Archive for the 'Film technique: Editing' Category

His majesty the American, leaping for the moon

DB here:

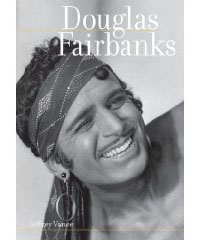

Douglas Fairbanks is remembered today as the nimble, insouciant hero of a string of swashbuckling films: The Mark of Zorro (1920), The Three Musketeers (1921), Robin Hood (1922), The Thief of Baghdad (1924), Don Q Son of Zorro (1925), and The Black Pirate (1926). He is the primary subject of a gorgeously illustrated, solidly researched new biography by Jeffrey Vance with Tony Maietta. Proceeding film by film, the authors interweave his life story with production data and summaries of critical reception. While tracing his career, they make an intriguing case that Fairbanks’ 1920s features more or less founded the modern film of action and adventure.

Douglas Fairbanks is remembered today as the nimble, insouciant hero of a string of swashbuckling films: The Mark of Zorro (1920), The Three Musketeers (1921), Robin Hood (1922), The Thief of Baghdad (1924), Don Q Son of Zorro (1925), and The Black Pirate (1926). He is the primary subject of a gorgeously illustrated, solidly researched new biography by Jeffrey Vance with Tony Maietta. Proceeding film by film, the authors interweave his life story with production data and summaries of critical reception. While tracing his career, they make an intriguing case that Fairbanks’ 1920s features more or less founded the modern film of action and adventure.

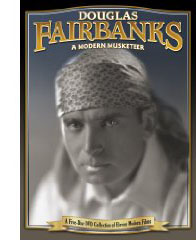

In the five years before The Mark of Zorro, Fairbanks made twenty-nine features and shorts. Vance and Maietta are enlightening on this period, but they treat it as prologue to the more spectacular work. Now, as if to counterbalance their book, comes a new Flicker Alley DVD collection, Douglas Fairbanks: A Modern Musketeer, gathering ten of the early films along with a very pretty copy of The Mark of Zorro and Fairbanks’ last modern-day movie, The Nut (1921), made because he wasn’t sure that Zorro would be a hit. (It was.) To the DVD package Vance and Maietta have contributed an informative booklet and they offer enlightening conversation in a commentary track for A Modern Musketeer (1917).

Kristin and I have long been fans of the pre-Zorro titles. Kristin wrote an appreciation of the early films for a Pordenone catalogue, and I studied Wild and Woolly (1917) as an early prototype of Hollywood narration. (1) There’s no denying that the 1920s costume pictures offer dashing spectacle and derring-do. But the 1915-1920 films are something special—lively, lilting, and unexpectedly peculiar. (2)

Kristin and I have long been fans of the pre-Zorro titles. Kristin wrote an appreciation of the early films for a Pordenone catalogue, and I studied Wild and Woolly (1917) as an early prototype of Hollywood narration. (1) There’s no denying that the 1920s costume pictures offer dashing spectacle and derring-do. But the 1915-1920 films are something special—lively, lilting, and unexpectedly peculiar. (2)

Before he became Fairbanks, he was Doug, the relentlessly cheerful American optimist. This star image was created very quickly, in films and in public events that made him seem the nicest guy in the country. His manic energy came to incarnate the new pace of American cinema, and his films helped shape the emerging precepts of Hollywood storytelling.

Doug

Consider his contemporaries. William S. Hart keeps his distance; perhaps his severe remoteness comes from secret pain. The result is a man you respect and admire but can hardly love. Mary Pickford, though, is lovable, and so is Chapin, although his cruel streak complicates things. But Doug is quintessentially likable. His early films present us with a brash youth who is all pep and pluck, bouncing with barely contained energy, unselfconscious in his engulfing enthusiasm for life. Today he could be elected President, the ultimate guy to have a beer with. (In real life Fairbanks was a teetotaler.)

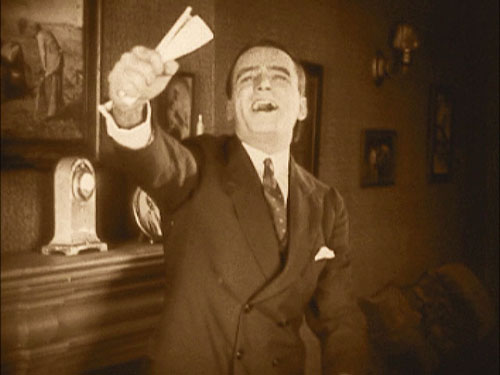

There is no guile in him, no hidden agenda. When he’s brimming with delight, as he often is, he flings his arms out wide. In another actor this would be hamminess, but for Doug it’s simply an effort to embrace the world. Any social embarrassments he commits—and they are plenty—he acknowledges with a puzzled frown before flicking on an incandescent grin. Who else makes movies with titles like The Habit of Happiness (1916) and He Comes Up Smiling (1918)?

There is no guile in him, no hidden agenda. When he’s brimming with delight, as he often is, he flings his arms out wide. In another actor this would be hamminess, but for Doug it’s simply an effort to embrace the world. Any social embarrassments he commits—and they are plenty—he acknowledges with a puzzled frown before flicking on an incandescent grin. Who else makes movies with titles like The Habit of Happiness (1916) and He Comes Up Smiling (1918)?

But how can such a genial fellow yield any drama? Give him an idée fixe, a cockeyed hobby or life philosophy into which he can pour his adrenaline. Now add a goal, something that his obsession blocks or unexpectedly helps him attain. Toss in the staples of romantic comedy: a good-humored maiden uncertain how to tame this creature of nature, a few old fogeys, some unscrupulous rivals. Hardened crooks may make an appearance as well. Be sure to include some tables, chairs, sofas, or horses for him to vault over, as well as some perches near the ceiling or on the roof; Doug feels most comfortable lounging high up. Add windows, for his inevitable defenestration. (In a poem about him, Jean Epstein wrote, “Windows are the only doors.”) There should also be chases. Other comedy stars run because they must. Doug’s joy in flat-out sprinting suggests that he welcomes the chance to flush a little hyperactivity out of his system. At the story’s climax he must save the day, taming his obsession and achieving his purpose while acceding to the claims of the practical world.

An early example is His Picture in the Papers (1916). In this satire on vegetarianism and the American lust for publicity, Doug works for his father’s health-food firm, even though he prefers thick steaks. But he’s full of ideas for promoting the product. Doug needs money to marry his equally carnivorous girlfriend, but his father will give him the dough only if Doug can pitch their line of dietary supplements. Doug vows to get his picture in every newspaper in town. While he launches a series of high-profile stunts—wrecking his car, entering a prizefight, brawling on an Atlantic City beach—his sweetheart’s father is pursued by a gang called the Weazels, who try to extort money from him.

The two plotlines converge, with Doug stopping a train wreck and winning a place on the front pages. (In a sly dig at the press, each news story contradicts the others.) The movie is a little disjointed, but several scenes are remarkable, not least a boxing match in an actual athletic club before an audience of cheering Fairbanks pals. And there is more than one funny framing, notably a nice planimetric one showing all our principals lined up and reading different newspapers celebrating Doug’s triumph.

As the title indicates, in The Matrimaniac (1916) Doug’s goal is elopement, which he pursues obsessively. He evades a rival suitor, his girlfriend’s father, a sheriff, and a posse of city officials in order to tie the knot in a gag that must have looked radically up-to-date. Reaching for the Moon gives us a more philosophical Doug, a naive disciple of self-help books that urge him to strive, to concentrate, and above all to keep his eye on the most supreme goal he can imagine. He ends up in New Jersey.

Wild and Woolly (1917) casts Doug as the son of a railroad tycoon. Although he lives in Manhattan, he dreams of being a cowboy. His bedroom boasts a teepee, and he practices his roping skills on the butler. Sent out to Bitter Creek to investigate a deal, he encounters the rugged frontier of his dreams, complete with shootouts, town dances, and hard-drinking cowpokes. But all of this is a show, staged by the locals to make him look favorably on a railroad spur. In another twist, a crooked Indian agent uses the charade to rob the bank and stir up an Indian settlement. Now Doug’s obsessions prove really useful, as his cowboy skills rescue the town.

Wild and Woolly is among the very best of the surviving early Fairbanks titles, and its adroit storytelling is still admirable today. The best-known version was a very poor print, salvaged from the Czech archives and still circulating on barely visible VHS and public-domain DVD copies. Forget those. On the Flicker Alley collection the image quality, while not perfect, allows this trim little masterpiece to be appreciated. (3)

“Always chivalrous, always misunderstood,” reads one intertitle in another gem, A Modern Musketeer. Here Doug is possessed by the spirit of D’Artagnan, simply because while he was in the womb his mother was reading The Three Musketeers. He manages to live up to his heritage as he overcomes a philandering rival and a bloodthirsty Indian. The climactic chase takes place at the Grand Canyon, affording Doug a chance to shinny up and down cliffs and do handstands along a precipice.

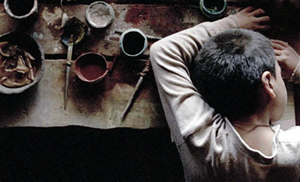

Doug never does things by halves. In Flirting with Fate, he is a starving artist, out of money and apparently unloved by his girl. The logical solution is to hire a killer to end his misery. Of course Doug’s fortunes instantly change, and life becomes worth living, but then he must somehow find his assassin and call off the hit.

Many of the early films show the protagonist fully formed as a cross between a cheerleader and a track star. But Fairbanks made a big success on stage playing a sissy. The task in such a plot is to turn him into a red-blooded man. His first film, The Lamb replayed this lamb-into-lion plot, which also served as the basis for Buster Keaton’s first feature, The Saphead (1920).

In the Flicker Alley collection, this strain of Doug’s work is represented by The Mollycoddle (1920). Doug is the descendant of hard-bitten westerners, but growing up in England has made him a fop. Coming to America with a batch of wealthy Yanks, he is a continual figure of fun, waving his monocle and cigarette holder. Once in Arizona, however, he’s confronted with a diamond-smuggling racket. He starts to channel his ancestors and turns into a hell-for-leather hero. He allies with a tribe of exploited Indians to capture the gang, in the process indulging in leaps, falls, canyon-scaling, and fistfights in raging rapids.

The titles often invoke craziness, vide the Matrimaniac, The Nut, and Manhattan Madness (1916). But this motif is carried to an extreme in one of the strangest pictures of the still-emerging Hollywood cinema. When the Clouds Roll By (1919) crams in enough gimmicks for three Doug stories. First, our hero is neurotically superstitious. He will climb over a building to avoid letting a black cat cross his path. He meets a girl who is as superstitious as he is, so after a session at the Ouija board, they seem a good match.

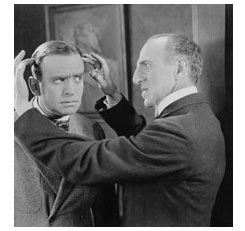

At the same time, however, a psychiatrist is making Doug the subject of a demonic experiment: Can one drive a person to madness and suicide? Through bribes and surveillance, Dr. Metz turns Doug’s life into hell—botching his romance, getting him disowned by his father, and even inducing nightmares. As if all this weren’t enough, the last reel jams in a train crash, a bursting dam, and a flood. Before this overwhelming climax, When the Clouds Roll By isn’t so much funny as eerily paranoiac. The way Dr. Metz’s Mabuse-like scheme enfolds everyone is as anxiety-provoking as anything in a film noir. This dreamlike movie ends on a surrealist note: Doug and his sweetheart get married when flood waters carry a church past them.

At the same time, however, a psychiatrist is making Doug the subject of a demonic experiment: Can one drive a person to madness and suicide? Through bribes and surveillance, Dr. Metz turns Doug’s life into hell—botching his romance, getting him disowned by his father, and even inducing nightmares. As if all this weren’t enough, the last reel jams in a train crash, a bursting dam, and a flood. Before this overwhelming climax, When the Clouds Roll By isn’t so much funny as eerily paranoiac. The way Dr. Metz’s Mabuse-like scheme enfolds everyone is as anxiety-provoking as anything in a film noir. This dreamlike movie ends on a surrealist note: Doug and his sweetheart get married when flood waters carry a church past them.

Across these films, in fact, the Fairbanks persona starts to disintegrate. Somewhat like those naïve Capra heroes of the 1930s (Mr. Deeds, Mr. Smith) who turn into melancholy victims in Meet John Doe and It’s a Wonderful Life, Doug becomes more brooding and helpless. In Reaching for the Moon, his absurd dream of glory is revealed as just that, a dream. When the Clouds Roll By saves itself from despair through splashy last-minute rescues.

Fairbanks was evidently becoming uncomfortable in cosmopolitan comedy. His taste for large-scale stunts and tests of prowess led him to the costume sagas of the 1920s. In the process, as Vance and Maietta point out, he cleared the way for Keaton and Harold Lloyd. Both comics would sometimes play obtuse idlers in the Lamb mode, and both would take thrill comedy to new heights. But avoiding Fairbanks’ ebullient optimism, Keaton brought a perplexity to every situation, along with an angular athleticism and a geometrical conception of plotting and shot composition. Lloyd frankly presented a hero lacking social intelligence, afflicted with a stammer or shyness or even cowardice, always desperate to fit in. Both men deepened the possibilities of modern-day comedy, thriving in the niche vacated by Fairbanks.

Bug and Mr. E

For nine of the early films, Fairbanks had the help of John Emerson and Anita Loos. All three worked on the stories, with Emerson usually directing and Loos writing the scripts and intertitles. The collaboration lasted only about two years, but it yielded some definitive moments in the creation of the Doug mystique.

Emerson found his first success acting and directing on the New York stage. Under Griffith’s supervision he started filmmaking in 1914, with an adaptation of his own successful play, The Conspiracy. I haven’t seen this or most of his other early work, but his 1915 Ibsen adaptation Ghosts, codirected with George Nichols, betrays little of the dynamism that would run through his Fairbanks projects (although The Social Secretary of 1916, without Doug, is lively enough). Emerson continued to direct films and New York stage productions until his death in 1936, at the age of fifty-eight.

Loos was a tiny prodigy. She sold her first scripts at age nineteen, with the third, The New York Hat (1913), directed by Griffith, earning her twenty-five dollars. (Her punctilious account book is reprinted in her 1974 autobiography Kiss Hollywood Goodbye.) After writing scores of shorts, she moved into features in 1916, when, she claims, Emerson discovered her script for His Picture in the Papers. Clearing the project with Griffith and casting Doug Fairbanks, the team proceeded. This, Fairbanks’ third feature, proved a great success and solidified important aspects of his star persona.

Loos married Emerson, whom she recalled as having “perfected that charisma, which even a bad actor has, of being able to charm his off-stage public.” (4) He called her Bug, she called him Mr. E., and they became a Hollywood couple. They kept themselves before the public eye with interviews and books like How to Write Photo Plays (1920) and Breaking into the Movies (1921). These are full of information about the filmmaking practices of the day.

Loos married Emerson, whom she recalled as having “perfected that charisma, which even a bad actor has, of being able to charm his off-stage public.” (4) He called her Bug, she called him Mr. E., and they became a Hollywood couple. They kept themselves before the public eye with interviews and books like How to Write Photo Plays (1920) and Breaking into the Movies (1921). These are full of information about the filmmaking practices of the day.

Why did Emerson and Loos split from Fairbanks? Loos says that that Doug had become somewhat jealous of her notoriety. (5) Further, the couple yearned to return to New York. There Loos would hobnob with the Algonquin club crowd and write Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, a successful serial, book, play, and silent film. Eventually she would write plays and return to Hollywood as an MGM screenwriter.

Although they remained married and collaborated on plays and films, the pair eventually lived apart, the better to ease Emerson’s philandering. “Mr. E.’s devotion was largely affected by the amount of money I earned,” Loos recalled. (6) By her own testimony, she earned plenty. She writes in 1921:

The highest paid workers in the movies today are the continuity writers, who put the stories into scenario form and write the “titles” or written inserts. The income of some of these writers runs into hundreds of thousands of dollars a year . . . . Scenario writing does not require great genius. (7)

Loos is largely credited with bringing the witty intertitle into its own. Expository “inserts” were often neutral descriptions of the action or pseudo-literary ruminations. Loos created intertitles that were amusing in themselves. When Jeff, the hero of Wild and Woolly, comes to Bitter Creek he’s delighted to find a rugged life matching the one he mimicked in his East Coast mansion. So naturally Loos’ title reads, “All the discomforts of home.”

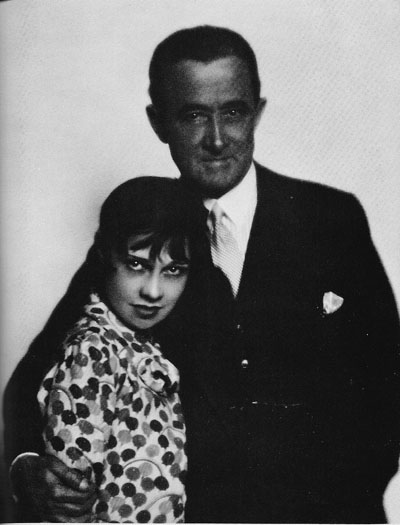

She wedged in puns, satiric jabs, and asides to the audience. The vegetarianism portrayed in His Picture in the Papers makes for anemic romance. Loos’ title prepares us:

The young suitor and Christine kiss by tapping each other’s cheek with their fingertips.

Later the intertitle stresses the more robust wooing program launched by Doug.

By the time Loos and Emerson left Fairbanks, the look and feel of their contributions had been mastered by others, notably director Allan Dwan, and smart-alec intertitles continued to grace Fairbanks’ modern comedies. Throughout the 1920s, most comedies would strive, not always successfully, for the cleverness Loos brought to the task. My own favorite in her vein comes in the Lloyd vehicle For Heaven’s Sake (1926). Harold is a millionaire courting a girl working in her father’s mission house in the slums, and one of the titles refers to “The man with a mansion and the miss with a mission.” Such niceties largely vanished when movies started to talk.

Cutting edge

We can learn a lot about the history of Hollywood from these films too. In the 1910s, narrative techniques were being put in place: the goal-oriented hero, the multiple lines of action, the need to prepare what will happen later, the use of motifs as running gags. At the start of The Matrimaniac, we see Doug sneaking into a garage and letting the air out of a car’s tires. Only later, after he has eloped with the daughter of the household, do we realize that this was a way to keep her father from pursuing them. In the course of the same film, the elopement is aided by passersby, and Doug keeps scribbling IOUs to pay them. At the end, the parson who has helped the couple the most is rewarded by the biggest payoff, with Doug shoveling bills at him.

The same years saw the consolidation of the “American style” of staging, shooting, and cutting scenes. (For more on this trend, see our earlier entries here and here.) Fairbanks’ films from 1916 to 1920 display a growing mastery of continuity techniques; the style coalesces under our eyes.

The system depended on breaking up master shots into many closer views. This practice was less common among European directors of the time, who might supply inserts of printed matter like letters but did not usually dissect the scene into shots of different scales. In His Picture in the Papers, for instance, we get a master shot (nearer than it would be in a European picture) of Melville paying court to Christine, followed immediately by closer views that show their expressions.

This is a minimal case. Not only are the shots all taken from the same side of the line of action (the famous 180-system) but they are taken from approximately the same angle. Filmmakers sometimes varied the angle more, usually to indicate a character’s point of view but sometimes to bring out different aspects of the action. (See here for examples from William S. Hart.)

Very quickly directors realized that you didn’t need a master shot if you planned your shots carefully. In Flirting with Fate, the artist Augy is chatting with Gladys, while her mother and her rich suitor watch from another part of the room. No long shot presents both pairs.

The mother summons Gladys, and when she and Augy rise, director Christy Cabanne cuts to another shot of them, moving into the frame.

This is a very rare option in most national cinemas of the period, which would simply frame the couple in a way that allowed them to rise into the top of the same shot. Now Gladys hurries out, crossing the frame line. This exit matches her entrance on frame left, meeting her mother.

Such a scene is obvious by today’s standards, but a revelation at the time—a way of lending even static dialogue scenes a throbbing rhythm that absorbed viewers. Around the world, notably in the Soviet Union, young directors saw this as the cutting-edge approach to visual storytelling. The new style was as probably as exciting to them as the powers of the Internet are in our time.

Because of analytical editing, the cutting pace of American films of the late 1910s is remarkable, and the Fairbanks films, with their strenuous tempo, are fair examples; the average shot length in these films ranges between 4 seconds and 6.6 seconds. With so many shots, production procedures emerged to keep track of them. To a certain extent shots were written into the scenarios Loos refers to, but directors also broke the action up spontaneously during filming. The cameraman, and later a “script girl,” would log the shots during shooting so that they could be assembled correctly in the editing phase.

Directors were still refining the system, though, as we can see from an awkward passage of shot/ reverse shot in A Modern Musketeer.

The eyelines are a bit out of whack, but odder still are the identical backgrounds of the two shots. Evidently director Allan Dwan made these shots quickly and closer to the canyon rim, in the expectation that nobody would notice the disparity.

Point-of-view shots were easier to manage, and they could intensify the drama. Later in A Modern Musketeer, the rapacious Chin-de-dah tells the white tourists he’s getting married. To whom? asks Elsie. Instead of answering, “You,” he holds up his knife.

Sometimes you suspect that filmmakers were multiplying shots just for the fun of it. The early Fairbanks films are vigorous to the point of choppiness; action scenes spray out a hail of images, some offering merely glimpses of what’s happening. Wild and Woolly is especially frantic, with the final sequences of kidnapping, gunplay, and a ride to the rescue breathless in their pace. In the course of it, Emerson realizes that fast action needs some overlapping cuts to assure clarity. Doug bursts through a locked door in one shot, and from another angle, we see the door start to open again.

Only a few frames are repeated, but the movement gains a percussive force. Doubtless the Russians studied cuts like this; Eisenstein made the overlapping cut part of his signature style.

By contrast, The Mark of Zorro and its successors have calmer pacing. Doug’s acting got more restrained too, with his bounciness largely confined to the action scenes. Already in 1920, high-end pictures were finding a more academic look, a polished and measured style. Dialogue titles became more numerous, and big sets and other production values were highlighted.

I’ve been able to sample only a few points of interest in the early Fairbanks output. I haven’t talked about Fairbanks’ foray into Sennett-style farce, the cocaine-fueled Mystery of the Leaping Fish (1916), or the bold experimentation of the cinematography in the dream sequence of When the Clouds Roll By. My point is just to note that these films radiate exuberance—not only in their hero but in their very texture. Scene by scene, shot by shot, Doug’s energy is caught by an efficient, pulsating style that was an engaging variant of what would soon become the lingua franca of cinematic storytelling.

For other reading on Fairbanks, you can consult Alastair Cooke’s Douglas Fairbanks: The Making of a Screen Character (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1940), one of the earliest and still most thought-provoking studies; John C. Tibbetts and James M. Welsh’s His Majesty the American: The Films of Douglas Fairbanks, Sr. (South Brunswick, NJ: A. S. Barnes, 1977), which is wide-ranging and strong on the early films; Booton Herndon’s Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks (New York: Norton, 1977); and Douglas Fairbanks: In His Own Words (Lincoln, NE: iUniverse, 2006), a collection of interviews and essays signed (but probably mostly not written) by the star. I’ve also been enlightened by Lea Jacobs’ essay “The Talmadge Sisters,” forthcoming in Star Decades: The 1920s, ed. Patrice Petro (Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, forthcoming). Online, there is much information at the Douglas Fairbanks Museum site.

(1) Kristin Thompson, “Fairbanks without the Mustache: A Case for the Early Films,” in Sulla via di Hollywood, ed. Paolo Cherchi Usai and Lorenzo Codelli (Pordenone: Biblioteca dell’Immagine, 1988), 156-193; David Bordwell, Narration in the Fiction Film (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1985), 166-168, 201-204.

(2) This set is very well chosen, but there are enough other films surviving from this period to warrant another box. It could include The Lamb (1915), Double Trouble (1915), The Good Bad Man (1916), Manhattan Madness (1916), The Americano (1916), Down to Earth (1917), The Man from Painted Post (1917), His Majesty the American (1919), and The Half Breed (1916), in which Fairbanks plays a biracial hero. On the matter of race, the films in the collection aren’t free of condescension and stereotyping, but there are also moments of affection between Fairbanks and Native Americans. He had extraordinarily dark skin, a fact he apparently took in his stride.

(3) I believe that this print is from a different version than the one I’ve known before; a few shots seem to show slightly different angles. (Perhaps the earlier one was from a foreign negative?) An informative page of the Flicker Alley booklet signals the provenance of the prints. While I’m on the subject, I should mention that occasionally the framing seems a bit cropped, but that could be due to the source material.

(4) Loos, Kiss Hollywood Goodbye (New York: Ballantine, 1974), 2.

(5) Loos’ account of the break with Fairbanks can be found in her memoir, A Girl Like I (New York, 1966), 178. You have to admire a book that ends with the line, “Miss Loos, you sure are flypaper for pimps!”

(6) Loos, Kiss Hollywood Goodbye, 14.

(7) Emerson and Loos, Breaking into the Movies (Philadelphia: Jacobs, 1921), 43.

When the Clouds Roll By.

PS 30 Nov: Internets problems and a memory lapse kept me from mentioning two other important books on Anita Loos: Gary Carey’s lively biography Anita Loos (Knopf, 1988) and Anita Loos Rediscovered: Film Treatments and Fiction, ed. and annotated by Cari Beauchamp and Mary Anita Loos (University of California Press, 2003). Both Carey and Beauchamp echo Loos’ claims that the couple split from Fairbanks because he was somewhat envious of the attention they received, while Carey adds that Fairbanks wanted to break out of the “boobish” parts Loos wrote for him (p. 50).

PPS 8 Dec: Mea culpa again. I overlooked Richard Schickel’s book-length essay, His Picture in the Papers: A Speculation on Celebrity in America, Based on the Life of Douglas Fairbanks, Sr. (New York: Charterhouse, 1973). It’s a lively and thoughtful argument that Doug was one of the very first modern celebrities, and one who enjoyed his role as such.

Categorical coherence: A closer look at character subjectivity

Subjective

[NOTE: There are some spoilers here, though I’ve tried to avoid giving away the ends of the films I mention. Teachers who show clips in class would probably want to do the same. Some of the films mentioned here would be good choices to show in their entirety to classes when they study Chapter 3 of Film Art.]

Kristin here—

We have had occasion to mention the Filmies list-serve of the Department of Communication Arts’ Film Studies area here at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Current and past students and faculty, sometimes known as the “Badger squad,” share news, links, and requests for information. Once in a while a topic is raised for discussion. These exchanges are usually fascinating, and when we have felt that they might be of interest to a general audience, we have used them as the basis for blog entries. (See here and here.)

Another occasion arose recently, one which relates to the teaching of Film Art: An Introduction. Matthew Bernstein, of Emory University, queried the group about suggestions for teaching a section of the third chapters, “Narrative as a Formal System.” He found that the section, “Depth of Story Information,” gives some students trouble. They can’t grasp the distinction we make between perceptual and mental subjectivity.

Our definitions of the terms go like this. Perceptual subjectivity is when we get “access to what characters see and hear.” Examples are point-of-view shots and soft noises suggesting that the source is distant from the character’s ear. In contrast, “We might hear an internal voice reporting the character’s thoughts, or we might see the character’s inner images, representing memory, fantasy, dreams, or hallucinations. This can be termed mental subjectivity.”

We then go on to give a few examples. The Big Sleep has little perceptual subjectivity, while The Birth of a Nation contains numerous POV shots. We see the heroine’s memories in Hiroshima mon amour and the hero’s fantasies in 8 ½. Filmmakers can use such devices in complex ways, as when in Sansho the Bailiff, the mother’s memory ends not by returning to her in the present, but to her son, apparently thinking of the same things at the same time.

Yeah, but what about …?

Filmmakers don’t always use these categories in straightforward ways. They may oscillate between perceptual and mental representations and events. Films may present narrative events that make the distinction between characters’ perceptions and their mental events ambiguous. That’s why in introducing the concepts, we stress that “Just as there is a spectrum between restricted and unrestricted narration, there is a continuum between objectivity and subjectivity.

Easy to say, but not necessarily so easy to grasp for a student who’s trying to understand these categories. They need to start with simple examples to familiarize themselves with the basic distinction before going on to what the likes of Resnais, Fellini, and Mizoguchi can throw at them. But some students immediately proffering exceptions. As Charlie Keil, of the University of Toronto, put it in his post on the subject, “I hardly need add that students, even the least analytically astute, border on the brilliant when it comes to suggesting examples that provide challenges to categorical coherence.”

Looking over the one and a half pages of the textbook that we devoted to depth of narration, you might find it fairly straightforward. Once you start looking for ways to teach the concepts without bogging down in too many nuances and subcategories, though, the passage does seem challenging. What follows is a suggestion about how someone might go about explaining and utilizing examples. It also points up some ways we might revise this passage of the book for its next edition.

What it’s not

One obstacle that Matthew has found is that students are used to thinking of “subjective” as meaning something like “biased,” as in “here’s my subjective opinion on that.” It might be useful to point out that this is only one meaning of the word. The dictionary definition that comes closest to the way we use it in Film Art is this: “relating to properties or specific conditions of the mind as distinguished from general or universal experience.” For film, we specify that “subjective” means either sharing the characters’ eyes and ears (properties) or getting right inside his or her mind (conditions).

Another misconception comes when students assume that the facial expressions, vocal tones, and gestures used by actors are subjective because they convey the characters’ feelings. Again, best to scotch that notion up front. Those techniques are projected outward from the character, and we observe them. Cinematic subjectivity goes inward.

One step at a time

Another distinction to stress early on is the basic one we make between film technique and function. There are a myriad of film techniques that could be used in either objective or subjective ways. To take a simple example, a low camera angle might indicate the POV of a character lying down and looking up at something; that’s perceptual subjectivity. A low angle of a skyscraper in an establishing shot might simply be the objective narration’s way of showing where a new scene will occur.

In contrast, indicating perceptual and mental subjectivity are two specific kinds of functions. Filmmakers can call upon whatever cinematic techniques they choose, and historically the more imaginative ones have shown immense creativity in trying to convey what characters see and think.

Some films depend heavily upon subjectivity, but objective narration is more common. There are many films that give us little access to characters’ perceptual and mental activities. Apart from The Big Sleep, there are films like Anatomy of a Murder, or virtually anything by Preminger. Most films use subjectivity sparingly. So let’s assume the students can tell that objective narration is the default.

With that out of the way, we can go back to basics. Both perceptual and mental subjectivity depend on being “with” the character in a strong way, as opposed to observing him or her as we would see another person in real life.

Perceptual subjectivity is fairly simple. The camera is in the character’s place, showing what he or she sees. The microphone acts as the character’s ears. Other characters present in the scene could step into the same vantage point and observe the same things.

So the test could run like this: As a viewer, when we see something in a film, is it really present within the scene? Could someone else in the same position see and hear the same things? Or is it a purely mental event, something no one else could see and hear, even if they stood beside the character or stepped into the place where that character had been standing?

If I were teaching the concept of narrational subjectivity as Film Art defines it, I would stress the notion of a continuum. After starting with very clear examples of both perceptual and mental subjectivity, I would progress to more ambiguous, mixed, or tricky instances.

Contributing to this discussion on the Filmies list, Chris Sieving, of the University of Georgia, says he shows a  clip from Lady in the Lake, the film noir where the camera always shows the POV of the detective protagonist. As Chris says, “It seems to effectively get across what perceptual subjectivity means (and how awkward it is in large doses), as well as what is meant by a (highly) restricted range of narration (as is the case with most whodunits).” As Chris also says, Lady in the Lake is a sort of limit case, a film that depends as much on perceptual subjectivity as it’s possible to do. (That’s “our” hand taking the paper in the shot at the right.) One could show several minutes from any section of the film and make the point thoroughly.

clip from Lady in the Lake, the film noir where the camera always shows the POV of the detective protagonist. As Chris says, “It seems to effectively get across what perceptual subjectivity means (and how awkward it is in large doses), as well as what is meant by a (highly) restricted range of narration (as is the case with most whodunits).” As Chris also says, Lady in the Lake is a sort of limit case, a film that depends as much on perceptual subjectivity as it’s possible to do. (That’s “our” hand taking the paper in the shot at the right.) One could show several minutes from any section of the film and make the point thoroughly.

There are other films that contain a lot of POV shots but intersperse them with objective ones. Rear Window is an obvious case. When Jefferies is alone, we see the courtyard events from his POV, a fact which is stressed by his use of binoculars and his long camera lenses to spy on his neighbors. This is clearly perceptual rather than mental. We never doubt that what we see through the hero’s eyes is real; we don’t believe that he’s making things up to entertain himself or because his mind is unbalanced. For one thing, there are two other characters who visit at intervals and see the same things that he does. We and they might question whether Jefferies’ interpretation of what he sees is correct, but we assume that the story’s real events have been conveyed to us through his eyes and ears. Only if we saw something like his fantasy of how he imagines his neighbor might have killed his wife would we move into the mental realm.

These two films foreground their use of POV. Usually, though POV shots are slipped into the flow of the action smoothly. Scenes of characters looking at small objects or reading letters often cut to a POV shot to help us get a look at an important plot element. At intervals during Back to the Future, Marty looks at a picture of himself and his siblings, gradually fading away to indicate that the three of them might never be born if he doesn’t succeed in bringing their parents together. It’s a simple way of reminding us what’s at stake and that Marty’s time to solve the problem is running out.

The Silence of the Lambs uses many POV shots and provides an excellent case of narration switching frequently and seamlessly between objective and subjective. Most of the POV views are seen through Clarice’s eyes, but sometimes through those of other characters. The first view of Lecter is a handheld tracking shot clearly established as what she sees as she walks along the corridor in front of the row of cells.

The scenes of Clarice conversing with Lecter develop from conventional over-the-shoulder shot/ reverse shot to POV shot/ reverse shot as both characters stare directly into the lens. (In Film Art, we use this device as an example of how style can shape the narrative progression of a scene [p. 307, 8th edition]). Other characters have POV shots as well, most noticeably, when Buffalo Bill twice dons night-vision goggles and we briefly see the world as he does.

Occasionally we see the POV of even minor characters, as when Lecter’s attack on his guard is rendered with a quick POV shot of Lecter lunging open-mouthed at the camera and then an objective shot of him grabbing the guard.

In their minds

Let’s jump to the other end of the continuum. Here we find a clear-cut use of mental subjectivity for fantasies, hallucinations, and the like. Obviously no one else present, unless he or she is posited as having special telepathic abilities, can see and hear what takes place only in a character’s mind.

Such fantasies are a running gag on The Simpsons, where Homer’s misinterpretations, distractions, and visions of grandeur are shown either in a thought balloon or superimposed on his skull. In the example above, he abruptly starts “watching” a little cartoon after assuring Lisa that she has his complete attention. No one could mistakenly assume that these exist anywhere but in Homer’s imagination.

In Buster Keaton’s Our Hospitality, the hero receives a letter telling him he has inherited a Southern home. After an image of him thinking there is a dissolve to a view of a large, pillared house. Later, when he arrives at his small, ramshackle house, he stands staring in a similar situation, and here there is a fade-out to his dream house, which abruptly blows up. The humor in the second scene would be impossible to grasp if we didn’t easily understand that the shot of the house exists only in his mind.

Whole films can be built around fantasies. A large central section of Preston Sturges’ black comedy Unfaithfully Yours consists of a husband envisioning three different ways he might kill his supposedly cheating wife, all set to the musical pieces he is conducting at a concert. Fellini’s 8 ½ is only the most obvious example of how the art cinema often brings in fantasies. Other examples include Jaco van Dormael’s Toto le héros or Bergman’s Persona.

Once students have grasped the basic distinction between perceptual and mental subjectivity, it might be useful to emphasize the continuum by moving directly to its center, where the two types coexist.

The middle of the continuum: Ambiguity and simultaneity

Right in the middle of the continuum between the pure cases we find ambiguous cases. Filmmakers can create deliberate, complex, and important effects by keeping it unclear whether what we see is a character’s perception of reality or his/her imaginings.

1961 was a big year for ambiguous subjectivity, with two of the purest cases appearing. One was a genre picture, the other a controversial art film.

The first is the British horror film, The Innocents, directed by Jack Clayton and based on Henry James’s novella, The Turn of the Screw. In several scenes, a new governess at a country estate sees frightening figures whom she takes to be ghosts haunting the two children entrusted to her. We see these figures as she does, but we never see them except when she does. The children behave very oddly in ways that might be consistent with her belief, yet they deny seeing any ghosts. Finally the governess tries to force the little girl to admit that she also sees the silent female figure standing in the reeds across the water. Does the child’s horrified expression reflect her realization that the governess knows about her secret relationship with the ghosts? Or is she simply baffled and frightened by the governess’s increasingly frantic demands that she confess to seeing something that in fact she can’t see?

From the first appearance of the eery figures, the question arises as to whether the governess is imagining the ghosts or they are real, controlling the children, who try to keep them secret. There are apparent clues for either answer. By the end, we arguably are no closer to knowing whether the ghosts are real or figments of the heroine’s imagination.

Since Last Year at Marienbad appeared, critics have spilled gallons of ink trying to fathom its symbolism and sort out the “real” story that it tells. Clearly there are contradictions in events, settings, and voiceover narration. The second of the three accompanying images depicts the heroine as the hero’s voiceover describes their first meeting. They talked about the statue that stands beside her, seen against the formal garden of walks lined with pyramid-shaped shrubs. Yet another version of the first meeting starts, this time with the characters and the same statue against a background of a large pool. Later scenes in these locales display the same inconsistencies.

Are such contradictions the result of one character’s fantasies or of the conflicting memories that two characters have of the same event? Or are the contradictions not the products of subjectivity at all but just the playfulness of an objective, impersonal narration, manipulating characters like game pieces to challenge the viewer? (Our analysis of Last Year at Marienbad is available here on David’s website. It and all the Sample Analyses that have been eliminated from Film Art to make room for new essays are available here as pdf’s; the index to them is here, about halfway down the page.)

It’s not a good example of subjectivity to show students, but just as an aside, the screwball comedy Harvey is an interesting case, a sort of reversal of the Innocents situation. The narration withholds a character’s perceptual and mental events. Elwood P. Dowd describes what he sees and hears: a six-foot talking rabbit invisible to us and to all the other characters. The story concerns whether Dowd’s relatives will institutionalize him for insanity, and we assume along with them Harvey is a mere delusion. Thus the narration seems to be objective—or, the ending asks, has it been very uncommunicative, withholding something that the hero really does see and hear? True, throughout the film the framing leaves room for Harvey, as if he were there. One could argue, though, that these framings simply emphasize that the giant rabbit isn’t visible to us or the other characters and hence isn’t likely to really exist.

A film can easily present both perceptual and mental subjectivity at the same time. A POV shot may be accompanied a character’s voice describing his or her thoughts and feelings. Matthew shows his class part of the opening section of The Diving Bell and the Butterfly, where a stroke victim’s extremely limited sight and hearing are rendered in juxtaposition with his voice telling of his reactions to his new situation. It is one of the most extensive and successful uses of such a combination in recent cinema, and it might be very effective in differentiating the two for introductory students.

A scene can also move rapidly back and forth between a character’s perceptions and his or her thoughts. Charlie writes that he shows his students the scenes of Marion Crane driving in Psycho. While the car is moving, almost every alternating shot is a POV framing of the rearview mirror or through the windshield. At that same time, we hear the voices of her lover, her boss, her fellow secretary, and the rich man whose money she has stolen while she imagines how they would react to her crime.

Showing scenes like these, where both types of subjectivity are used and clearly distinguishable might be more useful for students than showing several scenes that contain only one or the other.

Flashbacks, Voiceovers, and Altered States

In his original query to the Filmies, Matthew also said that students have problems with flashbacks: “Particularly, they resist the idea that a flashback is an example of subjective depth in general, even if the flashback unfolds objectively.” I can think of two ways to explain this.

First, classical films tend not to have flashbacks that just start on their own. To be sure, some do: a track-in to an important object and a dissolve can signal the start of a passage from the past, without a character being there. But more often a character is used to motivate the move into the past. A thoughtful look may do it, or a character may describe the past to someone else. In either case, the flashback is coming “from” the character and is assumed to show approximately what he or she is remembering. Occasionally the flashback may be a lie rather than objective truth, as we know from Hitchcock’s Stage Fright, The Usual Suspects, and a few other films.

In Poetics of Cinema’s third essay, David argues that most flashbacks in films are motivated as a character’s memory, but what is shown often strays from what he or she knew or could have known. He suggests that the prime purposes of most flashbacks is to rearrange the order of story events, and the character recalling or recounting simply provides an alibi for the time shift.

So we might think of character-motivated flashbacks as subjective frameworks that also contain objectively conveyed narrative information.

Second, the fact that flashbacks slip in objective information into characters’ memories is a convention. It’s a widely used method for presenting us with two things at once: first, a character’s memories and second, some story information that the viewer needs to have—even if the character couldn’t know about it. As we watch movies, we frequently accept conventions for the sake of being entertained. Beings that travel to Earth from distant galaxies speak English, high school kids can put together shows that wind up triumphing on Broadway, and people who drive up to buildings in crowded cities always find perfect parking spots. In a similar way, implausible mixtures of subjectivity and objectivity in flashbacks is just something we have to accept.

There are two other techniques that didn’t get mentioned during the discussion but that might confuse students.

What about shots showing the vision of a character who is drunk, dizzy, drugged, or otherwise unable to see straight? The most common convention is to include a POV shot that’s out of focus, perhaps accompanied by a bobbing handheld camera. Other characters in the scene, assuming they are not similarly impaired, would not see the surroundings in the same way.

Still, I think the same perceptual/mental distinction holds for such moments. The fuzziness and the lack of coordination are physical effects that are not being imagined by the character. They remain in the perceptual realm. Mental effects of impairment would be dreams or hallucinations. Some examples: the “Pink Elephants on Parade” sequence in Dumbo and the DTs vision of the protagonist of Wilder’s The Lost Weekend. As the title suggests, Altered States takes such mental activities as its subject matter and has many scenes that represent them.

A harder case is voiceover. Are all cases of voiceover subjective? Clearly not. If we have a situation where a character tells a story to a group and his or her voice continues over a flashback, the narration remains objective. We assume that the group can still hear the storyteller. Cases where the voice exists only in the mind, as when a character speaks to himself or herself, but not aloud, are mental subjectivity.

That said, there are many unclear cases. Just what is the status of the narration in Jerry Maguire? Jerry seems to speak directly to us, pointing out things that happen during the action, yet clearly there is no suggestion that he made the film we are watching. The problem is compounded in Sunset Boulevard, where the protagonist not only implicitly addresses us but is also dead. In many cases when a character’s voice is heard over a scene, it might occur to audience members to wonder where the character is or was when speaking these words. And does a character’s voice describing his or her feelings constitute objective or subjective narration? Probably we would want to say that only when the voice is posited as strictly an internal voice, audible only to the character, would we want to dub it subjective.

The problem with voiceovers arises, I think, because it’s such a slippery technique to begin with, and therefore often hard to categorize. Is a character speaking narration over events that happened in the past diegetic sound or nondiegetic? If there’s never an establishment of where and when that character does the narrating, he or she exists in a sort of limbo in between the two states: diegetic because he or she is a character, nondiegetic because he or she is in some ineffable way removed from the story world.

For voiceovers, then, I think it’s best simply to categorize the ones that obviously are straightforwardly objective or subjective. In tricky cases, we just have to admit that not all uses of film technique are easy to pin labels on. But the point of having categories like these isn’t to pin labels. In part knowing them allows us simply to notice things in films that might otherwise remain a part of an undifferentiated flow of images. They enable us to see underlying principles that make films into dynamic systems rather than collections of techniques. They give us ways to organize our thoughts about films and convey them to others. And, though students may doubt this, watching for such things becomes automatic and effortless once we have understood such categories and watched a lot of films. As a child, I don’t think I knew about the concept of editing or ever really noticed cuts. Now I’m aware of every cut in every film I see, and I notice continuity errors and graphic matches and other related techniques, all automatically, without that awareness impinging in the least on my following the story and being entertained. Learning the categories is only the beginning.

Playing with subjectivity

Once students have seen some clear cases of each type of cinematic subjectivity and understand the difference, the teacher could move on to emphasize that filmmakers can play with both in original ways. It’s not really possible in an introductory textbook to discuss all the possibilities—and probably not possible to come up with a typology that would cover every example of subjectivity that could exist across that continuum we mentioned. Imaginative filmmakers will always find new variants on how to use techniques for this purpose. But here are a few intriguing cases.

In his class, Chris shows the scene in Hannah and Her Sisters where the Woody Allen character, a hypochondriac, visits a doctor for some hearing tests. Initially the doctor comes into the room and gives a dire diagnosis of inoperable cancer. After Mickey has reacted to that, a cut takes us back to an identical shot of the doctor entering, but this time he gives Mickey a clean bill of health. The first part of the scene is retroactively revealed to have been a mental event, Mickey’s pessimistic fantasy.

The same sort of thing happens in a more extended way with the familiar “it was only a dream” revelations that make the audience realize that a major part of the plot has been subjective. In a more sophisticated way, as Chris points out, other sorts of mental subjectivity, usually lies or extended fantasies, can be revealed retrospectively, as in The Usual Suspects, Mulholland Drive, and Fight Club.

A flashback from one character’s viewpoint may reveal something new about an earlier scene. In Ford’s The Man who Shot Liberty Valance, the shootout is initially shown through objective narration. Only later in the plot does another character reveals that, unbeknownst to us or the other people present, he had also been present at the shootout. The flashback to his account reveals that the shootout happened very differently from the way we had assumed when first seeing it.

I’ll close with an example from The Silence of the Lambs. This shows how subtle and effective a play with perceptual and mental narration can be. In the scene at the funeral home where a recently discovered body of a murder victim is to be examined, Clarice is left waiting in the midst of a group of state troopers who stare at her. To get out of the situation, she turns and looks into the chapel, where a funeral is taking place. We see her face and then her POV as she surveys the room. A cut shows Clarice suddenly within the chapel, moving forward toward the camera and staring straight into the lens. We will only realize retrospectively that this image begins a fantasy that leads quickly into a memory. Clarice has not actually left her previous position just outside the door.

The next shot is a track forward through the center aisle toward the casket. Since Clarice had been walking in that direction before the cut, we recognize this as a POV and assume that Clarice is continuing to walk. Yet the man in the casket, as we soon will learn, is Clarice’s father. The shot represents a different funeral, one in the past which she has been triggered to remember by her glance into the chapel. The fantasy has become a flashback. A second, similar view of Clarice’s face returns us to her fantasizing adult self, the one remembering this scene but not the one still standing outside the door. A closer view of the father’s casket shows it from a lower vantage-point, as if that of a child.

The reason for the change becomes apparent from a radical change at the next cut, so that the camera is on the far side of the casket, filming from a low angle. The sudden shift moves us away from the adult Clarice in order to show her as a child approaching her father and leaning down to kiss him. A noise pulls Clarice out of her memory, and a cut back to the hallway shows her turning away from the chapel. (As often happens, sound, and particularly music, helps guide us through the scene, marking the beginning and ending of the fantasy/flashback.)

The most experienced film specialist could not track all the rapidly shifting levels of subjectivity in this scene on first viewing. Still, later analysis using some categories of subjective narration can help us appreciate how Demme has woven them into a scene that helps explain Clarice’s motives in becoming an FBI agent and her determination in pursuing her first case.

Categories matter

To some students, the categories I’ve just discussed may seem like trivial distinctions. They’re not. The use of subjective narration is one of the key ways the filmmaker has to engage our thoughts and emotions with the characters. In Psycho, we become involved in Marion Crane’s life in a remarkably short time, partly because of her situation but also partly because Hitchcock keeps us so close to her once she prepares to steal the money. The camera not only frames her closely, but to a considerable degree we see and imagine what she does: her fearful forebodings of how her rash act will turn out. Much the same thing happens with Clarice Starling in The Silence of the Lambs, though there our emotional involvement lasts throughout the film, and we are given glimpses of Clarice’s memories.

Perhaps choosing a scene or two from such films and going through them with the students, trying to imagine what it would be like without the POV shots and the imaginings and the memories, would convince them of the value of learning these categories. After all, the exceptions they find are only exceptional because they play in a zone defined by solid concepts.

[Note added October 24: I should have referred back as well to David’s entry “Three Nights of a Dreamer,” largely on POV.]

Objective

Dispatch from sunny Vancouver

Ballast.

After six days, plenty to report from the Vancouver International Film Festival. It has been unusually warm and sunny during our first week, but we have diligently spent most of our time in darkened theaters.

Kristin here:

Another country heard from

It’s a rare day when one gets to see a Haitian film. It’s an equally rare day when one gets to see a Jordanian film. On Monday I saw both, and the contrast between them could hardly have been greater.

Eat, for This Is My Body (Mange, ceci est mon corps, 2007), a Haitian/French co-production is Michelange Quay’s first feature. A Haitian-American, Quay received his MFA in directing at New York University.

The film’s opening is extraordinary, with a series of low-altitude helicopter shots beginning over the ocean and then moving rapidly across huge shanty-towns and finally into bleak mountain canyons in the country’s interior. After this passage of flight over bright landscapes, the bulk of the story takes place in and around a quiet, dark, nearly deserted colonial mansion somewhere in the countryside.

I’ve noticed that there seems to be a mini-revival of 1970s-style art cinema conventions. After many years in which art cinema tended to mean intricate psychological studies, a more challenging, formalist avant-garde seems to surface now and then. While watching Eat, for This Is My Body, it occurred to me that it could almost have been called Haiti Song, so strongly did it remind me of Marguerite Duras’s India Song. There enigmatic actions, often dancing, were staged in a colonial house. Eat, for This Is My Body’s action is, if anything, more enigmatic, though in this case the native population is present in the house in the person of a dignified manservant and a group of nine boys brought at intervals into the house, apparently as a treat.

The story is so minimal as to be non-existent. Apart from the nine boys, there are only three characters: an  old woman, a young woman, and the black servant. Not until about 70 minutes into a 105-minute film are these characters identified, though only to the extent that the younger woman is revealed to be the daughter of “Madame.” There are hints of an erotic attraction between the daughter and the servant, though this comes to nothing. The daughter’s wandering through the local town, among the teaming population engaged in washing, selling, and other everyday activities suggests that she may be gaining some insight into native Haitian culture—but this, too, remains a mere hint. Ultimately, the film creates not a narrative, but an evocative narrative situation full of mystery. The film was shot on 35mm and creates a lovely, austere style for the scenes shot within the mansion.

old woman, a young woman, and the black servant. Not until about 70 minutes into a 105-minute film are these characters identified, though only to the extent that the younger woman is revealed to be the daughter of “Madame.” There are hints of an erotic attraction between the daughter and the servant, though this comes to nothing. The daughter’s wandering through the local town, among the teaming population engaged in washing, selling, and other everyday activities suggests that she may be gaining some insight into native Haitian culture—but this, too, remains a mere hint. Ultimately, the film creates not a narrative, but an evocative narrative situation full of mystery. The film was shot on 35mm and creates a lovely, austere style for the scenes shot within the mansion.

The Jordanian film, Captain Abu Raed (2007), takes a more familiar approach, centering around a likable, heartwarming protagonist. Raed, an airport janitor, finds an old pilot’s hat, and the children in his working-class neighborhood assume he really is a pilot. He plays along, less to feed his own ego than to inspire their imaginations through false tales of his adventures abroad. Gradually he becomes more involved in the lives of some of his listeners, and the film progresses from the sugar-coated tone of the opening scenes into a darker situation as Raed seeks a way to save the family of a violent neighbor.

Director Amin Matalqa was raised principally in the U.S., but he returned to his native country for this, his first feature. It is also the first feature film to come from Jordan in decades, and it reflects a slow but distinct movement into movie production in some of the Middle-Eastern countries where conservative religious views have long suppressed it. Captain Abu Raed is technically polished and makes considerable use of Amman cityscapes and ancient ruins as backdrops for the action. It’s also definitely a crowd-pleaser, judging by the sold-out audience I saw it with.

Another rarity is Australian director Benjamin Gilmore’s first fiction feature, Son of a Lion (2007), which he filmed entirely in the Peshawar region of Pakistan. That’s an area adjacent to the northwest border of the country with Afghanistan, notorious as a refuge for Taliban fighters and probably Osama bin Laden. The program lists Son of a Lion as an Australian/Pakistan production. I doubt any Pakistani funding went into it, but Gilmour wrote the script with the advice of the local people, and non-professionals play all the characters. The credits also contain quite a few Pakistanis performing tasks behind the camera.

The story seems inspired in part by the “child’s quest” narratives of the Iranian classics of Abbas Kiarostami and Mohsen Makhmalbaf. A strict, traditionalist widower who makes guns wants his 11-year-old son to follow in the family business, while the boy longs to attend school. Apart from his father’s determined opposition, Niaz’s desires fly in the face of the local culture. Gun shops are everywhere, and every male adult seems to be armed. Shopkeeper casually step into the street to fire off weapons to test or demonstrate them. At one point the falling bullet from such random shooting kills a bystander. Between the personal scenes Gilmour intersperses occasional scenes of men sitting around and discussing the situation, debating whether they would shelter Bin-Laden if asked to or turn him in for the reward; they also speculate on America’s image of their part of the world.

and Mohsen Makhmalbaf. A strict, traditionalist widower who makes guns wants his 11-year-old son to follow in the family business, while the boy longs to attend school. Apart from his father’s determined opposition, Niaz’s desires fly in the face of the local culture. Gun shops are everywhere, and every male adult seems to be armed. Shopkeeper casually step into the street to fire off weapons to test or demonstrate them. At one point the falling bullet from such random shooting kills a bystander. Between the personal scenes Gilmour intersperses occasional scenes of men sitting around and discussing the situation, debating whether they would shelter Bin-Laden if asked to or turn him in for the reward; they also speculate on America’s image of their part of the world.

Son of a Lion was shot under difficult and dangerous circumstances on digital video (with post-production handled, amazingly enough, by Peter Jackson’s Park Road Post facility in New Zealand). The shots of the beautiful desert landscapes are not up to those we are used to from Iranian films, but they manage to suggest the grandeur of the area and to give a fascinating and humanizing insight into a region which the American government and media portray as merely a hotbed of terrorism.

Moroccan films are not quite as rare as these, but they’re certainly not common. As Burned Hearts (Morocco/France, 2007) was being introduced, I realized that the only other Moroccan film I had previously seen was by the same director, Ahmed El Maanouni. That had been Trances, a semi-documentary1982 film about a touring pop-music group. It was shown last year at the Il Cinema Ritrovato festival in Bologna, having been the first film restored by Martin Scorsese’s World Cinema Founda tion.

Burned Hearts was another film that seemed to transport me back to the 1970s art cinema. A young man returns to his childhood home after being educated as an architect in Paris. His tyrannical uncle is dying, and flashbacks present the painful memories evoked by the familiar sights and sounds of the city, this exploration of the character’s mental paralysis, along with the black-and-white cinematography of the locations, evokes both Duras and Antonioni. But El Maanouni refuses to concentrate solely on the hero’s concerns, bringing in several intriguing characters from the neighborhood and having groups spontaneously break into song and dance in the streets and shops.

Melodramas from Mexico

These films all come from regions seldom represented in international film festivals, but Mexican cinema  has had a growing presence in such venues in recent years. Two I’ve seen so far are very different from each other. The Desert Within (Desierto adentro, 2008), Rodrigo Plá’s second feature, already has a reputation after winning a cluster of prizes at the Guadalajara Film Festival. A period piece beginning in the late period of the Mexican revolution and extending into the 1930s, it tells the story of a peasant who inadvertently brings destruction on his village and decides that the only way to expiate his guilt is to drag his family far into the desert to build a church. The film takes a bitter view of Catholic guilt, with the protagonist forcing suffering, sexual frustration and death upon his children as his obsession grows.

has had a growing presence in such venues in recent years. Two I’ve seen so far are very different from each other. The Desert Within (Desierto adentro, 2008), Rodrigo Plá’s second feature, already has a reputation after winning a cluster of prizes at the Guadalajara Film Festival. A period piece beginning in the late period of the Mexican revolution and extending into the 1930s, it tells the story of a peasant who inadvertently brings destruction on his village and decides that the only way to expiate his guilt is to drag his family far into the desert to build a church. The film takes a bitter view of Catholic guilt, with the protagonist forcing suffering, sexual frustration and death upon his children as his obsession grows.

The other Mexican film, All Inclusive (2008), deals with another family crisis, but one which takes place over a few days in a luxurious resort on the “Mayan Riviera.” The story is slickly told by director Rodrigo Ortúzar Lynch and beautifully shot by Juan Carlos Bustamante, but I found the story forumulaic. A man who has just been told that he has only a short time to live, goes on vacation with his family, whom he has not informed of his condition. As he struggles with his secret, his wife and three children undergo their own crises. One daughter faces up to the fact that she is a lesbian, the son becomes entangled in an online “affair” with another man’s girlfriend, and the wife, assuming that her husband is being unfaithful, allows a young scuba instructor to seduce her—all this observed by the sardonic goth daughter.

As the tensions grow, a hurricane approaches, and the climactic set of revelations and reconciliations come just as it hits. During the narrative, each of the troubled family members manages to find someone gorgeous willing to bed them and/or hear their tales of woe. The idea that the bearish husband, seeking escape in a local bar, would run across a stunning 23-year-old Cuban woman who would take him into her home, listen at length to him, and finally, of course, teaching him to enjoy life. This gives him the courage to return to his family and tell them the truth. Once the family members have bared their soles, they become a jolly, well-adjusted bunch. It’s an entertaining story with likeable characters and touches of humor—but it’s a bit too much to believe.

Americans in Canada

Apart from Craig Baldwin’s Mock Up on Mu, which David will cover, I’ve seen two American indies so far. Momma’s Man (2008) is directed by Azazel Jacobs. It deals with Mikey, a man traveling on business who has problems with his flights and ends up staying with his parents in their New York loft. Finding excuses not to return to his wife and baby in California, he fritters away his time by reverting to his childhood pursuits. The film takes the daring step of being centered on an unsympathetic character who is the point-of-view figure for all but a few scenes. It manages to convey his gradual move from indecision to obsession and eventually a full-blown breakdown in a believable fashion.

Part of the appeal of Momma’s Man comes from the fact that Mikey’s parents are played by Ken Jacobs, the great experimental filmmaker, and his artist wife Flo Jacobs. It is set in their actual New York loft, a maze of odd filmmaking devices, accumulated pop-culture artifacts, and artworks. The two give extraordinary performances, managing to seem wise and caring and at the same time obsessive and eccentric to a degree that might have contributed to Mikey’s breakdown. Although Jacobs cast an actor as Mikey, one has to suspect that the film is at least somewhat autobiographical, and the casting of his parents has created a uniquely convincing portrait of a family.

David and I were delighted to see RR (2007) on the program. It’s the latest feature by American avant-gardist James Benning. Jim is an old friend, having been a graduate student in our department at the University of Wisconsin-Madison during our early years there. He has concentrated largely on landscape films, usually consisting of lengthy, static shots. This one consists wholly of distant views of trains in what appear mostly to be western and Midwestern locations. In virtually every case the shot holds until the entire train has moved through the shot or out of sight—or stopped, in a few cases.

As so often happens with structural films, small variations become evident to the alert viewer. A shot of a  car stopped for a train passing through a small town contains tiny reflections in the windows of a nearby house that may draw the eye. Some trains are covered with spray-painted graffiti, while others are pristine. One is led to speculate about what the cars may be carrying, and there is a hint of social comment in that activity. A considerable portion of most of the trains consists of tankers, presumably carrying the gasoline or other petroleum products that are currently causing so much trouble in our economy. Others contain numerous livestock cars, and one lengthy train contains nothing else. Among the views of many freight trains, we are treated to a glimpse of a single very short passenger train zipping through the briefest shot in the film.

car stopped for a train passing through a small town contains tiny reflections in the windows of a nearby house that may draw the eye. Some trains are covered with spray-painted graffiti, while others are pristine. One is led to speculate about what the cars may be carrying, and there is a hint of social comment in that activity. A considerable portion of most of the trains consists of tankers, presumably carrying the gasoline or other petroleum products that are currently causing so much trouble in our economy. Others contain numerous livestock cars, and one lengthy train contains nothing else. Among the views of many freight trains, we are treated to a glimpse of a single very short passenger train zipping through the briefest shot in the film.

RR draws us to enter into perceptual play, often with a distinct touch of humor. Few of Jim’s films have contained the measure of their shot length in their mise-en-scene so decisively. The length and speeds of the trains determine the duration of the shots, and one learns to watch for the number of engines pulling or pushing a train as an indicator of how long the train is likely to be. A few shots show trains moving slowly and decelerating at an almost imperceptible rate, teasing us as to whether they will stop altogether and whether the shot will end if they do. At times a train may move through the shot, only to reveal another on a parallel track. One shot plays a very clever game with us. I won’t reveal what it is, but the shot comes perhaps a third of the way through: an oblique view along a track with bushes prominently in the foreground and a short, arched underpass in the middle distance.

Jim has continued to shoot in 16mm in an increasingly digital age, and he consistently manages to make gorgeous images that look more like 35mm. The last one of RR, involving a vast wind farm, is a stunner.

Captain Abu Raed.

David here:

An unusually good VIFF, with many films to get your eyes open.

Enter the Dragons, with Tigers

As usual, the venerable Dragons and Tigers thread is offering some remarkable new films from Asia. The Good the Bad the Weird lived up to its reputation, not to mention its title, offering frenetic action and comic-book (in the good sense) bravura. Sell Out!, a Malaysian satire of corporate maneuvering and media brainwashing, doesn’t get points for subtlety—the goliath is called the FONY corporation—and sometimes it tries too hard. Still, it’s likeable enough, and the fact that it’s a musical adds a welcome bit of froth. The funniest bit, for me, was the opening parody of an art movie, which does actually get integrated into the main action.

Two late works by long-time Japanese directors offered a study in contrast. Kitano Takeshi’s Achilles and the Tortoise starts out sweet and ends very sour, not to say bitter. In telling the story of a boy whose spontaneous love of drawing is forced into narrow commercial channels, Kitano suggests that art is a racket. Across the decades, schools and galleries push the pliant, nearly comatose young artist to create a signature style. He is told to be original, but also he must harmonize with fashion and tradition. With a grim obstinacy he tries to fulfill what the business demands, and to the end he is still trying.

Achilles is less willful than Takeshis’ and Glory to the Filmmaker!, and it tells a more coherent tale, but their glum narcissism is still in evidence. The film cries out for an autobiographical interpretation: is the naïve filmmaker corrupted by exposure to international art cinema? Pictorially, there’s some confirmation of this: Kitano seems to have abandoned his early films’ ingenious use offscreen spaces and planimetric compositions. Like his hero, who can’t achieve artistic singularity, Kitano has become a surprisingly academic and anonymous stylist.

One can’t claim high originality for the style of Wakamatsu Koji either, but at least United Red Army has a gripping premise. The 1960s student movement was driven by opposition to the war in Vietnam and Japan’s cooperation with US policy, but in the following decade some factions emerged that were committed to violent revolution. Small cadres sequestered themselves in mountain cabins. Their exercises in “criticism and self-criticism” devolved into games of increasingly murderous aggression.

One can’t claim high originality for the style of Wakamatsu Koji either, but at least United Red Army has a gripping premise. The 1960s student movement was driven by opposition to the war in Vietnam and Japan’s cooperation with US policy, but in the following decade some factions emerged that were committed to violent revolution. Small cadres sequestered themselves in mountain cabins. Their exercises in “criticism and self-criticism” devolved into games of increasingly murderous aggression.

Wakamatsu’s technique is unstressed: No fancy angles, neverending tracking shots, or virtuoso compositions, just a businesslike application of today’s wobbly handheld look. The cunning lies in the film’s structure. After a half-hour montage summarizing the formation of the group, we are carried into the hideouts and watch the punishment grow more feverish and self-destructive under the domination of two leaders who seem parallel to Mao and Madam Mao.