Archive for the 'Film technique: Editing' Category

1917 and DUNKIRK: A conversation

1917 (2019).

DB here:

For over twenty years, the Willson Center for Humanities and Arts at the University of Georgia at Athens has hosted Cinema Roundtable, a series of film screenings and discussions. Covid-19 hasn’t stopped them from keeping it going, and they kindly invited Kristin and me to visit, virtually, and talk about two war films. The title is “Wartime Suspense in ‘Dunkirk’ and ‘1917’: A Conversation with Kristin Thompson and David Bordwell.”

We discussed aspects of style and genre. Many participants, notably Professor Tanine Allison of Emory, brought up other points about these two intriguing movies. It was also nice to see some old friends from Wisconsin logging in.

The entire session is on YouTube.

We enjoyed participating and thank our hosts, Dick Neupert and Dave Marr. In preparing for the session, I think it’s fair to say we liked both films better on rewatching them.

And no, we haven’t yet seen Tenet. Health precautions keep us at a distance. But we are keen, and when we can write about it, we will.

In a piece of good timing, Tom Shone’s book The Nolan Variations came out three days before our session. It’s excellent and offers the most comprehensive overview of this director’s achievements.

Our e-book on Christopher Nolan is available for download here. (Thanks to those Willson attenders who picked it up!) There’s some background on the book here. Our various blog entries on Nolan’s work are here.

Dunkirk (2017).

Little stabs at happiness 5: How to have fun with simple equipment

Tiger on Beat (1988).

DB here:

Simple equipment includes, but is not limited to, knives, pistols, shotguns, ropes tied to shotguns, surfboards, chainsaws, etc.

Herewith another attempt to brighten your days with a choice film sequence that never fails to bring a foolish grin to my face. Apologies as ever to Ken Jacobs for my swiping his title.

Tiger on Beat (aka, but less pungently, Tiger on the Beat, 1988) is prime Hong Kong showboating. This final scene assembles some of the greats—Chow Yun-Fat, Gordon Liu Chia-Hui, Chu Siu-Tung (too little to do)–and near-greats like Conan Lee Yuen-Ba, who gets points for heedlessly executing the stunts Chow and Chow’s doubles can’t. Lau Kar-Leung (aka Liu Chia-Liang), one of Hong Kong’s finest directors, imbues both the staging and the editing with the crisp, staccato rhythm that this tradition made its own, and that few American directors have ever figured out. (It’s a long clip, so it may take a little time to load. In addition, our Kaltura operation is having problems, so you may want to try different browsers.)

Come to think of it, this little-stabs entry contains some fairly big stabs of its own.

The whole film is worth a look. Opening scenes feature Chow in outrageous threads, the very opposite of a cop in plainclothes, and there’s a fine car chase in which many risk life and limb. But this sequence, lit high-key so that every splash of saturated color pops, is for me the highlight, a tour de force of action cinema. Probably not for the kids, but what do I know about kids?

Sequences like this were what drove me to teach Hong Kong film and write Planet Hong Kong. They also impelled Stefan Hammond and Mike Wilkins to write Sex and Zen and a Bullet in the Head (1996), the most deeply knowledgeable fanguide to this glorious cinema. Stefan followed it up with Hollywood East: Hong Kong Movies and the People Who Made Them (2000). Now Stefan and Mike have effected a merger of these and updated and expanded them. They’ve also recruited a band of other Guardians of the Shaolin Temple: Wade Major, Michael Bliss, Jeremy Hansen, Jude Poyer, David Chute, Dave Kehr, Andy Klein, Adam Knee, Jim Morton, and Karen Tarapata.

The result is another indispensable volume, More Sex, Better Zen, Faster Bullets: The Encyclopedia of Hong Kong Film. The recommendations are sound, the plot synopses are nearly as much fun as the movies, and the authors have wisely retained chapter titles like “So. You think your kung fu’s. . . pretty good. But still. You’re going to die today. Ah ha ha ha. Ah ha ha ha ha ha.”

They weigh in on today’s sequence: “This gory Armageddon-duet consistently scores on Top Ten End-Battle Lists among HK film aficionados.” Makes me even more confident to recommend it to you. They add that the credits music is “a hard-rocking theme song by HK power diva Maria Cordero.” So I let it run.

I analyze this and other action sequences in this blog entry. An appreciation of Lau Kar-Leung is here.

For more little stabs, check out earlier entries in this series.

Chow Yun-Fat gets his daily dose of egg yolks (Tiger on Beat).

Ozu’s silent talkie: PASSING FANCY on the Criterion Channel

DB here:

Our newest installment of Observations is now up on The Criterion Channel. In it I consider how Ozu’s Passing Fancy (1933) exhibits his distinctive methods for treating a scene’s space. Now, here’s a preview for a little bonus that will show up there next week. It’s a short on how Ozu sometimes relied on sound in a silent film.

You probably know about Japan’s katsuben, or benshi. He or she stood alongside the screen and accompanied the film–explaining the action, commenting on it, and imitating the characters’ voices while reciting the intertitles. The benshi were usually given scripts for the titles’ texts, but they were also expected to expand on them.

Benshi became celebrities, as strong an attraction as the movies, and they wielded power over some production companies. Benshi might reedit films to suit the performance they wanted to give. One reason that talking pictures came only gradually to Japan was the resistance of the benshi associations to being put out of work.

Filmmakers who resented the benshi’s power seemed to have sought to make the films as free-standing as possible. One strategy was to have many intertitles, which served to anchor the meaning of a scene. More positively, in Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema I argue that the presence of a benshi gave filmmakers new storytelling opportunities.

Knowing that the benshi would be speaking the lines in the intertitles, filmmakers could make those titles quite short, creating a swift rhythm. (Contrary to some impressions, Japanese silent movies aren’t slow; even dialogue scenes are likely to be cut fast.) Moreover, the benshi could make conversations more compact than what we find in American films. Instead of a pattern of speaker/title/speaker/listener, your shots could run: speaker/title/listener.

Just as important, filmmakers could count on the benshi to fill in things not shown onscreen. That could allow for some unusual interaction between images and speech.

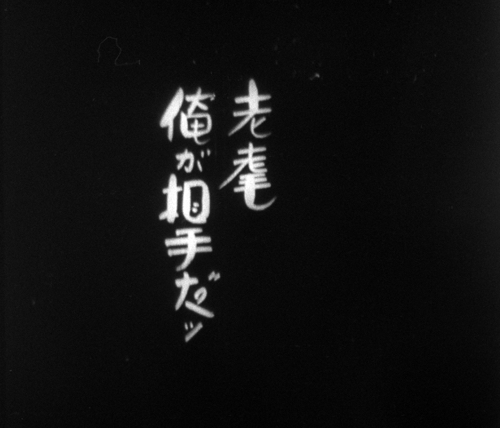

For example, Iwami Jutaro (1937), a swordplay comedy, treats one scene with “offscreen” sound. A bully is watching a kendo match. Cut to the rack of kendo swords, followed by a cry from one fighter, given in an intertitle: “Fool, you’ll be fighting me!”

Cut back to the rack collapsing, as if shaken by the fight. Another title: “I give up!” is followed by a shot of a fallen fighter, beaten.

The shot of the fallen bully anchors the title, but in the flurry of shots we’re invited to imagine the skirmish. Very likely the benshi was shouting the lines while the accompanying music whipped up a burst of excitement. This elliptical treatment of the match suggests that Kurosawa’s Sugata Sanshiro, made only a few years later, was heir to a tradition of off-center rendering of martial-arts combat.

Ozu recruits the benshi for something more ambitious, as I try to show in this bonus. Regrettably, we couldn’t find usable stills of benshi performances from the period, so the stills illustrate modern revivals. Also, I still haven’t seen Suo Masyuki‘s recent Talking the Pictures (Katusben!, 2019), a comedy about benshi culture.

Anyhow, a little analysis of what we have enables us to appreciate how Ozu uses the benshi to emphasize character reactions. The highlight comes in an emotional climax, when the benshi’s sobs would have filled in offscreen action.

Ozu, a fan of Western cinema, would have seen talkies and realized the power of offscreen sound. But I suspect he didn’t need external influences to understand that the benshi’s patter gave directors great freedom in visual narration.

Passing Fancy is one of three masterpieces Ozu released in 1933. (The other two, Dragnet Girl and Woman of Tokyo, are also on the Channel.) The Japanese cinema of this period was one of the glories of world filmmaking, with talent at all levels. Still, very few directors anywhere matched Ozu’s quietly outrageous innovations in form and style, his urge to show us cinema, and so the world, in a poignant, exhilarating way.

Thanks to Kim Hendricksen, Peter Becker, Grant Delin, Erik Gunneson, and the team at Criterion for enabling me to include this clip on our site. Thanks also to Komatsu Hiroshi for information on Iwami Jutaro and Steve Ridgely for correction of one of the intertitles.

For more on the benshi, see the comprehensive study Benshi, Japanese Silent Film Narration, and the Forgotten Narrative Art of Setsumei: A History of Japanese Silent Film Narration, by Jeffrey A. Dym (Edwin Mellon Press, 2003). Fascinating background on the struggles between the benshi and other sectors of Japanese film culture can be found in Joanne Bernardi, Writing in Light: The Silent Scenario and the Japanese Pure Film Movement (Wayne State University Press, 2001) and Aaron Gerow, Visions of Japanese Modernity: Articulations of Cinema, Nation, and Spectatorship, 1895-1925 (University of California Press, 2010).

Another intriguing review of Talking the Pictures is Jessica Klang’s in Variety.

Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema is available for free download here. (Be patient; the file is big.) An earlier Observations segment considered Kurosawa’s cutting of martial-arts action, and a blog entry developed that a bit more.

Another way to make a silent talkie is discussed in this entry on The Donovan Affair.

Passing Fancy (1933).

Sometimes a swordfight . . .

The Valiant Ones (Zhonglie tu, 1975).

DB here:

. . . makes you sit up. And notice a simple but ingenious cinematic technique.

One of the refrains of this blog is: We want to know filmmakers’ secrets, even the secrets they don’t know they know.

Over my years of studying Hong Kong film, I kept coming back to the work of King Hu (Hu Jingquan), one of the great directors of Chinese cinema. Most famous for A Touch of Zen (1971), Hu made several other striking martial arts films: Come Drink with Me (1966), Dragon Inn (aka Dragon Gate Inn, 1967), The Fate of Lee Khan (1973), and Raining in the Mountain (1979).

Kristin and I have a special fondness for The Valiant Ones (1975), which consists largely of virtuoso combat sequences. Here we find some of Hu’s most spectacular experiments in staging, framing, and cutting action scenes. The story isn’t complicated, but the result lives up to his motto: “If the plots are simple, the stylistic delivery will be even richer.” Unhappily, for reasons of rights, The Valiant Ones is harder to see than his other masterworks.

When I was studying Hu’s work at a European archive, I told the archivist that watching The Valiant Ones I had started to understand his secrets. She smiled and said, “All right, but don’t tell anyone.” Ha! Fat chance. I broke the news in an article and then in Planet Hong Kong. I use our current lockdown to share it more widely.

Suppose you have a character called the Whirlwind Swordsman. He circles his adversary so quickly, ducking and bobbing, shifting front and back, that the target is bewildered. How would you render this quicker-than-the eye tactic on film? Today’s directors think automatically of digital effects. But that wasn’t on the menu in 1975.

Wu Jiayun and his wife are pretending to be interested in joining a pirate gang. In a series of audition bouts, the chief pirate sends his minions to spar with them. Here we see first Wu’s wife take up a monk’s archery challenge. (I include that as bonus material.) It’s a fair sample of the rhythm Hu gets through a combination of editing and figure movement. The audition continues with Wu showing a stout pirate his Whirlwind technique.

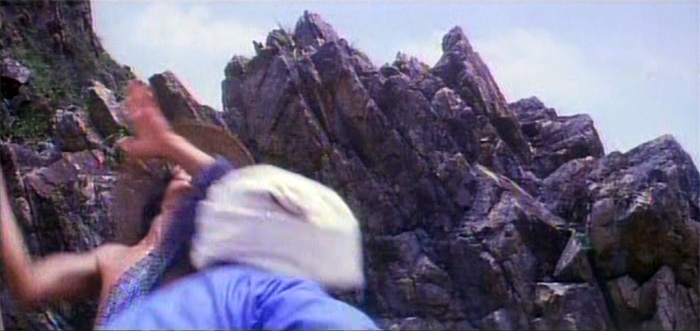

Did you see what King Hu did? He used a double for Wu, dressed him in white, and had him rocket into and out of the foreground while the primary Wu dodged in and out of frame in the background. Sometimes Wu leaves one spot and reappears elsewhere only one frame later!

Significantly, Hu set up this cleverly confined framing by means of a simple axial match-on-action. The larger view oriented us to the area clearly.

Giving up his fondness for discontinuous cuts, Hu used this cut to prime us to expect continuity of space as the shot unfolds. The double is in effect inserted in the splice.

Is it merely a trick? All’s fair in cinema. The gliding, percussive force of the frame entrances and exits shows us a preternaturally gifted fighter whose moves are too fast for the naked eye. We have no time to reflect on how it was done.

Interestingly, Wu seems to have taught Mrs. Wu his technique. At the climax she gets a chance to practice surrounding a hapless fighter. See my stills up top and at the bottom.

Secrets? You bet. We appreciate them all the more when we work to discover them.

For more on King Hu, see Stephen Teo, Chinese Martial Arts Cinema: The Wuxia Tradition (Edinburgh University Press, 2009). I discuss Hu’s style in more detail in “Richness through Imperfection: King Hu and the Glimpse” in Poetics of Cinema, and in “Three Martial Masters” in Planet Hong Kong, 2d. ed.

A Touch of Zen and Dragon Inn are available in fine restorations in the Criterion Collection and on the Criterion Channel. Also on the Channel is Hubert Niogret’s superb biographical film about King Hu.

Some recent entries (here and here) review the ideas of axial cutting and matches on action.

This is the second time I’ve used King Hu in this series; he’s a rich source of startling cinema. For other “Sometimes…” entries, go here.

The Valiant Ones (1975).