Archive for the 'Film technique: Editing' Category

Legacies

DB here:

By now James Mangold’s 3:10 to Yuma has had its critics’ screenings and sneak previews. It’s due to open this weekend. The reviews are already in, and they’re very admiring.

Back in June, I saw an early version as a guest of the filmmaker and I visited a mixing session, which I chronicled in another entry. I was reluctant to write about the film in the sort of detail I like, because I wasn’t seeing the absolutely final version and because it would involve giving away a lot of the plot.

I still won’t offer you an orthodox review of the film, which I look forward to seeing this weekend in its final theatrical form. Instead, I’ll use the film’s release as an occasion to reflect on Mangold’s work, on his approach to filmmaking, and on some general issues about contemporary Hollywood.

An intimidating legacy

It seems to me that one problem facing contemporary American filmmakers is their overwhelming awareness of the legacy of the classic studio era. They suffer from belatedness. In The Way Hollywood Tells It, I argue that this is a relatively recent development, and it offers an important clue to why today’s ambitious US cinema looks and sounds as it does.

In the classic years, there was asymmetrical information among film professionals. Filmmakers outside the US were very aware of Hollywood cinema because of the industry’s global reach. French and German filmmakers could easily watch what American cinema was up to. Soviet filmmakers studied Hollywood imports, as did Japanese directors and screenwriters. Ozu knew the work of Chaplin, Lubitsch, and Lloyd, and he greatly admired John Ford. But US filmmakers were largely ignorant of or indifferent to foreign cinemas. True, a handful of influential films like Variety (1925) and Potemkin (1925) made an impact on Hollywood, but with the coming of sound and World War II, Hollywood filmmakers were cut off from foreign influences almost completely. I doubt that Lubitsch or Ford ever heard of Ozu.

Moreover, US directors didn’t have access to their own tradition. Before television and video, it was very difficult to see old American films anywhere. A few revival houses might play older titles, but even the Museum of Modern Art didn’t afford aspiring film directors a chance to immerse themselves in the Hollywood tradition. Orson Welles was considered unusual when he prepared for Citizen Kane by studying Stagecoach. Did Ford or Curtiz or Minnelli even rewatch their own films?

With no broad or consistent access to their own film heritage, American directors from the 1920s to the 1960s relied on their ingrained craft habits. What they took from others was so thoroughly assimilated, so deep in their bones, that it posed no problems of rivalry or influence. The homage or pastiche was largely unknown. It took a rare director like Preston Sturges to pay somewhat caustic respects to Hollywood’s past by casting Harold Lloyd in Mad Wednesday (1947), which begins with a clip from The Freshman. (So Soderbergh’s use of Poor Cow in The Limey has at least one predecessor.)

Things changed for directors who grew up in the 1950s and 1960s. Studios sold their back libraries to TV, and so from 1954 on, you could see classics in syndication and network broadcast. New Yorkers could steep themselves in classic films on WOR’s Million-Dollar Movie, which sometimes ran the same title five nights in a row. There were also campus film societies and in the major cities a few repertory cinemas. The Scorsese generation grew up feeding at this banquet table of classic cinema.

In the following years, cable television, videocassettes, and eventually DVDs made even more of the American cinema’s heritage easily available. We take it for granted that we can sit down and gorge ourselves on Astaire-Rogers musicals or B-horror movies whenever we want. Granted, significant areas of film history are still terra incognita, and silent cinema, documentary, and the avant-garde are poorly served on home video. Nonetheless, we can explore Hollywood’s genres, styles, periods, and filmmakers’ work more thoroughly than ever before. Since the 1970s, the young American filmmaker faces a new sort of challenge: Now fully aware of a great tradition, how can one keep from being awed and paralyzed by it? How can a filmmaker do something original?

I don’t suggest that filmmakers have decided their course with cold calculation. More likely, their temperaments and circumstances will spontaneously push them in several different directions. Some directors, notably Peckinpah and Altman, tried to criticize the Hollywood tradition. Most tried simply to sustain it, playing by the rules but updating the look and feel to contemporary tastes. This is what we find in today’s romantic comedy, teenage comedy, horror film, action picture, and other programmers.

More ambitious filmmakers have tried to extend and deepen the tradition. The chief example I offer in The Way is Cameron Crowe’s Jerry Maguire, but this strategy also informs The Godfather, American Graffiti, Jaws, and many other movies we value. I also think that new story formats like network narratives and richly-realized story worlds have become creative extensions of the possibilities latent in classical filmmaking.

James Mangold’s career, from Heavy onward, follows this option, though with little fanfare. He avoids knowingness. He doesn’t fill his movies with in-jokes, citations, or homages. Instead, he shows the continuity between one vein of classical cinema and one strength of indie film by concentrating on character development and nuances of performance. In an industry that demands one-liners and catch-phrases sprinkled through a script, Mangold offers the mature appeal of writing grounded in psychological revelation. In a cinema that valorizes the one-sheet and special effects and directorial flourishes, he begins by collaborating with his actors. He is, we might say, following in the steps of Elia Kazan and George Cukor.

Sandy

By his own account, Mangold awakened to these strengths during his formative years at Cal Arts, where he studied with Alexander Mackendrick. Mackendrick directed some of the best British films of the 1940s and 1950s, but today he is best known for Sweet Smell of Success.

Seeing it again, I was struck by the ways that it looks toward today’s independent cinema. It offers a stinging portrait of what we’d now call infotainment, showing how a venal publicist curries favor with a monstrously powerful gossip columnist. It’s not hard to recognize a Broadway version of our own mediascape, in which Larry King, Oprah, and tmz.com anoint celebrities and publicists besiege them for airtime. While at times the dialogue gets a little didactic (Clifford Odets did the screenplay), the plotting is superb. Across a night, a day, and another night, intricate schemes of humiliation and aggression play out in machine-gun talk and dizzying mind games. It’s like a Ben Jonson play updated to Times Square, where greed and malice have swollen to grandiose proportions, and shysters run their spite and bravado on sheer cutthroat adrenalin.

Sweet Smell was shot in Manhattan, and James Wong Howe innovated with his voluptuous location cinematography. “I love this dirty city,” one character says, and Wong Howe makes us love it too, especially at night.

Today major stars use indie projects to break with their official personas, and the same thing happens in Mackendrick’s film. Burt Lancaster, who had played flawed but honorable heroes, portrayed the columnist J. J. Hunsecker with savage relish. “My right hand hasn’t seen my left hand in thirty years,” he remarks. Tony Curtis, who would go on to become a fine light comedian, plays Sidney Falco as a baby-faced predator, what Hunsecker calls “a cookie full of arsenic.” Falco is sunk in petty corruption, ready to trade his girlfriend’s sexual favors for a notice in a hack’s column. Hunsecker and Falco, host and parasite, dominator and instrument, are inherently at odds, then in a breathtaking scene they double-team to break the will of a decent young couple. There are no heroes. Nor, as Mangold points out in his Afterword to the published screenplay, do we find any of that “redemption” that today’s producers demand in order to brighten a bleak story line.

Mackendrick must have been a wonderful teacher. On Film-Making, Paul Cronin’s published collection of his course notes, sketches, and handouts, forms one of our finest records of a director’s conception of his art and craft. Offering a sharp idea on every page, the book should sit on the same shelf with Nizhny’s Lessons with Eisenstein.

Mackendrick must have been a wonderful teacher. On Film-Making, Paul Cronin’s published collection of his course notes, sketches, and handouts, forms one of our finest records of a director’s conception of his art and craft. Offering a sharp idea on every page, the book should sit on the same shelf with Nizhny’s Lessons with Eisenstein.

Mangold became a willing apprentice to Mackendrick. “He taught me more craft than I could articulate, but beyond that, he showed me how hard one had to work to make even a decent film.” (1) Mangold’s afterword to the Sweet Smell screenplay offers a precise dissection of the first twenty minutes. He shows how the script and Mackendrick’s direction prepare us for Hunsecker’s entrance with the utmost economy. Mangold traces out how five of Mackendrick’s dramaturgical rules, such as “A character who is intelligent and dramatically interesting THINKS AHEAD,” are obeyed in the film’s first few minutes. The result is a taut character-driven drama, operating securely within Hollywood construction while opening up a sewer in a very un-Hollywood way. Surely Sandy Mackendrick’s boldness helped Mangold find his own way among the choices available to his generation.

Movies for grownups

Mangold has often mentioned his love for classic Westerns; on the DVD commentary for Cop Land he admits that he wanted it to blend the western with the modern crime film. But why Delmer Daves’ 3:10 to Yuma?

The Searchers, Rio Bravo, and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance were objects of veneration for directors of the Bogdanovich/ Scorsese/ Walter Hill generation, while Yuma seemed to be a more run-of-the-mill programmer. To American critics in the grips of the auteur theory, Delmer Daves sat low in the canon, and Glenn Ford and Van Heflin offered little of the star wattage yielded by John Wayne, James Stewart, and Dean Martin. In retrospect, though, I think that you can see what led Mangold to admire the movie.

For one thing, it’s a close-quarters personal drama. It doesn’t try for the mythic resonance of Shane or The Searchers or Liberty Valance, and it doesn’t relax into male camaraderie as Rio Bravo does. The early Yuma simply pits two sharply different men against one another. Ben Wade is a robber and killer who is so self-assured that he can afford to be courteous and gentle on nearly every occasion. Dan Evans is a farmer so beaten down by bad weather, bad luck, and loss of faith in himself that he takes the job of escorting the killer to the train depot.

That dark glower that made Glenn Ford perfect for Gilda and The Big Heat slips easily into the soft-spoken arrogance of Wade. His self-assurance makes it easy for him to play on all of Evans’ doubts and anxieties. In counterpoint, Van Heflin gives us a man wracked by inadequacy and desperation; his flashes of aggression only betray his fears. In the end, his courage is born not of self-confidence but of sheer doggedness and a dose of aggrieved envy. He has taken a job, he needs the money to provide for his family, and, at bottom, it’s not right that a man like Wade should flourish while Evans and his kind scrape by. As in Sweet Smell of Success, the drama is chiefly psychological rather than physical, and the protagonist is far from perfect.

Daves shows the struggle without cinematic flourishes, in staging and shooting as terse as the prose in Elmore Leonard’s original story. Deep-focus images and dynamic compositions maintain psychological pressure, and as ever in Hollywood films, undercurrents are traced in postures and looks, as when Wade in effect takes over Evans’ role as father at the dinner table.

One more factor, a more subliminal one, may have attracted Mangold to Daves’ western. 3:10 to Yuma was released in 1957, about two months after Sweet Smell of Success. Both belong to a broader trend toward self-consciously mature drama in American movies. Faced with dwindling audiences, more filmmakers were taking chances, embracing independent and/or East Coast production, and offering an alternative to teenpix and all-family fare. 1957 is the year of Bachelor Party, Twelve Angry Men, Edge of the City, A Face in the Crowd, The Garment Jungle, A Hatful of Rain, The Joker Is Wild, Mister Cory (also with Tony Curtis), No Down Payment, Pal Joey, Paths of Glory, Peyton Place, Run of the Arrow, The Strange One, The Tarnished Angels, The Three Faces of Eve, Twelve Angry Men, and The Wayward Bus. These films and others featured loose women, heroes who are heels, and “adult themes” like racial prejudice, rape, drug addiction, prostitution, militarism, political corruption, suburban anomie, and media hucksterism. (Who says the 1950s were an era of cozy Republican values and Leave It to Beaver morality?) Today many of these films look strained and overbearing, but they created a climate that could accept the doggedly unheroic Evans and the proudly antiheroic Sidney Falco.

3:10 x 2

Mangold’s remake is a re-imagining of Daves’ film, more raw and unsparing. Both films give us the journey to town and a period of waiting in a hotel room. In the original, Daves treats the sequences in the hotel room as a chamber play. Each of Wade’s feints and thrusts gets a rise out of Evans until they’re finally forced onto the street to meet Wade’s gang and the train. Mangold has instead expanded the journey to the railway station, fleshing out the characters (especially Wade’s psychotic sidekick) and introducing new ones. This leaves less space for the hotel room scenes, which are I think the heart of Daves’ film.

At the level of imagery, the new version is firmly contemporary. The west is granitic; men are grizzled and weatherbeaten. When Wade and Evans get into the hotel room, Daves’ low-angle deep-focus compositions are replaced by the sort of brief singles that are common today. As in all Mangold’s work, minute shifts in eye behavior deepen the implications of the dialogue.

Similarly, the cutting, the speediest of any Mangold film, is in tune with contemporary pacing. At an average of 3 seconds per shot, it moves at twice the tempo of Daves’ original. Mangold has been reluctant to define himself by a self-conscious pictorial style. “I think writer-directors have less of a need sometimes to put a kind of obvious visual signature over and over again on their movies . . . . I don’t need to go through this kind of conscious effort to become the director who only uses 500mm lenses.” (2)

Mangold puts his trust in well-carpentered drama and nuanced performances. Daves begins his Yuma with Wade’s holdup of a stage, linking his movie to hallowed Western conventions, but Mangold anchors his drama in the family. His film begins and ends with Evans’ son Bill, who’s first shown reading a dime novel. We soon see his father, already tense and hollowed-out. At the end Mangold gives us a resolution that is more plausible than that of Leonard’s original or Daves’ version. What the new version loses by letting Evans’ wife Alice drop out of the plot it gains by shifting the dramatic weight to Bill in the final moments. The conclusion is drastically altered from the original, and it shocked me. But given Mangold’s admiration for the shadowlands of Sweet Smell, it makes sense.

In an interview Mangold remarks that Mackendrick distrusted film school because it stressed camera technique and didn’t prepare directors to work with actors. “It’s a giant distraction in film schools that in a way, by avoiding the world of the actor, young filmmakers are avoiding the most central relationship of their lives in the workplace.” (3) As we’d expect from Mangold’s other films, the central performances teem with details. Bale cuts up Crowe’s beefsteak, and Crowe gestures delicately with his manacles when he softly demands that the fat be trimmed. Bale’s gaunt, limping Evans, a Civil War casualty, becomes an almost spectral presence; his burning glances reveal a man oddly propelled into bravery by his failures. Crowe’s Ben Wade, for all his intelligence and jauntiness, is oddly unnerved by this farmer’s haunted demeanor. Actors and students of performance will be kept busy for years studying the two films and the way they illustrate different conceptions of the characters and the changes within mainstream cinema.

Sometimes I think that Hollywood’s motto is Tell simple stories with complex emotions. The classic studio tradition found elemental situations and used film technique and great performers to make sure that the plot was always clear. Yet this simplicity harbored a turbulent mixture of contrasting feelings, different registers and resonances, motifs invested with associations, sudden shifts between sentiment and humor. In his commitment to vivid storytelling and psychological nuances, Mangold has found a vigorous way to keep this tradition alive. Sandy would have been proud.

(1) James Mangold, “Afterword,” Clifford Odets and Ernest Lehman, Sweet Smell of Success (London: Faber, 1998), 165.

(2) Quoted in Stephan Littger, The Director’s Cut: Picturing Hollywood in the 21st Century (New York: Continuum, 2006), 317.

(3) Quoted in Littger, 313.

PS 9 Sept: Susan King’s article in the Los Angeles Times explains that Mangold first got acquainted with Daves’ film in Mackendrick’s class. “We would break down the dramatic structure of the film. This one really got under my skin, partly because it always really moved me. It also felt original in scope in that it was very claustrophobic and character-based.” King’s article gives valuable background on the difficulties of getting the film produced.

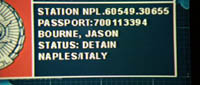

[insert your favorite Bourne pun here]

DB here:

You may be tired of hearing about The Bourne Ultimatum, but the world isn’t.

It’s leading in the international market ($52 million as of 29 August) and has yet to open in thirty territories. It’s expected, as per this Variety story, to surpass the overseas total of $112 for the previous installment, The Bourne Supremacy. According to boxofficemojo.com, worldwide theatrical grosses for the trilogy are at $721 million and counting. Add in DVD and other ancillaries, and we have what’s likely to be a $2-$3 billion franchise.

There’s every reason to believe that the success of the series, plus the critical buzz surrounding the third installment, will encourage others to imitate Paul Greengrass’s run-and-gun style. In an earlier blog, I tried to show that despite Greengrass’s claims and those of critics:

(1) The style isn’t original or unique. It’s a familiar approach to filmmaking on display in many theatrical releases and in plenty of television. The run-and-gun look is one option within today’s dominant Hollywood style, intensified continuity.

(2) The style achieves its effect through particular techniques, chiefly camerawork, editing, and sound.

(3) The style isn’t best justified as being a reflection of Jason Bourne’s momentary mental states (desperation, panic) or his longer-term mental state (amnesia).

(4) In this case the style achieves a visceral impact, but at the cost of coherence and spatial orientation. It may also serve to hide plot holes and make preposterous stunts seem less so.

I got so many emails and Web responses, both pro and con, that I began to worry. Did I do Ultimatum an injustice? So I decided to look into things a little more. I rewatched The Bourne Identity, directed by Doug Liman, and Greengrass’s The Bourne Supremacy on DVD and rewatched Ultimatum in my local multiplex. My opinions have remained unchanged, but that’s not a good reason to write this followup. I found that looking at all three films together taught me new things and let me nuance some earlier ideas. What follows is the result.

For the record: I never said that I got dizzy or nauseated. The blog entry did, however, try to speculate on why Greengrass’s choices made some viewers feel queasy. Some of those unfortunates registered their experiences at Roger Ebert’s site. For further info, check Jim Emerson’s update on one guy who became an unwilling receptacle.

Another disclaimer: For any movie, I prefer to sit close to the screen. In many theatres, that means the front row, but in today’s multiplexes sitting in the front row forces me to tip back my head for 134 minutes. So then I prefer the third or fourth row, center. From such vantages I’ve watched recent shakycam classics like Breaking the Waves and Dogville, as well as lesser-known handheld items like Julie Delpy’s Looking for Jimmy. My first viewing of Ultimatum was from the fifth row, my second from the third. (1)

Finally: There are spoilers ahead, pertaining to all three films.

How original?

Someone who didn’t like the films would claim that they’re almost comically clichéd. We get titles announcing “Moscow, Russia” and “Paris, France.” You can poke fun at lines of dialogue like “What connects the dots?” and “You better get yourself a good lawyer” and the old standby “What are you doing here?” But these are easy to forgive. Good films can have clunky dialogue, and you don’t expect Oscar Wilde backchat in an action movie.

More significantly, all three films are quite conventionally plotted. We have our old friend the amnesiac hero who must search for his identity. Neatly, the word bourne means a goal or destination. It also means a boundary, such as the line between two fields of crops–just as our hero is caught between everyday civil law and the extralegal machinery of espionage.

The film’s plot consists of a series of steps in the hero’s quest. Each major chunk yields a clue, usually a physical token, that leads to the next step. Add in blocking figures to create delays, a hierarchy of villains (from swarthy and unshaven snipers to jowly, white-haired bureaucrats), a few helpers (principally Nicky and Pam), and a string of deadlines, and you have the ingredients of each film. (Elsewhere on this site I talk about action plotting.) The last two entries in the series are pretty dour pictures as well; the loss of Franka Potente eliminates the occasional light touch that enlivened Bourne Identity right up to her nifty final line

All three films rely on crosscutting Bourne’s quest with the CIA’s efforts to find him, usually just one step behind. Within that structure most scenes feature stalking, pursuits, and fights. In the context of film history, this reliance on crosscutting and chases is a very old strategy, going back to the 1910s; it yields one of the most venerable pleasures of cinematic storytelling.

Mixed into the films is another long-standing device, the protagonist plagued by a nagging suppressed memory. Developing in tandem with the external action, the fragmentary flashbacks tease us and him until at a climactic moment we learn the source: in Supremacy, Bourne’s murder of a Russian couple; in Ultimatum, his first kill and his recognition of how he came to be an assassin. The device of gradually filling in the central trauma goes back to film noir, I think, and provides the central mysteries in Hitchcock’s Spellbound and Marnie.

By suggesting that the films are conventional, I don’t mean to insult them. I agree with David Koepp, screenwriter of Jurassic Park and Carlito’s Way, who remarks:

There are rules and expectations of each genre, which is nice because you can go in and consciously meet them, or upend them, and we like it either way. Upend our expectations and we love it—though it’s harder—or meet them and we’re cool with it because that’s all we really wanted that night at the movies anyway. (2)

There can be genuine fun in seeing the conventions replayed once more.

The series makes some original use of recurring motifs, the most obvious being water. The first shot of the first film shows Jason floating underwater; in the second film he bids farewell to the drowned Marie underwater; and in the last shot of no. 3, we see him submerged in the East River, closing the loop, as if the entire series were ready to start again. There’s also a weird parallel-universe moment when Pam tells Jason his real name and birthdate. She does it in 2, and then, as if she hasn’t done it before, tells him again in 3, in what seem to be exactly the same words. In 3, though, it has a fresh significance as a coded message, and a new corps of CIA staff is listening in, so probably the second occurrence is a deliberate harking-back. Or maybe Bourne’s amnesia has set in again. [Note of 9 Sept: Oops! Something that’s going on here is more interesting than I thought. See this later entry.]

The look of the movies

The big arguments about Ultimatum center on visual style. The filmmakers and some critics, notably Anne Thompson, have presented the style as a breakthrough. But again, the movie is more traditional than it might first appear.

In a film of physical action, the audience needs to be firmly oriented to the space and the people present. The usual tactic is to present transitional shots showing people entering or leaving the arena of action. What might be filler material in a comedy or drama—characters driving up, getting out of their vehicles, striding along the pavement, entering the building—is necessary groundwork in an action sequence. So we see Bourne arriving on the scene, then his adversaries arriving and deploying themselves, in the alternation pattern typical of crosscutting. Surprisingly, for all the claims made about the originality of Greengrass’s style in 2 and 3, he is careful to follow tradition and give us lots of shots of people coming and going, setting up the arena of confrontation.

Then the director’s job is just beginning. Traditionally, once the scene gets going, the positions and movement of the figures in the action arena should be clearly maintained. Likewise, it’s considered sturdy craftsmanship to delineate the overall space of the scene and quietly prepare the audience for key areas—possible exits, hiding places, relations among landmarks. (See this entry for how one modern director primes spaces in an action scene.) I claimed in the earlier entry that such basic orienting tasks aren’t handled cogently in Ultimatum, and a second viewing of the scene in Waterloo Station and the chase across the Tangier rooftops hasn’t made me change that opinion. Later I’ll discuss how Greengrass and some commentators have defended the loss of orientation in such scenes.

All the films in the trilogy employ traditional strategies of setting up the action sequences, but the series displays an interesting stylistic progression. In Identity, Liman gives us mostly stable framings and reserves handheld bits for moments of tension and point-of-view shots. He saves his fastest cutting for fights and chases.

Supremacy displays a more mixed style. It contains passages of wobbly, decentered framing, but those exist alongside more traditionally shot scenes—stable framing, with smooth lateral dollying and standard establishing shots. There are some aggressive cuts, as in the crisp emphasis on the sniper at the start of the first pursuit, but on the whole the editing isn’t more jarring than usual these days. We also get, as I mentioned in the earlier entry, some almost willfully obscure over-the-shoulder shots, and occasionally we get the eye-in-the-corner technique that would become more prominent in Ultimatum.

As we’d expect, in Supremacy the bounciest camerawork and choppiest editing are found in the sequences of the most energetic physical action. Most of the surveillance scenes get a little bumpy, while the chases are wilder. The most extreme instance, I think, is the very last chase in the tunnel, when Bourne avenges the death of Marie and slams the sniper’s vehicle into an abutment. As in Identity, Supremacy arrays its technique along a continuum, saving the most visceral techniques for the most brusing action sequences.

So Ultimatum raises the stakes by applying the run-and-gun style more in a more thoroughgoing way. Everything is dialed up a notch. The flashbacks are more expressionistic than those of Supremacy: instead of dark hallucinations we get blinding, bleached-out glimpses of torture and execution, in staggered and smeared stop-frames. The conversation scenes are bumpier and more disjointed; the cat-and-mouse trailings are more disorienting, with jerky zooms and distracted framings; the full-bore action scenes are even more elliptical and defocused. It’s as if the visual texture of Supremacy’s tunnel chase has become the touchstone for the whole movie.

That texture I tried to describe in the earlier entry. Greengrass relies on camerawork, cutting, and sound to convey the visceral impact of action, rather than showing the action itself. The most idiosyncratic choices include framing that drifts away from the subject of the shot, oddly offcenter compositions, and a rate of cutting that masks rather than reveals the overall arc of the action. Some critics have liked the film’s technique, some have hated it, but I think my account stands as a fair account of the destabilizing tactics on the screen, and a likely source of some spectators’ vertigo.

Run-and-gun, with a gun

The style of Ultimatum is a version of what filmmakers call run-and-gun: shot-snatching in a pseudo-documentary manner. This approach has a long history in American film. The bumpy handheld camera, I tried to show in The Way Hollywood Tells It, has been repeatedly rediscovered, and every time it’s declared brand new. I have to admit I’m startled that critics, who probably have seen Body and Soul, A Hard Day’s Night, The War Game, Seven Days in May, or Medium Cool, continue to hail it as an innovation. Today it’s a standard resource for fictional filmmaking, to be used well or badly.

What’s at issue here are the role it plays and the effects it achieves. In Lars von Trier’s The Idiots, I’d argue that handheld work becomes genuinely disorienting because the camera is scanning the scene spontaneously to grab what emerges. But von Trier’s roaming camera yields rather long takes compared to what we find in the Bourne series. Greengrass is practicing what I called, in Film Art and The Way Hollywood Tells It, intensified continuity.

This approach breaks down a scene so that each shot yields one, fairly straightforward piece of information. The hero arrives at the station. Car pulls up; cut to him getting out; cut to him walking in. Traditional rules of continuity—matching screen direction, eyelines, overall positions in the set—are still obeyed, but the dialogue or physical action tends to be pulverized into dozens of shots, each one telling us one simple thing, or simply reiterating what a previous shot has shown. (Oddly, sometimes intensified continuity seems more, rather than less, redundant than traditional continuity cutting.)

Within the intensified continuity approach, we can find considerable variation. I argued that one highly mannered version can be found in Tony Scott’s later work, where the shots are fragmented to near-illegibility and treated as decorative bits. You can find Scott’s signature look tawdry and overwrought, but Liman and Greengrass belong in the same tradition. All three directors rely on telephoto lenses, for example, and they have recourse to well-proven techniques for rendering hallucinatory states of mind, as in these multiple-exposure shots, one from Man on Fire and the second from Bourne Supremacy.

Despite the stylistic differences among the three Bourne films, the basic one-point-per-shot premises remain in place. Here’s a passage from Supremacy. Jason gets off the train in Moscow. We get an establishing shot of the station as the train pulls in, followed by a shot of him getting off, moving left to right. The establishing shot is a smooth craning movement down, but the following shot is a little shaky.

Then we get a blurry shot of him walking, taken with a very long lens. A head-on shot like this traditionally creates a transition allowing the filmmaker to cross the axis of action, letting Jason walk right to left in the next shot.

Cut to closer view: Jason turns his head slightly. Cut to what he sees, in a shaky pov: Cops.

The answering handheld shot shows Jason reacting. As he strides on purposefully, a still closer shot accentuates his eye movement and adds a beat of tension.

Jason turns and goes to the pay phones, followed by the unsteadicam, then turns his head watchfully. A smooth match-on-action cut brings us closer.

But then Jason turns back to his task, and suddenly a passerby blots out the frame.

When the frame clears, a jouncy shot shows Jason’s hands thumbing a phone book. This might be a continuation of the same shot, or the result of a hidden cut. I suggest in The Way Hollywood Tells It that such stratagems are common in intensified continuity: blotting out the frame, flashing strobe lights, and other devices can create a pulsating rhythm akin to that of cutting. Jason turns the pages, and a jump cut shows him on another page.

Cut back to him scanning the pages. He writes down an address, in a very shaky framing.

Cut back again to Jason, and another smooth match-on action brings us back to the slightly fuller framing we’ve seen already. Greengrass shoots with at least two cameras simultaneously, which can facilitate match-cutting like this.

Jason strides toward us, going out of focus. Then a stable long shot pans with him, moving left as before. He leaves the station.

A very simple piece of action has been broken into many shots, some of them restating what we’ve already seen. In the days of classic studio filming, most directors wouldn’t have given us so many shots of Bourne leaving the train platform; a single tracking shot would have done the trick. A single shot could have shown us Jason at the phone, scribbling down the address. As a result, the whole passage is cut faster than in the classic era. The sequence lasts only forty-one seconds but shows sixteen shots. Two to three seconds per shot is a common overall average for an action picture today. The rapid cutting helps create that bustle that Hollywood values in all its genres.

It’s clear, I think, that here the run-and-gun technique is laid over the premises of intensified continuity, letting each shot isolate a bit of narrative information to make sure we understand, even at the risk of reiterating some bits. Jason has arrived in Moscow, he has to be careful because cops are everywhere, now he needs an address, he finds it, he’s writing it down . . . . All of this action is bookended by long shots that pointedly show us the character arriving at the station and leaving it.

I suggested in the earlier entry that in Ultimatum, Greengrass takes more risks than in the previous film. He still assigns one piece of information per shot, but now that piece is sometimes not in focus, or slips out of the center of the frame, or is glimpsed in a brief close-up. The September issue of American Cinematographer, which arrived as I was completing this entry, explains that he encouraged his camera operators to follow their own instincts about focus and composition. (3) Seeing Ultimatum again, I realized that the film can get away with this sideswiping technique by virtue of certain conventions of genre and style.

A telltale clue, like the charred label left over from a car bomb, can be given a fleeting close-up because physical tokens are carrying us from scene to scene throughout the film and we’re on the lookout for them. A sniper racing away out of focus in the distance is a character we’ve seen before, and he’s spotted in frame center before he dodges away. The larger patterning of shots relies on crosscutting or point-of-view alternation (Jason looks/ what he sees/ Jason reacts), and so the framing of any shot can be a little less emphatic. Given intensified continuity’s emphasis on tight close-ups for dialogue, faces can be framed a little loosely, trusting us to pick up on what matters most—changes in facial expression.

In short, because there’s only one thing to see, and it’s rather simple, and it’s the sort of thing we’ve seen before in other films and in this film, it can be whisked past us. This tactic crops up from time to time in Liman’s first installment, when a shot seems to fumble for a moment before surrendering the key piece of data. For example, Jason is striding through the hotel and a wobbly point-of-view shot brings the hotel’s evacuation map only partly into view.

Again, Greengrass takes a visual device that was used occasionally in Identity and extends it through an entire film.

Realism, another word for artifice

Finally, what’s the purpose behind Ultimatum’s thoroughgoing exploitation of run-and-gun? I quoted Greengrass’s claim that it conveys Bourne’s mental states, and some critics have rung variations on this. Of course the cutting is choppy and the framing is uncertain. The guy’s constantly scanning his environment, hypersensitive to tiny stimuli. Besides, he’s lost his memory! Yet the same treatment is applied to scenes in which Bourne isn’t present—notably the scenes in CIA offices. Is Nicky constantly alert? Is Pam suffering from amnesia?

Alternatively, this style is said to be more immersive, putting us in Bourne’s immediate situation. This is a puzzling claim because cinema has done this very successfully for many years, through editing and shot scale and camera movement. Don’t Rear Window and the Odessa Steps sequence in Potemkin and the great racetrack scene in Lubitsch’s Lady Windermere’s Fan thrust us squarely into the space and demand that we follow developing action as a side-participant? I think that defenders need to show more concretely how Greengrass’s technique is “immersive” in some sense that other approaches are not. My guess is that that defense will go back to the handheld camera, distractive framing, and choppy cutting . . . all of which do yield visceral impact. But why should we think that they yield greater immersion?

I think we get a clue by recalling that Supremacy and Ultimatum display the run-and-gun strategy that Greengrass employed in Bloody Sunday and United 93. This approach implies something like this: If several camera operators had been present for these historic events, this is something like the way it would have been recorded. We get a reality reconstructed as if it were recorded by movie cameras. I say cameras because we’re telling a story and need to change our angles constantly; a scene couldn’t approximate a record of the event as experienced by a single participant or eyewitness. In movies, the camera is almost always ubiquitous.

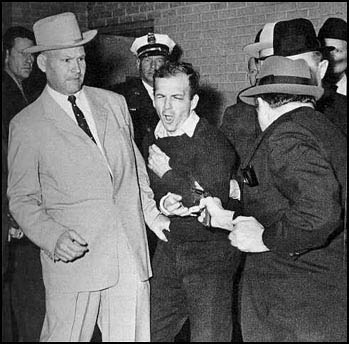

Recall the famous TV footage of Jack Ruby shooting Lee Harvey Oswald. There the lone camera lost some of the most important information by being caught in the crowd’s confusion and swinging wildly away from the action. But in a fiction film, we can’t be permitted to miss key information. So with run-and-gun, the filmmakers in effect cover the action through a troupe of invisible, highly mobile camera operators. That’s to say, another brand of artifice.

In general, the run-and-gun look says, I’m realer than what you normally see. In the DVD supplement to Supremacy, “Keeping It Real,” the producers claimed that they hired Greengrass because they wanted a “documentary feel” for Bourne’s second outing. Greengrass in turn affirms that he wanted to shoot it “like a live event.” And he justifies it, as directors have been justifying camera flourishes and fast cutting for fifty years, as yielding “energy. When you get it, you get magic.” (4)

I’d say that the style achieves visceral disorientation pretty effectively, but some claims for it are exaggerated. So far Greengrass has matched the style to hospitable genres, either historical drama or fast-paced espionage. But isn’t immersion something we should try for in all genres? Wouldn’t High School Musical 2 gain energy and magic if it were shot run-and-gun? If a director tried that, some critics might say that it added intensity and realism, and suggest that it puts us in the minds and hearts of those peppy kids in a way that nothing else could.

I finish this overlong post by invoking Andrew Davis, director of The Fugitive (which back in 1993 gave us fragmentary flashbacks à la Bourne Ultimatum) and the admirable Holes.

When you think about the beginnings: everything was very formal and staged and composed, and then years later people said, “We want it shaky and out of focus and have some kind of honest energy to it.” And then it became a phony energy, because it was like commercials, where they would make everything have a documentary feel when they were selling perfume, you know? (5)

Whether you agree with me or not, I’m glad that The Bourne Ultimatum raised issues of film style that audiences really care about. I’m eager to look more closely at the movie when the DVD is released, but don’t worry–I don’t expect to mount another epic blog entry.However, I do have an item coming up that talks about how we assess what filmmakers say about their movies….

(1) I’m aware that this can be an uncomfortable option, but not as bad as with music. Many years ago I sat in the front row of a John Zorn concert, and I don’t think my ears ever recovered.

(2) Quoted in Rob Feld, “Q & A with David Koepp,” in Josh Friedman and David Koepp, War of the Worlds: The Shooting Script (New York: Newmarket Press, 2005), 136-137.)

(3) See Jon Silberg, “Bourne Again,” American Cinematographer (September 2007), 34-35, available here.

(4) Oddly, though, in the DVD supplement to The Bourne Identity, Frank Oz says that Liman brought “a rough-edged, very energetic” feel to the project, thanks to his indie roots. Interestingly, the energy is attributed to Liman’s abilities as a camera operator, a skill that enables him to shoot things quickly. The same supplement offers a familiar motivation for the film’s purportedly jittery style: the hero is trying to figure out who he is, and so is the viewer. Just as the films revamp a basic plot structure each time, perhaps the producers’ rationales get recycled too.

(5) Quoted in The Director’s Cut: Picturing Hollywood in the 21st Century, ed. Stephan Littger (NY: Continuum, 2006), 96.

PS: On a wholly unrelated subject Kristin answers a question on Roger Ebert’s Movie Answer Man column: What was the first movie?

PPS 5 January 2008: Steven Spielberg weighs in on the Bourne style here, confirming that he’s a more traditional filmmaker. Thanks to Fred Holliday and Brad Schauer for calling my attention to his remarks.

Unsteadicam chronicles

DB again:

A spectre is haunting contemporary cinema: the shaky shot.

Viewers have been protesting for some years now. I recall friends asking me why the images were so bumpy in Woody Allen’s Husbands and Wives and Lars von Trier’s Dancer in the Dark. The Bourne Ultimatum, this summer’s wildest excursion into Unsteadicam, has put the matter back on the agenda.

If you drop in at Roger Ebert’s website, you’ll find many annoyed comments from readers about what one calls the Queasicam. The writers make shrewd points about the purpose and effects of director Paul Greengrass’s technique. I’ll try to add some historical perspective and a little analysis.

From whose Bourne no traveling shot returneth

First, what exactly are we talking about? Some viewers and critics think the jarring quality of the movie proceeds from rapid editing. The cutting in Bourne Ultimatum is indeed very fast; there are about 3200 shots in 105 minutes, yielding an average of about 2 seconds per shot. But there are other fast-cut films that don’t yield the same dizzy effects, such as Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow (1.6 seconds average), Batman Begins (1.9 seconds), Idiocracy (1.9 seconds), and the Transporter movies (less than 2 seconds).

As for the series itself, The Bourne Identity, directed by Doug Liman, was edited a tad slower, averaging 3 seconds per shot. The second entry, The Bourne Supremacy, also signed by Greengrass, was as fast-cut as this, coming in at 1.9 seconds. People noticed the rough texture of the second one, but it didn’t arouse the protests that this last installment does. Something else is up.

Partly, it’s not the pace of the editing but the spasmodic quality of it. Cuts here seem abrasive because they interrupt actions and camera movements. Pans, zooms, and movements of the actors are seldom allowed to come to rest before the shot changes. This creates a strong sense of jerkiness and visual imbalance.

Still, a lot of the film’s effect has to be laid at the handheld camera. The technique in itself, however, shouldn’t shock us. The handheld aesthetic has been with us a long time. There were silent-era experiments with the technique by E. A. Dupont (Variety, 1925) and Abel Gance (Napoleon, 1927). It recurred sporadically after that, but in mainstream cinema handheld shooting became common in 1960s films as different as The Miracle Worker, Seven Days in May, Dr. Strangelove, and the dramas of John Cassavetes. Today, many films from Asia and Europe as well as the US rely on the device all the way through. The Danes call it the “free camera,” and I write about it here. The trend is so widespread that it’s been satirized: In the Danish comedy Clash of Egos (2006), when an ordinary workman gets a chance to direct a movie, he insists that the camera be put on a tripod, and the cinematographer complains that he hasn’t done this since film school. Directors nowadays tell us that they are in search of energy, a moment-by-moment spiking of audience interest. You can get it through fast cutting, arcing camera movements, sudden frame entrances, the nervousness of the handheld shot, or all of the above.

Roughhouse

I think the upsetting qualities of the visuals in The Bourne Ultimatum derive principally from the particular way the handheld camera is used. Several of Ebert’s writers complain that the camerawork made them nauseated, and there seems little doubt that the shots are bouncier and jerkier than in much handheld work. Adding to the effect is the fact that Greengrass often doesn’t try to center or contain the main action. Sometimes, as in a fight scene, the camera is just too close to the action to show everything, so it tries to grab what it can. At other times Greengrass pans away from the subject, or shoves it to the edge of the 2.40:1 frame. In the standard technique of over-the-shoulder reverse angles, we see one character’s shoulders in the foreground and the primary character’s face clearly. Greengrass likes to let a neck or shoulder overwhelm the composition as a dark mass, so that only a bit of the face, perhaps even just a single eye, is tucked into a corner of the shot. This visual idea was already on offer in The Bourne Supremacy.

In The Way Hollywood Tells It, I described contemporary films as employing “intensified continuity,” an amplification and exaggeration of tradition methods of staging, shooting, and cutting. (I explain a little about it in this blog entry.) What Greengrass has done is to roughen up intensified continuity, making its conventions a little less easy to take in. Normally, for instance, rack-focus smoothly guides our attention from one plane to another. But in The Bourne Ultimatum, when Jason bursts into a corridor close to the camera, the camera tries but fails to rack focus on his pursuer darting off in the distance. The man never comes into sharp focus. Likewise, most directors fill their scenes with close-ups, and so does Greengrass, but he lets the main figure bounce around the frame or go blurry or slip briefly out of view.

Essentially, intensified continuity is about using brief shots to maintain the audience’s interest but also making each shot yield a single point, a bit of information. Got it? On to the next shot. Greengrass’s camera technique makes the shot’s point a little harder to get at first sight. Instead of a glance, he gives us a glimpse.

Although this strategy is more aggressive in this third Bourne installment, we can find it as well in Supremacy. An agent pulls a document out of a carryon bag, and for an instant we can see the government seal. In the next shot the agent bobs in and out of the frame, as if the camera can’t anticipate his next move.

Later in Supremacy, the camera jerks across a computer display and suddenly focuses itself, evoking the jumpy saccadic flicks with which we scan our world.

Greengrass claims that his creative choices were influenced by the cinema-vérité documentary school and cites as well The Battle of Algiers, which helped popularize the handheld look in the 1960s. At other times he says that the style is subjective: “Your p.o.v. is limited to the eye of the character, instead of the camera being a godlike instrument choreographed to be in the right place at the right time.” But our point of view isn’t confined to what Bourne or anybody else sees and knows. The whole movie relies on crosscutting to create an omniscient awareness of various CIA maneuvers to trap him. And if Bourne saw his enemies in the flashes we get, he couldn’t wreck them so thoroughly.

The Bourne Ultimatum belongs to a trend of rough-edged stylization sometimes called run-and-gun. The film has been described as bare-bones but it’s actually quite flashy. All the crashing zooms (accompanied by whams on the soundtrack), jittery shots, drifting framings, uncompleted pans, freeze-frame flashbacks, and other extroverted devices call attention to themselves. You can find earlier instances in Oliver Stone’s Natural Born Killers and U-Turn, along with stretches in Michael Mann’s latest films. In milder form you find the style on display in TV crime shows, as well as in the notorious docudrama The Road to 9/11.

The most extreme practitioner of this style is probably Tony Scott. From Spy Game through Man on Fire, Domino, and Déjà vu, he has taken this aesthetic in delirious directions. His framing is often restless, as if groping for the right composition. In this shot from Domino, the camera starts a bit too far to the right, shifts left to frame Frances a little better, zooms back hesitantly, then finally stabilizes itself as he grins at the Motor Vehicles worker.

A single shot may give us not only changes of focus but jumps in exposure, lighting, and color; sometimes it’s hard to say whether we have one shot or several. The result is a series of visual jolts, as in Man on Fire.

Scott, trained as a painter, pushes toward a mannered, decorative abstraction, aided by long-lens compositions and a burning, high-contrast palette. For Supremacy, Greengrass adopted a toned-down version of Scott’s approach, while in Ultimatum, he favors drab surroundings and steely colors. Still, both men’s approaches to run-and-gun are frankly artificial, and both remain within the premises of intensified continuity. Of the Waterloo Station sequence Greengrass says: “It has got a sense of energy.”

The Bourne coverup

There’s one more function of Bourne’s style I want to consider. In an earlier post, I quoted Hong Kong cinematographers’ saying about the shaky camera. The handheld camera covers three mistakes: Bad acting, bad set design, and bad directing. It’s worth considering, as some of Ebert’s correspondents do, what Greengrass’s style may serve to camouflage. One suggests that because the cutting doesn’t let the viewer reconstruct the fights blow by blow, anybody can seem to be a superhero if the filming is flurried enough.

Just as important, the director who is just (apparently) snatching shots doesn’t have to worry about building up performances slowly; s/he can simply give us the most minimal, stereotyped signals in facial close-ups. Lengthier shots let the actor develop the character’s reactions in detail, and force us to follow them. Classic studio cinema, with its more distant framings and longer takes, lets you follow the evolution of a feeling or idea through the actor’s blocking and behavior. The villain in the average Charlie Chan movie displays more psychological continuity than the nasty agents in Bourne Ultimatum.

Moreover, run-and-gun technique doesn’t demand that you develop an ongoing sense of the figures within a spatial whole. The bodies, fragmented and smeared across the frame, don’t dwell within these locales. They exist in an architectural vacuum. In United 93, the technique could work because we’re all minimally familiar with the geography of a passenger jet. But in The Bourne Ultimatum, could anybody reconstruct any of these stations, streets, or apartment blocks on the strength of what we see? Of course, some will say, that’s the point. Jason himself is dizzyingly preoccupied by the immediacy of the action, and so are we. Yet Jason must know the layout in detail, if he’s able to pursue others and escape so efficiently. Moreover, we can justify any fuzziness in any piece of storytelling as reflecting a confused protagonist. This rationale puts us close to Poe’s suggestion that we shouldn’t confuse obscurity of expression with the expression of obscurity.

The run-and-gun style is indeed visceral, but let’s be aware of how it achieves its impact. I’ve argued in Planet Hong Kong that the clean, hard-edged technique of classic Hong Kong films allows extravagant action to affect us viscerally; by following the action effortlessly, we can feel its bodily impact. We’re shown bodies in sleek, efficient movement that gets amplified by cogent framing and smooth matches on action. But in the fancy run-and-gun style, cinematography and sound do most of the work. Instead of arousing us through kinetic figures, the film makes bouncy and blurry movement do the job. Rather than exciting us by what we see, Greengrass tries to arouse us by how he shows it. The resulting visual texture is so of a piece, so persistently hammering, that to give it flow and high points, Greengrass must rely on sound effects and music. As a friend points out, we understand that Bourne is wielding a razor at one point chiefly because we hear its whoosh.

What else does the handheld style conceal? Since the 1980s, in many action pictures the cutting has become so fast, and often capricious, that we can’t clearly see the physical action that’s being executed. That complaint is justified in Bourne Ultimatum, certainly, but here the style also seeks to make the stunts seem less preposterous. Instead of showing cars crashing and flipping balletically, Greengrass barely lets us see the crash. All the conventions of the action film are smudged in Bourne Identity, as if a sketchy rendering made them seem less outlandish. In a Hong Kong film, Bourne in striding flight, grabbing objects to use as weapons without missing a beat, would be presented crisply, showing him executing feats of resourceful grace. But many viewers seem to find this sort of choreography outlandish or cartoony. So when Bourne plucks up pieces of laundry and wraps them around his hands to protect them when he vaults a glass-strewn wall, Greengrass’s shot-snatching conceals the flamboyance of the stunt.

Finally, I’d argue that the style camouflages something else: plot problems. I’m not talking about the hero’s indestructibility, which is a given in this genre. John McClane in Die Hard 4.0 survives about as much mayhem as does Jason Bourne. But there are some howlers here that, because of the rapid pace and the just-barely-visible action, are somewhat muffled. By whisking the action past us and forcing us to keep up, the film doesn’t allow us to dwell on its holes and thin patches.

The plot, praised by so many, is actually a very simple one: Find Guy A, but when he’s killed, locate the clues that will lead you to Guy B, etc. until you get to Mr. Big. The mechanics of how the clues are pursued remain obscure. (Skip ahead to the next paragraph if you haven’t seen the movie.) Why would an all-powerful CIA operation house its key players in offices that can easily be watched from a neighboring building? How does Bourne get into Noah Vosen’s office, past all the security? Is the revelation of Bourne’s identity and his training regimen really much of a surprise? The wrapup, showing the bad guys exposed by the press and punished by government investigation, seemed risible, not only because of the current inability of either press or congress to right any wrongs, but because I had no idea to whom Pamela Landy has faxed the incriminating documents. “You can’t make stuff like this up,” remarks one sinister agency boss, but many, many films have done so.

I’m not against handheld styles as such, and even Late Tony Scott Rococo can have its virtues. Yet I find the style as practiced by Greengrass to be pretty incoherent and nowhere near as engaging as most critics claim. It just seems too easy. But then, I think that certain standards of filmmaking craftsmanship have pretty much vanished, and the run-and-gun trend is one more symptom of that. Given the praise heaped on The Bourne Ultimatum, however, things are unlikely to change. Next time you head to the movies, you might want to bring your Dramamine.

Thanks to Vance Kepley and Jeff Smith for engaging discussion about The Bourne Ultimatum.

The Bourne Supremacy.

PS: I’ve done a followup entry on the Bourne series, elaborating on these points and adding some new ones.

PPS: One more, I hope final, cluster of comments on Ultimatum, this time on the plotting.

PPPS 5 January 2008: Spielberg weighs in on the Bourne style; thanks to Fred Holliday and Brad Schauer for calling my attention to this.

PPPPS 22 September 2008: This blog post and its mates have stimulated critical discussion in Spain. Manuel Garin has a lengthy piece on the Unsteadicam style in Contrapicado.

Two Chinese men of the cinema

A Brighter Summer Day.

DB here:

This summer two major figures in Chinese filmmaking died. One was Edward Yang (Yang Dechang), one of Taiwan’s finest directors, who died on 29 June. But before I pay tribute to him, I want to acknowledge another figure who had a great impact on Asian cinema.

Charles Wang died on 6 July. Along with his brother Fred, Dr. Wang ran Salon Films, the major supplier of film equipment for Hong Kong and a principal one for East Asia and the Pacific Rim. Charles graduated with a degree in chemistry before inheriting the business from his father. As Hong Kong filmmaking grew in sophistication, Salon grew along with it. Most Hong Kong films bear the firm’s brand in their end credits.

Since 1969 Salon has provided top-flight cameras, lenses, lighting gear and other technical support for both local and visiting productions, such as Mission: Impossible III‘s Shanghai shoot. An early triumph was winning the Panavision franchise for the region. The company even supplies trampolines and landing cushions for martial acrobatics, as this glimpse inside a Salon van shows.

Since 1969 Salon has provided top-flight cameras, lenses, lighting gear and other technical support for both local and visiting productions, such as Mission: Impossible III‘s Shanghai shoot. An early triumph was winning the Panavision franchise for the region. The company even supplies trampolines and landing cushions for martial acrobatics, as this glimpse inside a Salon van shows.

When I interviewed Dr. Wang in 2003 he kindly gave me information about the company and the development of film technology in Hong Kong. He showed me his many awards and talked enthusiastically about Salon’s new efforts to assist mainland moviemaking. In recent years, Salon was investing in films such as Zhang Yimou’s Hero. Like most Hong Kong film people, he was very accessible and generous; he even gave me a lift back to my hotel. Charles Wang was a major force in the Hong Kong industry and will certainly be missed.

Laconic cuts and long takes

I met Edward Yang twice. First, at a Hong Kong Film Festival reception, we chatted about his film Mahjong (1996), which had screened. I got to know him a little better in fall of 1997, when we were both invited to the Kyoto Film Festival. We ate and watched films together, and we shared baby-boomer nostalgia; it turns out that he and I (and Hou Hsiao-hsien) were all born in the same year.

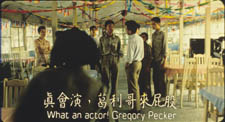

I found him friendly, thoughtful, and open to appreciating all film traditions. He spoke of enjoying Japanese swordplay movies in his youth, and he admired American films for their gripping stories. Still, his preference for ellipsis and understatement came through. When we met Kitano Takeshi for dinner, Edward praised a crisp transition in Sonatine: to show the gang going from Tokyo to Okinawa, Kitano simply gives us a quick pan of the sky accompanied by the sound of a jet plane.

Yang was an accomplished cartoonist, and I thought that this background partly explained his early style, on display in the short film Desires (1982) and in the features That Day, on the Beach (1983), Taipei Story (1985), and The Terrorizers (1986). In these films Yang often breaks his scenes into simple but striking fragments. After the police shootout in The Terrorizers—one of the most enigmatic and elliptical opening sequences in modern cinema—the Eurasian girl staggers out to the street. Yang gives us her collapse in quite abstract, percussive images. Her foot hits the pavement. Cut. She takes a step and falls out of frame; the camera holds on the empty frame. Cut. She’s lying on the crosswalk. I imagine these as forceful, laconic comic-book panels.

With A Brighter Summer Day (1991), my favorite of his works, Yang tells another gap-filled story but treats the scenes in long, distant, often decentered takes reminiscent of Hou. Now his frames are more dense with figures and furniture, and layers of action extend quite far back. In Figures Traced in Light, I devote a little—too little—analysis to one admirably staged passage. Another of my favorite scenes in A Brighter Summer Day shows the hero Xiao S’ir developing a romantic attachment to Ming, the girlfriend of the absent gang leader Honey. They sit in a brightly decorated café.

Suddenly Ming darts out of the shot, leaving Xiao S’ir and the other boys staring. From their point of view we see that Honey, dressed in a sailor suit, has returned and Ming has gone to meet him.

Yang cuts back to the boys as Honey’s gang starts to threaten Xiao S’ir. Abruptly, Ming runs into the shot, past the boys, down the long central aisle, and out of the café. (In a 35mm print you can see her pausing and lingering outdoors.)

The group closes around Xiao S’ir; only Honey’s entry breaks the tension. He leads the boy into the depth of the shot, the camera following them.

Honey warns Xiao S’ir off, and our hero goes outside, mimicking the path Ming had followed.

As Honey turns his attention to his gang and an upcoming skirmish with their rivals, he moves back down the aisle, the camera backing up. Once his business is done, Honey drifts back to the rear door.

Honey pauses far from us, at the window. Yang cuts to show what he sees: Xiao S’ir, in flagrant violation of the warning, talking to Ming outside.

First we got Xiao S’ir’s point of view on Honey and Ming; now, in a reversal, we get Honey’s point of view on Ming and Xiao S’ir. In scenes like this, Yang merges his developing skills in long-take staging with cuts that develop not only the action but story parallels. Very distant framings, characters moving to the rear of the shot and turning their backs: Yang “dedramatizes” the scene. Further, by shifting point of view, he leaves us guessing about story information: What led to Ming’s running away from Honey? What are Xiao S’ir and Ming talking about now? Yang created a laconic visual approach that, I’d argue, invests fairly standard dramatic situations with a tantalizing uncertainty.

Yang’s best-known film is, of course, Yi Yi (2000), and it won him the wide appreciation that he had long deserved. It’s a warm and gentle work, less innovative than his earlier efforts but utterly typical of his vision of lives pervaded by melancholy routine and abrupt disappointment. People often remarked that the adolescent hero of A Brighter Summer Day resembled Edward himself. Perhaps too in Yi Yi Yang’s enigmatic pictorialism is echoed in the idea of a little boy who makes photographs of people’s heads seen from the rear. Like the director, the boy (named Yang-yang) displays a reticence that respects the mysteries of people’s private lives.

We already have a very useful guide to Yang’s work in one chapter of Emilie Yueh-Yu Yeh and Darrell William Davis’ book, Taiwan Film Directors. And Criterion’s Curtis Tsui has done a wonderful edition of Yi Yi, as Brian Hu shows here. We must hope that Criterion, Eureka, or another gilt-edged DVD publisher will soon bring us Yang’s other works in the pristine editions they deserve.

A Brighter Summer Day (1991)

In 1998, when we screened A Brighter Summer Day at our Cinémathèque, I wrote a program note. I reproduce it, lightly revised, as a quick pointer to one of the great films of the 1990s.

With Taipei Story (1985) and The Terrorizers (1986) Edward Yang established himself as one of the two leaders of the Taiwanese New Wave generation. At first it seemed that he and Hou Hsiao-hsien had agreed to a division of labor in their subjects and styles. Hou tended to concentrate on life in the countryside, or on rural characters transplanted, bewilderingly, to the modern city. Hou was also deeply interested in the history of Taiwan; his most acclaimed film, City of Sadness (1989), is a panoramic survey of Taiwanese society immediately after World War II. Hou’s tranquil style favored a contemplative mood and muted emotion.

Yang, by contrast, tended to focus on the lives of well-to-do urbanites in a contemporary setting, Taiwanese yuppies plagued by anomie and the desperation of love and work. His elliptical editing technique, reminiscent of Resnais, fractured time and space, while his compositions had a painterly starkness. The Terrorizers shuttles kaleidoscopically among characters at its beginning; their relations only gradually settle into intelligible patterns. Whereas Hou tended toward nuance and quiet drama, Yang was unafraid of shocking, inexplicable bursts of bloodshed.

Now it seems evident that this impression of a division of labor was somewhat schematic. Hou’s range of interests has widened, with new emphasis on the violent world of urban crime (Goodbye South Goodbye, 1996), and he has come to rely on quite disorienting transitions between past and present (Good Men, Good Women, 1995). Likewise, with A Brighter Summer Day Yang turned to history and cultivated a more sober style of filming, with lengthier shots and a fixed or barely moving camera. This approach throws down a challenge to the razzle-dazzle of contemporary popular cinema—from Hollywood, Hong Kong, and even the American “independents”—and invites us to scrutinize, moment by moment, the details of action unfolding on the screen.

Three years in the making, A Brighter Summer Day was a triumph of independent production. At a period when the Taiwanese film industry was virtually dead, Yang found money (mostly Japanese) to mount a project of remarkable ambition. Over half the cast and crew had never worked on a film before. At first released in a three-hour version, the film was re-released in a four-hour director’s cut, and this has become the standard version.

The historical event examined in A Brighter Summer Day took place in Taipei in the 1960s, when an adolescent boy about Yang’s age stabbed a young woman. At epic length Yang creates a web of circumstances around the event. He shows the interplay of traditional culture—filial duty, education as an ideal of social advancement—with popular culture, especially the rock n’ roll songs that recur throughout. Yang has said that Americans might not realize the shattering force of rock in other cultures: “These songs made us think of freedom.”

The film has over eighty speaking parts, most filled by nonactors, and it intertwines several characters’ destinies. On first viewing, the film can be somewhat bewildering to a non-Taiwanese audience, so a plot sketch may help. (Skip to the next paragraph if you don’t want to know the action in advance.) At the center is fourteen-year-old Xiao Si’r. He tries to be a dutiful student, but with his friends Cat and Airplane, he lives on the fringes of the Little Park gang of teenage thugs. When Xiao Si’r reports seeing a gang member with another boy’s girlfriend, he triggers a power struggle in the gang. As his friends fall by the wayside and rival gangs fight for control of local turf, Xiao S’ir becomes involved with Ming, a girl who’s attached to Honey, exiled leader of the Little Park gang. A major climax occurs during a gang rumble at a rock n’ roll concert. Interwoven with the juvenile intrigues are political matters; the police pursue and question Xiao S’ir’s father about his Communist friends. Xiao S’ir becomes friendly with Ma, a general’s son, before they start to compete for Ming’s favor. The rivalries build to a tense schoolroom confrontation and a tragic finale in the park. In the final scene and over the credits, a radio transmission broadcasts the names of the students who have passed their school entrance exams.

The plot is even more intricate than my bare-bones summary can indicate; I haven’t discussed the boys’ adventures in a film studio or Cat’s singing career or the slender line of action involving Xiao S’ir’s sister. The breadth of action is extraordinary, and a sense of the contradictory pulls of daily life emerges steadily. No less demanding is Yang’s style—scenes played in darkness, few close-ups, with medium-shots and long-shots keeping us at a distance from the characters. But the result is a dispassionate look at teenaged passions, a deromanticized treatment of young people growing up in a repressive milieu. A Brighter Summer Day (the English title comes from Elvis Presley’s “Are You Lonesome Tonight?”) is an elegy to the ideals and mistakes of youth, an analysis of the vanities of the male ego, and a view of a generation painfully facing the limitations of tradition, the constraints of political oppression, and the demands of the modern world.

Yi Yi.