Archive for the 'Film technique: Editing' Category

Reflections in a crystal eye

Whew! After many months of work, we finally sent in our revised third edition of Film History: An Introduction. Elsewhere on this site you can read about its earlier incarnations, and we expect to say more about it as it approaches publication in February 2009. But writing this tome isn’t as fast as webposting, for sure.

So how did we celebrate? A meal out and Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull (after about sixteen trailers for Paramount and DreamWorks releases). As with Beowulf and Ratatouille, we talk/ write about it together, but not in dialogue form. Kristin gets her time at the podium, then David. And there are of course spoilers.

Don’t even mention pyramid power

Kristin here:

I enjoyed the first half or so of IJatKotCS, but gradually it occurred to me that it wasn’t really building. It was violating the basic law of suspense films, which is to make your villain threatening and the things at stake important. Sure, in the B-film serials that inspired the Indiana Jones films, the premises are ludicrous. But so are the sets and the acting and just about everything about them, because they were so cheaply and quickly made.

With Indiana Jones, these adventure films become high-budget productions with the biggest, best special effects that money can buy. They star actors who have won or been nominated for Oscars. Moreover, the scripts don’t imitate the clichéd, bare-bones plots of the Bs. These are complicated stories that not only move ahead at a pace undreamed of in the serial days, but they toss in many little details and in-jokes in the backgrounds. With Steven Spielberg directing, one expects the non-stop thrills to also make sense, at least in a casual way.

Eventually I became distracted by the fact that certain things stopped making sense to me. Most obviously, what is at stake with that crystal skull? The Soviets want it, and Irina Spalko informs Indy that it’s to make a psychic weapon. Hmmm. And what is that, exactly? She doesn’t explain, and it’s clear that the Reds don’t know enough about the crystal skull to really understand what they’d do with it. In fact, they need Indy to help them every step of the way, and after a certain point his expertise becomes irrelevant, and they’re all dependent on Prof. Oxley to lead them to the kingdom.

I suspect most people’s reaction to her “psychic weapon” announcement is to think she’s nuts, deluded. The skull has apparently driven Oxley crazy (John Hurt playing loony as only he can do). Or did that just happen because he was locked in a very grim Peruvian insane asylum? We’re allowed to go on wondering if the skull has any psychic powers until the scene where Indy gets strapped in a chair and forced to stare into the eyes of the skull. The fact that he is so profoundly shaken by the experience finally shows that the object does have some sort of psychic effect.

But how could it be a weapon? Earlier an atomic bomb has gone off, and that’s engineered by our side, the good guys. How could a psychic weapon top that? Are the Russkies going to strap all the American soldiers one by one into chairs and make them stare into the skull? Talk about creeping Communism!

Spalko can’t explain it to us, since she is trying not only to get the skull but to figure out its secrets. Up to the very end, she says “I vunt to know.”

Of course, ignorance on the part of the villains need not be a problem. In Raiders of the Lost Ark, the Nazis didn’t know what power the Ark of the Covenant contained until it was too late. At least there, though, we understand from early on that the Ark really is dangerous in what is presumed to be a physical way. Moreover, there the villains were Nazis. We know what horrors the Nazis perpetrated on the world, and we and our allies actually went to war with them. With the Soviets, it was largely a long, tense brinksmanship. Luckily we never found out what a war with the USSR would be like. Today, well after the Soviet Union imploded on its own, the paranoia over reds in our midst seems quaint in an adventure film. Early on Indy and his department chair (Jim Broadbent) lose their jobs, and in a glum scene they deplore how Americans’ irrational fear of Communism has caused it. Yet soon after we discover that there really are Communist spies looking to steal America’s secrets. A mixture of tone, to say the least.

In Raiders, the Nazis seemed to be part of a worldwide network of spies. Spalko seems to be operating with only the group of soldiers that accompanies her. She never reports back to “headquarters.” One wonders if maybe Khrushchev sent her off on a wild-goose chase to get rid of her for a while.

Professor Jones Flunks Archaeology 101

One thing that distracted me and that seems to vitiate the notion of real threat in IJatKotCS is the fact that it’s based on hoaxes and wacko theories. At least there’s some archaeological evidence that elements of the Bible have their bases in real events. There may have been some sort of Ark of the Covenant and a Holy Grail. But to base the premise of the film on Chariots of the Gods (Erich von Däniken, 1968) and crystal skulls gives it a certain ludicrous quality that wasn’t there in the earlier films’ premises, wild though they were.

The film flits lightly past the nuts and bolts of how that Kingdom of the Crystal Skull came to be. Presumably, as in Chariots of the Gods, the aliens arrived and traveled around giving instructions on how to build such things as pyramids and Easter Island statues. The room in IJatKotCS where artifacts from Egypt, China, and other ancient cultures are gathered implies that long ago the aliens visited the earth, collected examples of the fruits of their teachings, and … instead of putting them in their space ship to take home, they left them in a chamber that would be crushed when the Kingdom built over the space ship is destroyed. (Don’t get me started on where the ancient Peruvian warriors who pop out of the walls to briefly chase the good guys came from.)

Then there are the skulls. The “real” crystal skulls held in museums, most notably the British Museum one referred to in the film, have been shown to be objects made in modern times, probably within the past 150 years. Those skulls, however, are of normal proportions. The ones in the movie are strangely elongated. Head-binding, Indy offhandedly explains.

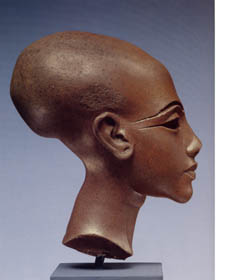

There’s another apparent source for this, one that I’m familiar with. The pharaoh Akhenaten, famed equally for inventing monotheism back in the 14th Century BCE and for being married to Nefertiti, has been the subject of much far-out speculation. The art of his era, the Amarna Period, shows his family with strikingly elongated skulls, as in the quartzite head of the statue of a princess at the left. Head-binding, various medical syndromes, and pictorial stylization have been posited. One imaginative claim has it that Akhenaten and his family actually were space aliens.

There’s another apparent source for this, one that I’m familiar with. The pharaoh Akhenaten, famed equally for inventing monotheism back in the 14th Century BCE and for being married to Nefertiti, has been the subject of much far-out speculation. The art of his era, the Amarna Period, shows his family with strikingly elongated skulls, as in the quartzite head of the statue of a princess at the left. Head-binding, various medical syndromes, and pictorial stylization have been posited. One imaginative claim has it that Akhenaten and his family actually were space aliens.

In fact, we still have no convincing explanation as to why this style occurred in Amarna statuary. (The Egyptian expedition I work on is at Amarna, the ancient city built by Akhenaten, and I work with statuary fragments found there.) The film, of course, doesn’t bring Akhenaten into it, though I think I did spot a photo of the seated statue of him in the Louvre on the chalkboard of Indy’s classroom. Akhenaten is a figure of considerable interest to New Age enthusiasts. Every now and then a group of people in white robes and turbans actually come to Amarna to worship in the ruins of the temples.

The ancient-aliens-visited-earth premises and the less explicit references to Amarna are woven in with El Dorado and with the Roswell myth that modern aliens visited earth. There’s even a nod to the Alien Autopsy film that David discussed in an entry on “Film Forgery.” The film also brings in the mysterious Nazca Lines, the shapes carved into the earth over which Indy and Mutt fly as they arrive in Peru. Some have claimed that the lines are runways for alien ships, and I think the film tries to imply that. But why would a flying saucer that takes off (and presumably lands) vertically need a runway, let alone one shaped like a monkey or any of the other complex figures that survive today?

The silliness that hovered near the edge of plausibility in the earlier films has crossed that line. At least the first and third movies made an effort to ground their mcguffins in real history and real places. Tanis, where a lengthy portion of Raiders takes place, is a real set of ruins in Egypt. In Last Crusade, Indy and his father can spar by showing off their knowledge of actual or apparently actual history. (I’ll leave it to the comments on the “goofs” page of the Internet Movie Data-base to deal with the transfer of the Mayans from Central America to Peru.) Each of those films was a race to prevent a lethal object falling into the hands of those who would both desecrate it and use it for evil purposes. Crystal Skull is a race to figure out what the apparently dangerous object is, given that the only person who knows, Oxley, is conveniently rendered unable to explain it.

Indy and his group win the race and get to the chamber ringed by crystal skeletons first, so that Spalko is effectively defeated before she gets there, though she doesn’t know that yet. Which brings me to the last thing that baffled me. Why, if the thirteen skeletons were separate beings, as they are depicted in the wall paintings, do they merge into one before being restored to life? Apparently the space ship was waiting to depart because, unlike in E.T., the aliens didn’t want to leave one of their number behind. But is there more than one alien left at the end to depart in the huge ship? Does the ship wait simply because it brought only one passenger, and that passenger can’t start it moving until it gets its head back? Yet surely there would have had to have been a crew to help build all those ancient wonders and bring the evidence back to the “kingdom.”

Maybe a second viewing would clear all this up, but the old serials didn’t need second viewings to be understood—and neither did the earlier Indy films.

The Spielberg Touch

DB here:

Kristin’s critique reminds us that the classic Hollywood structure demands a linear logic, but not a plausible or even particularly deterministic one. Like other action films, Crystal Skull follows the template she pointed out in her New Hollywood book: four parts, the first three running about half an hour and the climax somewhat shorter, the whole capped by an epilogue. It goes to show the difference between plot structure and the events of the fictional world that structure presents. The structure can make preposterous or puzzling chains of action seem acceptable—especially if it whisks them along.

I was taken, as usual, by Spielberg’s brisk direction. In the last decade he’s had a remarkably hot hand. Amistad, Saving Private Ryan, A. I., Minority Report, Catch Me If You Can, The Terminal (much underrated, I think), The War of the Worlds, and Munich are very strong movies. For all their faults (sometimes those slippery endings), they would be enough to establish a younger director at the very top. So I was watching for what I take to be The Spielberg Touch.

His staging is still solid and resourceful. When he has to let people talk, he moves them around the set, avoiding those dreary passages of stand-and-deliver that most directors today resort to. (Check the dialogue scenes from The Matrix Reloaded.) In a soda fountain, he lets your attention drift from the exposition between Mutt and Indiana to the teenyboppers behind them, to the point where I was distracted from Mutt’s explanation of those muddled plot premises Kristin points out.

Spielberg has said that he favors lengthier shots than are typical today. That’s true in most of his dramas and comedies, but here the cutting is fast. The shots average 4.6 seconds by my count, which is about the same as the other Indiana Jones films (1). But whatever his shot length, Spielberg doesn’t resort to choppiness, the sort of image-snatching that typifies today’s mainstream cinema. He’s one of the few filmmakers working today (Shyamalan is another) who tries to give most shots a distinct arc—a beginning, a middle, and an end.

Granted, most shots in any movie will develop or progress, even if a character just steps forward or raises an eyebrow at the end of a spoken line. But Spielberg enriches his shots in the way that the old adage suggests: The only problem of direction is to prepare the audience for what is going to happen next.

The ambitious Spielberg shot starts with something that links precisely to a previous shot, then develops a visual or narrative premise of that, then ends with a firm point of information that carries us into the next shot. His main tools for building the shot are are spatial depth and camera movement.

Linking the shots, in multiple ways

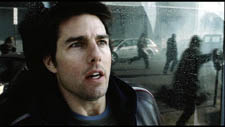

In War of the Worlds. the protagonist Ray is hurrying toward the center of his neighborhood, where people are gathering. He passes a garage, where the mechanic Manny and his assistant are trying to fix a burned-out ignition. As Ray strides by, he suggests changing the solenoid, and Manny agrees. This becomes important later, when Ray will seize the vehicle because it’s the only civilian car that’s working.

Spielberg binds his shots together in this way. The end of the first shot shows Ray, along with others, hurrying to the left. Cut to a shot from inside the garage, with a silhouette in the foreground bending over a car’s engine. Ray becomes visible in the distance.

Ray’s appearance and reappearance link the shots, while Spielberg’s composition has prepared us for a dialogue between Ray and the man, as yet unseen, in the foreground. Cut to a moving point-of-view shot of Manny rising and turning to Ray (us) and explaining what has happened.

Reverse shot of Ray, still trotting along, over Manny’s shoulder as he suggests changing the solenoid. As he goes on, cut: The moving shot now detaches itself from Ray’s point of view and shows Manny ordering his assistant to change the solenoid. The assistant bends over the engine.

Cut to another driver bent over his engine. This reiterates the story point that everybody’s car has stopped, but it also echoes the end of the last shot (and the beginning shot of Manny in silhouette). Crane up slightly to pick up Ray walking leftward in the distance, an echo of the foreground/ background interplay of the Manny/ Ray shot.

How to develop this shot? We follow Ray, along with a skateboarder, to the intersection, where Spielberg introduces a new element. The shot gradually brightens and as Ray moves to the major intersection, rays of light wash out the image.

The next shot will repeat this pattern, from darkness to rays of light, so that the following shot can start with a burst of light that envelops Ray.

Then a new story component, involving Ray’s two buddies, comes in from the foreground. Their conversation with Ray will get a tracking shot devoted to it, but it will end with a story point….and so on.

Spielberg maps his story points quite precisely onto the beginning/ middle/ end of his shots so that they link smoothly with one another. Each camera movement or depth pattern leads to a distinct revelation, sometimes a fresh one, sometimes an expansion or specification of information we’ve already received. This is one reason he uses so many matches on action, even in simple dialogue scenes. The last bit of one shot can serve as the premise for the next if its movement can be carried over the cut.

Something extra between the shots

Sometimes that last bit is a surprise. Something pops up in the foreground or on the frame edge, or the camera slides over or back to reveal something that impels us toward the next shot. In Crystal Skull, Indy swiftly empties a refrigerator, hurls himself in, and as he yanks the door closed it swings toward us revealing the label LEAD LINED before it shuts . . . and the atom bomb goes off.

Sometimes the end-of-shot payoff sets up a motif that itself will be paid off later. When Ray runs from the spindly, towering alien vehicle, he ducks around a corner and halts, but Spielberg’s framing gives us time to see the fleeing crowd reflected in a shop window. Spielberg introduces a new motif when Ray, stepping out from behind a car, is standing near a man taking a photograph.

Shortly, another reflection, this time supplying both action and reaction: the alien walker seen in in a shop window as people inside stare at it. And again we have photography, when, in a shot echoing the earlier one, a man upstages Ray and films the creature’s advance with a video camera.

At the climax of this string of shots, the creature’s approach is again given in reflection, only now it’s Ray standing alongside it (bringing together two elements previously kept apart, Ray and the reflection of the aliens). After the creature sends out its death vibes, the video camera falls into the shot, showing us, in its own version of reflection, the fleeing crowd–the subject of the first reflected image we saw.

Following the end-of-shot hooking principle, the image on the video screen will link to the next shot we see of the people fleeing in panic. My larger point is that the braiding of motifs—reflections, photography—ends with them knotting together in a single image, the shot of the video camera. This sort of patterning was something that Eisenstein both theorized and practiced; he called it “wickerwork” montage construction. Spielberg has, in the context of American action pictures, rediscovered how powerful it can be.

He brings the same shot-by-shot fluency to dialogue scenes. A small scene in The Terminal shows Victor tussling with an official over his passport. Spielberg sets it up with our old friend, over-the-shoulder shot/ reverse shot, but he gives us two bits of business: The official slipping Victor’s plane ticket into a pouch, and Victor grabbing back his passport.

Match on action as the official continues to put away the ticket and demands the passport. A change of angle to a profile view adds a little amusement to the scene.

In reverse-angle Victor warily extends the passport. Cut back and forth as the two men tug on it, the action accentuated by a squeezing sound.

The official wins, and he slips the passport into the pouch. Spielberg gives us a variant on the reverse-angle on Victor, adding a fast rack-focus that resolves the scene with a neat snap.

In making even small gestures engage us in a visual flow that is rhythmically arresting, Spielberg displays craftsmanship of a high order. Despite his influence on a generation of filmmakers, this level of skill is rare today. If this be Storyboard Cinema, make the most of it.

I’ve already gone on too long, but I want to suggest that this cunning arc of interest, of doling out story points within shots and across cuts, also quickens his chase scenes. We say that his action scenes are clear, and partly that comes from his patient willingness to design long shots and overall views that keep us oriented. But these sequences also draw us in because shot by shot they build carefully, with little transitions—a glance, a gesture, a shift of focus or framing—that crisply link to what we will see next.

I saw a little of this crispness and fluidity in the pursuits of Crystal Skull. They can’t help but seem fairly stale, since Spielberg is competing with himself and with directors who learned from him (e.g., John McTiernan in Die Hard). And as per convention, bad guys have bad aim and they run out of bullets at an awkward moment. Yet the chases still piled complication upon silly complication, from ants and rapiers to cliffs and waterfalls, often set up at the end of one shot and paid off at the beginning of the next, which also sets up another.

The Spielberg Touch includes some visual wit. Everyone remembers the shot from Jurassic Park showing the T-Rex pursuing the Land Rover, as reflected in a side mirror saying “Objects in mirror are closer than they appear.” I think the habit goes back to Jaws, possibly still Spielberg’s best movie: the billboard with the graffiti and of course the rise of Bruce from the sea as Brody is scooping chum over the side. To make audiences gasp and laugh at the same time is no mean feat.

Crystal Skull seems to display less of this wit. The glimpse of the Ark of the Covenant in the warehouse and especially the montage of a squeaky-clean suburbia about to be vaporized were typical Spielberg, but I wanted more. Maybe a second viewing will show me that more.

But I was glad to see the Roswell ingredient here, and to learn that Indy did his duty in July 1947, even if he wasn’t there for the alien autopsy.

Faces and light

Finally, a little image-cluster that recurs in Spielberg’s work intrigues me. It was in Close Encounters that I first noticed his fascination with linking faces and beams of light. In that movie people just watch, transfixed by the luminous aerobatics of the vagrant UFOs and then eventually by the four-alarm light show pumped out by the mother ship. Then there’s the iconic image of Elliott staring at E. T.’s luminous digit, and the radiance of the church in the above scene from War of the Worlds.

Light beams can be punishing too. They melt faces in the first Raiders and blow a woman’s face to bits in War of the Worlds. They’re back again here—sprayed out by an alien intelligence and infecting the bad guys. Poor Irina Spalko, played with pelvic-thrust relish by Cate Blanchett, absorbs the rays through her eyes before detonating in one of those Armageddons that are obligatory in today’s megapicture. (Why do blockbusters have to include literal blockbusters?)

Maybe a critic in the vast Spielberg literature has discussed this dynamic between uplifting light and damning light, the enthralled face and the blasted one, characters spellbound by light and doomed by it. My hunch is that it will take us into religious and/or New Age territory.

(1) I get 4.3 seconds for Raiders, 3.5 for Temple of Doom, and 4.7 for Last Crusade.

Minority Report.

Some cuts I have known and loved

DB here, belatedly:

We’ve been so busy revising our textbook, Film History: An Introduction, for its third edition that we’ve had no time to see new movies, let alone blog on our regular schedule. To those loyal readers who have been checking back occasionally, we say: Thanks for your patience. An entry that should intrigue you is in the works, possibly to be posted very soon.

In the meantime, here’s an item on a subject I’ve been meaning to slip in at some point. It’s a tribute to cuts I admire.

Warning: Superb as Eisenstein’s, Ozu’s, and Hitchcock’s cuts are, I’m deliberately leaving them out. Too obvious!

Kata and cutting

Okay, Kurosawa is an obvious choice too, but I can’t pass up some of the first outstanding cuts I noticed in his work, back when I was projecting movies for my college film society. The cuts occur during the climactic battle of Seven Samurai (1954).

As is well-known, Kurosawa shot the sequence with several cameras using different focal-length lenses. What is less often acknowledged, I think, is the power of certain cuts as they combine with fixed camera positions. In his last films, Kurosawa would rely strongly on long-lens shots that pan over the pageantry of his crowd scenes, but here he exploits static frames.

In the eye of the battle, Kambei fires his arrow in one shot, and a horseman falls victim to his marksmanship in the next. So far, so conventional. But what’s unusual is that we don’t actually see the arrow hit its target. Kambei fires, and Kurosawa cuts to an empty bit of the town square, churned with mud and dimly visible through horses’ legs. Only after an instant does a fallen bandit skid into the telephoto frame.

The same thing happens when Kambei shoots his second arrow: we must wait for the victim to plunge into the frame.

The result, I think, is a sense of exhilarating inevitability. The camera knows that the horseman will fall, and it knows exactly where. That’s a way of saying that Kurosawa’s visual narration fulfills our expectation, but with a slight delay. The empty frame prompts us to anticipate that the man will be hit—why else show it?—and we have a moment of suspense in waiting to confirm what we expect. Moreover, the force of Kambei’s arm is given us through a principle of Movie Physics: motion communicated to another body is magnified, not diminished, and the fixed frame allows us to see just how far the bodies are propelled. The arrow must have been Homerically powerful if it sends these men to earth with such impact.

Most directors would have panned to follow the victim as, wearing the arrow, he tumbled off his horse and hit the ground. This choice would have been natural given the multiple-camera situation. Instead Kurosawa had his camera operators frame the exact spot the stuntman would hit and wait for the action to hurtle into the shot. The patient expertise of Kambei’s marksmanship has its counterpart in the confidence of Kurosawa’s style. (1)

The moving image, Mr. Griffith, and us

Then there’s Intolerance (1916).

The Musketeer of the Slums is trying to seduce the young man’s wife, the Dear One. He pretends he can retrieve her baby. But his earlier conquest, the Friendless One, has followed him to the tenement, and at the same time the Boy has learned about the Musketeer’s visit. As the Musketeer attacks the Dear One, the Boy bursts in. The two men struggle and the Boy is momentarily knocked out; the Dear One has swooned. So no one sees what really happens next: From the window ledge the Friendless One fires her pistol and downs the gangster. She flees, and the boy believes that he is the killer. He will be charged with the murder.

Here’s what I admire. Griffith sets the situation up with his usual rapid crosscutting—the Musketeer and the Dear One struggling, the Boy returning, and the Friendless One crawling out on the ledge. When the fight starts, Griffith shows the Friendless One growing wild-eyed at the window. She fires once, and Griffith gives the action to us in three shots: a medium shot of her in profile, a medium-long shot of the pistol at the window (irised so we notice it), and a long-shot of the room, as the Musketeer is hit.

Griffith repeats the series of shots when the Friendless One fires again.

This time the Musketeer staggers out to the hall and dies. Neatly, Griffith gives us three more shots, but omits the setup showing the Friendless One. Cut to the curtains again, with her hand waving the pistol, then to another long shot of the room as the gun is tossed in, and finally to a close-up of the pistol landing on the floor.

If you’re looking for a pattern, the pistol in close-up is in effect substituted for the shot of the Friendless One at the start of each cycle. But I’m most interested in the shots of the pistol. The first one at the window goes by at blinding speed—ten frames in the two prints Kristin and I have examined. (2) That works out to a bit more than half a second, if you assume 16 frame per seconds as the projection rate, which was common at the time.

Okay, fussy, but I’ve already confessed that I turn into a frame-counter, when I get the chance. The second shot of the pistol poking out of the curtains, parallel to the first, is also ten frames long. Griffith seems to have been a frame-counter too.

What’s most remarkable is that the long-shot of the pistol being flung into the room is even briefer than these closer views—only seven frames long, or less than half a second at 16fps. As a nice touch, the close-up of the pistol landing in the corner is twice that (15 frames).

In the decades that followed, directors would believe that long shots shouldn’t be cut as fast as close-ups, so the Intolerance passage can strike us as a typical Griffith misjudgment. But I admire his willingness to cut long shots so fast. It certainly creates a percussive accent. In case we didn’t catch the story point, the close-up of the pistol hitting the floor clinches it.

This is the sort of sequence that the Soviet filmmakers probably learned from. They may even have gotten ideas from Griffith’s interspersed black frames (two by my count) before each of the shots of the pistol thrusting out of the curtain. (3)

Behind the desk

Speaking of the Russians, one of my favorite cuts in Pudovkin’s movies comes during a confrontation in The End of St. Petersburg (1927). The somewhat oafish young worker known only as the Lad, who has sold out his comrades, attacks the boss Lebedev in his office. He seizes the boss and shoves him down, jamming him between his desk and the window. We see the action from one angle and then what seems to be an opposing angle.

Actually, this is a big discontinuity. Using the desk, the telephone, and the window as reference points, we can see that in the first shot, the Lad moves in from the left side of the desk to push the boss down. In the second, he has come in from the right side and Lebedev’s head is pointing in the opposite direction. We can see the weirdness of this more clearly if we simply flip one of the frames: now it looks like a consistent change of angle.

Pudovkin has created an impossible event. But the cut gives the strong sense of graphic conflict that the Soviets (not just Eisenstein) sought, creating a kind of visual clatter to underscore the violence of the action. It’s possible that Pudovkin actually flipped a “correct” framing to create the disjunction, as some of his contemporaries did. (4)

Meg, all aflutter

Pudovkin’s cut reminds us that filmmakers can get away with a lot if they change the angle drastically. It’s harder to spot a cheated element or a mismatch if the new shot makes us reorient ourselves. Why does this happen? That’s a subject for research, as I’ll suggest at the end.

Here’s another tricky item. In Kate & Leopold (2001), Kate has brought her time-traveling guest to an audition for a butter commercial. In the studio, he’s behind her as she tries to convince her colleagues to watch him. As she talks, she first watches Leopold in the monitor above them, then swivels to talk to her boyfriend and other suits. The camera positions change 180 degrees.

This drastic shift works to prepare us for a remarkable cut a little later. Kate waves her hand, saying she only needs two minutes. She pivots her body, moving her hand downward.

Cut 180 degrees to a setup similar to the one we’ve seen earlier: She drops her hand to her side as she swings to us.

The gesture is smoothly matched. The only trouble is that it’s executed by the wrong hand. In the first shot Kate is wiggling her left hand, but in the second, it’s her right hand that continues the movement and drops to her hip.

I don’t think that many people would notice this. Indeed, when I first saw the film, I felt a bump hereabouts, but when I watched it over again on DVD, it looked fine to me. Then I watched it again and saw what was wrong. Even then, I thought I might be hallucinating. It’s one of the trickiest cheats I know of, and it’s beautifully done.

The real question is: Why don’t we notice it? We usually say, “Because we’re watching the story and ignore little irregularities.” But that’s not very satisfactory. Why isn’t the wave of Kate’s hand part of the story? We certainly notice it as expressing her attitude—hence as part of the story. And if you didn’t notice the disjunction in my End of St. Petersburg example, the same question arises: Isn’t the Lad’s attack on the boss the very story action we’re watching?

Consider the alternative. If director James Mangold had matched the left hand, it would have to cross the center of the frame as Kate pivots, shifting from screen left to screen right before landing at her hip. It would have been ostentatious and somewhat graceless, and perhaps that would have been distracting. So the mismatch is perhaps a line of least resistance, a compromise–as so many stylistic choices are.

In addition, Kristin suggests that our pickup is made easier by the placement and action of the hand. In both shots it’s quite central and moving in the same direction at the same rate, so that it’s easy to read as a graphically continuous element across the cut.

Perhaps too the fact that we’re switching our position 180 degrees leads us to expect, wrongly, the sort of reversal we get here—the way that we think our reflection in a mirror is the way we really look. And of course the earlier 180-degree switch, in which no mismatch occurs, probably serves to prime us for the shift in orientation this provides.

Mangold doesn’t mention the cut in his director’s commentary on the Kate & Leopold DVD, but when I asked him he said: “I think of shots as blocks, like legos or words. I don’t want them to resolve–come to an end. . . . Movement cuts work as long as the action is somewhat similar. The tough continuity cuts when you have a mismatch are the still ones.” Even if the mismatch here was accidental, it works very well. More generally, like other mismatches this one obliges us to think about what we see and what we don’t see when we watch a movie.

Hawks’ eyes

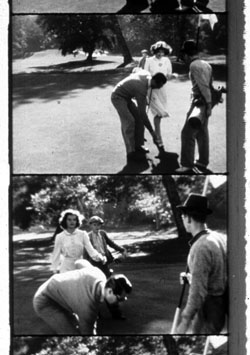

Among the many pleasures of Howard Hawks’ movies are their lovely matches on action. Of course his editors had a lot to do with this, but Hawks clearly had to provide the right footage so that it could be precisely matched. Bringing Up Baby (1938) yields a crisp cut as Susan, perched on the constable’s desk, strikes a match. (I show the cuts from a 16mm print; enough of this video stuff.)

Here Hawks seems to rely on what’s been called the two-frame rule: If you’re going to match on action, overlap the action by two frames to show a bit of the action again. This allows the audience time to absorb the fact of the cut and then to see the action as continuous. But Hawks could be quite cavalier about his matches as well. The golfing scene from Bringing Up Baby is full of wild cuts.

The caddies advance and recede, Susan and David are caught in different postures, and at some cuts they’re striding across different parts of the course. These cuts have a swagger about them, as if Hawks is daring us to spot his outrageous cheats. How many of us do?

All these trompe l’oeil effects can be studied psychologically, and prominent researchers who have tested such effects in the laboratory are attending our 11-14 June meeting of the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image. Dan Levin studies discontinuities in film from the standpoint of “inattentional blindness”; here he’s interviewed by Errol Morris. Barry Hughes of Arizona State University at Tempe has probed the two-frame rule, and he’s talking in Madison as well. Go here for more information; I’ve plugged the event previously here.

Next time, we expect: Secrets of film restoration.

(1) Kurosawa has prepared us for this passage when Kikuchiyo’s sword attacks the bandits earlier in the sequence. There too a shot of his flailing stroke is followed, after a pause on a patch of mud, by a falling horseman. But the calm deliberateness of Kambei’s drawing of his bow enhances the sense of inevitability, I think. Kiku does his damage through furious energy, but Kambei hits his mark thanks to a mature warrior’s almost contemplative precision.

(2) Forget checking these frame counts on DVD. I get several different counts, depending on the player I use. For reasons discussed here, DVDs don’t preserve the original film frames, and in a fast-cut passage you can lose any sense of how many frames the shot lasted.

(3) By the way, Griffith died on 23 July 1948, my first birthday.

(4) For more on this extraordinary movie’s use of discontinuity editing, see Vance Kepley, Jr., The End of St. Petersburg (London: Tauris, 2003).

The show goes on

DB here:

Kristin and I had hoped to blog directly from this year’s edition of Ebertfest (formerly Roger Ebert’s Festival of Overlooked and Forgotten Films), but our blogging software failed us. We could post text but no pictures, and where’s the fun in that? Fortunately, the event was widely covered. The schedule, with very full film notes, is here. You can get a sense of what was happening by checking Jim Emerson at scanners and Peter Sobczynski at Hollywood Bitchslap and Kim Voynar at Cinematical and Lisa Rosman at A Broad View and P. L Kerpius at Scarlett Cinema and Andrew Wells at A Penny in the Well and many others. There is some coverage at the News Gazette, although the most informative stories from the paper aren’t on the net. Then there’s Roger’s own blog, Ebertfest in Exile, which in one entry goes off on an unexpected trajectory….toward Joe vs. the Volcano.

Now that we can again illustrate our entry, we offer you an ex post facto blog, like last year’s, which makes up in bulk for its tardiness. I hope to follow soon with a picture gallery.

This year’s Ebertfest lacked an essential ingredient: Roger Ebert. But Chaz Ebert took over hosting duties superbly, aided by the terrific organizational skills of Nate Kohn and Mary Susan Britt. At every screening, one person or another paid tribute to Roger’s gifts to film culture—his writing, of course, but also his tireless championing of deserving movies that should be brought to wider audiences.

The format of Ebertfest offers something for everyone. Traditionally, the opening night is an older film screened in classic 70mm, a format that’s almost vanished. Past years have included shows of Lawrence of Arabia, Play Time, and My Fair Lady. 70mm looks gorgeous on the vast screen of the Virginia Theatre. This year the film was Kenneth Branagh’s Hamlet, at four hours the most complete version of the play ever put on film. It looked grand.

Another slot is reserved for a silent movie, often accompanied by the Alloy Orchestra. (Part of their armory, including bells, springs, and a thunderstrip, can be found on the left.) Having programmed The Black Pirate, The General, and The Eagle in earlier years, Roger picked von Sternberg’s sumptuous Underworld (1927), which Kristin introduced and led a discussion about. The Alloy boys’ scores are getting more nuanced by the year, and this one did as much justice to von Sternberg’s quiet passages as to the gunplay.

Another slot is reserved for a silent movie, often accompanied by the Alloy Orchestra. (Part of their armory, including bells, springs, and a thunderstrip, can be found on the left.) Having programmed The Black Pirate, The General, and The Eagle in earlier years, Roger picked von Sternberg’s sumptuous Underworld (1927), which Kristin introduced and led a discussion about. The Alloy boys’ scores are getting more nuanced by the year, and this one did as much justice to von Sternberg’s quiet passages as to the gunplay.

Yet another Ebertfest mainstay is a children’s show on Saturday morning, and last year’s wonderful Holes was followed by an unexpected pick—Ang Lee’s Hulk, with the director in attendance. The place was packed, Lee was his charming self, a trio serenaded him, and the audience left well-pleased.

Prime spots are reserved for less-known films, with an emphasis on independent and personal cinema. We saw Tom DiCillo’s Delirious, Sally Potter’s Yes, Joe Greco’s Canvas, and Jeff Nichols’ Shotgun Stories. A highlight for me was Eran Kolirin’s The Band’s Visit, which I’d missed elsewhere. This unassuming, warm, funny movie recalled Tati and 1960s Czech films like Intimate Lighting. Then there was The Cell by Tarsim Singh at a late-night screening, with John Turturro’s Romance and Cigarettes to wrap things up on Sunday. For kaleidoscopic commentary on all these, see the above-mentioned weblogs.

Princely contradictions

I hadn’t seen Hamlet in 70mm in its initial 1996-1997 run, and at first the idea of taking this fairly intimate piece to a wide-film format seemed counterintuitive. But on the Virginia screen the film lost none of the play’s intensity and it gained a welcome monumentality. The central set, the Danish throne room as a gigantic hall of mirrors flanked by a warren of corridors and fissured by secret passageways, is made for the wide image.

Scale of time also matters. By playing the full version, Branagh can give full weight to the father/ son parallels that riddle the play. If Olivier’s Hamlet was about a son’s love for his mother, Branagh makes the play about the strife between fathers and sons, with women caught in the middle. Hamlet Sr./ Hamlet Jr., Claudius/ Hamlet, Jr., Polonius/ Laertes, old Norway/ Fortinbras, and even the Player’s speech about the murder of Priam: the parallels are in Shakespeare’s text but played out at proper length they snap into sharp relief. Once Laertes is off to Paris, Polonius makes sure he’s spied on, just as Claudius orders Rosenkrantz and Guildenstern to watch Hamlet. In his turn, Hamlet assigns Horatio surveillance duty during the play-within-a-play (a piece of action nicely caught in the opera glasses that Branagh’s choice of period allows). Branagh’s decision to emphasize the military politics around Fortinbras’ march into Denmark helps justify the 70mm format and his decision to set the action in late nineteenth-century Europe; it also allows him to expand, through crosscutting set up early in the movie, the plot of another son at odds with his father.

Sex is important in this game. Branagh presents flashbacks to Hamlet and Ophelia in bed together, accentuating the prince’s later indifference and motivating her despair at his rejection. Not that the fathers don’t clock some mattress time too. Claudius the urbane politician becomes an infatuated newlywed, and Derek Jacobi gives to my mind a definitive performance. Even Polonius, usually treated as a pompous ass, smokes worldly little cigars and has a drab tucked into his bed, so that his advice to Laertes and Ophelia about proper conduct becomes not only patronizing but hypocritical.

During the Q & A, Timothy Spall and Rufus Sewall emphasized something that Branagh explains on the DVD set: the need to create ensemble performances out of footage shot at different times. Sewall (a dark and scary Fortinbras) was filmed in a few days, before full-blown production, with his bits cut into the film at intervals. Robin Williams, as Osric, was also filmed out of continuity; there are scarcely any shots of him in the same frame as other players.

During the Q & A, Timothy Spall and Rufus Sewall emphasized something that Branagh explains on the DVD set: the need to create ensemble performances out of footage shot at different times. Sewall (a dark and scary Fortinbras) was filmed in a few days, before full-blown production, with his bits cut into the film at intervals. Robin Williams, as Osric, was also filmed out of continuity; there are scarcely any shots of him in the same frame as other players.

Spall, a temporizing Rosenkrantz, was present for much more of the filming and was eloquent in explaining how shooting in long, wheeling takes demanded great precision from the actors—hitting marks, using body language, and timing speeches carefully.

Branagh put the bulky 70mm camera on a dolly, then reinforced the studio floors so that no tracks or boards were necessary; the camera could glide anywhere. “Walk and talk” technique, which I’ve blogged about before, comes home to roost in a Shakespeare film; Branagh wanted continuous shots so that the audiences could follow the flow of the speeches, and it works very well.

In fact, Branagh’s editing varies in a patterned way across the play. Acts I and III are briskly cut, averaging about 5 seconds per shot. Acts II and IV rely on much longer takes, typified by the tracking-shot arabesques, and they average 10-11 seconds per shot. And Act V? Here, as you might expect, Branagh pushes the pace to suit the converging plotlines and the burst of poisonings at the climax: the average shot runs about 3 seconds. This seesawing rhythm helps sustain viewer interest across four hours, and it shows an unusually geometrical approach to a movie’s overall architecture.

In his program review, Roger points out that the play remains deeply mysterious, even in a production as lucid and buoyant as Branagh’s. Hamlet is of course one of the most fascinatingly inconsistent characters in literature. I’ve read the play probably a dozen times and seen many film versions of it, and I’m inclined to think that in Hamlet Shakespeare is experimenting with how indeterminate a character can be and still be intelligible to us. It’s not that he’s indecisive; we have to decide what he truly is, and Shakespeare makes our task very hard.

All the other characters in the play are complicated but consistent. Only Hamlet seems to reinvent himself at every entrance. He tells us that he will put on an “antic disposition,” but before he’s gotten very far with his fake madness, he tells Rosenkrantz and Guildenstern of his strategy, knowing that they are likely to report it to Claudius. This has the effect of letting Hamlet behave any way he wants, sincere or duplicitous, calculating or mad. When he’s around others, he’s always “on,” and this makes his true nature and purposes difficult to divine.

I liked Branagh’s idea of having Hamlet consulting a book on demonology, for in a revenge tragedy the protagonist has to be sure that the aggrieved spirit urging revenge isn’t a demon in disguise. More generally, the Victorian milieu lets Branagh give us a truly bookish Hamlet, one who retreats to his stuffed library when overcome by the strife unfolding in the vast throne room. At the same time, that library contains players’ masks and a curious miniature theatre that Hamlet toys with thoughtfully. He lives among books, but also among images of pretense and deceit.

I liked Branagh’s idea of having Hamlet consulting a book on demonology, for in a revenge tragedy the protagonist has to be sure that the aggrieved spirit urging revenge isn’t a demon in disguise. More generally, the Victorian milieu lets Branagh give us a truly bookish Hamlet, one who retreats to his stuffed library when overcome by the strife unfolding in the vast throne room. At the same time, that library contains players’ masks and a curious miniature theatre that Hamlet toys with thoughtfully. He lives among books, but also among images of pretense and deceit.

The questions tease you right to the end. Hamlet finds Laertes’ plunge into Ophelia’s grave overdramatic, but he goes on to declare that he himself loved her with the strength of forty brothers. Before the climactic duel, Hamlet apologizes to Laertes (“I have shot my arrow o’er the house/ And hurt my brother”), but it seems almost bad faith, given all the misery he has helped cause. Is this a morally obtuse sincerity, or another masquerade? It’s this Hamlet, reliably unpredictable, that Branagh’s manic-depressive performance brings home so forcefully.

The unwitting wisdom of the suits

It’s common to say now that the 1970s was the last great era in American cinema, followed by the degradations of the blockbuster 80s, but that remains little more than PR. Putting aside the “revolution” of the 1970s, which seems to me overrated, I’ll just offer the opinion that the 1980s brought us many worthy films, some of them quite daring. For example, one of the sweetest “little movies” of the era is Bill Forsyth’s Local Hero (1983).

It’s a comedy, at once dry and warm, about an oil executive sent to buy a small Scottish town and beachfront in preparation for the installation of a pumping rig and refinery. Forsyth’s script reverses the cliché. The townsfolk, far from clinging to their beloved tradition, are in fact anxious to sell and look forward to being rich. The young executive, Mac, doesn’t try to drive a hard bargain but settles into the rhythm of a life different from that he has known. His boss, a passionate amateur astronomer, surprises everyone with his final decision about the deal. You might call Local Hero one of the first films about the clash of global capitalism and community values, but though that’s accurate, the schematic formula doesn’t capture the understated humor and humanity of Forsyth’s treatment.

Forsyth is at Ebertfest for a screening of his no less brilliant Housekeeping; see Jim Emerson’s eloquent and poised review here. But I wanted to ask about Local Hero. The Scottish village is rendered with the affectionate good humor we find in Ealing comedies, and Forsyth mentioned that after he’d made the film he discovered an Alexander Mackendrick movie, The Maggie (1955), that prefigured his. For me, there were echoes of Jacques Tati in the long-shots and sound gags, and Forsyth confirmed that one of the formative films in his youth was M. Hulot’s Holiday, screened by an indulgent school head.

Forsyth talked about certain choices he made. The Mark Knopfler score, bringing together Scottish tunes and a Texas twang, helped open out the film in a way that a more conventional lyrical score would not. Forsythe talked as well about the final shot, one of the most satisfying I’ve ever seen. The original cut ended with Mac returning to his Houston apartment and staring out at the dark urban landscape—beautiful in its own way, but very different from the majesty of the Scottish shore. There the original film ended, but the Warners executives, although liking the film, wanted a more upbeat ending. Couldn’t the hero go back to Scotland and find happiness, you know, like in Brigadoon? They even offered money for a reshoot to provide a happy wrapup. Forsyth didn’t want that, of course, but he had less than a day to find an ending.

Forsyth talked about certain choices he made. The Mark Knopfler score, bringing together Scottish tunes and a Texas twang, helped open out the film in a way that a more conventional lyrical score would not. Forsythe talked as well about the final shot, one of the most satisfying I’ve ever seen. The original cut ended with Mac returning to his Houston apartment and staring out at the dark urban landscape—beautiful in its own way, but very different from the majesty of the Scottish shore. There the original film ended, but the Warners executives, although liking the film, wanted a more upbeat ending. Couldn’t the hero go back to Scotland and find happiness, you know, like in Brigadoon? They even offered money for a reshoot to provide a happy wrapup. Forsyth didn’t want that, of course, but he had less than a day to find an ending.

The movie makes a running gag of the red phone booth through which Mac communicates with Houston. Forsyth remembered that he had a tail-end of a long shot of the town, with the booth standing out sharply. He had just enough footage for a fairly lengthy shot. So he decided to end the film with that image, and he simply added the sound of the phone ringing.

With this ending, the audience gets to be smart and hopeful. We realize that our displaced local hero is phoning the town he loves, and perhaps he will announce his return. This final grace note provides a lilt that the grim ending would not. Sometimes, you want to thank the suits—not for their bloody-mindedness, but for the occasions when their formulaic demands give the filmmaker a chance to rediscover fresh and felicitous possibilities in the material.

Salvation through self-punishment

Another outstanding film of the 1980s is Paul Schrader’s Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters (1985), which he brought to Ebertfest in a sparkling print. Schrader is one of two American film critics who became major directors (Peter Bogdanovich is the other), and there’s little doubt that he’s the most cerebral and theoretically inclined of that group known as the Movie Brats. Even if he hadn’t written milestone screenplays (Taxi Driver, Raging Bull) and made provocative films (Blue Collar, Hard Core, Affliction), he would be remembered for his critical writing. A trailblazing essay on Joseph H. Lewis, “Notes on Film Noir,” the essay on the yakuza film, and the book Transcendental Style in Film (1972) made Schrader a distinctive voice in American film culture. Fortunately you can now read his entire oeuvre online at paulschrader.org.

While the youthful Schrader expresses admiration for Bonnie and Clyde and The Wild Bunch, he’s no cheerleader for the New Hollywood. It’s bracing to watch him tear Easy Rider and Alice’s Restaurant limb from limb. The website displays each article in situ, on its original page of print. Since he wrote for many alternative weeklies, ads for bongs and day-glo paint lie alongside Schrader’s reflections on Bresson and Boetticher.

Although I also admire Patty Hearst, Mishima is my favorite Schrader-directed project. I think it’s one of the most artistically courageous films in American cinema. Putting the dialogue almost entirely in Japanese and focusing on a writer few Americans know, it compounds its difficulty with a daunting structure. On one axis, we get four chapters: Beauty, Art, Action, Harmony of Pen and Sword. On another axis, there are three interwoven strands: an account of the final day of Mishima’s life, when he seized control of a general’s office in order to address the garrison; a chronological biography, from his childhood to his adulthood; and stylized, efflorescent scenes taken from three Mishima novels. All these strands knot in the film’s final moments, when Mishima commits seppuku in the office and we see the culmination of the action shown in the novels’ tableaus. A “cross-hatched” structure, Schrader calls it.

The three strands are kept distinct through some technical markers: black and white for the biographical scenes, cinema-verite color for the 1970 attack on the garrison, and stylized color and setting for the extracts from the novels. Schrader explained that he had originally wanted to use video for the novel scenes, but his brilliant production designer Ishioka Eiko told him that the results might not be effective. Instead, she supplied designs of a dreamy radiance.

At the same time, both the biographical scenes and the tableaux take us through different eras of Japanese history, but in a way that sharpens comparisons among them. In the 1930s the boy Mishima glimpses a female impersonator at the kabuki theatre, but in his novel of the period, Runaway Horses, the young men formulate their plan to restore the emperor through an attack on corrupting capitalists. The sets for Kyoko’s House have, Eiko explained, ugly design because in the 1950s the Japanese were copying ugly American designs (though the results look pretty ravishing onscreen).

Schrader wanted to avoid the classic plot trajectory of a hero overcoming obstacles. He sought instead to present the way that a person’s life “becomes more and more fascinating, but you never really understand it.” The shuffling of chronology let him juxtapose different aspects of Mishima’s nature. The man wasn’t exactly contradictory, Schrader says, but rather “compartmentalized”: He could keep his aesthetics, his homosexuality, his militarism, and his childhood distinct, and the film aims to show these different facets of his career.

Nevertheless, I’d argue, the film has a marked trajectory. “Perfection of the life or of the art?” Yeats asked. Schrader’s Mishima wants both, together. He seeks to fuse physicality (eroticism, violence, endurance of pain) with spirituality (given as the realm of art). The emblematic image is the poem written in a splash of blood. He finally realizes that for him this fusion can come only in death, because his life has come to embody, literally incarnate, his literary themes and techniques.

Nevertheless, I’d argue, the film has a marked trajectory. “Perfection of the life or of the art?” Yeats asked. Schrader’s Mishima wants both, together. He seeks to fuse physicality (eroticism, violence, endurance of pain) with spirituality (given as the realm of art). The emblematic image is the poem written in a splash of blood. He finally realizes that for him this fusion can come only in death, because his life has come to embody, literally incarnate, his literary themes and techniques.

Schrader’s film enacts the blending of art and life in its very imagery. At the climax, in the biographical strand Mishima climbs into a jet and the black-and-white imagery gains radiant color as he stares into the sun. The shift brings the biography up to 1970, and so provides a transition to the color footage of the writer’s last day, but it also recalls the opening credits, with the sun rising, and the closing shot of the cadet Isao about to slash himself.

Schrader regrets the transition showing Isao running to the beach, because the imagery shifts from Ishioka’s stylized world to something more realistic (albeit with glowing amber rocks). So for the upcoming Criterion DVD release he has fiddled with the final shots so that the sun and sky look far more abstract. Evidently he wants the world of art and the world of life to remain stubbornly apart—denying to his film what his protagonist yearned for.

You might object that the film’s formal intricacy and specialized themes make for a fairly chilly experience. It isn’t a wildly emotional movie, that’s true; it has some of that ceremonial, contemplative quality you get from a Philip Glass opera, which provides a theatre of pictorial attitudes rather than action. (For an example, see coverage of the current Met production of Glass’s Satyagraha.) No coincidence that Glass provided the score for the film, which he wrote without seeing any footage and which Schrader cut and shuffled to provide cues. Glass obligingly rescored the film to fit the musical collage Schrader wanted.

The film provides a visceral and a sensuous experience, but it doesn’t carry you off on waves of emotion. It will never be popular on a massive scale, because it makes almost no concessions to what people like in biopics. But if you can adjust yourself to a solemn celebration of blood and beauty, Mishima offers unparalleled rewards.

More from Schrader

“Inspiration is just another word for problem-solving.”

Schrader’s intellect never lets up. What other filmmaker could produce such a thoroughly informed academic case as he does in the 2006 “Canon Fodder” (available on his site)? One on one, I peppered him with questions and he answered with seriousness and subtlety. Two themes ran through his comments: his approach to direction and his view that cinema is dead.

On his directing: Until his last project, he embraced the “well-made film.” He shoots with a single camera, and plans his takes cut to cut. (That is, not a lot of coverage from many angles that will be winnowed out during editing.) He doesn’t storyboard because he wants to develop the staging organically on site. He visits the set, tries out blocking with the actors and DP, then decides on the spot about the breakdown into shots. For the Temple of the Golden Pavilion scenes of Mishima, like the one above, he and cinematographer John Bailey played “dueling viewfinders,” pacing around the actors to test points of view and then settling on tracking shots which incorporated the best angles.

But for his latest project, Adam Resurrected (2008), Schrader switched to a rougher style. Now, he says, he uses two cameras and he likes the bouncing and swaying frame yielded by the Bungee Cam. “I’m sick of the well-made film.”

On new media: Schrader’s stylistic turnabout comes from his conviction that cinema, “the dominant art form of the twentieth century,” is coming to an end. Today’s audience demands new forms of moving-image media. Thanks to television, young people have seen every conceivable story, so narrative is “exhausted” as an expressive resource. They expect their media products to be free, available on demand, and interactive. The result is a challenge to traditional media on every front: financial, cultural, and artistic.

Schrader looks to the Internet as not just an intriguing option but film’s destiny. So while he is planning a traditional “three-act” film, he also has written a screenplay for a 75-minute Net movie. In his essay, “Canon Fodder,” he predicted the end of traditional cinema but thought that he could keep going before the revolution. Now, he says, the sun is setting faster than he expected and if he wants to make more films he has to adjust.

I’m no prophet, but I don’t share his beliefs about the imminent collapse of traditional cinema. I also think that Web-based films, with viewers tempted to browse and graze and fast-forward, will limit aesthetic options. The computer monitor is not as hospitable to contemplative cinema, which demands that the audience patiently submit to unfolding time. When I worried at a panel that an Ozu or a Bresson could not have originated in the age of YouTube, he told me, “Get over it, David!” Though we disagree, talking with him was terrifically stimulating. I left with the hunch that Schrader will continue to devise some characteristic provocations for new media, for which we should be thankful.

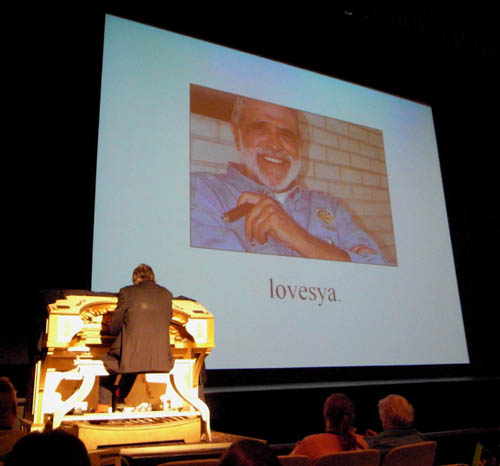

Envoi

Dusty Cohl was one of the mainstays of Ebertfest, as well as the founder of the Toronto Film Festival and a shot in the arm to world film culture. He died last fall. He was honored by several events at this year’s festival, notably the biographical film, Citizen Cohl: The Untold Story, by Barry Averich (The Last Mogul). On my first visit to Ebertfest, the tough, salty guy with the quick grin and the cowboy hat immediately made me feel welcome, and he did the same when Kristin came along the following year. Everyone whose life he touched was grateful for Dusty’s generosity of mind and spirit.

A glimpse into the Pixar kitchen

DB here:

On some of Bill Kinder‘s business cards, the I in PIXAR is represented by Buzz Lightyear, the blustery, not-too-swift astronaut of Toy Story. It’s a typical gesture of self-deprecation from the studio that showed that computer animation didn’t have to be just plastic surfaces and mechanical expressions. Pixar is cool, geeky, and warm all at the same time. Its films are both smart and soulful, made by movie fans for movie fans, and for everybody else. Like the best of the Hollywood tradition, Pixar movies have the common touch and still offer the most refined pleasures.

Kristin and I have already written admiringly about Pixar on this site (here, here, and here). It’s quite likely that this studio is making the most consistently excellent films in America today. So we were delighted when our colleague Lea Jacobs arranged for Bill to come to the University of Wisconsin—Madison last fall. He toured our new Hamel 3-D media facility, met with faculty and students, and gave a talk, “Editing Digital Pictures.” Bill is Director of Editorial and Post-Production, a position that gives him an encompassing view of the Pixar process as he champions the efforts of the editors and their teams as key creative contributors.

Kristin and I have already written admiringly about Pixar on this site (here, here, and here). It’s quite likely that this studio is making the most consistently excellent films in America today. So we were delighted when our colleague Lea Jacobs arranged for Bill to come to the University of Wisconsin—Madison last fall. He toured our new Hamel 3-D media facility, met with faculty and students, and gave a talk, “Editing Digital Pictures.” Bill is Director of Editorial and Post-Production, a position that gives him an encompassing view of the Pixar process as he champions the efforts of the editors and their teams as key creative contributors.

A graduate of Brown, where he studied with our old friend Mary Ann Doane, Bill is like Pixar movies—intellectual, good-natured, energized, and adept at connecting with people. He started his career in news-gathering and TV editing before moving to work at Francis Ford Coppola’s American Zoetrope, in the days of Jack (1996) and the uncompleted Pinocchio project. He joined Pixar in 1996, while they were finishing Toy Story. When the success of A Bug’s Life enabled Pixar to move to a purpose-built facility in Emeryville, Bill went along.

Whittling vs. building

I’ve always been uncertain about what an editor does in the animation process. Since every shot is planned and executed in detail, what can be left for an editor to do? Bill started from that question. No, editing digital animation isn’t just a matter of cutting off the slates and splicing perfectly finished shots together.

As in live-action filming, the animation editor is working with dozens of alternate versions of every shot. The reason is that at Pixar, there are roughly five phases of production: storyboarding, layout, animation, lighting, and effects/ rendering. Each one generates footage that has to be cut together.

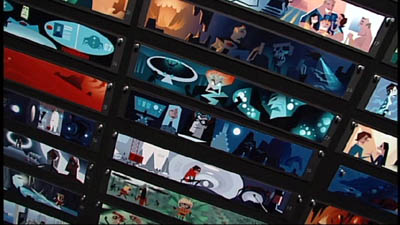

The static storyboards, for instance, present poses, expressions, and movements against a blank background. They are assembled in digital files that can be played back as if they were a movie. In order to plan the next phase, the resulting “footage” has to be edited, and choices are made at every cut. And each scene is storyboarded at least five different ways, with many variations of action and timing. A single film uses up to 80,000 boards!

At the next phase, layout, the scene’s overall action is planned. Layout artists develop the staging of each shot, testing different backgrounds and camera angles with the editors. Again, the alternatives have to be assembled and cut in various combinations.

Whittling versus building, Bill called it. The live-action editor gets a mass of footage that has to be triaged, but the animation editor is building and tuning the film from the start. Editing operates at each phase, from storyboarding to final rendering. This “almost overwhelming iteration,” as Bill called it, demands that the editorial department hold all the alternatives in its collective mind at once. Add to this the fact that Pixar can take up to five years to produce a film, maintaining several editorial teams to cover projects at different degrees of completion. When you realize that all this brainpower and bookkeeping are necessary for even the simplest shot, you appreciate the felicities of the finished product even more. These people make it all look easy.

Continuity and the viewer’s eye

Bill explained that digital animation occasionally requires something like live-action coverage. (1) Action sequences with fast cutting need to be spatially clear, and “chase scenes can be hard to board.” So sometimes the layout artists create master shots and closer shots from different angles that the editor will pick out and assemble, live-action fashion.

Like live-action editors, Pixar editors have to keep an eye on continuity of the objects in the frame. Because each shot is reworked across many phases, items of the set, lighting, color, atmosphere, effects and rendering have to be maintained, on many layers or levels of the program. (I gather it’s like the layers in PhotoShop.) Sometimes a layer, whether a prop, character, or set element, fails to “turn on” and so a discontinuity can crop up. A finished Pixar film typically has 1500 shots or more, so there’s a lot to keep track of.

In another carryover from live-action features, Pixar plots are conceived and executed in three discrete acts. It’s not only a storytelling strategy but a convenience in production. Rather than waiting until the entire film is done to examine the results of the different phases, the filmmakers can finish one act ahead of the others in order to troubleshoot the rest.

I’ve studied how filmmakers compose the image in order to shift our attention (2), so I was happy to hear that this process is of concern to the Pixar team. “Guiding the viewer’s eye,” Bill called it. He explained that in looking at storyboards and animated sequences, his colleagues sometimes use laser pointers to track the main areas of interest within shots and across cuts, especially when characters’ eyelines are involved. Nice to see that sometimes academic analysis mirrors the practical decisions of filmmakers.

The auteurs of Pixar

What makes Pixar films so fine? Bill supplied one answer: It’s a director-driven studio. As opposed to filmmaking-by-committee, with producers hiring a director to turn a property into a picture, the strategy is to let a director generate an original story and carry it through to fruition (aided by all-around geniuses like the late Joe Ranft). Within the Pixar look, John Lasseter’s Toy Story 2 and Cars are subtly different from Brad Bird’s The Incredibles and Ratatouille or Andrew Stanton’s Finding Nemo and upcoming Wall.E.

Bill covered many other fascinating topics, including the importance of sound (“the animated film’s nervous system”). But I’ll end with some pull-quotes from Bill’s talk.

*Francis Ford Coppola: “No film is ever as good as its dailies or as bad as its first assembly.”

*Gary Rydstrom: “Film sound is the side door to people’s brains.”

*Bill himself: “Editing is just writing, but using different tools.”

We’re grateful to Bill for his visit and look forward to seeing him again. Goes to prove what we’ve said before: Popular American filmmaking harbors many of the most intelligent, sensitive, and generous people you’ll ever find.

(1) In live-action production, coverage involves shooting a master shot of a scene that shows the entire action. Then parts of the action are repeated and filmed in closer views. This allows the editor several options for cutting the scene together.

(2) I talk about this in Chapter 6 of On the History of Film Style and throughout Figures Traced in Light. See also Film Art, pp. 140-153, and this blog here and here.

PS: Another glimpse into the kitchen: Bill Desowitz reports on Wall*E at Animation World. Now Pixar is trying to emulate the look of 70mm. And there’s footage from Hello, Dolly! in there? All the signs point to another nutty, dazzling achievement.