Archive for the 'Film technique: Editing' Category

Trims and outtakes

Some jottings from DB:

Continuity Boy meets Badgers

Tim Smith, who studies how we perceive film, recently visited our department at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. His talk was splendid.

Tim Smith, who studies how we perceive film, recently visited our department at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. His talk was splendid.

Tim studies the ways we scan shots and shift our attention across cuts. His talk was illustrated with film sequences showing little yellow dots swarming around the frame; these indicate the points in the image where his subjects’ glances landed. Tim shows pretty conclusively that there’s a consensus about where viewers look during a shot (faces, movement, the center of the frame) and that classical continuity cuts can push our attention to and fro with remarkable facility. One of the most surprising findings was that viewers are often starting to shift their attention to a new frame area just before the cut comes. Why? Tim has some intriguing suggestions.

Tim also showed some remarkable effects of what I’ve called “intensified continuity,” the fast-cut close-ups that characterize so much current cinema. Because these passages leave no time for visual exploration, viewers seem to revert to a cursory test for the shot’s basic point, usually at the center of the frame. Tim’s examples from Requiem for a Dream were fascinating, showing how real viewers are playing catchup in very fast-cut sequences.

This is rich and promising research, showing once more that Leonardo da Vinci, Eisenstein, and a few others were right to think that many creative choices in the arts can be studied with the tools of science. It also shows that filmmakers, like other artists, are seat-of-the-pants psychologists, achieving complex effects through decisions that “feel right” and that they have no need to explain theoretically. That’s our job.

For Tim’s narrative of his visit, and a lot more about his research program, go here. For something not quite completely different, about eye-tracking, print ads, and crotches, go here.

Six more from RKO

The enterprising folks at Turner Classic Movies have discovered six RKO films that have been missing for many years. It’s a harvest of 1930s titles, promising some intriguing situations (e. g., Ginger Rogers as a telemarketer) and carrying the names of directors like William Wellman, John Cromwell, and Garson Kanin.

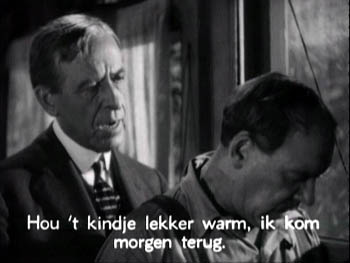

A Man to Remember (1938; at the top of this page), Kanin’s first film, is the only one of the batch I’ve seen so far. One of the New York Times‘ ten best films of 1938, it went virtually unseen until a print surfaced at the Netherlands Filmmuseum in 2000. A Man to Remember is a portrait of a small-town doctor who tends to the poor and lets others, chiefly a cadre of corrupt businessmen, take credit for his good works.

It could all be mawkish, but Edward Ellis plays the doctor as a testy guy who levels with his patients and wins the town’s respect through quiet cussedness. The performance echoes Ellis’ crabby but likable inventor in The Thin Man (1934). Dalton Trumbo’s script has an intriguing flashback structure, less bold than in The Power and the Glory (1933) but still ambitious for a B project.

The six RKO discoveries are screening on April 4th as an ensemble, then they’re scattered through the rest of the month. All should be worth checking out. Once more TCM proves itself the film-lover’s channel of first choice.

Bambi or kitty?

Two recent books support the claim that New Hollywood, or New New Hollywood, is at bottom in debt to old Hollywood. (The full case is presented in The Way Hollywood Tells It and Kristin’s Storytelling in the New Hollywood.)

David Mamet’s Bambi vs. Godzilla: On the Nature, Purpose, and Practice of the Movie Business (Pantheon) is as pungent and eccentric as you’d expect, but also deeply traditional in its storytelling advice. A movie’s characters must have goals, and over the course of three acts they achieve them, or definitively don’t. The Lady Eve is Mamet’s model of this construction. Furthermore, three questions structure every scene: Who wants what from whom? What happens if they don’t get it? Why now? In wide-ranging essays, Mamet pays tribute to the craftsmanship of below-the-line talent and celebrates movies as various as The Diary of Anne Frank and I’ll Sleep When I’m Dead (whose protagonist is remarkable for “his personification of enigma”).

David Mamet’s Bambi vs. Godzilla: On the Nature, Purpose, and Practice of the Movie Business (Pantheon) is as pungent and eccentric as you’d expect, but also deeply traditional in its storytelling advice. A movie’s characters must have goals, and over the course of three acts they achieve them, or definitively don’t. The Lady Eve is Mamet’s model of this construction. Furthermore, three questions structure every scene: Who wants what from whom? What happens if they don’t get it? Why now? In wide-ranging essays, Mamet pays tribute to the craftsmanship of below-the-line talent and celebrates movies as various as The Diary of Anne Frank and I’ll Sleep When I’m Dead (whose protagonist is remarkable for “his personification of enigma”).

Mamet adds a fair amount on editing, supplementing the remarks in his Pudovkin-flavored On Directing Film. For instance: “At the end of the take, in a close-up or one-shot, have the speaker look left, right, up, and down. Why? Because you might just find you can get out of the scene if you can have the speaker throw the focus. To what? To an actor or insert to be shot later, or to be found in (stolen from) another scene. It’s free. Shoot it, ’cause you just might need it.”

Mamet bemoans the script reader, whose motto must be Conform or Die. By contrast, Blake Snyder makes conformity seem fun and–well, if not easy, at least attainable. His Save the Cat! The Last Book on Screenwriting You’ll Ever Need (Michael Wiese Productions) bulges with formulas, recipes, and gimmicks.

Like Kristin and me, Snyder treats the Second Act as really two sections, broken by a midpoint. But for him three acts are just the beginning. He demands that there be an Opening Image (on script p. 1), Theme Stated (p. 5), Catalyst (p. 12) and on and on until we get the Finale (pp. 85-110) and the Final Image (p. 110). This is the most strictly laid-out cadence I’ve seen; it would be fun to see if actual scripts adhere to it. In addition, you get catchy tips like Save the Cat! (show the protagonist doing something likable early on) and the Pope in the Pool (burying exposition). Snyder includes a list of the most common screenplay errors. An enjoyable read with some hints about construction I hadn’t encountered before.

Like Kristin and me, Snyder treats the Second Act as really two sections, broken by a midpoint. But for him three acts are just the beginning. He demands that there be an Opening Image (on script p. 1), Theme Stated (p. 5), Catalyst (p. 12) and on and on until we get the Finale (pp. 85-110) and the Final Image (p. 110). This is the most strictly laid-out cadence I’ve seen; it would be fun to see if actual scripts adhere to it. In addition, you get catchy tips like Save the Cat! (show the protagonist doing something likable early on) and the Pope in the Pool (burying exposition). Snyder includes a list of the most common screenplay errors. An enjoyable read with some hints about construction I hadn’t encountered before.

Speaking of screenplays….

J. J. Murphy is an old friend (we went to grad school with him in 1971) and colleague (he teaches in our department). Renowned as an experimental filmmaker, he has turned his attention to American indie cinema. His new book Me and You and Memento and Fargo: How Independent Screenplays Work offers an in-depth analysis of several recent films. J. J. shows how they obey mainstream conventions of construction while still innovating in other ways. I especially like his discussions of Hartley’s Trust, Korine’s Gummo, and Lynch’s Mulholland Dr. I think it’s a book that everyone interested in current American cinema would find stimulating.

You can find out more about it, and read an excerpt, here. Congratulations, J. J.!

Walk the talk

The Magnificent Ambersons.

“It’s only history,” Jack Valenti is reported to have said when allowing scholars access to MPAA files. (1) After studying Hollywood for over thirty years, I should be used to the ways in which trade journalists (and some critics) forget or ignore historical precedents in moviemaking. But I still get bug-eyed when I encounter something like the Variety piece on TV director Tommy Schlamme (Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip).

The subhead tells us that this DGA nominee is known for his “hallway shots.” That gets my interest.

I lose interest fast. The writer tells us that Schlamme

developed the “walk and talk” on Sports Night and then mastered it on The West Wing.

The shot—which features two or more actors moving from one location to another on the set, often from one office to another via a hallway—has become a Schlamme signature.

The first sentence could be read as saying that Schlamme invented the walk-and-talk. Since I spent a little time studying this technique in The Way Hollywood Tells It, my inner film historian cries out, Aarrgh. Long before Sports Night (aired 1998-2000) and The West Wing (1999-2006), movies were developing such bravura shots.

The oblique view

In the prototypical walk-and-talk, two or more characters advance, and the camera tracks along, keeping them centered as they move through the environment. Such shots are quite uncommon in the silent cinema, but they emerge in 1930s films from many countries.

They were truly “signature shots” for Max Ophuls and the lesser-known Erik Charell. In Charell’s captivating The Congress Dances (1931) Lillian Harvey sings while a carriage takes her through an entire town and into the country, all in flowing tracking shots. Call it a ride-and-sing.

If that’s not as pure an instance as you’d like, we can find nice ones during a street scene of The Thin Man (1934). A more somber example occurs in Mizoguchi Kenji’s Story of the Last Chrysanthemums (1939), with the camera in a river bed angled upward at the couple it follows.

Usually such traveling shots from the 1930s and 1940s are shot obliquely to the actors. That is, the performers are seen in a ¾ view, and they walk along a diagonal path with respect to the frame edges; the camera moves on a similar trajectory. Sound cameras were mounted on dollies that usually ran on tracks. Framing the actors head-on raised problems with this gear. Performers couldn’t walk smoothly if they were stepping within rails, and there was a risk that the rails in the distance might appear in the frame. It was simpler to set the camera at an oblique angle so that actors could walk unimpeded and the tracks wouldn’t be seen. Directors continued to use this framing into the 1950s, as in Welles’ Othello (1952) and Fuller’s Forty Guns (1957). Both are unusually long takes; in the second, poor Gene Barry seems to be panting to keep up with the other men.

Back off

Today’s walk-and-talk is more likely to be a head-on framing, with the camera retreating from the actors. (More rarely, it dogs them from behind.) With a retreating Steadicam, you don’t have to worry about glimpsing the ground or floor behind the actors, in the distance, since there are no track rails to be exposed. Again, though, we have some precedents, most famously the splendid camera movements, evidently executed with a crane, in the ball sequences of The Magnificent Ambersons (1942), when George and Lucy stroll through the party.

When location shooting became more common in the 1940s and 1950s, cameras could be supported on more versatile dollies that didn’t require track rails, and these reverse-tracking shots become a bit more common. Kubrick, highly influenced by Welles and Ophuls, captured his officers striding through the trenches of Paths of Glory (1957). Vincent LoBrutto’s information-packed book (2) tells us that Kubrick’s dolly rolled backward on the planks that the actors walked on (authentic details, as boards were indeed used in the muddy trenches). Godard’s long traveling through the office lobby in Breathless (1960) was shot from a wheelchair.

Such head-on (and tails-on) shots can be found in several films well into the 1970s, as in Arthur Hiller’s The Hospital (1970). In fact, hospitals, police stations, and other sprawling institutional spaces seem to invite this approach.

By the 1980s, these shots proliferate in American films largely because the Steadicam makes them easy. One famous example is De Palma’s Bonfire of the Vanities (1990), which follows the drunken Peter Fallow through a hotel as he picks up and drops off many other characters.

Today such shots are very common in both high- and low-budget films. Schlamme’s “signature” device seems to be in pretty wide circulation. At best it’s a convention, at worst a cliché.

They’re called actors; let them perform action

I argue in The Way Hollywood Tells It that walk-and-talk is one of two principal staging techniques of contemporary Hollywood. The other, usually called stand-and-deliver, plants the characters facing one another and simply cuts from one to the other. The scene is built primarily out of singles (shots of only one actor) or over-the-shoulder framings. Here’s a typically static dialogue scene from The Matrix Revolutions (2003).

Both stand-and-deliver and walk-and-talk began in the studio era, decades ago, but then there were other options as well. Directors cultivated smooth, unobtrusive blocking tactics that moved characters in ways that reflected the developing scene. The actors had to perform with their whole bodies, and bits of business motivated them to circulate through the setting and turn toward or away from the camera. One example given earlier on this blog is from Mildred Pierce; here’s another, from the program picture Homicide (1949).

Detective Michael Landers has a hunch that the purported suicide of a former sailor is really murder. He has to persuade Captain Mooney to let him pursue some leads out of his jurisdiction. Today this might be played out in a stand-and-deliver session, with both men seated and shot/ reverse-shot cutting carrying the scene. But the director Felix Jacoves decides to let his actors earn their money through ensemble staging, not merely line readings. Here are just three shots from the middle of the scene that illustrate my point.

Landers stands at Mooney’s desk and gets a refusal. As he turns away to the left, Mooney walks to the rear files to put the papers away.

As they’re retreating to the opposite ends of the screen, Landers’ partner Boylan, who’s been offscreen for this phase of the scene, strides into the center and pauses at the door. The result of this choreography is both a balanced three-point composition and a chance to let us observe Boylan’s skeptical reaction to Landers’ next plea.

The camera tracks in as Landers approaches Mooney. Boylan shifts closer as well. What seems somewhat stagy as we analyze it doesn’t look obtrusive on the screen, because we’re following Landers’ arguments and watching the older men’s reactions. The closer framing and the position of the men, now face to face rather than separated by a desk, raises the dramatic pressure. As Landers pauses, Mooney folds his arms—a simple piece of body language that lets us know he’s still resisting.

Now a cut to Mooney, in an OTS framing, stresses his continued resistance as he tells Landers off, and a reverse shot gives Landers’ angry reaction.

Interrupting the sustained take, the shot/ reverse shot cuts have gained more emphasis than if they were part of a string of OTS shots. Jacoves has saved his cuts and closer views for a moment that raises the stakes visually as well as dramatically.

I’m not claiming that this is a brilliant stretch of cinema. (But you have to like a plot in which the hero defeats the killer by denying him access to insulin.) It’s just that the sequence activates, in a way that directors once took for granted, aspects of film art that we don’t find too often nowadays. Once you didn’t have to choose between Steadicam logistics and static dialogue; there is a very wide middle ground if you’re willing to move actors around the set and give them some body language and prop work. No need for a walk-and-talk here.

Schema and revision

The Variety article explains that Schlamme utilizes his long walk-and-talks to save time and money. But directors in the studio era shot their fully elaborated scenes like that in Homicide to be economical as well. If actors know their lines and hit their marks, playing out pages of dialogue in a few sustained setups can be very efficient; the Homicide full shot consumes 45 seconds. I’d argue that most contemporary directors have never learned to stage scenes this way. It’s a lost skill set. I make the case in more detail in Figures Traced in Light and The Way Hollywood Tells It.

To some extent, however, another skill set has emerged. Some walk-and-talks in The West Wing and other programs have an extra feature that the Variety writer and I haven’t mentioned. Often character A and B are walking toward us down the corridor, then B drifts off and C catches up with A. A and C walk for a while, then A peels off and C picks up somebody else, and so on. This approach is suited to multiple-protagonist dramas. You can show the plotlines crossing and separating.

I’m no TV historian, but I think that this technique showed up on St. Elsewhere (1982-1988), and it’s definitely on display in ER (1994-). Hospitals again. I think we also find this mingling/ separating choreography in contemporary film, but I can’t recall many examples in earlier eras. You could argue that one of the shots in the Ambersons’ ballroom does this, though I don’t think it’s a pure instance. (The principle of overlapping character actions is at work in many Renoir films, most famously in the final party melee in Rules of the Game, but Renoir doesn’t employ what we’re calling a walk-and-talk.) Did movies pick up this intertwined walk-and-talk from TV or vice-versa? I don’t know. If you do, drop me a line!

In On the History of Film Style and Figures Traced in Light, I argue that stylistic change in filmmaking often follows a logic of what art historian E. H. Gombrich calls schema and revision. (3) A pattern or practice becomes standardized, but then creators extend it to new situations or find new possibilities in it, and they modify it.

Camera movements have long been used to link characters. For instance, when Nick Charles circulates drinks in The Thin Man, Van Dyke tracks leftward to follow him from guest to guest.

So maybe in the 1980s and 1990s, when ensemble stories had to balance attention among several major characters, directors blended the multiple-interaction aspect of lateral camera movements with the schema of the advancing walk-and-talk. The result makes characters move in and out of each others’ orbits along a single trajectory. Whoever came up with this device, I’d speculate that it arose from the realization that the backing-up walk-and-talk could be repurposed for dramas following the fates of several protagonists.

It’s only history, but it matters if we want to understand stylistic continuity and change.

(1) Thanks to Richard Maltby for passing this along.

(2) Vincent LoBrutto, Stanley Kubrick: A Biography (New York: Fine, 1997), 141-142.

(3) E. H. Gombrich, Art and Illusion: A Study in the Psychology of Pictorial Representation (Princeton, N. J. Princeton University Press, 1960), especially Chapter III.

Shot-consciousness

Most professional critics seem uninterested in the film shot as a shot. They might notice when the images call flagrant attention to themselves, as in Zhang Yimou’s recent films, or in those protracted walk-and-talk Steadicam takes. On the whole, though, reviewers prefer to talk about plot and acting.

Granted, it’s hard to be aware of shots, especially if you get engrossed in the story. But if we want to be fully alert to how movies work on us, we should keep our eyes open. Back in 1968, I read The Moving Image by Robert Gessner, one of the first teachers of cinema studies in the US. There Gessner offered a sturdy piece of advice: Be shot-conscious.

About twenty years later, trying to be shot-conscious and all, I started to notice a certain type of image becoming more common, especially in European and Asian films. Then it started to appear in US films as well, especially indie items. Now it’s very common everywhere, though it’s still not the predominant sort of shot.

Here’s a fairly early example, from R. W. Fassbinder’s Katzelmacher (1969).

How to characterize it? The camera stands perpendicular to a rear surface, usually a wall. The characters are strung across the frame like clothes on a line. Sometimes they’re facing us, so the image looks like people in a police lineup. Sometimes the figures are in profile, usually for the sake of conversation, but just as often they talk while facing front.

Sometimes the shots are taken from fairly close, at other times the characters are dwarfed by the surroundings. In either case, this sort of framing avoids lining them up along receding diagonals. When there is a vanishing point, it tends to be in the center. If the characters are set up in depth, they tend to occupy parallel rows.

Linda Linda Linda (2005)

No one to my knowledge had noticed this sort of shot, let alone named it. I started to call it mug-shot framing, but I found that art historian Heinrich Wölfflin had called it planar or planimetric composition. I went with “planimetric” because that term suggests the rectangular geometry so often seen in these shots.

What’s striking is that such imagery is quite rare before, say, 1960. We can find some examples, principally in silent comedy and especially the films of Buster Keaton (himself a pretty geometrical director). But in the 1960s, we find Antonioni and Godard using planimetric shots fairly often.

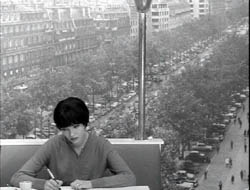

Vivre sa vie (1962)

This image design became more popular from the 1970s onward. Why? In On the History of Film Style and Figures Traced in Light, I tried to trace out some sources and functions of it. Briefly, I think that the planimetric shot emerged from filmmakers’ growing reliance on long lenses, which tend to create a flatter-looking, more cardboardy space than wide-angle lenses do. A telephoto shot makes an image seem less voluminous. It seems to be made of slices of space lined up one behind another.

Filmmakers began using long lenses for many purposes, often because of the demands of filming on location. And some directors realized that long-lens optics offered fresh resources for staging and composition.

For instance, the planimetric scheme is well-suited to a “painterly” or strongly pictorial approach to cinema. In Figures, I discuss two directors who made planimetric shots central to their style. Hou Hsiao-hsien saw very deeply into the possibilities of these shots; I think he learned it from his early skill at shooting on the street with long lenses. You can find more about that here. By contrast, Angelopoulos used the planimetric image in conjunction with architecture and landscape to create a sort of de-dramatized spectacle, a spare grandeur reminiscent of icon painting.

The Suspended Step of the Stork (1991)

The functions of the planimetric image can vary a lot. Often it’s used to suggest stasis and passivity, as in the Katzelmacher instance. Kitano Takeshi picks up on this sense of torpor in certain shots of Sonatine, which suggests that being a gangster means having a lot of time to kill just hanging out.

Kitano’s use of the image also suggests a kind of childish simplicity or naïve cinema. Unlike Hou and Angelopoulos, Kitano uses the planimetric schema as if it were just the most basic way to film anything. Line up your characters and shoot ’em, as if they were figures in South Park or Cathy.

Kitano has compared himself to the kamishibai man, the street performer who narrates stories for children by flipping through illustrated cards, and Kitano’s paintings are more sophisticated, often planimetric versions of those drawings.

The planimetric schema can suggest something more oppressive too. That’s one purpose, I think, of certain shots in Terence Davies’ remarkable Distant Voices, Still Lives. The film’s stylistic system is quite rigorous in its use of straight-on compositions, and it’s worth more attention than I can give it here. For now I’ll just mention that the first part presents tableaux of unhappiness that suggest bleak family portraits.

Here and more generally, the planimetric image often carries the connotations of a posed photograph. Possibly the dry, rectilinear imagery of Walker Evans and the wide-eyed attitudes of Diane Arbus’s portraits have contributed to the sense of stiff ceremony such shots sometimes have.

Walker Evans, Roadside Stand Near Birmingham (1936)

Asian filmmakers combined the planimetric image with very long takes. In Kore-eda Hirokazu’s Maborosi, Yumiko’s husband comes home drunk, a slip from his usual reliable habits. She has just been remembering her previous husband, dead in a bike accident. The rocklike stability of the shot, aided by the grid backing the characters, throws every gesture into relief, particularly when Yumiko’s face lifts slightly into and out of shadow in the course of the action.

In the 1990s US indie filmmakers adapted this staging strategy. In Safe, Todd Haynes uses it to suggest the hard-edged sterility of the wife’s suburban life, which surrounds her with cubical furniture.

Wes Anderson used the image schema occasionally in Bottle Rocket but came to rely on it more and more. (He tended to use wide-angle rather than longer lenses, though; note the bulging effect in the Life Aquatic shot below.)

For Anderson, as for Keaton and Kitano, the static, geometrical frame can evoke a deadpan comic quality. This comes out as well in Jared Hess’s Napoleon Dynamite.

Initially, this scheme also helped filmmakers distinguish their work from Hollywood. Mainstream American films tend to film players in 3/4 views, except for certain situations, such as a theatrical performance or a scene showing a mammoth image display.

V for Vendetta (2005)

Some American directors seem to have used the planimetric shot decoratively, as a nifty one-off touch, as here in Kiss Kiss Bang Bang.

Many overseas directors who rely on this schema adjust their cutting accordingly. In Figures I called it compass-point editing. The usual tactic is to follow one planimetric shot with a reverse shot that’s also planimetric. In the first four shots of Kitano’s A Scene at the Sea, the camera angle switches either 180 degrees or zero degrees.

When I asked Kitano why he cut this way, he gestured toward me, then at himself. “When we are speaking, this is the way we look toward each other. It’s the most natural way to show a conversation.” Apparently this is why over-the-shoulder shots are pretty rare in Kitano’s films.

Planimetric shot/ reverse shot is seldom used in Hollywood films, and it seems to be reserved for certain confrontational situations, or institutional scenes (e.g., doctor/ patient conversations). It can sometimes suggest an unnerving or unnatural encounter, as in I, Robot. The detective Spooner is calling on his old friend Dr. Lanning, and their dialogue is shot in to-camera medium-shots.

At the climax of the conversation, the camera takes up a 3/4 position and arcs around Lanning, revealing him to be only a hologram, presenting his dying message to Spooner. The planimetric image is motivated as suitable for a flat, virtual presence.

Proyas has cleverly prepared us for this subterfuge by ending the previous scene with an unremarkable planimetric framing on Spooner as elevator doors close on him.

This shot leads directly to the initial shot of Dr. Lanning above, apparently addressing us, in a sort of shot/ reverse shot cut across two scenes.

As we might expect, Godard, who helped disseminate the schema, is all up for upsetting it, in Vivre sa vie and Made in USA. The first shot below teases us to read the flat background as a high-angle vista; the second carries the idea of a conversation in a planimetric frame to a beautiful absurdity.

My quick survey doesn’t exhaust the various forms and uses of this strategy. I just wanted to show how shot-consciousness can lead us to notice when filmmakers take up new pictorial tools and modify them for particular purposes.

Another pebble in your shoe

DB here:

“Life is a Dogme film. It’s hard to hear, but the words are still important.” This is one of the many in-jokes peppering Lars von Trier’s The Boss of It All, his newest feature. I watched it while preparing an essay for the Danish Film Institute, which superbly promotes Danish cinema to the world. But I wasn’t ready for what I saw.

It’s a comedy, of course, with a classic bait-and-switch premise. For shadowy motives, a corporate lawyer entices an idle actor to pretend to be the superboss whom the IT staff has never met. Unfortunately, through emails to the staff, the lawyer has constructed a persona for the boss–in fact, several personae, a different one for every worker. Our actor must play many parts before finally, in a series of reversals, he gets to “find” the real character.

In tone, the film is as mixed as most von Trier works, hovering between sympathy for idealistic underdogs and a sour realization that they will always be victims. It reminded me somewhat of Kaurismaki and the Fassbinder of Fox and His Friends. But the film is a breezy piece of work; nothing really serious faces his innocent here. There’s a lively satire of the corporate world, mocking management catchphrases du jour (not outsourcing, we’re told, but offshoring) and touchy-feely hugging. The hostile incomprehension between Denmark and Iceland provides some good gags too. Von Trier also pokes fun at actors, perhaps invoking his well-publicized feuding with divas like Kidman and Björk. Our hero/loser Kristoffer is a sort of Method man, but he learns that he gets the best results through shameless sentiment.

Here the words are important–it’s a very talky movie–but so are the pictures. Shot in 16mm in available light, The Boss breaks with von Trier’s normal commitment to handheld camerawork. Except for some interpolated crane shots outside the office building, the camera never moves, not even panning. But the image is constantly being refreshed through incessant cutting (there are over 1500 shots). The film boasts more jump cuts than Breathless or Matchstick Men, and each one creates a bump. There’s very little sound overlap between shots–the ambient noise usually drops out for a fraction of a second–and there are often visual mismatches, so (as in The Idiots), nearly every cut feels like an ellipsis. A film, von Trier has said, should be as irritating as a pebble in your shoe, and his abrasive tempo gives his comedy an anxious edge.

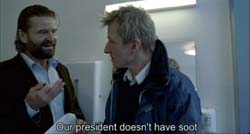

Then there are the very peculiar framings. Here’s a string of three brief shots from the first scene, with continuous dialogue (in gappy duration). The lawyer is trying to persuade the actor to perform as the boss.

(Yes, these are three separate shots, not three stages of one wobbly shot.)

These cuts break the so-called 30-degree rule, which mandates that if you’re cutting to different angles on the same subject, your second angle should vary by at least 30 degrees from the first. In addition, the later off-center compositions seem gratuitous; why not just sustain the first shot, since the next two hardly vary from it? Sometimes you get results like this.

It turns out that there is method to the madness, although the method, granted, is a bit mad. You can read about Automavision here, if you want to know in advance why the movie looks this way. But if you want to be as startled as I was, refrain. Let’s just say that von Trier’s famous 100-camera technique of Dancer in the Dark has been repurposed in a pretty unexpected way. And don’t believe what he says about surrendering to chance; the cuts are often very careful.

Whether you do your homework in advance or not, you’ll probably enjoy The Boss of It All. After my criticisms of editing in The Departed (which made me seem to be raining on the Scorsese parade) and my comments about classical principles of coverage, I’m happy to report on a film which offers something new and strange. The vivacious Danish film culture makes a space for von Trier to set up creative obstructions, for both himself and his viewers.

Postscript: Since I wrote this, von Trier announced that he’s added more tricks to his bag. Turns out that The Boss of It All employs Lookey, a game that challenges the viewers to spot objects that don’t belong in a scene. “For the casual observer it’s just a glitch or mistake,” he says, “but for the initiated it’s a riddle to be solved.” The purpose is to keep viewers alert and active. Film’s great flaw, he claims, is that “it’s a one-way medium with a passive audience.” Lookey, however whimsical, fits well with the agitating effects of the cut and sound dropouts.

The first viewer in Denmark to identify all the Lookeys correctly wins a cash prize and a chance to be an extra in von Trier’s next film.

PPS: Thanks to Vicki Synott of the Danish Film Institute.

PPPS 28 December: I just discovered a frisky website devoted to Nordic filmmaking, where Mirja Julia Minjares has gathered some interesting quotes from von Trier and his sound recordist Ad Stoop. Von Trier says that the computer program also selects for sound gain and filter. Adds Stoop: “When a computer program chooses the settings for the sound and cinematography between each shot, every edit gets underlined in the finished film.”

PPPS 31 December: Check perceptual psychologist Tim Smith’s blog for more insights into von Trier’s games with continuity editing.

–dB