Archive for the 'Film technique: Editing' Category

Truly madly cinematically

DB here, still in Hong Kong:

You are a film director. How do you convey to an audience that a character mysteriously sees hidden personalities in other characters?

Filmmakers are problem-solvers, at least sometimes, and I’ve argued elsewhere that we can often explain their creative choices as efforts to pose and solve problems. I ran across an intriguing example during my stay here in Hong Kong. I interviewed Tina Baz, the editor for Johnnie To’s film Mad Detective (2007), which I blogged about from Vancouver in October.

Tina has a fascinating history. Lebanese and French-educated, she attended art school in Beirut and film school in Paris. Armed with a maitrise from the Sorbonne, she began editing. Over a dozen years, she has built up an impressive career. She was editor on The Mourning Forest (2007), A Perfect Day (2005), and several other high-profile projects.

Tina has a fascinating history. Lebanese and French-educated, she attended art school in Beirut and film school in Paris. Armed with a maitrise from the Sorbonne, she began editing. Over a dozen years, she has built up an impressive career. She was editor on The Mourning Forest (2007), A Perfect Day (2005), and several other high-profile projects.

Mad Detective was Tina’s first film for Johnnie To, as well as her first experience with the Hong Kong crime genre. She was accustomed, she says, to the more psychologically-driven narratives of French cinema, and she had to work in a new way during the seven weeks it took to edit the film. This is an unusually long editing time for Hong Kong filmmaking, and it reflects the complicated tasks this film set her.

If you haven’t seen Mad Detective, you will probably want to stop reading. The scenes I’m discussing come fairly early in the film, but they do contain some surprises you might not want to know about in advance.

Headquarters

The rough cut of the film, adhering closely to Wai Ka-fai’s script, displayed a complicated flashback structure. The plot began fairly far into the action and then jumped back to establish the exposition. Central to that exposition is the film’s premise: Detective Bun, played by Lau Ching-wan, solves cases by extraordinary telepathic/ intuitive/ visionary insights. But the original cut blurred that concept, mixing it with an early revelation of the identity of the villain, a corrupt cop named Ko Chi-wai, and background on Bun’s young partner Ho. How to cut through the clutter?

The first step to a solution was to straighten out the chronology and to focus tightly on Bun from the start. The audience needed to understand the film’s eccentric psychological premise—specifically, that Bun’s gift allows him to detect multiple personalities buried within another person.

In talking with me, Tina went over three scenes that establish Bun’s peculiar abilities. (1) The sequences furnish striking examples of how filmmakers find precise technical solutions to storytelling problems. This trio of scenes also follow Hollywood’s Rule of Three. According to this, a key piece of information should be presented three times, preferably in different ways. (2) (Once for the smart people, once for the average people, and once for slow Joe in the back row.) Tina smiled. “This is not something that French directors would say.” The Rule of Three can be seen as another aid to solving the broad problem of clarity—making sure that the audience understands the story.

Discussing all three scenes adequately would take a lot of space and require dozens of stills, so I’ll concentrate on the first two. These should suffice to show how the filmmakers solved a tricky narrational problem.

The first scene takes place in police headquarters and it’s the simplest. It starts with Bun absorbing details of Ho’s investigation. We hear, offscreen, a whining woman complaining that a maniac can’t solve a case. We think at first that it’s the voice of another cop, but after a second complaint from offscreen, Bun looks up. Cut to the whining woman, who stands among the cops.

Bun rises and walks to a pudgy cop who grins ingratiatingly. Now cut from the cop to the whining woman, in a similar composition against the same background.

An over-the-shoulder shot presents Bun staring as we hear the fat cop asking, “Do you recognize me?”

After the fat cop flatters him, Bun head-butts him. Bending over the fallen cop, Bun says, “Shut up. I see and hear you, bitch!” Cut from the bloody-nosed cop to Bun to the bloody-nosed woman.

After Ho dismisses the team, Bun slowly approaches and confides: “I can see the inner personalities of a person” (below). This line of dialogue crystallizes what we’ve seen–the bitchy woman inside the ingratiating man–and prepares for the next few scenes.

On the street

The second vision scene is more complicated, and Tina had several discussions with To and Wai about whether to include it. The new problem, based on the key line above, is to establish that Bun can see not one but several hidden personalities in Ko, the crooked cop. How can this premise be shown?

The major scene coming up shows the two partners confronting Ko at a restaurant. There Bun will envision some of Ko’s inner people manifesting themselves. But there’s also dramatic conflict to be conveyed in the scene, which culminates in a beating in the men’s room. Again, too much information! Tina, To, and their colleagues decided to include an intermediate scene, one that had little dramatic consequence but got audiences more comfortable with the premise.

Ho and Bun trail the suspect along the street, first in a car and then on foot. The results have the kind of precision I’ve pointed to in another Milkyway film, PTU.

In the car, Tina’s cutting establishes the differences between the two cops’ points of view. A two-shot of Ho and Bun yields to a straightforward POV shot of Ko striding along the sidewalk.

But a cut to Bun watching is followed by a shot of seven people in Ko’s place. In a nice instant of uncertainty, a few heads emerge from behind a parked van and are only partially visible. At first glance we might take them for passersby walking ahead of Ko.

Before we can fully identify this band of spirits, and as the car draws abreast, a cut to Ho watching leads to a shot of Ko, whistling.

Another cut to Bun, and now we see, as he apparently does, a full view of the platoon of Ko-personalities striding along whistling.

This mildly wacko variant is consistent with the narration’s mixed attitude toward Bun’s visions: are they supernatural insights or hallucinations?

Bun leaps from the car and pursues Ko’s band of personalities, and a new variation shows him and them in the same frame. But this is re-framed by Ho’s POV, which reasserts that to anyone but Bun, Ko is all by himself.

Abruptly, the visions halt and turn, staring at Bun. By now we are trained to understand what’s happening without a corresponding objective shot of Ko. Ko, we infer, has turned around to check on who’s following him.

Likewise, we can grasp the image of Bun passing through the group of figures as simply Bun walking past Ko.

At this point, we have no need to see the objective action. To and Tina have stressed the absence of an objective view by showing Ho, in the background, looking in another direction and missing this byplay (above). After Bun has passed, the troupe of avatars walks in their new direction, and then we get the objective shot of them “as” Ko.

This effect is anchored when Ho turns and notices Ko going into the restaurant.

As a meticulous touch, Ko’s departure from the frame reveals Bun still walking away in the distance. The geography is simple and impeccable.

The idea of seeing “inner personalities” has been made concrete while undergoing a lot of variation. Sometimes shots of the spirits are sandwiched between shots of Bun looking; sometimes not. Sometimes we have Ho to verify what’s really happening, but sometimes not. And sometimes Bun can be in the same frame as the avatars. Otherwise, Tina points out, the scenes would become boring.

Once the street scene has laid out how Bun sees Ko Chi-wai, the next scene, unfolding in the restaurant and a men’s toilet, can play with the premise still more. Tina explains that the creative team constantly asked, “How far can we go with Bun’s point of view, his vision?” Quite far, it turns out. The premise gets varied further across the whole movie, in imaginative ways. Which is to say that a solution to a problem can pose new problems, which the filmmakers go on to grapple with.

In our discussion, Tina noted that the street scene goes beyond simply giving us information. There’s a disquieting emotional effect when the spirits turn and confront Bun, their expressions ominously blank. Finding a solution to a creative problem often yields an unexpected payoff like this.

Bonus features

As I indicated, I can’t pursue the felicities of the restaurant scene here. Instead, here are some quick final thoughts.

*Mad Detective shows once more the power of basic techniques of performance (e.g., the act of looking), framing, and editing. To and Wai have no need for fancy CGI effects to evoke the “inner personalities” of Ko or the other cop. Our minds make the necessary connections. Lev Kuleshov would have admired the engineering economy of this sequence.

*In passing Tina and I talked about actors’ eyes, a special interest of mine. (3) Tina had noticed that actors try not to blink. She agreed that blinks pose problems for editors: “Blinking is very hard on cutting.” She remarked that Elia Suleiman would strain to keep from blinking until tears flowed from his eyes.

*Mad Detective was signed by both Johnnie To and Wai Ka-fai, but their joint projects are usually filmed by To, with Wai supplying the script and consulting as production proceeds. Tina confirms To’s habit of shooting with the whole scene’s layout in his head, using very few takes per shot and not a lot of coverage. The film is “very pre-cut,” she says. You can see this, I think, in the way To relies on matches on action and ends one shot with something that prepares you for the next one.

*To follows Hong Kong tradition of adding all the sound in postproduction. This makes for economy and efficiency in shooting, but it also gives HK films the fluency of silent cinema. The filmmaker gains a freedom of camera placement and is encouraged to think about how to tell the story visually. Tina and Shan Ding, To’s all-around assistant, pointed out that sync sound might make the director depend more on dialogue and static conversation scenes. Still, I think that sometimes they wish for a scene shot with direct sound.

*As with many Milkyway films, several scenes were filmed at the company headquarters. An earlier blog here discussed the ambitious rooftop set for Exiled. For Mad Detective, the fistfight in the restaurant toilet was filmed in the main men’s room of the Milkyway building, with a fake urinal added. Shan Ding provides documentation in the snapshot below, using a double for Lam Suet.

To come: Another Milkyway interview, this one with ace sound designer Martin Chappell. And a final batch of impressions from the Hong Kong International Film Festival, which ends on Sunday.

(1) If you know Mad Detective, you’re aware that Bun’s ability to discern hidden personalities is displayed in an earlier scene. But given the way in which that story action is presented, we can’t say that that his powers are established there. This scene is one of many clever narrational stratagems in a film that benefits from being rewatched.

(2) See Bordwell, Janet Staiger, and Kristin Thompson, The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1985), 31.

(3) Laugh if you must, but I wrote an essay about this. “Who Blinked First?” is available in Poetics of Cinema.

Tokyo choruses

DB here:

I’ve had a terrific time since I arrived late last Saturday. The only thing that could have improved it would be the discovery that there was a Japanese town named Bordwell. If it could happen to Barack, why not me?

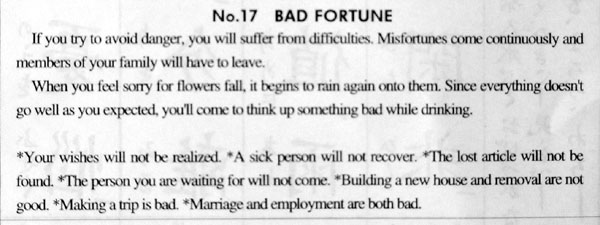

Actually, I know why not. On Sunday, a trip to a temple yielded a promise that nothing good would come on any front.

Pretty dire. Yet I press on, foolishly trusting that meals will be tasty, the city will shake me up, and three fine sorts of things will grace the first phase of my stay: the symposium, the movies, and my companions. Still, I vow to avoid thinking up something bad while drinking.

The conference

I came for a symposium at Waseda University, Stage to Screen. For three days local scholars delivered papers and comments about how cinema related to theatre.

Young researchers have done thorough work on the relation of Japanese cinema to the culture’s lively theatrical traditions. Usai Michika explored a topic that’s always fascinating–the benshi, the person who accompanied silent film with commentary and dialogue. She found a remarkable poster from the Waseda Theatre Museum collection illustrating many short films, and through diligent archive work she was able to identify most of the films. Although the poster came from 1899, the films were all pre-1896. Ogawa Sawako gave a thorough examination of how films were influenced by kodan, a sort of novelistic oral recitation. It turns out that kodan stories were at least as important as kabuki plays as sources of Japanese film, well into the 1920s. Shimura Miyoko studied later forms of rensa-geki, the mix of live performance and film that was fairly common in the silent era. She showed that there was a resurgence of it in the early 1930s, with sound cinema.

Western cinema attracted attention as well. Kataoka Noburo analyzed the relationship between Samuel Beckett’s Play and his Film, directed by Alan Schneider and starring Buster Keaton. Our host Professor Komatsu Hiroshi gave a talk called “Actors without Bodies,” suggesting the quasi-supernatural qualities of early film. He surveyed cinema’s links to the phantasmagoria shows of the French magician Robertson. He also explored how sound recordings synchronized with early films evoked theatre but didn’t exactly correspond to stage performance techniques–another form of bodiless acting.

There were two keynote addresses as well, one from Yuri Tsivian and one from me. Yuri was, as usual, energetic and infectious. Our talks naturally overlapped when we touched on the 1910s, and we had some good conversation about films of that era offstage as well as on. Above you see Yuri analyzing, with his usual body English, a scene that he has made famous–a play with mirrors in Bauer’s King of Paris (1917).

The films

The last day of the symposium was devoted to two films that show how world film language changed between the mid-1910s and the early 1920s. Goro Masamune (1915) is a complicated tale about a swordsmith and the dramatic results of his mysterious parentage. It offered a stringent version of the sort of tableau staging we find in Europe and the US at the same period. As with those films, Goro Masamune used lateral staging and some striking depth effects, as well as long takes: I counted 58 shots and 24 intertitles across its 58 minutes.

With 356 shots and 25 intertitles, Roben-sugi exemplified a more cutting-based approach to cinematic storytelling. Scenes were broken down into many shots, often with a great variety of setups; the 180-degree system is in force; and many expressive effects were based on intercut close-ups. In the lengthy final scene, Roben, a temple bishop, discovers his long-lost mother and she prostrates herself before him. The action is played out in high-angle shots of the mother and low-angle shots of Roben. You couldn’t ask for better proof that filmmakers around the world were adopting the US continuity approach than this 1922 film.

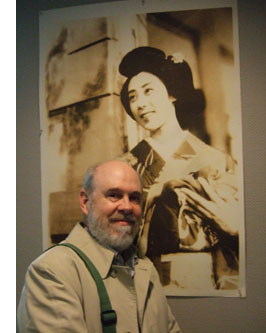

These two movies were powerful treats, and the day was embellished with a visit behind the scenes to the Film Center’s staff area, where I got Yuri to shoot me with one of my favorites, Yamada Isuzu.

These two movies were powerful treats, and the day was embellished with a visit behind the scenes to the Film Center’s staff area, where I got Yuri to shoot me with one of my favorites, Yamada Isuzu.

Earlier in the week, with Kyoko Hirano, I’d visited the Film Center to catch an item in its massive Makino Masahiro retrospective. Makino, son of Japan’s pioneering director Makino Shozo, directed films from the late 1920s to the early 1970s. For his centenary, the Center has mounted 100 programs of his work. No, that’s not a typo. The screenings include 110 titles directed or produced by Makino—and of course several others are lost. Japanese filmmakers are nothing if not prolific.

The film that Kyoko and I saw was Japanese Gangster Story 6: Sake Cup of the White Sword (1967), starring Takakura Ken. The plot consisted of intrigues crisscrossing rival gangs during the 1920s, capped by two bloody fights at the end. Ken doesn’t say much, but the camera loves him; early in the film he seemed to me to get the biggest close-ups. In the finale, of course he sacrifices himself for his gang boss. Is any genre cinema more standardized than the 1960s-1970s yakuza yarn? After a lunch of the Asakusa version of big Hiroshima-style omelettes, Makino’s buoyant retake on the classic tropes was a filling dessert.

The people

The third factor that has made this trip so pleasant has been the people. Hanging out with Yuri was great fun, and as luck would have it, Wisconsin film guy Michael Pogorzelski was visiting Tokyo at the same time. Mike is the archivist for the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, and he restores classic films for the AMPAS collection. (It isn’t all Hollywood, either: the archive is handling Satayajit Ray and Stan Brakhage.) Darkness and rain turned our trip through Shibuya into a scene out of Blade Runner.

Then there was Komatsu Hiroshi, who invited me to the symposium. Hiroshi is one of Japan’s top film historians, a man tirelessly committed to finding Japanese films and explaining their significance. He has made his appearance on this blog before. There was also Fujiwara Toshi, an exuberant young filmmaker I first met in Kyoto about ten years ago. Toshi has directed docs about Amos Gitai and other filmmakers, and his latest fiction film, We Can’t Go Home Again, played at the Berlin festival.

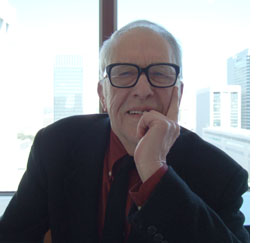

I’ve mentioned Kyoko Hirano, another former student and a best-selling author. Then there was my lunch with Donald Richie, hearty at 82 and planning more books, film screenings, and festival trips. His classic, The Inland Sea, is now being translated into Romanian. He gave me a copy of his newest, A Tractate on Japanese Aesthetics and I reciprocated with a copy of Poetics of Cinema. Donald’s book is as delicate and sharp as a Basho lyric; beside it, my book looks like an andiron.

I’ve mentioned Kyoko Hirano, another former student and a best-selling author. Then there was my lunch with Donald Richie, hearty at 82 and planning more books, film screenings, and festival trips. His classic, The Inland Sea, is now being translated into Romanian. He gave me a copy of his newest, A Tractate on Japanese Aesthetics and I reciprocated with a copy of Poetics of Cinema. Donald’s book is as delicate and sharp as a Basho lyric; beside it, my book looks like an andiron.

At the symposium I learned a great deal from Prof. Takemoto Mikio, director of the Tsubouchi Memorial Theatre Museum at Waseda University, and the vice-director Prof. Akiba Hirokazu; Prof. Takeda Kiyoshi, who studied with Christian Metz; Prof. Nagata Yasushi of Theatre Studies; and many others who contributed talks and comments.

Finally, one more person, the one who spurred me to study Japanese cinema.

Ozu Yasujiro‘s gravesite is in Kita-Kamakura, about an hour southwest of Tokyo by train. In the summer of 1988, Kristin and I were led there by Donald, and so I was due for another pilgrimage. The day was cool and sunny, perfect for a brisk walk through the grounds of Engaku-Ji Temple.

At the end of my trip was the gravestone, which famously bears a single character: Mu, or nothing. Twenty years ago, two beer cans sat reverently on the stone, but today there was an opened bottle of sake. A cigarette lighter was tucked into a hole in the surrounding stone fence. Ozu, fierce smoker and professional drinker, was in his element.

On the platform and then on the train, I let my eyes drift among the schoolkids and the teenyboppers and the salarimen and the grave elders with hygiene masks. I began to imagine how Ozu, the poet of the transience of city life and the comic poignancy of human ties, would turn us all into cinema. He might put the camera over there, squatting on the floor of the traincar. That boy with the backpack might give a sassy reply to his father. Those two stylish office ladies sharing an iPod while a middle-aged man snores beside them–surely that’s a setup for a gag. Playing with the possibilities, one gaijin felt a pang of rapture at the blending of life and art.

What happens between shots happens between your ears

DB here:

In Number, Please? (1920) Harold Lloyd plays a lovesick boy who’s been jilted by his girl. Moping at an amusement park, he sees her arrive with a new beau.

He shifts to another spot to watch them. When she notices him, she scorns him, and he reacts.

She and the escort stroll past, then she turns and cuddles up to him, making sure Harold notices.

Her flirting precipitates the rest of the action in this very funny short.

In this scene from Number, Please? Harold and the couple aren’t shown in the same frame. The action is built entirely out of singles of Harold and two-shots of the couple, with an especially emphasized close-up of the girl’s snooty reaction. The sequence is rapidly paced and carefully matched in angle; note the shift in eyelines as the girl and her beau walk a little way and then she looks back at Harold.

This approach to building a scene was consolidated in American studio cinema in the late 1910s, as we noted recently, and it soon spread around the world. One of the places it caught on most fervently was Soviet Russia.

Kuleshov glories in the gaps

The great director and theorist Lev Kuleshov always claimed that he and his associates learned the power of editing from American cinema. Russian films were slowly paced, consisting of long tableaus occasionally broken by an inserted closer view of an actor. (For examples, see my Bauer blog entry from the summer.) Kuleshov noted that the Hollywood films brought into Russia grabbed audiences’ interest more intently, and Kuleshov attributed this effect to the fact that the Americans exploited editing more fully, creating the scene out of many shots.

Kuleshov’s example was the formulaic scene of a man sitting at his desk and deciding to commit suicide. The Russians, Kuleshov claimed, would handle this all in one distant framing, with the result that the key actions were just part of the overall view. By contrast, Americans would shoot the scene in a series of close-ups: the man’s face, his hand taking a pistol out of a desk drawer, his finger tightening on the trigger, and so on. This gave the scene a powerful concreteness, and was cheaper to film besides (no need to have a full set).

But most American filmmakers didn’t create the scene wholly out of close-ups. Typically there would be an establishing shot before the action was broken down into detail shots. The process has come to be called analytical editing. (We discuss it in Chapter 6 of Film Art.) As the label implies, the cutting analyzes an orienting view into its important details.

Less commonly, as in our Number, Please? example, American directors could create a scene entirely out of separate areas of space, without ever showing a master framing. This technique, usually called constructive editing, remains common today as well, especially in action scenes.

While praising analytical editing, Kuleshov was particularly taken with constructive editing, because that shows that cinema can call on the spectator’s tacit understanding to assemble the separate shots. Kuleshov realized that we will build a sense of the scene’s space and action out of separate shots without need for the comprehensive view supplied by an establishing shot.

What the Americans developed, the Soviets thought seriously about. Around 1921, Kuleshov and his students mounted some experiments, several of which he discusses in his books and essays. He probably didn’t need to experiment; the American films were full of examples. Indeed, the Number Please? passage is more intricate than any experiment Kuleshov seems to have mounted. But he had a bit of the engineer about him, and he sought to break the technique into its simplest components.

For one thing, constructive editing offered production efficiencies. You could film two actors separately, at different times, and then cut them together. Further, Kuleshov saw that editing could abolish real-world constraints. It created events that existed only on the screen, with an assist from the viewer’s mind.

This is perhaps best seen in his experiment involving an “artificial person.” Evidently it wasn’t a case of constructive editing, because it seems to have begun with an establishing shot. The first shot shows a girl sitting at her vanity table putting on makeup and slippers. A series of close-ups of lips, hands, legs, and the like were derived from different women, and they were edited together to create the impression of a single woman. (Something of this effect survives in the idea of a body double in contemporary films and TV commercials.) But the point is that the woman on screen, made out of different parts, doesn’t exist in the real world.

The same possibility could apply to geography, if we delete the establishing shot. As Kuleshov describes his experiment, we initially get a shot of a woman walking along a Moscow street. She stops and waves, looking offscreen. Cut to a man on a street that is in actuality two miles away. He smiles at her and they meet in yet a third location, shaking hands. Then together they look offscreen; cut to the Capitol in Washington DC. Kuleshov saw the potential for imaginary geography as both a useful production procedure and a demonstration that editing could create a purely cinematic space, one not beholden to reality.

Kuleshov’s most famous experiment, the one he identified with the “Kuleshov effect” proper, involves a stock shot of the actor Ivan Mosjoukin, taken from an existing film. In his writing he’s rather vague and laconic about the results.

I alternated the same shot of Mosjoukin with various other shots (a plate of soup, a girl, a child’s coffin), and these shots acquired a different meaning. The discovery stunned me—so convinced was I of the enormous power of montage. (1)

Kuleshov’s pupil the great director V. I. Pudovkin offers a different description of the shots: a plate of soup, a dead woman in a coffin, a little girl playing with a teddy bear. He also goes farther in reporting how the audience responded. People read emotions into the neutral expression on Mosjoukin’s face.

The audience raved about the actor’s refined acting. They pointed out his weighted pensiveness over the forgotten soup. They were touched by the profound sorrow in his eyes as he looked upon the dead woman, and admired the light, happy smile with which he feasted his eyes upon the girl at play. But we knew that in all three cases the face was exactly the same. (2)

Now it isn’t only geography or a human body that has been created by editing; it’s an emotion.

These experiments have been poorly documented, and only a couple have survived. One consists of fragments of the imaginary geography exercise. Here is Alexandra Khokhlova waving, but we don’t have the answering shot of the male actor responding. The two meet at the foot of a statue.

After the two shake hands, they look up and out of the frame, but unfortunately we lack the shot of the Capitol.

Kristin and other scholars have written more about these surviving fragments, and their essays are published along with Kuleshov’s proposal for funding the experiments and his wife Khokhlova’s memoir of filming them. (3)

It’s worth taking these prototypes of constructive editing apart a little bit. Clearly, there are several cues that prompt us to see the shots as continuous.

One cue is a common background, or at least a consistent one. Kuleshov thought that sometimes a neutral black background worked best, especially for close shots, as you can see with the handshake shot. Another cue is roughly consistent lighting from shot to shot. Yet another is the presumption of temporal continuity; no moments seem to be omitted in the cut from shot A to shot B. It never occurs to us to consider that Kuleshov’s man is looking at something hours or days before the soup is laid on the table in the second shot.

One of the most important cues goes unmentioned by Kuleshov: the very act of looking. Like most commentators, he seems to take it for granted. Yet it’s crucial in prompting us to imagine an overall space in which the actions take place. Knowing the real world as we do, we can infer that if you’re close enough to watch someone, both people are probably in a shared space, such as the arcade strip in the amusement park in Number, Please?

Another cue is facial expression. In his soup/girl/coffin sequence, Kuleshov supposedly picked a shot of Mosjoukin that doesn’t have a clearly identifiable expression. If Mosjoukin was smiling in his interpolated shot, he would presumably seem not grieving but wicked. Normally, though, performers seen in the single shot are expected to express the appropriate emotion more fully, in order to specify what we take the characters’ mental states to be. Our sequence from Number, Please? makes sure we understand the drama by giving the actors unambiguous expressions.

Finally, in the Kuleshov prototypes each shot should be simple. Its action can be stated in a brief sentence. A woman waves. A man responds. A man looks. A plate of soup sits on a table. Even in Number, Please? we can summarize each shot: Harold looks off. His former girlfriend disdains him. That’s to say that the shots are composed to present only one, quickly grasped point of interest.

Filmmakers don’t need to tease apart all these cues; they use them intuitively. Soon after Number, Please?, Hollywood filmmakers were creating amazing passages of eyeline-match editing—the most virtuoso being probably the racetrack sequence in Lubitsch’s Lady Windermere’s Fan (1926). Within a few years of Kuleshov’s experiments, Soviet filmmakers were creating their own masterworks, like Battleship Potemkin (1925) and Kuleshov’s By the Law (1926). Benefiting from a very compressed learning curve, filmmakers took constructive editing to new heights.

Constructive editing, dissolved relationships

Sometimes constructive editing is used to save a scene when production goes astray. When Doug Liman reshot the climax of The Bourne Identity, Julia Stiles couldn’t be on set, so singles of her taken from the first version were wedged in among the retakes, to create the impression that she was watching Jason confront his controller. More positively, a carefully calibrated constructive editing is central to a sequence I analyzed a while back in In the City of Sylvia. For over 100 shots, the spatial relations are built up without an overall establishing shot. (4)

Constructive editing can be used systematically throughout a film. A good example is Alan J. Pakula’s thriller Presumed Innocent (1990). Spoilers coming up!

Harrison Ford plays Rusty Sabitch, a prosecutor in the District Attorney’s office who becomes infatuated with a new woman on the staff. He has a brief affair with her, but after she’s broken it off she’s found brutally murdered. He has to investigate the crime without involving himself, but eventually he becomes the prime suspect.

At the start of the film before Rusty learns of the murder, Rusty and his wife Barbara are shown at breakfast, and establishing shots bring them together.

At the office Rusty learns of Carolyn’s death, and after he comes home, the conversation between Rusty and Barbara is treated without an establishing shot. Barbara knows about the past affair, and Rusty is wracked by guilt and shame. The cutting seems to reflect the fact that Carolyn’s death has revived the pain in their marriage.

In a series of flashbacks, Rusty relives his affair with Carolyn. Pakula treats their early encounters by means of constructive editing. The common-background cue is especially helpful in this scene in a kindergarten.

Only after Carolyn and Rusty cooperate and win a child-abuse case does the cutting’s rationale become clear. Pakula has saved the traditional two-shot framing for their moment of passion, as they make furious love in the office.

But soon their affair wanes and Rusty is reduced to watching Carolyn from across the street in point-of-view shots.

After the flashbacks end, Rusty is investigated and eventually charged with Carolyn’s murder. In these scenes Pakula often situates Rusty and Barbara in the same frame, as if the threat to him has healed the breach between them.

Yet in the film’s climax—and here is the big spoiler—they are pulled apart again. The last scene is a sustained monologue by Barbara. As Rusty listens, across twenty-six shots the two are never shown in an establishing shot.

Contrary to the standard Hollywood ending, in which the loving couple embrace in reunion, here they are left divided.

Pakula’s use of constructive editing has effectively traced two arcs: the growth and dissolution of Rusty’s affair, and the reuniting and dissolution of his marriage. In such ways, what might seem a purely local effect, confined to a handful of shots, can create stylistic patterning across a film. The judicious use of constructive editing matches the dramatic development.

Godard of the gaps

Robert Bresson has made more varied and complex uses of constructive editing across a film, as I tried to show in Narration in the Fiction Film and in an Artforum essay. (5) A more radical approach, somewhat in the purely Kuleshovian spirit, can be seen in Godard’s films since the late 1970s. In presenting a scene, Godard often omits an establishing shot, so constructive editing takes over. But he makes the technique quite abrasive and ambivalent.

In watching films like Number, Please? and Presumed Innocent, we fill in the gaps between shots with ease. Godard, however, makes his images and sounds more fragmentary by equivocating about the Kuleshovian cues. The background elements and lighting don’t match entirely; time seems to be skipped over; glances and facial expressions are ambivalent. Adding to these factors, lines of dialogue slip in from offscreen. Godard does present a dramatic scene taking place, but he also creates a sense that images and sounds have been pried loose from their place in an ongoing action, floating somewhat free and functioning as objects of contemplation for their own sake. The cues that Lloyd insists on and that Kuleshov plays with are ones that Godard suppresses or makes ambiguous.

I’ve mentioned this tendency in a recent entry, but to elaborate a little, consider the science lecture in Hail Mary (Je vous salue Marie, 1985). A professor who has emigrated from an Eastern bloc country is explaining his theory that life on earth began and evolved because it was directed by extraterrestrials. No establishing shot of the classroom shows us where he, Eva, and two male students are located, so we have to construct a rough sense of their positions on the basis of a few cues. As Eva, perched on a windowsill, toys with a Rubik’s cube, we hear the professor’s lecture begin to speculate on whether life could have evolved spontaneously. His remarks about sunlight coincide with a burst of sun on her face.

After the Biblical title, “In those days,” we get a series of shots that allow us to apply our mental schema of a classroom lecture: attentive students looking off, a professor at the blackboard.

Lacking an establishing shot, we can’t specify how many people are in the class, nor indeed where Eva and her classmate are sitting—since the professor looks off in several directions during his talk.

At the end of his talk he remarks, still scanning the room, that we can presume that life exists in space. “We come from there.” At that point Godard cuts to the head of another student, seen from behind. The sproingy haircut is a little explosion of yellow, and it’s accompanied by a burst of choral music. And as the shot goes on, we start to notice that the professor is pacing in the background, out of focus.

The student, whom we’ll learn is named Pascal, asks a question (at least the slight head movement suggests that it comes from him), and the professor replies. Pascal scratches his head as the professor continues, still out of focus. If I had to choose one shot that condenses Godard’s strategy of suppression in this sequence, this shot would be my candidate.

At the end of the shot, the professor asks Eva to stand behind Pascal. Cut 180 degrees and somewhat farther back to Pascal, now seen from the front. The professor’s hand brings the Rubik’s cube into the shot and Eva comes up behind Pascal as the professor passes.

Later she and the prof will become lovers, but Godard lets them meet first as simply two torsos intersecting behind Pascal. The purpose is a demonstration that a “blind” agent can be steered toward a goal through simple yes/no commands. This models the professor’s theory that an alien intelligence could have guided evolution.

Pascal will twist the facets of the cube under Eva’s hints. Godard makes this a tactile, even erotic exchange, with the close-up of her by his ear and Eva saying, “Yes,” more urgently as Pascal’s hands arrive at a solution, in the close-up surmounting this blog entry.

The next two shots of the sequence center on the prof, who has exited frame right from the “three-shot.” Now he’s at the window, recalling the initial shot of Eva; but unlike her he’s little more than a silhouette. As crashing organ music is heard, he seems to be watching the experiment from afar. The second shot, an axial cut-in, coincides with the offscreen voice of a male student: “Were you exiled for these ideas?”

“These ideas, and others,” the prof replies. He says he’ll see the class on Monday, evoking the idea that he’s dismissing the offscreen students, and he turns his head slightly, though we can’t be sure they’re on his right. This shot will be held for some time as students quiz him more about his theory, and Eva asks him if he’d like to come over for a drink some evening. But we don’t see her say it. Godard cuts to a shot of Eva at the window, bathed in sunlight, opening and shutting her eyes as she slightly lifts and lowers her head.

As we see her, we hear the rustling of people leaving (so the class was evidently larger than three). And we hear him reply to her invitation, “That’s another story [scénario].” Are Eva and the prof looking at each other? We’re inclined to say yes, but her closed eyes and tilting head suggests someone lost in contemplation rather than engaged in conversation. Here the classic facial-expression cue is made indeterminate. We have no way of knowing if the prof’s line comes from offscreen, or is displaced from another point in time; maybe he has left the room. Such displaced diegetic sound occurs elsewhere in the film.

We don’t have to decide; our indecision is the point. By pruning away the most reliable cues, Godard wins both ways. We’re kept somewhat oriented to an intelligible action: a prof sets forth his far-fetched theory of human origins and a woman in his class invites him for coffee. This side of the balance allows us to feel that a story, however sketchy, is moving forward.

But the moment-by-moment texture of the scene allows the individual shots, gestures, and sounds to drift somewhat free. Each image takes on a more intrinsic weight, and the juxtaposition of picture and sound acquires a resonance that we usually call poetic. A shot of Eva in the sun playing with the Rubik’s cube, unanchored in time (during class? before class started?), invites us to apply metaphors, especially once we learn her name. Pascal’s thorny hair suggests not only extraterrestrials but the explosion of a nova. The silhouetted prof, detached from the mechanism he has set in motion, hints at an unknown deity watching the game play out according to his rules. Why do Godard films spawn long essays built out of erudite associations? Because the narrative progression relaxes and we can weave our own connotations out of what we see and hear.

If you don’t want to go down the expanding-association route, there’s another one open. When individual moments no longer accumulate ordinary dramatic pressure, we can savor the fugitive pleasures of the separate shots (light on face, lips by ear) and the patterns they form: flipover cuts, yellow hair and yellow facets, bookended shots of Eva at the window.

Those patterns, it should be clear, depend on our sensing a bump at every shot change, looking for a way to skip across the gap that Godard creates. The same belief that meaning and effect are born of gaps impelled Kuleshov too, and perhaps even Lloyd. If we pay attention to those gaps we can feel minds—both the filmmaker’s and ours—at work in them.

(1) Lev Kuleshov, “’50’: In Maloi Gznezdinokovsky Lane,” Kuleshov on Film, trans. and ed, Ronald Levaco (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1974), 200.

(2) V. I. Pudovkin, “The Naturschchik instead of the Actor,” Selected Essays, ed. and trans. Richard Taylor (Oxford: Seagull, 2006), 160.

(3) See Kristin Thompson, Yuri Tsivian, and Ekaterina Khokhlova, “The Rediscovery of a Kuleshov Experiment: A Dossier,” Film History 8, 3 (1996), 357-367.

(4) The sequence does begin with a long shot of the café, but it is so distant, crowded, and brief that it can’t really be said to establish the spatial relationships among the several characters we see.

(5) “Sounds of Silence,” Artforum International (April 2000): 123.

Happy birthday, classical cinema!, or The ten best films of … 1917

Wild and Woolly (1917).

KT:

Periodization is a tricky task for historians, and there are a lot of disputes about how to divide up the 110-plus years of the cinema’s existence. We all have to deal with it, though, if we want to organize our studies of the past into meaningful units. How to do that?

Do we divide the periods of film history according to major historical events? World War I had a huge impact on the film industry, to be sure, and we might say that one significant period for cinema is 1914-1918. Yet 1919 didn’t mark the start of a new period. The major European post-war film movements didn’t start then. French Impressionism arguably began in 1918, German Expressionism in 1920, and Soviet Montage in 1924 or 1925.

Carving up film history partly depends on what questions the historian is asking. If you’re studying wartime propaganda, 1914 and 1918 would provide significant beginning and end points. If you want to trace the development of significant film styles, it doesn’t seem very useful.

While historians have difficulties agreeing on periodization, just about everyone concurs that there were two amazing years during the 1910s when filmmaking practice somehow coalesced and produced a burst of creativity: 1913 and 1917.

One can point to stylistically significant films made before 1913. Somehow, though, that year seemed to be when filmmakers in several countries simultaneously seized upon what they had already learned of technique and pushed their knowledge to higher levels of expressivity. “Le Gionate del Cinema Muto” (“The Days of Silent Cinema”), the major annual festival, devoted its 1993 event to “The Year 1913.” The program included The Student of Prague (Stellan Rye), Suspense (Phillips Smalley and Lois Weber), Atlantis (August Blom), Raja Harischandra (D. G. Phalke), Juve contre Fantomas (Louis Feuillade), Quo Vadis? (Enrico Guazzoni), Ingeborg Holm (Victor Sjöström), The Mothering Heart (D. W. Griffith), Ma l’amor mio non muore! (Mario Caserini), L’enfant de Paris (Léonce Perret), and Twilight of a Woman’s Soul (Yevgenii Bauer). .

1917, by contrast, was primarily an American landmark. As 2007 closes, we thought it appropriate to wish happy birthday to the most powerful and pervasive approach to filmic storytelling the world has yet seen. That would be classical continuity cinema, synthesized in what was coming to be known as Hollywood.

DB:

In The Classical Hollywood Cinema and work we’ve done since, we’ve maintained that 1917 is the year in which we can see the consolidation of Hollywood’s characteristic approach to visual storytelling. This idea was first floated by Barry Salt, and our research confirms his claim. Over the ninety years since 1917 the style has changed, but its basic premises have remained in force.

Before classical continuity emerged, the dominant approach to shooting a scene might be called the tableau technique. Action was played out in a full shot, using staging to vary the composition and express dramatic relationships. Elsewhere on this site I’ve mentioned two major exponents of this approach, Feuillade and Bauer.

When there was cutting within the tableau setup, it usually consisted of inserted close-ups of important details, especially printed matter, like a letter or telegram. Occasionally the close-up of an actor could be inserted, usually filmed from the same angle as the master shot. The tableau approach was more prominent in scenes taking place in interiors; filmmakers were freer about cutting action occurring outdoors.

We shouldn’t think of the tableau as purely “theatrical.” For one thing, the master shot was typically closer and more tightly organized than a scene on the stage would be. Moreover, for reasons I discuss in Figures Traced in Light, the playing space of the cinematic frame is quite different from the playing area of the proscenium theatre. The filmmaker can manipulate composition, depth, and blocking in ways not available on the stage.

The tableau approach was the default premise of US filmmaking through the early 1910s. You can see it at work, for example, in this shot from At the Eleventh Hour (W. V. Ranous, 1912). Mr. and Mrs. Richards are in the study of Mr. Daley. After Richards has refused to sell his railroad bonds, Daley’s wife shows off her diamond necklace to the visitors.

At first the two couples are separated in depth, the men in the foreground and the women further back. In the first frame below, a new necklace has just been delivered, and a servant gives it to Mrs. Daley. Only the servant’s hand is visible, as she is blocked by Richards in the foreground. In the second frame, the two women come forward. Mrs. Daley holds the necklace up and Mrs. Richards oohs and ahhs over it, while her husband glances at Daley as if to wonder how he could afford it.

Instead of breaking the scene into closer views, spreading the characters’ reactions across separate shots, Ranous squeezes all of their actions and expressions into a tight space across the center of the shot. Nor does he provide a close-up of the necklace, which will be important in the plot. (1) We might be inclined to say that this is a “theatrical” shot, but on a stage the actions in depth (the women chatting, the servant handing over the parcel) wouldn’t be visible to everyone in the auditorium. Likewise, on a stage the packed faces in the later phase of the scene wouldn’t be visible to people sitting on the sides.

As films became longer, American filmmakers were starting to organize their plots around characters with firm goals. Conflicting goals would set the characters in opposition to one another, and at a climax, usually under the pressure of a deadline, the protagonist achieves or fails to achieve the goals. The plot also tends to build up two lines of action, at least one involving romance.

There’s no reason this conception of narrative could not have been applied to the tableau style; in many cases it was. But hand in hand with the rise of goal-driven plotting came a new approach to filming. Sporadically before 1917, filmmakers in many countries were exploring ways to build scene out of many shots. (If you want to know the process in the US in more detail, check out Early American Cinema in Transition by Charlie Keil.) By 1917, American filmmakers had synthesized these tactics into an overall strategy, a system for staging, shooting, and cutting dramatic action.

We know the result as the 180-degree system. This encourages the filmmaker to break a scene into several shots, taken from different distances and angles, all from one side of an imaginary line slicing through the space. Around 1917, this stylistic approach comes to dominate US feature films, in the sense that every film made will tend to display all the devices at least once. The system remains in place to this day, and it came to form the basis of popular cinemas across the world. (2)

Once you break a scene into several shots, some characters won’t be onscreen all the time. So you need to be clear about where offscreen characters are; you need to supply cues that allow the audience to infer their positions. So 1910s filmmakers developed various ways of “matching” shots.

Shots can be connected by character looks, thanks to the eyeline match. Here’s an instance from Victor Schertzinger’s The Clodhopper (1917). First there is a master shot of the mother and son in their farm kitchen.

This is followed by a separate shot of each one. Their bodily positions and eyelines remind us that the other is just out of frame.

Although over-the-shoulder shooting hadn’t yet been developed, a conception of the reverse angle is at work here too. Schertzinger’s camera doesn’t shoot the actors perpendicularly, but takes up an angle on one that becomes an echo of that filming the other. Here’s another example of reverse angles from The Devil’s Bait (1917, director Harry Harvey).

The camera doesn’t just enlarge a portion of the space, as in the inserted shot in a tableau scene. The angle of view has changed significantly.

Changes of angle within the scene have become fairly complex by 1917. This strategy is apparent when the action takes place in a theatre, a courtroom, a church, or some other large-scale gathering point. The camera position changes often in this scene from The Girl without a Soul (director John Collins).

The concept of matching extends to physical movement too, through the match on action. This device allows the director to highlight a new bit of space while preserving the continuity of time. In Roscoe Arbuckle’s The Butcher Boy, the cut-in to Fatty (with a change of angle) also matches his gesture of putting his hands on his hips.

Interestingly, even this early, directors have learned to leave a little bit of overlapping action across the cut. If you move frame by frame, you’ll see that Fatty’s gesture is repeated a bit at the start of the second shot.

When a character leaves one frame, he or she can come into another space, from the side of the frame consistent with the 180-degree premise. This is matching screen direction. A cut of this sort lets us know that the next portion of the locale that we see is more or less adjacent to the previous one. In Field of Honor (director Allen Holuban), Wade crosses to Laura, who’s waiting in a carriage. A few years earlier, the director might have presented his greeting in a single deep-space long shot. Instead, Wade exits one shot and enters the next.

Again, the reverse-angle principle governs the camera setups. Wade moves along a diagonal toward the camera and away from it.

More generally, Field of Honor exhibits a polished handling of the new style: lots of reverse shots and eyeline matches, fades that bracket flashbacks, binocular points of view, rack-focus shots, and rapid cutting (there’s even a ten-frame shot). The point is not to claim Field of Honor as an undiscovered masterpiece but rather to indicate that by 1917 a director could handle all the devices with assurance.

Match-cutting devices had been used occasionally before 1917, but by that year filmmmakers melded them into a consistent and somewhat redundant method of guiding the audience through each scene.

The continuity system not only creates a basic clarity about characters’ positions. It can as well generate a speed and accentuation not easily achieved within a single shot. For example, Wade’s frame exit and entrance above is cut so as to skip over moments that he consumes crossing the driveway. Continuity editing enhances the rapid pace of US films, a quality immediately noted by foreign observers in the 1910s and 1920s.

Two of the best films of 1917 exploit the dynamism of continuity cutting. The Doug Fairbanks comedy western, Wild and Woolly, seems designed to prove that American films could proceed at breakneck speed. In climactic scenes, we’re caught in a whirlwind of fast cutting, with the pace set by the hyperactive protagonist, a financier’s son who longs to prove himself as a cowboy.

John Ford’s Straight Shooting proceeds at a more measured pace, but in its final shootout we see a prototype of all the main-street gundowns that will define the Western. Ford provides alternating shots of the cowboys advancing toward each other, framing each man more tightly and concluding with suffocating close-ups of each man’s face, highlighting the eyes.

Sergio Leone, eat your heart out.

Propelled by goal-driven characters and a linear arc of action, films like Wild and Woolly and Straight Shooting are completely understandable and enjoyable today. (But when will we have them on DVD?) Their stories are engrossing and their performances are engaging, but just as important their storytelling technique has become second nature to us. The narrative strategies that coalesced in 1917 remain fundamental to mainstream cinema.(2)

The Mystery of the Belgian Print

KT:

For decades now we have been visiting Brussels and working at the Cinémathèque Royale de Belgique/Koninklijk Belgisch Filmarchief. Sometimes I feel that we would know half as much about the cinema were it not for the unfailing hospitality we have been shown, initially by the great archivist Jacques Ledoux and now by his successor Gabrielle Claes. Our indebtedness to this institution and its staff are reflected in David’s named professorship; he is the Jacques Ledoux Professor of Film Studies. We dedicated our Film History: An Introduction, to Gabrielle.

We do whatever favors we can in return for such wonderful help. David lectures regularly at the biannual summer school run by the Flemish Service for Film Culture in partnership with the Royal Film Archive. (David wrote about the 2007 event in an earlier entry.) I try to identify silent films. I am not always successful, but I suppose over the years I have been able to put names to thirty-some mystery prints.

Silent films are more likely to be unidentified than sound ones because it was standard practice to splice in intertitles in the local language. Sometimes too the film’s title was changed. The film’s actors may be forgotten today, or the print may be incomplete, lacking the opening title and credits. Sometimes even the country of origin is unknown.

Back in the early 1990s I was asked to identify a five-reel nitrate print with the title Père et fils. It was an original distribution copy from the silent era. The information on the archival record card listed some possible identifications: Father and Son, a 1913 Vitagraph film or Father and Son, produced by Mica in 1915. It was tentatively thought to be American.

As I watched the film, it quickly became apparent that it was indeed American. It centered on the rivalry between a small dime store owned by the heroine’s father and a modern dime store being built in the same town. The hero is charged with the mission of driving the older store out of business.

So we had our typical goal-driven plot. The style was what David has described as typical of 1917, so that was my tentative dating. I felt almost certain that the reels I was watching were not from a 1913 or 1915 movie. The film was a fairly modest item, done on a relatively low budget and not starring any actors that would be familiar to most modern viewers. I had seen the actor playing the hero before, however, and I thought he might be Herbert Rawlinson. By the time I finished the film, those were my clues: a medium-budget American film of c. 1917 concerning dime stores and perhaps starring Rawlinson.

My task turned out to be fairly simple. A little research after we returned home confirmed the Rawlinson guess. In preparing the write The Classical Hollywood Cinema, I had seen him in The Coming of Columbus (a 1912 Selig film) and in Damon and Pythias (Universal, 1914).

My next step was to consult the monumental, indispensible reference book, The American Film Institute Catalog. This multi-volume set, many years in the making, was originally published as books. It is now online, but available only to AFI members or through libraries. The catalogues were published by decade—thus obviating the problem of periodization. Each decade gets two volumes, one of entries on all the films, listed in alphabetical order. Credits, production companies, release dates, plot synopses, and other information are included. A second volume indexes the films by chronology, personal names, corporate names, subject, genre, and geography (i.e., where the films were shot).

Until now I had found little use for the subject index, but now it came to my aid. I turned to the Ds to see if there was an entry for dime stores. The AFI indexers were thorough, and sure enough, there was one entry: Like Wildfire. A check of the personal names index under Rawlinson, Herbert revealed that he had acted in a film called Like Wildfire, made in 1917 by Universal. Once I had the title, I checked its catalog entry and found that its plot description matched the film I had seen. Case closed.

Admittedly, in this instance the date wasn’t a crucial clue. Still, determining a film’s year of release can narrow down the possibilities. Thanks as well to the development of classical cutting, a close view of an actor helps in identifying him.

The Best of 1917

DB:

This is the season when everybody makes a list of best pictures. We have stopped playing that game. For one thing, we haven’t seen all the films that deserve to be included. For another, the excellence of a film often dawns gradually, after you’ve had years to reflect on it. And critical tastes are as shifting as the sirocco. Never forget that in 1965 the Cannes palme d’or was won by The Knack . . . and How to Get It.

Still, enough time has elapsed to make us feel confident of this, our list of the best (surviving) films of 1917, both US and “foreign-language.” Titles are in alphabetical order.

The Clown (Denmark, A. W. Sandberg)

Easy Street (U.S., Charles Chaplin)

The Girl from Stormycroft (Sweden, Victor Sjöström)

The Immigrant (U.S., Charles Chaplin)

Judex (France, Louis Feuillade)

The Mysterious Night of the 25th (Sweden, Georg af Klercker)

The Narrow Trail (U.S., Lambert Hillyer)

The Revolutionary (Russia, Yevgenii Bauer)

Romance of the Redwoods (U.S., Cecil B. De Mille)

Terje Vigen (Sweden, Victor Sjöström)

Straight Shooting (US, John Ford)

Thomas Graal’s Best Film (Sweden, Mauritz Stiller)

Wild and Woolly (US, John Emerson)

Next year, maybe we’ll draw up our list for 1918.

(1) For more on this scene and the film as a whole, see Kristin Thompson, “Narration Early in the Transition to Classical Filmmaking: Three Vitagraph Shorts,” Film History 9, 4 (1997), 410-434.

(2) Beyond The Classical Hollywood Cinema, see Kristin’s Herr Lubitsch Goes to Hollywood and Storytelling in the New Hollywood. I’ve talked about these issues in On the History of Film Style, Planet Hong Kong, Figures Traced in Light, The Way Hollywood Tells It, and essays included in Poetics of Cinema. The basics of classical continuity are presented in Chapter 6 of Film Art: An Introduction, and we trace some historical implications of it in Film History: An Introduction.