even then, Jackie’s pacing is so fast that blurring is inevitable. Thanks to Heather Heckman for her assistance in turning my slides into digital files.

PS 17 September 2010: I forgot to mention that Matt Zoller Seitz has provided two of the most discerning (and hilarious) critiques of the Michael Bay High Rococo Action Style, here and here.

Young Master.