Archive for the 'Film technique: Editing' Category

Seed-beds of style

The Hunt for Red October.

DB here:

Seminar, orig. German (1889): A class that meets for systematic study under the direction of a teacher. From Latin seminarium, “seed-plot.”

I retired from full-time teaching in July of 2005. Since then, while writing and traveling (both chronicled on this website), I’ve done occasional lectures. But this fall I tried something else. At the invitation of Lea Jacobs here at Madison, I collaborated with her on a graduate seminar called Film Stylistics.

It was a good opportunity for me. I had a chance to learn from Lea, Ben Brewster, and the students and sitters-in. The class also enabled me to test and revise some ideas I’d already explored, while garnering new ideas and information. I helped plan the sessions and pick the films, but I had no responsibilities about grading. I hope, though, to read the students’ papers at some point after the term is over.

Our goal was to introduce students to studying style historically and conceptually. We focused on group styles rather than “authorial” ones because we wanted to explore particular concepts. How useful is the concept of group norms in understanding broad stylistic trends? Can we explain stylistic change through conceptions of progress toward some norm? Does the model of problem and solution help explain not only a particular innovation but also the group’s acceptance of it? How viable are notions of influence in explaining change? How much power should we assign to individual innovation? Can we think of filmmaking institutions as not only constraining style (through tradition and conformity) but also enabling certain possibilities—nudging filmmakers in certain directions? Does stylistic study favor a comparative method, one that encourages us to range across major and minor films, as well as different countries and periods?

These are pretty abstract questions, so we wanted some particular cases. Lea and I picked three areas of broad stylistic change: the emergence of widescreen cinema in the 1950s, the arrival of sync-sound filming in the late 1920s, and the development of analytical editing or “scene dissection” in the 1910s and 1920s. We tackled these areas in this order, violating chronology because we wanted to move from somewhat hard problems to the hardest of all: Why did filmmakers in the US, and soon in other countries, move toward what has become the lingua franca of film technique, continuity editing?

The results of our research on these matters will emerge over the next few years, I expect. In the short term, during my final lecture Tuesday I went off on what I hope wasn’t too much of a tangent. I got interested in one particular kind of cut, and it led me to see, once more, how different filmmaking traditions can make varying uses of apparently similar techniques.

More cutting remarks

My concern was the axial cut. That’s a cut that shifts the framing straight along the lens axis. Usually, the cut carries us “straight in” from a long shot to a closer view, but it can also cut “straight back” from a detail. What could be simpler? Yet such an almost primitive device harbors intriguing expressive possibilities.

Axial cuts aren’t all that common nowadays, I think. Today’s filmmakers prefer to change the angle when they cut to a closer or more distant setup. But such wasn’t the case in the cinema of the 1910s and 1920s.

In the heyday of tableau-based staging, 1908-1918 or so, filmmakers seldom cut into the scene at all. European directors especially tended to shape the development of the action by moving actors around the set, shifting them closer to the camera or farther away. The most common cuts were “inserts” of details, mostly printed matter (letters, telegrams) or a photograph. But when tableau scenes did cut into the players, the cuts tended to be axial: the framing moved straight in to enlarge a moment of performance. Here’s an instance from the 1916 Russian film Nelly Raintseva.

During the mid-1910s, American films moved away from the tableau style toward a more editing-driven technique. This approach often relied on more angled framing and a greater penetration of the playing space, of the kind we’re familiar with today. But axial cuts hung on in American films, even in quickly-cut scenes. Lea pointed out some nice examples in Wild and Woolly (1917), especially those involving movement. In the example below, the first cut carries us backward rather than forward, and the second is a cut-in, but both are along the lens axis.

During the 1920s, axial cuts become a secondary tool of the American filmmaker, who now had many other camera setups available. But Soviet filmmakers of the 1920s, who adopted many American techniques in the name of modernizing their cinema, seemed to see fresh possibilities in the axial cut. For instance, in Dovzhenko’s Arsenal (1929), it becomes a percussive accent. The astonishment of a bureaucrat under siege is conveyed by a string of very fast enlargements.

The Soviets called such cuts “concentration cuts,” a good term for the way they make a figure seem to pop out at us. From being a simple enlargement (in tableau cinema) or one among many methods of penetrating the scene’s space (in Hollywood continuity), the axial cut has been given a new force, thanks to adding more shots and making them quite brief.

This aggressive method for seizing our eye—Notice this now!—has appeared in modern filmmaking too, as in this passage from Die Hard (1988).

Here the axial cut is clearly subjective, rendering John McClane’s realization that he can use the Christmas wrapping tape in his combat with the thieves. Director John McTiernan employed the device again in The Hunt for Red October (1990). The frames surmounting this entry show the heroes suddenly being fired upon.

It seems likely that many modern directors became aware of this device from seeing Lydia’s discovery of the pecked-up body of farmer Dan in The Birds (1963). Hitchcock knew Soviet montage techniques, so maybe we have a chain of influence here. In any case, the somewhat overbearing aggressiveness of the concentration cut has often been parodied on The Simpsons. Here’s a recent example.

By the law of the camera axis

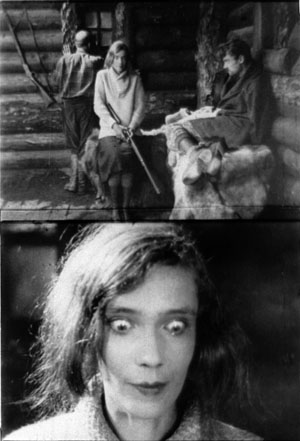

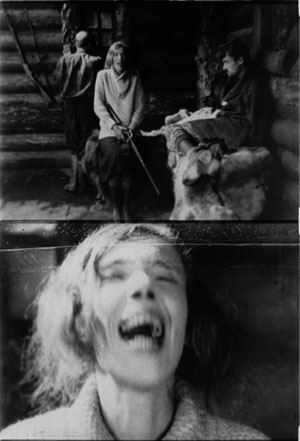

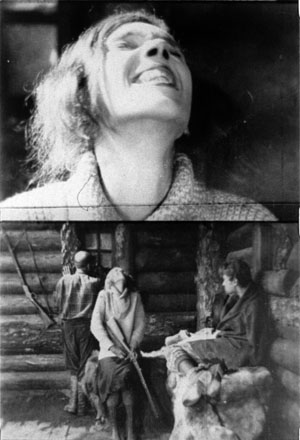

Axial cutting can be used more pervasively, as a structuring element for an entire scene. This is what Lev Kuleshov does in a climactic moment of By the Law (1926). Edith and her husband have kept the murderer at rifle point for days, and the strain is starting to show. She becomes hysterical, and Kuleshov uses a ragged rhythm of stasis and movement to convey it. First he cuts straight in from a master shot to a medium shot of her. I reproduce the frames from the film strip, for reasons that will become obvious.

Then Kuleshov cuts straight back to the master setup. Again he cuts in, but to a closer view of Edith as she becomes more frenzied.

Cut back once more to the long shot, but only for fourteen frames. That shot is interrupted by a shot of Edith already laughing crazily, her head tipped back.

The shot of her laugh lasts only five frames, and this mere glimpse, combined with the blatant mismatch of movement, makes the onset of her spell all the more startling. When we cut back to the long shot her face and position now match.

The abrupt quality of her outburst would not have been as striking if Kuleshov had varied his angle. As the earlier examples show, when only shot scale changes and angle remains the same, the cuts can be very harsh, and Kuleshov accentuates this quality with a flagrant mismatch.

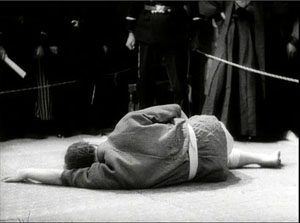

Akira Kurosawa likewise used the concentration cut to provide salient moments throughout his work; it almost became a stylistic fingerprint. At several points in Sugata Sanshiro (1943) he uses the device in the usual popping-forward way. But he varies it during Sanshiro’s combat with old Murai. He reserves dynamic, often elliptical cuts for moments of rapid action, and then he uses axial cuts for moments of stasis or highly repetitive maneuvers. In effect, the moments of peak action happen almost too quickly, while the moments of waiting are emphasized by cut-ins.

So at the start of the match, a series of axial cuts, linked by dissolves, present the fighters in a slow dance. But the ensuing throws are editing briskly. When old Murai is thrown and lies gasping on the mat, axial cuts accentuate his immobility. Kurosawa adds a rhythmic urgency on the soundtrack. After each cut-in, we hear the voice of Murai’s daughter, either offscreen or in his thoughts: “Father will win.” “Father will win.” “Father will surely win.”

The matching of lines to the editing is at work in the Simpsons parody too, in which the Comic Book Guy’s words are heard in tempo with the concentration cuts. “You. Are. Acceptable.”

Montage and the axial cut

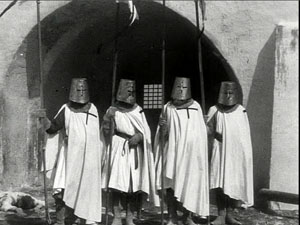

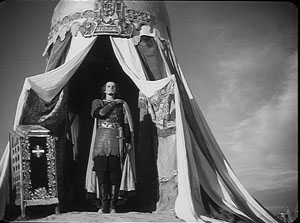

By now it’s easy for us to see that one scene from Alexander Nevsky (1938) opens with a series of axial cuts, out and in.

But why would Eisenstein, master of montage, regress to such a primitive device? He had occasionally used axial cuts in his silent films, as when we see Kerensky brooding in the Winter Palace in October (1928).

And Potemkin‘s famous cuts in to the Cossack slashing at the camera (that is, the baby, the old lady) are axial. (These cuts are pastiched by Eli Roth and Tarantino in Inglourious Basterds.) At the limit, Eisenstein toyed with the axial cut by moving the figures around during the shot change. In Potemkin, the ship’s officer reports to the captain that the crew has refused to eat. The captain leaves one shot and climbs the stair before Eisenstein cuts in to show him leaving again. The repetition would not be so perceptible if Eisenstein had varied the angle.

In the 1930s, Eisenstein began thinking about the axial cut as a basic structural element of a scene. In both his theory and practice, he promoted the axial cut to a level of prominence it hadn’t seen since the days of the tableau. Usually the cuts involve static subjects, like most of Kurosawa’s, but he still exploits the cut-ins to create vivid, if spatially impossible effects. At one point our popping in closer to Ivan the Terrible is doubled by him majestically and magically popping out of his tent to meet us, like a thrusting chess piece.

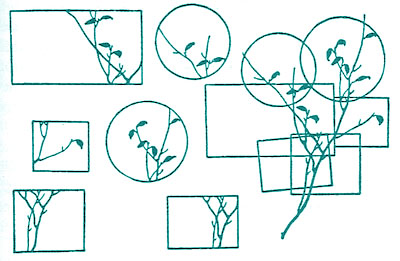

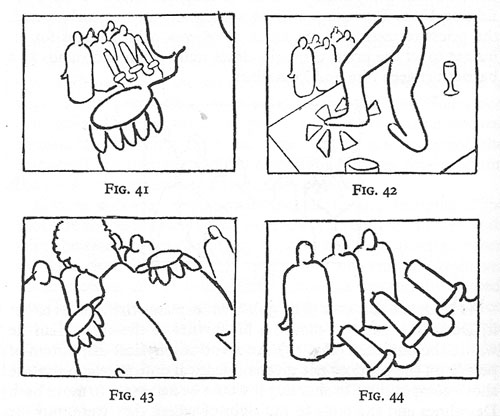

The new primacy of axial cutting comes from Eisenstein’s idea that “montage units” could powerfully organize the space of a scene. He thought that you could imagine filming a scene from only a few general positions, but then varying camera setups within each of these orientations. The montage unit was a cluster of framings taken from roughly the same orientation, as in the Pskov and Ivan scenes.

The idea may derive from his study of Japanese art, shown further above, in which he explored how a single image of a cherry branch could be chopped up into a great variety of compositions. In his course at the Soviet film school, he illustrated with a hypothetical scene of the Haitian revolutionary Dessalines holding his enemies at bay at a banquet. After imagining a master shot from the farthest-back position in the montage unit, Eisenstein proposes a series of dynamic closer views.

Eisenstein didn’t think that each scene had to be handled in a single montage unit. You could create two or three predominant orientations, with shots from each woven together. Or you could gain a sudden accent when a stream of setups from the same unit was interrupted by one from a very different angle. These ideas he put into practice throughout Nevsky and Ivan the Terrible.

Why? Eisenstein thought that combining shots taken from roughly the same orientation yielded a musical play between constant elements and variation. Each shot shows us something we’ve seen before but also something new, the way a bass line or sustained chords can continue underneath a changing melody. Eisenstein was convinced that this flowing weave of visual elements gave the spectator a deeper involvement in the film as it unfolded—an involvement akin to that found in Wagnerian opera.

The axial cut is a good example of how even a simple stylistic choice harbors rich creative possibilities. It also shows how a technique can change its impact in different filmmaking traditions. In the tableau tradition the axial cut was for the most part an abrupt enlargement heightening a moment of strong acting. In the early days of Hollywood continuity it became one editing option among many, and its power was somewhat muted. For the Soviets, concentration cuts could be multiplied and joined with fast cutting and big close-ups. The result could jolt the viewer by italicizing a face or an object–a purpose that has been taken up by contemporary Hollywood. For Kurosawa, the technique offered a way to contrast extreme movement and extreme stillness. And for Eisenstein, it suggested a global strategy for weaving visual elements into an immersive whole.

The protean functions assumed by this simple device remind us of how much there is yet to discover about film style. Despite all our discoveries over the last three decades, we have only begun. The name is apt: A seminar is where things start.

For more on the staging strategies of the tableau style, see On the History of Film Style and Figures Traced in Light: On Cinematic Staging, as well as blog entries here and here and here and here. You can find examples of emerging Hollywood continuity techniques in this entry on 1917 and this one on William S. Hart and this one on Doug Fairbanks. Sugata Sanshiro is at last available in a good DVD version from Criterion as part of its big Kurosawa box. Eisenstein’s ideas about the axial cut are explained in Vladimir Nizhny, Lessons with Eisenstein, trans. and ed. Ivor Montagu and Jay Leyda (New York: Hill and Wang, 1962), Chapters II and III. In The Cinema of Eisenstein I try to show how these ideas are employed in the Old Man’s late films.

Seated: Leslie Debauche, Lea Jacobs, Rebecca Genauer, Pam Reisel, Amanda McQueen. Standing: Karin Kolb, Andrea Comiskey, Ben Brewster, John Powers, Tristan Mentz, Heather Heckman, Aaron Granat, Jenny Oyallon-Koloski, Jonah Horwitz, and Booth Wilson. Evan Davis had to leave early.

Pierced by poetry

DB here:

If I had a time machine, I’d zip over to Japan between 1924 and 1940. I’d trade a year of my life here and now for a year there and then.

Why? First, because the world I see in the movies of that period holds an irresistible fascination for me. I’d like to walk through Ginza, take a train to a spa, wander through Asakusa, have tea at the Imperial Hotel, hike around the temples of Kyoto. Second, if I could go back, I could see all the films I will never see—the lost Ozus and Mizoguchis, of course, but also the films we don’t even know are important.

For Japanese cinema in the 1920s and 1930s was one of the triumphs of world cinema. That era produced not only the two directors who are arguably the very greatest but also a host of talents you can’t really call “lesser.” The bench had depth in every position.

There are good reasons for this burst of genius. Quantity affects quality, but not the way snobs think: The more movies a country makes, the more good ones you’re likely to get. Although Japan had only a little more than half the US population, before 1940 it turned out about as many features as America did.In 1936, both countries released about 530 domestic productions.

The Japanese directors who started in the 1920s had, like Ford and Walsh in their salad days, to feed this audience. We tend to forget that even exalted figures entered the industry as high-volume producers. Mizoguchi averaged about ten releases per year in his first three years, Ozu about six. Everyone’s pace slowed with the coming of sound, but the sheer volume of movies pouring from studios big and small reminds us that young directors had plenty of opportunities to hone their skills.

Probably the most startling instance is Shimizu Hiroshi. In a career that ran from 1924 to 1959, he’s credited with directing 163 films. The earliest one of his that I’ve seen is Seven Seas Part I; this 1931 feature was his seventy-fifth. “Next year,” he remarked in 1935, “I’m going to make only three films the way the company wants me to, and in exchange I can make two films that I want. I want a little more time. I’m too busy right now.” As things turned out, he signed seven films in 1936.

The great bulk of his work, 139 titles, falls before 1946. Fewer than two dozen of these seem to survive. With only about 17% of the films available, we have to keep our generalizations modest. Who knows what we would find in Love-Crazed Blade (1924) or Flaming Sky (1927) or Duck Woman (1929)? Shimizu contributed to a series, the “Boss’s Son” or “Young Master” films, of which only his first, The Boss’s Son at College (1933) seems to survive. What would we find in The Boss’s Son’s Youthful Innocence (1935) or The Boss’s Son Is a Millionaire (1936)?

Luckily, we’ve wound up with some extraordinary movies, not a clunker among the ones I’ve seen. If only a smattering of 1930s and 1940s titles is available, we should be happy that it was this smattering. Shimizu had concerns in common with Naruse Mikio and Ozu Yasujiro, but he established his own world, a rich tone, and a simple but subtle visual idiom. Along the way, he created some of the most heart-rending films in world cinema.

From the city to the spa

Shochiku talent at Izu hotspring, July 1928: Ozu Yasujiro (left), Shimizu Hiroshi (third from left), and screenwriters Fushimi Akira and Noda Kogo. Ozu and Shimizu were 23 years old.

Once more, all hail Criterion. TheTravels with Hiroshi Shimizu DVD collection released this spring includes Japanese Girls at the Harbor (1933), Mr. Thank You (1936), The Masseurs and a Woman (1938), and Ornamental Hairpin (1940). They were previously released on an expensive Japanese set (with English subtitles), but Criterion’s Eclipse series offers them at a more reasonable price, along with brief but helpful notes in English by Michael Koresky.

The collection’s title highlights the image of Shimizu that emerged in the 1980s. The films that struck Western critics then were typically shot outside the usual big cities (Tokyo, Kyoto, Osaka), in the mountains and seaside towns of the Izu peninsula. John Gillett’s 1988 National Film Theatre program, the first extensive survey of Shimizu’s work outside Japan, was entitled “Travelling Man.” Not only did Shimizu take his crew on the road, thanks to the expansion of the railway system, but he also exploited what became known as his signature technique: lengthy tracking shots down a road, following characters walking toward us.

Like Ozu, Shimizu worked in modern-day genres (gendai-geki), from slapstick comedies to college sports films. Most of what survives from before 1936 are social dramas of families, friendship, and fallen women. Seven Seas (1931-1932) deals with class conflicts, as a poor girl marries into a rich family and discovers that her husband is a bounder. Eclipse (1934) centers on the failure of young people from the countryside to succeed in a recession-hit Tokyo. The title of Hero of Tokyo (1935) is ironic, in that the stepson who abides by a mother held in disgrace by her other children, winds up destroying her last scrap of respectability. In Japanese Girls at the Harbor, two schoolgirls are driven apart by one’s passion for a young man. After a violent confrontation, she becomes a prostitute and her estranged friend winds up marrying him.

The Shochiku studio deliberately pursued a female market, and these tales of family intrigue and endlessly suffering mothers, wives, and daughters offer obvious figures of sympathy. Less predictably, the films simmer with criticism of modernizing Japan. They focus on the corruption of the upper classes, the collapse of traditions in the countryside, and the uprooting of the extended family.

Most significantly, Shimizu’s films indicate quite explicitly that Japan’s growing prosperity in the 1910s and 1920s was built on the backs of the rural poor, particularly the young women who flocked to textile mills, city shops, and brothels. Like many films of his contemporaries, Shimizu’s urban films mix sentiment and comedy with a harsh appraisal of social tendencies. I’d bet that we’d find both qualities in his Stekki garu (1929), a film apparently about the current craze for “walking stick girls,” women whom men hire to accompany them on strolls.

The manager Kido Shiro summed up the Shochiku spirit in the formula “smiles mixed with tears.” Ozu offered this blend in films like I Was Born, But… (1932) and Passing Fancy (1933), but there are precious few smiles in Shimizu’s surviving early thirties output. Then he took to the road.

In his films of travel Shimizu still offered social criticism, but he leavened it with off-center comedy. Indeed, he intensified Kido’s mandate: In Mr. Thank You, jaunty jazz and Latin American music accompany moments of sheer pathos. Now as well Shimizu’s intricate plotting, driven by the chance meetings and startling revelations of melodrama, could relax. Films like Mr. Thank You (1936), Star Athlete (1937), and The Masseurs and a Woman (1938) are expanded anecdotes, strings of situations that accumulate in casual fashion. Dramas emerge fleetingly, on the road or in hot-springs inns. The films tend to be brief, flowing toward abrupt, muted epiphanies in the manner of a short story. These movies make you ask whether 60-75 minutes might not be the ideal length for a movie.

In his films of travel Shimizu still offered social criticism, but he leavened it with off-center comedy. Indeed, he intensified Kido’s mandate: In Mr. Thank You, jaunty jazz and Latin American music accompany moments of sheer pathos. Now as well Shimizu’s intricate plotting, driven by the chance meetings and startling revelations of melodrama, could relax. Films like Mr. Thank You (1936), Star Athlete (1937), and The Masseurs and a Woman (1938) are expanded anecdotes, strings of situations that accumulate in casual fashion. Dramas emerge fleetingly, on the road or in hot-springs inns. The films tend to be brief, flowing toward abrupt, muted epiphanies in the manner of a short story. These movies make you ask whether 60-75 minutes might not be the ideal length for a movie.

The easygoing plots echo the movies’ production process. Shimizu wasn’t an obsessive planner. Whereas Ozu sketched every shot and checked the composition through the camera, Shimizu wrote minimal screenplays and seldom budged from his chair, even when the camera was traveling. He shot quickly, making up dialogue as needed and giving actors the most cursory direction imaginable. (“Run.”) Yet this wasn’t a high-pressure situation. Some days, uncertain about what to do, Shimizu would shut down the shoot and take people swimming.

Tears and smiles

I don’t want to leave the impression that Shimizu was careless; below I’ll try to show that he set himself some powerful storytelling problems. And his relaxed manner yielded a unique mixture of traditional drama and more vagrant appeals. Take Mr. Thank You, my pick for the crown of the Criterion set.

It’s a road movie, although the trip runs only twenty miles. A rickety bus winds through the mountains around the Kawazu region of Izu, an area of hot springs and tiny villages. The handsome, kindly young driver is known only as Mr. Thank You (Arigato-san) because whenever he forces walkers off the road he waves and calls his thanks. He has earned the devotion of people in the region, who entrust him with messages and duties on their behalf. On this particular day, his bus is carrying a stuffy real-estate agent; a wisecracking moga (modern girl); and a young girl whose mother is accompanying her to Tokyo, where she is to be sold into prostitution. Other passengers—wedding guests, lonely old men—get on and off in the course of the trip.

The bus stops often, and the encounters give us vignettes of the deteriorating life of the countryside. We hear of the magic attractions of Tokyo, reported by a prosperous woman about to get married. A Korean woman working on road construction asks Mr. Thank You to visit her parents’ grave, reminding us that this oppressed minority has contributed its sweat to the new Japan. Counterbalancing these stabs of pure feeling are simple running gags, such as one involving rude auto drivers who insist on passing the bus. And across the trip, the fate of the girl draws ever closer.

The moga (evidently a hooker) becomes our raisonneur, commenting on everyone’s motives, denouncing hypocrisies, flirting with Mr. Thank You, and eventually offering advice on how to save a life. Shimizu fills his film with talk and music, but in quieter moments imagery takes over: shimmering valleys below zigzag mountain roads, tunnels and forests and glimpses of steep paths along which road workers trudge. Within the bus, point-of-view is channeled fluidly. At one point we watch the moga watching the driver watching the girl. The climax of the action is simply omitted, yielding a quick, upbeat coda. In sum, Mr. Thank You radiates the cheerful, compassionate resilience of its namesake.

The mixture of tears and smiles is present as well in The Masseurs and a Woman. In Japan, blind people traditionally have taken up the trade of massage. So we start on the road, tracking back from two masseurs feeling their way along. The gags start immediately, with one praising the view, but poignancy comes just as fast: “It’s a great feeling to pass people who can see.” And again a gag undercuts it: “I bumped into some horses and dogs, though.” Shimizu sets up his brand of incidental suspense—uncertainty about matters of no dramatic moment—when the two begin to guess how many people are advancing to them. Eight and a half? We wait and, when the shot comes, we quickly count to check.

This seesawing between humor and pathos defines the tone of the whole film. Once the men arrive at the inn, we’re introduced to several guests, and a notably piecemeal plot: an aborted romance, a mysterious theft, and the attraction of one masseur toward an enigmatic woman. On the light side, students who tease the blind get extreme massage makeovers, reducing them to hobbling the next morning in a parody of the blind men’s halting gait. Shimizu assures their humiliation by head-on shots of modern girls hiking into the midst of them. And of course the blind-guy jokes multiply when several masseurs are trying to navigate a room or a street. Again, the film is over before you know it, leaving that Shimizu tang of chance encounters and what-if possibilities.

Blind masseurs play a minor role in another spa movie, Ornamental Hairpin (1941), but an almost-begun romance is there as well. Two women, Okiku and Emi, pass through an inn, and after they’ve left Emi’s hairpin jabs a young soldier’s foot. He will spend the rest of the story recovering his ability to walk. Emi returns to the inn and joins its summer guests: a cranky professor, a grandfather and his two pesky grandsons, and a married couple.

“Pierced by poetry,” says Nanmura casually about his wound, but the professor extrapolates on the phrase, trying to weave a romantic plot out of the accident. Shimizu declines to share the fantasy. A bit like Tati’s M. Hulot’s Holiday, the film is threaded with mundane vacation routines that become running gags, overwhelming what we expect to shape up as a courtship.

Bronzing in the sun and helping Nanmura recover his ability to walk, Emi comes to believe that she has found happiness. She has fled Tokyo and wants to start fresh. But her past, either as wife or kept woman, is kept vague. In two remarkable scenes, one a phone conversation and the other a dialogue with Okiku, her situation is sketched. We start to fear that her man will even come looking for her.

But these bits of conventional plotting are drop away among prolonged scenes of spa gossip and lazy pastimes. The most suspenseful sequences are devoted to Nanmura’s gradual recovery—a sort of deadline, since when he walks again, he will leave. If ever a climax refused to arrive, it’s during the last ten minutes or so of Ornamental Hairpin. The moments of pathos or conflict we would ordinarily see are skipped over, and the surroundings of “minor” scenes become infused with regret.

Shimizu’s ramblings through Izu didn’t lead him to abandon his probing of urban anomie, as we can see in Forget Love for Now (1937). (This must be one of the great Anglicized Japanese titles. I rank it with Blackmail Is My Life and Go, Go, Second-Time Virgin.) And at the same time he consolidated that talent for which he was best known in his lifetime: the exploration of childhood. Children in the Wind (1937), Four Seasons of Children (1939), and Introspection Tower (1941) offer unsentimental portrayal of boys’ rituals and their tenacity in the face of hardship. Shimizu founded an orphanage after the war, and he employed some of his charges in postwar films like Children of the Beehive (1948). Shochiku’s second boxed set, also with English subtitles, gives us the first three I’ve mentioned, plus the schoolteacher drama Nobuko (1940).

East meets West, and North meets South

Ornamental Hairpin.

Japanese film studios differed from their American counterparts in encouraging directors to cultivate individual styles. Kido supposedly fired Naruse by saying, “We don’t need two Ozus.” While Shimizu is not as daring or meticulous a stylist as Ozu, he managed to cultivate a visual approach that, however straightforward, was capable of delicate refinements.

In general, the Shimizus we have conform to trends in Japanese films of his period. His silent films from the years 1931-1935 adhere broadly to the Shochiku house style, using plenty of cuts and single framings of individuals. Most of the surviving silents have average shot lengths between 5 and 6 seconds, completely normal for both Japanese and US silent movies.

More remarkable is the number of dialogue titles, which make up between 24% and 44% of all shots. This would be exceptional for an American film of the 1920s. Other Japanese films, particularly Mizoguchi’s, are heavy with intertitles, but Shimizu took the trend somewhat farther. The preponderance of dialogue titles may owe something to the presence of both American and a few Japanese talking pictures at the time, which justified more spoken lines. In addition, at this period the influence of the benshi, the vocal accompanist to silent films, was waning, and the movies were becoming more self-sufficient in their narration. The hundreds of titles flashing by in Shimizu’s films would specify the scene’s action and curb the benshi’s urge to improvise.

Shimizu’s silent films that survive also contain several instances of a technique I’ve called the “dissolve in place.” The camera setup remains fixed, but one or more dissolves convey the changes in the space across a period of time. It’s commonly used to show long periods; in A Hero of Tokyo, the family’s growing poverty is shown through dissolves that gradually remove the furniture they’re been forced to sell. The technique can be seen in American silent films, a major source for most Japanese directors. Here’s a lovely example from Frank Borzage’s Lucky Star (1929), as the partly paralyzed Tim struggles to climb onto his crutches.

Shimizu often goes a little further by matching the figures precisely across a dissolve. In The Boss’s Son at College, the hero comes home but then sneaks out in his bare feet, and the dissolves concentrate on the reversal of movement, first upstairs, then down.

Again, this device was used by other Japanese directors, even Ozu in some early works, but Shimizu seems to have clung to it longer than most.

In general, Shimizu’s silent films don’t borrow his pal Ozu’s more idiosyncratic techniques. Shimizu doesn’t employ intermediate spaces to link scenes, or create elaborately disruptive transitions, or embed characters in 360-degree shooting space. Sometimes he offers mismatched eyelines in reverse shots, but these don’t usually cultivate the graphically exact alignment we find in Ozu’s editing. Still, Shimizu does often construct a scene’s space in a distinctive way.

For one thing, he will stage many scenes in long shot or even extreme long shot. Within that sort of shot, he’s often drawn to deep perspective, often with a central vanishing point. This is most apparent as a visual motif throughout The Boss’s Son at College.

More interestingly, his fascination with perpendicular depth governs staging and cutting. Imagine a line stretched straight out from the camera lens. By 1935 this lens axis has become Shimizu’s lifeline, his equivalent of the surveyor’s level. Rather than filling the foreground with a big figure or a face or prop, and rather than spreading his depth items wide across the background, he will pack the most important people along the center axis, like crystals growing out from a string. Here are instances from Japanese Girls at the Harbor and Eclipse.

Shimizu’s co-workers have testified that he cared little for the 180-degree rule. Like many Japanese filmmakers, he played fast and loose with it. Instead of an axis running between the characters, he was more concerned with the axis of the lens itself. He often respects that by cutting from one shot to a point (along the axis) 180 degrees opposite.

He also respects the lens axis by cutting straight in and out. In Hero of Tokyo, the mother learns that her husband has pulled a swindle and fled; then the officials leave her alone with her children. Shimizu simply enlarges and shrinks her systematically along the axis. He takes us to the other side of the group for the climax, when her birth children pull away from her stepson. We see no other camera positions in the scene.

This patterning is less abrasive than it might appear because intertitles are sandwiched in among these shots. It’s an intriguing strategy for thrifty filmmaking, since it requires only a rudimentary set, but it also offers a simple way to inflect the drama. Similar axial cuts, though not cushioned by titles, can be found in the shooting scene of Japanese Girls at the Harbor (which may owe something to French and Soviet cutting experiments of the period).

The depth stretching out from the camera lens is crosscut by another plane, perpendicular to it. This plane is often a patterned surface—windows, grillwork, a bedstead. Again, instead of Mizoguchi’s or Ozu’s angular foregrounds, we have an east-west axis slicing through the shot. The frames become boxes, and the characters play out their dramas within the cells of a grid, as in Seven Seas Part II and Japanese Girls at the Port.

Here again, Shimizu is relying on a device that other directors were using at the time. Many compositions of the 1930s play peekaboo with characters and setting. Here’s a flamboyant example from First Steps Ashore (Shimazu Yasujiro, 1932).

So instead of defining space through exaggerated foregrounds, plunging diagonals, or curvilinear edges, Shimizu goes Cartesian on us. His most distinctive layouts rely on two dimensions, one running straight into depth, the other running left to right. The result is a discreet, foursquare style well-suited to concise storytelling (and presumably, to turning out films quickly). Shimizu’s peers indulged in flashier shots, but his persistent choices yield a quiet variant of that continuity system that was already the lingua franca of world cinema.

Hitting the road

What about the sound films? Many Shimizu films still rely on distant planes of depth, as in this shot from Children of the Wind, when, after the father’s arrest, the boys’ buddies arrive at a far-off vantage point.

Interiors will sometimes be given the axial-cutting treatment, as in this passage from Ornamental Hairpin.

And now the crosscut horizontal plane often gets actualized as rooms gliding by the lens in lateral tracking shots. But in general, interior scenes in this 1941 film aren’t as strictly organized as in the silent films. This corresponds to a general move toward more orthodox technique in Japanese films of the period.

Something more original happens in the outdoor traveling shots. Now Shimizu’s beloved camera axis finds tangible expression in the highway. His much-vaunted tracking shots up and down the road translate the silent films’ axial depth into forward and backward movement, and characters, again organized in relation to the axis, are presented with a new simplicity and directness. Rather than being a one-off device, the road shots seem to be a development of the Cartesian coordinates that Shimizu has experimented with in the interior spaces of his silent films.

Star Athlete offers some remarkable examples of the push-pull effects built around the axis—tracking back from advancing characters, or tracking toward retreating ones. But Shimizu’s most thoroughgoing exploration of the camera axis in transit takes place in Mr. Thank You. The first thirteen shots lay out a stylistic matrix, with variants dropped in to prepare us for more compact expression later.

Shot 1: A long shot of the bus approaching.

Shots 2-4: We get the bus’s point of view of the road, with road workers in view; head-on shot of the driver calling “Thank you!” as the men step back; and the bus’s pov of the road receding, with the workers resuming. Dissolve to:

Shots 5-7: Bus’s pov of horsecart ahead; reverse angle of driver calling, “Thank you!”; bus’s pov of cart receding. Dissolve to:

Shots 8-9: Bus’s pov of men toting wood; we hear, “Thank you!” as we dissolve to bus’s pov of men receding. Dissolve to:

Shots 10-11: Bus’s pov of women carrying bundles; we hear, “Thank you!” as we dissolve to bus’s pov of women receding. Dissolve to:

Shot 12: Bus’s pov of chickens in road. They scatter as we get closer.

Shot 13: Long shot of bus going into the distance as we hear, “Thank you!”

The cycles move from three-shot clusters to two-shot clusters to a single shot, and a gag at that. (This driver even thanks poultry for traffic courtesy.) As another touch, Shimizu’s prized dissolves-in-place are recalled when the pedestrians approached from the back transform themselves into figures dwindling into the distance.

The same insistence on rectilinear framing takes place on the bus. Using 180-degree reversals, Shimizu creates a remarkable variety of shot scales in the cramped space of a real vehicle, always obeying his self-imposed geometry–facing either forward or backward.

As the trip gains emotional intensity, Shimizu will vary his treatment of these principles. For example, the middle section’s emphasis on forward movement will be counterbalanced near the end by a string of shots of passengers already off the bus, passing into the distance as we roll away.

In Shimizu, compact storytelling is matched by a pictorial strictness that doesn’t seem forced or stiff. After all, people do tend to line up to face one another in depth, and roads and buses do seem to run in two directions. Poetry in language demands strictures of meter, rhythm, rime, and the like, for these can pressurize expressive energies. Shimizu’s films present a disciplined lyricism: powerfully oblique emotions are shaped by simple but rich techniques of storytelling and style.

Most of my information about Shimizu’s work habits comes from essays and interviews in Shimizu Hiroshi: 101st Anniversary, ed. Li Cheuk-to (Hong Kong: Hong Kong International Film Festival, 2004). For more on Shimizu’s surviving silent films, see William Drew’s penetrating essay in Midnight Eye. Alexander Jacoby offers a sympathetic career overview atSenses of Cinema. For a filmography, see Jacoby’s A Critical Handbook of Japanese Film Directors: From the Silent Era to the Present Day Stone Bridge, 2008). Isolde Standish reviews Shochiku’s studio policies in Chapter 1 of her A New History of Japanese Cinema: A Century of Narrative Film (Continuum, 2005).

Noël Burch was one of the first Western writers to appreciate Shimizu’s artistry. His indispensible 1979 book To the Distant Observer: Form and Meaning in the Japanese Cinema is available in its entirety here. The Shimizu chapter, concentrating mainly on Star Athlete, starts here. I offer discussions of stylistic trends in Japanese cinema in Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema (Princeton University Press, 1988), available in toto here, and in two essays in Poetics of Cinema (Routledge, 2008), 337-395.

You can find passionate conversations about Shimizu and the release of these DVDs at the Criterion Forum. See especially the comments of Michael Kerpan.

Happy birthday, Film Workshop

Tsui Hark is the mad genius of Hong Kong cinema. The problem comes with assigning proportions. 10 % mad, 90% genius? 50-50? 99 % mad, 1 % genius?

Across a career that’s lasted more than thirty years, Tsui has had more ups and downs than the local economy. On the twenty-fifth anniversary of Film Workshop, the company he founded, the Hong Kong International Film Festival mounted a tribute. That provides an occasion to examine what he did and didn’t accomplish.

25 years old, but who’s counting?

Nansun Shi and Tsui Hark.

At this year’s Asian Film Awards, Film Workshop was given a special prize for outstanding achievement. On another evening there was a party gathering many Workshop alumi, from which the above photo comes. You can see more pictures from that party here. At the agnes b. gallery, a small show featured posters, a looped video documentary, a photocopy of the Better Tomorrow script, and some memorable props.

Nat Olsen has other pictures at his lively Hong Kong Hustle site.

The catalogue, A Tribute to Romantic Visions: 25th Anniversary of Film Workshop, is a must for all aficionados of Hong Kong film. Consisting largely of interviews, it offers many glimpses of creative choices and business strategies governing the company. Nansun Shi, Tsui’s partner and business manager, recalls how they placed films in overseas markets and won critical acclaim in Europe. She also explains matter-of-factly how frantic the midnight-show system was. In those days, Hong Kong filmmakers test-screened a movie to a midnight audience, and then reedited the film based on perceived reaction. Shi explains:

The catalogue, A Tribute to Romantic Visions: 25th Anniversary of Film Workshop, is a must for all aficionados of Hong Kong film. Consisting largely of interviews, it offers many glimpses of creative choices and business strategies governing the company. Nansun Shi, Tsui’s partner and business manager, recalls how they placed films in overseas markets and won critical acclaim in Europe. She also explains matter-of-factly how frantic the midnight-show system was. In those days, Hong Kong filmmakers test-screened a movie to a midnight audience, and then reedited the film based on perceived reaction. Shi explains:

Cinemas often wondered what could be done to a film in the eight hours between the midnight show and the day-time show the next day. I ran some calculation with the technicians: what is the least amount of time for them to do this and that, and then sent them to the cinemas to do the work. If worse comes to worst, they could do the re-editing when the show was running (80).

There isn’t much sugar-coating in the interviews. Collaborators often found Tsui a harsh taskmaster. At peak pressure, he seldom halted shooting for sleep and instead took cat naps on the set. Those who couldn’t keep up his pace, or adjust to his demands, left the company. There are also some comments on production practices. Herman Yau, for instance, notes: “Directors, in general, use most of the shots to tell the story. Tsui prefers images that look good on their own” (121).

Overall, the catalogue confirms that what started as a “workshop” designed to enable directors to realize individual creative visions became a company built around Tsui’s restless ideas about cinema. This was more or less the premise of the panel on Friday afternoon. Two critics, Keeto Lam and Longtin, discussed the Film Workshop enterprise largely as an extension of Tsui’s interests. Keeto had been a screenwriter at the company and shared information about the making of A Chinese Ghost Story 2, while Longtin speculated on Tsui’s interest in transcending polarities, particularly those between human and demon and male and female. Another scriptwriter was in the audience and contributed information as well.

One of Keeto’s points set me thinking. Having characterized Leslie Cheung as the “Golden Boy” of Film Workshop, he asked who the Golden Girl was, and he and audience members discussed candidates for the honor. (My vote, obviously, would go to Brigitte Lin.) But I began to speculate that one of Film Workshop’s main contributions was in star-making. Tsui has mentioned that his early films with gorgeous women tried to create a “comedy of pretty faces” opposed to the “comedy of ugly faces” that ruled in the 1970s and early 1980s. (Think of Michael and Ricky Hui, Karl Maka, Jackie Chan, and Sammo Hung.) By coaxing Brigitte Lin to Hong Kong and by giving Sally Yeh, Leslie Cheung, Chow Yun-fat, and other younger players big roles, Film Workshop created a new generation of glamorous stars.

A better yesterday

This celebration comes at a parlous period in Tsui’s career. Over the last dozen years Tsui directed some weak, even awful movies. Granted, even a bad Tsui movie is bad in a unique way, but that doesn’t make Tri-Star (1996), the Van Damme outings (Double Team, 1997; Knock Off, 1998), and The Legend of Zu (2001) any better. Some films he has produced, like Era of Vampires (2002) and Xanda (2003), are best forgotten. Today, after the only moderate success of Seven Swords (2008) and the disappointments Missing (2008) and All About Women (2008), many local film professionals consider him a spent force.

I’d argue that Tsui and Jackie Chan were the two most ambitious young filmmakers of 1980s Hong Kong. Tsui was the more daring and mercurial; he seemed to be trying a dozen things at once. He made some bad films, but others changed the face of local film: Shanghai Blues (1984), Peking Opera Blues (1986), A Better Tomorrow III (1989), Once Upon a Time in China I and II (1991, 1992), The East Is Red (1993), and The Chinese Feast and The Blade (both 1995). He also produced, and often co-directed, A Chinese Ghost Story and A Better Tomorrow (both 1986), The Big Heat and Gun Men (1988), The Killer (1989), the demented Wicked City (1992), and Iron Monkey (1993). These films had enormous impact locally, and they made Hong Kong film a major force in world cinema.

The problem is the mad-genius thing. Tsui is uneven, not only from film to film but within each one. Tsui can create a fairly unified tone, as The Blade and Seven Swords show. But more likely a Tsui film will contain something brilliant, something banal, something silly, and something just weird. Labored facetiousness is a virus plaguing Hong Kong film generally, but Tsui seems entirely too fond of bursts of dumb comedy. He replies: “Sometimes it’s fun to be stupid.”

Yet the thrown-together quality of many of his movies also means that even a troublesome one is likely to have a passable sequence. More important, his best films use the lurches in tone to create a grotesque, sweeping verve. Things happen so fast you can’t protest; either go with it or walk out.

Tsui’s strategy is based upon a breathless rhythm. He chops off scenes without warning, and he bustles his actors around the set maniacally; the poor things seldom rest long. Almost never do characters simply sit down and talk to one another, as in those bland American indie films. The beginning of Triangle (2007) shows how nervous, even opaque, Tsui’s style becomes when characters have to sit still.

For Tsui, story action is a matter of physical movement, and the film frame becomes a force-field, with actors popping in and out with abandon. He carries the staccato choreography of martial-arts film down to the most straightforward dramatic scene. He’s not alone in this; you can find it in the 1980s martial-arts films too, but Tsui gives it a special force with his pitched angles, his wide-angle lenses, and his love of comic-book-rococo compositions. Try, for instance, this shot of a woman getting an injection in Missing.

Such images can seem merely cheap flash, but what saves the best ones from preciosity is their constant but disciplined rhythm. In Once Upon a Time in China, Wong Fei-hung is about to be arrested after a clash with local thugs. The shot starts with the police official pointing his pistol to Wong’s head.

Another cop comes in to tell the official that the invaders left something. Any other director would have shown the cop’s face, but why? He’s important only to get the official out of the frame, so he becomes just a red hat poking in from the lower right corner.

The official dodges out, moving rightward across the frame.

There’s a pause, then Wong, now isolated in the shot, snaps his head around to follow what’s happening.

Tsui isn’t usually considered an economical director, but it’s hard to imagine a more crisp way to handle this routine bit of action. The shot takes less than eight seconds.

The same restless energy rules Tsui’s cutting, which has a punch and recoil derived, I think, partly from New Hollywood (Spielberg especially; see the Jaws example here) and partly from the local martial arts tradition. (Some proto-Tsui cutting is on display in Lau Kar-leung’s Legendary Weapons of China, 1982.) Watching Once Upon a Time in China at the retrospective, I was reminded that Tsui not only cooks up sequences that you can’t forget (three words: fight on ladders), but he risks audacious cuts on movement that few contemporary directors could bring off. When he wants to emphasize a moment, he channels Eisenstein. During the final combat of Wong and Iron Robe Yim, the iron weight sliding down the platform gets the Potemkin treatment. Four shots stretch out the instant through overlapping movement.

As we might expect, Tsui goes beyond Eisenstein by accentuating major points of impact with swift camera movements forward.

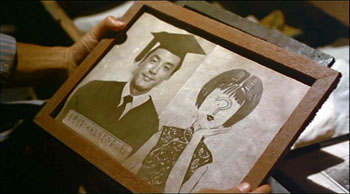

Tsui thinks visually. True, some sound is important—he is a master at merging music and image—but words are a last resort. He has been known to change dialogue in post-production so radically that the dubbing doesn’t match the actors’ lip movements. Shooting without sound gives Tsui, like other Hong Kong directors, a freedom of camera placement that recalls the silent cinema. And like a silent director, he thinks that every story point needs to be pictured. Kenny Bee is looking for the girl he met years ago (Shanghai Blues)? So let’s have an image that dramatizes the problem.

The inclusion of Kenny’s graduation picture might seem superfluous, but it makes the frame an anticipatory wedding picture, and it gives us a sense of his pure, if naïve, romantic impulses.

Motion plus or minus emotion

Shanghai Blues.

If you disapprove of what Spielberg and Lucas did to the American cinema, you will hate Tsui’s love of remakes, sequels, and spinoffs, his frequent confusion of SPFX with imagination, and his efforts to milk franchises to a point that can be considered cynical. Yet historically, he pushed Hong Kong cinema forward.

Before the star-making efforts I’ve already mentioned, indeed before Film Workshop was created, Tsui’s Dangerous Encounters: First Kind (1980) offered a blistering attack on class disparity in Hong Kong. He updated Cantonese fantasy swordplay in Zu: Warriors from the Magic Mountain (1983), and he tried his hand at a local version of low-budget exploitation in We’re Going to Eat You (1980). Keeto’s catalogue essay argues that Film Workshop pioneered six new genres in Hong Kong film, from comic-book adaptations to science-fiction and animation. And there’s more variety than we might expect. Film Workshop directors might have sometimes mimicked his style, but John Woo’s Workshop projects managed to do something quite different. Despite Tsui’s hands-on involvement, the lyrical Iron Monkey and the more hard-edged Gun Men and The Big Heat avoid the eccentricities of his signed work while maintaining his love of flamboyant set-pieces and visual creativity.

Tsui’s scripts often seem like patchwork, granted, but I tried to show in Planet Hong Kong that the episodic, additive plotline is a convention of Hong Kong cinema. Tsui—like Wong Kar-wai, though in a different key—took advantage of this formula to explore the power of the arresting image and an infectious rhythm. (You might say that Wong’s rhythm is that of cool jazz, while Tsui’s is closer to the percussiveness of Chinese opera.) Shanghai Blues and Peking Opera Blues, two of Tsui’s most ingratiating movies, jump smartly from one thrusting scene to the next, shifting emotional registers with dazzling speed. These movies can turn on a dime.

Tsui’s scripts often seem like patchwork, granted, but I tried to show in Planet Hong Kong that the episodic, additive plotline is a convention of Hong Kong cinema. Tsui—like Wong Kar-wai, though in a different key—took advantage of this formula to explore the power of the arresting image and an infectious rhythm. (You might say that Wong’s rhythm is that of cool jazz, while Tsui’s is closer to the percussiveness of Chinese opera.) Shanghai Blues and Peking Opera Blues, two of Tsui’s most ingratiating movies, jump smartly from one thrusting scene to the next, shifting emotional registers with dazzling speed. These movies can turn on a dime.

Part of what pulls us along is characters we care about—especially strong women. In the old days, we Hong Kong fans used to love the idea that John Woo, carrying on the Chang Cheh tradition, specialized in the sorrows of masculine obligation, while Tsui was much more interested in women. He gave us the comedy of pretty faces, the wide-eyed innocence of Joey Wong, and the severe beauty of Brigitte Lin who, in the final installment of the Swordsman series, becomes a sheer force of nature. (Her bi-gendered role in Ashes of Time stems from Tsui’s creation of her as such in Swordsman II and The East Is Red.) When Tsui took over the Better Tomorrow franchise, his prequel showed that Woo’s ideal hero Mark (Chow Yun-fat) learned his combat crafts from, of all people, a woman. Even the non-stop testosterone fervor of The Blade, all sweaty torsos and clanking weaponry, may be the hallucination of a madwoman.

These were rousing yarns. Yet at some point, I think, Tsui lost interest in telling a story. This tendency can be detected already in the Van Damme projects; the opening of Knock Off revels in visual effects (microscopic close-ups of the ripping fibers inside running shoes) but doesn’t dwell on what we need to know. Tsui’s task in the collaborative film Triangle was to simply to set up the premises of the action, but dialogue-driven exposition seems to bore him, and the opening scene is a frenzy of eccentric angles and barely registered plot points. His SPFX extravaganza The Legend of Zu has a fairly incomprehensible story to begin with, but by swamping it in explosions and magical transformations, Tsui makes a movie that is, like Spinal Tap’s amplifier knob, permanently set at 11.

With the lack of interest in economical storytelling comes a resistance to emotional engagement. Time and Tide has some virtuoso passages—the tenement sniping, the finale in Kowloon Station (with a woman giving birth during a gun battle)—but the film’s jittery momentum and lack of a coherent point of view sacrifice everything to momentary visceral impact. The death of a little boy caught in the crossfire is not a stab of pathos but the pretext for the visual shock of a ricocheting skateboard.

Tsui’s first films often shied away from sustained romantic scenes, a point made by Sylvia Chang in a catalogue interview. Still, he sometimes translated the awkwardness of love into gesture and motion, from the race to the train at the end of Shanghai Blues to the tender exchange of morsels of food between reconciled husband and wife in The Chinese Feast. Even Once Upon a Time in China can pause for a moment to let Aunt Yee reveal her growing affection for Wong Fei-Hong by having her shadow stroke his.

In the early FW films, emotion was translated into movements large or small. Losing her love makes a woman turn abruptly and snap out her cape, underneath a billboard advertising her lover’s song. But more recently Tsui seems to suffocate emotion in a welter of one-off effects. The lustrous HD shots of Missing make it visually striking, but the lacquered technique doesn’t seem to me to serve the story’s core drama of loss.

We can’t write Tsui off. He’s not yet sixty, and his new project, the Tang era mystery Detective Dee, sounds promising. Whatever happens next, his many admirers thank him and the FW team for some of the most radiant moments in modern cinema. Everyone who has seen Shanghai Blues needs only the stills at the top and bottom of this entry to conjure up the scene: Kenny plays his violin on the rooftop, we hear the soaring tune “Shanghai Nights,” and as we see Sally listening on another balcony, a chill goes up your spine. A little mad, but mostly genius.

Thanks to Alvin Tse for the illustration from the Film Workshop party.

The movie looks back at us

DB, still at the Hong Kong International Film Festival:

Abbas Kiarostami has the widest octave range of any filmmaker I know.

His humane dramas of Iranian life, from The Traveller to The Wind Will Carry Us, have justly won acclaim on the arthouse circuit. He has written scripts as well, some—like the under-seen The Journey (1994)—that are as compelling as a psychological thriller. He can conjure suspense out of the simplest acts, such as whether an adult will rip up a child’s copybook (Where Is the Friend’s Home?) or whether a four-year-old boy locked in with his baby brother can figure out how to turn off a stove (The Key). Indeed, I think that one of the great accomplishments of much modern Iranian cinema, with Kiarostomi in the vanguard, has been to reintroduce classic dramatic suspense into arthouse moviemaking.

But at times Kiarostami has moved to an opposite pole, that of extreme minimalism and “dedramatization.” The drift toward a hard-edged structure was there in Ten (2002), which gave us one of his drive-through dramas—people conversing in the front seat of a car—but in severe permutational form (different drivers, different passengers). Rigor was pushed to an extreme in Five Dedicated to Ozu (2003): Five lengthy shots of water landscapes, each many minutes long, taken at different times of day. The biggest dramatic action was the ducks walking through the frame. With Kiarostami, it seems, we cinephiles can have it all—Hitchcock and James Benning in the same filmmaker.

Now Shirin (aka My Sweet Shirin, 2008) marks another highly original exploration. I don’t expect to see a better film for quite some time.

After a credit sequence presenting the classic tale Khosrow and Shirin in a swift series of drawings, the film severs sound from image. What we hear over the next 85 minutes is an enactment of the tale, with actors, music, and effects. But we don’t see it at all. What we see are about 200 shots of female viewers, usually in single close-ups, with occasionally some men visible behind or on the screen edge. The women are looking more or less straight at the camera, and we infer that they’re reacting to the drama as we hear it.

That’s it. The closest analogy is probably to the celebrated sequence in Vivre sa vie, in which the prostitute played by Anna Karina weeps while watching La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc. Come to think of it, the really close analogy is Dreyer’s film itself, which almost never presents Jeanne and her judges in the same shot, locking her into a suffocating zone of her own.

Of course things aren’t as simple as I’ve suggested. For one thing, what is the nature of this spectacle? Is it a play? The thunderous sound effects, sweeping score, and close miking of the actors don’t suggest a theatrical production. So is it a film? True, some light spatters on the edge of the women’s chadors, as if from a projector behind them, but no light seems to be reflected from the screen. In any case, what’s the source of the occasional dripping water we hear from the right sound channel? The tale is derealized but it remains as vivid on the soundtrack as the faces are on the image track. What the women watch is, it seems, a composite, neither theatrical nor cinematic—a heightened idea of an audiovisual spectacle.

Moreover, there are the faces. We see some more than once, but new ones are introduced throughout. Spatially, they float pretty free; only occasionally do we get a sense of where the women are sitting in relation to one another. All are stunningly beautiful, whether young or old. We get an encyclopedia of expressions—neutral, alert, concentrated, bemused, amused, pained, anxious. During a battle scene, faces turn away, eyes lower, and hands shift nervously. The best person to review this movie is probably Paul Ekman, world expert on the nuances of facial signaling.

The weeping starts, by my count, about thirty-eight minutes in, during a rain scene uniting the two lovers Shirin and Khosrow. Thereafter, tears run down cheeks, along jaws and mouths, down necks and nostrils. The film is an almost absurdly pure experiment in facial empathy. It arouses us us by our sense of the story unfolding elsewhere, somewhere behind us, enhanced by lyrical vocalise and brusque sound effects, but above all by these eloquent expressions. It’s a feast for our mirror neurons. If you’re interested in reaction shots, you have to recall Dreyer remarking that “The human face is a landscape that you can never tire of exploring.”

I once asked Kiarostami how he got the remarkable performances in shot/ reverse-shot that we see in films like Through the Olive Trees and The Taste of Cherry. He said that he simply filmed one actor saying all his lines and giving all his reactions, then filmed the other. Often the two actors were never present at the same time, especially when he shot the car sequences. This montage-based approach, creating a synthetic space simply by cutting, has been taken to an extreme in Shirin, where the soundtrack supplies the reverse shot we never see. We’re told that Kiarostami filmed his female actors here reacting to dots on a board above the camera! Indeed, Kiarostami claims he decided on the Shirin story after filming the faces. Despite that, Shirin becomes one of the great ensemble pieces of screen acting, although the actors almost never share a real time and space. (Take that, green-screen wizards!) Like Godard, Kiarostami has been busy reinventing the Kuleshov effect (perhaps by way of Bresson).

This catalogue of female reactions to a tale of spiritual love reminds us that for all the centrality of men to his cinema, Kiarostami has also portrayed Iranian women as decisive, if sometimes mysterious, individuals. Women stubbornly go their own way in Through the Olive Trees and Ten. The premises of Shirin were sketched in his short, “Where Is My Romeo?” in Chacun son cinema (2007), in which women watch a screening of Romeo and Juliet. But the sentiments of that episode are given a dose of stringency here, particularly in one line Shirin utters: “Damn this man’s game that they call love!”

One last note: Kiarostami built movie production into the plot of Through the Olive Trees. Now he has given us the first fiction film I know about the reception of a movie, or at least a heightened idea of a movie. What we see, in all these concerned, fascinated faces and hands that flutter to the face, is what we spectators look like—from the point of view of a film.

For more on the production background, see the lengthy interview with Kiarostami here.