Archive for the 'Film technique: Editing' Category

Wisconsin Film Festival: Four for the road

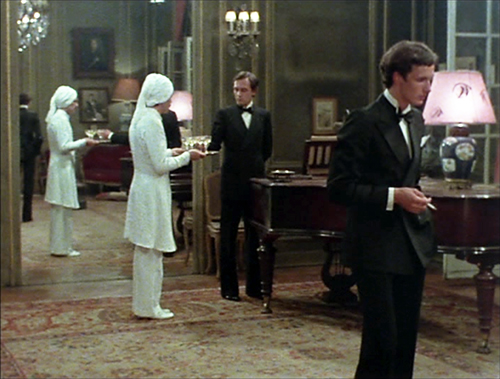

Suzanne Simonin, La religieuse de Denis Diderot (1966).

The Wisconsin Film Festival is over, and already we’re looking forward to the next one. In the meantime, here are our last thoughts on some films that impressed us.

Kristin here:

Dürrenmatt in Dakar

Hyenas (1992).

Senegalese director Djibril Diop Mambéty is known mostly for his two feature films, Touki Bouki (“The Hyena’s Journey,” 1973) and Hyenas (1992), and less so for a handful of shorts. Though unable to direct for long stretches of time, Mambéty, who died of cancer in 1998, has been well-served by preservationists. In 2013, Touki Bouki was released by the Criterion Collection in a box set of restorations by Martin Scorsese’s World Cinema Project. Now the Cinémathèque Suisse has sponsored a 4K restoration of Hyenas. As the echoes in the two titles suggests, Hyenas was intended to be the second film in a thematic trilogy about the corruption of ordinary people by greed. The third film, Malaika, was planned, but Mambéty’s early death intervened.

Hyenas is based on Swiss playwright Friedrich Dürrenmatt’s dark 1956 comedy, Der Besuch der alten Dame, known in English as The Visit. The film follows the story of the original fairly closely, at least in the play’s first two acts.

The action is set in the village of Colobane (Mambéty’s hometown, where Touki Bouki was also set). The village has fallen on hard economic times, and the genial local shopkeeper, Dramaan, helps keep the place going by extending credit to his regular customers. City officials announce the imminent arrival of Linguère Ramatou, a Colobane woman who left the village and has become extremely wealthy. Dramaan, who had courted Ramatou in their youth, is delegated to greet and butter her up (above). She, however, accuses him of having impregnated her and refused to confess to being her baby’s father. Forced to go abroad, she became a prostitute, was severely maimed in a plane crash, and ended up rich. (How is never explained). Now she promises the villagers great financial aid if they will agree to kill Dramaan.

Although the mayor indignantly refuses, Dramaan soon notices that his fellow citizens are buying luxurious goods that they should not be able to afford. He futilely tries to get local officials to protect him from assassination. All this is played for bitter comedy by an engaging cast of non-professionals. The thematic point is made clear, especially when Mambéty intercuts a pack of hyenas lurking in the nearby brush with a mob of locals who prevent Dramaan from fleeing the town.

It helps to know something about the setting, which would be familiar to Senegalese audiences. The film gives the impression that Colobane is a remote country village. In fact it is a small arrondissement of greater Dakar, a major port on the west coast of Senegal. In a lengthy overview of the director’s life, including an interview with Mambéty shortly before his death, N. Frank Ukadike explains:

The Colobane of Hyènes is a sad reminder of the economic disintegration, corruption, and consumer culture that has enveloped Africa since the 1960s. “We have sold our souls too cheaply,” Mambéty once said. “We are done for if we have traded our souls for money. That is why childhood is my last refuge.” But what remains of Colobane is not the magical childhood Mambéty pines for. In the last shot of Hyènes, a bulldozer erases the village from the face of the earth. A Senegalese viewer, one writer has claimed, “would know what rose in its place: the real-life Colobane, a notorious thieves’ market on the edge of Dakar.”

The last shot is startling, as it reveals for the first time (at least to non-Senegalese viewers) that Colobane is located right up against a city. Possibly in Mambéty’s childhood it was a village later absorbed by the spread of Dakar. It’s not clear from the film when the action is taking place, although Ukadike suggests that it must be in the 1960s or later. The implication of the final shot is that the corruption of the villagers is as much an urban problem as a rural one–if not more so.

The restoration has resulted in vibrantly colorful images that emphasize the indigenous costumes, particularly of Ramatou and her entourage (see bottom). Metrograph is releasing the film theatrically in the US, and with luck a Blu-ray will eventually make it more widely available.

David here:

Anomalies in the space-time continuum

Vultures (2018).

Almost from the start, popular moviemaking has played tricks with linear time and space. Edwin S. Porter’s Life of an American Fireman (1903) contains both a dream and editing that replays key actions from two viewpoints. The more developed silent cinema explored flashbacks, subjective viewpoints, and other strategies. By the 1940s, filmmakers around the world were trying these tricks in sound movies, all seeking to enhance curiosity or suspense or surprise.

Most of the movies that play with space and time resolve the uncertainties clearly. The opening of Mildred Pierce skips over important moments without telling us, but by the end a flashback fills them in. This sort of gamesmanship has remained a permanent resource of mainstream cinema, especially in genres that rely on crime and mystery. Think of Pulp Fiction or Memento or The Usual Suspects, or more recently Identity, Side Effects, or the many heist movies that conceal crucial parts of the plan.

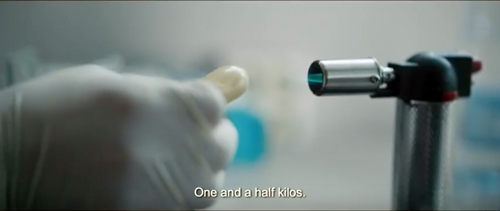

Börkur Sigpórsson’s debut feature Vultures is a good example of a conventional crime film made more intriguing by the way it’s told. The basic story is formulaic. An Icelandic real-estate developer needs to replace money he’s embezzled, and so sets up a drug-smuggling deal. He enlists his ex-con brother Atli to help the mule, a Serbian woman named Zonia, get through airport security. After that, Zonia has to be sequestered until she evacuates the pellets of cocaine she’s swallowed. In the meantime, Lena the policewoman gets on the trail. The whole scheme falls apart when Zonia collapses and Atli starts to take pity on her, while Erik decides to get the pellets by any means necessary.

This straightforward arc of action is presented in fragments that jump among time frames. Before the credits, we see Zonia hesitantly gulping down the pellets, getting sick on the flight into Reykjavík, and hiding in a toilet. She’s frightened when she hears a knock on the door.

Flash back to follow Atli and Erik planning the smuggling scheme. Then, via brief replays, we’re back with Zonia swallowing the pellets, Zonia on the plane (with Atli now revealed as a fellow passenger), and Zonia bolting to the toilet. He’s the one knocking on the door.

This sort of back-and-fill pattern sharpens our interest by delaying the revelation of who’s knocking on the door, while also filling us in on the brothers’ scheme. The interpolation also allots some sympathy to Atli. In the flashback he’s shown visiting his drug-devastated mother and trying to reassure his wife that he’s going to be providing for her and his son. Soon we see him distracting the airport police so that Zonia can pass through freely. The deal seems to have come off. All they have to do is retrieve the pellets.

Abruptly we skip far ahead in time to reveal a bit of the end of the story. I won’t provide a spoiler, but let’s just say that whatever certainty we gain about the outcome is provisional and partial. Still, with this small anchor in Now, the narration doubles back again through a long flashback that traces the unraveling of Erik’s scheme.

As often happens with flashback construction, the time-shifting in Vultures has a double impact. It teases us with hints about what will happen, and it forces us to concentrate on how and why it happens. (Something similar is at work in Duvivier’s Lydia, which I analyze in this month’s “Observations on Film Art” installment on the Criterion Channel.) Told more linearly, Vultures wouldn’t have been so engaging, I think. Nor would it have so sharply focused our concern about the characters’ decisions. And that crucial glimpse of the future allows us to hope that Zonia’s fate isn’t what it would have seemed to be if her story had been presented in 1-2-3 order. As usual, the how of storytelling is as important as the what.

During the 1950s, films not only fractured their action in challenging ways but also refused to resolve all the questions that were raised. We might not fully understand everything that happened. This strategic ambiguity has been central to what’s sometimes called “art cinema,” and is nicely showcased in Pause, another debut feature. If Vultures plays hob with the crime movie, Cypriot director Tonia Mishiali gives us a jagged domestic drama, a diary of a going-mad housewife.

Elpida is falling apart. The darkly comic opening scene, with a doctor ticking off a virtually endless list of her ailments, portrays her as enervated and beaten-down. How she got that way becomes clear. Her husband Costas shovels in food in angry silence. He watches soccer on their main TV, while she has to watch her violent crime videos with headphones. He comes and goes as he pleases; she steals time to attend a painting class or have coffee with a neighbor. When he decides to sell her car without further discussion, and when a young contractor comes to repaint their apartment house, Elpida dares to imagine life without the lout she married.

Imagine is the key word. From her drab routines we pass without warning into fantasies of resistance, escape, and payback. At first, the visual narration makes clear that these acts of rebellion are wholly in her mind. As the film goes along, however, the boundary gets fuzzy. Is the breezy workman making a pass at her, or is she just wishing for it? Is she really drugging Costas’ coffee? And is murder in the offing?

The cinematography won’t tell us. Like Vultures, Pause presents its story through a now-standard blend of planimetric framings and a “free-camera” handheld style that suggests nervous urgency. The fantasies are treated through both techniques.

A woman’s domestic discontents, projected through fantasy, has been a mainstay of cinema since at least Germaine Dulac’s Smiling Madame Beudet (1923). Here, Mishiali’s careful pacing of Elpida’s household chores establishes a solid rhythm that’s broken by the imaginary moments. Like many modern films, the drama builds up by immersing us in the characters’ routines and then disturbing them with sudden outbursts. Yet the climax is remarkably quiet, further teasing us about what may or may not have happened. In any case, by the end, Elpida may be liberated. Yet her final laughter, echoing through the end credits, doesn’t feel especially jubilant.

Get thee from a nunnery

Suzanne Simonin, La religieuse de Denis Diderot was Jacques Rivette’s second feature. In 1962 he submitted a screenplay to censorship authorities but was told that if the film were made it would probably be banned. After another try in 1963, a third version was cautiously accepted, with the warning that it might well be forbidden to viewers under 18.

Shooting began in September of 1965. Catholic groups immediately objected. After a public outcry, in which Godard called on Minister of Culture André Malraux to intervene, there was a screening at the 1966 Cannes Film Festival. The film wasn’t released in France until July of 1967. Usually known as La religieuse (The Nun), it’s gone largely unseen in America. We were lucky to screen the sparkling 4K version that Rialto is now distributing.

The story is set in the years 1757-1760. Suzanne, illegitimate daughter of a prominent household, is parked in a convent, like many women who had no other life chances. Her first Mother Superior, who treats her with affection, dies and is succeeded by a harsh younger woman. Suzanne loves God but resists the rigid discipline. She’s beaten and starved, denied access to her Bible, and believed to be possessed.

She’s rescued by church officials and a kindly lawyer, who oversee her transfer to a very different convent. That’s run by a sexy, permissive Mother Superior who seems anxious to bed our heroine. Suzanne finds the license of her new home as disquieting as the asceticism of the old one. In the end, she escapes with a priest who abandons his vows. Soon she’s on her own in a grimy secular milieu.

No wonder the French church was outraged. True, Diderot’s novel was a classic, and Rivette had already mounted the story as a play. But on film the revelation of ecclesiastical corruption was vivid and shocking, and the presence of New Wave star Anna Karina gave it undeniable prestige. Popularity, too: It attracted more than 2.9 million spectators, making it the ninth most successful release of the year. (Films by Godard, Rohmer, Bresson, Bergman, and Chabrol drew fewer than half a million.) Rivette’s first feature, Paris nous appartient (1961) had drawn only about 29,000. As often happens, creating a scandal proved good for business.

Seen today, La religieuse is hard to imagine as a mass-audience hit. Rivette presents his inflammatory plot with a calm austerity. The dominant colors, at least for the first seventy minutes or so, are shades of beige, brown, white, and black. Shot in very long takes, usually at a distance from the action, the scenes are confined largely to chapels, corridors, and sparsely furnished rooms. La religieuse exemplifies what one wing of Cahiers du cinéma called “classical” direction. As a critic, Rivette admired Hawks, Preminger, Rossellini, the American Lang, and late Dreyer for their sober, unemphatic staging of performances. In place of flashy angles and aggressive cutting, mise-en-scène should center on expressive bodies and faces captured from a respectful distance.

In a 1974 interview, Rivette explained that his most proximate influence was Mizoguchi Kenji–a director who made the restrained, long-take scene central to his style. While most scenes in La religieuse are cut up a little, Rivette seldom moves nearer than medium-shot distance. He uses close-ups with the same parsimony that Mizoguchi displays. Most directors would have cut in to a closer view of Suzanne when, kneeling, she’s asked to pray to Jesus, but Rivette obstinately makes her gesture part of a nearly two-minute shot.

This might seem a stagy approach, especially if you remember Rivette’s interest in varieties of theatre. But like other Cahiers critics, he believed that “classical” filmmaking harbored qualities that also kept cinema “modern,” on the aesthetic and moral edge.

In the abrupt editing of the long takes in Dreyer’s Gertrud (1964), Rivette found a revival of the powers of montage. Dreyer didn’t hesitate to interrupt moving shots. Rivette felt that the film exploited “tantalizing cuts, deliberately disturbing, which mean that the spectator is made to wonder where Gertrud ‘went’; well, she went in the splice.”

In La religieuse, most cuts within scenes are axial, not reverse angles, and they often mismatch action in ways that break the flow of the long takes.

At other moments, Rivette’s editing subjects his distant shots to ellipses that recall Godard’s jump-cuts and Resnais’ experiments in Muriel. We get space-time anomalies more abrasive than those in Vultures and Pause.

Suzanne is in her cell, fretfully pacing. She pauses and, thanks to a cut, seems to look at herself at prayer.

She drifts to her needlework, and suddenly a cut takes her back to the other side of the room.

While she looks in the mirror, the camera backs up and, continuing over a cut, arcs to the right to reveal that she’s already flung herself onto her bed.

Where did Suzanne go? Well, she went in the splices.

It’s wonderful to have this quietly astonishing film available again. The ever-reliable Kino Lorber is bringing out a Blu-ray edition next month, with commentary by Nick Pinkerton, a critical essay by Dennis Lim, and a new documentary about the production. Don’t you want one? I bet you do.

Thanks as usual to the coordinators of our film festival–Jim Healy, Ben Reiser, Mike King, and Zach Zahos–as well as their colleagues and the hordes of cheerful volunteers who kept everything running smoothly.

The information about Colobane from N. Frank Ukadike is from his article on California Newsreel. For a trailer of the restored Hyenas, see here.

The information on La Religieuse‘s censorship struggles comes from Jean-Michel Frodon, L’Âge moderne du cinéma français: De la Nouvelle Vague à nos jours (Flammarion, 1995), 149-151. Rivette’s comments on Mizoguchi’s influence are in this Film Comment interview from 1974. His remarks on Gertrud are part of a 1969 Cahiers du cinéma panel discussion, “Montage,” translated in Rivette: Texts and Interviews, ed. Jonathan Rosenbaum (British Film Institute, 1977), 86-87. The conversation is available online at DVDBeaver. I derived attendance figures from Simon Simsi, Ciné-Passions: 7e art et industrie de 1945 à 2000 (Dixit/CNC, 2000), 46-47.

What’s an axial cut? Glad you asked. Kurosawa uses them (here too), as does Eisenstein and his Soviet peers and French avant-gardists. Silent cinema has plenty, but so do the films of Wes Anderson and John McTiernan. And The Simpsons, often.

Our first full day of the festival opened with a screening of Ozu’s Good Morning (Ohayo), selected by guest Phil Johnston, and the final show a week later presented Jackie Chan’s Police Story. (The first is already available in a Criterion disc, the second is coming soon.) Now that’s what I call a film festival.

Hyenas (1992).

Is there a blog in this class? 2018

24 Frames (2017)

Kristin here:

David and I started this blog way back in 2006 largely as a way to offer teachers who use Film Art: An Introduction supplementary material that might tie in with the book. It immediately became something more informal, as we wrote about topics that interested us and events in our lives, like campus visits by filmmakers and festivals we attended. Few of the entries actually relate explicitly to the content of Film Art, and yet many of them might be relevant.

Every year shortly before the autumn semester begins, we offer this list of suggestions of posts that might be useful in classes, either as assignments or recommendations. Those who aren’t teaching or being taught might find the following round-up a handy way of catching up with entries they might have missed. After all, we are pushing 900 posts, and despite our excellent search engine and many categories of tags, a little guidance through this flood of texts and images might be useful to some.

This list starts after last August’s post. For past lists, see 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016, and 2017.

This year for the first time I’ll be including the video pieces that our collaborator Jeff Smith and we have since November, 2016, been posting monthly on the Criterion Channel of the streaming service FilmStruck. In them we briefly discuss (most run around 10 to 14 minutes) topics relating to movies streaming on FilmStruck. For teachers whose school subscribes to FilmStruck there is the possibility of showing them in classes. The series of videos is also called “Observations on Film Art,” because it was in a way conceived as an extension of this blog, though it’s more closely keyed to topics discussed in Film Art. As of now there are 21 videos available, with more in the can. I won’t put in a link for each individual entry, but you can find a complete index of our videos here. Since I didn’t include our early entries in my 2017 round-up, I’ll do so here.

As always, I’ll go chapter by chapter, with a few items at the end that don’t fit in but might be useful.

[July 21, 2019: In late November, 2018, the Filmstruck streaming service ceased operation. On April 8, 2019, it was replaced by The Criterion Channel, the streaming service of The Criterion Collection. All the Filmstruck videos listed below appear, with the same titles and numbers, in the “Observations on Film Art” series on the new service. Teachers are welcome to stream these for their classes with a subscription.]

Chapter 3 Narrative Form

David writes on the persistence of classical Hollywood storytelling in contemporary films: “Everything new is old again: Stories from 2017.”

In FilmStruck #5, I look at the effects of using a child as one of the main point-of-view figures in Victor Erice’s masterpiece: “The Spirit of the Beehive–A Child’s Point of View”

In FilmStruck #13, I deal with “Flashbacks in The Phantom Carriage.”

FilmStruck #14 features David discussing classical narrative structure in “Girl Shy—Harold Lloyd Meets Classical Hollywood.” His blog entry, “The Boy’s life: Harold Lloyd’s GIRL SHY on the Criterion Channel” elaborates on Lloyd’s move from simple slapstick into classical filmmaking in his early features. (It could also be used in relation to acting in Chapter 4.)

In FilmStruck #17, David examines “Narrative Symmetry in Chungking Express.”

Chapter 4 The Shot: Mise-en-Scene

In choosing films for our FilmStruck videos, we try occasionally to highlight little-known titles that deserve a lot more attention. In FilmStruck #16 I looks at the unusual lighting in Raymond Bernard’s early 1930s classic: “The Darkness of War in Wooden Crosses.”

FilmStruck #3: Abbas Kiarostami is noted for his expressive use of landscapes. I examine that aspect of his style in Where Is My Friend’s Home? and The Taste of Cherry: “Abbas Kiarostami–The Character of Landscape, the Landscape of Character.”

Teachers often request more on acting. Performances are difficult to analyze, but being able to use multiple clips helps lot. David has taken advantage of that three times so far.

In FilmStruck #4, “The Restrain of L’avventura,” he looks at how staging helps create the enigmatic quality of Antonionni’s narrative.

In FilmStruck #7, I deal with Renoir’s complex orchestration of action in depth: “Staging in The Rules of the Game.”

FilmStruck #10, features David on details of acting: “Performance in Brute Force.”

In Filmstruck #18, David analyses performance style: “Staging and Performance in Ivan the Terrible Part II.” He expands on it in “Eisenstein makes a scene: IVAN THE TERRIBLE Part 2 on the Criterion Channel.”

FilmStruck #19, by me, examines the narrative functions of “Color Motifs in Black Narcissus.”

Chapter 5 The Shot: Cinematography

A basic function of cinematography is framing–choosing a camera setup, deciding what to include or exclude from the shot. David discusses Lubitsch’s cunning play with framing in Rosita and Lady Windermere’s Fan in “Lubitsch redoes Lubitsch.”

In FilmStruck #6, Jeff shows how cinematography creates parallelism: “Camera Movement in Three Colors: Red.”

In FilmStruck 21 Jeff looks at a very different use of the camera: “The Restless Cinematography of Breaking the Waves.”

Chapter 6 The Relation of Shot to Shot: Editing

David on multiple-camera shooting and its effects on editing in an early Frank Capra sound film: “The quietest talkie: THE DONOVAN AFFAIR (1929).”

In Filmstruck #2, David discusses Kurosawa’s fast cutting in “Quicker Than the Eye—Editing in Sanjuro Sugata.”

In FilmStruck #20 Jeff lays out “Continuity Editing in The Devil and Daniel Webster.” He follows up on it with a blog entry: “FilmStruck goes to THE DEVIL”,

Chapter 7 Sound in the Cinema

In 2017, we were lucky enough to see the premiere of the restored print of Ernst Lubitsch’s Rosita (1923) at the Venice International Film Festival in 2017. My entry “Lubitsch and Pickford, finally together again,” gives some sense of the complexities of reconstructing the original musical score for the film.

In FilmStruck #1, Jeff Smith discusses “Musical Motifs in Foreign Correspondent.”

Filmstruck #8 features Jeff explaining Chabrol’s use of “Offscreen Sound in La cérémonie.”

In FilmStruck #11, I discuss Fritz Lang’s extraordinary facility with the new sound technology in his first talkie: “Mastering a New Medium—Sound in M.”

Chapter 8 Summary: Style and Film Form

David analyzes narrative patterning and lighting Casablanca in “You must remember this, even though I sort of didn’t.”

In FilmStruck #10, Jeff examines how Fassbender’s style helps accentuate social divisions: “The Stripped-Down Style of Ali Fear Eats the Soul.”

Chapter 9 Film Genres

David tackles a subset of the crime genre in “One last big job: How heist movies tell their stories.”

He also discusses a subset of the thriller genre in “The eyewitness plot and the drama of doubt.”

FilmStruck #9 has David exploring Chaplin’s departures from the conventions of his familiar comedies of the past to get serious in Monsieur Verdoux: “Chaplin’s Comedy of Murders.” He followed up with a blog entry, “MONSIEUR VERDOUX: Lethal Lothario.”

In Filmstruck entry #15, “Genre Play in The Player,” Jeff discusses the conventions of two genres, the crime thriller and movies about Hollywood filmmaking, in Robert Altman’s film. He elaborates on his analysis in his blog entry, “Who got played?”

Chapter 10 Documentary, Experimental, and Animated Films

I analyse Bill Morrison’s documentary on the history of Dawson City, where a cache of lost silent films was discovered, in “Bill Morrison’s lyrical tale of loss, destruction and (sometimes) recovery.”

David takes a close look at Abbas Kiarostami’s experimental final film in “Barely moving pictures: Kiarostami’s 24 FRAMES.”

Chapter 11 Film Criticism: Sample Analyses

We blogged from the Venice International Film Festival last year, offering analyses of some of the films we saw. These are much shorter than the ones in Chapter 11, but they show how even a brief report (of the type students might be assigned to write) can go beyond description and quick evaluation.

The first entry deals with the world premieres of The Shape of Water and Three Billboards outside Ebbing, Missouri and is based on single viewings. The second was based on two viewings of Argentine director Lucretia Martel’s marvelous and complex Zama. The third covers films by three major Asian directors: Kore-eda Hirokazu, John Woo, and Takeshi Kitano.

Chapter 12 Historical Changes in Film Art: Conventions and Choices, Traditions and Trends

My usual list of the ten best films of 90 years ago deals with great classics from 1927, some famous, some not so much so.

David discusses stylistic conventions and inventions in some rare 1910s American films in “Something familiar, something peculiar, something for everyone: The 1910s tonight.”

I give a rundown on the restoration of a silent Hollywood classic long available only in a truncated version: The Lost World (1925).

In teaching modern Hollywood and especially superhero blockbusters like Thor Ragnarok, my “Taika Waititi: The very model of a modern movie-maker” might prove useful.

Etc.

If you’re planning to show a film by Damien Chazelle in your class, for whatever chapter, David provides a run-down of his career and comments on his feature films in “New colors to sing: Damien Chazelle on films and filmmaking.” This complements entries from last year on La La Land: “How LA LA LAND is made” and “Singin’ in the sun,” a guest post featuring discussion by Kelley Conway, Eric Dienstfrey, and Amanda McQueen.

Our blog is not just of use for Film Art, of course. It contains a lot about film history that could be useful in teaching with our other textbook. In particular, this past year saw the publication of David’s Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Hollywood Storytelling. His entry “REINVENTING HOLLYWOOD: Out of the past” discusses how it was written, and several entries, recent and older, bear on the book’s arguments. See the category “1940s Hollywood.”

Finally, we don’t deal with Virtual Reality artworks in Film Art, but if you include it in your class or are just interested in the subject, our entry “Venice 2017: Sensory Saturday; or what puts the Virtual in VR” might be of interest. It reports on four VR pieces shown at the Venice International Film Festival, the first major film festival to include VR and award prizes.

Monsieur Verdoux (1947)

FilmStruck goes to THE DEVIL: A guest post by Jeff Smith

The Devil and Daniel Webster (1941).

Jeff here:

Last week, the latest in our series of “Observations on Film Art” videos dropped on FilmStruck. The topic this time was continuity editing in The Devil and Daniel Webster.

Many of our faithful blog readers are surely familiar with the techniques and devices that make up the continuity system. The video is really intended to be a primer for the uninitiated. It illustrates some of the basic formal elements of classical continuity, such as the eyeline match, shot/reverse shot, and the 180° rule.

In the video, I tried to highlight some of the reasons why the continuity system became common among popular cinemas around the globe. The tacit principles of the continuity system help ensure that:

- the story’s dimensions of space and time are clearly communicated to the audience

- characters’ and objects’ positions remain relatively constant from shot to shot

- that eyelines and screen direction stay consistent

- the spectator’s attention is guided to the most salient details in a scene.

The last may be the most important, if least understood. Several perceptual psychologists argue that one of the things that makes cinema a unique art form is its ability to produce attentional synchrony among viewers.

Editing is not the only means of guiding attention, to be sure. Filmmakers use lighting, composition, figure movement, camera movement, and blocking to nudge us to look at particular areas of the frame. The continuity system, though, further harnesses these shifts of attention by yoking them to the timing of cuts. Cuts are often coordinated with natural attention cues in a scene, such as conversational turns, changes in where the characters look, and pointing gestures. As Tim J. Smith, Daniel Levin, and James E. Cutting put it, “By piggy-backing on natural visual cognition, Hollywood style presents a highly artificial sequence of viewpoints in a way that is easy to comprehend, does not require specific cognitive skills, and may even be perceived by viewers who have never watched film before.”

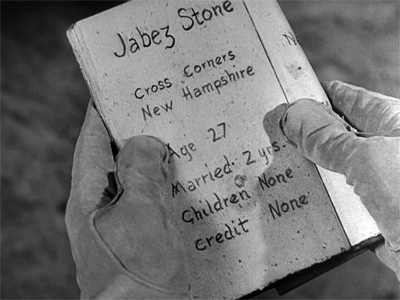

In its deployment of classical Hollywood editing techniques, The Devil and Daniel Webster doesn’t do anything particularly special. Rather, in telling the story of how a New Hampshire farmer, Jabez Stone, sold his soul to the devil, it beautifully illustrates the clarity and efficiency of Hollywood craft at the height of the studio era. Indeed, the editing epitomizes the style of director William Dieterle as a whole: simple, direct, no fuss, no muss.

That being said, The Devil and Daniel Webster does add a few wrinkles to the usual Hollywood style. For example, it uses “trick film” techniques dating back to the era of George Melies to highlight the magical powers of the diabolical Mr. Scratch.

When Jabez throws an axe, it is initially seen as a blur heading straight for Scratch’s head.

A combination of stop-motion substitution and rear projection shows the axe freeze in midair.

A traveling matte is then used as the axe bursts into flames.

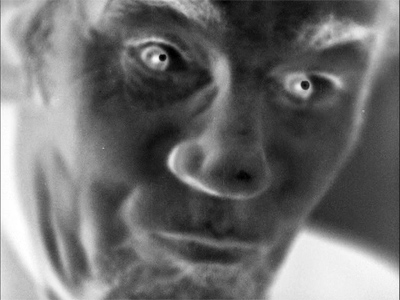

Moreover, the Criterion DVD contains deleted scenes from an earlier preview version of the film titled Here is a Man. This alternate version was, in fact, more formally adventurous than the one commonly seen by contemporary audiences. Each time something bad befalls Jabez during the first 20 minutes of the film, Here is a Man cuts to a few frames of photographic negative of Scratch. For instance, when Mary accidentally falls off a wagon, Dieterle cuts to Walter Huston smugly pursing his lips.

Dieterle and his collaborators wisely removed these shots from the final version of the film. The opening scene shows Scratch with Jabez’s name in a small book he carries with him.

When ruinous things start happening to Jabez, viewers naturally infer that Scratch caused them. The oddball moments in Here is a Man, unlike the other effects shots, don’t really add any new information and are heavy-handed in their symbolism.

The Long and the Short of It: Adapting Stephen Vincent Benét to the Silver Screen

Beyond offering good examples of editing craft, The Devil and Daniel Webster is of interest today for other reasons. One involves some of the creative choices made by Stephen Vincent Benét and Dan Totheroh in adapting the former’s short story, first published by The Saturday Evening Post in 1936. The second issue I’ll explore has to do with the way the film speaks to political issues of its moment. It seems endorse a collectivist vision of society as a counter to the excesses of unrestrained capitalism.

Most film adaptations use books for their source material, and most screenwriters face the challenge of condensing the book’s narrative to fit the running time of a typical feature film (roughly about two hours). In the case of The Devil and Daniel Webster, Benét and Totheroh faced the opposite problem.“The Devil and Daniel Webster” runs less than twenty pages in a Hythloday Press collection of Benét’s short stories. So how do you stretch Benét’s relatively slim tale to fit a 107 minute running time? Benét and Totheroh did what most screenwriters do when they confront the same dilemma. They add incidents, invent new characters, and develop new subplots, adding this material to the existing story spine.

Some print editions of Benét’s story break it into five parts with each new segment introduced with a Roman numeral. Part I introduces Daniel Webster via the tall tales told about him in the New England area. It also provides exposition to Jabez’s blighted existence, and the deal he makes with the devil. After breaking his plow on a stone, Jabez angrily proclaims, “I vow it’s enough to make a man want to sell his soul to the devil. And I would, too, for two cents!”

Part II covers the seven-year period of prosperity Jabez enjoys as well as his interest in contesting the mortgage held by the mysterious stranger. This section also establishes the stranger’s mystical powers as Jabez hears the voice of his neighbor, Miser Stevens, coming from a moth-like creature that the stranger captures in a bandanna.

Part III describes Jabez’s recruitment of Daniel Webster for his defense and the preparations for trial. Parts IV and V depict the trial itself. The former introduces the judge and jury, and portrays Daniel’s passionate defense of Jabez. The latter tells of the jury’s verdict and Daniel’s banishment of Mr. Scratch from New Hampshire.

One of the most striking things about Benét’s original story is how much of it focuses on the trial itself. Approximately half of the story covers Webster’s initial deliberations with Mr. Scratch, his demand for a trial, and the legal proceedings. In contrast, these story events account for less twenty percent of the film’s running time.

In expanding the story to feature length, Benét and Totheroh add new incidents, characters, and subplots to the early and middle sections of the screenplay. Consider, for example, Benét’s economy in his prose description of Jabez’s misfortunes:

If he planted corn, he got borers; if he planted potatoes, he got blight. He had good-enough land, but it didn’t prosper him; he had a decent wife and children, but the more children he had, the less there was to feed them. If stones cropped up in his neighbor’s field, boulders boiled up in his; if he had a horse with the spavins, he’d trade it for one with the staggers and give something extra.

Years of toil and trouble for Jabez are compressed into three sentences. When Jabez breaks his plowshare, it becomes simply the proverbial straw on the camel’s back, coming at a time when his wife and children are sick and even his horse has a rheumy cough.

In their script, Benét and Totheroh create a handful of new vignettes to illustrate Jabez’s rotten luck. In the film’s first scene, Jabez’s pig breaks its leg after being chased by the family dog. Later, Jabez’s wife, Mary, takes a tumble off their wagon when trying to stop her husband from selling the family’s calf. Still later, a fox gets into Jabez’s henhouse. In the film, Jabez’s breaking point comes not with the plow, but after he spills precious seed in a puddle just outside his barn. Unlike the story’s description of blight and corn borers, these brief episodes not only visualize Jabez’s tribulations, but also contain their own short dramatic arcs.

Another way Benét and Totheroh expand the original story is to add depth and specificity to its secondary characters. In the original, Miser Stevens never appears as anything more than an insect that’s escaped from Scratch’s collecting box. In the film, he is much more fully fleshed-out character, especially as embodied by the wonderful character actor, John Qualen.

Benét and Totheroh’s screenplay uses Stevens to create important story parallels. Like Scratch, who possesses a mortgage on Jabez’s soul, Stevens holds the mortgage to the Stone farm. Yet, Stevens also has made a Faustian bargain with Mr. Scratch. His death at Jabez’s party lingers over the rest of the film, a vivid reminder of what’s at stake during the trial.

Benét’s story also treats Jabez’s wife and children quite impersonally. The characters are never named. The references to them mostly add narrative weight to Jabez’s sense of burden. In contrast, the film version not only give these characters names and individual traits, but also uses them to highlight changes Jabez undergoes once he becomes a wealthy landowner. Jabez and his wife, Mary, frequently argue about disciplining their son, Daniel. Jabez indulges Daniel, spoiling him but offering little in the way of love. Similarly, after becoming successful, Jabez also falls short of what we’d expect of a caring husband.

In the middle parts of the film, Jabez becomes crueler and harder. He starts treating trespassers on his land more harshly. He even fires a weapon at one in an effort to scare him away. His anti-social attitudes make him an outcast among the citizenry of Cross Corners.

As was the case with Jabez’s family, the film gives the townspeople more life and personality. Early on, they serve to motivate Daniel Webster’s presence in the story, welcoming him to Cross Corners and serving as a receptive audience for the Senator’s political views. Later, the townspeople act as a foil for Jabez, establishing an important thematic contrast between his laissez faire mindset and their more communitarian values.

Lastly, Benét and Totheroh also invent several new characters for the film adaptation. Of these, the most important is Belle. Loosely allied with Mr. Scratch, Belle is ostensibly Daniel’s nanny, but is implied to be Jabez’s mistress. Belle supplies a sexual temptation not present in the original story, and this complements the temptations of wealth and power. In this respect, the character anticipates the femme fatales found in the cycle of films noir that appear later in the forties, especially as played by Simone Simon at her most fetching.

Although Dieterle was best known for costume pictures rather than film noir, the photographic style of The Devil and Daniel Webster sometimes displays the kind of dark, moody look we associate with noir’s Germanic influence. Consider, for example, the shot of Scratch’s entrance into Jabez’s barn. The mists, the backllight, and the gnarled tree in the background all foreshadow the darkness that will soon take hold of Jabez’s soul.

In the case of The Devil and Daniel Webster, tracing the film’s lineage back to German expressionism is fairly easy. Prior to becoming a director, Dieterle was an actor in dozens of German silent films, including F.W. Murnau’s Faust (1926). Murnau’s adaptation of Goethe’s play not only shares its narrative conceit with Dieterle’s film, but is also one of the most strikingly photographed of his twenties masterpieces.

Looking both backward and forward, The Devil and Daniel Webster might seem like a link between German Expressionism and American film noir. Like German films of the 1910s and 1920s, Dieterle’s film contains some of the fantasy elements found in canonical titles like The Student of Prague (1913), Der Golem (1915), or The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920). Dieterle’s curious afterlife fantasy Six Hours to Live (1932), discussed in an earlier entry, has a strong affinity with Gothic and Expressionist imagery. Like films noir of the forties, the cinematographic style of The Devil and Daniel Webster captures the story’s dark, fatalistic tone.

Indeed, the look of the final trial scene displays the same sort of stylization seen in the dream sequence of The Stranger on the Third Floor (1940), a film often seen as a key noir progenitor.

Still, Dieterle also retains the folksy Americana that was an appealing part of Benét’s original story. Some of the characters, like Ma Stone or Squire Slossum, seem like they’ve wandered into the story from one of Frank Capra’s small towns or John Ford’s rural comedies. This combination makes The Devil and Daniel Webster a true original. Indeed, it might count as an almost singular example of “cracker barrel noir” if the term itself didn’t seem like a complete oxymoron.

Things That Make a Country a Country, and a Man a Man: Benét’s Tale as Allegory

One of the other things that interests me about The Devil and Daniel Webster is the degree to which both the story and the film can be read as allegory. Benét’s original narrative certainly makes American identity a central theme. The opening paragraph proposes that, if you go to Daniel Webster’s gravesite and call his name, you’ll hear his deep, rolling voice ask, “Neighbor, how stands the Union?” Benét adds, “Then you better answer the Union stands as she stood, rock-bottomed and coppersheathed, one and indivisible, or he’s liable to rear right out of the ground.” This description not only foreshadows the oratorical power that Webster will display when Jabez goes on trial, but also the sacrifices Scratch prophesies. These include Webster’s loss of two sons in combat and a missed opportunity to become president.

Later, Webster will challenge Scratch on the grounds of his nationality, saying “no American citizen may be forced into the service of a foreign prince.” Scratch responds that he is an American, and further that he was present for “the first wrong done to the first Indian” and when the first American slave ship set sail for the Congo. Moreover, when Scratch assembles his jury, he selects a group of black-hearted souls whose dark deeds affected the course of the nation’s history. Among them is the pirate Edward Teach, otherwise known as Blackbeard. There’s also Walter Butler, the architect of the Cherry Valley massacre; Simon Girty, who burnt men at the stake; and Governor Thomas Dale, who Benét claims “broke men on the wheel.” Overseeing the proceedings is Judge John Hathorne, a magistrate in Salem who supervised some of the witch trials.

The larger significance of these passages is hard to ignore. Jabez may be on trial within the narrative, but Benét seems to put America itself on trial. The plaintiff and defendant, thus, come to symbolize the yin and yang of America’s soul. Webster represents the virtues that define the American ethos: grit, pluck, ingenuity, and liberty. Scratch, on the other hand, associates himself with the nation’s original sins: genocide, slavery, cruelty, torture, and theocratic inquisition. Webster emerges victorious in the legal battle, but as he says in his summation, our citizens’ hard-won freedom came at a cost of suffering and tribulation. Successes and failures are all part of the great journey of humanity. Says Webster, “And everybody had played a part in it, even the traitors.”

Dieterle’s film preserves all of these elements of Benét’s short story, but adds a couple of wrinkles of its own. First, General Benedict Arnold is added to the film’s panel of jurors, even though he is pointedly absent from the original. In the story, Webster observes that he misses Arnold’s company and is told that the General is engaged in other business. Benedict Arnold is not only fully present in the film version, but is even featured prominently during the trial scene in several medium close-ups.

Webster even singles out Arnold in his impassioned defense of Jabez’s character. Using Arnold’s betrayal of his country as a cautionary tale, the orator asks the jury to give Jabez the second chance that the devil denied to them.

The other, even more important, change made by Benét and Totheroh is the subplot concerned with the formation of the Grange. Officially known as the Order of the Patrons of Husbandry, the Grange was founded in 1867 to promote the interests of farmers and rural communities. But Webster died in 1852. As an addition to the screenplay of The Devil and Daniel Webster, the Grange seems to be a historical anomaly.

So why this anachronistic subplot? The simple answer is that it sharpens the conflict between Jabez and the other townspeople. Not only is he differentiated in class, but he’s set apart by his personal values. The less obvious answer involves the film’s historical context. Released in 1941, the story of a lone holdout resisting the pressure of others in his community likely would evoke broader geopolitical issues. The plea for unity in the face of existential evil would seem to suggest The Devil and Daniel Webster works as an allegorical critique of American isolationism on the threshold of World War II.

Like other allegories, this type of reading follows a pattern of metaphorical substitution. The Grange becomes a stand-in for the Allied Powers. Scratch represents Hitler, Mussolini, Tojo, and other Axis leaders. And, as discussed above, Stone and Webster symbolize America itself.

Dieterle’s earlier career in Hollywood also offers some additional warrant for this interpretation. He was a German Jew who emigrated to the U.S. in 1930. His relocation was less about fleeing the Nazis than it was the opportunity to work for Warner Bros. Still, Dieterle bore witness to the corrosive effects of Nazi ideology, and his directorial assignments show a loose affiliation with anti-Fascist politics. He helmed The Life of Emile Zola, a Warners biopic that depicts the French author’s involvement in the Dreyfus affair. The film won the Oscar for Best Picture in 1938. Thanks to its timely exploration of anti-Semitism, Zola burnished Warner Bros. reputation as Hollywood’s most socially conscious studio.

That same year, Dieterle directed Blockade (1938) for producer Walter Wanger. Although it is mostly a routine espionage thriller, the film is now remembered as one of the few films Hollywood made about the Spanish civil war. As scripted by John Howard Lawson, who later was blacklisted as one of the Hollywood Ten, Blockade is now seen as an emblem of the Popular Front. Most film historians associate it with anti-Fascist politics, even though the film pointedly avoids identifying the Loyalist and Nationalist sides of the conflict.

Unlike these previous projects, The Devil and Daniel Webster positioned Dieterle as both producer and director. The creative decisions involved in the addition of the Grange subplot would seem more directly under his control. The film’s thematic emphasis on collective interests seems to suggest this political subtext in much the same way that Alfred Hitchcock’s Lifeboat (1944) is sometimes viewed as a parable of democracy’s failure in the face of dictatorship.

In highlighting this allegorical dimension of The Devil and Daniel Webster, I don’t wish to suggest that it makes the film inherently more interesting. Indeed, like other allegorical interpretations, it seems a bit reductive and simplistic. More importantly, if taken too far, these types of interpretive strategies quickly become wrongheaded and even silly (i.e. Belle as a stand-in for Vichy collaboration).

Yet, I also can’t help but feel that The Devil and Daniel Webster’s invocation of American identity offers something important to a contemporary audience. If, like me, you bristle every time you hear “American interests” referenced as the reason to abandon the Paris Accords or to potentially withdraw from NATO, then you have a sense of the film’s relevance to our moment.

The whole arc of the Grange subplot seems to invert much contemporary political rhetoric insofar as it dramatizes the social benefits of the Commons and the individual tragedy of self-interest. In the parlance of our times, Jabez is a risk-taker, mortgaging his immortal soul for the promise of earthly riches. Yet, when we see the resulting inequality in Dieterle’s film, we recognize the situation for what it is. For Jabez, Miser Stevens, and other capitalist mountebanks, it is, quite literally, a deal with the devil. And that, consarn it, is a lesson that all modern viewers can take to heart.

A handy introduction to the continuity system can be found in Chapter 6 of Film Art.

To learn more about the role of editing in guiding viewers’ attention, see Tim J. Smith, Daniel Levin, and James E. Cutting, “A Window on Reality: Perceiving Edited Moving Images,” Current Directions in Psychological Science 21, no. 2 (2012): 107-113. A PDF of this essay can be found here.

Stephen Vincent Benét can be found in many places around the web, including here. Lotte Eisner’s The Haunted Screen: Expressionism in the German Cinema and the Influence of Max Reinhardt (1974, University of California Press) remains a useful introduction to the movement’s lighting and visual motifs. For more on the interpretation of films as political allegories, see my book Film Criticism, the Cold War, and the Blacklist: Reading the Hollywood Reds (2014, University of California Press).

The Devil and Daniel Webster (1941).

ON THE HISTORY OF FILM STYLE goes digital

Dust in the Wind (1986).

DB here:

I was born to write this book.

So I rashly claim in the Preface to the new edition of On the History of Film Style. That’s not to say somebody else couldn’t have done it better. It’s just that the book’s central questions tallied so neatly with my enthusiasms and personal history that I felt an exceptional intimacy with the project.

So I rashly claim in the Preface to the new edition of On the History of Film Style. That’s not to say somebody else couldn’t have done it better. It’s just that the book’s central questions tallied so neatly with my enthusiasms and personal history that I felt an exceptional intimacy with the project.

Baby-boomer narcissism aside, there are more objective reasons for me to tell you about the book’s revival. It came out in late 1997 from Harvard University Press, and it went out of print last fall. Thanks to our web tsarina Meg Hamel, it has become an e-book, like Planet Hong Kong, Pandora’s Digital Box, and Christopher Nolan: A Labyrinth of Linkages.

The new edition is substantially the original book; the pdf format we used didn’t permit a top-to-bottom rewrite. Errors and some diction are corrected, though, and the color films I discuss are illustrated with pretty color frames, not the black-and-white ones in the first edition. The new Preface and a more expansive Afterword explain the origins of the book and develop ideas that I pursued in later research.

The book analyzes three perspectives on film style as they emerged historically. One, what I call the Basic Version, was developed in the silent era and saw the discovery of editing as the natural development of film technique.

The second version, associated with critic André Bazin, modified that conception by stressing the importance of other stylistic choices, notably long takes and staging in depth. I call this the Dialectical Version because Bazin claimed that these techniques were in “dialectical” tension with the pressures toward editing.

A third research program, spearheaded by filmmaker and theorist Noël Burch, argued that the development of film style was best understood as the ongoing interplay between two tendencies. There’s a dominant style Burch called the Institutional Mode. Responses to that mode are crystallized in alternative practices–the cinema of Japan, for instance, or the “crest-line” of major works associated with modernist trends.

The book goes on to show how a revisionist research program launched in the 1970s built upon these earlier perspectives. Younger scholars sought to answer more precise questions about certain periods and trends. The revisionist impulse is best seen in debates on early cinema, which I survey.

The book so far is historiographic, tracing out other writers’ arguments about continuity and change in film style. In my last chapter I try to do some stylistic history myself. I analyze particular patterns of continuity and change in one technique, depth staging. Certain conceptual tools, like the problem/solution couplet and the idea of stylistic schemas, can shed light on how certain staging options became normalized in various times and places. In turn, directors like Marguerite Duras, in India Song (1975), can revise those norms for specific purposes.

On the History of Film Style was generally well-received. John Belton, while voicing reservations, called it “a very good book. Anyone seriously interested in Film Studies should read it.” Michael Wood wrote in a review that “Bordwell is always sharp and often funny” (I try, anyhow) and called the last section “a brilliant account of the history of staging in depth.” The book has been used in some courses, and I’m happy to learn that there are filmmakers who find it useful. It’s been translated into Korean, Croation, and Japanese.

The book is available for purchase on this page. It’s priced at $7.99, a middling point between our other e-pubs. It’s a bigger book than Pandora ($3.99) and the Nolan one ($1.99), but it’s not an elaborate overhaul like Planet Hong Kong 2.0 ($15). Selling the book helps me defray the costs of paying Meg and digging up color frames. In any event, the new version is much cheaper than the old copies available at Amazon. It’s almost exactly the price of two Starbucks Caffe Lattes (one Grande, one Venti).

The archives and festivals that made the book possible are thanked inside, and they’ve continued to be hospitable and encouraging over the last two decades. Equally supportive are the students, colleagues, and cinephile friends with whom I’ve discussed these issues. So I reiterate my thanks to them all. And I hope this new edition, if nothing else, stimulates both viewers and researchers to explore the endlessly interesting pathways of visual style in cinema.

La Mort du Duc de Guise (1908).