Archive for the 'Film technique: Editing' Category

Bando on the run

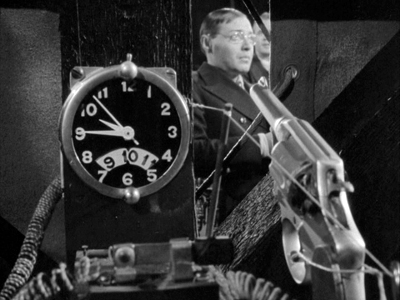

Sakamoto Ryoma (1928).

The Matsuda Eigasha company of Tokyo deserves enormous credit for restoring and making available classic Japanese films. My first visit to the firm twenty years ago was a revelation. Matsuda Shinsui was a former benshi, or spoken-word film accompanist, and he and his sons were collecting old films so that he could accompany them in screenings. A great many of the films were chambara, or swordfight movies. Most survived only in fragments, but what tantalizing fragments they were! (1)

The company made several of the films available on VHS tape, accompanied by benshi commentary prepared by Mr. Matsuda. I came away with several of these treasures. On later visits I was able to watch some films that hadn’t been transferred to video, and several of those deserve to be more widely seen.

When Mr. Matsuda’s son kindly drove me to my train station, I noticed that his car had a VHS player and video monitor installed in the dashboard. So much for my Tokyo-ga experience.

In 1979 Matsuda Eigasha compiled a documentary on the swordplay star Bando Tomasaburo. Now Digital Meme has made it available on DVD, complete with English subtitles. Bantsuma: The Life of Tomasaburo Bando is obligatory viewing for everyone interested in Japanese cinema. Not only does it handily trace Bando’s remarkable career through stills, interviews, and surviving footage. It also supports something I’ve tried to show for some time: that the Japanese action cinema of the 1920s and 1930s was one of the most powerful and creative trends in world filmmaking.

In 1979 Matsuda Eigasha compiled a documentary on the swordplay star Bando Tomasaburo. Now Digital Meme has made it available on DVD, complete with English subtitles. Bantsuma: The Life of Tomasaburo Bando is obligatory viewing for everyone interested in Japanese cinema. Not only does it handily trace Bando’s remarkable career through stills, interviews, and surviving footage. It also supports something I’ve tried to show for some time: that the Japanese action cinema of the 1920s and 1930s was one of the most powerful and creative trends in world filmmaking.

Action and innovation

Some writers have thought that Japanese filmmakers were developing a culturally anchored approach to filmic storytelling independent of Western influences. But in Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema and two essays in my forthcoming Poetics of Cinema, I argue something different. By the early 1920s Japanese filmmakers had mastered Hollywood’s norms of visual storytelling. In the Matsuda documentary, this is evident from the clips from early Bando films like Gyakuryu (1924) and Kageboshi (1924). Long shots are broken up into closer views, and conversations are treated in reverse-angle shots of speaker and listener. Camera movements follow the characters as they walk or run.

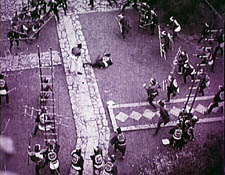

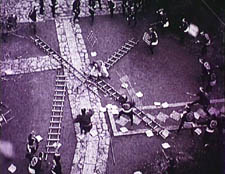

So far, so conventional. But many Japanese filmmakers revised the American approach, turning it into something more expressive and experimental. So, for example, a very steep high angle in Kirarazaka (1925) serves at first to show us that Bando is surrounded by fighters who use ladders to try to trap him. As the scene returns to this framing again and again, it becomes more abstract, with the fallen ladders becoming vectors of a geometrical shot design targeting the hero.

An even more remarkable example is Orochi (1925), a Bando film that survives intact and in fine shape. (Matsuda released it on VHS; I don’t think it’s on DVD yet.) The clip in the 1979 documentary shows one of Orochi‘s most dazzling passages. The hero, played by Bando, fights his way through a town, and, backed up against a wall, he’s trapped on all sides by his opponents. An extreme long-shot (below) shows us the situation, with Bando in the distant center. Many shots break this space down into opposing forces, Bando versus his adversaries, and quite fast cutting shows the men on either side of him.

The stretch that interests me most begins with a shot of Bando looking left.

The director Futagawa Buntaro then breaks the confrontation into separate shots of the other swordsmen. Nothing unusual about that. But most directors would have handled the next few shots of the standoff this way:

Shot of Bando looking left.

Shot of a combatant looking right (implicitly, back at him).

Shot of Bando looking right.

Shot of a combatant looking left (implicitly, back at him).

This way we’d get a clear, simple sense of the fact that he’s surrounded on all sides. Instead, Futagawa follows the shot of Bando looking left with no fewer than twelve very close shots of fighters, all looking rightward. For example:

Then we get six shots of their arms outthrust, as here:

We then get a shot of several men looking straight to the camera, as if they represent the group directly in front of Bando, no longer at the left. Next there appear another ten shots of fighters looking leftward at Bando, all of them quite close to the camera. For example:

In both sets of shots, many images are composed to match each other graphically: the first group of faces tends to place each man on the left frame edge, while the second set puts most men at the far right. The first set of shots develops a pattern, moving from tight facial close-ups to shots of arms and swords thrusting toward Bando. The second set develops toward showing faces that are ever more cut off by the right frame edge.

Add in the fact that all these shots are cut very quickly, ranging from four frames down to one! This is extraordinarily rare in 1925 cinema. (I talk more about how to study such passages in an earlier blog.) Words can’t really convey the way these images clatter against one another. Their percussive speed makes them graspable only as a tense thrust in one direction countered by an equally tense one opposite. Faces pile frantically up against Bando first one one side, then the other. The sense of linear force is strengthened by the shift from the cluster of face shots to that of the arms, with the transition handled in a pair of weird jump cuts along different men’s arms.

The transition from the first shot above to the second creates the impression that the man has jabbed with his spear, while the cut from the second to the third shot eases us to the forearm shots shown earlier.

This bravura passage is triggered by the initial shot of Bando, haggard and shaky. Perhaps the cascade of shots is motivated as subjective, reflecting his exhaustion in the face of entrapment. Just as likely, I’d say, is the fact that Futagawa took a stereotyped situation, the hero surrounded by his adversaries, and looked for a way to make it fresh, to use energetic stylistic innovation to amplify the story point emotionally and perceptually.

Nothing in the sequence violates continuity editing’s basic principles. The shots keep screen direction constant and character position clear. Indeed, the director has understood spatial continuity very deeply: the men to the left of Bando are pushed far to the left side of the frame, the men to the right are squeezed rightward, so that Bando is always implicitly filling the area they’re recoiling from. But what American director would have risked such a bold piece of cutting?

Orochi, let’s remember, was released the same year as Strike and Potemkin. If this passage had been known to the earliest generation of film historians, Japan might well have been greeted as another birthplace of daringly dynamic montage. (2)

There are several other intriguing flourishes in the footage on display in Bantsuma, particularly a scene of Bando dying in a swirl of steam (this entry’s top image). But two points should be clear: this is innovative filmmaking of a high order, and it took place in a shamelessly commercial film industry. Mainstream filmmaking in Japan has been open to stylistic experiment to a degree rare in other popular cinemas. You can trace a line from the 1920s to the present, from the chambara directors through Ozu and Mizoguchi and Kinoshita and Suzuki Seijin right up to Kitano and Miike. Along a parallel path, Hong Kong action cinema pressed filmmakers toward creative renovation of film technique. (3) In this tradition, the action films of Bantsuma and his peers hold an honored place.

The lessons are familiar ones from this blog. Mass-market cinema harbors experimental impulses; creative directors working in well-known genres are often striving to push the limits. By attending to technique, we can discover a dazzling variety in areas of film history not usually considered “artistic.”

PS: Through Digital Meme, Matsuda has also made available a treasury of 55 animated films from the earliest years. The are at work on a DVD of early Mizoguchi films, including a fragment I’m keen to see from Tojin Okichi (Okichi, Mistress of a Foreigner, 1930).

(1) A large set of them has been available for some years on a DVD-ROM, also available from Digital Meme. For useful reviews, go to Midnight Eye and hors champ.

(2) ) I offer several other examples in the essays “Japanese Film Style, 1925-1945” and “A Cinema of Flourishes” in the forthcoming Poetics of Cinema.

(3) I make this argument in Planet Hong Kong and the essays “Aesthetics in Action” and “Richness through Imperfection” in Poetics of Cinema.

Intensified continuity revisited

DB here:

We’re just beginning to understand the history of film forms, but some trends in Hollywood already seem clear. During the late 1910s American filmmakers synthesized an approach to cinematic storytelling that relied on continuity editing, the practice of breaking a scene into matched shots in order to highlight character action and reaction. In the years that followed, this editing strategy became the dominant approach to mass-market filmmaking across the world. Many historians and theorists believed that editing was the essence of cinema itself.

When sound arrived in the late 1920s, the technology was difficult to master and consumed a lot of production time. It would have been easy for American filmmakers to shoot every scene from a single position, but instead they used multiple cameras to cover the action, much as three-camera TV handles sitcoms now. This made filming cumbersome and limited the lighting choices, but filmmakers wanted to preserve the option of cutting to closer views and fresh angles as the scene developed. Continuity editing continued through the 1930s and well beyond, with filmmakers refining it in various ways.

The strategy has proven remarkably robust. Today’s mass-audience films, from all over the world, adhere to the principles and particulars of continuity editing. Not many artistic styles, in any medium, have had such a long run.

These ideas are developed in more detail in things that Kristin and I have written. (1) Most recently my book The Way Hollywood Tells It tries to track shorter-term changes in the continuity style. I found that one handy way to do this was to look at remakes. Remakes allow us to keep story factors somewhat constant and focus on differences in visual technique. Today’s blog looks at parallel scenes from two films, an original and a remake, in order to illustrate what I’ve called “intensified continuity”—the editing style that comes to dominate American films after 1960 or thereabouts.

Dear friend….

In Ernst Lubitsch’s wonderful Shop around the Corner (1940) Kralik (James Stewart) works in a Budapest gift shop with Klara (Margaret Sullivan). They quarrel constantly. But each has an anonymous pen pal, and the relationship is growing into love. Unfortunately, we learn early on, they’re writing to each other.

On the day they’ve agreed to meet face to face, Kralik is fired. He and another salesman Pirovitch (Felix Bressart) trudge to the café where Kralik is to meet his secret friend. Kralik can’t bear to face her now that he has no job, so he wants Pirovitch to deliver a note saying he can’t come. Still, his curiosity makes him ask Pirovitch to look in the window and describe her. Pirovitch tries to soften the blow, but he has to admit that the young woman waiting with a copy of Anna Karenina and a red carnation is Klara.

Angry, Kralik takes back the note and decides to let her wait. But after Pirovitch is gone, he returns to the café and meets her—not divulging his identity, but trying some conciliatory moves.

In the silent era, Lubitsch was one of the greatest exponents of continuity editing. You need only look at The Marriage Circle or Lady Windermere’s Fan to see his quiet virtuosity. (Kristin’s Herr Lubitsch Goes to Hollywood devotes a chapter to his cutting.) But in Shop around the Corner Lubitsch uses only two shots to present Kralik’s and Pirovitch’s conversation outside the café. A fairly distant tracking shot follows the two men to the window, then we get a very lengthy shot of the two men outside. It starts with Kralik instructing Pirovitch to check on what his correspondent looks like.

Another director would have given us point-of-view shots showing what Pirovitch sees, along with his reactions. Instead, Lubitsch keeps the emphasis on Kralik, who’s responding to Pirovitch’s reports. Consequently, Kralik’s reactions aren’t given in cut-in close-ups but rather in the prolonged two shot.

This allows both performers to act with their bodies. Bessart’s shoulders relax, for instance, when he spots Klara, as if he’s slightly recoiling. Stewart’s reactions are more varied; he leans forward eagerly and nods as Pirovitch finds the woman. He slumps, then tugs his hat when Pirovitch mentions Klara.

Kralik looks in to see for himself, and collapses a bit. He eventually relaxes when he wryly accepts the fact that his pen pal is his quarrelsome coworker.

Visually, it’s a simple scene, but it shows the power of the unvarnished two-shot.

After the two men separate, Lubitsch shifts the scene inside and gives us another sustained shot as the anxious Klara talks with a waiter. Instead of crosscutting to Kralik returning outside, Lubitsch creates a humorous shot by letting his head drift into the window behind Klara.

When Kralik goes in to meet Klara, he doesn’t tell her that he’s her pen pal, so narrationally speaking, the knowledge is unbalanced. He and we know more than Klara does, which makes her unhappiness more pathetic. It’s a wonderfully textured scene, partly because we know that each one’s annoyance with the other masks disappointment and anxiety. As the action develops, there’s somewhat more cutting, but even Lubitsch’s closer views often keep both in the frame. He saves his closest shots for the most intense exchange, when Klara mockingly refuses Kralik’s efforts at friendship. The scene will end on a painful note, with each wounding the other with hurtful remarks.

AOL buddies

As you probably know, The Shop around the Corner was remade as You’ve Got Mail. There are some important story differences. The two protagonists have other partners, and Joe Fox owns a bookstore chain that is crushing the children’s bookstore owned by Kathleen Kelly (Meg Ryan). But the parallel scene in You’ve Got Mail is remarkably similar to the one we’ve just been examining.

The sequence starts with Joe and his assistant Kevin (Dave Chappelle) approaching the coffee shop, and Joe is apprehensive—not because like Kralik he’s out of a job but because of the upheaval that meeting his email correspondent could cause in his personal life. Like Kralik, he asks his friend to peer in the window to check her out.

But Nora Ephron handles the scene quite differently than Lubitsch did. She breaks all the dialogue into several shots, mostly favoring one actor (either over-the-shoulder shots or what are called singles). The process starts during the men’s approach to the café.

Once they arrive, the staging stations Joe at the foot of a flight of stairs and Kevin at the top, so a sustained two-shot isn’t really in the cards. The pattern is that Kevin reports what he sees, and in reaction shots we see Joe’s response.

When each man looks inside, unlike Lubitsch Ephron supplies point-of-view shots of Kathleen.

Joe reacts vindictively when he learns his email correspondent is his adversary, and he returns to punish her, but not before we’re taken inside the café and watch Kathleen wait for her correspondent. Even her encounter with another customer, somewhat similar to Klara’s chat with the waiter, is broken into three shots.

When Joe arrives, his conversation with Kathleen is handled in variations of shot-reverse shot, often in fairly tight framings. Again, the closer framings accentuate the bitter insults the characters exchange.

You’ve got cutting

Both scenes run almost exactly the same length: 8:48 in Shop, 8:42 in You’ve Got. But the initial portion, showing the two men on the sidewalk, consumes only two shots in the Lubitsch and 41 shots in the Ephron. That means that Lubitsch’s average shot in the scene runs about 82 seconds, while Ephron’s runs about 4.1 seconds!

The same disparity arises in the section of the scene taking place in the café. In Shop, 14 shots treat the action inside, but in You’ve Got there are 84! Lubitsch’s shots in this portion average about 21 seconds, still very lengthy, while Ephron’s are almost exactly the same as in the earlier portion, coming in at 4.3 seconds. We tend to think that only high-octane action sequences are cut quickly, but today’s dialogue scenes are cut fast too.

In both films, actors’ line readings are very important, but in Shop, the performances include sustained passages of body language. In You’ve Got, actors act mostly with their faces. Whereas Ephron gives us singles from the start (Kevin and Joe’s approach), Lubitsch saves his close shots for the encounter between his squabbling romantic couple. There’s an effect of gradation, with the cutting building the scene visually toward a high point, that isn’t provided by Ephron.

Oddly, the modern film is less subtle than the older one. Lubitsch uses no nondiegetic music in the scene, but Ephron inserts conventionally comic music as Kevin and Joe approach and we get sorrowful music when Kathleen leaves the café in tears. Although many people think that old movies are hammy and overplayed, here it’s just the opposite. Stewart performs subtly, but Hanks, whom many take as today’s Jimmy Stewart, plays broadly, gesturing in extremis and at one point shaking the brownstone’s railing. The Lubitsch scene also makes use of dramatic pauses to a greater extent than Ephron does.

The redundancy is seen as well in Ephron’s reliance on cutting and singles. Nearly every line or reaction in the You’ve Got sequence gets a shot to itself. This isn’t unique to this film; every remake I’ve examined is cut faster than its original. Fast cutting, down to 2 or 3 seconds per shot on average, and a reliance on OTS’s and singles typify today’s intensified brand of continuity.

Silent films were cut quite fast—in America, around five seconds per shot was common—but the arrival of sound slowed down the editing pace. The good people at Cinemetrics are building a database tracking this trend, among others. But since the 1960s, things picked up in American cinema, and today it isn’t uncommon to find films with average shot lengths of 2-4 seconds….and not just action movies. Likewise, such cutting operates in conversation scenes, making it more likely that the shots are singles rather than two-shots or ensemble framings.

This “intensification” of traditional continuity tactics, I’d argue, dominates mainstream moviemaking today, and not just in the US. Such cutting can sometimes be found in the 1930s and 1940s too, but then it was one possibility within a broader range. The Lubitsch example adheres to the principles of continuity editing, but it allows for more variety of camera distance and pacing.

I don’t denounce intensified continuity as such; some films, most recently David Fincher’s fine Zodiac, make intelligent use of it. Still, with this as the dominant approach, the director’s range of choice has narrowed. When contemporary directors lengthen a take, it’s usually to create a virtuoso traveling shot. A simple framing like the one outside the cafe in Shop is very unusual nowadays. The sustained two shot is practically an endangered species.

Why? What led to these changes between the studio era and contemporary cinema? A cynic would say that, contrary to Steven Johnson, audiences have gotten dumber and need more emphasis on character action and reaction to follow what’s going on. But in The Way Hollywood Tells It I suggest that there are many factors at work in this stylistic change. The book also provides more details of other techniques characteristic of today’s intensified continuity.

(1) In particular Kristin’s Breaking the Glass Armor: Neoformalist Film Analysis, our sections of The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960 (written with Janet Staiger), and our Film Art: An Introduction.

Funny framings

DB asks: Can a film shot be amusing in itself?

Of course a shot can show us a gag that’s funny. If Jerry Lewis or Adam Sandler is going to fall off a ladder into a Dumpster, we want to see everything clearly. Here the framing can be modestly functional. But can the very choice of lens, angle, scale, or composition play a stronger role? Can camerawork itself provide the gag?

Barry Sonnenfeld, cinematographer for the Coens and now a prominent director, thinks so. He’s remarked that an extreme wide-angle lens is inherently funny. In the commentary for the DVD of RV, he explains, “You just put a big 21mm lens really close to [Will Arnett’s] face and you get comedy without him having to do anything.” I don’t have an RV frame handy, but here’s an example from Big Trouble, with both the wide lens and the low-angle creating the sort of grotesque disproportions that Sonnenfeld finds funny.

Sonnenfeld got this idea, he claims, by working on the Coens’ early films, which used wide-angle shots for cartoonish exaggeration. In Raising Arizona, the angle and lens length make the wandering baby loom; we’re not used to seeing an infant rampant.

But the Coens had a broader approach to funny framings than Sonnenfeld acknowledges. For instance, they created humor by means of geometrical tableaus. In H. I.’s parole hearing in Raising Arizona, an absurd solemnity is set up by the symmetrical layout of actors. At the apex of the triangle, a portrait of Senator Barry Goldwater blesses the occasion.

Even more memorable is the forward tracking shot down the bar top in Blood Simple. The camera, encountering a drunk sprawled in its path, simply crawls over him.

The silent comedians knew how to use camera position to build up their gags. Long ago Rudolf Arnheim praised the opening scene of Chaplin’s The Immigrant. As a ship rocks treacherously, we see Charlie from the rear heaving and kicking on the railing. As Arnheim puts it, “Everyone thinks the poor devil is paying his toll to the sea.” (1)

But then Charlie turns toward the camera to reveal he’s been struggling to reel in a fish.

Here the framing creates the gag by what it doesn’t show. “The element of surprise,” Arnheim notes, “exists only when the scene is watched from one particular position.” The camera setup also makes an expressive analogy; we probably never noticed the similarity between vomiting and wrestling a fish.

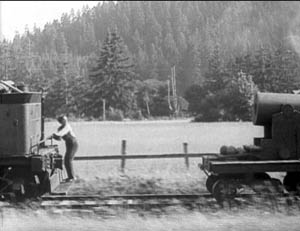

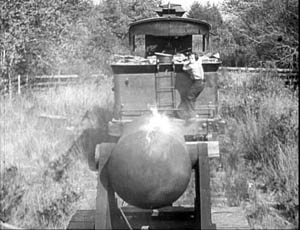

One of my favorite comic framings occurs in The General. Buster’s train is hurtling along, and a cannon on one car is suddenly trained on him. The first shot gives us the situation with maximum clarity, in a profiled shot. But then Keaton cuts to another angle, showing the cannon in the foreground and Buster trying to escape it.

Nothing much has changed in the scene’s action, just the camera setup. But now we get to watch the cannon draw a bead on Buster. Audiences invariably laugh at this shooting-gallery image.

Jacques Tati is in many ways the modern heir of Keaton, and humor in his sequences often stems simply from a juxtaposition of elements in a single frame. An older man ogling a pretty woman on the beach is funny in a standard way, but in M. Hulot’s Holiday, we get more.

No words are spoken, but Tati’s staging and framing juxtapose the very different bodies in telling ways. We’re invited to note the difference between age and youth, paunchiness and health, passing yearning and its likelihood of fulfillment.

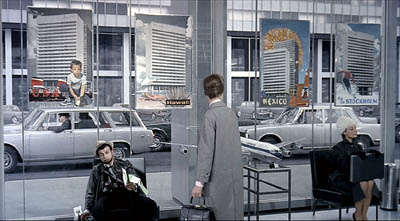

Play Time, Tati’s masterpiece and one of the greatest films ever made, offers an abundance of subtly comic framings. The shot below promotes the film’s theme that modern architecture has homogenized the world. The posters present the same building in different locales, with only stereotyped add-ons to distinguish the US, Hawaii, Mexico, and Stockholm. As one of the ladies on Barbara’s tour says, “I feel at home everywhere I go.”

Again, though, a juxtaposition adds to the humor. Throughout Play Time, Tati suggests the disparity between the joy of travel as promoted by our culture and the stress of hustling from place to place. The promise of the posters is undercut by the dazed traveler who’s flopped underneath them, clutching maps and flightplans. And he in turn contrasts with the no-nonsense businesswoman on the far right.

Tati can create comedy by the exact placement of the camera; a foot to the left or right and the gag would vanish. In the image at the start of this entry, the waiter is pouring champagne, but he seems to be watering the ladies’ flowery hats, which mask their champagne glasses. The same sort of exactitude of placement occurs in a shot we use as an illustration in Film Art (p. 195). M. Hulot is leaving an office building when it’s closing. As a guard locks down a doorway, his cap falls off and Hulot is startled: the guard seems to have grown horns.

Can we find funny framings in current films? Yes! I was prompted to write this blog while rewatching Shaun of the Dead. Zombies have overrun London, and two groups of human survivors meet. Shaun is leading one, Yvonne is leading the other. Instead of being presented as a mingling of the two groups, the scene plays out along two lines of people. Have a look.

The gag’s premise is that each survivor has a counterpart in the other line. There are two posers in brown leather jackets, two can-do girls, two matrons, and two distracted videogame geeks. I wonder how many first-time viewers catch this? (Kristin did, I didn’t.)

These mirror-image depth shots set up the real gag, which pays off in another clever composition. When the two groups set off on separate paths, each member passes and smiles awkwardly at her/his lookalike, while the framing underscores their likenesses.

As they walk through the frames, the similarities increase.

The framing makes a clever point about conformity and social stereotypes. Ending the procession with the two gamers, oblivious to the danger and to one another, tops the topper, as gag writers would say.

Tati would have loved these shots.

Of course I’ve simplified things for the sake of making my point. It’s not that the camera is somehow capturing a free-standing event by selecting the most amusing view. In all these examples, the staging is calculated to match the camera position. Staging, like camerawork and other film techniques, creates filmic narration. I’m only suggesting that in these scenes, the staging wouldn’t work on its own to create humor, nor would a simply functional framing. Choices of lens, camera position, and the like seem to be critical in making the gags work.

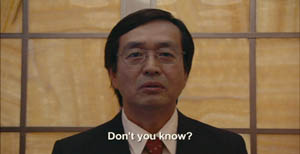

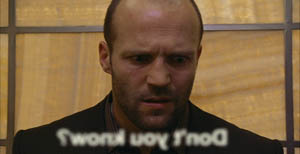

Finally, a borderline case that intrigues me. In last year’s Crank, our hero is in overdrive thanks to a constant intake of drugs. Stepping into an elevator, he faces a man who starts speaking Japanese. Naturally, his line is subtitled.

But then we get this:

The idea of the head-on reverse angle is carried to comic extremes by reversing the subtitle as well (and blurring it to reaffirm the hero’s muzzy mental state).

I think that aspiring filmmakers can learn a lot from this tradition. Our films need more pictorial creativity, which often doesn’t require fancy CGI. Stylistic handling can add fresh layers to a basic story situation, and astute filmmakers can be alert to the possibilities of comic compositions and funny framings.

(1) Rudolf Arnheim, Film as Art (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1957), p. 36.

PS 4 May: Owen Williams writes to point out that the gag in Crank depends not just on a reverse framing but a play on the idea of lens focus. “The subtitle is fuzzy because it’s supposed to exist in real space (at least in this character’s head), with the letters hanging in mid-air in front of the Japanese man. Therefore in the reverse angle they appear out of focus (fuzzy) because they are closer to the camera. It’s a great gag.” Thanks, Owen.

PPS 8 May: I’ve gotten a lot of correspondence about this blog entry. Here are some nifty supplements:

Kent Jones was reminded of the shot in High Anxiety in which the camera moves to a picture window, with people dining behind it, and then crashes through the glass.

Sam Adams recalled a shot in Killer of Sheep that had something of the same effect, showing men trying to load a car engine onto the bed of a pickup truck. But the context isn’t itself comic. Sam reflects: “Based on the examples you choose, it seems that ‘comic framing’ invariably involves a level of self-consciousness, a feeling that the audience is being deliberately toyed with by the figure behind the camera. We get a sense that the scene has been staged for our amusement, rather than feeling that we must identify emotionally with whatever the characters are going through (which even in comedies is often quite sad).”

Stew Fyfe found a host of in-jokes in the Shaun of the Dead shots:

“Viewers of British television might notice an extra parallel between the shots. The actors playing each of the group leaders, Simon Pegg (Shaun) and Jessica Stevenson (Yvonne), were the leads in the sitcom Spaced (also directed by Edgar Wright, the TV predecessor to Shaun). Also split between the two groups are Lucy Davis (Shaun’s Group, hat) and Tim Freeman (Yvonne’s group, second in line), from original The Office and Dylan Moran (Shaun’s group, glasses) and Tamsin Greig (Yvonne’s group, hat), the leads of the sitcom Black Book. Yvonne’s mum (second matron) is played by Julie Deakin, who played the drunk and desperately lonely/horny landlady in Spaced.”

Thanks also to Bryan Wolf for a note on the same subject.

Finally, this from Jeremy Butler:

“I like your example from The General, but my favorite example of comic framing from Keaton’s work (and one I use in class to illustrate how he was more “cinematic” than Chaplin) is in Sherlock, Jr. Buster runs along the top of a freight train, and is then flushed to the tracks by a spout from a water tank. What makes it funny, I’d suggest, is the choice to frame it from the side, at a right angle to the tracks (much like the first General frame in your example). It minimizes the size of Buster’s body and contrasts him with the size of the train cars. Plus, it emphasizes the movements in opposite directions of his body and the train.

All these elements make it visually funny in a way that would not be apparent if it were filmed from an oblique angle or from behind the train.

But then, maybe I just like to show it because it’s the scene in which Buster literally broke his neck–which he didn’t realize until decades later when being x-rayed for something completely different!”

Thanks to everyone who wrote in with comments and who linked to this entry.

Charlie, meet Kentaro

DB here:

Echoing an earlier virtual roundtable on this blog, I want to write about my two favorite B film series, now available in handsome DVD boxed sets. Both series were mounted at 20th Century-Fox, both were adapted from genre fiction, and both seem very much of their time: lots of exotic Orientalia, and probably too many middle-aged men in tiny mustaches and broad fedoras. But to my mind these films offer brisk, unpretentious entertainment, solidly crafted and surprisingly subtle. They also allow us to trace some changes in the ways movies were made across the 1930s.

There’s another reason for this blog. Tim Onosko, a friend of Kristin’s and mine, recently died after a battle with pancreatic cancer. Tim was an extraordinary figure, as you can find here. He was central to Madison film culture for forty years, and in his various creative activities, he shaped everything from The Velvet Light Trap to Tokyo Disneyland. He and his wife Beth also made a documentary, Lost Vegas: The Lounge Era. Tim and I enjoyed talking about the two series I’ll be mentioning. He loved these films, as he loved all films and popular culture generally, with a sharp-eyed dedication. So this is a small effort at an homage to Tim.

The Hawaiian and the Japanese

Charlie Chan, a Hawaiian police inspector of Chinese ancestry, became famous in a series of six novels by Earl Derr Biggers, from The House without a Key (1925) to The Keeper of the Keys (1932). Chan novels were brought to the screen at the end of the 1920s by Pathé and Universal, but for Behind That Curtain (1929) Fox took over the franchise. Warner Oland, a Swedish-born actor who had often played Asians, settled into the lead role in Charlie Chan Carries On (1931). He played Chan up through Charlie Chan at Monte Carlo (1937), then fled Hollywood under peculiar circumstances and went to Sweden, where he died soon afterward.

The Mr. Moto films overlapped with the Oland cycle. John P. Marquand introduced Moto in the novel No Hero (1935) and made him more central to four novels that followed. Again, Fox bought the rights and launched the film series with Thank You, Mr. Moto (1937). It starred Peter Lorre as the mysterious Japanese, and I think it’s fair to say that the role made him a Hollywood star. The series ran for eight installments, ending in 1939 with Mr. Moto Takes a Vacation.

The Mr. Moto films overlapped with the Oland cycle. John P. Marquand introduced Moto in the novel No Hero (1935) and made him more central to four novels that followed. Again, Fox bought the rights and launched the film series with Thank You, Mr. Moto (1937). It starred Peter Lorre as the mysterious Japanese, and I think it’s fair to say that the role made him a Hollywood star. The series ran for eight installments, ending in 1939 with Mr. Moto Takes a Vacation.

Each series echoed its mate. Tim claimed that in an early Chan, a character is reading a Moto story in the Saturday Evening Post, though I’ve never found that scene. When Charlie’s Number One Son turns up to help Moto in Mr. Moto’s Gamble (1938) it’s revealed that Charlie and Moto are old friends. There’s a more elegiac moment in Mr. Moto’s Last Warning (1939) when a theatre displays a poster for the Chan series—perhaps as well serving as an homage to the recently deceased Warner Oland. Despite Oland’s death, the Chan series continued until 1949, with Sidney Toler in the role, but with Lorre’s departure the Moto films ceased.

Having a Caucasian actor play an Asian protagonist was common at the time. Today, it seems condescending or worse, but we should recognize that the films featured Asian actors as well, often in significant roles. The most visible example is Keye Luke as Charlie’s highly Americanized son. Forever blurting out “Gosh, Pop!” Luke is a lively and likable presence.

Just as important, the portrayal of the detectives is remarkably free of racism. Charlie and Moto are clearly the quickest-witted characters, and both prove resourceful in all kinds of ways. Moto’s judo subdues thugs twice his size, and Charlie is up-to-date in the new technologies of detection.

The scripts go out of their way to show both men skilfully handling the prejudice they encounter. In Charlie Chan at the Opera (1936), a blatantly racist cop (William Demarest) who calls Charlie “Chop Suey” is mocked incessantly by everyone, most gently by Charlie. Moto excels at pretending to be the stereotypical Asian (“Ah, so!” “Suiting you?”). And both our protagonists are sympathetic to others who are in minorities. Charlie is notably unwilling to participate in guying black servants as the whites do, and Charlie Chan at the Circus (1936) shows his keen sympathy with the “freaks,” treating them with quiet courtesy. The Moto series presents a Japanese who doesn’t seem to share his country’s goal of ruling Asia. In Thank You, Mr. Moto, he enjoys a respectful friendship with a Chinese family of declining fortunes.

The Chan series features straightforward detection. A murder is committed, and either Charlie is in the vicinity or the police ask for his help. A young and innocent couple is involved, adding pressure for Charlie to solve the case. Another murder is likely to take place, and a few attempts are made on Charlie’s life before he comes to the solution. In traditional fashion he tends to assemble all the suspects at the climax before exposing the guilty party.

The Chan series features straightforward detection. A murder is committed, and either Charlie is in the vicinity or the police ask for his help. A young and innocent couple is involved, adding pressure for Charlie to solve the case. Another murder is likely to take place, and a few attempts are made on Charlie’s life before he comes to the solution. In traditional fashion he tends to assemble all the suspects at the climax before exposing the guilty party.

The Moto films aren’t as concerned with puzzles. Like the novels, they’re tales of international intrigue, involving smuggling, theft of archaeological treasures, and the like. There’s more violence and physical action, with shootouts and last-minute rescues. Moto Kentaro (his given name is visible only on his identity card) is a more shadowy presence than Charlie, often working under vague auspices. He’s either an agent of Interpol, a functionary of the Japanese government, or an exporter who takes up intrigue as a hobby. (1) In Mr. Moto’s Gamble, arguably the best of the series, he engages in old-fashioned detection involving murder during a boxing match. Unsurprisingly, the film was originally planned as a Chan vehicle, and it even includes Number One Son as Moto’s sidekick.

The Moto films aren’t as concerned with puzzles. Like the novels, they’re tales of international intrigue, involving smuggling, theft of archaeological treasures, and the like. There’s more violence and physical action, with shootouts and last-minute rescues. Moto Kentaro (his given name is visible only on his identity card) is a more shadowy presence than Charlie, often working under vague auspices. He’s either an agent of Interpol, a functionary of the Japanese government, or an exporter who takes up intrigue as a hobby. (1) In Mr. Moto’s Gamble, arguably the best of the series, he engages in old-fashioned detection involving murder during a boxing match. Unsurprisingly, the film was originally planned as a Chan vehicle, and it even includes Number One Son as Moto’s sidekick.

Looks and looking

We can learn a lot by studying the two main actors’ performance styles. The plump Oland plays Chan as stolid but not ponderous. He floats across a room and gravely circulates among suspects, giving the films their deliberate pacing. Oland’s drawn-out delivery and pauses were due, people say, to his acute alcoholism, but he never seems to be struggling to find his lines. Charlie is at pains to be unobtrusive, modest, and tactful; his characteristic gesture is a simple one, letting the fingertips of one hand grasp one finger of the other.

He is a loving father, doting on his many children (all in tow in Charlie Chan at the Circus). Although Number One Son may exasperate him, you would go far in films to find as warm a portrayal of a father’s affectionate efforts to curb an impulsive boy. See Charlie Chan at the Olympics (1937) for the casual byplay between Charlie and Lee, now an art major and a member of the swimming team. Lee’s bubbling energy gives Charlie’s imperturbability even greater gravitas.

The short and slim Lorre plays Moto as a suave man-about-Asia, hand thrust casually into his trouser pocket. Moto is an art connoisseur, a graduate of Stanford (class of ‘21), and a master of many languages. Lorre, so easily caricatured at the time and now, hit on a brilliant idea: He didn’t give Moto stereotyped tricks of pronunciation. Unlike Oland, he didn’t usually drop articles or compress syntax.(2) Lorre just played the part in his lightly accented English, as he would in The Maltese Falcon and Casablanca. He added a soft-spoken delivery, a modest smile, and a trick he may have picked up from Marlene Dietrich–ending his sentences with a slight upward inflection, turning every statement into a polite question.

Reaction shots of suspects are a convention of these movies, but after several cuts show us everybody looking shifty, the reverse shots of our heroes show us that they miss none of this byplay. (3) Charlie is alert, but he hides his penetrating view behind a bland courtesy. As Moto, Lorre presents a more aggressive intelligence. Peering through round spectacles, those bug eyes, panic-stricken in M, can now become pensive or bore into a suspect. Charlie needs the force of law, but Moto, who usually acts alone, is dangerous by himself, and Lorre’s horror-show pedigree serves him well in giving his hero’s stare a sinister edge.

Listening and looking

You can argue that Oland and Lorre, coming to their parts only a few years after sound had arrived, helped Hollywood develop a wider array of acting styles. We historians of Hollywood have rightly praised gabby comedies like Twentieth Century (1934) and It Happened One Night (1934) for finding a performance technique suited to sound films, particularly in the wake of technical improvements in acoustic recording. If movies had to talk, we think, they should really talk, fast and hard and heedlessly. In this church our Book of Revelations is His Girl Friday (1940).

Lorre and Oland, like Karloff and Lugosi, remind us of the virtues of being gentle, spacious, and deliberate. This isn’t a reversion to those hesitant, strangled mumblings of the earliest talkies. Rather, the movies’ plots surround our Asians with rapid-fire duels of cops and reporters, snapping out “Say!” and “Hiya, sister!” and “Watch it, wise guy!” and “Don’t be a sap!” Against clattering percussion Moto and Charlie deliver a melodic purr.

Some people still believe that in Citizen Kane Welles and Gregg Toland introduced American film to steep low angles, tight depth compositions, and noirish lighting. In The Classical Hollywood Cinema, I’ve argued that the Gothic, somewhat cartoonish look of Kane synthesized and amplified trends that were emerging during the 1930s. The Chan and Moto films are wonderful places to study these visual schemas.

E

E

In Charlie Chan in Egypt (1935, above), cinematographer Charles G. Clarke (whom Kristin and I interviewed for the Hollywood book) offers flashy depth and silhouette effects, and nearly all the Chan films have moments of clever staging. Charlie Chan at the Opera, above, is particularly engrossing, with its huge set (recycled from the A-picture Café Metropole, 1937). The same film, incidentally, contains scenes of a fictitious opera, Carnival, composed by Oscar Levant. This was an ambitious gesture for a B film and looks forward to Bernard Herrman’s Salammbo sequences of Kane.

The Motos are even more remarkable. You want wild angles? Venetian-blind shadows? Telltale reflections in eyeglasses? Swishing bead curtains? Twisted expressionist décor? You’ve come to the right place.

Some late thirties Fox sets seem to have been stored in Caligari’s Cabinet. Watching these films, it becomes clear that Kane applied the moody technique of crime and horror films to ambitious drama. One bold setup in Mr. Moto’s Gamble looks like a dry run for a Toland big-foreground composition (done here, as often in Kane, through special-effects). I like this shot so much I used it in Figures Traced in Light.

Yet all this creativity took place within severe constaints. These were B pictures, running under seventy minutes and shot in a month or so. Three or four would be released each year. They shamelessly used stock footage, leftover sets, and the same players in different roles from film to film. (Watch for Ray Milland, Ward Bond, and others on the way up.) The boys in the Fox cutting room seem to have enforced a remarkable uniformity: most of the Chans in these DVD sets, regardless of director, contain between 600 and 660 shots, while the faster-paced Motos average between four and six seconds per shot. The actors created hurdles too. Oland sank even further into drinking while the high-strung Lorre was addicted to morphine and periodically retired to sanitariums to recover. Those were the days; rehab wasn’t yet a matter for infotainment.

The Fox DVD boxes are model releases. The prints are well-restored (better on the second sets than the first) and filled with astute, informative supplements. We get a lot of detail about production matters, including why Oland left Hollywood. There is welcome biographical background on master minds like Sol Wurtzel and Norman Foster. I still want to know more about James Tinling, though; his direction of Mr. Moto’s Gamble and Charlie Chan in Shanghai (1935) belies his reputation as a hack.

“The cinema is not dangerous,” Moto reassures the Siamese tribesmen about to be filmed in Mr. Moto Takes a Chance (1938). Immediately, the woman who’s being filmed dies. The adventure begins. Who can resist movies like these? They have kept me happy since my childhood, when I watched them on Sunday afternoon TV. They can keep your children, and you, happy too.

For some good reading, see John Tuska, The Detective in Hollywood (Doubleday, 1978); Charles Mitchell, A Guide to Charlie Chan Films (Greenwood, 1999); Howard M. Berlin, The Complete Mr. Moto Film Phile: A Casebook (Wildside, 2005); and Stephen Youngkin, The Lost One: A Life of Peter Lorre (University Press of Kentucky, 2005).

For more on Charlie, click here. Charles Mitchell has a nice wrapup on Kentaro here.

(1) The involvement of an innocent romantic couple was a convention of slick-magazine fiction of the day (both the Chan and Moto novels were serialized in the Saturday Evening Post), and it recurs throughout mainstream detective fiction of the 1930s. Most writers of the period wrestled with the problem of how to make the couple interesting. See Carter Dickson/ John Dickson Carr’s short story, “The House in Goblin Wood,” for a brilliant handling of the device.

(2) As many commentators have noted, Charlie doesn’t speak pidgin English; he seems to be mentally translating. Interestingly, the generation gap is apparent here too, since Number One Son speaks peppy and perfect American slang.

(3) One hyperclever moment in Mr. Moto’s Gamble gives us the usual rapid-fire array of single shots of discomfited suspects but neglects to show us the real culprit.